Over the past decades, Kosovo has taken important steps to boost domestic competencies. Roll-out of competency-based curricula in primary and secondary schools has fostered progress in competency-oriented learning. Participation at all levels has been steadily increasing, especially at the primary level. Education is one of the top priorities in Kosovo, as shown by education spending at 4.6% of GDP, well above the regional average. This chapter puts forward policy priorities to sustain progress in building key competencies of both students and adults. Given its large young population and low labour market participation, boosting domestic competencies can create more job opportunities and strengthen civic participation. Kosovo has solid strategic documents, bylaws and action plans for quality assurance in education. The focus must now be on implementation, which includes strengthening capacities at the local level, increasing the number of quality assurance co-ordinators in schools, and strengthening mechanisms to work with companies, including through work-based learning. The latter can lead also to significant improvements in vocational education and training, an important education stream in Kosovo. Improving teacher training, by improving initial teacher education and providing opportunities for continuous professional development, should be another priority.

Multi-dimensional Review of the Western Balkans

5. Boosting education and competencies in Kosovo

Abstract

The Initial Assessment of this Multi-dimensional Review of the Western Balkans identified education and competencies for economic transformation as the top priorities for Kosovo and for all economies across the region (OECD, 2021[1]). While economic structures vary significantly from one economy to another, finding new sources of productivity growth and engines for future transformation is an urgent task for all the regional economies. Good jobs are scarce and young people continue to leave. Boosting youth and workforce competencies can unlock new opportunities to overcome these trends. The more unfavourable an economy’s current wage-to-productivity ratio, the more urgent it becomes to find new and more productive activities to build a strong economy.

High-quality education also tops the list of aspirations for the future in Kosovo and in the region. Quality education is an essential element of quality of life for all: young people in school, families; those who want opportunities for their own children; those who want to have children in the future; and those who depend on younger generations to shape the future of their societies. Beyond innovation and economic opportunity, education also matters for civic engagement and respect for diversity and for the rule of law. With impressive unanimity, quality education ranked topmost in all four aspirational foresight workshops held in Pristina and in the region as part of the Initial Assessment of this review (OECD, 2021[1]).1 The foresight workshops gathered a range of participants from various ministries and agencies, the private sector, academia and civil society, who developed vision statements based on narratives of the lives of future citizens.

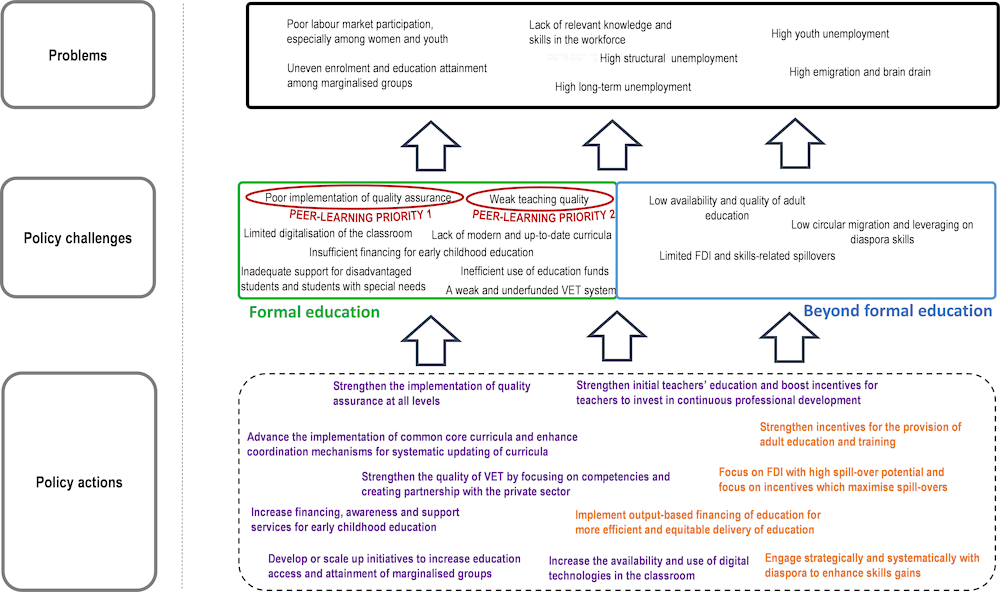

This report builds on an extensive peer-learning process with practitioners in the region and expert assessment to provide suggestions for strengthening education and competencies in Kosovo and in the region. Building on the Governmental Learning Spiral methodology (Blindenbacher and Nashat, 2010[2]), two peer-learning workshops brought together experts and practitioners from across the region and beyond to prioritise among challenges and solutions, develop ideas for action, and learn from each other (Box 2.1 of Chapter 2). The peer-learning workshops on education and competencies served three complementary aims: to identify of outcome-level challenges hampering the build-up of competencies; to identify key policy challenges; and to put forward key policy priorities for Kosovo and for the region (Figure 5.1). The report comes at an opportune moment: as Kosovo is preparing its new education strategy, the report may serve to provide direct inputs.

