This chapter explores process quality in settings serving children under age 3 using data from TALIS Starting Strong. Process quality describes how staff interact with young children and their parents and is a key aspect of a well-functioning early childhood education and care sector. This chapter investigates how much staff in Denmark, Germany, Israel and Norway engage in practices associated with different dimensions of process quality: cognitive development, socio-emotional development, engagement with parents, and group organisation and individual support. It also details how the composition of the group of children staff work with can vary across countries. The chapter concludes with an analysis of how process quality relates to different characteristics of the staff and centre.

Quality Early Childhood Education and Care for Children Under Age 3

4. Process quality in early childhood education and care settings for children under age 3

Abstract

Key messages

TALIS Starting Strong measures process quality through staff reports about their own practices and practices used more generally in their early childhood education and care (ECEC) settings. Process quality describes how staff, children and parents interact with each other, and helps to understand how ECEC settings create an environment that fosters children’s learning and well-being. According to the literature, higher process quality is associated with better cognitive and socio-emotional development of children under age 3.

Across all dimensions of process quality, staff in Israel tend to favour the most positive response option (“a lot” or “almost always”) compared with their colleagues in Denmark (with low response rates), Germany and Norway. However, the proportion of staff endorsing the two most negative response options is similar across countries. Staff in home-based settings in Israel generally report slightly higher levels of practices across all dimensions of process quality compared with their colleagues in centre-based settings.

Staff report that they and their colleagues engage regularly in practices facilitating language development. Fewer staff report so with respect to practices facilitating numeracy and literacy development. In the four participating countries, more than 20% of staff report none or very little engagement in several practices facilitating literacy and numeracy development. However, in all countries, three-quarters or more staff report that singing songs and rhymes applies “a lot” to their centres, a practice that supports literacy development.

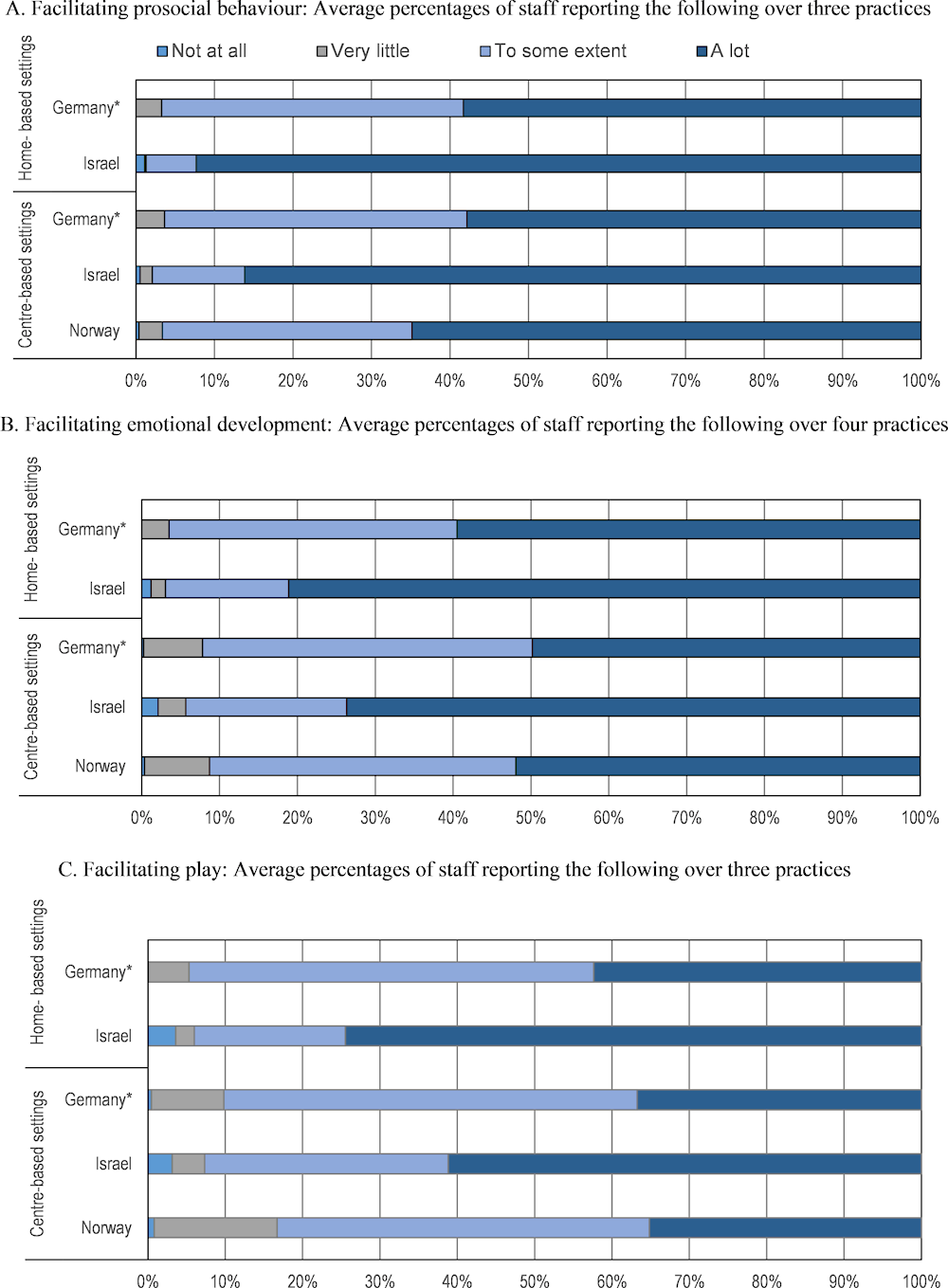

Staff across all participating countries put practices facilitating emotional development and prosocial behaviour at the core of their work with children under age 3, with more than 90% of staff reporting that these practices apply “a lot” or “to some extent” in their centre. Staff in Israel, and particularly in home-based settings, report more use of practices around facilitating play than staff in other countries.

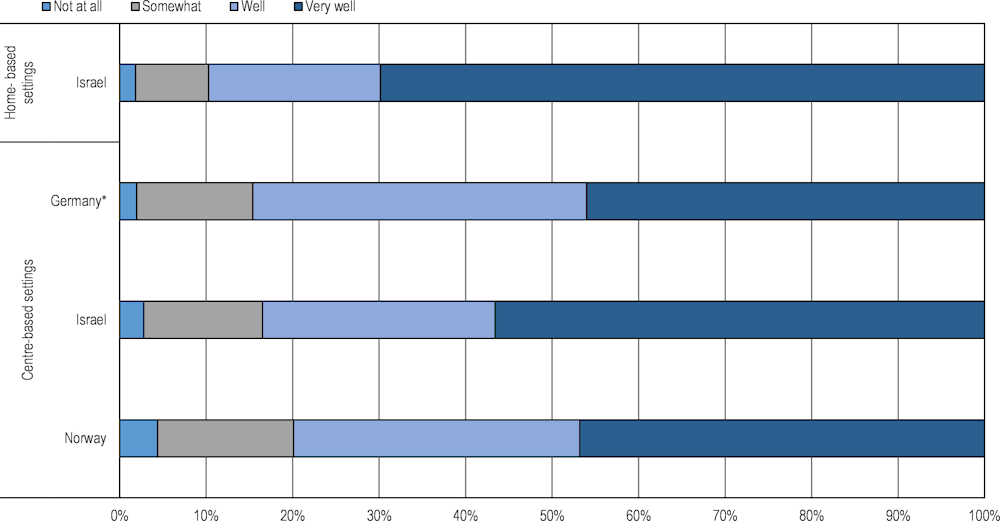

In all countries, more than half of staff report that practices facilitating communication with parents about activities with children and children’s development apply very well to their centres. However, many fewer staff report that their centre encourages parents to do learning activities with their children at home.

