Cultural activities are considered as an essential part of the tourism diversification efforts recently made by Tunisian authorities. Heritage concessions are at the centre of these efforts, and represent one of the main means of ensuring better management of 3 000‑plus historical and archaeological sites nationwide. Despite the existence of a relatively clear and conducive framework, the development of heritage concessions is hindered by several obstacles, including institutional conflicts of interest. This chapter addresses restrictions on the establishment of private museums, galleries and art workshops. The introduction of notification procedures for these activities falls short of the expected outcomes as the regulations still include several barriers to entry, such as specific equipment requirements, professional qualifications, corporate legal structures and minimum levels of capital.

OECD Competition Assessment Reviews: Tunisia 2023

7. Cultural services

Abstract

7.1. Introduction

The cultural and creative industries are a significant source of jobs and income. They are a driver of innovation and creative skills, within these industries and beyond (OECD, 2022[1]). Cultural tourism, defined by the World Tourism Organization as tourism centred on cultural attractions and products, is one of the fastest-growing segments of the tourism industry, accounting for an estimated 40% of all tourism worldwide (UNESCO, 2021[2]). It includes heritage and religious sites, crafts, performing arts, gastronomy, festivals and special events, among other things. The cultural and creative sectors can directly feed into activity in the tourism sector, such as hospitality, accommodation and travel, and can be harnessed to promote more sustainable tourism (OECD, 2022[3]).

Tunisia has a rich cultural history and is home to eight sites that feature on the UNESCO World Heritage List, including the archaeological sites of Carthage, Dougga and Kerkouane, the Amphitheatre of El Jem, the Medina of Tunis, the Medina of Sousse and the Medina of Kairouan, in addition to the Ichkeul National Park, a natural World Heritage site.1 Tunisia is home to 35 public museums: 23 historical and archaeological museums; ten museums of art and popular tradition; and two contemporary history museums.2 The Bardo National Museum, the Carthage National Museum and the Sousse Archaeological Museum are Tunisia’s most famous museums. Entrance fees for public museums are set by the Ministry of Culture.3 Until recently, the Agence de Mise en Valeur du Patrimoine et de Promotion Culturelle (AMVPPC), or Agency for Heritage Development and Cultural Promotion, had a monopoly on managing and overseeing museums, historical sites and archaeological sites, and heritage concessions did not exist.

This chapter analyses recent developments in this field and issues related to the establishment of private museums, galleries and art workshops. Other types of cultural services, such as producing and marketing historical and archaeological goods, are analysed in a spreadsheet published as a standalone document on the dedicated OECD webpage, https://oe.cd/ca-tunisia.

7.2. Heritage concessions

7.2.1. Background

The Institut National du Patrimoine (INP), or National Heritage Institute, publishes a map of archaeological sites and historical monuments in Tunisia.4 The Code du Patrimoine Archéologique, Historique et des Arts Traditionnels, or Code on Archaeological, Historic and Traditional Arts, defines several types of cultural heritage sites:

Cultural sites are defined as man-made, or natural and man-made, and include archaeological sites that have national or international value from the point of view of history, aesthetics, art or tradition.5 Cultural sites are classified by a joint order of the minister of culture and the minister of town planning following consultation with the INP.6

Historical monuments are defined as immovable property, built or not, in private or public areas, the protection and conservation of which has national or international value from the point of view of history, aesthetics, art or tradition.7 Historical monuments are subject to a protection decree issued by the minister responsible for heritage on their own initiative or on the initiative of any person with an interest and following consultation with the INP.8

