Better education and more relevant competencies are prerequisites to boosting productivity, creating jobs, encouraging civic participation and making the Western Balkans an attractive place to live, work and invest in. This chapter puts forward policy recommendations to strengthen education systems at all levels and to build competencies both within and beyond formal education. Over recent decades, Western Balkans economies have made important progress in modernising their education systems, notably with the development of core competency-based curricula. However, people across all age groups still lack competencies relevant for the labour market and for civic participation more broadly. Boosting youth and workforce competencies can foster innovation and unlock new opportunities. Across diverse policy areas, priority should be placed on technical, cognitive, social and transversal competencies, and on creating strong partnerships, especially between the education system and the private sector.

Multi-dimensional Review of the Western Balkans

2. Boosting education and competencies in the Western Balkans

Abstract

The Initial Assessment of this Multi-dimensional Review of the Western Balkans identified education and competencies for economic transformation and civic participation as the top priorities for all economies in the region (OECD, 2021[1]). While economic structures vary significantly, finding new sources of productivity growth and engines for future transformation is an urgent task for all the regional economies. Good jobs are scarce, and young people continue to leave. Boosting youth and workforce competencies can encourage innovation and unlock new opportunities to overcome these trends. The more unfavourable an economy’s current wage-to-productivity ratio is, the more this task becomes urgent, as new and more productive activities must be found to build a strong economy. Beyond economic opportunity, education matters for civic engagement and respect for diversity and for the rule of law – as relatively young and ethnically diverse democracies, this is particularly important for the regional economies.

High quality education tops the list of aspirations for the future in the region. Quality education is an essential element of quality of life for all: young people in school; families; those who want to have opportunities for their own children; those who want to have children in the future; and those who depend on younger generations to shape the future of their societies. With impressive unanimity, quality education ranked topmost in all four aspirational foresight workshops held in the region as part of the Initial Assessment of this review (OECD, 2021[1]).1 The workshops gathered a range of participants from various ministries and agencies, the private sector, academia and civil society, who developed vision statements based on narratives of the lives of future citizens.

This report builds on an extensive peer-learning process with practitioners in the region and expert assessment to provide suggestions for strengthening education and competencies in the Western Balkans. Building on the Governmental Learning Spiral methodology (Blindenbacher and Nashat, 2010[2]), two peer-learning events brought together experts and practitioners from across the region and beyond to prioritise among challenges and solutions, develop ideas for action, and learn from each other (Box 2.1).

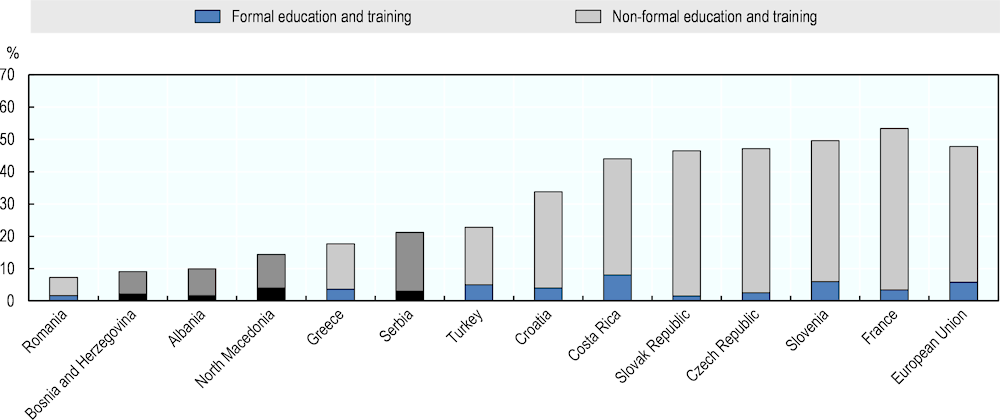

Generating the competencies that can drive economic transformation and future quality of life will require investment and reform in formal education for the young, but also beyond for adults. Formal education must ensure that younger generations are future-ready, have the right set of competencies to thrive in tomorrow’s labour market, and agility to adapt to changing circumstances and new opportunities (Table 2.2). The key issues include quality of teaching, digitalisation and digital skills, the quality and relevance of vocational education and training, curricula modernisation, access and equity, financing, governance and early childhood education. In the age of rapid technological progress and the current need for a green transformation (Chapter 14), many of the skills acquired in formal educational become obsolete, creating a great need for lifelong learning. Beyond formal education, the focus was on boosting competencies of working-age adults by creating opportunities for adult learning, leveraging on foreign direct investment and tapping into a relatively large diaspora.

Successful implementation of selected policy priorities calls for a broad reform that improves the existing education systems, links strategies for competencies with other policy areas, and puts a high premium on building partnerships with various stakeholders, especially the private sector. Economies can reap significant benefits by improving administrative setup within the formal education setting, as well as increasing access to various education levels and improving the quality of teaching. At the same time, building of competencies needs to be integrally linked with other policy areas. Bringing about the green energy transition requires an education system to equip a future workforce with the skills needed to thrive in a transformative and green economy, and active labour market policies to reskill and upskill persons affected by the transition. Finally, reforming education should be a multi-stakeholder effort, implying strong partnerships with various stakeholders, especially the private sector. The private sector provides jobs to people at the end of their education cycle, informs the education system on the needed competencies, and creates opportunities for students and teachers to acquire new competencies, hence the full potential of such collaboration needs to be explored.

This regional chapter on education and competencies is divided into four sections. Section 2.1 looks into which competencies will matter for the Western Balkans in the future. Section 2.2 provides an overarching analysis of key outcomes focusing on formal education and acquisition of competencies beyond formal education. Sections 2.3 and 2.4 analyse policy challenges related to current outcomes and provide policy suggestions that may apply to all regional economies, albeit to different degrees. Whenever possible, policy suggestions are complemented with other country examples to support learning from others. The regional outcomes of the peer-learning workshops constitute the key analytical basis for the present report and have been used to guide the policy sections 2.3 and 2.4.

While the policy priorities discussed under the education and competencies are those that have been selected in the peer-learning as most important, this chapter recognises that there are many other important issues facing Western Balkan education systems that are not addressed here in-depth. For example, making investments in higher education, such as ensuring equal access for all groups and improving labour market relevance of higher education track, is critical for generating new knowledge and foster innovation. As most research happens within universities, the role of higher education and research in creating knowledge and ensuring knowledge transfer is a key basis for productivity gains and - both technical and societal innovation. New knowledge that is developed within universities forms a basis for next generations. While there are variations in higher education quality across the Western Balkans, the lack of equity in access to tertiary education for students coming from disadvantaged groups or backgrounds particularly affects the region. At the same time, low employment rates of young graduates show that tertiary education does not equip the young with appropriate and adequate competencies (Eurostat, 2021[3]).

Box 2.1. Multi-dimensional Reviews of the Western Balkans: From Analysis to Action through peer-learning

Peer-learning, as implemented following the Governmental Learning Spiral methodology was a key process in the Multi-dimensional Review project. With three overarching aims – to identify key issues hampering build-up of competencies at the regional and economy level; to put forward suggestions for future policy actions at the economy level; and to exchange policy experiences – the process brought together key stakeholders from the Western Balkans (Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, North Macedonia and Serbia). The peer-learning on education and competencies comprised two rounds of workshops (Workshop One, 11-12 February 2021 and Workshop Two, 15 April 2021), each attended by 24 experts (about five per economy) representing various societal perspectives, including government, civil society, academia and businesses.

Workshop One started with a regional plenary to select the most important and most urgent issues related to education and competencies in the region (Table 2.1). Quality of teaching received the highest number of votes. This regional chapter and economy-specific chapters (Chapters 2-7) provide a deeper analysis of the selected issues and policy suggestions clustered in two themes: improving the quality and relevance of formal education and boosting the quality of beyond formal education.

Following discussion at the regional level during the Workshop One, participants worked in economy-level groups to start developing ideas for action. These activities became the basis for the Workshop Two. During the two workshops of Round One, participants from each economy met to further specify actions, processes and requirements pertaining to their action plans. In Workshop Two, participants from the five economies reconvened to present progress in developing action plans and to pose to other participants the most pressing question in areas where they lack policy experience. Following the peer-learning exchange at the regional level, participants reassembled in their economy groups to suggest monitoring indicators relevant for their respective action plans.

Table 2.1. Results from the voting on the most important and urgent issues

|

Issues |

Votes |

|

|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Quality of teaching |

******** |

|

2 |

Infrastructure / Technology / Digitalisation of education |

****** |

|

3 |

Vocational education and training quality / Training in professional skills |

****** |

|

4 |

Key competencies |

**** |

|

5 |

Learning outcome-based curricula |

*** |

|

6 |

Lifelong learning |

*** |

|

7 |

Economy and education |

** |

|

8 |

Access to education |

** |

|

9 |

Funding |

** |

|

10 |

Sharing responsibilities between government and private sector |

** |

Source: OECD peer-learning workshops.

Source: Blindenbacher and Rielaender (forthcoming[4]), How Learning in Politics Can Work; Blindenbacher and Nashat (2010[2]), The Black Box of Governmental Learning The Learning Spiral - A Concept to Organize Learning in Governments, World Bank Group, Washington, DC, https://doi.org/10.1596/978-0-8213-8453-4.

2.1. Why and which competencies matter for the Western Balkans?

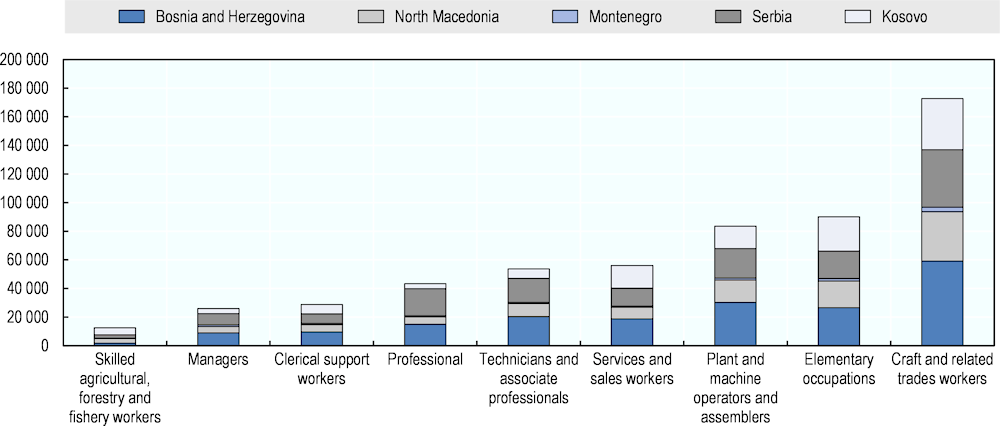

Shared domestic challenges in the Western Balkans such as population ageing and migration are having a major impact on the composition competencies. Population ageing indicates a growing share of the population may not possess the competencies needed in the labour market. In addition, a large elderly population is increasing the need for certain professions, including doctors and nurses, which are in shortage due to high migrations abroad. People of all education levels are migrating, creating significant skills shortages, including technical skills (e.g. construction, mechanical and electrical), which are an important asset for any emerging economy.

