The passenger transport service sector is the second-largest contributor to tourism revenues in Tunisia. This chapter provides an overview of a selection of road passenger transport services and transport equipment rental services that are closely linked to tourism. Service exclusivity clauses for tourist transport and complex licensing requirements for other passenger transport such as taxis and other for-hire vehicles pose challenges to competition and business growth. Discrepancies between regulations create scope for grandfather clauses, favouring older firms and hampering the establishment of new ones. The absence of an adequate regulatory framework for disruptive innovation in road transport is causing market distortions affecting service quality and consumer welfare. Against this backdrop, the chapter proposes policy changes and regulatory reforms to enhance competitiveness and competition in the sector.

OECD Competition Assessment Reviews: Tunisia 2023

5. Selected passenger transport services

Abstract

5.1. Introduction

Transport plays a vital role in moving tourists efficiently from their places of residence to their final destinations and then on to supporting attractions. The location, capacity, efficiency and connectivity of transport can play a significant role in how destinations develop physically by influencing visitor mobility and facilitating the internal movement of visitors between the various components of the tourist experience, such as accommodation, attractions and commercial services. Due to the highly seasonal nature of tourism, demand and supply in the transport service market do not always align, putting pressure on existing transport services and infrastructure, particularly at the local level and in urban contexts. Managed effectively, transport and tourism synergies can improve visitor mobility to and within destinations, enhance visitor satisfaction, and help to secure the economic viability of local transport systems and services by serving both residents and tourists (OECD, 2020[1]). In Tunisia, transport is the second-largest contributor to tourism revenues, accounting for 19.6% of total tourism gross value added and 23.7% of all tourism spending in 2019. However, service quality and mobility are hampered by several restrictions limiting availability and affecting prices. This assessment focuses on key modes of transportation used by tourists in Tunisia and analyses barriers affecting tourist transport, car rental services and non-regular public transport services such as taxis and ride‑hailing services.

5.2. Tourist transport

5.2.1. Background

Tourist transport is defined in Tunisian law as “any transport of persons reserved for tourists or provided by a tourist establishment for the benefit of its customers”.1 It typically includes the use of buses and shuttles. It is distinguished from public transport, which includes taxis and other for-hire services, and from private transport.2 The law stipulates that tourist transport is subject to a cahier des charges, or set of specifications, and prior declarations to the competent branches of the Ministry of Transport. In practice, there is no such cahier des charges. Operators wishing to offer tourist transport must instead comply with the cahier des charges for travel agencies, which is supervised by the Ministry of Tourism.

Tourist transport can be provided only by drivers holding a professional licence granted by the governor of the region where their business is based, and it is regulated by the Ministry of Transport.3

Tourist transport vehicles must comply with signage requirements to facilitate policing and for consumer protection purposes.4

5.2.2. Description of the obstacles and policy makers’ objectives

Service exclusivity: Operators of tourist transport must qualify as Category-A travel agencies and meet specifications set out in the associated cahier des charges (see Section 6.2.2). No other authorisation process exists for companies operating tourist transport. It is worth mentioning that only companies are allowed to provide tourist transport services, not individuals. According to stakeholders, service companies informally provide some tourist transport services, notably in terms of organisation and interactions with clients, but still rent vehicles and drivers through travel agencies. Drivers hired for tourist transport must, however, have specific authorisations, which are discussed below.

The OECD has not identified public policy objectives behind making tourist transport an activity exclusive to travel agencies and hence requiring service providers to meet the requirements of the relevant cahier des charges. The regulation of travel agencies through a cahier des charges is likely in place to ensure the quality of services. The OECD understands that the Ministry of Transport attempted to propose a cahier des charges for tourist transport, but that it was blocked amid strong opposition by travel agencies.

Restrictions on the legal structures required for the exercise of certain operations, such as tourist transport, are used by authorities to ensure the financial standing of market participants. The OECD understands that Tunisian authorities consider companies to be more capable of offering sound financing guarantees than individuals and that they are also deemed less likely to offer low-quality services that could harm consumers.

Operational requirements: Tourist transport vehicles can be driven only by a person holding a professional licence. According to Decree No. 2007‑4101, a professional licence is granted to those providing collective public transport or tourist transport, provided the applicant holds the correct driving licence, completes a training programme at an approved institution, and completes a road safety course.

In addition to these requirements, two key barriers are linked to the granting of professional licences for tourist transport:

Applicants must have a contract with an employer to apply for the licence (where they are not the owner of the company providing tourist transport) and they must apply to renew their licence when they change employers.

No driver can hold more than one professional licence at the same time, meaning, for example, that a driver cannot be both a taxi driver and a tourist vehicle driver.

Stakeholders informed the OECD that the tourist transport industry is facing difficulties in renewing its ageing vehicles fleet. Law No. 94‑41 on foreign trade stipulates that the import of second-hand tourist transport vehicles, including coaches and minibuses is subject to prior authorisation by the Ministry of Commerce.5

The professional licence is likely required for safety purposes. The rationale behind requiring drivers to have contracts with employers to obtain professional licences may aim to ensure that only companies provide tourist transport services. It may also aim to ensure that drivers are not state, local government or public enterprise employees, a prohibition enshrined in law. In their applications, drivers must provide a sworn declaration that they are devoted solely to driving tourist transport vehicles and that they are not employed by the civil service, local authorities or public establishments or enterprises.

The requirement to apply for a new licence if a driver changes employers likely aims to reinforce the linkage of the licence with a specific employer.

Restriction on the import of second-hand tourist transport vehicles is in place to promote the local automotive industry and better manage the trade deficit.

Qualification requirements: According to Law 2006‑2118,6 the legal representative of a tourist transport company or an employee at management level must meet one the following conditions:

have at least three years of work experience at management level in a public passenger transport company, in tourist transport, or in the rental of private cars or limousines, buses or coaches

hold a diploma from a licensed tourism school in a specialisation related to tourist transport and a baccalaureate or a diploma deemed equivalent to this level and relevant experience in Tunisia of at least one year7

hold a university degree or a diploma equivalent to this level in a specialty related to tourist transport.

Professional qualification requirements seek to ensure the quality of services and to avoid unqualified management.

5.2.3. Harm to competition

Service exclusivity: If travel agencies have the exclusive right to provide tourist transport services (and meeting the requirements of the cahier des charges for travel agencies is difficult), this will reduce the number of operators in the market, creating artificial scarcity and increasing prices for consumers. If new entrants are interested only in providing transport services around Tunisia, it might be excessive to make them comply with the onerous and complex requirements for operating a travel agency that may organise tours all over the world. This restriction will also reduce the quality and range of services, and incentives for innovation. In theory, other providers of tourist services, such as service companies, must contract with travel agencies to organise and offer transport services to customers. In practice, however, the OECD understands that many service companies provide tourist transport services informally, except for transport by bus. This creates an uneven playing field between legal operators and operators that do not comply with the legal framework.

The existence of cahiers des charges that set minimum professional and material requirements to operate beyond those that would ensure safety and consumer protection leads to an increase in companies’ fixed costs. This will increase prices charged in the market. These barriers may also reduce the number of companies in the market, which will result in less competitive pressure for incumbent companies. The content of, and need for, such requirements are analysed in Section 6.1.

Restrictions on legal structures prevent sole proprietorships from offering tourist transport services. This increases the costs of entering the market and also operating costs. According to stakeholders, in practice, sole proprietorships offer tourist transport services to customers on an informal basis.

Operational requirements: The requirement for a professional licence in addition to a driving licence may reduce the number of potential drivers, making the sector less competitive and reducing the number of services. The requirement to have a work contract in place to qualify and receive a professional licence may delay entry and reduce the number of market participants, as this appears to be an onerous requirement both for companies and individual drivers who have no way of knowing whether the individual’s application for a licence will be successful and permit them to take up a position as a driver. The requirement to seek a new licence when changing employers may discourage mobility and facilitate employers’ monopsony power, which may allow them to depress remuneration below a competitive level, reduce employment, or dictate other working terms and conditions.8 This requirement may also make it more difficult for companies to launch new services if it is difficult to employ drivers.

