This chapter presents the key findings and recommendations of the second volume of the Multi-dimensional Review of the Western Balkans. It focuses on boosting education and competencies; fostering social cohesion; and ensuring a green recovery and energy transition. In view of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, the chapter also provides a brief analysis of the socio-economic impact of the crisis.

Multi-dimensional Review of the Western Balkans

1. Overview: Making the Western Balkans an attractive place to live, work and invest in

Abstract

The Western Balkan economies are currently at an important crossroads in their development trajectory. In the decade leading up to the global financial crisis of 2008, most economies in the region experienced dynamic growth and financial sector expansion. Leveraging on their well-educated labour force and deep relationships with Europe and many parts of the world, the regional economies opened up and attracted significant investments. As a result, income increased and living standards improved. The European Union (EU) integration process has been a central driver of democratisation, peace and institution building, and has opened up many opportunities for the region. Yet the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis – and, recently, the COVID-19 pandemic – also revealed challenges that hinder the region’s progress. Finding new sources of productivity growth and new engines for economic and structural transformation is an urgent task for all economies. Underperforming labour markets leave many citizens with no attractive opportunities, and inequalities and large pockets of poverty persist. Heavy dependence on coal as an energy source and other environmentally unstainable practices have resulted in high air pollution and other impacts that negatively affect the quality of life in the region.

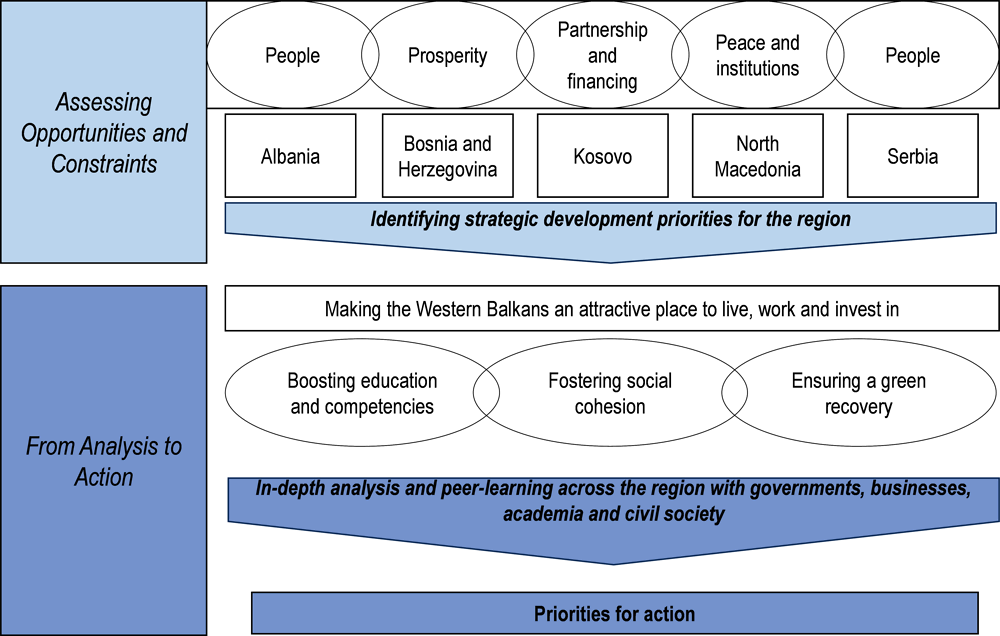

This Multi-Dimensional Review (MDR) combines deep diagnostics by experts with peer-learning among key economic actors and policy makers to support the achievement of inclusive and sustainable development in the Western Balkan region as a whole and in its individual economies. Five economies – Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, North Macedonia and Serbia – participated in the MDR process, which consisted of two phases (initial assessment phase, and peer-learning and solutions phase) and two reports. The first report, Assessing Opportunities and Constraints (OECD, 2021[1]) applied the “5P” diagnostic framework (people, prosperity, partnerships, planet and peace) of sustainable development, and was published in June 2021. The present report, From Analysis to Action, combines in-depth analysis of policy options with the results of an extensive peer-learning process (Box 1.1) across three strategic priorities: boosting education and competencies for economic and civic transformation; fostering social cohesion; and pursuing a green transition that reduces negative environmental impacts. It provides policy recommendations and suggestions for the development and/or implementation of development strategies at economy or regional level, as well as frameworks against which co-operation partners can devise their support (Figure 1.1).

Creating opportunities and providing a good quality of life are key to making the region an attractive place to live in, work in and invest in. Taken together, the three strategic priorities set the foundation for creating opportunities for everyone. In order to best cover the regional and economy-level challenges and opportunities, this report comprises 19 chapters. The first one, this regional overview, summarises key findings, highlights priority recommendations, and assesses the impacts of the COVID‑19 pandemic. Each strategic priority is further developed in a dedicated section with a thematic regional chapter and economy-specific chapters for Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, North Macedonia and Serbia.

Figure 1.1. Multi-dimensional review of the Western Balkans – Process schematic

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Box 1.1. The Multi-Dimensional Review of the Western Balkans – from Analysis to Action through peer-learning based on the Governmental Learning Spiral

The first ever OECD Multi-dimensional Review at a regional scale, the MDR of the Western Balkans combines economy- and region-level perspectives to propose policy action across the region. Focussing on the strategic priorities identified by initial diagnostics, peer-learning events in early 2021 convened experts from the participating economies, the OECD and other international experts to generate knowledge and ideas for solutions.

The peer-learning process followed the governmental learning spiral approach, with two overarching aims for each thematic area (education and competencies, social cohesion and a green recovery): to identify obstacles to progress, and to put forward key policy actions at the regional and economy-level on the most important and urgent issues. The peer-learning workshops also provided an opportunity to exchange policy experiences.

The MDR process brought together about 90 experts from the five Western Balkan economies (Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, North Macedonia and Serbia), representing various societal perspectives, including government institutions, civil society, academia and businesses. The results of the peer-learning workshops guided the three thematic parts of this publication – each of which is covered in a regional chapter of this publication. In turn, topic-specific suggestions for actions are presented in the individual economy chapters.

Source: Blindenbacher and Rielaender (forthcoming[2]), How Learning in Politics Can Work; Blindenbacher and Nashat (2010[3]), The Black Box of Governmental Learning The Learning Spiral - A Concept to Organize Learning in Governments, World Bank Group, Washington, DC, https://doi.org/10.1596/978-0-8213-8453-4.

Whenever relevant and subject to data availability, the Western Balkan economies are compared with three groups of benchmark economies identified among the members of the Development Centre of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD): 1) a relevant subset of member countries of the OECD, including Costa Rica, the Czech Republic, Greece, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia and Turkey; 2) non-OECD countries that are members of the European Union with similar socio-economic characteristics, including Croatia and Romania; and 3) countries that are in some way comparable but not members of either organisation, including Kazakhstan, Morocco, the Philippines and Uruguay. The selection of benchmark economies is based on geographical proximity, similarities in historical contexts and economic structures, mutual partnerships and, as relevant, similar paths towards EU integration. The selection of non-OECD economies is based on similar economic and social challenges (such as high migration rates), shared history as transition economies, and similar development patterns. Such a broad set of benchmark economies brings additional perspectives to the Western Balkan economies and create valuable learning opportunities across selected policy dimensions. Criteria for selection are summarised in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1. OECD Development Centre member countries used as benchmark countries in the current report

|

OECD |

European Union |

Other regions |

Population, total (millions) |

GDP (EUR billions) |

GDP per capita (current USD) |

Relevance for the Western Balkans |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Czech Republic |

✔ |

✔ |

10.7 |

246.5 |

23 102 |

Proximity, industrial base |

|

|

Greece |

✔ |

✔ |

10.7 |

209.9 |

19 583 |

Proximity, agro-food sector, tourism |

|

|

Slovak Republic |

✔ |

✔ |

5.7 |

105.4 |

19 329 |

Proximity, industrial base |

|

|

Slovenia |

✔ |

✔ |

2.1 |

53.7 |

25 739 |

Proximity, industrial base |

|

|

Turkey |

✔ |

83.4 |

754.4 |

9 042 |

Proximity, agro-food sector, export basket |

||

|

Croatia |

✔ |

4.1 |

60.4 |

14 853 |

Proximity, agro-food, tourism |

||

|

Romania |

✔ |

19.4 |

250.1 |

12 920 |

Proximity, industrial base |

||

|

Costa Rica |

✔ |

5.1 |

61.8 |

12 238 |

Agriculture, IT services, history of FDI attraction |

||

|

Kazakhstan |

✔ |

18.5 |

180.2 |

9 731 |

Agriculture, mining, SOEs |

||

|

Morocco |

✔ |

36.5 |

118.8 |

3 204 |

Migration and diaspora in the EU, labour market challenges, role of FDI |

||

|

Philippines |

✔ |

108.1 |

376.8 |

3 485 |

Migration as a key feature of the economic model |

||

|

Uruguay |

✔ |

3.5 |

56.1 |

16 190 |

Agriculture, textiles |

Note: IT = information technology, FDI = foreign direct investment, SOEs = state-owned enterprises

Source: World Bank, (2021[4]), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators.

1.1. Three strategic priorities for more opportunities and better quality of life in the Western Balkans

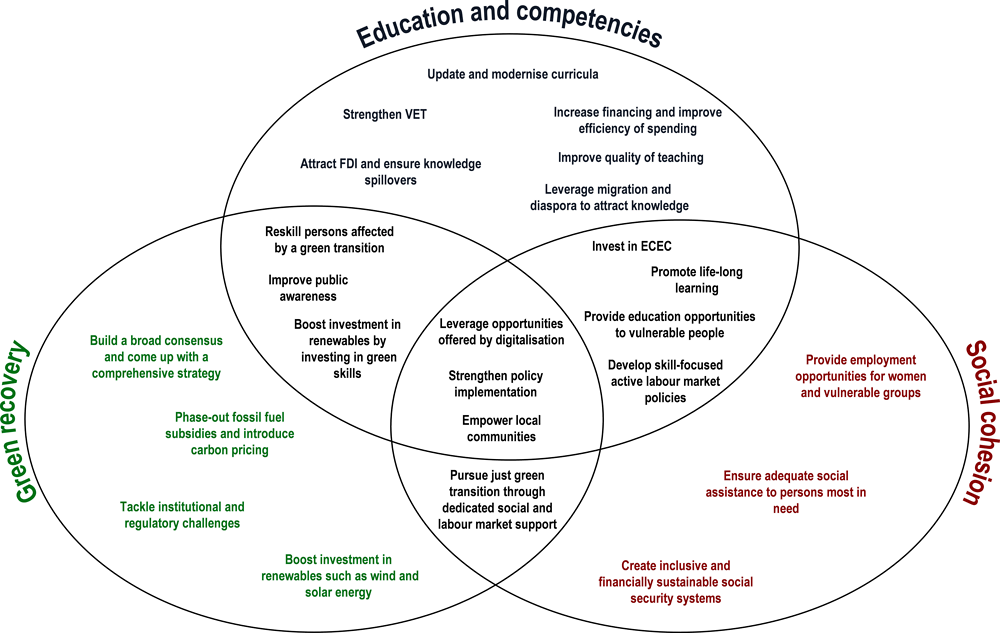

This report suggests three priority actions to create opportunities and improve the quality of life in the Western Balkans (Figure 1.2).

