This chapter presents key policy priorities to ensure a green recovery in Kosovo through reducing its high carbon- and energy-intensities in an equitable way. In the Western Balkans, Kosovo has the highest share of coal in electricity generation. Kosovo can achieve important gains on emissions reduction and energy access by making energy efficiency a policy priority, by strengthening financing for energy efficiency in buildings, and by incentivising more energy efficient heating systems. Kosovo is starting to exploit its significant potential for intermittent renewables, such as solar and wind. To build on this initial progress, it needs to improve the enabling environment and introduce market-based support mechanisms for renewables, eliminate remaining subsidies for coal, and render its electricity system more flexible. It would also be important to reduce its high transmission and distribution losses. To be part of the global energy transition, with associated international goodwill and access to foreign financing, Kosovo requires greenhouse gas emissions targets in line with international good practice. This needs to be supported by an inclusive and effective strategy for a low-carbon transition.

Multi-dimensional Review of the Western Balkans

17. A green recovery in Kosovo

Abstract

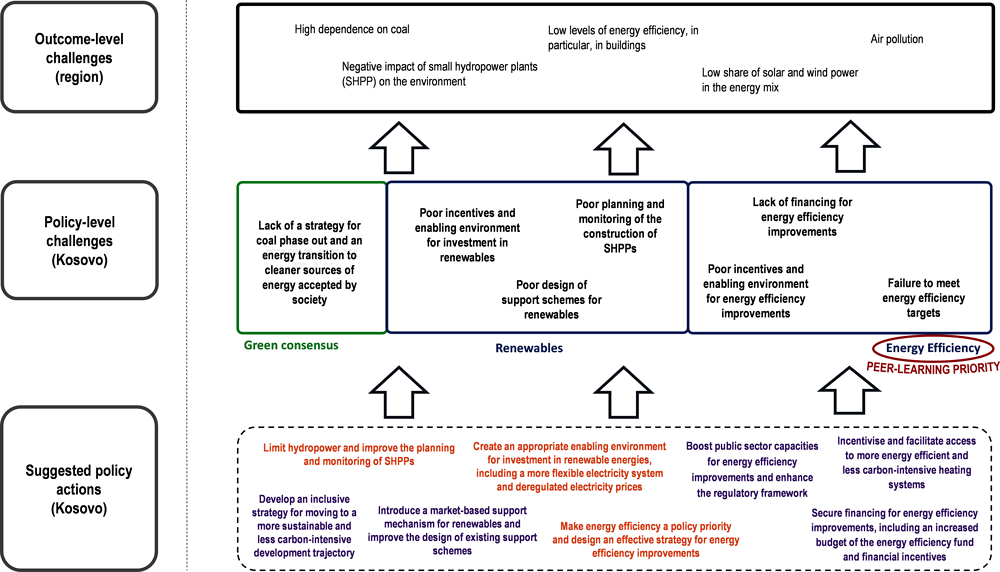

The Initial Assessment of the Multi-dimensional Review (MDR) of the Western Balkans identified a green recovery as a top policy priority for Kosovo and the Western Balkan region as a whole. Energy and air pollution are complex challenges and significant obstacles to future economic development and well-being. Air pollution, unreliable access to clean energy and unsustainable environmental practices were identified as key constraints in Kosovo and the Western Balkan region in the Initial Assessment. High carbon intensiveness, in combination with low levels of energy efficiency, result in considerable air pollution and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in Kosovo. The share of renewables in Kosovo’s energy mix remains low. Building on the initial assessment, the “From Analysis to Action” phase of the project provides policy suggestions to ensure green recovery in Kosovo and in other Western Balkan economies. The peer-learning workshops on green recovery served three complementary aims: to identify of problems hampering the green recovery; to identify key policy challenges; and to put forward key policy priorities for Kosovo and for the region (Figure 17.1).

Kosovo has already taken different measures for a green recovery, across several dimensions. Most notably, Kosovo has several strategic documents outlining its energy and climate policies, including the Kosovo’s Economic Reform Programme 2021-2023 and a Climate Change Strategy 2019-2028. In addition, Kosovo has a Law on Energy Efficiency (2018) and a Law on the Energy Performance of Buildings (2016). To make heating more energy efficient, Kosovo is already in the process of modernising and expanding its district heating systems. To improve access to financing for energy efficiency measures, the Kosovo Energy Efficiency Fund (KEEF) was operationalised in 2020. To promote the use of renewable energies, Kosovo has already set up several renewable support mechanisms, including a net-metering scheme for renewables self-consumers (prosumer) and feed-in tariffs (FiTs).

To ensure fully green recovery, Kosovo must now tackle a set of important challenges that remain. Kosovo does not yet have an inclusive and clear strategy for phasing out coal and embarking on a transition to cleaner sources of energy. Going forward, Kosovo’s revised Energy Strategy 2022-2031 could define a decarbonisation trajectory once this strategic document has been finalised. Further, Kosovo is still in the process of creating an enabling environment for investment in renewable energies; and to date, poor design of support schemes discourages investors and is costly for Kosovo’s government. Small hydropower plants (SHPPs) have negative impacts on the environment, due to inadequate planning and monitoring of the construction process. To date, Kosovo has not been able to meet its energy efficiency targets; this reflects a lack of financing as well as insufficient incentives and enabling conditions for energy efficiency improvements (Figure 17.1).

Figure 17.1. Towards a green recovery in Kosovo and the Western Balkans

Note: Purple = policy actions developed by peer-learning participants. Orange = policy actions suggested by the OECD.

Source: OECD peer-learning workshops.

Eight policy priorities have great potential to ensure green recovery in Kosovo, with policy actions related to energy efficiency being the key priorities. These policy priorities reflect the issues raised by the peer-learning participants from Kosovo at the green recovery peer-learning workshop:

Make energy efficiency a policy priority and design an effective strategy for energy efficiency improvements (peer-learning priority)

Incentivise and facilitate access to more energy efficient and less carbon-intensive heating systems (peer-learning priority)

Secure financing for energy efficiency improvements, including an increased budget of the Energy Efficiency Fund and financial incentives (peer-learning priority)

Boost public sector capacities for energy efficiency improvements and enhance the regulatory framework (peer-learning priority)

Develop an inclusive and effective strategy for moving to a more sustainable and less carbon-intensive development trajectory

Introduce market-based support mechanisms for renewables and improve the design of existing support schemes

Create an appropriate enabling environment for investment in renewable energies, including a more flexible electricity system and deregulated electricity prices

Limit hydropower in Kosovo and improve the planning and monitoring of SHPPs.

