Hotels, accommodation and well-being services account for the largest share of tourism revenues in Tunisia. Several regulations pose challenges to competition, business efficiency and growth. Complex licensing procedures, inflexible zoning policies and onerous operating requirements cause market distortions and affect market efficiency, especially for emerging alternative accommodation services, encouraging their informality. The direct involvement of some incumbent associations in several commissions dealing with the regulation and funding of important tourism activities affects market growth, deterring entry and limiting consumer choice. Conflicting provisions and an absence of adequate frameworks for some well-being services increase legal uncertainty and stifle investment. Against this backdrop, this chapter proposes reforms based on the OECD’s analysis and international experience.

OECD Competition Assessment Reviews: Tunisia 2023

3. Accommodation and well-being services

Abstract

3.1. Introduction

Accommodation is, by a long way, the most prominent sub-sector of the tourism economy (Cooper et al., 2005[1]). In Tunisia, tourist accommodation accounts for a large portion of overall tourism revenue. The sector comprises many forms of accommodation, including tourist and boutique hotels, apart-hotels, holiday villages, guesthouses and other lodgings. It also includes a significant number of informal enterprises offering alternative accommodation. This section explores how tourist investment and zoning policies affect market dynamics, and how the classification system for different types of accommodation and related requirements may constitute barriers to entry and create unjustified discriminatory treatment of different operators. The chapter also analyses issues affecting well-being services such as thalassotherapy, thermal and spa centres. Although these are regulated by the Ministry of Health, they are closely linked to the accommodation industry in Tunisia, since most such services are offered by hotels.

3.2. Accommodation services

3.2.1. Background

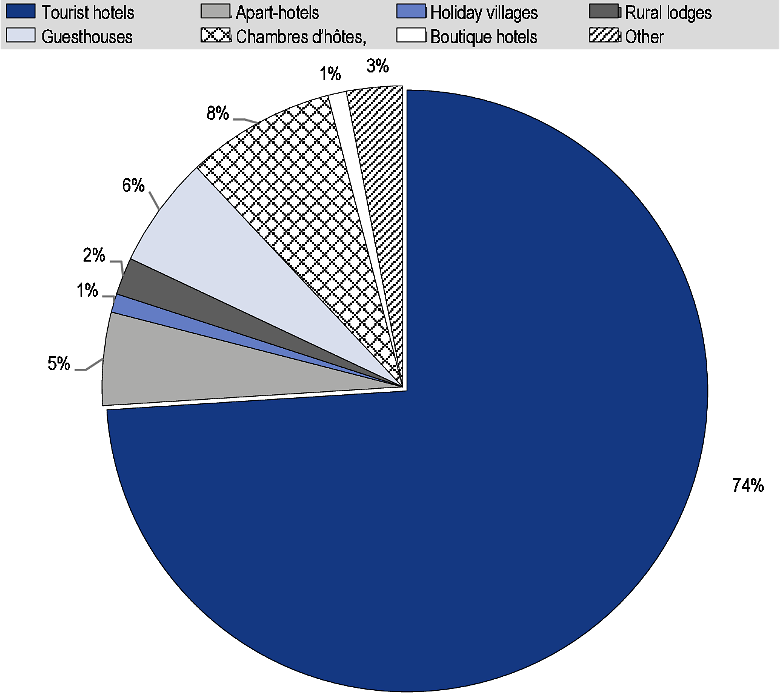

The classification system

Regulation classifies tourist establishments providing accommodation according to their characteristics, the quality of their services, and the facilities offered. According to Decree No. 2007‑457 (completed by Decree No. 2016‑335), accommodation is divided into ten categories: 1) tourist hotels; 2) apart-hotels; 3) villages vacances, or holiday villages; 4) motels; 5) guesthouses; 6) campsites; 7) boutique hotels; 8) gîtes ruraux, or rural lodges; 9) residences touristiques, or apartment residence complexes; and 10) chambres d’hôtes, or B&Bs (see Box 3.1 for more details). As of 2020, tourist hotels accounted for the vast majority of accommodation establishments (see Figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1. Accommodation establishments by category

Source: ONTT (2020[2]), Tourisme tunisien en chiffres, https://www.ontt.tn/sites/default/files/inline-files/Extrait%20tourisme%20en%20chiffres%202020.pdf.

Box 3.1. Types of tourist accommodation

1. Tourist hotels are defined by Article 3 of the decree as tourist establishments offering accommodation services in the form of rooms, suites or bungalows on a temporary basis. Tourist hotels must provide, according to their category, certain services and activities in common areas.

2. Apart-hotels are defined by Article 4 as tourist establishments offering temporary accommodation in the form of apartments or bungalows with kitchenettes. They must provide, according to their category, certain services and activities in common areas.

3. Villages vacances, or holiday villages, are, according to Article 5, tourist establishments that offer accommodation and entertainment services based on a range of sporting, cultural and recreational activities, subject to the rules of hotel management as determined by regulations.

4. Motels are defined by Article 6 as tourist establishments located on motorways or main roads with heavy traffic, intended to receive travellers and offering accommodation services as well as services such as petrol refuelling and breakdown services. Like apart-hotels and holiday villages, they are subject to hotel management rules.

5. Guesthouses, defined by Article 7, are tourist establishments offering accommodation services with limited capacity, built or equipped to provide tourists with accommodation and breakfast.

6. Campsites, under Article 8, consist of land for camping outside urban areas. Visitors may reside in tents that they bring, or which are provided on the spot, or which are pre‑installed, or in towed caravans. Campsites must provide a range of communal areas and services.

7. Boutique hotels, defined by Article 9, are tourist establishments in buildings or environments with specific architectural or touristic value. They offer guests personalised service and are subject to hotel management rules as set out by regulations.

8. Gîtes ruraux, or rural lodges, are, according to Article 10, tourist establishments located in rural environments with significant natural or cultural value. Aside from accommodation, rural lodges offer services aimed at enhancing the environmental value of the areas in which they are located.

9. Residences touristiques, or apartment residence complexes, defined by Article 11, are compounds in tourist areas that offer accommodation units for rent or purchase.

10. Chambres d’hôtes, or B&Bs, under Article 12, are accommodation units in which one or more of the rooms is made available to visitors by their owners or occupiers, and which offer accommodation and breakfast.

Source: Decree No. 2007‑457 (completed by Decree No. 2016‑335).

Two broad groups of tourist establishments exist in Tunisia: hotel-type accommodation that includes tourist hotels, apart-hotels, holiday villages, motels and boutique hotels, which are subject to hotel management rules; and alternative accommodation such as guesthouses, campsites, rural lodges and B&Bs, which operate under family management rules.

Informal accommodation

A notable feature of the Tunisian accommodation economy is the informality that characterises most alternative accommodation (see Section 2.2). Fewer than one in ten guesthouses, for example, are believed to be licensed.1

Several factors may contribute to this phenomenon. First, much informality seems to be related to the lengthy, burdensome administrative procedures involved in obtaining classifications and licences, which significantly hinder operators’ ability to access the market and create barriers to entry. This affects alternative accommodation much more than hotel-type establishments and leads to a difference in treatment that penalises alternative accommodation.

Second, a lack of certainty around tourism indicators, such as income, stays and revenue per visitor, creates a favourable environment for some tourist activities to remain hidden and potentially escape taxation.2 This applies to both hotels and alternative accommodation, but for alternative accommodation it is incentivised by the lengthy, burdensome administrative procedures required to operate formally in the sector.

Third, with digitalisation and the sharing economy being among the biggest drivers of tourism globally, the lack of regulation of peer-to-peer accommodation platforms, which are reported also to be used by some hotel owners and other tourist establishments,3 also contribute to informality.

Fourth, the banking system and exchange regulation may also foster informality among both hotels and alternative accommodation, due in particular to a prohibition on Tunisian residents opening and holding foreign currency accounts outside of Tunisia and strict requirements for opening foreign currency bank accounts. The annual thresholds for the sums of money that can qualify as allocation touristique, or a tourism cash allowance are also extremely low.4 A new Code des Changes, or Exchange Code, is supposed to enter into force in 2023.5

Box 3.2. International experience of regulating short-term rental accommodation platforms

The World Travel and Tourism Council’s Best Practices for Short-term Rentals report, published in July 2022 says:

“Empowering people to use their homes to earn extra income, short-term rentals have expanded participation in tourism, increased the quantity and distribution of available accommodation, and offered a new and different value proposition to travellers.”

