This chapter explores the levels of financial literacy of students in participating countries and economies in 2022. It presents the various levels of proficiency in financial literacy that students exhibited. The chapter examines trends in students’ performance in financial literacy and compares their performance in financial literacy to their performance in the core PISA subjects. The chapter concludes by proposing a framework for comparing countries’ and economies’ performance in financial literacy.

PISA 2022 Results (Volume IV)

2. Students’ performance in financial literacy in PISA 2022

Abstract

What the data tell us

Austria, the Flemish community of Belgium, the Canadian provinces*, Czechia, Denmark*, the Netherlands* and Poland performed above the OECD average in financial literacy.

Some 11% of students on average across OECD countries and economies were top performers in financial literacy, meaning that they were proficient at Level 5. These students can analyse complex financial products and solve non-routine financial problems. They show an understanding of the wider financial landscape, such as the implication of income-tax brackets and can explain the financial advantages of different types of investments. Some 19% of students in the Netherlands*, 16% of students in the Flemish community of Belgium and around 15% of students in the Canadian provinces* displayed Level 5 proficiency.

On average across OECD countries and economies, 18% of students performed at or below Level 1. The percentage of students performing at or below Level 1 was larger than 40% in Brazil, Bulgaria, Costa Rica, Malaysia, Peru and Saudi Arabia, and was 39% in the United Arab Emirates. These students can, at best, recognise the difference between needs and wants, make simple decisions about everyday spending, and recognise the purpose of everyday financial documents, such as an invoice.

Among the countries that have participated in all PISA financial literacy assessments, Italy improved its performance in 2022 compared to 2012, and Spain and the United States* improved their performance in 2022 compared to 2015. Poland improved its performance in 2022 compared to 2015, even if it performed worse than in 2018.

Some 20% of the variation in performance in financial literacy, on average across OECD countries and economies, was independent of performance in the mathematics and reading assessments, meaning that this variation was related to other factors, that may include competences uniquely related to financial literacy.

Average performance in financial literacy

In 2022, the mean financial literacy score across the 14 OECD countries and economies was 498 points, while the mean financial literacy score across the 20 participating countries and economies was 475 points.

Table IV.2.1 shows each country’s and economy’s mean score and indicates for which pairs of countries and economies the differences between the means are statistically significant. When comparing mean performance across countries and economies, only those differences that are statistically significant should be considered. For each country and economy shown in the middle column, the countries and economies whose mean scores are not statistically significantly different are listed in the right column. For example, the mean performance of students in the Flemish community of Belgium cannot be distinguished from that of students in Denmark* and the Netherlands*; and the mean performance of students in Norway cannot be distinguished from that of students in Hungary, Italy, Portugal and Spain with certainty.

Table IV.2.1 also divides countries and economies into three broad groups: those whose mean scores are statistically around the OECD mean (highlighted in white); those whose mean scores are above the OECD mean (highlighted in blue); and those whose mean scores are below the OECD mean (highlighted in grey).

Austria, the Flemish community of Belgium, the Canadian provinces*, Czechia, Denmark*, the Netherlands* and Poland performed above the OECD average in financial literacy. The mean performance in three countries – Hungary, Portugal and the United States*– was not statistically significantly different from the OECD average. Finally, 10 countries – Brazil, Bulgaria, Costa Rica, Italy, Malaysia, Norway, Peru, Saudi Arabia, Spain and the United Arab Emirates– performed below the OECD average in financial literacy.

Table IV.2.1. Comparing countries’ and economies’ mean performance in financial literacy

|

Mean score |

Comparison country/economy |

Countries and economies whose mean score is not statistically significantly different from the comparison country's/economy's score |

