Despite important progress towards cleaner forms of energy, Bosnia and Herzegovina remains committed to a significant share of future electricity production from coal. Its enhanced Nationally Determined Contribution includes about 1 GW of new coal-fired power plants to be built by 2030. This chapter presents key policy priorities to ensure a green recovery for Bosnia and Herzegovina through the energy transition. A significant reduction in greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution requires the elimination of very high subsidies for coal-fired power and the development of a comprehensive strategy. Such a strategy must be backed by a legal and regulatory framework that is unified and harmonised at the state level, thereby replacing the current fragmentation between entities and cantons. Bosnia and Herzegovina needs stronger financial incentives and simplified administrative procedures for the deployment of intermittent renewables such as solar and wind, as well as for energy efficiency improvements in buildings. To integrate a growing share of intermittent wind and solar power into the electricity mix, transmission and distribution grids need to be upgraded to a higher level of flexibility. It is also essential that energy reforms be driven by domestic societal consensus and political will.

Multi-dimensional Review of the Western Balkans

16. A green recovery in Bosnia and Herzegovina

Abstract

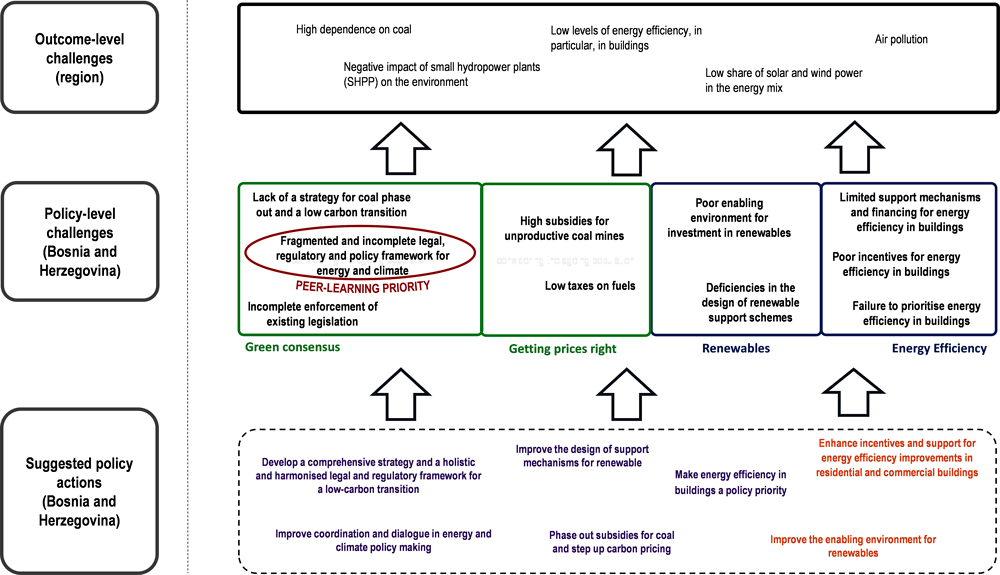

The Initial Assessment of the Multi-dimensional Review (MDR) of the Western Balkans identified a green recovery as a top policy priority for Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Western Balkan region as a whole. Energy and air pollution are complex challenges and significant obstacles to future economic development and well-being. Air pollution, unreliable access to clean energy and unsustainable environmental practices were identified as key constraints in Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Western Balkan region in the Initial Assessment. A high carbon-intensity in combination with low levels of energy efficiency results in considerable air pollution and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The share of solar and wind power in the energy mix remains low. Building on the initial assessment, the “From Analysis to Action” phase of the project provides policy suggestions to ensure a green recovery in Bosnia and Herzegovina and in the other Western Balkans economies. The peer-learning workshops on green recovery served three complementary aims: to identify problems hampering the green recovery; to identify key policy challenges; and to put forward key policy priorities for Bosnia and Herzegovina and for the region (Figure 16.1).

In recent years, Bosnia and Herzegovina has already taken various measures across several dimensions to support a green recovery. In preparation of the 26th Conference of Parties (COP26) of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in 2021, Bosnia and Herzegovina adopted an enhanced Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) including, most importantly, a more ambitious GHG emissions reduction target. In 2017, the Framework Energy Strategy of Bosnia and Herzegovina 2035 was adopted as the key strategic document for the energy sector. The strategy defines priorities for the energy sector and goals for clean technologies, energy efficiency and renewable energies. In addition, energy efficiency legislation is already in place in both Republika Srpska (RS) and the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (FBiH). Support schemes for energy efficiency improvements for households (residential buildings) and businesses (commercial properties) exist in the Canton of Tuzla and are planned for the Canton of Sarajevo. Energy efficiency funds have been established: the Environmental Protection Fund in FBiH and the Environmental Protection and Energy Efficiency Fund in RS.

To ensure a fully green recovery, Bosnia and Herzegovina must now tackle a set of important challenges that remain. At present, the legal, regulatory and policy framework for energy and climate remains incomplete; it is also fragmented across entities and cantons, and existing legislation is not always enforced. Energy and climate policy making in Bosnia and Herzegovina is not sufficiently inclusive; the government should take action to raise awareness and improve public consultations. Importantly, Bosnia and Herzegovina lacks a comprehensive strategy for replacing coal with cleaner alternatives. Subsidies for coal in the economy are the highest in the Western Balkan region even though the productivity levels of coalmines are low. Taxes on both diesel and petrol are also low in relation to international averages. An outdated electricity grid, an inflexible electricity system, and complex and cumbersome administrative procedures hamper investment in renewables and much scope exists to improve renewable support schemes. Policy efforts, support and financing for energy efficiency in buildings remain limited (Figure 16.1).

Figure 16.1. Towards a green recovery in Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Western Balkans

Note: Purple = policy actions based on priorities expressed by participants of the peer-learning workshop. Orange = policy actions suggested by the OECD.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on OECD green recovery peer-learning workshop.

Seven policy priorities have great potential to ensure a green recovery in Bosnia and Herzegovina, with the development of a comprehensive strategy, backed by a holistic and harmonised legal and regulatory framework, for a low-carbon transition being the key priority. These policy priorities reflect issues raised by participants from Bosnia and Herzegovina at the green recovery peer-learning workshop (Box 16.1):

Develop a comprehensive strategy, backed by a holistic and harmonised legal and regulatory framework, for a low-carbon transition (peer-learning priority)

Improve co-ordination and dialogue in energy and climate policy making

Phase out subsidies for coal and step-up carbon pricing

Improve the design of support mechanisms for renewables

Improve the enabling environment for renewables

Make energy efficiency in buildings a policy priority

Enhance incentives and support for energy efficiency improvements in residential and commercial buildings

Box 16.1. Outcomes of the green recovery peer-learning workshop – Bosnia and Herzegovina

Participants from Bosnia and Herzegovina (representing government, the private sector and civil society) at the OECD green recovery peer-learning workshop identified the development, adoption and implementation of an appropriate legal framework for energy and climate as the top priority for the economy. They suggested an action plan that could complement current policy efforts including, more specifically, four actions with corresponding monitoring indicators and measures (Table 16.1).

Table 16.1. Development, adoption and implementation of a legal framework for energy and climate

Action plan, monitoring indicators and measures

|

Actions |

Monitoring indicators and measures |

|---|---|

|

Action 1: Establish implementation and monitoring mechanisms |

|

|

Action 2: Revise supporting schemes for renewable energy sources |

|

|

Action 3: Organise of public consultations |

|

|

Action 4: Ensure consequences in case of non-implementation of existing rules |

|

Source: OECD peer-learning workshops.

To advance towards the overarching goals, peer-learning participants stressed that Bosnia and Herzegovina needs a National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP) that defines a clear strategy for phasing out coal – rather than construction of new coal-fired power plants. They also emphasised the importance of including a financing strategy and pilot projects in this NECP. In turn, they raised the need to revise renewable support schemes, including defining different schemes for large- and small-scale renewables and renewable quotas. To determine how much energy is produced from renewables, Bosnia and Herzegovina also needs a regional system of guarantees of origin. The government could also make better use of international treaties and the Energy Community.

According to peer-learning participants, prioritising implementation of existing energy and climate legislation is critical. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, this implies the need for impartial courts, for less politics and more expertise in the development of energy sector legislation, for improved monitoring, for depoliticising public energy companies and for ensuring that environmental inspections are properly carried out.

Finally, participants stressed the importance of raising public awareness on energy and climate policies and ensuring inclusion of all relevant stakeholders in energy and climate policymaking. Improved awareness raising requires finding ways to stop the spread of misinformation (e.g. “coal is cheap” may reflect its price but fails to capture its societal costs) and more competition in the media sector. Improved public consultation is needed to enhance co-ordination and collaboration among government institutions, the private sector and civil society. Awareness rising and more inclusive energy and climate policymaking are particularly important in the context of developing Bosnia and Herzegovina’s NECP.

Source: OECD peer-learning workshops.

This chapter is divided into eight sections. Sections 16.1 through to 16.7 provide policy implications across the seven priorities through a prism of challenges specific to Bosnia and Herzegovina. Section 16.8 provides indicators against which progress in policy implementation in Bosnia and Herzegovina can be measured. This chapter is complemented by the regional chapter (Chapter 14), which provides more specific policy options for the priorities based on international practice that may be applied, with necessary adaptations, also to Bosnia and Herzegovina.

