Risk anticipation capabilities and preparedness are essential to allow governments to manage critical risks. This chapter examines the extent to which Belgium's risk anticipation capabilities and the initial emergency procedures enabled the country to effectively combat the COVID-19 pandemic prior to the start of the Federal Phase on 12 March 2020. The chapter also looks at the wider preparedness arrangements for pandemics present in Belgium at the start of COVID-19, including the efforts by critical infrastructure operators and essential service providers in Belgium to prepare for a pandemic. It then draws lessons to improve the country’s preparedness to future threats.

Evaluation of Belgium’s COVID-19 Responses

2. Emergency anticipation and preparedness in Belgium

Abstract

Key findings

The OECD’s work on government evaluations of COVID-19 responses has identified risk anticipation and preparedness measures as being one of the three types of measures countries should assess to best learn from the crisis.

The National risk assessment for Belgium had identified the risk posed by infectious diseases prior to the COVID-19 pandemic but there was limited shared understanding of the risk across government (both at federal and federated level). The assessment of risks did not translate into the full range of risk prevention or mitigation measures it could have done.

Planning and preparedness for pandemics and other risks should be enhanced to better place the country for future challenges that may come. Public health emergencies capabilities were used effectively to monitor the situation and take early actions to address the first cases of COVID-19 but were not used to mobilise further preparatory activity across sectors other than health. Lessons from past outbreaks/pandemics, and gaps analysis were mostly limited to the health sector. Mature cross-government crisis management capability, focused primarily on responding to acute crises, was not mobilised from the outset of the COVID-19 crisis. Prior to the start of the Federal Phase, there was a lack of shared situational awareness (including a fragmented view of what information from international sources meant for Belgium).

The critical infrastructure resilience system seemed mostly geared towards infrastructure protection but still delivered enhanced preparedness for essential services. Belgium was able to ensure continuity of emergency services provision through highly adaptive incident response and co-ordination arrangements.

The FPS Foreign Affairs performed a key role supporting Belgians abroad and helping nationals understand travel restrictions in other countries and changing entry requirements globally. Belgium has played an active role in global efforts to respond to COVID-19 and ensure equitable vaccine access.

2.1. Introduction

This chapter examines Belgium's pre-pandemic preparedness efforts, risk anticipation capacities and initial emergency procedures implemented at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, both at the federal and at the federated level. It also examines the pandemic preparedness of Belgium's critical infrastructure operators and essential service providers. In particular, this chapter examines:

the extent to which risk and crisis assessment and anticipation helped the country prepare for the COVID-19 pandemic.

the overall preparedness of critical infrastructure operators and essential service providers, such as emergency services, including their ability to consistently provide personal protective equipment (PPE) and medical supplies to key sectors and the general population.

emergency procedures and mechanisms, and how far they helped effective preparation for the acute phase of the crisis and took account of the cross-border effects of the pandemic.

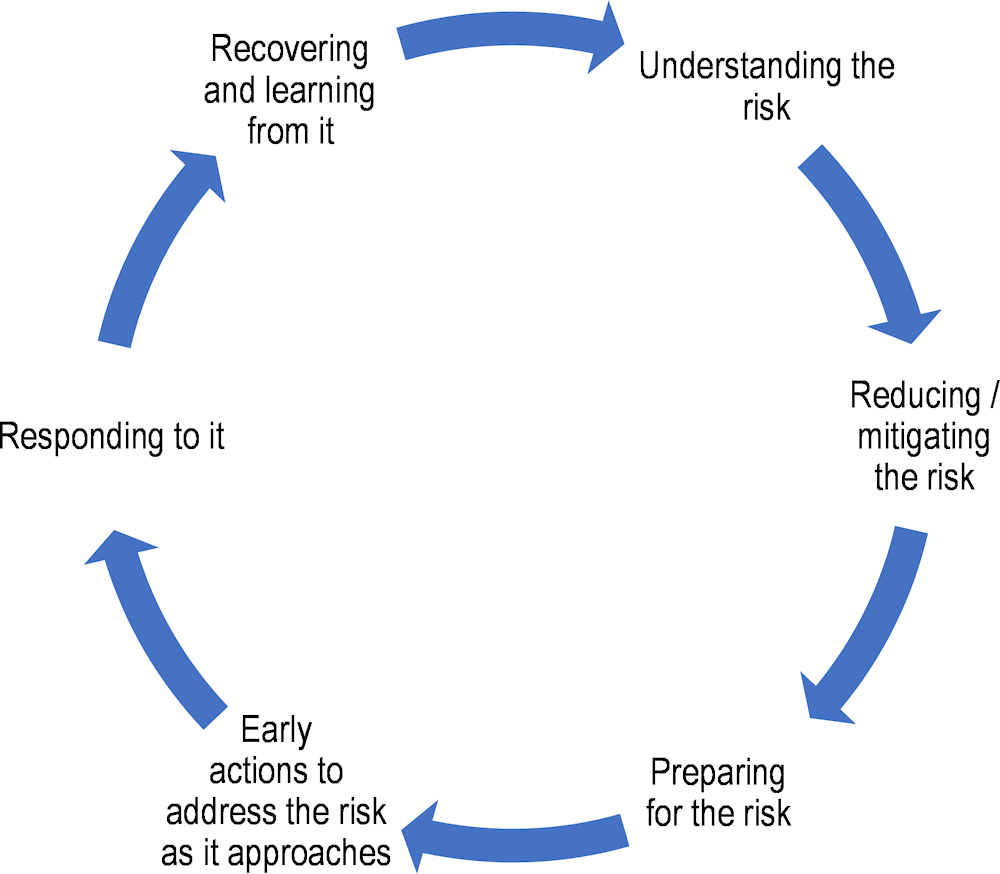

The chapter follows the logic of the disaster risk management cycle (see Figure 2.1), starting with an exploration of how it was that Belgium set out to understand the risk of a potential pandemic. This is then followed by an analysis of the extent to which the information about the risk was used to put in place risk-specific contingency plans and preparedness measures at both national and subnational levels. The chapter then examines barriers to effective preparedness and to what extent early signs of the pandemic approaching (from both European and global sources) were picked up by the Belgian system.

Figure 2.1. Disaster risk management cycle

Source: Adapted from OECD (2019[1]), Risk Governance Scan of Colombia, OECD Reviews of Risk Management Policies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/eeb81954-en.

This chapter focuses on measures taken by Belgium before the start of the federal phase of the COVID-19 response which started on 12 March 2020 (for a full chronology of this initial stage of the crisis, see Annex 2.A); Chapter 3 will cover crisis management measures taken from that date onwards.

2.2. The anticipation capacities of government of Belgium before the arrival of the pandemic in the country

This section examines how federal and federated authorities across Belgium addressed the main steps of the disaster risk management cycle. In particular, the section analyses Belgium's contingency planning prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, focusing on anticipation measures. This section then shifts its focus to pandemic preparedness, shedding light on how it was perceived, and the level of priority assigned to pandemic preparedness across the country's governance structures. Local perspectives come into play as it examines pandemic planning at the municipal level and its impact on local preparedness. Moving beyond pre-crisis preparedness, this section explores Belgium's general risk management framework and its relevance to the initial response during the early stages of the COVID-19 outbreak. This section concludes with an evaluation of how public health emergency capabilities processed early signals of the coming pandemic and the extent of preparatory measures taken in response to the impending pandemic.

2.2.1. Belgium's national risk assessment had identified the risk posed by infectious diseases prior to the COVID-19 pandemic

Risk assessment is the first step in a wider process that culminates in risk informed decision making on the sort of measures that need to be taken in order to prevent or mitigate the negative impacts of the risks identified. Indeed, the OECD Recommendation on the Governance of Critical Risks calls on adherents to identify and assess critical risks and use the resulting analysis to build effective disaster risk and crisis management capabilities (OECD, 2014[2]).