The exclusive character of the professional licence prevents drivers who provide one type of transport service from providing another, as each type of transport requires a separate professional licence and drivers may only hold one at a time. This may reduce the ability of drivers to seek more flexible business opportunities, for instance hindering entry into areas of high demand while increasing entry to areas with less demand or a lower willingness to pay. It may hinder the efficient use of drivers’ capacity, as they cannot change their mode of transport to follow seasonality and meet demand during peaks, such as moving from providing taxi services to tourist transport during the high season. Indeed, due to the highly seasonal nature of tourism, demand and supply in the transport services market do not always align and tourism professionals tend to have portfolio offerings that follow seasonality instead of sticking only to a single activity. Therefore, this restriction may unduly limit the number of suppliers, reduce competition between suppliers of different transport services, and result in higher prices.

Import restrictions generate distortions in the market by creating artificial scarcity and limiting consumer choice, which may translate into more expensive and lower-quality products (OECD, 2019[2]). This is particularly constraining for the tourist transport sector, which as confirmed by various stakeholders is penalised by an ageing vehicle fleet. The OECD understands that this situation is caused by a reduced investment capacity of operators strongly impacted by the pandemic coupled with very high prices of locally produced or imported tourist transport vehicles by authorised car dealers.

Qualification requirements: Requiring legal representatives of companies or managers to have specific academic qualifications or alternatively, three years of prior specialised experience in a leadership position in a specific type of transport enterprise, may increase costs for operators seeking to establish themselves in the market. This is particularly the case when there is a lack of suitably qualified workers. It may deter market entry.

5.2.4. Recommendations

The OECD’s recommendations for revising tourist transport requirements are as follows:

Revise the cahier des charges for travel agencies (see Section 6.2). Create a separate cahier des charges for tourist transport under the responsibility of the Ministry of Transport, as provided for in legislation. Related requirements should be exclusively transportation-based and completely independent of travel agencies’ activities.

Remove the professional requirements for legal representatives or management of agencies providing tourist transport services.

With regard to the professional licence for tourist transport:

Abolish the work contract requirement. Individuals should be able to obtain a professional licence independently, irrespective of whether they have a work contract.

Abolish the exclusivity clause. An individual should be allowed to engage in different activities if they satisfy the relevant requirements.

Revise the restrictions on the import of used tourist transport vehicles in line with OECD (2019[2]) recommendations on international trade.

Adapt existing regulations to allow sole proprietorships to provide tourist transport services.

5.3. Vehicle hire

5.3.1. Background

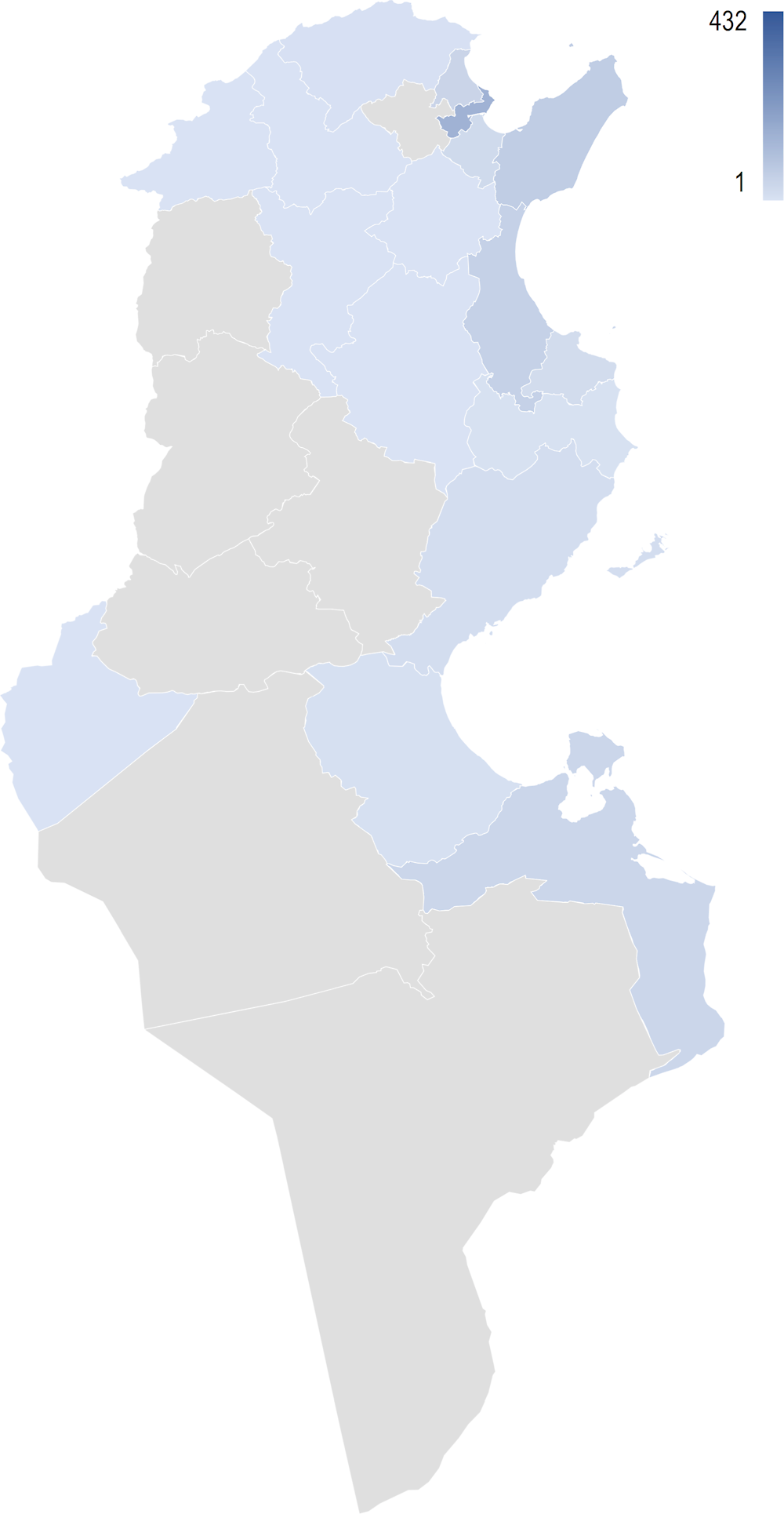

Vehicle hire is defined in Tunisian law as “any operation under which the lessee receives a vehicle with or without a driver, for a fixed period and for remuneration, both agreed in advance”9 and it is regulated primarily by Law 2004‑3310 and a cahier des charges.11 Law 2004‑33 provides that vehicle rental is covered by a cahier des charges. The cahier des charges covers the rental of passenger cars, hybrid cars and vans, and sets out minimum entry and operating standards. The cahier des charges is an ex-post authorisation to operate a vehicle rental agency and is to be signed by the agency’s representative and presented to the Ministry of Transport and the Direction Régionale du Transport, or Regional Land Transport Authority. In 2019, the country had 468 car rental agencies. The activity is heavily dependent on tourism and most agencies are located in tourist areas (Figure 5.1)

Figure 5.1. Vehicle hire agencies by region

Source: Adapted from ONTT (2019[3]), Rapport Annuel, https://www.ontt.tn/sites/default/files/inline-files/rapport2019.pdf

5.3.2. Description and objectives of the provisions

Fleet requirements: Vehicle rental agencies must own or rent at least 20 vehicles, down from 25 vehicles following the Order of the Minister of Transport of 5 February 2022 approving the cahier des charges relating to the activity of a car rental establishment.

The OECD understands that this provision is intended to ensure a certain level of service. One goal could be to avoid a proliferation of small, unstructured operators. It also seeks to encourage growth and job creation by companies.

Vehicles that are owned or hired by agencies are subject to several requirements, including proper registration and that:

Vehicles rated 7 horsepower or less must not be more than three months old when first used by the agency, and other vehicles no more than one year old.

Vehicles rated 5 horsepower and below must be less than 42 months old, those rated 6 horsepower must be no more than five years old, and those rated 7 horsepower and above no more than seven years old.

The OECD understands that these limits on vehicle age aim to encourage the renewal of Tunisia’s vehicle fleet, which was ageing at the time the specifications were adopted, and to ensure safety by strengthening the standards applied to vehicles. These requirements may also be easier to monitor than more detailed safety standards.

Professional experience: Agency representatives must satisfy one of the following three conditions: 1) possess training of at least two years in the field of commerce, economics or law; 2) have a minimum of three years of experience in the car rental, public transport or tourism industry; or 3) have a minimum of one year of study at a tourism school.