16.1. Develop a comprehensive strategy, backed up with a holistic and harmonised legal and regulatory framework for a low-carbon transition in Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnia and Herzegovina recently adopted a more ambitious emissions reduction target but does not envision coal phase out. In April 2021, Bosnia and Herzegovina submitted its enhanced NDC under the Paris Agreement to the UNFCCC, which is more ambitious than the first NDC. It pledges to reduce GHG emissions by 33.2% to 36.8% by 2030 and by 61.7% to 65.6% by 2050 (compared with 1990 levels). Emissions reduction efforts focus on power, district heating, buildings, industry, transport, forestry, agriculture and waste. Bosnia and Herzegovina’s enhanced NDC also foresees adding new wind, solar, biomass and hydro capacity by 2030. However, Bosnia and Herzegovina’s enhanced NDC also encompasses the construction of 1 050 MW of new coal-fired TPPs until 2030 (UNDP Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2021[1]; UNFCCC, 2021[2]). Establishing a GHG inventory and a GHG reporting, monitoring and verification mechanism will be key for measuring progress towards meeting the enhanced NDC. At present, Bosnia and Herzegovina is finalising a GHG inventory for 2015-2016 and a GHG reporting, monitoring and verification mechanism is under development.

To comply with the Sofia Declaration and to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050, Bosnia and Herzegovina requires a comprehensive strategy for phasing out coal. In November 2020, Bosnia and Herzegovina signed the Sofia Declaration and committed to align its own goals with the EU’s energy transition and climate neutrality target for 2050 (see Box 14.5 of Chapter 14). However, in 2019 62.7% of electricity in Bosnia and Herzegovina was generated from coal. The key strategic document for the energy sector – the Framework Energy Strategy of Bosnia and Herzegovina 20351 – as well as Bosnia and Herzegovina’s enhanced NDC aim to maintain and even expand reliance on coal for electricity generation. Currently, several new coal-fired thermal power plants (TPPs) are being constructed in Bosnia and Herzegovina: cogeneration units in TPP Tuzla (Block 7 with a capacity of 450 megawatts [MW]) and in TPP Kakanj (Block 8, 300-350 MW) and a replacement block in TPP Gacko (Block 2, 350 MW). Preparations are ongoing for construction of three additional coal-fired TPPs: Banovići (350 MW); Ugljevik 3 (600 MW); and Kamengrad (350 MW)2 (Energy Community Secretariat, 2020[3]; European Commission, 2020[4]).

Replacing coal with cleaner technologies requires a reliable solution for producing baseload power to ensure a stable electricity supply. Electricity generation from coal currently secures a stable energy supply for Bosnia and Herzegovina. Proposed construction of new coal TPPs aims to increase security of energy supply.

To improve energy and climate policymaking in Bosnia and Herzegovina, state-level competencies should be strengthened, along with the co-ordinating function of state-level institutions. Lack of a holistic approach to energy, climate and environmental policymaking is one of the biggest obstacles to a low-carbon energy transition in Bosnia and Herzegovina. At present, each entity has primary responsibility for these policy areas. In FBiH, the competency for energy, climate and environmental policy making is further divided between federal and cantonal authorities. At the state level, the Division for Natural Resources, Energy and Environment within Bosnia and Herzegovina’s Ministry of Foreign Trade and Economic Relations holds overall responsibility for energy, climate and environmental policymaking, but its competencies are limited to defining general principles, co-ordinating activities, and harmonising plans of entity institutions. Strengthening state-level competencies would allow for avoiding overlapping policy measures, plans and other strategic documents, and for the effective implementation economy-wide strategies (Knežević et al., 2019[5]).

Bosnia and Herzegovina’s legal and regulatory framework for a low-carbon transition requires harmonisation and streamlining across entities. As a result of the division of competencies for energy and climate policymaking, the relevant legislative and regulatory framework is fragmented, inconsistent and lacks harmony across entities (European Commission, 2020[4]). Laws and regulations differ among FBiH, RS and Brcko District. In turn, strategic documents – such as renewable energy and energy efficiency action plans – are often passed at both the state and entity levels. Similarly, priority areas, goals and strategic objectives are not always harmonised. This fragmented policy framework prevents Bosnia and Herzegovina from implementing policies in accordance with the Energy Community Treaty – and ultimately from meeting its international obligations. The Framework Energy Strategy of Bosnia and Herzegovina 2035 aims to harmonise energy and climate legislation both at the entity level and with the acquis communautaire (Ministry of Foreign Trade and Economic Relations of Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2017[6]). However, little progress has been made so far.

Bosnia and Herzegovina should finalise and adopt its NECP. Through its NECP 2021-2030, Bosnia and Herzegovina aims to define goals for energy efficiency, renewables and reducing GHG emissions, as well as to streamline climate and energy policies and align them with EU policies. The government has launched seven thematic working groups, including representatives from the government, the private sector, academia, civil society and donors, to develop the NECP3 and has created a federal energy model and complementary entity energy models. A first draft of Bosnia and Herzegovina’s NECP was submitted to the Energy Community Secretariat for review in November 2020. Bosnia and Herzegovina is currently in the process of defining targets for different NECP dimensions. In parallel, entity-level Energy and Climate Plans are being developed. Both, Bosnia and Herzegovina’s NECP at the state-level and entity-level Energy and Climate Plans are planned to be adopted by the end of 2022. However, the legal basis for the adoption of the state-level NECP and entity-level Energy and Climate Plans has never been defined (Brnjoš, 2021[7]; Energy Community Secretariat, 2021[8]; Energy Community Secretariat, 2020[3]). Once Bosnia and Herzegovina’s NECP has been adopted, the NDC will need to be updated and aligned with the targets set out in the NECP.

Building a broad consensus and strong political will are key ingredients for a successful green recovery. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, energy and climate reforms are often largely driven by international organisations and partners, rather than by a strong political will and a broad public consensus (UNECE, 2018[9]). This often means policies are adopted but not implemented, or remain mere formalities with little actual impact.

Existing legislation and commitments need to be fully enforced in Bosnia and Herzegovina. As a result of Bosnia and Herzegovina’s complex constitutional structure, enforcement (or lack thereof) of existing legislation is an even larger challenge than in other Western Balkan economies. Many deadlines for the transposition and implementation of the acquis communautaire have already expired. The Energy Community Secretariat has initiated eight proceedings against Bosnia and Herzegovina for breach of contractual obligations in all areas of the Energy Community Treaty, including environmental protection, electricity, state aid, energy efficiency, gas, sulphur content in fuels, and failure to transpose the provisions of the Third Energy Package (Bljesak.info, 2021[10]). For example, Bosnia and Herzegovina adopted a National Emissions Reduction Plan (NERP) 2018-2027 but is not complying with its ceilings for sulphur dioxide (SO2), dust (particulate matter or PM) and nitrogen oxide (NOX) emissions (Energy Community Secretariat, 2020[3]; Energy Community Secretariat, 2021[11]; USAID BiH, 2015[12]).

Adopting and regularly updating strategic documents on energy and climate is important. Bosnia and Herzegovina’s Climate Change Adaptation and Low Emissions Growth Strategy 2025 (published in 2013), aims to implement (at the state level) adaptation measures to increase resilience to climate variability and long-term climate change (Radusin et al., 2013[13]). Bosnia and Herzegovina is planning to adopt an updated version of the Climate Change Adaptation and Low Emissions Growth Strategy 2030 in 2022; a draft has already been finalised. The National Renewable Energy Action Plan (NREAP) 2020 (published in 2016) defines (at the state level) renewable targets and renewable energy policy measures (Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2016[14]). The National Energy Efficiency Action Plan 2016–2018 (NEEAP) (published in 2017) sets goals (at the state level) for energy savings (Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2017[15]). Work on a new NEEAP 2019-2021 has largely been completed but the document had not yet been adopted at the time of writing. At the entity level, FBiH has already adopted its NEEAP for 2019-2021 whereas the adoption of the NEEAP for 2019-2021 is still pending in RS. The NEEAP 2019‑2021 and the NREAP 2020 will be replaced by the NECP once it has been adopted. Bosnia and Herzegovina is currently in the process of drafting an Environmental Strategy and Action Plan 2030+ (at the state level), covering water, waste, biodiversity and nature conservation, air quality, climate change and energy, chemical safety and noise, resource management and environmental management. This document aims to improve environmental quality and the health of citizens and future generations (SEI, 2022[16]). The Third National Communication and Second Biennial Update Report on Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Bosnia and Herzegovina under the UNFCCC were adopted in 2017 and submitted to the UNFCCC Secretariat (UNDP, 2017[17]).

Bosnia and Herzegovina should fully enforce regulatory impact assessments and consider harmonising them across entities. Regulatory impact assessments critically assess the positive and negative effects of proposed and existing regulations and non-regulatory alternatives. They are an important element of evidence-based policy making and for preparing Western Balkan economies’ accession to the European Union (OECD, 2021[18]). Regulatory impact assessments are in place in Bosnia and Herzegovina, at both the state level (since 2005) and the entity level (in RS since 2006 and in FBiH since 2014). However, they largely remain a mere formality or part of pilot projects and lack political support. Over two-thirds of the laws adopted between 2010 and 2014 in Bosnia and Herzegovina did not undergo regulatory impact assessments; for the remaining laws, regulatory impact assessments did not show positive effects on law enforcement. Finally, regulatory impact assessments differ across entities and civil servants lack awareness and knowledge on them (Ramić, 2019[19]).

