This chapter describes the characteristics of staff and settings of the early childhood education and care sector serving children under age 3 and compares how resources are mobilised differently in Denmark, Germany, Israel and Norway. It explores the location, size and workforce of centre-based settings and analyses leader reports of the resource shortages they face. The chapter then gives a profile of staff working with children under age 3, including their experience, educational attainment, professional development needs and job satisfaction. It also investigates how staff differ across home-based and centre-based settings and according to the proportion of children under age 3 that they work with.

Quality Early Childhood Education and Care for Children Under Age 3

3. Characteristics of settings and staff in early childhood education and care for children under age 3

Abstract

Key messages

In Israel, children under age 3 are in early childhood education and care (ECEC) centres serving only children in this age range. In Denmark, Germany and Norway, most children under age 3 are in integrated ECEC centres also serving children over age 3. Centres are typically bigger in Germany than in Denmark or Norway but serve a smaller proportion of children under age 3. Target groups (the first group of children staff were working with on the last working day before the day of the survey) more often include only children under age 3 in Norway than in Germany.

A majority of centres are located in neighbourhoods offering a good environment to raise children, with only 10% of leaders in Germany and Israel and almost none in Norway reporting the contrary. In Israel, leaders who report that centres are not located in a good neighbourhood often mention litter lying around, while in Germany they report an accumulation of difficulties, including vandalism and ethnic tensions. In all countries, centres are found in cities of all sizes.

Despite the fact that centres in Germany and Israel serve more children, Norwegian centres comprise more staff than centres in Germany and Israel. Staff’s educational background and roles vary across countries. In Norway, the difference between teachers and assistants is pronounced: almost all teachers have attained at least a bachelor’s degree or equivalent (ISCED level 6), while only a minority of assistants have, and assistants rarely undertake tasks without children (e.g. documenting children’s development). In Germany, teachers are somewhat more likely than assistants to have at least a bachelor’s degree or equivalent (ISCED level 6 and above), and teachers and assistants spend similar amounts of time working directly with children. There are no assistants in Israel, and the majority of staff have a post-secondary degree distinct from a bachelor track (ISCED 4 or 5). In Germany and Norway, staff generally have worked several years in the ECEC sector before working with children under age 3.

Almost all centre staff in Germany and more than 70% of staff in Israel and Norway had elements covering working with children in their initial training. Topics covered in initial training in Norway are more comprehensive than those in Germany, and to an even greater extent than those in Israel. In all countries, staff most frequently report a need for professional development in topics such as child development, facilitating creativity and problem solving, and working with children with special educational needs.

A large proportion of centre leaders in Germany and Israel report a shortage of staff compared to the number of children enrolled. In addition, a majority of leaders in Israel report a shortage of qualified staff. Staff’s opinion about budget increases overwhelmingly favour improving salaries, especially in Israel, and funding professional development. Leaders and staff in Norway report fewer shortages.

Staff in all four countries feel very satisfied working in their ECEC centre, even though they do not feel valued enough by society and are dissatisfied with their salary. Staff in all countries report that a lack of resources is an important source of stress. In Germany, extra duties due to absent staff and excessive work documenting children’s development are also frequently reported to be a source of stress, while in Norway, the number of children in the classroom or playroom is the most frequently reported source of stress.

In Germany and Norway, where all or most centres are integrated across age groups, staff characteristics do not vary with the proportion of children under age 3 in the target group.

In Germany and Israel, staff in home-based settings tend to work more hours per week than staff in centre-based settings. They are also less likely to have reached a level of education equivalent to ISCED 6 or more.

Introduction

The Starting Strong Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS Starting Strong) provides internationally comparable information about settings serving children under age 3 and the staff they employ. The survey covers centre-based settings in Denmark (with low response rates), Germany, Israel and Norway, and home-based settings in Denmark (with low response rates), Germany and Israel. Centre leaders provide information on the main characteristics of centres, such as their size, location and workforce composition, and also report on the difficulties they are facing, while staff in all settings give extensive information about their educational backgrounds, their working conditions and well-being.

This chapter focuses on structural aspects of quality and the human resources that are mobilised in ECEC settings serving children under age 3. Staff practices with children and their capacity to create a good environment to foster child development depend on their own ability and experience, but also on the kind and amount of resources they have at their disposal.

This chapter first explores the characteristics of ECEC settings, including the age mix of children under and over age 3 in different countries, the characteristics of the children served, and the location of ECEC settings. It then describes the size of centre-based settings in terms of the number of children served and how the size of the workforce relates to the centre’s size, before analysing more specifically leader reports of human and material resources and the type of activities provided to parents. Next, the chapter focuses on staff pre-service training and the type of professional development staff would need to improve the quality of the education and care they provide. Finally, staff working conditions and well-being are approached through the perspective of both job satisfaction and the different sources of stress they report. When possible, comparisons are made with home-based settings.

Characteristics of early childhood education and care settings

Age mix of children in early childhood education and care settings for children under age 3

The four countries that participated in TALIS Starting Strong for settings serving children under age 3 have different types of ECEC provision. In Israel, children attend centre-based settings that only serve children under age 3. In contrast, most centre-based settings in Denmark and Germany and all in Norway are integrated, meaning they serve children from all ages until the start of primary school. Integrated centres can support continuity for children, parents and staff and help leaders shape consistent management practices across age groups. Nonetheless, the specific needs of children under age 3 may be neglected to some extent if they are significantly less well represented than older children.

Integrated centres in Denmark, Germany and Norway serve children of all ages up to entry in primary school. In these countries, children under age 3 only account for a minority of children in such centres. This is in part because in these three countries, the under age 3 category only includes children ages 1 and 2 while the category of older children includes children aged 3, 4 and 5. The older children category thus naturally represents a larger percentage of children. In addition, enrolment rates in ECEC for younger children are systematically lower than rates for older children. As a result, practices and characteristics measured at the centre level generally concern a population of children of which those under age 3 constitute only a minority. According to the survey, the average percentage of children under age 3 in centre-based settings is lower in Denmark and Germany than it is in Norway.

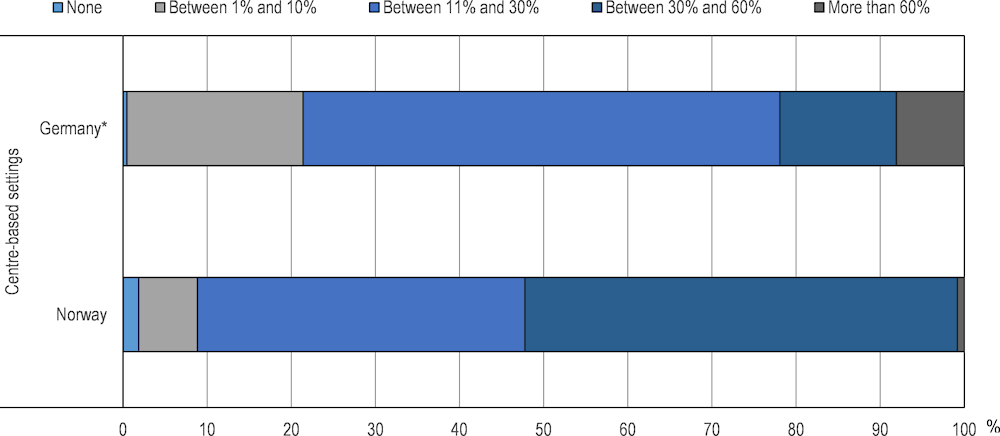

The proportion of children under age 3 varies from one centre to another, depending on the number of families in need of ECEC services and the centre’s capacity. Information about the type of centre (integrated or not) is not available in TALIS Starting Strong, but non-integrated centres will fall into the category of centres with more than 60% of children under age 3. As all centres are integrated in Norway, this category is almost empty (Figure 3.1). In Germany, non-integrated centres account for no more than 8% of all centres. Denmark (with low response rates) is similar in this respect.

Figure 3.1 confirms that centres in Norway tend to have a much greater proportion of children under age 3 than centres in Germany; a sizeable proportion of German centres serve a low proportion of children under 3. Nearly half of centres in Norway have a share of children under age 3 between 30% and 60%; this is about three times as many as in Germany. In a large majority of German centres, less than 30% of the children are under 3. In about one centre out of five in Germany, only 10% of children (or less) are under age 3.

Figure 3.1. Percentage of early childhood education and care centres with the following shares of children under age 3 in countries with integrated centres

* Estimates for sub-groups and estimated differences between sub-groups need to be interpreted with care. See Annex A for more information.

Note: Centres are not integrated in Israel and serve only children under age 3.

Source: OECD (2019[1]), TALIS Starting Strong 2018 Database, http://www.oecd.org/education/school/oecdtalisstartingstrongdata.htm.

Location of early childhood education and care settings

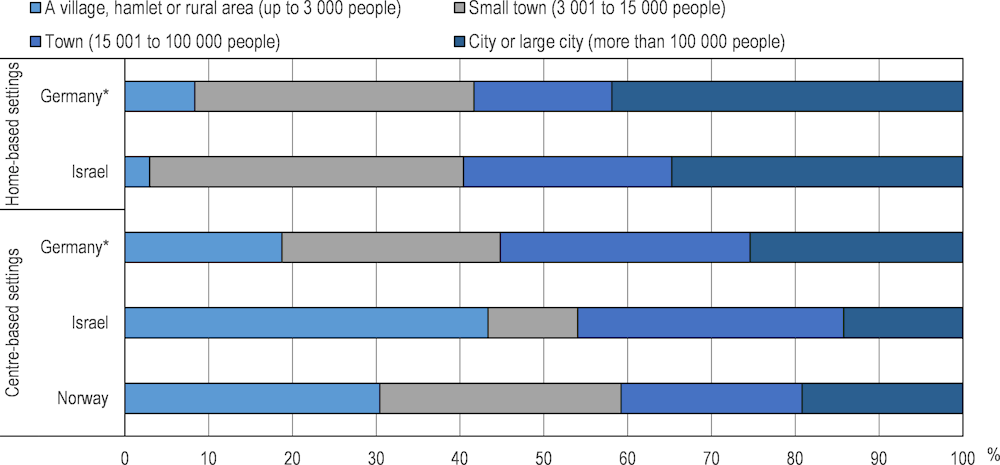

ECEC settings serving children under age 3 are spread across both rural and urban locations (Figure 3.2). Setting location is reported by leaders, and in the case of German and Israeli home-based leaders, this location is the staff’s home in which ECEC services are provided. All three countries – Germany, Israel and Norway (and in Denmark as well, with low response rates) – feature centre-based settings across all sizes of locations. In Germany (and in Denmark, with low response rates), the location of home-based settings reported by leaders is broadly comparable to that of centre-based settings, showing that home-based and centre-based settings generally cover the same geographic areas. In Israel, a large proportion of centre-based settings are located in villages (more than 40%), while only 3% of home-based leaders are located in such locations. Staff homes could nonetheless be located in villages.

Figure 3.2. Percentage of early childhood education and care settings by geographical location

* Estimates for sub-groups and estimated differences between sub-groups need to be interpreted with care. See Annex A for more information.

Note: Home-based settings serve a small number of children in Norway and were not included in the survey.

Source: OECD (2019[1]), TALIS Starting Strong 2018 Database, http://www.oecd.org/education/school/oecdtalisstartingstrongdata.htm.