Technological progress and climate change are further creating a demand for new competencies, opening up new opportunities for the Western Balkans. As a result of the technological progress, including digitalisation, e-commerce and gig-economy, new sectors and jobs are emerging while others are shrinking, changing the competencies needed in today’s economies. Even within existing occupations, the tasks performed by workers and the competencies needed to carry them out are undergoing significant change (OECD, 2017[5]). Additionally, these trends are changing the ways governments work and deliver services. The COVID-19 pandemic, with its global shift to teleworking and digitalised services, has further accelerated the use of new technologies. Likewise, as the regional economies are in a dire need for green transition (Chapters 14-19), new skills will be needed. The successful transition to a low-carbon economy will only be possible by ensuring that workers are able to transfer from areas of decreasing employment to other industries (Table 2.2).

Beyond technical competencies, cognitive and socio-emotional, as well as transversal competencies also matter (Table 2.2). Employers in modern economies expect prospective employees to have not only general knowledge acquired during the training provided in the academic curriculum but also analytical problem-solving skills, communication skills, management skills, presentation abilities, and the predisposition for lifelong learning and creativity. Moreover, employers value future employees capable of teamwork with abilities that result from applying general knowledge in practice. Creativity and problem solving are also increasingly important, as are entrepreneurial skills and leadership (Gawrycka, Kujawska and Tomczak, 2020[6]). The acquisition of such competencies needs to start already at the early levels. The cognitive and socio-emotional skills acquired in the first five years of a child’s life have crucial and long-lasting impacts on later outcomes (OECD, 2021[7]).

Table 2.2. Key competencies for the future

|

Technical competencies |

Cognitive and social competencies |

Transversal competencies |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Digital competencies |

Green competencies |

||

|

|

|

|

Source: Barclays (2021[8]), Emerging digital skills, https://digital.wings.uk.barclays/digital-learning-blog/emerging-digital-skills/; European Commission (2022[9]), The Digital Competence Framework 2.0, https://joint-research-centre.ec.europa.eu/digcomp/digital-competence-framework-20_en; OECD (2021[7]), OECD Skills Outlook 2021: Learning for Life, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/0ae365b4-en; OECD/Cedefop (2014[10]), Greener Skills and Jobs, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264208704-en; OECD (2019[11]), Future of Education and Skills 2030 - A Series of Concept Notes, https://www.oecd.org/education/2030-project/teaching-and-learning/learning/learning-compass-2030/OECD_Learning_Compass_2030_Concept_Note_Series.pdf; OECD (2019[12]), Transformative Competencies for 2030 - Conceptual Learning Framework, https://www.oecd.org/education/2030-project/teaching-and-learning/learning/transformative-competencies/; UNESCO-UNEVOC (2022[13]), TVETipedia Glossary, https://unevoc.unesco.org/home/TVETipedia+Glossary/filt=all/id=577; UNESCO (2021[14]), Assessment of socioemotional skills among children and teenagers of Latin America, https://unesdoc.unesco.org/in/documentViewer.xhtml?v=2.1.196&id=p::usmarcdef_0000377512_eng&file=/in/rest/annotationSVC/DownloadWatermarkedAttachment/attach_import_39234ca6-908e-4ad5-81f7-3098560848ee%3F_%3D377512eng.pdf&locale=en&multi=true&ark=/ark:/482; UNIDO (2021[15]), What are green skills?, https://www.unido.org/stories/what-are-green-skills#:~:text=Simply%20put%2C%20green%20skills%20are,sustainable%20and%20resource%2Defficient%20society.

2.2. Developments in the Western Balkans in building key competencies: Progress and challenges

2.2.1. People in the Western Balkans continue to lack competencies needed for economic transformation and civic engagement

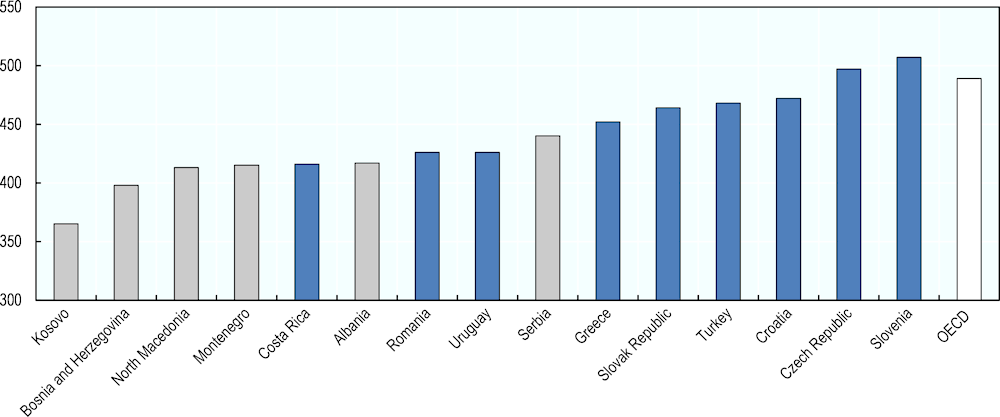

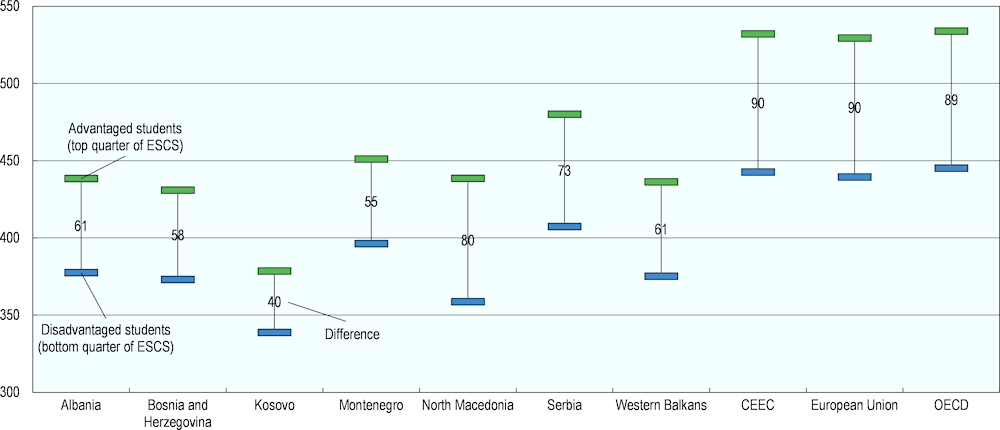

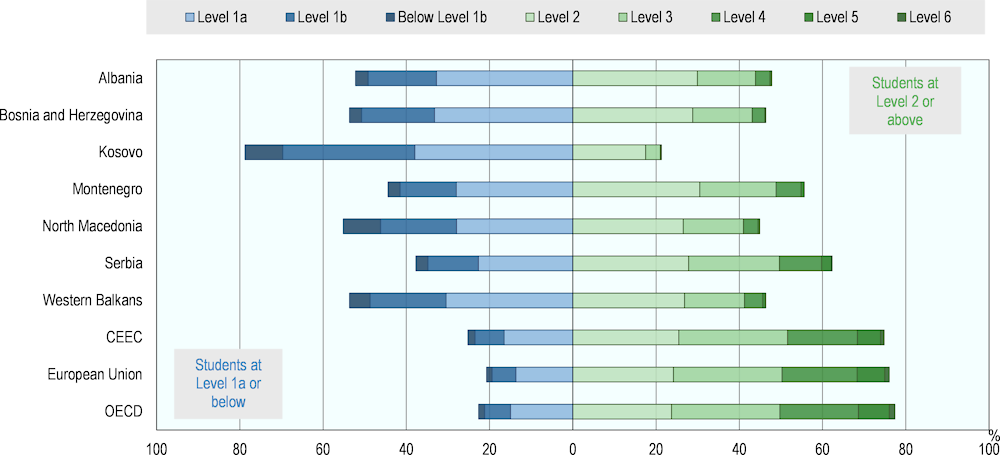

The OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) shows the need to increase students’ outcomes in reading, mathematics and science in the Western Balkans. With the exception of Serbia, most Western Balkan economies trail behind international benchmarks (Figure 2.1). On average across Western Balkan school systems, less than half (46%) of students scored above baseline proficiency in reading (PISA Level 2 and above) compared with three quarters (77%) in OECD countries and a similar proportion (76%) in EU countries (Figure 2.2) (OECD, 2020[16]). The share of Western Balkan students who achieved minimum proficiency in the other two testing subjects (mathematics and science) ranged from about 23% to 62%, depending on the economy and the subject. In both cases, this is again considerably below OECD averages of between 76% and 78%. A negligible share of students in all economies were among the “top achievers” in the PISA assessment, scoring above Level 5. Finally – and most worryingly – limited progress or even regress has been noted in many economies across the different PISA assessment. In North Macedonia, low performers (those who score below Level 2, the minimum level of proficiency) increased by nearly 7% between 2000 and 2015 (OECD, 2016[17]).

Figure 2.1. There is scope to further improve the education outcomes in the Western Balkans

Figure 2.2. Proficiency levels of students in reading is trailing behind benchmark economies

Source: OECD (2020[16]), Education in the Western Balkans: Findings from PISA, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/764847ff-en.