Higher sanctions for non-compliance with environmental permits and other environmental offences could reduce violations of permit conditions and environmental misconduct. At present, sanctions following the violation of permit conditions by environmental permit holders (e.g. for air emissions, waste, water and forest felling) range from EUR 500 to EUR 5 000 in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Often, this relatively low amount means permit holders prefer to pay sanctions rather than invest in technology required to meet environmental standards (UNECE, 2018[9]). Further, no specific sanctions exist for the unregulated incineration of waste, especially of plastic, waste tires and agricultural waste – another problem present throughout Bosnia and Herzegovina.

16.2. Improve co-ordination and dialogue in energy and climate policy making

Designing sound green recovery policies requires greater co-operation and co-ordination with civil society and business associations and among institutions in energy and climate policy making in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Co-operation and co-ordination needs to be improved in energy and climate policy making, implementation and monitoring. Civil society organisations (CSOs) in Bosnia and Herzegovina are mainly active in awareness raising and education on energy, climate and environmental issues and policies; their participation in relevant policy design and development is limited. Neither CSOs nor private sector representatives do participate in meetings of the Inter-Entity Coordination Body for the Environment, an entity responsible for coordination of all environmental matters which require concerted efforts of the entities. Further, CSOs are not represented on the supervisory boards of the entity environmental funds. They do not receive any financial support from environmental authorities at the entity level (UNECE, 2018[9]; GIZ, 2017[20]).

Public consultations should be organised earlier in the process of drafting and adopting climate and energy legislation and the effectiveness of public consultations should be ensured. Public consultations can raise awareness of the need for a green recovery and ultimately improve the quality of regulations and laws, as well as enhance the transparency, efficiency and effectiveness of regulations. By improving public acceptance of laws and regulations, they facilitate enforcement and implementation (OECD, 2011[21]). In 2016, the Council of Ministers of Bosnia and Herzegovina adopted the Rules for Consultations in the Drafting of Legal Regulations (Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2017[22]), which stipulate that draft regulations and laws – including those related to energy, climate and environment – must undergo public consultations through the web application eKonsultacije before they can be formally adopted. The public can submit written comments on draft regulations and laws through this website. In praxis, however, as public consultations are open only at the end of the drafting process – i.e. shortly before laws and regulations are adopted – public suggestions and comments are often not taken into account. In most cases, public consultations remain mere formalities and rarely prompt changes before laws and regulations are adopted. More effort is required to raise public awareness of public consultations. In turn, capacity building is required at all levels of government on how to regularly use public consultations as a tool for policymaking (European Commission, 2020[4]).

Bosnia and Herzegovina can draw useful examples on transparency reform from other countries. In Estonia, public consultations take place at an earlier stage of the development of new laws and regulations. All steps in the legislative process conducted by the government and parliament are public and Estonian citizens can track online from the initiation of a legislative proposal to the official publication of a regulation in the State Gazette. A range of online tools engage stakeholders in regulation making and support the accessibility of regulations, including an online list of laws to be prepared, modified, reformed or repealed. The Electronic Coordination System for Draft Legislation (EIS) comprises an interactive website for public consultations and an online version of the official State Gazette. It allows any citizen to follow the development of a draft legal act, search for documents in the system and give their opinion on the documents open for public consultation (OECD, 2016[23]).

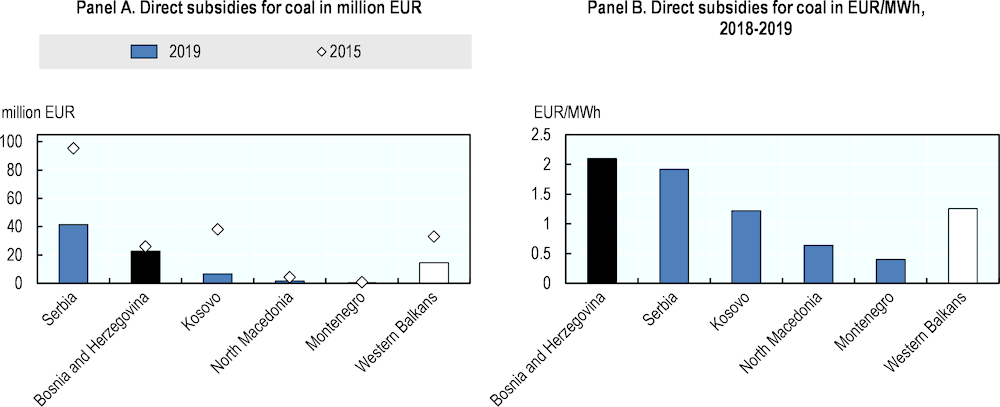

16.3. Phase out subsidies for coal and step up carbon pricing

Going forward, it would be important to start phasing out subsidies for coal in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Local coal mines supply much of the fuel for coal-fired TPPs; many have low productivity levels and depend heavily on subsidies. In 2015, average productivity was 553 tons of coal per full-time employee (t/FTE) in FBiH and 3 144 t/FTE in RS compared with 4 416 t/FTE as the EU average. At EUR 2.1 per megawatt hour (/MWh), subsidies for coal in Bosnia and Herzegovina are the highest in the region (Figure 16.2). The government’s total coal subsidy bill amounted to EUR 22.7 million in 2019 (0.11% of GDP), only a slight decrease from EUR 26 million in 2015. Over the period 2015 to 2019, total coal subsidies amounted to EUR 167.6 million (EUR 33.5 million annually on average) (Miljević, 2020[24]). In addition to direct subsidies for coalmines, Bosnia and Herzegovina indirectly subsidises coal through non-payment of CO2 emissions fees by coal-fired TPPs. In 2017 alone, coal-fired TPPs were exempted from paying EUR 177.5 million in CO2 emissions compensation.4 Between 2015 and 2017, indirect subsidies amounted to EUR 231.6 million or EUR 26.08/MWh (Miljević, Mumović and Kopač, 2019[25]).

Figure 16.2. Subsidies for coal in Bosnia and Herzegovina are among the highest in the Western Balkan region

Source: Miljevic (2020[24]), Investments into the past - An analysis of Direct Subsidies to Coal and Lignite Electricity Production in the Energy Community Contracting Parties 2018–2019, https://www.energy-community.org/dam/jcr:482f1098-0853-422b-be93-2ba7cf222453/Miljevi%C4%87_Coal_Report_122020.pdf.

Electricity prices that reflect production costs would encourage energy savings and improve public finances. Subsidies for coal in Bosnia and Herzegovina result in electricity prices that do not reflect production costs. In 2018, electricity prices were EUR 74.40/MWh for households and EUR 65.30/MWh for industry.5 The practice of charging low prices for electricity means financial resources for energy infrastructure maintenance and development are scarce. Furthermore, low prices do not encourage investment in renewables and energy efficiency measures in buildings to save electricity.

To reduce the negative socio-economic impact of coal mine closures on miners and coal-dependent regions, it is important to compensate miners who become unemployed through retraining programmes and the creation of new jobs that match their skill sets (see Section 14.2.4 of Chapter 14) (Szpor, 2021[26]; Szpor, 2018[27]). For decades, coal mining has been an important segment of Bosnia and Herzegovina’s energy sector and played an important role its economic structure. In 2015, coalmines employed 13 731 workers while an even larger number of people, including families of miners, depended indirectly on coal mining.6 Phasing out coal for electricity generation would result in mine closures and a significant number of jobless miners. Creating new economic pathways for these regions will require taking these factors into account and creating new professional development opportunities for jobless coalminers, with retraining playing an important role. The European Commission’s Initiative for Coal Regions in Transition in the Western Balkans and Ukraine (see Chapter 14, Section 14.2.4.) and the EBRD’s just transition initiative7 could play an important role in this process, for example, through peer exchanges with other countries in the region and trainings for re-skilling and up-skilling of coal workers. In addition, the World Bank’s is supporting Bosnia and Herzegovina through the elaboration of a Roadmap for the transition of coal-rich regions in Bosnia and Herzegovina in collaboration with the state- and entity-level ministries of energy.

