This chapter analyses food and beverage service, including tourist and traditional restaurants, street food and entertainment establishments. Local authorities play a central role in regulating and enforcing sanitary requirements. However, many businesses, such as tourist restaurants and entertainment establishments, are subject to additional restrictions imposed by a mandatory government classification process. Classification requirements include specific equipment and operational conditions. Selling alcohol at such establishments requires a specific licence whose issuance process lacks transparency and predictability, increasing costs for market participants and deterring entry. Further challenges are posed by the absence of an adequate framework for street food, encouraging informality and affecting consumer choice and overall welfare.

OECD Competition Assessment Reviews: Tunisia 2023

4. Food and beverage service

Abstract

4.1. Introduction

Food and beverage service is an essential part of culinary tourism, defined as the exploration of food for the purposes of tourism (Long, 2004[1]).1 The World Food Travel Association estimates that food and beverage expenses account for 15% to 35% of all tourism spending and 25% of added economic benefits for destinations (WFTA, 2020[2]). According to the Tunisian Tourism Satellite Account, food and beverage expenses accounted for 24% of all tourism spending in 2019. Four main types of food service exist in Tunisia: tourist restaurants; standard restaurants; traditional fast-food restaurants; and street food. The Office National Du Tourisme Tunisien (ONTT), or Tunisian National Tourism Office, regulates tourist restaurants at the national level since they are considered tourism investments, while traditional restaurants, fast-food restaurants and street food are regulated at the municipal level. All food providers are subject to sanitary regulations at the municipal level. This chapter analyses the main restrictions affecting restaurants and proposes policy changes and regulatory reforms to mitigate harm and enhance competitiveness and competition in the sector. Other entertainment establishments, such as bars and nightclubs, are analysed in detail in a spreadsheet published as a standalone document on our dedicated webpage, https://oe.cd/ca-tunisia.

Box 4.1. Countries’ approaches to fostering culinary tourism

In Hungary, the National Tourism Development Strategy 2030 adopted a destination-based approach in a project entitled “The Taste Map of Hungary”. Through dynamic food maps, tourists are able to search and filter local food and produce in a given region. The map helps to find distinctive and traditional tastes in various regions, driving tourism and supporting local supply chains.

Tourism and culinary experiences have been an integral part of Sweden’s food strategy since 2017. The government has also identified culinary tourism as priority for action within the EU Rural Development Programme, which has dedicated SEK 40 million to develop tourism in rural areas and SEK 60 million to develop culinary tourism in rural areas. The partly government-owned marketing company Visit Sweden AB works with Swedish regions to develop and market destinations’ culinary offerings.

Spain’s National Food and Wine Tourism Plan, part of a plan modernise and increase the competitiveness of the tourism sector, is funded to the tune of EUR 68.6 million, which includes tourism sustainability plans for food and wine destinations (EUR 51.4 million), the Spain Tourism Experiences Programme (EUR 10 million), and the International Promotion Programme (EUR 2.2 million). The plan aims to promote food and wine destinations by financing destination sustainability plans, generating sustainable and diverse gastronomic tourism experiences, and improving worker training and skills.

Sources: OECD (2020[3]), OECD Tourism Trends and Policies 2020, https://doi.org/10.1787/6b47b985-en; OECD (2022[4]), OECD Tourism Trends and Policies 2022, https://doi.org/10.1787/a8dd3019-en.

4.2. Tourist restaurants

4.2.1. Background

Tourist restaurants are authorised to sell alcohol and have longer opening hours (12pm‑5am) than other types of restaurants (12pm‑12am).2 Legislation provides for four categories of tourist restaurants, which are classified according to their physical characteristics, their facilities and the quality of their services:

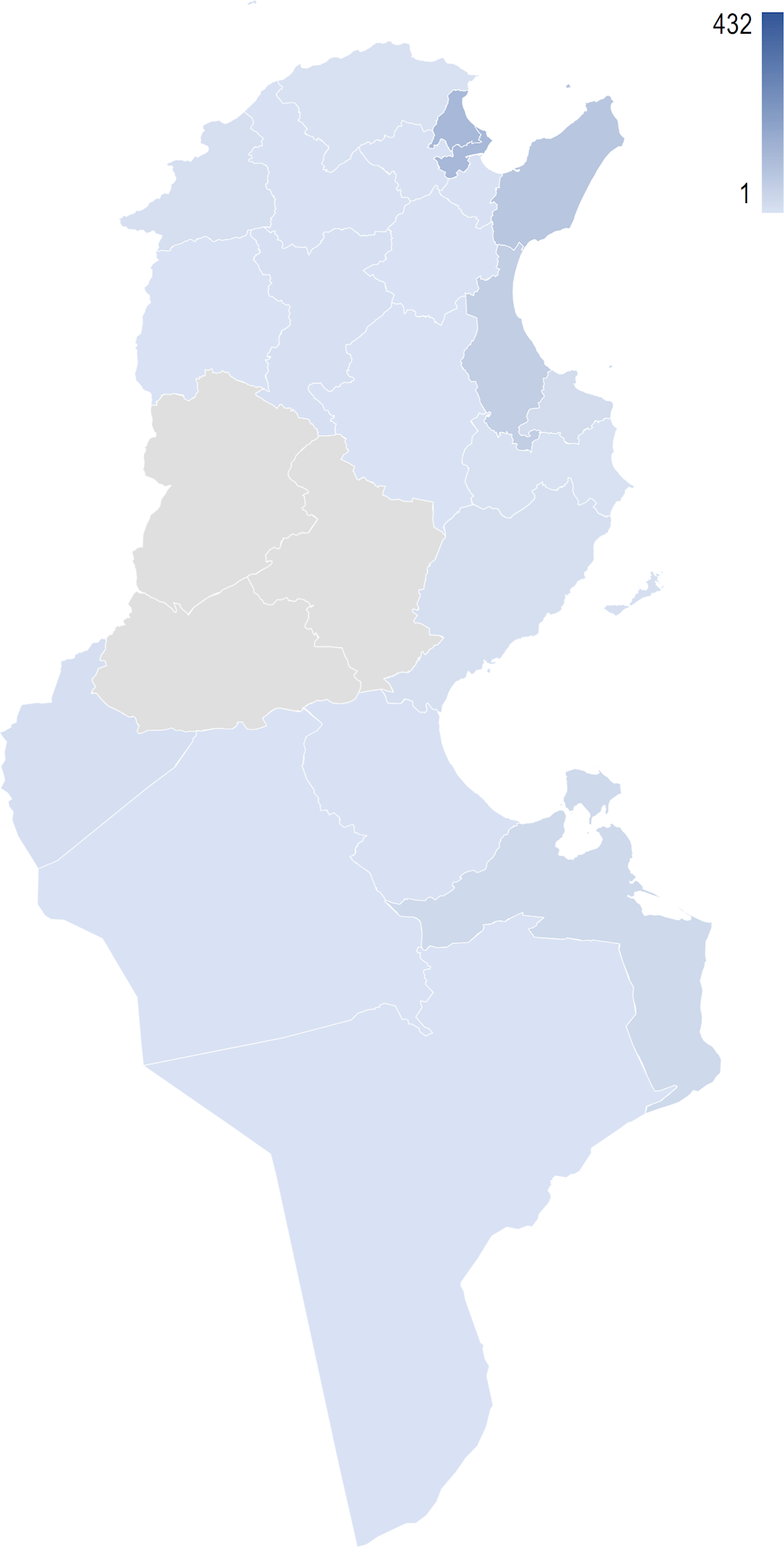

Figure 4.1. Tourist restaurants by region

Source: Adapted from ONTT (2020[5]), Tourisme tunisien en chiffres, https://www.ontt.tn/sites/default/files/inline-files/Extrait%20tourisme%20en%20chiffres%202020.pdf.

In 2019, the ONTT recorded a total of 374 tourist restaurants in Tunisia. Most tourist restaurants are concentrated in the country’s main tourism zones (see Figure 4.1). For example, one‑third of tourist restaurants were located in Tunis-Nord (125) in 2019. Other areas with relatively high number of tourist restaurants included Nabeul-Hammamet (77), Sousse (57) and Djerba (28). By classification, 147 were one‑fourchette restaurants, 185 were two‑fourchettes, 38 were three‑fourchettes and four were three‑fourchettes luxury.4

According to the ONTT’s 2020 annual report, 25 accords préalables, or prior agreements, and 12 accords définitifs, or final agreements, were granted for tourist restaurants (ONTT, 2020[6]). A prior agreement is an initial operating authorisation, and a final agreement is a definitive operational authorisation. The ONTT is also involved in the classification of tourist restaurants. In addition, ONTT inspectors at both the central and regional levels carry out inspections of tourist restaurants to ensure compliance with legislation. In 2020, the ONTT carried out 626 restaurant inspections (ONTT, 2020[6]).

