This chapter measures disparities in financial literacy performance. It first summarises the variation in performance in financial literacy observed within countries and economies. It then analyses the link between performance in financial literacy and gender, socio-economic status, school location and students’ immigrant background.

PISA 2022 Results (Volume IV)

3. Variations in students’ performance in financial literacy within countries and economies

Abstract

National averages in financial literacy performance of students may hide the variation across students within countries and economies. While Chapter 2 presents a cross-country comparison, this chapter explores variations in performance in financial literacy within countries and economies.

Students and schools were chosen (or sampled) in PISA 2022 to capture a representative cross-section of the 15-year-old student population. Students across the entire socio-economic spectrum and with different family backgrounds were sampled, as were schools in different locations, of different sizes, and with different funding sources (amongst other characteristics). This allows PISA to report not just on how much variation in students’ scores is observed within a country or economy but how that variation is related to student and school characteristics, non-behavioural factors that cannot easily be changed. This chapter focuses on the variation related to students’ gender, socio-economic status, school location and immigrant background. Results may help financial education policy makers identify specific groups of students who could benefit from targeted interventions, with the aim of improving equity and achievement in financial literacy across all students in a country or economy.

What the data tell us

In most participating countries and economies, most of the variation in financial literacy performance came from within school variations, meaning that the characteristics of students accounted for most of the overall variation in student performance in financial literacy, compared to variations between schools and between countries and economies.

Socio-economically advantaged students performed better in the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment than disadvantaged students by 87 points, which is more than one proficiency level, on average across OECD countries and economies. On average across OECD countries and economies, 12% of performance differences in financial literacy could be explained by students’ socio-economic status.

Immigrant students scored 15 points lower than non-immigrant students, after accounting for their socio-economic status, on average across OECD countries and economies.

Students in rural areas scored 19 points lower than students in towns and urban areas, after accounting for their socio-economic status, on average across OECD countries and economies.

Boys outperformed girls in Austria, Costa Rica, Denmark*, Hungary, Italy and Portugal, while girls outperformed boys in Bulgaria, Malaysia, Norway and the United Arab Emirates. On average across OECD countries and economies, boys were over-represented at both ends of the performance distribution.

Variation in performance within countries and economies

As described in Chapter 2, there are large variations in mean performance across countries and economies in the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment: students in the Flemish community of Belgium, the highest-performing country or economy, scored 527 points, on average, while students in Malaysia, the lowest-performing country or economy, scored 406 points, on average – a gap of 121 score points (Table IV.B1.3.1). However, there were also large variations in performance between students within the same country or economy.

One way to summarise the within-country variation in performance is the standard deviation. The average standard deviation across all participating OECD countries and economies in the first PISA financial literacy assessment in 2012 was set at 100 score points.1 In PISA 2022, the standard deviation in 11 of the 20 countries and economies was below 100 score points, meaning that the gaps in performance among students in these countries and economies are relatively narrow. Indeed, the standard deviation was 82 score points in Saudi Arabia; it was roughly 90 score points in Spain (88 points), Costa Rica and Portugal (89 points), Italy and Malaysia (90 points) and Denmark* and Peru (92 points); 96 score points in Poland and roughly 100 in the Flemish community of Belgium and Hungary (99 points). Denmark* is particularly noteworthy as a country that has achieved both high performance and low variation in performance among students. Students in this country are likely to be well-prepared to make financial decisions, regardless of their family background or school characteristics. The largest standard deviations in performance (between 108 and 120 score points) were observed in the Netherlands*, Norway and the United Arab Emirates (Table IV.B1.3.1).

Various interpercentile ranges can also be used to describe the distribution in student performance. For example, the interdecile range is equal to the gap between the 10th and 90th percentiles; 80% of students - four out of five students – score in this range.2 The smaller the interdecile range, the smaller the gap in performance between stronger and weaker students, and the smaller the variation in student performance.

The interdecile range in Costa Rica, Saudi Arabia and Spain was at or below 230 points. By contrast, the interdecile range of 316 score points in the United Arab Emirates indicates that its strongest-performing students in financial literacy scored more than 4 proficiency levels higher than its weakest-performing students (603 points at the 90th percentile compared to 287 points at the 10th percentile) (Table IV.B1.3.1).