Additionally, according to Law 2006‑2118,12 legal representatives of vehicle rental companies or employees at management level must meet one of the following conditions: 1) possess at least three years of work experience as a manager or at management level in a public transport company for people, or in tourist transport, or in rentals of private cars, limousines, buses or coaches; 2) hold a diploma from a licenced tourism school in a specialisation related to tourist transport and a baccalaureate or a diploma deemed equivalent to this level and have had experience in Tunisia of at least one year;13 3) hold a university degree or a diploma equivalent to this level in a specialty related to tourist transport.

The OECD understands that specific academic qualifications or professional experience in the field are seen to guarantee a minimum level of knowledge of the activity or profession in question and compliance with quality and safety standards and help to ensure the sustainability of the business.

Legal structure: Legislation provides that only companies can offer vehicle hire services.14 This means that sole proprietorships cannot enter the market, which was possible under the previous version of the cahier des charges regulating vehicle hire.15 It appears that the only possible way for a sole proprietorship to provide vehicle hire services is to qualify as a Category-A travel agency.16 Vehicle hire is listed as one of the activities in which travel agencies may engage, and those who wish to provide such services in that capacity must meet the specifications set out in the applicable cahier des charges (see Section 6.1).

Restrictions on the legal structure required to engage in certain operations, such as vehicle rentals, are used by authorities to ensure operators’ financial standing. The OECD understands that the authorities consider companies to be more capable of offering sound financing guarantees than individuals and are more likely to benefit from leasing services. They are also deemed less likely to offer low-quality services that could harm both local consumers and the sector’s international competitiveness. According to the Ministry of Transport, the cahier des charges was adapted to reflect the realities of the market, in which only companies provide vehicle rental services.

5.3.3. Harm to competition

The existence of cahiers des charges mandating minimum professional and material requirements increases companies’ fixed costs, which increases the cost of market entry. This reduces competition and results in higher prices. As these barriers may reduce the number of companies in the market, there will be less competitive pressure on incumbent businesses, which might also increase informality. In this respect, the Chambre Syndicale des Loueurs de Voitures, or National Syndicate for Vehicle Rentals, has claimed that there are around 52 000 vehicles rented informally every year in Tunisia.17 This informality is driven by a supply shortage and price increases during peak periods due to overwhelming demand. The content of, and the need for, the cahier des charges requirements are analysed below.

Fleet requirements: Requiring a minimum number of vehicles excludes small and medium-sized service providers that may be able to better meet consumer demand from the vehicle rental market. This limits choice for consumers and results in a lack of available vehicles, notably during peak periods such as tourism high seasons. It also limits the flexibility of companies to respond to changing business conditions by scaling down their activities and leads to high fixed costs, reducing competition. Maintaining large fleets also increases operating and maintenance costs, pushing up prices for consumers and encouraging them to take advantage of cheaper informal options.

Maximum vehicle age requirements raise entry costs and deter market entry, especially among smaller and medium-sized enterprises. High start-up costs likely increase rental costs for consumers. They also impose a long-term commitment to fleet renewal, which is a significant undertaking. These restrictions are imposed in addition to mandatory technical inspections of vehicles. Benchmarking with EU member states shows that the policy objectives of guaranteeing road safety and the quality of the technical inspections may be achieved by less restrictive means. The principal factors determining the condition of goods vehicles are: proper operation; kilometres covered; years in service; and regularity of technical inspections. Maintaining vehicles correctly becomes particularly important as they age (European Commission, 2014[4]). Further, the cahier des charges may set standards above the level that well-informed customers would choose, with some consumers preferring lower cost to newer vehicles. Consumer welfare can be reduced by such standards as consumers are prevented from using cheaper services that they might prefer.

Professional experience: Requiring specific academic qualifications, or, alternatively, three years of specialised experience in car rentals, may increase costs for operators looking to set up and operate. This is particularly the case when there is a lack of suitably qualified workers. These requirements may deter market entry and reduce innovation.

Legal structure: Restrictions on legal structures prevent sole proprietorships from offering car rental services, raising entry and operating costs. According to stakeholders, in practice, sole proprietorships offer car rental services on an informal basis. In other jurisdictions, such as Croatia, both companies and individuals may provide vehicle rental services.18

5.3.4. Recommendations

The OECD’s recommendations for revising requirements on vehicle hire are:

Abolish or lower the minimum number of vehicles that vehicle rental companies are required to operate.

Abolish or significantly increase the maximum vehicle age requirements and complement this with other measures to ensure roadworthiness. These could involve establishing a uniformly applied maximum number of years in service and a requirement to pass regular technical inspections. The establishment of additional criteria should ensure that both new and existing companies operate under the same regulatory framework.

Remove professional experience requirements.

Adapt existing regulations to allow sole proprietorships to provide car rental services. This was possible under the previous version of the cahier des charges.

5.4. Taxis and other for-hire vehicles

5.4.1. Background

Non-regular public road transport includes the following: individual taxis; grand tourisme taxis; collective taxis; louage, or hire, taxis; and rural transport taxis.19 Grand tourisme taxis are allowed to operate between airports and any destination countrywide. Collective taxis are used mainly in big cities and follow specific routes. Louage taxis are the most commonly used form of non-regular public road transport between cities. And rural transport taxis are used to connect cities with villages and remote areas. These types of transport are a very important mobility option for tourists. In 2019, there were a total of 52 373 taxis and other for-hire vehicles registered in Tunisia.

Table 5.1. Non-regular public road passenger transport in Tunisia

|

Individual taxis |

Rural transport taxis |

Grand tourisme taxis |

Collective taxis |

Louage taxis |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

32 183 |

7 234 |

184 |

2 701 |

10 071 |

52 373 |

Source: Ministry of Transport, 2019 (http://www.transport.tn/uploads/Statistique/Transport_public_non_regulier_personnes_fr.pdf)

5.4.2. Description of the obstacles and policy makers’ objectives

Licensing process and conditions

Article 23 of Law No. 2004‑33 stipulates that operators of taxis and other for-hire vehicles require licences issued by the governor of the region where the applicant resides. Licences are granted following agreement between the governor and the commission consultative régionale, or regional advisory commission. The composition and functioning of the commission are established by Decree No. 2004‑2410. Once authorisation is obtained, if the applicant does not obtain the licence document for the vehicle registered within two years, authorisation is cancelled.20 The licensing process is subject to several conditions:

Quota system: The ministry’s land transport department annually calculates quotas for new authorisations to be granted for each governorate and for each form of non-regular public road transport. These quotas consider many parameters, including existing transport available and the density of the population in the governorate. However, the territorially competent governor has the freedom to manage the quotas allocated to the governorate.

The OECD understands that this system was put in place to ensure a balance between supply and demand in the market for non-regular public road transport services nationwide.

Legal structure: Companies are prohibited from obtaining operating licences and hence from providing non-regular public road transport. Such services may be offered only by individuals. However, this rule is not applicable to companies that were offering non-regular public road passenger transport by taxi, louage taxi and rural transport taxi before it was introduced.21 According to authorities, these companies continue to exist, may expand their fleets, and can renew their operating licences.

The OECD understands that the change was implemented to promote employment opportunities among poorer people. It may reflect policy makers’ preference for independent owner/operator businesses over larger businesses employing drivers, and may reflect a desire to avoid the risk of monopolisation of licences by a small number of operators.

Restrictions on individuals: A licence granted to an individual is valid only for a single named vehicle.22 The vehicle to be used as a taxi or other for-hire vehicle may be owned or leased, but an individual cannot register more than one vehicle. Companies in the market must have at least five vehicles and may apply to add further vehicles to their fleets (see below).

Activity restrictions: An applicant may obtain only one authorisation to engage in one of the following activities: individual taxi services; collective taxi services; grand tourisme taxi services; louage taxi services; or rural transport taxi services.23 The policy objective is probably to ensure the quality of services and to control supply by limiting drivers to a specific category.

Licensing requirements

Eligibility criteria: In order to obtain an operating licence, applicants must: 1) hold Tunisian nationality and have no criminal record; 2) not be an employee of the state, local government or a public enterprise; 3) engage exclusively in the activity and not have any other sufficient source of revenue (defined as three times the minimum salary in the non-agricultural sector);24 and 4) satisfy minimum material requirements as set out in law (see fleet requirements, below).

