This chapter explores whether students practice basic behaviours and attitudes towards money that demonstrate responsibility in their spending and saving decisions. It also examines the role of friends in influencing students’ financial attitudes and behaviours. It discusses whether such behaviours and attitudes are related to performance in the financial literacy assessment.

PISA 2022 Results (Volume IV)

8. Students’ spending and saving behaviours and attitudes

Abstract

Research has shown that financial literacy is positively associated with better financial outcomes, in terms of spending, investment and debt (Deuflhard, Georgarakos and Inderst, 2019[1]; Schützeichel, 2019[2]; Lusardi and Tufano, 2015[3]; Mitchell and Lusardi, 2015[4]; Lusardi and Streeter, 2023[5]). However, the existing literature has mostly examined financial outcomes amongst adults, and outcomes among 15-year-old students have only been studied to some extent in previous PISA assessments (OECD, 2014[6]; 2017[7]). Although 15-year-olds have only limited agency in their financial decisions – they are often legally restricted in signing their own sales contracts – there are still basic financial behaviours that they engage in on a regular basis, such as making small purchases or starting to save some money. These behaviours and actions might reflect how responsible they are with their money and finances, and whether they will be ready to make more formal financial decisions in only a few years’ time.

The PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment offers the opportunity to analyse students’ spending and saving behaviour in a deeper way than was done in previous assessments. The 2022 financial literacy questionnaire collected information on a wider range of aspects related to students spending and saving behaviour, and collected more information on attitudes related to such behaviours than in the past. Moreover, it also investigated the role of friends in influencing students’ spending decisions, as prior research suggest friends can influence teenagers’ risky and financial behaviours (Sasmito et al., 2023[8]; McMillan, Felmlee and Osgood, 2018[9]; Mangleburg, Doney and Bristol, 2004[10]) as well as adults’ financial behaviours (Shabbir Rana, 2022[11]).

This chapter examines students’ spending behaviours and attitudes, and whether such behaviours and attitudes are associated with financial literacy performance. It explores the influence of friends on students’ attitudes and behaviours related to financial matters. The chapter also examines 15-year-old students’ behaviours and attitudes towards saving and the long-term, and how they are related to financial literacy.

What the data tell us

More than two in three students, on average across OECD countries and economies, reported that they sometimes or always compare prices in different shops (74%) or between a physical and an online shop (68%), when thinking about buying something using their allowance. Some 77% of students, on average across OECD countries and economies, reported that they had bought something that cost more money than they had intended to spend.

Students who performed at Level 4 or 5 in financial literacy were almost 3 times as likely to report that they compare prices in different shops, and almost twice as likely to report that they compare prices between a physical shop and an online shop, as those who scored at Level 1 or below, on average across OECD countries and economies, and after accounting for student characteristics and spending attitudes.

On average across OECD and all participating countries and economies, 60% of students reported having bought something because their friends had it, over the 12 months prior to the survey. Students who performed at Level 4 or 5 in financial literacy were 54% less likely than those scoring at Level 1 or below to report buying something because their friends had it, after accounting for student characteristics and attitudes, on average across OECD countries and economies.

Some 93% of students, on average across OECD countries and economies, reported that they had saved money at least once a year in the 12 months before the survey, with 67% of students reporting that they had saved into an account and 88% of students reporting that they had saved at home.

Students who performed at Level 4 or 5 in financial literacy were more than twice as likely as those performing at Level 1 or below to report having saved into an account or at home in the 12 months prior to the survey, after accounting for student characteristics, bank account holding and attitudes towards saving, on average across OECD countries and economies.

Students’ spending behaviours, strategies and attitudes

The PISA 2022 financial literacy questionnaire examines students’ behaviour and attitudes towards spending.

Students’ spending behaviours

To assess how students behave towards spending, whether they keep track of their expenses and are in control of their finances, the PISA 2022 financial literacy questionnaire asked students whether they had, in the previous 12 months:

checked how much money they had

checked that they were given the right change when they bought something with cash

complained that they did not have enough money for something they wanted to buy

bought something that cost more money than they intended to spend.

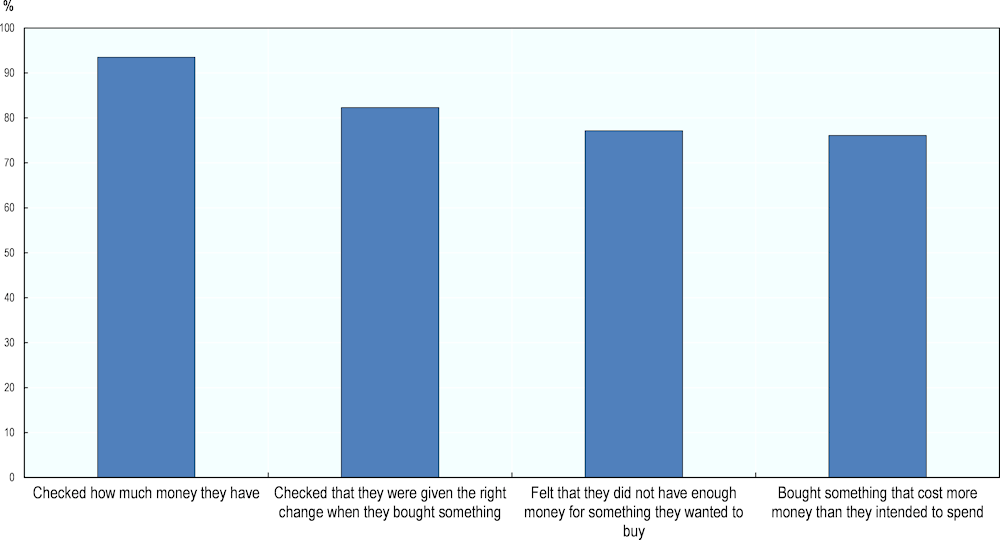

On average across OECD countries and economies, 94% of students reported that they had checked how much money they have, 82% of students reported that they had checked that they were given the right change, 77% had bought something that cost more money than they intended to spend, and 76% complained that they did not have enough money for something they wanted to buy in the 12 months prior to the survey. These behaviours were commonplace amongst students in all the countries and economies that participated in the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment (Figure IV.8.1 and Table IV.B1.8.1).

Some 96% of students in Denmark*, Hungary and the Netherlands*, 95% of students in Norway and 94% of students in Austria, Czechia, Poland and the United States* had checked how much money they have in the 12 months prior to the survey, while even in the countries and economies where this behaviour was least common – Brazil, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates – over 84% of students had checked how much money they have (Figure IV.8.1 and Table IV.B1.8.1).

Likewise, over 91% of students in Portugal reported that they had checked that they were given the right change when they bought something in the 12 months prior to the survey. In Austria, where this behaviour was least common, around three in four students (75%) had checked that they were given the right change, as did 84% of students in Poland and the United Arab Emirates, and 87% of students in Italy (Figure IV.8.1 and Table IV.B1.8.1).

Some 85% of students in Poland reported that, over the previous 12 months, they had complained that they did not have enough money for something they wanted to buy, as did 83% of students in Costa Rica, Peru and the United States*. In Portugal, where this behaviour was least common, 63% of students reported having felt they lacked money to buy something (Figure IV.8.1 and Table IV.B1.8.1).