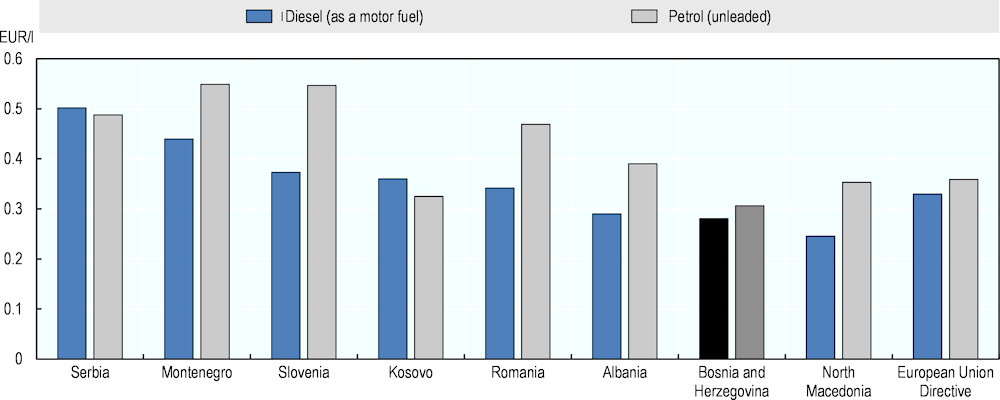

Bosnia and Herzegovina should consider increasing excise taxes on fuels. At present, Bosnia and Herzegovina has among the lowest excise taxes on both diesel (EUR 0.28 per litre [/l]) and petrol (EUR 0.31/l) in the Western Balkan region, both of which are below the minimum prescribed (EUR 0.33/l) by the EU Energy Taxation Directive (Figure 16.3). As noted, the excise tax on diesel is lower than on petrol, even though diesel is more polluting (World Bank, 2020[28]). Increasing excise taxes on fuels would reduce pollution while also generating additional resources for investment in low-carbon technologies. Reflecting the importance that EU countries give to carbon taxation, Germany introduced (in January 2021) a carbon tax equal to EUR 25 per megatonne of carbon dioxide (/Mt CO2) for the transport and heating sectors (i.e. covering petrol, diesel, heavy fuel oil and natural gas). From 2026, auctions will replace the fixed price within a price corridor set at EUR 55 to EUR 65/Mt CO2 (Franke, 2020[29]).

Figure 16.3. Excise taxes on fuels in Bosnia and Herzegovina are among the lowest in the Western Balkan region

Source: World Bank (2020[28]), Environmental Tax Reform in North Macedonia, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/34679.

Poor households should be compensated for higher electricity and fuel prices. Subsidies for coal and fuel, which lead to low electricity and fuel prices, serve as indirect income support for households. However, they are highly inefficient as a measure for poverty reduction since most of the benefits go to higher income households that use more energy. Poor households could be compensated for higher electricity prices through targeted, income-based support, such as social benefits or vouchers for a monthly allowance of electricity consumption. Subsidies for energy efficiency improvements, such as low-carbon heating technologies and insulation of residential buildings, could reduce actual energy consumption of poor households – and thus lower their electricity bills (OECD, 2021[30]).

16.4. Improve the design of support mechanisms for renewables in Bosnia and Herzegovina

Scaling up modern renewable energy technologies such as wind and solar power – as opposed to traditional sources such as fuel wood – is important to a green recovery for Bosnia and Herzegovina. In 2019, renewables and biofuels accounted for 37% of electricity generation in Bosnia and Herzegovina and for 37.6% of gross final energy consumption (Eurostat, 2021[31]). However, biomass (most importantly fuel wood for heating and cooking) accounts for a large share of renewables in gross final energy consumption (Energy Community Secretariat, 2021[11]). Hydropower accounted for 95.5% of electricity from renewables while wind power accounts for only 3.9% and solar power for 0.5% (Eurostat, 2021[31]). Large hydropower (over 10 MW of installed capacity) accounts for 74% of installed hydropower capacity, small hydropower plants (SHPPs, up to 10 MW) for 7.2% and pumped storage for 18.8% (Energy Community Secretariat, 2021[11]). Only one wind farm operates in FBiH; to date, RS has none (CEE Bankwatch Network, 2019[32]).

Shifting to market-based support mechanisms for renewables in Bosnia and Herzegovina could enhance efficiency. At present, renewables are supported in Bosnia and Herzegovina by FiTs, which have been administratively set for 12 (FBiH) or 15 (RS) years. Throughout this period, priority producers are guaranteed a fixed price for electricity they produce (Ministry of Foreign Trade and Economic Relations of Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2016[33]). In addition, RS uses fixed feed-in premiums (FiPs) allocated through auctions for renewables, which are also guaranteed for 15 years but require that producers find buyers on the market. The eligibility for FiTs varies by entity: solar plants (up to 1 MW), biomass and biogas power plants and wind farms are eligible in FbiH. With the entry into force of RS’s new Law on Renewable Energy Sources, SHPPs, ground-mounted solar power plants and wind farms (up to 150 kW) and rooftop solar, biomass and biogas power plants (up to 500 kW) are eligible in RS (CEE Bankwatch Network, 2019[32]). All renewable power plants with a larger capacity up to 50 MW can benefit from FiPs in RS. In addition, renewable energy communities or energy cooperatives can also benefit from FiPs even with an installed capacity below 150 kW in RS (Balkan Green Energy News, 2022[34]).

Bosnia and Herzegovina is in the process of preparing the introduction of renewable auctions. Renewable auctions are expected to result in lower purchase prices of electricity from renewables and could enhance transparency and efficiency in the selection process of suppliers of renewable energy. FiTs could be maintained for small-scale renewable installations. A renewable quota requiring electricity suppliers to buy a certain amount of electricity generated from renewables could help create a market (Ministry of Foreign Trade and Economic Relations of Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2017[6]).

Effective net-billing schemes for renewable self-consumers are needed in Bosnia and Herzegovina. At present, only RS has a net-metering scheme for self-consumers, which applies only to installations up to 50 kilowatts (kW) (FBIH has no such scheme). To date, only one self-consumer is registered in RS (Energy Community Secretariat, 2021[11]).

A more sustainable financing mechanism for renewable support schemes is needed. Currently, FiTs and FiPs in Bosnia and Herzegovina are financed through a levy for each kWh of electricity consumed, which is collected from consumers through their monthly electricity bills (BAM 0.001976/kWh in FBiH and BAM 0.0044/kWh in RS – the equivalent of BAM 1.00 to BAM 2.00 per month per household). Between 2015 and 2019, the collection of these levies amounted to EUR 62 million – an amount insufficient to fully finance FiTs. At the same time, political acceptance of the levy is low (Harbaš, 2017[35]; Ministry of Foreign Trade and Economic Relations of Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2016[36]). Market-based support mechanisms, such as auctions or FiPs, would increase competition thereby reducing prices and the amount of public financial resources required for subsidies.

Scope exists to increase the transparency of renewable support schemes in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Information on the allocation of FiTs (e.g. names of applicants and quota winners) as well as dynamic quotas (maximum level of installed capacity of different types of renewables supported through FiTs annually) are not available on the official government website (European Commission, 2020[4]). In FBiH, the body running the renewables support scheme (Operator za obnovljive izvore energije i efikasnu kogeneraciju [OIEiEK]) did not grant federal auditors access to the documentation required for a performance audit in 2019, for which the government banned the institution from making payments to renewables for several months. Support schemes for renewables are complex and lack transparency, particularly in FBiH (CEE Bankwatch Network, 2021[37]).

The planning, monitoring and evaluation of SHPPs in Bosnia and Herzegovina should be improved. In 2019, at least 110 SHPPs were operating in Bosnia and Herzegovina (37 in RS; 63 in FBiH) but they accounted for only 3.1% of electricity generation (CEE Bankwatch Network, 2019[32]; CEE Bankwatch Network, 2021[37]). Existing SHPPs are known to negatively affect ecosystems and biodiversity as they alter the flow of rivers, reduce fish populations (e.g. complete extinction of fish in the Ugar River) and sometimes result in river flows drying up completely. Environmental impact assessments (EIAs) prepared for construction permits of SHPPs are often deficient and entity and cantonal environmental authorities often fail to intervene even if they are aware of environmental damage by SHPPs (Ministry of Foreign Trade and Economic Relations of Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2016[36]; UNECE, 2018[9]).

Bosnia and Herzegovina should consider phasing out remaining subsidies for SHPPs. In 2017, SHPPs received the largest share (81%) of subsidies for renewables in Bosnia and Herzegovina, to the detriment of other renewables such as wind power and solar energy (CEE Bankwatch Network, 2019[32]). FBiH suspended FiTs for SHPPs starting from 1 January 2021, redirecting the financial resources available to other renewable energy sources (Aarhus Center Association in Bosnia and Heregovina, 2020[38]; European Commission, 2020[4]; Spasić, 2020[39]). However, SHPPs can still sell the electricity they produce at a reference price 20% above the market price in FBiH; as such, they still benefit from an indirect subsidy (CEE Bankwatch Network, 2019[32]). Subsidies for SHPPs remain in place in RS.

16.5. Improve the enabling environment for renewables in Bosnia and Herzegovina

Harmonising and unifying fragmented strategic and legal frameworks would be important to promote renewables in Bosnia and Herzegovina. While the Framework Energy Strategy 2035 defines strategic priorities for renewable energies (Ministry of Foreign Trade and Economic Relations of Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2017[6]),8 Bosnia and Herzegovina does not have a law on renewable energies at the state level. Rather, support schemes are defined at the entity level through the Law on the Use of Renewable Energy Sources and Efficient Cogeneration of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Law on Renewable Energy Sources and Efficient Cogeneration of Republika Srpska and a new Law on Renewable Energy Sources in Republika Srpska, adopted in February 2022 (Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2014[40]; Republika Srpska, 2015[41]; Republika Srpska, 2013[42]). A draft Law on Renewable Energy Sources is currently also being prepared in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Renewable energy action plans exist at both state and entity levels (Federal Ministry of Energy, Mining and Industry, 2014[43]; Republika Srpska, 2014[44]). Still, this fragmented legal framework hampers systematic planning and the development of a comprehensive strategy to scale up renewable energies. Adoption of action plans and strategic documents is time-consuming and deadlines are often missed.