The applicant should also: 1) hold a professional licence; 2) hold a Category-D or -D1 driving licence; 3) hold a professional aptitude certificate; 4) have been employed as a driver by a public passenger carrier for at least one year; and 5) have undertaken a roadside first-aid course.25

Fleet requirements. Several minimum requirements are set out in the Order of the Minister of Transport of 22 January 2010, including the maximum ages of vehicles, minimum fleet sizes (for companies), and office and garage specifications.

Maximum vehicle age: All cars used as individual taxis, collective taxis, grand tourisme taxis, louage taxis and rural transport taxis must be less than seven years old when first used, and the maximum age for their use is 15 years.

Fleet sizes and renewal: Companies must have a minimum fleet size of five vehicles.26

Offices and garages: Companies are required to have two premises available, one for their head office and the other to house their vehicles.27

Minimum equipment requirements are place likely to the ensure quality of service. The OECD understands that limits on the age of vehicles aim to encourage the renewal of Tunisia’s vehicle fleet, which was ageing at the time the specifications were adopted, and to ensure safety by strengthening the standards applied to vehicles. Age requirements may also be easier to monitor than more detailed safety standards. Age restrictions may also be imposed by jurisdictions wishing to reduce carbon emissions. London, for example, has tightened age restrictions for this reason. Between 1 November 2021 and 31 October 2022, vehicles older than 12 years were ineligible for licensing in London. Between 1 November 2022 and 31 October 2023, vehicles older than 11 years will be ineligible for licensing. Previously, an age limit of 15 years was in place.28

Tunisia’s fleet size provision is intended to ensure a certain level of service among companies. It is important to note that this applies only to existing companies, as new companies are not able to enter the market. One aim could be to avoid a proliferation of small, unstructured operations. The measure also seeks to encourage growth and job creation by companies. According to the ministry, prior approval for increasing fleet sizes is required, but there is no clear procedure for applicants.29

Professional licence: Drivers of non-regular road passenger transport must have a professional licence, conditions for the granting of which are set out in Decree No. 2007‑4101. Licences are granted by the governor of the region in which the driver resides, and are valid for five years.30 In order to obtain a professional licence for taxi, louage taxi or rural transport taxi services, applicants must: 1) hold Tunisian nationality; 2) hold a professional aptitude certificate, as set out in Decree No. 2006‑2118, to operate individual taxis or grand tourisme taxis, and provide a photocopy of this certificate with their application; 3) have completed a road safety course; and 4) not be a state, local government or public enterprise employee.31

In addition, the professional licence is issued subject to the following conditions:

Minimum licensed period: Applicants must have held a Category-D or -D1 driver’s licence for at least two years.

Activity restrictions: The professional licence is linked to a single type of transport and no driver can hold more than one licence at the same time.

The OECD understands that drivers are required to obtain professional licences for safety reasons and consumer protection. The requirement to have held a specific driving licence for at least two years likely seeks to ensure passenger and road safety, and the quality of services, and exclude unqualified drivers. The aim of the activity restriction is likely to ensure better control of supply by limiting drivers to specific service categories.

Driving licence: Drivers of non-regular passenger road transport must have an appropriate driving licence. According to Decree No. 2021‑510, driving licence categories have been updated to specify the following categories for non-regular passenger transport:

Category-D: passenger transport vehicles with more than eight seats, excluding that of the driver

Category-G: vehicles in the taxis, louage taxi and rural transport taxi categories.

Before obtaining a Category-D or -G driving licence, applicants must already have a Category-B licence, which is the standard driving licence for motor vehicles, and have undertaken relevant training.32 The minimum age for a Category-B licence is 18, while the minimum age for Category-D licences is 21 and that for Category-G licences is 20.33 In order to obtain a Category-D or -G licence, applicants must apply to the regional services of the Agence Technique des Transports Terrestres (ATTT), or Technical Agency for Land Transport, through a recognised training establishment specialising in driving and road safety.

To obtain a licence, applicants must have completed a minimum number of theory and practical training sessions. They must also have successfully completed three exams: theory; a practical exam focused on traffic; and a practical exam focused on manoeuvres. For all licences, a medical certificate is required. For Category-D and -G licences, it must be issued by an occupational doctor.34 Category-D and -G licences are valid for three years for drivers under 60 (vs. 10 years for a Category-B licence), for two years for those aged 60‑76 (vs. five for Category B), and for one year for those over 76 (vs. three for Category B).

The OECD understands that Category-D and -G licences have a shorter validity period to ensure that licence holders continue to fulfil the conditions for licences and that valid licences are active.

Professional aptitude certificate: To obtain this certificate, applicants must be Tunisian nationals, hold a Category-D driving licence, and have passed an exam set by the local governor, which, according to legislation, is held at least once every two years for individual taxis and at least once every three years for grand tourisme taxis. Once obtained, the certificate is valid indefinitely. The certificate is delivered by the governor to successful applicants to provide services within an area marked on the certificate, which in the case of grand tourisme taxis can cover the whole country.35

The professional aptitude certificate is likely in place to ensure the quality of services. The exam requirement is in place to ensure passenger and road safety by assuring drivers’ knowledge.

Tariff regulation

According to Article 15 of Decree No. 2007‑2202 of 3 September 2007, the tariff for non-regular passenger transport is set by a joint decision by the Ministry of Transport, the Ministry of Commerce and the Ministry of Tourism. The decree does not specify a time schedule for tariff revisions. The Order of the Minister of Transport of 29 November 2022 revised tariffs, with an overall increase of 15% for all taxi categories.

Decree No. 2014‑409, which sets out the role of the Ministry of Transport, provides that the ministry is required to set the prices of the services falling within its competence. The likely policy objective is consumer protection and to support the Tunisian public transport system by increasing affordable mobility.

Table 5.2. Newly adopted individual taxi tariffs

|

Taximeter flag fall |

900 millimes |

|

Taximeter flag fall from airport |

4 500 millimes |

|

Distance |

46 millimes per 79 metres |

|

Waiting time |

46 millimes per 18 seconds |

|

Luggage (over 10kg) |

1 000 millimes per unit |

|

Night tariff |

50% from 9 p.m. to 5 a.m. |

Source: Ministry of Transport (2022[5]), http://www.transport.tn/fr/terrestre/article/378/tarifs-du-transport-non-regulier-des-personnes.

5.4.3. Harm to competition

Licensing process and conditions

According to several stakeholders, demand for non-regular public road passenger transport and requests for authorisations, especially in large cities, greatly exceed the official quotas, creating an artificial scarcity of supply. The technical criteria underlying the system are not communicated, raising questions as to their adequacy to address dynamic, fluctuating demand for mobility that is characterised by proliferation, multiplicity and diversity in terms of needs, actors and modalities. Governors’ management of quotas also raises questions. The OECD has been informed that the licensing process is not transparent, giving considerable discretionary power to governors and increasing the risk of rent-seeking behaviour and favouritism.

The restriction on legal structures raises two issues. First, it limits the range of business models in the industry. In particular, it prevents the establishment of taxi companies that own multiple vehicles and which hire drivers as employees. Taxi drivers are thus required to be entrepreneurs with access to vehicles, which may reduce the number of market players. Multi-car taxi businesses operate in many other jurisdictions, and can give rise to significant economies of scale, including by managing vehicle downtime risk, spreading repair and maintenance costs, and diversifying service offerings, such as the provision of multiple cars for events. In a competitive market, cost savings arising from these efficiencies lead to lower consumer prices, and service quality gains are also to be expected (OECD, 2020[6]). Other transport businesses in Tunisia, such as tourist transport, are not restricted to individuals. In addition, new companies were allowed to enter the taxi market until 2006.

Second, the legislation treats existing market players differently from new entities entering the market. This grandfather clause restricts competition because new market entrants can operate only as individuals and not company entities, unlike like some incumbents.

An individual has the right to use only one vehicle. If that specific vehicle cannot be used, perhaps due to a need for repairs, inefficiencies could result as the individual may need to register a new vehicle or cease work for the period the registered vehicle is off the road. This affects both taxi operators and consumers. Established companies, however, may add vehicles to their fleets with permission from the Ministry of Transport.