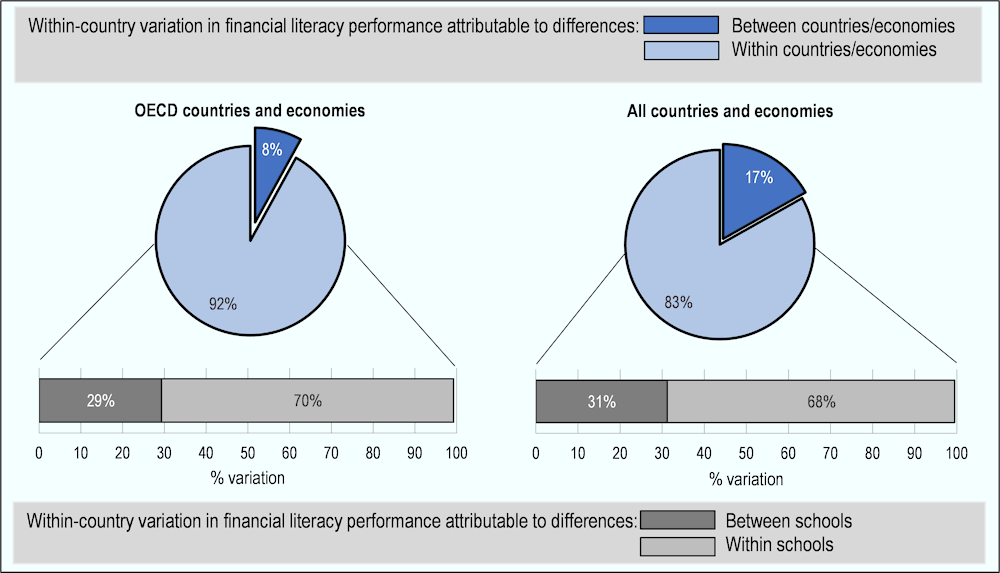

Performance differences among countries and economies, schools and students

The variation in financial literacy performance among students within a country or economy can be broken down into differences at the student, school and country or economy levels.3 In PISA 2022, about 17% of the variation in financial literacy performance across all participating countries and economies is linked to mean differences in student performance between countries and economies, while 83% of this variation is linked to differences within countries and economies (Figure IV.3.1). This suggests that the overall economic and social conditions of countries and economies and their education policies may have a limited influence on student performance in financial literacy.

Figure IV.3.1. Variation in financial literacy performance between countries and economies, schools and students

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 Database, Table IV.B1.3.2.

Similarly, across OECD countries, only 8% of the variation in financial literacy performance is between countries and economies, while 92% of the variation is within countries and economies. In other words, the characteristics of countries and economies do not play an important role in explaining differences in student performance in financial literacy among OECD countries and economies. This is likely because the economic and social conditions of OECD countries are very similar to each other. It is also possible that education policies and practices vary less across OECD countries than across all countries and economies participating in the 2022 PISA financial literacy assessment.

Out of the variation observed within countries in PISA 2022, 29% of the OECD average variation in financial literacy performance is between schools; the remaining part of the variation (70%) is within schools (Figure IV.3.1). Across all participating countries and economies, 31% of the average variation in financial literacy performance is between schools, and 68% is within schools. This means that school characteristics do not play a dominant role in explaining student performance in financial literacy; instead, it is the characteristics of students themselves (i.e. their background, attitudes, behaviours, etc.), that account for most of the overall variation in student performance.

Across 18 participating countries and economies, most of the variation in financial literacy performance comes from within school variations. In seven countries and economies (the Canadian provinces*, Denmark*, Norway, Portugal, Saudi Arabia, Spain and the United States*) more than 80% of the total variation in the country or economy’s financial literacy performance comes from differences within schools. By contrast, differences between schools account for slightly more than half of the total variation in student performance in Bulgaria and the Netherlands* (Table IV.B1.3.2).

Trends in the variation in performance

Variations in performance within countries and economies changed, to some extent, in some of the countries and economies that participated in the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment and in at least one earlier financial literacy assessment.4,5 Such changes can result from shifts at different points of the performance distribution. For example, for some countries and economies, the average score may improve when high-performing students perform better. In other countries and economies, improvements in mean scores can be largely the result of improvements in performance amongst the lowest-achieving students or can come from improvements over the entire distribution.

Between 2012 and 2022, there were no significant changes in most of the performance distribution in financial literacy, on average across OECD countries. The improvement in mean score in Italy between 2012 and 2022 is largely related to an improvement at the median and upper part of the distribution, while the mean decline in in the Flemish community of Belgium is associated to a decline at the median and in the lower part of the distribution (Table IV.B1.2.1 and Table IV.B1.3.3).

Between 2015 and 2022, the decline in mean score in the Flemish community of Belgium is related to a decline at the median and in the upper part of the distribution. The improvements in mean scores in Poland and the United States* between 2015 and 2022 are largely related to improvements across most of the distribution (except the 90th percentile), and mean improvements in Brazil, Peru and Spain are mostly associated with improvements in the lower part of the distribution (Table IV.B1.2.1 and Table IV.B1.3.3).