|---|---|---|

|

527 |

Flemish community of Belgium |

Denmark*, Netherlands* |

|

521 |

Denmark* |

Flemish community of Belgium, Canadian provinces*, Netherlands* |

|

519 |

Canadian provinces* |

Denmark*, Netherlands* |

|

517 |

Netherlands* |

Flemish community of Belgium, Denmark*, Canadian provinces*, United States* |

|

507 |

Czechia |

Austria, Poland, United States* |

|

506 |

Austria |

Czechia, Poland, United States* |

|

506 |

Poland |

Czechia, Austria, United States* |

|

505 |

United States* |

Netherlands*, Czechia, Austria, Poland |

|

494 |

Portugal |

Hungary, Norway |

|

492 |

Hungary |

Portugal, Norway, Spain |

|

489 |

Norway |

Portugal, Hungary, Spain, Italy |

|

486 |

Spain |

Hungary, Norway, Italy |

|

484 |

Italy |

Norway, Spain |

|

441 |

United Arab Emirates |

|

|

426 |

Bulgaria |

Peru, Costa Rica |

|

421 |

Peru |

Bulgaria, Costa Rica, Brazil |

|

418 |

Costa Rica |

Bulgaria, Peru, Brazil, Saudi Arabia |

|

416 |

Brazil |

Peru, Costa Rica, Saudi Arabia |

|

412 |

Saudi Arabia |

Costa Rica, Brazil, Malaysia |

|

406 |

Malaysia |

Saudi Arabia |

Statistically significantly above the OECD average

Statistically significantly above the OECD average

Not statistically significantly different from the OECD average

Not statistically significantly different from the OECD average

Statistically significantly below the OECD average

Statistically significantly below the OECD average

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 Database.

The gap in financial literacy performance between the highest- and lowest-performing OECD countries and economies was 108 points, and the difference between the highest- and lowest-performing countries and economies that took part in the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment was 12% larger (121 points). These gaps represent marked differences in the ability of 15-year-olds to make informed financial decisions.

The goal of PISA is to provide useful information to educators and policy makers concerning the strengths and weaknesses of their country’s education system, the progress made over time, and opportunities for improvement. When placing countries and economies in PISA, it is important to consider the social and economic context in which education takes place. Moreover, many countries and economies score at similar levels; small differences that are not statistically significant or practically meaningful should not be emphasised.

Table IV.2.2 shows, for each country and economy, an estimate of where its mean performance ranks amongst all other countries and economies that participated in PISA as well as, for OECD countries and economies, amongst all OECD countries and economies. Because mean-score estimates are derived from samples and are thus associated with statistical uncertainty, it is often not possible to determine an exact ranking for all countries and economies. However, it is possible to identify the range of possible rankings for a country’s or economy’s mean performance.1 The range of ranks can be wide, particularly for countries and economies whose mean scores are similar to those of many other countries and economies.

Table IV.2.2. Financial literacy performance of 15-year-old students at the national level

|

|

Financial literacy scale |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Mean score |

95% confidence interval |

Range of ranks |

|||

|

|

All countries/economies |

OECD countries/economies |

||||

|

|

Upper rank |

Lower rank |

Upper rank |

Lower rank |

||

|

Flemish community of Belgium |

527 |

520 - 533 |

1 |

4 |

1 |

4 |

|

Denmark* |

521 |

516 - 525 |

1 |

5 |

1 |

5 |

|

Canadian provinces* |

519 |

514 - 523 |

1 |

6 |

1 |

5 |

|

Netherlands* |

517 |

508 - 526 |

1 |

8 |

1 |

8 |

|

Czechia |

507 |

502 - 511 |

4 |

8 |

4 |

8 |

|

Austria |

506 |

501 - 512 |

3 |

10 |

4 |

9 |

|

Poland |

506 |

501 - 511 |

4 |

10 |

4 |

9 |

|

United States* |

505 |

496 - 515 |

2 |

12 |

2 |

11 |

|

Portugal |

494 |

490 - 499 |

6 |

13 |

6 |

13 |

|

Hungary |

492 |

486 - 499 |

6 |

13 |

8 |

13 |

|

Norway |

489 |

484 - 494 |

8 |

13 |

8 |

13 |

|

Spain |

486 |

481 - 491 |

8 |

13 |

9 |

13 |

|

Italy |

484 |

477 - 490 |

9 |

13 |

9 |

13 |

|

United Arab Emirates |

441 |

438 - 444 |

14 |

14 |

||

|

Bulgaria |

426 |

419 - 433 |

15 |

19 |

||

|

Peru |

421 |

415 - 427 |

15 |

19 |

||

|

Costa Rica |

418 |

412 - 424 |

15 |

20 |

14 |

14 |

|

Brazil |

416 |

411 - 420 |

15 |

20 |

||

|

Saudi Arabia |

412 |

407 - 418 |

15 |

20 |

||

|

Malaysia |

406 |

400 - 412 |

17 |

20 |

||

Note: Range-of-rank estimates are computed based on mean and standard-error-of-the-mean estimates for each country or economy, and take into account multiple comparisons amongst countries and economies at similar levels of performance. For an explanation of the method, see Annex A3.

