This chapter explores various money-related activities that students might engage in, their attitudes towards these activities, and how they are related to financial literacy. It begins by discussing the basic financial products that students hold and use, before examining the sources from which students receive their money. It then looks into students’ confidence in using traditional and digital financial services. For each of these items, the chapter explores the link between access, use, confidence and performance in financial literacy.

PISA 2022 Results (Volume IV)

7. Money and basic financial services: access, use and attitudes

Abstract

PISA defines financial literacy as not only the knowledge and understanding of, and attitudes towards, financial concepts – the focus of the previous chapters – but also “the skills, motivation and confidence to apply such knowledge and understanding in order to make effective decisions.” In other words, the goal of improving financial literacy or of financial education programmes in schools, is to ensure that students make wise financial decisions. Students start making these decisions well before they graduate from secondary school. Indeed, most 15-year-old students already make financial decisions from time to time: Should they work to make money? When they receive money, from work or gifts, should they put this money into a bank account? Should they spend this money and, if so, are they confident shopping on line?

This chapter explores students’ experiences with money and basic financial services, and how they are related to their financial literacy. The relationship between the two may run in both directions: students who are more experienced with handling money or using bank accounts might make better decisions through “learning by doing;” and students who do well on a financial literacy assessment might seek out more real-world opportunities to make financial decisions or use financial services. Which financial experiences are most common amongst 15-year-old students and most strongly related to their financial literacy?

What the data tell us

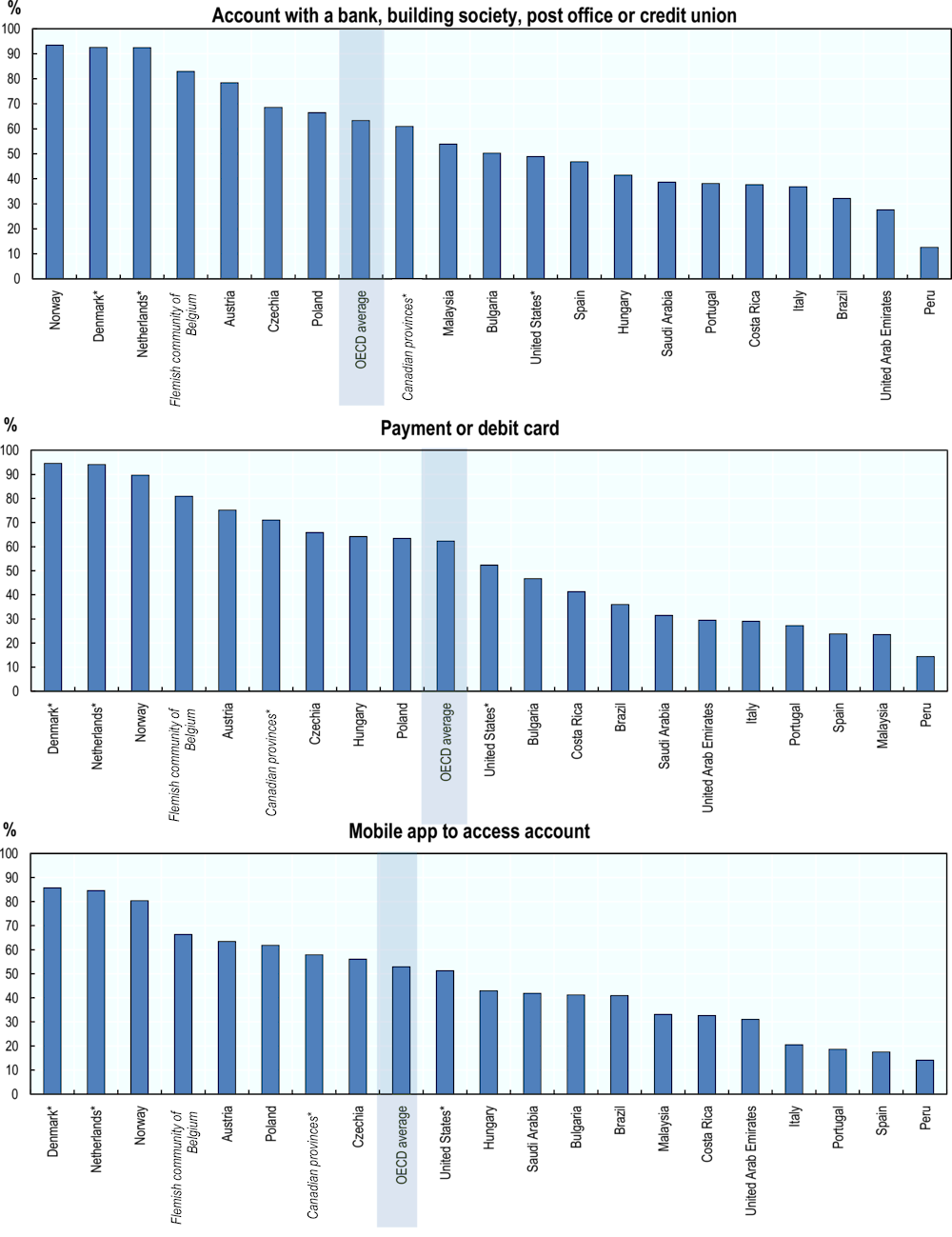

Many 15-year-old students participate in the financial system. On average across OECD countries and economies, 63% of students reported holding an account at a bank, building society, post office or credit union, and 62% of students reported holding a payment card or a debit card. Over 80% of students in the Flemish community of Belgium, Denmark*, the Netherlands* and Norway reported holding either an account or a payment/debit card, while students in Peru were amongst the least likely to hold either of these products.

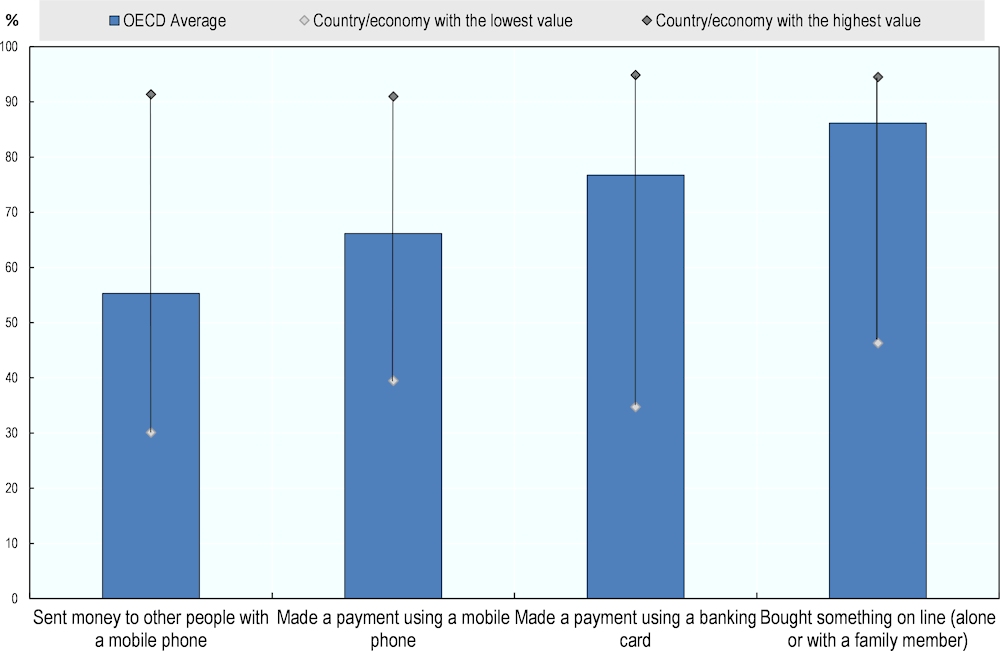

Students aged 15 also have experience with digital financial transactions. Some 86% of students on average across OECD countries and economies reported that they had bought something on line (either alone or with a family member) during the 12 months prior to the PISA assessment, and 66% of students reported that they had made a payment using a mobile phone during that period, on average across OECD and all participating countries and economies.

Students also reported receiving money from various sources. The most common source of money amongst 15-year-olds was gifts from friends or relatives: more than 80% of students received money in this way at least once a year, on average across OECD and all countries and economies.

Holding an account at a bank or at another financial institution, having bought something on line (alone or with a family member), and receiving gifts of money from friends or relatives were associated with greater financial literacy performance than not engaging in these experiences, after accounting for student characteristics and other experiences with money and basic financial products.

Students who reported that they are confident in performing several digital finance-related tasks also scored higher in the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment, after accounting for student characteristics and their experiences with money and basic financial products.