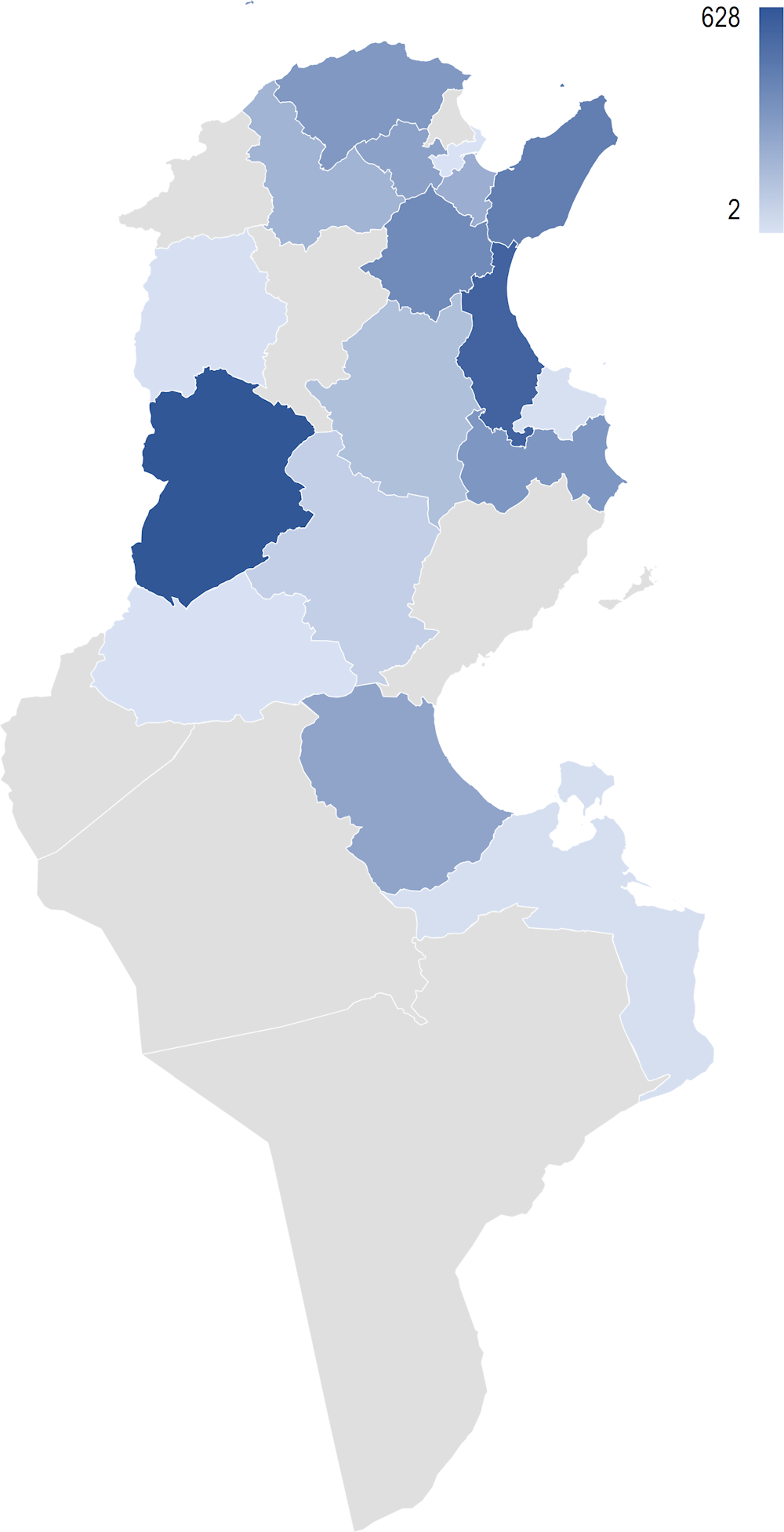

The National Heritage Institute assessed over 3 000 archaeological sites and 1 300 archaeological monuments countrywide (INP, 2023[4]).

Figure 7.1. Archaeological sites and monuments by region

Source: OECD based on INP (2023[4]), Base de données de la carte archéologique, https://www.inp2020.tn/projets/carte/_data_base_sites_monuments/

7.2.2. Description of the obstacles and policy makers’ objectives

In Tunisia, the granting of concessions is regulated by Law No. 2008‑23, which applies to all sectors in which no specific sector laws govern concessions. Following the adoption of Law No. 2019‑47 on the improvement of the investment climate, which amended Law No. 2008‑23, the AMVPPC was empowered to grant concessions for cultural and archaeological sites.9 However, the agency did not make use of this new mandate, despite growing interest among private investors.

