This chapter analyses the framework for travel agency and tourist guide services in Tunisia, proposing policy changes and regulatory reforms to enhance competitiveness and competition. Despite the introduction of a notification procedure and a cahier des charges, or sets of specifications, for travel agencies, regulations still include several barriers to entry, such as requirements relating to specific equipment, professional qualifications, operational matters and minimum share capital, creating market distortions, weakening competition and fuelling informality. The regulatory framework for tourist guides is outdated, rendering them subject to rigid, cumbersome licensing procedures with onerous and unnecessary requirements and an annual licence renewal obligation.

OECD Competition Assessment Reviews: Tunisia 2023

6. Travel agencies and other reservation services

Abstract

6.1. Introduction

As “retailers” of transport, accommodation and recreation activities to the public, travel agencies and reservation services play a major role in Tunisia’s travel and tourism industry (OECD; EUROSTAT; UNWTO, 2010[1]) and have made a major contribution to the development of the tourism industry since the 1960s. This chapter analyses the regulatory framework for their operation, which dates back to 1973, identifies several barriers to entry, and proposes policy changes and regulatory reforms to enhance competitiveness and competition in the industry. It also analyses the framework for tour and tourist guides, which are closely linked to travel agencies. The regulatory framework for tourist guides imposes rigid and cumbersome licensing procedures with onerous and duplicative requirements that serve no clear policy objectives.

6.2. Travel agencies

6.2.1. Background

A travel agency is defined in Tunisian law as “a company which carries out, on a permanent basis and for profit, an activity that involves selling to the public, directly or indirectly, on a fixed price or commission basis, tours and stays, individual or collective, as well as any related service”.1 The activities of travel agencies include:

reserving and selling stays in tourist establishments

selling transport tickets of any kind

transporting tourists and renting vehicles (with or without drivers)

organising and selling trips, excursions and tours

receiving and assisting tourists during their holidays

fulfilling insurance formalities on clients’ behalf for any form of risk arising from tourist activity

representing other local agencies or foreign companies with a view to providing these services on their behalf.2

Travel agencies in Tunisia are classified as Category-A or Category-B. Both categories are subject to a cahier des charges, or set of specifications.3 The category determines the activities that may be provided by the travel agency:4

Category-A agencies offer the full range services listed above.5

Category-B agencies can provide a more limited range of services: reserving and selling stays in tourist establishments; selling transport tickets; and representing Category-A agencies in order to provide these services.