First, to ensure opportunity-focused growth, Western Balkan economies should prioritise education and competencies for economic transformation and civic participation. Boosting education and competencies are shared regional priorities for raising productivity, creating jobs, encouraging civic participation and making the region an attractive destination for businesses and people. Across the region, citizens demand high quality education as a top component of quality of life. Quality education helps build competencies that are key to help the region unleash creativity and leapfrog to new economic activities. Education systems also play a key role in building civic engagement skills, providing a foundation for responsible and community-minded citizens. By promoting trust among people, fighting exclusion and facilitating collective action in important areas (such as social protection), more effective mechanisms to boost education and competencies can ultimately reinforce democracy and contribute to social cohesion.

Second, strategies that promote people-focused growth can strengthen social cohesion.1 A very large share of citizens in the region continue to face economic hardship and feel excluded. Many cannot find good employment – especially in rural areas, where life can be hard. Lack of attractive employment opportunities can strain citizens’ ability to support each other. Low levels of formal labour market participation render the mostly contribution-based social protection systems unsustainable and under-dimensioned. Local governments should be on the frontlines of addressing the education and competencies challenge; efforts are stalled, however, by a lack of capabilities in terms of organisation, incentives and funding.

Third, a green recovery, in which more sustainable energy delivers cleaner air, is indispensable for boosting the region’s quality of life and economic opportunities. The capital cities of Western Balkan economies are among the most polluted in Europe, largely because coal continues to dominate energy production. With the implementation of the European Green Deal and the Paris Agreement on climate change, demand for cleaner energy is accelerating and both trading partners and investors are becoming more selective. Energy reform may indeed come with substantial costs and social challenges, but the status quo is not an option, as the coming into effect of carbon pricing and other policy measures will dramatically increase the costs of the region’s current coal- and lignite-based energy systems in the near to medium term. In sharp contrast, a strategic effort to radically reduce air pollution by phasing-out these sources would make the region healthier and more attractive.

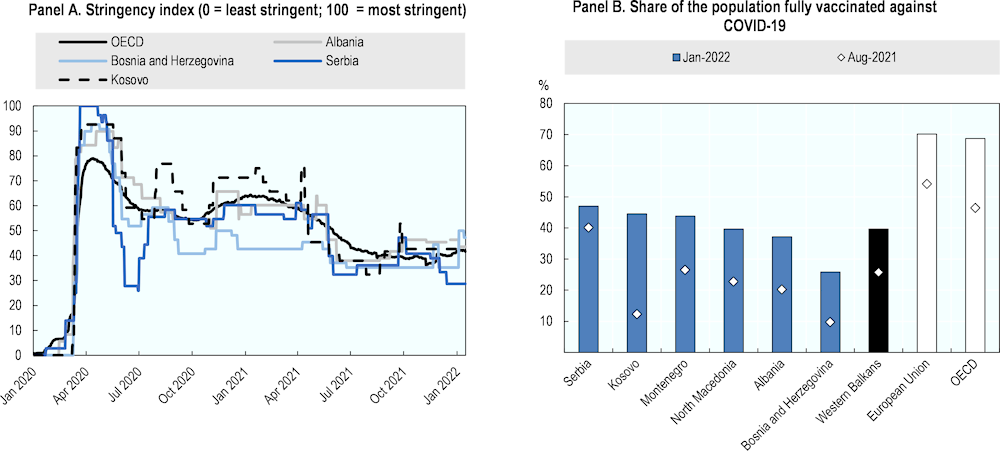

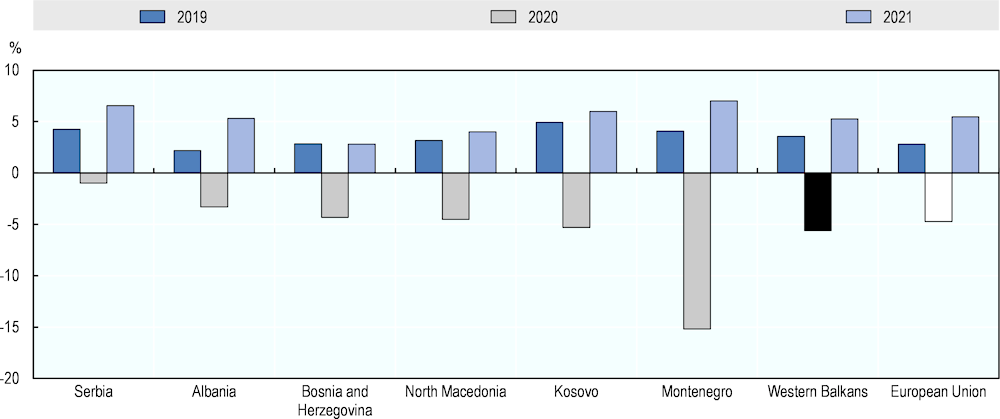

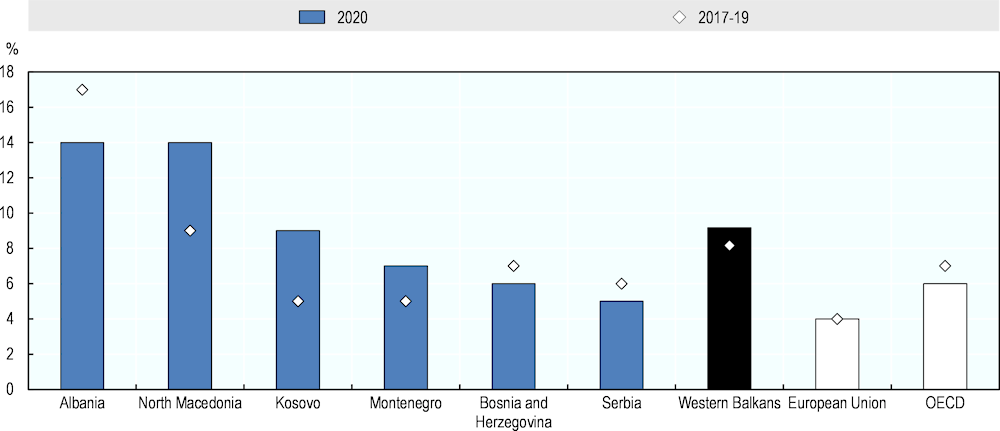

In light of the COVID-19 pandemic and its huge social and economic implications, now is the time to find innovative solutions to create opportunities and improve quality of life. At time of writing, the COVID-19 situation continues to evolve both globally and locally; governments must continue to develop and implement responses in real time. The need to stimulate recovery makes strategic questions and relevant funding allocations more urgent, not least because given the large amount of resources required, missed opportunities will carry much higher costs than they would otherwise. The suggested policy priorities in this report can support the post-pandemic recovery by making recovery spending as strategically effective as possible.

Figure 1.2. Boosting education and competencies, fostering social cohesion, and ensuring a green recovery: Theme-specific and cross-cutting policy recommendations

1.1.1. Optimising returns to policy by focussing on synergies

Strengthening linkages between education policies, and social and labour market policies should be a high on any policy agenda. Providing high-quality and affordable early childhood education and care (ECEC) is an investment in the future from two perspectives. For one, access to ECEC contributes significantly to building the foundational skills of children, which are crucial at later stages of education. From a social-cohesion perspective, it can release valuable time for women, allowing them to invest in education, participate in employment or engage in entrepreneurial activities. Likewise, in any dynamic and transformative economy, people should have a chance to acquire new skills or to reskill throughout their lifetime. Creating synergies between life-long learning policies and active labour market policies will ramp up availability of skills in demand and unlock employment opportunities for many people, especially the young and long-term unemployed. This will foster greater social cohesion across different age groups while reducing the burden of social assistance expenditures. Finally, considering the large share of vulnerable groups in the region, including ethnic minorities and people with disabilities, creating opportunities by which they can access high quality education can vastly improve their chances for social integration and to prosper in the labour market.

Well co-ordinated and effective social and labour markets policies can cushion the potential socio-economic impacts of green recovery policies and can smooth out the clean energy transition. Reform of energy pricing, a priority for a green recovery in the Western Balkans, may lead to short- to medium-term increases in energy expenditures, with potentially significant impacts on vulnerable households. As such, energy pricing and other relevant policies should include social protection elements (e.g. using carbon pricing revenue to mitigate distributional implications for households, or to finance support for structural adjustment of workers and communities).

Likewise, education and green transition policies should be integrated to build green skills, re-skill persons affected by the green transition, increase public awareness, and boost investment in renewables. Closing down of the coal industry in the Western Balkans would result in substantial job losses; combining social assistance and re-skilling programmes can create new opportunities for affected persons. For example, miners and workers at thermal power plants (TPPs) can be reskilled for employment in thermal retrofitting programmes in the building sector, as well as other relevant jobs in construction and manufacturing. In relation to renewable energies, lack of public awareness of their benefits currently prevents renewable self-consumption from reaching its full potential. Education programmes can play an important role in raising awareness among energy consumers and change their behaviour. Finally, equipping young people with solid scientific knowledge and understanding of environmental issues is key to grow their knowledge to build sustainable cities, start sustainable businesses, and push the innovation frontier for green technologies.

1.1.2. Three enablers: Governance, digitalisation and local communities

In the end, progress depends on implementation and reliability. Governments in the Western Balkan have recently produced an impressive quantity and quality of legal texts and strategies. Yet translation into practice often remains slow. Inefficient government structures and lack of capacity for service delivery were identified in the Initial Assessment of the MDR as major constraints. State structures tend to be overly complex, often involving numerous ministries and agencies without clear lines of accountability. This delays decisions and has implications for cost, time and resources. Frequent political changes and insufficient protection against undue influence are other sources of delay and impediments. At the same, time citizens placed the rule of law, good governance and effective policy making very high in their visions of a good future during the Vision and Challenges 2030 workshops2 undertaken as part the MDR initial assessment process. Reaching consensus regarding objectives and ensuring effective public delivery and implementation are core elements of good governance that can support the achievement of strategic priorities (OECD, 2021[1]).

Digitalisation can transform governments and improve public service delivery; its potential should be fully explored. Examples of early-adopting economies, such as Estonia, show that digitalisation can help re-engineer structures of the public administration for higher performance at lower cost. The Western Balkans economies have been making important progress in adopting digital technologies. Of the 193 nations listed on the UN EGDI5 (e-Government development) composite index, they rank in the mid-range: Serbia (58), Albania (59), North Macedonia (72) and Montenegro (75) (UN, 2020[5]). In 2019, North Macedonia and Serbia signed an agreement on mutual acceptance of electronic documents, a great example of digitalisation fostering regional integration (OECD, 2021[6]).

Local authorities need stronger capacities to tailor services to local needs. Across the Western Balkan region, local governments are key to the implementation and delivery of many government programmes and services (e.g. education, healthcare, social assistance, and water and waste services). Often, however, they do not fulfil their roles. Many municipalities with sizeable staff spend the bulk of their budgets on salaries. Benchmarking shows that services delivered are not in line with what is spent on delivery. Political patronage often plays an outsized role in hiring at the local level. In some economies, the incentives that govern the allocation of central funding to local governments lead to surplus hiring, instead of smart and efficient investment based on performance. While structures vary, all economies struggle in some way with delivery at the local level. Going forward, improving collection of population data is necessary to understanding the needs of people and local communities, and providing targeted services (OECD, 2021[1]).

1.2. Boosting education and competencies

Quality education ranked as a top priority in all economies during the Vision and Challenges 2030 workshops. While economic structures vary significantly, finding new sources of productivity growth and new engines for economic transformation is urgent for all. Good jobs are scarce and young people continue to emigrate. Boosting youth and workforce competencies can unlock new opportunities. The more unfavourable an economy’s current wage-to-productivity ratio, the more urgent this task becomes. Kosovo faces the biggest hurdles in this area, but the range of challenges is similar in all economies, and differences in wage-to-productivity ratios are small.