This chapter is divided into nine sections. Sections 17.1 through 17.8 provide policy implications across the eight policy priorities through a prism of challenges specific to Kosovo. Section 17.9 provides indicators against which progress in policy implementation in Kosovo can be measured. This chapter is complemented by the regional chapter (Chapter 14), which provides more specific policy options for the policy priorities, based on international practice that may be applied, with necessary adaptations, also to Kosovo.

17.1. Make energy efficiency a policy priority and design an effective strategy for energy efficiency improvements in Kosovo

Kosovo has succeeded in meeting its energy efficiency target for 2020. Kosovo’s Law on Energy Efficiency targets a final energy consumption not exceeding 1 566 kilotonnes of oil equivalent (ktoe) in 2020 (Ministry of Economic Development, 2019[1]). Even though Kosovo’s final energy consumption has increased over the last decade (by 18.7 % from 1 278.7 ktoe in 2011 to 1 517.6 ktoe in 2020), Kosovo has been able to meet this target (Eurostat, 2021[2]).

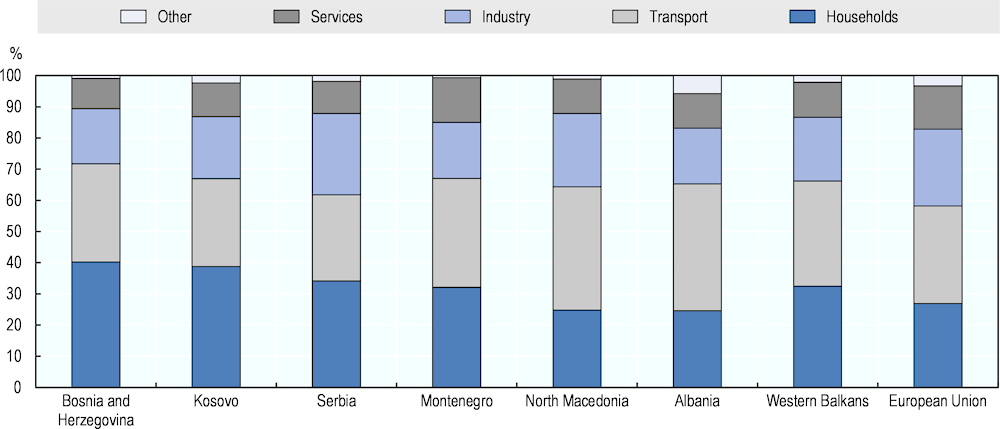

Lack of insulation in residential buildings, coupled with inefficient and energy-intensive heating systems, result in high energy demand by the residential sector in Kosovo. Households account for the largest share of final energy consumption – 38.7% compared with averages of 32.4% in the region and 26.9% in the European Union (Eurostat, 2021[2]) (Figure 17.2). Kosovo’s residential sector accounted for 54% of electricity consumption, compared with 49% on average in the Western Balkans and 28% in the EU (2018) (IEA, 2021[3]).

Figure 17.2. Households’ energy consumption is high in Kosovo

Improving the energy efficiency of residential buildings would not only contribute to decarbonisation, but also reduce energy bills and energy poverty. Only 9% of homes in Kosovo are equipped with energy efficient materials, appliances and equipment (EBRD, 2016[4]). The housing stock is outdated and lacks insulation; and even more recent buildings were often built with little regard to energy efficiency standards (EBRD, 2016[4]). Over 60% of all homes in Kosovo were built in the 1970-2000s; about 15% were built before 1970 while just over 20% have been built since 2000. The majority of homes are 12 to 42 years old.

Low energy efficiency in electricity production in Kosovo’s power plants results in high transformation losses. Kosovo has the highest transformation losses in the region; they make up 36.3% of primary energy consumption compared with a Western Balkan average of 25.3% and 21.3% in the EU (see Figure 14.7 of Chapter 14). Outdated energy infrastructure also leads to high distribution losses – equivalent to 3.9% of primary energy consumption, against 3.4% (on average) in the Western Balkans and 1.7% in the EU (Eurostat, 2021[2]).

Kosovo requires a comprehensive strategy for energy efficiency in buildings. In recent years, Kosovo has formulated important policy and strategy documents for energy efficiency; however, the policy framework remains fragmented. Kosovo’s Economic Reform Program 2021-2023 includes energy efficiency improvements as the first structural measure to support economic competitiveness. But the programme lacks ambition: concrete measures focus primarily on implementing already approved grants and loans. The Economic Reform Programme also fails to examine structural challenges to energy efficiency and to define a clear strategy for addressing them. At present, budgetary resources allocated to energy efficiency improvements are very limited. Kosovo drafted its fourth National Energy Efficiency Action Plan (NEEAP) 2019-2021, but it has not yet been adopted. The NEEAP outlines energy efficiency objectives and energy efficiency policies, including an energy efficiency obligations scheme (Energy Community Secretariat, 2020[5]). Kosovo adopted a Law on Energy Efficiency in 2018 and a Law on the Energy Performance of Buildings (05/L-101) in 2016. It has also prepared a draft building renovation strategy. At the time of writing, this strategy had not been adopted (Ministry of Economic Development, 2019[1]). Kosovo does not have a legal framework and strategy for reducing electricity transmission and distribution (T&D) losses.

17.2. Incentivise and facilitate access to more energy efficient and less carbon-intensive heating systems

Energy efficiency measures to reduce energy consumption were identified by peer-learning participants as a top priority for Kosovo. Measures for energy efficiency improvements in buildings – most importantly, by households – were prioritised by participants. Specific measures included providing subsidies to households, expanding district heating systems and promoting heat pumps (Box 17.1). Modernising space heating is crucial for improved energy efficiency in buildings in Kosovo.

Less reliance on fuelwood and a shift to more energy efficient modes of heating could foster energy efficiency in Kosovo. Renewables and waste (mainly fuel wood) account for 86.1% of space heating in Kosovo compared with 61.4% (on average) in the region and only 17% in the EU (see Figure 14.8 of Chapter 14). Electricity accounts for another 10.4% of space heating.1 Total 2019 energy consumption by households in Kosovo is dominated by biomass (58.9%) and electricity (37%), reflecting widespread use of fuel wood and electricity for space heating (Kosovo Agency of Statistics, 2021[6]). Only 3-5% of households are equipped with central heating installations; the vast majority use individual, inefficient devices for both heating and cooking, mainly burning fuel wood but also coal. This results in high energy consumption and in important indoor and outdoor air pollution, posing a risk to human health and the surrounding environment. Kosovo could consider banning lignite for residential heating to reduce air pollution.