Countries and economies are ranked in descending order of mean financial literacy performance.

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 Database, Table IV.B1.2.1.

Financial literacy is a life-long objective and while findings from PISA may help policy makers identify areas where 15-year-old students’ financial literacy may need to be reinforced, it is important to have a holistic picture of the financial literacy levels of countries and economies’ populations as a whole. Several of the countries taking part in the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment also assessed the financial literacy levels of their adult population in 2022/2023 as part of a co-ordinated data collection exercise conducted by the OECD International Network on Financial Education (OECD/INFE) (Box IV.2.1). Results from both exercises may be analysed in conjunction when identifying financial literacy priorities for each country and economy.

Box IV.2.1. OECD/INFE International Survey of Adult Financial Literacy

The OECD/INFE conducted an international data-collection exercise in 2022/2023 to measure the financial literacy of adults aged 18 to 79. The survey also explored aspects of digital financial literacy, financial resilience and financial well-being. Over 68 000 people from 39 countries and economies around the world participated in the survey. This co-ordinated measurement exercise follows from previous data collections carried out in 2015/2016 and 2019/2020 using the OECD/INFE survey instrument (OECD, 2022[1]). The results provide insights into aspects of financial knowledge, attitudes, behaviours and allow for international comparison.

The 2023 OECD/INFE International Survey of Adult Financial Literacy asked a series of questions aimed at measuring financial knowledge, covering topics such as the time-value of money, interest, inflation and risk diversification. Results of the survey show that, on average across the 20 participating OECD countries, 58% of adults could correctly answer at least five out of seven financial knowledge questions, compared to 50% of adults across all participating countries. Amongst the countries that also participated in the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment, less than 50% of adults in Brazil (26%), Costa Rica and Peru (36% respectively), Italy (39%), Saudi Arabia (45%) and Portugal (48%) could correctly answer at least five out of seven questions, while 75% of adults in Hungary, 68% in Poland, 59% in the Netherlands*, 54% in Malaysia, and 52% of adults in Spain could do so. Comparisons with PISA findings should be made with caution, as the evidence is drawn from different measurement tools and on different age groups; but any differences in country rankings across adults and young people might suggest a considerable generational divide in some countries.

Source: OECD/INFE (2023[2]), OECD/INFE 2023 International Survey of Adult Financial Literacy, https://www.oecd.org/publications/oecd-infe-2023-international-survey-of-adult-financial-literacy-56003a32-en.htm.

The range of proficiency covered by the PISA financial literacy assessment

The mean scores described in the previous section allow for comparisons of proficiency in financial literacy between students in one country or economy and those in another country or economy, but they do not identify the specific types of financial tasks that students are capable of accomplishing. To do so, the financial literacy scale was divided into a range of proficiency levels: Levels 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5, in increasing order of proficiency. These levels were also used in PISA 2012, 2015 and 2018. The score cut-offs between proficiency levels did not change over successive assessments.

Proficiency scales not only describe student performance; they also describe the difficulty of the tasks presented to students in the assessment (see Annex C). The description of what students at each proficiency level can do and of the typical features of tasks at each level (Table IV.2.3) were obtained from an analysis of the tasks located at each proficiency level. However, there is much overlap between the descriptions, and items classified in one proficiency level may also exhibit properties similar to those of items in neighbouring proficiency levels.

Table IV.2.3. Summary description of the five levels of financial literacy proficiency in PISA 2022

|

Level |

Lower score limit |

Percentage of students able to perform tasks at each level or above (OECD average) |

