This chapter discusses three aspects that illustrate students’ self-reported exposure to financial literacy in schools: the money-related terms that students report having learned, the money-related tasks that they report having encountered, and the classes in which they report having encountered these money-related tasks. These aspects are related to various student and school characteristics, and to performance in financial literacy.

PISA 2022 Results (Volume IV)

5. Students’ self-reported exposure to financial literacy in school

Abstract

While Chapter 4 discussed the role of parents in discussing money matters with their children, many students may also learn from their teachers and through schools. What topics do students learn about at school and what tasks do they engage in to do so? In what classes do they discuss money matters? The literature on the exact nature of financial education in secondary schools is sparse, and no comparative studies of financial education programmes in school across countries have been carried out. Instead, most studies have focused on evaluating the impact of specific school-based financial education programmes on financial literacy (Becchetti, Caiazza and Coviello, 2013[1]; Kaiser and Menkhoff, 2020[2]; Frisancho, 2020[3]; Bover, Hospido and Villanueva, 2018[4]; Coda Moscarola and Kalwij, 2021[5]).

This chapter discusses students’ self-reported exposure to financial education in school and relates it to various student- and school-level characteristics. Exposure to various types of financial education activities is then related to students’ financial literacy.

What the data tell us

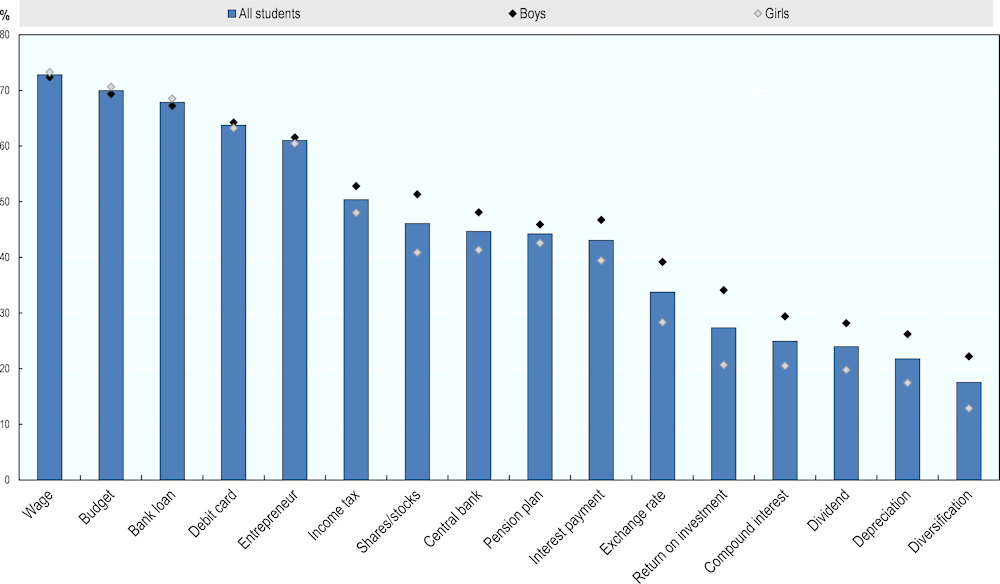

More than two in three students, on average across OECD countries and economies, reported that they had learnt about a wage (73%), a budget (70%) or a bank loan (68%) in school over the preceding 12 months and still know what these terms mean. However, fewer than one in three 15-year-old students, on average across OECD countries and economies, reported that they had learnt about diversification (18%), depreciation (22%), dividend (24%), compound interest (25%) or return on investment (27%) and still know what they mean.

Socio-economically advantaged students and students attending advantaged schools, reported more than their disadvantaged counterparts that they had learned about most of these terms and still know what they mean, on average across OECD countries and economies. More boys than girls reported having learned, and still knowing the meaning of, less familiar terms such as depreciation, compound interest, diversification, shares/stocks, exchange rate and return on investment.

Students who reported that they had learned and still know these finance-related terms outperformed students who did not in the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment, after accounting for student and school characteristics, and students’ performance in mathematics and reading, on average across OECD countries and economies.