Box 2.1. Anticipation capacities and the Recommendation of the Council on the Governance of Critical Risks

The OECD Council adopted the Recommendation on the Governance of Critical Risks (hereinafter the “Recommendation”) in 2014. An OECD Council Recommendation is one of the several legal instruments the OECD can develop and represents a political commitment to be reached by all OECD Member countries. The High-Level Risk Forum (HLRF) was instrumental in the development of this Recommendation. Since its adoption, 41 countries have signed up to the Recommendation, including Belgium as a Member country of the OECD.

The Recommendation focuses on critical risks, i.e., “threats and hazards that pose the most strategically significant risk, as a result of (i) their probability or likelihood and of (ii) the national significance of their disruptive consequences, including sudden onset events (e.g. earthquakes, industrial accidents or terrorist attacks), gradual onset events (e.g. pandemics) or steady-state risks (those related to illicit trade or organised crime).” The Recommendation is based on the principles of good risk governance that have enabled many Member countries to achieve better risk management outcomes.

The Recommendation proposes that governments:

identify and assess all risks of national significance and use this analysis in decision-making, in particular by:

evaluating risks of national significance and leveraging this analysis to inform risk management priorities,

equipping departments and agencies across all levels of government with the capacities to anticipate and manage the full range of risks the country is exposed to,

monitoring and strengthening the core risk management capacities in the country,

and planning for the potential costs that the government is expected to cover following the onset of a crisis within clear public finance frameworks.

put in place governance mechanisms to co-ordinate on risk management and manage crises across government, including with sub-national entities.

ensure transparency around and the communication of information on risks to the public before a risk occurs and during the crisis response.

work with the private sector and civil society, and across borders through international co-operation, to better assess, mitigate, prepare for, respond to and recover from critical risks.

Source: OECD (2014[2]), “Recommendation of the Council on the Governance of Critical Risks”, OECD Legal Instruments, OECD/LEGAL/0405, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0405.

Like most other OECD Member countries, Belgium considered a variety of infectious disease risks as part of its national risk assessment (OECD, 2018[3]; OECD, 2018[4]). The most recent version of this assessment was completed in 2018 by the National Crisis Centre (NCCN). Within this assessment are three health related risks under the category of diseases and other effects of globalisation that could be seen as relevant for the preparedness for a possible pandemic:

spread of a new infectious disease as a result of globalisation

infectious disease amongst livestock with a direct impact on human health (including zoonotic diseases)

an infectious disease with no possible treatment and a limited stock of vaccines (National Crisis Center of Belgium, 2019[5]).

Belgium has, through the National Risk Assessment process led by the NCCN, taken the first steps towards what is required by the Recommendation. This is currently the minimum common denominator across OECD Member countries, as nearly all have developed similar risk assessments. However, providing an overview of critical risks facing the country is only the first step in the journey towards anticipating risks. Indeed, the OECD Recommendation on the Governance of Critical Risks calls for whole of society and whole of government risk governance and preparedness (OECD, 2014[2]).

2.2.2. Going forward, Belgium could raise awareness of its risk assessment to achieve a shared understanding of risks across all levels of government

In order to increase the awareness of the national risk assessment across the whole of government and the wider society, Belgium could consider complementing passive communication of the assessment (such as the online publication of a summary of the assessment), with a more active communication model. Targeted briefings on the country’s risk profile as part of existing information sharing forums for policymakers across both federal public services and federated entities could be complemented with training for key elected officials at various levels of government. The United Kingdom, for example, delivers briefings on the outputs of the National Security Risk Assessment at meetings of departmental chief scientific advisors, as well as in cross-government meetings of permanent secretaries and cabinet sub-committees.

Belgium could also seek to address this by further engaging parliaments, federal public services and federated entities in the production and review of risk assessments. For example, in Sweden, state agencies, counties and municipalities have a legal obligation to participate in the process for producing a national risk assessment, including doing specific risk and vulnerability analyses for their areas of responsibility (Swedish Minstry of Defense, 2006[6]). In Switzerland, the Federal Office of Civil Protection co-ordinates a national risk assessment process that involves all ministries, as well as the cantonal and municipal authorities. Information on the methodology and the detailed findings of the assessment are publicly available and are debated in Parliament (FOCP, 2020[7]).

While a summary of this assessment was made available to the public - initially via the country’s risk communication website (info-risques.be) (Belgian FPS Interior, 2019[8]), and more recently through a dedicated section within the website of the NCCN (National Crisis Center of Belgium, 2019[9]), the full version of the Belgian National Risk Assessment remains a classified document, which presents challenges when it comes to communicating it across the wider government or to decision makers (Government of Belgium, 2022[10]). Overall, evidence suggests that efforts to communicate the outputs of this risk assessment process to decision makers (at both the federal and the federated level) could be improved. This contributed to less shared understanding of the risks associated with human pandemics across the country, than could have been the case. As a result, in Belgium, the ownership of the topic was generally placed with the federal public health authorities, with little engagement from across government. The risk assessment did not lead to specific risk anticipation activities across government (beyond some of the core capacities linked to the International Health Regulations and more general health emergencies preparedness) as pandemic preparedness was seen as a sector-specific matter primarily concerning the federal public health authorities.

As part of efforts to refine the country’s preparedness for future health crises, Korea implemented both scenario planning and frequent exercises aimed at testing preparedness of public health specialists and other disaster management personnel. In December 2019, the Korean Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCA) conducted an exercise involving infectious disease experts discussing the response to a hypothetical epidemic. The infectious disease that the exercise focused on was a highly contagious coronavirus which caused pneumonia, helping enhance the knowledge across the system of the risk assessment conducted by the country and even consider what type of measures would be needed in such a scenario – which later proved useful for dealing with COVID-19 (Shin, 2020[11]). Belgium could consider using scenario discussions and exercises to help raise awareness of the national risk assessment and improve shared understanding of the risks, whilst considering the country’s capacities for dealing with the scenarios explored.

2.2.3. In Belgium, the assessment of risks should inform policy and decision making going forward, as it did not translate into sufficient risk prevention or mitigation measures prior to COVID-19

In addition to having such a national risk assessment, the Recommendation encourages adherents to use risk assessments to inform the development of prevention, mitigation or preparedness capabilities. Anticipation capacities such as this make it possible to act either before a crisis hits or at least before substantial impacts are felt (OECD, 2014[2]).

In Belgium, the health risks covered in the Belgian National Risk Assessment were not sufficiently leveraged to inform all decisions on anticipatory actions requiring significant investments (such as the renewal of stockpiles and a reserve capacity for public health emergency response). Nevertheless, some important core capacities were in place across the Belgian healthcare system prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (such as laboratory capacities for early testing of samples linked to outbreaks, isolation units for highly transmissible diseases, and an above-average number of intensive care beds).

Anticipatory actions: a set of actions taken to prevent or mitigate potential impacts before a crisis or before acute impacts are felt. The actions are carried out in anticipation of a potential impact and based on some understanding of how the event might unfold. (International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent, 2020[12])

Belgium is not alone in having performed a risk assessment but failing to fully leverage its findings to put in place the full range of anticipatory capacities that could have reduced the impacts on lives, livelihoods, and systems and services essential to the normal functioning of society (European Commission, 2021[13]). Furthermore, as the country did not introduce any supplementary legislation mandating pandemic preparedness planning prior to COVID-19, the risks to human health covered in the Belgian National Risk Assessment were not deemed to require specific emergency plans by most actors (beyond health). Health had developed an influenza pandemic plan – see Section 2.2.4 – and a protocol between federal and federated entities for dealing with public health emergencies, including the establishment of an Interministerial Conference of Health Ministers, the Risk Assessment Group (RAG) and the Risk Management Group (RMG) (Belgian Federal Government, 2018[14]) – however these mechanisms were mostly limited to sectoral arrangements. Generic plans need to be complemented with more targeted contingency planning for risks which are expected to pose particular challenges or those which are likely to require co-ordination between the various levels of government. This principle is well established in Belgium, with its system recognising the need for specific contingency plans for certain risks, such as those associated with major industrial accidents involving dangerous substances, nuclear incidents (Belgian Federal Government, 2003[15]) or terrorism (Belgian Federal Government, 2020[16]) (see Box 2.2). These specific contingency plans (“specific Emergency and Response Plan” or PPUI/BNIP) provide detailed descriptions of the risks, emergency planning zones, intervention zones, contact lists, scenarios, specific procedures for informing the public, and actions to protect people and property.