Over the past decade, Kosovo has taken important steps to boost the quality and relevance of education across all levels. Progress has been made in fostering more competency-oriented learning through the introduction of competency-based curricula. New curricula that focus on competencies and learning outcomes are being rolled out in primary and secondary schools. Kosovo’s Education Strategic Plan identifies critical priorities for education reform. Significant progress has been achieved in increasing education participation at all levels. With donor help, efforts have been made to improve data collection and monitoring of education policies. An assessment toolkit for evaluating teacher performance has been developed along with a framework for monitoring and evaluating the implementation of continuous professional development (CPD) programmes for teachers.

To sustain the progress in building key competencies of student and adults, Kosovo must now tackle a set of problems that remain (Figure 5.1). Performance of Kosovar students on the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) in 2018 was among the lowest in Europe. Employer surveys continuously point to significant difficulties in hiring due to skills gaps ranging from technical to meta-cognitive skills. High unemployment and limited prospects in the labour market, especially among youth, limit incentives for investment in education and skills. They are also a critical push factor for emigration and brain drain. In fact, Kosovo has one of the highest emigration rates among peer economies. Strengthening the education and competencies of both youth and the existing workforce is thus critical for creating sustainable economic prospects and unlocking a virtuous cycle that will boost employment opportunities for all, thereby helping to nurture talent and retain it within the economy (OECD, 2021[1]).

Figure 5.1. Strengthening education and competencies in Kosovo and in the Western Balkans

Note: Purple = policy actions developed by peer-learning participants. Orange = policy actions suggested by the OECD.

Source: OECD peer-learning workshops.

Eleven priority actions have great potential to strengthen education and competencies in Kosovo, with the implementation of quality assurance and training of teachers being two key peer-learning priorities (Figure 5.1):

Strengthen the implementation of quality assurance at all levels (peer-learning priority 1)

Improve teacher training for knowledge transfer (peer-learning priority 2)

Increasing the access to early childhood education

Foster equitable education at all levels

Make efficient use of education financing

Update and modernise curricula

Improve the quality and relevance of vocational education and training (VET)

Employ digital technologies in the classroom.

Increase access to and quality of adult education

Leverage foreign direct investment (FDI) to boost skills

Foster closer linkages with diaspora

This chapter is divided into three sections. Sections 5.1 and 5.2 provide policy implications across the eleven policy actions through a prism of challenges specific to Kosovo. Section 5.3 provides indicators against which progress in implementing all the policy priorities can be measured. This chapter is complemented by the regional chapter (Chapter 2) by providing more specific policy options for the key policy actions based on international practices that may be applied, albeit to different degrees, also to Kosovo.

5.1. Improving the quality and relevance of formal education in Kosovo

5.1.1. Strengthen the implementation of quality assurance at all levels through better implementation of Kosovo’s key strategic documents and involvement of various stakeholders

To improve quality, equity and efficiency of education in Kosovo, peer-learning participants selected quality assurance as an overarching priority. Based on the EU definition, quality assurance encompasses “school self-evaluation, external evaluation (including inspection), evaluation of teachers and school leaders, and student assessments” (European Commisson, 2021[3]). To strengthen implementation of quality assurance in Kosovo, peer-learning participants from Kosovo put forward specific objectives and milestones that the upcoming education strategy could build on (Box 5.1).

Kosovo has strategic documents, bylaws and action plans for quality assurance; the focus must now be on implementation. Key framework documents include the Kosovo Education Strategy for Pre-University Education, the Strategy for Quality Assurance on Pre-University Education, the National Qualification Framework and the Strategy for Teacher’s Development. Most of the strategies are accompanied by action plans and various bylaws. Peer-learning participants pointed out, however, that the current quality assurance framework is characterised by six shortcomings: weak capacities at the local levels; poor teaching capacities; low numbers of quality assurance co-ordinators in schools; limited involvement of parents in quality assurance; weak capacities of education inspectorates; and lack mechanisms to work with companies, especially when it comes to work-based learning. All of these challenges affect implementation of quality assurance.

Clarity in assigning responsibilities among levels of government remains a challenge. Existing primary legislation is not always fully transposed into secondary legislation and policies. In critical areas, such as quality assurance, lack of clarity on how relative responsibilities are divided between the Education Inspectorate and municipalities has been a major drag on progress in strengthening quality monitoring. In certain municipalities, ethnic divisions further undermine co-ordination and implementation (World Bank, 2015[4]; Aliu, 2019[5]).

Capacity and resources at the local level are especially important, given Kosovo’s decentralised education system. Directorates for Municipal Education, to which responsibility was decentralised more than a decade ago, and schools need more capacities and resources to implement quality assurance processes, such as school self-evaluation, teacher and school leader evaluation and student assessments (Aliu, 2019[5]). Many school-level quality co-ordinators reportedly lack a clear understanding of their roles, and not all carry out their responsibilities (Thaçi, Rraci and Bajrami, 2018[6]).

Systematic monitoring and evaluation remains to be improved. Some progress has been made (with the support of donors) to modernise the integrated education management information system (EMIS) with the aim of improving the collection and use of data in education policy making. Wider implementation is still needed (Aliu, 2019[5]).

Effective stakeholder engagement is critical for policy design and implementation. Forming strong partnerships, particularly with the private sector, has been an important strategic priority for Kosovo as evidenced by key strategic documents across a range of policy areas including education (Government of Kosovo, 2021[7]). In practice, however, systematic and effective engagement with the private sector and other relevant stakeholders (academia, civil society, and others) is yet to be achieved (ETF, 2017[8]). This is a cross-cutting challenge that affects all areas of education policy design from enrolment to curricula upgrades, CPD for teachers, adult learning and others. In this context, the peer-learning participants from Kosovo emphasised the importance of working with the private sector to improve work-based learning, including by strengthening the company evaluation system of students and by improving collaboration between teachers and in-company mentors.