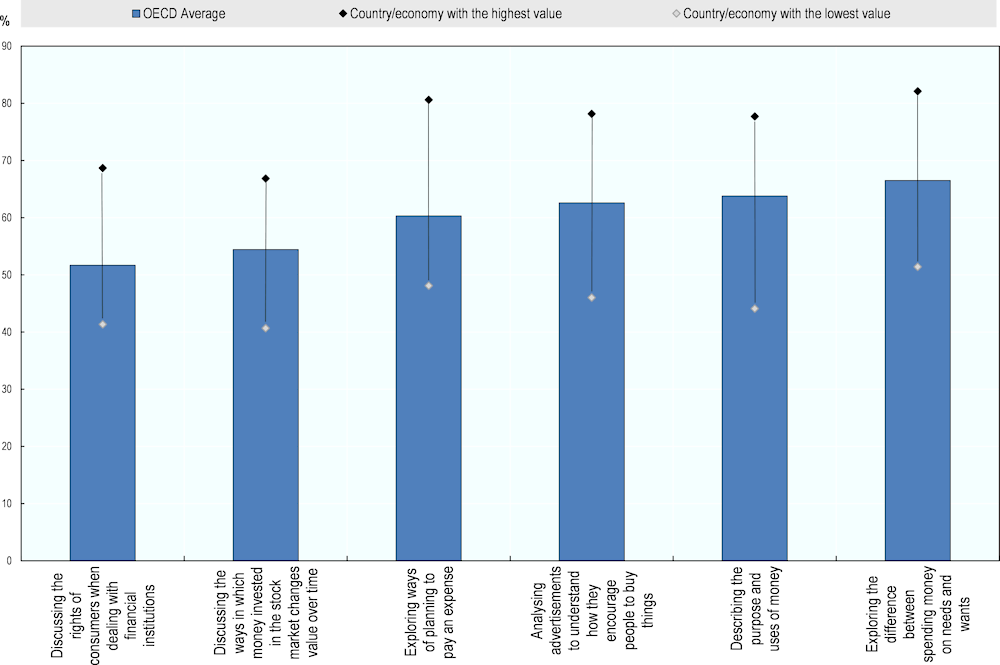

On average across OECD countries and economies, roughly two thirds of students reported having been exposed sometimes or often to tasks exploring the difference between spending money on needs and wants (67%) and to tasks describing the purpose and uses of money (64%).

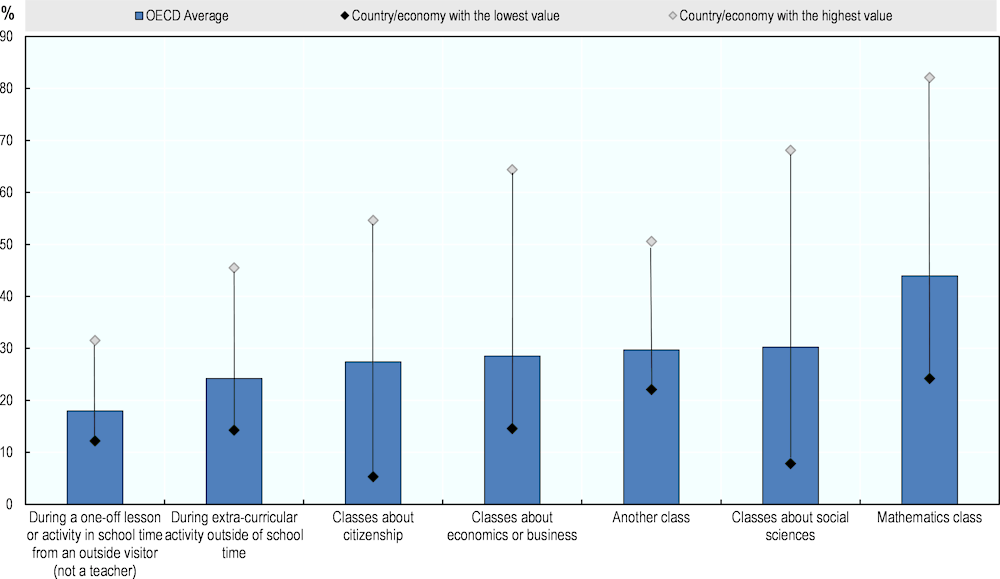

Some 44% of students reported that they had seen personal finance-related tasks in their mathematics classes, on average across OECD countries and economies. Roughly one in three students reported that he or she had seen at least one of these personal finance-related tasks in another class, such as social sciences, citizenship, economics or business.

Self-reported exposure to financial education in schools

The PISA 2022 financial literacy questionnaire asked students about three aspects of the financial education programmes that they might have been exposed to at school over the previous 12 months:

financial terms that they had encountered in school

financial literacy tasks or activities that they had encountered in school

classes in which they might have encountered these types of tasks about money.

The PISA 2022 financial literacy questionnaire also asked students whether they had ever learned how to manage their money. More precisely, students were asked to specify whether this was in a school subject or course specifically about managing their money, in school as part of another subject or course or in an activity outside school. The results based on these questions are not qualitatively different from the results based on the three aspects mentioned above, and they are available in the tables in Annex B.

Across countries, students may have different notions about what it means to know a term or whether they have conducted financial literacy activities in school. Given these differences in how students may interpret the questions in the questionnaire, cross-country comparisons should be conducted with caution; comparisons within countries may be more reliable, although different groups in the same country (boys and girls, for instance) may also have different perspectives, which may be reflected in their reports.

Students were presented with a list of 16 terms related to finance and economics. More than two in three students, on average across OECD countries and economies, reported that they had heard about a wage (73%), a budget (70%) or a bank loan (68%) over the preceding 12 months and still knew what these terms meant. However, fewer than one in three 15-year-old students, on average across OECD countries and economies, reported that they had heard about diversification (18%), depreciation (22%), dividend (24%), compound interest (25%) or return on investment (27%) and still knew what they meant (Figure IV.5.1 and Table IV.B1.5.1). On average among all participating countries, slightly fewer students reported that they had learnt about a wage (67%), a budget (64%), a bank loan (63%) and still knew what these terms meant, and slightly more students reported they had learnt about return on investment (28%), compound interest (26%), dividend (26%) or diversification (19%) and still knew what they meant.

Figure IV.5.1. Students’ self-reported exposure to financial terms in school

Percentage of students who reported that they had learned this term over the previous 12 months and know what it means; OECD average

Note: All gender differences are statistically significant (see Annex A3).

Terms are ranked in descending order of the percentage of students who had learned about them in the previous 12 months and still know what they mean.

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 Database, Table IV.B1.5.1 and Table IV.B1.5.3.