Between 2018 and 2022, there were no significant changes in most of the performance distribution in financial literacy, on average across OECD countries. The decline in mean scores in Poland and Portugal can be largely attributed to a decline in performance across most of the distribution in Portugal, and amongst weaker students in Poland. By contrast, weaker students improved between 2018 and 2022 in Peru, leading to an improvement in mean score over the period (Table IV.B1.2.1 and Table IV.B1.3.3).

The standard deviation of the performance distribution, which measures how differently students in a country or economy perform, increased between 2012 and 2022, but decreased between 2015 and 2022, on average across OECD countries and economies with valid data for each pair of years. These general trends were also observed in most individual countries and economies. Indeed, there was an increase in the disparity of performance amongst students in Czechia and Poland between 2012 and 2022. There was no significant change in the standard deviation of the performance distribution among other countries and economies that took part in both assessments. There was either no significant change or a decrease in the disparity of performance amongst students in each country and economy that took part in both the 2015 and 2022 PISA financial literacy assessments (Table IV.B1.3.4). There was no significant change in the standard deviation of the performance distribution on average across OECD countries and economies between 2018 and 2022. Similarly, the interdecile range, which also provides a measure of the disparity among students in a country or economy, increased between 2012 and 2022, decreased between 2015 and 2022, and did not change significantly between 2018 and 2022.

Gender differences in performance in financial literacy

From a policy perspective, one of the most important student characteristics is gender: it neatly divides the student population into (nearly) equal halves. Gender differences in other subjects are examined and identified in PISA 2022 Results (Volume I): The State of Learning and Equity in Education (OECD, 2023[1]). To what extent do they also exist in the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment?

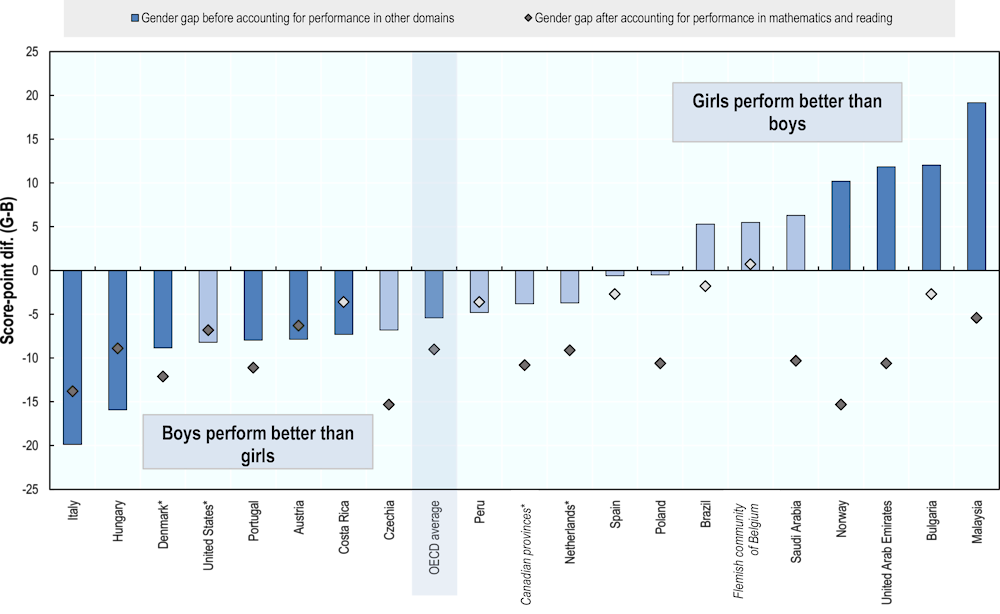

At the individual country or economy level, boys performed better than girls in Austria, Costa Rica, Denmark*, Hungary, Italy and Portugal (by between 7 and 20 score points), and girls outperformed boys in Bulgaria, Malaysia, Norway and the United Arab Emirates (by between 10 and 19 score points). There was no significant difference in the other 10 participating countries and economies. On average across OECD countries and economies, boys scored five points higher than girls in the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment, but there was no gender difference on average across all countries and economies that participated in the assessment (Figure IV.3.2).

Figure IV.3.2. Gender differences in financial literacy performance

Score-point difference between girls and boys

Note: Statistically significant gender differences are shown in a darker tone (see Annex A3).

Countries are ranked in ascending order of the gender gap in financial literacy performance before accounting for performance in other domains.

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 Database, Table IV.B1.3.8.

