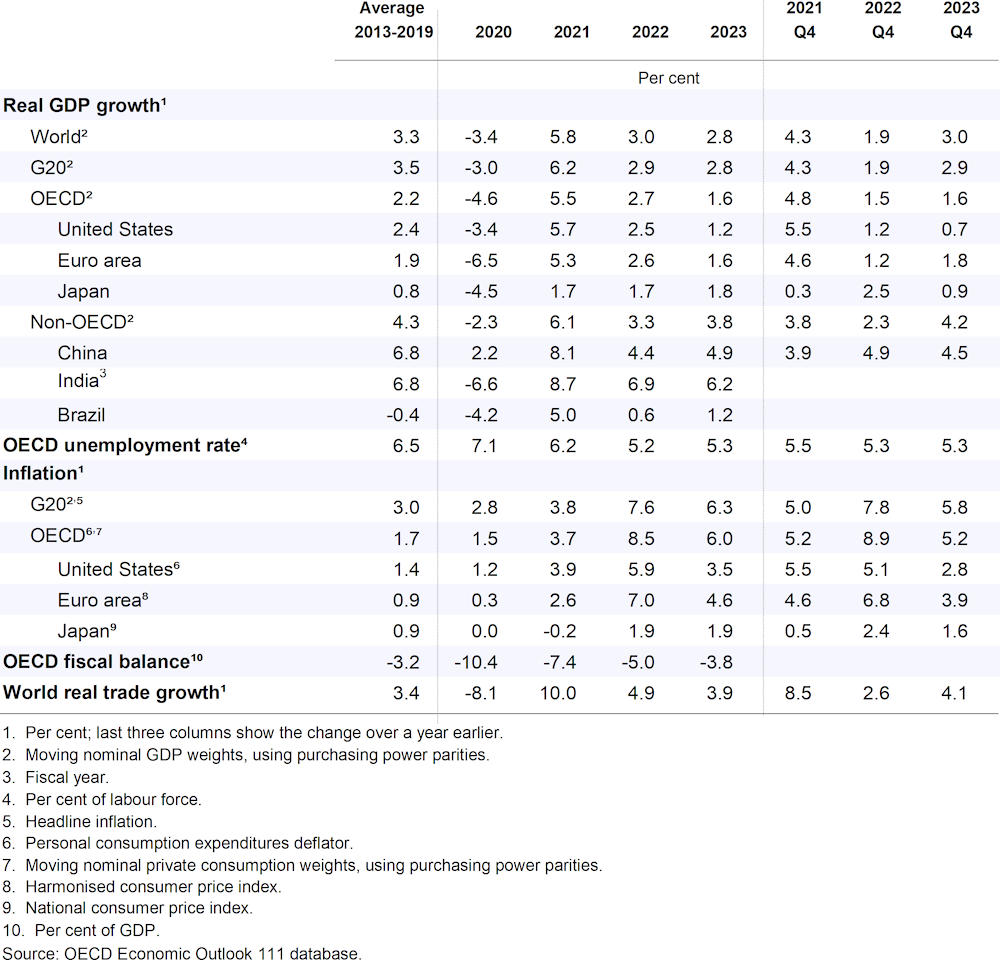

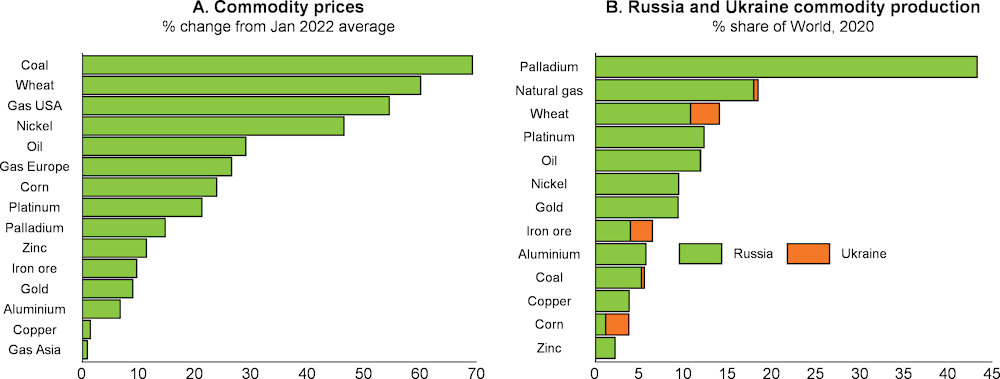

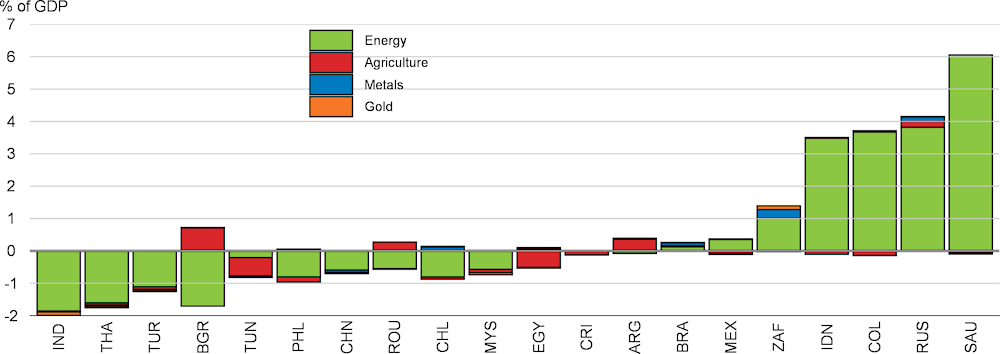

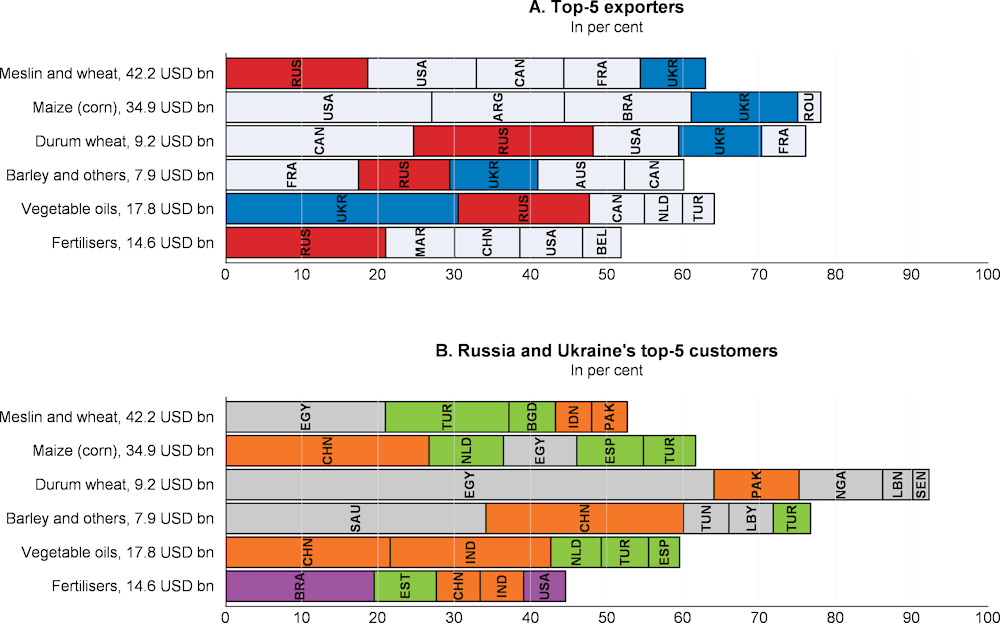

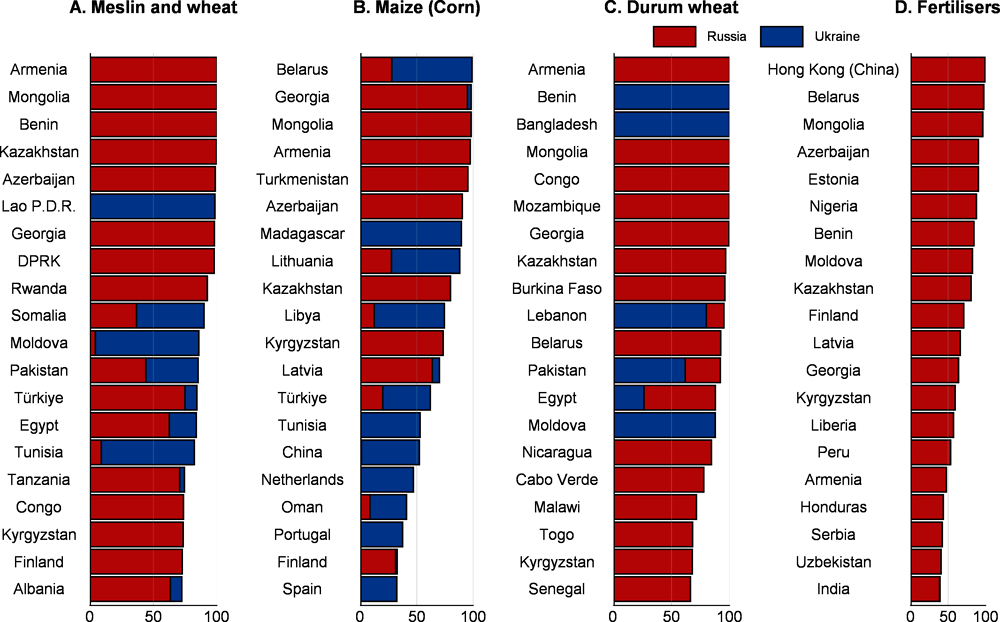

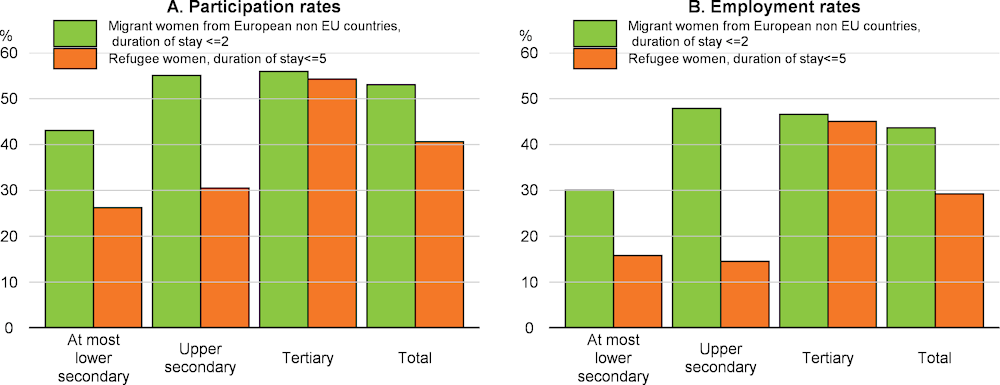

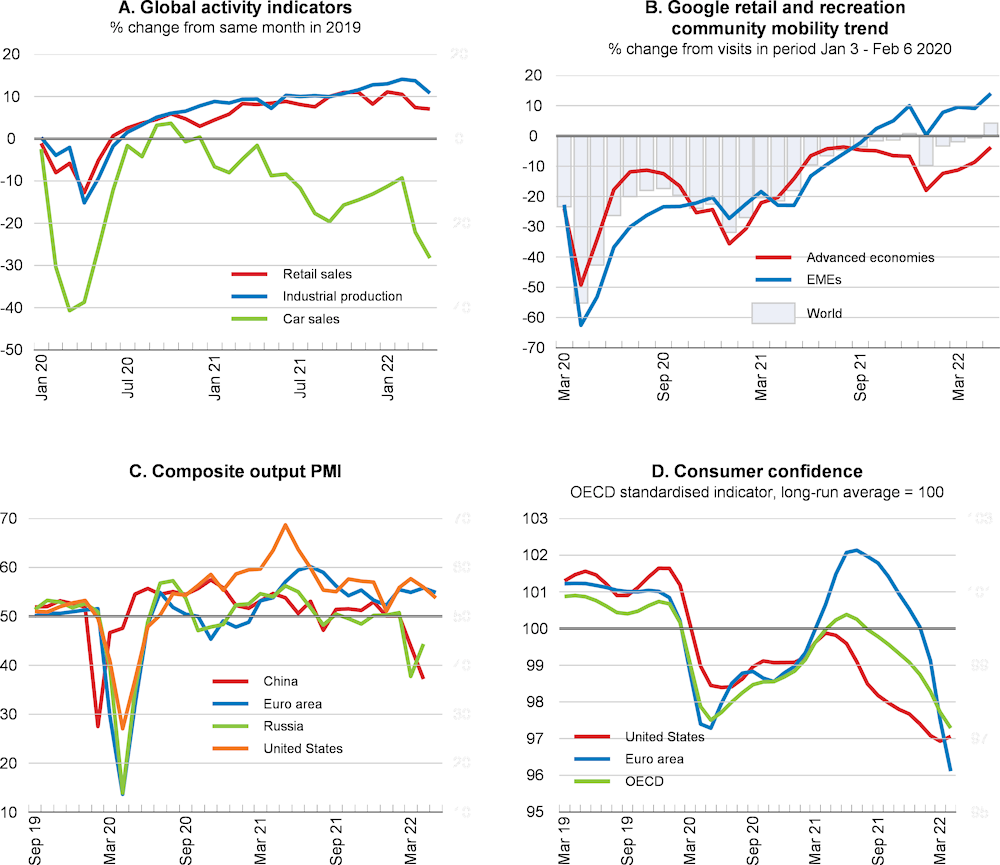

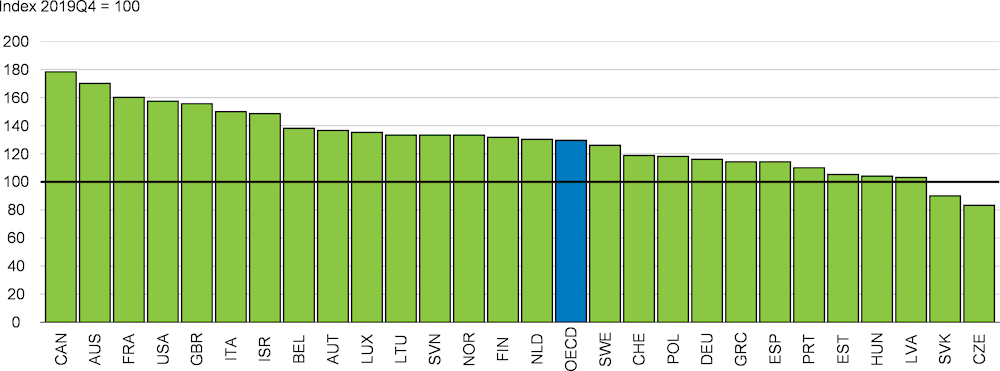

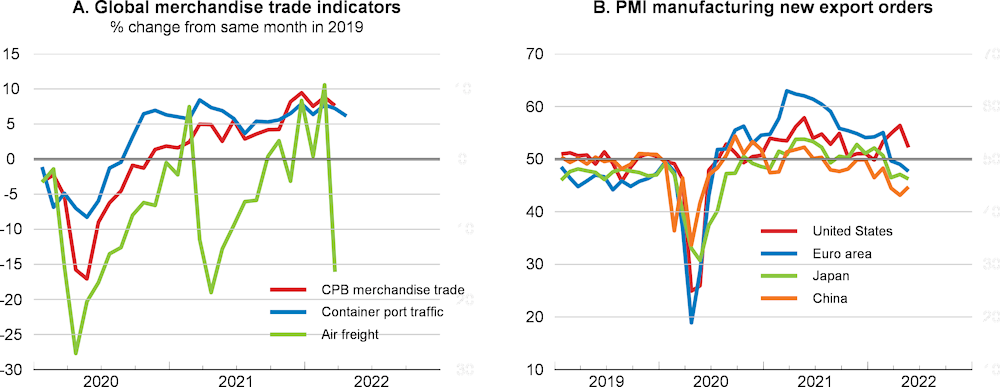

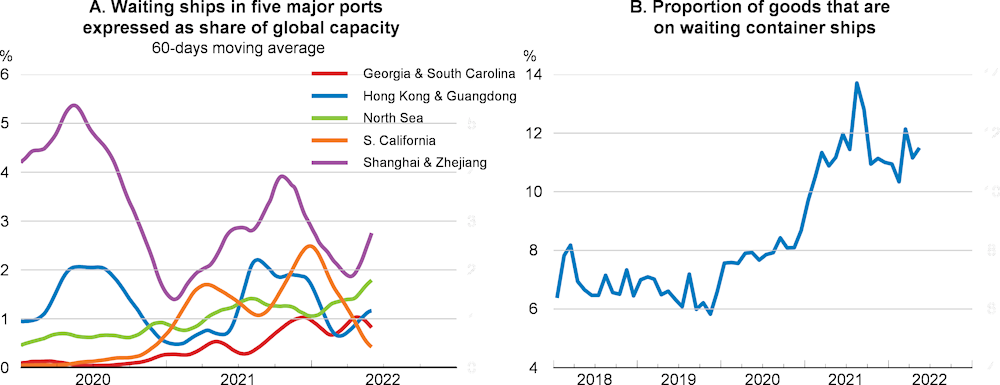

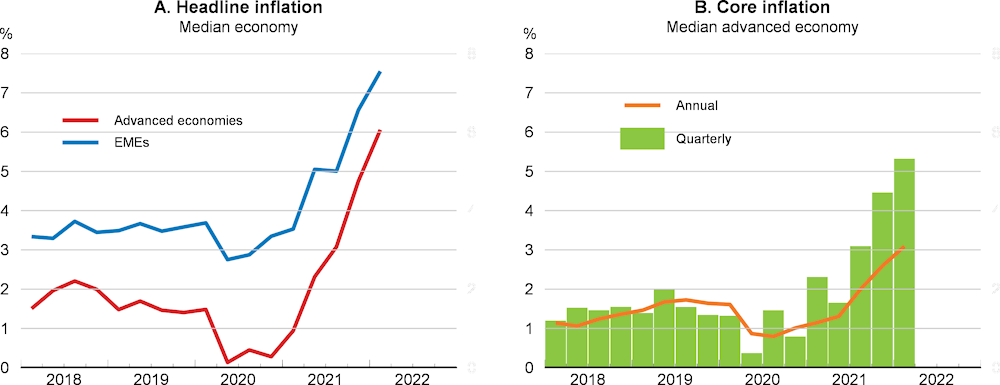

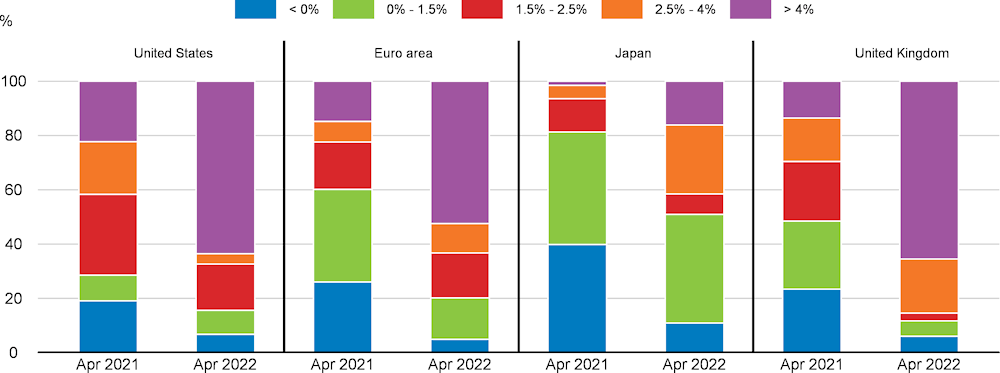

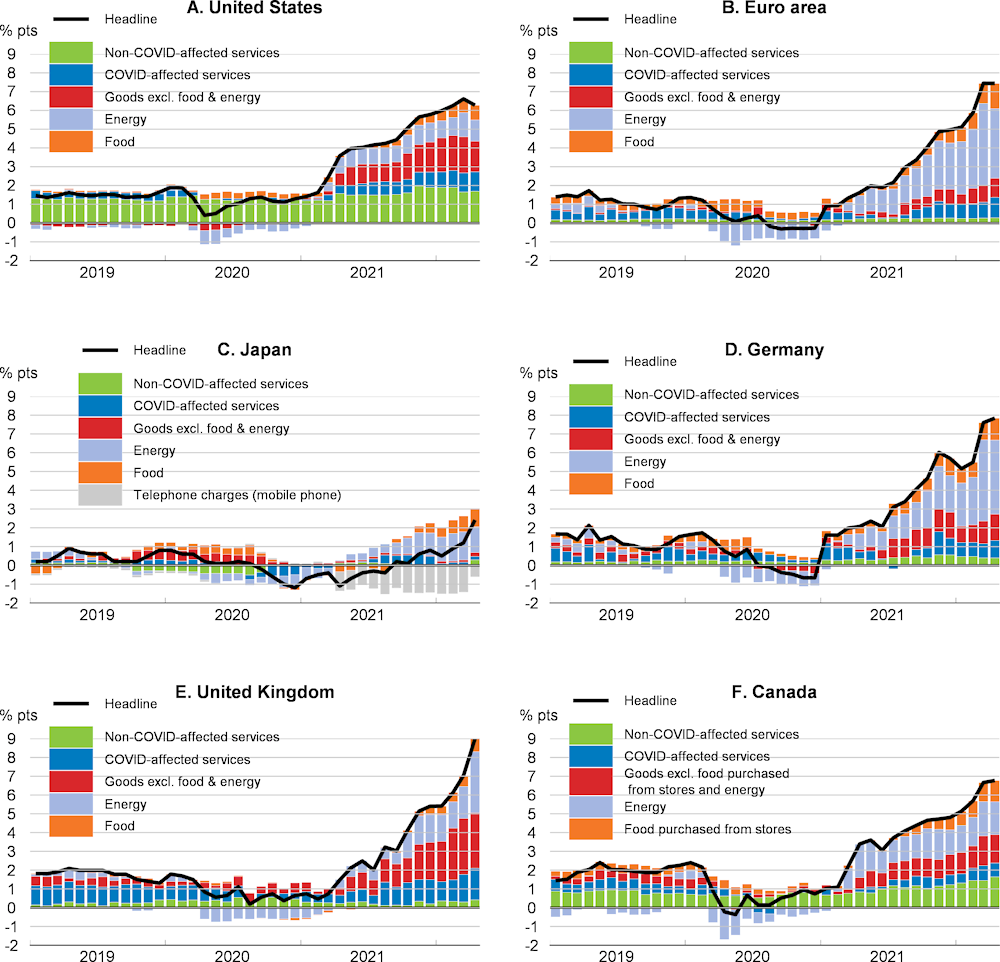

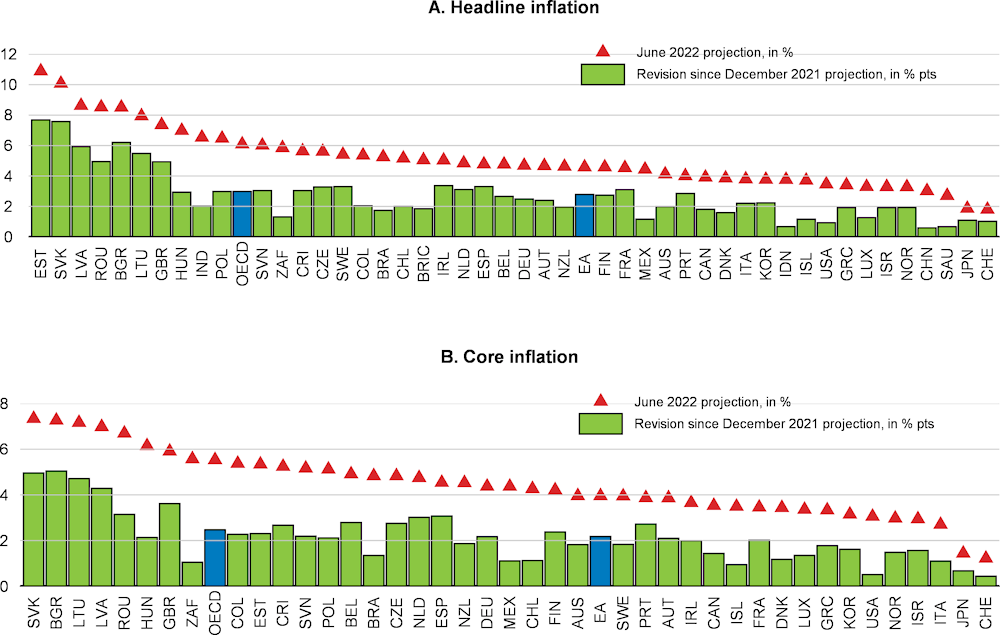

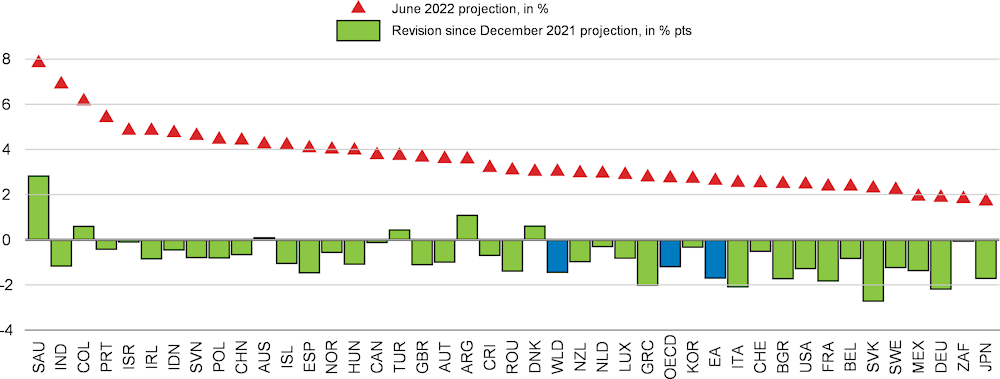