The activity restriction prevents drivers providing one type of transport service from providing any other, as each type of transport requires an operating licence and individuals may hold only one licence for a particular transport service. This may limit flexibility and hinder entry into areas of high demand, yet it may increase competition in areas with less demand or a lower willingness to pay. It may hinder the efficient use of individuals’ capacity as they cannot change their transport offering to meet demand during peaks, such as by moving from standard taxi services to other for-hire services during high season. This may unduly restrict the number of suppliers, reduce competition between suppliers of different transport services, and result in higher prices.

Licensing requirements

Eligibility criteria: The cumulative provisions detailing eligibility criteria limit flexibility and impose significant limitations on alternative business models. They effectively eliminate part-time driving and place such drivers at a disadvantage to those offering informal ride‑hailing services. In Tunisia, these services are not regulated (see Section 5.5), so drivers can undertake these activities while generating other income streams and operating in other occupations. Given this, the provisions may reduce the number of qualified drivers, shrinking the number of market players or potential entrants, and raising prices for consumers.

The associated documentary requirements, such as proof of revenues, may increase the administrative burden on market players, increasing costs and deterring market entry.

In general, requiring prior specialised experience or specific academic qualifications may increase a business’s market entry and operating costs, particularly amid a lack of suitably qualified workers. This may limit the number of service providers and result in increased prices. The specific minimum professional experience requirement may limit the number of service providers in the market. A reduced number of qualified professionals with the required authorisation may thus increase costs for companies wishing to establish themselves and operate in the market.

Fleet requirements: A requirement to adhere to very specific or excessive standards may raise the costs of entry for suppliers, discouraging potential market entrants and reducing the number of participants in the market over time.

Maximum vehicle age requirements increase entry costs and deter market entry. High start-up costs reduce competition and likely increase the cost of services for consumers. These standards may exceed the level that well-informed customers would choose, with some preferring lower cost to newer vehicles. Consumer welfare can be reduced by such standards, as consumers are prevented from using cheaper services that they might prefer. In Australia, by contrast, the Taxi Service Commission of Victoria removed age limits for taxis and hire cars in 2016.36 Previously, taxis were required to comply with a maximum vehicle age limit according to vehicle type and the area in which it was driven. In metropolitan Melbourne, for example, the maximum vehicle age was 6.5 years for operations and 2.5 years for initial licensing.37

Setting a minimum number of vehicles excludes some small and medium-sized service providers that may be able to better meet consumer requirements from the market. It also means high fixed costs for businesses, which can be passed on to consumers. The lack of publicly available rules or guidelines on the procedure for applying to the Ministry of Transport to add vehicles to a company’s fleet, and the lack of objective requirements for decision makers, could lead to discrimination between applicants and result in legal uncertainty, deterring companies from increasing their fleet sizes.

Professional licence: The conditions for obtaining professional licences duplicate those required for obtaining operational licences. The additional licence requirement is likely an administrative burden as applicants must already satisfy operational licence requirements and specific education requirements to obtain a Category-D or -G driving licence. In jurisdictions such as France, taxi drivers are required to obtain a professional licence but require only a standard driving licence.

The requirement to have held a Category-D or -G driving licence for at least two years delays market entry. Other jurisdictions, such as France,38 require drivers to have held a standard driving licence for a minimum period instead (three years in France). In Spain, no minimum period exists for taxi drivers, but for ride‑hailing services, drivers are required to have held a standard driving licence for at least two years.

The activity restrictions prevent drivers who provide one type of transport service from providing another, as each type of transport requires a professional licence and drivers may only hold one such licence. In many other jurisdictions, drivers can offer both taxi and tourist driver services. In the US, most Uber drivers also operate as taxis.39 In Spain and Italy, thanks to partnerships with taxi associations,40 taxi drivers are able to operate using Uber’s platform and so are able to offer both standard taxi and tourist driver services.41 This model also operates in countries such as Germany and Austria.42

Driving licence: Having to renew Category-D or -G licences every three years, more than three times as often as standard licences, may constitute an excessive administrative burden. Such burdens increase costs for operators with possibly no discriminatory effect on competition in the market, such as time spent, possible delays and opportunities missed to maximise efficiency. As such, they might reduce incentives for market entry and hinder efficiency and competitiveness. In France, driving licences for passenger transport vehicles must be renewed every five years for drivers aged under 55.43

Professional aptitude certificate: The examination requirement may delay or deter market entry, as it is run only every two years for individual taxis and every three years for grand tourisme taxis. If examinations are not run according to the legislation, this may further reduce the number of individuals authorised to operate in the market, raising costs and reducing the diversity of services offered.

Tariff regulation

This provision may limit the ability of operators to set prices, leaving them unable to undercut rivals’ prices to gain market share. Even if regulating taxi tariffs is a common practice in many jurisdictions, the absence of any reference to the frequency of tariff revisions represents a source of uncertainty for operators. In France, taxi tariffs are revised on an annual basis, taking several parameters into consideration, including fuel and vehicle prices, and repair, maintenance and insurance costs.44

Stakeholders informed the OECD that revisions of regulated tariffs were constantly delayed by authorities, despite pressing requests by taxi trade unions following several fuel and insurance price increases. This was the main factor behind taxi drivers’ increasing participation in the ride‑hailing market, especially during rush hours. This activity is unregulated in Tunisia and prices are freely set by the operators of the platforms. However, stakeholders reported that it created market distortions and was seriously affecting consumer welfare (see Section 5.5).

5.4.4. Recommendations

The OECD’s recommendations for revising requirements for taxis and other for-hire vehicles are as follows:

In terms of the licensing process and conditions, authorities should:

Revise and publish the criteria defining taxi quotas and the conditions for granting operating licences, and streamline procedures for obtaining licences by ensuring the transparency of selection criteria (see Chapter 9).

Allow companies to enter the market and operate taxi and other for-hire vehicle businesses, not just individuals, in line with the cahier des charges that was in place until 2006, and abolish minimum fleet size requirements.

Allow drivers to offer more than one type of transport if they satisfy the required conditions.

In terms of licensing requirements, authorities should:

Abolish the minimum professional experience requirement.

Abolish the requirement for drivers to drive full-time and not have sufficient other income sources.

Abolish or increase the maximum age requirements for vehicles used for the first time and replace them with stringent safety regulations and more frequent technical control measures.

Reconsider the need for the professional licence, as operators must already hold a specific driving licence for a particular transport category and are required to hold an operating licence. Consider increasing the validity period for driving licence categories D and G to align it with that of Category B.

If authorities consider the professional licence essential, they should consider abolishing the requirement to hold a specific driving licence. Policy makers could require drivers to have held a standard driving licence for two years.

If aptitude certificates for taxis (individual and grand tourism) are regarded as essential, consider increasing the frequency of the associated examinations and guarantee candidates’ right to sit exams on a regular basis.

In terms of tariff regulation, authorities should:

Adopt a more flexible and predictable tariff framework for non-regular passenger road transport that promotes fair competition with providers of new transport services.

Ensure the framework allows regular tariff revisions based on objective and transparent criteria such as the prices of fuel, vehicles and insurance. An annual revision, as is mandated in some jurisdictions, could be considered.

5.5. Ride‑hailing services

5.5.1. Background

Disruptive innovation in the road transport sector has changed the regulatory and competitive landscape worldwide (OECD, 2022[7]). In its Handbook on Competition Policy in the Digital Age, the OECD explained that this has resulted in key benefits to consumers:

In recent years, ride‑hailing services have entered and quickly expanded their provision of competing services. The platform model has disrupted traditional taxi and private hire vehicles markets and improved services for consumers.

While many features were introduced by new players, incumbents have often responded, for instance, by introducing or signing up to their own digital applications with many of the same features” (OECD, 2022[7]).

Ride‑hailing services are not yet regulated in several jurisdictions, but taxis and private‑hire vehicles are often subject to extensive regulation.

In Tunisia, no regulatory framework exists for ride‑hailing services. However, the OECD understands that these services are offered mainly by taxi drivers through several apps, including Bolt, Yassir, InDriver and OTO.

5.5.2. Description of the obstacles and policy makers’ objectives

Ride‑hailing platforms are not regulated in Tunisia because the disruptive innovations and new business models to which they have given rise do not fit into the traditional regulatory framework for tourist and public transport. According to the authorities, ride‑hailing platforms do not fall within any of the definitions of road transport (tourist, public or private transport) in Law No. 2004‑33 on the organisation of land transport.