The report established international best practices for governments across the world to manage the sector in a way that promotes tourism while also safeguarding local communities. Examples of short‑term rental platforms include Airbnb, Booking.com, Expedia and TripAdvisor.

Some of the main best practices are described below:

Digital registration. Some municipalities and large cities across the world, such as Sydney, Australia, and Raleigh, North Carolina, have developed digital registration processes in co‑operation with short-term rental platforms like Airbnb. A quick, straightforward registration system allows authorities to monitor the sector, adapting initiatives to trends while not overburdening owners or operators with excessive requirements.

Data sharing. Several local governments, such as those in Cape Town, South Africa, and Seattle, Washington, co‑operate with platforms for data collection to manage short-term rental activity and inform their decision-making.

Smart taxation. To ensure compliance with tax regulation, some governments have partnered with short-term rental platforms to facilitate the calculation, collection and retrieval of taxes. For instance, Estonia and Puerto Rico have entered into agreements with Airbnb to simplify tax declarations for owners and operators.

Restrictions on primary residence rentals to ensure long-term community investment. In order not to deplete the supply of accommodation in local communities and to strike the right balance between compliance with local regulation and the benefits of enhanced tourism activity, jurisdictions such as France set a limit on the number of days people can share their primary residences (in France, this is 120 days annually).

In November 2022, the European Commission adopted a proposal for a regulation to enhance transparency relating to short-term accommodation rentals, including the collection and sharing of data from hosts and online platforms. The proposal currently includes:

the harmonisation of registration requirements for hosts and their properties introduced by national authorities

the clarification of rules to ensure registration numbers are displayed and verifiable

the streamlining of data sharing between online platforms and public authorities

the collection and reuse of aggregate data for statistical purposes

the creation of an effective implementation framework.

Source: World Travel and Tourism Council’s Best Practices for Short-Term Rentals, July 2022, https://wttc.org/Portals/0/Documents/Reports/2022/Best%20Practices-%20Short%20Term%20Rentals.pdf?ver=2022-07-13-124741-227; Press release, Commission acts to promote transparency in the short-term rental sector to the benefit of all players, November 2022, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_22_6493.

3.2.2. Tourist investment and zoning policy

Description of the obstacles and policy makers’ objectives

Zoning policy: according to Article 5 of Law No. 90‑21 on Tunisia’s tourist investment code, tourist investments made in tourism zones determined by decree benefit from a number of advantages and a fast-track approval procedure by the Agence Foncière Touristique (AFT), or Tourism Real Estate Agency. Investments may also be made outside tourism zones, however, if, thanks to their geographical location and the ways in which they are used, they are likely to contribute to the diversification and enrichment of the tourism offer.

The zoning technique was adopted by the Tunisian Government to plan new tourism areas. The AFT,6 established in 1973, was, among other things, in charge of defining tourism zones, acquiring land and drawing up development plans for such areas. Tourism zones are therefore subject to a regulatory framework aimed at attracting investment that includes the following provisions:

Purchases of land in tourism zones does not require authorisation by territorially competent governors (Law No. 2005‑40, supplementing the decree of 4 June 1957).

Tourism zones benefit from fiscal advantages.

The price of land in tourism zones is fixed by the Ministry of Tourism in conjunction with the AFT and, from interviews conducted with the ministry, the OECD understands that it is below the market average (symbolic dinar per m²).7

Tunisia currently has some 22 tourism zones,8 although the tourism zone status of 16 other areas is provided for in law.

It should be noted that tourism zones aimed at attracting investment9 exist not only at the national level but also at the local level. Local level tourism zones aim to facilitate investment in areas of municipalities that are suitable for construction, ensuring compliance with overall urban development plans, planning requirements and land use priorities.10 In the 1970s, tourism development was focused on meeting burgeoning demand among tour operators with block hotels on the coast and shoreline. More attention was later paid to the creation of integrated resorts offering public spaces and entertainment facilities (Hellal, 2020[3]).

The role of the state in the centralised planning of tourist accommodation has diminished progressively, leaving more room for private investors. This change, combined with the global financial crisis of 2008 and the Covid-related economic crisis of 2020, required an adaptation of supply to demand. In this context, the zoning approach has progressively been superseded by more flexible flexible projets de station, or precinct planning, where development is entrusted to private operators.11

Authorisation process: Separately from zoning policy, Article 6 of Law No. 90‑21 specifies that any natural or legal person wishing to make a tourism investment with a view to creating, extending, transforming or developing a tourist project must obtain the prior authorisation of the minister in charge of tourism. The minister may delegate this power to the director general of the Office National Du Tourisme Tunisien (ONTT), or Tunisian National Tourism Office.

According to articles 7 and 8 of the law, prior authorisation is granted after the submission of a file including information on the location of the project, an architectural plan, and a financing scheme. It is provided within 30 days of the submission, and within one year of it being granted, a request for final authorisation must be submitted that includes a complete technical file approved by the ONTT and documents relating to the availability of funding. The file to be provided for accord préalable, or pre‑authorisation, must include:12

a request to the director general of the ONTT

a pre‑authorisation form (available from the ONTT’s Investment Promotion Directorate)

a project feasibility study

when a company is to be created, a draft of the bylaws establishing the company, and a list of backers.

The file to be provided for final authorisation (délivrance d’attestation de dépôt de déclaration d’investissement pour la réalisation d‘un projet touristique) must include:13

a written request to the director general of the ONTT

a copy of the register establishing the company

a list of the company’s backers

documents demonstrating the availability of 50% of the company’s equity capital

final agreements from banks for necessary loans for the project

an investment declaration form (available from the ONTT’s Investment Promotion Directorate).

The OECD understands that the authorisation regime is intended to provide the ONTT with all the information it requires concerning the construction or modification of tourism establishments, including on the availability of financing. It seems that it could also be useful given the many externalities associated with tourism, which create a need to oversee and manage areas in which it takes place at high intensity. According to authorities, the purpose of pre‑authorisation is to assist investors and increase the chances of obtaining final authorisation.

FODEC: The Fonds de Développement de la Compétitivité dans le Secteur du Tourisme, or Fund for the Development of Competitiveness in the Tourism Sector, established by Article 58 of Law No. 95‑109, has as its main objective support for advertising and promotional programmes for Tunisian tourism and all other activities to develop the competitiveness of the sector either directly or indirectly.

Article 60 of Law No. 1995‑109 provides that FODEC contributions are due at a rate of 1% on turnover made by the operators of tourism establishments as defined by legislation, and by operators of classified tourist restaurants. Contributions are collected based on a monthly declaration filed by the operators of tourism establishments.

According to Decree No. 2005‑2124, the FODEC’s management committee decides how to use the fund’s resources for advertising and promotional activities. The committee is composed of the minister of tourism or their representative as president, a representative of the Ministry of Finance, the director general of the ONTT, the president of the Fédération Tunisienne de l’Hotellerie (FTH), or Tunisian Hotel Federation, the president of the Fédération Tunisienne des Agences de Voyages et de Tourisme (FTAV), or Tunisian Federation of Travel Agencies, a representative of Restaurateurs Professionnels, or (the) Professional Restaurant Owners and Managers (Association), and a representative of Tunisair.

Harm to competition

Tourism investment and zoning policy: Tourism zones and other areas are treated differently in a number of respects due to the desire to attract investment. This has several implications.

First, investors’ choices are influenced by the zoning policy, which concentrates investments in specific areas, reducing the scope of tourism offerings and limiting consumer choice.

Second, the reduced bureaucratic requirements and preferential prices set by the Ministry of Tourism and the AFT create significant disparities between tourism zones and other areas that might have similar tourism potential but which are currently disadvantaged by the zoning system. For instance, the interior of the country, despite its tourism potential, remains marginalised and unable to attract investment. According to interviews with stakeholders, more than 90% of tourism investments in 2019 went to accommodation, 95% of which was concentrated in only three coastal cities and areas: Tunis, Nabeul and Djerba. This reinforces regional disparities between the coast and the hinterland.