4.2.2. Description of the obstacles and policy makers’ objectives

Classification process: According to Decree No. 89‑432, “restaurants which receive tourist customers and provide them with food and drink services, whether or not accompanied by leisure programmes, are considered to be tourist establishments”.5 In order for a restaurant to obtain classification as a tourist restaurant, its operator must file an application form to the director general of the ONTT before commencing operations. The OECD understands that an accord de principe, or provisional authorisation, is granted to allow such restaurants to operate. At the end of the first year of operation, restaurants may receive a final approval (see Section 3.2.2). The same process applies to entertainment establishments such as bars and nightclubs.

According to authorities, the classification system exists in order to encourage tourist restaurants to provide high-quality services, and to achieve ratings of two or more fourchettes. If they are able to achieve higher classifications, they are able to charge higher prices.

Classification requirements: Restaurants may apply for classification once they have received provisional authorisation. The Order of the Ministry of Tourism of 31 March 1989 provides that tourist restaurants must comply with a list of common requirements including health and safety conditions. In addition, they must offer services in line with their categorisation and ensure: 1) the cleanliness of their premises, furniture, various installations and all operating equipment; 2) the servicing and maintenance of all equipment; 3) the proper presentation of every dish; 4) compliance with recipes and quantitative standards (portioning) according to rules and practices accepted in the industry; 5) good conduct by staff; and 6) friendly, courteous treatment of customers. These conditions are not explained further.

Tourist restaurants must provide menus in Arabic, French and either German or English. The ministry order sets out very detailed and cumulative requirements for each classification. In order to obtain a one‑fourchette rating, for example, a tourist restaurant must meet certain minimum size, layout, functional and management standards. For example, the kitchen must contain certain equipment (cookware and utensils) and comply with certain safety conditions (such as being fitted with non-slip tiles and sufficient ventilation and lighting). The order sets out minimum management standards for kitchens, such as food safety, and minimum staffing requirements.

According to the authorities, these conditions uphold a certain level of quality, hygiene and safety. They aim to ensure consumer protection and to promote the image of Tunisian restaurants. The prescriptive requirements for each category also help inform investors wishing to open tourist restaurants about how to set them up. According to the authorities, the criteria are more indicative than prescriptive, so, for example, meeting 90% of the criteria is deemed adequate.

Classification commission: Classification decisions are made by the director general of the ONTT following consideration of a report by ONTT staff and after consulting a classification committee. The classification committee for tourist restaurants is chaired by the director general of the ONTT or their representative and includes a representative of the ONTT, a representative of the Fédération Tunisienne de l’Hotellerie (FTH), or Tunisian Hotel Federation, and a representative of the Fédération Tunisienne des Agences de Voyages et de Tourisme (FTAV), or Tunisian Federation of Travel Agencies. The Fédération Tunisienne Des Restaurants Touristiques (FTRT), or Tunisian Federation of Tourist Restaurants, is informally part of the commission but does not have voting rights. The commission is also in charge of classifying entertainment and musical tourism establishments.6

If the operator of a tourist restaurant wishes to apply for a different categorisation, they must make a new request through the same process.

In 2020, the classification commission met three times and studied 14 applications, resulting in confirmations of classification for three restaurants, reaffirmations of classification for six restaurants, provisional classification for one restaurant, prolongation of the duration of provisional classification for three restaurants and a rejection of a request for classification renewal for one restaurant (ONTT, 2020, p. 13[6]).

According to the authorities, the classification committee includes FTH, FTAV and FTRT representation because the associations have a good understanding of restaurants in Tunisia and are therefore well placed to decide on classifications. The decree does not include the FTRT, which is involved in order to defend the interests of its members, on the committee, but the authorities say the ministry decided to add it informally, and that giving it the right to vote would require an official amendment to the decree.

Withdrawal of classification: The director general of the ONTT may withdraw classification from a tourist restaurant or reclassify it in a lower category if it considers that the state of the premises, the equipment or the quality of the services it provides no longer corresponds to the category in which it was classified. In 2020, the ONTT cancelled the classification of three tourist restaurants (ONTT, 2020, p. 14[6]). In practice, this results in the sudden closure of the restaurant.