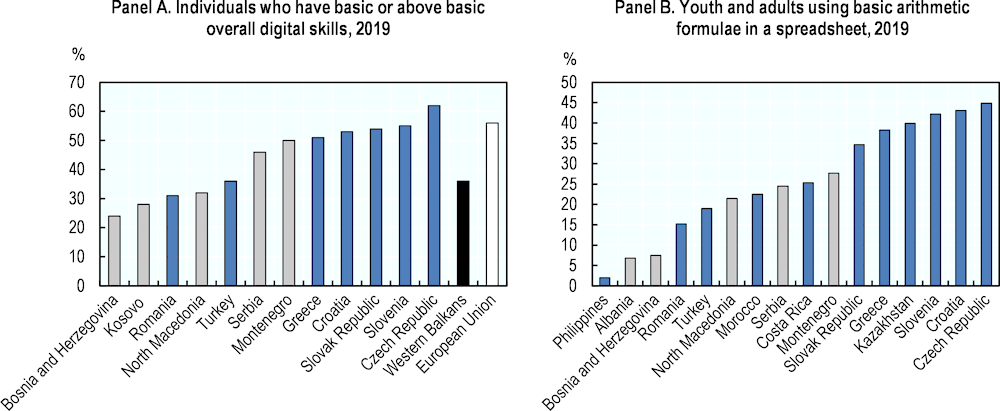

To unleash the full potential of digital technologies, there is further scope to increase digital skills of the population in the Western Balkans – both among students and adults. Apart from Serbia and Montenegro, the share of individuals with basic or above basic digital skills is relatively low in comparison to the benchmark economies from the European Union (Figure 2.3 – Panel A). Some of the Western Balkan economies have a relatively small share of people who have used basic arithmetic formulae in a spreadsheet, indicating lack of key computer skills, which are important requirements for many employers (Figure 2.3 – Panel B).

Figure 2.3. There is further scope to increase digital and technical computer skills in the Western Balkans

Source: Eurostat (2021[3]), Database, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database; UNESCO (2020[19]), UIS Statistics, http://data.uis.unesco.org/.

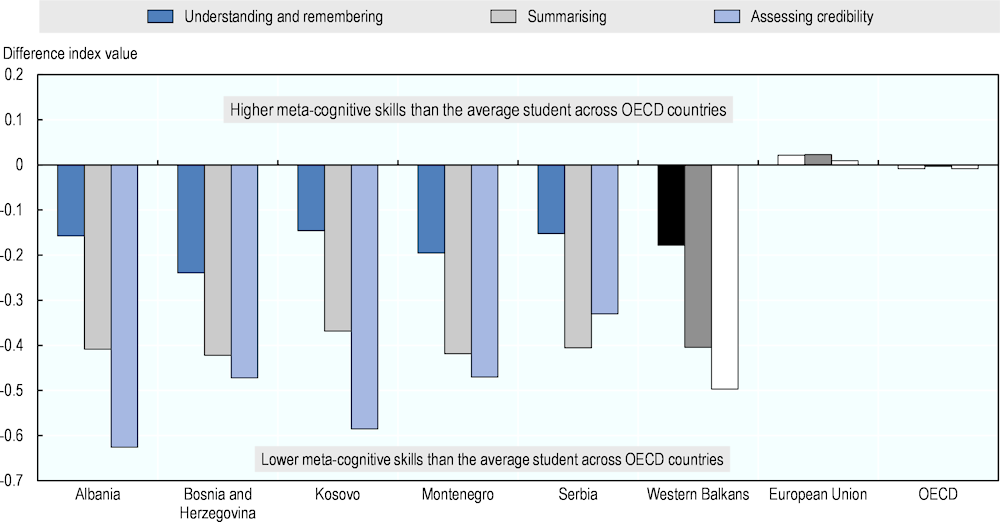

The Western Balkan economies should also focus on strengthening meta-cognitive skills, critical cross-cutting competencies. PISA 2018 defines meta-cognitive skills as knowing how to guide one’s own understanding and learn in different contexts. Having meta-cognitive skills is crucial in modern societies because they help individuals navigate, interpret and solve unanticipated problems, important especially on today’s fast-evolving labour markets (OECD, 2020[16]). Students in the Western Balkan economies rank well below the OECD average on this measure (Figure 2.4).

Figure 2.4. Meta-cognitive skills in reading are relatively low in the Western Balkans

Source: OECD (2020[16]), Education in the Western Balkans: Findings from PISA, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/764847ff-en.

2.2.2. Relatively large skills mismatch and skills gaps are rendering the investments in education ineffective and slowing down innovation

Many adults lack competencies in demand in the Western Balkans labour market. Employer surveys, such as the World Bank’s Skills Measurement Program, indicate that hiring difficulties in the region often stem from skills shortages: a high share of firms surveyed state that the education system does not provide the skills needed in the current labour market (World Bank, 2021[20]). In turn, employees surveyed indicate that their education does not prepare them well for the needs of the job market. In some regional economies, tracer studies of VET graduates show that limited practical training and lack of adequate equipment impact the skills acquired during education (Section 2.3.2). In the 2021 Balkan Barometer surveys, about one-quarter of respondents noted that skills acquired during education do not meet the needs of their job (Regional Cooperation Council, 2021[21]).

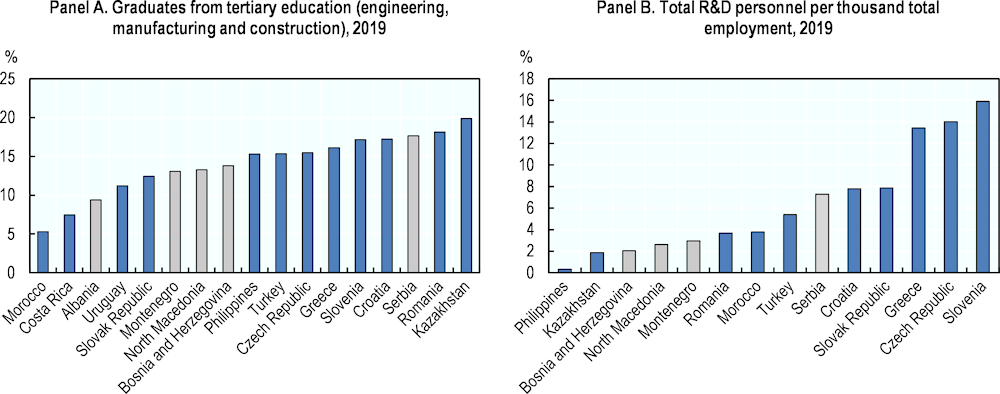

A lack of tertiary graduates in technical fields affects productivity and innovation. Apart from Serbia, regional economies have a relatively low share of graduates from engineering, manufacturing and construction programmes (Figure 2.5 – Panel A). These types of degrees will be important for economic transformation based on technological development. In terms of research and development (R&D) personnel per thousand total employment, the region trails behind many of the benchmark economies (Figure 2.5 – Panel B).

Figure 2.5. A lack of graduates with technical tertiary backgrounds and of R&D personnel shows an important skills gap

Note: Panel B: The full-time equivalent (FTE) of R&D personnel is defined as the ratio of working hours actually spent on R&D during a specific reference period (usually a calendar year) divided by the total number of hours conventionally worked in the same period; it can be calculated by individual or by a group.

Source: UNESCO (2020[19]), UIS Statistics, http://data.uis.unesco.org/.

2.2.3. Weak labour market outcomes limit incentives for investment in education and people lack trust in the educational system

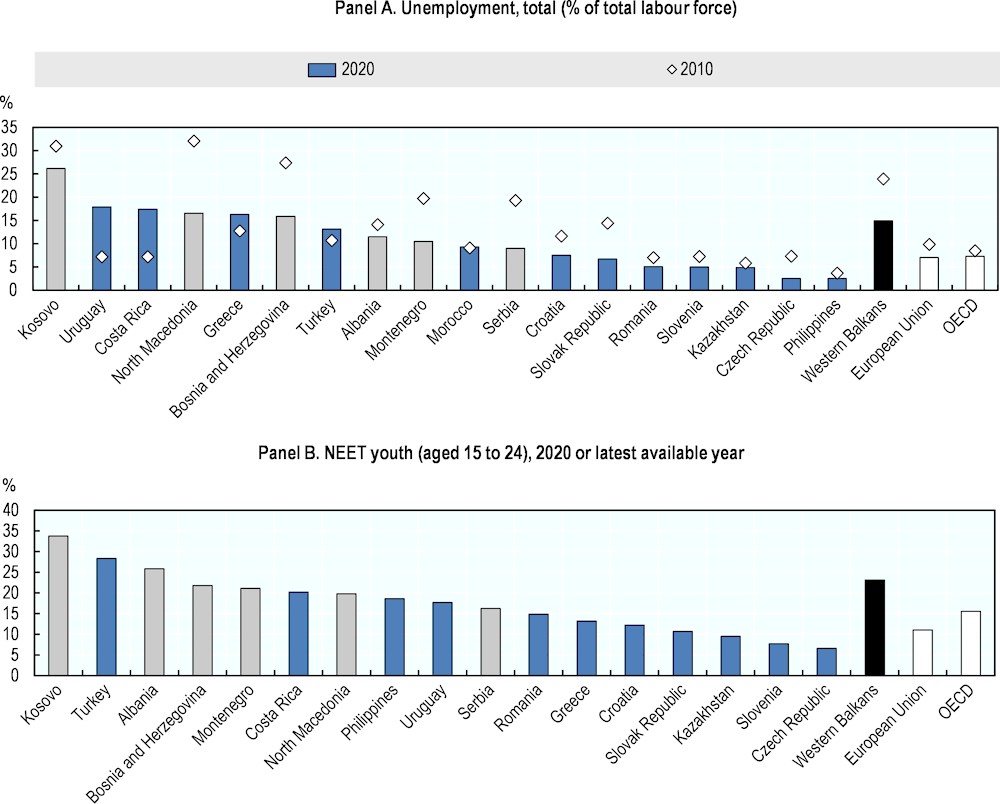

While the build-up of competencies matters a great deal, weak labour market outcomes limit incentives for investment in education and drive emigration. Despite significant progress in recent years, the unemployment rate in Western Balkan economies remains high at 14.9% in 2020 (Figure 2.6 – Panel A). Moreover, most of the unemployed have been without a job for longer than one year: the share of long-term unemployed in 2019 was 66% (World Bank/WIIW, 2021[22]). This group is at risk of losing valuable skills. Youth, who ought to be a driving force in applying new competencies, are particularly affected by labour market outcomes; at present, youth unemployment rates in the region are among the highest in peer economies and double the OECD average (World Bank, 2021[23]). About one in four young people is without employment or a training activity (Figure 2.6 – Panel B). In the latest Balkan Barometer survey, only 30% of respondents stated they had been able to find a job within one year of graduation; for 20% of respondents, it took two or more years to secure their first job (Regional Cooperation Council, 2021[21]).

Meritocracy and equality of opportunity are also critical incentives for investment in education and skills attainment. A high share of people in the Western Balkans region do not believe that knowledge and skills are the main drivers of life success. In the 2016 Life in Transition Survey, fewer than 20% of low- and middle-income respondents agreed that intelligence and skills are the most important factors for success and fewer than 40% agreed that hard work brings success. Instead, nearly 50% of low- and middle-income respondents agree that political connections are the main success factor (EBRD, 2016[24]). In the 2021 Balkan Barometer, 54% of respondents in the region identified knowing the right people as the key success factor in life (Regional Cooperation Council, 2019[25]).