It is noteworthy that the agency has many regulatory functions, such as granting licences and approvals, and manages sites, museums and monuments itself. Article 3 of Law No. 1997‑16, amending Law No. 1988‑11, which created a national agency for the development and exploitation of archaeological and historical heritage, explains that the agency is funded through cultural events it organises and entrance fees to monuments, cities and museums, income from the agency’s heritage other or property assigned to it, and income from archaeological monuments, sites and museums.10

Box 7.1. Tunisia’s concessions system

The Tunisian general concessions system is defined by Law No. 2008‑23, amended by Law No. 2019‑47.1 According to Article 2 of the law, a concession is “a contract by which a public person designated a ‘grantor’ delegates, for a limited period, to a public or private person designated a ‘concessionaire’, the management of a public service or the use and operation of public areas or tools in return for remuneration that it collects from users for its benefit under the conditions set by a contract. The concessionaire may also be responsible for construction related to, and modification or extension of constructions, works and installations, and for acquire necessary goods to fulfil the purpose of the contract. The contract may authorise the concessionaire to occupy parts of the area belonging to the grantor to build, modify or extend constructions, aforementioned works and installations”.

Note: 1. As amended by Law No. 2019‑47, relating to the improvement of the investment climate and Law No. 2021‑9, relating to the approval of Decree‑Law No. 2020‑24, as well as the regulatory texts adopted for its application, in particular Decree No. 2020‑316, laying down the conditions and procedures for granting concessions and their monitoring. Law No. 2008‑23 is considered the fundamental legal framework governing concessions in Tunisia. The provisions of the law are applicable to all concessions granted, without prejudice to specific sector texts and provisions governing concessions (Article 43).

Source: Law No. 2008‑23.

Tunisian authorities informed the OECD that heritage concessions are a top priority for the country. Several international partners, including the EU and French international technical co‑operation agency Expertise France, are providing financial and technical support to unlock this potential. The OECD understands that the AMVPPC’s involvement in the process of granting heritage concessions is important since it aims to ensure the consistency of the national strategy for the restoration of architectural integrity, the safeguarding of heritage authenticity, and the conversion to new functionalities, allowing the exploitation of monuments for cultural and tourism purposes.

7.2.3. Harm to competition

The involvement of the AMVPPC in the concession process creates a conflict of interest. The agency currently has a monopoly on the management of historical and archaeological sites, and these operations are the main source of its budget. Granting concessions at some of these sites would potentially reduce the agency’s revenues, as it may not benefit directly from concession fees. In addition, to the extent that sites operating under concessions compete with those managed directly by the agency, the agency would also face the potential of further revenue reductions if tourists switched to competing sites. This could result in unfair or anti-competitive outcomes through discrimination against new entrants and lead to reduced market entry.

Despite the AMVPPC’s reluctance to grant heritage concessions, the first concession contract was signed in December 2021 for the restoration of the El Karaka site in the Tunis municipality of La Goulette, and its transformation into a museum of artisanal ceramics. Other contracts are being finalised, including for the restoration and use of the 14th century Casino de Hammam-Lif. These contracts were made possible through memorandums of understanding signed between the Instance Générale de Partenariat Public Privé (IGPPP), or General Public-Private Partnership Authority, the Ministry of State Property and Land Affairs, and the INP. The memorandums also enabled the development of model contracts to help promote heritage concessions, especially with local municipalities.

Stakeholders told the OECD that the reluctance of the agency to grant heritage concessions thus far and its lack of engagement in recent operations are clear indicators of the conflict of interest. The status quo may hinder the development of this market in the long run and could pose a serious challenge for attracting the private investment needed to promote numerous historical sites that are currently practically neglected. Various stakeholders confirmed that the AMVPPC lacks the human and financial resources to ensure proper management of Tunisia’s 4 000‑plus historical and archaeological sites.

7.2.4. Recommendations

If the promotion of heritage concessions remains a policy priority in Tunisia, the OECD recommends the following regulatory changes in order to minimise harm to competition and productivity:

Revise the AMVPPC business model to avoid any conflict of interest in the allocation of heritage concessions and clarify its role in related procedures. This will involve separating AMVPPC’s regulatory powers from its role as a market player.

Consolidate the current framework for heritage concessions, which is based on the general concessions regime, and ensure that it is more open to private initiative, more flexible and conducive to competition.

Adopt guidelines that allow grantors, including local authorities, to properly manage concession procedures and design offers that consider the specificities of the sites to be granted.

Consolidate the experience of model contracts to help grantors better manage concessions.