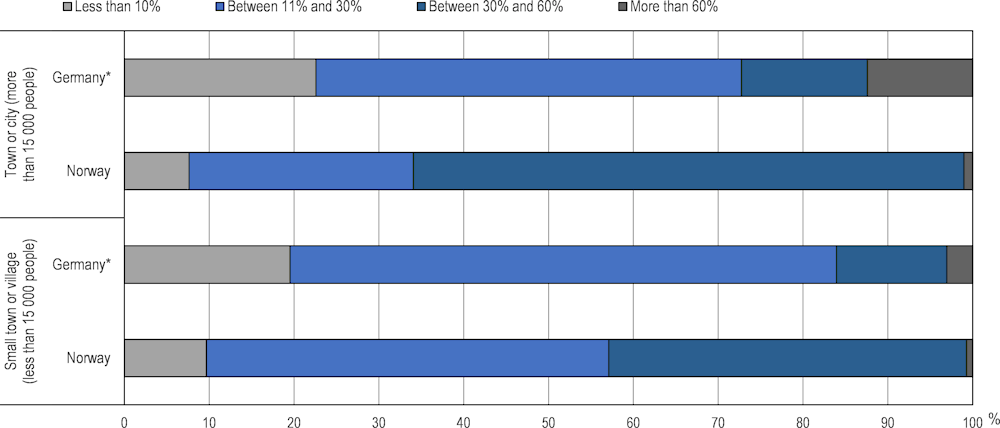

In Germany and Norway, integrated centre-based settings in small towns or villages with less than 15 000 inhabitants tend to have a lower proportion of children under age 3 than those in larger towns or cities (Figure 3.3). In Norway, 66% of centre-based settings located in larger towns or cities serve roughly equal proportions of children under and over age 3, compared to 42% in smaller towns (Denmark, with low response rates, displays a similar pattern). In Germany, the proportion of centre-based settings with more than 60% of children under age 3 (likely to be non-integrated settings) is 13% in larger towns or cities and only 3% in smaller towns or villages. Combined with the lower proportion of centre-based settings with a waiting list in smaller towns (see Chapter 2), these differences suggest a lower demand of ECEC services for children under age 3 in smaller towns. This lower demand could be driven by a higher proportion of young mothers not working or more frequent use of informal childcare.

Figure 3.3. Percentage of children under age 3 in early childhood education and care centres and type of location in countries with integrated centres

* Estimates for sub-groups and estimated differences between sub-groups need to be interpreted with care. See Annex A for more information.

Note: Centres are not integrated in Israel and serve only children under age 3.

Source: OECD (2019[1]), TALIS Starting Strong 2018 Database, http://www.oecd.org/education/school/oecdtalisstartingstrongdata.htm.

The neighbourhood quality of centre-based settings provides information on two different aspects of ECEC settings. First, the neighbourhood quality of the centre is associated with the conditions and challenges staff face in their daily work with children in the centre. Second, centre neighbourhood quality is related to the social and family environment of the children enrolled in the centre. To interpret the data, one should keep in mind that the existence of centre-based settings in more difficult neighbourhoods would show that families living in deprived areas can have access to ECEC services. However, the absence of leaders reporting poor neighbourhood quality suggests either a lack of provision of services in these areas or a good neighbourhood quality across the country.

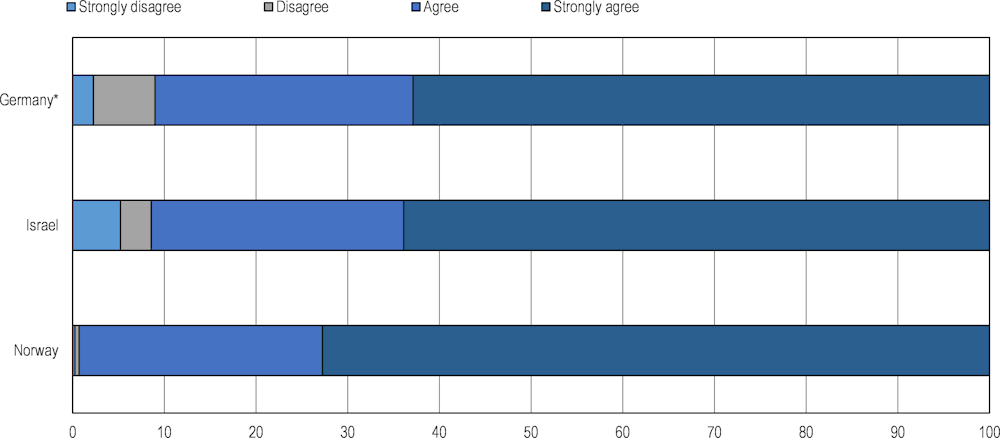

The survey reveals centre leaders’ individual assessment of the quality of the neighbourhood as a good place to bring up children (Figure 3.4). Across all three countries, leaders overwhelmingly agree (or strongly agree) that the centre neighbourhood is a good environment to bring up children, with a vast majority (60-75%) even strongly agreeing. In Germany and Israel, about 10% of leaders disagree or strongly disagree their centre neighbourhood is a good environment to bring up children. In Norway, almost no leaders report that their centre neighbourhood is not a good environment to raise children.

Figure 3.4. Neighbourhood quality of early childhood education and care centres

* Estimates for sub-groups and estimated differences between sub-groups need to be interpreted with care. See Annex A for more information.

Source: OECD (2019[1]), TALIS Starting Strong 2018 Database, http://www.oecd.org/education/school/oecdtalisstartingstrongdata.htm.

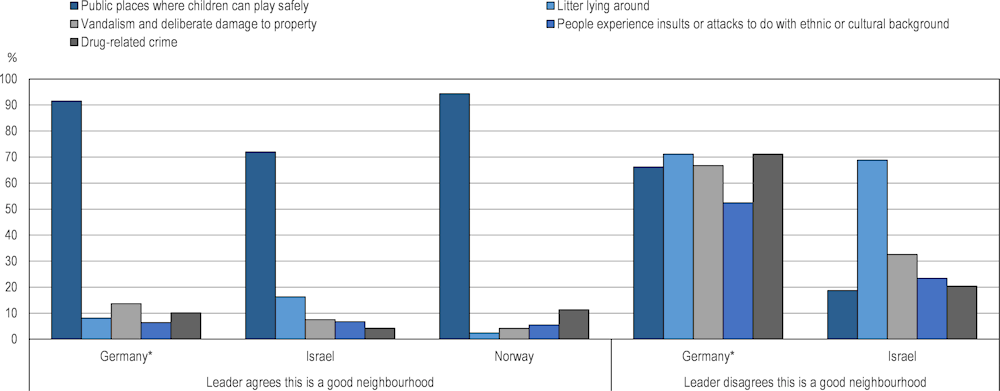

In addition to rating neighbourhoods as a good place to raise children, neighbourhood quality can be assessed along many other dimensions, which raise different policy challenges. TALIS Starting Strong includes a set of questions about specific characteristics of centres’ neighbourhoods. The proportion of leaders agreeing with five statements, depending on their answer about the overall quality of the neighbourhood, helps inform the reason why a neighbourhood may be considered to be less good (Figure 3.5). Across all countries, good neighbourhoods are alike. Centre leaders reporting a good neighbourhood also agree or strongly agree that there are public places where children can safely play. Correspondingly, generally less than 10% of them agree with negative statements related to criminality (“drug-related crime” or “vandalism and deliberate damage to property”), to cleanliness (“there is litter lying around”) or to ethnic tensions (“people experience insults or attacks to do with ethnic or cultural background”). In Norway, given the absence of reported poor quality neighbourhoods, this favourable environment concerns nearly all centres.

Contrastingly, among leaders in Germany and Israel that do not believe their neighbourhood is a good place to raise children, opinions diverge on more specific statements. While in Germany a majority of these leaders still report there are public places where children can safely play (more than 60%), in Israel less than 20% of leaders agree with this statement. Leaders in Germany agree more frequently with statements related to criminality (drugs and vandalism) and ethnic tensions than leaders in Israel. However, in both countries, a majority of leaders who believe their neighbourhood is a good place to bring up children report there is litter lying around. These profiles suggest an accumulation of disadvantages in the neighbourhoods of some German centres (Denmark, with low response rates, is similar), while the neighbourhoods of some Israeli centres present more concerns about safety in addition to the presence of litter. These results should be interpreted with caution because of the small sample sizes (i.e. few centre leaders have a poor opinion of the neighbourhood around their centre) and therefore the lack of precision of these statistics.

Figure 3.5. Aspects of the neighbourhood quality of early childhood education and care centres

* Estimates for sub-groups and estimated differences between sub-groups need to be interpreted with care. See Annex A for more information.

Note: Statistics for centres in Norway in which leaders disagree their centre is in a good neighbourhood to bring up children are not shown because of the very small size of the subsample.

Source: OECD (2019[1]), TALIS Starting Strong 2018 Database, http://www.oecd.org/education/school/oecdtalisstartingstrongdata.htm.

Characteristics of children in early childhood education and care settings

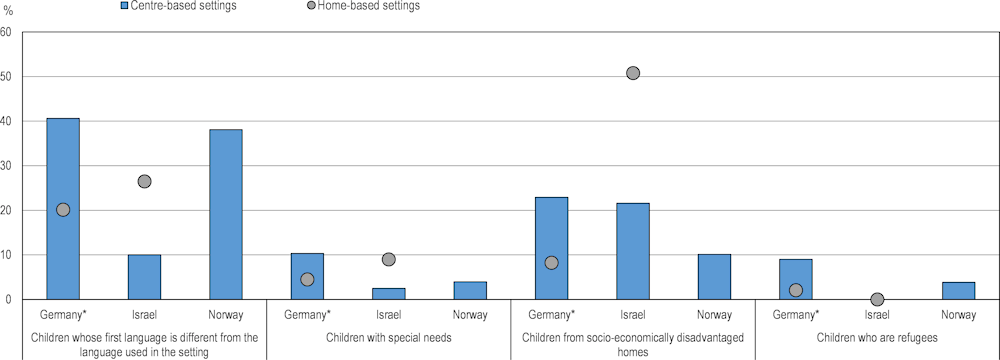

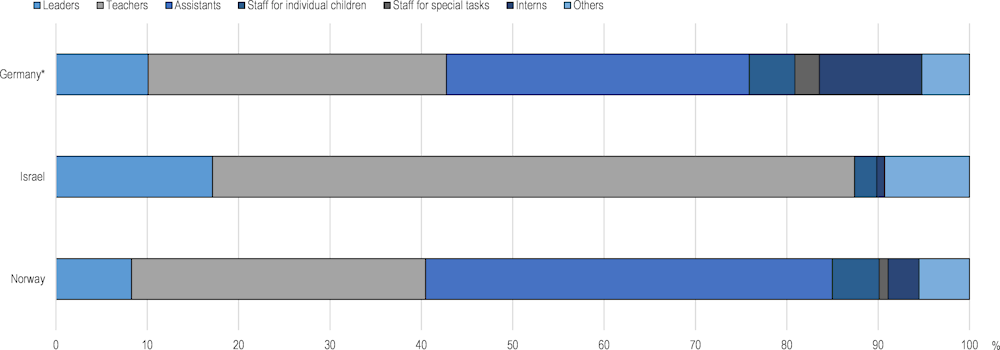

Leaders report the proportion of children in their centres with the following characteristics: with a different first language than that of the centre, who have special needs, are refugees or come from socio‑economically disadvantaged households (Figure 3.6). Children with these characteristics can require specific actions, skills or training on behalf of the centre’s staff in order to implement adapted practices and support high-quality ECEC for all children. In centre-based settings, about 40% of leaders in Germany and Norway report having at least 10% of children with a different first language, compared to only 10% of leaders in Israel. The proportion of children with special needs or who are refugees rarely exceeds 10% across all three countries. In both cases, the highest prevalence is observed in German centres, and even here, no more than 10% of leaders report having many children with special needs or refugees in their centres. Leaders in Denmark (with low responses rates) more frequently report more than 10% of children with special educational needs in their centres than the other participating countries. TALIS Starting Strong refers to socio-economically disadvantaged homes as homes lacking the necessities or advantages of life, such as adequate housing, nutrition or medical care. About 20% of centre leaders in Germany and Israel report that at least 10% of children come from such homes, whereas in Norway only approximately 10% of leaders report having many children from socio‑economically disadvantaged homes in their centres. These different trends across countries reflect each country’s socio-demographic make-up.