On average across all participating countries and economies, 74% of students reported that they had bought something that cost more money than they intended to spend at some point in the 12 months prior to the survey. More than 80% students in Norway and Poland (84%), Bulgaria (82%), Czechia and Denmark* (81%) and the Netherlands* (80%) reported doing so. The smallest proportions of students who reported doing so were observed in Saudi Arabia (57%) and Peru (58%), where more than one in two students still reported they had spent more money than intended in the previous 12 months (Figure IV.8.1 and Table IV.B1.8.1).

Figure IV.8.1. Students’ spending behaviour

Percentage of students who reported that they sometimes or always display the following spending behaviours; OECD average

Behaviours are ranked in descending order of the percentage of students who reported displaying them.

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 Database, Table IV.B1.8.1.

On average across OECD countries and economies, slightly more girls than boys reported having experienced each of the four spending behaviours in the 12 months prior to the survey:

Four percentage points more girls than boys reported having complained that they did not have enough money for something they wanted to buy. This gap narrowed to 2 percentage points on average across all participating countries and economies, and was largest in Denmark* (10 percentage points), the Flemish community of Belgium (8 percentage points), the Netherlands* (6 percentage points), Costa Rica and Czechia (5 percentage points). However, in Hungary, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, more boys than girls reported such behaviour, by between 3 and 6 percentage points (Table IV.B1.8.2).

Three percentage points more girls than boys reported having bought something that cost more than they intended to spend. This difference was significant and positive in favour of girls in nine participating countries, but the reverse was true in three countries and economies, particularly in Saudi Arabia where 23 percentage points more boys than girls reported such behaviour (Table IV.B1.8.2).

Two percentage points more girls than boys reported having checked that they were given the right change when buying something, and having checked how much money they have. In no country or economy were any of these behaviours more common amongst boys than girls (Table IV.B1.8.2).

On average across OECD countries and economies and all participating countries and economies, more students from advantaged backgrounds1 than disadvantaged students reported two behaviours associated with keeping track of one’s finances, such as checking that they were given the right change and checking how much money they have. In particular:

More students from advantaged backgrounds than disadvantaged students reported having checked they were given the right change when purchasing something, by 5 percentage points on average across OECD countries and economies, and by 8 percentage points on average across all participating countries and economies. This association was positive and significant in 17 countries and economies, and the gap reached 19 percentage points in Peru. However, disadvantaged students reported 5 percentage points more often than advantaged ones having experienced such behaviour in Norway (Table IV.B1.8.3).

More students from advantaged backgrounds than disadvantaged students reported having checked how much money they have, by 4 percentage points on average across OECD countries and economies, and by 7 percentage points on average across all participating countries and economies. The difference was significant in 18 countries and was highest in Peru (17 percentage points) and Brazil (15 percentage points) (Table IV.B1.8.3).

Moreover, on average across OECD countries and economies and all participating countries and economies, more students from advantaged backgrounds reported two other behaviours, having bought something that cost more money than they intended to spend and (not) complaining that they did not have enough money for something they wanted to buy, that may be the reflection of the greater availability of financial resources in their family compared to disadvantaged students. In particular:

More students from advantaged backgrounds than disadvantaged students reported having bought something that cost more money than they intended to spend, by 1 percentage point on average across OECD countries and economies, and by 6 percentage points on average across all participating countries and economies. This difference was positive in 11 countries and economies and reached 34 percentage points in Peru and 19 percentage points in Brazil. However, more disadvantaged students reported such behaviour in Hungary, by 8 percentage points, and in Austria, by 4 percentage points (Table IV.B1.8.3).

More students from disadvantaged backgrounds than advantaged students reported having complained that they did not have enough money for something they wanted to buy, by 4 percentage point on average across OECD countries and economies, and by 2 percentage points on average across all participating countries and economies. However, the direction of this difference was not consistent across countries and economies. In Austria, Denmark*, the Netherlands* and Norway, fewer advantaged students than disadvantaged students (by between 6 and 11 percentage points) reported having complained, while in Brazil, Malaysia and Peru, more advantaged students than disadvantaged ones (by between 6 and 9 percentage points) reported having complained (Table IV.B1.8.3).

Results for immigrant and non-immigrant students are available in Annex B.

Students’ spending strategies

In addition to questions about how they manage their money when making purchases, students who sat the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment were asked about their strategies when they think about buying a new product from their allowance. More specifically, students were asked whether they always, sometimes, rarely or never:

compare prices in different shops

compare prices between a shop and an online shop

buy the product without comparing prices

wait until the product becomes cheaper before buying it.

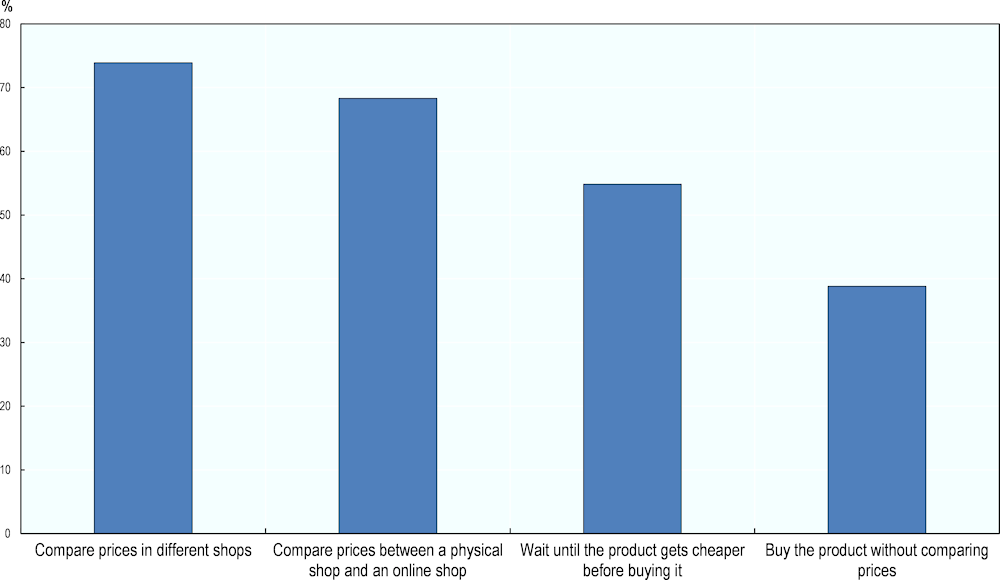

The most commonly used strategy was comparing prices in different shops. On average across OECD countries and economies, 74% of students reported always or sometimes2 comparing prices in different shops. Some 80% of students in Denmark* and Portugal reported comparing prices in different shops, but two out of three or fewer students in Saudi Arabia (60%), Bulgaria (61%), and Austria (66%) reported doing so (Figure IV.8.2 and Table IV.B1.8.5).

Some 68% of students on average across OECD countries and economies reported comparing prices between a physical shop and an online shop. This strategy was used by at least three in four students in the Canadian provinces* and the United States* (76%), Italy and the United Arab Emirates (75%). However, just over one in two students in Peru reported that they compare prices between a physical shop and an online shop (53%), as did only 55% of students in Costa Rica. (Figure IV.8.2 and Table IV.B1.8.5).

Figure IV.8.2. Students’ spending strategies

Percentage of students who reported that they sometimes or always use each spending strategy; OECD average

Strategies are ranked in descending order of the percentage of students who reported using them.

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 Database, Table IV.B1.8.5.

Some 55% of students, on average across OECD countries and economies, reported that they wait until the product becomes cheaper before buying it. Two out of three students or more in the Canadian provinces* (67%) and Portugal (70%) reported using this strategy. By contrast, fewer than one in two students reported so in Czechia (40%), Costa Rica (42%) and Hungary (45%) (Figure IV.8.2 and Table IV.B1.8.5).