Third, the zoning system fosters a mass tourism model concentrated in specific areas of the country and may contribute to Tunisia’s positioning as a low-cost destination, potentially jeopardising the growth of the industry compared with the sector in other emerging tourism destinations, such as China and India (Hellal, 2020[3]). Although the objective of attracting investment is extremely important and to be preserved, it should be attained without causing harm, and it should stimulate investment also in non-coastal areas for a more varied tourism offering. This is also important in light of the threats to the Tunisian tourism economy posed by coastal erosion, which risks affecting almost half of Tunisia’s beaches, according to the Agence de Protection et d’Aménagement du Littoral, or Coastal Protection and Planning Agency.14

Authorisation process: The use of a pre‑authorisation regime may result in different treatment of investors and suppliers in different areas and discrimination, because, with prior agreement, investors can secure: 1) options to land located in tourism zones; 2) the registration of a company’s constitutive acts, as well as acts establishing or confirming increases of initial capital, transformations of legal status, mergers and contributions for a period of 10 years from the date of notification of preliminary authorisation; and 3) deductions of income or profits reinvested in initial capital or in increases of this capital of up to 35%, 75% or 100%, according to circumstances, of their overall annual income subject to personal income tax or their profits subject to corporation tax.

The authorisation regime imposes a heavy administrative burden, creating an unnecessary barrier to investment in the country. The OECD understands that it remains unclear whether it will be replaced by a new procedure six months after the entry into force of Presidential Decree No. 2022‑317, and what this will look like.

FODEC: Levies may create distortions and competitive imbalances between various market participants. The existence of levies used for para-fiscal purposes was addressed in the OECD’s 2014 competition assessment review of Greece, as this was the case for the flour and cement sectors, among others, which financed pension and insurance funds for bakers and employees (OECD, 2014[4]). The OECD considered that not only did the “presence of such levies distort the market price” by increasing the costs faced by certain categories of operators, but that “it also skew[ed] the market in favour of some sub-groups relative to others”. The review concluded that the levy could reduce producer output due to higher costs, which translated into lower revenues and fewer jobs. The OECD recommended that any such levies be lifted (OECD, 2014[4]; 2019[5]).

In the case of the FODEC, market participants excluded from the management commission, such as the Fédération Interprofessionnelle du Tourisme Tunisien (Fi2T), or Inter-professional Federation of Tunisian Tourism, may face costs that help their prospective or existing competitors but does not provide them with any benefit. This might severely distort competition.

This tax, levied at 1% of the turnover of all tourist establishments, contributes to a fund for advertising and promotional programmes in the sector. The use of the funds collected is decided by a commission on which tourism stakeholders are not adequately represented. Consultation with stakeholders confirmed that, due to the non-inclusive composition of the commission, which does not provide for the participation of many of the associations and federations that are subject to the tax in the tourist sector, those associations and federations are never allocated the funds. In combination with the high level of discretion the commission enjoys, this may create significant competition distortions between market players.

Recommendations

Investment policy, zoning policy and authorisation process: Policy makers should weigh very carefully the benefits of using the zoning and pre‑authorisation systems to attract investment in accommodation against their costs. If facilitating investment in the sector remains a policy priority for Tunisia, the effectiveness of the restrictions described above in achieving these objectives should be carefully assessed to ensure that the favourable treatment enjoyed by areas defined as tourism zones does not discourage investment in non-coastal areas with high tourism potential. In this context, the OECD recommends:

Streamlining the licensing process for accommodation projects outside of tourism zones according to the best international practices for permitting and licensing (see Section 9.2) and consider revising the regulatory inspection and enforcement framework in place. OECD’s Regulatory Enforcement and Inspections Toolkit provides useful guidance in this respect (OECD, 2018[6]).

Revising the definition of tourism zones periodically to capture tourism trends, encourage visitor dispersal to support regional development, and ensure that no region is left behind.

FODEC: The OECD recommends:

Ensuring that decision-making on the allocation of the funds follows transparent criteria and is reserved to a commission composed to be representative of government only and not of selected stakeholders, or, as a less preferable alternative, made more representative of the various stakeholders.

Providing a strong governance code to prevent potential conflicts of interest for members and establishing an appeal procedure.

Lifting the 1% tax on the turnover of all tourist establishments contributing to the FODEC.

3.2.3. Classification and operational requirements

Description of the obstacles and policy makers’ objectives

As mentioned above, the system of classification of different types of accommodation is provided by Decree No. 2007‑456 (completed by Decree No. 2016‑335). Article 1 of Decree No. 2007‑456 lists ten types of accommodation: 1) tourist hotels; 2) apart-hotels; 3) villages vacances, or holiday villages; 4) motels; 5) guesthouses; 6) campsites; 7) boutique hotels; 8) gîtes ruraux, or rural lodges; 9) residences touristiques, or apartment residence complexes; and 10) chambres d’hôtes, or B&Bs. Article 2 of the same decree provides that orders of the Ministry of Tourism determine the minimum requirements for each category.

Classification and reclassification requirements and related commissions: All types of accommodation are subject to authorisation requirements in the form of a demand de classement, or classification request. According to Article 13 of Decree No. 2007‑456, the classification request must be addressed to the ONTT before the establishment begins operating.

Decisions on classification are made by the director general of the ONTT based on a dossier prepared by tourism administration officials in charge of inspections (les agents de l’administration du tourisme chargés de l’inspection) and after consultation with the Commission de Classement des Établissements Touristiques fournissant des Prestations d’Hébergement, or Classification Commission for Tourist Establishments providing Accommodation Services, as per Article 14 of the decree, composed as discussed below.

Requests for reclassification must be addressed to the Ministry of Tourism, according to Article 16 of the same decree.

Article 15 of Decree No. 2007‑456, completed by Decree No. 2016‑335, provides that the Classification Commission is chaired by the director general of the ONTT or their representative, and is composed of: a representative of the Ministry of Tourism; a representative of the ONTT; a representative of the FTH; and a representative of the FTAV.

Article 18 of the decree provides that the commission for revising the classification of tourist accommodation is chaired by the minister in charge of tourism or their representative and is composed of the heads of the ONTT, FTH and FTAV.

The OECD understands that the classification provisions and process are aimed at ensuring clarity and legal certainty for service providers so they know from the start what legal framework applies according to the type of accommodation they offer.

Some flexibility is provided, for instance, in relation to boutique hotels and B&Bs, but only for establishments whose construction is being planned, where the Commission Technique de la Construction des Établissements de Tourisme or Technical Commission for the Construction of Tourism Establishments, may, if it deems it useful, adjust minimum standards in view of the capacity, design and nature of the accommodation to be classified.

Minimum size, layout and functional requirements for classification: Regulation provides minimum size, layout and functional requirements are set out for hotel-type accommodation and alternative accommodation classification standards. Such requirements are not uncommon for hotel-type accommodation internationally in countries including Iceland (OECD, 2020[7]), Italy,15 Poland and Spain.16

The Annex to the Order of the Minister of Tourism of 29 July 2013 fixing such rules for boutique hotels, for example, provides minimum size, layout and functional criteria concerning room surface area, bed size and bathroom size.

More generally, the annex stipulates the size of reception areas (calculated at 0.50m2/bed), room equipment, the number of staff members in different functions (e.g. one chef, one pastry chef and one chef de brigade per 50 diners, and one waiter per ten diners in a restaurant). The annex also requires that staff (without further specification) must speak Arabic and three foreign languages, one of which must be English.

In relation to small-scale alternative accommodation such as guesthouses, rural lodges and B&Bs, however, classification requirements are very detailed, burdensome, and not necessarily linked to specific policy objectives. The classification system is also based largely on physical and technical criteria (for instance, the dimensions of guestrooms, reception rooms and dining rooms).

Box 3.3. Common international standards for four‑ and five‑star hotels

According to the Hotel Classification Systems report by the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), most classification systems rely on objective criteria such as the availability of specific facilities, equipment or services and/or size and layout criteria for rooms and spaces. The most common criteria for the European and global classification systems analysed relate to rooms, bathrooms, food & beverage offerings and services (albeit with different rankings).

