This chapter discusses students’ attitudes towards their own money matters. It begins by exploring whether students are interested in money matters. It then looks at whether such interest is linked to the exposure to financial education, and to students’ performance in financial literacy. The chapter also examines students’ self-assessment of their financial skills, and the extent to which this is related to their actual performance in financial literacy and to the exposure to financial education.

PISA 2022 Results (Volume IV)

6. Students’ attitudes towards money matters

Abstract

Motivation and self-belief influence how students learn and ultimately behave (Lo et al., 2022[1]; Edgar et al., 2019[2]; Zhao et al., 2021[3]). This is no less true for financial literacy than it is for the core subjects that PISA assesses (reading, mathematics and science). Indeed, a wealth of literature has provided evidence of a strong link between attitudes and financial behaviour. However, most studies have focused on post-secondary students or working adults over the age of 18, and their attitudes towards saving, debt, risk and borrowing (Białowolski et al., 2020[4]; Serido et al., 2015[5]; Hancock, Jorgensen and Swanson, 2013[6]; Shah and Patel, 2020[7]). Recent research confirms the link between financial attitudes and financial behaviours among children aged between 5 and 10 (Smith et al., 2018[8]), however there is still a gap in the literature on adolescents’ attitudes towards financial matters.

The PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment and questionnaire targeted 15-year-old students who do not yet – but may soon – face significant financial decisions. Their attitudes towards money matters today might be indicative of their behaviour tomorrow, of their readiness to take control of their own finances and of their willingness to improve their financial skills. These attitudes are so relevant to financial decision making that PISA includes the “skills and attitudes to apply” financial knowledge in its definition of financial literacy.

This chapter examines students’ interest in handling money matters and students’ confidence in their ability to do so, as measured by students’ self-assessed level of financial knowledge. The chapter also investigates the extent to which these attitudes vary according to student characteristics, and how they are related to students’ financial literacy and to their exposure to financial education in school and at home. While there is a wealth of resources aimed at helping teenagers manage their money, there is a lack of evidence as to whether students feel that they are able to do so. This chapter helps policy makers understand not just whether students can make good financial decisions (the subject of previous chapters), but whether students in their countries feel motivated and think they can do so.1

What the data tell us

On average across OECD countries and economies, 50% of students reported that they enjoy talking about money matters, but 36% of students reported that money matters are not relevant for them right now. More boys than girls (by 17 percentage points), and more advantaged students than disadvantaged students (by 6 percentage points) reported that they enjoy talking about money matters, on average across OECD countries and economies.

On average across OECD countries and economies, 80% of students felt confident about their ability to manage their money.

Exposure to financial education in school and parental involvement in financial matters were both associated with greater enjoyment in talking about money matters and greater confidence in one’s ability to manage money.

On average across OECD countries and economies, and after accounting for student characteristics and exposure to financial education at home and in school, students who reported that that they enjoy talking about money matters scored 5 points higher in financial literacy than students who did not, and students who agreed that they know how to manage their money scored 25 points higher than students who did not.

Students’ interest in money matters

Although many 15-year-old students might be able to leave all of their financial decisions to their parents, they will soon enter adulthood and need to take more control of their own money. Are they already interested in doing so?

The PISA 2022 financial literacy questionnaire asked students whether they strongly agreed, agreed, disagreed or strongly disagreed with the following statements:

“I enjoy talking about money matters”.

“Money matters are not relevant for me right now”.

On average across OECD countries and economies, 50% of students agreed or strongly agreed2 that they enjoy talking about money matters. This opinion was shared by 51% of students on average across all participating countries and economies, and was most prevalent amongst students in Costa Rica (61%), Peru (61%) and Portugal (62%). Students in Austria (40%), Italy (40%) and Czechia (41%) agreed with this statement the least across the 20 countries and economies that participated in the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment (Table IV.B1.6.1).

Some 36% of students, on average across OECD countries and economies and 38% on average across all participating countries and economies, agreed that money matters are not relevant for them right now. Fewer than one in three students in Hungary, Peru and Portugal agreed that money matters are not relevant for them right now, as opposed to more than one in two students in Saudi Arabia (61%) and the United Arab Emirates (51%). (Table IV.B1.6.1).