Figure 3.6. Characteristics of children in early childhood education and care settings according to type of setting

* Estimates for sub-groups and estimated differences between sub-groups need to be interpreted with care. See Annex A for more information.

Note: Home-based settings serve a small number of children in Norway and were not included in the survey.

Source: OECD (2019[1]), TALIS Starting Strong 2018 Database, http://www.oecd.org/education/school/oecdtalisstartingstrongdata.htm.

A comparison of home-based and centre-based settings in Germany and Israel shows that the two types of settings tend to serve different segments of the population. In Israel, a larger percentage of home-based settings include a significant percentage of children whose first language is different from the language used in the setting, who are from socio-economically disadvantaged homes or who have special needs. This finding could suggest that some children have less access to centre-based settings. In Germany, where home-based settings serve a relatively small proportion of the population, the proportion of children with these various characteristics is less than what leaders report in centre-based settings. This pattern suggests more even access to centres across diverse groups.

Early childcare education and care setting size and resources

This section provides an overview of the different types of resources available in ECEC settings and how they are distributed in each country, starting with the most important: human resources.

Setting size, number of staff and categories of staff

Centre size is described in TALIS Starting Strong using the number of children in the centre. The size of centre-based settings can influence staff working conditions, leader management style and workload, and the amount and diversity of financial and human resources available. Centre size also determines the scope of co-operation possibilities between staff and shapes the daily experience of children.

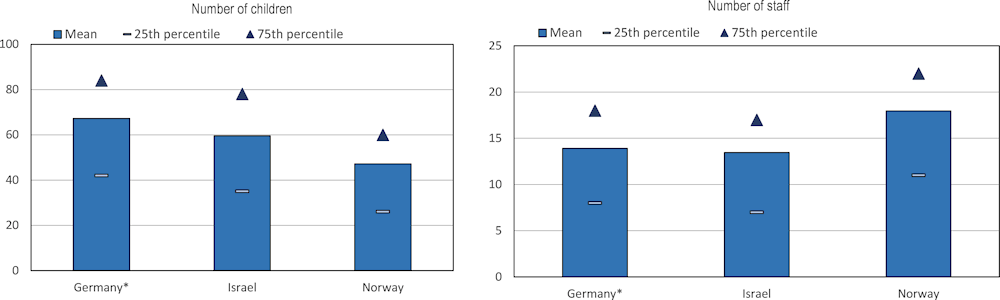

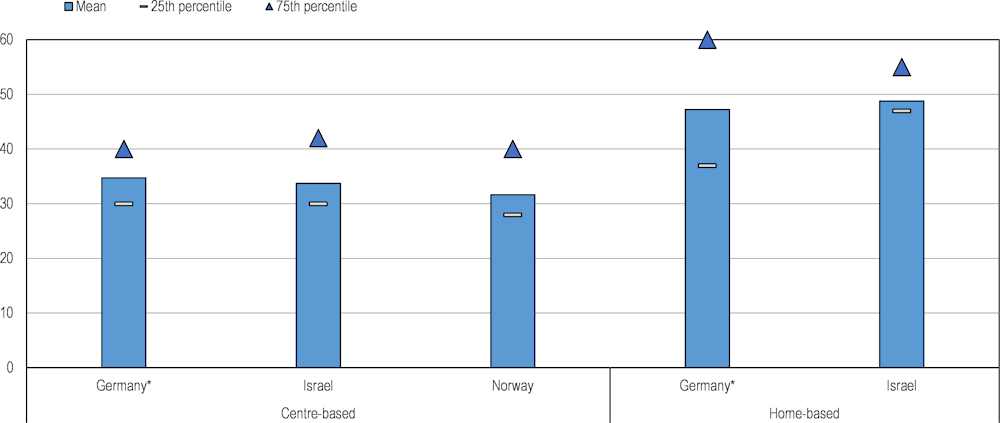

The number of children in centres varies both across and within countries (Figure 3.7). On average, German and Israeli centres are larger (60 children or more) than Norwegian centres (47 children). In Germany and Norway, where centres are typically age-integrated, these figures account for children of all ages from one to five. While Norwegian centres serve fewer children than German centres, a larger proportion of children are under 3. Centre sizes vary extensively within countries, with, for instance, 25% of German centres serving less than 40 children while 25% of centres serve more than 80 children.

TALIS Starting Strong also includes information on the number of staff per centre, as reported by leaders (Figure 3.7). As leaders’ reports do not distinguish between staff working part-time or full-time, these figures can differ from administrative data sources. Staff counts are generally close to 15 on average. However, from one country to another, average staff counts do not follow children counts. In particular, while Norway features the smallest centres with respect to the number of children, staff counts are the highest on average, which reflects the important investment Norway has made in ECEC services (see Chapter 2) as well as the strong representation of children under age 3, who require more individualised attention.

Figure 3.7. Size distribution of centre-based settings

* Estimates for sub-groups and estimated differences between sub-groups need to be interpreted with care. See Annex A for more information.

Source: OECD (2019[1]), TALIS Starting Strong 2018 Database, http://www.oecd.org/education/school/oecdtalisstartingstrongdata.htm.

In Germany and Norway, where all or most centres are integrated, not all staff necessarily work with children under age 3. In TALIS Starting Strong, leaders report about all staff, including those who do not work with children under age 3. As a result, it is not possible to know the proportion of staff in integrated centres that work with children under age 3. However, only staff working with children under age 3 are included in the target population of staff. Staff working in integrated centres, but not with children under age 3, are excluded.

TALIS Starting Strong includes several categories of staff. The main categories are leader, teacher and assistant, with teachers defined as having the most responsibilities for children in the classroom/playroom. Interns, staff for individual children and staff for special tasks are also included as well as an “other” category. The distribution of the workforce across these categories in centre-based settings varies across countries, reflecting different types of working organisation (Figure 3.8). Germany and Norway have a similar proportion of teachers (about one-third) among the workforce, but the percentage of assistants is smaller in Germany. In Denmark (with low response rate), centres employ more teachers than assistants. German centres show a relatively high share of interns. The centre organisation is different in Israel, with no staff serving as assistants. More than 70% of the workforce in Israel is reported to be teachers, implying that the management of daily work with children could be less hierarchical. Other types of staff are rare. In Germany and Norway, about 5% of the workforce are reported to be staff working with individual children (only 2% in Israel). Staff for special tasks represent an even smaller proportion of the workforce.

Figure 3.8. Human resources in centre-based settings

* Estimates for sub-groups and estimated differences between sub-groups need to be interpreted with care. See Annex A for more information.

Source: OECD (2019[1]), TALIS Starting Strong 2018 Database, http://www.oecd.org/education/school/oecdtalisstartingstrongdata.htm.

Working hours

Across countries, staff working in centre-based settings report working a similar number of hours per week: 32-35 (Figure 3.9). Within each country, the range is limited, with half of the staff working 30‑40 hours per week. Staff in Norwegian centres work a bit less than in Germany and Israel. However, staff in home-based settings report having much longer working weeks than staff in centre-based settings (47 hours on average in Germany and 49 in Israel). In Germany, one in four home-based staff reports working at least 60 hours a week.

Figure 3.9. Total weekly working hours for all staff in early childhood education and care settings

* Estimates for sub-groups and estimated differences between sub-groups need to be interpreted with care. See Annex A for more information.

Note: Home-based settings serve a small number of children in Norway and were not included in the survey.

Source: OECD (2019[1]), TALIS Starting Strong 2018 Database, http://www.oecd.org/education/school/oecdtalisstartingstrongdata.htm.

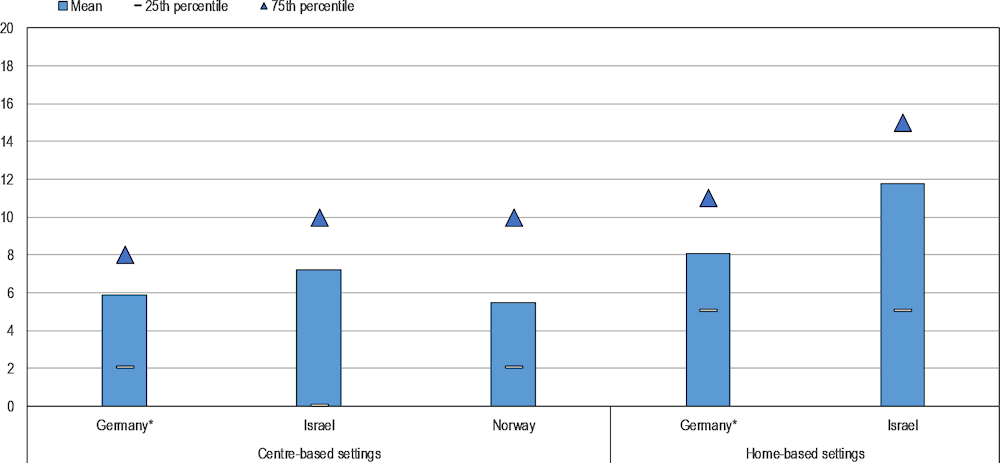

An important aspect of working hours is the distinction between time spent with children and time spent on other tasks. Time not spent with children can be dedicated to tasks closely related to children, such as the preparation of activities to do with children or collaboration with parents and colleagues, or it can be focused on more administrative tasks. In centre-based settings, staff typically spend six hours per week on tasks outside of working with children in Germany and Norway and slightly more in Israel (seven hours), accounting for 17-22% of total working hours (Figure 3.10). The number of hours spent on other tasks is higher in home-based settings, reaching 8 hours in Germany and 12 in Israel. Staff in Israeli home-based settings spent thus one-fourth of their working hours away from children; however, their average number of hours spent working directly with children is still greater than the total average hours worked by staff in centre-based settings.

The number of hours spent on tasks aside from working with children also varies across staff. Some staff spend almost all of their time working directly with children. In German and Norwegian centres, 25% of staff spend less than two hours a week working without children while in Israel 25% do not report any work without the presence of children. Other staff spend many hours per week working on tasks that do not directly involve children. In Israel and Norway, 25% of staff spend more than ten hours a week on tasks not with children (eight hours in Germany). Importantly, leaders only account for a minority of these 25%, since leaders comprise less than 10% of the workforce. This pattern suggests a division of tasks across staff within a centre. In home-based settings, the number of hours not spent with children also varies a lot across staff, but the 25% of staff who spend the least amount of time without children still spend more than four hours per week on tasks without children. In home-based settings, the possibilities to allocate tasks across staff are more constrained and there is a minimum amount of work that is better done in the absence of children.