In these categories, the most common criteria include:

Room

Telephone with external line

Desk, worktable, chair

one seat/chair per bed

Wardrobe or clothes niche

Reading light by each bed

Bathroom

Number of bathroom amenities

Percentage of ensuite bathrooms

Bathmat

Number of towels per person

Light over hand basin

Food and beverage offering

Dinner service restaurant

Room service breakfast

Room service offer

Beverage offer in lobby area

Breakfast requirements

Services

Fax availability

Wake‑up service

Laundry service

Hotel information

Internet available in public areas

Source: UNWTO (2015[8]), Hotel Classification Systems: Recurrence of Criteria in 4‑ and 5‑star hotels, https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/pdf/10.18111/9789284416646

For alternative accommodation, the Order of the Minister of Tourism of 29 July 2013 provides in Article 5, for example, that hosts should live with their guests, be considerate but not intrusive, and speak a foreign language in addition to their mother tongue. The host must also pay special attention to breakfast and to time for discussions and exchanges with guests.

Rural lodges are also subject to extremely detailed requirements17 (see Annex to the Order of the Ministry of Tourism of 1 October 2013).

The OECD understands that the size, layout and functional requirements for tourist accommodation in Tunisia aim to provide transparency and reduce information asymmetries between suppliers and consumers concerning the type and quality of services provided, enabling them to make better choices and enhance distributive efficiency.

Although strict, detailed requirements are widespread internationally for hotel-type accommodation, this is not the case for smaller-scale alternative accommodation such as B&Bs, guesthouses and rural lodges. For example, even if there is no worldwide standard for official hotel classification systems, and classification is wholly voluntary in some countries, there are considerable commonalities and recurrent criteria for different star categories across the world.18 According to the ONTT, minimum standards are applied by the Commission de classement des établissements touristiques fournissant des prestations d’hébergement) or Classification Commission for Tourist Establishments providing Accommodation Services (on the basis of common sense and pragmatism), but are not rigid.

Other capacity minimum and maximum limitations: These requirements are also linked to Tunisia’s classification system. For instance, there is a capacity minimum and limit for:

B&Bs – a maximum of five rooms for a maximum of 15 people19

Rural lodges – a maximum of ten rooms for a maximum of 30 people20

Rural lodges – a minimum area of 1 hectare or a minimum of 20 hectares when established on land subject to forestry regulations (with the lodge occupying a maximum of 1% of the forested area)21

Rural lodges – a maximum lodge height of 10m22

One‑star hotels – a minimum of ten rooms23

Boutique hotel – a maximum of 50 beds24

Campsites – a minimum area of 1 hectare.25

Capacity minimums and limitations can allow the classification of different types of accommodation. For example, a limited number of beds or rooms might help meet the personalisation of service requirement for B&Bs and boutique hotels. They can also be imposed for security and hygiene purposes, such as a maximum density of installations at campsites, or for biodiversity preservation, environmental protection and the promotion of local and homemade products.

Harm to competition

Classification and reclassification requirements and related commissions: The authorisation requirements for classification constitute a heavy administrative burden for smaller-scale alternative accommodation, operators of which benefit much less from classification than those of hotels (through, for example the easing of first-time consumer concerns, the provision of a framework for collective contracts, and support for marketing and promotion).26 Additionally, a lack of transparency relating to the development of the classification process grants considerable discretionary powers to officials, making outcomes less predictable and raising significant barriers to entry, for instance by creating uncertainty for businesses and investors and by discouraging private initiatives. It also incentivises informalisation.

From the OECD’s consultations with stakeholders, it emerged that the unbalanced composition of the classification commission (which involves only the FTV and the FTAV as tourism federations) and the reclassification commission may result in discriminatory treatment of alternative accommodation classification requests, with longer waiting times and greater uncertainty in terms of outcomes. In general, when market participants decide on matters involving their competitors, risks of foreclosure of competition emerge, alongside prioritisation of the interests of professional associations – especially at the expense of newcomers or so-called mavericks that compete aggressively – and possible exchanges of sensitive information between competitors. Another negative consequence can be the imposition of unnecessary administrative barriers due to a tendency to standardise interests and actions in cases where members of private associations may influence the attitudes of public authorities and legislation or regulation in their favour (OECD, 2016[9]).

Box 3.4. International best practices in hotel classification systems

The UNWTO’s Hotel Classification Systems report defines hotel classification as:

“The ranking of hotels, usually by using nomenclature such as stars (or diamonds), with one star denoting basic facilities and standards of comfort and five stars denoting luxury in facilities and services. The purpose is to inform intending guests in advance on what can be expected in order to reduce the gap between expected and experienced facilities and service delivery. The terms ‘grading’, ‘rating’, ‘classification’ and ‘star rating’ are used to refer to the same concept, i.e. to rank hotels by their facilities and standards.”

Looking at the recurrence of criteria in four‑ and five‑star hotels across 30 European destinations and six global destinations, the report finds that:

Hotel classification systems are widespread globally to address the information asymmetry between consumers and intermediaries, on the one hand, and owners and providers, on the other. They are commonly used as a marketing tool and as a proxy for assessing quality.

There are significant differences across hotel classifications, but notable commonalities between geographical groups (European and global) and star categories (four and five stars).

There are different types of classification systems:

traditional classification systems consisting of mandatory objective criteria, sometimes together with additional voluntary criteria (e.g. in Germany and India)

classification systems with International Organization for Standardization (ISO)-certified inspectors consisting only of mandatory criteria (France)

classification systems including quality assurance consisting of objective criteria and the assessment of the quality of some establishments (Scotland, Iceland and Australia)

classification systems including guest reviews consisting of guest reviews alongside mandatory criteria (Abu Dhabi)

trust-based systems consisting of criteria that are self-assessed by hotels (Slovak Republic).

Source: UNWTO (2015[8]), Hotel Classification Systems: Recurrence of Criteria in 4‑ and 5‑star hotels, p.14, https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/pdf/10.18111/9789284416646.

Minimum size, layout and functional requirements for classification: Although minimum size, layout and functional requirements for classification make classification easier and potentially more objective, insofar as they are based on quantifiable criteria, Tunisia’s current classification system is based largely on physical and technical criteria (for instance, the dimensions of guestrooms, reception rooms and dining rooms, or the number of staff and their linguistic skills).

This system does not guarantee the quality of services offered by hotels and alternative accommodation providers, and may give raise to discriminatory treatment between types of accommodation meeting the same standards but providing very different levels of service, skewing the playing field and stifling competition on merit by market players.

First, the system distorts competition between hotels and alternative accommodation, the latter being subject to extremely burdensome size, layout and functional requirements to obtain classification, but for which classification is not as customary or beneficial as hotel star classification systems. This results in several types of alternative accommodation suppliers being discouraged from applying for classification or operating informally, both of which distort and damage competition.

Second, and more generally relating to both hotel and alternative accommodation, minimum size, layout and functional requirements are often not necessary to reach any specific policy objective, so they do not satisfy the proportionality requirement (e.g. stringent language requirements for all types of staff, including non-customer-facing staff). These requirements are overall very detailed and onerous for all accommodation suppliers. When unnecessarily burdensome, they lead to potential restrictions of supply, potential increases in the cost of entry, and limits to innovation. Although some such provisions may aim to ensure security and hygiene, they also limit the number of suppliers, lead to market concentration and possibly higher prices, and restrict competition by reducing the range of alternatives that consumers might enjoy.

They also impose substantial barriers to growth and expansion by new entrants, and make it more difficult to switch to alternative forms of accommodation once a presence in the market has been established.

If unnecessary requirements are lifted, and criteria are formulated to ensure they reflect the actual quality of services provided, this may lead to more competition, more investment, lower prices and greater choice for consumers. This may also stimulate innovation and allow differentiation to meet consumer preferences.

Other capacity minimums and limitations: These requirements limit the flexibility of various types of accommodation providers that cannot easily innovate or diversify their offers but which tend to need to continue providing the services they meet the requirements for, presenting them with significant investment requirements and barriers if they wish to change.

In addition, legislation has created a gap in the classification system that makes it unclear which category an accommodation service offering more than five rooms but less than ten rooms in an urban area falls into, as it would not qualify as a boutique hotel or a rural lodge.