Box 2.2. Contingency planning in Belgium

In Belgium, contingency planning is organised through several distinct types of plans designed to address various types of emergencies.

At the municipal and provincial levels, there is a requirement for each mayor or governor to have a generic contingency plan ("General Emergency and Response Plan" or PGUI/ANIP) for their respective areas. (Belgian Federal Government, 2019[17]) This plan encompasses general measures for managing emergency situations of all kinds. It includes information such as contact lists of relevant partners, potential risks, the timing of plan updates, and details about how emergency situations will be managed, including communication channels, responsibility for public information dissemination, and the establishment of accommodation centres for those displaced by an emergency.

At the national level, there is also a generic contingency plan ("General Emergency Plan"), established by a royal decree (Belgian Federal Government, 2003[18]) which sets out general principles for co-ordinating and managing national-level emergencies.

Source: in the text.

However, at the provincial and municipal level, pandemic preparedness was not seen as one of the areas that required a specific emergency management plan (PPUI). At the federal level, pandemic planning was viewed as a sectoral plan falling under the responsibility of the Federal Public Service (FPS) Public Health, with the rest of the organs of the state not explicitly considering pandemic scenarios in their own planning. This meant the absence of specific pandemic preparedness planning activities across most of government at both the federal and federated levels.

Across the country, contingency planning itself was seen as the preserve of the federal government, so federated entities had little incentive to consider pandemic scenarios in their planning. These perceptions may have led to insufficient commitment from both policy and decision makers, contributing to inadequate resource allocation for pandemic preparedness, and an under-prioritisation of proactive measures across the whole of government and throughout both the federal and federated entities. Shifting this perception is vital to fostering a culture of preparedness and encouraging all actors across all levels of government to recognise the critical importance of planning for future pandemic scenarios.

Belgium would benefit from developing mechanisms for explicitly feeding risk assessment into policymaking and decision making. For example, the National Risk Assessment of the Kingdom of the Netherlands is produced as a collective effort of the National Network of Safety and Security Analysts, and it explicitly informs the National Security Strategy for the country, which is then discussed in Parliament and followed-up by it (National Network of Safety and Security Analysts, 2023[19]). Similarly, the United Kingdom uses its national risk assessment in the production of its Integrated Review, which sets out the Government’s national security and international policy. The commitments described in the Integrated Review are then further detailed in the UK Government Resilience Framework (House of Commons Library, 2023[20]). Whilst the governance structure of Belgium differs from that of the examples cited, practices from other countries with a federal system, reinforce the importance of feeding risk assessments into policy and decision making. The experience in the United States using the National Threat and Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment (FEMA, 2023[21]) to drive the work needed to fulfil the National Preparedness Goal presents an example of a country with a federal system working on national preparedness at multiple levels of government. In the United States, efforts conducted at the Federal government-level on the National Preparedness Goal, are complemented by the activities of state and tribal governments as part of the National Preparedness System (FEMA, 2020[22]). To facilitate this, the Federal Emergency Management Agency produces guidance on how state and tribal authorities can make use of the information coming out of the national assessment to further the resilience of the communities they are responsible for.

2.2.4. Planning and preparedness for pandemics could have been better prioritised

Contingency planning for pandemics involves complex multi-sectorial planning, resource allocation, and collaboration among various actors at different levels of government. The level of complexity of this endeavour, the tension between spending on contingency measures for a potential pandemic and pressing needs from the national health system, as well as the challenges of collaborating across levels of government, all contributed to Belgium not having an up-to-date pandemic response plan when the COVID-19 crisis hit. Furthermore, the country under-resourced the units responsible for health emergency planning and depleted its national stockpiles of personal protective equipment. This was aggravated as staff in specialised units and at the corporate level within the FPS Public Health retired without robust knowledge management processes to prevent the loss of institutional memory. As a result of these compounding factors, Belgium was not as well prepared for a pandemic as it could have been.

Following the emergence of SARS in 2003, the federal health authorities started working on an operational plan for managing an influenza pandemic. This plan was initially drawn up within the Belgian Interministerial Influenza Coordination Committee (CII). The initial draft was prepared in 2006 by a team that included what are today the FPS Public Health and of Sciensano, as well as the NCCN, the Federal Agency for the Safety of the Food Chain, the Federal Agency for Drugs and Health Products and health departments from the regions and communities (Belgian Advisory Committee on Bioethics, 2009[23]). At the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic Belgium lacked an up-to-date pandemic plan, and had only conducted limited training and briefing of key actors on the pandemic plan and their role within it. This stands in clear contrast with the experience of New Zealand, where not only was there a current pandemic plan in place, but this formed an integral part of a pandemic preparedness system that enabled a rapid reaction to COVID-19 (see Box 2.3).

Box 2.3. From risk assessment to pandemic preparedness – the New Zealand experience

In New Zealand, the national risk assessment contributed to the development of the National Pandemic Plan, the development of Ministry of Health emergency management teams, and a pandemic readiness programme and a national exercise programme which emphasised the criticality of business continuity planning to pandemic preparedness.

The most recent version of New Zealand’s pandemic plan prior to COVID-19 was released in August 2017. The plan had been modified to take into account lessons learned during the response to the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic and was intended to be adaptable and flexible.

For New Zealand, the serious nature of the outbreak in Wuhan and its pandemic potential became clear in late January and the country began to implement its existing pandemic plan.

Provisions on public communications and co-ordination of a whole of government response, which had been exercised prior to 2020, proved helpful for shaping the country’s response to COVID-19.

Sources: OECD (forthcoming[24]), 2022 OECD Questionnaire on the Governance of Critical Risks; New Zealand Ministry of Health (2017[25]), Influenza pandemic plan: A framework for action; and Kvalsvig and Baker (2021[26]), “How Aotearoa New Zealand rapidly revised its Covid-19 response strategy: lessons for the next pandemic plan”.

Following the H1N1 pandemic in 2009 the federal public health authorities sought to update the influenza plan. However, resource pressures meant the influenza pandemic response plan was not regularly updated or exercised. While having a plan in place is a crucial step towards preparedness, the effectiveness of plans can diminish if they remain stagnant, untested and unknown to key actors. Regular updates ensure that plans are aligned with evolving risks, technological advancements, and lessons learned from past crises. Belgium’s health contingency planning, thus became anchored in an out-dated plan and did not fully incorporate lessons from major outbreaks globally. Having an out-of-date plan also eroded the trust of decision makers in pre-established contingency plans, contributing to the proliferation of ad hoc structures (see Chapter 3).