On average across the OECD, students who indicated that money matters are relevant for them – by disagreeing with the statement that money matters are not relevant for them - (64% of all students) were split equally between those who enjoy talking about money matters, and those who do not enjoy talking about money matters (32% of all students each). This was also the case in Norway where 33% of students enjoy talking about money matters while also indicating that they are relevant for them (by disagreeing with the proposed statement), and another 33% of students do not enjoy talking about money matters although they indicated that this topic is relevant for them (Table IV.B1.6.1).

In 10 participating countries and economies (Austria, Brazil, Bulgaria, the Canadian provinces*, Czechia, Hungary, Italy, Malaysia, the Netherlands* and Poland), most students indicated that although they perceive money matters as relevant for them, they do not enjoy talking about these matters. In another seven countries and economies, most students indicated that they both enjoy talking about money matters and find these matters relevant for them. In two countries and economies, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, the largest proportion of students agreed that they enjoy talking about money matters, while also agreeing that money matters are not relevant for them. This is not necessarily a contradiction – it is possible to enjoy talking about things that are not currently relevant to one’s life (Table IV.B1.6.1).

More boys (58%) than girls (42%) agreed that they enjoy talking about money matters, by 17 percentage points on average across OECD countries and economies. The gender gap was significant in favour of boys in 16 of the 20 participating countries and economies and was widest in Denmark* (26 percentage points) and the Netherlands* (25 percentage points); it was slightly in favour of girls in Malaysia (4 percentage points) (Table IV.B1.6.2).

However, more boys (38%) than girls (33%) agreed that money matters are not relevant to them right now (by 5 percentage points, on average across OECD countries and economies). A gap in this direction was observed in 14 of the 20 participating countries and economies, reaching 13 percentage points in Norway. The gender difference was slightly in favour of girls in Saudi Arabia, by 6 percentage points (Table IV.B1.6.2).

Interest in money matters was positively associated with socio-economic status. Indeed, 6 percentage points more advantaged students than disadvantaged ones reported agreeing that they enjoy talking about money matters, on average across OECD countries and economies. This gap was wider than 10 percentage points in Brazil, Czechia, Denmark*, Norway and Peru, and was significant in a further 10 countries and economies. Likewise, 4 percentage points more advantaged students than disadvantaged ones reported disagreeing that money matters are not relevant for them right now, on average across OECD countries/ economies. In Portugal, 10 percentage points more advantaged students than disadvantaged ones reported disagreeing that money matters are not relevant for them right now. The gap was not significant in 14 out of 20 countries and economies (Table IV.B1.6.3).

Students who are more exposed to financial education – whether at school or by their parents at home –, as measured through the index of familiarity with concepts of finance, agreed the most that they enjoy talking about money matters. On average across OECD countries and economies, students in the top quarter of the index of familiarity with concepts of finance agreed that they enjoy talking about money matters by 22 percentage points more than students in the bottom quarter of this index. A similar association was observed in all 20 participating countries and economies, with the gap ranging between over 25 percentage points in the Flemish community of Belgium, Denmark*, Hungary and the Netherlands*, and 7 percentage points in Saudi Arabia (Table IV.B1.6.5).

Likewise, students in the top quarter of the index of parental involvement in matters of financial literacy reported agreeing that they enjoy talking about money matters more (by 30 percentage points) than students in the bottom quarter of this index, on average across OECD countries and economies. Again, this association was observed across all participating countries and economies and ranged from 39 percentage points in Hungary and Portugal, to 21 percentage points in Austria (Table IV.B1.6.6).

Students who were more exposed to financial education at home and in school also disagreed the most that money matters are not relevant for them right now. Students in the top quarter of the index of familiarity with concepts of finance agreed that money matters are not relevant for them right now less (by 6 percentage points) than those in the bottom quarter of the index, on average across OECD countries and economies. A similar relationship was observed in 12 of the 20 participating countries and economies, and it was not significant in the remaining 8 countries and economies (Table IV.B1.6.5).

There was no difference in agreeing with the statement that money matters are not relevant right now between students in the top and bottom quarters of the index of parental involvement in matters of financial literacy, on average across OECD countries and economies. More students in the top quarter than in the bottom quarter of the index of parental involvement in matters of financial literacy reported that money matters are not relevant for them right now in Brazil, Bulgaria, the Canadian provinces*, Malaysia, Norway, Poland, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and the United States*. However, the opposite was reported by students in the Flemish community of Belgium, Denmark* and Spain (Table IV.B1.6.6).