Modernising Kosovo’s district heating systems, and integrating more renewables and natural gas into them, could render these systems more efficient and less polluting. Four municipalities in Kosovo have district heating systems (Pristina, Gjakova, Mitrovica and Zveqan) (Kosovo Ministry of Economic Development, 2017[7]). These systems rely predominantly on coal (94%) and to a lesser extent on petroleum products (6%) (Energy Community Secretariat, 2020[5]). It is estimated that 15% to 20% of heat produced is lost during delivery. The Pristina district heating system is served by a heating plant, which is supplied by fuel oil boilers and waste heat from the Kosovo B lignite power plant (274 megawatts [MW]). Expansion plans for the Pristina system include the addition of 29 MW of solar thermal energy and improvements to reduce heat losses. The Gjakova system’s oil-fired heating plant has been replaced with biomass cogeneration (based on wood waste) in 2021 (Balkan Green Energy News, 2021[8]; Energy Community Secretariat, 2020[5]; Wynn and Flora, 2020[9]). Kosovo has started assessing its potential for highly efficient cogeneration district heating and cooling systems in eight municipalities, as required by the Energy Efficiency Directive (EED).

Expanding access to district heating is another key measure. At present, district heating accounts for only 3% to 5% of heating in Kosovo (Kosovo Ministry of Economic Development, 2017[7]). Expanding its application could reduce use of inefficient heating devices, resulting in energy savings and lower GHG emissions and air pollution (Balkan Green Foundation, 2020[10]). Kosovo should conduct a cost-benefit analysis to determine where such systems should be installed.

Reforming district heating billing to reflect actual heat consumed could encourage more energy savings. Kosovo has a dual model of billing for heating (metered and unmetered). Currently, unmetered billing prevails in Kosovo’s district heating systems, which means charges are based on space size and independent of actual heat consumption (Energy Community Secretariat, 2020[5]). Unmetered billing tends to result in excessive heat consumption.

Incentives for installing heatpumps could contribute to the roll-out of more energy efficient heating systems. Financial incentives could trigger households and businesses to replace inefficient heating devices with heat pumps in regions where district heating systems are not planned. The relatively high investment required is a primary barrier to switching to heat pumps or to replacing inefficient devices that have not yet reached the end of their lifespan with more efficient ones.2

Box 17.1. Outcomes of the green recovery peer-learning workshop – Kosovo

Participants from Kosovo (representing government, the private sector and civil society) at the OECD green recovery peer-learning workshop identified reducing energy consumption by 26% by 2030 - the target of 26% has been defined by peer-learning participants and is not an official target, primarily through energy efficiency measures, as the top priority for the economy. They suggested an action plan that could complement current policy efforts, specifically suggesting six actions with corresponding targets and measures.

Table 17.1. Reduce energy consumption by 26% by 2030 through energy efficiency measures

Action plan, targets and measures

|

Actions |

Targets and measures |

|---|---|

|

Action 1: Subsidise households for energy efficiency measures, including specific social programmes for vulnerable consumers |

|

|

Action 2: Build district heating in four other cities beyond Pristina |

|

|

Action 3: Promote heat pumps in households and buildings |

|

|

Action 4: Reduce technical and commercial electricity losses |

|

|

Action 5: Implement energy efficiency measures in public and private new and old buildings |

|

|

Action 6: Launch regulatory and fiscal reform of the transport sector to improve energy efficiency |

|

Source: OECD peer-learning workshops.

Peer-learning participants suggested a variety of measures to improve energy efficiency in buildings. They recommended development of incentive measures for improvements in residential and commercial buildings such as fiscal incentives – for example by lowering VAT rates – on renewable equipment and installation (including for heat pumps), Participants also suggested undertaking feasibility studies on district heating as well as building renovation (including development of a comprehensive strategy), promotion of renewables in buildings (including renewable self-consumption) and transport sector reform.

The need to improve access to finance for energy efficiency improvements was particularly stressed by participants. They highlighted the importance of increasing the budget capacity of Kosovo’s Energy Efficiency Fund. Specific measures suggested include: establishing energy service companies (ESCOs) to finance energy efficiency services; developing green loans for the private sector and households; and government support (such as partial loan guarantees) for green loans by commercial banks.

Finally, participants also emphasised the importance of improving the regulatory framework for energy efficiency and the need to strengthen planning and monitoring of the implementation of such measures – including those outlined in strategic documents. They recommended stronger legal regulations on reducing technical electricity losses as well as stricter inspection and verification of the compliance of buildings with energy efficiency standards.

Note: The target of 26% has been defined by peer-learning participants and is not an official target.

Source: OECD peer-learning workshops.

17.3. Secure financing for energy efficiency improvements

Despite significant financial contributions for energy efficiency improvements by EU and international donors, current investment levels in Kosovo remain very low compared with funding needs. Investment needs in energy efficiency in Kosovo between 2011 and 2020 were estimated at EUR 328 million; in fact, Kosovo invested only EUR 135 million in energy efficiency in buildings between 2010 and 2021 (Energy Community Secretariat, 2020[5]). This lack of funding means that planned measures cannot always be implemented. Kosovo planned a range of improvements in the buildings sector for 2019-20, including in residential houses (e.g. installation of thermostatic heat valves) and multi-apartment buildings. However, as the government did not allocate budgetary resources to these measures, their implementation was dependent on external funding (Balkan Green Foundation, 2020[10]). The Millennium Foundation Kosovo (MFK) committed to finance part of these measures and has started project implementation.

Scaling up the Kosovo Energy Efficiency Fund (KEEF) and making private and residential buildings eligible for funding are vital steps. The KEEF was operationalised in 2020 with the aim of providing municipalities with financial resources to carry out energy efficiency improvements in 30 public buildings per year. At his rate, it would take 20 years to implement improvements across Kosovo’s entire public building stock. At present, commercial and residential buildings are not eligible for KEEF funding. In a relevant example from the region, Croatia established an energy efficiency fund – the Fund for Environmental Protection and Energy Efficiency – that allocates financial resources to public, private and commercial buildings. The Croatian fund also supports (among others) the purchase of new, energy efficient vehicles and expansion of recycling capacity (FONDZIN, 2021[11]).