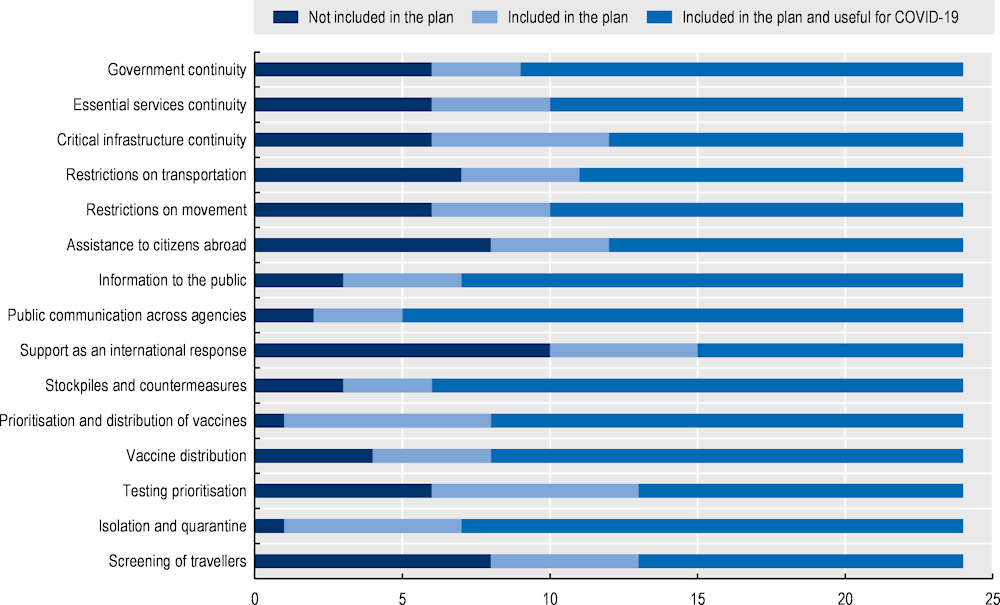

Not having an up-to-date pandemic plan ahead of COVID-19 makes Belgium an outlier amongst OECD Member countries. 24 out of 27 OECD Members answering the 2022 OECD Questionnaire on the Governance of Critical Risks, indicated they had such a plan in place prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (OECD, 2022[27]). The majority of those having such plans also indicated that a fair amount of the challenges that came up during their response to the pandemic were included in their plans and useful for dealing with COVID-19 (see Figure 2.2). In particular, provisions linked to providing information to the public and aligning public communication messaging across government agencies were generally present in pandemic plans and deemed useful for dealing with COVID-19.

Figure 2.2. Elements of pandemic plans present and useful for COVID-19 across OECD Members

Source: OECD (forthcoming[24]), 2022 OECD Questionnaire on the Governance of Critical Risks.

As a complement to the national pandemic plan, the NCCN worked with health authorities to develop guidance on how to approach business continuity during a pandemic. This guidance, completed in 2006, focused on the socio-economic implications of a potential pandemic influenza outbreak. Following the 2016 terrorist attacks, at the request of the Conference of Presidents of Federal Public Services, a working group was set up under the co-ordination of the NCCN. This working group was tasked with preparing a template for business continuity management for Federal Public Services. This template, along with an explanation of what business continuity management is, was proposed and approved by the Conference of Presidents of Federal Public Services in 2019. This guidance, was then revisited by the NCCN and an updated version was made available shortly before the transition to the federal co-ordination phase of COVID-19 crisis response (National Crisis Center of Belgium, 2020[28]). Complementing pre-existing business continuity efforts with measures specific to a particular disruptive event that can be foreseen is not unusual, but may be less effective when a crisis has already started to affect the region and disrupt global markets. In the case of COVID-19, some preparedness measures, such as the procurement of stocks of personal protective equipment, were no longer feasible or came at a much higher cost once the pandemic had reached Europe.

Investing in a robust public health emergencies capability and a stable workforce, as well as ensuring that those responsible for public health emergencies have the necessary tools and expertise needed for bolstering overall preparedness for pandemics. Under-resourced units responsible for preparedness is another challenge that Belgium was confronted with. The efficacy of pandemic response depends on the capacities and capabilities of the units tasked with planning, co-ordinating, and executing these efforts. Insufficient funding, staffing, competencies and resources for these units can hinder their ability to develop comprehensive strategies and respond effectively to emerging threats. Within the FPS Public Health, the unit responsible for conducting this planning slowly saw its resources depleted in the years preceding the COVID-19 pandemic. This included decreasing the size of the unit by not recruiting new staff to replace personnel retiring.

The issue with under-resourced public health units was highlighted in 2017 when a joint external evaluation of Belgium’s International Health Regulations capabilities was performed. As part of the evaluation’s recommendations, the World Health Organisation found that Belgium did not have adequate capacities for dealing with protracted public health emergencies and recommended the implementation of a workforce plan and a strategy in order to bridge this gap (WHO, 2017[29]). However, there is no evidence these recommendations were acted upon at either the federal or federated levels. As a result, capacities for dealing with public health emergencies at the level of the federated entities, in particular those needed for effective outbreak control and contact tracing, were likely weaker than they should have been.

Another challenge faced by Belgium was the depletion of its national strategic stockpiles. Between 2003 and 2006 Belgium set up a national stockpile of masks. The national influenza pandemic plan highlighted the importance of masks as individual protection measures. This plan proposed to make two types of masks available: surgical masks for patients and healthcare staff, as well as respirator masks for healthcare staff in the event of exposure to potentially infectious aerosolised particles. These stockpiles were designed to provide essential equipment during emergencies. An advisory opinion of the Belgian Advisory Committee on Bioethics highlighted the usefulness of keeping stockpiles of masks (both surgical and respiratory (type FFP2) masks). The opinion suggests the use of surgical masks in order to prevent contaminated persons from contaminating others, not as a measure to help the general public limit the spread of the disease. Similarly, the opinion also suggests that sufficient stocks of respiratory masks should be kept in order to help protect those coming into direct contact with people who could be infectious. Whilst the opinion states that not only healthcare professionals should be considered when planning the stockpiles, there is no suggestion that stockpiles of respiratory masks need to be kept for use by the general population (Belgian Advisory Committee on Bioethics, 2009[23]). However, and in spite of the technical advice and their mention in national contingency plans, these stockpiles were not replenished after being utilised or after being destroyed following the end of their shelf life, leaving the country vulnerable to subsequent pandemics. At the level of the federated entities, keeping of stockpiles was not seen as an explicit requirement and there was a lack of guidance on how the national strategic stockpiles might be drawn upon or complemented with local stocks. Failing to guarantee the availability of these stockpiles at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic, undermined the robustness of the country’s response to the pandemic and highlighted the challenges to sustained investment in health emergency preparedness in Belgium.

2.2.5. Going forward, Belgium could use a shared understanding of risks to drive evidence-based preparedness activity and track its progress over time

Belgium could make better use of the evidence-base underpinning the national risk assessment to inform resourcing decisions on the capabilities required for addressing key risks. An example of such a mechanism, in Australia, is the Queensland Emergency Risk Management Framework (QERMF). The framework sets out a process for local, district and state authorities to not only conduct risk assessments, but also provides a method for turning the analysis into actionable advice on resource allocation. Actors participating in all levels of Queensland’s Disaster Management Arrangements are thus able to use robust, evidence-based risk assessments for applications for resources and funding (Queensland Fire and Emergency Services, 2018[30]).

Furthermore, there is a need for a feedback loop in order to ensure there is a connecting thread linking these resourcing decisions with the levels of capabilities required for dealing with the risks identified in the assessment. Canada’s capability-based planning approach uses an evidence-informed process identify gaps in capabilities and improve national resilience, interoperability, and integrated planning in emergency management. This approach fosters interagency collaboration and innovation, providing a common framework for resource co-ordination and achieving shared goals. It builds on the Canadian Core Capabilities List (which identifies the capabilities required based on the National Risk Profile) and includes an assessment of the progress made on their development against a pre-defined set of goals (Public Safety Canada, 2023[31]). Belgium could develop a similar system for understanding the level of preparedness against identified risks and track progress on mitigations and on the development of the capabilities required for dealing with them. To ensure the activity needed to develop the required capabilities is adequately resourced, there is a need to develop mechanisms for increasing the attention given by senior leadership across all levels of government to all-hazards crisis preparedness and resilience. A way of doing so could be for Belgium to involve ministers from federal and federated entities in explicit discussions about preparedness for high impact events and complex crises.