The index of familiarity with concepts of finance was created to reflect how many of the 16 terms students reported learning about over the previous 12 months and whose meaning they still knew.1 On average across OECD countries and economies, students reported that they had learned about and still knew just over 7 of the 16 terms. Students in the Netherlands* were the most knowledgeable, reporting that they knew about 9 of the 16 terms on average; they were followed by students in Austria and Denmark*, who reported knowing about 8 of the 16 terms, on average. At the other end of the index, students in Saudi Arabia reported knowing only just 3 of the 16 terms, followed by students in Bulgaria (about 5 of the terms on average) (Table IV.B1.5.1).

However, there was a wide distribution in the number of terms that students in each country and economy reported that they had learned about and whose meaning they still knew. Although on average across OECD countries and economies, the median student reported knowing roughly 7 of the 16 terms, at least 10% of students in every participating country and economy except Denmark* and the Netherlands* reported knowing none of the 16 terms. In Brazil, Bulgaria, Malaysia, Poland and Saudi Arabia, at least 25% of students reported knowing none of the 16 terms (Table IV.B1.5.2).

Students were asked about the frequency (never, sometimes or often) with which they had encountered six personal finance-related tasks in school lessons over the previous 12 months:

describing the purpose and uses of money

exploring the difference between spending money on needs and wants

exploring ways of planning to pay an expense

discussing the rights of consumers when dealing with financial institutions

discussing the ways in which money invested in the stock market changes value over time

analysing advertisements to understand how they encourage people to buy things.

On average across OECD countries and economies, the percentage of students reporting that they had often encountered personal finance-related tasks over the previous 12 months ranged between 13% (for tasks discussing the rights of consumers when dealing with financial institutions) and 20% (for tasks exploring the difference between spending money on needs and wants). However, more students reported that they had sometimes encountered personal finance-related tasks over the previous 12 months, ranging between 39% (tasks discussing the rights of consumers when dealing with financial institutions) and 48% (tasks describing the purpose and uses of money) of students, on average across OECD countries and economies (Table IV.B1.5.9).

On average across OECD countries and economies, two thirds of students reported having been exposed sometimes or often to tasks exploring the difference between spending money on needs and wants (67%), ranging between 82% in Malaysia and 51% in Italy. Similarly, 64% of students reported having been exposed sometimes or often to tasks describing the purpose and uses of money, on average across OECD countries and economies (ranging between 78% in Denmark* and 44% in Italy. Fewer students reported having been exposed sometimes or often to tasks discussing the rights of consumers when dealing with financial institutions (52% on average across OECD countries and economies; 69% in Malaysia; and 41% in Italy).

The index of financial education in school lessons was created based on students’ responses to how often they recalled having encountered these six tasks or activities. It was standardised so that the mean index across OECD countries and economies was 0 and the standard deviation across OECD countries and economies was 1. Students in the Canadian provinces* and the United Arab Emirates (0.35 for both) reported having been most exposed to financial education in school lessons, while students in Italy (-0.40) and the Flemish community of Belgium (-0.27) reported having been the least exposed over the prior 12 months (Figure IV.5.2 and Table IV.B1.5.9).

Figure IV.5.2. Students’ self-reported exposure to financial literacy tasks in school lessons

Frequency with which students had encountered the following types of tasks or activities in a school lesson over the previous 12 months; OECD average

Items are ranked in ascending order of the frequency with which students had encountered the personal finance-related tasks in a school lesson over the previous 12 months, on average across OECD countries.

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 Database, Table IV.B1.5.9.

Students were also asked in which classes or activities they had encountered these personal finance-related tasks.2 They were permitted to state that they covered these tasks in more than one of these options:

mathematics classes

classes about social sciences

classes about citizenship

classes about economics or business

another class

a one-off lesson or activity during school time from an outside visitor (not a teacher)

extracurricular activities outside of school time.

As shown in Figure IV.5.3, the types of classes or activities where students reported encountering personal finance-related tasks varied substantially across participating countries and economies. Some 44% of students reported that they had seen at least one of these tasks in their mathematics classes, on average across OECD countries and economies; this ranged from a low of 24% of students in the Flemish community of Belgium to a high of 82% of students in Peru.

On average across OECD countries and economies, roughly one in three students reported that he or she had encountered at least one of these personal finance-related tasks in another (non-mathematics) class. On average across OECD countries and economies, 30% of students reported encountering these tasks in classes about social sciences (ranging from 8% in Hungary to 68% in Denmark*); 29% in classes about economics or business (from 15% in Portugal to 64% in the Netherlands*); and 27% in classes about citizenship (from 5% in the Netherlands* to 55% in Czechia).

In addition to school classes, some students reported having seen at least one of these six personal finance-related tasks in other activities. Some 18% of students reported that they had seen at least one of these tasks in a one-off lesson or activity during school time from an outside visitor (not a teacher) and 24% reported that they had seen these tasks in extracurricular activities outside of school time (Figure IV.5.3 and Table IV.B1.5.16).

However, in interpreting these results it is important to take into account that results are based on self-reporting from students, which may differ from the actual exposure to financial education they received. For example, a considerable percentage of students reported that they did not know whether they had seen these tasks in their classes or other activities (between 12% for classes about economics or business, and 23% for one-off lessons from an outside visitor, on average across OECD countries and economies) or that they did not a have a certain class or activity (for instance, 25% of students reported not having citizenship classes, and 41% reported not having economics or business classes, on average across OECD countries and economies) (Table IV.B1.5.16).