Kosovo requires financial incentives and better access to private financing for energy efficiency improvements in residential and commercial buildings. Financing energy efficiency improvements is often a challenge for households in Kosovo, particularly the poorest and most vulnerable. Investment costs are high in relation to average salaries. Financial incentives for investing in energy efficiency are still at the very early stages of development in Kosovo and could be scaled up significantly. Scope also exists to improve access to private financing for energy efficiency improvements: at present, loans for such work are difficult to obtain and characterised by high interest rates.3

17.4. Boost public sector capacities for energy efficiency improvements and enhance the regulatory framework

Energy efficiency criteria should be incorporated in public procurement processes. Public institutions in Kosovo often acquire buildings, goods and services with low levels of energy efficiency. It is frequently a challenge for contracting authorities to compile technical information on energy efficiency in the first phase of tendering. Public institutions could strengthen their ability to account for energy efficiency criteria and to conduct life-cycle cost analysis in procurement processes (Balkan Green Foundation, 2020[12]). Kosovo’s Law 2003/17 on Public Procurement allows for incorporating life-cycle cost analysis and best price-quality ratios (including energy efficiency criteria) in procurement processes. These principles have not yet been integrated in secondary legislation (European Commission, 2019[13]). During the construction phase of public buildings and implementation of public services, monitoring and oversight could be strengthened to leverage opportunities for energy efficiency improvements (Balkan Green Foundation, 2020[12]).

ESCOs could facilitate energy efficiency improvements in buildings. ESCOs are companies that deliver energy efficiency projects using the money from cost reductions on subsequent energy savings to finance the projects. Deployment of ESCOs in Kosovo could be facilitated by introducing model contracts and by streamlining provisions on the duration of service and selection criteria for ESCOs in the Public Procurement Law and the Law on Public Private Partnerships (Balkan Green Foundation, 2020[12]). In order to align its legal framework with the 2014 EU Directive on Public-Private Partnerships and Concessions, Kosovo is currently in the process of developing secondary legislation on ESCOs and model contracts for ESCOs (Kosovo Energy Efficiency Agency [KEEA]) (European Commission, 2019[13]).

To be able to lead the energy efficiency agenda, Kosovo’s public sector staff need to be more informed on the topic. At present, Kosovo’s public sector lacks capacities in key areas such as in planning and implementation of energy efficiency measures and for inspection and verification of compliance with energy efficiency standards in buildings. This stalls progress: for example, the plan to install new district heating systems in eight municipalities in 2019 did not start on time since the feasibility study could only be considered for 2020.4

17.5. Develop an inclusive strategy for moving to a more sustainable and less carbon-intensive development trajectory

Kosovo faces the dual challenge of needing to reduce its high carbon- and energy-intensities while also stimulating economic development. A full 94.95% of Kosovo’s electricity is generated from coal; not surprisingly, its energy intensity and GHG emissions per unit of gross domestic product (GDP) are among the highest in the Western Balkan region (Eurostat, 2021[2]; Kosovo Environmental Protection Agency, 2020[14]; World Bank, 2021[15]). At the same time, Kosovo’s GDP per capita is the lowest in the region: EUR 4 230 compared with a regional average of EUR 5 872 and EUR 34 769 in the EU (all numbers in constant 2010 USD) (World Bank, 2021[15]).

To be part of the global energy transition, with associated international goodwill and access to foreign financing, Kosovo needs to establish greenhouse gas emissions targets in line with international good practice. Currently, Kosovo does not have a GHG emissions reduction target. Kosovo is not a signatory of the United National Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) (Ministry of Economy and Environment, 2020[16]) and is not party to the Paris Agreement yet. The establishment of GHG emissions targets needs to be supported by an inclusive and effective strategy for a low-carbon transition. Setting targets that are consistent with international good practice would show commitment to the transition, and thus reduce the chances of Kosovo becoming economically marginalised as the European Union proceeds on its European Green Deal and Border Carbon Adjustment Mechanism.

Revising Kosovo’s Energy Strategy to have a sharp focus on renewables and energy efficiency is important. Kosovo’s Energy Strategy for 2017-2026 (approved in January 2018) has a stated aim to further develop the sector and support economic development while protecting human health, social well-being and the environment.5 The Strategy aims to construct a new large thermal power plant (TPP) and to rehabilitate the TPP Kosovo B, but lack of funding has delayed the start of construction. In 2018, the World Bank – the primary funder of the new TPP – decided to withdraw from the project (Balkan Green Foundation, 2020[10]). Given the numerous challenges Kosovo is facing and the failure to start construction of the new TPP, a review of the Energy Strategy is ongoing: Kosovo is in the drafting phase of a revised Energy Strategy (2022-2031), which aims to lead the way towards decarbonisation. In October 2021, a working group for the revision of the Energy Strategy was established.

Kosovo requires a strategy to replace coal by less-polluting alternatives, including renewables, and enhancing energy efficiency measures. Planned closure of the TPP Kosovo A by 2030, as demand for electricity is expected to increase, would require additional generation capacity of 3 300 GWh annually by 2030 (Wynn and Flora, 2020[9]). Kosovo could add an additional 1 500 GWh of annual capacity through solar and wind power in combination with energy storage (this is in addition to 400 GWh of solar and wind power annually already in the planning pipeline or under construction). Conservative estimates suggest Kosovo could save electricity amounting to at least 1 400 GWh by 2030 by reducing T&D losses (800 GWh) and investing in energy efficiency improvements in buildings (600 GWh). If the interconnection capacity with Albania is scaled up and regional market integration is deepened, an additional 1 000 GWh could be imported (IEEFA, 2020[17]). Different options are being evaluated in terms of costs and benefits as part of the process of the revision of Kosovo’s Energy Strategy.

Kosovo should prioritise implementation of a GHG monitoring, reporting and verification mechanism and finalisation of its National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP). An NECP is a key strategic document for laying out an energy transition strategy. Kosovo has adopted the legal basis for preparing and adopting its NECP, and has set up a national working group and six thematic working groups to draft the NECP. Drafting and analytical work has started with international support. Policy scenarios and projections for GHG emissions reduction have been defined but target setting has not yet started (Energy Community Secretariat, 2020[5]; Energy Community Secretariat, 2021[18]). Kosovo is planning to adopt the final version of its NECP in 2024.