Students’ holding of basic financial products

The previous chapters looked at students’ opportunities to improve their financial literacy through conversations with their parents or through financial education at school. This section explores students’ holding of basic financial products, and whether this is related to their performance in the financial literacy assessment.

The PISA 2022 financial literacy questionnaire asked 15-year-old students whether they hold a variety of basic financial products and tools:

an account with a bank, building society, post office or credit union

a payment card or a debit card

a mobile app to access their account.

Box IV.7.1 provides some context on the provision of basic financial products to 15-year-old people, including bank accounts and payments cards, in each of the participating countries and economies.

On average across OECD countries and economies in 2022, 63% of students reported that they held an account at a bank, building society, post office or credit union; on average across all countries and economies that participated in the assessment, 55% of students held such an account. Over 90% of students in Denmark*, the Netherlands* and Norway reported that they held an account at one of these institutions, compared to only 13% of students – fewer than 1 in 8 – in Peru, and fewer than one in three students in Brazil and the United Arab Emirates (Figure IV.7.1 and Table IV.B1.7.1).

Some 62% of students, on average across OECD countries and economies, reported that they held a payment card or a debit card; on average across all countries and economies that participated in the assessment, 53% of students held such a card. Some 90% or more students in Denmark*, the Netherlands* and Norway reported that they held one of these cards, while fewer than one in four students in Peru (14%), Malaysia (23%) and Spain (24%) reported holding a payment or debit card (Figure IV.7.1 and Table IV.B1.7.1).

Holding an account at a bank, building society, post office or credit union and holding a payment or debit card tends to be positively associated within participating countries and economies. On average across OECD countries and economies, 53% of students reported that they held both an account and a card, and 24% of students reported that they held neither product, while fewer than 10% of students reported holding one product but not the other. In Denmark* and the Netherlands*, over 90% of students reported holding both an account and a card. This is not surprising as, in most cases, a payment or debit card is linked to an account. However, in Brazil, Hungary, Italy and the United States*, over 10% of students reported that they held a card but not an account (Table IV.B1.7.2). This might be due to students reporting that they do not hold an account with a bank, building society, post office or credit union in their own name, while reporting that they hold a payment card or debit card that is attached to their parents’ account.

As a proportion of account holders, 80% or more students in Denmark*, Hungary, the Netherlands*, Norway and Poland reported that they had a mobile application (“mobile app”) to access their account, compared to fewer than one in three 15-year-olds in Italy, Portugal and Spain (Table IV.B1.7.1).

Data regarding the holding of mobile apps should be interpreted with caution. For example, in Brazil, 14% of students reported that they did not hold an account, but also reported that they had a mobile app to access this (non-existent) account; and between 5% and 13% of students in another 12 countries and economies stated likewise (Table IV.B1.7.3). Students might have misinterpreted the question about mobile apps, and responded that they had a mobile app, in general, instead of a mobile app to access their bank account. Results regarding mobile apps to access students’ bank accounts are not discussed in the rest of the report, but are presented in tables in Annex B.

Figure IV.7.1. Students’ holding of basic financial products

Percentage of students who reported holding one of these financial products

Countries and economies are ranked in ascending order of the percentage of students who reported holding each financial product.

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 Database, Table IV.B1.7.1.

Box IV.7.1. Differences in national contexts with regards to the holding of basic financial products by 15-year-olds

Children aged 15 can have a savings account in all 20 participating countries and economies, and a current account in all countries and economies except Costa Rica, Malaysia and Peru.

Most countries and economies require a child’s parents to provide their consent to open a bank account. In Austria for example, children from the age of 10 can be authorised to hold an account with the consent of their legal guardians, while in Poland, it is from the age of 13, in Hungary, from the age of 14 and in Malaysia and Saudi Arabia, from the age of 15. In Costa Rica, Italy, the Netherlands*, Portugal and the United States*, parents can open an account for their child from birth. In Czechia by contrast, children can open an account independently, i.e. without their parents’ consent, from the age of 15. In Denmark*, 15-year-olds can open an account and set up (debit) payment means independently only if they earn money from work; children who do not earn their own money must have their parents open the account and card for them in the bank. Similarly, in Bulgaria, parents must consent to their child opening a bank account, but children aged 14 to 18 may dispose of their own earnings.

In some countries and economies, only parents can operate bank accounts opened in a child’s name, while in others, parents must consent to operations carried out on their child’s account. In the Flemish community of Belgium, there is no minimum legal age to open an account and to deposit money, however withdrawals are only permitted from the age of 16, or even 18 depending on parents’ consent. Conversely, in Brazil, children under the age of 16 must be assisted by their legal guardian to open any type of account but can hold and operate their account independently once it is open.

In many countries and economies, parents are ultimately responsible for activities carried out by their child on his/her bank account. In Peru, unless a child aged under 18 is emancipated, his/her parents are the legal owners of an account opened in the child’s name. In the Canadian provinces*, the Netherlands*, Norway, Portugal and Spain, there is no minimum age set by law for opening a bank account so this may vary across financial institutions, but parents are held responsible for their child’s account and have access to it until the child reaches the age of 18.

Other types of accounts held by 15-year-olds in participating countries include e-wallets in Malaysia, term-deposit accounts in Poland that can be opened from the age of 13, and securities accounts in Bulgaria.

In all participating countries and economies, except Costa Rica, Malaysia and Portugal, 15-year-olds can hold a payment card, but only in Brazil can they have a credit card linked to their account.

In Malaysia, children who have a savings account can obtain an ATM card to withdraw from their account. In Italy, parents can request the issuance of a debit card for their child from the age of 13 and can block certain categories of expenses or even request to approve transactions before they are completed. In the Netherlands*, parents are entitled to return items bought by their child with his/her debit card for a refund if the items can be considered expensive or falling outside of everyday purchases.

Most participating countries and economies, including the Flemish community of Belgium, Brazil, Bulgaria, the Canadian provinces*, Denmark*, Hungary, Italy, Malaysia, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Saudi Arabia and the United States*, allow children aged 15 to use prepaid cards, i.e. payment cards that are pre-loaded with a specified amount of money rather than linked to an account.

In all participating countries and economies, granting credit normally goes in hand with the age of majority. However, in Brazil, a credit card can be issued to an account holder below the age of 16, and in the Canadian provinces*, financial institutions may authorise 15-year-olds to be registered users on their parents’ credit card.

More fifteen-year-old boys than girls indicated that they participated in the formal financial system in some participating countries and economies. On average across OECD countries and economies, 1 percentage point more boys than girls reported holding an account at a bank, building society, post office or credit union, as did 2 percentage points more boys than girls on average across all participating countries and economies. In Austria, Brazil, Costa Rica, Hungary, Peru, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, more boys than girls reported that they held an account. Only in Norway and Spain did more girls than boys report that they held an account (Table IV.B1.7.6). Moreover, in Saudi Arabia, 12 percentage points more boys than girls reported holding a payment or debit card; a significant difference in favour of boys was observed in a further six countries and economies. However, more girls than boys in the Flemish community of Belgium, Denmark* and Norway reported holding one of these products (Table IV.B1.7.6).

More advantaged students than disadvantaged students tended to report participating in the formal financial system. Some 17 percentage points more advantaged students than disadvantaged ones reported holding an account at a bank, building society, post office or credit union on average across OECD countries and economies. This relationship was significant in all participating countries and economies with valid data. In the United States*, the gap between advantaged and disadvantaged students in holding a financial account was largest (31 percentage points) and socio-economic status explained 4% of the variation in whether students held an account. Some 13 percentage points more advantaged students than disadvantaged ones reported holding a payment or debit card, on average across OECD countries and economies. A 32 percentage-point gap between advantaged and disadvantaged students in holding a payment or debit card was observed in Bulgaria, where 4% of the variation in whether students held such a card was explained by socio-economic status (Table IV.B1.7.7).

These results are consistent with many previous studies that have found that girls and disadvantaged students participate less in the formal financial system in non-OECD countries (Maravalle and González Pandiella, 2022[1]; Adegbite and Machethe, 2020[2]; Northwood and Rhine, 2018[3]; Devlin, 2005[4]; Morsy et al., 2017[5]).

Results for immigrant and non-immigrant students are available in Annex B.