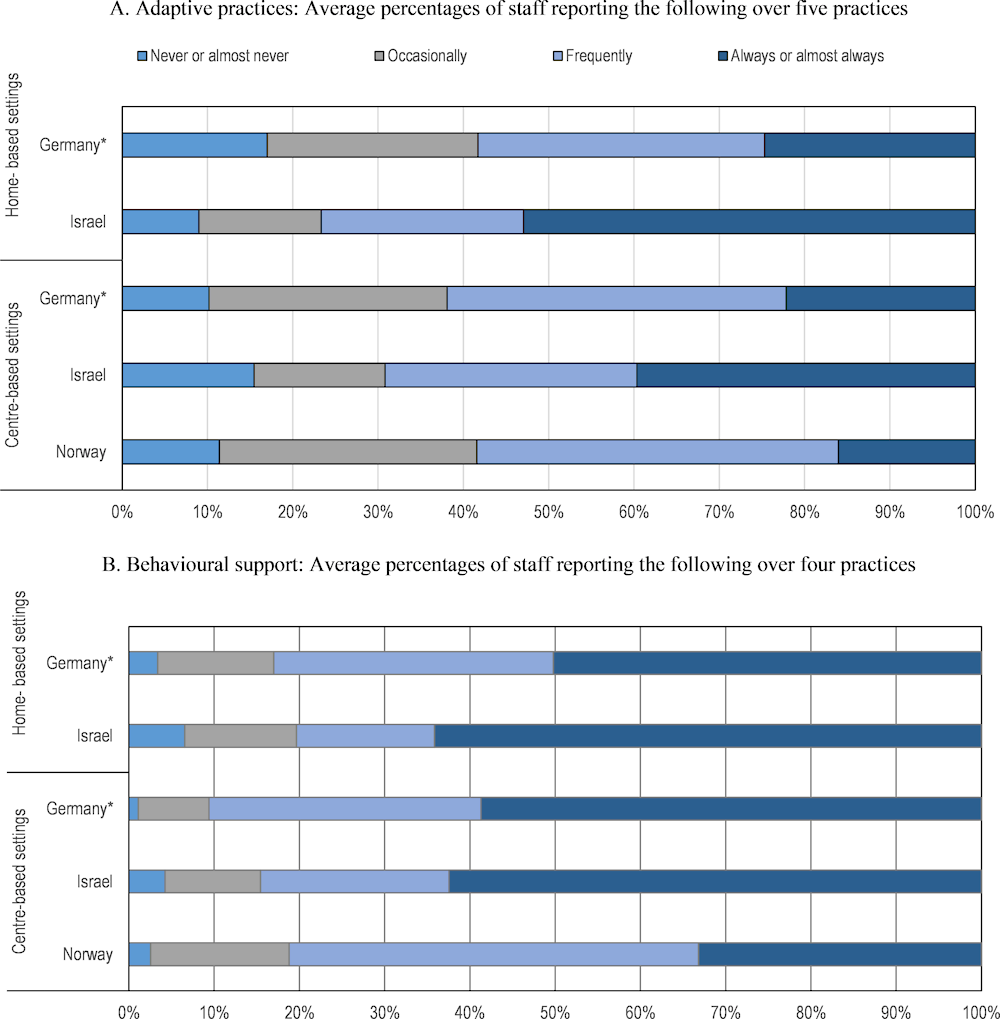

A majority of staff report engaging in practices adapted to children’s needs and interest to support their development, learning and well-being across domains. Among these adaptive practices, adapting activities to children’s level of development is quite frequent compared to other practices, such as adapting activities to differences in children's cultural background.

Staff report helping children to follow the rules and calming those who are upset more than other behavioural support practices, including helping children understand the consequences if they do not follow the rules.

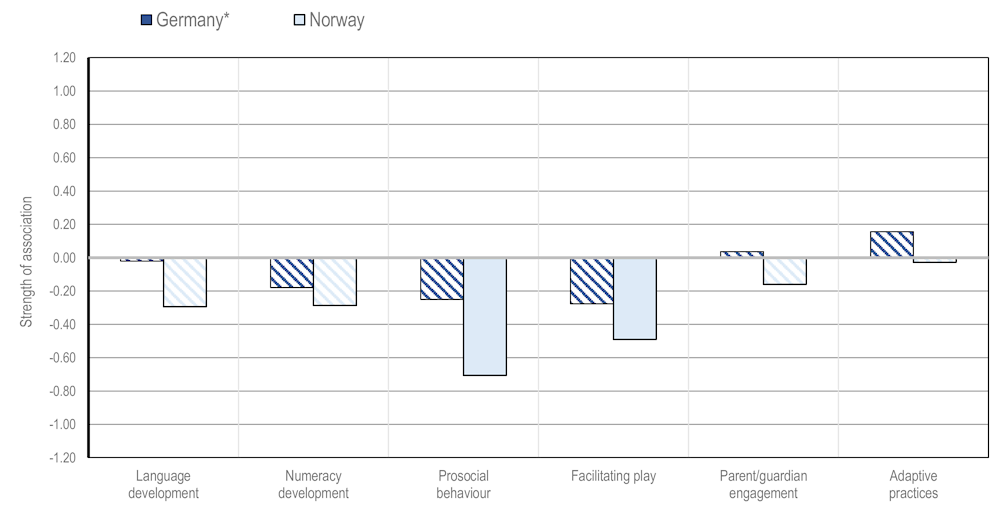

The relationship between process quality and the centre’s characteristics varies across countries. In Norway, staff working in centres with a higher proportion of children under age 3 report lower levels of engagement in practices facilitating play and prosocial behaviour. Staff in Israel working in larger centres report higher levels of engagement in numeracy development. In Norway, staff in larger centres report more practices to facilitate parent/guardian engagement. In contrast, in Germany, staff in larger centres report fewer practices to facilitate play.

Staff working in larger target groups, staff serving as teachers and staff with pre-service training that included elements specifically for working with children report higher levels of engagement in adaptive practices.

Introduction

The Starting Strong Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS Starting Strong) offers international insight on staff impressions of their daily practices to support quality in their early childhood education and care (ECEC) settings. Children’s interactions matter a lot for their development and well‑being in ECEC settings, and for fostering an early interest in exploration and learning. Interactions that form children’s daily experiences include those between ECEC staff and children, and among children in the setting as well as between staff and parents. Together, these interactions and experiences constitute process quality in ECEC. Process quality in ECEC can be facilitated through strong structural quality, particularly training and investment in the ECEC workforce (OECD, 2018[1]).

This chapter focuses on reports of different dimensions of process quality from staff working with children under age 3. Staff in both centre- and home-based settings are considered, providing comparisons between these types of settings and across participating countries (Denmark, Germany, Israel and Norway). The chapter then describes how characteristics of centres, including their size and the age mix of children, and characteristics of staff, such as level and content of pre-service training, are associated with staff reports of process quality.

Overview of process quality

Process quality describes the daily interactions children have in their ECEC settings, including with staff/teachers, space and materials, other children, their families, and the wider community. Process quality represents the dimensions of ECEC quality that are most proximal to children and most closely linked to children’s development and well-being (OECD, 2018[1]). Children under age 3 are especially reliant on relationships with others to meet their basic needs and engage with the world, making sensitive and responsive interactions with ECEC staff all the more important (Jamison et al., 2014[2]).

When staff interact with very young children in a warm and responsive manner, children have opportunities to develop in ways that allow them to become increasingly active in their environments. For example, sensitive interactions with staff support young children’s self-regulatory and language skills, which in turn shape their future interactions with adults, peers and others (Hoff, 2006[3]; Rhoades et al., 2011[4]). In ECEC settings, structured activities throughout the day provide opportunities for staff and young children to have warm, reciprocal interactions, but the routines of caring for children under age 3 (e.g. feeding, diapering) are equally important aspects of education and care in settings for this age group (Chazan-Cohen et al., 2017[5]; Guedes et al., 2020[6]; Slot et al., 2015[7]). ECEC settings are considered high quality when children experience individualised support for positive behaviour and exposure to developmental and educational activities that build on play and routines (OECD, 2019[8]; Pianta, Downer and Hamre, 2016[9]).

Process quality in ECEC settings is linked with the development and well-being of children under age 3. For example, in settings with higher quality interactions, children in this age range show better communication, problem-solving, fine motor skills, engagement, adaptive behaviours and stronger growth in emotion regulation (Araujo, Dormal and Schady, 2019[10]; Mortensen and Barnett, 2018[11]; Pinto et al., 2019[12]). Process quality in home-based settings is also positively associated with socio-emotional development and cognitive and language competence among toddlers (Colwell et al., 2013[13]; Lahti et al., 2015[14]).

Characteristics of staff, including their beliefs about what is important for young children, are associated with their pedagogical practices and the quality of the ECEC setting. For example, staff who view children’s ability to co-operate easily with others as being of high importance also report more practices to facilitate children’s prosocial behaviour and emotional development in their ECEC centres (OECD, 2019[8]). Similarly, staff’s educational background and their roles and responsibilities in the classroom/playroom matter for supporting process quality. Specifically, staff’s pre-service education is associated with higher quality language-learning environments, a better emotional climate, and more staff sensitivity in centres and home-based settings for children under age 3 (Barros et al., 2018[15]; King et al., 2016[16]; Schaack, Le and Setodji, 2017[17]; Slot et al., 2015[7]). Although pre-service education in general is important for staff working in settings with children under age 3, training specifically to work with young children is critical for process quality (Schaack, Le and Setodji, 2017[17]).

Staff within the same classroom/playroom have different levels of quality interactions with children, potentially related to staff roles (OECD, 2019[8]; Pauker et al., 2018[18]). Often, assistants engage in more tasks related to care routines compared with teachers or leaders, creating different sorts of opportunities to engage with children (Van Laere, Peeters and Vandenbroeck, 2012[19]). These divisions of labour among staff may contribute to differences in the quality that children experience, even within a single classroom/playroom.

In addition to the different staff present in the classroom/playroom, the different characteristics of children within the group can contribute to different levels of process quality. Some research suggests that having a wider age range of children in a single group may lead to lower process quality in centre-based settings, although this is not necessarily the case in home-based settings (Eckhardt and Egert, 2018[20]; Linberg et al., 2019[21]). Although the research base in this area is limited, mixed age groups in centres specifically serving children under age 3 may offer lower process quality than groups with more narrow age ranges (OECD, 2018[1]).

Similarly, characteristics of ECEC settings can shape process quality. Associations between process quality and setting-level characteristics, such as management by a public versus a private entity, may be particularly sensitive to a country’s policy context. For example, some studies have found that differences in process quality are not observed between municipal and private centres in Norway and in the People’s Republic of China (Bjørnestad and Os, 2018[22]; Hu et al., 2019[23]). Setting characteristics may also contribute to features of the classroom/playroom by contributing to the resources available. Settings located in urban areas may have greater access to educated staff compared to settings in rural areas, but stress may be higher among staff in urban settings than in rural ones (Barros et al., 2016[24]; Hu et al., 2014[25]). In addition, findings from Germany suggest that larger ECEC settings may provide lower process quality for children under age 3, perhaps related to materials being shared across classrooms/playrooms and thereby limiting their availability to children throughout the day (Linberg et al., 2019[21]).