In addition to buy-in from leadership, oversight and accountability mechanisms can further drive improvements in the planning and preparedness system. In the United Kingdom, the National Audit Office (NAO) conducted a review of the lessons on risk management that government could draw from the COVID-19 pandemic. One of the key lessons raised by this report was precisely about how to ensure lessons from past incidents are identified, addressed and followed-up. The NAO recommended that the Cabinet Office should set up a cross-government process to capture learning for emergency preparedness and resilience from exercises and actual incidents, and to allocate clear accountabilities for applying learning – including a yearly reporting process (National Audit Office, 2021[32]). As part of the Cabinet Office’s efforts to synthesise lessons learned of all major exercises and emergencies, the country now publishes the UK Resilience Lessons Digest (Cabinet Office EDS/Cabinet Office EPC, 2023[33]). Since 2020, the various parliaments in Belgium all set-up special commissions to scrutinise various aspects of the COVID-19 response, providing democratic oversight for the efforts to tackle the impacts of the pandemic and control the spread of the virus. Belgium could further leverage democratic accountability, including the role of parliaments, to follow up on how lessons from past incidents are implemented and how gaps in preparedness are addressed.

Wider system reforms arising out of lessons from recent events (including COVID-19, Russia’s war on Ukraine, and major floods across Europe in 2021), provide an opportunity for Belgium to review the legislation underpinning emergency planning duties at all levels of government to mandate preparedness planning across federal and federated entities. Sweden, has recently embarked on such a process, introducing legislation that reforms the crisis preparedness and civil defence system of the country. The new system is organised around ten Civil preparedness sectors, each with a lead authority with sectoral responsibilities, the Swedish Civil Preparedness Agency providing support and guidance, and a National Security Council at the Prime Minister’s Office providing strategic co-ordination (Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency (MSB), 2022[34]). Estonia is also seeking to bring competences contained in multiple legislations under a single act and use this statutory reform to speed up implementation of key EU directives (such as the Critical Entities Resilience Directive).

2.2.6. Pandemic planning at the municipal level was generally lacking but its absence is not perceived as the main reason for poor preparedness at the local level

To understand the importance of municipalities in crisis response and preparedness in Belgium, it’s helpful to provide context through two key decrees: one from 2003 (Belgian Federal Government, 2003[18]) and another from 2019 (Belgian Federal Government, 2019[17]). These decrees emphasise the role of municipalities in handling crises and preparing for them.

Evidence from the OECD survey of Belgian municipalities on the country’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic, shows that only a very small proportion of municipalities across Belgium had a multi-disciplinary emergency plan that covered their pandemic response (only 40 out of 259 surveyed), even after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (OECD, 2023[35]). Of the municipalities which had such a plan, roughly one fifth had in place a General Emergency and Response Plan prior to the apparition of the first case of COVID-19.

In total, just under 2% of the municipalities surveyed had produced an annex to their General Emergency and Response Plan addressing pandemic preparedness before COVID-19, and slightly over 3% of municipalities produced such an annex after the first case of COVID-19 in the country but before the federal phase of the pandemic response kicked in. Some municipalities had decided to produce specific emergency and response plans for pandemics, with over 2% doing so before the first case of COVID-19, and an extra almost 4% implementing specific plans after the first case but before the federal phase had kicked in. This is particularly notable given that the duties to keep such plans were only introduced in 2019 under the Royal Decree on emergency planning and management at municipal and provincial level. (Belgian Federal Government, 2019[17]). A smaller proportion of municipalities introduced plans only after the country had entered the federal crisis management phase, but the majority of municipalities that had adopted specific plans or supplemented their plans with a specific pandemic-related annex did so during the period between the first case of COVID-19 in Belgium and the start of the federal crisis management phase (see Figure 2.3). The low number of municipalities with specific pandemic plans, even once the scale of the challenges posed by COVID-19 became evident, suggests that either pandemics were not picked up as a risk in local risk assessment, or if it did, that generic planning would suffice – specific pandemic preparedness seems to not have been seen as a task for municipalities across most of the country.

Figure 2.3. Shift from a generic emergency plan towards a specific emergency and response plan for pandemics

Note: N=259. VLA =129, WAL=114, BXL=9, German-Speaking Community=7.

Question: Have you drawn up an emergency and intervention plan for pandemic risks, or included a specific annex on pandemics, as defined by the Royal Decree of 22 May 2019 on local emergency planning (PGUI/ANIP//PPUI/BNIP)?

Source: OECD (2023[35]), OECD Survey of municipal authorities for the evaluation of Belgium’s COVID-19 response.

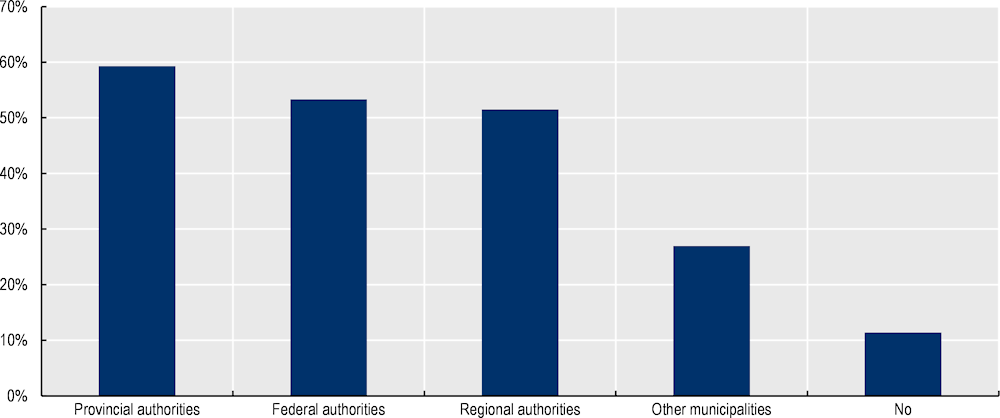

The majority of municipalities across Belgium seem to have conducted an assessment of their pandemic preparedness needs (nearly 65% of those responding to the survey conducted by the OECD). However, the survey also revealed that a notable proportion of municipalities did not (close to 35%) (OECD, 2023[35]).

The answers from municipalities which have undertaken a needs assessment since the onset of COVID-19, highlight where they have turned to for guidance and support, not just in performing the assessment itself but also in addressing the gaps in their system. As would be expected in a complex decentralised system such as the Belgian one, there was a significant level of diversity in the sources of advice, guidance and support used by municipalities across the country.

Approximately 53% of the municipalities which had undertaken an assessment of needs relied on support and guidance from federal authorities, showcasing a significant reliance on central government strategies and advice. Regional authorities have also played a substantial role, with around 51% of municipalities seeking guidance from this level, followed closely by support from provincial authorities, roughly 27% of municipalities. However, it is worth noting that around one fourth of municipalities expressed having been influenced by the practices of other municipalities (see Figure 2.4).

Figure 2.4. Sources of guidance and support used by municipalities with a needs assessment in place

Note: N=167. VLA =88, WAL=68, BXL=7, German-Speaking Community=4.

Source: OECD (2023[35]), OECD Survey of municipal authorities for the evaluation of Belgium’s COVID-19 response.

It is worth noting that in areas with established First Line Zones, municipalities have indicated these have proved useful in both helping them understand their pandemic preparedness needs and in addressing the gaps identified. First Line Zones are meant to strengthen the collaboration between the local health actors and the municipal authorities, this reinforced collaboration is expected to help municipalities benefit from the technical expertise of the health sector when it comes to dealing with public health emergencies.

The challenges and successes faced by various municipalities shed light on the nuances of pandemic preparedness. There are instances of delayed assistance, indicating that support from higher authorities arrived later than desired. Some municipalities initially navigated the crisis independently but later received assistance from different levels of government. Collaboration across municipalities was evident in efforts such as setting up vaccination centres and pooling resources. Challenges around personal protective equipment (PPE) shortages were encountered, leading to innovative solutions, such as local business innovation hubs mobilising local entrepreneurs to not only produce PPE, but also identify reliable global suppliers, and test the quality of the equipment procured. Additionally, some of these hubs formed a task force to co-ordinate efforts between public and private entities, streamlining the distribution of protective gear.