Figure 2.6. High unemployment and weak job prospects remain a major challenge, especially for youth

Note: Panel A – the latest available year for Albania is 2019 and 2016 for Morocco, 2012 is used instead of 2010 for Kosovo. Panel B – data for Albania and Uruguay are for 2019, data for Kazakhstan is for 2016.

Sources: Kosovo Agency of Statistics (2021[26]), Askdata (database), https://askdata.rks-gov.net/PXWeb/pxweb/en/askdata/?rxid=4ccfde40-c9b5-47f9-9ad1-2f5370488312; World Bank (2019[27]), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators. ILO (2021[28]), Share of youth not in employment, education or training (NEET) by sex – ILO modelled estimates, Nov. 2019 (%) – Annual (dataset), www.ilo.org/shinyapps/bulkexplorer45/?lang=en&segment=indicator&id=EIP_2EET_SEX_RT_A.

2.3. Improving the quality and relevance of formal education

Strengthening the acquisition of relevant competencies at all levels should be a priority. Eight policy areas have been highlighted by regional stakeholders as needing urgent reform during the peer-learning process:

Improving the quality of teaching. The quality of the teaching profession is a key driver of education quality. A previous OECD review of the Western Balkans already identified the importance of investing more to boost the attractiveness of the teaching profession and teacher professional development (OECD, 2021[29]). Recent evaluation and assessment reviews of three Western Balkan education systems (Albania, North Macedonia Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina) also underlined the importance of this issue – and of initial teacher preparation in particular (Maghnouj et al., 2020[30]; OECD, 2019[31]; Maghnouj et al., 2019[32]; Guthrie et al., 2022[33]).

Strengthening VET. Many studies underline the importance of reform of the upper-secondary VET system in the Western Balkans (Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation, 2009[34]; OECD, 2021[29]). As many of the most disadvantaged students in the Western Balkans are directed to this sector (OECD, 2020[16]), VET reforms should be prioritised. In this context, the importance of work-based learning has been given particular emphasis (OECD, 2018[35]).

Increasing the use of digital technologies in education. Use of digital technologies goes beyond use of digital technologies for learning purposes – as a promising area for development of new products and services, use of digital technologies can stimulate students to embark in professions with high potential for growth. The COVID-19 pandemic has created several major challenges. Initially, as schools were closed, it prompted a sudden and unexpected transition to remote learning. Looking ahead to the medium-term challenges of schools reopening and learning recovery, governments recognise that the disruption to learning will have had the greatest effects on the most disadvantaged pupils. More broadly, the situation has highlighted longstanding weaknesses in digital learning capacity in the region, in terms of home and school digital infrastructure and in the capacity of teachers to effectively use digital resources.

Updating and modernising curricula to impart relevant knowledge and skills. Curricula are powerful levers for strengthening student performance and well-being, and for preparing students for future jobs. Having a competence-based curricula is critical to ensure consistency and equity in the delivery of education and to target learning outcomes, skills and competencies to be achieved at each stage of the education process (OECD, 2020[36]). Western Balkan economies have developed competency-based curricula; however, implementation is lagging and teachers and schools need more support to adapt curricula to their own needs.

Fostering equitable and inclusive education at all levels. Equity in education means that personal or social circumstances – such as gender, ethnic origin or family background – are not obstacles to achieving educational potential (fairness) and that all individuals reach at least a basic minimum level of skills (inclusion). The highest performing education systems among OECD countries provide high quality education that is also equitable. In such systems, most students attain high levels of skills, regardless of their background, which translates into better socio-economic outcomes (OECD, 2012[37]). In the Western Balkans, access to and attainment of education need to be improved for the Roma and other minorities, rural residents and students with special needs. In some economies, girls’ educational attainment also needs to be improved.

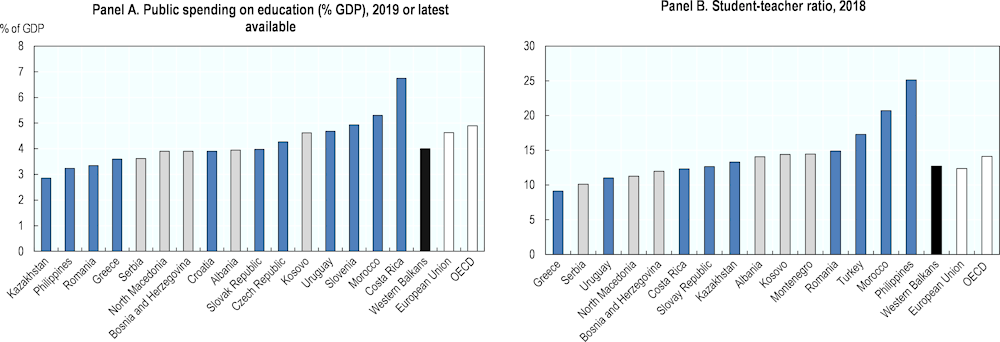

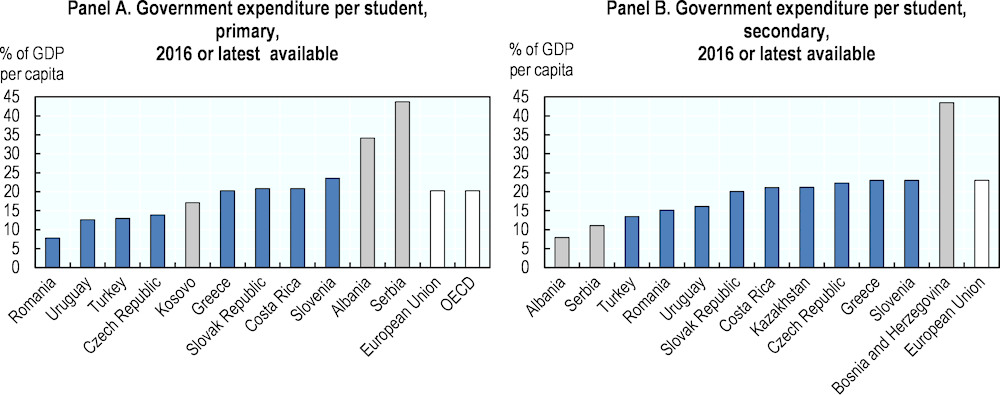

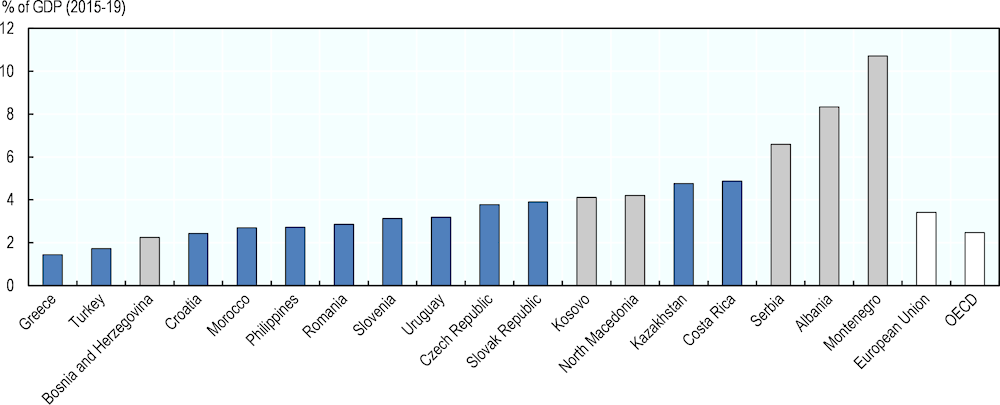

Increasing and improving the financing of education. In the Western Balkans, insufficient funding for education impacts learning outcomes at all levels, particularly early childhood education and care (ECEC) and secondary education (including VET). Even in economies in which public spending on education as a share of GDP is on par with OECD countries, high staff costs – related to excess numbers of teaching and non-teaching staff – crowd out spending on infrastructure, teaching materials, technology and equipment.

Strengthening the governance and co-ordination of education. Common governance challenges in education in the Western Balkans include weak co-ordination, inadequate data collection and limited use of data to monitor and evaluate education policy.

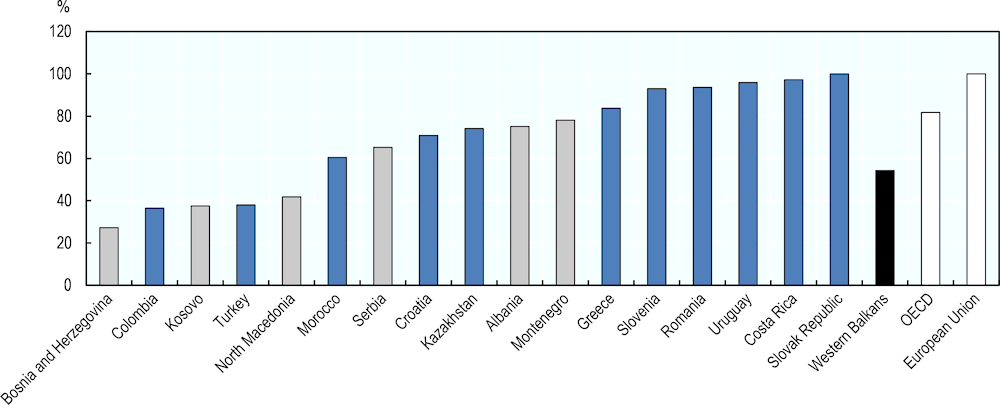

Increasing the access to and quality of ECEC. A growing body of research points to significant benefits from ECEC in children’s development, learning and well-being. High quality ECEC can improve cognitive abilities and socio-emotional development. Children who start their education early are more likely to have better outcomes when they are older, which is particularly important for children from disadvantaged socio-economic backgrounds who have more limited opportunities for learning in their home environment. Providing high-quality childcare also enables increased labour force participation of women, providing parents with better work-life balance. Access to ECEC in the Western Balkans is very limited, especially for the poor and those living in rural areas. The biggest gaps in ECEC enrolment exist for children aged 0-3 years.

2.3.1. Improving the quality of teaching

Western Balkan economies are now increasing attention on teaching quality. There is good evidence that teacher quality is one of the single most important factors in schooling quality (Schleicher, 2015[38]). Teacher quality depends on attracting into the teaching profession individuals of high ability, and effectively preparing, motivating and developing those individuals throughout their teaching career. In the Western Balkan economies, improving teaching quality would require better implementation and use of teacher standards to strengthen initial teacher education (ITE), continuous professional development (CPD) linked to teacher appraisal, compensation and career development (Table 2.3).