Figure IV.5.3. Students’ self-reported exposure to financial literacy tasks in different types of classes or activities

Percentage of students who had encountered personal finance-related tasks in the following classes or activities in the previous 12 months; OECD average

Items are ranked in ascending order of the percentage of students who had encountered personal finance-related tasks in the following classes or activities in the previous 12 months, on average across OECD countries.

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 Database, Table IV.B1.5.16.

Results related to whether students reported having learned how to manage money in a course are available in Annex B.

Variation in self-reported exposure to financial education programmes in school related to student and school characteristics

Gender

In most countries and economies, boys and girls attend the same types of school and follow the same curriculum, so it might be expected that they are equally exposed to financial education programmes. However, results from the PISA 2022 financial literacy questionnaire show that girls reported somewhat less exposure to financial terms and personal finance-related tasks than boys.

On average across all participating as well as OECD countries and economies, girls reported knowing around 6 of the 16 finance terms while boys reported knowing closer to 7 of those terms (Table IV.B1.5.3).

As shown in Figure IV.5.1, the less familiar a term – that is, the smaller the percentage of all students who reported that they had learned about the term in the previous 12 months and still knew what the term meant – the greater the gender difference in familiarity in favour of boys, on average across OECD as well as all participating countries and economies. Indeed, the difference in the percentage of boys and girls who reported having learned, and still knowing the meaning of, the most familiar terms – “wage”, “budget”, “bank loan”, “debit card” and “entrepreneur” – was very small (roughly 1 percentage point, on average across OECD countries and economies). On the contrary, across OECD countries and economies, more boys than girls reported having learned, and still knowing the meaning of, less familiar terms such as “depreciation” (9 percentage points difference in favour of boys), “compound interest” (9 percentage points), “diversification” (9 percentage points), “shares/stocks” (10 percentage points), “exchange rate” (11 percentage points) and “return on investment” (13 percentage points). (Figure IV.5.1 and Table IV.B1.5.3).

Some gender differences in favour of boys were also observed in the proportion of students who reported having encountered the six personal finance-related tasks in school lessons over the previous 12 months. The gender differences was relatively limited in the proportion of students who reported having been exposed to some of the most frequently encountered tasks, such as exploring the difference between spending money on needs and wants (4 percentage points in favour of boys, on average across OECD countries and economies and 3 percentage points across all participating countries and economies) or describing the purpose and uses of money (5 percentage points favour of boys, on average across OECD countries and economies, compared to 4 percentage points on average across all countries and economies). However, the gender differences were relatively larger on some less frequently encountered tasks, such as discussing the rights of consumers when dealing with financial institutions (10 percentage points favour of boys, on average across OECD countries and economies, 9 percentage points among all participating countries and economies) (Table IV.B1.5.10).

Gender differences in self-reported exposure to the six personal finance-related tasks in the various types of classes (such as mathematics, social sciences or others) or activities were quite limited, on average across OECD countries and economies as well as among all participating countries and economies (Table IV.B1.5.17).

It is difficult to attribute these gender gaps to any one cause. The greater self-reported knowledge of financial terms and concepts amongst boys might be attributable to their greater self-reported exposure to financial activities, lessons, and tasks. At the same time, boys and girls may have different thresholds about what it means to “know what a term/concept means” or different perceptions about their level of knowledge (Beyer and Bowden, 1997[6]; Herbst, 2020[7]; Aristei and Gallo, 2022[8]). In addition, while they may attend the same schools, boys and girls may have different tendencies to enrol in certain programmes or courses, or they may have reported learning these terms in school even if they had in fact learnt them in other contexts. Further research in this area may be warranted.

Student- and school-level socio-economic profile

Students from more socio-economically advantaged backgrounds – in terms of either their own personal family background or the socio-economic profile of their school – reported more than their disadvantaged peers that they know about terms related to economics and finance. According to students’ reports, advantaged students3 had learned about and still knew the definitions of two more of the 16 terms than disadvantaged students had learned, on average across OECD countries and economies as well as among all participating countries and economies. The difference was statistically significant in each of the countries and economies that participated in the assessment, and exceeded three terms in Bulgaria and Malaysia. Indeed, in Malaysia, students’ socio-economic status explained 6% of the variation in the number of terms that students knew. At the other end of the scale, in the Flemish community of Belgium, Italy, Portugal and Saudi Arabia, advantaged students knew roughly only one more term than disadvantaged students, according to students’ reports (Table IV.B1.5.4).

Similar results are observed for students attending advantaged schools (measured as the average socio-economic background of students in the school)4 (Table IV.B1.5.5).

Significantly more advantaged than disadvantaged students reported knowing each of the 16 terms, on average across OECD and all participating countries and economies (Table IV.B1.5.4). The gap, as measured by the percentage of advantaged students minus the percentage of disadvantaged students who reported that they had learned about and still knew the definition of a term, was widest for the terms “shares/stocks” (a gap of 17 percentage points on average across OECD countries and economies), “entrepreneur” (13 percentage points), “exchange rate” (12 percentage points), “interest payment” (12 percentage points), “budget” (12 percentage points) (Table IV.B1.5.4). Students attending advantaged schools also reported more than their counterparts attending disadvantaged schools that they had learned about most of these terms in the previous 12 months and still knew what they meant, on average across OECD countries and economies as well as across all participating countries and economies. However, there was no significant difference for the term “diversification” (Table IV.B1.5.5).