The Ministry of Transport informed the OECD that a cahier des charges to regulate the sector is currently being drafted. Decree No. 2014‑409, setting out the role of the Ministry of Transport, provides that the ministry is required to:

intensify the use of new [information and communication technology] applications in the various fields falling within its competence to ensure the optimal exploitation of the means and the infrastructure of transport.

The OECD understands that this initiative is subject to strong objections by taxi federations and individual taxi drivers.

5.5.3. Harm to competition

In general, the entry of new companies and business models may generate significant consumer benefits in the form of lower prices, shorter waiting times, increased choice, higher quality and greater availability of services, creating efficiencies. Yet given Tunisia’s lack of a regulatory framework for ride‑hailing, a risk exists that these new business models will gain favour over traditional taxi and transport services that are subject to regulatory requirements, meaning that they would not operate on a level playing field, distorting competition outcomes.45 Further, in Tunisia, it appears that the current supply of road transport vehicles has not changed with the introduction of these platforms, as regulated taxi drivers are the main users of the platforms, which are seen as a way to get around regulated tariffs.

When using these apps, taxi drivers claim they not bound by the regulated fare system, since they are providing a private service and can therefore charge higher prices. In some jurisdictions, taxi drivers are allowed to negotiate fees with customers and are not required to use a taximeter when the fare is pre‑negotiated, provided that passengers have access to the formula governing the price (OECD, 2020[6]). Ride‑hailing services generally use dynamic pricing algorithms that adjust rates based on a number of variables, such as time, distance, traffic flows and passenger-to-driver demand. This can result in temporary price spikes during particularly busy periods, as when demand increases, the algorithms use a “surge pricing” mechanism to encourage more drivers to get on the road to help meet the number of passenger requests. Once more drivers are available and passenger requests are met, demand becomes more manageable and fares generally revert to lower levels.46 However, surge pricing remains controversial as it creates scope for price manipulation.47

During consultations with stakeholders, it was confirmed that most taxis use these apps, especially during rush hours, when fares are highest. This leaves consumers with almost no alternatives, given Tunisia’s inadequate public transport services, and makes it very difficult for consumers who do not use the apps to find rides. Moreover, app-defined prices can exceed regulated fares for the same trip by threefold. According to a recent investigation report by Tunisian media outlet Al Katiba,48 such price increases appear to be a constant, even outside rush hours, raising questions about potential competition infringements. The issue of whether intra-platform algorithmic pricing results in anti-competitive agreements or concerted practices is widely debated. The fact that drivers remain independent contractors rather than workers or employees of such platforms and are at the same time unable to compete and set fares for rides freely suggests that competition enforcers could view the platforms as hub-and-spoke arrangements that facilitate horizontal price‑fixing cartel conduct (Bekisz, 2021[8]).

Box 5.1. EU’s highest court confirms liability of cartel facilitators

In a judgement dated 22 October 2015 (Case C-194/14 P), the Court of Justice of the European Union upheld a decision by the General Court and thereby a European Commission decision of 2009 to hold Swiss consultancy firm AC Treuhand liable under EU antitrust rules for facilitating cartels according to Article 81(1) of the European Commission Treaty (now Article 101(1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union [TFEU]), irrespective of it not being active in the cartelised market.

This decision was a landmark judgment, since it was the first time the court had ruled on the so-called “facilitation” of cartels, such as the organisation of a cartel by a consultancy firm. The ruling was particularly important for two reasons.

First, the court confirmed that the service agreement between AC Treuhand and suppliers of heat stabilisers constituted an illegal agreement under EU competition rules. Agreements that distort competition in the EU are illegal under Article 101 of the TFEU, irrespective of whether the parties involved operate in the same market. Moreover, the court held that the effectiveness of Article 101 of the TFEU, which prohibits anti-competitive business practices, would be endangered if facilitators such as AC Treuhand could escape liability.

Second, the court confirmed that the commission was entitled to fix the fine as a lump sum instead of using the value of sales as its basis. AC Treuhand, as a consultancy firm, was not active in the markets for tin stabilisers and ESBO/esters, and therefore had no sales in those markets.

Source: European Commission, Case C‑194/14 P, AC Treuhand AG v. European Commission, ECLI: EU: C:2015:717, https://curia.europa.eu/juris/liste.jsf?language=en&td=ALL&num=C-194/14%20P.

The use of ride‑hailing apps in Tunisia does not appear to have delivered the expected consumer benefits. It has not increased choice, as it is based on the supply of the current taxi system, and the consumer rating system does not seem to have improved quality, another of the apps’ anticipated benefits. It has also increased prices and affected service availability.49 Moreover, there seem to be growing data protection concerns, as shown by a complaint filed by the Instance nationale de protection des données à caractère personnel or Tunisian Authority for the Protection of Personal Data against one of the platforms.50

5.5.4. Recommendations

The OECD’s recommendations for ride‑hailing services are:

Ensure that anti-competitive distortions and safety concerns caused by the informal activity of current service providers are addressed.

Foster compliance in order to increase the size of the market and improve the quality of the services provided to consumers (Box 5.2).

Box 5.2. Examples of ride‑hailing regulation

Spain

In 2014, Uber became the first foreign ride‑hailing platform to operate in Spain. Its business model was soon declared illegal by regional courts for using drivers without licences (Noa, 2019[9]). In 2015, the US-based company returned to the Spanish market, which now included Cabify, a powerful local competitor. This time, operators had to comply with the country’s tourist vehicle driver regulations and strict rules under the Land Transport Regulation Act. Spanish regulation became some of the most stringent in Europe, imposing a ratio of one tourist vehicle driver per 30 taxi licences, with platforms required to provide 80% of their services in the region where their authorisations were obtained and to own a minimum of seven vehicles (Niblett, 2019[10]). The requirements were challenged by the Comisión Nacional de los Mercados y la Competencia, or National Markets and Competition Commission, and several industry associations that considered the restrictions an unnecessary barrier to innovation that harmed consumers (Cluet Vall, 2019[11]). In 2018, Spain’s Supreme Court upheld the restrictive regulation (Castro and Ramón Medina, n.d.[12]), although the 1:30 ratio was never respected in practice. In response, taxi drivers launched a series of massive protests, paralysing cities such as Madrid and Barcelona. In response, the government passed Royal Decree 13/2018, which mandated a four‑year transition period for the transfer of tourist vehicle driver licence regulation from a national to a regional level (Estado, 2018[13]). After that, it would be up to regions to authorise ride‑hailing platforms’ urban operations. In areas without a system in place by 2022, platforms would be allowed only to operate on inter-city routes, effectively abolishing them, since their business models focused on intra-city transport (Álvarez, 2022[14]). So far, only Madrid has passed a regulation permitting urban operations by tourist vehicle drivers. The transition period ended in October 2022, and if other regions do not speed up to follow the capital’s steps, ride‑hailing platforms will have to cease their operations in most of the country (Jiménez, 2021[15]).

Egypt

Egypt has become the biggest market in the Middle East and North Africa region for ride‑hailing platforms such as Uber and Dubai-based Careem. These two operators had been gaining ground in Egypt’s local transport market for years, fuelling strong opposition among taxi drivers that reached critical mass in 2017 (Oxford Business Group, 2019[16]). An administrative court ordered Uber and Careem to suspend their activities in 2018 following a lawsuit brought by taxi associations that accused them of hiring drivers who used private vehicles (Menabytes.com, 2018[17]). The Mahkamat al-Amoor al-Mustaejila bi-l-Qahira, or Cairo Court of Urgent Matters, overturned the ruling, although tensions in the sector remained high (Menabytes.com, 2018[18]). In order to tackle the legal challenges that ride‑hailing platforms had traditionally experienced in the country, the government approved Law No. 87 of 2018 and Executive Resolution No. 2 180 of 2019 (Sadek, 2019[19]). Among other provisions, the new regulations required the platforms to obtain five‑year renewable licences for a fee of USD 1.7 million and vehicle owners to obtain special licences to drive for Uber and Careem by paying an annual fee in the range of USD 56‑112 (Riad-Riad, 2018[20]). Furthermore, ride‑hailing companies were also required to: 1) store user data for 180 days and share it with the government upon request; 2) run background checks on drivers before hiring them; and 3) conduct random drug and alcohol tests. These regulations were the result of a consultation process with the platforms, which praised it as efficient and pioneering in the region (Mamdouh El Shiekh and S., 2019[21]), (Voanews, 2018[22]).