The gap is particularly serious given the lack of regulation of accommodation offered on peer-to-peer platforms such as Airbnb, TravelTodo and TunRooms, which may open the door to informal transactions.

According to stakeholders consulted by the OECD, the Ministry of Tourism is finalising a new set of requirements focusing on qualitative rather than quantitative criteria. At the time of writing, however, it was not known when the new cahier des charges, or set of specifications, will be published and what it will contain.

Recommendations

Classification and operational requirements: The OECD recommends revising requirements on classification and size/layout and functional requirements for hotels and alternative accommodation by:

Revising the membership of the classification and reclassification commissions to limit them to representatives of the administration, so as to avoid the exercise of influence by stakeholders or, as a less preferable alternative, make them more representative of all stakeholders. In this case, authorities should consider establishing a complete, clear and accessible set of conflict rules to be followed by professional associations. The implementation of an ethical code of conduct should be mandatory for each professional association involved in public decisions. The code of conduct should cover at least rules regarding the identification of what constitutes a conflict of interest (such as an expert who sits on a technical commission or committee controlling or analysing the issuance of a permit for a competitor), disclosure procedures, and the obligation to abstain from actively participating in authorities’ decision-making process in instances of conflicts.

Modifying the level of detail of the minimum requirements that need to be kept, ensuring they are reduced to the strict minimum necessary for the preservation of the public policy objective pursued, such as:

limiting language requirements for hotel staff only to staff that are in direct contact with guests

reducing room equipment requirements for rural lodges to a strict minimum and eliminating other equipment requirements (such as suitcase holders in bedrooms, soap dishes, wardrobes with personal lockers and bedside lamps)

eliminating requirements and limits that are not proportional to public policy objectives, such as:

minimum sizes for campsites and rural lodges

maximum room and guest numbers at B&B, rural lodges and boutique hotels

second-language requirements for B&B hosts

cohabitation requirements for B&B hosts.

3.2.4. Qualification and nationality requirements

Description of the obstacles and policy makers’ objectives

Managers’ qualifications: according to Order of the Minister of Tourism of 9 November 2006, relating to administrative services provided by the Ministry of Tourism and the enterprises and public establishments under its supervision, and the conditions for offering them, the responsibility for operating tourist accommodation must be entrusted to a manager who meets certain conditions of eligibility and specifications laid down by decree and who has received prior authorisation from the ministry. The terms of reference are approved by the Ministry of Tourism.

As established by Decree No. 2006‑2215, which sets out the qualification requirements for managers of tourist accommodation, any person wishing to act as the manager of a tourist accommodation facility must meet one of the following conditions:

1. Hold a higher education diploma from a course of at least four years or an equivalent diploma in one of the specialties of hotels and tourism, or in one of the specialties of economy and management, and have worked for at least three years in a tourist accommodation establishment, including one uninterrupted year in the position of manager.

2. Hold a higher education diploma from a course of at least three years or an equivalent diploma in one of the specialties of hotels and tourism, or in one of the specialties of economy and management; or hold a specialised technical diploma in one of the specialties of hotels and tourism delivered by a higher education institution in accordance with legislation and regulations; or hold a professional training diploma in one of the hotel and tourism specialties approved at the same level, and have worked for at least five years in a tourist accommodation establishment, including two uninterrupted years in a managerial position.

These requirements aim to ensure the quality and safety of accommodation services by placing them under the supervision of competent, experienced professionals.

Nationality requirements: According to Article 5 of Law No. 2016‑71, which sets out an investment code, investors are free to acquire, rent or exploit non-agricultural real estate in order to carry out or continue direct investment operations subject to compliance with the provisions of the Code de l’Aménagement du Territoire et de l’Urbanisme et des Plans d’Aménagement du Territoire, or Land Use and Urban Planning and Land Use Plans Code. This provision omits acquisitions of agricultural land, which may create uncertainty about whether non-Tunisian citizens can own and run rural lodges.

In addition, when a company structure is required or chosen by a tourist establishment, Article 6 of the same law provides that companies may recruit managers of any nationality up to a limit of 30% of the total number of executives until the end of the third year from the date of the company’s legal constitution or the date of the effective start of operations. This rate must be reduced to 10% from the fourth year. In any case, the company may recruit four managers of foreign nationality. It is possible to exceed the limit with an authorisation issued by the Ministry of Vocational Training and Employment.

The OECD understands that the main policy objective of the nationality requirement for owning agricultural land is to protect Tunisia’s agriculture industry by reserving ownership of such land for residents. The main policy objective of the nationality limit for managers is to create jobs by favouring the employment of Tunisian nationals.

Harm to competition

Managers’ qualifications: In many countries, hotel manager positions may be accessible simply after several years of experience in the accommodation industry, without specific qualification requirements provided by the law, but hotel managers in Tunisia are generally expected to have at least a bachelor’s degree and more often than not a master’s degree.27 Hotels have a very clear incentive to hire the best managers.

This, however, does not typically apply to alternative accommodation, which is often family-run. The provisions established by Decree No. 2006‑2215, which apply to both hotels and alternative accommodation, may therefore impose excessive requirements for managers of tourist accommodation, particularly since there is no distinction between classified hotel-type accommodation and alternative accommodation. The need for approvals of managers by the ONTT also constitutes a significant administrative burden for small-scale alternative accommodation operations such as B&Bs, guesthouses and rural lodges. These requirements may represent a significant barrier to entry for alternative accommodation, limit the range of potential suppliers, and incentivise informality. They may also lead to significant cost increases and discourage investors and their businesses, thus forming a significant barrier to market entry. They can also lead to discriminatory treatment of some suppliers against others that do not have to meet these requirements, such as campsites.

Owners of rural lodges and managers’ nationality: The nationality requirement for owning agricultural land could create discrimination between Tunisians and non-Tunisian citizens, and thus result in restrictions in the supply of rural lodges. The differential treatment of Tunisians and non-Tunisians aims to favour domestic employment and protect arable land and the agricultural sector more generally. Although it may be effective in helping to achieve that goal, in the tourism sector it may reduce the supply of accommodation and also positive spillovers and transfers of know-how from foreign talent and experience. The limitations thus imposed on the tourist accommodation industry do not seem justified by the objective of the law.

Box 3.5. Requirements for hotel and B&B management

Hotels

Although no legal requirements for hotel managers exist in many countries, such as France and Italy, hotel managers typically hold a three‑ or five‑year degree. Similarly, in the UK, these jobs are open to anyone, including candidates without a national higher diploma or degree, particularly if they have relevant experience. Some chains and luxury hotels may, however, tend to favour candidates with specific degrees, including in business, management, languages, hospitality management, travel, tourism or leisure studies.

For instance, one of the UK Automobile Association’s criteria for five‑star hotels includes “service and efficiency of an exceptional standard without detriment to other service areas at any time delivered by a structured team of staff with a management and supervisory hierarchy”.

Knowledge of multiple languages is also not mandatory, with the AA Quality Standards for Hotels requiring only that “where there is a market need, some consideration should be given to having multilingual staff” by five‑star hotels.

B&Bs

No education requirements exist for B&B owners in many countries, although it is sometimes required that owners satisfy specific moral requirements. In Italy, for instance, it is generally required that the owner, among other things:

1. has not been sentenced to a term of imprisonment of more than three years for a non-negligent offence and has not been rehabilitated

2. has not been convicted of a criminal offence against the state or the public order, or against persons when committed with violence, or for theft, robbery, extortion, kidnapping for the purpose of robbery or extortion, or for violence or resistance to authority.

Sources: Royal Decree of 18 June 1931, No. 773; Prospects, Job Profile, Hotel Manager, https://www.prospects.ac.uk/job-profiles/hotel-manager; UK Automobile Association, Ratings and awards, https://www.theaa.com/hotel-services/ratings-and-awards.

Recommendations

Qualification and nationality requirements: Qualification requirements may be maintained for hotel-type accommodation, but the OECD recommends eliminating the requirements for managers of tourist establishments in the following categories:

B&Bs

guesthouses

rural lodges.

The OECD recommends lifting or reducing the nationality requirement for managers in the tourism industry and for owners of rural lodges. This seems consistent with a recent update to the Law No. 2016‑71, which establishes the principle of freedom of investment and participation by non-Tunisian citizens in Tunisian companies. As an adherent to the OECD Declaration on International Investment and Multinational Enterprises, and according to its national treatment instrument, Tunisia is encouraged to ensure that Tunisian and foreign investors are treated equally.