Table 2.3. Teacher standards in the Western Balkans have been developed, but their use varies

|

Year teacher standards were introduced |

Level and consistency of implementation |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Albania |

2013, revised in 2016 |

Consistent / moderate implementation |

|

Bosnia and Herzegovina |

2016-17 |

Inconsistent / low implementation |

|

Kosovo |

2004, revised in 2017 |

Consistent / moderate implementation |

|

Montenegro |

2016 |

Consistent / moderate implementation |

|

North Macedonia |

Developed in 2016 |

Consistent / low implementation |

|

Serbia |

2011 |

Consistent / moderate implementation |

Source: Table 3.2 in OECD (2020[16]). Education in the Western Balkans: Findings from PISA, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/764847ff-en.

In the Western Balkan economies, the quality and breadth of ITE do not align with adequate standards to train high quality teachers. Entry criteria are neither rigorous nor linked to estimates of the numbers of teachers needed in the future. Often, ITE is insufficiently linked to teacher professional standards and frequently lacks the kind of programme-specific accreditation necessary to ensure high quality provision. Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and North Macedonia have processes for accrediting higher education institutions that provide ITE, but none of the accreditation criteria are specific to teacher education (Maghnouj et al., 2020[30]; OECD, 2019[31]). Moreover practical teaching experience elements of the programmes are often inadequate (Maghnouj et al., 2019[32]). Many teachers, especially those not educated in pedagogical faculties, also lack training in important teaching subjects such as pedagogy, development psychology, teaching methods and other didactics.

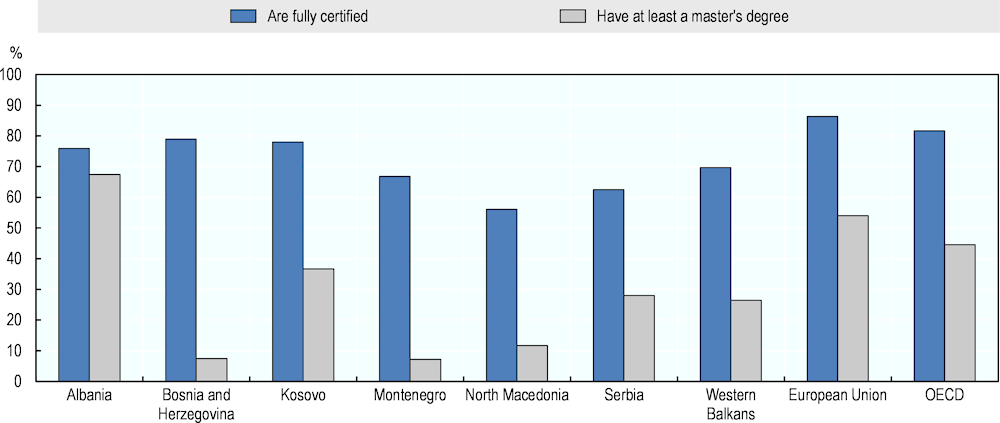

Weaknesses in teacher education are also notable in that higher qualification of teachers is not necessarily associated with better student performance. To raise the standard of teaching, many OECD countries are now encouraging or insisting on master’s level qualifications for teachers. Data from PISA show that, while it varies by economy in the region, overall, teachers in the Western Balkans are less likely to be fully certified and hold a master’s degree than their counterparts in OECD and EU countries (Figure 2.7). In Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro, fewer than 10% of teachers have master’s degrees. The region’s top PISA performers, Serbia and Albania, are the only regional economies that insist on master’s level education for new teachers (OECD, 2020[16]). But that does not always translate into high performance by students: nearly 40% of teachers in Kosovo have such qualifications, yet Kosovar students have one of the lowest PISA scores in Europe.

Figure 2.7. In most regional economies, there is scope to increase teachers’ qualifications

Note: Teacher certification in North Macedonia and Bosnia and Herzegovina is highly decentralised; in most cases, it requires simply completing ITE. Given this context, it is possible that principals from these systems had difficulty interpreting whether their teachers were “fully certified.” Thus the results should be interpreted with caution.

Source: OECD (2020[16]), Education in the Western Balkans: Findings from PISA, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/764847ff-en.

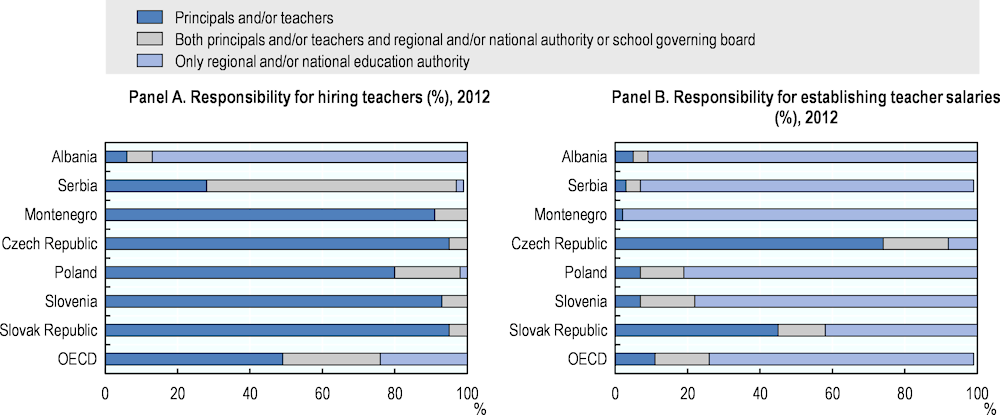

Hiring of teachers should be merit-based to incentivise the entry of higher-quality students into the teaching profession. In most economies in the region, the lack of clear guidelines for hiring and firing teachers has also led to the perception that the appointment and promotion of teachers and school staff are based on political affiliation or favours, not (only) on competency (Figure 2.8).

Compensation and career progression are often not linked to teacher performance. In most economies, teacher salaries are relatively low (Table 2.4). In most cases, they tend to be determined by central governments and linked mainly to experience rather than performance (Table 2.4). As a result, salaries cannot act as an incentive for improved teacher performance.

Table 2.4. Teachers’ salaries in the Western Balkans are low in comparison to benchmark economies

Annual gross statutory starting salaries (EUR) for full-time, fully qualified teachers in public schools, 2019/20

|

Early childhood education |

Primary education |

Lower secondary education |

Upper secondary education (general) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Albania |

4 189 |

4 938 |

5 132 |

5 423 |

|

Bosnia and Herzegovina |

6 120 |

6 528 |

6 936 |

8 160 |

|

Kosovo |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

North Macedonia |

6 624 |

6 811 |

6 811 |

7 111 |

|

Serbia |

6 330 |

7 396 |

7 396 |

7 396 |

|

Czech Republic |

12 792 |

13 608 |

13 608 |

13 608 |

|

Croatia |

- |

14 376 |

14 376 |

14 376 |

|

Greece |

13 104 |

13 104 |

13 104 |

13 104 |

|

Montenegro |

9 715 |

9 715 |

9 715 |

9 715 |

|

Poland |

8 076 |

8 076 |

8 076 |

8 076 |

|

Romania |

8 969 |

8 969 |

8 969 |

8 969 |

|

Slovak Republic |

8 592 |

10 646 |

10 646 |

10 646 |

|

Slovenia |

19 529 |

19 529 |

19 529 |

19 529 |

|

Turkey |

7 926 |

7 926 |

8 242 |

8 242 |

Source: Eurydice (2021[39]), Teachers' and School Heads' Salaries and Allowances in Europe: 2019/20, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2797/575589

Figure 2.8. Schools tend to have limited responsibility for hiring teachers and determining teacher salaries

Note: Percentage of students in schools at which principals reported that “only principals and/or teachers”, “only regional and/or national authority”, or “both principals and/or teachers” and “regional or national education authority”, or “school governing board” has/have considerable responsibility in the tasks.

Source: OECD (2013[40]), PISA 2012 Results: What Makes Schools Successful? Resources, Policies and Practices, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264201156-en.

The Western Balkan economies also need to put a stronger spotlight on teachers’ CPD. While with the exception of Bosnia and Herzegovina, CPD for teachers is legally mandated in the Western Balkans, in-service teacher training is quite limited and largely dependent on donor financing (ETF, 2018[41]). Even in Serbia, supply constraints (including availability and quality of training) limit the acquisition of CPD. In fact, while Serbian teachers are required to complete 100 credit points of CPD (1 hour of training equals 1 point) over 5 years, in 2017, less than half of teachers had achieved 80 credit points over the reference period (Maghnouj et al., 2019[32]). A survey of teachers found that lack of financial resources is the primary obstacle to fulfilling credit requirements, followed by dissatisfaction with the training offer (i.e. courses offered do not correspond to the demand for skills expressed by teachers) (Maghnouj et al., 2019[32]). Participation in CPD should also be linked to teachers’ career progression and compensation.

Policy options for improving the quality of teaching

Improving teaching quality in the Western Balkan economies requires actions on multiple fronts. This includes raising the standard for entry into the teaching profession, strengthening ITE, expanding the availability and quality of in-service training, and improving incentives for better performance and CPD through better performance appraisal, as well as linking salaries and career advancement to performance. As part of the OECD Reviews of Evaluation and Assessment in the Western Balkans, the OECD also provides a set of general recommendations arguing for better forecasting for the teacher workforce, higher standards for entry into the profession and improved teacher salaries, alongside career opportunities that would attract high quality and motivated graduates into the profession (Box 2.2). Specific policy options to improve the quality of teaching, include:

Strengthen initial teacher education

Set demanding standards for entry into ITE to ensure a balance of supply and demand and to raise the standard for entry into ITE. Where relevant, demanding minimum matura marks (i.e. marks from the secondary school exit exam) requirements should be set for those entering ITE. Teacher standards, which have become a common policy feature in most OECD and EU countries, set out key expectations of teachers in terms of their competencies. These standards should become the foundation and point of reference for ITE and CPD, as well as for teacher appraisal and career development, including promotion.

Strengthen the level and consistency of implementation of teaching standards developed across the region. While all Western Balkan economies now have a set of system-wide teacher standards, these now need to be fully implemented, especially in ITE programmes. The design and delivery of ITE should ensure that new teachers develop the competencies specified by the professional standards, that ITE programmes are aligned with curricular development, and that ITE include sufficient practical experience to ensure qualified teachers are ready for the classroom. An accreditation regime should be in place to ensure ITE programmes comply with these requirements.