Trends in the holding of basic financial products

The financial literacy questionnaire in both PISA 2012 and 2015 asked students whether they held a bank account, and whether they held a prepaid debit card. These questions differ slightly from the wording of the questions asked in the PISA 2018 and 2022 financial literacy questionnaires; trend comparisons should therefore be made with caution. In particular, the questions in the PISA 2018 and 2022 financial literacy questionnaires are broader and might be expected to lead to greater numbers of students saying that they hold such products. Furthermore, differences in how countries and economies translated or adapted the questionnaire to their own national financial landscape might make observed differences across years more or less important. This section therefore focuses on differences between 2022 and 2018, and differences with respect to 2015 and 2012 are presented in tables in Annex B.

On average across the OECD countries and economies that participated in both PISA 2018 and 2022 assessments, there was a 2-percentage point increase in the proportion of students who reported that they held an account with a bank, building society, post office or credit union. Across all countries and economies that participated in both assessments, the increase was of 4 percentage points. These modest average increases hide large differences across countries and economies, as more students reported holding an account in 2022 than in 2018 in Poland (by 32 percentage points), in Bulgaria (by 14 percentage points) and in Brazil (by 4 percentage points), whereas fewer students reported holding an account in 2022 than four years before in Italy and Portugal (by 7 percentage points) and in Spain (by 8 percentage points) (Table IV.B1.7.4).

In every country/economy that took part in PISA 2022 and 2018, more students reported holding a payment card or debit card in 2022 than in 2018, except for Italy. On average across the OECD countries and economies that participated in both PISA 2018 and 2022, more students reported holding a payment/debit card in 2018 than in 2022 (by 10 percentage points), with the largest increase observed in Poland (26% in 2018 and 63% in 2022) (Table IV.B1.7.5).

Students’ use of basic financial products and digital transactions

In addition to exploring the holding of basic financial products by young people, PISA 2022 also attempts to understand how much they use them. On average across OECD countries and economies, 77% of students reported that they made a payment using a bank card in the 12 months prior to the survey. This percentage narrowed to 73% across all participating countries and economies, and ranged from 35% in Peru to 95% in the Netherlands* (Table IV.B1.7.9).

Young people also spend time on digital devices. They can undertake a variety of activities on line, from communicating with their friends, to obtaining information from reputable (or less reputable) websites, to, most relevant for this report, engaging in various transactions that involve the exchange of money. The PISA financial literacy questionnaire asked students whether they had, in the previous 12 months, carried out the following digital financial transactions:

bought something on line (either alone or with a family member)

made a payment using a mobile phone

sent money to other people with a smartphone (i.e. mobile phone with Internet access).

On average across OECD countries and economies in 2022, 86% of students reported they bought something on line, either alone or with a family member, over the previous 12 months (83% across all participating countries and economies). This proportion exceeded 80% in 16 of the 20 participating countries and economies and reached 95% of students in Denmark*. By contrast, only 46% of students in Peru reported that they bought something on line over the previous 12 months (Figure IV.7.2 and Table IV.B1.7.9).

Some 66% of students, on average across OECD as well as all participating countries and economies, reported they made payments using a mobile phone over the previous 12 months. Some 91% of students in Denmark* had made a payment using a mobile phone during that period, as did more than 50% of students in all other participating countries, except in Peru (40%) (Figure IV.7.2 and Table IV.B1.7.9).

Sending money to other people using a smartphone was less common amongst students: 55% of students on average across both OECD and all participating countries and economies had done so in the 12 months prior to the survey. There were large differences among countries, with fewer than one in three students in Italy, Peru, Portugal and Spain who reported having done so, compared to more than four in five students in Denmark*, the Netherlands* and Norway (Table IV.B1.7.9). However, caution may be required when analysing responses to this question as students from different countries and economies or from different socio-economic backgrounds may have interpreted it in different ways depending on the types of money transfers by smartphone that are available in their country/economy or that are common among their group, including possibly remittances.

Figure IV.7.2. Students with experience in digital financial transactions

Percentage of students reporting they have experience in the following types of digital financial transactions over the previous 12 months; OECD average

Bars are ranked in ascending order of the percentage of students who reported having experienced each type of digital financial transaction over the previous 12 months.

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 Database, Table IV.B1.7.9.

Students who reported holding an account with a bank, building society, post office or credit union reported having experience with digital financial transactions more than those without an account. On average across OECD countries and economies, students with an account reported having made a payment using a bank card in the 12 months prior to the survey more (by 20 percentage points), having sent money to others using a smartphone more (by 16 percentage points), having made a payment using a mobile phone more (by 12 percentage points) and having bought something on line more (by 8 percentage points). In no country/economy did more students without an account than those with an account report having experience in any of the digital financial transactions (Table IV.B1.7.10).

More boys than girls reported having experience with digital financial transactions such as making payments using a bank card or a mobile phone or sending money to others using a smartphone (Table IV.B1.7.11):

Slightly fewer girls than boys reported having made a payment using a bank card on average across OECD countries and economies, by 1 percentage point. The difference was in favour of boys and significant in 10 countries and economies, and reached 14 percentage points in Peru and 11 percentage points in Costa Rica. However, this difference was in favour of girls in the Flemish community of Belgium, the Netherlands* and Norway, and not significant in the remaining seven countries and economies.

More boys than girls (by 8 percentage points), on average across OECD countries and economies, reported having sent money to someone using a mobile phone over the previous 12 months. This difference was significant in favour of boys in 15 of the 20 participating countries and economies, and exceeded 15 percentage points in Austria, Bulgaria, Hungary, Italy, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

More boys than girls (by 7 percentage points), on average across OECD countries and economies, reported having made a payment using a mobile phone over the previous 12 months. This difference was significant in favour of boys in every participating country/economy except in the Flemish community of Belgium and Denmark*, where the difference was not significant.

On average across OECD countries and economies, there was no gender difference in the frequency of having bought something on line (either alone or with a family member) over the previous 12 months. The gender gap was significant in favour of girls in 5 of the 20 countries and economies that participated in the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment, it was in favour of boys in 4 more countries and economies and was not statistically significant in the other countries and economies. (Table IV.B1.7.11).

More advantaged students than disadvantaged ones (by 4 percentage points) on average across OECD countries and economies, reported having made a payment using a bank card. Across all participating countries, this difference was 8 percentage points, and reached 36 percentage points in Peru and 22 percentage points in Brazil. In Hungary however, 7 percentage points more disadvantaged students reported having made a payment using a bank card in the 12 months prior to the survey. (Table IV.B1.7.12).

More students from advantaged backgrounds than those from disadvantaged families reported having bought something on line (alone or with a family member) during the previous 12 months. The difference between advantaged and disadvantaged students in this activity was 8 percentage points, on average across OECD countries and economies, and was significant (in favour of advantaged students) in every participating country/economy. The disparity between the two groups of students was particularly large in Brazil and Peru (25 percentage points or more) (Table IV.B1.7.12).

Slightly more advantaged students than disadvantaged ones (by 2 percentage points), on average across OECD countries, reported having made a payment using a mobile phone over the previous 12 months. A significant difference was observed in nine countries and economies in favour of advantaged students, including Brazil and Peru where it reached 20 percentage points or more. In Austria and Hungary, more disadvantaged students than advantaged ones – by between 6 and 8 percentage points - reported having made a payment using a mobile phone; no significant difference was observed in other participating countries or economies (Table IV.B1.7.12).

There was no clear association between socio-economic background and sending money to others using a smartphone over the 12 months prior to the survey. More advantaged students (by 3 percentage points) reported having done so on average across all participating countries and economies, and this difference was significant in favour of advantaged students in 10 countries and economies, but there was no significant difference on average across OECD countries and economies, and the difference was in favour of disadvantaged students in Bulgaria, Hungary and Italy (Table IV.B1.7.12).

Results for immigrant and non-immigrant students are available in Annex B.

Students’ sources of money

Previous research, including from the PISA 2015 and 2018 financial literacy assessments, has shown that students receive money both as a gift from people they know and from their own work activity (Doss, Marlowe and Godwin, 1995[6]; Institut pour l’Éducation Financière du Public, 2006[7]; Mangleburg and Brown, 1995[8]; IPSOS, 2017[9]). In all countries and economies participating in the 2022 PISA financial literacy assessment, except Brazil (Ministerio do Trabalho e Previdencia, 2020[10]) and Spain (Servicio Público de Empleo Estatal, 2021[11]), students aged 15 are allowed to work under certain conditions defined by national, provincial, regional or state labour laws. Furthermore, young people increasingly continue to receive financial support from their families well into adulthood (Rachel Minkin et al., 2024[12]; Barroso, Parker and Fry, 2019[13]; Fingerman, 2017[14]; Fingerman et al., 2015[15]). Looking at the sources of money received by students may also provide insights into the relationship between money and financial literacy for 15-year-olds.