What students can typically do |

|---|---|---|---|

|

5 |

625 |

10.6 |

Students can apply their understanding of a wide range of financial terms and concepts to contexts that may only become relevant to their lives in the long term. They can analyse complex financial products and can take into account features of financial documents that are significant but unstated or not immediately evident, such as transaction costs. They can work with a high level of accuracy and solve non-routine financial problems, and they can describe the potential outcomes of financial decisions, showing an understanding of the wider financial landscape, such as income tax. |

|

4 |

550 |

32.0 |

Students can apply their understanding of less common financial concepts and items to contexts that will be relevant to them as they move towards adulthood, such as bank account management and compound interest in savings products. They can interpret and evaluate a range of detailed financial documents, such as bank statements, and explain the functions of less commonly used financial products. They can make financial decisions taking into account longer-term consequences, such as understanding the overall cost implication of paying back a loan over a longer period, and they can solve routine problems in less common financial contexts. |

|

3 |

475 |

59.6 |

Students can apply their understanding of commonly used financial concepts, terms and products to situations that are relevant to them. They begin to consider the consequences of financial decisions and they can make simple financial plans in familiar contexts. They can make straightforward interpretations of a range of financial documents and can apply a range of basic numerical operations, including calculating percentages. They can choose the numerical operations needed to solve routine problems in relatively common financial literacy contexts, such as budget calculations. |

|

2 |

400 |

82.1 |

Students begin to apply their knowledge of common financial products and commonly used financial terms and concepts. They can use given information to make financial decisions in contexts that are immediately relevant to them. They can recognise the value of a simple budget and can interpret prominent features of everyday financial documents. They can apply single basic numerical operations, including division, to answer financial questions. They show an understanding of the relationships between different financial elements, such as the amount of use and the costs incurred. |

|

1 |

326 |

95.0 |

Students can identify common financial products and terms and interpret information relating to basic financial concepts. They can recognise the difference between needs and wants and can make simple decisions on everyday spending. They can recognise the purpose of everyday financial documents, such as an invoice, and apply single and basic numerical operations (addition, subtraction or multiplication) in financial contexts that they are likely to have experienced personally. |

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 Database, Table IV.B1.2.2.

Table IV.2.4 presents the difficulty level of several released items from the current and past PISA financial literacy assessments; these items were used in either the field trial or the main study in PISA 2012, 2015, 2018 or 2022. These items are presented in full in Annex C.

Table IV.2.4. Map of selected financial literacy questions, illustrating the proficiency levels

|

Level |

Lower score limit |

Question |

Question difficulty (in PISA score points) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

5 |

625 |

BANK ERROR – Question 1 |

797 |

|

INVOICE – Question 3 (for full credit) |

660 |

||

|

BANK STATEMENT – Question 2 (for full or partial credit) |

N/A |

||

|

ZCYCLE – Question 2 (for full or partial credit) |

|

||

|

ZCYCLE – Question 4 |

|

||

|

4 |

550 |

NEW OFFER – Question 2 |

582 |

|

PAY SLIP – Question 1 |

551 |

||

|

MUSIC SYSTEM |

N/A |

||

|

BANK STATEMENT – Question 1 |

|

||

|

RINGTONES |

|

||

|

MOTORBIKE INSURANCE – Question 1 |

|

||

|

ONLINE SHOPPING |

|

||

|

ZCYCLE – Question 1 |

|

||

|

ZCYCLE – Question 3 (for full credit) |

|

||

|

3 |

475 |

INVOICE – Question 3 (for partial credit) |

547 |

|

MOTORBIKE INSURANCE – Question 1, Part 3 |

494 |

||

|

COSTS OF RUNNING A CAR |

N/A |

||

|

PHONE PLANS – Question 1 |

|

||

|

PHONE PLANS – Question 2 |

|

||

|

ZCYCLE – Question 3 (for partial credit) |

|

||

|

NEW BIKE - Question 1 (for full credit) |

|

||

|

2 |

400 |

SELLING ONLINE |

471 |

|

INVOICE – Question 2 |

461 |

||

|

AT THE MARKET – Question 2 |

459 |

||

|

MOBILE PHONE CONTRACT |

N/A |

||

|

NEW BIKE - Question 1 (for partial credit) |

|

||

|

CHARITABLE GIVING |

|

||

|

1 |

326 |

AT THE MARKET – Question 3 |

398 |

|

NEW BIKE - Question 2 |

372 |

||

|

INVOICE – Question 1 |

360 |

Performance of students at the different levels of financial literacy proficiency