Performance in the financial literacy assessment and interest in money matters

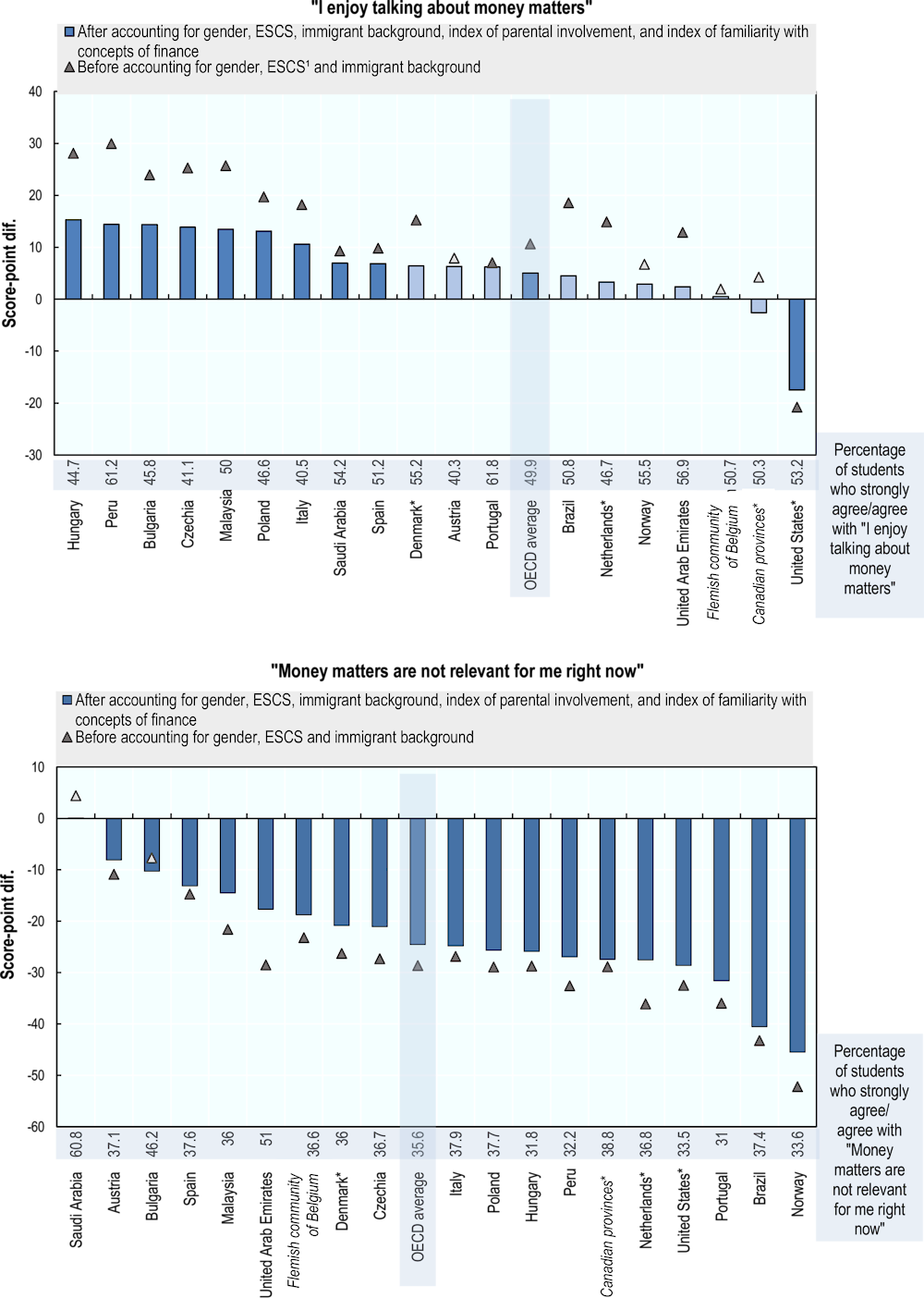

Students who were more interested in money matters scored higher in the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment. On average across OECD countries and economies, students who agreed that they enjoy talking about money matters scored 11 points higher in the assessment; after accounting for student characteristics, such as gender, socio-economic status and immigrant background, and exposure to financial education at home and in school, students who enjoy talking about money matters scored 5 points higher in the assessment (Figure IV.6.1 and Table IV.B1.6.7). Students who agreed that they enjoy talking about money matters scored higher in financial literacy in 9 out of 19 participating countries and economies with valid data, after accounting for student characteristics and exposure to financial education at home and in school. In Hungary, students who agreed that they enjoy talking about money scored 15 points higher in the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment than students who disagreed with this statement, after accounting for student characteristics and exposure to financial education at home and in school. Gaps of over 10 score points (after accounting for student characteristics) were also observed in Bulgaria, Czechia, Italy, Malaysia, Peru and Poland. Only in the United States*, students who agreed that they enjoy talking about money scored lower (by 18 points, after accounting for student characteristics and exposure to financial education at home and in school) than students who disagreed with this statement (Figure IV.6.1 and Table IV.B1.6.7).