Figure 3.10. Number of weekly working hours not spent with children

* Estimates for sub-groups and estimated differences between sub-groups need to be interpreted with care. See Annex A for more information.

Note: Home-based settings serve a small number of children in Norway and were not included in the survey.

Source: OECD (2019[1]), TALIS Starting Strong 2018 Database, http://www.oecd.org/education/school/oecdtalisstartingstrongdata.htm.

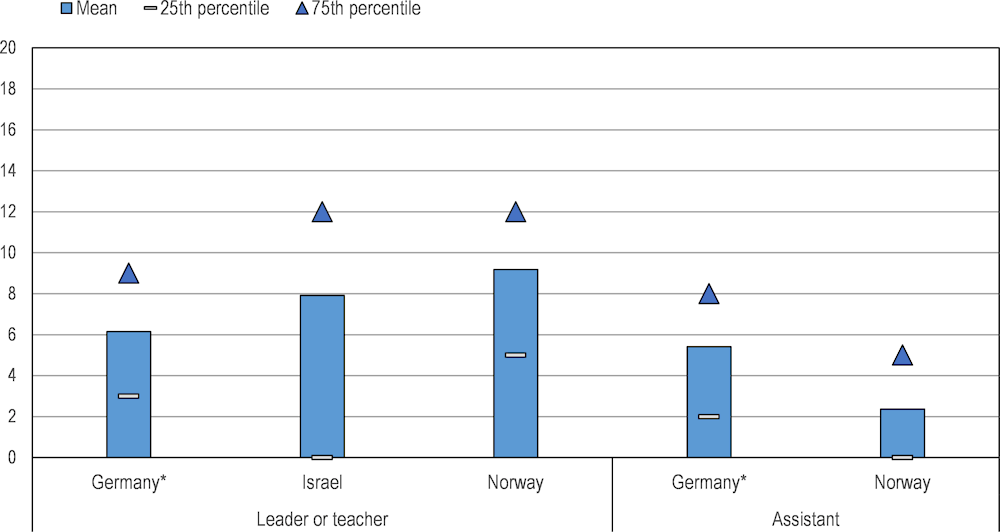

Differences across and within countries in the working time spent without children can also account for differences between assistants’ and teachers’ assignments (Figure 3.11). Assistants and teachers in Germany in centre-based settings have very similar patterns of time spent without children, with assistants spending slightly less time without children. Within each staff category, the variation remains equivalently large, showing that administrative/relational duties are shared by teachers and assistants. However, such a balance cannot be not found in Norway (or Denmark, with low response rates). Teachers spend on average nine hours per week on tasks without children and assistants only spend two, which suggests different roles and responsibilities across these two categories.

Figure 3.11. Staff role and number of hours per week not spent with children

* Estimates for sub-groups and estimated differences between sub-groups need to be interpreted with care. See Annex A for more information.

Note: In Israel, the distinction between assistant and teacher does not apply.

Source: OECD (2019[1]), TALIS Starting Strong 2018 Database, http://www.oecd.org/education/school/oecdtalisstartingstrongdata.htm.

Resource needs

Countries differ in terms of the number of staff and children at the centre level (Figure 3.7). To assess whether these differences have implications for the quality of the education and care provided, this information can be combined with answers from leaders on issues they have identified as having an impact on the provision of a quality environment for children (Table 3.1). At the centre level, the number of staff per child is similar in Germany and Israel. In both countries, close to half of the centre leaders report they have a shortage of staff compared to the number of enrolled children (in Denmark, with low response rates, as well). The number of staff per child at the centre level is more favourable in Norway, where leaders rarely report that a shortage of staff is “quite a bit” or “a lot” of a barrier to providing a quality environment (14%). Israel stands apart from Germany insofar as leaders are also more likely to report a shortage of qualified staff (54% versus 31%). In Israel, the high proportion of leaders who report both shortages suggests that the shortage of the number of staff per child is driven by a shortage of qualified staff.

Leaders also report shortages of specific types of staff: those with competence in working with children from socio-economically disadvantaged homes, speaking another language or with special needs. These figures are best understood in combination with Figure 3.6, which presents the proportion of centres in which the proportion of such children exceeds 10%. In Norway, few leaders report a shortage of staff with these specific competences. Still, the large proportion of centres with more than 10% of children speaking another language at home raises needs that are not all met, given that 17% of leaders report lacking staff with competence in working with such children. In Germany, about one leader in four reports a shortage of staff in all three categories. In Israel, 38% of leaders report a shortage of staff with competence in working with children with special needs. The reported shortage of this competence combined with the small proportion of children with special needs enrolled in centres could suggest that leaders consider that some children have special needs but have not been identified as such.

Table 3.1. Resource shortages in early childhood education and care centres according to leaders

Proportion of leaders who report that the following issues hinder the centre’s capacity to provide a quality environment for children quite a bit or a lot

|

Germany* |

Israel |

Norway |

Denmark** |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Shortage of staff |

|||||

|

|

Qualified staff |

31% |

54% |

5% |

15% |

|

|

Staff for the number of enrolled children |

49% |

46% |

14% |

62% |

|

|

Staff with competence in working with children speaking another language |

29% |

12% |

17% |

23% |

|

|

Staff with competence in working with children from socio-economically disadvantaged homes |

25% |

29% |

5% |

13% |

|

|

Staff with competence in working with children with special needs |

27% |

38% |

8% |

17% |

|

Shortage or inadequacy of space |

|||||

|

|

Indoor space |

25% |

28% |

8% |

22% |

|

|

Outdoor space |

13% |

21% |

2% |

7% |

|

Shortage or inadequacies of material resources |

|||||

|

Play or learning materials |

4% |

20% |

1% |

11% |

|

|

|

Digital technology for play and learning |

32% |

14% |

7% |

22% |

|

|

Insufficient internet access |

32% |

11% |

11% |

16% |

* Estimates for sub-groups and estimated differences between sub-groups need to be interpreted with care. See Annex A for more information.

** Low response rates in the survey may results in biases in the estimates reported and limit the comparability of the data.

Notes: Colours vary from dark blue (0%) to white (50%) to dark grey (100%).

Source: OECD (2019[1]), TALIS Starting Strong 2018 Database, http://www.oecd.org/education/school/oecdtalisstartingstrongdata.htm.

In contrast to centre leaders in Norway, leaders in Germany and Israel report a shortage of material resources or space. Leaders in Israel are the only ones to highlight a shortage of play or learning materials (20%), while respectively 30% and 31% of German leaders report insufficient Internet access and inadequacy of digital technology for play and learning, respectively. One in four leaders in Germany and Israel report inadequate indoor space.

Insights from leader reports on centre shortages are complemented by staff accounts on the importance of different spending priorities for the sector as a whole (Table 3.2). The spending priorities proposed to staff include items similar to those presented to leaders (see Table 3.1). However, comparisons should be made with caution, as leaders report on shortages in their centres while staff report on spending priorities for the ECEC sector as a whole. In addition, a current shortage of resources is different from a priority for future budgets. For instance, staff can consider that priorities exist while leaders do not necessarily have shortages, which can explain why the frequency of “high importance” priorities among staff appear higher.

There is no systematic agreement between staff’s spending priorities and leaders’ reports of shortages, especially in Norway. In all countries, more than three staff out of four agree that reducing group sizes by recruiting more staff is of high importance for the sector as a whole, including in Norway, where few leaders report a shortage of staff. Staff in Norway also prioritise spending to support children with special needs (66%), although leaders did not report any shortage of staff with competence in this area. Staff in Israel agree with leaders on this point, highlighting that this as an area to prioritise funding and potentially address staff shortages. Staff in Israel are the only ones reporting frequently (71%) that investment in toys, learning materials and outdoor facilities are of highly important spending priorities, underscoring the shortage of outdoor space or toys and learning materials reported by leaders.

The list of spending priorities that were proposed to staff also includes items without parallel items in leader reports, including improving salaries and offering high-quality professional development, which are most frequently reported as being of high importance. Improving salaries is rated as of high importance by almost all staff in Israel (94%), three-fourths of staff in Germany, and half of staff in Norway (and in Denmark, with low response rates). Offering high-quality professional development is most often rated as an important spending priority in Israel (79%) and Norway (56%).

Table 3.2. Budget priorities in early childhood education and care centres according to staff

Proportion of staff reporting that the following spending priorities are of high importance for the sector as a whole

|

|

Germany* |

Israel |

Norway |

Denmark** |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Reducing group sizes by recruiting more staff |

78% |

84% |

74% |

83% |

|

Improving salaries |

73% |

94% |

49% |

43% |

|

Supporting children with special needs |

49% |

76% |

66% |

64% |

|

Offering high-quality professional development |

47% |

79% |

56% |

52% |

|

Reducing staff administration load by recruiting more support staff |

44% |

74% |

26% |

24% |

|

Investing in toys, learning materials and outdoor facilities |

40% |

71% |

22% |

22% |

|

Supporting children from disadvantaged or migrant backgrounds |

30% |

61% |

28% |

39% |

|

Improving centre buildings and facilities |

44% |

64% |

17% |

16% |

* Estimates for sub-groups and estimated differences between sub-groups need to be interpreted with care. See Annex A for more information.

** Low response rates in the survey may result in biases in the estimates reported and limit the comparability of the data.

Note: Colours vary from dark blue (0%) to white (50%) to dark grey (100%).

Source: OECD (2019[1]), TALIS Starting Strong 2018 Database, http://www.oecd.org/education/school/oecdtalisstartingstrongdata.htm.

Activities to engage with parents

Beyond human and material resources, the type of activities involving parents also matter for a child’s development. Although strong parent-teacher and parent-assistant partnerships and communication are important for children of all ages, they are particularly relevant for children under age 3. Research underlines that close partnerships allow parents and educators to share information about the child, promoting continuity between home and early childhood education, parents’ confidence in their childcare arrangement, as well as the quality of care (Coelho et al., 2019[2]; Leavitt, 1995[3]; Owen et al., 2008[4]). Activities proposed to parents can foster and extend relationships between parents and staff.