According to the authorities, this provision allows the ONTT to ensure that restaurants maintain the required standards (particularly in respect of hygiene, security and quality) and do not reduce their standards once they have obtained classification. The ONTT explains that classification may be withdrawn from a restaurant following a report by hotel inspectors from the Ministry of Tourism. In practice, the restaurant is first given a warning, and if it does not ensure alignment with its category, the inspectors send a report to the ONTT and the restaurant loses its classification. There are no public rules for this process, only internal rules. According to the ONTT, in 2016, 400 inspections were carried out and 90 restaurants ceased operations after being stripped of their classifications.

Licence to sell alcohol: According to Law No. 1959‑147, restaurants must obtain an authorisation to serve alcohol. The same rule applies to hotels and entertainment establishments. Legislation provides that these licences are issued by the Ministry of Interior following the opinion of the municipal authority and the territorially competent governor. An official request for a licence must be made at a local police station.7 It appears, however, from the ONTT’s 2020 annual report, that there is a special committee charged with overseeing files relating to the sale of alcoholic drinks in tourist establishments. This committee has five members from the Ministry of Interior, the Ministry of Tourism, the Ministry of Public Health, the Ministry of Social Affairs and the ONTT. According to the 2020 ONTT report, the committee made 65 site visits, reaching most regions, which resulted in the grating of alcohol licences for 32 establishments and the regularising of alcohol licences for 33 establishments (ONTT, 2020[6]). Stakeholders have complained that the process of obtain licences to sell alcohol takes too long and that the requirements are unclear.

According to Law No. 2004‑75, which abolished authorisations and revised administrative requirements relating to certain commercial, tourism and leisure activities, hotels with four or more stars and tourist restaurants with more than three fourchettes are not required to obtain an additional licence for the sale of alcohol, as required by Law No. 1959‑147. In practice, the OECD understands from some stakeholders that all restaurants are required to obtain a separate alcohol licence once they have obtained the right to operate through preliminary classification by the ONTT. Other stakeholders claim this is not required for restaurants with three‑fourchette luxury rankings, in line with the legislation.

The authorities argue that the licence requirement exists to control the sale of alcohol in hotels and restaurants for public health reasons and ensure that such establishments do not pose public order concerns. The OECD understands that hotels with four or more stars and tourist restaurants with three fourchettes need not hold licences to sell alcohol, given their nature and the importance of the investments involved.

4.2.3. Harm to competition

Classification process: Mandatory Government classification of tourist restaurants, whether in general or in relation to alcohol licences, does not appear to be a standard international practice and may limit competition. The classification system segments the market artificially and may also limit competition between different categories. The regulation tries to signal quality levels and protect consumers, but those signals may not correspond to reality as ratings are time‑bound and may not reflect a restaurant’s current quality. This artificial market segmentation can also affect prices, since higher-rated restaurants will charge higher prices even if their offering is the same as lower-rated establishments. Without the classification system, there might be limited substitution between restaurants of slightly lower and higher quality (for example, between one‑fourchette and three‑fourchettes establishments). With the system, there may however be some competition at the margins between adjacent classifications.

Box 4.2. Government classification systems for restaurants

The OECD has identified few examples of government classification systems for restaurants. One operates in Jordan, where in order to be licensed and classified as a tourist restaurant,1 the establishment’s operator must submit a number of documents and allow the restaurant to be inspected by a classification committee. The committee assesses the restaurant’s compliance with government specifications and determines its grade. It presents a report to the Tourism Committee that makes a decision on the restaurant’s classification and licensing. If the Tourism Committee approves the classification committee’s decision, the restaurant must submit several documents before the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities issues its tourist licence.2

Other majority-Arab jurisdictions, such as Abu Dhabi, do not operate a government classification system for tourist restaurants. Restaurants that wish to provide entertainment or artistic services must, however, apply for a specific licence.3

Most jurisdictions worldwide do not operate government-backed restaurant classification schemes. In France, for instance, the state‑driven star classification of restaurants was abolished in 1999. There is now a voluntary three‑tier scheme named the pyramide de qualité, or the quality pyramid, recognised by the government.4 There is also a voluntary classification process for tourist restaurants that sets out minimum standards.5 There are, however, no categories within this classification. Other famous restaurant classifications, such as the Michelin Guide and Gault et Millau, are not recognised by the French Government but are used by consumers to denote a certain standard of quality.6

Notes:

1. In Jordan, there are seven types of tourist restaurants including restaurants, cafeterias, rest houses, parks, amusement and recreation centres, and nightclubs.