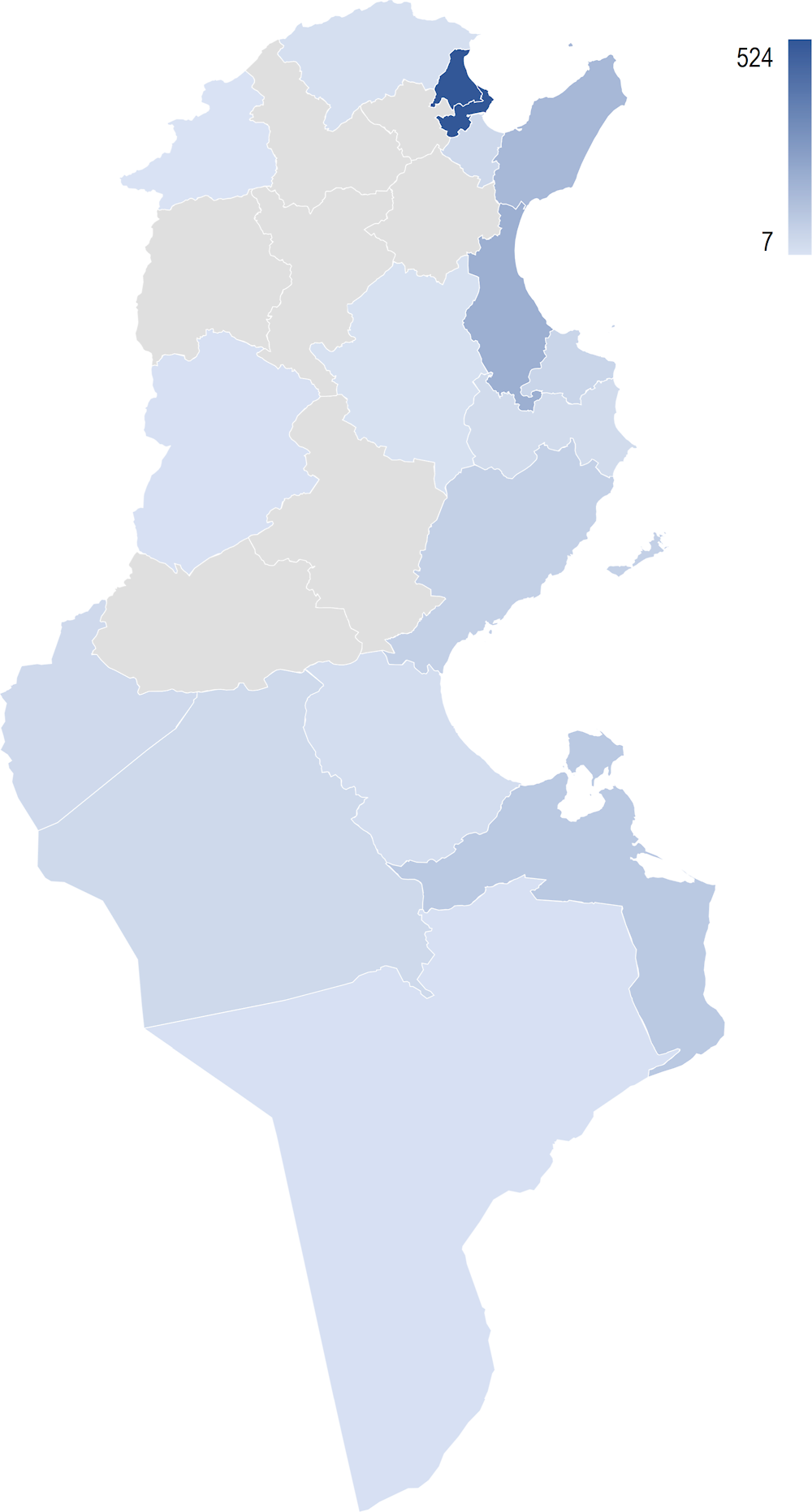

A separate piece of legislation governs online travel agencies.6 This decree applies both to Category-A and Category-B agencies. In order to operate an online travel agency, the agency must simply inform the Office National Du Tourisme Tunisien (ONTT), or Tunisian National Tourism Office, in writing of its intention. The policy objective behind this simple notification procedure is that travel agencies must already qualify as Category-A or -B before they can operate online. A travel agency may thus provide services via the Internet according to its category. In 2019, Tunisia was home to 1 354 travel agencies which are mostly located in Tunis, Nabeul-Hammamet, Sousse and Djerba (Figure 6.1).

Figure 6.1. Travel agencies by region

Source: OECD based on ONTT (2019[2]), Le tourisme tunisien en chiffres, https://www.ontt.tn/sites/default/files/inline-files/extrait%20tourisme%20en%20chiffres%202019%20vf.pdf.

As in the accommodation sector, informality is widespread. Many companies provide services that are supposed to be the exclusive preserve of travel agencies without meeting the requirements, notably sociétés de service, or service companies. The businesses are regulated by the Agence de Promotion de l’Industrie et de l’Innovation (APII), or Agency for the Promotion of Industry and Innovation, under the Ministry of Industry and SMEs. The issue of service companies was also highlighted in responses to an OECD survey (see Chapter 1). Alternatively, companies satisfy the requirements of Category-B travel agencies but provide services demarcated in the legislation for Category-A agencies. The OECD understands that enforcement is lacking. The legislation provides for penalty provisions for any individual or company that carries out these activities without meeting the conditions stipulated by the cahier des charges.7

6.2.2. Description of the obstacles and policy makers’ objectives

Capital requirements: Category-A travel agencies are required to have capital of TND 100 000, while Category-B agencies must have capital of TND 30 000. This capital must be in cash and fully paid up. By contrast, the minimum capital requirement for a société à responsabilité limitée, or limited-liability company, is generally TND 1 000.

In addition, any individual or company wishing to operate a Category-A or Category-B agency must provide an unconditional bank guarantee as security for their professional obligations. The amount of this deposit is set by an order of the Ministry of Tourism and is stipulated in the cahier des chargess. For Category-A agencies, the sum required is TND 50 000. For Category-B agencies, it is TND 25 000.

According to the ONTT, the minimum capital requirement ensures travel agencies’ proper operation. In Tunisia in general, the amount of capital required by regulations is determined by company type. The bank guarantee is in place to protect clients from non-execution by travel agencies. If an agency does not fulfil its contracts, the ONTT can use these funds to reimburse its clients.

The OECD understands that the reason for designating two categories of travel agencies is to allow investors wishing to provide the limited services of Category-B agencies to enter the market and operate subject to fewer requirements than required for Category A. According to the authorities, the legal framework is currently being revised, and it was not available for the OECD’s review before the finalisation of this report. One aim of the current revisions is to merge the two categories and tighten the requirements in the cahier des charges. The proposed merge aims to prevent agencies complying with the lower requirements for Category B from providing Category-A services, and to make compliance enforcement easier for the ministry.