Accredit teaching programmes according to necessary teaching competencies in line with the developed teaching standards. The qualification levels associated with ITE may be less important than the substantive content of programmes. OECD work on this topic has identified some key desirable features of strong ITE systems (OECD, 2013[42]), including that such systems should align to a clear vision of what is expected of teachers – articulated through teacher professional standards. ITE programmes should set demanding standards for potential teachers, while also offering a clear career route and salaries that attract able candidates. They should also offer sufficient practical teaching experience to prepare novice teachers for the realities of working in the classroom. Ultimately, they should lead to a recognised certification that may be supported by a demanding examination. Finally, education systems should embed ITE in a coherent set of policies related to the teaching profession, including induction programmes for novice teachers, CPD, effective appraisal arrangements and professional networking opportunities that help teachers to learn from each other. In Ireland, ITE programmes must be accredited; in turn, accreditation requires alignment of ITE with nationally expected teacher competencies and careful attention to a practicum, during which trainee teachers are expected to plan and implement lessons and receive feedback on their performance (The Teaching Council, 2017[43]).

Consider the introduction of a economy-wide examination for licensing teachers upon completion of an accredited ITE programme to support more consistent and higher standards in the profession. System-level data from PISA show that a competitive examination is required to enter the teaching profession for pre-primary, primary and secondary school in France, Japan, Korea, Mexico, Spain and Turkey and in the partner countries and economies of Brazil, Dominican Republic, Malta, Peru, Chinese Taipei, Thailand and the United Arab Emirates. In Luxembourg and Uruguay, a competitive examination is required exclusively for pre-primary and primary school teachers; in Qatar, it is required exclusively for primary and secondary teachers (OECD, 2016[44]). In Germany, there is a multi-step process. Upon completion of ITE, comprising a consecutive three-year bachelor’s and two-year master’s degree, prospective teachers much pass the First State Examination (first Staatsexamination) and conclude preparatory service (that consists of a teaching practicum and attending teachers’ workshops). They must then pass the Second State Examination (second Staatsexamination), which has to be taken before a state examination board or a state examination commission (Maghnouj et al., 2019[32]).

Mandate practical training for teachers during their initial education accompanied by devoted mentors. This may be particularly important in the Western Balkans where some ITE programmes lack sufficient well-structured classroom experience. Supportive feedback, advice and appraisal can be extremely helpful in the development of pedagogical skills of future teachers.

Boost availability and quality of in-service teacher training

Provide induction and other in-service training for new teachers through, for example, peer-learning initiatives and mentorships with more experienced teachers. Induction programmes, in which new teachers receive supportive feedback, advice and appraisal groups of teachers who teach similar subjects or grade levels can be extremely helpful in the development of pedagogical skills and is a key element of effective teacher preparation. Evidence shows the value of induction programmes. In Ontario (Canada), trained mentors offer guidance to new teachers along with a systematic appraisal process involving in-class observation by the school principal (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2021[45]; Ontario Ministry of Education, 2010[46]).

Support “on-the-job” teacher learning to enhance effective teaching through, for example, an online platform with technical resources and e-learning opportunities. Providing teachers with resources they can access easily and at no cost facilitates their learning and CPD. In the Czech Republic, the Ministry of Education, Youth, and Sport launched (in 2020) the “Distance Education” website to provide distance education for schools and teachers. This website contains links to online educational tools, updated information and examples of good practices, as well as experiences regarding distance education (World Bank, 2020[47]).

Strengthen incentives for better teacher performance and continuous professional development, including through transparent performance evaluation

Introduce objective and standards-based appraisals of teacher performance at the state level, including self-evaluation processes to help teachers identify their own learning goals. Regular teacher appraisals are necessary to inform teachers of their performance vis-à-vis relevant benchmarks. But they are effective only if followed up with feedback, including concrete steps to improve areas of underperformance, or with rewards and incentives to recognise good performance and encourage further growth. Incorporating student feedback into the appraisal process is also important. The Australian Teacher Performance and Development Framework provides a good example of the annual appraisal process for all teachers, based on the Australian Professional Standards for Teacher (AITSL, 2012[48]).

Link career advancement and compensation to results from appraisal. Teachers need to be incentivised to innovate and take initiative in the classrooms and outside of them. If their strong performance is rewarded with higher compensation or faster career progression, they are more likely to invest more in their CPD and to strive to continuously improve their teaching. In Singapore, annual performance appraisal results over a period of three years inform promotion along the teaching track and typically involve the review of a professional portfolio containing evidence of teaching practice. Teachers are appraised against competencies and standards that relate to each stage of the career track. Once promoted, the Ministry of Education and the National Institute of Education offer teachers free courses and trainings relevant to their new positions (Maghnouj et al., 2020[30]).

Consider using school evaluation processes to monitor and improve school performance. This can provide strong incentives to principals and municipalities to improve the quality of schooling within their own constituency.

Improve teaching quality by strengthening school leadership. Principals can support improvement of teaching through a number of leadership roles, including observing instruction, supporting teachers’ professional development and collaborating with teachers to improve instruction (Schleicher, 2015[38]). This requires complementing principals’ initial training with opportunities for continued professional development. Collaborative professional learning activities, where principals work together to examine practices and acquire new knowledge, can be particularly effective (DuFour, 2004[49]). In Australia, the Netherlands and Singapore, which have high education outcomes, a large share of principals report participation in such activities (OECD, 2014[50]).

Box 2.2. OECD reviews of evaluation and assessment in the Western Balkans

To attract high quality and motivated graduates into the teaching profession, an earlier OECD review of the Western Balkans argued for higher standards for entry into the profession, along with improved teacher salaries and career opportunities. These recommendations remain valid. More recently, the OECD conducted a series of reviews on evaluation and assessment policies in the education systems of Serbia, Albania, North Macedonia and Bosnia and Herzegovina. These reviews, conducted in many OECD and other countries, also provide a rich source of policy analysis and recommendations related to the teaching profession.

These reviews show how the components of evaluation and assessment – student assessment, teacher appraisal, school evaluation, school leader appraisal and system evaluation – can be developed in synergy to improve teaching. This work has identified three hallmarks of a strong evaluation and assessment framework:

Setting clear standards for what is expected nationally of students, teachers, schools and the system overall. Countries that achieve high levels of quality and equity in education set ambitious goals for all while also being responsive to different needs and contexts.

Collecting data and information on current learning and education performance. This is important for accountability (i.e. to ensure follow through on objectives) and for improvement, so that students, teachers, schools and policy makers receive the feedback they need to reflect critically on their own progress and to remain engaged and motivated to succeed.

Achieving coherence across the evaluation and assessment system. School evaluations should value the types of teaching and assessment practices that effectively support student learning. In turn, teachers should be appraised in relation to knowledge and skills that promote education goals.

Source: OECD (2013[42]), Synergies for Better Learning: An International Perspective on Evaluation and Assessment, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264190658-en; OECD (2018[35]), Competitiveness in South East Europe: A Policy Outlook 2018, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264298576-en; Maghnouj et al. (2020[30]), OECD Reviews of Evaluation and Assessment in Education: Albania, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/d267dc93-en; OECD (2019[31]), OECD Reviews of Evaluation and Assessment in Education: North Macedonia, https://doi.org/10.1787/079fe34c-en; Maghnouj et al. (2019[32]), OECD Reviews of Evaluation and Assessment in Education: Serbia, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/225350d9-en; Guthrie et al. (2022[33]), OECD Reviews of Evaluation and Assessment in Education: Bosnia and Herzegovina, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/a669e5f3-en.

2.3.2. Strengthening vocational education and training (VET)

The VET model in Western Balkan education systems has a solid basis and shares similarities with many countries. Education in the Western Balkans is comprehensive up to the end of lower-secondary education. Thereafter (i.e. at the upper-secondary level), it is tracked into vocational and general programmes (sometimes alongside much smaller tracks such as the arts) (OECD, 2017[51]). This structure is common internationally and found in many European countries (e.g. the Czech Republic, France, Norway, Spain and Sweden) and around the world (e.g. China, Korea and many parts of Latin America). Often, as in the Western Balkans, academic selection determines whether a student enters into the general or vocational track. This structure contrasts with the early tracking arrangements, in which the divide between general and pre-vocational tracks takes place upon entrance to lower-secondary education (e.g. Germany, the Netherlands and Switzerland) or where upper-secondary education is generally comprehensive but sometimes includes vocational modules (e.g. the United States) (for a classification of different types of upper-secondary tracking, see Green et al. (2021[52])).

Following the collapse of communism, the regional economies faced a great need to reform their VET system. Previously, large state-owned companies – as part of their corporate responsibilities – collaborated with vocational schools to deliver a great deal of work-based learning. Following the transition to market economies, this arrangement collapsed; Western Balkan economies have since faced the laborious task of establishing the types of partnerships between private sector employers and vocational schools that underpin effective VET. A patchwork of efforts (some economy-wide and some local) have been pursued over the last decade to address the challenge of increasing the labour market relevance of VET programmes. Albania has implemented a range of projects (e.g. “Skills for Jobs”) to develop apprenticeships in some regions. Montenegro has established a web portal to exchange information between employers and vocational schools. Kosovo has been piloting an information management system to facilitate work-based learning (OECD, 2018[35]).

Despite these efforts, the quality of education of VET programmes remains a challenge. In terms of learning outcomes, PISA data provide a snapshot of performance differences between students at age 15 who attend VET programmes and general education programmes. Similar to international peers, on average across the Western Balkans, students enrolled in general education programmes scored 435 points in reading, whereas those enrolled in vocational programmes scored 382 points. The largest gap was in Serbia (85 score points) and the narrowest was in Albania (25 score points) (OECD, 2020[16]). There are many likely factors that contribute to this trend, such as the fact that in many systems, disadvantaged students tend to be overrepresented in VET secondary programmes and learning gaps are likely start earlier on in their schooling.

Strengthening the partnership with the private sector, especially in development of curricula, and providing opportunities for work-based learning will be key to improving the relevance of VET programmes. The majority of VET programmes in the region are outdated and lack economic relevance. In Kosovo, for example, an estimated 47% of VET students attend programmes for which there is very limited demand in the labour market (Mehmeti, Boshtraka and Mehmeti, 2019[53]). A tracer study of VET graduates in Bosnia and Herzegovina found that only 51% of graduates are employed in the field in which they studied (German Cooperation, 2018[54]).

Improving the quality and relevance of VET would require better financing of the VET system. Limited financing for VET – and the relatively high share of staff expenditures – leaves limited funds for equipment, technology and other relevant teaching materials. This results in mainly theoretical VET with limited practical learning. This challenge is exacerbated by the limited opportunities for work-based learning.