Although statistically significant, the five score points gender difference observed on average across OECD countries and economies is small - relative to a median score of 499 for girls and 505 for boys - and does not reflect a notable disparity in the types of tasks that boys and girls are able to do. This is especially true given the large variation in performance observed amongst both boys and girls. On average across OECD countries and economies, the standard deviation of boys’ performance in financial literacy (103 points) was 10 points wider than that of girls’ performance (93 points). The performance distribution amongst boys was wider than that amongst girls in all the 20 participating countries and economies (Table IV.B1.3.6).

Compared to girls, boys were over-represented at both ends of the performance distribution. On average across OECD countries and economies, there were more top-performing boys than top-performing girls (12% compared to 9%; a gap of 3 percentage points), but also more low-achieving boys than low-achieving girls (19% compared to 17%; a gap of 2 percentage points) (Table IV.B1.3.7). Hence, although boys have a small performance advantage over girls in financial literacy, on average across OECD countries and economies, there is still a need for financial education programmes and policies to improve the skills of both low-performing boys and girls.

As discussed in Chapter 2, student performance in mathematics, reading and financial literacy is closely linked. How much of the gender gap described above can be ascribed to elements related solely to financial literacy?

On average across OECD countries and economies and, indeed, in all participating countries and economies in PISA 2022, girls outperformed boys in reading. By contrast, on average across OECD countries and economies, boys outperformed girls in mathematics. Boys outperformed girls in mathematics in 13 of the 20 countries and economies that took part in the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment (Austria, Brazil, the Canadian provinces*, Costa Rica, Czechia, Denmark*, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands*, Peru, Portugal, Spain and the United States*), although girls outperformed boys in Malaysia and the United Arab Emirates. There were no significant differences between boys and girls in mathematics performance in the other countries and economies that participated in the assessment of financial literacy (OECD, 2023[1]).6

Once performance in both mathematics and reading were accounted for, boys scored nine points higher than girls in financial literacy, on average across OECD countries and economies (eight points higher, on average across all participating countries and economies). These nine score points represent the gender gap that is associated with the elements of financial literacy that are unique to that subject (as opposed to those that are shared with mathematics and/or reading) (Figure IV.3.2 and Table IV.B1.3.8).

On average across the OECD countries that participated in both the PISA 2018 and 2022 financial literacy assessments there was no significant difference in the gender gap in financial literacy performance nor in the proportion of high and low performers among boys and girls (Table IV.B1.3.9 and Table IV.B1.3.10). Trends in the gender differences in financial literacy performance for countries that participated in PISA 2012 and 2022, or in PISA 2015 and 2022 are presented in Annex B1 (Table IV.B1.3.9 and Table IV.B1.3.10).

The relationship between students’ socio-economic status and performance in financial literacy

Various authors have shown how financial literacy amongst young people is associated with certain demographic and socio-economic factors, such as parents’ educational attainment, household income and household possessions (Endro et al., 2019[2]; Lusardi, Mitchell and Curto, 2010[3]; Riitsalu and Põder, 2016[4]; Cameron et al., 2014[5]; OECD, 2024[6]; Anders, Jerrim and Macmillan, 2023[7]). The size and strength of this correlation – that is, the difference in financial literacy performance between students from different backgrounds, and the extent to which financial literacy performance depends on (or can be predicted by) a student’s background – are both indicative of the equity of an education system.

As a concept, the socio-economic status of a student (and his/her household) encapsulates the financial, social, cultural and human-capital resources available to students (Cowan et al., 2012[8]). PISA summarises socio-economic status through the index of economic, social and cultural status (ESCS). This index is a single value derived from several self-reported values related to the student’s family background, grouped into three components – parents’ education, parents’ occupations and home possessions – that can be taken as proxies for material wealth or cultural capital (e.g. a car, a quiet room in which to work, access to the Internet and the number of books in the home). The ESCS index was standardised to have a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1, on average across OECD countries.7

The countries and economies that took part in the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment spanned the entire socio-economic spectrum, from a high national mean value of the ESCS index of 0.52 (Norway) to a low of -1.15 (Peru) (OECD, 2023[1]). Different national standards can confound comparisons of students of different socio-economic status across countries and economies. Hence, this section compares students of different socio-economic status within countries and economies. Students in each country and economy were classified as advantaged (in their national context) if they fell within the top quarter (25%) of the ESCS distribution in their country or economy; they were classified as disadvantaged if they fell within the bottom quarter of the ESCS distribution in their country or economy.