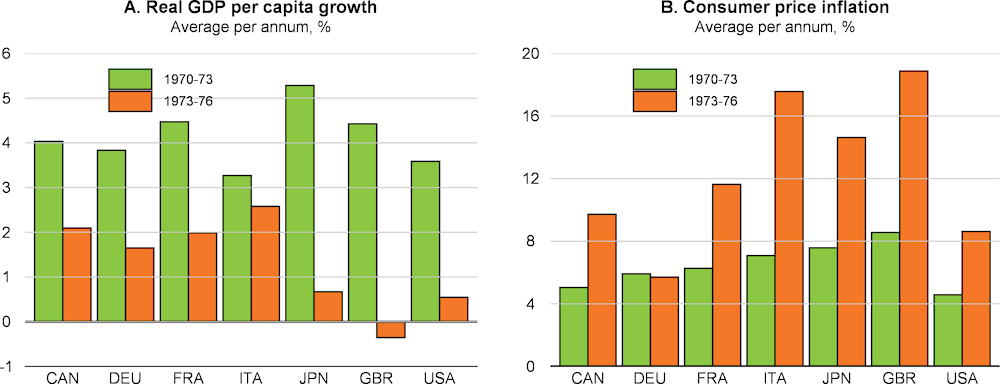

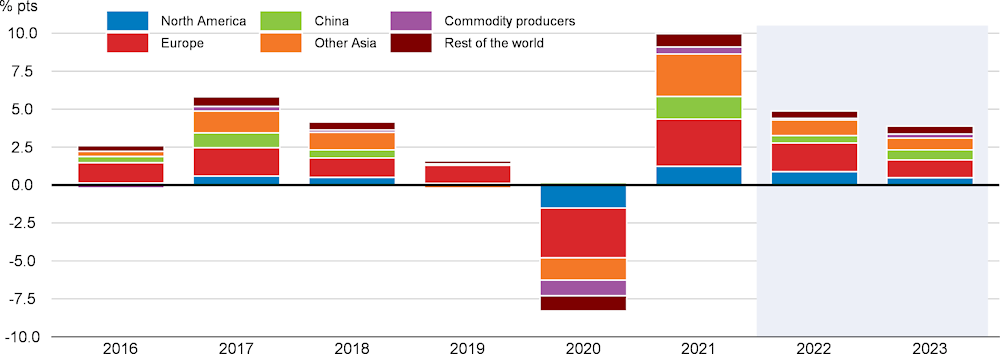

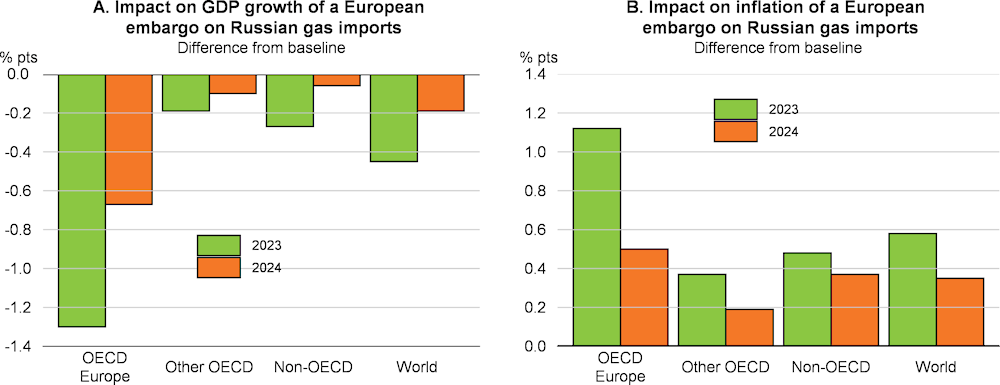

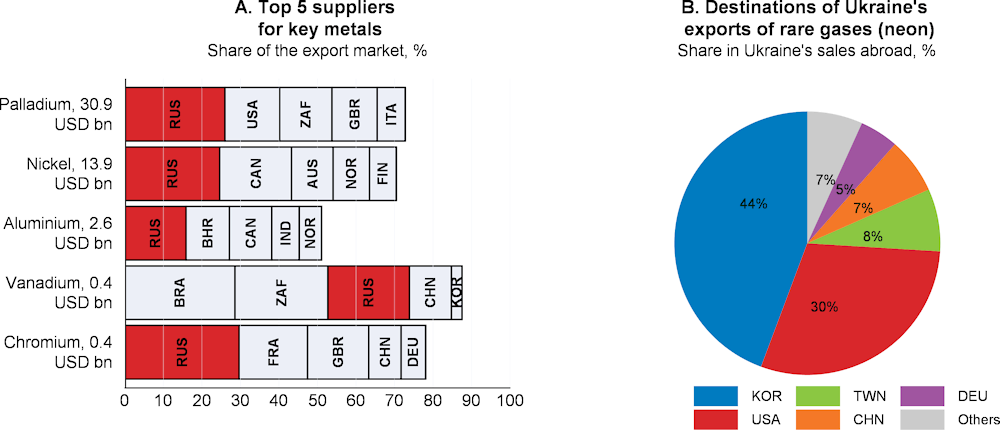

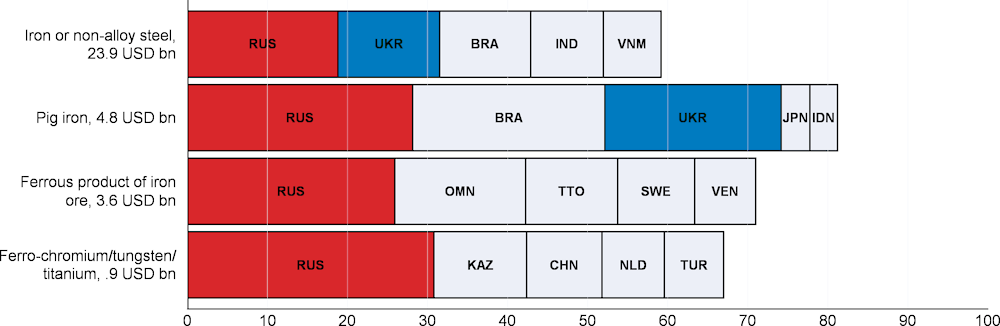

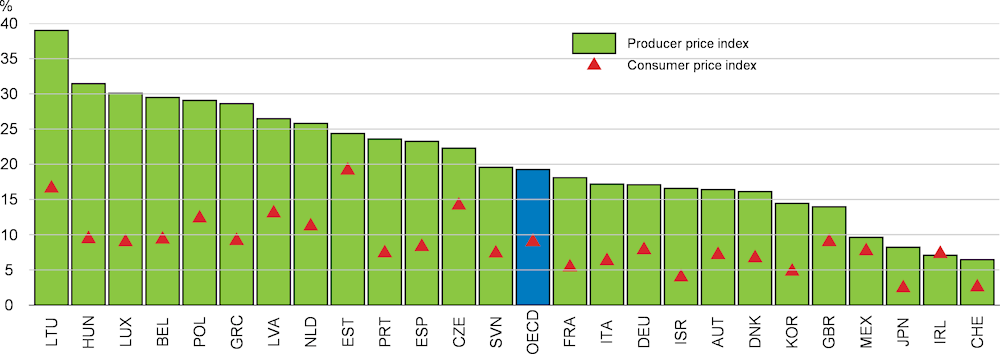

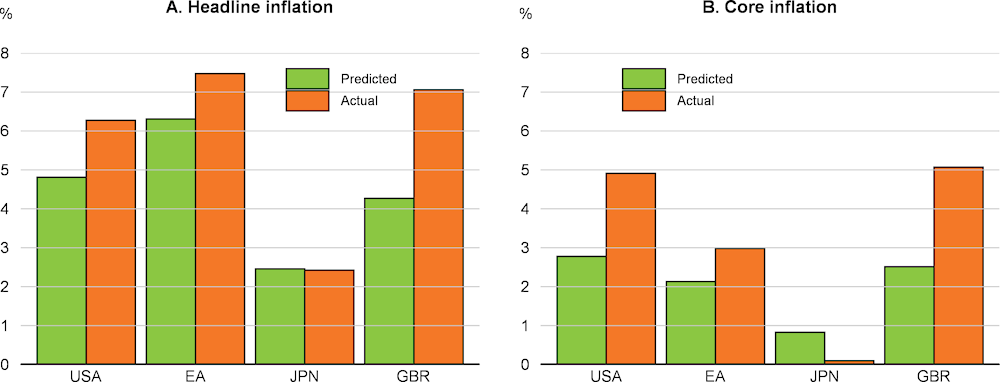

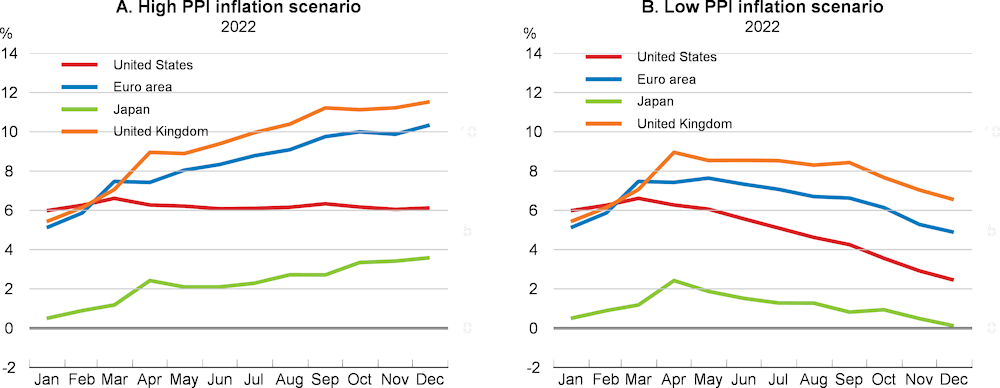

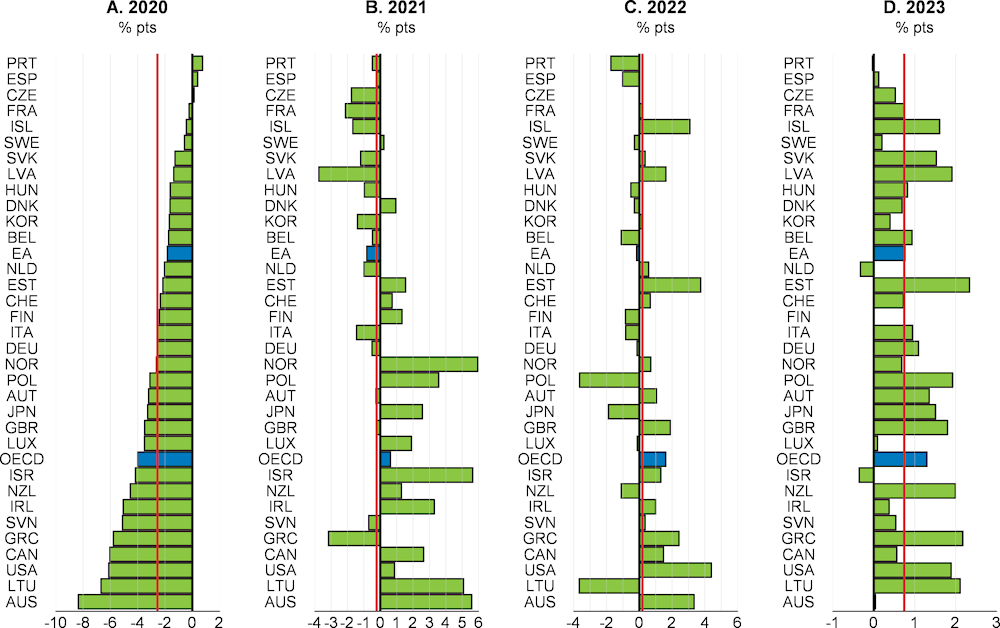

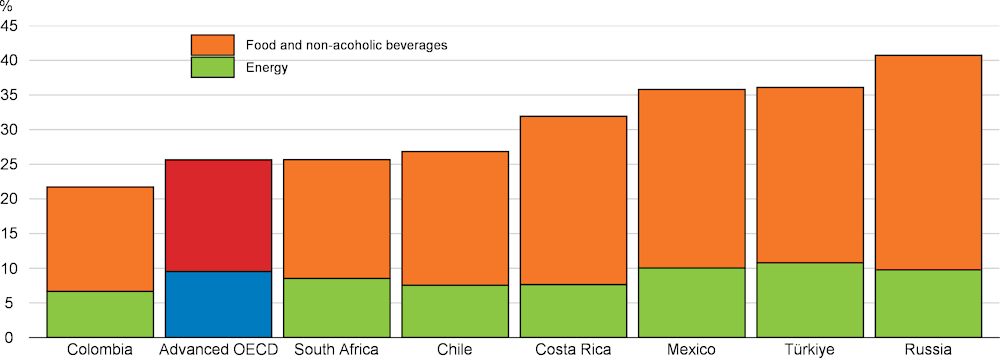

The war in Ukraine has generated a major humanitarian crisis affecting millions of people. The associated economic shocks, and their impact on global commodity, trade and financial