Attention also needs to be given to the workforce of vocational teachers. In particular, it is vital to ensure they are fully aware of recent developments in professional practice in their respective fields. With the exception of Serbia, share of teachers undertaking in-service training and participating in professional development in vocational specialisation is relatively low in the region. All regional economies are characterised by a relatively low share of teachers that undertook their CPD within businesses (Table 2.5), indicating their limited practical exposure. In Serbia and Montenegro, more than 20% of teachers of vocational subjects have no experience at all of working in the occupation for which they are training their students (ETF, 2018[41]).

Table 2.5. Vocational teachers participating in various forms of CPD (%)

% of teachers, 2014/15

|

In-service training |

Professional development in vocational specialisation |

Conferences/seminars |

Observation visits to schools |

CPD at businesses |

No CPD |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Albania |

56 |

23 |

17 |

31 |

29 |

35 |

|

Bosnia and Herzegovina |

54 |

32 |

13 |

15 |

32 |

40 |

|

Kosovo |

56 |

36 |

27 |

18 |

16 |

35 |

|

North Macedonia |

65 |

34 |

35 |

24 |

24 |

27 |

|

Montenegro |

76 |

40 |

37 |

19 |

27 |

21 |

|

Serbia |

92 |

54 |

35 |

38 |

31 |

4 |

|

Turkey |

47 |

37 |

47 |

30 |

49 |

19 |

Source: ETF (2017[55]), Torino Process 2016-2017: South Eastern Europe and Turkey, http://dx.doi.org/10.2816/341582.

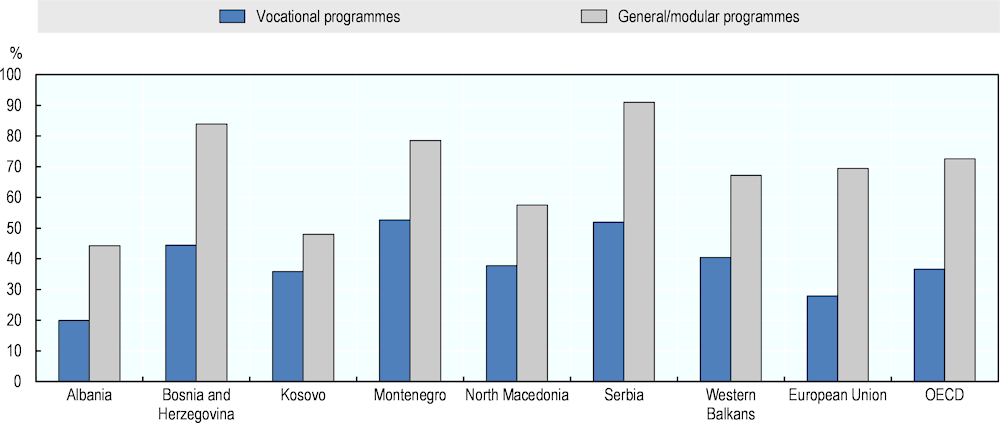

Managing pathways for tertiary education from the VET track is an important challenge in the region. A generation ago, upper-secondary VET systems in nearly all Western Balkan economies were designed to prepare individuals for one job for life. This has now changed: as the economies have modernised and come to require higher-level skills, the aspirations of young people for tertiary education has risen markedly (Field and Guez, 2018[56]). This has created profound challenges for upper-secondary VET tracks, in the Western Balkans as elsewhere: unless such tracks offer a clear route to tertiary education, they may be perceived as a dead-end. In 2018, 40% of Western Balkan students (on average) in upper-secondary VET tracks expected to complete a university degree, a slightly higher share than EU and OECD averages (Figure 2.9).

Figure 2.9. A large share of upper-secondary students are expecting to complete a university degree in the Western Balkans

Note: A university degree includes a bachelor's, master's or doctoral degree (ISCED 5A and 6).

All differences are statistically significant.

Source: OECD (2021[18]), PISA 2018 Database, www.oecd.org/pisa/data/.

Policy options for improving the quality and relevance of VET

Strengthening the quality of VET would require: upgrading and modernising the curricula and teaching methods to better align studies with labour market needs; improving teaching quality and, in particular, strengthening the practical education of teachers; expanding work-based learning opportunities; boosting resources for better equipment and teaching materials; and strengthening career guidance and counselling.

Develop more practice-oriented VET programmes by including employers in the design and implementation process. A recent review of VET in Albania provided some informative and detailed recommendations on how to systematise VET in response to labour market needs. Many of the recommendations would be applicable throughout the Western Balkans (Hilpert, 2020[57]).

Review and consolidate VET profiles in line with labour market developments and needs. The Business Higher Education Forum (BHEF) in the United States brings together senior administrators from higher education institutions and CEOs of Fortune 500 companies to identify skill needs and find ways to develop those skills within higher education. One strength of this collaboration is that it is a long-term partnership, allowing for deep research that informs longer-term curriculum development. The BHEF is currently working with higher education institutions and business partners to develop new curricula for projected in-demand fields of study such as cybersecurity and data analytics (OECD, 2017[58]).

Enhance funding to improve access to equipment and teaching materials to improve the quality of teaching.

Strengthen co-ordination mechanisms with the private sector to boost work-based learning through apprenticeships. Work-based learning has been identified as a key element of strong VET systems, as it offers both a powerful learning environment and a means of linking trainees and training to employers, aligning training provision to employer needs and facilitating subsequent recruitment (OECD, 2018[59]). Apprenticeship, in which more than half – and typically around 80% – of the VET programme takes place in the workplace, with the employer, is a strong model of work-based learning (OECD, 2014[60]). “Dual” vocational education normally refers to this model. Even when a vocational programme is predominantly school-based, there are compelling grounds for including a substantial element of work-based learning. In France, students in the three-year, upper-secondary vocational programme (baccalauréat professionnel) must pursue 22 weeks of work-based learning. Students can participate in up to six work placements, each being a minimum of three weeks. The relevant qualification standards define which competencies are to be acquired during these placements. Teaching staff together with employers define the practical aspects of the training period and determine the tasks the learner is required to carry out. Qualified mentors ensure learners are appropriately supported. Teaching staff evaluate the performance of students during the placements, which contributes to the overall mark in the baccalauréat professionnel (European Commission, 2013[61]).

Develop quality assurance for work-based learning that is not too burdensome for employers. Work placements are only valuable if they are good quality in terms of the work experience, training and mentoring offered by the employer. Quality assurance of work placements is therefore an important part of ensuring meaningful learning opportunities for students. However, employers will be reluctant to offer placements if the quality assurance requirements are burdensome for them. Thus, quality assurance needs to be designed to assist employers in offering work placements, rather than being an obstacle to them. The Swiss “Qualicarte”, developed for apprentices but with potential for wider application, provides a good model. Developed by employer bodies together with government training agencies, Qualicarte offers employers both a checklist of how to manage a trainee and a form for self-assessment. It thus guides employers through the tasks they need to perform in work-based learning and supports quality. For each of the evaluation criteria of the Qualicarte, training employers are invited to self-assess the extent to which they comply with expectations (CSFP, 2021[62]).

Foster flexibility within VET through modular courses or pathways that create bridges between upper secondary vocational and tertiary education, thereby better responding to the diverse needs of students. OECD countries grappling with this challenge have adopted different strategies, few of which are perfect. In Austria and Switzerland, a separate academic examination is required, over and above an apprenticeship qualification, to enter university (Apprenticeship Toolbox, 2021[63]). However, both countries have relatively high-status apprenticeship systems, which are potentially attractive to students even without a direct link to tertiary education. More relevant to the Western Balkans may be the common lesson from the different experiences of Sweden and Denmark, where the link between vocational programmes and access to tertiary education is critical to the attractiveness of vocational programmes, particularly for high-performing students. In Sweden up to 2011, students in upper-secondary vocational programmes automatically pursued the general education programmes that provide access to higher education. A 2011 reform meant that some more demanding general education programmes, including mathematics, became optional for those in vocational programmes. Subsequently, the proportion of students following vocational programmes dropped, from 53% in 2005-10 to 33% in 2016/17, with a particularly sharp fall in strong performers. Survey evidence suggests that many Swedes now see vocational programmes as an option for low performers, offering weak preparation for higher education. As a remedy, an OECD review proposed that, by default, vocational programmes should include the courses required for higher education, while allowing an opt-out. Denmark’s point of departure was different in that it has historically had a form of dual apprenticeship in upper-secondary education. However, having found it difficult to sustain the interest of young people in the apprenticeship track, Denmark recently created a hybrid qualification (EUX) that provides both an apprenticeship and access to higher education. These programmes are academically demanding and attract only a few percent of those in the vocational track. But they have been successful in attracting some high performers who might not have otherwise considered apprenticeship (Kuczera and Jeon, 2019[64]).

Boost resources for career guidance for VET students to improve employability and reduce drop-outs. Career guidance should be redesigned from assistance with individual career decisions to a lifelong learning approach that also encompasses the development of career management skills.

2.3.3. Increasing the use of digital technologies in education

Globally, digital tools have become an increasingly important part of schooling. Such tools include not only physical devices (e.g. computers and smartphones with internet access), but also involve use of technologies such as cloud storage, learning analytics and collaborative learning networks that allow for access by students, teachers and parents (van der Vlies, 2020[65]). Digital technology does not automatically improve outcomes and, in isolation, investment in computers for education appears to yield few benefits; however, when complemented by skilled teachers, digital tools can yield good results (OECD, 2015[66]).

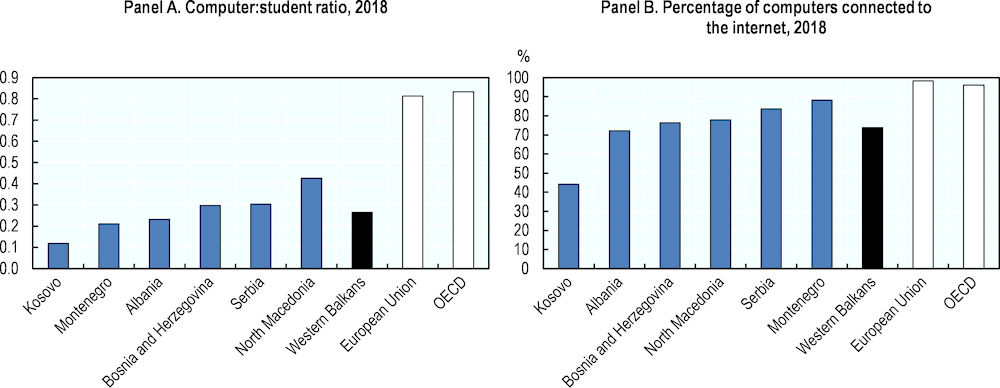

Access to digital resources varies hugely across schools in the Western Balkans. According to data from PISA, schools in the region attended by 15-year-olds have just over 0.25 computers per pupil, compared with an average of over 0.8 in OECD countries (OECD, 2020[16]). Even in North Macedonia, the best-provided economy in the region, this ratio was less than 0.5 (Figure 2.10 – Panel A). Internet access is also an issue: just over 70% of computers in schools in the Western Balkans are connected to the internet compared with nearly all school computers in OECD countries. In Kosovo, less than half of computers are connected to the internet (Figure 2.10 – Panel B).