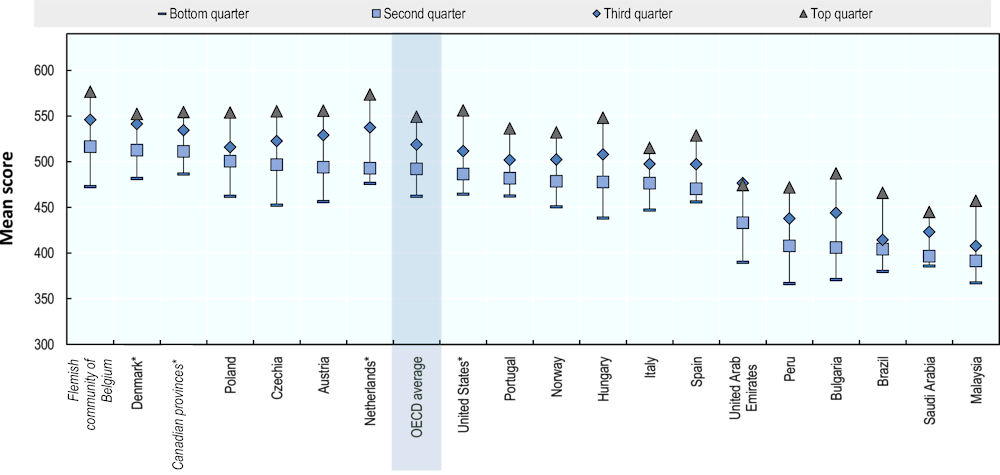

In every country and economy that participated in the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment and had valid data on socio-economic status, advantaged students performed significantly better than disadvantaged students; this was also observed in other subjects. On average across OECD countries and economies, advantaged students scored 87 score points higher than disadvantaged students, which is more than one proficiency level (equal to 75 score points). The gap between advantaged and disadvantaged students in the Flemish community of Belgium, Bulgaria, Czechia, Hungary and Peru was greater than 100 score points, while the gap was less than 75 score points in the Canadian provinces*, Denmark*, Italy, Portugal, Saudi Arabia and Spain (Figure IV.3.3).

Figure IV.3.3. Mean performance in financial literacy, by national quarter of socio-economic status

PISA index of economic, social and cultural status (ESCS)

Countries and economies are ranked in descending order of financial literacy performance for students in the second quarter of national socio-economic status.

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 Database, Table IV.B1.3.11.

Every one-unit increase in the ESCS index was associated with an increase of 37 score points in the financial literacy assessment, on average across OECD countries and economies. The improvement in performance associated with a one-unit increase in the index was roughly 45 score points in Czechia (46 points), Hungary and the Netherlands* (45 points) and the Flemish community of Belgium (44 points). It was also larger than the OECD average in Austria, Bulgaria, Denmark*, Poland and the United Arab Emirates. The smallest improvement in performance associated with a one-unit increase in the ESCS index was observed in Saudi Arabia (22 score points) (Table IV.B1.3.12). These values represent the slope of the socio-economic gradient.

The strength of the socio-economic gradient, on the other hand, represents the extent to which a student’s socio-economic status is associated with his or her performance in financial literacy. Specifically, it is the proportion of the variance in financial literacy explained by socio-economic status. A proportion of 100% means that there is a perfect correlation between socio-economic status and financial literacy score: if one knows the student’s socio-economic status, one can determine his or her financial literacy score with complete certainty, as it is perfectly explained. At the other end of the spectrum, a proportion of 0% means that there is no correlation between socio-economic status and financial literacy score: one would not be able to predict a student’s financial literacy score with any more certainty by knowing his/her socio-economic status.8

On average across OECD countries and economies, the variation in students’ socio-economic status explained 12% of the variation in students’ performance in financial literacy. A student’s socio-economic status explained relatively little of his/her performance in financial literacy in the Canadian provinces*, Norway and the United Arab Emirates (all 7%), and Saudi Arabia (8%), while it explained a larger proportion of performance in the Flemish community of Belgium (17%), Bulgaria and Hungary (both 18%), and Peru (19%) (Table IV.B1.3.12).

As discussed above, there were large differences in average performance between students of different socio-economic status within a country or economy, i.e. the slope of the socio-economic gradient corresponded to substantial differences in what the average student could do at different levels of the ESCS index. However, the fact that roughly 90% of student performance remained unexplained after accounting for socio-economic status indicates that there is still much variation in financial literacy performance amongst students of the same socio-economic status. Thus, many factors beyond socio-economic status influence students’ performance in financial literacy.

On average across OECD countries and economies, socio-economic status explained a similar amount of the variation in performance in financial literacy as it did in reading (both 12%), but less than it did for mathematics (15%) (Table IV.B1.3.13).