Despite some success stories, comments from municipalities highlight shortcomings, such as the need for clearer national frameworks, improved decision-making involvement for municipalities, and better long-term needs identification. The varying experiences showcase the dynamic nature of pandemic response, where local adaptability played a significant role. Nevertheless, a large proportion of municipalities across Belgium (more than 62% of those responding to the OECD survey) noted they had not been sufficiently prepared to implement the national COVID-19 restrictions. When asked about the main reasons behind this lack of sufficient preparedness, municipalities overwhelmingly attributed this to the timing of the announcements and the lack of sufficient time to prepare the implementation of measures taken. However, the main purpose of contingency plans is to enable the adoption of timely response measures to limit the impact of a disruptive event – as such, having pandemic plans in place could have prepared the ground for swift implementation of measures taken at the national level.

2.2.7. Mature crisis management capability focused primarily on responding to acute crises and was not mobilised from the outset of the COVID-19 crisis

The Belgian strategic crisis management system has developed incorporating lessons derived from various incidents (most notably the terrorist attacks of 2016) and the specific set-up of the Belgian administrative system. Prior to COVID-19 the Belgian crisis management system had been used to handling acute crises, most of them with a discreet geographic scope and relatively short lived. At the outset of the pandemic there was a lack of consensus as to when to activate this strategic crisis management system and this limited the benefit the country derived from the maturity of its system.

The central node of the national strategic management system is the National Crisis Centre (NCCN), which was established in 1988 (Belgian Federal Government, 1988[36]). The NCCN is tasked with prioritising risks, maintaining an active watch on threats to the nation, collecting and disseminating urgent information, and providing crisis management support to the country.

The systematic integration of key components of crisis management has fostered a comprehensive approach to readiness for the kind of acute crises the country had experienced prior to COVID-19. This approach has included not only actors across the Belgian federal government, but also within various levels of government, with clear expectations and communication channels established for municipal and provincial crisis management structures laid out in statute (Belgian Federal Government, 2019[17]). The NCCN has also fostered close co-operation between public authorities and private sector actors responsible for critical infrastructure.

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, Belgium’s crisis management system could be considered mature by OECD and European Commission standards (Tubb, 2020[37]; OECD, 2014[2]). This maturity is reflected in the integration of risk awareness, prevention, preparedness and resilience at all levels of government and among private sector operators. As can be seen in Table 2.1 below, Belgium had indicated its crisis management system covered nearly all the features of a mature system set out in the OECD Recommendation.

Table 2.1. Features of a mature crisis management system prior to the COVID-19 pandemic

|

In the OECD Recommendation |

Present in Belgium |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Standard operation procedures for crisis management |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Organisational structure with defined roles and responsibilities |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Emergency response plans for the main types of risk |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Process for co-ordination between ministries |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Process for international co-operation |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Intelligence processing system to inform decision making |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Mechanism for liaising with international monitoring and early warning systems |

Yes |

Yes |

|

A public information system |

Yes |

Yes |

|

The power to demand resources from the private sector in times of crisis |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Training of civil servants on the crisis management system |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Training of ministers on the crisis management system |

Yes |

No1 |

|

Mechanism for mobilising multidisciplinary expertise to support crisis management |

Yes |

Yes |

1. An expanded programme to train officials across government on the national crisis management system was introduced following the COVID-19 pandemic. The NCCN also organised exercises with the participation of ministerial cabinets (cabinet heads) prior to the COVID-19 pandemic – although none of these exercises focused on public health emergencies.

Generic emergency planning, however, is perceived across the country as being a responsibility that follows federal reporting lines (from mayors through provincial governors and all the way to the NCCN). This model is predicated on the idea that follows the principle of subsidiarity, where crises are managed at the level of government closest to the affected population, with a clear system for escalation (from communal to provincial to federal management as may be required). However, this crisis management escalation process does not recognise an explicit role for federated entities – even for crises where their competences are involved. According to this system, the activation of a federal co-ordination phase could take place as soon as a crisis affects multiple provinces, exceeds provincial resources required for handling it, involves numerous victims, involves major effects on the environment and/or the food chain, damages or threatens to damage the nation’s vital interests, requires co-ordination with various ministerial departments, or requires providing information to the entire population (Belgian Federal Government, 2003[38]) (see also Chapter 3).

At the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a lack of consensus regarding when the transition to a federal co-ordination phase should take place. Indeed, multiple actors across the various levels of government have indicated that, prior to the 12 March 2020, they had made presentations to the federal authorities indicating their belief the situation would benefit from the structures in place for the federal co-ordination of the crisis management efforts and that the threshold for the activation of such a phase, as described above, had already been met. As a result, the NCCN was not mobilised to support the co-ordination of the COVID-19 situation until the activation of the federal phase on 12 March 2020. This created challenges because the national crisis management system, designed for achieving shared situational awareness and cross-sector co-ordination of response efforts, was not used – resulting in a lack of a common view of the risks and challenges COVID-19 presented across the various actors at the level of both federal and federated entities.

Even though the National NCCN was not mobilised to co-ordinate the COVID-19 situation from the start, it still provided support to the Federal Public Service for Public Health (hereafter, FPS Public Health) from the initial phases of the crisis, that is from January to March 2020. The collaboration between NCCN and the FPS Public Health encompassed various aspects of risk anticipation and preparedness, ranging from communication efforts to legal advice (National Crisis Center of Belgium, 2021[39]). From the early days of the COVID-19 crisis, it became apparent that there would be a significant interest from the public and the media in updates on the evolving situation. The NCCN sought to support the FPS Public Health deal with inquiries from the general public and contributed to the development of a risk communication strategy based on the Standard Operating Procedures for Crisis Communication framework. The NCCN regularly analysed the perceptions and needs of the media and used this to provide strategic and operational advice to public health authorities on aligning risk communication with the evolving situation. Furthermore, the NCCN supported public health by helping establish specific information channels, including a dedicated information number, the activation of the national COVID-19 information website and co-ordination with social media platforms. The NCCN also assisted the FPS Public Health with stakeholder engagement, facilitating communication between governors, and public health officials to ensure clear channels for sharing information and addressing queries promptly.

Collaboration extended to legal matters, as the legal services of both the FPS Public Health and the NCCN worked together on issues related to quarantine measures. This collaboration involved the analysis of legal aspects and the provision of templates for the placement and management of quarantine measures by the federated entities. This collaboration, which was delivered on an ad hoc basis, highlights the need for clear processes for mobilising the NCCN’s generic crisis response capabilities prior to any activation of a federal phase.

2.2.8. Belgium has an opportunity to enhance its crisis management capabilities to facilitate early mobilisation

An aspect that came up strongly throughout the evaluation of Belgium’s preparedness prior to COVID-19, was the absence of a system that helped deliver shared situational awareness across the whole of government prior to the Federal Phase. Belgium should consider developing pre-crisis capabilities for achieving shared understanding of risks and joint situational awareness across sectors and levels of government (inspired by the practices and procedures for crisis management developed by the NCCN such as the common information picture). For example, in the United Kingdom, a key tool for ensuring shared situational awareness is the National Situation Centre. It is part of the national crisis management structures that the Cabinet Office co-ordinates and was created to gather and collate reliable and timely data about all aspects of crisis response. Expertise from the Government Actuaries Department and the Office of National Statistics has helped developed the analysis, modelling and quality assurance tools and processes used by the Centre.

Another aspect that could have aided the early mobilisation of national crisis management structures in Belgium, as it did in other countries, is the existence of a gradual process for activating and scaling up flexible capacities. In France, the Ministry of Health's Centre opérationnel de régulation et de réponse aux urgences sanitaires et sociales (CORRUSS) has an organisation that can be adapted to each situation, whilst remaining proportionate. From the day-to-day management of health alerts to the management of an exceptional health situation, the CORRUSS is able to mobilise flexible capacities in a gradual way. Three levels of activation – going from operational watch to a full activation of the Health Crisis Centre – allow the Centre to scale up and scale down responses as required (Ministère de la Santé et de la Prévention, 2021[40]). One of the response capabilities available to the Ministry of Health is the health reserve (réserve sanitaire), which is made up of active, retired or graduating healthcare professionals, which can be mobilised at very short notice for missions of varying duration (Santé Publique France, 2023[41]). Belgium would benefit from developing mechanisms for establishing flexible capacities (such as strategic stockpiles or surge capacities) that can be put on stand-by and stood down if not required – to make early mobilisation of capacities easier.