Simplifying administrative procedures could facilitate investment in renewables in Bosnia and Herzegovina. A complex administrative apparatus represents a barrier to investment in renewables across the economy. The process of issuing authorisations, permits and licenses for renewables – for both large-scale installations and self-consumers – continues to be bureaucratic, time-consuming and unpredictable. The process involves numerous institutions, many different steps and a large amount of documentation. A lack of vertical and horizontal communication among different levels of government exacerbates the challenges already identified. The large discretionary power of administrative bodies results in investors having to respond to numerous requests to submit “additional documentation”, leading to even further delays. Simplifying administrative processes could promote more investment in renewables (European Commission, 2020[4]; USAID, 2015[45]). For this purpose, RS and FBiH already adopted reports with recommendations on improving administrative procedures and removing regulatory and non-regulatory barriers to the development of renewable energies9 in 2018 and the implementation of the recommendations has started with the support of USAID.

Enhancing transparency and improving access to information on licensing and permitting processes for renewables is important. At present, the authorisation and licensing processes differ across entities, cantons and regions – and sometimes even between officials within the same institution. Investors often find it difficult to access information on procedures, documentation required and institutions involved. Many self-consumers who want to install solar panels opt to pay a third party who has previously gone through the process to help them obtain the necessary licenses and permits (European Commission, 2020[4]; USAID, 2015[45]). In order to improve transparency on the investment process, Bosnia and Herzegovina adopted Guidelines for Investors in the Electricity Sector, elaborated with the support of USAID, in 2018, which include information on the investment procedure for renewables, required permits and the competent authorities (USAID, 2021[46]).

To integrate significant wind and solar power in the electricity mix, transmission and distribution (T&D) grids in Bosnia and Herzegovina need to be adapted, expanded, modernised and upgraded. Wind and solar power are intermittent: the amount of electricity generated varies depending on the time of the day and from one day to another. In turn, wind and solar power plants are often located far away from the main centres of electricity consumption, requiring transmission over long distances before distribution. A third challenge is that electricity from distributed, decentralised home solar systems needs to be integrated to the distribution grid. Bosnia and Herzegovina’s T&D grid was conceived for a relatively stable supply of electricity generated from centralised hydro and thermal power plants. Transmission lines in areas with high potential for wind and solar power (mainly in the south) to the main centres of consumption are not sufficiently developed (Energy Community Secretariat, 2021[11]). Bosnia and Herzegovina also needs to invest in management optimisation, installation of supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) systems, and the development of smart metering.

Modernising Bosnia and Herzegovina’s electricity grid requires an adequate institutional and regulatory environment. Strengthening the institutional set-up is a prerequisite to facilitate modernising and upgrading the T&D grid: production and distribution of electricity are not yet separated and both roles are performed by the same SOEs. Market efficiency remains a challenge as Bosnia and Herzegovina does not yet have a day-ahead electricity market and prices remain regulated (Energy Community Secretariat, 2021[11]).

Bosnia and Herzegovina requires a more flexible electricity system to integrate more renewables in its electricity mix. In September 2020, the State Electricity Regulatory Commission of Bosnia and Herzegovina (SERC) increased the maximum capacity of wind and solar power plants that may be connected to the transmission network (from 460 MW to 840 MW for wind; from 400 MW to 825 MW for solar) (Energy Community Secretariat, 2020[3]). Integrating a larger share of variable renewables in the electricity mix requires making the system itself more flexible through better regional interconnection, storage facilities and integration of a larger amount of flexible generation technologies (e.g. flexible biomass, natural gas). A significant amount of pumped storage already exists in Bosnia and Herzegovina (420 MW) and the economy is well interconnected with the power systems of other countries in Southeast Europe. In the case of Bosnia and Herzegovina, optimal use of existing pumped storage hydropower facilities is vital to system flexibility; investing in additional pumped storage may be wise (Kušljugić, 2019[47]).

Raising awareness of the benefits of renewables and improving renewable support mechanisms could trigger more private investment in renewables. Citizen awareness of the benefits of renewables, as well as renewable energy policies and incentive schemes, remains low in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Many citizens are unaware that they pay levies for renewables through their monthly energy bills and increases in these levies are often overlooked. Communication about renewable energies by the media, independent experts and academia remains insufficient. Improved public awareness could enhance support for renewable policies and projects (Harbaš, 2017[35]). Raising awareness and informing electricity consumers about renewables through informational-motivational public campaigns is one of the strategic priorities of Bosnia and Herzegovina’s Framework Energy Strategy 2035 is (Ministry of Foreign Trade and Economic Relations of Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2017[48]).

16.6. Make energy efficiency in buildings a policy priority in Bosnia and Herzegovina

As the basis for energy efficiency improvements, Bosnia and Herzegovina should finalise its legislative framework for energy efficiency. Both FBiH and RS have adopted energy efficiency laws (Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2017[49]; Republika Srpska, 2015[50]; Republika Srpska, 2013[51]). However, the transposition of the EU Energy Efficiency Directive (EED) and the Energy Labelling Regulation remains incomplete across entities, and the adoption of the draft Energy Efficiency Law in Brčko District is pending. The transposition of regulations on eco-design and energy labelling has been initiated with the technical support of the EBRD’s Regional Energy Efficiency Programme for the Western Balkans (REEP Plus). Bosnia and Herzegovina has finalised but not yet adopted a draft Building Renovation Strategy up to 2050, including four scenarios representing different levels of ambition for building renovation in Bosnia and Herzegovina. At the entity level, RS has adopted a long-term building renovation strategy, while the FBiH strategy remains at the draft stage. Bosnia and Herzegovina is also in the process of designing an energy efficiency obligation scheme10 (a draft exits since 2015) but has not yet adopted any relevant secondary legislation (including a specific target and policy measures) (Energy Community Secretariat, 2020[3]; USAID, 2020[52]). In June 2019, Bosnia and Herzegovina adopted a decision on the establishment of the Energy Management System and Energy Efficiency Information System in central government buildings.

Accelerating implementation of existing legislation on energy efficiency is vital. Bosnia and Herzegovina submitted its third annual energy efficiency report to the Energy Community Secretariat in July 2019, which indicates limited progress in implementing existing legislation (Energy Community Secretariat, 2020[3]). In both FBiH and RS, energy efficiency laws foresee the inclusion of related criteria in public procurement processes of goods and services and in the construction of buildings. However, these criteria are not always applied in practice.11

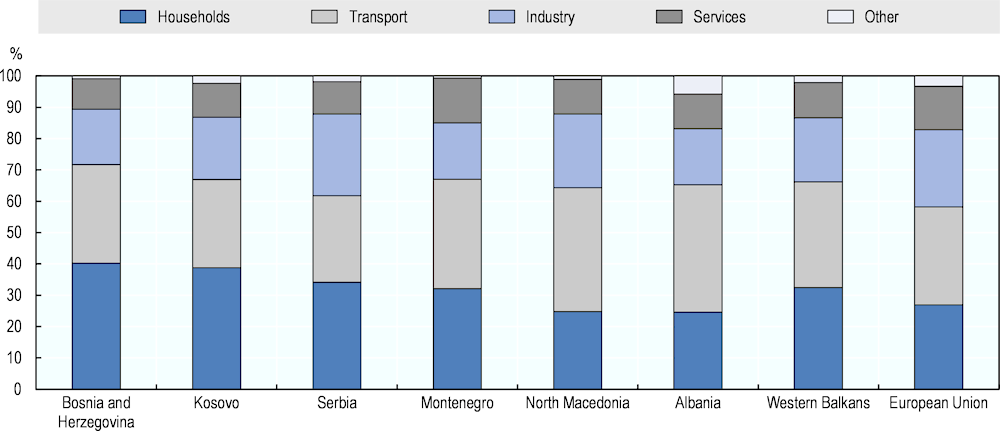

16.7. Improve incentives and support for energy efficiency improvements in residential and commercial buildings

Most buildings in Bosnia and Herzegovina are outdated and have low levels of energy efficiency. Many buildings were built at times of relatively low energy prices and without taking into account energy efficiency criteria (Harbaš, 2017[53]; UNECE, 2018[9]). Comparing public and residential buildings located in similar climate conditions, on average, those in Bosnia and Herzegovina consume more than five times as much energy as those in EU countries. Close to 20% of Bosnia and Herzegovina’s GDP is spent on energy, compared to just 4.75% as the EU average (USAID BiH, 2021[54]). Annual energy consumption for heating in Bosnia and Herzegovina range from 160 kilowatt hours per square meter (kWh/m2) to 180 kWh/m2 (Harbaš, 2017[53]). The share of households in final energy consumption in Bosnia and Herzegovina (40.2%) is the highest in the Western Balkan region (average of 32.4%) and much higher than the EU average of 26.9% (Eurostat, 2021[31]).

A reduction of heating based on fuel wood in inefficient devices could enhance energy efficiency in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Overall, more than 70% of households do not have central heating systems and rely on inefficient, mainly fuel-wood based devices for heating (Agencija za statistiku Bosne i Hercegovine, 2018[55]). In 2018, the share of renewables and waste (mainly fuel wood) in heating (82.2%) in Bosnia and Herzegovina was the second-highest in the Western Balkan region, following Kosovo; it is far above average (61.4%) for the region and almost triple the EU average (27%) (2018) (Eurostat, 2021[31]) (see Figure 14.8 of Chapter 14). The use of fuel wood for heating is higher in RS than in FBiH and Brcko District (Center for ecology and energy, CEE, 2016[56]).