Professional requirements: Any individual or legal representative of a business entity wishing to operate as a travel agency must meet certain professional requirements.8 In order to operate a Category-A agency, the individual or legal representative of the business must either:

Hold a higher education diploma (a degree with a course duration of at least four years) or a specialised diploma (in hotel management, tourism or economics and management) and have two years of work experience (with one year at managerial level).

Or hold a higher education diploma (a degree with a course duration of at least three years), a specialised or technical diploma, or a specialised professional training diploma, and have three years of work experience in a travel agency (with two years uninterrupted in a managerial position).

According to the ministry, the individual or legal representative of the business must possess the required education and experience because they sign the cahier des charges and become the contact for the ministry and the agency’s clients, including tourists and international partners.

Monopoly on certain activities: The OECD understands that, aside from specific exceptions mentioned in the law, such as the limited exemptions for associations,9 only travel agencies can provide the services stipulated in the legislation. These include: 1) sales and reservations of stays in tourist establishments; 2) sales of transport tickets, tourist transport and vehicle rentals (with or without drivers); 3) the organisation and sale of trips, excursions and tours; 4) services related to the reception of, and assistance for tourists during their stays; 5) the fulfilment of insurance formalities for any form of risk arising from tourist activities on behalf of clients; and 6) the representation of other local agencies or foreign companies with a view to providing these services on their behalf.10 In practice, vehicle rentals are not offered only by travel agencies, as the activity is regulated by a cahier des charges under the Ministry of Transport.

The OECD understands that these activities may be provided only by travel agencies for consumer protection purposes and to guarantee the quality of services, given the requirements in the cahier des charges, such as capital levels and bank guarantees.

Operating requirements: The cahier des charges for Category-A travel agencies requires that they obtain approval from the ONTT for each excursion that will be undertaken. Agencies are required to provide information about the route, the driver and the number of people participating 48 hours in advance. According to stakeholders, problems arise when tourists book online and wish to undertake excursions at short notice. In such circumstances, travel agencies must either give up the opportunity to organise the excursion because they will not obtain the required approval from the ONTT in time (especially during weekends) or organise the excursion in violation of the law. Given the approval requirements, companies are unable to provide customers with immediate or real-time responses to such requests. These issues were highlighted in discussions with industry federations and in the OECD survey (see Chapter 1).

According to the authorities, the approval requirement is in place to ensure safety, manage site congestion and protect consumers.

Category-A travel agencies have the right to organise tours and visits. For any tour organised in a public space, such as in a museum, at an historical monument or on public transport, the travel agency must use a licensed tourist guide. The use of licensed guides is controlled by regional tourism authorities. Travel agencies are required to submit their excursion plans to these authorities and, once approved, they receive an authorisation to carry out their excursions. In their submissions, they must name the guide(s) who will accompany the tourists on the excursion. Travel agencies are thus required to use licensed guides even for tours such as food tours, which do not necessarily require the knowledge of a licensed guide.

According to the authorities, the requirement is in place to ensure certain standards and quality in the provision of services. Official guides must adhere to certain condition, including education requirements (see Section 6.3).

Foreign travel agencies: The legislation provides that foreign travel agencies may operate in Tunisia only in accordance with international conventions or subject to reciprocity. According to the authorities, foreign travel agencies cannot operate directly in the country, but only indirectly through partnerships with local Tunisian agencies.

The Ministry of Tourism does not supervise and is not otherwise involved in partnerships between foreign and local travel agencies, which involve bilateral commercial contracts and are not governed by any laws, guidance or reporting obligations for the Tunisian agency. The cahier des charges lists the activity as being one of the activities of travel agencies, reaffirming the fact that foreign agencies cannot operate directly in Tunisia.

6.2.3. Harm to competition

Minimum professional capacities and material requirements to operate lead to an increase in companies’ fixed costs. This potentially increases prices charged in the market. These barriers may also reduce the number of companies in the market, resulting in less competitive pressure for incumbents.

Capital requirements: Requiring minimum capital levels higher than those mandated for limited-liability companies increases market access costs, preventing potential entrants from deploying smaller amounts of capital, even if these would be adequate for their businesses. This has a disproportionate impact on small-scale operators and new companies. These provisions may lead to a reduction in the number of operators and greater market concentration, and may prevent smaller operators from offering more innovative, lower-priced services. They may also raise prices charged by existing market players. In addition, businesses providing travel agency services informally through service companies are subject to minimum capital requirements only in line with the general minimum of TND 1 000 for a limited-liability company.