Box 7.2. Redeveloping national cultural heritage for tourism in Portugal

National heritage properties are an important part of Portugal’s historical, cultural and social identity, making a rich and distinctive contribution to the attractiveness of its regions and the tourist experience. The country’s REVIVE programme aims to streamline the redevelopment of vacant properties for tourism, to support regional development, and lengthen the tourist season. Under the programme, publicly owned properties in low-density and coastal regions are being opened up to private sector investment through concessions for their development and operation. The programme is run by a technical team that includes representatives from the Department of Cultural Heritage within the Ministry of Culture, the Department of Treasury and Finance within the Ministry of Finance, the National Defence Resources Department within the Ministry of Defence, and the Portuguese Tourism Board within the Ministry of Economy, together with the close involvement of local municipalities. Safeguards exist to ensure that the plans put forward for each heritage property are suitable for both the property and the development needs of each region. Concession contracts are awarded following an international tender process to ensure transparency, competition and promotion. The inclusion of tourism-related infrastructure, such as hotels, restaurants, and cultural activities and other forms of entertainment, can stimulate new private sector investment to conserve the fabric of heritage sites and open them up to new visitors. As of 2020, a total of 11 properties had been granted exploration licences for four‑ of five‑star hotels with concession lengths of 50 years. The tourism board is actively involved in attracting investors through its official website, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in strategic international markets, and the board’s presence at international fairs.

Source: OECD (2020[5]), OECD Tourism Trends and Policies, https://doi.org/10.1787/6b47b985-en.

7.3. Types of cultural tourism

7.3.1. Background

In Tunisia, cahier des charges, or sets of specifications, govern specific types of cultural tourism businesses. The following analysis examines private galleries, businesses producing and marketing historical and archaeological goods, private museums, and arts and crafts workshops.

7.3.2. Description of the obstacles and policy makers’ objectives

Private museums

Any person wishing to establish a private museum must comply with the relevant cahier des charges, as set out by the Order of the Minister of Culture of 2 January 2001. This applies to all types of private museums including museums of customs, traditions, popular arts and historical museums. It must be signed by the individual or legal representative of the entity that wishes to operate the museum and presented to the Ministry of Culture.

Role of the INP: Investors are required to consult the INP for guidance and support on the technical and scientific components of projects throughout their development and construction. The OECD understands that investors must submit several documents, including:

a file specifying the scientific objectives of the project, its content, its concept, its collection policy and its source

a detailed list of the collections and documents exhibited in museum rooms, with indications of their provenance, condition, ownership, history, aesthetic and documentary value, and photos

a study of the activities to be organised in the museum and a visual presentation on the mode of presentation.

technically specific examples of the spaces that will house the museum, with the definition of the site geographically and historically, highlighting its value if it is a historical monument, and providing as much information as possible related to its dimensions, rooms, condition, maintenance, location and status.

Article 15 of the cahier des charges explains that museum collections exhibited and any information disseminated must be approved by the INP. How collections are presented, including texts and signs, must be approved by the INP and must: 1) guarantee the aesthetics and authenticity of the collection; 2) provide adequate lighting for each type of exposure; and 3) ensure humidity control in exhibition halls.

Article 16 provides that the INP’s approval must be obtained before making any modification to exhibited museum collections or their presentation. Museum owners are required to inform the INP and the délégation régionale pour la culture, or regional delegation for culture, of the area in which museums are located or of any change in their activities.

The OECD understands that the aim of these mandatory consultations is to ensure that all activities of private museums are approved by the relevant authorities before they are taken up, to ensure quality and prevent losses to investors.

Operational requirements: Museum directors must work full-time. The cahier des charges also mandates several minimum equipment requirements related to such considerations as designated spaces for collections, main corridors, disabled persons’ access and adequate ventilation and lighting. Museums must also include a manager’s office, a space for writing and storing documents, a shop, a room to store spare parts, and a room for the observation and protection of exhibits and holdings. The cahier des charges stipulates utilities that must be provided, such as water and electricity, and mandates the provision of sanitary areas.

Private galleries, arts and craft workshops

Any person seeking to establish a private gallery for the exhibition and sale of works of art must comply with the relevant cahier des charges, as set out in the Order of the Minister of Culture of 10 July 2001. This cahier des charges covers the operations of art galleries exhibiting and selling works of art including photographs, sculptures, paintings and carpets, and must be signed by the owner of the business and presented to the Ministry of Culture.

A different cahier des charges applies to the establishment of private arts and crafts workshops for recreation and tourism purposes. It must be signed by the workshop owner and presented to the Ministry of Culture. In such establishments, participants may take part in activities such as drawing, sculpture, painting and painting on glass.