Figure IV.6.1. Financial literacy performance, by students’ interest in money matters

Score-point difference between students who agreed/strongly agreed with the statement and those who disagreed/strongly disagreed

1. The socio-economic profile is measured by the PISA index of economic, social and cultural status.

Note: Score-point differences that are statistically significant are marked in a darker tone (see Annex A3).

For each graph, countries and economies are ranked in descending order of the score-point difference between students who agreed/strongly agreed with the statement and those who disagreed/strongly disagreed, after accounting for student characteristics, index of parental involvement, and index of familiarity with concepts of finance.

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 Database, Table IV.B1.6.1 and Table IV.B1.6.7.

The relationships between interest in money matters, exposure to financial education and financial literacy performance are complex ones. The results presented in this chapter indicate a positive relationship between interest in money matters and exposure to financial education, and between interest in money matters and financial literacy performance; based on this, it could be expected that self-reported exposure to financial education in school and financial literacy performance would also be positively associated, but this was not entirely supported by the results in Chapter 5. These results, however, are not necessarily contradictory, as PISA data do not allow to infer about their causality. It may be the case that students who are interested in money matters seek opportunities to learn through a variety of channels, including through optional school courses touching upon personal money matters, and that they end up improving their financial literacy – even if not necessarily via the teaching they receive in school. Further research may be needed to disentangle these relationships and identify their drivers.

Similarly, students who find money matters relevant to them achieve higher performance in financial literacy. Students who agreed that money matters are not significant for them right now scored lower in the financial literacy assessment – by 29 points before, and by 27 points after accounting for student characteristics and exposure to financial education at home and in school – on average across OECD countries and economies, compared to students who disagreed with this statement. This performance gap was observed in 17 of the 19 participating countries and economies with valid data, and was particularly large in Norway (49 points, after accounting for student characteristics) and Brazil (40 points) (and Table IV.B1.6.7).

Students’ self-assessed financial skills

The preceding section examined whether students are interested in money matters. Interest is an important motivation for young people to make informed financial decisions; confidence in one’s abilities is another.

The PISA 2022 financial literacy questionnaire asked students to self-assess their level of financial skills by indicating whether they strongly agreed, agreed, disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement: “I know how to manage my money”. Such a self-assessment can be taken as an indication of students’ confidence in their ability to manage their money.

On average across OECD countries and economies, 80% of students agreed or strongly agreed that they know how to manage their money. Slightly fewer students believed so in partner countries, as on average across all participating countries and economies, 77% of students agreed that they know how to manage their money. This opinion was most prevalent amongst students in Portugal (86%), followed by students in the Netherlands* (85%). Students in Brazil (63%) agreed with this statement the least, followed by students in Bulgaria (67%) (Figure IV.6.2 and Table IV.B1.6.1). It may not be surprising to observe such high percentages of students who think that they know how to manage their money, as the personal finances of 15-year-old students are relatively simple to manage.

The association between self-assessed level of financial skills and gender was modest in most participating countries and economies. On average across OECD countries and economies, slightly more boys (81%) than girls (79%) felt that they have the appropriate skills to manage their money. The gender gap was significant in favour of boys in 8 of the 20 participating countries and economies and was widest in Denmark* and Spain (6 percentage points). The gender gap was significant in favour of girls in Malaysia (5 percentage points), Austria (5 percentage points) and Saudi Arabia (12 percentage points) (Table IV.B1.6.2).

Self-assessment of financial skills was positively associated with socio-economic status. Indeed, more advantaged students than disadvantaged students agreed that they know how to manage their money, by 5 percentage points on average across OECD countries and economies. This gap was wider than 10 percentage points in Brazil, Bulgaria, Czechia, Malaysia, Peru and the United Arab Emirates; it was not significant in six participating countries and economies (Table IV.B1.6.3).