Implementing strategic documents on climate and energy policies is vital, most importantly, the climate strategy and action plan. Kosovo has already several strategic documents outlining its energy and climate policy. Kosovo’s Economic Reform Programme 2021-2023 includes measures targeted at the energy sector, with key aims to reduce consumption through energy efficiency measures and to increase the diversity of energy sources (Government of Kosovo, 2020[19]). The government has developed a Climate Change Strategy 2019-2028, and an action plan outlining policy measures for climate change mitigation and adaption. Kosovo voluntarily joined the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, thereby committing to the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Other strategic documents include a National Energy Efficiency Action Plan (NEEAP) 2019-2021 (not adopted yet) and a National Renewable Energy Action Plan (NREAP 2011-2020), which establishes renewable energy targets and measures to support their deployment (Energy Community Secretariat, 2020[5]).

The government should take step to better include the private sector, academia and civil society in energy and climate policy making. Building a consensus that includes all relevant stakeholders is important for an effective energy transition from coal to less-polluting alternative sources of energy in Kosovo. The National Council of Economic Development of Kosovo (NCED) (established in 2015) serves as a forum for public-private dialogue, including on energy and climate policy. The NCED is chaired on an alternating basis by the Prime Minister and the Minister of Trade and Industry; it brings together the most important representatives of the private sector, relevant government ministries and state agencies. One of its key aims is to eliminate barriers and address challenges faced by investors in Kosovo. The NCED does not deal exclusively with energy and climate policies – they are among a range of topics being discussed. At present, the NCED does not include stakeholders from academia and civil society – an oversight that should be corrected (NCED, 2019[20]).

Scope exists to improve implementation of environmental impact assessments (EIAs) for energy infrastructure, and to enhance public participation in the infrastructure planning process. Implementation and quality control of EIAs and other environmental reports remain challenges in Kosovo, as does early and effective public participation in energy infrastructure planning. Kosovo’s legal framework for EIAs is not fully compliant with EU legislation (Directive 2014/52/EU) (Energy Community Secretariat, 2020[5]), which mandates EIAs for the installation of oil and gas pipelines, natural gas storage, production of liquid and gaseous hydrocarbons, and coal gasification and liquefaction plants. EIAs must be submitted by the project proposer to the competent authority and must contain a minimum of information (IEA, 2021[21]).6

17.6. Improve the design of support schemes for renewables in Kosovo

Boosting the share of renewables in Kosovo’s energy mix is an integral part of the green recovery process. In 2019, renewables accounted for only 5.05% of electricity generation in Kosovo while 94.95% was generated from coal. Within the renewables share, hydropower accounts for 67.7% of electricity generated, wind power for 28.9% and solar energy for only 3.4% (Eurostat, 2021[2]). There are 13 medium and large hydropower plants in Kosovo, with the largest (Ujmani) having a capacity of 35 MW (Balkan Green Foundation, 2019[22]). Between 78 and over 90 SHPPs operate in Kosovo (Balkan Green Foundation, 2019[22]; CEE Bankwatch Network, 2015[23]). Kosovo has signed the Energy Community Treaty and adopted EU Directive 2009/28/EC on the promotion of renewable energies. Kosovo’s NREAP aimed at 25% of renewables in gross final energy consumption by 2020 – somewhat below the voluntary target of 29.47% set in 2013 (Optima Energy Consulting, 2021[24]; Ministry of Economic Development, 2020[25]). In 2019, the lower goal had been achieved, with renewables amounting to 25.69% of gross final energy consumption (Eurostat, 2021[2]). However, this is below Kosovo’s voluntary target for 2020 and Kosovo is not on track towards the EU target for its member countries of 40% of renewables in gross final energy consumption by 2030 (Optima Energy Consulting, 2021[24]).

Scope exists to scale up wind and solar energy in Kosovo. Kosovo has an average theoretical potential for solar photovoltaic (PV) energy of 3.85 kilowatt hours per square meter (kWh/m2) (ESMAP, 2020[26]). Its first large-scale wind and solar projects were launched recently (IEEFA, 2020[17]). The first major wind farm, the 32MW Kitka plant, started operating in late 2018. In December 2019, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) approved a loan for the 105 MW Bajgora plant (CEE Bankwatch Network, 2021[27]). Construction is planned for several large solar power plants. Performance data for these projects show that Kosovo has considerable potential for wind and solar energy – and is even performing in line with peer and neighbouring economies (IEEFA, 2020[17]).

A market-based support mechanism for renewables could enhance the efficiency of support for renewables in Kosovo. Under Kosovo’s current renewable energy support scheme (Rule 10/2017 - Support Scheme for Renewable Energy Sources Generators), renewable capacities are awarded to investors based on administratively fixed FiTs. However, since December 2020, FiTs have been suspended in Kosovo (Energy Community Secretariat, 2021[18]). Previously, administratively fixed FiTs for wind and solar power have evolved slowly, even though the cost of solar and wind power has been falling significantly in recent years (Lajqi et al., 2020[28]). In renewable energy auctions, as an alternative to administratively fixed FiTs, investors would compete by bidding for the lowest possible price for electricity. This competitive bidding process would improve transparency in the selection of investors for renewable projects and could result in lower prices (Energy Community Secretariat, 2020[5]; Jakupi, 2020[29]). Kosovo is currently working on the legal framework for a market-based support mechanism for renewables (Energy Community Secretariat, 2021[30]). In a relevant example, Germany successfully shifted from FiTs to a market-based support scheme between 2012 and 2017 – initially using a feed-in premium, then renewable auctions (Bundesnetzagentur, 2016[31]).

Installation of rooftop PV systems for self-consumption could significantly increase electricity supply from solar power in Kosovo. Households, industrial and commercial electricity consumers represent considerable untapped potential for installing solar PV for self-consumption (E3 Analytics, 2020[32]). As part of its renewable energy support scheme, Kosovo has established a net-metering scheme for self-consumers with an installed capacity up to 100 kilowatts (kW) (prosumers) (Rule 10/2017 - Support Scheme for Renewable Energy Sources Generators). However, in the first three years (early 2017 to early 2020) of this regulation being in place, only an estimated 20 permits were issued to construct solar PV projects for self-consumption (E3 Analytics, 2020[32]). As of early 2022, there were 119 renewable self-consumers in Kosovo. Since part of the electricity they consume is produced on site, increasing the number of prosumers could reduce network (T&D) losses.