The bank guarantee requirement increases market access costs, but unlike the capital requirement, it is likely proportional. Other jurisdictions, such as France, have financial guarantee requirements for travel agencies. In France, the guarantee must be taken out with specific institutions and is unlimited in nature, taking into account the experience and activities of the agency. It is required to ensure the reimbursement of consumers, particularly those purchasing package deals.11 In Croatia, before a travel agency begins operating, it is required to submit information and proof of fulfilment of the protection obligation in case of insolvency and liability insurance to the Ministry of Tourism.12 The OECD recommends the use of bank guarantees or insurance contracts instead of capital requirements (see Box 6.1).

Although the classification of travel agencies as Category A or B aims to encourage entry and minimise barriers for those wishing to offer fewer services, the lack of enforcement may distort competition, as in practice, businesses misuse the categories. In addition, there is a lack of enforcement against service companies providing travel agency services informally without meeting the requirements of Category A or B. The ineffective enforcement of the rules for the two categories and against service companies may distort the market, as businesses adhering to the official requirements face higher barriers than those that satisfy only the requirements of Category B or which do not satisfy the cahier des charges at all. The lack of enforcement also suggests that some of the requirements for travel agencies may be stricter than necessary to achieve policy makers’ objectives.

Professional requirements: These may increase costs for operators seeking to establish themselves and operate in the market, which may be reflected in higher end costs and less diversity of services. The prerequisite of professional experience in the sector further reduces the number of potential professional entrants in the sector and limits employment opportunities for new graduates who may hold the requisite academic qualifications, particularly in small markets with limited numbers of operators. Being required to obtain work experience at an existing agency could also affect an individual’s incentives to start a competing firm.

In France, professional aptitude conditions for travel agents, such as diplomas and experience, were abolished in 2016. To register as a travel agent in France, applicants must provide only proof of the conditions of civil liability insurance and comply with a financial guarantee.13 In Croatia, travel agency managers must have completed secondary school and have passed a professional exam for business managers.14

Monopoly on certain activities: Travel agencies’ monopoly on a large range of tourism activities may result in increased market concentration, given the numerous requirements associated with establishing agencies. In France, travel services are considered activities of travel agencies only where the agency organises such services and does not itself provide them.15

Operating requirements: The requirement that the ONTT approve excursions makes it more difficult for market players to operate due to the significant administrative burden it places on them. It limits operators’ flexibility and their ability to innovate, seek new business opportunities, and adapt to consumer demand for last-minute excursions and trips, in addition to limiting consumer choice.

The requirement to use licensed guides in all situations may reduce choice for travel agencies and increase costs. It may also mean that new and innovative tours, such as food tours, cannot be offered as licensed guides may not possess the required knowledge and travel agencies are allowed to use only official guides. The requirement to name guides ahead of time may, and in practice appears to, result in businesses attempting to bypass this rule, distorting competition between them and those operating in compliance with it. Stakeholders explained that travel agencies often name official guides in declarations, but in reality they use unofficial guides to save money. According to stakeholders, inspector numbers are insufficient to verify the use of only licensed guides by travel agencies.

Box 6.1. Capital requirements: international experience

Many countries have general minimum paid-up capital requirements for specific types of company structures, for example, limited-liability companies or public limited-liability companies, rather than sector-specific capital requirements.

In Doing Business (2013[3]), in a chapter entitled “Why are minimum capital requirements a concern for entrepreneurs?”, the World Bank observed that, in general, minimum share capital is not an effective measure of a firm’s ability to fulfil its debt and client service obligations. Share capital is a measure of investment by a firm’s owners, not the assets available to cover its debts and operating costs. In the report, the bank concluded that minimum capital requirements protect neither consumers nor investors, and that they are associated with less access to financing for SMEs and a lower number of new companies in the formal sector. Creditors prefer to rely on objective assessments of companies’ commercial risks based on analysis of financial statements, business plans and references, as many other factors can affect a firm’s chances of facing insolvency. Moreover, such capital requirements are particularly inefficient if firms are allowed to withdraw the funds soon after incorporation.

Contrary to initial expectations, the World Bank report cites evidence that minimum capital requirements do not help the recovery of investments; indeed, they are negatively associated with creditor recovery rates. Credit recovery rates tend to be higher in economies without minimum capital requirements, suggesting that alternative measures, such as efficient credit and collateral registries, and enhanced corporate governance standards, are potentially more efficient in addressing such concerns. Moreover, capital requirements tend to diminish firms’ growth potential.