Box 5.1. Strengthening implementation of quality assurance as an overarching policy priority

Peer-learning participants selected quality assurance as the key overarching priority in building competencies and improving educational outcomes in Kosovo. Following the regional discussions in the peer-learning workshops (Box 2.1 of Chapter 2), participants from Kosovo – representing the Prime Minister’s Office, the Ministry of Education and Science, the University of Pristina, and the Kosovo Investment and Enterprise Support Agency – gathered to identify key objectives and measures relevant for implementing quality assurance in Kosovo.

|

Objectives |

Measures |

|---|---|

|

|

Source: OECD peer-learning workshops.

5.1.2. Improving teacher training

Pear-learning participants from Kosovo selected teacher training as a key peer-learning priority to improve and boost knowledge transfer. Teachers and educators should be able not only to convey relevant knowledge, but also possess pedagogical skills, creativity, empathy and other relevant skills to support and guide students on their educational journey (Schleicher, 2015[9]). The best-performing education systems in the world are able to attract individuals of high ability into the teaching profession and effectively prepare, motivate and develop those individuals throughout their teaching career. Considering the evolving economic trends and changing needs for competencies, teachers should be able to acquire high quality initial teacher education (ITE) and have an opportunity for regular CPD.

ITE needs to have a stronger focus on skills. In Kosovo (as in other Western Balkan economies), ITE has traditionally had a strong focus on content knowledge at the expense of other critical skills, such as pedagogy, psychology, methodology and other areas. Teachers also tend to focus on traditional pedagogy with a strong emphasis on lecturing and memorisation of content. Research shows this approach tends to be poorly suited for developing the so-called “21st century competencies” including creativity, critical thinking, collaborative problem solving and communication (Jacobs and Toh-Heng, 2013[10]). Such teaching practices are also not conducive to personalised learning, which has an impact on the inclusiveness of education (OECD, 2012[11]). Recent reforms in Kosovo have focused on improving the quality of ITE. Some reforms include: adjusting programmes across all institutions that train teachers (pedagogical faculties as well as others); strengthening quality assurance in all institutions that educate teachers; introducing one-year, pre-service training for teachers trained in faculties other than the pedagogical faculty; and developing curricula for pre-service teacher training (European Commission, 2018[12]).

More financing is needed for teacher training. Currently, in-service teacher training is quite limited. In-service training providers lack capacity and resources; to date, no major efforts have been made to improve this situation. As a result, donor financing is critical to providing these training activities. Reliance on this source of funds, however, remains an important concern in terms of disaggregated financing, lack of continuity and uncertain long-term sustainability.

Boosting the attractiveness of the teaching profession remains an important challenge that Kosovo should address. On the one hand, teacher salaries have increased considerably over the past decade, from an average gross monthly salary of EUR 240 in 2010 to EUR 430 for 2016 (Aliu, 2019[5]). Despite the increases to EUR 466 for primary school teachers and EUR 515 for high school teachers (as a result of strikes in 2019) (Observatoria Balcani e Caucaso Transeuropa, 2019[13]), salaries remain below the average gross salary of EUR 600 in 2019 (World Bank/WIIW, 2021[14]). Teacher compensation is not linked to performance, which limits the incentives for highly capable people to enter the profession and for existing teachers to invest in CPD (OECD, 2020[15]). Recruitment and promotion of teachers remains (at times) politicised, not merit-based. Interviews conducted as part of this MDR revealed that the governance and political affiliation of municipal education directors can bias the selection of candidates (OECD, 2021[1]). Measures have been taken to limit such practices. In an attempt to de-politicise the process, for example, the hiring of teachers has been decentralised to school boards rather than municipal education directorates (USAID, 2017[16]).

Addressing the limitations in teacher appraisal is another important policy lever to improve teaching quality and encourage the uptake of trainings. In VET schools, for example, monitoring of teacher performance is conducted by principals and managers only – i.e. with no input from students or mentors. At present, there is little or no follow-up to the performance appraisal results (ETF, 2018[17]). Recent reforms include efforts to harmonise and strengthen the quality of teacher performance measurement across all schools, including by developing an assessment toolkit for performance evaluation and a framework for monitoring and evaluating the implementation of CPD programmes (European Commission, 2018[12]). The extent to which such tools will be systematically implemented and used to inform policy making on improving teaching quality – as well as to boost incentives for teachers to enter or invest in this profession – remains to be seen.

To support implementation of the above suggestions, peer-learning participants from Kosovo proposed several actions, milestones and activities (Box 5.2). The proposed actions, milestones and activities may be applied to different levels of education and to different stages of teachers’ education and training, including during ITE and through CPD. The proposed suggestions could be considered as an integral part of the upcoming education strategy in Kosovo.