markets, will also have a material impact on economic outcomes and livelihoods. Prior to the outbreak of the war the outlook appeared broadly favourable over 2022-23, with growth and inflation returning to normality as the COVID‑19 pandemic and supply-side constraints waned. The invasion of Ukraine, along with shutdowns in major cities and ports in China due to the zero-COVID policy, has generated a new set of adverse shocks. Global GDP growth is now projected to slow sharply this year to 3%, around 1½ percentage points weaker than projected in the December 2021 OECD Economic Outlook, and to remain at a similar subdued pace in 2023 (Table 1.1). In part, this reflects deep downturns in Russia and Ukraine, but growth is set to be considerably weaker than expected in most economies, especially in Europe, where an embargo on oil and coal imports from Russia is incorporated in the projections for 2023. Commodity prices have risen substantially, reflecting the importance of supply from Russia and Ukraine in many markets, adding to inflationary pressures and hitting real incomes and spending, particularly for the most vulnerable households. In many emerging-market economies the risks of food shortages are high given the reliance on agricultural exports from Russia and Ukraine. Supply‑side pressures have also intensified as a result of the conflict, as well as the shutdowns in China. Consumer price inflation is projected to remain elevated, averaging around 5½ per cent in the major advanced economies in 2022, and 8½ per cent in the OECD as a whole, before receding in 2023 as supply-chain and commodity price pressures wane and the impact of tighter monetary conditions begins to be felt. Core inflation, though slowing, is nonetheless projected to remain at or above medium-term objectives in many major economies at the end of 2023.