Mexico

In 2015, 18 months after Uber began operating in the country, the Government of City became the first Latin American authority to regulate ride hailing. Among other measures, the US platform became subject to a 1.5% ride levy, a yearly permit fee and a minimum vehicle value of USD 12 674 (De Haldevang, 2018[23]). In 2019, a ban on cash payments was imposed (Love and N., 2019[24]).

Encourage closer co‑operation between the Ministry of Transport and the Conseil de la Concurrence, or Competition Council, to further analyse and address potential anti-competitive conduct by ride‑hailing platforms (Box 5.1).

Regulating ride‑hailing may provide an opportunity to reform current extensive regulation of other transport services. The OECD recommends that new regulatory frameworks for ride‑hailing services, and any changes to existing regulations for taxis and other for-hire vehicles, seek to promote competition in the land transport sector. Regulatory changes should consider technological developments affecting how customers access those transportation services and work towards the removal of unjustified barriers to access (Box 5.3).

Box 5.3. Reassessing regulatory frameworks for taxis and for-hire vehicles

Taxi and private‑hire vehicle services are strictly regulated in many countries. Following recent innovations, at least some aspects of these regulatory frameworks are due for reassessment

First, the pace of innovation in these markets has highlighted the importance of focusing on principles rather than detailed rules when designing regulations. This is because more detailed rules may not be sufficiently flexible to accommodate future innovations and developments.

Second, supply constraints are common and likely to restrict competition. It is unclear whether the original rationale for these constraints ever necessitated such restrictions, but the emergence of ride‑hailing services has exposed their harmful nature.

Third, although ride‑hailing apps have improved price transparency and use dynamic pricing to boost service availability for passengers, traditional taxi services are required to offer fixed prices and are often unable to offer price estimates. This may overcome an asymmetric information problem when passengers hail a taxi on the street or from a rank, but it restricts the ability of taxi drivers to compete for passengers hailing rides using apps.

Fourth, taxi and private‑hire vehicles are often obliged to comply with various service and safety requirements. Although some requirements are excessively restrictive, creating entry barriers and increasing costs, the rationale for others, such as insurance and safety, remains valid. New and competitive digital services may find alternative means to comply with certain policy objectives, such as ensuring a level of service accessibility for disabled passengers.

Source: OECD (2022[7]), OECD Handbook on Competition in the Digital Age, https://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/oecd-handbook-on-competition-policy-in-the-digital-age.pdf.

References

[14] Álvarez, D. (2022), El futuro incierto de las VTC en España a partir de octubre, https://capital.es/2022/06/13/vtc-futuro-incierto-espana/.

[8] Bekisz, H. (2021), “When Does Algorithmic Pricing Result In an Intra-Platform Anticompetitive Agreement or Concerted Practice? The Case of Uber In the Framework of EU Competition Law”, ournal of European Competition Law & Practice, Vol. 12/3, pp. 217-235, https://doi.org/10.1093/jeclap/lpab017.

[12] Castro, L. and J. Ramón Medina (n.d.), Supreme Court upholds restrictions on VTC (Spanish acronym of transport service through rented car with driver), https://www.osborneclarke.com/insights/supreme-court-upholds-restrictions-on-vtc-spanish-acronym-of-transport-service-through-rented-car-with-driver.

[11] Cluet Vall, A. (2019), VTC y taxis, historia de una batalla, https://www.elsaltodiario.com/uber/vtc-huelga-taxis-historia-batalla-falsos-autonomos.

[23] De Haldevang, M. (2018), Mexico City unveils first regulation on Uber in Latin America,, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mexico-uber-idUSKCN0PP2SU20150716.

[13] Estado, J. (2018), Real Decreto-ley 13/2018, de 28 de septiembre, por el que se modifica la Ley 16/1987, de 30 de julio, de Ordenación de los Transportes Terrestres, en materia de arrendamiento de vehículos con conductor, https://noticias.juridicas.com/base_datos/Laboral/629071-rdl-13-2018-de-28-sep-modificacion-ley-16-1987-de-30-jul-de-ordenacion.html#au.

[4] European Commission (2014), Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council on the State of the Union Road Transport Market, European Commission, https://ec.europa.eu/transport/sites/transport/files/modes/road/news/com%282014%29-222_en.pdf.

[15] Jiménez, M. (2021), Las VTC urgen a las comunidades una regulación del sector “para evitar su desaparición” en España, https://cincodias.elpais.com/cincodias/2021/10/18/companias/1634583413_485403.html.

[24] Love, J. and T. N. (2019), Uber, Didi slam Mexico City’s new rules on ride-hailing, including cash ban, https://www.reuters.com/article/mexico-uber-idINL1N2271D6.

[21] Mamdouh El Shiekh, S. and H. S. (2019), Egypt passes new regulations for ride-hailing apps, https://english.ahram.org.eg/News/351174.aspx.

[18] Menabytes.com (2018), Egypt approves law to regulate Uber, Careem and other ride-hailing apps in the country, https://www.menabytes.com/ride-hailing-law-egypt/.

[17] Menabytes.com (2018), Egyptian court orders Careem and Uber to halt operations in the country, https://www.menabytes.com/uber-careem-egypt-ban/.

[5] Ministry of Transport (2022), Tarifs du transport non régulier des personnes, http://www.transport.tn/fr/terrestre/article/378/tarifs-du-transport-non-regulier-des-personnes.

[10] Niblett, M. (2019), When regulation goes wrong: ride hailing in Spain, https://www.inlinepolicy.com/blog/when-regulation-goes-wrong-ride-hailing-in-spain.

[9] Noa, M. (2019), “Uber en España: Factores Sociales, Económicos y Políticos para Considerar”, https://repositorio.comillas.edu/xmlui/bitstream/handle/11531/27174/TFG-%20Noa%2CMaura.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y#:~:text=Uber%20llega%20por%20primera%20vez,siendo%20acusado%20de%20competencia%20injusta.

[7] OECD (2022), OECD Handbook on Competition in the Digital Age, https://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/oecd-handbook-on-competition-policy-in-the-digital-age.pdf.

[6] OECD (2020), OECD Competition Assessment Reviews: Iceland, OECD Publishing, https://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/oecd-competition-assessment-reviews-iceland.htm.

[1] OECD (2020), OECD Tourism Trends and Policies, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/6b47b985-en.

[2] OECD (2019), OECD Competition Assessment Reviews: Tunisia, OECD Publishing, https://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/ca-tunisia-review-2019-en.pdf.

[3] ONTT (2019), Rapport Annuel, https://www.ontt.tn/sites/default/files/inline-files/rapport2019.pdf (accessed on 8 Juin 2022).

[16] Oxford Business Group (2019), Egyptian market remains promising as ride-hailing services face new transport regulations, https://oxfordbusinessgroup.com/analysis/testing-ground-ride-hailing-services-face-new-regulations-promising-market.

[20] Riad-Riad (2018), New Law Regulating Ride-hailing Services, https://riad-riad.com/new-law-regulating-ride-hailing-services/.

[19] Sadek, G. (2019), Egypt: Ministerial Resolution Issued to Regulate Activities of Ride-Sharing Companies, https://www.loc.gov/item/global-legal-monitor/2019-10-22/egypt-ministerial-resolution-issued-to-regulate-activities-of-ride-sharing-companies/.

[22] Voanews (2018), Egypt Approves Law to Govern Popular Ride-Hailing Apps, https://www.voanews.com/a/egypt-law-ride-hailing-apps/4383613.html.

Notes

← 1. Law No. 2004-33 of 19 April 2004, on the organisation of land transport, as amended by Law No. 2006-55 of 28 July 2006.

← 2. See Law No. 2004-33 of 19 April 2004, on the organisation of land transport, as amended by Law No. 2006-55 of 28 July 2006. Article 3 gives definitions of public transport and private transport”. Public transport is defined as “any passenger transport service provided for a fee or offered to the public” and private transport is defined as “any transport of persons to which the definitions of public transport and tourist transport do not apply”. Article 14 provides that private transport is not subject to regulation.