Box 5.2. Strengthen knowledge transfer through better teacher training (peer-learning priority)

|

Actions |

Milestones and indicators |

Activities |

|---|---|---|

|

Objective testing of teacher competencies to determine needs |

|

|

|

Self-assessment of teachers |

|

|

|

Overall assessment of teacher training with stakeholder involvement |

|

|

|

Training of trainers |

|

|

|

Development of curricula based on best practices |

|

|

|

Establishment of a knowledge management system (e.g. online platform) |

|

Achieving the desired results will require both diverse partners and conditions conducive for the envisaged activities. The peer-learning participants from Kosovo emphasised the need for the following requirements:

Adding a clause in teacher contracts to make training compulsory (certificate required)

Applying for accreditation and/or licensing of training in the relevant agency

Appointing a programme co-ordinator

Setting up exams for trainees

Ensuring adequate budgeting by the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Finance

Including teacher training in the new education strategy 2021-2025

Source: OECD peer-learning workshops.

5.1.3. Increasing access to early childhood education and care (ECEC) is critical for building foundational skills for work and for life

Kosovo needs to make significant progress in increasing access to ECEC, especially in rural areas. About 37.5% of Kosovar children aged 3-5 years attended a preschool facility, which is lower than most regional peers and far below OECD (81.7%) and EU (99.9%) averages (Figure 2.15 of Chapter 2). Limited availability of publicly financed ECEC is the main constraint to participation. Kosovo spends just 4.6% of its education budget on ECEC (UNICEF, 2021[18]). As a result, there are only 43 public preschools in the entire economy, representing about one-third of all licensed kindergartens (UNICEF, 2020[19]). With 90% of all preschools located in urban areas, access is particularly limited in rural areas (Volontari Nel Mondo RTM, 2021[20]). At present, 11 municipalities lack even a single preschool institution (Gjelaj, 2019[21]). In the absence of publicly funded options, the high cost of private facilities limits participation in preschool education, particularly for children from low-income families (UNICEF, 2021[18]). Limited awareness about the benefits of ECEC and social norms regarding childcare also contribute to low enrolment, particularly in rural areas and among families from disadvantaged socio-economic backgrounds (Gjelaj, 2019[21]).

5.1.4. Fostering equitable education at all levels is essential for boosting the size and quality of the Kosovar workforce

In Kosovo, education access and attainment need to be improved for minorities, including Roma, Ashkali and Egyptian, low-income households children living in remote rural areas and children with special needs. Children from the Roma, Ashkali and Egyptian communities are particularly impacted by lower access to education. While the differences in attendance rates between the overall population and the three minority groups are not very high at the primary level (96.1% versus 84.1%), they are rather high at the secondary level (86.8% versus 31%) (Kosovo Agency of Statistics and UNICEF, 2020[22]). Across all communities, children from poor households are less likely to attend school than peers from non-poor households. The gap is particularly wide at the tertiary education level, with non-enrolment among poor students aged 16-20 being over 30-40% compared with about 25% for the entire cohort (World Bank, 2017[23]).

Strengthening the governance and co-ordination of education policy is needed to improve the efficiency and equity of education delivery across Kosovo. Roughly 10% of upper secondary school students do not complete their studies. This impacts female students more than male students: in 2017, 13.1% of female students left secondary school early compared to 11.4% of male students. While many VET graduates continue their studies in university, completion rates are even lower (ETF, 2019[24]). Once out of school, even graduates have limited options for reskilling or upskilling (see Section 5.2.1).

5.1.5. More resources and more efficient use of education financing is needed to improve learning outcomes at all levels

Limited resources hamper the quality of education in Kosovo. At 4.6% of GDP, Kosovo’s spending on education is well above average. Given the economy’s significant youth population, however, resources per student are limited (Figures 2.13 and 2.14 of Chapter 2).2 As a result, schools are often overcrowded. Many primary schools operate in two or even three shifts, limiting overall teaching time and the scope for extracurricular activities. This is particularly true in urban areas, which have seen a significant population influx in recent years. Many primary and secondary school buildings need significant renovation: the Kosovo Education Strategic Plan (2017-2021) identified 250 schools in need of renovation and estimated the need for 25 new schools to meet demand in urban areas (Government of Kosovo, 2016[25]). Limited financing for teaching materials and teacher training also have significant negative implications for the quality of learning across all levels of education (European Commission, 2014[26]).

Improving efficiencies in the spending of scarce education funds can improve learning outcomes in Kosovo. Financing for pre-university education remains based on inputs (teaching hours, teaching staff availability, class sizes and other factors) rather than on the number of students or labour market needs. Beyond the aforementioned issue of overcrowding, this has also resulted in, for example, a VET system with many obsolete profiles and poor alignment in terms of the relative number of students across various profiles with actual labour market demands (ETF, 2019[24]).

Donor funding can support education but cannot replace a stable fiscal base for the sector. Donors have played a critical role in financing efforts in Kosovo, including curriculum upgrades, teacher training, purchase of school equipment and training materials, and provision of adult education. Such support remains relatively limited and, unless scaled up and applied across the entire education system, it cannot provide significant and long-term impact.

5.1.6. Updating and modernising curricula to impart relevant knowledge and skills

Implementation bottlenecks in curricula upgrades, in both primary and secondary education, need to be resolved. Curricular reform in Kosovo began in 2009 but rollout across municipalities and schools is still ongoing. The new curriculum framework focuses on learning outcomes and competencies that are relevant and in line with both labour market needs and socio-economic and technological developments. The impact of the new curriculum has been relatively limited due to the slow pace of implementation, which began in 2013 and is still incomplete.