The Western Balkans economies have made great progress in education over the last decades. The introduction of competency-based curricula, participation in the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), development of new standards for teachers, and investments in vocational education and training (VET) have been some of the key reforms in the region.

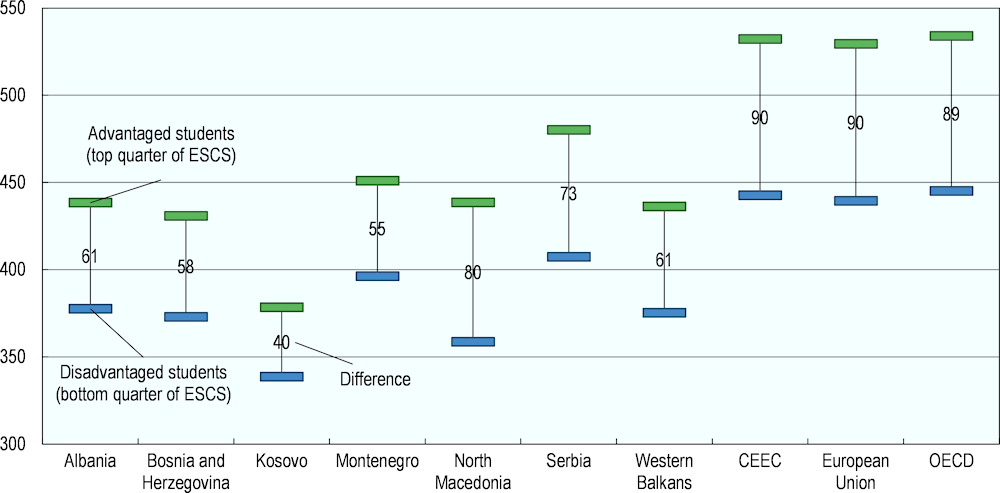

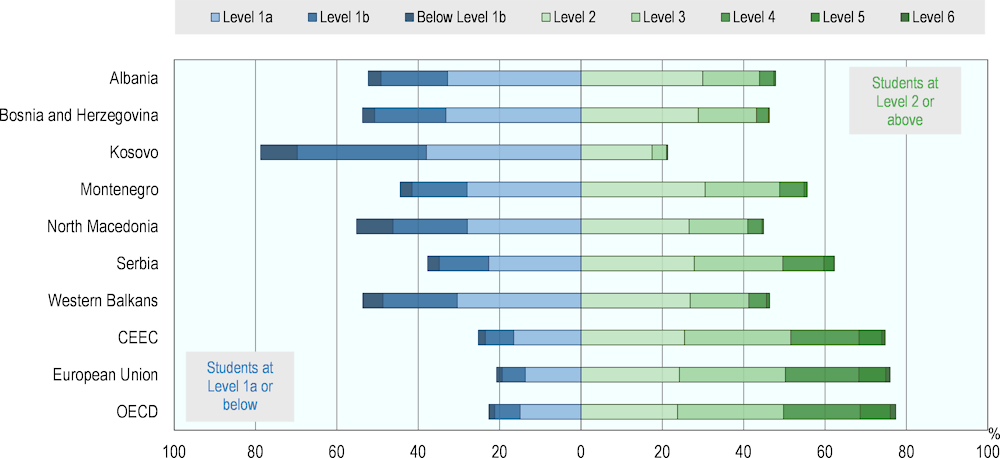

Despite that progress, there remains a wide scope for improving the outcomes of formal education. International education and international student assessments of the Western Balkan economies reveal gaps in student learning outcomes. The 2018 OECD PISA results show that less than half (46%) of students in these school systems scored above baseline proficiency in reading (PISA Level 2 and above) compared with averages of three-quarters for OECD countries (77%) and EU countries (76%) (Figure 1.3).

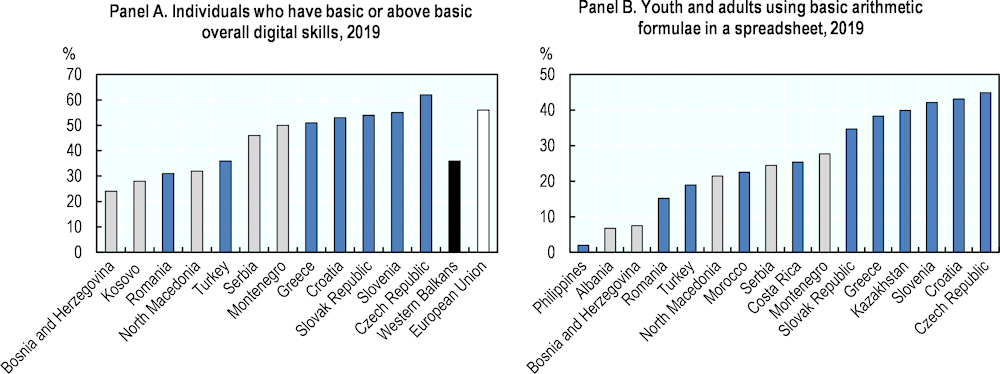

Beyond formal education, many adults lack the competencies demanded on labour markets. Many enterprises in the region report hiring difficulties due to skills shortages and find that the education system does not impart the skills needed (World Bank, 2021[7]). Apart from Serbia and Montenegro, the share of individuals with basic or above basic digital skills is relatively low in comparison to EU benchmark economies (Figure 1.4 – Panel A). The share of people who have used basic arithmetic formulae in a spreadsheet is very small in some economies, indicating a lack of key computer skills, which are important requirements for many employers (Figure 1.4 – Panel B).

Figure 1.3. Proficiency levels of students in reading is trailing behind benchmark economies

Source: OECD (2020[8]), Education in the Western Balkans: Findings from PISA, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/764847ff-en.

Figure 1.4. There is further scope to increase digital and technical computer skills in the Western Balkans

Source: Eurostat (2021[9]), Database, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database; UNESCO (2020[10]), UIS Statistics, http://data.uis.unesco.org/.

Boosting education and competencies requires a strong and modern education system at all levels as well as strategies for building competencies beyond formal education. Governments across the region should strengthen and modernise education systems at all levels through pedagogical and curriculum reform focusing on labour market competencies. In parallel, they should put a premium on equity and performance without jeopardising quality. Strategies for boosting competencies should combine and include: education with practical work-based training; promotion of investment focused on new competencies; proactive creation of partnerships between firms, academia and other stakeholders; and building digital skills among students and adults. The large Western Balkan diaspora should be considered a core asset in such strategies and used to create opportunities for transfer of skills.

1.2.1. Improving the quality and relevance of formal education

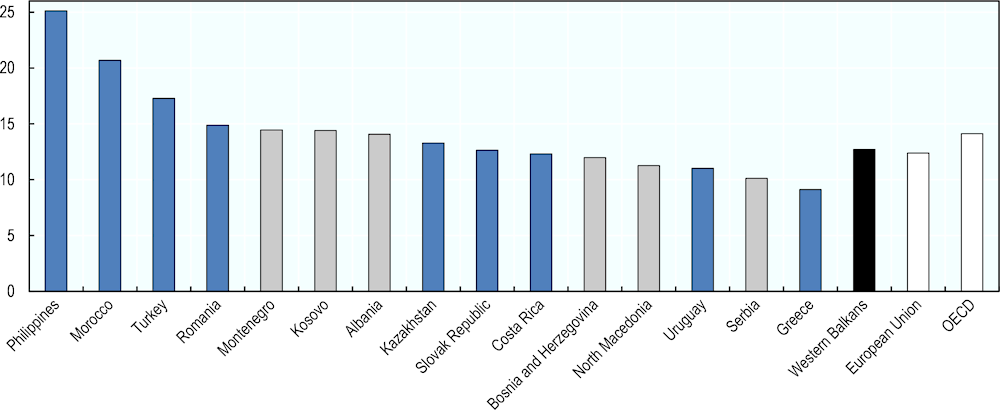

Investing in the quality of teaching is key to improving education outcomes. Despite a favourable pupil-teacher ratio overall (Figure 1.5), poor teacher selection criteria and lack of opportunities for professional development undermine teacher motivation, with negative effects on education outcomes. Improving teaching quality requires better implementation and use of standards to strengthen initial teacher education (ITE), as well as adequate support and incentives for continuous professional development (CPD) for teachers, including linking CPD to regular appraisals and career development.

Figure 1.5. Favourable pupil to teacher ratios are not reflected in education outcomes

Sources: Kosovo Agency of Statistics (2021[11]), Askdata (database), https://askdata.rks-gov.net/PXWeb/pxweb/en/askdata/?rxid=4ccfde40-c9b5-47f9-9ad1-2f5370488312; World Bank (2021[4]),, World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators.

To exploit the potential of VET, increase investment in infrastructure and technology, and ensure the education track is integrally linked with the private sector. A high quality VET system is critical for creating the job-ready skills and competencies that matter for economic development (Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation, 2009[12]). Despite high enrolment rates in VET (except in Albania), education outcomes in most of Western Balkan economies are rather poor. In the most recent PISA, results for reading show that VET students scored 382 points, significantly below those enrolled in general education (435). The largest gap was in Serbia (85 points) and the narrowest in Albania (25 points) (OECD, 2020[8]). Improving the quality and relevance of VET by equipping students with modern labour market skills requires equipment, technology and other relevant teaching materials. Adapting curricula to labour market needs, recruiting teachers with practical experience and providing students with work-based learning are also vital, and call for intensified collaboration with the private sector.

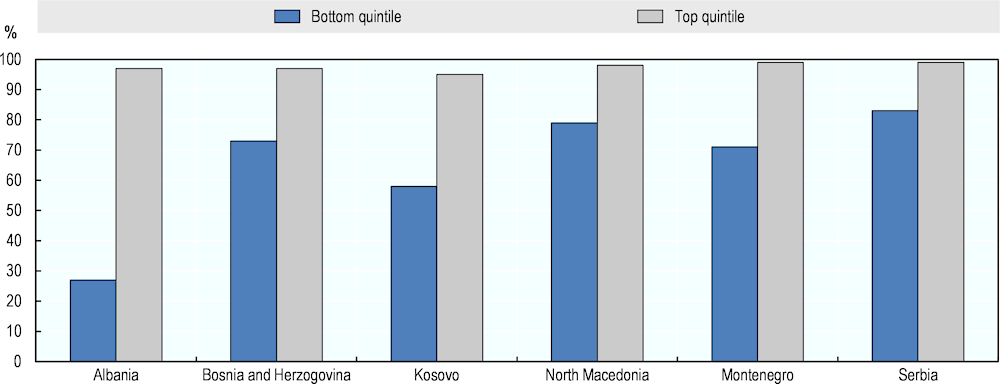

Digital technologies can boost transformation across economies in the Western Balkans, but unleashing their full potential requires access to relevant digital technologies, and to teachers who have the necessary skills to use such technologies and to train others. The COVID-19 pandemic revealed major challenges in relation to digital technologies. Both the abrupt transition to remote learning following school closures and the looming challenges of school reopening and learning recovery will affect disadvantaged pupils with poor access to relevant technologies the most (Figure 1.6). This “shock” also highlighted longstanding weaknesses in digital learning capacity, in terms of home and school digital infrastructure, and in the capacity of teachers to use digital resources effectively. Data from PISA show that, in 2018, Western Balkan schools attended by 15-years-olds had just over 0.25 computers per pupil compared with an OECD average of over 0.8 (OECD, 2020[8]).

Figure 1.6. In most of the Western Balkan economies, students’ background influences their access to digital technology

Source: World Bank (2020[13]), The Economic and Social Impact of COVID-19: Education, http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/590751590682058272/pdf/The-Economic-and-Social-Impact-of-COVID-19-Education.pdf.