Students who sat the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment were therefore asked about the frequency [never or almost never; about once or twice a year; about once or twice a month; about once or twice a week; every day or almost every day] with which they receive money from the following sources:1

an allowance or pocket money for regularly doing chores at home

an allowance or pocket money without having to do any chores

working outside school hours (e.g. a holiday job or part-time work)

working in a family business

occasional informal jobs (e.g. babysitting or gardening)

gifts from friends or relatives

selling things (e.g. at local markets or on eBay).

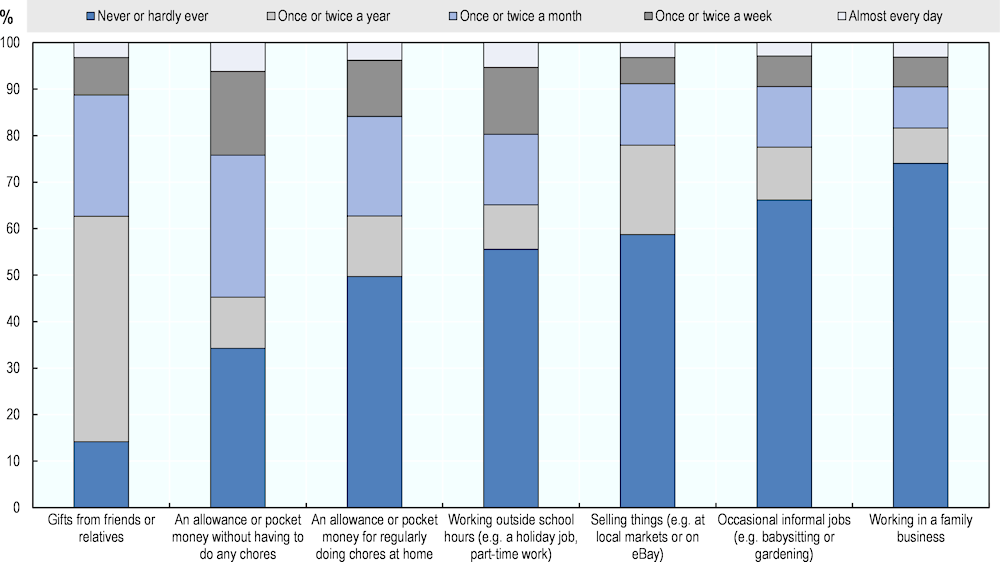

On average across OECD and all countries and economies, the most common source of money amongst 15-year-olds was gifts from friends or relatives. Some 86% of students reported receiving money as a gift from friends or relatives at least once a year, on average across OECD countries and economies (82% of students on average across all participating countries and economies) (Figure IV.7.3 and Table IV.B1.7.14).

Figure IV.7.3. Students receiving money from various sources

Percentage of students who reported receiving money from the following sources; OECD average

Items are ranked in ascending order of the percentage of students reporting that they never or hardly ever receive money from each source.

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 Database, Table IV.B1.7.14.

On average across OECD countries and economies, a majority of students reported receiving money at least once a year, as an allowance or pocket money (Figure IV.7.3 and Table IV.B1.7.14):

almost two thirds (66%) of students without having to do any chores

some 50% of students for regularly doing chores at home.

A minority of students received money at least once a year from working or related activities, on average across OECD countries and economies (Figure IV.7.3 and Table IV.B1.7.14):

some 44% of students from working outside school hours (e.g. a holiday job or part-time work)

some 34% of students from working at occasional informal jobs (e.g. babysitting or gardening)

some 26% of students from working in a family business

some 41% of students from selling things (e.g. at local markets or on eBay).

Receiving money from certain sources was associated with holding an account. On average across OECD countries and economies, more students who reported receiving money at least once a year from the following sources reported holding an account at a bank, building society, post office or credit union (Table IV.B1.7.15):

Gifts from friends and relatives (by 8 percentage points): this difference was significant in 17 countries and economies and reached 18 percentage points in the Flemish community of Belgium.

An allowance or pocket money without having to do any chores (by 5 percentage points): this difference was significant in 13 countries and economies, but fewer students receiving money at least once a year from this source in the Canadian provinces*, Denmark* and Norway reported holding an account.

Working outside school hours (e.g. a holiday job or part-time work) by 4 percentage points: this difference was significant in 9 countries and economies and reached 21 percentage points in the United States*, but it was negative in Bulgaria, Norway and Poland.

Selling things (e.g. at local markets or on eBay) by 4 percentage points: this difference was significant in 11 countries and economies, but fewer students receiving money at least once a year from selling things in Norway reported holding an account.

The link between receiving money at least once a year from working in the family business or from an allowance or pocket money for regularly doing chores at home and holding an account was less consistent across countries and economies (Table IV.B1.7.15).

On average across OECD countries and economies, more boys than girls reported receiving money (Table IV.B1.7.16):

For their work in a family business (by 13 percentage points): more boys than girls reported receiving money by working for the family business in all 20 participating countries and economies, and the difference ranged from 31 percentage points in Saudi Arabia to 8 percentage points in Peru.

For selling things (by 12 percentage points): this was observed in all participating countries, and the difference ranged from 31 percentage points in Saudi Arabia and 21 percentage points in Hungary to 5 percentage points or less in the Flemish community of Belgium and Poland.

For their work outside school hours (by 9 percentage points): the gap was significant in 17 of the participating countries and economies, and was highest in Saudi Arabia (30 percentage points), Malaysia (21 percentage points) and Costa Rica (19 percentage points).

From an allowance for regularly doing chores at home (by 5 percentage points): this was observed in 12 participating countries, the largest difference in favour of boys being observed in Hungary (12 percentage points) and Costa Rica (10 percentage points). In Norway, more girls than boys reported receiving money for doing chores at home (by 3 percentage points), and there was no significant gender difference in the Flemish community of Belgium, the Canadian provinces*, Denmark*, Malaysia, Peru, Spain and the United States*.

From occasional informal jobs (by 4 percentage points): this was also observed in 12 countries, with differences reaching 29 percentage points in Saudi Arabia and 16 percentage points in Bulgaria. However, girls reported receiving money from occasional informal jobs more than boys in the Flemish community of Belgium (by 9 percentage points), Peru (by 6 percentage points), and the Netherlands* (by 6 percentage points) and the gender gap was not significant in 5 participating countries.

However, on average across OECD countries and economies, more girls than boys reported receiving money (Table IV.B1.7.16):

From gifts (by 4 percentage points): girls in 13 participating countries reported receiving money from this source more than boys, and the difference was not significant in Brazil, Bulgaria, the Netherlands*, Peru, Poland, Portugal and Saudi Arabia.

From an allowance without having to do any chores (by 3 percentage points): but there were large variations across countries –the gap was in favour of boys in Brazil and Italy - and the gender difference was not significant in 11 of the 20 participating countries.

Overall, these results suggest that more boys than girls receive money in exchange for work inside and outside the household, while in some countries and economies more girls than boys receive money without working, in the form of allowances or gifts. These results might indicate that boys begin to seek ways of becoming more financially independent by working either formally, informally or for the family business, at an earlier age than girls. Results might also indicate that more girls than boys do not get paid for their work, or a combination of both aspects. More data would be needed to understand the reason for these observed gender differences.

More advantaged students2 than disadvantaged students reported receiving money from gifts (by 10 percentage points) and from an allowance without having to do any chores (by 4 percentage points), on average across OECD countries and economies. By contrast, disadvantaged students more frequently reported receiving money from working, either in the family business (by 7 percentage points), or outside school hours (by 5 percentage points), on average across OECD countries and economies (Table IV.B1.7.17).

Overall, the relationship between receiving money from different sources and students’ socio-economic status suggests that advantaged students can receive money from their families, in the form of gifts or allowances, without the need to work, while disadvantaged students may need to earn money from work to pay for some of their own expenses.

Results for immigrant and non-immigrant students are available in Annex B.

Students’ confidence in using financial services, including digital ones

The PISA 2022 financial literacy questionnaire asked students about their confidence in dealing with money matters, whether traditional or digital. In particular, it asked students whether they feel not at all confident, not very confident, confident or very confident about traditional money matters, such as:

making a money transfer (e.g. paying a bill)

filling in forms at the bank

understanding bank statements

keeping track of [their] account balance.

The PISA 2022 financial literacy questionnaire also asked students if they feel not at all confident, not very confident, confident, or very confident about dealing with the following digital financial services, i.e. when using digital or electronic devices outside of the bank (e.g. at home or in shops):

transferring money

keeping track of their balance

paying with a debit card instead of using cash

paying with a mobile device (e.g. mobile phone or tablet) instead of using cash

ensuring the safety of sensitive information when making an electronic payment or using online banking.