In Austria, the Flemish community of Belgium, Bulgaria, Czechia, Hungary, Italy, Poland and Portugal, more disadvantaged students than advantaged students reported that they had sometimes or often encountered most of the six personal-finance related tasks described above over the 12 months prior to the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment; by contrast, in Brazil, Denmark*, Malaysia, Peru and the United Arab Emirates, more advantaged students than disadvantaged students reported so. On average across OECD countries and economies, disadvantaged students reported more than their advantaged counterparts that they had encountered these financial literacy tasks (Table IV.B1.5.11). Similar patterns were observed between students attending advantaged and disadvantaged schools (Table IV.B1.5.12).

Results related to school location and to programme orientation (i.e. general vs. vocational/pre-vocational) are available in the tables in Annex B.

Self-reported exposure to financial education in schools and performance in financial literacy

Some patterns in the relationship between self-reported exposure to financial education in schools and performance in financial literacy may be consistent with the fact that financial education is still starting to be introduced in formal school education, and that this is done in different ways in different countries or economies, as discussed in Chapter 1. Moreover, PISA data offer a cross-sectional overview of students’ exposure to financial education in school and of its association with financial literacy performance, but cannot be used to draw causal conclusions about the direction of this relationship.

Students who reported having been more exposed to financial or economics-related terms were also more financially literate, as measured by the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment. Each additional term, of the 16 proposed, that a student reported having learned in school in the previous 12 months, and whose definition the student still knew, was associated with a 4-point increase in his/her financial literacy score, on average across both OECD countries and economies and all participating countries and economies, after accounting for student and school characteristics, such as gender, student and school socio-economic profile, immigrant background, programme orientation and school location (Table IV.B1.5.8).

In the Canadian provinces*, Czechia, Malaysia, the Netherlands* and the United Arab Emirates, the relationship between a student’s performance in financial literacy and the number of finance/economics-related terms the student reported having learned in the previous 12 months and whose meaning the student still knew was about 5 score points per additional term the student still knew, after accounting for student and school characteristics.5 By contrast, in Portugal, reporting having learned an additional term was not associated with greater performance in the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment. These differences were significant in all other countries and economies that participated in the assessment and had valid data, both before and after accounting for student and school characteristics (Table IV.B1.5.8).

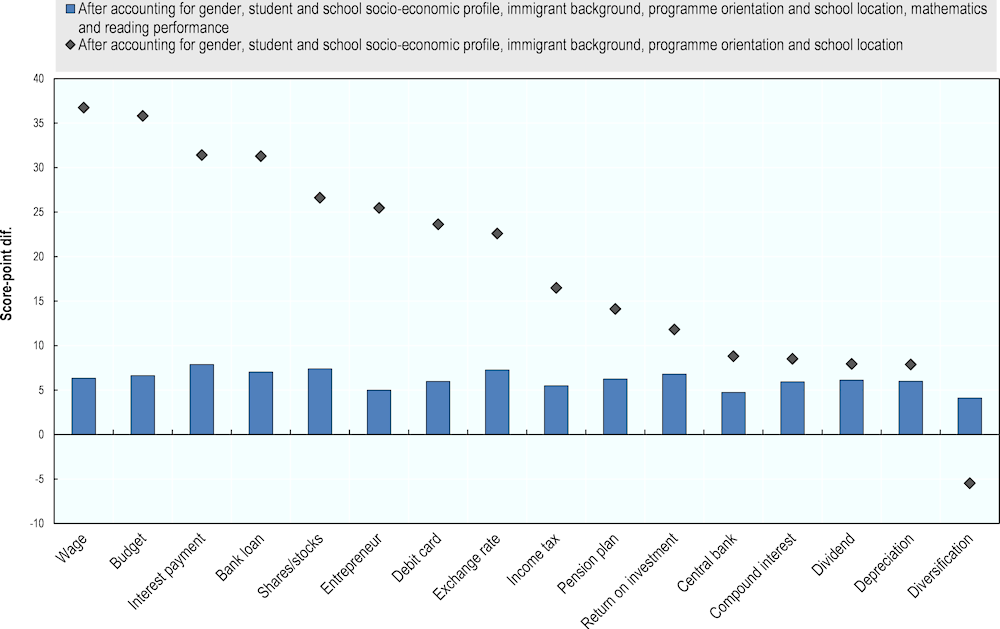

Figure IV.5.4. Financial literacy performance, by students’ self-reported exposure to financial terms in school

Score-point difference between students who were exposed to a term and still know what it means and those who were/do not; OECD average

1. The socio-economic profile is measured by the PISA index of economic, social and cultural status.

Note: Score-point differences that are statistically significant are marked in a darker tone; all score-point differences after accounting for student and school characteristics are statistically significant (see Annex A3).

Terms are ranked in descending order of the score-point difference between students who were exposed to the term and still know what it means and those who were/do not, after accounting for student and school characteristics.

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 Database, Table IV.B1.5.8.