Minimum capital requirements have been found to be associated with higher levels of informality, and with firms operating without formal registrations for longer periods. In turn, informality results in an uneven playing field in the market, increased difficulty in enforcing necessary regulations, and lost tax revenue for the state.

Commercial bank guarantees and insurance contracts are a better instrument for managing counterparty risks, and should therefore be the focus of any regulation seeking to promote a minimum level of business certainty for users of tourism services.

In addition to being largely ineffective in achieving policy makers’ objectives, higher minimum capital requirements are associated with lower business entry, as shown in the World Bank report (2020[4]).

An increasing number of countries have eliminated or reduced minimum capital requirements. In 2003, 124 countries imposed minimum capital requirements for the founding of companies. Since then, 58 countries have eliminated such requirements altogether. The World Bank finds that the most significant changes have occurred in the Middle East and North Africa, where average minimum capital requirements amounted to 466% of income per capita when the Doing Business report (2003[5]) was published but had dropped to 5% of income per capita by the time the 2020 report was published.

Source: OECD (2021[6]), OECD Competition Assessment Reviews: Logistics Sector in ASEAN, https://www.oecd.org/competition/fostering-competition-in-asean.htm.

The requirement for travel agencies to use licensed guides is more limited in some other jurisdictions. In France, for example, only guided tours in museums or at historical monuments must be carried out by qualified guides that hold a professional licence (la profession de guide‑interprète ou de conferencier, or the profession of guide‑interpreter/lecturer) where paid tours are organised by travel agencies or tour operators.16 The profession of tour guiding is not otherwise regulated in France.17

Foreign travel agencies: This prohibition directly limits the number of suppliers and potential investors in Tunisia’s tourism market. It may affect prices and quality, as competition with foreign travel agencies may encourage both local and foreign firms to become more efficient.

6.2.4. Recommendations

The OECD recommends revising the cahier des charges for travel agencies. In general, activities that may be provided exclusively by travel agencies should be limited to core activities and authorisation requirements should be proportional. Therefore, the OECD recommends:

Ending the exclusive character of the following travel agency activities:

sales of transport tickets

services related to welcoming and assisting tourists during their stays

the fulfilment of insurance formalities on behalf of clients

car and vehicle rental

tourist transport.

Where necessary, introducing alternative regulations for the above activities where a genuine public benefit would result and considering possible harm to competition.

Allowing market participants to accumulate authorisations in the tourist services sector, such as those to provide tourist transport, offer travel agency services and sell transport tickets, if they fulfil the necessary requirements.

Creating a separate cahier des charges for tourist transport under the Ministry of Transport as provided for in the legislation (see Section 5.2).

Abolishing the distinction between Category-A and -B travel agencies and subjecting all agencies to the same requirements, which should be reformed as outlined above.

Abolishing travel agency-specific minimum capital requirements and instead requiring compliance only with general requirements under commercial law. Alternatively, bank guarantees or insurance contracts rather than cash deposits could be accepted to comply with capital requirements. The Category-A and -B cahiers de charges already require travel agencies to provide bank guarantees.

Abolishing professional requirements such as academic qualifications and experience levels that do not necessarily provide any guarantee of service quality.

Ending the ONTT approval requirement for excursions, or at least replacing it with a notification requirement that can be filed online to allow short-notice activities outside of administrative working hours.

Considering allowing the use of unofficial guides for innovative tours that do not require the expertise of licensed guides.

Considering allowing foreign travel agencies to enter and operate in the Tunisian market and removing the local partnership requirement. Foreign agencies should be required to comply with the same requirements imposed on local players. Alternatively, foreign agencies could be permitted to operate subject to reciprocity agreements (see Section 9.3).

6.3. Tourist guides

6.3.1. Background

According to the ONTT’s 2020 annual report, 1 000 guides were active in Tunisia in 2020, including 823 professional guides, 100 teaching auxiliary guides, 26 auxiliary guides, 15 local guides, three site guides and 33 Saharan guides. The professional tourist guide exam held in 2019 saw 60 new guides admitted with differing languages and specialities (ONTT, 2020, pp. 15-16[7]). According to the Fédération Tunisienne des Guides Touristiques (FTGT), or Tunisian Federation for Tourist Guides, only 400 guides are currently operating, 95% of whom are freelance and have no contracts with travel agencies.

6.3.2. Description of the obstacles and policy makers’ objectives

The tourist guide profession is defined by Decree‑Law No. 73‑5 as including “any person who accompanies tourists for remuneration, in transport vehicles, in a public space, at historical monuments and museums, and provides them with comments and explanations of any kind”. The decree‑law also provides for two categories of tourist guides: professional guides and auxiliary guides. Professional guides are defined as those “exercising their function on a permanent basis, the competence of these guides being able to extend either to the whole of the territory (national guides) or to a commune or a governorate (local guides)”. Auxiliary guides are those that engage in the profession temporarily.