Students who were more exposed to financial education – whether at school or at home –agreed that they know how to manage their money the most. On average across OECD countries and economies, students in the top quarter of the index of familiarity with concepts of finance agreed that they know how to manage their money more than students in the bottom quarter of this index, by 18 percentage points. This positive association was observed in all participating countries and economies, with the gap being 20 percentage points or larger in, Brazil, Bulgaria, Costa Rica, Czechia, Malaysia, Norway, Peru, Spain, the United Arab Emirates and the United States* (Table IV.B1.6.5).

Likewise, students in the top quarter of the index of parental involvement in matters of financial literacy agreed that they know how to manage their money more than students in the bottom quarter of this index, 11 percentage points on average across OECD countries and economies. This association was observed across 19 out of 20 participating countries and economies and was larger than 20 percentage points in Brazil, Bulgaria, Costa Rica and the United Arab Emirates (Table IV.B1.6.6).

Performance in the financial literacy assessment and self-assessed financial skills

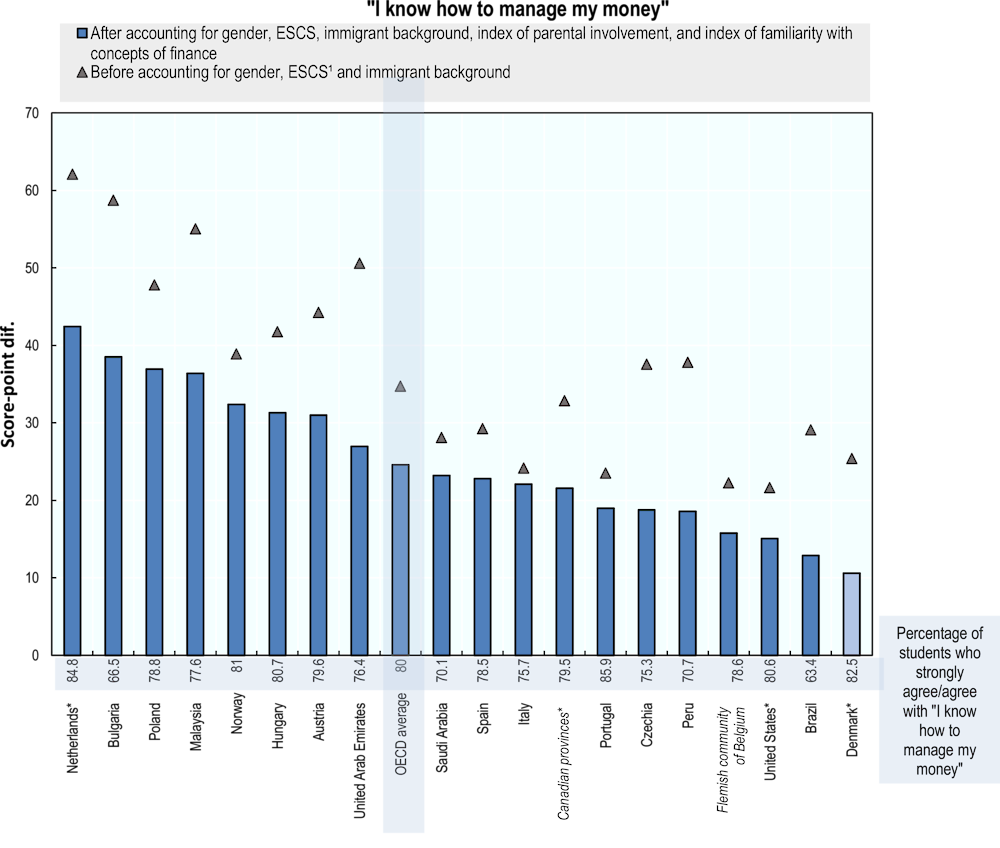

Students who assessed themselves as more knowledgeable about financial matters scored higher in the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment. On average across OECD countries and economies, students who agreed that they know how to manage money scored 25 points higher in financial literacy after accounting for student characteristics, such as gender, socio-economic status and immigrant background and exposure to financial education at home and in school. This relationship was significant in 18 out of the 19 participating countries and economies with valid data, ranging from 13 points (after accounting for student characteristics and exposure to financial education at home and in school) in Brazil, to 42 points in the Netherlands*. Gaps of over 30 score points, after accounting for student characteristics and exposure to financial education at home and in school, were also observed in Austria, Bulgaria, Hungary, Malaysia, Norway and Poland (Figure IV.6.2 and Table IV.B1.6.7).3

These results do not imply causal relationships, meaning that greater confidence in one’s financial skills may help students better perform in the PISA financial literacy assessment, or that high performing students may be aware of their high financial literacy skills. While it may be expected that self-assessed financial skills and performance in the financial literacy assessment are correlated, this correlation is not perfect, as both top and low performers in financial literacy may have a high assessment of their own financial skills (see Box IV.2.2 for further details).