For each set of questions, students’ responses were aggregated into an overall index of confidence in dealing with traditional money matters3 or with digital financial services. Each index was standardised to have a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1 across OECD countries and economies.

Students in Austria and the Netherlands* were the most confident4 in dealing with traditional money matters; at the other end of the scale, students in Italy, Malaysia, Peru and Spain reported particularly low levels of confidence in dealing with traditional money matters (Table IV.B1.7.19). Similarly, when looking at confidence using digital financial services,5 students in the Netherlands* were the most confident, followed by students in Denmark* and Norway. The least confident students in using digital financial services were found in Italy, Malaysia and Peru (Table IV.B1.7.23).

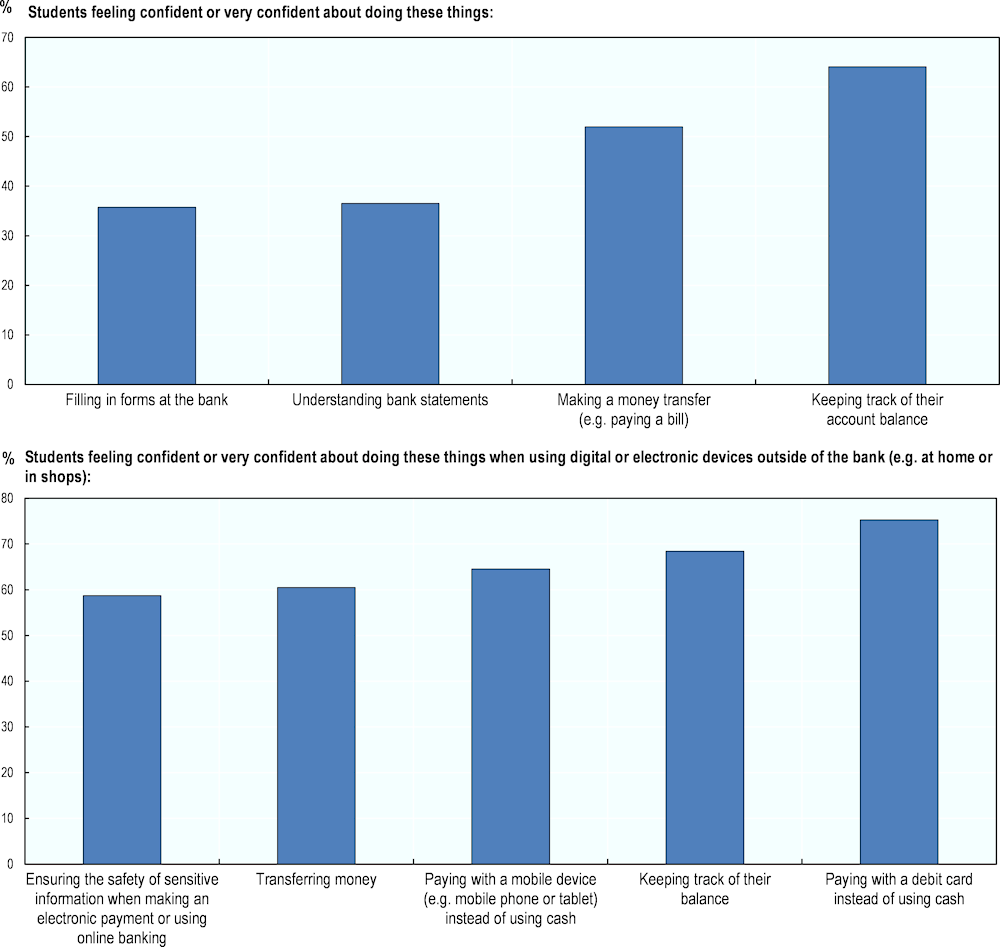

When looking at confidence in each of the four traditional money matters (Figure IV.7.4 and Table IV.B1.7.19):

Large majorities of students reported feeling confident in keeping track of their account balance (64% on average across OECD countries and economies, and 61% on average across all countries and economies). Over 70% of students in Austria, the Canadian provinces*, Czechia, Denmark*, the Netherlands*and the United States*reported feeling confident about keeping track of their account balance. However, less than 45% of students in Italy, Hungary and Peru were similarly confident.

Some 52% of students, on average across OECD countries and economies, reported feeling confident in making a money transfer (e.g. paying a bill). Over 60% of students in the Flemish community of Belgium, the Netherlands*and Poland reported feeling confident in this task, compared to less than 40% of students in Italy, Malaysia, and Spain.

Less than half of students reported feeling confident in dealing with bank documents on average across OECD countries and economies. On average across OECD countries and economies, 36% of students reported that they feel confident in understanding bank statements. Some 55% or more students in Austria and the Netherlands* reported feeling confident in understanding bank statements, but less than 30% of students in the Flemish community of Belgium, Denmark*, Hungary, Italy, Malaysia, Peru and Spain reported feeling confident in doing so. Similarly, 36% of students reported that they feel confident filling in forms at the bank, on average across OECD countries and economies. This ranged from 49% of students in the Netherlands* and Saudi Arabia to 25% of students in Peru.

When looking at confidence in using each of the five digital financial services (Figure IV.7.4 and Table IV.B1.7.23):

Students were most confident in paying with a debit card instead of using cash (75%, on average across OECD countries and economies) and in keeping track of their balance when using digital or electronic devices (68%, on average across OECD countries and economies). Some 92% of students in the Netherlands* reported feeling confident in paying with a debit card instead of using cash, as did more than 75% of students in Austria, the Flemish community of Belgium, the Canadian provinces*, Denmark*, Norway, Poland and the United States*. However, only 31% of students in Peru and 34% of students in Malaysia reported so.

More than half of all students, on average across OECD countries and economies, reported that they felt confident in ensuring the safety of sensitive information when making an electronic payment or using online banking (59%), transferring money (60%) and paying with a mobile device (e.g. a mobile phone or tablet) instead of using cash (65%). Roughly three in four students in the Netherlands* (76%) and Denmark* (74%) reported feeling confident in ensuring the safety of sensitive information, compared to 34% of students in Peru. Likewise, students in Denmark* (91%) and the Netherlands* (79%) were amongst the most confident in transferring money using digital or electronic devices, while those in Peru (37%), Malaysia and Italy (33%) were amongst the least confident. While only 37% of students in Peru and 42% of students in Malaysia reported feeling comfortable in paying with a mobile device instead of using cash, 90% of students in Denmark* and 79% of students in the Netherlands* reported the same.

Figure IV.7.4. Students’ confidence in dealing with traditional money matters and in using digital financial services

Percentage of students who reported that they are confident or very confident in performing each task; OECD average

Tasks are ranked in ascending order of the percentage of students who reported feeling confident or very confident in performing them.

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 Database, Table IV.B1.7.19 and Table IV.B1.7.23.

The questionnaire did not provide more information as to why students feel confident (or not) performing certain tasks. However, it appears that students generally feel less confident performing tasks that require actions (e.g. making a money transfer or filling in forms at the bank) or understanding documents that, in most countries, they cannot handle autonomously because of legal frameworks (e.g. bank statements). By contrast, keeping track of their account balance is an activity that students can often do without parental involvement; indeed, this may be why close to 80% of students, on average across OECD and all participating countries and economies, reported that they are responsible for their own money matters, and 15-year-old students might therefore be more experienced in these tasks (Table IV.B1.4.6).

Confidence in dealing with traditional money matters and in using digital financial services was associated with experience in holding and using basic financial products. A greater percentage of students who reported feeling confident both in dealing with traditional money matters and in using digital financial services reported holding an account at a bank, building society, post office or credit union. On average across OECD countries and economies, 15% more students in the top quarter than in the bottom quarter of confidence in dealing with traditional money matters reported holding an account, and this difference was significant in 17 of the 20 participating countries and economies. Likewise, 26% more students in the top quarter than in the bottom quarter of the index of confidence in using digital financial services reported holding an account, and this difference was significant in all participating countries and economies countries and economies (Table IV.B1.7.27).