The least prudent spending strategy – buying the product without comparing prices – was also the least commonly reported. Only 39% of students, on average across OECD as well as all participating countries and economies, reported doing this. Buying a product without comparing prices was relatively less common amongst students in Costa Rica (28%), Peru and Portugal (31%), Czechia, Hungary and Italy (all 32%). However, 52% of students in Norway reported following this strategy (Figure IV.8.2 and Table IV.B1.8.5).

On average across OECD countries and economies, more girls than boys reported that they compare prices in different shops (by 4 percentage points), and this gender gap was significant in 11 countries and economies (Table IV.B1.8.6). However, more girls than boys also reported that they buy the product without comparing prices (by 3 percentage points), on average across OECD countries and economies. This apparent inconsistency is related to some extent to different gender patterns across countries and economies. For instance, in the Flemish community of Belgium, Brazil, Costa Rica, Italy, Malaysia, Poland, Portugal and Spain, more girls than boys reported comparing prices in different shops, and more boys than girls (or boys and girls in the same proportion) reported buying the product without comparing prices. On the contrary, in Denmark* more girls than boys reported buying the product without comparing prices (by 11 percentage points), with no gender difference in the percentage of boys and girls who reported comparing prices in different shops (Table IV.B1.8.6). Gender differences in the two other spending strategies were small and different across countries and economies.

More students from advantaged families than disadvantaged students reported comparing prices, either between physical shops or with an online shop. Ten percentage points more advantaged students than disadvantaged students reported comparing prices in different shops, on average across OECD countries and economies. The gap between the two groups of students was particularly large in Malaysia (22 percentage points), Bulgaria and Peru (20 percentage points), and was significant in all countries and economies with valid data. Likewise, 8 percentage points more advantaged students than disadvantaged students reported comparing prices between a physical shop and an online shop, on average across OECD countries and economies. This gap was particularly pronounced in Peru (36 percentage points), Brazil (24 percentage points) and Malaysia (21 percentage points) but was not significant in the Flemish community of Belgium nor in the Netherlands* (Table IV.B1.8.7).

More advantaged students than disadvantaged students also reported waiting for a product to become cheaper before buying it. The gap amounted to 3 percentage points, on average across OECD countries and economies, and was between around 13 percentage points in Brazil and Malaysia. However, it was not significant in nine countries and economies. On average across OECD countries and economies, 2 percentage points more disadvantaged students reported buying a product without comparing prices, although at the country level, the difference related to socio-economic status was observed only amongst students in Bulgaria, Czechia, Hungary and Poland (Table IV.B1.8.7).

These results indicate that advantaged students, in general, tend to use responsible spending strategies more than disadvantaged students. This may be partly due to different levels of awareness about such strategies between advantaged and disadvantaged students; it may also be due, in part, to advantaged students having more opportunities to apply responsible spending strategies. For example, advantaged students may have more opportunities to be digitally connected and access online shops; they also may not be in immediate need of certain items and thus can wait until such items become cheaper before purchasing them. No matter the reason, the greater use of responsible spending strategies by advantaged students may lead to further inequalities in financial outcomes later in life.

Results for immigrant and non-immigrant students are available in Annex B.

Students’ spending attitudes

In addition to their financial behaviour and spending strategies, students who sat the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment were asked about some of their attitudes to spending. More specifically, they were asked whether they felt not at all confident, not very confident, confident or very confident:

understanding a sales contract

planning [their] spending with consideration of [their] current financial situation.

Students were also asked whether they strongly disagreed, disagreed, agreed or strongly agreed that:

[they] buy things according to how [they] feel in the moment

it is easier to monitor [their] spending when paying by cash than with a bank card.

On average across OECD countries and economies, only 34% of students reported that they feel confident in understanding a sales contract. Just under half of students in Austria (49%) reported that they feel confident in this task, but only 22% of students in Malaysia reported the same (Table IV.B1.8.9).

On average across OECD countries and economies, most students reported that they were confident in planning their spending in consideration of their current financial situation (62%). Across all participating countries and economies, 60% of students were confident in this task, from 75% of students in the Netherlands*, to 50% of those in Malaysia (Table IV.B1.8.9). About half of students agreed or strongly agreed that they tend to buy things according to how they feel in the moment, on average across OECD and all participating countries (49% and 51% respectively). This attitude to spending was reported by 65% of students in Malaysia, compared to 37% of students in Hungary (Table IV.B1.8.9).

Over half of students agreed or strongly agreed that it is easier to monitor spending when paying with cash than with a bank card. On average across OECD countries and economies, 54% of students reported this attitude, compared to 58% on average across all participating countries and economies. This attitude towards paying by cash was exhibited by between 66% and 71% of students in Costa Rica, Malaysia, Portugal, Saudi Arabia, Spain and the United Arab Emirates, but only by 32% of those in Denmark* (Table IV.B1.8.9).

Fewer girls than boys reported feeling confident understanding a sales contract (by 19 percentage points) and planning their spending in consideration of their current financial situation (by 8 percentage points), on average across OECD countries and economies. The gender gap in confidence understanding a sales contract was significant in all participating countries and economies, while the gap in confidence planning was significant in 16 of the 20 participating countries and economies (Table IV.B1.8.10).

More boys than girls reported finding it easier to monitor spending when paying by cash on average across OECD countries and economies (by 2 percentage points), but the gender gap was significant and in favour of boys in only eight countries and economies, while it was in favour of girls in another five countries and economies, and not significant in the remaining seven countries and economies (Table IV.B1.8.10). Slightly more girls than boys (by 1 percentage point) agreed that they buy things according to how they feel in the moment, on average across OECD countries and economies, but this difference was modest and observed only in three countries and economies (Hungary, Italy and Poland), and in Norway, more boys than girls reported this spending attitude (by 5 percentage points) (Table IV.B1.8.10).

More advantaged students reported feeling confident planning their spending based on their current financial situation on average across OECD countries and economies, by 10 percentage points. This attitude was observed in 16 participating countries and economies, and in no country or economy did more disadvantaged students report feeling confident planning their spending in consideration of their current financial situation. On average across all participating countries and economies, 3 percentage points more advantaged students than disadvantaged students reported feeling confident understanding a sales contract, although there was no clear pattern across OECD countries and economies (Table IV.B1.8.11).

On average across OECD countries and economies, more disadvantaged students than advantaged students reported buying things according to how they feel in the moment, by 5 percentage points. This was the case in Austria, the Flemish community of Belgium, Hungary, Portugal and the United States*, but more advantaged students reported such attitude in Peru (by 6 percentage points). Likewise, on average across OECD countries and economies, 4 percentage points more disadvantaged students than students from advantaged backgrounds agreed that monitoring one’s spending is easier when paying by cash. However, this difference varied widely across countries and more advantaged students were reported such attitude in seven participating countries and economies (Table IV.B1.8.11).

Results for immigrant and non-immigrant students are available in Annex B.

Performance in the financial literacy assessment and students’ spending attitudes

Students’ attitudes towards spending were also associated with their performance in financial literacy. Students who reported that they were confident in planning their spending in consideration of their financial situation scored higher in financial literacy than students who did not feel confident by 28 score points, after accounting for student characteristics, on average across OECD countries and economies. This positive association was observed in all countries and economies with valid data (Table IV.B1.8.13).