Competition may be further limited by excessive requirements and the classification process as discussed below.

Classification requirements: Although some standards seem reasonable on hygiene and security grounds, others, for example on quality, may be set above what is required to address market failures resulting from information asymmetries between suppliers and customers. It is highly unlikely that tourists, and consumers in general, are familiar with the requirements imposed by the fourchette system. They are more likely to refer to online restaurant rankings by sources such as TripAdvisor and the Guide du Routard. A quick look at some of these platforms shows that the fourchette classification system has no impact on how customers perceive service, since some standard restaurants are better rated than two‑ and three‑fourchettes restaurants. In addition, standards regulating recipes, for example, reduce incentives to innovate and to cater to different and changing tastes and preferences among consumers.

The overly detailed requirements may raise the cost of market entry, discouraging potential entrants and reducing the number of participants in the market over time. They may also provide undue advantages to some suppliers, such as incumbents or large operators, over others, such as less well-resourced operators, and reduce innovation. Consumer welfare can be reduced by standards that are above the level that some well-informed customers would choose, as consumers are prevented from accessing cheaper, more innovative and differentiated services that they might prefer.

In addition to the prescriptive requirements, ambiguous standards, such as compliance with health and safety conditions in the absence of objective criteria (for example, references to legal documentation outlining such conditions) may deter entry due to legal uncertainty. In general, ambiguous conditions are also more likely to be applied differently between applicants on subjective grounds and can therefore distort competition.

Classification commission: The classification process may harm competition as incumbents, represented by the FTH, FTAV and FTRT, are involved in the process of classifying new restaurants and in reclassifying existing restaurants. The involvement of these three federations may lead to foreclosures of competition and conflicts of interest (many hotels, for instance, have tourist restaurants) and discriminate against new entrants and market participants not associated with the federations. This process may also interfere with feedback from customers and provide a potential means of co‑ordination between established restaurants. Another negative consequence could be the imposition of unnecessary administrative barriers due to a tendency to standardise interests and actions in cases where the members of federations may influence the attitudes of public authorities, and legislation and regulation, in their favour.

Withdrawal of classification: Ambiguous provisions with no objective criteria, or any criteria, for that matter, are more likely to be applied differently between applicants on subjective grounds and can therefore be a barrier to competition. Current classification withdrawal practices breed legal uncertainty, grant considerable discretionary power to civil servants and inspectors and are therefore harmful to competition.

Alcohol licences: These may increase costs for market participants, as they are first required to satisfy investment requirements regulated by the ONTT. They are then required to apply for classification as tourist restaurants. After this, they may apply for licences to sell alcohol. A lack of transparency surrounds the considerations involved in deciding on alcohol licence requests. It is therefore risky for businesses that there is no guarantee they will be granted licences, as alcohol sales may be essential to their business model (notably for restaurants, as it is a high-margin activity). The current licensing process could thus deter market entry by restaurants and hotels, discouraging competition. It may also increase costs for existing market participants, given the number of mandatory procedures.

4.2.4. Recommendations

In light of the harms to competition described above, the OECD recommends:

Abolishing the mandatory fourchette classification system for tourist restaurants.

In relation to classification conditions for tourist restaurants and entertainment establishments:

Abolishing requirements that go beyond considerations of hygiene, safety and consumer protection. Revising such requirements to ensure they are not more burdensome than is required to achieve underlying policy objectives.

Considering the transfer of specific size, layout and equipment requirements into an investor guide if the purpose is to help investors comply with standards.

Ending the involvement of incumbents in the tourist restaurant classification process. Alternatively, the OECD recommends the implementation of an ethical code of conduct establishing a complete, clear and accessible set of conflict rules to be followed by the federations if they are to be involved in decisions made by the committee (see Section 3.2).

Revising the regulatory inspection and enforcement framework in place. OECD’s Regulatory Enforcement and Inspections Toolkit provides useful guidance in this respect (OECD, 2018[7]).

Publishing clear publicly available rules for the withdrawal of classification for tourist restaurants. There should be clear escalating steps, such as fines and warnings, with withdrawal only as the final step. Appeal procedures should also be introduced.

Revising and streamlining the alcohol licensing process:

Abolishing the separate alcohol licence requirement and incorporating it into the investment procedure for hotels, restaurants and other food and beverage establishments.