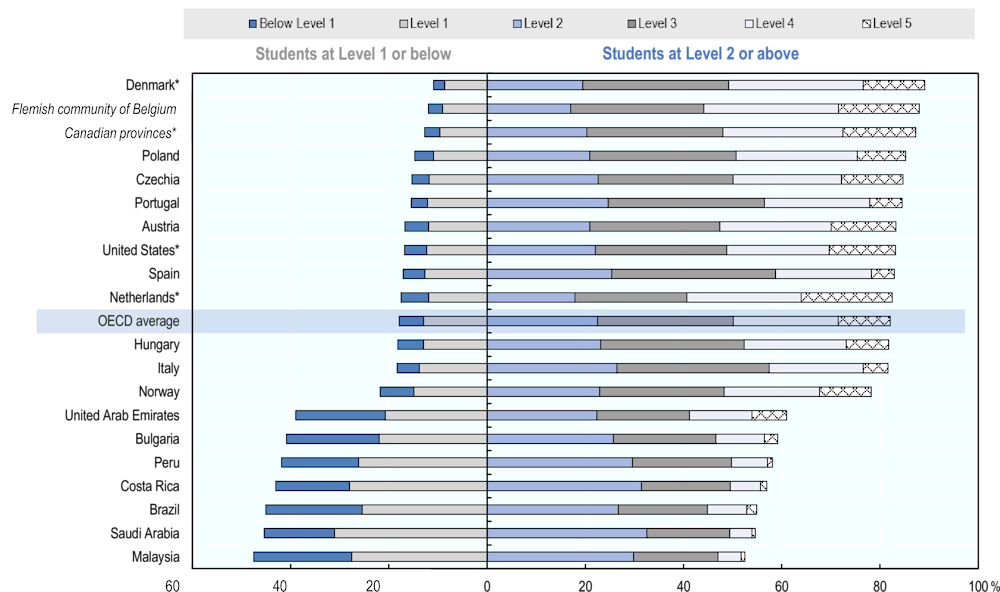

Figure IV.2.1 presents the distribution of students across the five levels of financial literacy proficiency. The percentage of students performing at Level 1 or below in PISA 2022 is shown on the left side of the vertical axis.

Figure IV.2.1. Percentage of students at each level of proficiency in financial literacy

Percentage of students at the different levels of financial literacy proficiency

Countries and economies are ranked in descending order of the percentage of students who perform at or above Level 2.

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 Database, Table IV.B1.2.2.

While the distribution of students across financial literacy proficiency levels shows wide variation in performance within countries and economies, data from the PISA financial literacy questionnaire show that all students have a relatively high self-assessment of their financial skills, including top and low performers (Box IV.2.2).

Box IV.2.2. Students’ self-assessed financial skills compared to their performance in financial literacy

The PISA 2022 financial literacy questionnaire asked students to self-assess their level of financial skills by indicating whether they strongly agreed, agreed, disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement: “I know how to manage my money”.

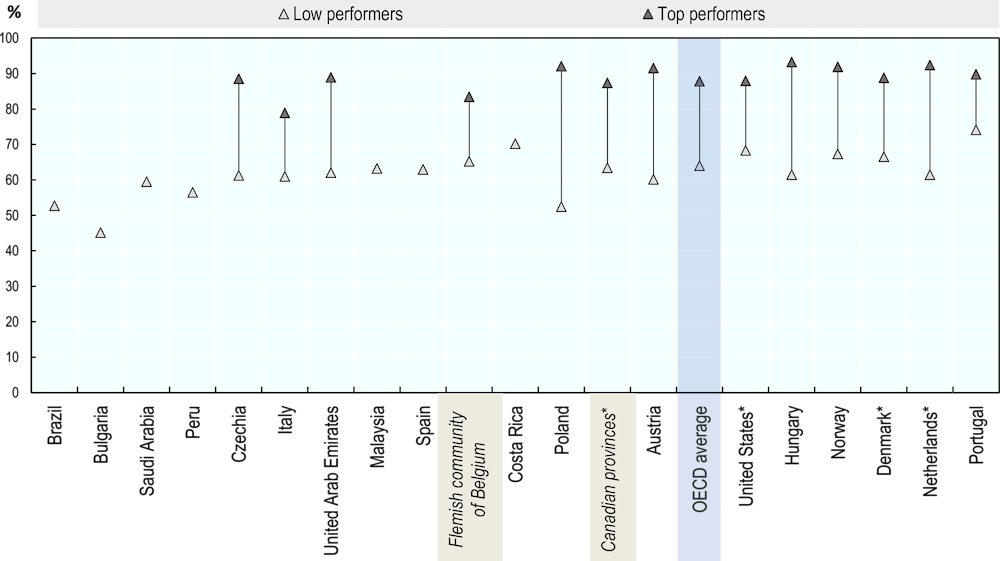

Figure IV.2.2. Financial literacy performance and students’ self-assessed financial skills

Percentage of students who agreed or strongly agreed with the statement "I know how to manage my money"

Note: The value for top performers is shown only for countries and economies with at least 5% of top performers.