2.2.9. Belgium was able to use its public health emergencies capabilities to monitor the situation and take early actions to address the first cases of COVID-19, but more can be done to mobilise further preparatory activity beyond health

Prior to the emergence of COVID-19, the FPS Public Health had already established generic structures for the "detection, assessment, notification, reporting, and response through public health action proportionate and limited to the risks it presents to public health" (Belgian Federal Government, 2018[14]). In Belgium, it is the Ministry of Health, the FPS Public Health, that acts as the national focal point for the purposes of the International Health Regulations (IHR) – with Sciensano playing an active role in the systems for notification and reporting into both the WHO and European Union relevant agencies. This role is facilitated by two standing groups which perform a central role in the monitoring and management of risks to public health in the country: the RAG and the RMG. These groups were established in 2007, following the adoption of the IHR, with their role and membership established in a protocol between the federal and federated Belgian Health Authorities (Belgian Federal Government, 2018[14]). Both groups convene a wide range of health sector stakeholders from both the federal and the regional and language community levels.

Sciensano co-ordinates the RAG, which is tasked with evaluating threat to public health and assessing the risk posed to public health, based on epidemiological and scientific data. The RAG is also responsible for proposing measures to the RMG to limit or control such a threat and for evaluating the impact of interventions. The RMG consists of representatives of health authorities and chaired by the National Focal Point for the IHR, which is part of the FPS Public Health. Based on the advice of the RAG, the RMG makes recommendations on the measures that are needed to protect the public health to the Interministerial Conference for Public Health. The RMG has also been empowered, by the Interministerial Conference for Public Health, to take decisions directly when considered appropriate. The decision on whether to take the measures suggested by RMG lies with the Interministerial Conference for Public Health, which has the ability to eventually raise the matters to the Concertation Committee. The RMG is also tasked with leading the communication to public health professionals and the general public.

Already on 20 January 2020, Sciensano had mobilised members of the RAG for a first discussion on the novel coronavirus. On 22 January, as the situation in China evolved, the World Health Organisation (WHO) Director-General convened a meeting of the IHR Emergency Committee to determine whether the novel coronavirus met the criteria to be considered a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC). The meeting took place over 2 days (22-23 January) and ended without a recommendation to declare a PHEIC (The Independent Panel of Pandemic Preparedness, 2021[42]).

On 23 January, the first meeting of the RMG regarding the novel coronavirus took place. This meeting, however, makes no mention of the IHR Emergency Committee meeting convened by the WHO. RMG decided that, according to the available information, Belgian authorities would be in a position to offer a message of reassurance regarding the novel coronavirus. This was deemed as justified given there was already an ongoing system of epidemiological surveillance in place in the country, with the disease already subject to obligatory notification procedures. In addition to this, RMG further supported their decision on the existence of a protocol for handling a first case of the disease in Belgium, that the National Reference Center (CNR) had already developed a test procedure and that the country already had a specialised hospital facility and a well-functioning patient transportation mechanism designed to address cases of highly contagious respiratory diseases (Belgian FPS Public Health, 2020[43]).

The following day, the FPS Public Health issued advice to general practitioners across the country regarding the case definition for the novel coronavirus and the measures to take in case they identified a possible first case of the disease.

On their second full risk assessment on the novel coronavirus, issued on 26 January 2020, the European Centre for Disease Control (ECDC) considered that the potential impact of the outbreak of the novel coronavirus was high and that further global spread was likely. The ECDC stated that there was a moderate likelihood of further case importation into Europe and that the impact of the late detection of an imported case in Europe could be high (ECDC, 2020[44]). Following this warning, the RAG and RMG considered the need to reinforce epidemiological surveillance measures in the country (through a notice to health practitioners requiring them to declare any suspected cases of the novel coronavirus and the established lab capacity to detect cases). However, contact tracing or testing arrangements were not, at this stage, scaled up as a result of the ECDC risk assessment.

Box 2.4. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), the European Early Warning and Response System (EWRS), and the EpiPulse forum

At the European Union level, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) plays a leading role in identifying, assessing and communicating current and emerging threats to human health posed by infectious diseases.

The ECDC hosts the European Early Warning and Response System (EWRS), an online platform that enables the European Commission, the ECDC and public health authorities in the Member States to exchange information.

Each national administration (the FPS Public Health as the national focal point for the International Health Regulations for Belgium) must notify alerts and measures taken to protect public health in the face of a serious threat.

This platform predates the IHR and has played an important role in ensuring co-ordination between EU member states during a number of outbreaks, ranging from the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) crisis in 2005, Ebola, and avian influenza, amongst other.

In addition to the EWRS, there is also the EpiPulse forum, which is aimed at facilitating discussions among public health experts. Sciensano is responsible for updating responses for Belgium.

Following notification, the Health Security Committee (HSC) enables EU Member States to co-ordinate national responses and provide risk and crisis communications updates to each other.

Source: Decision no. 1082/2013/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 October 2013 on serious cross-border threats to health and repealing Decision No 2119/98/EC Text with EEA relevance; and website of the ECDC.

A week after their first meeting on COVID-19, the IHR Emergency Committee was reconvened and on 30 January the WHO declared the novel coronavirus a public health emergency of international concern (and it was only on 4 May 2023 that the WHO declared COVID-19 to be “an established and ongoing health issue and no longer a PHEIC” (WHO, 2023[45])).

Under the IHR, the declaration of a PHEIC enables collective global action to be further organised. A PHEIC is defined in the IHR as "an extraordinary event which is determined to constitute a public health risk in other states due to the potential for international spread of disease, and which may require co-ordinated international action" (WHO, 2008[46]). In the fifteen years preceding the COVID-19 pandemic, the WHO had only declared five events as PHEIC: the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, the Ebola outbreak in West Africa in 2013-2015, the Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 2018-2020, poliomyelitis (2014 to the present), and Zika (2016) (Wilder-Smith and Osman, 2020[47]). Whilst the declaration of a PHEIC is not in itself a reason for countries to trigger exceptional measures, it constitutes a strong message that the health risk in question is serious and unusual enough to merit close monitoring and the adoption of certain precautionary measures.

Subsequent meetings of the RAG and RMG were focused on controlling the potential for community transmission of Belgian nationals being repatriated, as well as addressing the immediate impacts of a rapidly growing number of cases on the health sector, including operational challenges linked to shortages in essential equipment. This left little room in the system for providing strategic advice on more proactive preparatory measures beyond the health sector preparations. In common with several other countries across Europe, Belgian epidemiological surveillance actors and public health emergency arrangements were not able to highlight early on, the potential scale of the challenge that COVID-19 could present to the country. Risk assessments were worded in cautious language, so as not to alarm the public, in effect contributing to an underestimation of the scale of the risk amongst decision makers.

Belgium would benefit from involving actors beyond health in the Risk Assessment Group and the Risk Management Group in order to better identify implications of public health emergencies beyond the health sector as they arise. For example, involving experts from federal public services and federated entities on topics such as economics, education, policing or environmental protection, as required. Depending on the type and duration of a health crisis, and with due consideration of the actual health risk assessment based on evidence and epidemiological data, an early assessment of possible consequences in other sectors such as economy and education should be considered.

Belgium could also establish effective links between early risk assessment and scientific advice related to public health emergencies and wider situational awareness for federal and federated authorities. Given the scale of the impacts of the pandemic, an essential part of learning the lessons from it is drawing on the experiences and insights from a wide range of organisations and public agencies. Belgium should consider involving actors beyond health in the debrief and lessons learned process for COVID-19 (but also for public health emergencies in general) and leverage their input to highlight and address gaps in preparedness (including on cross-sector collaboration).