By contrast, students who reported feeling confident understanding a sales contract performed 13 score points lower in financial literacy than those who did not report so, on average across OECD countries and economies and after accounting for student characteristics. This negative association was observed in 11 countries and economies, and students in the United States* who were confident understanding a sales contract scored 37 points lower on average than those who were not. In Czechia and Peru however, students who felt confident understanding a sales contract performed better than those who did not, by 8 and 20 score points respectively (Table IV.B1.8.13). Further research may be needed to uncover any characteristics of students who are confronted with sales contracts and feel confident in understanding them, to explain their lower financial literacy levels.

As can be expected, students who agreed that they buy things according to how they feel in the moment scored lower in financial literacy than those who disagreed (by 24 points on average across OECD countries and economies, after accounting for student characteristics) (Table IV.B1.8.13). This was true in 16 countries and economies, and the difference in financial literacy associated with this spending attitude was not significant in the remaining countries and economies.

On average across OECD countries and economies, students who find it easier to monitor their spending when paying by cash than with a bank card performed 21 score points lower in financial literacy than those who did not, after accounting for student characteristics. However this was not consistent across countries, as this negative relationship was observed in nine countries and economies (the Flemish community of Belgium, Brazil, the Canadian provinces*, Czechia, Denmark*, Hungary, the Netherlands*, Norway and the United States*) and the difference reached 60 score points in the Netherlands*, but the difference in performance was in favour of students who agreed that it is easier to monitor their spending when paying by cash in Malaysia, Peru and Spain, by between 7 and 21 score points (Table IV.B1.8.13).

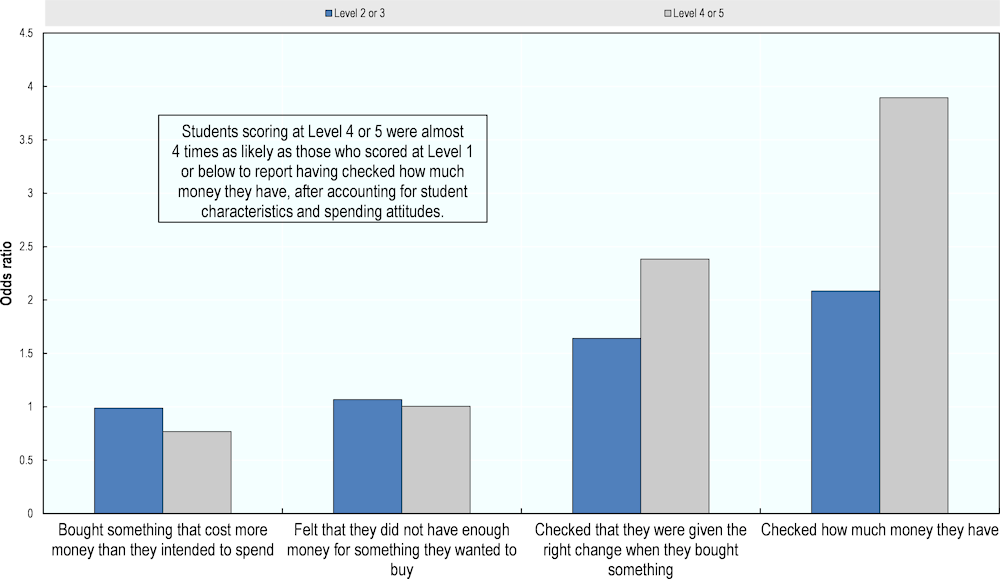

Performance in the financial literacy assessment and students’ spending behaviour and strategies

Responsible financial behaviours are positively associated with financial literacy. On average across OECD countries and economies, students scoring at Level 4 or 5 in the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment were almost 4 times as likely as those who scored at Level 1 or below to report having checked how much money they have in the 12 months prior to the survey, after accounting for student characteristics, such as gender, socio-economic status, immigrant background and attitudes towards spending.3 This increased likelihood was significant in 15 countries and economies that participated in the assessment (Figure IV.8.3 and Table IV.B1.8.14).

Likewise, students who scored at Level 4 or 5 in financial literacy were more than twice as likely as those scoring at Level 1 or below to report having checked that they were given the right change after buying something, in the previous 12 months, on average across OECD countries and economies, after accounting for student characteristics and spending attitudes, and 3 times more so on average across all participating countries and economies. This increased likelihood was significant in 15 countries and economies (Figure IV.8.3 and Table IV.B1.8.14).

Checking how much money students have or checking that they were given the right change after buying something, were positively associated with financial literacy performance even after accounting for students’ mathematics and reading performance (in addition to students’ characteristics and spending attitudes). On average across OECD countries and economies, after accounting for their characteristics and performance in mathematics and reading, students who scored at Level 4 or 5 in financial literacy were 83% more likely to check how much money they had, and 31% more likely to check that they were given the right change after buying something than students scoring at Level 1 or below (Table IV.B1.8.14).

Students who scored at Level 4 or 5 in financial literacy were 23% less likely than those scoring at Level 1 or below to report having bought something that cost more money than they had intended to spend in the previous 12 months, on average across OECD countries and economies and after accounting for student characteristics and spending attitudes. This negative relationship was particularly large in Saudi Arabia (58% less likely) and Austria (54% less likely) but was not significant in 14 countries and economies. High-performing students in financial literacy in Peru were 48% more likely than low-performing ones to report such behaviour, after accounting for student characteristics and spending attitudes. On average across all participating countries and economies, students performing at Level 4 or 5 in financial literacy were equally likely than those performing at Level 1 or below to complain about not having enough money for something they wanted to buy, after accounting for student characteristics and spending attitudes. This relationship was inconsistent across countries and economies, and not significant in most participating countries and economies (Figure IV.8.3 and Table IV.B1.8.14).

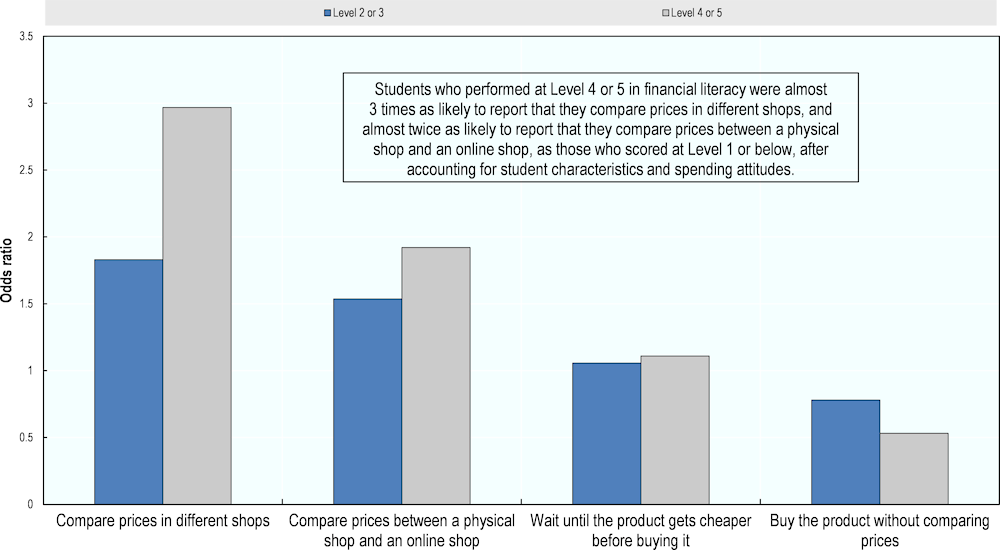

As was the case with students’ financial behaviours, using responsible spending strategies was positively associated with financial literacy performance. After accounting for student characteristics, such as gender, socio-economic status, immigrant background and for their spending attitudes, students who performed at Level 4 or 5 in financial literacy were almost 3 times as likely as students performing at Level 1 or below to report that they compare prices in different shops when thinking about buying a product with their allowance, on average across OECD countries and economies. This positive association was observed in all countries and economies that participated in the assessment and had valid data, and the size of the likelihood increase ranged from 79% in the Canadian provinces* to almost 5 times as likely in Malaysia (Figure IV.8.4 and Table IV.B1.8.15).