Differences in performance in financial literacy associated with school location

Research as well as previous PISA results appear to indicate that students in rural areas tend to have lower financial literacy levels compared to students in urban areas (Ali et al., 2016[9]; OECD, 2017[10]; 2020[11]). Opportunities to acquire financial skills in financial literacy and other subjects might be related to where students live, which can be approximated by their school’s location: whether students attend school in an urban, town or rural area. Larger communities may offer a greater opportunity to be exposed to a variety of financial products than smaller communities, simply based on their size. For example, students in cities might be more likely than students in towns or villages to pass by bank branches or to see advertisements for financial products and services, and thus be more likely to have a bank account and to hold financial products and services. Is the potentially greater familiarity with financial decision making amongst urban students still reflected in their financial literacy performance in PISA 2022?

On average across the 14 OECD countries and economies that took part in the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment, some 7% of students attended schools in a village, hamlet or rural area (a place with fewer than 3 000 inhabitants) as opposed to 60% who attends schools in towns (of between 3 000 and 100 000 inhabitants) and 33% who attended schools in cities or urban areas (of 100 000 inhabitants or more). Across the 20 participating countries and economies, 8% attended school in a rural area, 53% in a town and 39% in urban areas (Table IV.B1.3.14).

Students in rural areas scored 473 points in the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment, on average across OECD countries and economies, while students in towns and urban areas scored 494 and 509 points, respectively. The urban-rural score gap was 33 points, on average across OECD countries and economies, 42 points on average across all countries and economies that took part in the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment. However, students in urban areas were generally of higher socio-economic status than students in rural areas. Once this was accounted for, the performance gap shrank to 19 score points, on average across OECD countries and economies. In Hungary and the United Arab Emirates, this gap was 62 and 76 points respectively, after accounting for students’ socio-economic status (Table IV.B1.3.15).

Results related to school location, after accounting for performance in mathematics and reading, and to programme orientation (i.e. general vs. vocational/pre-vocational) are available in the tables in Annex B.

The relationship between performance in financial literacy and immigrant background

Many of the countries and economies that participated in the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment have long-standing and/or growing immigrant communities. Students with an immigrant background often face challenges in their progress through education, from difficulties with the language of instruction, to limited familiarity with the education system of the host country and to lower socio-economic status. Being financially literate can help immigrants integrate more easily into their new country of residence, through greater awareness and use of formal financial products and services, including remittances (OECD, 2015[12]). To what extent is the financial literacy of students with an immigrant background similar to that of non-immigrant students?

PISA 2022 classified students into several categories based on their and their parents’ immigrant background. Non-immigrant students were those students whose father or mother (or both) was/were born in the country where the student sat the PISA assessment, regardless of whether the student was him/herself born in that country. Immigrant students were all other students, i.e. students whose father and mother were born in a country other than the one where the student sat the PISA assessment.9 A distinction was made between two types of immigrant students:

First-generation immigrant students were foreign-born students whose parents were both foreign-born.

Second-generation immigrant students were students born in the country of assessment but whose parents were both foreign-born.

This report discusses results only for those countries and economies where, in 2022, at least 5% of students had an immigrant background. These countries and economies are, in decreasing order of the proportion of immigrant students: the United Arab Emirates, the Canadian provinces*, Austria, the United States*, the Flemish community of Belgium, Norway, Spain, the Netherlands*, Costa Rica, Portugal, Saudi Arabia, Denmark* and Italy (Table IV.B1.3.20). However, data for all countries and economies for which results can be statistically calculated (i.e. based on at least 30 immigrant students attending at least 5 different schools) are presented in tables in Annex B1.

Immigration policies vary largely across countries and economies. Even within a country, immigrant populations are diverse, coming from different countries, cultures and socio-economic circumstances. For instance, the average socio-economic status of immigrants is lower than that of non-immigrants in most countries and economies that participated in the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment (OECD, 2023[1]); however, in Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, students with an immigrant background have on average a higher economic status than non-immigrant students.10 It is important to bear this in mind when comparing gaps in performance related to immigrant background across or within countries.