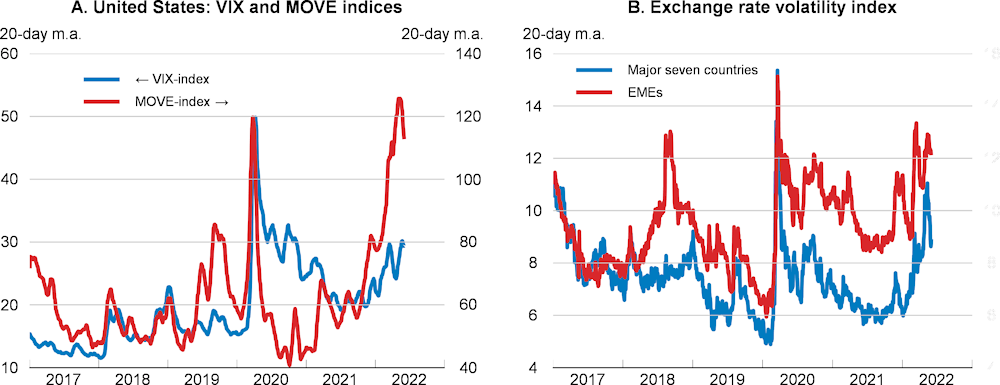

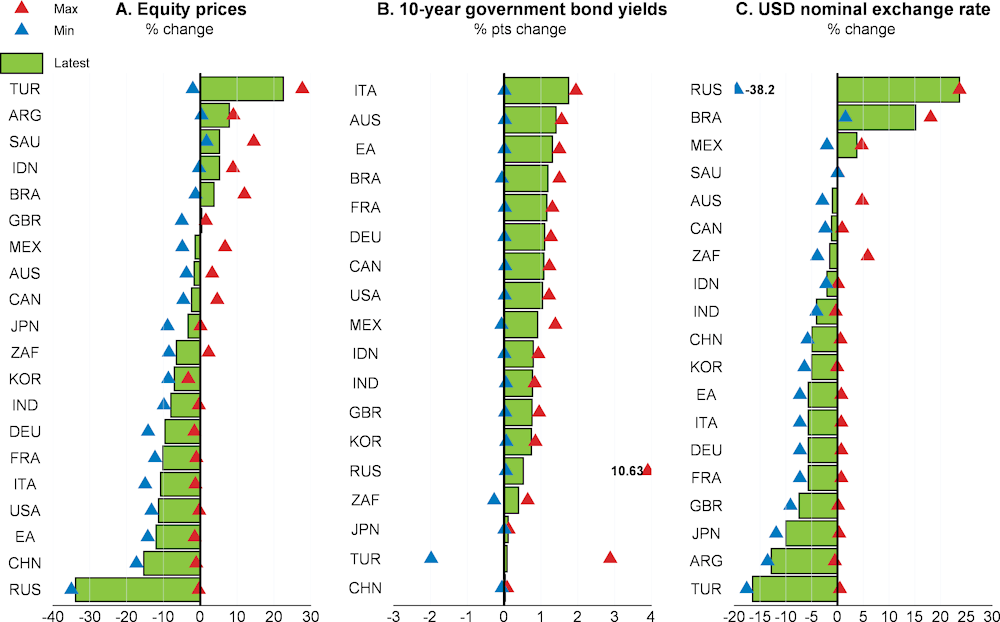

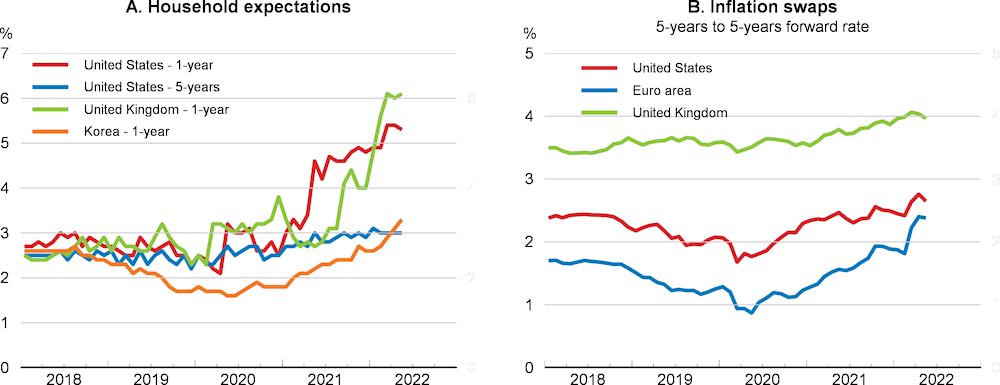

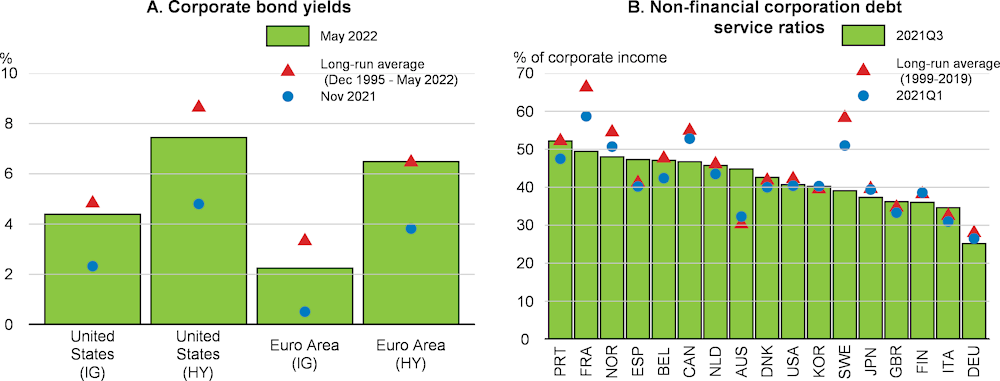

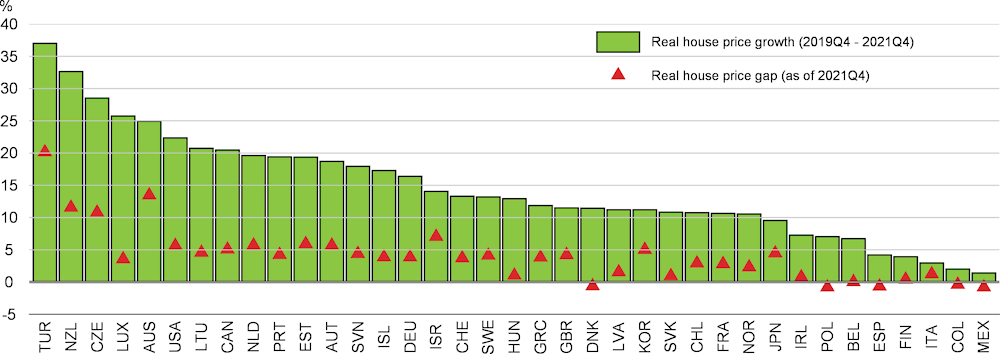

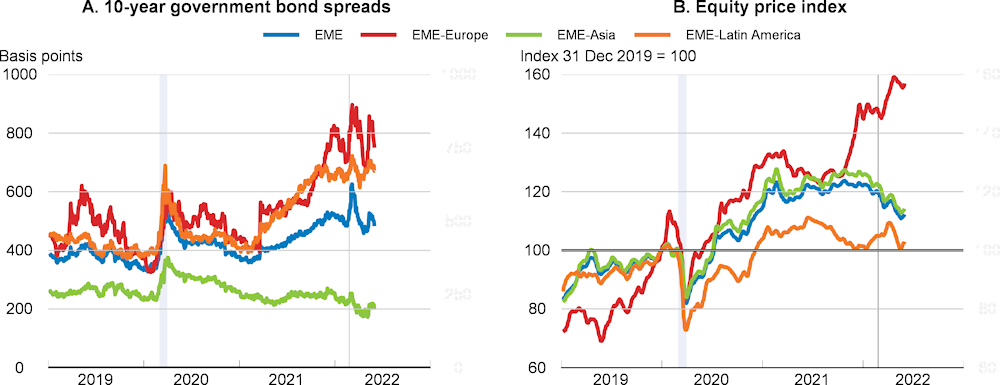

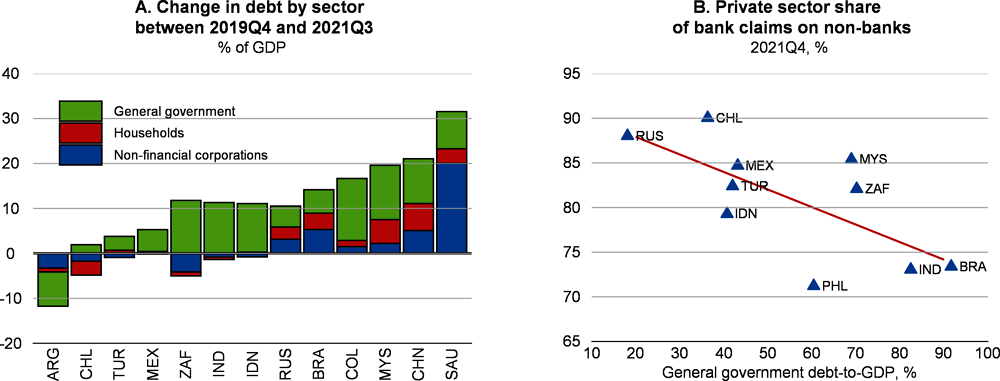

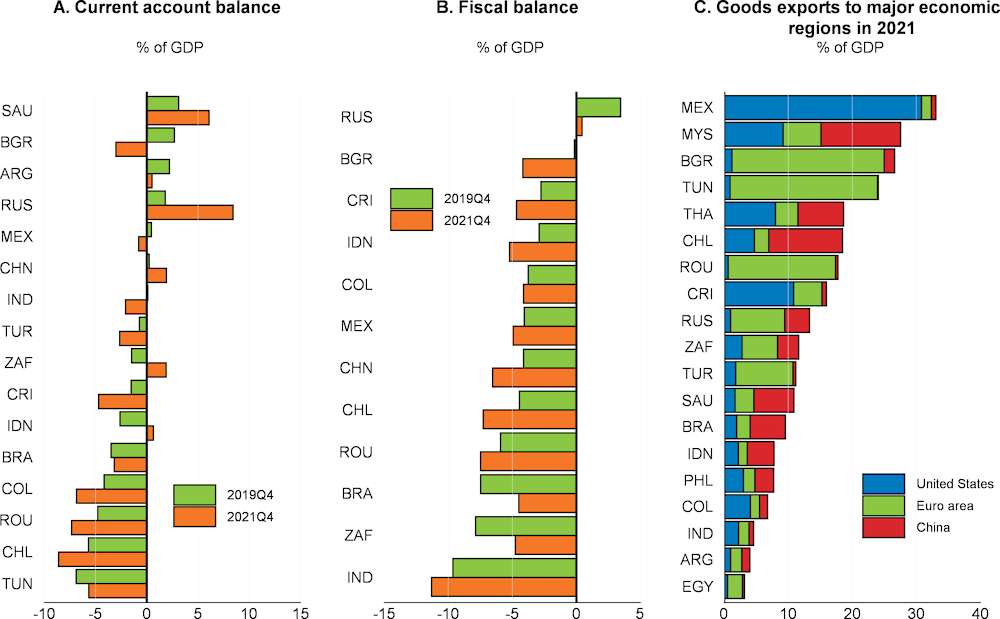

The uncertainty around this outlook is high, and there are a number of prominent risks. The effects of the war in Ukraine may be even greater than assumed, for example because of an abrupt Europe‑wide interruption of flows of gas from Russia, further increases in commodity prices, or stronger disruptions to global supply chains. Inflationary pressures could also prove stronger than expected, with risks that higher inflation expectations move away from central bank objectives and become reflected in faster wage growth amidst tight labour markets. Sharp increases in policy interest rates could also slow growth by more than projected. Financial markets have so far adjusted smoothly to tighter global financial conditions, but there are significant potential vulnerabilities from high debt levels and elevated asset prices. Challenges also remain for many emerging‑market economies, from rising food and energy prices, the slow recovery from the pandemic, high debt, and the potential for capital outflows as interest rates rise in the advanced countries. Risks also remain from the evolution of the COVID‑19 pandemic: new more aggressive or contagious variants may emerge, while the application of zero‑COVID policies in large economies like China has the potential to sap global demand and disrupt supply for some time to come.