Figure 16.4. Households account for a larger share of final energy consumption in Bosnia and Herzegovina than in other economies in the Western Balkan region and in the EU

Expansion of district heating, in combination with the decarbonisation and modernisation of district heating systems, could improve energy efficiency. Derived heat accounts for 7.5% of heating in Bosnia and Herzegovina (Eurostat, 2021[31]), with about 12% of households connected to district heating systems. Close to half of existing district heating systems are fired by coal and lignite; natural gas accounts for more than 30% and biomass for close to 25% (the latter is the highest share among Western Balkan economies) (Energy Community Secretariat, 2021[11]). At present, consumption-based billing is not applied in most district heating systems (USAID, 2020[52]). While Bosnia and Herzegovina is relatively advanced in the use of biomass for district heating, much scope remains for replacing coal-fired district heating plants with cleaner alternatives, and for modernising and upgrading existing district heating systems.

A large number of households and businesses in Bosnia and Herzegovina require financial support for implementation of energy efficiency measures in residential and commercial buildings. To date, most energy efficiency measures for buildings in Bosnia and Herzegovina have focused on public buildings, with many programmes having been financed by international donors. Subsidies for households and businesses for energy efficiency improvements in residential and commercial buildings exist in the Canton of Tuzla and are planned in the Canton of Sarajevo. Tuzla subsidises investments up to EUR 2 500 for energy efficiency improvements in residential and commercial buildings (e.g. to replace coal-fired boilers with heat pumps) and up to 50% of renewable energies for self-consumption. To benefit from subsidies, owners of buildings are required to have an energy audit carried out. In 2020, 125 applicants met the requirements to benefit from these subsidies. In January 2021, in the Canton of Sarajevo, the cantonal Ministry of Physical Planning, Construction and Environmental Protection and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in Bosnia and Herzegovina launched a similar programme. For households in Sarajevo, the scheme will subsidise up to 70% of the total cost of replacing coal stoves and boilers with certified furnaces and boilers and up to 40% of the total cost of heat pumps (UNDP Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2021[57]). Several other donor-funded programmes support energy efficiency improvements in residential buildings.

Low levels of income and limited access to financing are key obstacles to scale up energy efficiency improvements in residential buildings in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Even when subsidies are available (as in the programmes in Tuzla and Sarajevo), households often experience difficulties in financing their share of the overall cost. A lack of financing mechanisms and high interest rates on bank loans hinder private sector investments in energy efficiency (UNECE, 2018[9]). Generally, funding for energy efficiency for households and businesses is available mainly from international financial institutions (IFIs) such as the European Investment Bank (EIB) and other EU development funds, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), the German Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau (KfW) and the World Bank. Such funding is generally made available to borrowers through local financial institutions (Kušljugić, 2019[58]; Raiffaisen BANK, 2021[59]; USAID, 2021[60]).

Better access to financing for energy efficiency improvements in buildings is vital. Mobilising private financing through local communities, energy co-operatives and small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) will be very important to scale up energy efficiency improvements (Kušljugić, 2019[58]). Energy Service Companies (ESCOs) could also play an important role in financing energy efficiency improvements (see Chapter 14, Section 14.4.3). As part of its Development Strategy (2021-2027), FBiH plans to provide funding support to foster the development of energy service company markets. In June 2021, Bosnia and Herzegovina further adopted the Framework for Financing Energy Efficiency Projects and Measures for Investments in Public Buildings, which could facilitate access to financing for energy efficiency measures in public buildings.

To improve access to financing, the budgetary resources of energy efficiency funds should be increased. Energy efficiency funds exist both in FBiH (the Environmental Protection Fund) and in RS (the Environmental Protection and Energy Efficiency Fund); however, the financial resources available to these funds are limited. In RS, the Environmental Protection and Energy Efficiency Fund is financed through 10% of the levy for stimulating renewable electricity production and efficient cogeneration, which is collected through electricity bills, and from fees collected for environmental protection (USAID, 2020[52]). RS’s Environmental Protection and Energy Efficiency Fund further relies on donor funding: the fund signed several joint programmes with UNDP and the EBRD for energy efficiency improvements in public facilities between 2017 and 2022 (EBRD, 2022[61]; UNDP, 2017[62]). Budgets for these energy efficiency funds could be increased by raising levies charged via electricity bills in RS and introducing such levies in FBiH – a measure that would simultaneously provide incentives to save energy. Raising or introducing levies (in RS and FBiH respectively) on energy is likely to be more politically acceptable than increasing the value-added tax (VAT) or income taxes. Under its Law on Charges for Usage of Public Goods, Serbia introduced energy efficiency levies through electricity and gas bills as well as on gasoline (EUR 0.000127/kWh of electricity and EUR 0.00127 per cubic meter of natural gas and per litre of gasoline). Revenues collected are allocated to Serbia’s energy efficiency fund (Balkan Green Energy News, 2019[63]).

Improved incentives could encourage more energy efficiency improvements in multi-apartment buildings. Bosnia and Herzegovina has the highest share of multi-apartment buildings in the Western Balkan region (46% of the residential building stock) (Energy Community Secretariat, 2021[64]). Management, maintenance and renovations of such buildings are regulated at the entity level in RS and at the cantonal level in the FBiH, with legislative and regulatory frameworks differing significantly not only between the entities but also across cantons within FBiH. Additionally, homeowner associations are recognised as legal entities in RS but not in FBiH and challenges linked to collective decision making hamper energy efficiency improvements in both cases. Major renovation works of common parts, including energy efficiency improvements, require the consent of all homeowners rather than a 50%+1 majority vote. Lack of technical support to address deficiencies in older multi-apartment buildings and complicated administrative procedures for renovation works are additional challenges. Reforming the legislative and regulatory framework for multi-apartment buildings has not been a policy priority in Bosnia and Herzegovina but needs to become one. All stakeholders – including apartment owners – should be involved in the reform process (USAID, 2020[52]).

Better access to financing for homeowner associations could facilitate more energy efficiency improvements in multi-apartment buildings. Difficult access to financing for energy efficiency improvements and the lack of reserve funds for both maintenance and investment in such improvements are important challenges in multi-apartment buildings. Generally, fees collected by homeowner associations for maintenance remain very limited and reserve funds are small. As homeowner associations are recognised as legal entities in RS, the banking sector started developing basic loan products for them; FBiH lags in this regard. Still, banks perceive homeowner associations as excessively risky in Bosnia and Herzegovina, which curtails realising their market potential. There is a need to educate and support local banks in developing loan products for homeowner associations. Possible solutions are: collecting additional fees from homeowners specifically for renovation works; providing loan guarantees and partial government grants to homeowner associations for energy efficiency improvements; and establishing budgetary funds at entity and local levels to finance grants and loan guarantees (USAID, 2020[52]).

16.8. Indicators to monitor the overall policy progress in Bosnia and Herzegovina

To monitor progress in implementing policies for a green recovery in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the OECD suggests a set of key indicators, including values for Bosnia and Herzegovina and benchmark countries (either the OECD or the EU average, based on data availability, and Croatia for the number of renewable self-consumers per 100 000 population) (Table 16.2).

Table 16.2. Indicators to monitor progress in implementing policies in Bosnia and Herzegovina

2019, unless otherwise specified

|

Indicator |

2019 |

Benchmark value |

|---|---|---|

|

CO2 emissions per capita (tons per capita) |

**6.81 |

**7.64a |

|

CO2 emissions per unit of GDP (kg/USD 2015 PPP) |

**0.5059 |

**0.1867a |

|

Mean exposure to PM 2.5 air pollution (µg/m3) |

30.30 |

13.90a |

|

Years of life lost (YLL) per 100 000 inhabitants attributable to exposure to PM2.5 pollution |

*****1 381 |

*****1 074b |

|

Subsidies for coal (EUR/MWh) |

2.10 |

N/A |

|

Market share of the largest generator in the electricity market (% of total electricity generation) |

37.30 |

44.79b |

|

Renewables (% of electricity generation) |

36.95 |

34.94b |

|

Solar and wind (% of electricity generation) |

1.62 |

17.66b |

|

Renewables self-consumers per 100 000 population |

*0.03 |

**36.93c |

|

Space heating using renewables and waste (fuelwood) (% of total) |

***82.20 |

***27.00b |

|

Transformation and distribution losses (% of primary energy consumption) |

36.63 |

22.92b |

Note: *2021, **2020, ***2018, ****2017, *****2016 . aOECD, bEU, cCroatia.

Source: Eurostat (2021[31]), Eurostat (database), https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/; IEA (2021[65]), Data and statistics, www.iea.org/data-and-statistics; EEA (2019[66]), Air quality in Europe — 2019 report, www.eea.europa.eu/publications/air-quality-in-europe-2019; Energy Community Secretariat (2021), www.energy-community.org/regionalinitiatives/WB6/Tracker.html; Miljevic (2020[24]), Investments into the past, https://energy-community.org/dam/jcr:482f1098-0853-422b-be93-2ba7cf222453/Miljevi%25C4%2587_Coal_Report_122020.pdf; Miljević, Mumović, Kopač (2019[25]), Analysis of Direct and Selected Indirect Subsidies to Coal Electricity Production in the Energy Community Contracting Parties, https://www.energy-community.org/dam/jcr:ae19ba53-5066-4705-a274-0be106486d73/Draft_Miljevic_Coal_subsidies_032019.pdf; Slok, M. (2021[67]), Incentives and challenges in promoting self-consumption - The case of Croatia, www.energy-community.org/; World Bank (2021[68]), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators.