Closing the gap between the competency-based curriculum and teaching practice. Kosovo adopted a competency-based curriculum about ten years ago, which became mandatory as of 2018. To date, implementation has been lacking and teachers have been resistant to implement it. This relates to insufficient training (only about 40% of teachers were trained to implement the new curriculum), lack of up-to-date textbooks and insufficient science staff (Aliu, 2019[5]). These challenges, in turn, reflect underlying financing constraints as well as limited capacities in other areas within the education system, such as strategic orientation and planning (Aliu, 2019[5]).

5.1.7. Improving the quality and relevance of VET is necessary to build a qualified workforce

VET needs to be modernised and better aligned with labour market needs. VET is an important branch of the education system in Kosovo, with around half of pupils in upper secondary education choosing this track (Kosovo Agency of Statistics, 2020[27]). However, VET enrolment profiles are not necessarily well aligned with labour market needs: an estimated 47% of VET students attend programmes for which labour market demand is very limited (Kosovo Education and Employment Network, 2019[28]). In turn, outdated curricula and profiles do not prepare students for the world of work. Curricula in Kosovo’s VET schools have traditionally focused on subject and content knowledge, rather than skills. In combination with low teaching quality and lack of opportunity for practical, work-based learning, this has resulted in graduates being ill-prepared for the job market (ETF, 2019[24]).

Significant scope exists to improve the quality of VET teaching through ITE, practical training, and collaboration with private sector employers in relevant fields. Teachers in Kosovo tend to have higher formal qualifications than their peers in neighbouring economies (Figure 2.7 of Chapter 2). In a recent survey conducted by the European Training Foundation (ETF), 74% of VET teachers reported having obtained a Master’s degree or equivalent, 12% having a Bachelor’s degree and 1% having a PhD. Across all respondents, 65% stated having studied (in their formal education) the subjects they currently teach. In contrast, only 35% of VET teachers have completed ITE while 30% have neither completed ITE nor had teacher training. According to the same survey, only about half of VET teachers have regular and direct interactions with employers in their field (ETF, 2018[17]). Kosovo trails behind its regional peers when it comes to VET teachers pursuing CPD at businesses (Table 2.5 of Chapter 2). In terms of numbers, teacher-student ratios have improved in recent years but more staff are needed to handle critical tasks such as career orientation and quality management (Government of Kosovo, 2016[25])

Teaching quality can also be improved through investments in modern equipment and teaching materials as well as increased access to work-based learning. With 90% of Kosovo’s VET budget going to personnel salaries, limited funding is available for equipment and learning materials (ALLED2, 2020[29]). Respondents in the ETF survey noted – in nearly 50% of VET schools – shortages or inadequacy of instructional materials and digital and other equipment (ETF, 2018[17]). The evaluation report on implementation of the Education Strategic Plan found that adequate teaching and learning materials are available for only 24 of 135 programmes (Kosovo Education and Employment Network, 2019[28]). Limited opportunity for work-based learning through apprenticeships is another major challenge. This may reflect limited capacities both in VET schools to create those linkages but also limited capacities of local companies to provide placements for training (European Commission, 2019[30]).

5.1.8. Systematically employing digital technologies in the classroom can significantly boost education outcomes

Kosovo should improve access to digital technologies in the classroom. According to data from PISA, there are just over 0.1 computers per pupil in Kosovar schools, compared with averages of nearly 0.3 for the Western Balkans and over 0.8 in OECD countries (Figure 2.10 – Panel A of Chapter 2). Moreover, existing equipment suffers from poor maintenance. Internet access is also an issue: while nearly all school computers in OECD countries are connected to the internet, the figure for Kosovo is just over 40% (Figure 2.10 – Panel B of Chapter 2).

Weak digital skills among teachers are a major challenge that should also be considered when addressing digital skills. Although no comparable data are available for Kosovo, this is a significant challenge as confirmed by the elaboration of critical challenges in the Kosovo Education Strategic Plan 2017-2021 (Government of Kosovo, 2016[25]). Even in the EU, only one quarter or less of students are taught by teachers who feel confident using digital technology (World Bank, 2020[31]).

5.2. Boosting competencies in Kosovo beyond formal education

5.2.1. Increasing access to and the quality of adult education will be essential for creating a nimble workforce that can adapt to changes in the labour market

Flexible training provisions, statuary education and training leave, financial incentives and recognition of previous learning, and building capacities of training providers are key levers to improve participation in adult learning. In 2017, only about 4% of adults in Kosovo participated in any kind of education or training (Figure 2.16 of Chapter 2). Meanwhile, measures for upskilling and reskilling are limited to a few active labour market measures and donor initiatives (European Commission, 2019[30]). Adult education is provided by the VET schools, eight vocational training centres (VTCs) and six mobile training units. VTCs offer free, short-term courses (up to six months) that are modular and competency-based as part of non-formal education. Programmes at VET schools offer fee-based, level 4 qualifications that are classified as non-formal education for job seekers registered in employment offices, which lead to the National Qualification Framework (NQF) (Employment Agency of Kosovo, 2021[32]). None of the public VET providers offers tailor-made programmes for the private sector or industry. Capacities for adult training at the VCTs are limited and participant numbers are small; typically, the courses are short in duration and often provided at basic levels. Private VET schools offer fee-based, non-formal training programmes of up to one year, which usually include level 4 and 5 qualifications (Ministry of Education, Science and Technology, 2021[33]).