Setting out clear rules for licences to sell alcohol and digitalising procedures so that applicants can apply online and are not required to go to local police stations.

4.3. Other food service operations

4.3.1. Background

Unlike tourist restaurants, standard restaurants, traditional fast-food restaurants and street food are regulated at the municipal level. Traditional fast-food restaurants include those providing different types of traditional dishes such as kaftaji (a dish of fried vegetables), brick (a stuffed filo pastry), lablabi (chickpea soup) and ftayer (a deep-fried doughnut). Street food includes a wide range of ready-to‑eat foods and beverages sold and sometimes prepared in public places, and it is very popular among tourists. The following requirements are based on those applied by the Commune of Tunis,8 which is subject to the Order of the Ministries of Interior and of Local Affairs of 17 August 2004, approving the cahier des charges, or set of specifications, relating to general conditions for business premises compliance. In the Commune of Tunis, traditional restaurants and traditional fast-food restaurants are subject to a cahier des charges detailing sanitary requirements.

All food service providers, including operators wishing to provide street food, must obtain a sanitary approval from the municipality in which they wish to operate and comply with the general sanitary regulation for food service providers. The Commune of Tunis also has specific sanitary regulations for premises handling specific types of food (for example, poultry, meat and fish) and for specific types of premises (for examples, cafes, bakeries and pastry shops) that are not reviewed in this assessment.9

Street food is not regulated by a cahier des charges. There are no specific authorisations or licence requirements for street food other than the sanitary agreement, but according to stakeholders, vendors are required to obtain an authorisation for the placement of their stands, caravans or trucks.

4.3.2. Description of the obstacles and policy makers’ objectives

Space allocation: Article 133 of the Règlement Sanitaire de la Ville de Tunis, or General Municipal Sanitary Regulation for the City of Tunis,10 requires that restaurant premises be organised in a certain way and specifies minimum space and layout requirements for different services and functions. For example, 50% of the total area should be reserved for customers, 25% for food preparation and cooking, 10% for food storage, 5% for employee clothing, and 10% for customer sanitary services such as toilets.

These minimum requirements are likely in place to ensure quality among food service providers and to promote the image of the industry.

Minimum requirements: Articles 69‑83 of the sanitary regulation detail general requirements for all types of food processing operations, including, for example, a minimum ceiling height of 2.8m and connection to public water and sewerage systems.

The regulation also sets out various minimum equipment requirements for restaurants, for example:

Article 134 of the regulation details the equipment required for space reserved for sales. This includes, for instance, a counter for preparing sandwiches, a refrigerated window (maximum 4°C) for perishable products, tables or counters for customer consumption and bins.

Article 135 details minimum equipment for kitchens and food preparation areas. Food service providers must have at least three washbasins with hot water to clean utensils, three washbasins to wash produce, a marble or stainless steel worktable and a hood, the height of which must exceed by at least 3m the roof of the highest buildings within a radius of 25m.

Article 136 lists equipment required for storerooms. Food service providers must have tiered cupboards that separate vegetables from other foods and a cold room whose temperature must not exceed 4°C for perishable products.

The OECD understands that these minimum requirements uphold a certain level of quality, hygiene and safety. They aim to ensure consumer protection and public health and to promote the image of Tunisian food service providers. The detailed requirements may help also new entrants establishing their businesses. The minimum ceiling height requirements are likely in place to ensure compliance with building safety regulations.

Placement authorisation for street food vendors: According to stakeholders, street food vendors are required to obtain the same placement authorisation required for newspaper or flower sellers (for kochk, or kiosks) from the municipality as per Article 74 of Law No. 2018‑29. This means they are required to locate their caravans or food trucks in a single designated space. The OECD understands that there is no regulation of other street food stalls, and that all stalls currently in operation selling dishes such as “Ayari and Mraweb” are running informally.

Authorities likely require vendors using caravans or trucks to obtain placement authorisation due to a lack of specific authorisations for such service providers. It is likely required to protect public order and hygiene by for example, preventing traffic disturbances and ensuring proper waste disposal.

4.3.3. Harm to competition

Space allocation: Limitations on the setup of food outlets may prevent innovation and the optimal use of resources. Some food service providers may sell various products, and when space available to store food is limited, the range of possible business models is also limited.