3.3. Well-being services

3.3.1. Background

The well-being and hydrotherapy sector in Tunisia includes thermal cures, thalassotherapy and freshwater (spa) treatments. According to decree No. 2006‑3174, thalassotherapy is:

“a service that is both therapeutic, preventive and promotes well-being and health, using simultaneously, in a privileged marine site, under medical supervision and with the assistance of qualified staff, the elements of the marine environment, which are the marine climate, seawater, algae, marine mud, sands and all other substances extracted directly from it”.28

Thalassotherapy centres offer other services, such as sun therapy, hot sand therapy, water-based treatments such as balneotherapy in various forms (baths, rain and under water, for instance), and applications of seaweed and sea mud therapy.

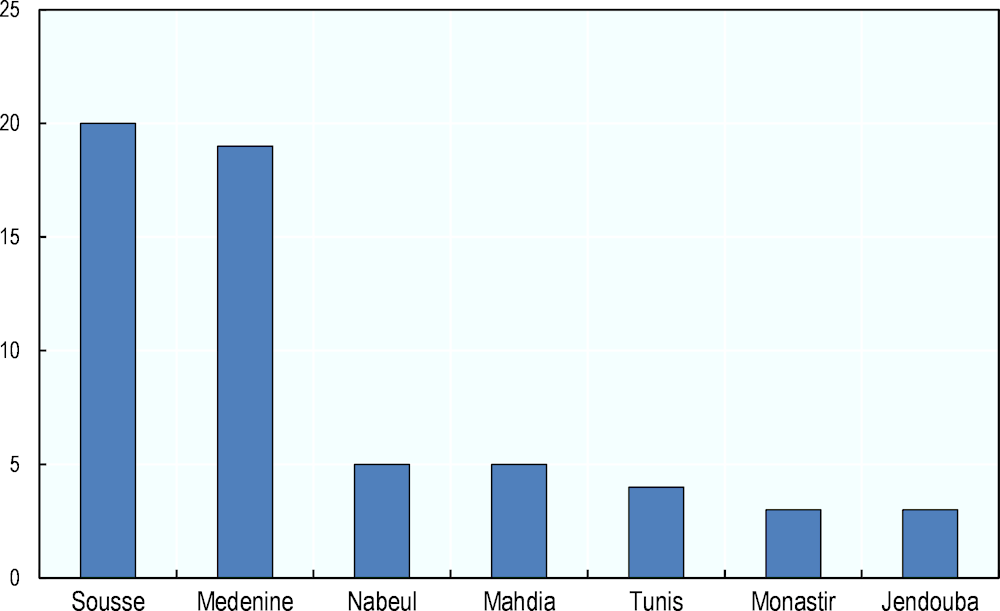

In Tunisia, thalassotherapy is linked mostly to hotels and tourist accommodation. According to the Office National du Thermalisme et de l’Hydrothérapie (ONTH), or National Office of Thermalism and Hydrotherapy, treatment not associated with accommodation comprises a maximum of 5% of thalassotherapy centres’ activities. The industry witnessed a surge since the 1990s thanks to a substantive increase in accommodation capacity. Currently, 59 thalassotherapy centres located mainly in Sousse and in the southern governorate of Mednine are in operation, with a combined daily capacity of 6 700 spa guests (see Figure 3.2). The Ministry of Tourism is responsible for granting authorisations to tourist establishments providing accommodation, setting out operating requirements and supervising them, but thalassotherapy is overseen by the Ministry of Health.

Figure 3.2. Thalassotherapy centres in Tunisia

Source: ONTH (2019[10]), L’hydrothérapie en chiffre, http://www.hydrotherapie.tn/portail-de-lhydrotherapie/base-documentaire/lhydrotherapie-en-chiffre/

The Order of the Minister of Tourism of 24 August 1999 defines thermalism as:

“The external or internal and simultaneous use in a privileged setting, under medical supervision, and for preventive and curative purposes, of the waters of a hot or cold mineral thermal spring as well as any other natural element (mud, clays, seaweed, other substances, and medicinal plants) matured or mixed with these waters.”29

In Tunisia, there are five thermal sites and 46 thermal hammams, or steam baths (see Box 3.6). According to the ONTH, two springs are in development and another two are undergoing evaluation.

Box 3.6. Thermalism in Tunisia

Tunisia currently has five thermal centres respectively located at the following sites: Korbous (Nabeul); Djebel Oust (Zaghouan); Djerba (Médenine); Hammam Bourguiba (Jendouba); and Boulaâba (Kasserine). Their combined capacity, turnover, employment and visitation figures are as follows:

Capacity of around 2 500 clients/day

Annual turnover of around TND 5 million

Direct employment of 525 people

Number of visitors in 2019: 47 244.

Tunisia also has 46 thermal hammams spread over 17 governorates:

Capacity of around 5 000 clients/day

Annual turnover of around TND 2.3 million

Direct employment of 300 people

Number of visitors in 2019: around 4.5 million.

Source: ONTH (2019[10]), L’hydrothérapie en chiffre, http://www.hydrotherapie.tn/portail-de-lhydrotherapie/base-documentaire/lhydrotherapie-en-chiffre/

According to ISO 17 679 for wellness spa services and the ONTT, a spa centre is.

“an establishment whose main activity is therapy with running fresh water. This activity is complemented by wellness services such as massage therapy, aesthetics and fitness.”

Tunisia boasts around 340 spa centres, which include spas in hotels and urban areas.30 According to the draft cahier des charges for spas, there are two types:

Centre Type‑A: Medicalised freshwater care centres whose activities involve medical treatment with fresh water and under the supervision of full-time medical staff

Centre Type‑B: Freshwater treatment centres for well-being and fitness care whose activities involve freshwater treatment using massage, beauty treatments and fitness care.

3.3.2. Description of the obstacles and policy makers’ objectives

Thalassotherapy centres

Authorisation requirements: Although Decree No. 2006‑3174 does not specify that authorisation is required to establish a thalassotherapy centre, Article 2 of Decree‑Law No. 2011‑52 stipulates that thalassotherapy is subject to authorisation by the ONTH. Decree No. 2006‑3174 and the annex included in Decree No. 2018‑41731 list requirements and obligations for investors establishing and operating thalassotherapy centres. Investors intending to start thalassotherapy centres must apply for an authorisation in a two‑step process:

In the first phase, investors provide several documents32 for preliminary approval by the ONTH’s technical committee. The technical committee for thalassotherapy centres studies the file documents and informs the applicant of any concerns. Once the committee is satisfied with the applicant’s responses to its queries, the file is considered complete and the committee has 30 days to decide whether to grant the applicant a preliminary approval.

During the second phase, investors submit several documents and technical studies.33 The committee issue a final authorisation if there are no outstanding concerns and if all legal and safety requirements are met. This process takes an additional month from the date of submission of the completed file.

Although the process and documentary requirements are set out in legislation, there is no justification for the two‑step approach and no clear evaluation criteria for reviewing applications. The OECD also understands that final decisions to issue authorisations may depend largely on the ONTH’s current development plans and strategies.

Following discussions with authorities, the OECD understands that the list of documents to be provided during the two phases aims to ensure that thalassotherapy centres protect the environment from pollution and degradation, and that they provide quality services. To achieve the environmental goal, the ONTH requires investors to provide an environmental impact study, a plan for the location of each thalassotherapy centre, and a location plan for the intake and discharge of used seawater. In addition, to obtaining final approval, thalassotherapy centres must guarantee the provision of good quality treatments, respect for hygiene conditions and quality standards, employ qualified and specialised personnel, and submit an agreement with an analysis laboratory to monitor the water used in treatments. These conditions aim to ensure the safety and preserve the health of the centres’ clients to develop the thalassotherapy sector, which attracts many tourists and represents a source of foreign currency. Although the documents and studies required are clear, the OECD understands that the discretion of the ONTH in final decisions ensures that centres are approved when in line with current government policies and strategies.