Process quality in TALIS Starting Strong

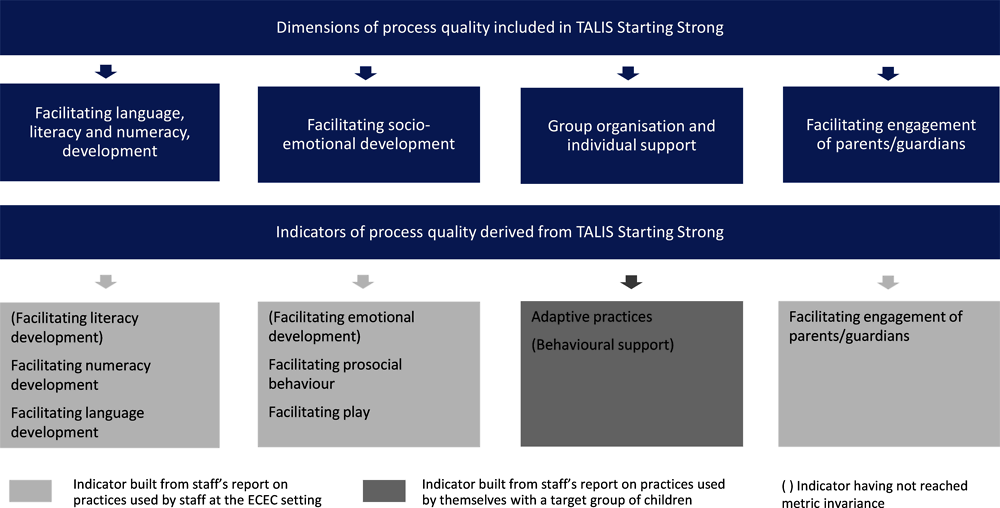

TALIS Starting Strong collects information about practices and interactions in ECEC settings along four major dimensions (Sim et al., 2019[26]) (Figure 4.1):

1. practices facilitating children’s language, literacy and numeracy development (setting level)

2. practices facilitating children’s socio-emotional development (setting level)

3. practices facilitating group organisation and individual support (group level)

4. practices facilitating the engagement of parents or guardians in the development and well-being of their children and their participation in the activities of the centre (setting level).

Figure 4.1. The different measures of process quality in TALIS Starting Strong

Note: Annex A provides further information on measurement invariance for all indicators of process quality.

These practices contribute to the quality of interactions between staff and children as well as among children. In addition, these practices shape the interactions between staff and parents, which are of paramount importance for children under age 3. Close partnerships allow staff and parents to share information about a child, promoting continuity between ECEC settings and the home and enhancing the quality of care in both settings (Coelho et al., 2019[27]; Layland and Smith, 2015[28]; Owen et al., 2008[29]).

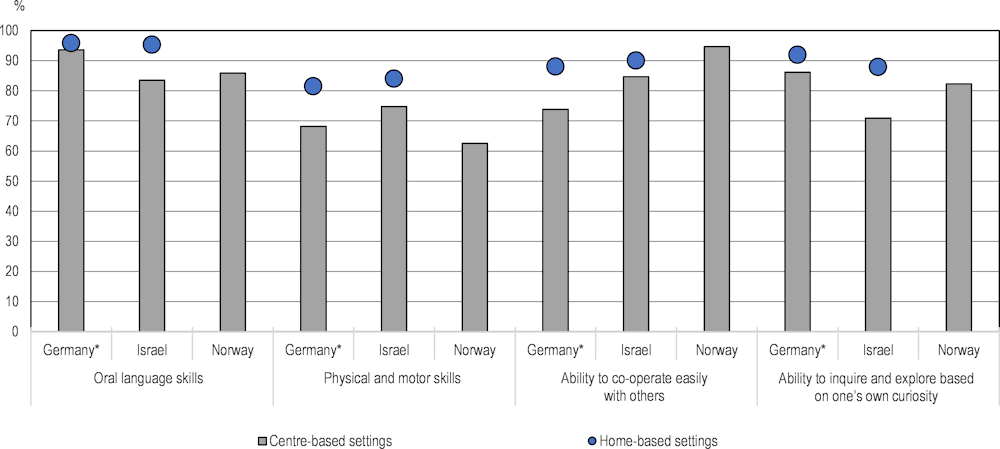

Staff participating in TALIS Starting Strong report on practices to support process quality that are used by staff at their settings (facilitating language, literacy and numeracy development; facilitating socio-emotional development; facilitating engagement of parents/guardians) and practices that they use themselves with a target group of children (group organisation and individual support). In addition, staff report on their beliefs about how important it is for their ECEC settings to develop four types of skills and abilities in children to prepare them for life in the future: 1) oral language skills; 2) physical and motor skills; 3) ability to co-operate easily with others; 4) ability to inquire and explore based on one’s own curiosity.

In general, staff across countries rate all four of the skills and abilities as being of high importance to help prepare children for life in the future (Figure 4.2). Overall, home-based staff tend to endorse the importance of these areas more strongly than centre-based staff. Helping children develop physical and motor skills is the area the fewest staff rated as of “high importance” among centre-based staff in Germany and Norway, whereas in Israel staff report more similar levels of importance across all four domains. Centre-based staff in Germany place the highest importance on developing children’s oral language skills whereas centre-based staff in Norway place the highest importance on developing children’s ability to co‑operate easily with others.

Figure 4.2. Early childhood education and care staff’s beliefs about skills and abilities that will prepare children for life in the future

* Estimates for sub-groups and estimated differences between sub-groups need to be interpreted with care. See Annex A for more information.

Source: OECD (2019[30]), TALIS Starting Strong 2018 Database, http://www.oecd.org/education/school/oecdtalisstartingstrongdata.htm.

The organisation of the target group

Staff participating in TALIS Starting Strong provide information on the composition of a target group of children, as well as the practices used to support process quality in this group. Staff provide information on the children included in this group as well on the other members of the workforce present within the group. The target group is defined as the first group of children staff worked with on their last working day before the survey. Target groups are not necessarily fixed, like in primary schools, with the same staff and the same children across the year. Moreover, for some staff, the target group may reflect a staff member’s full day of work, potentially involving a shifting number of children (e.g. some children may only be present for a half-day) as well as different staff who are present at different times. In addition, the target groups are not necessarily representative of such groups within countries because target groups were not part of the sampling design and multiple staff members could have reported on the same target group. The child and staff composition of target groups is important to provide information on the contexts of interactions that are the foundation of process quality.

Understanding staff practices in the context of target group size is also important because group size is one of the characteristics of structural quality that can support process quality: when working with small groups of children, staff may be able to interact with children in more responsive ways. Studies from several countries show that smaller group size is associated with higher process quality in both centre- and home‑based settings for children under age 3 (OECD, 2018[1]). Smaller groups may enable staff to spend more time giving children individualised attention, thereby enhancing process quality. Larger groups can mobilise more staff, though, to compensate for the higher number of children.