References

[38] Aarhus Center Association in Bosnia and Heregovina (2020), “Globalni poziv i borba aktivista za zaštitu posljednjih evropskih divljih rijeka urodili plodom: FBiH ukida subvencije za male hidroelektrane od 2021. Godine”, http://www.aarhus.ba/sarajevo/en/1476-globalni-poziv-i-borba-aktivista-za-zastitu-posljednjih-evropskih-divljih-rijeka-urodili-plodom-fbih-ukida-subvencije-za-male-hidroelektrane-od-2021-godine.html (accessed on 31 March 2021).

[55] Agencija za statistiku Bosne i Hercegovine (2018), Anketa o potrošnji domaćinstva u Bosni i Hercegovini 2015, Agencija za statistiku Bosne i Hercegovine, Sarajevo, https://bhas.gov.ba/data/Publikacije/Bilteni/2018/CIS_01_2015_Y1_0_BS.pdf.

[34] Balkan Green Energy News (2022), Republic of Srpska adopts new law on renewable energy sources, Balkan Green Energy News, Belgrade, https://balkangreenenergynews.com/republic-of-srpska-adopts-new-law-on-renewable-energy-sources/ (accessed on 13 October 2021).

[63] Balkan Green Energy News (2019), Serbia introduces energy efficiency fee on gas, electricity, fuel, Balkan Green Energy News, Belgrade, https://balkangreenenergynews.com/serbia-introduces-energy-efficiency-fee-on-gas-electricity-fuel/ (accessed on 13 October 2021).

[10] Bljesak.info (2021), Energy system reform - The last chance for the energy future of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bljesak.info, Mostar, https://www.bljesak.info/gospodarstvo/industrija/Zadnja-prilika-za-energetsku-buducnost-BiH/340510 (accessed on 13 October 2021).

[22] Bosnia and Herzegovina (2017), Rules for Consultations in the Drafting of Legal Regulations.

[7] Brnjoš, T. (2021), News, https://ba.ekapija.com/news/3228698/energetska-buducnost-zapadnog-balkana-je-u-dekarbonizaciji-drzave-postavile-ciljeve-prioritet-solarne (accessed on 13 October 2021).

[37] CEE Bankwatch Network (2021), Renewable energy incentives in the Western Balkans, CEE Bankwatch Network, Prague, https://bankwatch.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/2021-01-29_RenewableEnergyIncentives_WesternBalkans_2021.pdf.

[32] CEE Bankwatch Network (2019), Western Balkans hydropower - Who pays, who profits?, CEE Bankwatch Network, Prague, https://bankwatch.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/who-pays-who-profits.pdf.

[56] Center for ecology and energy, CEE (2016), Overview of the National Situation Regarding Energy Poverty In Bosnia and Herzegovina.

[61] EBRD (2022), EBRD and EU promote energy efficiency in Bosnia and Herzegovina, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, https://www.ebrd.com/news/2022/ebrd-and-eu-promote-energy-efficiency-in-bosnia-and-herzegovina.html (accessed on 13 October 2021).

[69] EBRD (2022), The EBRD’s just transition initiative, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, https://www.ebrd.com/what-we-do/just-transition-initiative (accessed on 13 October 2021).

[66] EEA (2019), Air quality in Europe — 2019 report, European Environment Agency, http://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/air-quality-in-europe-2019.

[8] Energy Community Secretariat (2021), Annual Implementation Report, Energy Community Secretariat, Vienna, Austria, https://www.energy-community.org/implementation/IR2021.html (accessed on 13 October 2021).

[64] Energy Community Secretariat (2021), Riding the renovation wave in the Western Balkans, Energy Community Secretariat, Vienna, Austria, https://www.energy-community.org/news/Energy-Community-News/2021/02/25.html.

[11] Energy Community Secretariat (2021), WB6 Energy Transition Tracker, Energy Community Secretariat, Vienna, Austria, https://www.energy-community.org/regionalinitiatives/WB6/Tracker.html.

[3] Energy Community Secretariat (2020), Annual Implementation Report, Energy Community Secretariat, Vienna, Austria, https://www.energy-community.org/implementation/IR2020.html (accessed on 24 June 2021).

[4] European Commission (2020), Bosnia and Herzegovina 2020 Report, European Commission, Brussels.

[31] Eurostat (2021), Eurostat (database), European Statistical Office, Luxembourg City, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/ (accessed on 13 October 2021).

[43] Federal Ministry of Energy, Mining and Industry (2014), Action Plan of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina for the Use of Renewable Energy Sources, http://operatoroieiek.ba/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/APOEF.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2021).

[49] Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (2017), Law on Energy Efficiency of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Official Gazette of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Sarajevo.

[40] Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (2014), Law on the Use of Renewable Energy Sources and Efficient Cogeneration of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Official Gazette of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Sarajevo, http://extwprlegs1.fao.org/docs/pdf/bih149390.pdf.

[29] Franke, A. (2020), Germany agrees Eur25/mt start to CO2 tax for transport, heating, S&P Global, New York, https://www.spglobal.com/platts/en/market-insights/latest-news/electric-power/052020-germany-agrees-eur25mt-start-to-co2-tax-for-transport-heating (accessed on 13 October 2021).

[20] GIZ (2017), National Assessment of Biodiversity Information Management and Reporting Baseline for Bosnia And Herzegovina, https://www.giz.de/en/downloads_els/ORFBDU_Assessment_BiH.pdf.

[53] Harbaš, N. (2017), Energy efficiency in Bosnia and Herzegovina: Opportunity or obligation?, Balkan Green Energy News, Belgrade, https://balkangreenenergynews.com/energy-efficiency-bosnia-herzegovina-opportunity-obligation/ (accessed on 13 October 2021).

[35] Harbaš, N. (2017), Renewable sources of energy in Bosnia and Herzegovina: Issue of (un)sustainability, Balkan Green Energy News, Belgrade, https://balkangreenenergynews.com/renewable-sources-of-energy-in-bosnia-and-herzegovina-issue-of-unsustainability/ (accessed on 13 October 2021).

[65] IEA (2021), Data and statistics, (database), International Energy Agency, Paris, https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/.

[5] Knežević, A. et al. (2019), Energy and Climate Policy of Bosnia and Herzegovina until 2030, Heinrich Böll Stiftung, Sarajevo, http://www.reic.org.ba/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Position-Paper-1.pdf.

[58] Kušljugić, M. (2019), Energy transition in Bosnia and Herzegovina - analysis of the situation, opportunities and challenges, NERDA Development Association.

[47] Kušljugić, M. (2019), NERDA Tuzla, https://www.nerda.ba/pdf/Energetska_tranzicija_u_BiH_tehnicki_aspekt.pdf.

[24] Miljević, D. (2020), Investments into the past: An analysis of Direct Subsidies to Coal and Lignite Electricity Production in the Energy Community Contracting Parties 2018–2019, Energy Community Secretariat, https://energy-community.org/dam/jcr:482f1098-0853-422b-be93-2ba7cf222453/Miljevi%25C4%2587_Coal_Report_122020.pdf.

[25] Miljević, D., M. Mumović and J. Kopač (2019), Analysis of Direct and Selected Indirect Subsidies to Coal Electricity Production in the Energy Community Contracting Parties, Energy Community, https://www.energy-community.org/dam/jcr:ae19ba53-5066-4705-a274-0be106486d73/Draft_Miljevic_Coal_subsidies_032019.pdf.

[70] Ministry of Foreign Trade and Economic Relations of Bosnia and Herzegovina (2020), Fourth Annual Report under the Energy Efficiency Directive, Energy Community Secretariat, Vienna, Austria, https://www.energy-community.org/dam/jcr:85df90e4-fcb0-45a5-a1c8-bbaef35e2aed/BiH_4thEED%20_AR_082020.pdf.

[48] Ministry of Foreign Trade and Economic Relations of Bosnia and Herzegovina (2017), Energy Efficiency Action Plan of Bosnia and Herzegovina for the period 2016 – 2018, Ministry of Foreign Trade and Economic Relations of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Sarajevo.

[6] Ministry of Foreign Trade and Economic Relations of Bosnia and Herzegovina (2017), Framework Energy Strategy of Bosnia and Herzegovina until 2035, Ministry of Foreign Trade and Economic Relations of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Sarajevo.

[33] Ministry of Foreign Trade and Economic Relations of Bosnia and Herzegovina (2016), National Renewable Energy Action Plan (NREAP BiH), Ministry of Foreign Trade and Economic Relations of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Sarajevo, http://www.mvteo.gov.ba/Content/Read/energetika-strateski-dokumenti?lang=en (accessed on 1 April 2021).