The authorisation process requires applicants to obtain several documents, approvals and licences from various ministries and organisations, including the ONTH, the ONTT, the Agence Nationale de Protection de l’Environnement (ANPE), or National Environment Protection Agency, and a laboratory recognised and authorised by the Ministry of Health.

The OECD understands that the involvement of several ministries and organisations in the process is required, given that it affects several policy areas including health, tourism and the environment.

Operational requirements: Decree No. 2006‑3174 sets out minimum requirements for thalassotherapy centres, including size, layout, functional and staffing standards:

Minimum size, layout and equipment requirements for baths, showers and care stations:34 Baths must be set up in individual cabins or boxes with at least 4m² of floor area and 3m in height, although a ceiling height of 2.6m is acceptable if adequate mechanical ventilation is provided. Large showers with a single nozzle or with alternating temperatures must be set up in cabins with an area of at least 10m². Individual care areas equipped with such facilities as sprays and aerosols provided in a shared space each require approximately 2m² of floor space.

Minimum staffing requirements: Thalassotherapy centres must employ the following staff: a physiotherapist for a maximum of 15 massages per day with a minimum of two physiotherapists per centre; a nurse; senior hydrotherapy and thalassotherapy specialists in sufficient numbers in relation to the number of treatment cabins, with a minimum of four per centre; a lifeguard; and a hygienist. In addition, all staff working at thalassotherapy centres must be employed full-time.35

Tunisian authorities confirm that these requirements comply with ISO standards and aim to ensure the quality of treatments offered to clients and the maintenance of health and safety standards. The minimum staffing requirements also comply with ISO standards and are in place to ensure the quality of treatments, mainly therapeutic care, whether curative, preventive or for health and well-being. This is also the rationale behind the requirement for full-time, qualified staff, which is regarded as a means of preserving customer health and hygiene. According to the authorities, all of these requirements aim to foster the development Tunisia’s thalassotherapy industry.

Thermal centres

Authorisation requirements: Although Order of the Minister of Tourism of 24 August 1999 does not specify that authorisation is required to establish a thermal centre, Article 2 of Decree‑Law No. 2011‑52 stipulates that the activity is subject to authorisation by the ONTH. The cahier des charges approved by the Order of the Minister of Tourism of 24 August 1999 lists the conditions for obtaining the approval to establish a thermal centre. Potential investors must follow a four‑step procedure that involves several approvals and requires documents from the ONTH, the ONTT and the Ministry of Agriculture, Water Resources and Maritime Fisheries. The process is long and cumbersome, with myriad pre‑authorisations and studies. It consists of:

A preliminary agreement, in which the investor should submit:

the name of the source or borehole that will supply the centre, and a determination of its thermo-mineral water needs

an application for a concession to exploit the waters of the source or authorisation from the Ministry of Agriculture, Water Resources and Maritime Fisheries, a request that must be accompanied by a hydrogeological study of the area and an environmental impact study

a preliminary study of the feasibility of the project, such as a market study and an explanation of its financing.

Prior authorisation, in which the investor should include:

a concession decree or agreement approved by the Ministry of Agriculture, Water Resources and Maritime Fisheries for the exploitation of water from the point requested.

The project preliminaries, which should include:

a layout plan of all offices and premises (for example, treatment areas, reception areas, waiting and relaxation areas, and pools)

a detailed plan of all levels and facades.

An execution agreement, comprising:

a full list of medical equipment.

A preliminary agreement will be approved only after an examination of the file by the ONTH, which submits it to a medical committee for final approval. The agreement must be confirmed by the Ministry of Tourism.

According to Article 11 of the cahier des charges, which sets out the standards and conditions for the establishment of thermal centres, the capacity of establishments must be proportional to the number of clients, their composition, and the variety and nature of the treatment services that they will offer.

Following discussions with authorities, the OECD understands that the lengthy licensing process is considered justified by the nature of the activity, which requires special attention, given its impact on the health of clients and on the availability of thermal and mineral water resources. The obligation to investors to submit several studies aims to ensure their credibility and transparency, and the highest compliance standards such as guaranteeing quality, ventilated spaces that allow good air circulation to ensure that space and capacity are adequate for the nature and the variety of treatment services. The authorities insist on the importance of ensuring the hygiene, safety, satisfaction and health of customers, and the provision of quality care and services to develop and promote hydrotherapy in Tunisia.

The OECD understands that the regulation of thermal activity involves multiple agencies, given its impact on policy areas such as health, tourism and the environment. The Ministry of Tourism, for instance, considers thermalism an important element to diversify the industry. The ONTH ensures compliance with hygiene and sanitary requirements in relation to premises and water sources to preserve the health of clients and limit contagion or disease. The Ministry of Agriculture, Water Resources and Maritime Fisheries is involved in the application for concessions and agreements to exploit water sources in order to preserve the environment and water resources.

Wellness spa centres

Authorisation requirements: Article 2 of Decree‑Law No. 2011‑52 stipulates that care activities involving fresh water are subject to authorisation by the ONTH. The OECD understands that a cahier des charges setting out general conditions for establishing and operating spa treatment centres is being developed and that a first draft is available. Although the draft cahier des charges sets out the documents and technical studies required for authorisation to set up a spa business, it does not contain clear evaluation criteria for the review of applications and does not set deadlines for authorities’ approvals, for example, in relation to the delivery of technical opinions on projects. 36

3.3.3. Harm to competition

Thalassotherapy centres

The imposition of multiple licensing steps to establish thalassotherapy centres has the cumulative effect of restricting entry and limiting the number of options available to domestic and foreign consumers in Tunisia. The absence of clear evaluation criteria increases significantly the discretionary power of the competent authorities and results in an uneven playing field. This can lead to arbitrary standards in decision-making, meaning that successful applicants may not be the most efficient, but may be successful in navigating the complex process. The risks of rent-seeking conduct are also pronounced. Given the length and costly nature of the authorisation process, the uncertainty around whether or not projects will be approved amid the lack of clear criteria and scope for official discretion may discourage investment and deter new entries, thus reducing competitive pressures, limiting consumer choice, increasing prices, and affecting product quality and consumer welfare.

The involvement of multiple ministries and authorities, alongside the lack of co‑ordination, may increase administrative burdens and create barriers to entry, restricting the number of market players and reducing competitive pressure on incumbents. Stakeholders noted that since most of the equipment required is sourced outside Tunisia, this situation is exacerbated by complex customs procedures and high import duties.

Although some standards seem reasonable on hygiene and security grounds, others, such as those involving quality, may be set above what some well-informed consumers would choose. These standards are, for example, more detailed than those set out in international standards (ISO 17680:2015).37 This may raise the cost of entry for suppliers, discouraging potential entrants and reducing the number of participants in the market over time. It may also reduce incentives for current operators to expand. Consumer welfare can be harmed by such exacting standards as consumers are prevented from accessing cheaper, innovative and differentiated services that they might prefer.

Thermal centres

The imposition of multiple permitting and licensing steps to establish thermal centres, especially those required at the same stage of the process, represents a considerable administrative burden and has the cumulative effect of restricting entry and limiting the number of options available to domestic and foreign consumers in Tunisia.

The involvement of multiple ministries and authorities, combined with a lack of co‑ordination reported by stakeholders, may increase administrative burdens and delay market entries. This raises barriers to entry, reducing the number of market players and reducing competitive pressure on existing players.

Conditions relating to the capacity of thermal centres are rather vague and ambiguous, which may increase the discretionary power of the competent authorities, create uncertainty for potential market entrants, and increase the risk of favouritism. Further, it could discourage investment and reduce the number of operators in the market and have a negative impact on the choice and quality of thermal treatments available to consumers.