2.3. The preparedness of Belgium's critical infrastructure operators and essential service providers

This section examines how critical infrastructure in Belgium prepared for disruptive events ahead of the COVID-19 in a system that evolved to address the protection of critical infrastructure from malicious attacks. This section then explores how the definition of what is essential for the Belgian society was expanded to encompass a much larger array of services and industries at the outset of COVID-19. Given the key role emergency services played not only in responding to COVID-19 but also in supporting the health and social care sectors during the pandemic, this section expands on the factors that contributed to their resilience.

2.3.1. A critical infrastructure resilience system geared towards infrastructure protection that still delivered enhanced preparedness for essential services and can inform efforts to enhance public sector continuity of services

The system for promoting the resilience of critical infrastructure in Belgium is primarily co-ordinated by the NCCN, working in collaboration with sectoral authorities. These co-ordination efforts extended to both the security and protection of critical infrastructure and operators of essential services. Critical infrastructure in Belgium encompasses sectors such as energy, transportation, finance, drinking water, healthcare, digital infrastructure, and electronic communications (see Annex 2.B).

Operators of essential services are subject to obligations, including the development of security plans, taking threat level-based measures, maintaining government contact points, organising exercises, and promptly reporting incidents. Even though these obligations have a strong emphasis on the protection of critical infrastructure from malicious threats, the regular practice of reviewing and refining these arrangements and the collaboration between private infrastructure providers and governmental authorities led to mature crisis management and organisational resilience arrangements across critical infrastructure in Belgium.

However, at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the government expanded the definition of which sectors were vital for the Belgian society. This vastly expanded list of vital services, and, although it had some overlap with the pre-existing definitions of critical infrastructure, it went much further (see Annex 2.B). Among the new vital services were multiple examples of both public services delivered by the State (like diplomatic and consular missions, the judiciary and meteorological and weather services) and services chiefly delivered by the private sector (for example food supply and logistics).

These new vital services found themselves having to implement a whole host of organisational resilience measures in a very reactive manner (given the absence in most cases of mature business continuity arrangements). From the public sector side, a report from the Belgian Court of Auditors sheds light as to the state of preparedness across the Federal Public Services prior to COVID-19. The report presents an in-depth review of the business continuity arrangements in place across 24 administrations examined by the Belgian Court of Audit. Out of the 24, only 16 had a pre-existing business continuity plan in place. However, knowledge of these business continuity plans seemed to be limited to technical staff responsible for their development, with some managers not being aware of the existence of continuity plans for their organisation. Preparedness across the federal administrations for a possible health crisis was, in most cases, incomplete. Whilst the public administration, on the whole, established strategies for allocating resources to carry out their public service tasks in the context of the health crisis, this was done so in chiefly reactive manner. The absence of a crisis management strategy formalised beforehand in a business continuity plan, meant that ensuring the continuity of the administrations required more resources and was made harder than it could have been (Belgian Court of Audit, 2022[48]).

Across the private operators of critical infrastructure and vital services alike, responsive infrastructure, characterised by agility, flexibility, scalability, and adaptability, played a crucial role in addressing the challenges linked to COVID-19. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, public transportation systems showcased flexibility by adjusting schedules and routes to maintain service levels while accommodating reduced passenger numbers. Belgium is encouraged to make use of insights and processes used by resilient essential services / critical infrastructure operators and providers of essential services to enhance resilience planning across all sectors and levels of government.

2.3.2. Belgium was able to ensure continuity of emergency services provision through highly adaptive incident response and co-ordination arrangements

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, the Belgian emergency services continued to provide uninterrupted support to their citizens thanks to their adaptability and the collaborative approach of the various agencies in the face of significant operational challenges.

The Belgian emergency services' preparedness for a potential disruptive event is predicated on a combination of generic response plans and business continuity plans for each organisation. The Belgian emergency response planning system is established in accordance with two main Ministerial Circulars from the Federal Public Service Interior (Ministerial Circular NPU-1 of 26 October 2006 on emergency and response plans and Ministerial Circular NPU-4 of 30 March 2009 on disciplines).

In the Belgian emergency response system, the organisation revolves around disciplines rather than specific emergency services. These disciplines are categories of tasks and responsibilities (or missions) that need to be carried out during an emergency. There is a total of five disciplines in this system, ranging from providing medical, health and psychosocial assistance, to logistical support or public information. These disciplines are not tied to specific emergency services but rather represent a framework for organising various missions. This flexibility allows different services to collaborate with each other during responses to emergencies and was instrumental in ensuring continuity of operations during COVID-19. Not only did emergency services collaborate between disciplines, but also across locations. Regular co-operation across emergency response zones also meant that no single area was overwhelmed by staff shortages or peaks in the demand for their services.

The contingency plans for the various emergency services, organised around these monodisciplinary intervention plans and multi-disciplinary arrangements, were further developed through standard operating procedures for each emergency service. Resource allocation strategies and co-ordination mechanisms involving federal, regional, and local authorities were also well established across the country prior to COVID-19. This response planning system, and the co-ordination structures that underpin it, were devised for responding to acute shocks. Nevertheless, Belgium was still able to mobilise its emergency services to support the wider health and social care sector response to the COVID-19 pandemic, whilst ensuring the continuity of essential emergency response capabilities throughout the country (Directorate-General Civil Security, FPS Interior, n.d.[49]). Fire service barracks were used as hubs for the distribution of personal protective equipment (PPE), patient transport was supported by rescue services and civil protection volunteers supported social care settings facing staff shortages due to the pandemic – to name but a few examples.

Box 2.5. Resilience of law enforcement in the face of COVID-19

In Belgium, law enforcement is delivered through the Integrated Police Service, formed by the Federal Police and Local Police. Policing (at all levels) faced numerous challenges throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, which affected both operations and the internal functioning of the various forces. In common with all essential services, Police forces were faced with the challenge of maintaining key operations while coping with reduced staffing due to absences and addressing logistical issues, like the shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE).

Prior to COVID-19, the Police forces, at both Federal and local level, had developed business continuity plans which identified critical tasks, essential processes, and the necessary personnel, ensuring that even during times of staff shortages, vital services could be upheld. These plans also emphasised the need to establish a point of contact with Federal authorities, ensuring seamless co-ordination and resource allocation.

The pandemic accelerated the digital transformation of policing in Belgium, with investments made in ICT infrastructure, including laptops, video conferencing tools, and secure access to police information. This enabled remote working and ensured that officers could access essential information while adhering to safety measures.

Source: Federal Police Service of Belgium (2021[50]), 2020 Annual Report of the Federal Police Service of Belgium.

2.4. Managing the cross-border effects of the pandemic in Belgium

Belgium's approach to addressing the international dimension of the COVID-19 pandemic included a wide range of efforts led by the Federal Public Service Foreign Affairs, Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation (FPS Foreign Affairs, hereafter), FPS Public Health and the wider set of Belgian public entities involved in the COVID-19 response. Belgium was able to provide assistance to Belgians abroad, including through the repatriation of nationals from locations across the world. The FPS Foreign Affairs led the provision of up-to-date travel advice as well as a public helpline. Nevertheless, information exchanged between the health crisis management structures and the FPS Foreign Affairs seemed to have only been used to inform the activities of the FPS Foreign Affairs. The rest of the Belgian system, including both federal and federated entities, seems to not have used intelligence coming from the FPS Foreign Affairs (including, for example, reports from embassies and consular posts regarding how control measures were being implemented by the first countries with community transmission of COVID-19) to shape preparedness during the early days of the pandemic.

Throughout the pandemic, Belgium actively engaged in partnerships aimed at strengthening healthcare systems in low- and middle-income countries. The country has been a strong advocate for a global framework, including a pandemic treaty, that prioritises robust healthcare systems, universal health insurance, and equal access to medicines. The country's multifaceted initiatives range from vaccine donation and technology transfer to strengthening healthcare systems and increasing global vaccine production.

2.4.1. The FPS Foreign Affairs performed a key role supporting Belgians abroad and helping nationals understand travel restrictions, but information from international sources could be better integrated in national crisis structures