Self-reported exposure to individual terms was associated with different performance gaps. The largest performance gaps, in favour of students who reported that they know the meaning of the terms, were for the terms “wage” (a difference of 38 score points, on average across OECD countries and economies and after accounting for student and school characteristics), “budget” (37 points), “bank loan” (32 points) and “interest payment” (32 points). The performance gaps related to self-reported exposure to these individual terms were significant in every country and economy that participated in the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment, after accounting for student and school characteristics. These terms were amongst those that were most commonly reported as known by 15-year-old students (Figure IV.5.1 and Figure IV.5.4 and Tables IV.B1.5.1 and IV.B1.5.8).

In interpreting these results, it is important to consider that high performing students may be more likely to recall having been exposed to these terms and still know what they mean than low performing students. Even after taking into account not only student and school characteristics, but also students’ performance in mathematics and reading (indicating their overall ability in the main school subjects), self-reported exposure to each of the financial terms is associated with higher financial literacy performance, on average across OECD and all participating countries and economies. Financial literacy performance gaps associated with knowing the meaning of each of the various financial or economics-related terms, after taking into account student and school characteristics as well as student performance in math and reading, ranged from 4 to 8 score points, on average across OECD and all participating countries and economies (Table IV.B1.5.8).

While self-reported exposure to finance/economics-related terms was associated with greater financial literacy across most participating countries and economies, students’ self-reported exposure to personal finance-related tasks in school lessons was associated in different ways to financial literacy in different countries. For instance, for each additional unit on the index of financial education in school lessons, students in the United States* scored 14 points lower in financial literacy and students in the Flemish community of Belgium scored 13 points lower, after accounting for student and school characteristics (gender, student and school socio-economic profile, immigrant background, programme orientation and school location). However, self-reported exposure to these tasks in school was associated with an improvement in financial literacy performance in Malaysia and Peru (an improvement of 8 points, after accounting for student and school characteristics) (Table IV.B1.5.15).

Also when looking at self-reported exposure to each of the six personal finance-related tasks in school, the direction of the performance gap was not consistent across countries and economies: while self-reported exposure to most of the personal finance-related tasks in school was associated with lower scores in financial literacy in most participating countries and economies, in Malaysia and Peru self-reported exposure to most tasks was associated with higher scores in financial literacy, after accounting for student and school characteristics. The negative association between self-reported exposure to these tasks and financial literacy performance was relatively larger for tasks that were less frequently encountered than for more frequent tasks, on average across OECD countries and economies. On average across OECD countries and economies, students who reported having been exposed to tasks discussing the rights of consumers when dealing with financial institutions, which was the least encountered task on average, scored 25 points lower than students who reported not having encountered these tasks, after accounting for student and school characteristics. Students who reported having been exposed to tasks describing the purpose and uses of money, which was among the most common tasks on average, scored 7 points lower than students who reported not having encountered these tasks, after accounting for student and school characteristics (Table IV.B1.5.15).

It is important to note that these results do not imply a causal relationship in which exposure to personal finance-related tasks in school lessons leads to poorer financial literacy. Indeed, several studies based on randomised control trials show a positive impact of school-based financial education programmes on students’ financial knowledge (Becchetti, Caiazza and Coviello, 2013[1]; Kaiser and Menkhoff, 2020[2]; Frisancho, 2018[9]; Frisancho, 2020[3]; Bover, Hospido and Villanueva, 2018[4]; Coda Moscarola and Kalwij, 2021[5]; Amagir et al., 2018[10]). The negative association between self-reported exposure to the six personal finance-related tasks in school and financial literacy performance assessed in PISA may be related to a variety of reasons. It is possible that students with poorer financial literacy skills (or poorer cognitive skills in general) might be those who attend classes where such tasks are presented. After taking into account not only student and school characteristics, but also students’ performance in mathematics and reading (indicating their overall ability in the main school subjects), the difference in financial literacy performance between students who reported having been exposed or not to the six personal finance-related tasks becomes very small or null in all participating countries and economies (Table IV.B1.5.15). It may also be possible that financial education programmes are emphasised in schools whose students may be, a priori, less financially literate, as a way to address students who need these skills the most.

Students who reported having encountered the personal finance-related tasks in their mathematics classes scored 7 points higher in the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment than students who reported not having encountered such tasks6 in their mathematics classes, on average across OECD countries and economies (8 points across all participating countries and economies), after accounting for student and school characteristics. However, students who reported having encountered the personal finance-related tasks in their citizenship classes scored 11 points lower than students who reported not having encountered such tasks in their citizenship classes, on average across OECD countries and economies, and 12 points lower on average across all participating countries and economies, after accounting for student and school characteristics. Students’ financial literacy performance was not related to students’ reports of having encountered personal finance-related tasks in social sciences, economics or business classes, on average across OECD as well as all participating countries and economies, after accounting for student and school characteristics. In interpreting these results it is also important to note that the direction of the performance gap related to self-reported exposure to these personal finance-related tasks in school classes was, again, not consistent across countries and economies (Table IV.B1.5.22).

The OECD Recommendation on Financial Literacy insists on the importance of providing long-term and structural approaches to develop the financial literacy of youth, as opposed to one-off interventions (OECD, 2020[11]). PISA 2022 data show that students who reported having encountered personal finance-related tasks in a one-off lesson or activity during school time from an outside visitor, or during extracurricular activities outside of school time, scored lower than students who reported not having encountered such tasks during these activities, on average across OECD countries and economies. The negative performance differences were observed in most countries and economies that participated in the assessment (Table IV.B1.5.22).