5.2.2. Leveraging on foreign direct investment (FDI) can help boost the competencies of the workforce

Kosovo can benefit from a more strategic and targeted approach to attracting FDI. Compared with the other economies in the region, Kosovo has attracted lower levels of FDI in recent years; the 3.8% of GDP reported in 2019 is slightly above an average 3.5% in the past ten years. This is similar to North Macedonia and higher only than Bosnia and Herzegovina (1.9%). (World Bank, 2021[34]). Even though Kosovo has a strategy and institutional structure for investment attraction, insufficient resources, lack of focus and inadequate inter-institutional co-ordination hamper implementation of this strategy. The Kosovo Investment and Enterprise Support Agency (KIESA) has been bestowed an ambitious mandate that includes investment and export promotion as well as support for small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and management of the economy’s special economic zones. At present, the agency lacks the capacity and resources to execute this broad mandate and does not have a clear investor or sector targeting strategy and action plan. KIESA reports directly to the National Council for Economic Development (NCED), chaired by the Prime Minister, which has the main objective of co-ordinating the activities of state institutions to eliminate barriers to doing business in Kosovo. However, the Council does not meet regularly and other inter-agency/ inter-ministerial co-ordination mechanisms are either weak or non-existent. This lack of strategic approach and resources, coupled with weak inter-institutional co-ordination, also negatively impacts aftercare services for investors, which are also in the remit of KIESA (OECD, 2021[35]).

Co-operation on training between foreign companies and education institutions exists but could be expanded given the high demand for well-trained, skilled workers. In the current labour market, foreign firms often have to train new employees to meet the required competencies of their positions before they are able to assume their roles (Hapçiu, 2017[36]). Initiatives to increase work-based learning components have been introduced in VET schools; in most cases, they are donor-driven. With the support of German development agency (GIZ), 34 professional schools collaborate with foreign and domestic companies on skills required by the companies (Jovanović, 2021[37]).

5.2.3. Fostering closer linkages with the diaspora can be a source of new competencies

To tap into diaspora as a potential source of knowledge and investment, it would be important to map the existing diaspora and foster a proactive approach in creating linkages. According to some estimates, Kosovo’s diaspora could be as large as 700 000 people – as much as 40% of the resident population (UNDP, 2014[38]). Based on the OECD DIOC database (OECD, 2016[39]), of about 167 000 persons born in Kosovo and living in OECD countries, 61.3% work in medium and highly qualified professions such as: plant and machine operators and assemblers; technicians and associate professionals; professionals; services and sales workers; and craft and related trades workers (Figure 2.18 of Chapter 2). They tend to maintain familial connections with Kosovo, visible through the large volume of remittances that flow to Kosovo every year. With remittances equalling 18.9% of GDP in 2020, Kosovo is among the 15 highest recipient countries globally (World Bank, 2021[34]; Williams, 2018[40]).

Better leveraging of knowledge and competencies accumulated abroad requires a comprehensive and central diaspora policy that covers the entire economy. Implementation and co-ordination of diaspora policy in Kosovo remains weak at the economy-wide level. Since 2011, Kosovo has a Ministry of Diaspora, in charge of investment and involvement of the diaspora. The main policy document, Strategy for Diaspora 2014-2017, and the work of the ministry have not yet led to the passing of direct policies. Rather, a number of individual activities have been implemented throughout the economy such as: business fairs and conferences with the diaspora; tax and non-tax incentives on imports; and a digital network to map the global diaspora and their motivations to emigrate. Plans for future activities exist but have not yet been implemented. The National Development Strategy envisages a database through which diaspora members can be contacted to participate in subsidised, short-term work as experts or students in companies and establishment of a TOKTEN (Transfer of Knowledge through Expatriate Nationals) scheme subsidise experts consulting in Kosovo. Kosovo is also be part of the Expert Return Programme of the German government, which enables short-term engagement of diaspora experts. To capture the full value of individual schemes, they need to be embedded in an effective and comprehensive diaspora policy that extends beyond short-term engagement (Williams, 2018[40]).

5.3. Indicators to monitor the overall policy progress in Kosovo

To monitor policy progress in implementing teacher training and other policy priorities in Kosovo, the OECD suggests a set of key indicators, including values for Kosovo and benchmark countries (either the OECD or the EU average, based on data availability). Table 5.1 provides differences between the benchmark value and the value for Kosovo.

Table 5.1. Indicators to monitor progress in implementing policy in Kosovo

2018, unless otherwise specified

|

Indicators |

Kosovo |

Benchmark value |

|---|---|---|

|

Children (aged 3-5) attending a preschool programme (%) |

13.9 |

81.7**** |

|

Mean PISA science score |

365 |

489 |

|

Students attaining at least Level 2 proficiency in reading (%) |

21 |

77 |

|

Individuals who have basic or above basic digital skills (%) |

28 |

56* |

|

Youth (aged 15 to 24) not in employment, education or training (NEET) (%) |

33.7**** |

15.5**** |

|

Teachers having at least a master’s degree in advantaged schools (%) |

36.5 |

47.2 |

|

Teachers having at least a master’s degree in disadvantaged schools (%) |

52.5 |

40 |

|

Schools where principals agree or strongly agree that an effective online support platform is available (%) |

22 |

54 |

|

Public spending on education (% of GDP) |

4.6**** |

4.9 |

|

Adult (aged 25-64) participation in education and training, formal |

- |

5.8*** |

|

Adult (aged 25-64) participation in education and training, informal |

- |

42.7*** |

Note: *2019, **2017, ***2016, ****2020. The benchmark values are based on the current OECD averages, except for Individuals who have basic or above basic digital skills and for Adult participation in education and training, where the benchmark is based on the EU average.