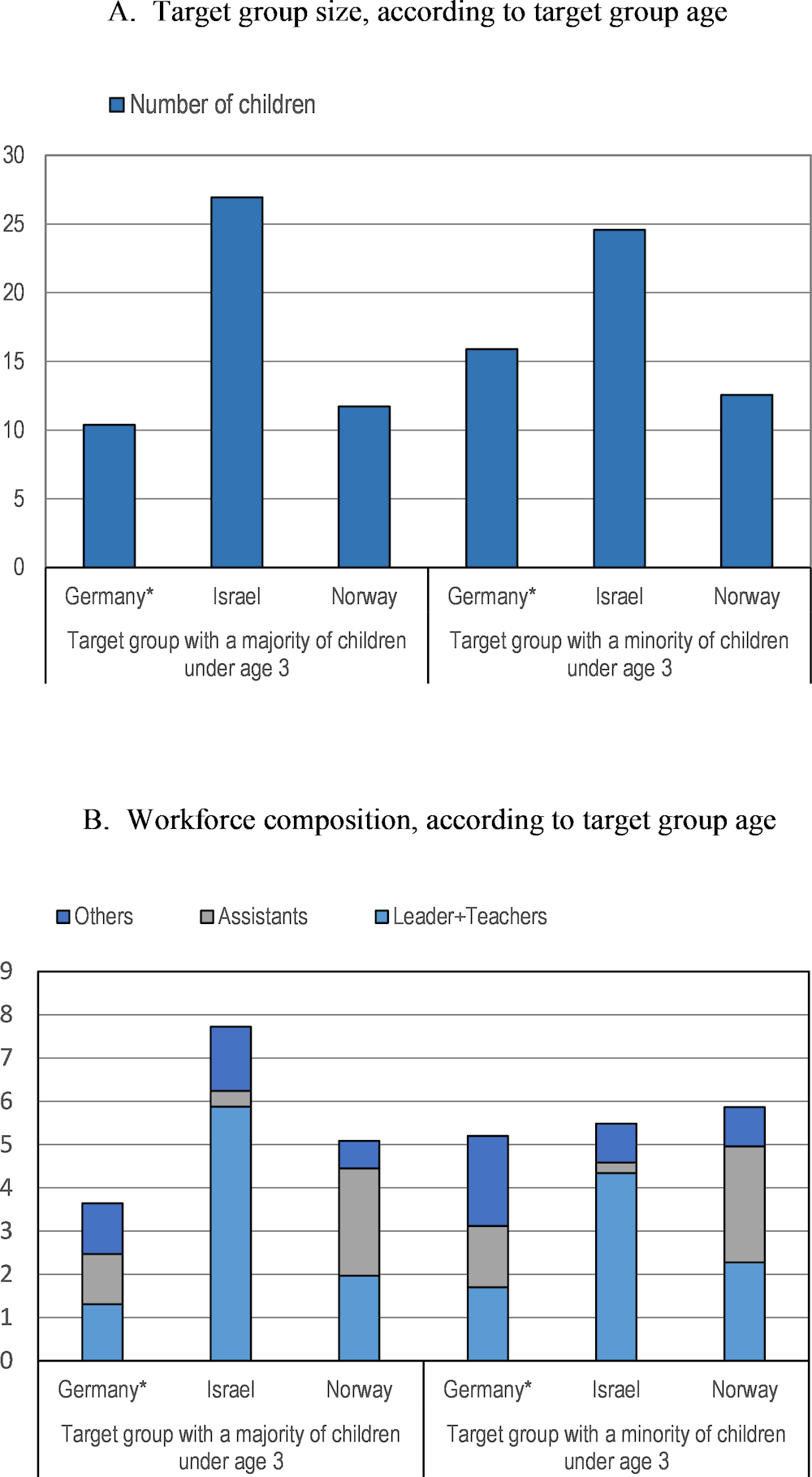

The typical size of the target group varies across countries and according to age composition (Figure 4.3 A). In Germany and Norway, target groups tend to be smaller than in Israel. In Germany (and in Denmark, with low response rates), target groups with a majority of children under age 3 are even smaller (approximately 10 children) than target groups with a minority of children in this age range (approximately 16 children in Germany and more than 20 in Denmark). In Norway, the target group size is within this range, with a smaller difference between groups that have a majority versus a minority of children under age 3. In contrast, in Israel, where target groups comprise a classroom that can be organised into smaller sub-groups, target groups include more than 24 children. The average number of staff working in the target group also varies across countries, ranging from less than four in target groups serving a majority of children under age 3 in Germany to more than seven in Israel (Figure 4.3 B).

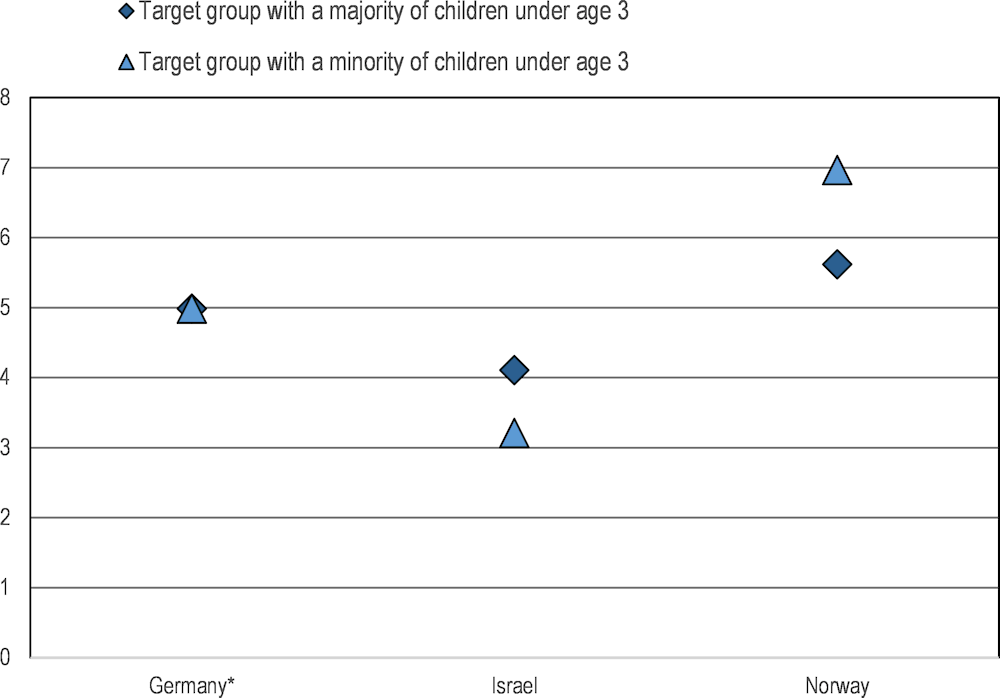

To better understand the numbers of staff and children who interact in the target groups, the number of staff per ten children is used to summarise the average number of staff (i.e. leaders, teachers, assistants or others) with whom the group of children may interact. This summary ratio is not to be confused with child-to-staff ratios used for regulatory purposes, which consider the minimum number of staff who must be present based on the number of children present. Staff reports on the target group composition in TALIS Starting Strong refer to a specific situation and are not necessarily restricted to staff and children who were all present at the same time. As a result, the number of staff per ten children in the target group cannot be interpreted as a measurement of the human resource available in the target group.

TALIS Starting Strong target groups generally comprise four staff per ten children in Israel, although this number can mask differences between different age groups even within this young age range (Figure 4.4). In Israel, distinctions are made between groups comprised of infants (15 months and younger), young toddlers (16-24 months old) and toddlers (25-36 months old), with different numbers of staff available in each of these age groups. In Germany, there are approximately five staff per ten children, irrespective of the proportion of children under age 3. In Norway, however, the number of staff per ten children is greater for target groups with a minority of children under age 3 (seven staff per ten children) compared to those with a majority of children under age 3 (five or six staff per ten children), meaning that groups with older children interact with more staff members. This finding may be related to more differentiated roles among staff (e.g. staff for special activities) or greater sharing of time across several staff members to complete tasks without children (see Chapter 3) for groups with more older than younger children. Nonetheless, in both younger and older groups in Norway, children are in contact with more staff members than they are in Germany or Israel. In Denmark (with low response rates), there are also six staff per ten children in target groups with a majority of children under age 3, but contrary to Norway, there are fewer staff (five) if the target group has a minority of children under age 3.

Figure 4.3. Target group size and staff composition in early childhood education and care settings

* Estimates for sub-groups and estimated differences between sub-groups need to be interpreted with care. See Annex A for more information.

Source: OECD (2019[30]), TALIS Starting Strong 2018 Database, http://www.oecd.org/education/school/oecdtalisstartingstrongdata.htm.

Figure 4.4. Average number of staff per ten children in the target group in early childhood education and care settings

* Estimates for sub-groups and estimated differences between sub-groups need to be interpreted with care. See Annex A for more information.

Source: OECD (2019[30]), TALIS Starting Strong 2018 Database, http://www.oecd.org/education/school/oecdtalisstartingstrongdata.htm.

Staff reports of process quality

Process quality is difficult to measure. TALIS Starting Strong investigates process quality by asking staff how much they and others in the ECEC setting engage in practices known to foster child development and well-being. These reports, though useful, need to be interpreted with caution. Because of social desirability, staff could give answers that overstate the level of process quality. Alternatively, staff who have more experience in settings providing strong process quality may be more critical of the level of quality provided by themselves and their colleagues. In order to limit these biases, for practices associated with language, literacy and numeracy development, socio-emotional development, and parental engagement, staff are asked to report not about their own behaviours, but about those of all staff in their settings. For group organisation and individual support, staff report on their own work with the target group. In addition to limitations of self-reports on process quality, cultural differences in how staff report on the practices that comprise process quality can make it challenging to compare results across countries. To address this challenge, regression analyses presented in this chapter employ scales that are constructed to facilitate cross-country comparisons in the associations between staff characteristics and process quality (OECD, 2019[31]) (see Annex B for more details).

This section covers all dimensions of process quality measured in TALIS Starting Strong following a similar method for each dimension (see Figure 4.1). A graph aggregating practices through a single indicator associated with each dimension is presented first to provide a broad account of the dimension, covering all possible response options. Although it does not distinguish individual practices within each dimension of process quality, this presentation allows cautious comparisons between countries and, more importantly, across home-based and centre-based settings. The graphs also show the extent to which staff report not engaging in these aspects of process quality and how staff in some countries favour more positive responses. The graphs are followed by tables that give further details of the specific practices used by staff, focusing on the percentage of staff who report that each practice is used “a lot”.

Facilitating language, literacy and numeracy development in early childhood education and care settings

TALIS Starting Strong includes three dimensions of ways that staff working with children under age 3 can facilitate cognitive development: 1) language; 2) literacy; and 3) numeracy (see Figure 4.1). Early language skills set the foundation for children’s learning across many different domains of education, including helping children build socio-emotional competence through their communication with others. ECEC staff can facilitate children’s language development through practices such as encouraging children to talk to one another or rephrasing statements to make sure children have understood. The specific practices associated with facilitating literacy and numeracy in TALIS Starting Strong are tailored to the types of activities staff may engage in with children under age 3. They include things such as singing songs or playing games with letters or numbers.

Practices associated with language development are widely shared across countries and settings (Figure 4.5) and staff report practices in line with their beliefs about the high importance of this area of development (see Figure 4.2). Approximately nine out of ten staff report that in their settings, staff engage “to some extent” or “a lot” in the four practices associated with language development. Staff in home-based settings tend to report these practices more frequently than staff in the same countries working in centre‑based settings. Very few staff report settings that do not engage at all in any of these practices.