The substantial economic costs of the war, elevated uncertainty, and the forthcoming embargo on coal and seaborne oil imports from Russia in Europe add to the challenges already facing policymakers from rising inflationary pressures and the imbalanced recovery from the pandemic:

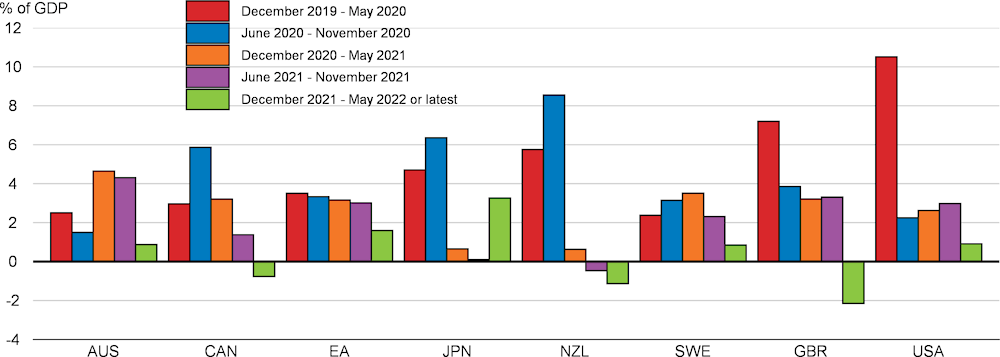

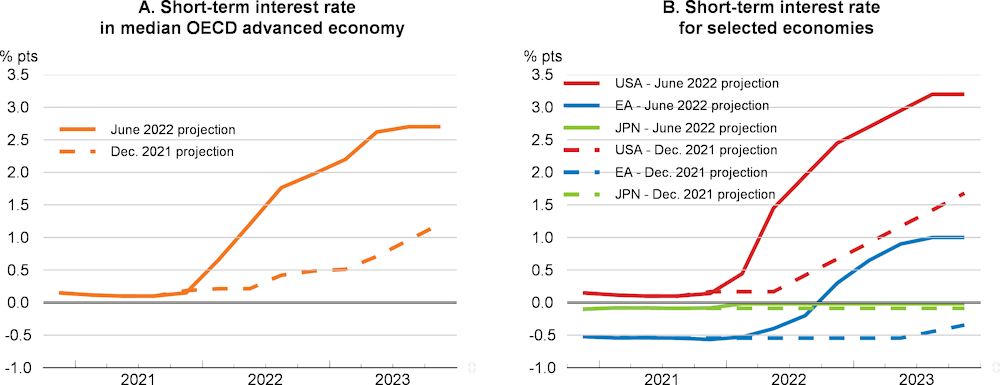

Faced with an adverse supply shock of uncertain duration and magnitude from higher commodity prices, monetary policy should remain focused on ensuring well-anchored inflation expectations. This calls for a differentiated response across the major advanced economies. The case for a relatively quick normalisation is particularly strong in the United States, Canada and many smaller European countries, where the recovery in demand from the pandemic is well advanced and broad‑based inflation pressures were already apparent ahead of the recent commodity price surge. Removing accommodation more gradually is appropriate in economies where core inflation is lower, wage pressures remain modest and the impact of the conflict and the future embargo on growth is greatest. Further policy rate increases are likely to be needed in many emerging‑market economies to help anchor inflation expectations and avoid destabilising capital outflows.