Figure IV.8.3. Students’ spending behaviour, by performance in financial literacy

Increased likelihood of students at each proficiency level, compared with students at or below Level 1, to report that they have done the following at least once a year in the past 12 months instead of reporting that they did not do it, after accounting for student characteristics and spending attitudes; OECD average

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 Database, Table IV.B1.8.14.

Likewise, students who performed at Level 4 or 5 in the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment were almost twice as likely as those performing at Level 1 or below to report that they compare prices between a physical shop and an online shop, on average across OECD countries and economies and after accounting for student characteristics and spending attitudes, and more than twice as likely on average across all countries and economies. The likelihood increase was significant in 15 countries and economies (Figure IV.8.4 and Table IV.B1.8.15).

Comparing prices in different shops and comparing prices between a physical and an online shop, were positively associated with financial literacy performance even after accounting for students’ mathematics and reading performance (in addition to students’ characteristics and spending attitudes). On average across OECD countries and economies, after accounting for their characteristics and performance in mathematics and reading, students who scored at Level 4 or 5 in financial literacy were 50% more likely to compare prices in different shops, and 43% more likely to compare prices between a physical shop and an online shop than students scoring at Level 1 or below (Table IV.B1.8.15).

Students who performed at Level 4 or 5 in the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment were 11% more likely than those performing at Level 1 or below to report that they wait until a product becomes cheaper before buying it, on average across OECD countries and economies and after accounting for student characteristics and spending attitudes, and 20% more likely on average across all countries and economies (Figure IV.8.4 and Table IV.B1.8.15).

Higher performance in financial literacy was negatively associated with buying a product without comparing prices. Students who scored at Level 4 or 5 in financial literacy were almost 50% less likely than those scoring at Level 1 or below to report that they buy a product without comparing prices, on average across both OECD and all participating countries and economies, after accounting for student characteristics and spending attitudes. The decline in likelihood associated with not comparing prices was significant in all participating countries and economies except Austria, the Flemish community of Belgium and the United States* (Figure IV.8.4 and Table IV.B1.8.15).

Figure IV.8.4. Students’ spending strategies, by performance in financial literacy

Increased likelihood of students at each proficiency level, compared with students at or below Level 1, to report that they adopted the following spending strategy in the past 12 months instead of reporting that they did not adopt it, after accounting for student characteristics and spending attitudes; OECD average

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 Database, Table IV.B1.8.15.

Spending behaviours and attitudes: the influence of friends

Given the particular importance of social interactions for 15-year-old students, the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment introduced new questions to assess the potential influence of friends on students’ spending behaviour and attitudes.

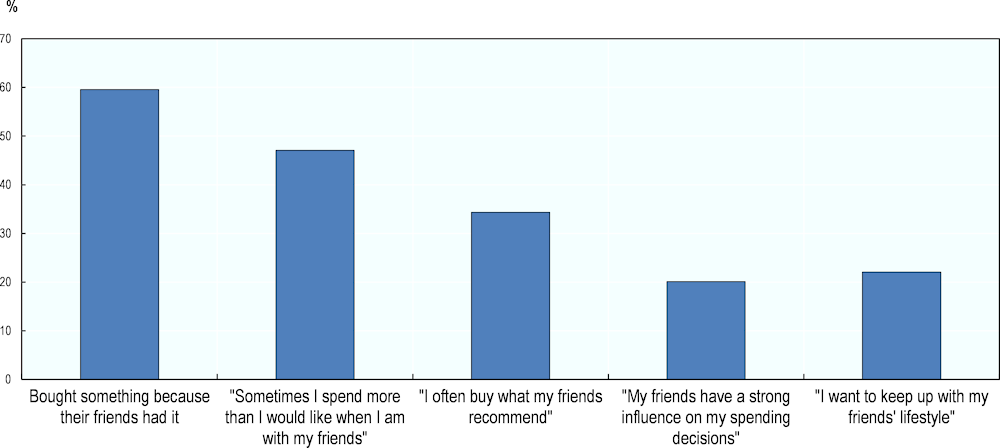

On average across both OECD and all participating countries and economies, 60% of students reported having bought something because their friends had it, over the 12 months prior to the survey. Some 69% of students in Bulgaria and Norway reported having done so, compared to only 36% of students in Costa Rica (Figure IV.8.5 and Table IV.B1.8.16).

Students were also asked whether they strongly disagreed, disagreed, agreed or strongly agreed with the following attitude statements:

[their] friends have a strong influence on [their] spending decisions

[they] want to keep up with [their] friends’ lifestyle

Sometimes [they] spend more than [they] would like when [they are] with friends

[they] often buy what [their] friends recommend.

Just under half (47%) of students reported that they sometimes spend more than they would like when they are with their friends, on average across OECD countries and economies. This ranged from 40% of students in Austria and Peru to 58% of those in Bulgaria (Figure IV.8.5 and Table IV.B1.8.16). About a third (34%) of students reported that they often buy what their friends recommend, on average across OECD countries and economies. Around half of students agreed with this statement in Saudi Arabia (51%) and the United Arab Emirates (48%), but less than one‑in‑five did in Peru (19%) (Figure IV.8.5 and Table IV.B1.8.16).

Figure IV.8.5. The influence of friends on students’ spending behaviour and attitudes

Percentage of students who reported that they agree with the following statements; OECD average

Statements are ranked in descending order of the percentage of students who reported agreeing with them.

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 Database, Table IV.B1.8.16.

On average across OECD countries and economies, about one in five students agreed that their friends have a strong influence on their spending decisions (20%) and that they want to keep up with their friends’ lifestyle (22%). Students in partner countries more frequently agreed with these statements, as the average across all participating countries and economies was 3 percentage points higher for both statements. More than a third of students in Malaysia, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates agreed that their friends have a strong influence on their spending decisions, and between 37% and 40% of students in Bulgaria, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates reported that they wanted to keep up with their friends’ lifestyle (Figure IV.8.5 and Table IV.B1.8.16).

More boys than girls generally reported being influenced by their friends with respect to their spending attitudes and behaviours, even if gender differences were generally small. In no country did more girls than boys report having bought something because their friends had it, or wanting to keep up with their friends’ lifestyle, or that their friends had a strong influence on their spending decisions (Table IV.B1.8.17):

Eight percentage points more boys than girls reported they had bought something because their friends had it, on average across OECD countries and economies. This gender gap was observed in all participating countries and economies, except in Czechia and Poland where the difference was not significant. The gap ranged from 6 percentage points in Austria, the Flemish community of Belgium and Bulgaria to 20 percentage points in Saudi Arabia.

Four percentage points more boys than girls reported wanting to keep up with their friends’ lifestyle on average across OECD countries and economies. In 16 of the 20 participating countries and economies was this difference significant. In Saudi Arabia, 17 percentage points more boys than girls reported wanting to keep up with their friends’ lifestyle, compared to only 3 percentage points in the Netherlands*.