Lifting the voltage threshold to 35 kV would enable a wider range of electricity consumers to benefit from Kosovo’s renewable energy support scheme for self-consumers. Currently, only electricity consumers connected to the grid at 0.4 kV are eligible for Kosovo’s net metering scheme. This limits the group of beneficiaries mainly to households and very small companies, thereby severely constraining the potential market for customer-sited PV systems. Many electricity consumers that would be interested in installing such systems are commercial and industrial consumers currently connected to the grid at voltage levels above 0.4 kV (E3 Analytics, 2020[32]).

Shifting from net-metering to net-billing could enhance the efficiency of support for renewables self-consumers. Kosovo currently uses a net-metering scheme to support self-consumers of renewables (net-metering is settled in kWh while net-billing is settled in monetary terms). Under the current net-metering scheme, within each billing period, electricity prosumers receive a one-for-one electricity credit in kWh corresponding to the kWh exported to the grid. Under a net-billing scheme, they would receive a one-for-one monetary credit for every kWh exported to the grid, which would be subtracted from their electricity bill (Haziri, 2019[33]). This monetary scheme would correct the fact that Kosovo’s current net-metering scheme does not allow prosumers to recover the fixed cost of using the distribution system (which is borne by all customers, including non-prosumers). Under a net-billing scheme, prosumers would receive a reference price for electricity fed into the grid – taking into account the fixed cost of using the distribution grid – while paying the retail price for their electricity consumption (USAID/Kosovo, 2019[34]; E3 Analytics, 2020[32]).

Simplifying and accelerating the procedure for construction of new renewable energy generation facilities would make them more attractive to investors. At present, this procedure consists of three main steps: obtaining preliminary authorisation, obtaining final authorisation and connection to the grid. The procedure can take up to three years. As a result, some electricity producers who apply for Kosovo’s renewable energy support scheme and receive an allocation of generation capacity are ultimately unable to meet their initially proposed implementation timeline. In turn, this can cause investment delays (E3 Analytics, 2020[32]).

Scope exists to improve co-ordination among institutions involved in the administrative and permitting process for renewables, as well as to reduce the number of institutions implicated. Administrative and permitting procedures for renewables involve a large number of institutions, including the Energy Regulatory Office (ERO), the Ministry of Environment and Spatial Planning (MESP), Kosovo Transmission, System and Market Operator (KOSTT) and Kosovo Distribution System Operator (KEDS) (Ministry of Economic Development, 2020[25]). In 2018, Kosovo adopted the legal basis for creating a one-stop shop for renewable energy projects; the inter-institutional co-ordination commission (including all institutions involved in the administrative process for renewable investments) for establishing this one-stop shop was set up in May 2019 (Energy Community Secretariat, 2020[5]). To date, the facility is not yet operational.

17.7. Create an appropriate enabling environment for investment in renewable energies

Kosovo requires a more flexible electricity system to respond quickly to large fluctuations in electricity supplied from variable renewables. Kosovo’s current electricity mix is very inflexible: 94.95% of electricity is produced from inflexible TPPs, which are slow to shut down and turn on again (Eurostat, 2021[2]). Quickly dispatchable power plants (e.g. gas-fired or biomass), better interconnection with neighbouring economies, and energy storage could make Kosovo’s electricity system more flexible. Kosovo’s interconnections with neighbouring economies are not very well developed but are in the process of being improved: a new 400 kV interconnection line with Albania was built between 2014 and 2016 and started operation in 2020. Construction of additional interconnection lines with neighbouring economies may prove difficult due to the unresolved conflict between Kosovo and Serbia (Wynn and Flora, 2020[9]).

Higher electricity prices in Kosovo – in line with production costs - would encourage more households to invest in rooftop PV systems to become self-consumers. Electricity prices in Kosovo are currently regulated and subsidised. Subsidies for coal amounted to EUR 1.22/MWh in Kosovo in 2018‑19, compared with EUR 1.26/MWh as the Western Balkans average. Subsidies amounted to EUR 6.6 million in 2019 – a sharp reduction from EUR 38.1 million in 2015. Thus, while subsidies remain high in Kosovo, they are now much lower than in Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina (Miljević, 2020[35]). Further, electricity prices in Kosovo were increased in 2022: Kosovo doubled electricity prices for households consuming over 800 kWh/month (Balkan Green Energy News, 2022[36]).

Kosovo requires a workforce with the right skills for scaling up renewable energies. Shortages exist for skilled workers for installation of renewables (particularly solar panels), maintenance and quality assurance in Kosovo (E3 Analytics, 2020[32]). Although public and private universities in Kosovo offer various programmes with green curricula, they fall short in developing skills related to environmental engineering (e.g. carrying out EIAs, performing site assessments to ensure compliance with environmental codes and regulations, resource management, waste minimisation and minimising the risk of environmental hazards).

17.8. Limit hydropower in Kosovo and improve the planning and monitoring of SHPPs

Potential for hydropower in Kosovo is limited; further development poses risks to the environment. Kosovo constructed at least seven new hydropower plants between 2009 and 2018 (CEE Bankwatch Network, 2019[37]). However, the economy has only 2 100 m3 of renewable water resources per capita per year (m3/capita/year), equivalent to just 13.95% of the Western Balkan average. As such, it is the only economy in the region that is close to water stress levels (1 700 m3/capita/year) (OECD, 2021[38]). Kosovo’s rivers are not rich in water flow. Available evidence indicates that new and existing hydropower plants have negative impacts on the environment and local communities, and contribute to degradation of riverbeds (Lajqi et al., 2020[28]). Hydropower plant construction, operation and ancillary activities in Kosovo frequently destroy aquatic ecosystems. At present, 50% to 60% of SHPPs are located in protected areas (Balkan Green Foundation, 2019[22]; CEE Bankwatch Network, 2015[23]).

Scope exists to improve the planning and monitoring of the construction of SHPPs in Kosovo. Most SHPPs are not sufficiently well planned, partly because of incomplete and low-quality data on hydrology. In turn, the allocation of licenses for SHPPs lacks transparency and the plants often fail to fulfil environmental standards. The consequence is that many SHPPs withdraw more water than is sustainable and lack measures to protect aquatic ecosystems. Ancillary activities, such as road construction and upgrade, are also a threat to biodiversity (USAID, 2018[39]). SHPPs contribute to soil erosion and reduce ground and surface water levels, drying out rivers in some cases. Local residents sometimes lose access to water for drinking and agricultural activities. In 2018, the government imposed a moratorium on construction of new hydropower plants until a new assessment of the availability of ground and surface water could be completed (Balkan Green Foundation, 2019[22]).