Furthermore, it cannot be inferred from these results that mathematics classes are the best vehicle for imparting knowledge about financial matters to students, or that citizenship classes are an ineffective way of teaching financial literacy. Students who reported having been exposed to personal finance-related tasks in different classes or venues might be different from those who reported having been exposed in ways that could not be accounted for in the analysis. It might be the case, for instance, that students whose parents or teachers thought they were deficient in financial skills had encouraged them to attend certain classes or extracurricular activities to acquire those skills, or that certain classes and extracurricular activities on financial literacy might be targeted at students who need to acquire those skills the most. It might also be the case that money matters are only discussed in advanced mathematics classes, i.e. classes that are by definition attended by higher performing students. Stronger students, i.e. those who tend to score higher in the financial literacy assessment, would also be those who encounter such topics in mathematics class. Indeed, after taking into account students’ performance in mathematics and reading (indicating their overall ability in the main school subjects), the difference in financial literacy performance between students who reported having been exposed or not to personal finance-related tasks in various classes and activities becomes very small or null in all participating countries and economies (Table IV.B1.5.22).

Again, it is important to remember that most studies to date have examined the effect of individual programmes on specific populations. Impact assessments of school-based financial literacy programmes in participating countries and economies evaluate the effectiveness of such programmes in improving students’ levels of financial literacy (Box IV.5.1). PISA 2022 goes further than many other previous studies to provide a snapshot on students’ self-reported exposure to financial terms and personal finance-related tasks in school. However, it is important to note that self-reported information should be interpreted with caution as it reflects students’ recollection of what they learned through exposure to personal finance-related tasks, rather than an objective assessment of the quality and comparability of what was taught, of the accuracy of the information delivered, and of the effectiveness of these programmes. PISA provides a large array of data that are comparable across countries; however, this information should always be interpreted within the context of individual countries or schools.

Box IV.5.1. Assessing the impact of school lessons on financial literacy

In 2010-2011, researchers conducted a randomised control trial (RCT) to evaluate the impact of a pilot financial education programme targeting high school students in Brazil. The programme integrated financial literacy lessons in the school curriculum via in school and take-home exercises, and covered about 25 000 students from 892 public high schools in six Brazilian states. Data were collected in schools through three surveys (one baseline and two follow-up surveys), administrative data and interviews of teachers and school principals. Results indicate that students’ financial knowledge, attitudes and graduation rates improved for those receiving the financial education course, and that parents’ financial knowledge and behaviour also improved when their children had attended such course. Results on students’ short-term financial behaviours were more nuanced, with positive treatment effects on some key areas of focus of the programme, such as saving for purchases, money management and budgeting, but also an increase in borrowing, late credit repayments and use of expensive financial products among students who had attended the financial education course (Bruhn et al., 2013[12]; Bruhn et al., 2016[13]).

Combining the experiment data with administrative datasets housed at the Brazilian Central Bank (BCB), Bruhn et al. (2022[14]) show long-term behavioural effects by building a panel following 16 000 students for nine years after the intervention. In the long term, treatment students were less likely to borrow from expensive sources and to have loans with late payments than control students. The programme also affected students’ occupational choice, steering them from working as formal employees towards entrepreneurship, which was one of the topics covered in the programme. A high proportion of students also acquired accounts in the financial system in the two years after starting high school, indicating that high school may be a teachable moment to ensure long-run effects.

Since the first study in 2010, financial education has increasingly been taught in schools in Brazil, thanks notably to the Aprender Valor programme promoted by the BCB. This is a nationwide initiative aiming to improve the financial literacy of primary and secondary school students through classroom projects integrating financial education within other subjects such as mathematics, Portuguese or human sciences. The programme offers three major elements: online training for teachers and other education professionals, school projects, which are ready-to-use materials to be used by teachers in class, and learning assessments through entry and exit tests, i.e. an assessment of financial literacy levels before and after the programme. In 2022, an external partner carried out an impact evaluation of the Aprender Valor programme in schools to assess how much both the training for teachers and the school projects actually affected students’ financial literacy levels. A representative sample of 783 schools was selected and divided into a treatment and control group. The data showed that students from schools that participated in the programme presented a more significant evolution in their financial literacy (Banco Central do Brasil, 2024[15]).

Evidence from experiments among about 20 000 pupils attending primary, lower secondary and high schools in Italy showed that financial education lessons in class improved financial knowledge among children, and that improvements were still observed one year after the lesson (Romagnoli and Trifilidis, 2013[16]). In this study, financial education was integrated in other school subjects and voluntary teachers received a specific training prepared by the Bank of Italy. Additionally, a study comparing financial education delivery methods among 403 first-year university students studying mathematics showed that students receiving both in-class and online courses in financial education improved their levels of financial knowledge (Agasisti et al., 2023[17]).

A study using a RCT among about 20 000 students in 300 high schools in Peru showed that in-class financial education improved children’s levels of financial knowledge as well as their financial behaviour. Improvements in financial behaviour were also observed three years after the course, showing the potential long-lasting impact of financial education for children (Frisancho, 2023[18]). The same data was used to study possible spillover effects from financial education programmes on parents’ behaviour. In particular, parents in disadvantaged households whose children received a financial education course improved their credit scores by 5% and reduced their default probabilities by 26% on average (Frisancho, 2023[19]).