To make the most of recently adopted competency-based curricula across the region, strong teaching skills and learning standards with clear outcomes are needed. Curricula are powerful levers for strengthening student performance and well-being, and for preparing students for their future jobs (OECD, 2020[14]). While most of the Western Balkan economies have developed core competency-based curricula, the common challenge is that teachers and schools lack the competencies to implement the curricula and adapt them to their needs. In addition, there are no guidelines to describe students’ learning progression in a cycle. Based on external school evaluation results, the use of assessment to inform learning and adapt teaching to student needs is weak in almost half of basic education schools and two-thirds of upper secondary schools.

While Western Balkans economies are on par with OECD countries as regards equity in education outcomes, closing the differences between advantaged and disadvantaged students should remain a priority. Equity in education means that personal or social circumstances – such as gender, ethnic origin or family background – are not obstacles to achieving educational potential (fairness) and that all individuals achieve at least a basic minimum level of skills (inclusion). In the Western Balkans, education access and attainment need to be improved especially for the Roma and other minorities, the poor, rural children and children with special needs. Students from socio-economically disadvantaged backgrounds tend to perform worse than those from advantaged backgrounds (Figure 1.7).

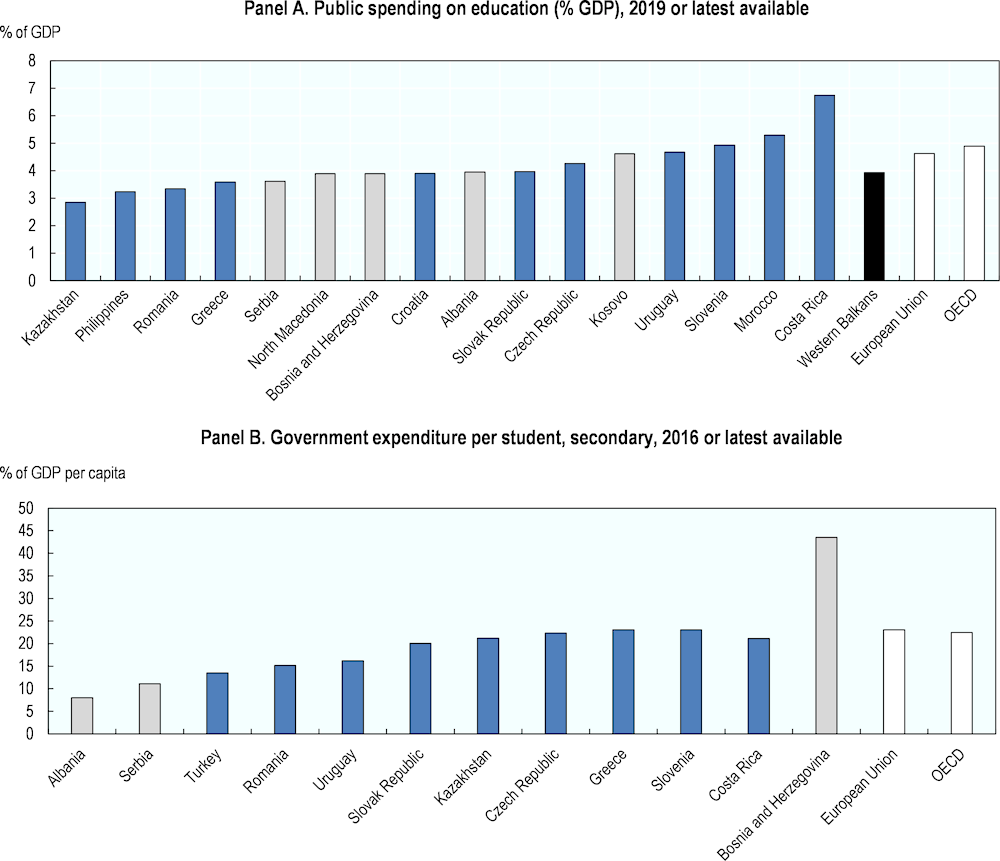

Figure 1.7. Reading performance is influenced by students’ background, although less than in the EU and OECD

Increasing the financing of education and improving the effectiveness of education spending are important levers for improving learning outcomes. In the Western Balkans, insufficient funding for education affects learning outcomes at all levels (Figure 1.8 – Panel A), particularly in ECEC and secondary education (including VET) (Figure 1.8 – Panel B). Even in economies where public spending on education as a share of gross domestic product (GDP) is on par with OECD countries, high staff costs (related to an excess number of teaching and non-teaching staff) crowd out spending on infrastructure, teaching materials, technology and equipment. Based on data available, spending on secondary education is comparatively very high in Bosnia and Herzegovina but low in Albania and Serbia (Figure 1.8 – Panel B). Low spending in Serbia strongly affects VET, which tends to attract a high share of students and is much more resource-intensive than general education. Despite nascent efforts to introduce a per-capita financing formula in some economies, the financing of schools remains based on inputs such as the number of classes and teachers.

Figure 1.8. The Western Balkan economies should increase and rebalance expenditures in education

Note: Panel A - data for Morocco is from 2009, data for North Macedonia is from 2013, date for Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia are for 2017, data for Romania, Greece, Slovak Republic, Czech Republic, Slovenia, EU and OECD averages are for 2018, data for Albania, Kazakhstan, Philippines, Serbia and Uruguay are for 2019. Panel B - Data for Serbia is for 2015, data for Turkey, Romania, Slovak Republic, Kazakhstan, Czech Republic, Greece, Slovenia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, EU and OECD averages are for 2016, data for Albania and Uruguay are for 2017.

Source: World Bank (2021[4]), World Development Indicators, https://databank.worldbank.org/reports.aspx?source=world-development-indicators; Agency for Statistics of Bosnia and Herzegovina (2021[15]), Agency for Statistics of Bosnia and Herzegovina website, www.bhas.ba/?lang=en; Kosovo Agency of Statistics (2021[11]), Askdata (database), https://askdata.rks-gov.net/PXWeb/pxweb/en/askdata/?rxid=4ccfde40-c9b5-47f9-9ad1-2f5370488312; MAKStat (2021[16]), MAKStat (database), http://makstat.stat.gov.mk/PXWeb/pxweb/en/MakStat/MakStat__NadvoresnaTrgovija__KumulativniPod/?rxid=e70e8868-e6a5-4557-87cc-fc8b565e5da3.

Strengthening the governance of education can improve the implementation and evaluation of education policies and contribute forming strong partnerships, especially with the private sector. Common education governance challenges in the Western Balkan economies include weak co-ordination (especially between central and local governments), inadequate data collection and limited use of data to monitor and evaluate education policy. In practice, systematic and effective engagement with the private sector and other relevant stakeholders (academia, civil society and other actors) is yet to be achieved.

Regional economies should invest more in access to, and the quality of ECEC. Research shows that ECEC has significant benefits for children’s development, learning and well-being, and can improve their cognitive abilities and socio-emotional development. Children who start their education early are more likely to have good outcomes when they are older; this is particularly important for children from disadvantaged socio-economic backgrounds, with more limited opportunities for learning at home. Access to ECEC in the Western Balkans is very limited, especially for the poor and those living in rural areas. The biggest gaps in ECEC enrolment exist for children aged 0-3 years old.

1.2.2. Boosting competencies beyond formal education

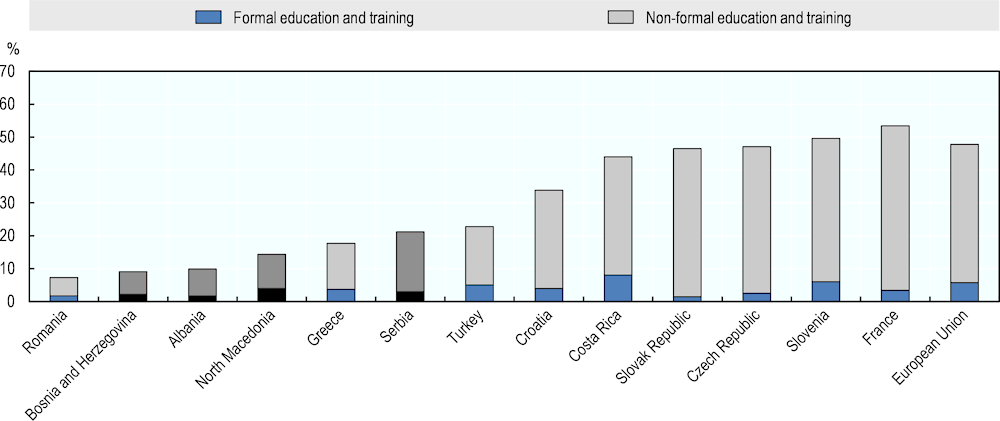

To become dynamic economies, the Western Balkans need to put a high premium on adult learning – both for upskilling and reskilling. Automation in various sectors is expected to change skill needs within existing jobs, while making certain jobs obsolete. In parallel, new technologies and changes in the organisation of work are creating new jobs with very different skill needs. Adult education is critical to adequately facing these challenges: high quality adult learning systems can help people develop and maintain relevant skills over their careers (OECD, 2019[17]). At present, only a relatively small share of adults in the Western Balkan economies participate in any kind of formal or non-formal education and training activities (Figure 1.9).

Figure 1.9. Adult participation in education and training is very low

Source: Eurostat (2020[18]), Database - Skills-related statistics, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/skills/data/database.

To ensure the highest possible spillovers of competencies and knowledge – both for local people and enterprises – the Western Balkans economies should create linkages with existing foreign investors and attract strategic investment. Foreign direct investment (FDI) can boost competencies and increase the skills of both employees as well as local enterprises that supply material to foreign companies. Foreign companies can also provide valuable inputs for curricula development and modernising the education system. With these considerations in mind, investment promotion policies should target investments with high potential to trigger competency-related spillovers. Aftercare services for investors can also support the development of linkages with local business. Economies in the region have attracted investors in recent years; while more policy efforts are required to strengthen linkages with domestic economies, North Macedonia and Serbia show great promising examples (Box 2.3 of Chapter 2).

Economies in the region should tap into their large and well-educated diaspora, seeking to stimulate financial capital and knowledge spillovers. Citizens of the Western Balkans who currently live in OECD countries are highly skilled (Figure 1.10); they also tend to maintain familial connections to their places of origin, visible through the large volumes of remittances flowing into the region every year (World Bank, 2021[4]). To date, the region has not sufficiently tapped into these emigrants’ knowledge and competencies which are not available domestically. The Albanian Diaspora Business Chamber, an independent non-profit organisation that supports investors from the diaspora willing to establish or expand their businesses in Albania, is a recent example of such efforts. In addition, Albania’s National Strategy for Diaspora 2021-2025 (adopted in July 2020 by the Council of Ministers), aims to mobilise professionals abroad and to attract innovative investments from the diaspora (OECD, 2021[1]).3

Figure 1.10. A large share of Western Balkans people living in OECD countries have important skills

Source: OECD (2016[19]), Database on Immigrants in OECD and non-OECD Countries: DIOC (database), www.oecd.org/els/mig/dioc.htm.