Four percentage points more boys than girls also reported that their friends have a strong influence on their spending decisions on average across OECD countries and economies. This gender difference was significant in 15 countries and economies, and was highest in Saudi Arabia (15 percentage points).

More boys than girls reported that they often buy what their friends recommend (by 4 percentage points on average across OECD countries and economies). This difference was significant in 13 of the participating countries and economies. In Brazil, Costa Rica and Saudi Arabia, 10 percentage points more boys than girls reported such influence of friends on their spending attitude.

By contrast, more girls than boys – by 3 percentage points on average across OECD countries and economies –reported sometimes spending more than they would when they are with friends. Across all participating countries and economies, this difference narrows to 1 percentage point on average, and is only significant in seven countries and economies: the Flemish community of Belgium, Czechia, Denmark*, Hungary, Norway, Poland and Spain. More boys than girls reported overspending when with friends in Austria, Peru, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (Table IV.B1.8.17).

On average across OECD countries and economies, slightly more advantaged students than disadvantaged students reported being influenced by their friends in their spending behaviours and attitudes (Table IV.B1.8.18).

Some 2 percentage points more advantaged students reported having bought something because their friends had it. This varied greatly by country and economy, as 17 percentage points more advantaged students in Peru, and 16 percentage points in the United States* reported so, but in Austria, Bulgaria and Hungary, between 4 and 12 percentage points more disadvantaged students than students from advantaged backgrounds reported having bought something because their friends had it.

Around 2 percentage points more advantaged students also reported sometimes spending more than intended when with friends, on average across OECD countries and economies. This was particularly the case in Brazil (14 percentage points) and Peru (13 percentage points). However, the reverse was true in Austria and Hungary.

Two percentage points more students coming from an advantaged background than disadvantaged students reported often buying what their friends recommend, on average across OECD countries and economies. This difference was 11 percentage points in the United States*, and 9 percentage points in Saudi Arabia. But 10 percentage points more disadvantaged students agreed with this statement in Bulgaria, as did 7 percentage points more disadvantaged students in Hungary.

There was no clear association between socio-economic status and the influence of friends on spending attitudes measured by the other statements. Full details can be found in Annex B.

Results for immigrant and non-immigrant students are available in Annex B.

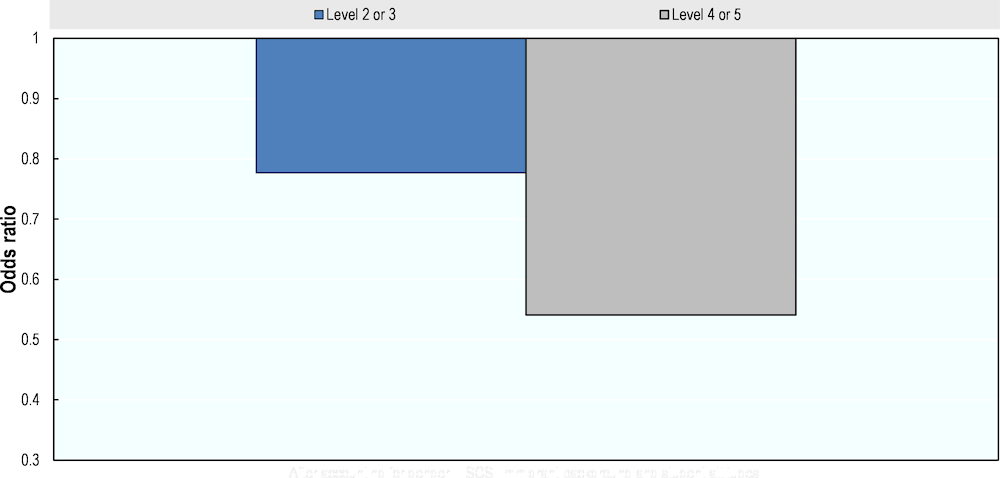

Performance in the financial literacy assessment and the role of friends

Financial literacy appeared to have a potentially moderating effect on friends’ influence on spending behaviour. On average across OECD countries and economies, fifteen-year-old students who performed at Level 4 or 5 in financial literacy were almost 50% less likely than those scoring at Level 1 or below to report buying something because their friends had it, after accounting for student characteristics such as gender, socio-economic status, immigrant background and attitudes about their relationship with friends.4 This decline in likelihood was significant in 17 countries and economies. After accounting for students’ performance in mathematics and reading, the difference was no longer significant in any of the countries and economies (Figure IV.8.6 and Table IV.B1.8.20).

Figure IV.8.6. Buying something because friends have it, by performance in financial literacy

Decrease in likelihood of students at each proficiency level, compared with students at or below Level 1, to report that they bought something because their friends had it instead of reporting that they did not, after accounting for student characteristics and spending attitudes; OECD average after accounting for gender, ESEC, immigrant background and student attitudes

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 Database, Table IV.B1.8.20.

The influence of friends on students’ spending attitudes and behaviours is negatively associated with financial literacy performance. In all participating countries and economies, fifteen-year-old students who reported being influenced by their friends when making financial decisions performed worse than those who did not report such influence, after accounting for student characteristics such as gender, socio-economic status and immigrant background (Table IV.B1.8.21):

On average across OECD countries and economies, students who reported that their friends had a strong influence on their spending decisions scored 30 points lower than those who did not, after accounting for student characteristics. This trend was observed in all participating countries and economies. Students who agreed with this statement in Brazil scored 55 points lower on average than those who disagreed. The performance gap was 20 score points or less in Czechia, Denmark*, Poland and Saudi Arabia.

Similarly, students who reported that they wanted to keep up with their friends’ lifestyle scored 27 points lower than those who disagreed with this statement, on average across OECD countries and economies, after accounting for student characteristics. This performance gap was significant in all participating countries and economies with valid data, and reached 62 points in the Netherlands* and 40 points in Brazil and the United Arab Emirates.

On average across OECD countries and economies, students who reported buying something because their friends had it scored 27 score points lower than those who did not report such influence, after accounting for student characteristics. The performance gap was observed in all countries with valid data, except in Peru where it was not significant. The gap was highest in Bulgaria (36 points) and Austria (34 points), and lowest in Malaysia (9 points).

Students who agreed that they often buy what their friends recommend scored 17 points lower than their peers who disagreed, after accounting for student characteristics, on average across OECD countries and economies. Only in the United States* was this performance gap not significant. The gap was widest in Bulgaria (32 points) and lowest in Austria (9 points).

Students’ saving behaviours and attitudes

As a complement to their spending behaviour and attitudes, the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment also asked students questions about their behaviour and attitudes towards saving and long-term planning.

Students’ saving behaviours

Students were asked how often (never or almost never, about once or twice a year, about once or twice a month, about once or twice a week, every day or almost every day), they had saved in the 12 months prior to the survey, including whether they (Figure IV.8.7 and Table IV.B1.8.22):

saved money into an account at a bank/online bank/building society/post office/credit union

saved money at home.