Using an RCT, a study among about 3 000 students in 78 public and private high schools in Spain showed that those receiving a 10-hour financial education course improved their financial knowledge and financial behaviour, as well as their attitudes toward saving in an incentivised task. The course focused on saving, budgeting, responsible consumption, bank accounts and investment through pension funds and insurance companies. The share of students who reported talking about economies with their parents also increased among those having received the course, suggesting an increased awareness of or interest in matters related to money (Bover, Hospido and Villanueva, 2018[4]).

Table IV.5.1. Students’ self-reported exposure to financial literacy in school chapter figures

|

Figure IV.5.1 |

Students’ self-reported exposure to financial terms in school |

|

Figure IV.5.2 |

Students’ self-reported exposure to financial literacy tasks in school lessons |

|

Figure IV.5.3 |

Students’ self-reported exposure to financial literacy tasks in different types of classes or activities |

|

Figure IV.5.4 |

Financial literacy performance, by students’ self-reported exposure to financial terms in school |

References

[17] Agasisti, T. et al. (2023), “Online or on-campus? Analysing the effects of financial education on student knowledge gain”, Evaluation and Program Planning, Vol. 98, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2023.102273.

[10] Amagir, A. et al. (2018), A review of financial-literacy education programs for children and adolescents, SAGE Publications Inc., https://doi.org/10.1177/2047173417719555.

[8] Aristei, D. and M. Gallo (2022), “Assessing gender gaps in financial knowledge and self-confidence: Evidence from international data”, Finance Research Letters, Vol. 46, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2021.102200.

[15] Banco Central do Brasil (2024), Report on Social, Environmental and Climate-related Risks and Opportunities v.3, https://www.bcb.gov.br/acessoinformacao/faleconosco.

[1] Becchetti, L., S. Caiazza and D. Coviello (2013), “Financial education and investment attitudes in high schools: Evidence from a randomized experiment”, Applied Financial Economics, Vol. 23/10, pp. 817-836, https://doi.org/10.1080/09603107.2013.767977.

[6] Beyer, S. and E. Bowden (1997), “Gender differences in self-perceptions: Convergent evidence from three measures of accuracy and bias”, Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, Vol. 23/2, pp. 157-172, https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167297232005.

[4] Bover, O., L. Hospido and E. Villanueva (2018), The Impact of High School Financial Education on Financial Knowledge and Choices: Evidence from a Randomized Trial in Spain, http://www.iza.org.

[12] Bruhn, M. et al. (2013), The Impact of High School Financial Education Experimental Evidence from Brazil, http://econ.worldbank.

[14] Bruhn, M. et al. (2022), The Long-Term Impact of High School Financial Education Evidence from Brazil, http://www.worldbank.org/prwp.

[13] Bruhn, M. et al. (2016), “The impact of high school financial education: Evidence from a large- scale evaluation in Brazil”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, Vol. 8/4, pp. 256-295, https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20150149.

[5] Coda Moscarola, F. and A. Kalwij (2021), “The Effectiveness of a Formal Financial Education Program at Primary Schools and the Role of Informal Financial Education”, Evaluation Review, Vol. 45/3-4, pp. 107-133, https://doi.org/10.1177/0193841X211042515.

[18] Frisancho, V. (2023), “Is School-Based Financial Education Effective? Immediate and Long-Lasting Impacts on High School Students”, The Economic Journal, Vol. 133/651, pp. 1147-1180, https://doi.org/10.1093/ej/ueac084.

[19] Frisancho, V. (2023), Spillover Effects of Financial Education: The Impact of School-based Programs on Parents, http://www.iadb.org.

[3] Frisancho, V. (2020), “The impact of financial education for youth”, Economics of Education Review, Vol. 78, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2019.101918.

[9] Frisancho, V. (2018), The Impact of School-Based Financial Education on High School Students and Their Teachers: Experimental Evidence from Peru, http://www.iadb.org.

[7] Herbst, T. (2020), “Gender differences in self-perception accuracy: The confidence gap and women leaders’ underrepresentation in academia”, SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, Vol. 46, https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v46i0.1704.

[2] Kaiser, T. and L. Menkhoff (2020), “Financial education in schools: A meta-analysis of experimental studies”, Economics of Education Review, Vol. 78, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2019.101930.

[11] OECD (2020), Recommendation of the Council on Financial Literacy.

[16] Romagnoli, A. and M. Trifilidis (2013), Does financial education at school work? Evidence from Italy.

Notes

← 1. The index of familiarity with concepts of finance therefore takes values between 0 and 16.

← 2. Students in Saudi Arabia were not asked about citizenship classes, and students in Norway were not asked about economics or business classes.

← 3. In PISA, advantaged students are defined as those in the top quarter (25%) of the distribution of socio-economic status in their country or economy, as measured by the PISA index of economic, social and cultural status (ESCS). Disadvantaged students are defined as those in the bottom quarter of this distribution.

← 4. Advantaged schools are those in the top quarter (25%) of the distribution of school socio-economic profile in their country or economy. The school socio-economic profile was measured as the average ESCS of the students in the school. Disadvantaged schools are defined as those in the bottom quarter of this distribution.

← 5. Although caution should be used when interpreting results for the Canadian provinces* and the United Arab Emirates, as there were too few observations to provide reliable estimates, according to PISA methodology.

← 6. For the sake of this analysis, the category of students who reported that they had not seen such tasks in this class/activity includes students who reported that they do not know whether they had seen such tasks in this class/activity, and students who reported that they do not have this class/ activity.