Capital requirements: Operators of private galleries and arts and crafts workshops must have minimum capital of TND 5 000.

Qualification requirements: Managers of businesses must be able to demonstrate training in the field in which the business is active. The OECD understands that this means that the manager must show evidence of a diploma or work experience. In the case of arts and craft workshops, the manager must present an attestation that he is medically fit to work in the field.

Operational requirements: Galleries and workshops must prepare and notify their programmes one year in advance. Their managers must not have another occupation.

Grandfather clause: An exemption from certain provisions in the cahier des charges, such as the capital and professional requirements, exists for incumbents that had been successfully operating for at least five years before the legislation came into force.

Producing and marketing historical and archaeological goods

Any business operator seeking to create and market historical and archaeological goods must obtain an authorisation from the director general of the INP. They must present certain documents in their application, including a plan of the premises where the goods will be stored, proof that they meet a minimum capital requirement of TND 3 000, proof of ownership or lease of premises, and a detailed and complete inventory of goods to be marketed proving their origins and the legality of their possession. This inventory must be approved by the INP before the goods are put on sale. The manager of the business must also provide proof of the highest diploma held by its director in the business’s area of specialisation. Once the INP has received the complete file, it has 30 days to study it, visit the premises where the goods will be stored, and issue an authorisation.11

The barriers to competition presented by the capital and qualification requirements are analysed in relation to private galleries and museums.

The OECD understands that the minimum capital requirements for various private cultural activities serve as guarantees for third parties interacting with private museums, private galleries and arts and crafts workshops, and should ensure they are on a solid financial footing.

The requirement for proof of training is in place likely to ensure the quality of service, to promote the financial viability of companies, and to avoid market entry by unqualified managers. This provision also promotes the employment of graduates with specific qualifications. The OECD understands that the prohibition on managers having another occupation seeks to avoid conflicts of interest and enhance service quality.

The one‑year advance notice requirement for the exhibition and activities programmes likely exists to ensure that the authorities are aware of the activities of private museums and galleries, and that such plans are clear and marketed to consumers to encourage tourism.

The public policy objective of exempting incumbents from certain requirements is unclear.

7.3.3. Harm to competition

The requirement to obtain INP approval for private museums before allowing operations to begin may constitute a barrier to entry, especially if approval is delayed or is based on unclear conditions.

Qualification requirements: The professional and academic requirements may exceed what is necessary for the provision of the services in question at an acceptable level of quality and may increase costs for operators seeking to establish themselves and operate in the market. The existence of such entry and fixed costs may be reflected in higher end costs and less diversity of services. This requirement may discourage market entry and reduce competitive pressure on incumbents, allowing them to charge higher prices. Furthermore, the law does not provide any example of, or guidance on, what is considered “proof of training”, creating legal uncertainty and potentially allowing the arbitrary use of this criterion.

In the case of private galleries, such requirements may be disproportionate, as the managers of private galleries may not need technical expertise or knowledge to carry out their functions. In France, even though gallery management is a regulated activity, there appear to be no obligatory educational requirements for the managers or owner of private art galleries.12 Registration of second-hand goods is, however, required. In the UK, there is no specific regulation for establishing an art gallery, yet in Scotland, the sale of second-hand goods requires a licence or registration, and some UK local authorities may also require this.13

Operational requirements: The advance notice of programmes requirement limits flexibility and may impose a considerable burden on small or new galleries and workshops, as it can be difficult for them to plan so far ahead. If galleries and workshops are unable to adapt, it could limit innovation.

The medical certificate requirement is likely an administrative burden, and the requirement that managers have no other occupation may increase costs for market participants, reduce scope for alternative business models, and reduce the quality of candidates.

By increasing setup costs, the equipment requirements provisions for private museums may reduce the number of potential operators in the market. Furthermore, incumbents may charge higher prices due to having to bear higher costs. These material requirements may also impose administrative burdens on market players, leading to increased prices. The requirements also threaten to reduce output as they essentially prevent short-notice changes. They do not allow museums and galleries to respond to competitors or to consumer demand in the short term.

Grandfather clause: The legislation treats existing market players differently from newer market entrants. Competition is restricted in the sense that newer operators face disadvantages as they must fulfil capital and training requirements that incumbents do not need to satisfy.