Several EU countries, including Austria, Belgium, Croatia, Cyprus, France, Hungary, Italy, Malta, Romania, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia and Spain, and non-EU countries, such as Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, South Africa and the United Arab Emirates, regulate the tourist guide profession.18

In order to work as a tourist guide in Tunisia, an individual must obtain a professional licence granted by the ONTT. The OECD understands that competences and qualification conditions are not defined by decree but are set out on the website of the Ministry of Tourism and through the portal of online government information service SICAD. One set of requirements must be met to obtain the licence for the first time and another set applies for renewals of the licence.19 According to the authorities, the professional licence requirements for local and national guides are the same.

The legislation provides for fines for those violating the provisions of the law, including, for example, by providing tourist guide services without being officially recognised. Stakeholders have noted a large number of guides operating illegally and whom are often illegally employed by travel agencies to provide services reserved for official guides. Although the ONTT carries out inspections of travel agencies, enforcement appears to be lacking.

Criteria for obtaining a professional licence: Applicants must fulfil the criteria set out on the Ministry of Tourism and SICAD websites. They include educational requirements, a clean criminal record and a medical certificate, the latter being required both at the time of first issuance and for renewals. Applicants must be graduates of one of Tunisia’s two tourist training centres (Centres de Formation Touristique de Kerkouane et de Bellarigia) and have specialised as a tourist guide. Alternatively, they must have passed a tourist guide recruitment exam organised by the ONTT. According to the stakeholders, the exam is held every three or four years. The last exam was held in 2019 and the one before that in 2015.

The educational requirements or alternative exam requirements are likely in place to ensure a certain level of knowledge among guides and thus service for tourists. The OECD understands that the medical certificate and the criminal record requirements are in place to ensure that guides are fit and authorised to carry out their profession.

Box 6.2. Tourist guide regulation

France

In France, only tour guides providing guided visits to certain museums or historical monuments are required to obtain professional licences and meet educational requirements.1 Other, more general guides are not subject to regulation.

Morocco

In Morocco, the tourist guide profession is regulated by Law No. 05‑12 (modified by Law No. 133.13 and Law No. 93.18). These laws set out conditions for entering and practicing the profession. A legal distinction exists between two types of guides: guides for towns and organised tours; and guides for natural sites. According to OECD Tourism Trends and Policies 2022, “in February 2018, in accordance with existing laws, the Department of Tourism launched a review of licensing relating to city guides, tour guides and nature guides. At its conclusion, the programme had led to the certification of 1 108 guides, including 905 in the category of city and tour guides and 203 in the category of natural area guides. This programme also encouraged the integration of guides mastering new languages such as Mandarin, Japanese, Russian, Swedish, Polish, Turkish, Dutch and Portuguese”.3

Jordan

In Jordan, individuals must obtain licences from the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities to work as tourist guides. Applicants must hold a university degree or a diploma in tour services, and pass a language test, an interview and an exam following a six‑month course held by the ministry.4

Notes:

3. See https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/409d3fd2-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/409d3fd2-en.

4. See Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, https://mota.gov.jo/En/Pages/Tourist_Guides_Qualification.

Renewal of the professional licence: The professional licence must be renewed annually. According to stakeholders, the annual renewal is an administrative burden as it takes a long time and involves the provision of a medical certificate attesting that the candidate is fit to practice the profession. The licence cannot be renewed if more than two years have elapsed since its expiry. In such cases, guides must obtain new licences and comply with the relevant conditions. If guides do not meet the education requirements, they must re‑sit the exam, which is run only every three or four years.

The annual renewal is likely in place to ensure the quality of guide services in Tunisia and to ensure consumer protection. The two‑year limit likely aims to encourage renewals and commitment to the profession.

Auxiliary guides: Although it is provided for in the legislation, according to the authorities, the auxiliary guide profession no longer exists, as the ONTT no longer grants such guides the required professional licence. There is no legal document that supports this change and data from the ONTT’s 2020 annual report appears to contradict this, showing 26 auxiliary guides and 100 teaching auxiliary guides active in the market (ONTT, 2020, p. 15[7]). According to stakeholders, professionals such as university professors could previously work as guides during semester breaks. Since 2019, they have lost the right to work as guides because one of the current conditions for renewing the professional licence, as explained on SICAD’s website, is not to be engaged in another profession.