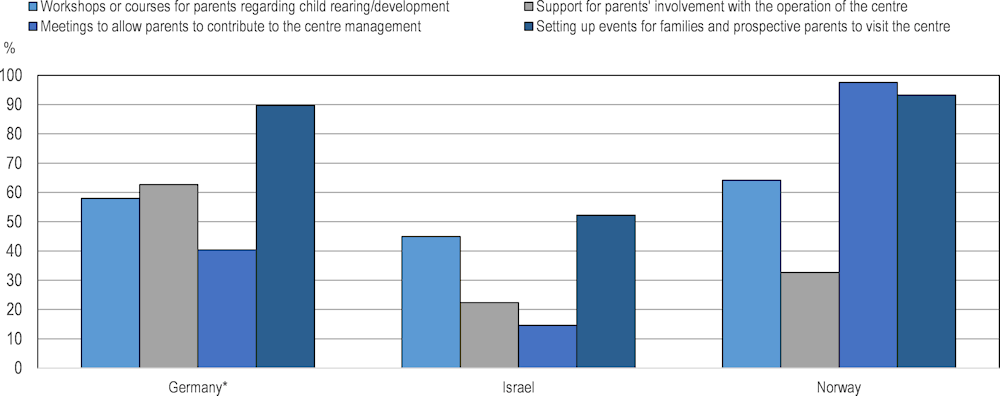

Leaders participating in TALIS Starting Strong report on the provision of three types of activities to involve parents in the centre’s activities over the last 12 months: 1) workshops or courses for parents; 2) parental participation in the centre’s operations (e.g. fundraising, cleaning); and 3) parental participation in the centre’s management decisions (Figure 3.12). All of these activities can contribute in their own ways to create continuity in the education and care environments between children’s ECEC settings and homes. A majority of centres set up workshops or courses regarding child rearing or child development in Germany and Norway (58% and 63% respectively), less so in Israel (44%). The opportunities for parent involvement with the centre’s operations is more country-specific. In Germany, 62% of leaders report this type of parental involvement. It is much less frequent in Norway (32%) and Israel (21%). Involving parents in the centre’s management decisions also varies greatly across countries, from Norway where nine out of ten leaders report this kind of parental involvement, to Israel, where only 14% of leaders report these opportunities for parents.

Figure 3.12. Activities provided by the early childhood education and care centre to parents or guardians

* Estimates for sub-groups and estimated differences between sub-groups need to be interpreted with care. See Annex A for more information.

Source: OECD (2019[1]), TALIS Starting Strong 2018 Database, http://www.oecd.org/education/school/oecdtalisstartingstrongdata.htm.

Age composition of the target group in early childhood education and care centres

Integrated centres in Germany and Norway serve children from age 1 to age 5, and occasionally children who are somewhat younger and somewhat older. In such centres, only staff who worked regularly with children under age 3 were sampled. In Israel, although centres are not integrated, centres serving children under age 3 also serve children age 3. TALIS Starting Strong includes questions on the target group, which is the first group of children that staff worked with on their last working day before the day of the survey. The age composition of the target group can have an important impact on staff practices and children’s experiences. Staff must adapt their practices to the age diversity of the children. Three different types of target groups are possible: 1) target groups with few or no children under age 3; 2) target groups with few or no children over age 3; and 3) target groups with a mix of all ages.

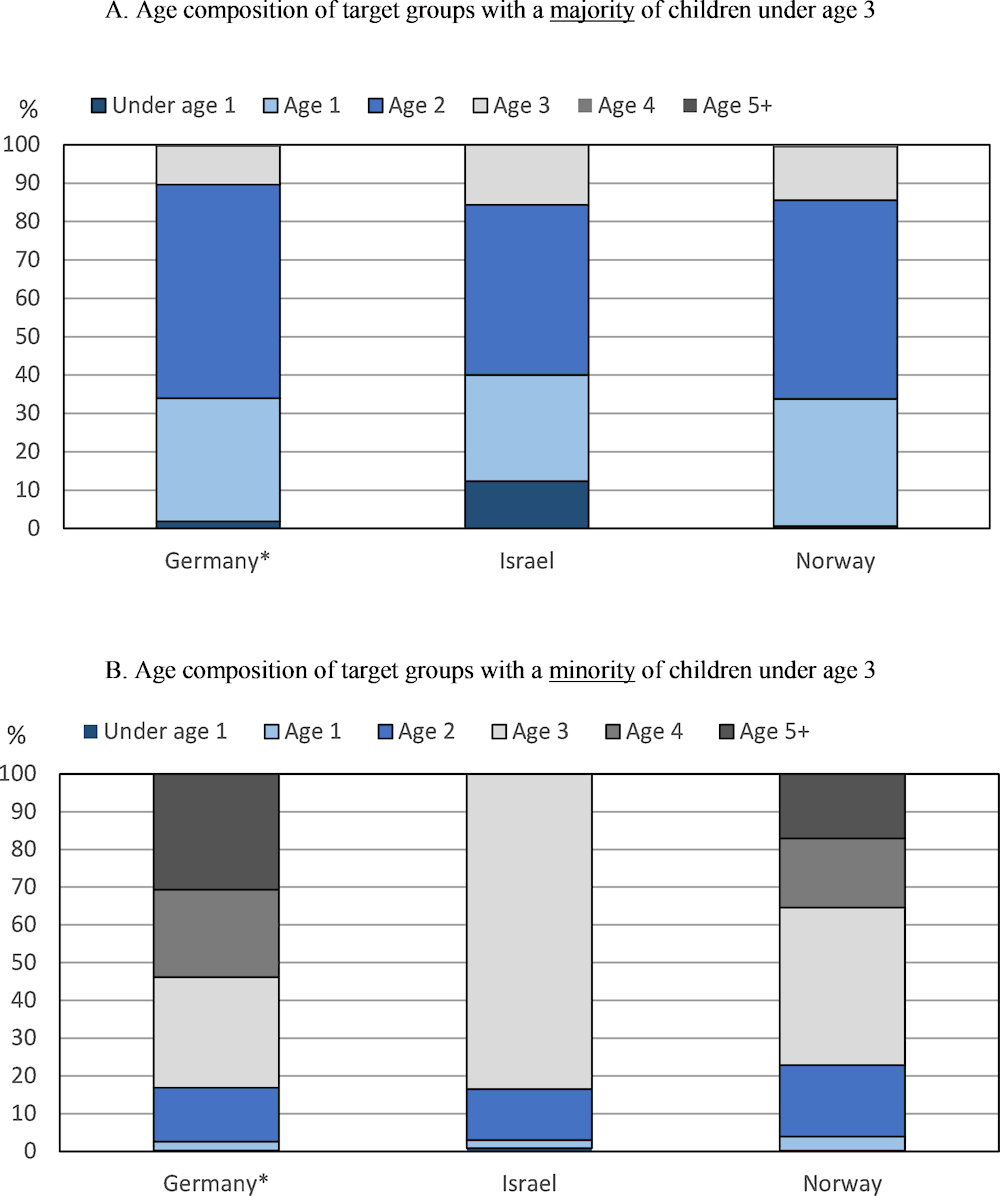

In Norway, 69% of staff surveyed report working with a target group composed of a majority of children under age 3 (this proportion is higher in Denmark, with low response rates). In Germany, where there is often a smaller proportion of children under age 3 in the centre, a majority of surveyed staff (55%) also report working with a target group composed of a majority of children under age 3. In Israel, 79% of staff report working with a target composed of a majority of children under the age of 3. These target groups have a small minority of children who are age 3 and children older than 3 are practically absent in both of these groups (Figure 3.13 A). This means that target groups with a majority of children under age 3 are actually not mixing age groups at all and serve only younger children. In these target groups, about one‑third of children are age 1 and the majority of children are age 2 (Box 3.1).

The picture is different for target groups with a minority of children under age 3 (Figure 3.13 B). In both countries, only one child out of five in these groups is under age 3, with more children who are age 2 than who are age 1. In Germany, these target groups also serve, on average, a comparable number of children ages 3, 4 or 5, while in Norway children age 3 account for 42% of all children. As these are average proportions, several types of target groups can be present in this category, in particular, target groups mixing all ages and target groups mixing children under age 3 with children who are age 3. The observed averages suggest that this latter type is more frequent in Norway than in Germany.

Figure 3.13. Age composition of the target group according to the proportion of children under age 3

* Estimates for sub-groups and estimated differences between sub-groups need to be interpreted with care. See Annex A for more information.

Source: OECD (2019[1]), TALIS Starting Strong 2018 Database, http://www.oecd.org/education/school/oecdtalisstartingstrongdata.htm.

Box 3.1. Infants in early childhood education and care settings

Infants have highly specific developmental needs and rely heavily on their caregivers to provide physical and verbal support, including through caregiving routines. Staff must be aware of and sensitive to infants’ needs and interests in their interactions (Jamison et al., 2014[5]; Chazan-Cohen et al., 2017[6]).

In Israel, the enrolment of very young children in early childhood education and care (ECEC) settings is high compared to other OECD countries (see Chapter 2). The enrolment rate in ECEC for children under age 1 is 31% in Israel, compared to 6% in Germany and 4% in Norway. Across OECD countries, only in Luxembourg has a rate similar to Israel (OECD, 2019[7]). The low share of infants enrolled in ECEC across OECD countries could be partially explained by parental leave policies. For example, in Norway, parental leave is granted for a one-year duration (OECD, 2019[8]).

There is also a high proportion of very young children in target groups (defined as the first group of children that staff worked with on their last working day before the day of the survey) in settings in Israel participating in TALIS Starting Strong. Children under age 1 comprise 12% of target groups, on average, in Israel, compared to 2% in Germany and nearly 0% in Norway. Regulations for ECEC settings in Israel group classrooms/playrooms according to three age ranges: babies, from 6 months to 15 months; young toddlers, from 16 months to 24 months; and toddlers, from 25 months to 36 months. These different age subgroups also have implications for regulations, for example with different staff-child ratios, as well as for staff practices in the groups and overall process quality.

Staff with specialised training in working with infants are critical to high process quality in ECEC. However, although infant education and care demand specific knowledge of infant development to support children’s exploration and communication, the literature suggests that staff training is usually more focused on older children. Staff and infants spend a large amount of time involved in care routines, and the literature suggests that these moments are privileged opportunities to develop respectful, reciprocal and responsive interactions. Staff should also be prepared to support group and peer processes and collaborative play, as peer social interactions involving reciprocity, joint attention and mutual affect are foundational for infants’ social development (Williams, Mastergeorge and Ontai, 2010[9]).

Staff’s characteristics

TALIS Starting Strong gives a picture of the characteristics of the ECEC workforce, including age, experience and educational attainment. This picture helps policy makers understand the strengths and weaknesses of the current ECEC workforce and what needs can be addressed through policy. It also helps plan for recruitment. For Denmark, Germany and Norway, this section distinguishes between staff working with target groups comprising a majority or a minority of children under age 3, as these countries have many integrated centres with children ranging from the age of one to five. As such, it is not possible to clearly separate staff working with children under age 3 from those also working with older children. In Israel, ECEC settings are not age-integrated and therefore only staff working with children under age 3 are described here.