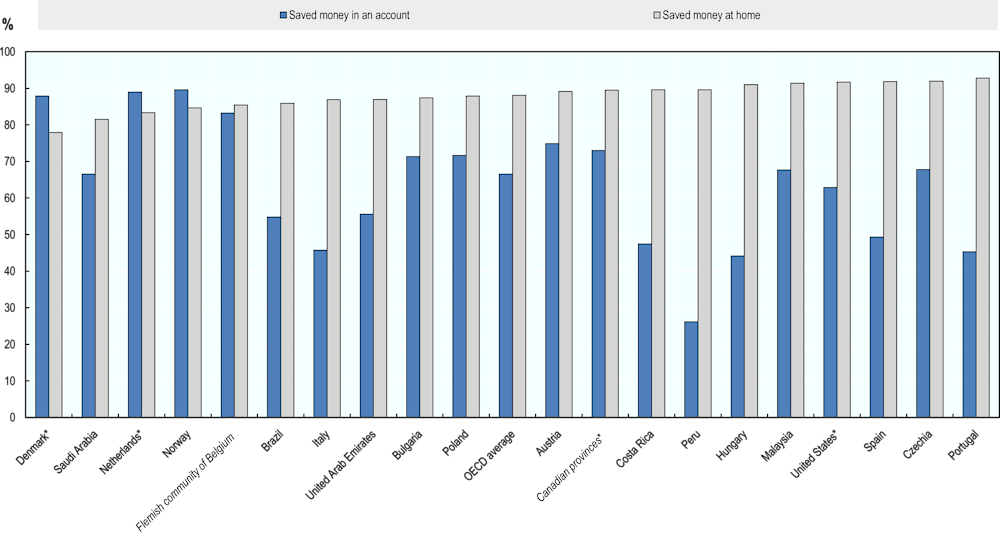

Some 93% of students, on average across OECD countries and economies, reported that they had saved at least once a year in the 12 months before the survey.5 The percentage of students who reported that they had saved ranged between 85% in Saudi Arabia and 95% in Czechia (Table IV.B1.8.22).

On average across OECD countries and economies, 67% of students reported having saved money into an account in the 12 months prior to the survey. There were large differences across participating countries and economies, as more than four in five students in Norway (90%), the Netherlands* (89%), Denmark* (88%) and the Flemish community of Belgium (83%) saved into an account, compared to fewer than one in two students in Peru (26%), Hungary (44%), Portugal (45%), Italy (46%), Costa Rica (47%) and Spain (49%) (Table IV.B1.8.22).

On average across OECD as well as all participating countries and economies, 88% of students reported having saved money at home. This proportion ranged from 78% of students in Denmark* to 93% of students in Portugal (Table IV.B1.8.22). Given that not all students have an account, and the heterogeneity across countries regarding the rules to open an account at the age of 15 (see Box IV.7.1 for further detail), it is unsurprising that more students declared having saved money at home than into an account in the 12 months prior to the survey.

Most students who reported saving, did so both into an account and at home. On average across OECD countries and economies, 61% of students reported saving both into an account and at home, 27% reported saving only at home, and only 5% reported saving only into an account. More than 40% of students Costa Rica, Hungary, Italy, Portugal and Spain reported saving money only at home, as did about two thirds of students in Peru (65%) (Table IV.B1.8.23).

Seven percentage points more boys than girls, on average across OECD countries and economies, reported having saved into an account over the 12 months prior to the survey. This gender gap was significant in 16 of the 20 participating countries and economies, and was largest in Hungary (20 percentage points), Saudi Arabia (17 percentage points), Peru (16 percentage points) and the United Arab Emirates (15 percentage points). In no country or economy did more girls than boys report having saved into an account (Table IV.B1.8.24).

By contrast, slightly more girls than boys (by 1 percentage point) reported having saved money at home on average across OECD countries and economies. However, this gender difference in saving behaviour was only observed in five countries and economies, and gender differences were not significant in other countries and economies (Table IV.B1.8.24).

Figure IV.8.7. Students’ saving behaviour

Percentage of students who reported having saved money in the following ways in the past 12 months

Statements are ranked in ascending order of the percentage of students who reported saving money at home.

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 Database, Table IV.B1.8.22.

More students from an advantaged family background reported having saved money into an account (by 8 percentage points) or at home (by 1 percentage point) than disadvantaged students, on average across OECD countries and economies. This trend was observed in most participating countries and economies, and is consistent with the expectation that advantaged students may have more money to save than their disadvantaged peers. However, in Hungary, 14 percentage points more disadvantaged students than those from an advantaged background reported having saved into an account over the 12 months prior to the survey (Table IV.B1.8.25).

Results for immigrant and non-immigrant students are available in Annex B.

Students’ saving attitudes

Students were asked whether they strongly disagreed, disagreed, agreed or strongly agreed with the following attitude statements, aimed at capturing their long-term orientation and attitudes towards saving:

saving is something [they] do only if [they] have money left over

[they are] able to work effectively towards long-term goals

[they] make savings goals for certain things [they] want to buy or to do.

Some 45% of students agreed that saving is something that they do only if they have money left over, on average across OECD countries and economies. This saving attitude differs strongly among countries and economies, as over three in four students (76%) in Malaysia agreed with this statement, compared to fewer than one in three (32%) in Portugal (Table IV.B1.8.22).

Most 15-year-old students taking the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment reported having a long-term attitude to saving (Table IV.B1.8.22):

Some 74% of students on average across OECD countries and economies reported working towards long-term goals. More than four in five students in Costa Rica, Denmark* and Portugal agreed with this statement, as did about two thirds of students in Czechia (65%), Bulgaria (66%), Italy (67%), Hungary, Austria and Poland (68%).

On average across OECD countries and economies, 73% of students reported making savings goals for certain things they want to buy or to do. This proportion ranged from around two in three students in Austria and the Flemish community of Belgium (66%) to 87% of students in Costa Rica.

Gender differences in saving attitudes were generally small or null. Slightly more boys than girls reported that saving is something that they do only if they have money left over and that they work towards long-term goals (each by 3 percentage points), on average across OECD countries and economies. Slightly more girls than boys (by 2 percentage points) reported making saving goals for certain things they want to buy or to do. There was no clear association between any of these three attitudes and gender, as the direction of the gender gap varied across countries and economies (Table IV.B1.8.24).

Advantaged students generally displayed attitudes oriented toward saving and the long-term to a greater extent than disadvantaged students. More advantaged students than disadvantaged students agreed with the statements “I am able to work effectively towards long-term goals” (by 10 percentage points) and “I make savings goals for certain things I want to buy or to do” (by 3 percentage points) on average across OECD countries and economies. However, 8 percentage points more disadvantaged students on average across OECD countries and economies agreed that “saving is something I do only if I have money left over”. This difference in attitude was significant in 11 countries and economies and was highest in the United States* (17 percentage points). In Saudi Arabia though, 7 percentage points more advantaged students reported agreeing that saving is what they do when they have money left over (Table IV.B1.8.25). This might reflect the fact that students from an advantaged family background may be in a position to save money more easily than disadvantaged students.

Results for immigrant and non-immigrant students are available in Annex B.

Long-term orientation and saving attitudes were generally positively correlated with students’ financial literacy (Table IV.B1.8.27):

Students who agreed that they are able to work effectively towards long-term goals scored 22 points higher than those who did not, on average across OECD countries and economies, after accounting for student characteristics. This positive link was observed in all participating countries and economies with valid data.

Students who agreed that they make savings goals for certain things they want to buy or do scored 9 points higher than those who did not, on average across OECD countries and economies, after accounting for student characteristics. This correlation was positive and significant in 14 countries and economies, including in Malaysia and Peru where the score-point difference exceeded 40 points. However, students in Denmark* who reported saving for big purchases scored 11 points lower than those who did not.