The OECD understands that the ONTT decided to stop granting auxiliary guides professional licences because too many were operating in the market and professional guides were struggling to find job opportunities.

Temporary authorisations for foreign guides: To be able to accompany tourists in Tunisia, representatives of foreign travel agencies, including foreign guides, must obtain a temporary authorisation from the relevant consular authority. The OECD has not been able to identify the process and conditions for obtaining this authorisation, as they are not publicly available. The OECD understands that in practice, temporary authorisations for foreign travel agency representatives are issued by the ONTT, at its discretion and infrequently. However, according to the FTGT, several foreign guides are informally active in the market, especially for tourists whose languages are not commonly spoken by Tunisian guides, such as eastern European languages.

The OECD understands that the ONTT does not issue authorisations for foreign guides unless there is a lack of Tunisian guides. They are notably issued when Tunisian guides cannot meet demand for tours in certain languages. For example, authorisations may be granted for representatives that speak Mandarin, as very few Tunisian guides are proficient in this language.

6.3.3. Harm to competition

Criteria for obtaining a professional licence: The specific educational requirements – a specific course at one of only two institutions – may reduce the number of tour guides in the market, increasing concentration. The exam provides an alternative, but applicants must wait up to four years until an exam is held, which may delay their entry. The medical certificate requirement may increase the administrative burden on applicants.

Box 6.3. Educational requirements for tourist guides

Croatia

In Croatia, individuals wishing to work as tour guides must pass a basic professional exam. There is an additional exam for tour guides seeking to provide services in protected areas of artistic, heritage and archaeological value. A further category of tourist guides, known as honorary tourist guides, are not required to sit the professional exam in order to provide occasional services. Such guides include prominent scientists and experts who can be recognised on request and at the discretion of the minister of tourism as guides in fields of high specialisation.1

France

In France, only guides offering guided visits to certain museums or historical monuments are required to obtain a professional licence.2 For this authorisation, guides must hold a master’s degree and have undertaken three specific course units or have minimum experience of one year in a specific domain.3

Notes:

1. See, Article 70 (1) of the law on providing services in tourism. To provide tourist guide services, the applicant must pass the professional exam for tourist guides, have completed at least secondary education, know the language he or she will use (B2 level and possess sufficient Croatian language skills). Article 76 sets out the conditions for honorary guides.

3. See Order of 9 November 2011 on the skills required for the issuance of the professional guide card to holders of a professional license or diploma conferring the master grade.

Renewal of the professional licence: Annual renewals impose an administrative burden on tour guides in Tunisia, possibly deterring entry, encouraging exit and raising costs, ultimately raising prices or lowering quality for customers. Administrative delays amplify the harm. Although annual renewals appear to exist in some jurisdictions, such as the United Arab Emirates and Qatar, licences can be renewed online in those countries.20 In jurisdictions such as France, no renewal requirement exists.

Auxiliary guides’ ineligibility for the professional licence: Denying auxiliary guides permission to work reduces the number of tour guides and increases market concentration, potentially raising prices and reducing quality by preventing more diversity. Language or history professors, for example, may bring new and valuable insights to the market. In general, the renewal requirement not to have another occupation may also reduce the number of market players and discourage entry. The authorities informed the OECD that this decision had been taken following the 2015 terrorist attacks to ensure licenced guides had sufficient job opportunities.

Temporary authorisations for foreign guides: This requirement directly limits the number of tour guides able to operate in Tunisia and discriminates against foreign guides. It may affect price and quality, as competition may be reduced. It may also directly reduce the number of multi-country tours that include Tunisia on their itineraries and may stop some tours altogether.

6.3.4. Recommendations

In light of the harm to competition caused by the provisions described above, and their limitations in terms of achieving policy goals, the OECD recommends:

Streamlining the procedure for applications and renewals of the professional licence and increasing its validity so that renewals are required less often, or allowing applicants to renew their licences easily online.

Allowing auxiliary guides to be granted professional licences to operate as official guides, as provided for in the legislation.

Revising the educational requirements for the professional licence for tourist guides and increasing the frequency of the exam.

Considering the exemption of individuals who wish to provide tours outside of museums and historical sites from the professional licence obligation.

Streamlining temporary authorisation procedures for foreign travel agency representatives, including foreign guides, that demand it. Rules or guidelines on the process and conditions for temporary authorisations should be clear and publicly available.

References

[6] OECD (2021), OECD Competition Assessment Reviews: Logistics Sector in ASEAN, https://www.oecd.org/competition/fostering-competition-in-asean.htm.

[1] OECD; EUROSTAT; UNWTO (2010), Tourism Satellite Account: Recommended Methodological Framework 2008, UN, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264274105-en.