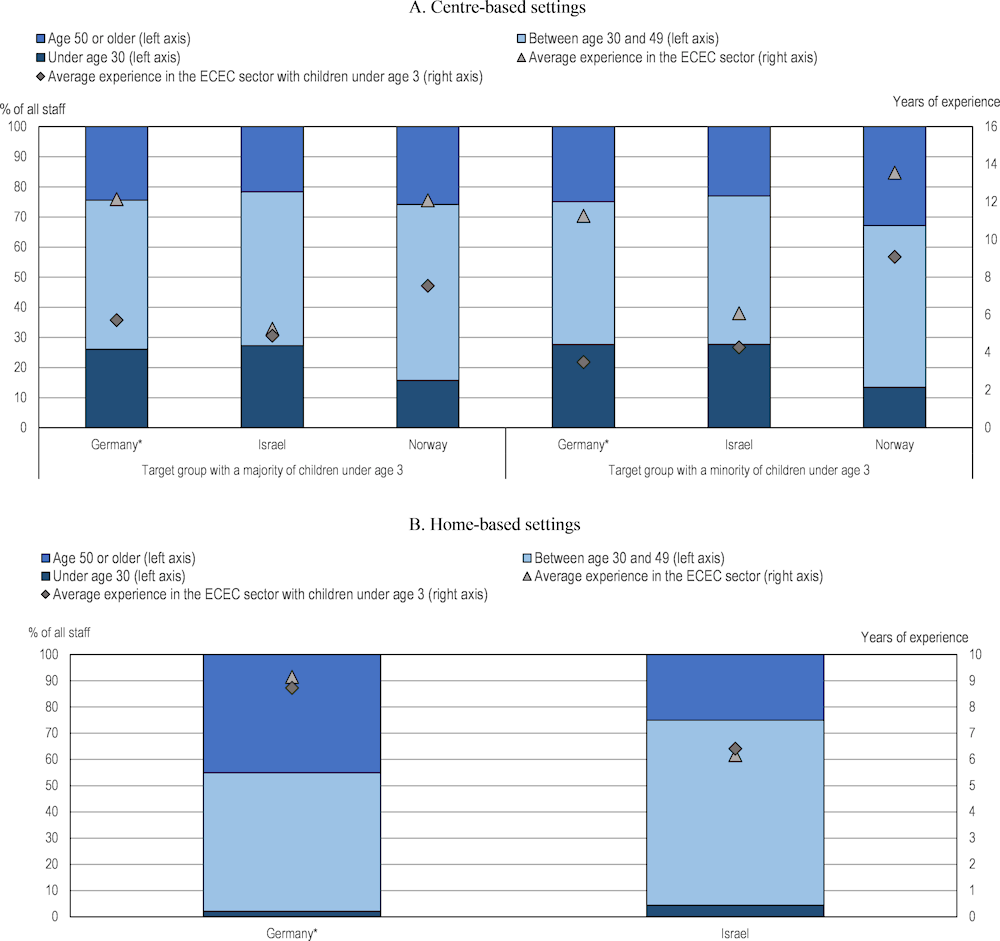

Staff’s age and experience

The age profile of the workforce in ECEC centre-based settings is similar across countries and target group age, with generally 25% of the workforce under the age of 30, 50% between the age of 25 and 49, and 25% over the age of 50 (see Figure 3.14). Centre-based settings in Norway have a somewhat older workforce (as in Denmark), with less than 15% of staff under the age of 30.

While in Germany and Norway the average number of years of experience of staff working in the ECEC sector is more than ten regardless of the age of the target group, ECEC staff in Israel are less experienced and report having worked, on average, five years in the sector (see Figure 3.14). Importantly, staff in Germany and Norway report a much fewer number of years of specific experience with children under 3 compared to their overall experience in the sector, than staff in Israel. Staff in Germany have, on average, six years of experience working with children under age 3 if they work with a target group comprising a majority of this age group. In contrast, staff have about four years of this specialised experience if they work with a target group comprising a minority of children under age 3. The gap is smaller in Norway, where average staff experience with children under age 3 is eight or nine years, depending on the age of the target group.

In all countries, data on staff’s experience reflects the recent history and growth of ECEC services for children under age 3. These ECEC services have seen considerable growth in the past ten years (see Chapter 2) that entailed important waves of recruitment, with new staff progressively gaining experience. Integrated settings offer more flexibility insofar as staff working with children from ages 3-5 can start working also with younger children, which is mirrored by the fact that staff have more experience working with children than specifically working with very young children.

Figure 3.14. Age and experience of staff in early childhood education and care settings

* Estimates for sub-groups and estimated differences between sub-groups need to be interpreted with care. See Annex A for more information.

Notes: Home-based settings serve a small number of children in Norway and were not included in the survey. In Israel, all staff working in centre-based settings work with target groups including only children under age 3.

Source: OECD (2019[1]), TALIS Starting Strong 2018 Database, http://www.oecd.org/education/school/oecdtalisstartingstrongdata.htm.

Staff’s age and average experience in German and Israeli home-based settings are different from those observed in centre-based settings. The proportion of staff under age 30 is quite small (2% in Germany and 4% in Israel) in home-based settings, and in Germany, 45% of these staff are older than 50. Home-based staff in Germany have, on average, nine years of experience, with nearly all of this experience including children under age 3. In Israel, the average number of years of experience (six years) is higher than what is observed in centre-based settings.

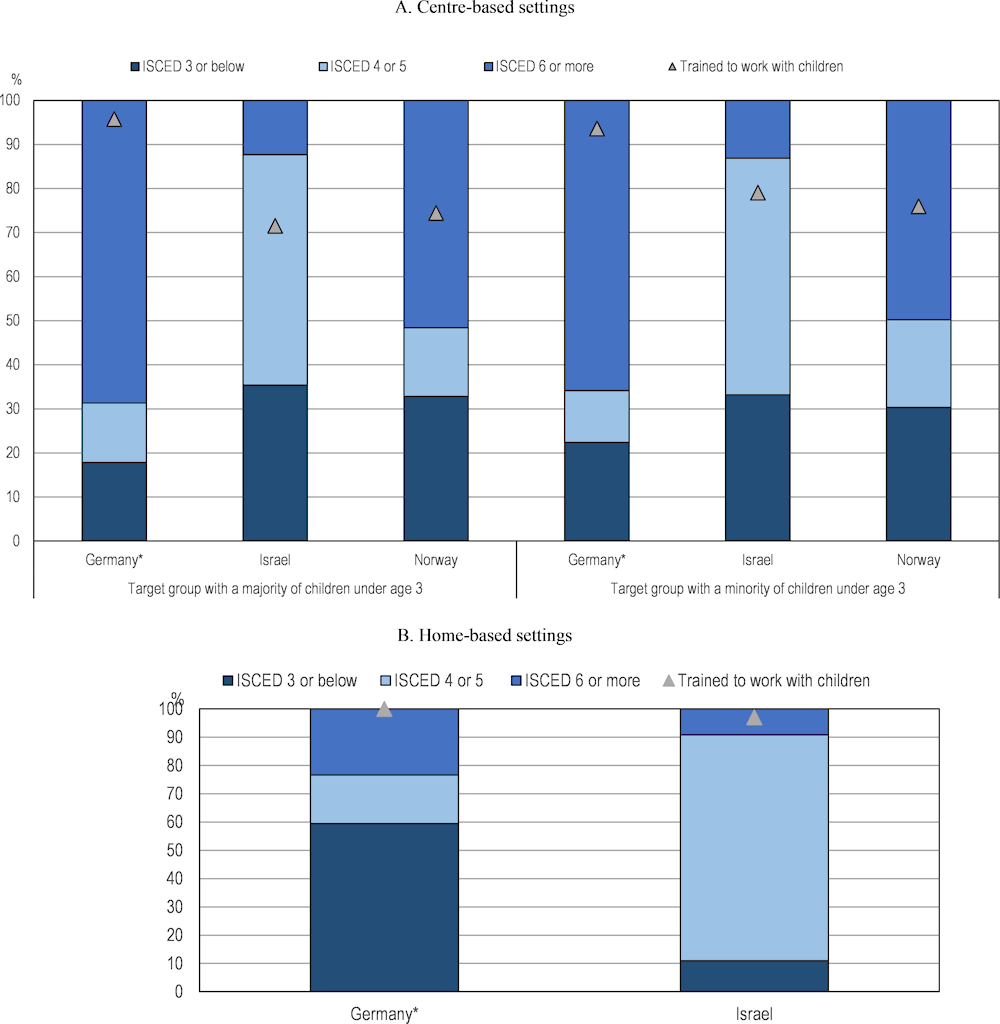

Staff’s educational attainment

Along with experience and in-service training, pre-service training is one of the main roads through which staff acquire the skills and knowledge to create high-quality environments for children’s development and well-being. All countries have educational prerequisites to enter the ECEC profession. These requirements can vary according to roles and responsibilities and may have evolved in the past years. In addition, pathways outside of formal education exist to facilitate career growth. An extensive literature shows that higher levels of educational attainment are associated with higher quality staff-child interactions (OECD, 2018[10]). More specifically, in a number of countries, including Norway, Portugal and the United States (Castle et al., 2016[11]), studies confirm the association between staff studies beyond secondary school and better interactions between these staff and children under age 3, in particular to foster language development.

In all countries, most staff have pursued education and training after secondary school (ISCED 4 and above) (Figure 3.15), with the highest percentage found in Germany. Education levels are similar for staff regardless of whether their target group includes a minority or a majority of children under age 3. Among staff who report that their target group includes a majority of children under age 3, the proportion of staff in Germany with an educational attainment at ISCED 3 level or below (17%) is much lower than it is in Israel and Norway (35% and 32%, respectively).

In Germany and Norway, more than half of all staff working in target groups with a majority of children under age 3 have at least a bachelor’s degree or equivalent (ISCED 6 or more), with a lower proportion in Norway (52%) than in Germany (67%). To the contrary, in Israel, the main post-secondary pathway to the ECEC profession is a degree equivalent to ISCED 4 or 5 (52% of all staff).

In all countries, a majority of staff report that their initial training included specific instruction to work with children, but only in Germany did nearly all staff receive such training (97% of staff in target groups with a majority of young children, 95% in target groups including only a minority of young children). In Israel and Norway, 70-75% of staff report that their initial training included such elements. In Denmark (with low response rates), the proportion is even lower, but remains above 50%. This means that most staff who did not pursue studies after secondary school still had elements covering work with children in their curriculum. Those who did not report training specifically to work with children are more likely to have stopped their initial training without a degree beyond secondary school. A greater proportion of staff in Norway (68%) than in Israel (66%) who did not report that their initial training covered working with children did not pursue studies beyond secondary school.

Staff’s educational attainment in German home-based settings is lower than it is in centre-based settings, whereas the educational attainment of these groups tends to be similar in Israel. In Germany, almost 60% of staff working in home-based settings have not pursued an education beyond secondary school. In Israel, to the contrary, 80% of home-based staff have reached ISCED 4 or 5. In both countries, almost all staff in home-based settings received training to work with children.

Figure 3.15. Educational attainment of staff working in early childhood education and care settings

* Estimates for sub-groups and estimated differences between sub-groups need to be interpreted with care. See Annex A for more information.

Notes: Home-based settings serve a small number of children in Norway and were not included in the survey.. In Israel, all staff working in centre-based settings work with a target group including only children under age 3.

Source: OECD (2019[1]), TALIS Starting Strong 2018 Database, http://www.oecd.org/education/school/oecdtalisstartingstrongdata.htm.