It is also worth noting that the relationships between financial education in school, self-assessed financial skills and financial literacy performance are not straightforward, just as with interest in money matters. While exposure to financial education is associated with higher self-assessment of financial skills, and higher self-assessment of financial skills is associated with higher financial literacy performance, higher self-reported exposure to financial education in school is associated only to some extent with higher performance in financial literacy, as shown in Chapter 5. It may be the case that both being exposed to financial education in school and having greater financial skills help build confidence in one’s money-related skills, i.e. increase self-assessed financial skills, even if financial skills are not necessarily obtained in school. Again, more research is warranted to pin down the direction of these relationships, or whether different groups of students are affected in different ways by these factors.

Figure IV.6.2. Financial literacy performance, by students’ self-assessed financial skills

Score-point difference between students who agreed/strongly agreed with the statement and those who disagreed/strongly disagreed

1. The socio-economic profile is measured by the PISA index of economic, social and cultural status.

Note: Score-point differences that are statistically significant are marked in a darker tone (see Annex A3).

For each graph, countries and economies are ranked in descending order of the score-point difference between students who agreed/strongly agreed with the statement and those who disagreed/strongly disagreed, after accounting for student characteristics, index of parental involvement, and index of familiarity with concepts of finance.

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 Database, Table IV.B1.6.1 and Table IV.B1.6.7.

Table IV.6.1. Students’ attitudes towards money matters chapter figures

|

Figure IV.6.1 |

Financial literacy performance, by students’ interest in money matters |

|

Figure IV.6.2 |

Financial literacy performance, by students' self-assessed financial skills |

References

[4] Białowolski, P. et al. (2020), “Consumer debt attitudes: The role of gender, debt knowledge and skills”, International Journal of Consumer Studies, Vol. 44/3, pp. 191-205, https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12558.

[2] Edgar, S. et al. (2019), “Student motivation to learn: Is self-belief the key to transition and first year performance in an undergraduate health professions program?”, BMC Medical Education, Vol. 19/1, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-019-1539-5.

[6] Hancock, A., B. Jorgensen and M. Swanson (2013), “College Students and Credit Card Use: The Role of Parents, Work Experience, Financial Knowledge, and Credit Card Attitudes”, Journal of Family and Economic Issues, Vol. 34/4, pp. 369-381, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-012-9338-8.

[1] Lo, K. et al. (2022), “How Students’ Motivation and Learning Experience Affect Their Service-Learning Outcomes: A Structural Equation Modeling Analysis”, Frontiers in Psychology, Vol. 13, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.825902.

[5] Serido, J. et al. (2015), “The Unique Role of Parents and Romantic Partners on College Students’ Financial Attitudes and Behaviors”, Family Relations, Vol. 64/5, pp. 696-710, https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12164.

[7] Shah, A. and D. Patel (2020), “Impact Of Financial Behaviour And Financial Attitude On Level Of Financial Literacy Amongst Youth: An Sem Approach”, Vol. 19/4, pp. 8024-8036, https://doi.org/10.17051/ilkonline.2020.04.765196.

[8] Smith, C. et al. (2018), “Spendthrifts and Tightwads in Childhood: Feelings about Spending Predict Children’s Financial Decision Making”, Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, Vol. 31/3, pp. 446-460, https://doi.org/10.1002/bdm.2071.

[3] Zhao, Y. et al. (2021), “Self-Esteem and Academic Engagement Among Adolescents: A Moderated Mediation Model”, Frontiers in Psychology, Vol. 12, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.690828.

Notes

← 1. On average across OECD countries and economies, there was no significant difference between immigrant and non-immigrant students in either of the indices discussed in this chapter, nor in the responses to most of the individual statements analysed in this chapter. As such, immigrant and non-immigrant differences are not discussed in this chapter but are presented in tables in Annex B.

← 2. In this chapter, the responses “strongly agree” and “agree” were combined when discussing the percentage of students who agreed with certain statements.

← 3. Although in Austria and Bulgaria, results should be interpreted with caution due to the limited number of observations, as indicated in Table IV.B1.6.7.