Minimum requirements: Although some standards seem reasonable on hygiene and safety grounds, others, for example concerning quality (such as how food service providers arrange their outlets) may limit choice, innovation and flexibility. This may raise the costs of entry for suppliers, discouraging potential entrants and reducing the number of participants in the market over time, with a potential impact on product variety. These standards may also provide an undue advantage to some suppliers, such as incumbents or large operators, over others, such as less well-resourced operators.

Placement authorisation for street food vendors: As is the case for almost all authorisations in Tunisia, the process of obtaining a placement authorisation from the municipality is lengthy and cumbersome. Once authorisation is obtained, caravans and food trucks must operate in the specific area designated in the authorisation, treating the business in the same way as if it were a permanent outlet. This prevents operators moving to different locations unless they can obtain several placement authorisations, which may significantly increase costs. It may reduce service providers’ ability to react to changes in demand by changing locations, which is part of the business model behind street food and food trucks.

In France, food trucks must obtain a carte de commerce ambulant, or street trading authorisation, which is renewed every four years. Operators must then obtain an authorisation for temporary occupation of a public area. There are three types of temporary occupation, depending on the location: a road permit; an installation permit; and a market permit. Depending on the type of authorisation sought, the applicant must contact different stakeholders (to park on a private road or area, they must contact the owner; to set up within a market, they must contact the town hall or organiser of the market; and to set up a food truck in a public space, with or without fixtures, they must contact the local town hall).11 As in Tunisia, food trucks in France are subject to the same hygiene rules as restaurants and other food service providers.12

Box 4.3. Street food in developing countries: lessons from Asia

The term street food describes a wide range of ready-to‑eat food and beverages sold and sometimes prepared in public places, unsurprisingly often streets. 1 Street food often reflects traditional local cultures and exist in practically endless variety. Vendors’ stalls are usually located outdoors or under roofs and are easily accessible from the street. Street food businesses are typically owned and operated by individuals or families, but the benefits of their trade extend throughout the local economy. For instance, vendors typically buy fresh food locally, potentially linking their enterprises directly with small-scale farms and market gardens.

The contribution of street food vendors to the economies of developing countries has been vastly underestimated and even neglected, although statistics for some places exist. In the Indonesian city of Bogor, sales of street food are worth USD 67 million annually. Malaysia’s estimated 100 000 street food stalls make annual sales worth USD 2.2 billion. However, the street food industry is merely tolerated in many countries. Because street food operations are spread over multiple locations and not systematically co‑ordinated in any way, it is common for clusters of vendors to be considered impediments to urban planning and hazards to public health.

Regulation can make street food safer. Once policy makers have decided that street food is here to stay, there are innumerable small ways to make life easier for both vendors and inspectors while ensuring that food is safer for consumers. Fair licensing and inspections, combined with education drives, are the best long-term measures to safeguard the public. Regulations for vendors should therefore be realistic, attainable and properly enforced; prohibiting the street food trade or imposing impossible requirements drives vendors to conceal unsanitary practices, eroding standards. Consumers’ needs should also be taken into account when establishing policies and regulations. Policies that help the street food trade benefit low-income consumers. For example, more licences might be issued for vendors selling low-cost, nutritionally sound foods or for those with good records of hygiene. Street food deserves the attention of policy makers, and vendors should be given opportunities to improve their situation and expand their enterprises.

Note: 1. This definition of street food was agreed upon by the FAO Regional Workshop on Street Foods in Asia, held in Jogjakarta, Indonesia, in 1986.

Source: FAO (1991[8]), Food, Nutrition and Agriculture, https://www.fao.org/3/u3550t/u3550t08.htm#TopOfPage

For other street food stalls, a lack of regulation means that operators provide services informally. This poses a major obstacle to promoting the sector, discouraging entrepreneurs from investing and improving the quality of their services and in so doing contributing to the promotion of local, traditional food. Most tourist apps and platforms recognise street food as a simple pleasure in many popular cities throughout the world. It is an easy way to eat on the go, and can sometimes showcase some of the best local cuisine a country has to offer at the lowest prices. In several countries, street food markets and popular night markets have become tourist destinations.13 In 2020, for instance, Singapore’s street food “hawker culture” was included on UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.14

4.3.4. Recommendations

In view of the restrictions above and their harm to competition, the OECD recommends:

Removing requirements beyond considerations of hygiene, safety and consumer protection from sanitary regulation. Requirements should be reviewed to ensure that they are not more burdensome than required to achieve underlying policy objectives.