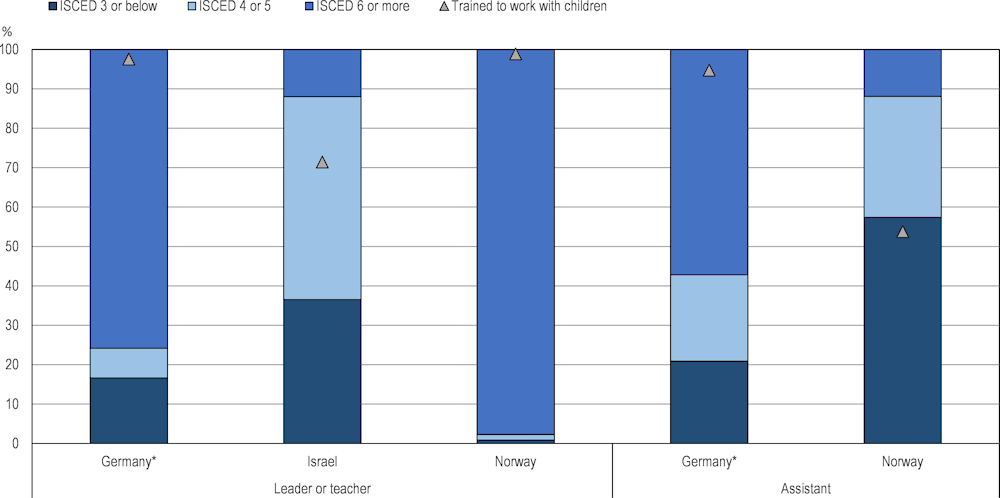

In centre-base settings, teachers generally have a higher educational attainment than assistants, in particular in Norway (Figure 3.16). In Germany, 75% of teachers have at least a bachelor’s degree or equivalent (ISCED 6 or more), compared to 57% of assistants. In both roles, the proportion of staff without a post-secondary degree is similar (17% and 21% respectively). In Norway, assistants’ and teachers’ roles are more different (Figure 3.11), and so is their educational attainment. Almost all teachers in Norway have a bachelor’s degree or equivalent (more than 97%), while 58% of assistants have not pursued studies beyond secondary school. Importantly, almost all teachers in both Germany and Norway had training related to working with children as part of their initial training.

Figure 3.16. Educational attainment and role of staff working in early childhood education and care settings

* Estimates for sub-groups and estimated differences between sub-groups need to be interpreted with care. See Annex A for more information.

Note: In Israel, the distinction between assistant and teacher does not apply.

Source: OECD (2019[1]), TALIS Starting Strong 2018 Database, http://www.oecd.org/education/school/oecdtalisstartingstrongdata.htm.

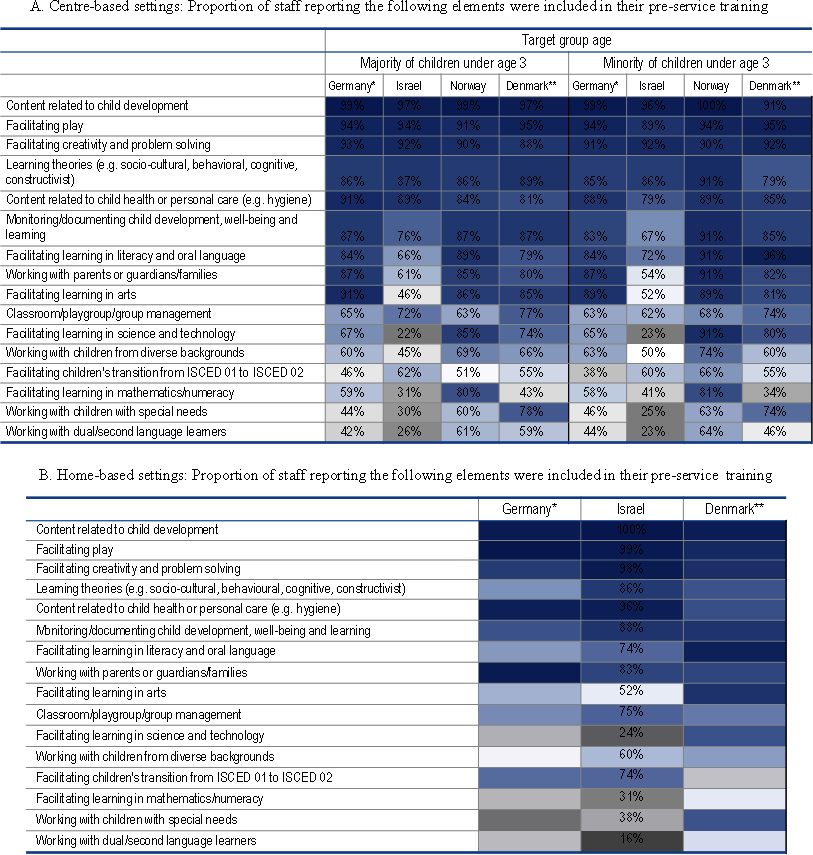

Content of pre-service training for early childhood education and care

Staff who report their formal education included training specifically to work with children were also asked about the content of this training, and generally reported a very diverse and comprehensive set of topics covered (Table 3.3). In all three countries, a selection of core topics is reported by more than 80% of those staff: child development, facilitating play, facilitating creativity and problem solving, learning theories, and child health and personal care. Training topic coverage is the broadest in Norway (and Denmark, with low response rates). The topic coverage in Germany differs only with respect to a few topics (working with children with special needs or with second-language learners, facilitating learning in mathematics), in which fewer staff report having training. In Germany and Norway, target group age is almost not related to the training content.

In Israel, the topic coverage is more limited, in particular in terms of learning areas, and much fewer staff report training that included facilitating learning in arts (46%), in science and technology (22%), or in mathematics/numeracy (31%). Importantly, 62% of staff report that transitions from ISCED 01 to ISCED 02 were covered in their initial training, on par with Norway. A relatively large percentage of staff is trained in group management.

In home-based settings, where almost all staff report they have training to work with children, topic coverage is similar to that reported by staff in centre-based settings. In Germany, with a small sample of home-based staff, the coverage is to some extent narrower, with fewer staff reporting training in topics such as learning theories, for instance. In Israel, topic coverage as part of pre-service training for staff working in home-based settings is similar to that of staff working in centre-based settings.

Table 3.3. Pre-service training content for staff in early childhood education and care

* Estimates for sub-groups and estimated differences between sub-groups need to be interpreted with care. See Annex A for more information.

** Low response rates in the survey may result in biases in the estimates reported and limit the comparability of the data.

Notes: Colours vary from dark grey (0%) to white (50%) to dark blue (100%). Home-based settings serve a small number of children in Norway and were not included in the survey. Due to the limited sample sizes, which resulted in large standard errors, only colours (no percentages) are displayed for staff working in home‑based settings in Denmark and Germany. Only staff who reported that their pre-service training included training to work specifically with children answered these questions. All elements are sorted according to the average proportion across all countries in centre-based settings. In Israel, all staff working in centre-based settings work with a target group including only children under age 3.

Source: OECD (2019[1]), TALIS Starting Strong 2018 Database, http://www.oecd.org/education/school/oecdtalisstartingstrongdata.htm.

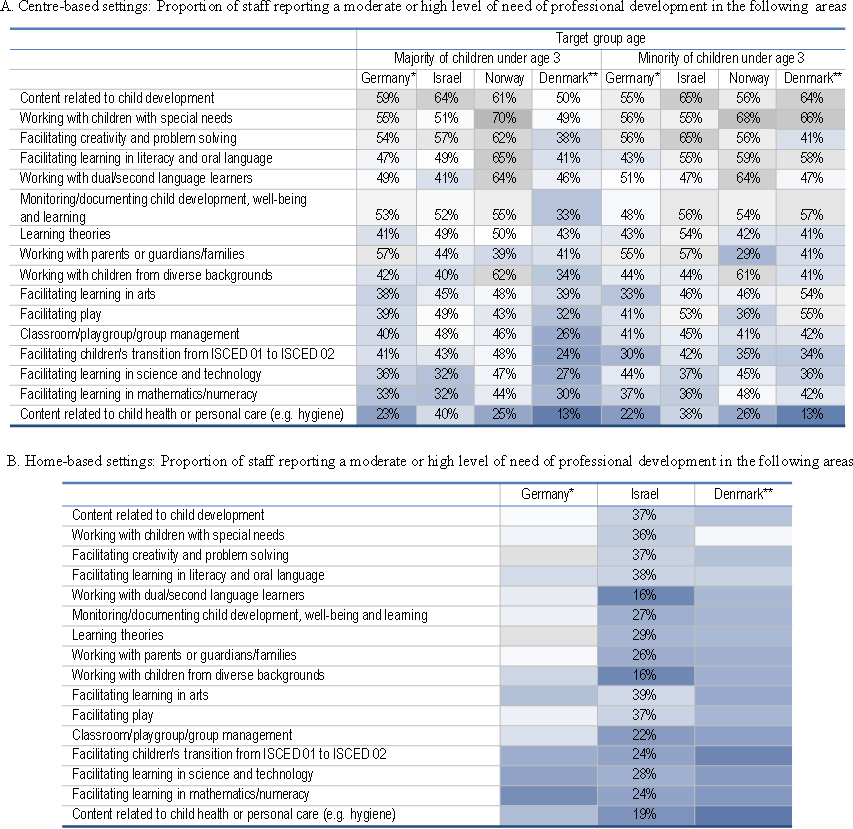

Professional development needs

TALIS Starting Strong includes a detailed module about professional development, with information on the topics that are covered as well as a self-assessment of professional development needs (Table 3.4). In service training serves several purposes. It can help staff update their knowledge and practices. It also provides the opportunity for staff to adapt their work to new technologies and new practices. Staff can also benefit from in-service training to overcome specific difficulties they encounter in the course of their work. Even though staff self-reports of these needs must be interpreted with caution, they can help policy makers better design professional development offers for ECEC services. First, reported needs in a specific topic are a means to assess the importance of the topic, but can also signal staff-specific interest. Second, staff’s reported needs are not necessarily in line with children’s needs. Third, in comparing countries, cultural differences can exist, driving the threshold beyond which a need can be considered important. In particular, the more staff are aware of the best current practices, the more likely they are to report a need.

In centre-based settings across all four countries, the areas of professional development need reported by large and small percentages of staff are generally the same. The most frequently reported needs are still not a consensus, even though the majority of staff across countries report them. In all countries, about 60% of staff reported they have at least a moderate need for professional development covering child development. Professional development linked to working with children with special educational needs is also one of the most frequently reported needs, especially in Norway. This is in line with the shortage of staff with competence in this area reported by leaders (see Table 3.1). Facilitating learning in literacy and oral language, and in creativity and problem solving are among the most frequently mentioned learning areas with needs for ongoing training. On the other hand, facilitating learning in science and technology, and in mathematics and numeracy are among the least frequently mentioned (along with child health and personal care).

Training needs reported by staff also point to some country specificities. A larger percentage of staff in Norway report that they need professional development in how to work with dual language learners or children from diverse backgrounds than in the other countries. Since staff also report high training needs to work with children with special needs, these results could point to a greater awareness of the need to address diversity. Germany is the only country in which professional development to improve work with parents and guardians is among the most reported needs (57%).

In home-based settings, a smaller percentage of staff in Israel generally report moderate or important needs, while in Germany, reports are similar to those in centre-based settings.

Table 3.4. Professional development needs of staff working in early childhood education and care

* Estimates for sub-groups and estimated differences between sub-groups need to be interpreted with care. See Annex A for more information.

** Low response rates in the survey may result in biases in the estimates reported and limit the comparability of the data.

Notes: Colours vary from dark blue (0%) to white (50%) to dark grey (100%). Home-based settings serve a small number of children in Norway and were not included in the survey. Due to the limited sample sizes, which resulted in large standard errors, only colours (no percentages) are displayed for staff working in home‑based settings in Denmark and Germany. Only staff who reported that their pre-service training included training to work specifically with children answered these questions. All elements are sorted according to the average proportion across all countries in centre-based settings. In Israel, all staff working in centre-based settings work with a target group including only children under age 3.