Source: OECD (2021[41]), PISA 2018 Database, ; World Bank (2021[34]), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators; UNICEF (2021[18]), Early childhood development – Kosovo, ; ILO (2021[42]), ILOStat (database), https://ilostat.ilo.org/data/; Eurostat (2020[43]), Database - Skills-related statistics, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/skills/data/database.

References

[5] Aliu, L. (2019), Analysis of Kosovo’s Education System, Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, Geneva, Switzerland, http://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/kosovo/15185-20190220.pdf.

[29] ALLED2 (2020), FInancial Planning for VET System in Kosovo: Proposal for Improvement, http://alled.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Financial-Planning-Final-2.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2021).

[2] Blindenbacher, R. and B. Nashat (2010), The Black Box of Governmental Learning, World Bank Group, Washington, DC, https://doi.org/10.1596/978-0-8213-8453-4.

[44] CIA (2021), “The World Factbook – Explore All Countries”, Central Intelligence Agency, Washington, DC, https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/ (accessed on 17 November 2021).

[32] Employment Agency of Kosovo (2021), Employment Agency of Kosovo, https://aprk.rks-gov.net/ (accessed on 3 August 2021).

[24] ETF (2019), Policies for Human Capital Development in Kosovo: An ETF Torino Process Assessment, European Training Foundation, Turin, Italy, https://www.etf.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2020-03/04_trp_etf_assessment_2019_kosovo_160320.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2021).

[17] ETF (2018), Continuing Professional Development for Vocational Teachers and Principals in Kosovo 2018, European Training Foundation, Turin, Italy, https://www.etf.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2020-01/kosovo_cpd_survey_2018_executive_summary_en.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2021).

[8] ETF (2017), VET Governance: ETF Partner Country Profile, European Training Foundation, Turin, Italy, http://www.etf.europa.eu (accessed on 3 August 2021).

[30] European Commission (2019), Economic Reform Programme of Kosovo (2019-2021) Commission Assessment, European Commission, Brussels, https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/sites/near/files/kosovo_2019-2021_erp.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2021).

[12] European Commission (2018), Progress Report Reform of Teacher Education and Training: Kosovo, European Commission, Brussels, https://ec.europa.eu/education/sites/default/files/tt-report-xk.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2021).

[26] European Commission (2014), Instrument for Pre-Accession Assistance (2014-2020): Kosovo EU for Education, European Commission, Brussels, https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/sites/near/files/ipa_2017_040506.11_ks_eu_for_education.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2021).

[3] European Commisson (2021), Quality assurance - Education and Training, European Commission, Brussels, https://ec.europa.eu/education/policies/school/quality-assurance_en (accessed on 28 October 2021).

[43] Eurostat (2020), Database - Skills-related statistics, (dataset), European Statistical Office, Luxembourg City, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/skills/data/database (accessed on 20 May 2020).

[21] Gjelaj, M. (2019), Preschool Education in Kosovo, Kosovo Education and Employment Network, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334896051_PRE-SCHOOL_EDUCATION_IN_KOSOVO (accessed on 2 August 2021).

[7] Government of Kosovo (2021), Economic Reform Programme (ERP), https://mf.rks-gov.net/desk/inc/media/06B63BCF-DEA0-4DE7-98D1-C99E0912272C.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2021).

[25] Government of Kosovo (2016), Kosovo Education Strategic Plan 2017-2021, https://masht.rks-gov.net/uploads/2017/02/20161006-kesp-2017-2021-1.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2021).

[36] Hapçiu, V. (2017), Skills Gap Analysis, SDC-funded Enhancing Youth Employment (EYE) project and the American Chamber of Commerce in Kosovo, Prishtina, http://helvetas-ks.org/eye/file/repository/Skills_Gap_Analysis_ENG.pdf.

[42] ILO (2021), ILOStat, (database), International Labour Organization, Geneva, https://ilostat.ilo.org/data/ (accessed on 15 May 2020).

[10] Jacobs, G. and H. Toh-Heng (2013), “Small Steps Towards Student-Centred Learning”, in Proceedings of the International Conference on Managing the Asian Century, Springer Singapore, Singapore, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-4560-61-0_7.

[37] Jovanović, B. (2021), “Getting stronger after COVID-19: Nearshoring potential in the Western Balkans”, WIIW Research Report, No. 453, Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies, Vienna, https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/240653/1/176012687X.pdf.

[27] Kosovo Agency of Statistics (2020), askdata (database), Kosovo Agency of Statistics, Pristina, https://askdata.rks-gov.net/PXWeb/pxweb/en/askdata/?rxid=4ccfde40-c9b5-47f9-9ad1-2f5370488312 (accessed on 16 April 2020).

[22] Kosovo Agency of Statistics and UNICEF (2020), 2019–2020 Kosovo Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey and 2019– 2020 Roma, Ashkali and Egyptian Communities Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey.