Similarly, students who were most confident in dealing with traditional money matters and in using digital financial services reported having more experience in digital financial transactions in the 12 months prior to the assessment than those who were least confident. On average across OECD countries and economies, 22% more students in the top quarter than in the bottom quarter of the index of confidence in dealing with traditional matters reported having made a payment using a bank card, and this difference was significant in all countries and economies except in Denmark*. Compared to the least confident students in dealing with traditional money matters, 30% more of the most confident students reported having sent money to others using a smartphone, and 28% more of the most confident students reported having made a payment using a mobile phone, on average across OECD countries and economies, and the difference between the most confident students and the least confident students was significant in all participating countries and economies for these digital financial transactions (Table IV.B1.7.28). Likewise, in all participating countries and economies, students who were more confident in using digital financial services reported having more experience in digital financial transactions. The difference between the most confident and the least confident students was greater than 30% for reports of having made a payment using a bank card, having sent money to others using a smartphone and having made a payment using a mobile phone, in the 12 months prior to the assessment, on average across OECD and all participating countries and economies (Table IV.B1.7.29).

Boys were more confident than girls in dealing with each of the four traditional money matters, on average across OECD countries and economies; and, in every participating country and economy, the average boy was significantly more confident than the average girl in dealing with traditional money matters (as measured by the index of confidence in dealing with traditional money matters) (Table IV.B1.7.20). Boys were also more confident than girls in using digital financial services. The index of confidence in using digital financial services was higher amongst boys, both on average across OECD countries and economies and in 18 of the 20 countries and economies that participated in the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment. The only exceptions were the Flemish community of Belgium and Saudi Arabia, where the gender difference was not significant. The gender difference, in favour of boys, was observed for each of the five digital financial services, on average across OECD countries and economies (Table IV.B1.7.24). Such gender differences in confidence in dealing with traditional money matters and in using digital financial services may be associated with the greater tendency to hold and use basic financial products among boys than girls (Table IV.B1.7.6 and Table IV.B1.7.11).

Students’ confidence in dealing with traditional money matters generally increases with their socio-economic status, although the likelihood of feeling confident about traditional money matters does not increase across all countries and economies for all activities. While on average across OECD countries and economies, advantaged students had a greater likelihood of feeling confident about keeping track of their account balance and making a money transfer than disadvantaged students, they were also less likely to feel confident about filling forms at the bank (Table IV.B1.7.21). Advantaged students were also more likely than disadvantaged students to report that they are confident in using digital financial services. On average across OECD countries and economies, the index of confidence in using digital financial services was 0.2 of a unit higher amongst advantaged students than amongst disadvantaged students. This difference related to socio-economic status was also observed in 16 of the 20 countries and economies that examined this issue, reaching 0.7 of a unit in Peru. However, the difference was not significant in Hungary, Italy and Spain. The difference related to socio-economic status was also significant, in favour of advantaged students, for each of the five digital financial services, on average across OECD countries (Table IV.B1.7.25).

Results for immigrant and non-immigrant students are available in Annex B.

Performance in the financial literacy assessment, use and confidence in using financial products

This section examines the variations in performance in the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment according to 15‑year-old students’ holding and use of financial products, the sources from which they receive money and their confidence in dealing with traditional money matters and in using digital financial services.

Performance in the financial literacy assessment, and students’ experience with money and basic financial products

As discussed in the previous sections, students’ different types of experience with money and basic financial products – in terms of holding traditional and digital financial products, using them, and receiving money from various sources – are related to each other (Table IV.B1.7.2, Table IV.B1.7.3, Table IV.B1.7.10 and Table IV.B1.7.15). This section, therefore, considers variations in performance in financial literacy across all these different types of experiences together, after accounting for student characteristics such as gender, socio-economic status and immigrant background.

Results related to variations in performance in financial literacy by each experience with money and basic financial products separately are available in Annex B.

Performance in the financial literacy assessment and students’ holding of basic financial products

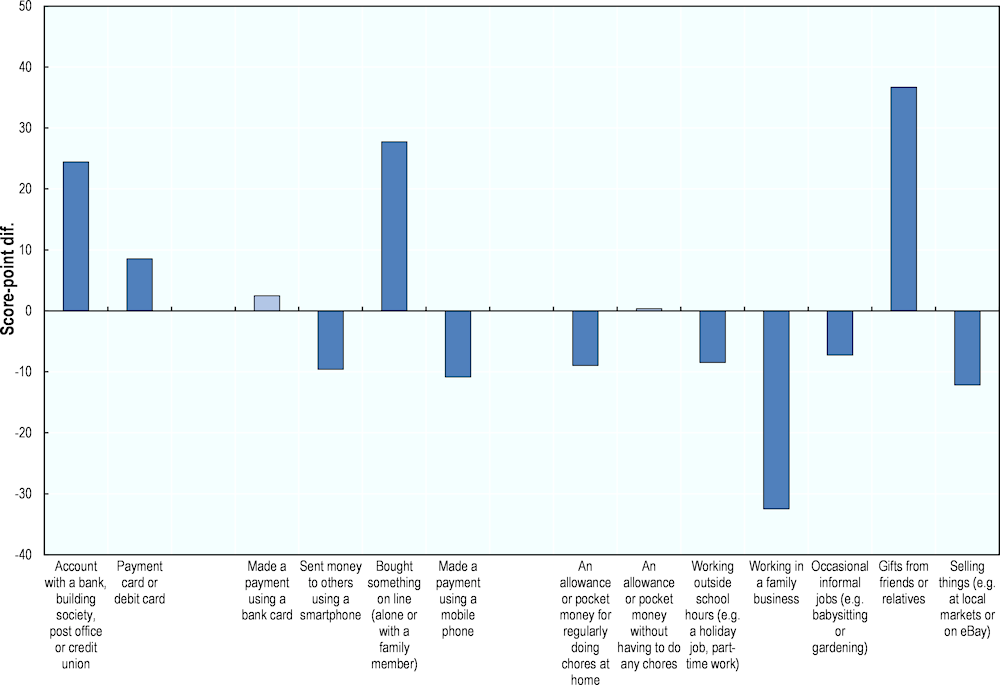

On average across OECD countries and economies participating in the 2022 PISA financial literacy assessment, students who held an account with a bank, building society, post office or credit union scored 24 points higher than students who did not hold such an account/did not know what an account is, after accounting for student characteristics, such as gender, socio-economic status, immigrant background and other experiences with money and basic financial products. This difference was positive and significant in 14 countries and economies, after accounting for student characteristics and other experiences with money. In the Netherlands*, the performance difference was 51 points wide and in Norway, it was 41 points wide. However, it is worth noting that in both countries more than 90% of students hold an account, hence the sample of students without an account is relatively small. By contrast, the performance difference was negative and significant in two countries: it reached 8 points in the United Arab Emirates and 16 points in Peru after accounting for students’ characteristics and other experiences with money (Figure IV.7.5 and Table IV.B1.7.36).

Likewise, students who held a payment card or debit card scored 9 points higher in the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment than students who did not hold such a card/did not know what such a card is, on average across OECD countries and economies, after accounting for student characteristics and other experiences with money and basic financial products. The performance difference reached 39 score points in the Netherlands* and 30 points in Bulgaria; it was significant in favour of students holding such a card in five more countries and economies. However, the performance gap was in favour of students who did not hold such a card/did not know what such a card is in Hungary, Malaysia and Peru, after accounting for student characteristics and other experiences with money (Table IV.B1.7.36).

The positive relationship between financial literacy and holding of basic financial products suggests that using a bank account may offer students the opportunity to learn about money, or that students with higher financial literacy may be more likely to engage with the formal financial system. Studies among high school students suggested that allowing students to experience with bank accounts as part of financial education school-based programmes provided an opportunity for learning (Loke, Choi and Libby, 2015[16]; Sherraden et al., 2011[17]).

Figure IV.7.5. Financial literacy performance, by students’ experience with money, basic financial products and digital transactions

Score-point difference between students who reported holding these products, having carried out these digital financial transactions, or having received money at least once a year from these sources, and students who did not, after accounting for student characteristics; OECD average

1. The socio-economic profile is measured by the PISA index of economic, social and cultural status.

Note: Score-point differences that are statistically significant are marked in a darker tone (see Annex A3).

Sources are ranked in descending order of the score-point difference between students who reported feeling confident/very confident and those who reported feeling not very confident/not at all confident, or who reported receiving money at least once a year and those never/hardly ever receiving money from a source

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 Database, Table IV.B1.7.36.

Performance in the financial literacy assessment and students’ experience with digital financial transactions

Students who had bought something on line (either alone or with a family member) scored 28 points higher in the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment than students who had not bought something on line during the previous 12 months, on average across OECD countries and economies, after accounting for student characteristics and other experiences with money. Having bought something on line was associated with greater financial literacy in 16 of the 19 participating countries and economies with valid data. The performance difference was especially large in the Netherlands* (49 score points), Poland (45 score points) and the United States* (44 score points), after accounting for student characteristics and other experiences with money (Table IV.B1.7.36).