1.3. Fostering social cohesion

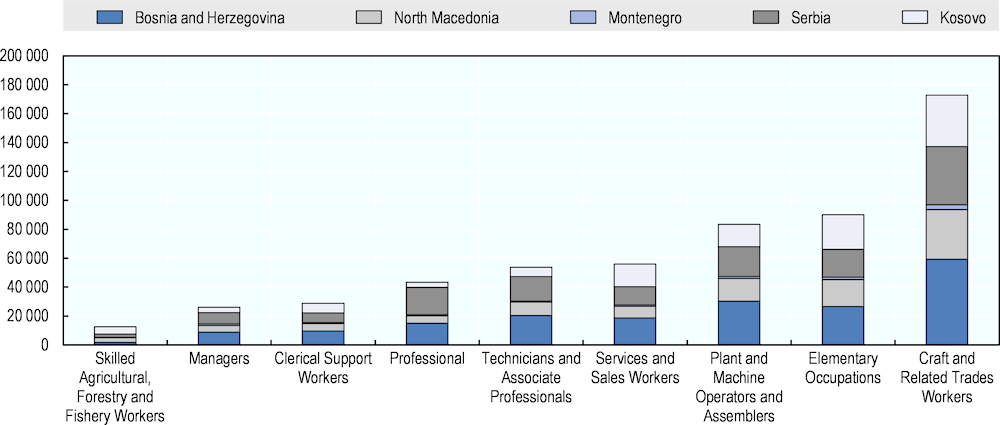

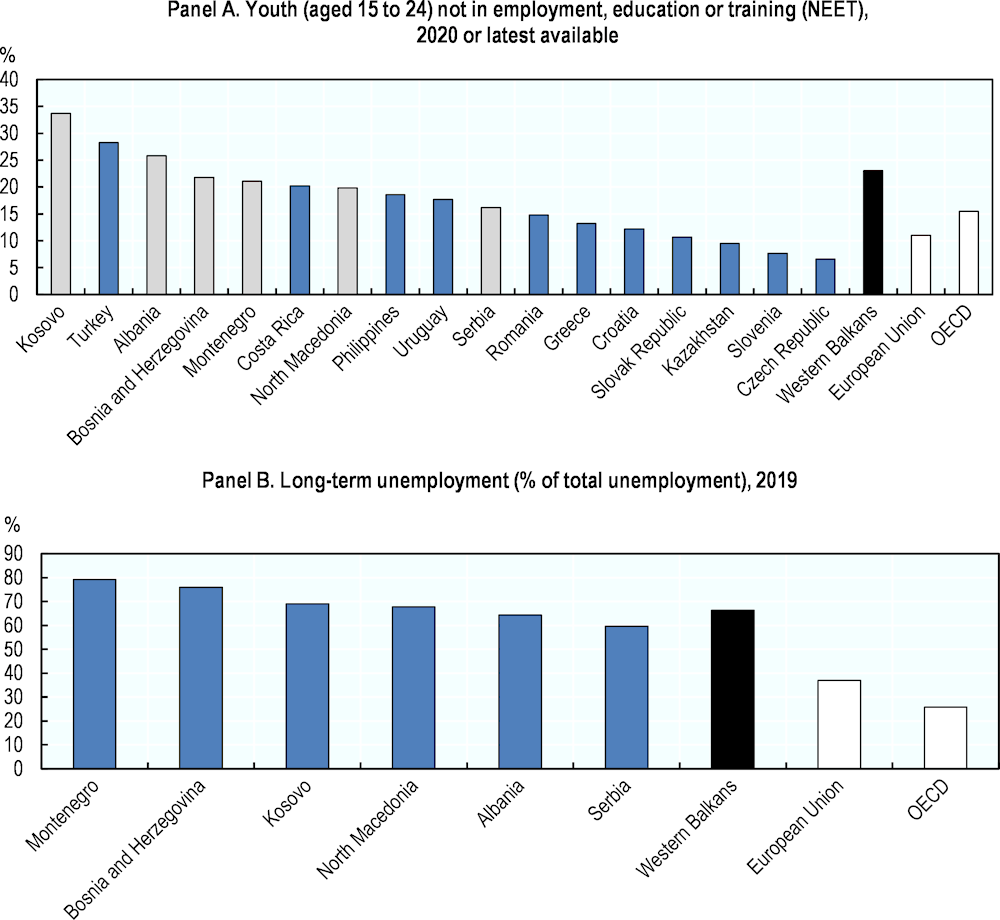

Across the Western Balkans, underperforming labour markets leave many people without attractive employment opportunities and strain the ability of citizens to support each other, thus hampering social cohesion. Labour markets in the region are characterised by a lack of formal jobs, especially for young persons, and high long-term unemployment rates (Figure 1.11). In turn, many people find themselves without adequate income and risk losing valuable skills and exiting labour markets, which puts great strain on the social protection system. The lack of equal opportunities in the labour market for some groups, including women and Roma, exacerbates the problem and deprives the regional economies of human capital. To earn income, many people resort to informal activities.

Figure 1.11. Many young and long-term unemployed have poor labour market prospects

Note: Panel A. data for Albania and Uruguay are for 2019, data for Kazakhstan is for 2016.

Source: ILO (2021[20]), ILOStat (database), https://ilostat.ilo.org/data/; Eurostat (2021[9]), Data Explorer (database), https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database; OECD (2021[21]), OECD Statistics (database), https://stats.oecd.org/; World Bank/WIIW (2021[22]), SEE Jobs Gateway (database), https://data.wiiw.ac.at/seejobsgateway-q.html; World Bank (2021[4]), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators.

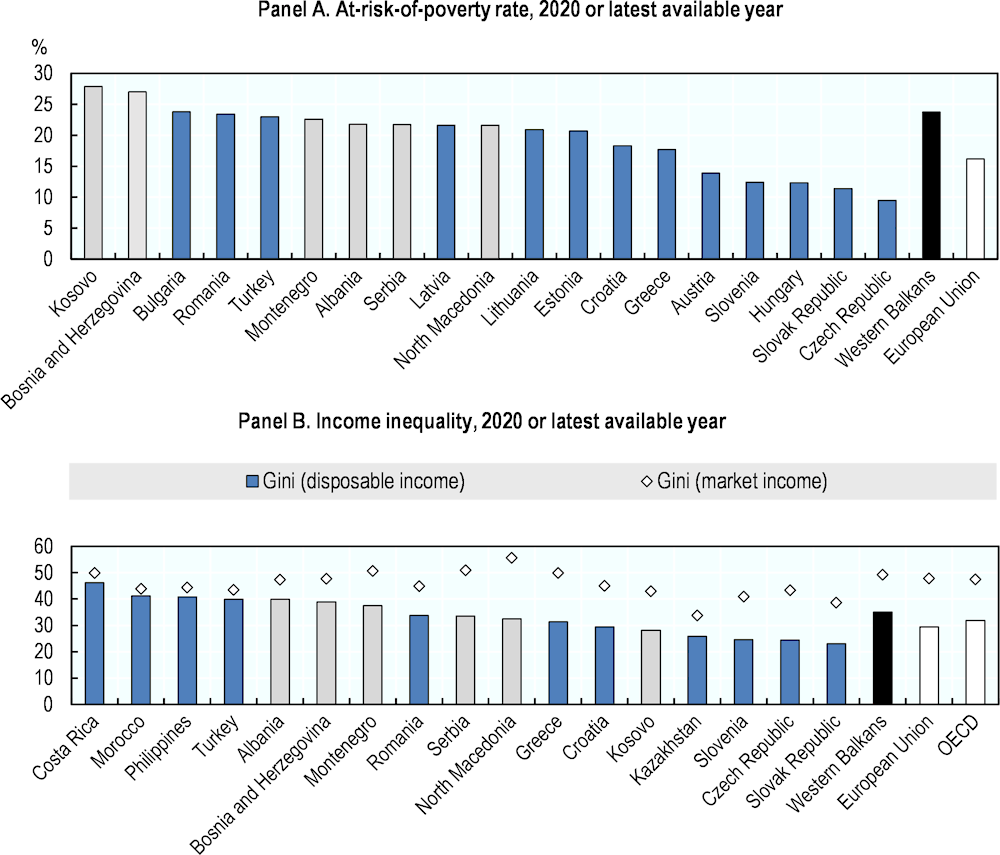

Social protection systems in the region do not adequately reduce poverty, limit inequalities or address discrimination. In 2020 almost one-quarter of the Western Balkan population lived in poverty, which particularly affected people living in rural areas (Figure 1.12 – Panel A). High levels of post-distribution income inequality – at about 35.1 on the Gini index – suggest that social protection policies do not adequately address it (Figure 1.12 – Panel B). In turn, high territorial inequalities demand more effective social protection policies, as do the adverse well-being outcomes of certain groups, including Roma or lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) persons.

Figure 1.12. Many people continue to live in poverty and inequalities are relatively high

Note: The at-risk-of-poverty rate is the share of persons with an equalised income below 60% of the national median income after social transfers. Panel A - The latest available year is 2015 for Bosnia and Herzegovina, and 2018 for Kosovo. Panel B - The latest available year is 2014 for Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro and Morocco, 2015 for the Philippines, 2016 for North Macedonia and Slovak Republic, 2017 for Croatia, Czech Republic, Greece, Kosovo, Romania, Serbia and Slovenia, and 2018 for Albania, Costa Rica, Kazakhstan and Turkey.

Source: Eurostat (2021[9]), Data Explorer (database), https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database; ESPN (2019[23]), In-work poverty in Bosnia and Herzegovina, https://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=21121&langId=en; Solt (2019[24]), The Standardized World Income Inequality Database, Versions 8-9 (dataset), https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/LM4OWF.

Addressing the issues that hamper social cohesion in the Western Balkans calls for strong labour market policies that help people participate in the labour market on an equal footing, as well as social protection schemes that cushion periods of hardship and provide people with new opportunities. To achieve a socially cohesive society, it is important to offer its members the opportunity to participate, to create a sense of belonging and promote trust, and to fight against exclusion and marginalisation (OECD, 2011[25]). Employment opportunities provide people with income and prospects for personal development while also reducing financial pressures on the social protection system, which in turn provides room to improve its quality. As the region’s populations grow older, solving the social protection challenge becomes more urgent. Gaps in social security provision must be closed, coverage enhanced and adequacy improved. Importantly, support must be targeted to first reach those who need it most.

1.3.1. Supporting people to find opportunities in the labour market in the Western Balkans

Strengthening the coverage and effectiveness of active labour market policies (ALMPs) can play a major role in integrating the unemployed into the labour market, including the long-term unemployed and persons with limited work experience, especially among the young. Participation of the registered unemployed in ALMPs varies across the Western Balkan economies, ranging from 5.3% in Serbia (in 2018) to 9.3% in Kosovo (in 2016), which is very low in comparison to 2016 figures for the benchmark economies of Croatia (22.1%), Slovak Republic (26.8%) and Hungary (71.4%) (Table 1.2) (European Commission, 2021[26]). Low staffing in the public employment services in the region means the administrative workload of each counsellor limits the effectiveness of ALMPs, especially in connecting people with jobs and providing them with opportunities to acquire new and additional skills.

Table 1.2. Participation in ALMP measures varies among economies but is low overall

Share of participation in different ALMP measures per number of unemployed registered with employment services in 2018 (or latest available)

|

Albania |

Bosnia and Herzegovina |

Kosovo |

North Macedonia |

Serbia |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Total |

Youth |

Total |

Youth |

Total |

Youth |

Total |

Youth |

Total |

Youth |

|

|

Registered job seekers |

64 781 |

11 960 |

435 266 |

56 681 |

101 773 |

32 987 |

94 721 |

20 151 |

552 513 |

54 226 |

|

ALMP participants (% of registered unemployed) |

7.4 |

30.9 |

7.6 |

13.5 |

8.5 |

22.9 |

8.1 |

11.6 |

5.3 |

9.7 |

Source: CPESSEC (2019[27]), Statistical Bulletin No. 9, https://www.docdroid.net/qvBC3jr/statisticki-bilten-br-9-cpessec-finalno-converted-pdf; RCC (2021[28]) Study on Youth Employment in the Western Balkans, https://www.rcc.int/download/docs/Study-on-Youth-Employment-in-the%20Western-Balkans-08072021.pdf/7464a4c82ee558440dfbea2e23028483.pdf Jahja Lubishtani (2018[29]), The Effectiveness of Active Labour Market Policies in Reducing Unemployment in Transition Economies, https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/226765796.pdf; Government of Albania (2020[30]), Employment, Training, and Equal Opportunities, https://rm.coe.int/rap-cha-alb-11-2020/16809cd971.