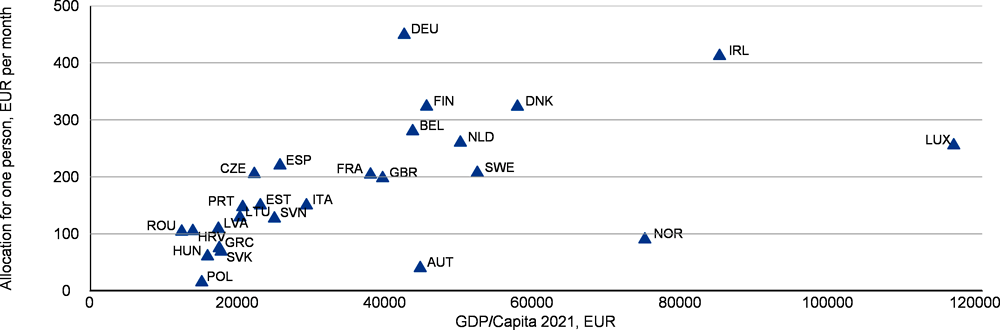

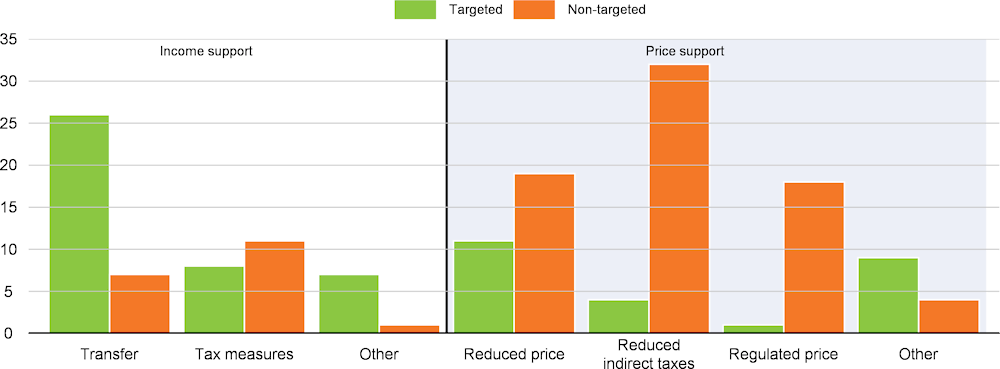

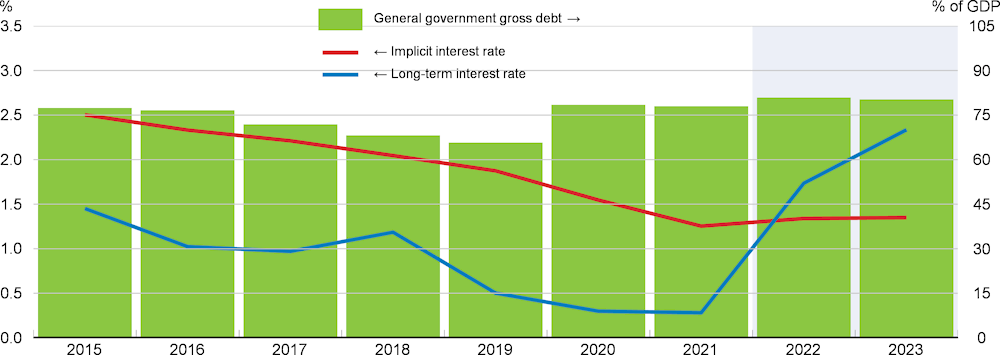

Temporary, timely and well-targeted fiscal measures, where feasible, provide the best policy option to cushion the immediate impact of the commodity and food price shocks on vulnerable households and companies and provide support for refugees from the war. Many countries have appropriately slowed plans for gradual fiscal consolidation in the aftermath of the pandemic, at least until 2023, but consolidation should not be delayed where demand pressures are clearly apparent in inflation. Over the medium and long term, the conflict in Ukraine is raising new fiscal priorities, including accelerated investment in clean energy and higher defence spending, reinforcing the need for a thorough reassessment of the composition of the public finances. Credible fiscal frameworks with strong national ownership can help to provide clear guidance about the medium-term trajectory of the public finances and mitigate concerns about debt sustainability.

The pandemic and the war in Ukraine have exposed many longstanding structural weaknesses, which have been felt unequally across households, firms and countries. Effective and well‑targeted reforms are needed to boost resilience, revive productivity growth, address persisting inequality and accelerate reductions in carbon emissions. International co-operation will need to be preserved to improve prospects for sustainable and equitable longer-term growth by keeping markets open to trade, helping developing countries overcome the COVID-19 pandemic and reduce debt burdens, and enabling more ambitious and effective collective actions on climate change.

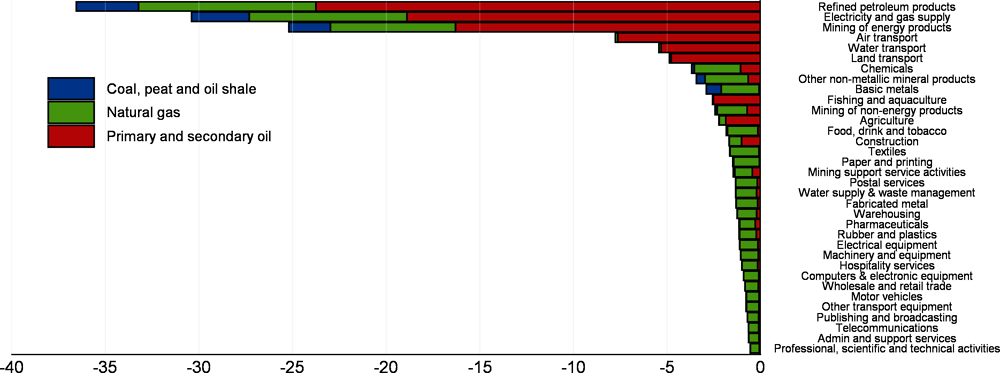

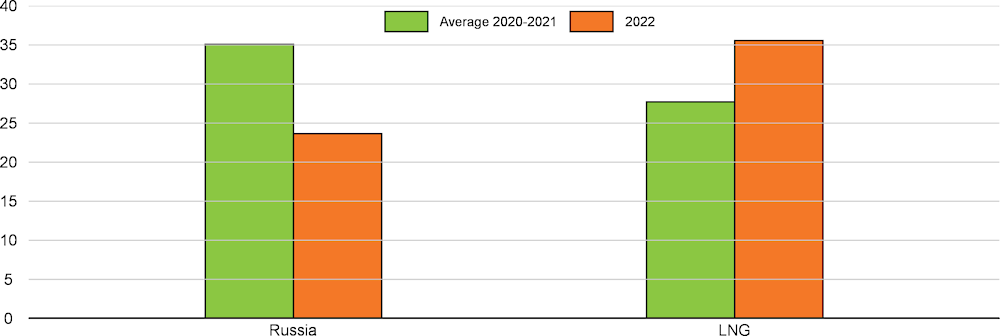

The war has underlined the vulnerability of energy and food security given the dependence of many countries on exports from Russia or Ukraine. Substantial, but not complete, diversification of energy sources can be achieved relatively quickly in some countries, as highlighted by the plans for oil and gas imports set out by the International Energy Agency. Providing regulatory and fiscal incentives to move towards alternative energy sources and invest in innovation and infrastructures are both important steps to help develop clean energy supply and spur energy efficiency. Some progress in this direction has been made in recent public investment plans but more needs to be done to meet the commitments made at COP26. Food security has also become a more pressing concern given the acute risk of economic crises in some developing economies and sharp increases in poverty and hunger. To monitor and mitigate such risks, all countries must provide the assistance necessary to facilitate the planting of new crops, including in Ukraine, tackle logistical barriers limiting the supply of food to countries most at risk, and refrain from export restrictions on food and other agricultural products.