[7] ONTT (2020), Rapport Annuel 2020, https://www.ontt.tn/sites/default/files/inline-files/Rapport%20ONTT%202020.pd.

[2] ONTT (2019), Rapport Annuel, https://www.ontt.tn/sites/default/files/inline-files/rapport2019.pdf (accessed on 8 Juin 2022).

[4] World Bank (2020), Doing Business 2020 : Comparing Business Regulation in 190 Economies, World Bank, http://hdl.handle.net/10986/32436.

[3] World Bank (2013), Doing Business 2014: Why are minimum capital requirements a concern for entrepreneurs, World Bank, https://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/pdf/10.1596/978-0-8213-9984-2_Case_studies_1.

[5] World Bank (2003), Doing Business 2004, World Bank, https://archive.doingbusiness.org/en/reports/global-reports/doing-business-2004.

Notes

← 1. Decree-Law No. 73-13 of 17 October 1973, on the regulation of travel agencies as amended by Law 2006-33 of 22 May 2006 on the simplification of procedures in the field of administrative authorizations relating to the sector, Article 1.

← 2. Decree-Law No. 73-13 of 17 October 1973, on the regulation of travel agencies as amended by Law 2006-33 of 22 May 2006 on the simplification of procedures in the field of administrative authorizations relating to the sector, Article 2.

← 3. Decree-Law No. 73-13 of 17 October 1973, on the regulation of travel agencies as amended by Law 2006-33 of 22 May 2006 on the simplification of procedures in the field of administrative authorizations relating to the sector, Article 3.

← 4. Decree-Law No. 73-13 of 17 October 1973, on the regulation of travel agencies as amended by Law 2006-33 of 22 May 2006 on the simplification of procedures in the field of administrative authorizations relating to the sector, Article 5.

← 5. Decree-Law No. 73-13 of 17 October 1973, on the regulation of travel agencies as amended by Law 2006-33 of 22 May 2006 on the simplification of procedures in the field of administrative authorizations relating to the sector, Article 2.

← 6. Order of the Minister of Tourism of 9 August 2007, on the rules applicable to the exercise of the activity of travel agencies by Internet.

← 7. Decree‑Law No. 73‑13 of 17 October 1973, regulating Travel Agencies – Amended by Law No. 2006‑33 of 22 May 2006 on the simplification of administrative procedures related to the sector, Article 24. Any individual or company engaged in travel agency activities without meeting the conditions in the cahier des charges is liable for a fine ranging from TND 5 000 to TND 10 000. In addition, the court will order the immediate closure of the business. In cases of recidivism, the fine will be doubled.

← 8. See Chapter 1 for details on barriers.

← 9. Decree‑Law No. 73‑13 of 17 October 1973, regulating Travel Agencies – Amended by Law No. 2006‑33 of 22 May 2006 on the simplification of administrative procedures related to the sector, Article 3. Legally constituted associations can engage in travel agency activities, specifically, organising trips, excursions or tours subject to the agreement of the minister in charge of tourism, up to a limit of twice a year, and after submitting a programme of excursions and tours to the ONTT.

← 10. Decree‑Law No. 73‑13 of 17 October 1973, regulating Travel Agencies – Amended by Law No. 2006‑33 of 22 May 2006 on the simplification of administrative procedures related to the sector, Article 2.

← 11. See Decree No. 2015‑1111, relating to the financial guarantee and professional civil liability of travel agents and other operators involved in the sale of travel and stays: https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/loda/id/JORFTEXT000031127908/ and Articles L.211‑18 et R.211‑26 of the Tourism Code.

← 12. See Article 13 (2) of the Law on providing services in tourism.

← 13. See https://jesuisentrepreneur.fr/idees-business/agence-voyage/reglementation-agence-voyage#:~: text=Les%20professionnels%20du%20secteur%20ont,renouvelpercentageC3%A9e%20tous%20les%20trois%20ans.

← 14. See Articles 16‑19 of the Law on providing services in tourism.

← 15. Article L.211‑1 of the Tourism Code.

← 16. Tourism Code, Article L221‑1 and L221‑2. See: https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/codes/section_lc/LEGITEXT000006074073/LEGISCTA000006107988/#LEGISCTA000006107988

← 18. EU: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/regprof/index.cfm, Non-EU examples: Morocco : Guides de tourisme - Ministère du Tourisme, de l’Artisanat et de l’Economie Sociale et Solidaire (mtaess.gov.ma); South Africa: https://www.westerncape.gov.za/dept/edat/services/813/17782; Jordan: https://mota.gov.jo/Default/En,