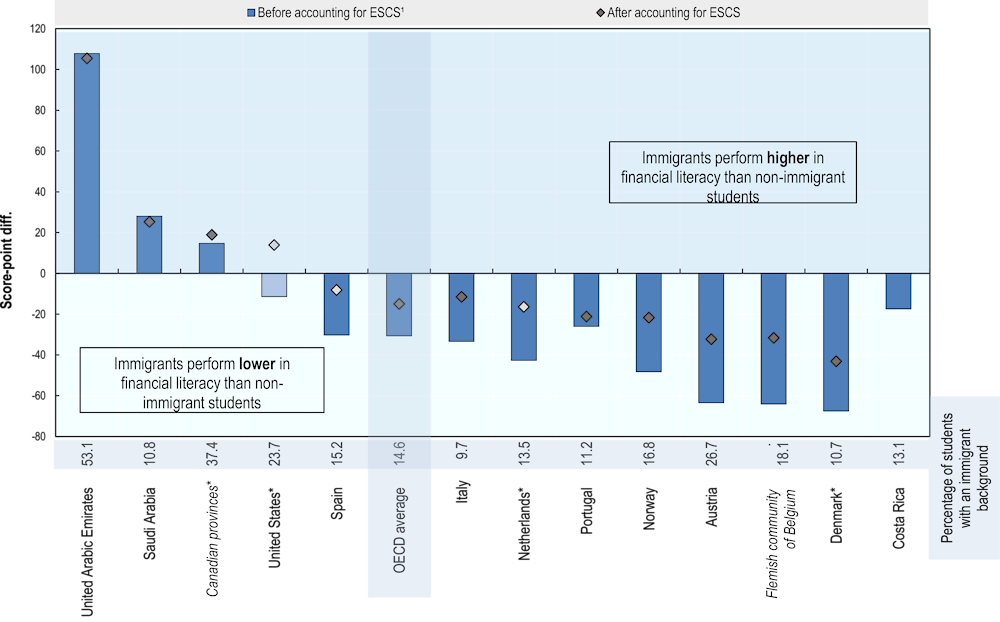

On average across OECD countries and economies, immigrant students scored 31 points lower than non-immigrant students in the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment. However, as mentioned above, immigrant students in most countries and economies come from less advantaged backgrounds than non-immigrant students. Once this was accounted for through the ESCS index, immigrant students scored 15 points lower than non-immigrant students, on average across OECD countries and economies. The gap was widest in Denmark* (43 points, after accounting for socio-economic status). Immigrant students in the United Arab Emirates scored on average 105 points higher in financial literacy than non-immigrant students, after taking their socio-economic status into account (Figure IV.3.4).

Figure IV.3.4. Financial literacy performance, by immigrant background

Score-point difference between non-immigrant and immigrant students

1. ESCS refers to the PISA index of economic, social and cultural status.

Notes: Only countries and economies where the percentage of immigrant students is higher than 5% are shown.

Statistically significant differences are shown in a darker tone (see Annex A3).

Countries and economies are ranked in descending order of the difference in financial literacy performance between non-immigrant and immigrant students, after accounting for socio-economic status.

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 Database, Table IV.B1.3.20 and Table IV.B1.3.21.

Results related to immigrant/non-immigrant background, after accounting for performance in mathematics and reading, and to language spoken at home are available in the tables in Annex B.

Table IV.3.1. Variations in students’ performance in financial literacy within countries and economies chapter figures

|

Figure IV.3.1 |

Variation in financial literacy performance between countries and economies, schools and students |

|

Figure IV.3.2 |

Gender differences in financial literacy performance |

|

Figure IV.3.3 |

Mean performance in financial literacy, by national quarter of socio-economic status |

|

Figure IV.3.4 |

Financial literacy performance, by immigrant background |

References

[9] Ali, P. et al. (2016), The Financial Literacy of Young People: Socio-Economic Status, Language Background, and the Rural-Urban Chasm.

[7] Anders, J., J. Jerrim and L. Macmillan (2023), “Socio-Economic Inequality in Young People’s Financial Capabilities”, British Journal of Educational Studies, Vol. 71/6, pp. 609-635, https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2023.2195478.

[5] Cameron, M. et al. (2014), “Factors associated with financial literacy among high school students in New Zealand”, International Review of Economics Education, Vol. 16/PA, pp. 12-21, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iree.2014.07.006.

[8] Cowan, C. et al. (2012), Improving the Measurement of Socioeconomic Status for the National Assessment of Educational Progress: A Theoretical Foundation, National Center for Education Statistics,.

[2] Endro, W. et al. (2019), “Impact of Family’s Socio-Economic Context on Financial Literacy of Young Entrepreneurs”, Expert Journal of Business and Management, Vol. 7/2, pp. 230-235, http://Business.ExpertJournals.com.

[3] Lusardi, A., O. Mitchell and V. Curto (2010), “Financial literacy among the young”, Journal of Consumer Affairs, Vol. 44/2, pp. 358-380, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6606.2010.01173.x.

[6] OECD (2024), Financial literacy in Greece: evidence on adults and young people, https://www.oecd.org/financial/education/Financial-literacy-in-Greece-evidence-adults-young-people.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2024).