There was no clear association between students’ performance in financial literacy and experience in having made a payment with a bank card, on average across OECD countries and economies, and after accounting for student characteristics and other experiences with money. Having made a payment with a bank card was associated with greater performance in financial literacy in 5 of the19 participating countries and economies with valid data including Saudi Arabia (by 20 points), the Flemish community of Belgium (by 18 points), Brazil (by 16 points), the United Arab Emirates (by 12 points) and Hungary (by 9 points), and lower performance in financial literacy in Malaysia (by 12 points) (Table IV.B1.7.36).

Sending money to others using a smartphone and making payments using a mobile phone were both associated with lower performance in the assessment, on average across OECD countries and economies, and after accounting for student characteristics and other experiences with money. Students who had sent money to others using a mobile phone over the previous 12 months scored 10 points lower than those who had not, on average across OECD countries and economies. A difference in favour of students who had not sent money to others using mobile phones during that period was observed in 11 of the 19 participating countries and economies with valid data, after accounting for student characteristics and other experiences with money. The difference reached 30 score points or more in the United Arab Emirates and the United States*. In the Netherlands* and Norway however, students who had sent money to others using mobile phones scored higher in financial literacy than those who had not, by about 13 score points after accounting for student characteristics and other experiences with money (Table IV.B1.7.36).

On average across OECD countries and economies, students who had made a payment using a mobile phone over the previous 12 months scored 11 points lower than those who had not, after accounting for student characteristics and other experiences with money. A difference in favour of students who had not made payments using mobile phones during that period was observed in 11 of the19 participating countries and economies with valid data, after accounting for student characteristics and other experiences with money. The difference exceeded 20 score points in the Netherlands* (Figure IV.7.5 and Table IV.B1.7.36).

These results suggest that the type of experiences that 15-year-old students have with basic financial products are varied across and within countries, and that the relationship between financial literacy and engaging with basic traditional and digital financial products is not straightforward. Depending on the financial products and services available to young people in different countries, it may be that using certain financial products, or that using them in certain ways, may provide an opportunity for students to develop their financial literacy, but that this may not be the case across using all basic financial products. It may also be that, depending on the country or local context, students with high financial literacy use basic financial products in certain ways (such as buying things on line with a family member) while low performing students use them in other ways (such as making payments using a mobile phone or sending money to others using a smartphone). It may also be that there are unobserved characteristics in the types of students who pay using bank cards or buy things on line and those who send money to others or make payments using a mobile phone, such as the fact that online shopping via a computer may provide an opportunity to discuss with parents and to learn from them to a greater extent than sending money via a smartphone. Recent studies in Australia and the United States* suggests that adults may use online shopping experiences and payment card usage as opportunities to teach their children about money matters (Williams and Willick, 2023[18]; Thaichon, 2017[19]). By contrast, a study in the United Kingdom shows that many parents are not aware of their children’s spending behaviour on line (Virgin Media O2, 2023[20]).

Performance in the financial literacy assessment and students’ sources of money

The relationship between performance in general (and financial literacy performance in particular) and earning money from small jobs is a complex one. As discussed in previous chapters, students’ performance in financial literacy may be related to students’ overall ability, to the extent to which they are exposed to formal financial education in school, and to any other opportunity for informal learning, such as discussions with parents and personal experience. Earning money from doing household chores or small jobs may be considered one such experience, as it allows young people to become familiar with the idea of work, wages and money management. At the same time, these activities may take time away from learning during after-school hours, and students from different socio-economic backgrounds may need to earn money from work to different extents (Table IV.B1.7.17).

Students’ financial literacy, as measured by performance in the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment, was positively correlated with receiving money from only one of the seven sources investigated: gifts from friends or relatives, on average across OECD countries and economies. After accounting for student characteristics, such as gender, socio-economic status and immigrant background and experiences with money, students who received money as a gift from friends or relatives scored 37 points higher in the assessment than students who did not receive money in this way on average across OECD countries and economies, and 34 points higher on average across all participating countries and economies with valid data (Table IV.B1.7.36). Gifts may be related to higher financial literacy if they provide an occasion for students to think about their saving and spending decisions, but also if high-performing students receive money as a reward for school performance.

The direction of the relationship between receiving money from an allowance or pocket money without having to do any chores was not consistent across participating countries and economies. Students receiving money from an allowance or pocket money without having to do any chores scored higher than those who did not receive money from this source in 9 participating countries and economies, but scored lower in 4 participating countries and economies, after accounting for student characteristics and experiences with money. Receiving money from an allowance or pocket money for regularly doing chores was associated with lower financial literacy performance in 10 participating countries and economies (Table IV.B1.7.36).

Receiving money from working activities or selling things was associated with lower scores in financial literacy. The largest performance gap between receiving money from a given source at least once a year and never receiving it was observed amongst students who received money by working in a family business: these students scored 32 points lower than students who did not receive money in this way on average across OECD countries and economies and 30 points on average across all participating countries and economies, after accounting for student characteristics and experiences with money (Table IV.B1.7.36). However, it is worth noting that relatively few students reported earning money from working in a family business (26% on average across OECD countries and economies) (Table IV.B1.7.14).

Working outside school hours (e.g. a holiday job or part-time work), occasional informal jobs (e.g. babysitting or gardening) and selling things (e.g. at local markets or on eBay) were all associated with lower scores in financial literacy – between 7 and 12 score points lower – compared to students who did not receive money from these sources, on average across OECD countries and economies and after accounting for student characteristics and experience with money, and between 6 and 12 points on average across all participating countries and economies. The direction of the relationship between financial literacy performance and receiving money from an allowance or pocket money without having to do any chores was not consistent across participating countries and economies (Table IV.B1.7.36).

The negative relationship between financial literacy and receiving money from working activities or selling things may be related to students’ overall ability, as there are no or very small differences in financial literacy performance associated with receiving money from any of these sources when students’ performance in mathematics and reading is also taken into account, in addition to student characteristics (Table IV.B1.7.32). The negative relationship may also be related to the different situations of students undertaking these activities, the time they spend performing them which arguably diminishes the time they can spend studying or other characteristics not captured in the PISA assessment. Moreover, these results should be interpreted with caution also because the data do not say how much money students earn from these sources, and whether students engage in any quality discussion about the money they receive with knowledgeable adult relationships, such as parents or teachers. Future research could look further into the relationship between undertaking work activities, earning money, discussing about money with parents or teachers and financial literacy.

Performance in the financial literacy assessment and students’ confidence in using financial products

As discussed in the previous sections, students’ confidence in dealing with traditional matters and in using digital financial services is associated with their experience in using financial products and services (Table IV.B1.7.27, Table IV.B1.7.28 and Table IV.B1.7.29). This section, therefore, considers variations in performance in financial literacy across levels of confidence in dealing with traditional money matters and in using financial services, after taking into account students’ experience with money and basic financial products, as well as student characteristics such as gender, socio-economic status and immigrant background (Table IV.B1.7.37).

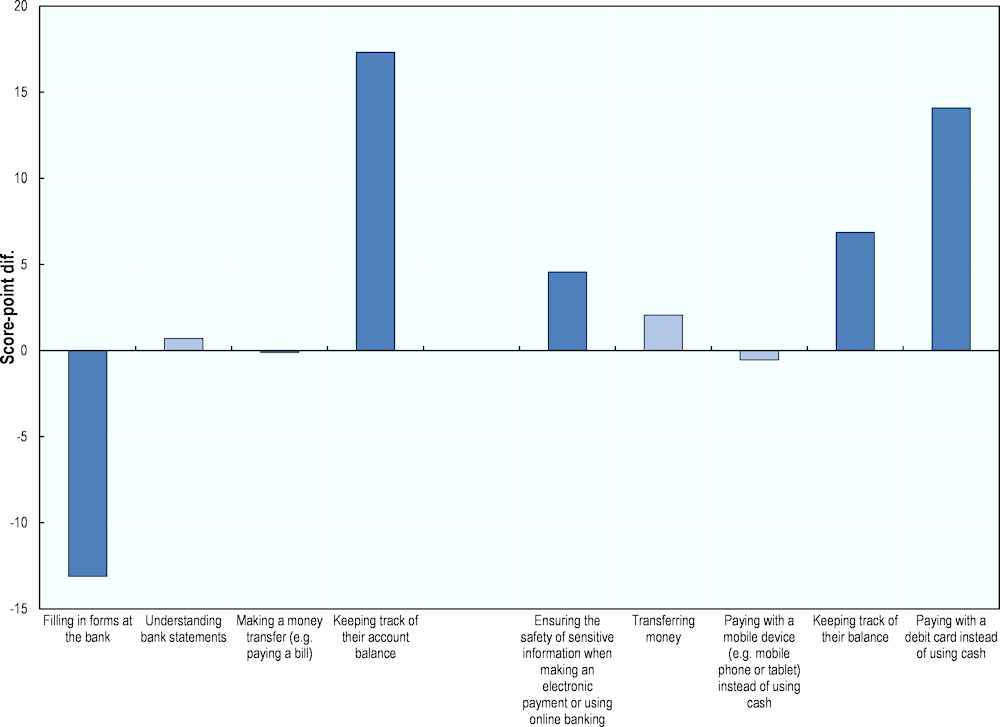

Figure IV.7.6. Financial literacy performance, by students’ confidence in dealing with traditional money matters and in using digital financial services

Score-point difference between students who reported feeling confident/very confident and those who reported feeling not very confident/not at all confident, after accounting for student characteristics and experiences with money; OECD average

1. The socio-economic profile is measured by the PISA index of economic, social and cultural status.

Note: Score-point differences that are statistically significant are marked in a darker tone (see Annex A3).