Practices associated with literacy and numeracy development are widespread, but reported less extensively than those related to language development (Figure 4.5). However, this does not necessarily imply that staff attach less importance to these aspects of development: staff may engage in practices to support literacy and numeracy less often throughout the day and yet still have a meaningful impact with these practices. Contrary to language development, a small but notable proportion of staff report that practices to support literacy and numeracy development are “not at all” used in their settings, in particular in Israel. Similar patterns in use of practices to support language development more often than those to support literacy and numeracy development are also observed with staff working at the pre-primary level (OECD, 2019[8]).

Compared to Germany and Israel, staff in Norway generally report less frequent use of practices across all three dimensions of process quality facilitating aspects of cognitive development. This could be due to different response styles or a difference in practices. Moreover, compared with Israel and in some cases Germany, staff in Norway less often report that some practices “do not apply at all” in their centres, indicating that staff in Norway may prefer the middle response categories rather than simply using practices to support process quality less often than their colleagues in other countries.

Figure 4.5. Facilitating language, literacy and numeracy development in early childhood education and care settings

* Estimates for sub-groups and estimated differences between sub-groups need to be interpreted with care. See Annex A for more information.

Note: Practices considered for each area of process quality are shown in Table 4.1.

Source: OECD (2019[30]), TALIS Starting Strong 2018 Database, http://www.oecd.org/education/school/oecdtalisstartingstrongdata.htm.

Turning to the specific practices used to support language development, staff report that all four practices associated with this dimension are widely applied in their settings (Table 4.1). For each of these four practices, half or more of staff in Denmark (with low response rates), Germany and Israel report they apply “a lot” to staff in their settings. Importantly, all of these practices describe ways in which staff communicate with children, rather than specific activities. These behaviours can occur frequently throughout the day, including during more specific types of activities, and this might explain why staff consider that these statements apply “a lot”.

Table 4.1. Practices facilitating language, literacy and numeracy development in early childhood education and care settings

Percentage of respondents reporting that the following statements apply a lot to staff, by type of setting

|

|

Centre-based settings |

Home-based settings |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Germany* |

Israel |

Norway |

Denmark** |

Germany* |

Israel |

Denmark** |

|

Facilitating language |

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Encourage children to talk to each other |

67% |

64% |

47% |

74% |

88% |

||

|

Position themselves at the children's height when talking or listening |

56% |

71% |

36% |

64% |

87% |

||

|

Rephrase or recite statements to make sure children have been understood |

49% |

56% |

35% |

61% |

77% |

||

|

Model the correct word rather than correcting the child directly |

60% |

58% |

48% |

75% |

83% |

||

|

Facilitating numeracy development |

|||||||

|

Use sorting activities by shape or colour |

35% |

56% |

18% |

14% |

73% |

||

|

Play number games |

23% |

19% |

13% |

12% |

16% |

||

|

Sing songs about numbers |

19% |

39% |

19% |

29% |

55% |

||

|

Help children to use numbers or to count |

38% |

50% |

36% |

42% |

58% |

||

|

Refer to groups of objects by the size of the group |

41% |

58% |

22% |

23% |

73% |

||

|

Facilitating literacy development |

|||||||

|

Play word games with the children |

36% |

41% |

20% |

38% |

56% |

||

|

Play with letters with the children |

9% |

19% |

16% |

22% |

28% |

||

|

Sing songs or rhymes with children |

77% |

88% |

74% |

94% |

97% |

||

* Estimates for sub-groups and estimated differences between sub-groups need to be interpreted with care. See Annex A for more information.

** Low response rates in the survey may result in bias in the estimates reported and limit comparability of the data.

Notes: Colours vary from dark grey (0%) to white (50%) to dark blue (100%). Home-based settings serve a small number of children in Norway and were not included in the survey. Due to the limited sample sizes, which resulted in large standard errors, only colours (no percentages) are displayed for staff working in home‑based settings in Denmark and Germany.

Source: OECD (2019[30]), TALIS Starting Strong 2018 Database, http://www.oecd.org/education/school/oecdtalisstartingstrongdata.htm.

Staff across countries do not prioritise the same practices for facilitating numeracy development. In Israel, staff most frequently report “using sorting activities by shape or colour” and “referring to groups of objects by the size of the group”. Staff in Germany also report using these practices more than some of the other practices, but staff in Denmark (with low response rates) and Norway more frequently report they “help children to use numbers or to count”, rather than the practices favoured in Israel. In Denmark (with low response rates), Israel and Norway, staff report that “play number games” does not apply as much as the four other practices. In Germany, singing songs about numbers is reported to apply less than the other practices facilitating numeracy.

Staff overwhelmingly favour “singing songs or rhymes with children” than the other practices facilitating literacy development. In all countries, including Norway, at least three-quarters of staff report this practice applies “a lot” in their settings. “Playing word games”, and even more so “playing with letters”, are not extensively used. However, as emphasised in Figure 4.5, few staff report these practices not being used at all.

Facilitating socio-emotional development in early childhood education and care settings

Facilitating socio-emotional development covers three aspects in TALIS Starting Strong: 1) prosocial behaviour; 2) emotional development; and 3) play. For many children, ECEC settings, whether home-based or centre-based, offer their first opportunities to interact with adults and children outside of their families and to establish their own relationships with these staff and peers. Practices associated with socio-emotional development help children make these first social relationships meaningful and enriching.

As with language development, staff reports of practices facilitating prosocial behaviour are in line with their beliefs of the importance of this area (see Figure 4.2). Staff across all settings apply practices facilitating prosocial behaviour broadly (Figure 4.6). In all four participating countries, on average, more than 95% of staff report that these practices apply to staff in their settings “to some extent” or “a lot”. This is all the more true in Israel, where over 80% of staff report these practices apply “a lot”, in home-based and centre-based settings.

The engagement of staff working with children under age 3 in practices facilitating emotional development is also very high across all countries. Few staff report that the four practices proposed as facilitating emotional development do not apply in their settings. Practices associated with facilitating play follow the same pattern, with a very high level of engagement reported by staff in all settings.

Figure 4.6. Facilitating socio-emotional development in early childhood education and care settings

* Estimates for sub-groups and estimated differences between sub-groups need to be interpreted with care. See Annex A for more information.

Note: Practices considered for each area of process quality are shown in Table 4.2.

Source: OECD (2019[30]), TALIS Starting Strong 2018 Database, http://www.oecd.org/education/school/oecdtalisstartingstrongdata.htm.

Staff are somewhat more likely to report practices facilitating prosocial behaviour, such as encouraging children if they comfort each other, apply “a lot”, than practices around facilitating emotional development, like helping children to talk about what makes them sad, but the variations are not large (Table 4.2). In Denmark (with low response rates) and Israel, staff are even more likely to report that these practices apply “a lot” to staff in their centres compared with other countries.

In all four countries, fewer staff report that practices around facilitating play apply “a lot” than practices facilitating prosocial behaviour and emotional development. However, the comparison across countries is similar for all three aspects of facilitating socio-emotional development: for every practice around facilitating play, staff in Denmark (with low response rates) and Israel tend to report that the practices apply more than their colleagues in Germany and Norway, and in particular around showing enjoyment when joining in children’s play.

Table 4.2. Practices facilitating socio-emotional development in early childhood education and care settings

Percentage of respondents reporting the following statements apply a lot to staff, by type of setting

|

|

Centre-based settings |

Home-based settings |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Germany* |

Israel |

Norway |

Denmark** |

Germany* |

Israel |

Denmark** |

|

Facilitating prosocial behaviour |

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Encourage sharing amongst children |

49% |

84% |

63% |

70% |

90% |

||

|

Encourage children to help each other |

63% |

87% |

64% |

89% |

94% |

||

|

Encourage children if they comfort each other |

61% |

88% |

67% |

62% |

93% |

||

|

Facilitating emotional development |

|||||||

|

Hug the children |

59% |

89% |

59% |

89% |

90% |

||

|

Talk with children about feelings |

53% |

73% |

56% |

82% |

80% |

||

|

Help children to talk about what makes them happy |

43% |

74% |

51% |

72% |

87% |

||

|

Help children to talk about what make them sad |

44% |

58% |

42% |

76% |

68% |

||

|

Facilitating play |

|||||||

|

If invited, join in with the children's play |

37% |

45% |

29% |

45% |

66% |

||

|

When staff play with children, the children are allowed to take the lead |

23% |

67% |

37% |

38% |

73% |

||

|

Staff show enjoyment when joining the children's play |

50% |

71% |

40% |

79% |

85% |

||

* Estimates for sub-groups and estimated differences between sub-groups need to be interpreted with care. See Annex A for more information.

** Low response rates in the survey may result in bias in the estimates reported and limit comparability of the data.

Notes: Colours vary from dark grey (0%) to white (50%) to dark blue (100%). Home-based settings serve a small number of children in Norway and were not included in the survey. Due to the limited sample sizes, which resulted in large standard errors, only colours (no percentages) are displayed for staff working in home-based settings in Denmark and Germany.

Source: OECD (2019[30]), TALIS Starting Strong 2018 Database, http://www.oecd.org/education/school/oecdtalisstartingstrongdata.htm.