17.9. Indicators to monitor the overall policy progress in Kosovo

To monitor progress in implementing policies for a green recovery in Kosovo, the OECD suggests a set of key indicators, including values for Kosovo and benchmark economies (either the OECD or the EU average, based on data availability; Croatia is the benchmark for the number of renewable self-consumers per 100 000 population) (Table 17.2).

Table 17.2. Indicators to monitor progress in implementing policies in Kosovo

2019, unless otherwise specified

|

Indicator |

Kosovo |

Benchmark value |

|---|---|---|

|

CO2 emissions per capita (tons per capita) |

**4.98 |

**7.64a |

|

CO2 emissions per unit of GDP (kg/USD 2015 PPP) |

**0.4707 |

**0.1867a |

|

Mean exposure to PM 2.5 air pollution (µg/m3) |

****24.80 |

13.90a |

|

Years of life lost (YLL) per 100 000 inhabitants attributable to exposure to PM2.5 pollution |

*****2 375 |

*****1 074b |

|

Subsidies for coal (EUR/MWh) |

1.22 |

- |

|

Market share of the largest generator in the electricity market (% of total electricity generation) |

100.00 |

44.79b |

|

Renewables (% of electricity generation) |

4.95 |

34.94b |

|

Solar and wind (% of electricity generation) |

1.59 |

17.66b |

|

Renewable self-consumers per 100 000 population |

*3.15 |

**36.93c |

|

Space heating using renewables and waste (fuelwood) (% of total) |

***86.10 |

***27.00b |

|

Transformation and distribution losses (% of primary energy consumption) |

40.16 |

22.92b |

Note: *2021, **2020, ***2018, ****2017, *****2016. aOECD, bEU, cCroatia.

Source: Eurostat (2021[2]), Eurostat (database), https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/; IEA (2021[40]), Data and statistics, www.iea.org/data-and-statistics; EEA (2019[41]), Air quality in Europe — 2019 report, www.eea.europa.eu/publications/air-quality-in-europe-2019; Energy Community Secretariat (2021), www.energy-community.org/regionalinitiatives/WB6/Tracker.html; Miljevic (2020[35]), Investments into the past, https://energy-community.org/dam/jcr:482f1098-0853-422b-be93-2ba7cf222453/Miljevi%25C4%2587_Coal_Report_122020.pdf; Miljević, Mumović, Kopač (2019[42]), Analysis of Direct and Selected Indirect Subsidies to Coal Electricity Production in the Energy Community Contracting Parties, https://www.energy-community.org/dam/jcr:ae19ba53-5066-4705-a274-0be106486d73/Draft_Miljevic_Coal_subsidies_032019.pdf; Slok, M. (2021[43]), Incentives and challenges in promoting self-consumption - The case of Croatia, www.energy-community.org/; World Bank (2021[15]), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators.

References

[36] Balkan Green Energy News (2022), Kosovo doubles electricity prices for households, https://balkangreenenergynews.com/kosovo-doubles-electricity-prices-for-households/ (accessed on 13 October 2021).

[8] Balkan Green Energy News (2021), Gjakova in Kosovo switches district heating to biomass, https://balkangreenenergynews.com/gjakova-in-kosovo-switches-district-heating-to-biomass/ (accessed on 13 October 2021).

[10] Balkan Green Foundation (2020), Implementation of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Policies and Requirements, Balkan Green Foundation, Kosovo.

[12] Balkan Green Foundation (2020), Improvement of public procurement standards to increase energy effciency in Kosovo, Balkan Green Foundation, Kosovo.

[22] Balkan Green Foundation (2019), Hydropower Plants in Kosovo - the problems and their real potential, Balkan Green Foundation, Kosovo, https://www.balkangreenfoundation.org/uploads/files/2020/July/13/Hydropower_Plants_in_Kosovo_the_problems_and_their_real_potential1594649058.pdf.

[31] Bundesnetzagentur (2016), RES Support Scheme & Development in Germany, Bundesnetzagentur, Bonn, https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/efa2da49-4576-49c1-840d-0bde4dd736c3/S2-4-BNETZA_Stefan_Arent_RESGermanyII.pdf.

[27] CEE Bankwatch Network (2021), The Energy Sector in Kosovo, CEE Bankwatch Network, Prague, https://bankwatch.org/beyond-coal/the-energy-sector-in-kosovo (accessed on 13 October 2021).

[37] CEE Bankwatch Network (2019), Western Balkans hydropower - Who pays, who profits?, CEE Bankwatch Network, Prague, https://bankwatch.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/who-pays-who-profits.pdf.

[23] CEE Bankwatch Network (2015), Financing for hydropower in protected areas in Southeast Europe, CEE Bankwatch Network, Prague, https://bankwatch.org/sites/default/files/SEE-hydropower-financing.pdf.

[32] E3 Analytics (2020), Scaling-up Distributed Solar PV in Kosovo: Market Analysis and Policy Recommendations, E3 Analytics, Berlin, https://www.e3analytics.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/E3A_Country-Report_Kosovo.pdf.

[4] EBRD (2016), Country Strategy for Kosovo, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development.

[41] EEA (2019), Air quality in Europe — 2019 report, European Environment Agency, http://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/air-quality-in-europe-2019.

[18] Energy Community Secretariat (2021), Annual Implementation Report, Energy Community Secretariat, Vienna, Austria, https://www.energy-community.org/implementation/IR2021.html (accessed on 13 October 2021).

[30] Energy Community Secretariat (2021), WB6 Energy Transition Tracker, Energy Community Secretariat, Vienna, Austria, https://www.energy-community.org/regionalinitiatives/WB6/Tracker.html.

[5] Energy Community Secretariat (2020), Annual Implementation Report, Energy Community Secretariat, Vienna, Austria, https://www.energy-community.org/implementation/IR2020.html.

[26] ESMAP (2020), Global Photovoltaic Power Potential by Country, World Bank, Washington, DC, https://globalsolaratlas.info/global-pv-potential-study.

[13] European Commission (2019), Kosovo 2019 Report - Communication on EU Enlargement Policy, European Comission, Brussels, https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/system/files/2019-05/20190529-kosovo-report.pdf.

[2] Eurostat (2021), Eurostat (database), European Statistical Office, Luxembourg City, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database (accessed on 13 October 2021).

[11] FONDZIN (2021), General website, Fond za zastitu okolisa i energetsku ucinkovitost, https://www.fzoeu.hr/ (accessed on 3 July 2021).

[19] Government of Kosovo (2020), Economic Reform Programme 2021-2023, Government of Kosovo.