Sources are ranked in descending order of the score-point difference between students who reported feeling confident/very confident and those who reported feeling not very confident/not at all confident.

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 Database, Table IV.B1.7.38.

Students who reported that they are confident in dealing with certain traditional money matters and in using certain digital financial services also scored higher in the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment than students who are not confident (Figure IV.7.6 and Table IV.B1.7.37). Students reporting that they are confident in traditional money matters such as keeping track of their account balance scored 7 points higher in the financial literacy assessment than those who reported they are not confident, on average across OECD countries and economies, after accounting for student characteristics and experiences with money.

When using digital or electronic devices outside of the bank, students who reported they are confident in using the following digital financial services scored higher than those who reported not feeling confident, on average across OECD countries and economies, after accounting for student characteristics and experiences with money (Figure IV.7.6 and Table IV.B1.7.37):

paying with a debit card instead of using cash, by 14 points

keeping track of their balance, by 7 points

ensuring the safety of sensitive information when making an electronic payment or using online banking, by 5 points.

By contrast, students who reported that they are confident filling forms at the bank scored 13 points lower than those who reported not feeling confident performing this task, on average across OECD countries and economies, and after accounting for student characteristics and other experiences with money. This association was negative in 11 participating countries and economies. It is worth noting that only about a third of students reported feeling confident about filling forms at the bank, on average across OECD countries and economies. Further research may be needed to uncover any characteristics of students who perform this task to explain their lower financial literacy levels.

Feeling confident in transferring money digitally or in paying with a mobile device instead of cash was not associated with a difference in financial literacy performance, on average across OECD countries and economies, and after accounting for student characteristics and experiences with money (Figure IV.7.6 and Table IV.B1.7.37).

Table IV.7.1. Money and basic financial services: access, use and attitudes chapter figures

|

Figure IV.7.1 |

Students' holding of basic financial products |

|

Figure IV.7.2 |

Students with experience in digital financial transactions |

|

Figure IV.7.3 |

Students receiving money from various sources |

|

Figure IV.7.4 |

Students' confidence in dealing with traditional money matters and in using digital financial services |

|

Figure IV.7.5 |

Financial literacy performance, by students’ experience with money and basic financial products |

|

Figure IV.7.6 |

Financial literacy performance, by students' confidence in dealing with traditional money matters and in using digital financial services |

References

[2] Adegbite, O. and C. Machethe (2020), “Bridging the financial inclusion gender gap in smallholder agriculture in Nigeria: An untapped potential for sustainable development”, World Development, Vol. 127, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104755.

[13] Barroso, A., K. Parker and R. Fry (2019), Majority of Americans Say Parents Are Doing Too Much for Their Young Adult Children, http://www.pewresearch.org.

[4] Devlin, J. (2005), “A Detailed Study of Financial Exclusion in the UK”, Journal of Consumer Policy, pp. 75-108.

[6] Doss, V., J. Marlowe and D. Godwin (1995), Middle-School Children’s Sources and Uses of Money.

[14] Fingerman, K. (2017), “Millennials and Their Parents: Implications of the New Young Adulthood for Midlife Adults”, Innovation in Aging, Vol. 1/3, https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igx026.

[15] Fingerman, K. et al. (2015), ““I’ll Give You the World”: Socioeconomic Differences in Parental Support of Adult Children”, Journal of Marriage and Family, Vol. 77/4, pp. 844-865, https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12204.

[7] Institut pour l’Éducation Financière du Public (2006), Rapport d’Étude sur l’Argent et les Problématiques Financières auprès des Jeunes 15-20 Ans.

[9] IPSOS (2017), Research on Teenagers Ages 13-17 on behalf of TransUnion.

[16] Loke, V., L. Choi and M. Libby (2015), “Increasing youth financial capability: An evaluation of the mypath savings initiative”, Journal of Consumer Affairs, Vol. 49/1, pp. 97-126, https://doi.org/10.1111/joca.12066.

[8] Mangleburg, T. and J. Brown (1995), “Teens’ Sources of Income: Jobs and Allowances”, Source: Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, Vol. 3/1, pp. 33-46.

[1] Maravalle, A. and A. González Pandiella (2022), “Expanding access to finance to boost growth and reduce inequalities in Mexico”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1717, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/2de3cd7d-en.

[10] Ministerio do Trabalho e Previdencia (2020), Guidelines on Prevention of Child Labour in the COVID-19 Pandemic Context, http://www.planalto.gov.br/.

[5] Morsy, H. et al. (2017), Access to finance-mind the gender gap.

[3] Northwood, J. and S. Rhine (2018), “Use of Bank and Nonbank Financial Services: Financial Decision Making by Immigrants and Native Born”, Journal of Consumer Affairs, Vol. 52/2, pp. 317-348, https://doi.org/10.1111/joca.12150.

[12] Rachel Minkin, B. et al. (2024), Parents, Young Adult Children and the Transition to Adulthood, Pew Research Center, http://www.pewresearch.org.

[11] Servicio Público de Empleo Estatal (2021), Trabajar en España, https://www.sepe.es/HomeSepe/que-es-el-sepe/comunicacion-institucional/publicaciones/publicaciones-oficiales/listado-pub-eures/trabajar-espana/trabajar-en-espana.html.

[17] Sherraden, M. et al. (2011), “Financial Capability in Children: Effects of Participation in a School-Based Financial Education and Savings Program”, Journal of Family and Economic Issues, Vol. 32/3, pp. 385-399, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-010-9220-5.

[19] Thaichon, P. (2017), “Consumer socialization process: The role of age in children’s online shopping behavior”, Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, Vol. 34, pp. 38-47, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2016.09.007.

[20] Virgin Media O2 (2023), Over half of British parents unaware children are spending money on content creators and streamers online, https://news.virginmediao2.co.uk/over-half-of-british-parents-unaware-children-are-spending-money-on-content-creators-and-streamers-online/.

[18] Williams, D. and B. Willick (2023), “Co-shopping and E-commerce: parent’s strategies for children’s purchase influence”, Electronic Commerce Research, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10660-023-09682-9.

Notes

← 1. The question about receiving money from different sources was asked in a different way in 2022 than it was asked in 2018 and previous cycles. In PISA 2022, students were asked “Thinking of the last 12 months, how often did you get money from any of these sources?” with the option of choosing among five frequency categories. In PISA 2018 and previous cycles, students were asked “Do you get money from any of these sources?”, with the option of replying Yes or No. Comparisons should therefore be made with caution.

← 2. In PISA, advantaged students are defined as those who are in the top quarter (25%) of the socio-economic distribution of their country or economy, as measured by the PISA index of economic, social and cultural status (ESCS). Disadvantaged students are those in the bottom quarter of that distribution.

← 3. The index of confidence in dealing with traditional money matters refers to confidence making a money transfer (without specifying whether on line or in person), filling in forms at the bank, understanding bank statements (without specifying whether in paper or online format) and keeping track of one’s account balance (without specifying whether in branch or using digital tools). By contrast, the index of confidence in using digital financial services only refers to the use of digital or electronic devices outside of the bank.

← 4. Nuances in intensity between “very confident” and “confident”, and between “not at all confident” and “not very confident”, were used when mathematically constructing the indices used in this chapter. However, in this chapter, the responses of “very confident” and “confident” were combined when discussing the percentage of students who reported feeling confident in performing certain actions.

← 5. Countries and economies were given equal weight in the standardisation procedure.