[1] OECD (2023), PISA 2022 Results (Volume I): The State of Learning and Equity in Education, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/53f23881-en.

[11] OECD (2020), PISA 2018 Results (Volume IV): Are Students Smart about Money?, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/48ebd1ba-en.

[10] OECD (2017), PISA 2015 Results (Volume IV): Students’ Financial Literacy, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264270282-en.

[12] OECD (2015), “Financial Education for Migrants and their Families”, OECD Working Papers on Finance, Insurance and Private Pensions, No. 38, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5js4h5rw17vh-en.

[4] Riitsalu, L. and K. Põder (2016), “A glimpse of the complexity of factors that influence financial literacy”, International Journal of Consumer Studies, Vol. 40/6, pp. 722-731, https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12291.

Notes

← 1. More specifically, the standard deviation of a pooled sample of students from OECD countries and economies, where each national sample was equally weighted, was set at 100 score points in the PISA 2012 financial literacy assessment.

← 2. The 10th percentile is defined as the score attained by less than 10% of students (one in ten students); the other 90% of students (nine in ten students) attained a score higher than this. Likewise, the 90th percentile is the score attained by less than 90% of students (nine in ten students); the remaining 10% of students (one in ten students) attained a score higher than this.

← 3. This analysis was carried out in two steps. In the first step, the share of the variation in student performance that occurs between countries and economies was identified. In the second step, out of the remaining variation, the between school and within-school was identified. Within-school variation are differences in performance between students. The analysis reported in this chapter focuses on schools with the modal ISCED level for 15-year-old students. The reason for this restriction is the following: while the students sampled in PISA represent all 15-year-old students, whatever type of school they are enrolled in, they may not be representative of the students enrolled in their school. As a result, comparability at the school level may be compromised. For example, if grade repeaters in a country are enrolled in different schools than students in the modal grade because the modal grade in this country is the first year of upper secondary school (ISCED 3) while grade repeaters are enrolled in lower secondary school (ISCED 2), the average performance of schools where only students who had repeated a grade were assessed may be a poor indicator of the actual average performance of these schools. By restricting the sampling to schools with the modal ISCED level for 15-year-old students, PISA ensures that the characteristics of the students sampled are as close as possible to the profiles of the students attending the school.

← 4. Box IV.2.2 and Annex A5 discuss the issues involved in comparing PISA results in financial literacy over time.

← 5. Trend comparisons are only conducted for countries and economies that took part in the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment and at least one previous PISA financial literacy assessment. Italy, Poland, Spain and the United States* took part in the PISA 2012, 2015 and 2018 financial literacy assessments; Brazil and Peru took part in the PISA 2015 and 2018 financial literacy assessments; the Flemish community of Belgium participated in both the 2012 and 2015 PISA financial literacy assessments; Czechia took part in the 2012 PISA financial literacy assessment; the Netherlands* participated in the 2015 PISA financial literacy assessment; and Bulgaria and Portugal took part in the PISA 2018 financial literacy assessment. Eight Canadian provinces* participated in the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment, compared to only seven in 2015 and 2018. Therefore, results for the Canadian provinces* cannot be compared.

← 6. Gender differences shown in Table IV.B1.3.5 were calculated from students who participated in the financial literacy assessment. These results may differ from those shown in Table II.B1.7.3, which were calculated from students who participated in the core PISA assessment.

← 7. The ESCS index was standardised with respect to the 36 OECD countries that participated in the overall PISA 2022 assessment, not the subset of OECD countries that participated in the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment. These 36 countries do not include Costa Rica, for which data was missing.

← 8. The strength of the socio-economic gradient is calculated as the coefficient of determination, or R2 value, of a regression of performance over ESCS (multiplied by 100%).

← 9. The country of birth in the Canadian provinces* was considered to be Canada as a whole, not solely the eight participating provinces. In other words, students in one of the participating Canadian provinces* who had at least one parent born anywhere in Canada were considered non-immigrant students, and students in one of the participating Canadian provinces* who were born anywhere in Canada but whose parents were both born outside of Canada were considered second-generation immigrant students. Similarly, the country of birth in the Flemish community of Belgium was considered to be Belgium as a whole.

← 10. Immigrant/non-immigrant differences shown in Tables IV.B1.3.20, IV.B1.3.21 and IV.B1.3.22 were calculated from students who participated in the financial literacy assessment. This sample differs from the students who participated in the core PISA assessment, and hence the difference in mean socio-economic status between immigrant and non-immigrant students reported in this volume may differ from that shown in Table II.B1.9.1.