Group organisation and individual support to children in the target group

While practices facilitating language, literacy and numeracy development, and socio-emotional development target specific learning areas for young children, staff working in ECEC settings also have to make sure that these activities are carried out in good conditions and benefit all children. TALIS Starting Strong considers two different aspects of how staff manage group organisation and provide children with individual support in the classroom/playroom. First, adaptive practices describe how staff organise the activities they do with children, including how activities are adapted to children’s needs. Second, behavioural support covers the practices staff use to ensure children’s behaviours are supportive to learning, development and well-being in the classroom/playroom. Staff report on both of these aspects of process quality with respect to their own work with the target group.

In all countries, staff tend to adopt adaptive practices in their work with the target group (Figure 4.7). In centre-based settings, about 60% of staff in Germany and Norway report that, on average, they engage with these practices at least frequently, with the proportion of staff reporting they do so always or almost always close to 20%. In Israel, staff report more often that they engage in these practices always or almost always (40%), but comparatively fewer staff report frequent engagement and these two answers, once combined, give a proportion only slightly higher than that in Germany and Norway (70%). Staff in home-based settings give similar answers in Germany, but in Israel home-based staff report greater use of adaptive practices than their colleagues in centre-based settings. Importantly, in all countries and settings, some staff report never engaging in these practices.

Staff broadly engage in all practices providing behavioural support to children. In contrast to the dimensions of process quality previously explored, in centre-based settings, staff in Germany report applying these practices as much as staff do in Israel. In both countries, 60% of staff report engaging in these practices with children in their target group “always or almost always”, more so than staff in Norway (more than 30%). However, once staff who report that they engage “frequently” are taken into account as well, reports in all three countries are similar, with 80-90% of staff reporting one of these answers, on average. Fewer staff in home-based settings in Germany report using behavioural support practices “always or almost always”, but the proportion of home-based staff who engage in these practices at least frequently is similar to centre-based settings in both Germany and Israel.

Figure 4.7. Adaptive practices and behavioural support in early childhood education and care settings

* Estimates for sub-groups and estimated differences between sub-groups need to be interpreted with care. See Annex A for more information.

Source: OECD (2019[30]), TALIS Starting Strong 2018 Database, http://www.oecd.org/education/school/oecdtalisstartingstrongdata.htm.

Staff do not engage with the same intensity in all adaptive practices. Giving different activities to suit different children’s development or interests are the most common practices within each country (Table 4.3). Variation in the frequency of these and other less common adaptive practices depends on the country, with staff in Israel tending to report such practices more often. However, a similarly small proportion of staff across countries report “always or almost always” adapting activities to differences in children’s cultural background, meaning such practices are not common in settings for children under age 3 in the participating countries. Notably, the use of adaptive practices “always or almost always” is higher in home-based settings in Israel than in centre-based settings, highlighting the ways in which staff working with a small group of children may be able to tailor the education and care provided for each child.

Turning to specific practices to provide behavioural support, with the exception of Norway, a majority of staff report they engage “always or almost always” in helping children to follow the rules and in calming children who are upset. The other two practices are less frequently reported. Nonetheless, close to a majority of staff in Germany and Israel report that they “always or almost always” help children to understand the consequences if they do not follow the rules, and that they “always or almost always” ask children to quiet down once an activity begins. Although staff in Norway report less that they “always or almost always” engage in these activities, they tend to rather report that they engage “frequently” in them (Figure 4.7).

Table 4.3. Practices facilitating group organisation and individual support in early childhood education and care settings

Percentage of respondents reporting they engage in the following activity always or almost always, by type of setting

|

|

Centre-based settings |

Home-based settings |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Germany* |

Israel |

Norway |

Denmark** |

Germany* |

Israel |

Denmark** |

|

Adaptive practices |

|||||||

|

I set daily goals for the children |

15% |

46% |

14% |

23% |

56% |

||

|

I explain how a new activity relates to children's lives |

10% |

35% |

6% |

7% |

43% |

||

|

I give different activities to suit different children's interests |

35% |

50% |

28% |

29% |

73% |

||

|

I give different activities to suit different children's level of development |

42% |

53% |

27% |

53% |

79% |

||

|

I adapt my activities to differences in children's cultural background |

9% |

15% |

6% |

8% |

27% |

||

|

Behavioural support |

|||||||

|

I help children to follow the rules |

70% |

75% |

38% |

50% |

76% |

||

|

I calm children who are upset |

74% |

79% |

50% |

82% |

91% |

||

|

When the activities begin, I ask children to quiet down |

49% |

51% |

19% |

37% |

47% |

||

|

I help children understand the consequences if they do not follow the rules |

41% |

44% |

26% |

24% |

43% |

||

* Estimates for sub-groups and estimated differences between sub-groups need to be interpreted with care. See Annex A for more information.

** Low response rates in the survey may result in bias in the estimates reported and limit comparability of the data.

Notes: Colours vary from dark grey (0%) to white (50%) to dark blue (100%). Home-based settings serve a small number of children in Norway and were not included in the survey. In Israel, all staff working in centre-based settings work with a target group including only children under age 3. Due to limited sample sizes, which resulted in large standard errors, only colours (no percentages) are displayed for staff working in home-based settings in Denmark and Germany.

Source: OECD (2019[30]), TALIS Starting Strong 2018 Database, http://www.oecd.org/education/school/oecdtalisstartingstrongdata.htm.

Facilitating the engagement of parents and guardians in early childhood education and care settings

Parents are children’s first educators and caregivers. It is important for children’s development that staff and parents collaborate in building an enriching and consistent environment. Across all countries, a majority of staff report good engagement of staff with parents in their settings (Figure 4.8). On average across the four practices describing engagement with parents, about 50% of centre-based staff report that these apply “very well” to their settings. This proportion rises to more than 80% once staff reporting that the practices apply “well” in addition to “very well”. This is true across all countries and concerns home-based settings as well.

Figure 4.8. Facilitating the engagement of parents and guardians in early childhood education and care settings

* Estimates for sub-groups and estimated differences between sub-groups need to be interpreted with care. See Annex A for more information.

Notes: Four items are included in the average. Germany is not included among home-based settings because two practices were excluded from the questionnaire.

Source: OECD (2019[30]), TALIS Starting Strong 2018 Database, http://www.oecd.org/education/school/oecdtalisstartingstrongdata.htm.

Across all countries, staff report that parents and guardians can get in touch with staff easily. Informing parents about their children and daily activities is also seen as describing the ECEC settings “very well” in most cases. However, many fewer staff think that their settings encourage parents to play and do learning activities with their children at home (Table 4.4). Staff reports in home-based settings are similar, as are findings for pre-primary staff (OECD, 2019[8]).

Table 4.4. Practices to facilitate the engagement of parents and guardians in early childhood education and care settings

Percentage of staff reporting these statements describe how they engage with parents very well, by type of setting

|

|

Centre-based settings |

Home-based settings |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Germany* |

Israel |

Norway |

Denmark** |

Germany* |

Israel |

Denmark** |

|

Parents/guardians can get in touch with the staff easily |

69% |

69% |

74% |

87% |

1 |

86% |

|

|

Parents/guardians are informed about the development well-being and learning of their children on a regular basis |

56% |

65% |

49% |

59% |

75% |

||

|

Parents/guardians are informed about daily activities on a regular basis |

44% |

57% |

52% |

73% |

64% |

||

|

Parents/guardians are encouraged by staff to play and do learning activities with their children at home |

15% |

36% |

12% |

20% |

1 |

54% |

|

* Estimates for sub-groups and estimated differences between sub-groups need to be interpreted with care. See Annex A for more information.

** Low response rates in the survey may result in bias in the estimates reported and limit comparability of the data.

1. The question was not administered in Germany because it was optional.

Note: Colours vary from dark grey (0%) to white (50%) to dark blue (100%). Home-based settings serve a small number of children in Norway and were not included in the survey. Due to limited sample sizes, which resulted in large standard errors, only colours (no percentages) are displayed for staff working in home‑based settings in Denmark and Germany.

Source: OECD (2019[30]), TALIS Starting Strong 2018 Database, http://www.oecd.org/education/school/oecdtalisstartingstrongdata.htm

The association between target group and staff characteristics and process quality

Staff reports of process quality in their centres and in their target groups are shaped by many different factors. Regression analysis allows an examination of how many of these factors that are measured in TALIS Starting Strong contribute to process quality both within and across countries. This section describes how characteristics of centres are associated with six indicators of process quality: 1) facilitating language development; 2) facilitating numeracy development; 3) facilitating prosocial behaviour; 4) facilitating play; 5) facilitating the engagement of parents/guardians; and 6) adaptive practices. In addition, characteristics of staff and their target groups are examined in association with the use of adaptive practices in the target groups. The results described in this section are associations between the characteristics of the centre, staff and target group and process quality after accounting for other relevant characteristics measured in TALIS Starting Strong. This analytic approach allows an examination of variability in process quality within countries, as well as comparisons across countries (see Annex B for further details on the regression models and Annex C for complete regression results).

Centre characteristics and process quality

Characteristics of ECEC centres are important for understanding process quality. For example, the age mix of children in the centre, its size or the type of governance (public versus private) all have implications for the practices used by staff. Notably, associations between centre characteristics and the aspects of process quality measured in TALIS Starting Strong are often specific to individual countries.