7.3.4. Recommendations

Considering the harm to competition described above, the OECD recommends:

Ensuring that any INP consultation or approval requirements are subject to clear rules and guidelines to minimise delays and improve legal certainty.

Abolishing the educational requirements for the managers of cultural establishments and the requirement that workshop managers provide medical certificates. Considering registration requirements or licensing for sales of second-hand goods.

Abolishing the requirement that directors work full-time and/or the ban on other employment. This would permit more flexible working arrangements and uses of resources.

Abolishing the requirement mandating designated minimum spaces in cultural establishments.

Abolishing the requirement to announce gallery and workshop programmes one year in advance.

Ensuring competitive neutrality between incumbents and new entrants by subjecting both to the same requirements. The OECD recommends either:

subjecting all market players, including incumbents, to the requirements of the cahier des charges

or abolishing the requirement that new entrants satisfy the requirements of the cahier des charges which incumbents are not required to satisfy.

References

[4] INP (2023), Base de données de la carte archéologique, https://www.inp2020.tn/projets/carte-archeologique/ (accessed on 20 March 2023).

[3] OECD (2022), Maximising synergies between tourism and cultural and creative sectors - Discussion Paper for the G20 Tourism Working Group, https://www.oecd.org/cfe/leed/OECD-G20-TWG-Discussion-Paper-Tourism-Cultural-Creative-Sectors.pdf.

[1] OECD (2022), The Culture Fix: Creative People, Places and Industries, Local Economic and Employment Development (LEED), OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/991bb520-en.

[5] OECD (2020), OECD Tourism Trends and Policies, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/6b47b985-en.

[2] UNESCO (2021), Cutting Edge | Bringing cultural tourism back in the game, https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/cutting-edge-bringing-cultural-tourism-back-game (accessed on 5 January 2023).

Notes

← 1. Tunisia became a member of UNESCO in 1956 and has ratified seven culture‑ and heritage‑related international conventions, including the 1954 Hague Convention, the 1954 Hague Convention (1st protocol), the 1970 Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property, the 1972 World Heritage Convention, the 2001 Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage, 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage, and 2005 Convention on Diversity of Cultural Expressions. See https://whc.unesco.org/en/statesparties/tn

← 3. See Order of the Ministry of Culture of 13 March 2019.

← 5. Code on Archaeological, Historic and Traditional Arts, Article 2.

← 6. Within five years of the classification of a cultural site, the ministries publish a plan for the protection and enhancement of the site. According to Section 8 of the Code on Archaeological, Historic and Traditional Arts, the development of protection and enhancement plans for a cultural site follows the same procedures as those governing urban development plans. Plans are approved after consultations with the INP by decree issued on the proposal of the minister responsible for heritage and the minister responsible for urban planning.

← 7. Code on Archaeological, Historic and Traditional Arts, Article 4.

← 8. The protection decree can be extended to historic monuments’ surroundings, the conservation of which is necessary for the protection and safeguarding of these monuments. According to Article 27, the protection order is issued to owners by the minister of culture. It is published in the Official Journal of the Republic of Tunisia and displayed at the seat of the local municipality or, failing that, at the seat of the governorate. The Ministry of Culture affixes a plaque indicating that the building is a protected historical monument. If the building is registered, the protection order will be registered on the land title at the request of the Ministry of Culture. Otherwise, the Ministry of Culture will act on the premises and places of the owners to request registration.

← 9. According to Article 24, the state, a local community, a public body or a state‑owned company are allowed to grant concessions.

← 10. Other sources of funding include advertising and sponsorship income, taxes, duties and fees created for the benefit of the agency, state subsidies, and public and private contributions and donations.

← 11. Decree No. 2018‑417, relating to the publication of the exclusive list of economic activities subject to authorisation and the list of administrative authorisations for the realisation of projects, related provisions and their simplification.

← 13. See https://www.lawdonut.co.uk/business/sector-specific-law/art-gallery-legal-issues?_gl=1*89nh8l*_ga*NDcyMTQzMTQ2LjE2NjI1NTc4OTA.*_ga_9222P8LECX*MTY2MjU1Nzg5MC4xLjAuMTY2MjU1Nzg5MC42MC4wLjA.*_ga_H25S6RG6XF*MTY2MjU1Nzg5MC4xLjAuMTY2MjU1Nzg5MC42MC4wLjA.#_ga=2.74738004.738779815.1662557891-472143146.1662557890