← 3. Decree No. 2007-4101 of December 11, 2007, setting the terms and conditions for the issuance and granting of the professional card for public passenger transport and tourist transport.

← 4. Order of the Minister of Communication Technologies and Transport of 26 August 2004, fixing the distinctive marks of the vehicles assigned to the tourist transport.

← 5. These products are part of the detailed list of products excluded from the foreign trade freedom regime established by Decree No. 94‑1742.

← 6. Decree No. 2006-2118 of July 31, 2006, setting the conditions relating to the nationality and professional qualification of the person wishing to carry out one of the activities provided for in Articles 22, 25, 28, 30 and 33 of Law No. 2004-33 of April 19, 2004 on the organization of land transport as amended by Decree No. 2012-512 of May 29, 2012,and Government Decree No. 2016-1101 of 15 August 2016, Article 5.

← 7. Professional experience can be acquired abroad, for Tunisians and for citizens of countries that recognise experience acquired in Tunisia, on the basis of reciprocity.

← 8. See OECD, Competition Concerns in Labour Markets – Background Note by the Secretariat, 5 June 2019.

← 9. Law No. 2004-33 of 19 April 2004, on the organisation of land transport, as amended by Law No. 2006-55 of 28 July 2006, Article 32. Decree No. 2006-2118 of July 31, 2006, setting the conditions relating to the nationality and professional qualification of the person wishing to carry out one of the activities provided for in Articles 22, 25, 28, 30 and 33 of Law No. 2004-33 of April 19, 2004 on the organization of land transport as amended by Decree No. 2012-512 of May 29, 2012 and Government Decree No. 2016-1101 of 15 August 2016 is also relevant.

← 10. Law No. 2004-33 of 19 April 2004, on the organisation of land transport, as amended by Law No. 2006-55 of 28 July 2006.

← 11. Order of the Minister of Transport of 16 January 2020, approving the specifications for the exercise of the activity of rental of passenger cars, mixed cars and vans - (Cahier des charges – Voiture mixte, 2020). This cahier des charges replaced an earlier cahier des charges set out in the Order of the Minister of Transport of 5 February 2002 approving the cahier des charges for the operation of a car rental establishment.

← 12. Decree No. 2006-2118 of July 31, 2006, setting the conditions relating to the nationality and professional qualification of the person wishing to carry out one of the activities provided for in Articles 22, 25, 28, 30 and 33 of Law No. 2004-33 of April 19, 2004 on the organization of land transport as amended by Decree No. 2012-512 of May 29, 2012,and Government Decree No. 2016-1101 of 15 August 2016, Article 5.

← 13. Professional experience can be acquired abroad, for Tunisians and for citizens of countries that recognise experience acquired in Tunisia, on the basis of reciprocity.

← 14. . Decree No. 2006-2118 of July 31, 2006, setting the conditions relating to the nationality and professional qualification of the person wishing to carry out one of the activities provided for in Articles 22, 25, 28, 30 and 33 of Law No. 2004-33 of April 19, 2004 on the organization of land transport as amended by Decree No. 2012-512 of May 29, 2012,and Government Decree No. 2016-1101 of 15 August 2016, Article 4.

← 15. Order of 5 February 2002.

← 16. Article 1 of Decree‑Law No. 73‑13 defines a travel agency as any enterprise that carries out, on a permanent basis and for profit, any activity that involves selling to the public (directly or indirectly) on a flat-rate or commission basis, tours and holiday packages (individual or group), as well as any related service. Article 2 sets out the other activities of travel agencies, one of which is car rental. Travel agencies are subject to a cahier des charges and a prior declaration filed with the ONTT (Decree‑Law No. 73‑13, Article 3).

← 17. Al-Sabah News - President of the National Chamber of Car Companies for “Morning”: 66 companies closed their doors and 52000 cars prepared for hate outside the legal formulas. (assabahnews.tn).

← 18. See Law on providing services in tourism, chapter VI. Vehicle rental services, Articles 1 and 2.

← 19. Law No. 2004-33 of 19 April 2004, on the organisation of land transport, as amended by Law No. 2006-55 of 28 July 2006, Article 21.

← 20. Decree No. 2016‑828 increased this delay from one to two years.

← 21. Decree No. 2006-2118 of July 31, 2006, setting the conditions relating to the nationality and professional qualification of the person wishing to carry out one of the activities provided for in Articles 22, 25, 28, 30 and 33 of Law No. 2004-33 of April 19, 2004 on the organization of land transport as amended by Decree No. 2012-512 of May 29, 2012,and Government Decree No. 2016-1101 of 15 August 2016. Under the 2006 decree, non-regular public road passenger transport by taxi, rental and rural transport cars could be carried out by individuals or companies.

← 22. Decree no. 2007-2202 of 3 September 2007, on the organisation of non-regular public road transport of passengers.

← 23. Decree no. 2007-2202 of 3 September 2007, on the organisation of non-regular public road transport of passengers.

← 24. Applicants must provide a declaration of revenues and a sworn declaration that they are entirely devoted to the activity and are not an employee of the state, local authorities or public establishments or companies or, where applicable, an undertaking to resign from any such position.

← 25. Those present in the market before the introduction of the law in 2006 need not comply with the requirements, and any foreigners operating in the market before this time are exempt from the Tunisian nationality requirement.

← 26. These can be owned or leased vehicles. A company must obtain permission from the Ministry of Transport to add vehicles to its fleet.

← 27. The head office may be in a separate office on the premises that house the vehicles.

← 28. See Emissions standards for taxis - Transport for London (tfl.gov.uk), https://tfl.gov.uk/info-for/taxis-and-private-hire/emissions-standards-for-taxis#:~:text=On%201%20January%202018%2C%20we,age%20limit%20remains%20in%20place.

← 29. Applicants send a letter to the ministry, which has discretion, applying no objective criteria, to decide whether to approve their requests. Refusals are not uncommon and are fuelled by complaints from individuals who do not wish certain companies to increase their fleet sizes.

← 30. When a holder of a professional licence for taxi, louage or rural transport services changes their place of residence from one governate to another, they must seek a new licence. The area covered by the licence for individual taxi and grand tourisme taxi services will be the same as what was specified on the previous licence unless the applicant has a professional aptitude certificate that can cover a different service type.

← 31. Applicants must provide a sworn declaration that they are entirely devoted to the activity and are not an employee of the state, local authorities or public establishments or companies.

← 32. Category-B is for motor vehicles intended for the transport of people or goods with a maximum of eight seats, excluding the driver’s seat, and with a total permissible laden weight not exceeding 3 500kg. See Government Decree No. 2021‑510, which establishes licence categories, conditions for granting them, their validity and their renewal (articles 3 and 7).

← 33. Decree No. 2021‑510, which establishes licence categories, conditions for granting them, their validity and their renewal (Article 11).

← 34. Decree No. 2021‑510, which establishes licence categories, conditions for granting them, their validity and their renewal (articles 12 and 13). The duration of driving licences depends on their category and on the age of the applicant. For Category-B licences, the duration is as follows: under 60 years of age, 10 years; 60‑76, five years; 76 and above, three years). For Category-D and -G licences, the duration is as follows: under 60, three years; 60‑76, two years; 76 and above, one year. To renew licences, the requirements are not overly burdensome: the applicant needs only to provide the original licence and a medical certificate and pay the required fee.

← 35. If a certificate holder wishes to extend the zone of validity of the certificate or to change the zone to another area, they must apply again and sit a new exam.

← 36. See Victorian Taxi Association - TSC announces changes to vehicle age limits and specifications (victaxi.com.au), https://www.victaxi.com.au/news-and-events/news/2016/07/29/tsc-announces-changes-to-vehicle-age-limits-and-specifications/.

← 37. See Victoria Government Gazette No. S 284 Monday 28 September 2015, Transport (Compliance and Miscellaneous) Act 1983 Determination of Specifications for Taxi-Cabs, https://www.victaxi.com.au/assets/downloads/Old%20taxi-cab%20vehicle%20specification.pdf (previous version).

← 38. See Devenir chauffeur de taxi | entreprendre.service-public.fr, https://entreprendre.service-public.fr/vosdroits/F21907#:~:text=Vous%20voulez%20devenir%20chauffeur%20de,puis%20demander%20une%20carte%20professionnelle.