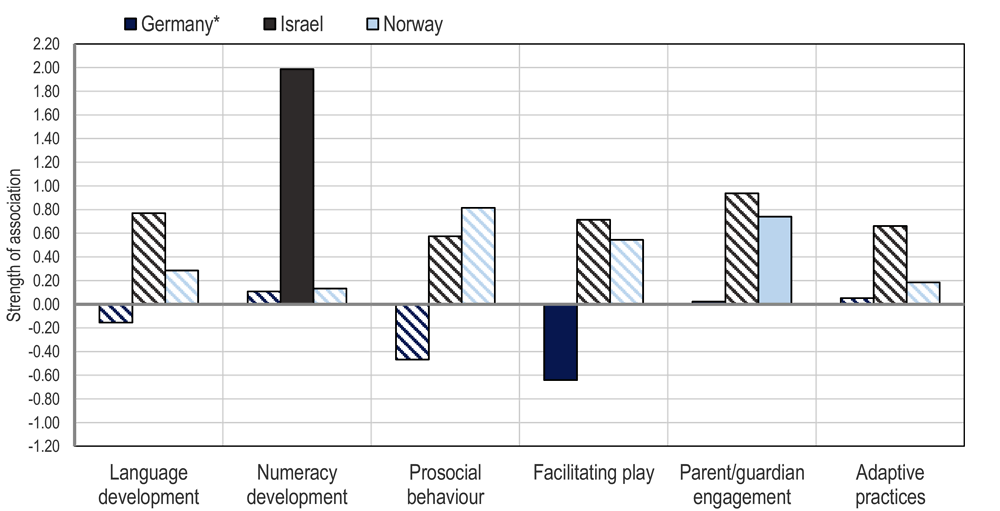

In Denmark, Germany and Norway, it is possible to compare centres that serve a larger proportion of children under age 3 (more than 30%) to centres serving a smaller proportion of children in this age range (see Chapter 3). As Figure 4.9 shows, staff generally report using fewer practices associated with process quality in centres with more children under age 3. However, this pattern is only statistically significant in Norway, where staff report using fewer practices to facilitate prosocial behaviour and play in centres with a larger proportion of children under age 3 compared to centres with fewer children under age 3. This finding suggests that staff in Norway may see more opportunities to facilitate socio-emotional development in centres with children who are slightly older.

Figure 4.9. Strength of association between process quality and age composition in early childhood education and care centres

* Estimates for sub-groups and estimated differences between sub-groups need to be interpreted with care. See Annex A for more information.

Notes: Coefficients from the OLS regression of the indicators of process quality on centre age composition. Other variables in the regression include: age composition of the target group; staff experience; role in the target group; contractual status; number of children in the centre (quartiles); number of staff per child in the centre (quartiles); percentage of children from socio-economically disadvantaged homes in the centre; centre urban/rural location; and public/private management. See Annex B for more details on variables included in the regression model. Statistically significant coefficients are marked in a darker shade (see Annex B). Israel is not included in the graph because all early childhood education and care settings included are non-integrated.

Source: OECD (2019[30]), TALIS Starting Strong 2018 Database, http://www.oecd.org/education/school/oecdtalisstartingstrongdata.htm.

TALIS Starting Strong also allows a comparison of process quality dimensions based on the concentration of children from socio-economically disadvantaged homes in the centre. However, there are no significant differences in the reports of process quality among staff in centres with more than 10% of children from socio-economically disadvantaged homes compared to staff in centres with a smaller concentration of children from socio-economically disadvantaged homes (see Annex C for the full regressions results).

The size of centres (in terms of the number of children) and the number of staff per ten children in the centres are also relevant for process quality, as these matter for the resources that are available (see Chapter 3). With regard to centre size, staff in larger centres in Israel report more use of practices facilitating numeracy development, whereas staff in larger centres in Norway report more use of practices to facilitate parent/guardian engagement (Figure 4.10). Similarly, in Norway, where there are more staff per ten children in the centre, staff report more practices facilitating language development in their centres; results for other countries are not statistically significant. In Israel and Norway, larger centres and to some extent more staff per ten children may enable staff to access resources, such as materials, specific protocols or additional staff time, that support process quality. In contrast, in Germany, staff in larger centres report less use of practices facilitating play. Staff in larger centres in Denmark (with low response rates) also report less use of practices to support process quality. In these countries, having more children in the centre may limit the resources (e.g. time, materials) available to staff to engage in practices that support process quality. Larger centres may also take different approaches than smaller centres in terms of the culture and priorities, potentially de-emphasising activities like staff engagement in children’s play.

Figure 4.10. Strength of association between process quality and centre size

* Estimates for sub-groups and estimated differences between sub-groups need to be interpreted with care. See Annex A for more information.

Notes: Coefficients from the OLS regression of the indicators of process quality on centre size. Quarters refer to 25% of early childhood education and care (ECEC) centres in a country. The bottom quarter refers to the 25% of ECEC centres within a country that register the lowest number of children, while the top quarter refers to the 25% of centres within a country that register the highest number of children. Other variables in the regression include: age composition of the target group; staff experience; role in the target group; contractual status; age composition of children in the centre; number of staff per child in the centre (quartiles); percentage of children from socio-economically disadvantaged homes in the centre; centre urban/rural location; and public/private management. See Annex B for more details on variables included in the regression model. Statistically significant coefficients are marked in a darker shade (see Annex B).

Source: OECD (2019[30]), TALIS Starting Strong 2018 Database, http://www.oecd.org/education/school/oecdtalisstartingstrongdata.htm.

In Norway, staff in centres located in cities of 15 000 inhabitants or more report more use of practices to facilitate prosocial behaviour and play than their colleagues in more rural areas (see Annex C for the full regressions results). These findings suggest that centres in more urban areas in Norway may have strategies in place to promote use of practices facilitating socio-emotional development among their staff.

In Germany, staff working in centres that are publicly managed report more use of practices to facilitate numeracy development compared to staff in centres that are privately managed (see Annex C for the full regressions results). In contrast, in Denmark (with low response rates) staff in publicly managed centres report less use of practices in several dimensions of process quality. These findings indicate that centres in Denmark and Germany may have different priorities around practices to support process quality depending on the management structure in place. Staff in publicly managed centres in Norway and Israel do not report significantly different practices compared to their colleagues in privately managed centres in any dimension of process quality.

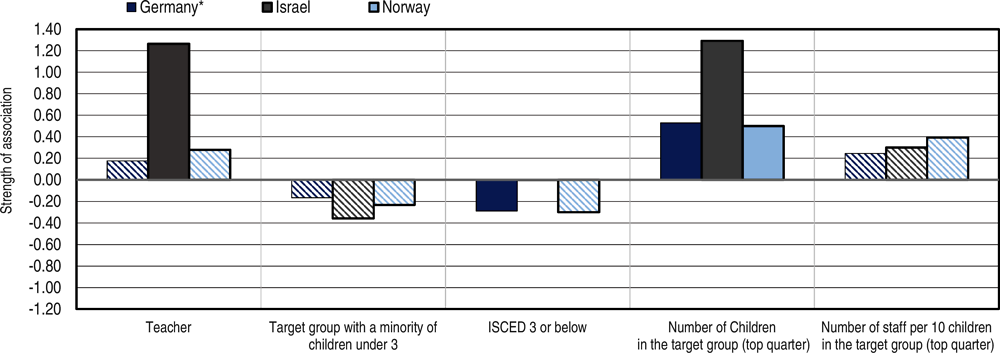

Staff and target group characteristics and use of adaptive practices

Staff report on their own use of adaptive practices in the target group, allowing an examination of this dimension of process quality as it relates to characteristics of staff and the target group. The level of engagement staff report in adaptive practices depends on their own characteristics, in particular in Israel (Figure 4.11). In Israel (in Denmark as well, with low response rates), staff with a teacher role (compared to other roles in the ECEC setting), report greater use of adaptive practices. The items that comprise adaptive practices indicate that staff choose the activities they do with children, which is consistent with teachers having more responsibilities in the target group. In contrast to the other countries where assistants are key members of the ECEC workforce, centres in Israel do not have assistants. This may help explain why teachers’ roles are notably distinct from other staff in target groups in Israel.

Initial training and educational attainment are also linked with the use of adaptive practices (Figure 4.11). In Germany, staff who did not pursue education beyond high school report a lower engagement in adaptive practices, while staff in Israel who report that their pre-service training included elements to work with children report much higher engagement. Importantly, although not all coefficients are significant, the direction of each relationship is the same in Germany, Israel and Norway. These findings suggest that adaptive practices are shaped by staff characteristics in a way that is consistent across countries.

The use of adaptive practices is linked to a greater extent to the number of children in the target group than to the number of staff per ten children (Figure 4.11). In Germany, Israel and Norway (but not in Denmark, with low response rates), staff working in a target group in the top quarter of the number of children report using adaptive practices more often than their colleagues. The number of staff per ten children has a positive association with the use of adaptive practices, but coefficients are not significant. These findings suggest that larger target groups require, or allow, staff to do more specific activities to meet the needs of individual children, possibly creating flexible sub-groups of children within the target group.

Figure 4.11. Strength of association between staff use of adaptive practices and characteristics of staff and of the target group

* Estimates for sub-groups and estimated differences between sub-groups need to be interpreted with care. See Annex A for more information.

Notes: Coefficients from the OLS regression of the indicator of process quality “adaptive practices” on teacher role, age composition of the target group, training to work with children, educational attainment, number of children in the target group (quarters) and number of staff per ten children in the target group (quarters). Other variables in the regression for the adjusted coefficients include: experience; contractual status; percentage of children from socio-economically disadvantaged homes in the target group; centre urban/rural location; and public/private management. See Annex B for more details on the variables included in the regression model. Statistically significant coefficients are marked in a darker shade (see Annex B). Teachers are compared to assistants in Germany and Norway, but are compared to “other” staff in Israel, where early childhood education and care settings do not typically include assistants.