Providing more opportunities for people from vulnerable groups, including Roma and people with disabilities, to participate in the labour market is important to unleash their potential and improve their social mobility. The Roma, who make up about 5% of the regional population, face particularly challenging labour market situations: lower educational attainment means they face significant barriers to employment (Robayo-Abril and Millan, 2019[31]). People with disabilities also face barriers to education and employment, in part due to stereotypes and other forms of marginalisation. Providing vulnerable persons with better access to education and reducing discrimination are priorities to improve their integration through employment.

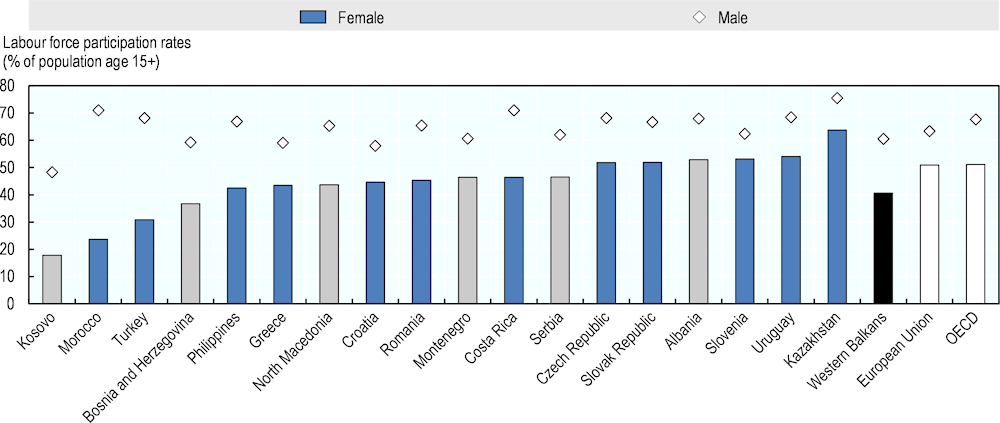

Supporting women’s integration into the labour market – including by encouraging their entrepreneurship – can allow Western Balkan economies to leverage their human capital while fostering social cohesion. Despite variation across Western Balkan economies, the regional gender gap in labour force participation (about 20 percentage points) is significantly higher than OECD and EU averages (16.5 and 12.4 percentage points, respectively) (Figure 1.13). Across the region, women face multiple barriers to formal employment, including the lack of available childcare, institutional barriers and social norms. Low ECEC enrolment, especially in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo and North Macedonia, means women must prioritise childcare over employment. The lack of flexible work arrangements and social norms, such as gender stereotypes and patriarchal culture, also constrain women’s participation in the labour market.

Figure 1.13. Creating more labour market opportunities for women

Note: Panel A. Data for Morocco refer to 2016, data for Albania refer to 2019.

Source: World Bank (2021[4]), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators.

1.3.2. Social protection systems in the Western Balkans could reduce poverty, tackle inequalities and address discrimination more effectively

To encourage people to participate in formal employment, economies in the region should reduce high social security contributions, especially for low wage earners, address the adequacy of benefits, and improve the effectiveness and attractiveness of social security systems. Current labour market challenges create a situation in which many people, especially the young, do not contribute to unemployment insurance long enough to qualify for unemployment benefits or, for older individuals, have lost their unemployment benefit entitlements due to long-term unemployment. The high overall level of labour taxation, especially in Serbia, Montenegro, and Bosnia and Herzegovina (and to some degree in North Macedonia), together with non-existent or very modest progressivity of personal income tax, reduces take-home pay for low-wage earners and those working shorter hours, creating disincentives for formal labour market participation.

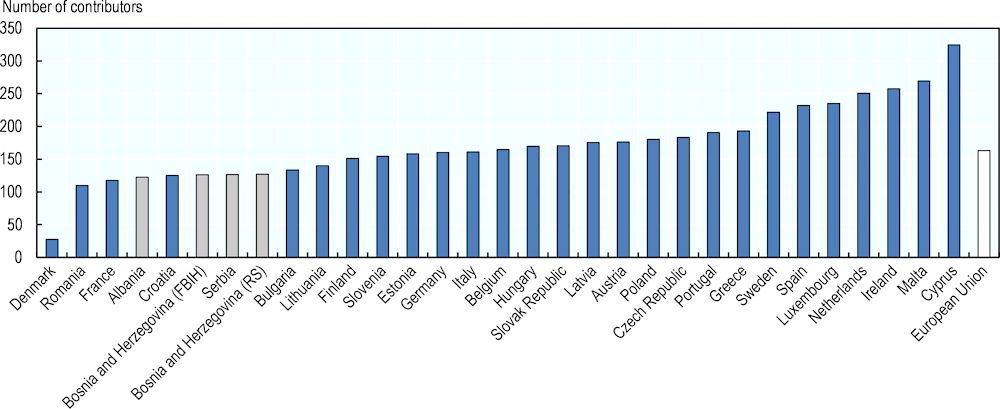

In view of low social security contribution rates in the working age population and rapid population ageing over the next decades, addressing coverage can improve financing of old-age pensions, an integral part of any social security system, and a tool to foster social cohesion. The relatively low number of contributors has been creating significant pressure on pension systems across the region (Figure 1.14). All economies in the region (with the exception of Kosovo) have undertaken major reforms of their pension systems in recent years. However, in light of low labour market participation and population ageing, more effort is needed to ensure both adequate protection for people and the long-term sustainability of social protection systems.

Figure 1.14. A relatively low and declining number of contributors creates pressure on pension systems in the region

Note: Data for Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Serbia is for 2018.

Source: European Commission (2021[32]), The 2021 Ageing Report, https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/economy-finance/ip148_en.pdf; World Bank (2020[33]), Albania: Pension Policy Challenges in 2020, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/110911593570542693/Albania-Pension-Policy-Challenges-in-2020.docx; World Bank (2020[34]), Bosnia and Herzegovina: Pension Policy Challenges in 2020, https://documents.worldbank.org/pt/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/292981593571282850/bosnia-and-herzegovina-pension-policy-challenges-in-2020; World Bank (2020[35]), Serbia: Pension Policy Challenges in 2020, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/598501593564636264/pdf/Serbia-Pension-Policy-Challenges-in-2020.pdf.

Despite their wide variety, for all social assistance schemes in the Western Balkans there is a common need to increase both the coverage and adequacy of benefits. In general, spending on means-tested benefits makes up a very small share of overall social protection spending in these economies. This reflects low benefit levels and, in some cases, poor targeting. Ultimately, means-tested benefits do not play a sufficient role in poverty alleviation. Additionally, status groups such veterans and their families receive more generous benefits in the form of pensions, regardless of their needs and labour market participation. Regional economies should address the low level of coverage through more effective targeting and by removing administrative barriers to obtaining assistance, while also reassessing the adequacy of social assistance benefits.

Establishing community-integrated social services is one of the key policy priorities identified by peer-learning workshop participants. Community-integrated social services encompass a range of approaches and methods for achieving greater co-ordination and effectiveness among different services, such as elderly care, healthcare, education and others – with the objective of improving outcomes for services users.4 Peer-learning participants stressed community-integrated services as a key lever to strengthen social protection, deliver social care services and reduce long-term dependency on social welfare through better labour market integration. At present, limited or inexistent social services in some economies and low capacities in local governments hamper prospects of creating community-integrated social services. A related challenge is that, across the region, population information is generally based on often outdated census data and civil registration, which might not account for migration flows within economies and abroad. As such, current systems of resource redistribution may underestimate local service users and exacerbate (rather than reduce) territorial inequalities.

1.4. Ensuring a green recovery

A green recovery in the Western Balkans requires energy sector reforms to make the region healthier and more attractive to live in, to return to, and to invest in. A cleaner environment, in particular, less air pollution, especially in the major urban centres, is a top desire of residents of the Western Balkans. A rapid phase-out of coal would dramatically reduce air pollution. At the same time, successful energy sector reforms dismantling monolithic structures in the state-owned utilities would enhance their productivity, and open up space for new companies to inject dynamism in the sector. Cleaner air and new opportunities for employment would follow and make the region more attractive for young people.

In the longer run, a greener trajectory for the region can create opportunities through broad transformation. Beyond the energy sector itself, more resource-efficient modes of operation and entirely new manufacturing and service activities will have to follow as next steps. This longer-term vision of a greener future requires modernisation across many sectors and links to the education and skills framework, leading to innovation and next generation business and employment opportunities.

Economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic is an opportunity to “build back better”, a strategy adopted by many governments around the world, with a focus on leveraging post-pandemic growth in energy demand and investment to drive the low-carbon transition. While the pandemic has spurred aggressive action, governments need to recognise that global environmental emergencies – such as climate change and biodiversity loss – could cause far larger social and economic damage. In this regard, “building back better” means governments should design economic recovery packages that trigger investments and societal changes to both reduce the likelihood of future shocks, and improve resilience when they do occur, whether from disease or environmental degradation. At the heart of this approach is the transition to more inclusive, more resilient societies with net-zero greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and much-reduced impacts on nature (OECD, 2020[36]). A green recovery in the Western Balkans should leverage opportunities to modernise and upgrade the region’s energy systems, which would dramatically reduce GHG emissions.

A green recovery will take place amidst the process to implement the policies of the Energy Community, of which the Western Balkan countries are part, and more broadly the EU acquis5 for the energy sector. Meanwhile, the European Union, which represents 87% of the Energy Community’s population, has raised its ambitions for the energy transition by announcing its Green Deal at the end of 2019, and in April 2021 approved legislation to reduce carbon emissions by at least 55% by 2030, compared with 1990 levels.