[36] Ministry of Foreign Trade and Economic Relations of Bosnia and Herzegovina (2016), Strategy and Action Plan for the Protection of Biological Diversity of Bosnia and Herezgovina, Ministry of Foreign Trade and Economic Relations of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Sarajevo, https://www.cbd.int/doc/world/ba/ba-nbsap-v2-en.pdf (accessed on 31 March 2021).

[18] OECD (2021), Regulatory impact analysis, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/regreform/regulatory-policy/ria.htm (accessed on 13 October 2021).

[30] OECD (2021), Taxing Energy Use for Sustainable Development, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/tax/tax-policy/taxing-energy-use-for-sustainable-development.pdf.

[23] OECD (2016), Pilot database on stakeholder engagement practices in regulatory policy, OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/measuring-regulatory-performance.htm (accessed on 13 October 2021).

[21] OECD (2011), Regulatory Consultation: A MENA-OECD Practitioners’ Guide for Engaging Stakeholders in the Rule-Making Process, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/mena/governance/MENA-Practitioners-Guide-%20EN.pdf.

[13] Radusin, S. et al. (2013), Climate Change Adaptation and Low Emission Development Strategy for Bosnia and Herzegovina.

[59] Raiffaisen BANK (2021), Raiffeisen BANK, https://raiffeisenbank.ba/stanovnistvo/krediti-za-energetsku-efikasnost.

[19] Ramić, L. (2019), Regulatory Impact Assessment in Bosnia and Herzegovina - Reality or Myth?, Inicijativa za monitoring evropskih integracija BiH, Sarajevo, https://eu-monitoring.ba/procjena-ucinaka-propisa-u-bosni-i-hercegovini-stvarnost-ili-mit/ (accessed on 13 October 2021).

[15] Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (2017), Energy Efficiency Action Plan of Bosnia and Herzegovina for the Period 2016 - 2018, Government of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, https://www.energy-community.org/dam/jcr:d5da6e89-291c-4e97-b978-85804d98d040/BIH_NEEAP_2016_2018_042017.pdf.

[14] Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (2016), National Renewable Energy Action Plan of Bosnia and Herzegovina (NREAP BIH).

[50] Republika Srpska (2015), Law on Energy Efficiency of Republika Srpska.

[41] Republika Srpska (2015), Law on Renewable Energy Sources and Efficient Cogeneration of the Republika Srpska.

[44] Republika Srpska (2014), Action Plan for the Use of Renewable Energy Sources.

[51] Republika Srpska (2013), Law on Energy Efficiency of Republika Srpska.

[42] Republika Srpska (2013), Law on Renewable Energy Sources and Efficient Cogeneration of the Republika Srpska.

[16] SEI (2022), Development of the Environmental Strategy and Action Plan of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Stockholm Environment Insitute, Stockholm, https://www.sei.org/projects-and-tools/projects/bosnia-herzegovina-environmental-policy/ (accessed on 13 October 2021).

[67] Slok, M. (2021), Incentives and challenges in promoting self-consumption - The case of Croatia, https://www.energy-community.org/ (accessed on 20 January 2022).

[39] Spasić, V. (2020), Federacija BiH od 2021. ukida subvencije za male hidroelektrane, Balkan Green Energy News, Belgrade, https://balkangreenenergynews.com/rs/federacija-bih-od-2021-ukida-subvencije-za-male-hidroelektrane/ (accessed on 13 October 2021).

[26] Szpor, A. (2021), Coal transition in Poland.

[27] Szpor, A. (2018), Public policies for restructuring the coal sector - Polish case study, https://ibs.org.pl/en/.

[62] UNDP (2017), Joint cooperation on energy efficiency projects continues with the Environmental Protection and Energy Efficiency Fund of Republika Srpska, United Nations Development Programme, New York, https://www.ba.undp.org/content/bosnia_and_herzegovina/en/home/presscenter/articles/2017/06/16/nastavak-zajedni-ke-saradnje-sa-fondom-za-za-titu-ivotne-sredine-i-energetsku-efikasnost-republike-srpske-na-projektima-energetske-efikasnosti-.html (accessed on 13 October 2021).

[17] UNDP (2017), Third National Communication (TNC) and Second Biennial Update Report on Greenhouse Gas Emissions (SBUR) of Bosnia and Herzegovina, United Nations Development Programme, New York, https://www.ba.undp.org/content/bosnia_and_herzegovina/en/home/library/environment_energy/tre_i-nacionalni-izvjetaj-bih.html (accessed on 13 October 2021).

[1] UNDP Bosnia and Herzegovina (2021), Bosnia and Herzegovina releases new climate pledge under Paris Agreement, United Nations Development Programme, New York, https://www.ba.undp.org/content/bosnia_and_herzegovina/en/home/presscenter/articles/2021/NDCBiH.html (accessed on 13 October 2021).

[57] UNDP Bosnia and Herzegovina (2021), Javni poziv za subvencioniranje zamjene peći/kotlova na ugalj i ostala čvrsta goriva certificiranim pećima/kotlovima i toplotnim pumpama u domaćinstvima u Kantonu Sarajevo, United Nations Development Programme, New York, https://www.ba.undp.org/content/bosnia_and_herzegovina/bs/home/presscenter/vijesti/2020/javni-poziv-za-subvencioniranje-zamjene-pei-kotlova-na-ugalj-i-o.html (accessed on 30 March 2021).

[9] UNECE (2018), Bosnia and Herzegovina Environmental Performance Reviews, United Nations Economic Comission for Europe, Geneva, https://unece.org/environment-policy/publications/3rd-environmental-performance-review-bosnia-and-herzegovina (accessed on 13 October 2021).

[2] UNFCCC (2021), Nationally Determined Contribution of Bosnia and Herzegovina (NDC) for the Period 2020 - 2030, United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, Bonn, https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/ndcstaging/PublishedDocuments/Bosnia%20and%20Herzegovina%20First/NDC%20BiH_November%202020%20FINAL%20DRAFT%2005%20Nov%20ENG%20LR.pdf.

[60] USAID (2021), Energy Sector Assistance Project in Bosnia and Herzegovina, United States Agency for International Development, Washington, DC.

[46] USAID (2021), Guidelines for Investors in the Electricity Sector of BiH, United States Agency for International Development, Washington, DC, https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00W52X.pdf.

[52] USAID (2020), Gap analysis of the housing sector in western balkan countries: Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, North Macedonia, and Serbia vs. Slovak Republic, United States Agency for International Development, Washington, DC.

[45] USAID (2015), Report on the licensing regime and barriers to investment in energy infrastructure projects in Bosnia and Herzegovina, United States Agency for International Development, Washington, DC.

[54] USAID BiH (2021), Energy Efficiency in Bosnia and Herzegovina, United States Agency for International Development, Washington, DC, https://www.usaideia.ba/en/activities/energy-efficiency/energy-efficiency-in-bosnia-and-herzegovina/ (accessed on 13 October 2021).

[12] USAID BiH (2015), National Emission Reduction Plan – NERP, United States Agency for International Development, Washington, DC.

[68] World Bank (2021), World Development Indicators (database), https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed on 24 June 2021).

[28] World Bank (2020), Environmental Tax Reform in North Macedonia, World Bank, Washington, DC, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/34679.

Notes

← 1. The Framework Energy Strategy of Bosnia and Herzegovina 2035 is the key strategic document for the energy sector. It defines strategic priorities and goals for clean technologies, energy efficiency and renewable energies, as well as strategic priorities and guidelines for the electricity sector, the coal sector, renewable energies, oil and petroleum products, gas, district heating and energy efficiency (Ministry of Foreign Trade and Economic Relations of Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2017[6]).

← 2. These investments are realised by a state-owned enterprise (SOEs) in collaboration with private companies from Bosnia and Herzegovina and China. Construction of Block 7 of TPP Tuzla is subject to an infringement procedure by the Energy Community Secretariat because the FBiH issued a public loan guarantee to secure a loan from China’s Exim Bank, thereby violating European Union (EU) state aid rules (Energy Community Secretariat, 2020[3]; European Commission, 2020[4]).

← 3. On reducing GHG emissions, while improving energy efficiency, boosting renewable energies, enhancing energy security, and advancing with the internal energy market and research, innovation and competitiveness.

← 4. Assuming a carbon price of EUR 20/t CO2 (Miljević, Mumović and Kopač, 2019[25]).

← 5. Information from fact-finding in Bosnia and Herzegovina from expert consultants from CENER21.

← 6. Information from fact-finding in Bosnia and Herzegovina from expert consultants from CENER21.

← 7. The EBRD’s just transition initiative aims to ensure the benefits of a green economy transition are shared, while protecting vulnerable countries, regions and people from falling behind. Investment and policy activities by the EBRD that can accelerate a just transition focus on a green economy transition, supporting workers and regional economic development (EBRD, 2022[69]).

← 8. Most importantly: a review of renewable energy fees charged to consumers, the introduction of market-based support mechanisms for large-scale renewable facilities (FiPs, auctions), the use of FiTs only for small-scale renewable installations, the introduction of net-billing for renewable self-consumers and facilitating the connection of renewables to the distribution grid (Ministry of Foreign Trade and Economic Relations of Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2017[6]).

← 9. Analysis of Legal Framework and Recommendations for the Removal of Obstacles to Investments in the Energy Sector in the FBIH and Analysis of Legal Framework and Recommendations for the Removal of Obstacles to Investments in the Energy Sector in the RS.