Box 3.7. Thermal centres in France

According to the French Code de la Santé Publique, or Public Health Code, thermal establishments can exploit natural mineral water only for therapeutic purposes after obtaining authorisation from the territorially competent prefecture. Authorisations are based on an examination by an Agence Régionale de Santé, or Regional Health Agency, that includes the expertise of a hydrogeologist and the opinion of the Conseil Départemental de l’Environnement, des Risques Sanitaires et Technologiques, or Departmental Council for the Environment and Health and Technological Risks. In addition, the opinion of the Académie Nationale de Médecine, or National Academy of Medicine, may be requested by the Ministry of Health for any new request to operate a thermal establishment for therapeutic purposes or any new request for therapeutic orientation.1

The Public Health Code does not specify minimum requirements on the number of personnel, equipment or dimensions of baths and showers. It refers only to the concept of proportionality, meaning that staff, equipment and all services must be based on the maximum number of people that can be treated on site on the same day, depending on the size of the establishment, and its supply of mineral water. It specifies only the equipment that must be available at each thermal establishment necessary for each type of service, such as rehabilitation room equipment allowing the individual mobilisation of patients, necessary equipment for kinesi-balneotherapy services allowing mobilisation under water, and an examination room with at least one table that can potentially be used as an emergency treatment room. In terms of technical staff authorised to carry out rehabilitation, the code specifies that each establishment must include one or more physiotherapist masseurs, depending on the importance of the service. The number of operational staff should be merely sufficient and they need possess only the necessary skills.

Source: Articles L. 1322‑1 to L. 1322‑13; R. 1322‑1 to R. 1322‑44‑8; R. 1322‑45 to R. 1322‑67 of the Public Health Code.

Wellness spas centres

The absence of official regulation could lead to legal uncertainty for investors and affect the level of investment and development of Tunisia’s spa industry. The existence of several spa centres raises the question of whether they are subject to regular inspections, and, if so, on what basis. Authorities argue that the standard ISO 17679:2016 remains the reference until an official cahier des charges is adopted. However, stakeholders confirmed that the current draft cahier des charges is their reference, which increases legal uncertainty and makes them subject to authorities’ discretionary power. Stakeholders also noted that since most of the equipment they use is imported, this situation is exacerbated by complex customs procedures and high import duties.

3.3.4. Recommendations

The hydrotherapy sector is subject to regulatory provisions that are fragmented and, in some ways, inconsistent. The OECD recommends regulatory changes in order to minimise harm to competition and productivity, and to better contribute to achieving the desired policy goals. In particular, the OECD recommends that Tunisia:

Simplify and harmonise the regulatory framework for hydrotherapy (thalassotherapy, thermal cures and freshwater wellness) and remove contradictory legal provisions.

Streamline the licensing process for establishing and operating hydrotherapy centres according to the best international practices for permitting and licensing (see Section 9.2). Consider revising the regulatory inspection and enforcement framework in place. OECD’s Regulatory Enforcement and Inspections Toolkit provides useful guidance in this respect (OECD, 2018[6]).

Reduce the discretionary power of the competent authorities to approve hydrotherapy centre projects by publishing a transparent evaluation grid and clearly defining the conditions for granting authorisation to reduce uncertainty. Ensure that rejection decisions are subject to an appeal process.

Publish clear and binding deadlines for authorities to evaluate authorisation requests and issue opinions.

Simplify operational requirements by removing detailed provisions and refer only to ISO standards. Abolish the full-time staff requirement. Specific size and layout recommendations and suggested staff numbers might be transferred into an investor guide if the purpose is to help investors comply with standards.

References

[1] Cooper, C. et al. (2005), Tourism principle and practice, Prentice Hall.

[3] Hellal, M. (2020), “L’évolution du système touristique en Tunisie. Perspectives de gouvernance en contexte de crise”, Études caribéennes 6, https://doi.org/10.4000/etudescaribeennes.19397.

[7] OECD (2020), OECD Competition Assessment Reviews: Iceland, OECD Publishing, http://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/oecd-competition-assessment-reviews-iceland.htm.

[5] OECD (2019), OECD Competition Assessment Reviews: Tunisia, OECD Publishing, https://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/ca-tunisia-review-2019-en.pdf.

[11] OECD (2018), “Effective policy approaches for quality investment in tourism”, OECD Tourism Papers, No. 2018/03, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/88ea780c-en.

[6] OECD (2018), OECD Regulatory Enforcement and Inspections Toolkit, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264303959-en.

[9] OECD (2016), OECD Competition Assessment Reviews: Romania, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264257450-en.

[4] OECD (2014), OECD Competition Assessment Reviews: Greece, OECD Competition Assessment Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264206090-en.

[10] ONTH (2019), L’hydrothérapie en chiffre, http://www.hydrotherapie.tn/portail-de-lhydrotherapie/base-documentaire/lhydrotherapie-en-chiffre/ (accessed on 26 January 2023).

[2] ONTT (2020), Le Tourisme tunisien en chiffres, https://www.ontt.tn/sites/default/files/inline-files/Extrait%20tourisme%20en%20chiffres%202020.pdf.

[8] UNWTO (2015), World Tourism Organisation, Hotel Classification Systems: Recurrence of Criteria in 4- and 5-star hotels,, https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/pdf/10.18111/9789284416646.

Notes

← 1. Stakeholder interviews found, for instance, that at the time of writing, 78 B&Bs were operating with licences but that more than 800 were operating informally.

← 2. K. Jelassi, H. Sayadi, I. Hamrouni and I. Bliwa, “Grand Enquête – Tourisme de masse, Airbnb, maisons d’hôtes et autres : ces transations qui échappent à la Tunisie”, LaPresse.tn, 27.12.2021, https://lapresse.tn/119077/grande-enquete-tourisme-de-masse-airbnb-maisons-dhotes-et-autres-ces-transactions-touristiques-qui-echappent-a-la-tunisie/.

← 3. Ibid.

← 4. Ibid.

← 5. L’Économiste Maghrébin, “BCT : La Tunisie aura son nouveau code de change avant fin juillet 2022”, 20 Mai 2022, https://www.leconomistemaghrebin.com/2022/05/20/bct-la-tunisie‑aura-son-nouveau-code‑de‑change‑avant-fin-juillet‑2022/ ; Kapitalis, “La Tunisie promulguera un nouveau code des changes en juillet 2022”, 21 May 2022, https://kapitalis.com/tunisie/2022/05/21/la-tunisie-promulguera-un-nouveau-code-des-changes-en-juillet-2022/#:~: text=Le%20gouverneur%20de%20la%20Banque,de%20la%20rpercentageC3%A9glementation%20des%20changes.; Tustex, “Marouane El Abassi sur le nouveau code des changes: les conditions actuelles ne sont pas propices à la convertibilité totale”, 17 June 2022, https://www.tustex.com/economie-actualites-economiques/marouane-el-abassi-sur-le-nouveau-code-des-changes-les-conditions-actuelles-ne-sont-pas-propices-a.

← 6. The AFT’s mission is to: 1) acquire land in tourism zones; 2) proceed to the clearance of the land included in the perimeters of intervention; 3) carry out development plans and land reorganisation in the area with the aim of creating serviced lots; 4) build the necessary infrastructure; 5) put the lots up for sale for the development of tourism projects; and 6) ensure land reorganisation and the transfer of property titles to investors.

← 7. The method of calculating the cost price is part of the policy of encouraging the state to invest in tourism and takes into consideration the importance of the funds committed by the promoter, the jobs generated by the project, and its macroeconomic effects. It is not analogous to ordinary market prices.

← 8. Completed tourism zones include Bizerte, Cap Gammarth, Chaffar, Chott Ennassim, Douz, Hammamet Yasmine, Jerba, Jerba Houmet Essouk, Kebelli, Kelibia La Blanche, Kerkenah Sidi Fradj, Mahdia, Monastir, Nabeul-Hammamet, Nefta, Skanes Monastir, Sousse, Tabarka, Tozeur, Tunis North, the Coasts of Carthage, South Tunis and Zarzis.

← 9. For a discussion on tourism investment, please also see OECD (2018[11]).

← 10. The main local tourism zones are:

Tunis, la Marsa, Hammamet, Nabeul, Sousse Hammam-Sousse, Kairouan and Djerba Houmt.

Souk, Djerba-Midoun, Zarzis, Monastir, Mahdia, Tabarka, Tozeur, Nafta, Kébili and Douz.

Djerba-Ajim, Ain Drahem, Sidi Boussaïd and Kélibia.

Kerkennah, Carthage, Sahline and Sidi Ameur.

Akouda, Bouficha, Bizerte, El Jem and la Vielle Matmata.

La Goulette and Le Kram, Tataouine and Elktar.

El Kef, Sfax, Tamaghza, Sbeitla and Makthar.

Chenini Nahal and El Hamma, Bardo and Bengardene.