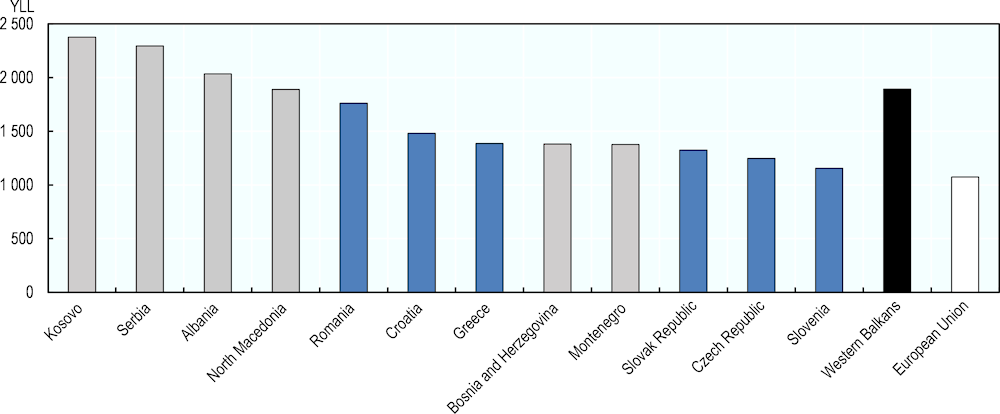

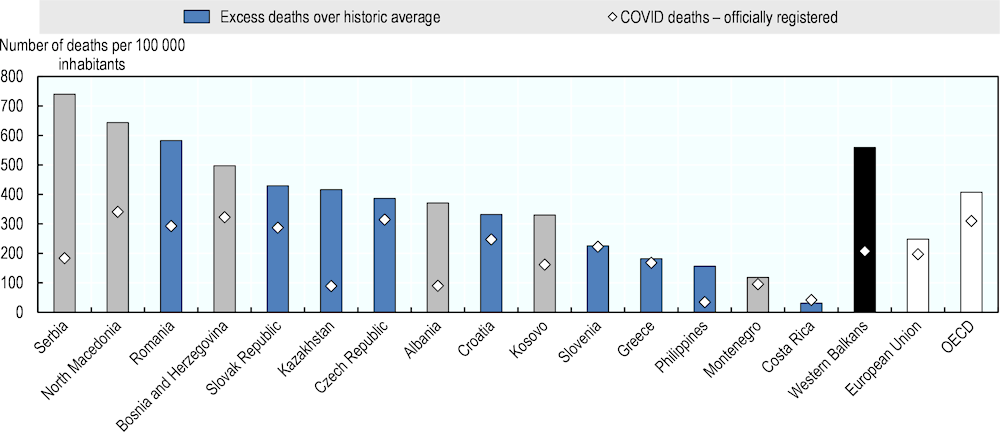

Air pollution is one of the most pressing strains to quality of life in the Western Balkans. The rate of premature deaths associated with exposure to fine particle (particulate matter or PM) pollution is much higher than in neighbouring countries (Figure 1.15). In the three-year period leading up to 2020, air pollution from coal plants in the region was responsible for 19 000 deaths (CEE Bankwatch Network, 2021[37]) – of which nearly 12 000 resulted from breaches of legally binding pollution limits. Such breaches also generated healthcare costs between EUR 6.0 billion and 12.1 billion in 2020 alone.

Figure 1.15. Air pollution in Western Balkan economies has important health impacts

Source: European Environment Agency (2020[38]), Air quality in Europe: 2020 report. https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/air-quality-in-europe-2020-report.

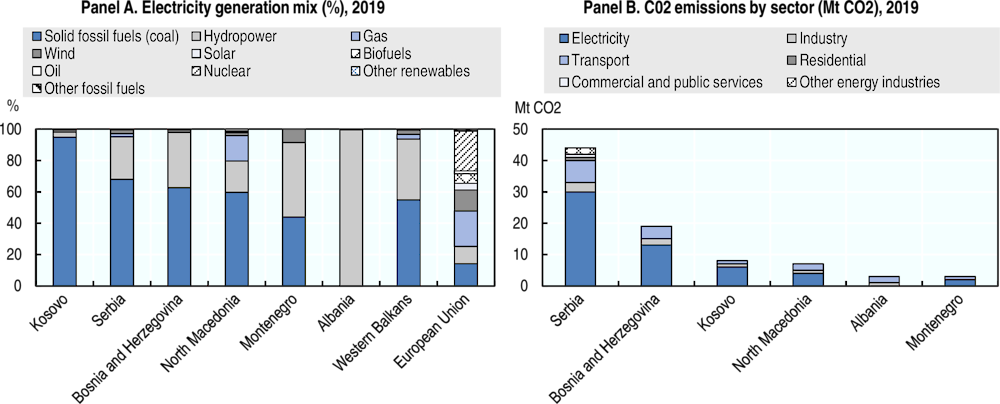

Heavy reliance on burning coal, along with outdated technology for power generation and residential heating, are the main drivers of high pollution in the region. Burning of coal and wood in homes, for cooking and heating, generates high levels of PM 2.5 emissions (World Bank, 2020[39]). Power generation from coal, the main source of electricity generation in the region except Albania, is the second-largest source of PM 2.5 emissions within Western Balkan economies, and by far the leading source of transboundary pollution.

High reliance on coal for energy production, combined with outdated power plants, result in low energy efficiency and significant CO2 emissions (Figure 1.16). In relation to economic output in Western Balkan economies, both energy use and CO2 emissions remain high. While energy and carbon intensities per unit of GDP have been reduced since 2010, they remain well above most regional peers and averages of EU and OECD countries. In contrast, CO2 emissions per capita are below EU and OECD averages, reflecting lower levels of industrial activity per capita. Prospect for improvement are low: despite an aging fleet of thermal power plants (TPPs), few are scheduled for decommissioning and new plants are planned. Under such conditions, air pollution will continue to worsen.

Figure 1.16. Coal-fuelled electricity generation drives CO2 emissions in the Western Balkans

Source: Panel A: Eurostat (2021[9]), Eurostat (database), https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/. Panel B: IEA (2021[40]), Data and statistics, https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/.

Many of the region’s coal power plants emit harmful substances in massively higher volumes than legally allowed. In 2020, the 18 coal-fired power stations in Serbia, Kosovo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, North Macedonia and Montenegro produced 2.5 times as much harmful sulphur dioxide (SO2) emissions as all of the 221 coal stations in the EU combined. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, North Macedonia and Serbia, levels of SO2 pollution are six to seven times the legal limit to which these economies committed to under the Energy Community (CEE Bankwatch Network, 2021[37]).

Pollution and emissions intensity will continue to pose challenges to the region’s EU integration process. In recent years, the Energy Community Secretariat had to bring several dispute settlement cases against Western Balkan economies reflecting disregard of pollution limits in National Emission Reduction Plans (NERPs). Going forward, rapid progress within the EU on carbon pricing and a possible carbon border adjustment tax will likely have significant effects on electricity and other exports from the Western Balkans to the EU (Energy Community Secretariat, 2021[41]).

Transmission and distribution (T&D) losses add to the challenge of low energy efficiency. In 2019, technical losses linked to aging grids in Western Balkan economies amounted to almost 29% of primary energy consumption compared with 23% in the European Union. In 2014, average T&D losses across the region were as high as 16.6% of total electricity output, against an EU average of 6.2% and an OECD average of 6.3% (World Bank, 2021[4]).

On the demand side, high energy intensity reflects low levels of energy efficiency, particularly in residential and commercial buildings. Buildings in Western Balkan economies are poorly insulated, and space heating is often based on outdated and polluting heating devices. A large share of buildings are heated with inefficient stoves and boilers that use wood, lignite, and coal (World Bank, 2020[13]; Eurostat, 2021[9]).

Below-cost electricity prices, subsidies and inefficient state-owned enterprises (SOEs) dominating markets combine into an environment that is difficult to reform. Electricity prices charged to households in the Western Balkans are often lower than production costs, generating significant deficits of between 1% and 6% of GDP. Despite artificially low prices, the cost of electricity for households as a share of their income is relatively high, making price increases politically unpalatable. To compensate state-owned producers for low prices, governments subsidise these enterprises in a variety of ways. Except for Albania, most of this support subsidises coal. Subsidies and artificially low electricity prices have locked in public resources and continue to prevent fair competition for alternative electricity. Although possibly intended to keep electricity affordable for the less well-off, subsidies disproportionally benefit wealthier groups. With ageing infrastructure and commitments made towards competition and better regulation, the pressure to reform subsidies and SOEs will increase.

Significant challenges remain with implementation, capacity and political interference in energy markets. Overall, progress on transposing legal and regulatory frameworks contrasts with low levels of implementation and enforcement, as well as the limited capacity of Western Balkans institutions to manage the transition. Western Balkan governments have frequently adopted energy and environmental legislation that later is only partially enforced. Political interference, particularly in SOE governance, plays an important role in the slow pace of reform. Even in economies in which the legal framework governing the activities of the energy regulator is in line with the acquis, the regulator may lack de facto independence or adequate authority.

1.4.1. Priorities for the transition towards low-carbon energy

Western Balkan economies have already made important commitments to climate neutrality but often fall short on implementing plans and achieving objectives. Through the 2020 Sofia Declaration, Western Balkan economies committed to concrete actions in support of the EU 2050 climate-neutrality target. However, GHG emissions reduction targets under the Paris Agreement, established in Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), generally lack sufficient ambition to achieve this goal. Existing legislation on energy and climate is frequently not enforced and implementation deadlines are not respected.

Peer-learning participants selected finalising credible National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs) as the top priority for a green recovery in the region. NECPs are part of the Clean Energy for All Europeans package adopted in 2019. Western Balkan economies are at different stages of the process of developing NECPs, with Albania and North Macedonia being the most advanced (Table 1.3).

To fully play their role, NECPs must set out a convincing, credible vision that addresses key challenges. In the case of the Western Balkan region, NECPs must set out alternatives that allow for the decommissioning of coal, reduce subsidy regimes and prioritise energy efficiency investments. In parallel, they will have to set the conditions for renewables to play a much larger role in the energy mix, which imposes infrastructure needs. Enhancing the flexibility of electricity systems is of paramount importance, for example by adding easy-to-fire-up plants operating on natural gas and promoting more regionally integrated markets. All of this will likely imply higher energy and electricity prices generally, as well as job losses in coal-dependent industries. Such impacts will require economic and social policy responses. Last but certainly not least, investors must be able to trust in the direction of travel and the rules to be applied.

A credible vision must:

recognise that a green recovery requires adequate balance of intermittent renewables and baseload capacity in the Western Balkans. The question of how to replace coal-fired baseload in the Western Balkans remains unresolved. A credible vision would further need to recognise that large upfront capital investments are needed to either convert or replace existing coal plants with cleaner alternatives.

strike a balance between regional integration and energy security. Until cleaner options are available for implementing a minimum level of low-carbon domestic energy production, coal fired plants are likely to remain in the norm to ensure energy security.

take a holistic approach of the role of energy sector within the fiscal structure of each economy, and clearly communicate this approach to citizens. Across the Western Balkans, current energy subsidy regimes carry enormous fiscal costs. This significantly reduces the ability of governments to provide other services for citizens. In undertaking subsidy reform, they will need to convince citizens that more efficient, means-tested ways of reducing energy costs will enhance provision of other services.

bring clarity and cohesiveness to the body of existing laws, plans and strategies. All Western Balkan economies have either already adopted or drafted a low-carbon development strategy. However, these often remain at odds with other frameworks, such as energy strategies that extend use of coal rather than phasing it out, as in the case of Serbia and Kosovo. Most national energy efficiency action plans (NEEAPs) and renewables development strategies need to be updated or replaced (Table 14.6 of Chapter 14).

Table 1.3. Western Balkan economies’ progress varies in preparing NECPs

Progress in preparation and adoption of NECPs

|

Legal basis adopted |

Working group operational |

Modelling capacity exists |

Policy section drafted |

Analytical section drafted |

Submitted to the Secretariat for peer review |

Final version submitted to the Secretariat |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Albania |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

|

Bosnia and Herzegovina |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

|

Kosovo |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

|

Montenegro |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

|

North Macedonia |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

|

Serbia |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

Note: Green = in place; Orange = in progress; Red = limited progress.

Source: Energy Community Secretariat (2021[42]), WB6 Energy Transition Tracker, https://www.energy-community.org/regionalinitiatives/WB6/Tracker.html; Energy Community Secretariat (2021[41]), Annual Implementation Report, https://www.energy-community.org/implementation/IR2021.html.