[28] Kosovo Education and Employment Network (2019), Mid-term Evaluation: Implementation of Kosovo Education Strategic Plan 2017-2021, Kosovo Education and Employment Network, http://kosovoprojects.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Implementation-of-Kosovo-Education-Strategic-Plan.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2021).

[33] Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (2021), “Vocational Education”, MAShT webpage, Ministry of Education Science and Technology, Government of Kosovo, Pristina, https://masht.rks-gov.net/en/arsimi-profesional (accessed on 3 August 2021).

[13] Observatoria Balcani e Caucaso Transeuropa (2019), “Kosovo, strikes and demands for better salaries”, Observatoria Balcani e Caucaso Transeuropa website, Observatoria Balcani e Caucaso Transeuropa, Trento, Italy, https://www.balcanicaucaso.org/eng/Areas/Kosovo/Kosovo-strikes-and-demands-for-better-salaries-193204 (accessed on 2 August 2021).

[35] OECD (2021), Competitiveness in South East Europe 2021: A Policy Outlook, Competitiveness and Private Sector Development, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/dcbc2ea9-en.

[1] OECD (2021), Multi-dimensional Review of the Western Balkans: Assessing Opportunities and Constraints, OECD Development Pathways, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/4d5cbc2a-en.

[41] OECD (2021), PISA Database, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/pisa/data/ (accessed on 27 September 2021).

[15] OECD (2020), Education in the Western Balkans: Findings from PISA, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/764847ff-en.

[39] OECD (2016), Database on Immigrants in OECD and non-OECD Countries, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/els/mig/dioc.htm (accessed on 13 October 2021).

[11] OECD (2012), Equity and Quality in Education: Supporting Disadvantaged Students and Schools, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264130852-en.

[9] Schleicher, A. (2015), Schools for 21st-Century Learners: Strong Leaders, Confident Teachers, Innovative Approaches, International Summit on the Teaching Profession, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264231191-en.

[6] Thaçi, J., E. Rraci and K. Bajrami (2018), The Situation of Education in the Municipalities of Kosovo - A Research Report on the Situation of Education in Nine Municipalities of Kosovo, Kosovo Education and Employment Network, Pristina, http://www.keen-ks.net/site/assets/files/1449/gjendja_e_arsimit_ne_komunat_e_kosoves_eng.pdf.

[38] UNDP (2014), Kosovo Human Development Report 2014: Migration as a Force for Development, United Nations Development Programme in Kosovo, Pristina, http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/khdr2014english.pdf.

[18] UNICEF (2021), “Early Childhood Development”, UNICEF Kosovo Programme webpage, UNICEF Kosovo Office, Pristina, https://www.unicef.org/kosovoprogramme/what-we-do/early-childhood-development (accessed on 2 August 2021).

[19] UNICEF (2020), Mapping of Early Childhood Development services in Kosovo, https://www.unicef.org/kosovoprogramme/media/1951/file/Mapping%20of%20Early%20Childhood%20Development%20services%20in%20Kosovo%20Report.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2022).

[16] USAID (2017), Kosovo Political Economy Analysis - Final Report, United States Agency for International Development, Washington, DC, https://usaidlearninglab.org/sites/default/files/resource/files/pa00n87p.pdf.

[20] Volontari Nel Mondo RTM (2021), PEDAKOS – Preschool Education Development Alliance for Kosovo, Volontari nel mondo RTM webpage, Volontari nel mondo RTM, https://www.rtm.ong/en/portfolio/pedakos-preschool-education-development-alliance-for-kosovo/ (accessed on 2 August 2021).

[40] Williams, N. (2018), “Mobilising diaspora to promote homeland investment: The progress of policy in post-conflict economies”, Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, Vol. 36/7, pp. 1256–1279, https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654417752684.

[34] World Bank (2021), World Development Indicators (database), DataBank, World Bank Group, Washington, DC, https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed on 24 June 2021).

[31] World Bank (2020), Western Balkans Economic Report: The Economic and Social Impact of COVID-19: Education, World Bank Group, Washington, DC, http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/590751590682058272/pdf/The-Economic-and-Social-Impact-of-COVID-19-Education.pdf.

[23] World Bank (2017), Republic of Kosovo Systemic Country Diagnostic, World Bank Group, Washington, DC, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/282091494340650708/pdf/Kosovo-SCD-FINAL-May-5-C-05052017.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2021).

[4] World Bank (2015), Kosovo Education System Improvement Project, World Bank Group, Washington, DC, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/823281467991937253/pdf/PAD1015-PAD-P149005-IDA-R2015-0232-1-Box393188B-OUO-9.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2021).

[14] World Bank/WIIW (2021), SEE Jobs Gateway (database), World Bank Group/Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies, Washington, DC/Vienna, https://wiiw.ac.at/see-jobs-gateway-database-ds-5.html (accessed on 22 September 2021).

Notes

← 1. Due to the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, the foresight workshop was not held in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

← 2. Currently, about one-quarter of Kosovo’s population (24%) is aged 0-14 years, significantly higher than in the neighbouring economies of Albania (15.4%), Bosnia and Herzegovina (13.0%), Montenegro (18.1%), North Macedonia (16.2%) and Serbia (14.1%) (CIA, 2021[44]).