Source: OECD (2019[30]), TALIS Starting Strong 2018 Database, http://www.oecd.org/education/school/oecdtalisstartingstrongdata.htm.

Conclusion and policy implications

This chapter presented findings from TALIS Starting Strong on the practices staff report using in settings for children under age 3 as well as the organisation of groups within these settings and staff beliefs about the skills and abilities that are important for ECEC settings to help children develop. Large percentages of staff in all four participating countries report that most practices included in the survey are widely used in their settings. However, specific practices to facilitate literacy and numeracy development are less widespread than practices to facilitate language and socio-emotional development. These reports are consistent with staff beliefs about the importance of helping children develop oral language and social skills and may reflect the importance of helping children learn to communicate and adapt to group settings before focusing on additional learning areas.

Together, the findings from this chapter suggest several areas where policy can support staff in settings for children under age 3 to foster learning, development and well-being for all children:

Better engaging parents. Very young children benefit from strong partnerships between their parents/guardians and ECEC staff. TALIS Starting Strong results show that there is room to deepen and expand the ways in which ECEC staff communicate with and support parents of children under age 3. Policy implications include strengthening the role of parents in curriculum frameworks and preparing staff through pre-service training and continuing professional development to build bridges between ECEC settings and children’s homes. In addition, campaigns to inform parents about the importance of development during the first years of life can encourage families to engage more closely with ECEC staff.

Ensure adequate resources across ECEC settings. In Israel and Norway, staff working in larger centres (those with more children) report more practices to support aspects of children’s development; the opposite is true in Denmark (with low response rates) and Germany. Although different policy responses are needed for these different contexts, governments should ensure that quality is supported regardless of centre size. In Israel and Norway, this can involve helping smaller settings to access materials and resources, including sufficient staff time and ongoing professional development for current staff, to help promote practices around quality. In Denmark and Germany, larger centres may need support to ensure that all classrooms/playrooms within the setting have sufficient materials and resources to help staff engage in high-quality interactions with all children throughout the day.

Prepare staff to individualise practices to support children’s development. Staff in all four countries report regularly adapting practices to children’s individual needs. However, practices around connecting activities to children’s lives and adapting activities to children’s cultural backgrounds are less common than practices around adapting to individual children’s interest and level of development. This could reflect a willingness to treat all children equally or a lack of preparation to adapt practices in these ways. As findings show that staff’s educational background contributes to greater use of adaptive practices, training and professional development can be enhanced to help staff integrate more adaptive practices in their work, particularly related to children’s daily life and cultural backgrounds. A greater focus on these specific types of adaptive practices can also serve as a way to engage more closely with families.

References

[10] Araujo, M., M. Dormal and N. Schady (2019), “Childcare quality and child development”, The Journal of Human Resources, Vol. 54/3, pp. 656-682, http://dx.doi.org/10.3368/jhr.54.3.0217.8572R1.

[24] Barros, S. et al. (2016), “Infant child care quality in Portugal: Associations with structural characteristics”, Early Childhood Research Quarterly, Vol. 37, pp. 118-130, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2016.05.003.

[15] Barros, S. et al. (2018), “The quality of caregiver-child interactions in infant classrooms in Portugal: The role of caregiver education”, Research Papers in Education, Vol. 33/4, pp. 427-451, https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2017.1353676.

[22] Bjørnestad, E. and E. Os (2018), “Quality in Norwegian childcare for toddlers using ITERS-R”, European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, Vol. 26/1, pp. 111-127, https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2018.1412051.

[5] Chazan-Cohen, R. et al. (2017), “Working toward a definition of infant/toddler curricula: Intentionally furthering the development of individual children within responsive relationships”, OPRE Report #2017-15, Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/opre/nitr_report_v09_final_b508.pdf (accessed on 8 December 2017).

[27] Coelho, V. et al. (2019), “Predictors of parent-teacher communication during infant transition to childcare in Portugal”, Early Child Development and Care, Vol. 189/13, pp. 2126-2140, https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2018.1439940.

[13] Colwell, N. et al. (2013), “New evidence on the validity of the Arnett Caregiver Interaction Scale: Results from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study-Birth Cohort”, Early Childhood Research Quarterly, Vol. 28/2, pp. 218-233, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2012.12.004.

[20] Eckhardt, A. and F. Egert (2018), “Process quality for children under three years in early child care and family child care in Germany”, Early Years, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2018.1438373.

[6] Guedes, C. et al. (2020), “Activity settings in toddler classrooms and quality of group and individual interactions”, Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, Vol. 67, pp. 100-110, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2019.101100.

[3] Hoff, E. (2006), “How social contexts support and shape language development”, Developmental Review, Vol. 26/1, pp. 55-88, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2005.11.002.

[23] Hu, B. et al. (2019), “Global quality profiles in Chinese early care classrooms: Evidence from the Shandong Province”, Children and Youth Services Review, Vol. 101, pp. 157-164, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.03.056.

[25] Hu, B. et al. (2014), “Examining program quality disparities between urban and rural kindergartens in China: Evidence from Zhejiang”, Journal of Research in Childhood Education, Vol. 28/4, pp. 461-483, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02568543.2014.944720.

[2] Jamison, K. et al. (2014), “CLASS-Infant: An observational measure for assessing teacher-infant interactions in center-based child care”, Early Education and Development, Vol. 25/4, pp. 553-572, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2013.822239.

[16] King, E. et al. (2016), “Classroom quality in infant and toddler classrooms: Impact of age and programme type”, Early Child Development and Care, Vol. 186/11, pp. 1821-1835, https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2015.1134521.

[14] Lahti, M. et al. (2015), “Approaches to validating child care quality rating and improvement systems (QRIS): Results from two states with similar QRIS type designs”, Early Childhood Research Quarterly, Vol. 30/B, pp. 280-290, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2014.04.005.

[28] Layland, J. and A. Smith (2015), “Quality in home-based child care for under-two-year old children in Aotearoa New Zealand: Conceptualising quality from stakeholder perspectives”, New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, Vol. 50/2, pp. 269-284, http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s40841-015-0019-7.

[21] Linberg, A. et al. (2019), “Quality of toddler childcare: Can it be assessed with questionnaires?”, Early Child Development and Care, Vol. 189/8, pp. 1369-1383, https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2017.1380636.

[11] Mortensen, J. and M. Barnett (2018), “Emotion regulation, harsh parenting, and teacher sensitivity among socioeconomically disadvantaged toddlers in child care”, Early Education and Development, Vol. 29/2, pp. 143-160, https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2017.1371560.

[8] OECD (2019), Providing Quality Early Childhood Education and Care: Results from the Starting Strong Survey 2018, TALIS, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/301005d1-en.

[30] OECD (2019), TALIS Starting Strong 2018 Database, OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/education/school/oecdtalisstartingstrongdata.htm.

[31] OECD (2019), TALIS Starting Strong 2018 Technical Report, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/education/talis/TALIS-Starting-Strong-2018-Technical-Report.pdf.

[1] OECD (2018), Engaging Young Children: Lessons from Research about Quality in Early Childhood Education and Care, Starting Strong, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264085145-en.

[29] Owen, M. et al. (2008), “Relationship-focused child care practices: Quality of care and child outcomes for children in poverty”, Early Education and Development, Vol. 19/2, pp. 302-329, https://doi.org/10.1080/10409280801964010.

[18] Pauker, S. et al. (2018), “Caregiver cognitive sensitivity: Measure development and validation in early childhood education and care (ECEC) settings”, Early Childhood Research Quarterly, Vol. 45, pp. 45-57, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2018.05.001.

[9] Pianta, R., J. Downer and B. Hamre (2016), “Quality in early education classrooms: Definitions, gaps, and systems”, The Future of Children, Vol. 26/2, pp. 119-138, https://futureofchildren.princeton.edu/sites/futureofchildren/files/resource-links/starting_early_26_2_full_journal.pdf.

[12] Pinto, A. et al. (2019), “Quality of infant child care and early infant development in Portuguese childcare centers”, Early Childhood Research Quarterly, Vol. 48/3, pp. 246-255, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2019.04.003.

[4] Rhoades, B. et al. (2011), “Demographic and familial predictors of early executive function development: Contribution of a person-centered perspective”, Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, Vol. 108/3, pp. 638-662, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2010.08.004.

[17] Schaack, D., V. Le and C. Setodji (2017), “Home-based child care provider education and specialized training: Associations with caregiving quality and toddler social-emotional and cognitive outcomes”, Early Education & Development, Vol. 28/6, pp. 655-668, https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2017.1321927.

[26] Sim, M. et al. (2019), “Starting Strong Teaching and Learning International Survey 2018 conceptual framework”, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 197, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/106b1c42-en.

[7] Slot, P. et al. (2015), “Associations between structural quality aspects and process quality in Dutch early childhood education and care settings”, Early Childhood Research Quarterly, Vol. 33, pp. 64-76, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2015.06.001.

[19] Van Laere, K., J. Peeters and M. Vandenbroeck (2012), “The education and care divide: The role of the early childhood workforce in 15 European countries”, European Journal of Education, Vol. 47/4, pp. 527-541, https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12006.