To be credible, NECPs need to reflect a broad green social consensus and ensure that institutional capacity to deliver on commitments is in place. Western Balkan governments have committed to adopt and implement relevant EU energy and climate legislation, including energy efficiency, renewable energy and climate targets. However, in committing to EU legislation, regional and local consultations have played only a limited role. A credible vision should create buy-in from governments, parliaments, citizens, the private sector, and civil society, and motivate climate action. Such a vision should be based on a bottom up approach and start with commitments at the city and municipality levels. The low level of public awareness regarding the advantages of renewables and energy efficiency must be addressed through education, the media, and communication campaigns. To deliver on commitments, Western Balkan economies must also build institutional capacity in areas such as effective GHG reporting, monitoring and verification mechanisms, and strong and independent energy regulators.

1.4.2. Boosting renewables and generating baseload

The Western Balkans region boasts a significant share of renewable energy, but fuel wood represents a large share. In 2019, renewables, including biofuels, accounted for 18.2% of final energy consumption in the Western Balkans, against only 10.2% in the European Union. However, 60% of the region’s renewable energy supply stems from biofuels – mainly fuel wood used for heating and cooking (Eurostat, 2021[9]). While counted as a renewable energy source, the traditional burning of undried wood in old stoves and ovens is a major contributor to PM2.5 emissions, which are associated with heavy air pollution and premature deaths in the region (World Bank, 2017[43]).

The potential of wind and solar power remains largely untapped in the Western Balkans, despite having become cheaper over recent years. Together, wind and solar account for only 3% of total energy supply in the Western Balkans and 6% of renewable electricity generation. In 2020, total installed capacity amounted to 674 MW of wind power and 109 MW of solar. Existing capacities represent only 5.5% of the cost-competitive potential of 12.2 gigawatts (GW) for wind and 2.5% of the 4.4 GW potential for solar (IRENA, 2017[44]) (World Bank, 2018[45]). While hydropower has a dominant role in renewable energy action plans, and receives a substantial share of incentives for renewables (e.g. feed-in tariffs), wind and solar energy are, so far, subordinate. This does not yet reflect the dramatic reductions in cost for both types of energy, which, since 2010, have dropped by 82% for solar.

To integrate a significant share of intermittent renewables in their electricity mix, Western Balkan economies require flexible electricity systems, including baseload capacity. Electricity production from renewables is variable and requires new approaches to system balancing and sufficient baseload capacity. Unlike power plants that continuously generate electricity from controlled burning processes or geothermal energy, electricity from wind and solar is intermittent and depends on weather and daylight conditions. Current electricity systems in the Western Balkans lack the flexibility and baseload capacity to support a significant increase in the share of renewables. The region’s coal-fired TPPs are largely outdated and slow to shut down and restart. In addition, intraregional trade in electricity remains limited. Once coal-fired power plants have been shut down, the Western Balkan region would need to find alternative, cleaner sources of baseload.

Modern biomass, hydropower based storage, natural gas and regional energy imports could provide flexible baseload capacity in Western Balkan economies. In the context of a regional solution for boosting renewables, Albania could serve as a “battery” of clean baseload. Albania’s hydropower potential could provide energy storage services. In the longer run, quickly dispatchable power from gas-fired plants could replace – in a much more flexible form – the baseload capacity currently provided by coal. However, natural gas reduces emissions relative to coal by only 50% when producing electricity. Moreover, a significant increase in the use of natural gas would require large investments in new pipelines and infrastructure. Modern biomass offers another baseload alternative, particularly in Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro. Improved interconnection with neighbouring economies would allow for balancing through export and import. However, a high reliance on energy imports generates threats to energy security and might result in significant costs and balance of payments challenges. Hydrogen, battery based storage and geothermal energy are other, less feasible alternatives, since they remain costly and still face numerous technical challenges.

Liquid, well-functioning and competitive intra-day balancing markets are a key ingredient for a low-carbon transition. Incorporating a large share of highly variable and intermittent renewable sources in the electricity mixes of Western Balkan economies will increase system balancing needs. At present, Western Balkan economies have deregulated balancing markets, but they remain dominated by incumbents. Further liberalising balancing markets would lead to a higher number of market participants, and lower electricity prices in the long run. A strengthening of cross-border balancing co-operation could improve liquidity and stability of balancing markets, increase the diversity of trade partners and create opportunities for trade of variable renewables amongst neighbouring systems.

Moving to market-based support mechanisms for renewables, by replacing feed-in tariffs (FiTs) with auctions, is a key component for scaling-up cost-competitive renewable energy sources. Market-based support mechanisms such as renewable auctions and feed-in premia (FiPs) can improve transparency in the selection of investors for renewable projects, ultimately helping to bring prices down and reduce the costs of government subsidies. Currently, FiTs exist in all regional economies, but most Western Balkan economies are gradually phasing them out, or maintaining them only for small renewable producers and introducing renewable auctions. Well-functioning, day-ahead electricity markets are a key prerequisite for market-based support mechanisms for renewables in order to calculate the flexible premia paid to support renewables (CEE Bankwatch Network, 2019[46]). At present, the Serbian power exchange (SEEPEX) is the only operational day-ahead market in the region (Energy Community Secretariat, 2021[42]).

Uptake of rooftop PV systems, still largely neglected throughout the region, is an important element of the region’s energy transition and could be boosted through improved support mechanisms for self-consumers. Self-consumers or “prosumers” are households that produce energy for their own consumption, while also feeding into and buying from the grid. So far, installed renewable capacities by self-consumers – mainly photovoltaic installations – remain negligible in the region with 119 registered self-consumers in Kosovo, 42 in North Macedonia, 6 in Montenegro, 1 in Bosnia and Herzegovina and none in both Albania and Serbia. Support schemes for self-consumers are in place across the region, but could be improved. Further, the public often lacks awareness of the benefits of renewable energy and of relevant support schemes for self-consumers. In addition, the up-front costs of renewable energy infrastructure and artificially low electricity prices for households restrain self-consumers.

There is a need to simplify the procedures for connecting with the grid and feeding-in, which remain time-consuming, complex and cumbersome. Administrative procedures for authorisation, permitting and licensing to invest in renewables, for both self-consumers and large-scale projects, typically involve several procedures across multiple institutions and tend to be complex, cumbersome and time-consuming. Information on investment procedures is not always easily available. Improving processes and removing unnecessary administrative burdens and taxation could encourage more investment, particularly by self-consumers. One-stop shops could simplify, streamline and accelerate administrative procedures for investment in renewables.

1.4.3. Investing in energy efficiency

Low levels of energy efficiency in residential and commercial buildings in Western Balkan economies reflect poor insulation, and space heating based on outdated and polluting devices. Households account, on average, for 32.4% of final energy consumption in these economies compared with 26.9% in the EU (2019) (Eurostat, 2021[9]). The share of energy consumption corresponding to buildings ranges from 30% in Bosnia and Herzegovina to almost 50% in North Macedonia with estimated potential energy savings ranging from 20% to 40% (World Bank, 2018[45]). The vast majority of the housing stock in the region is outdated, having been built in the 1950-80s before proper energy efficiency standards were established (EBRD, 2016[47]). A large share of buildings are heated with inefficient stoves and boilers that use wood, lignite and coal and other solid fuels such as waste, and many buildings are poorly insulated (Eurostat, 2021[9]; World Bank, 2020[13]).

Western Balkan economies require comprehensive and widely accepted strategies for energy efficiency, along with a clear designation of institutions responsible for implementing relevant policies and appropriate accountability mechanisms. At present, most economies in the region have failed to designate and hold accountable specific institutions and actors to oversee energy efficiency improvements, including whether strategic documents are implemented and targets are met. As a result, energy efficiency policies are not centralised by one institution and often remain fragmented. Energy efficiency legislation, including laws on energy efficiency and on the energy performance of buildings, have been adopted in all Western Balkan economies. However, actual implementation and adoption of secondary legislation have been slow, and the legislative framework remains patchy in many economies. Further, so far, no economy has adopted a building renovation strategy (Table 1.4).

Table 1.4. Important gaps remain in legal and institutional frameworks for energy efficiency improvements in Western Balkan economies

Legal and institutional frameworks for energy efficiency in Western Balkan economies

|

Legislative framework for energy efficiency |

Dedicated institution for energy efficiency |

Energy efficiency fund |

Building renovation strategy |

Building typology |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Albania |

Law on Energy Efficiency (2015); Law on the Energy Performance of Buildings (2016) |

● |

● |

● |

● |

|

Kosovo |

Law on Energy Efficiency (2018); Law on the Energy Performance of Buildings (2016) |

● |

● |

● |

● |

|

Serbia |

Law on Energy Efficiency and Rational Use of Energy (2021); Law on Housing and Maintenance of Buildings (2016) |

● |

● |

● |

● |

|

North Macedonia |

Law on Energy Efficiency (2020) |

● |

● |

● |

● |

|

Bosnia and Herzegovina |

Separate laws on energy efficiency the FBiH and RS |

● |

● |

● |

● |

Note: Green = in place. Orange = in progress. Red = limited progress.

Source: Authors’ elaboration on Energy Community Secretariat (2021[41]), Annual Implementation Report, https://www.energy-community.org/implementation/IR2021.html; Energy Community Secretariat (2020[48]), Annual Implementation Report, https://www.energy-community.org/implementation/IR2020.html.

The region’s financing gap for energy efficiency remains large. Total investment needs for energy efficiency improvements in buildings in Western Balkan economies amounted to EUR 3.5 billion between 2011 and 2020; however, only EUR 1.4 billion of financing were secured between 2010 and 2021 (Energy Community Secretariat, 2021[42]). Within government budgets, financial resources devoted to energy efficiency improvements tend to be limited, leaving these economies very dependent on donor support. Financing purchase of energy efficient equipment or energy retrofits is also challenging for households, which face high costs and limited incentives. Little experience with this kind of investment means access to finance remains limited for energy efficiency projects. Access to public financing for energy efficiency measures needs to be improved, for example, through dedicated energy efficiency funds endowed with sufficient financial resources. To mobilise private financing for energy efficiency improvements, Western Balkan economies could explore guarantee and regulatory options, such as energy efficiency service companies (ESCOs).

Energy efficiency improvements in multi-apartment buildings could be facilitated through regulatory reforms and appropriate financing mechanisms. Some 39% of residential buildings in Western Balkan economies are multi-apartment buildings (Energy Community Secretariat, 2021[49]). Most were constructed in the 1960s to 1980s under obsolete building standards and have been poorly maintained: as such, their energy performance tends to be poor. Multi-apartment buildings’ homeowner associations face cumbersome decision making, low funding and limited capacity. Generally, the collective decision making requires either a two-thirds majority or even unanimous consent for some matters. At the same time, reserve funds for such buildings are either non-existent or have very limited financial resources. Unsurprisingly, commercial banks in Western Balkan economies are reluctant to lend to homeowner associations. Reshaping the rules on decision making and fee collection for homeowner association could reduce the perceived risk level. Credit guarantees and technical assistance for homeowner associations could further support energy efficiency improvements in multi-apartment buildings (USAID, 2020[50]).

The expansion of modernised district heating systems could replace inefficient heating devices. District heating plays an important role in some parts of the Western Balkans but remains predominantly based on fossil fuels, and subject to high technical losses and a lack of incentives for energy savings. Such heating systems represent around 14% of total heat demand in the region, compared with about 10% for the EU6 as a whole. It is particularly developed in Serbia, with 25% of households connected. Existing systems in the region rely heavily on natural gas (67%), coal and/or lignite (21%), and petroleum products (9%). Billing for district heating systems is often based on lump sums per square meter of heated space rather than on actual consumption, providing no incentives for energy efficiency. Modernised district heating systems, run on renewable energy and based on metering and billing on actual consumption could offer viable solutions for clean urban heat.

1.4.4. Getting prices right through socially responsible carbon pricing and removal of subsidies