The perceptions of principals confirm the weaknesses in technological infrastructure in Western Balkan schools. In a survey of principals carried out in 2018, respondents indicated that only a little more than one-third of pupils in Western Balkans schools had effective online support available and that the number of digital devices was sufficient; in both cases, comparable OECD and EU averages were more than half of pupils. Kosovo reports particular challenges, as principals reported that only 15% of pupils were in schools with sufficient digital devices (Table 2.6). These data tend to confirm that technological infrastructure is weak in the region and that school leaders perceive as a problem.

Figure 2.10. There is a need to increase the use of digital technology in schools

Source: OECD (2020[16]), Education in the Western Balkans: Findings from PISA, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/764847ff-en.

In response to the COVID-19 crisis and widespread school closures, Western Balkan economies moved rapidly to introduce distance learning through multiple routes. In some parts of the region, students received information and communications technology (ICT) equipment and classes were delivered on line, backed by web resources. TV and radio broadcast material was also used extensively to provide distance learning, although often in an abridged form. Teachers participated in online networking platforms to share experiences and support each other. Finally, the school calendar in many Western Balkan education systems was adjusted to protect public health (World Bank, 2020[67]).

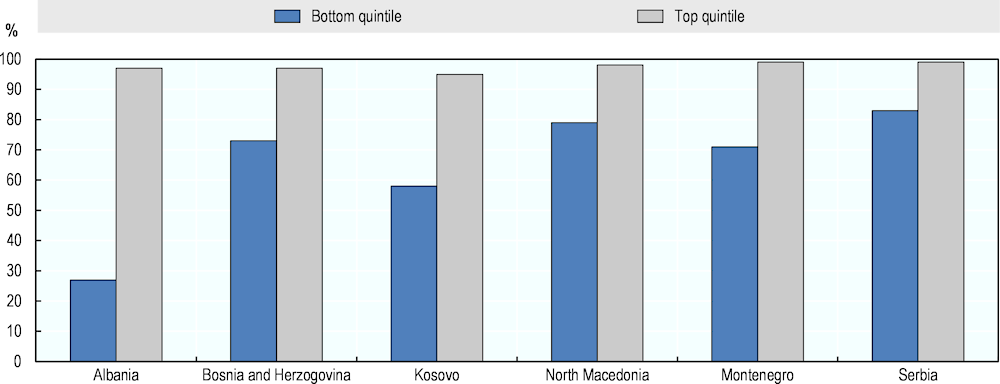

These developments revealed gaps in access to digital technology at home, not least as students in the Western Balkans often lack the connectivity enjoyed by their EU counterparts. Some 22% of students in the Western Balkans report little or no home internet access, double the level of EU countries (World Bank, 2020[67]). Moreover, the PISA Index of economic, social and cultural status (ESCS) shows that students in the region have almost universal access to the internet while those in the bottom quintile have much less (Figure 2.11). For children trying to work from home, parents can, in principle provide vital support, both in respect of the learning substance, and in handling the digital tools necessary to support home learning. However, this is likely to pose a challenges considering that the share of individuals with basic or above basic digital skills is relatively low in the region (Figure 2.3 – Panel A. Beyond the issue of digital tools, many students will have found the whole experience of disrupted schooling, alongside the wider impacts of the pandemic, profoundly disturbing; likely, they will need ongoing emotional support from their parents and their schools once schools reopen.

Table 2.6. How principals see digital resources in their schools

% of students in schools at which the principal “agreed” or “strongly agreed” with these statements, 2018

|

An effective online learning support platform is available |

The number of digital devices for instruction is sufficient |

The availability of adequate software is sufficient |

Teachers have the necessary technical and pedagogical skills to integrate digital devices in instruction |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Albania |

32 |

38 |

47 |

89 |

|

Bosnia and Herzegovina |

34 |

38 |

35 |

67 |

|

Kosovo |

22 |

15 |

17 |

72 |

|

Montenegro |

49 |

40 |

57 |

76 |

|

North Macedonia |

24 |

38 |

44 |

79 |

|

Serbia |

40 |

43 |

49 |

71 |

|

Western Balkans average |

34 |

35 |

41 |

76 |

|

EU average |

52 |

59 |

72 |

65 |

|

OECD average |

54 |

59 |

71 |

65 |

Source: OECD (2021[18]), PISA Database, www.oecd.org/pisa/data/.

Figure 2.11. In most of the Western Balkan economies, students’ background influences their access to digital technology

Source: World Bank (2020[67]), The Economic and Social Impact of COVID-19: Education, http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/590751590682058272/pdf/The-Economic-and-Social-Impact-of-COVID-19-Education.pdf

Weak digital skills among teachers may be one of the biggest challenges to effective online education in the Western Balkans. Weak digital skills among teachers seems to be a general challenge not only in the Western Balkans, but also in the European Union, where only one-quarter or less of students are taught by teachers who feel confident using digital technology (World Bank, 2020[67]). In Albania, North Macedonia and Serbia about 77%, 72.2% and 56% of teachers, respectively, report having a need for professional development in ICT-related fields (ETF, 2018[68]; ETF, 2018[69]; ETF, 2017[70]). Several Western Balkan economies now recognise the need for such skills among teachers. Serbia has a specific element of digital competency in the ITE curriculum; Montenegro and North Macedonia include digital skills among the professional standards of teacher competencies (World Bank, 2020[67]).

Policy options for increasing the use of digital technologies in the classroom

Limited teacher capacity and inadequate digital technology represent significant weaknesses in the Western Balkans. School closures during the pandemic and the use of online education platforms during closures has only highlighted this challenge. Looking ahead, as digital technologies continue to evolve, the region will need to upgrade both the digital infrastructure and the digital skills of teachers.

Boost teacher capacities to use digital tools. To make full use of digital technology in education, the most important investment – in both the short and long term – for all economies may lie in teacher capacity. This requires building the use of digital education tools as a key element in ITE, and, critically in CPD, to ensure teachers feel supported and have the capacity to use such tools in their practice. Education systems can then develop digital infrastructure in line with the increasing capacity of the teaching workforce to use digital tools. To ensure adequate take up of trainings on digital skills among teachers, there also seems to be a need to further raise the awareness among school principals. Among the school principals in the region, there is namely a strong perception that the necessary technical and pedagogical skills to integrate digital devices in instruction are available (Table 2.6). Latvia has brought the digital competency of teachers to the forefront of efforts for implementing curricular reform. Teachers can engage for free in professional development courses to enhance their digital skills in the e-environment for the use of educational technologies. The courses target a large variety of teachers and school leaders, from preschool to VET teachers and teachers of various subjects (e.g. languages, mathematics and biology). Teachers can engage with the content flexibly, at their own pace (Minea-Pic, 2020[71])

Increase student access to digital technologies in the classroom.

2.3.4. Updating and modernising curricula to impart relevant knowledge and skills

Curricula are powerful levers for strengthening student performance and well-being, and for preparing students for future jobs. Development of competence-based curricula is critical to ensure consistency and equity in the delivery of education and to target learning outcomes, skills and competencies that need to be achieved at each stage of the education process. Curricula can also guide and support teachers, facilitate communication between teachers and parents, and ensure continuity across different levels of education. However, curricula can also limit the creativity and agency of students and teachers if there is not sufficient space to explore their own interests and goals. To support innovation and progress, likewise, curricula need to be regularly updated and upgraded to keep pace with changing economies and societies (OECD, 2020[36]).

Competency-based curricula have been developed in the Western Balkans, but implementation is lagging. In most economies, the common challenge is that teachers and schools lack the competencies and/or support to implement competence-based curricula and adapt them to their needs. In Serbia, the new curriculum is overloaded and very prescriptive – compared with practices in OECD countries – which severely limits teachers’ room to adapt their practices to the specific learning needs of students (Maghnouj et al., 2019[32]). In addition, it lacks guidelines that describe students’ learning progression in a cycle. External school evaluation results show that, in almost half of basic education schools and two-thirds of upper-secondary schools, the use of assessment to inform learning and adapt teaching to student needs is weak (Petrović, Nedeljković and Nikolić, 2017[72]). In Bosnia and Herzegovina, the capacity challenge is further complicated by political sensitivities and disagreements, as well as the lack of political will to follow state-wide mandates, all of which hamper implementation of the competence-based curricula (World Bank, 2019[73]). In Kosovo, inadequate preparation and training of teachers impedes curricula implementation, as do delays in preparing accompanying materials, lack of updated textbooks and other issues (Aliu, 2019[74]).

Policy options for strengthening curricula in the Western Balkans

When it comes to the policy lever of curricula, the Western Balkan economies face multi-faceted challenges. First, they need to ensure implementation of the competence-based curricula is finalised and is consistent across all jurisdictions. Second, they need to ensure resources and mechanisms are in place to systematically update and upgrade curricula in line with changing labour market needs or socio-economic developments. This includes developing stronger co-ordination mechanisms across relevant institutions and stakeholders as well as ensuring that annual analyses of labour market needs are translated into proposals for education policy action. Specific policy actions include:

Advance adaptation of competence-based curricula across schools. To aid implementation, adequate support materials and teacher training need to be developed.

Strengthen co-ordination mechanisms with the private sector and other stakeholders to improve the labour-market relevance of curricula. Systematic review and updating of curricula are critical for keeping abreast with labour market or socio-economic changes. In Poland, higher education institutions partner with employers to design curricula and teaching processes. Vocational higher education institutions need to demonstrate substantial participation of employers and industry representatives in the educational process, for example by ensuring their representatives are present on the collegial advisory bodies of these institutions (OECD, 2017[58]).

Translate annual analyses of labour market needs into concrete proposals for enrolment policy and curricula improvements. A critical added value of such analyses is that they can guide changes and upgrades of curricula and relevant education policies.

Align assessment practices with the standards of the new curricula. This will influence the uptake of competence-based education and allow teachers and external assessments/exams to measure students against the new curricula’s norms.

2.3.5. Fostering equitable education at all levels