[33] Haziri, P. (2019), Regulatory framework on Prosumers in Contracting Parties; Working, ECRB Customers and Retail Markets, Energy Community Regulatory Board, London, https://www.ceer.eu/documents/104400/6688968/Petrit+Haziri%2C+ERO+-+Regulatory+framework+on+Prosumers+in+Contracting+Parties/2426d3a6-4e98-cab1-e09c-338ecc8a12c0?version=1.0.

[40] IEA (2021), Data and statistics, (database), International Energy Agency, Paris, https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/.

[3] IEA (2021), Kosovo, International Energy Agency, Paris, https://www.iea.org/countries/kosovo (accessed on 13 October 2021).

[21] IEA (2021), Policies, International Energy Agency, Paris, https://www.iea.org/policies/13772-legislative-decree-16-june-2017-no-104?q=Directive%202014%2F52%2FEU&s=1 (accessed on 13 October 2021).

[17] IEEFA (2020), Beyond Coal: Investing in Kosovo’s Future Energy, Intstitute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, Cleveland, https://ieefa.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Beyond-Coal_Investing-in-Kosovos-Energy-Future_October-2020.pdf?utm_source=rss&utm_medium=rss&utm_campaign=beyond-coal_investing-in-kosovos-energy-future_october-2020.

[29] Jakupi, M. (2020), Solar Energy Potential In Kosovo: Pilot study of installation with photovoltaic modules at The University of Prishtina, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, http://kth.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1476743/FULLTEXT01.pdf.

[6] Kosovo Agency of Statistics (2021), Askdata, https://askdata.rks-gov.net/PXWeb/pxweb/en/askdata/?rxid=4ccfde40-c9b5-47f9-9ad1-2f5370488312.

[44] Kosovo Agency of Statistics (2015), Energy Consumption in Households, 2015, https://ask.rks-gov.net/en/kosovo-agency-of-statistics/add-news/energy-consumption-in-households-2015 (accessed on 13 October 2021).

[14] Kosovo Environmental Protection Agency (2020), Kosovo Environment 2020 Report on Environmental Indicators, Republic of Kosovo, Pristina, https://www.ammk-rks.net/repository/docs/Mjedisi_i_Kosov%C3%ABs_2020_Raport_i_treguesve_mjedisor%C3%AB_-_ANGLISHT.pdf.

[7] Kosovo Ministry of Economic Development (2017), Energy Strategy of the Republic of Kosovo 2017-2026.

[28] Lajqi, S. et al. (2020), “Analysis of the Potential for Renewable Utilization in Kosovo Power Sector”, Environments, Vol. 7/6, p. 49, https://doi.org/10.3390/environments7060049.

[35] Miljević, D. (2020), Investments into the past - An analysis of Direct Subsidies to Coal and Lignite Electricity Production in the Energy Community Contracting Parties 2018–2019, Energy Community Secretariat, Vienna, Austria, https://energy-community.org/dam/jcr:482f1098-0853-422b-be93-2ba7cf222453/Miljevi%25C4%2587_Coal_Report_122020.pdf.

[42] Miljević, D., M. Mumović and J. Kopač (2019), Analysis of Direct and Selected Indirect Subsidies to Coal Electricity Production in the Energy Community Contracting Parties, Energy Community, https://www.energy-community.org/dam/jcr:ae19ba53-5066-4705-a274-0be106486d73/Draft_Miljevic_Coal_subsidies_032019.pdf.

[25] Ministry of Economic Development (2020), National Renewable Energy Action Plan for the Republic of Kosovo 2011-2020 Update for 2018-2020, Ministry of Economic Development, Kosovo, https://rise.esmap.org/data/files/library/kosovo/Renewable%20Energy/Kosovo_National%20RE%20Action%20Plan.pdf.

[1] Ministry of Economic Development (2019), National Energy Efficiency Action Plan 2019-2021.

[16] Ministry of Economy and Environment (2020), Kosovo Environment 2020 Report of environmental indicators.

[20] NCED (2019), About us, National Council for Economic Development & Secretariat, https://nced-ks.com/en (accessed on 13 October 2021).

[38] OECD (2021), Multi-dimensional Review of the Western Balkans: Assessing Opportunities and Constraints, OECD Development Pathways, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/4d5cbc2a-en.

[24] Optima Energy Consulting (2021), 2030 EU Renewable Target Requirements - Kosovo Position, Optima Energy Consulting, Prishtina, http://www.optima-ec.com/en/new-renewable-target-requirements-which-are-necessary-mechanism-to-adopt-/ (accessed on 13 October 2021).

[43] Slok, M. (2021), Incentives and challenges in promoting self-consumption - The case of Croatia, https://www.energy-community.org/ (accessed on 20 January 2022).

[39] USAID (2018), Kosovo biodiversity analysis, USAID.

[34] USAID/Kosovo (2019), Repower - Kosovo, DT Global, Washington, DC, https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00WDV3.pdf.

[15] World Bank (2021), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed on 24 June 2021).

[9] Wynn, G. and A. Flora (2020), Beyond Coal: Investing in Kosovo’s Energy Future, Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, Cleveland, https://ieefa.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Beyond-Coal_Investing-in-Kosovos-Energy-Future_October-2020.pdf?utm_source=rss&utm_medium=rss&utm_campaign=beyond-coal_investing-in-kosovos-energy-future_october-2020.

Notes

← 1. According local data, wood accounts for 70.35% of space heating in residential buildings in Kosovo, electricity for 18.18%, coal for 7.10%, central or local systems (district heating) for 4.02% and other sources for 0.35% (Kosovo Agency of Statistics, 2015[44]).

← 2. Information from fact-finding in Kosovo from expert consultants from CENER21.

← 3. Information from fact-finding in Kosovo from expert consultants from CENER21.

← 4. Information from fact-finding in Kosovo from expert consultants from CENER21.

← 5. The strategy is based on five objectives: i) a sustainable and quality supply of electricity and a stable electricity system; ii) integration in the regional energy market; iii) enhancing existing capacities of TPPs and building new capacities; iv) development of natural gas infrastructure; and iv) fulfilment of objectives and obligations in the fields of energy efficiency, renewable energy sources and environmental protection.

← 6. A project description, including location, design, size and other relevant information; a description of the likely significant impacts on the environment through construction and operation phases; a description of measures to avoid, prevent, reduce or offset likely environmental impacts; and a description of reasonable alternatives considered, adapted to the project and its specifications.