Box 4.4. Singapore’s food safety licensing framework

The Government of Singapore in 2023 adopted a new food safety licensing framework to replace its annual grading system. Under the new framework, the Safety Assurance for Food Establishments (SAFE), food establishments are awarded bronze, silver or gold ratings, corresponding respectively to three‑, five‑ or 10‑year licence durations. Assessments are based on the operation’s track record, such as having no major food safety lapses over a period of time and being able to put in place systems to strengthen food safety assurance, such as the appointment of advanced food hygiene officers and implementing food safety management systems. To support and complement the SAFE framework, the Singapore Food Agency has established a comprehensive training framework targeting food handlers, food hygiene officers and advanced food hygiene officers.

Source: Singapore Food Agency (2023[9]), Safety Assurance for Food Establishment (SAFE) Framework, https://www.sfa.gov.sg/food-retail/SAFE-framework/safety-assurance-for-food-establishments-(safe)-framework.

For street food, the OECD recommends:

Considering other regulatory options for hawkers and vendors who wish to operate food trucks and not fixed shops, such as adapting specific areas or streets in cities, creating food courts, or granting temporary occupation authorisations for public areas.

Adopting clear and transparent licensing and enforcement frameworks.

References

[8] FAO (1991), Food, Nutrition and Agriculture, United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), https://www.fao.org/3/u3550t/u3550t08.htm#TopOfPage.

[1] Long, L. (2004), Culinary Tourism, p. 20, https://www.kentuckypress.com/9780813122922/culinary-tourism/.

[4] OECD (2022), OECD Tourism Trends and Policies 2022, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/a8dd3019-en.

[3] OECD (2020), OECD Tourism Trends and Policies, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/6b47b985-en.

[7] OECD (2018), OECD Regulatory Enforcement and Inspections Toolkit, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264303959-en.

[5] ONTT (2020), Le Tourisme tunisien en chiffres, https://www.ontt.tn/sites/default/files/inline-files/Extrait%20tourisme%20en%20chiffres%202020.pdf.

[6] ONTT (2020), Rapport Annuel 2020, https://www.ontt.tn/sites/default/files/inline-files/Rapport%20ONTT%202020.pdf.

[9] Singapore Food Agency (2023), Safety Assurance for Food Establishment (SAFE) Framework, https://www.sfa.gov.sg/food-retail/SAFE-framework/safety-assurance-for-food-establishments-(safe)-framework (accessed on 19 February 2023).

[2] WFTA (2020), Food Travel Monitor, https://www.worldfoodtravel.org/what-is-food-tourism.

Notes

← 1. Food tourism includes activities such as cooking classes, food and drink tours, food & beverage festivals, specialty dining experiences, specialty retail spaces, and visits to farms, markets and producers.

← 2. Article 1, Order of the Minister of Interior and Local Development of 15 August 2006, setting the opening hours of premises intended for the exercise of certain commercial, tourist and leisure activities. Modified by the Order of 8 November 2016 and the Order of 16 November 2018. If an establishment is located within a four‑ or five‑star hotel that is not opening onto public space, or in closed holiday villages, it is not subject to any limits on opening hours or the service of alcoholic drinks.

← 3. Decree No. 89‑432, relating to the classification of tourist restaurants (Article 2).

← 4. See ONTT, le tourisme tunsien en chiffres 2019, p.81.

← 5. Decree No. 89‑432, relating to the classification of tourist restaurants (Article 1).

← 6. In Tunisia, there are four types of musical tourist establishments: cabarets; nightclubs; discos; and musical tourist entertainment establishments. Beach bars and lounges are currently classified as tourist restaurants.

← 7. Article 7 of Law 59‑147, regulating drinking establishments and similar establishments, modified by Law 61‑55, Decree‑Law No. 74‑23, Law No. 93‑18, Law No. 2001‑27 and Law No. 2004‑75.

← 10. Règlement sanitaire de la ville de Tunis: http://www.commune-tunis.gov.tn/publish/images/citoyen/cahiers_charges/arrete_sanitaire.pdf

← 11. See https://www.legalstart.fr/fiches-pratiques/metiers-restauration/reglementation-food-truck/

← 12. See https://www.legalstart.fr/fiches-pratiques/metiers-restauration/reglementation-food-truck/ and https://www.legalstart.fr/fiches-pratiques/hotellerie-restauration/normes-hygiene-securite-sanitaire/

← 13. See, for example, https://gastronomerlifestyle.com/best-street-food-in-bangkok-2021/