Students who agreed that saving is something they do only if they have money left over generally scored lower (on average by 24 score points in OECD countries and economies) than those who disagreed with this statement, after accounting for student characteristics. The correlation was negative and significant in 14 countries and economies and was widest in the United States* (53 points) and the Canadian provinces* (45 points). In Malaysia, students who agreed with this attitude statement scored 17 points higher than those who disagreed.

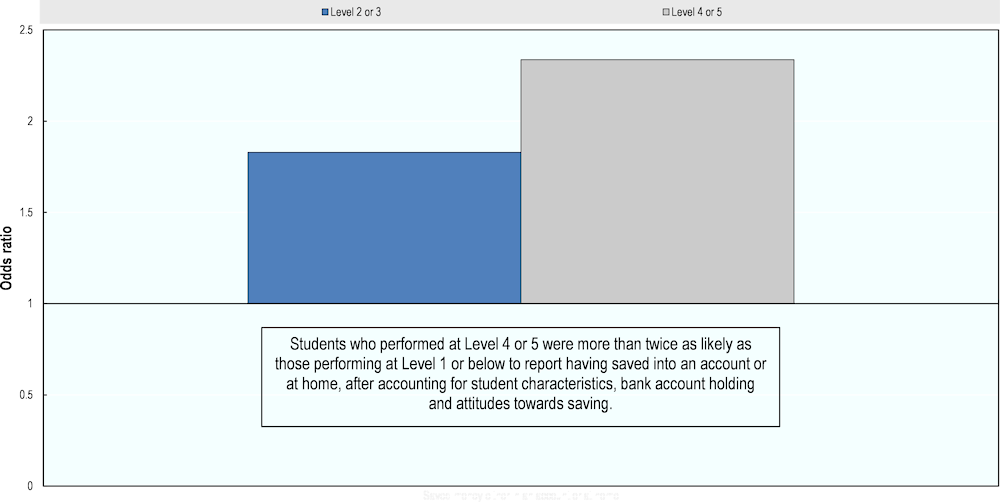

Performance in the financial literacy assessment and saving behaviour

PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment results indicate that saving (whether into an account or at home) was associated with higher performance in financial literacy. On average across OECD countries and economies, students who performed at Level 4 or 5 in financial literacy were more than twice as likely as those performing at Level 1 or below to report having saved into an account or at home in the 12 months prior to the survey, after accounting for student characteristics, such as gender, socio-economic status, immigration background, bank account holding and attitudes towards saving.6 This positive association was significant in 14 countries and economies (Table IV.B1.8.28).

PISA 2022 data indicate that higher performance in financial literacy was associated with saving behaviour (whether into an account or at home) also after accounting for students’ performance in mathematics and reading, i.e. for their overall ability in the main school subjects. On average across OECD countries and economies and across all participating countries and economies, students performing at Level 4 or 5 in financial literacy were 72% more likely than those performing at Level 1 or below to report having saved into an account or at home in the 12 months prior to the assessment, after accounting for student characteristics, bank account holding, attitudes towards saving, and performance in mathematics and reading (Table IV.B1.8.28).

Figure IV.8.8. Students’ saving behaviour, by performance in financial literacy

Increased likelihood of students at each proficiency level, compared with students at or below Level 1, to report having saved in the following way in the past 12 months instead of reporting not having saved in this way, after accounting for student characteristics, bank account holding and attitudes towards saving; OECD average

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 Database, Table IV.B1.8.28.

Table IV.8.1. Students’ spending and saving behaviour and attitudes chapter figures

|

Figure IV.8.1 |

Students’ spending behaviour |

|

Figure IV.8.2 |

Students' spending strategies |

|

Figure IV.8.3 |

Students’ spending behaviour, by performance in financial literacy |

|

Figure IV.8.4 |

Students’ spending strategies, by performance in financial literacy |

|

Figure IV.8.5 |

The influence of friends on students’ spending behaviour and attitudes |

|

Figure IV.8.6 |

Buying something because friends have it, by performance in financial literacy |

|

Figure IV.8.7 |

Students’ saving behaviour |

|

Figure IV.8.8 |

Students’ saving behaviour, by performance in financial literacy |

References

[1] Deuflhard, F., D. Georgarakos and R. Inderst (2019), “Financial literacy and savings account returns”, Journal of the European Economic Association, Vol. 17/1, pp. 131-164, https://doi.org/10.1093/jeea/jvy003.

[5] Lusardi, A. and J. Streeter (2023), “Financial literacy and financial well-being: Evidence from the US”, Journal of Financial Literacy and Wellbeing, Vol. 1/2, pp. 169-198, https://doi.org/10.1017/flw.2023.13.

[3] Lusardi, A. and P. Tufano (2015), “Debt literacy, financial experiences, and overindebtedness”, Journal of Pension Economics and Finance, Vol. 14/4, pp. 332-368, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474747215000232.

[10] Mangleburg, T., P. Doney and T. Bristol (2004), “Shopping with friends and teens’ susceptibility to peer influence”, Journal of Retailing, Vol. 80/2, pp. 101-116, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2004.04.005.

[9] McMillan, C., D. Felmlee and D. Osgood (2018), “Peer influence, friend selection, and gender: How network processes shape adolescent smoking, drinking, and delinquency”, Social Networks, Vol. 55, pp. 86-96, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2018.05.008.

[4] Mitchell, O. and A. Lusardi (2015), “Financial Literacy and Economic Outcomes: Evidence and Policy Implications”, The Journal of Retirement, Vol. 3/1, pp. 107-114, https://doi.org/10.3905/jor.2015.3.1.107.

[7] OECD (2017), PISA 2015 Results (Volume IV): Students’ Financial Literacy, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264270282-en.

[6] OECD (2014), PISA 2012 Results: Students and Money (Volume VI): Financial Literacy Skills for the 21st Century, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264208094-en.

[8] Sasmito, P. et al. (2023), Consumptive Behavior in Adolescents and Its Impact on Financial Management: Case Studies and Practical Implications.

[2] Schützeichel, T. (2019), Financial Literacy and Saving for Retirement among Kenyan Households.

[11] Shabbir Rana, Q. (2022), Friendship and Finance: Understanding the Social Dimensions of Individual Investor Choices.

Notes

← 1. Advantaged students are defined as those who fall within the top quarter of the distribution of socio-economic status in their country and economy, as measured by the PISA index of economic, social and cultural status (ESCS). Likewise, disadvantaged students are defined as those who fall within the bottom quarter of the distribution of socio-economic status in their country and economy.

← 2. The remainder of this section refers to responses of “always” or “sometimes” together when discussing students who perform these actions; responses of “rarely” or “never” are referred to when discussing students do not perform these actions.

← 3. These attitudes are captured by students’ answers to the questions: How confident would you feel about doing the following things? “Understanding a sales contract” and “Planning my spending with consideration of my current financial situation”; and To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statements? "I buy things according to how I feel at the moment".

← 4. These attitudes are captured by students’ answers to the questions: To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statements? "My friends have a strong influence on my spending decisions", "I want to keep up with my friends' lifestyle", "Sometimes I spend more than I would like when I am with my friends", "I often buy what my friends recommend".

← 5. The remainder of this section refers to responses of “about once or twice a year”, “about once or twice a month”, “about once or twice a week”, “every day or almost every day” together when discussing students who have saved; and it refers to responses of “never” when discussing students who have not saved in the 12 months before the survey.

← 6. These attitudes are captured by students’ answers to the questions: To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statements? "Saving is something I do only if I have money left over", "I work towards long-term goals", "I make savings goals for certain things I want to buy or to do".