Source: OECD (2019[1]), TALIS Starting Strong 2018 Database, http://www.oecd.org/education/school/oecdtalisstartingstrongdata.htm.

Staff well-being

Staff well-being is important to attract and retain talents, but it can also impact the quality of the environment provided to young children in a number of ways. Low staff well-being can directly affect the quality of the work provided, by decreasing motivation, increasing absenteeism or limiting the quality of the staff’s interactions with children and parents (OECD, 2018[10]). Dissatisfied staff are less likely to stay in the profession, putting extra pressure on recruitment and damaging workforce stability. TALIS Starting Strong gives two complementary sets of information on staff well-being. Staff reports on job satisfaction present a broad view of their satisfaction with several aspects of their job, while staff reported sources of stress help to understand how the different tasks they have to perform impact their mental well-being in their daily life at work.

In all countries, staff overwhelmingly agree or strongly agree that “all in all they are satisfied with their job”, a statement that is, however, diminished by two sources of dissatisfaction: salaries and, to a lesser extent, the way the society as a whole values them (Table 3.5). In all countries (including Denmark, with low response rates), more than 94% of staff report they are all in all satisfied with their job. There is a similar consensus for the following items: they agree parents or guardians value them, that their centre is a good place to work, and they would still choose to work as an ECEC staff if they had to choose again. However, only about 30% of staff agree they are satisfied with their salaries in Germany and Norway, and an even lower proportion in Israel (16%), where they also are less satisfied with the terms of their contracts. While a majority of staff feel valued by society in Israel and Norway, less do in Germany (37%). Reports are similar from staff in German home-based settings. Compared with centre-based staff, home-based staff in Israel differ on two important points: home-based staff agree more often that they are satisfied with their salary, and likewise, that they are valued by society. This suggests a link between being satisfied with one’s salary and how staff perceive being valued by society.

Table 3.5. Job satisfaction in early childhood education and care settings

Proportion of respondents who report agreeing or strongly agreeing with the following statements concerning their job satisfaction, by type of setting

|

Centre-based settings |

Home-based settings |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Germany* |

Israel |

Norway |

Denmark** |

Germany* |

Israel |

Denmark** |

|

Staff are valued in society |

37% |

56% |

58% |

55% |

84% |

||

|

Satisfied with the salary I receive for my work |

29% |

16% |

30% |

32% |

47% |

||

|

Apart from my salary, I am satisfied with the terms of my contract |

81% |

57% |

74% |

82% |

28% |

||

|

Enjoy working at this ECEC centre |

96% |

98% |

97% |

98% |

100% |

||

|

Satisfied with the support received from parents or guardians |

81% |

91% |

97% |

91% |

93% |

||

|

I need more support from my leader |

26% |

48% |

32% |

27% |

47% |

||

|

If I could choose again, I would still choose to work as an ECEC staff |

85% |

79% |

89% |

83% |

91% |

||

|

I would recommend this centre as a good place to work |

89% |

92% |

94% |

94% |

90% |

||

|

Parents or guardians value me as an ECEC staff |

97% |

97% |

99% |

99% |

100% |

||

|

All in all, I am satisfied with my job |

94% |

96% |

97% |

95% |

100% |

||

* Estimates for sub-groups and estimated differences between sub-groups need to be interpreted with care. See Annex A for more information.

** Low response rates in the survey may result in biases in the estimates reported and limit the comparability of the data.

Notes: Colours vary from dark grey (0%) to white (50%) to dark blue (100%). Home-based settings serve a small number of children in Norway and were not included in the survey. Due to the limited sample sizes, which resulted in large standard errors, only colours (no percentages) are displayed for staff working in home‑based settings in Denmark and Germany. All elements are sorted according to the average proportion across all countries in centre-based settings.

Source: OECD (2019[1]), TALIS Starting Strong 2018 Database, http://www.oecd.org/education/school/oecdtalisstartingstrongdata.htm.

The sources of stress that staff in centres report vary generally across countries, with staff in Germany reporting a greater number of sources of stress (Table 3.6). For nearly a majority of staff in all countries, a lack of resources is perceived as a source of stress, despite the differences in resource availability presented above. However, in Israel, where resources are generally scarcer, all other sources of stress are reported less often than in the other countries. Having too many additional duties and managing classroom/playroom behaviour are frequently mentioned as sources of stress in Israel. The most frequently reported sources of stress in Germany are having extra duties due to absent staff, along with having too much work related to documenting children’s development – which is rarely reported as a source of stress in Israel and Norway. Having too many children in the classroom/playroom and having too many additional duties are also often reported as sources of stress in Germany (and in Denmark, with low response rates). In Norway, despite more staff in the centres, the most likely source of stress for staff is having too many children in the classroom/playroom. All other conditions are much less often reported as sources of stress.

Table 3.6. Sources of stress of staff working in early childhood education and care settings

Proportion of respondents who say that the following conditions are sources of stress “quite a bit” or “a lot,” by type of setting

|

|

Centre-based settings |

Home-based settings |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Germany* |

Israel |

Norway |

Denmark** |

Germany* |

Israel |

Denmark** |

|

|

Lack of resources |

53% |

56% |

48% |

66% |

32% |

|||

|

Having too many children in my classroom/playroom |

52% |

40% |

57% |

65% |

10% |

|||

|

Having extra duties due to absent staff |

68% |

30% |

50% |

66% |

8% |

|||

|

Having too many additional duties |

49% |

46% |

39% |

44% |

23% |

|||

|

Having too much work related to documenting children's development |

67% |

18% |

23% |

50% |

22% |

|||

|

Managing classroom/playroom behaviour |

33% |

50% |

23% |

39% |

41% |

|||

|

Keeping up with changing requirements from authorities |

38% |

27% |

30% |

39% |

38% |

|||

|

Being held responsible for children's development well-being and learning |

36% |

40% |

18% |

32% |

45% |

|||

|

Having too much administrative work |

42% |

6% |

26% |

50% |

12% |

|||

|

Accommodating children with special needs |

23% |

20% |

19% |

40% |

26% |

|||

|

Addressing parents’ or guardians’ concerns |

33% |

33% |

13% |

21% |

25% |

|||

|

Having too much preparation work for children’s activities |

26% |

19% |

21% |

32% |

16% |

|||

* Estimates for sub-groups and estimated differences between sub-groups need to be interpreted with care. See Annex A for more information.

** Low response rates in the survey may result in biases in the estimates reported and limit the comparability of the data.

Notes: Colours vary from dark blue (0%) to white (50%) to dark grey (100%). Home-based settings serve a small number of children in Norway and were not included in the survey. Due to the limited sample sizes, which resulted in large standard errors, only colours (no percentages) are displayed for staff working in home‑based settings in Denmark and Germany. All elements are sorted according to the average proportion across all countries in centre-based settings.

Source: OECD (2019[1]), TALIS Starting Strong 2018 Database, http://www.oecd.org/education/school/oecdtalisstartingstrongdata.htm.

Conclusion

This chapter discussed the main characteristics and structural features of ECEC settings that can support quality. Large differences exist across and within countries in the quality of the neighbourhood where ECEC centres are located, the characteristics of the children in ECEC settings (age mix, socio-economic and cultural background), and the size of centres. These factors shape the needs and challenges faced by ECEC settings to provide quality, but are difficult to affect through policies. Staff in the ECEC sector also differ greatly both across and within countries in terms of their education and training backgrounds and experience and therefore express various training needs. They also face different working conditions and sources of stress. Policies can foster quality by allocating resources to centres depending on their needs and by helping all staff work as professionals in good working environments. Attracting and maintaining a high‑quality workforce is also an important challenge in at least three of the participating countries (Denmark, Germany and Israel). This chapter points to the following policy implications:

1. Ensure initial training and professional development opportunities for staff reflect the unique needs of children in this age group and of staff depending on their situation. Staff working in the ECEC sector have different profiles and roles, but all of them need to work as professionals with children and have the appropriate skills and knowledge. Investing in high-quality initial training programmes covering the main areas of working with children is important for the next generation of staff. In addition, all staff need to benefit from training opportunities to help them develop their skills during their careers. Policies can target more particularly staff with a low education and training background, as is the case in home-based settings in some countries. As staff differ in their needs and face barriers to participate in training linked to the profession itself (e.g. no replacement if they attend training), a multiplicity of training opportunities, both in terms of format and content, should be offered. Flexible forms of training, such as learning from peers and mentoring, as well as work-based learning may have multiple advantages for staff working with young children, as these forms of training can be adapted to staff’s profiles and needs and to the barriers they face, such as lack of time or the cost of training.

2. Prepare staff to work with parents. Parents have a crucial impact on the development of very young children and ECEC settings can complement and help parents in their role. Staff in home-based settings have particularly close links with parents. Policies can strengthen the role of parents in curriculum frameworks and prepare staff through pre-service training and continuing professional development to build bridges between ECEC settings and children’s homes.

3. Raise the status of the profession and address sources of stress. Staff are very committed to the profession and to their role and most of them consider that if they could decide again, they would still choose the same job. However, only half of staff feel valued by society and, related to this, staff show a low level of satisfaction with their salary. At the same time, many countries face important challenges to attract talents to the profession. Policies to ensure that education and training help staff grow as professionals can go hand in hand with salary increases to better align staff’s skills, roles and responsibilities with their salary. This would help attract more candidates to the profession. In addition, the profession needs to be seen as providing well-being. Policies can work on alleviating some sources of stress, such as a lack of time to perform some tasks without children or too much administrative and documenting work.

References

[11] Castle, S. et al. (2016), “Teacher-child interactions in early Head Start classrooms: Associations with teacher characteristics”, Early Education and Development, Vol. 27/2, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2016.1102017.

[6] Chazan-Cohen, R. et al. (2017), Working Toward a Definition of Infant/Toddler Curricula: Intentionally Furthering the Development of Individual Children within Responsive Relationships, Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/opre/nitr_report_v09_final_b508.pdf (accessed on 8 December 2017).

[2] Coelho, V. et al. (2019), “Predictors of parent-teacher communication during infant transition to childcare in Portugal”, Early Child Development and Care, Vol. 189/13, pp. 2126-2140, https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2018.1439940.

[5] Jamison, K. et al. (2014), “CLASS-Infant: An observational measure for assessing teacher-infant interactions in center-based child care”, Early Education and Development, Vol. 25/4, pp. 553-572, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2013.822239.

[3] Leavitt, R. (1995), “Parent-provider communication in family day care homes”, Child and Youth Care Forum, Vol. 24/4, pp. 231-245, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02128590.

[7] OECD (2019), Education at a Glance 2019: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/f8d7880d-en.

[8] OECD (2019), Providing Quality Early Childhood Education and Care: Results from the Starting Strong Survey 2018, TALIS, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/301005d1-en.

[1] OECD (2019), TALIS Starting Strong 2018 Database, OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/education/school/oecdtalisstartingstrongdata.htm.

[10] OECD (2018), Engaging Young Children: Lessons from Research about Quality in Early Childhood Education and Care, Starting Strong, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264085145-en.

[4] Owen, M. et al. (2008), “Relationship-focused child care practices: Quality of care and child outcomes for children in poverty”, Early Education and Development, Vol. 19/2, pp. 302-329, https://doi.org/10.1080/10409280801964010.