Countries and economies are ranked in ascending order of the percentage of all students.

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 Database, Table IV.B1.2.10.

Figure IV.2.2 shows not only that top performing students have a higher self-assessment of their own financial skills than low performing students, but also that many low performers think that they know how to manage their money. On average across OECD countries and economies, 64% of low performers in financial literacy think that they know how to manage their money. The percentage of low performing students who agreed that they know how to manage their money ranged from 45% in Bulgaria to 74% in Portugal (Table IV.B1.2.10).*

Being a low performer in the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment and knowing how to manage one’s money may not necessarily be contradictory, given the relatively simple personal finances of students at age 15. However, low performing students with a high self-assessment of their financial skills may need to be supported even more than their peers with a more realistic self-assessment to develop the necessary financial literacy skills to successfully manage their finances in the future.

Note: * Results should be interpreted with caution due to the limited number of observations in many countries and economies, as indicated in Table IV.B1.2.10.

Proficiency at Level 1

Students proficient at Level 1 display basic financial literacy skills. They can identify common financial products and terms, and interpret information related to basic financial concepts, such as recognising the purpose of an invoice (see released item INVOICE – Question 1 for example) or an insurance contract (see released item NEW BIKE- Question 2). They can recognise the difference between needs and wants, and they can make simple decisions on everyday spending, such as recognising value by comparing prices per unit. Students at this level can also apply basic single numerical operations, such as additions, subtractions or multiplications, in financial contexts that they are likely to have personally experienced.

Tasks at Level 1 require students to identify and recognise basic financial concepts and knowledge. These tasks are prerequisites for applying knowledge to real-life situations, which is required for tasks at Level 2 and higher. Students performing at or below Level 1 are not yet able to apply their knowledge to real-life situations involving financial issues and decisions.

On average across the 14 OECD countries and economies that participated in the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment, 95% of students were proficient at Level 1 or higher; on average across all 20 participating countries and economies, this percentage fell to 91%.

At the other end of the performance spectrum, between 40% and 50% of students in Brazil, Bulgaria, Costa Rica, Malaysia, Peru and Saudi Arabia performed at Level 1 or below in financial literacy; and between 30% and 40% of students in the United Arab Emirates. These countries all have much to do in order to equip their students with the ability to make responsible financial decisions in unfamiliar or more complex contexts. In no country was Level 1 the most commonly observed level of proficiency (Figure IV.2.1).

Proficiency at Level 2

Students at proficiency Level 2 begin to apply their knowledge to make financial decisions in contexts that are immediately relevant to them. They can recognise the value of a simple budget and can undertake a simple assessment of value-for-money, choosing between buying tomatoes by the kilogram or by the box, (see released item AT THE MARKET – Question 2 for example). Students at this level can also apply basic single numerical operations to answer financial questions and can show an understanding of the relationships between different financial elements. These skills are essential for full participation in society as independent and responsible citizens. Beyond their direct relevance and relationship with basic skills in other subjects, like mathematics and reading, these financial literacy skills may also be related to other competencies that are becoming increasingly important, such as critical thinking (see released item SELLING ONLINE, for example) and problem solving. Proficiency Level 2 can be considered as a minimum or “baseline” level, below which students may need support in order to answer questions in financial literacy. However, it is neither a starting point from which individuals develop their competency in this subject nor the ultimate goal.

On average across OECD countries and economies, 82% of students, were proficient at Level 2 or higher; this fell to 74% when considering all countries and economies that participated in the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment. Over 85% of students in the Flemish community of Belgium, the Canadian provinces*, Denmark* and Poland displayed at least Level 2 proficiency. In contrast, just over half (53%) of students in Malaysia were proficient at Level 2 or higher in financial literacy; meaning that close to one in two students in Malaysia have the basic skills involved in making responsible and well-informed financial decisions (Figure IV.2.1).

Some 23% of students were proficient at Level 2, on average across OECD countries and economies. This was the most common proficiency level observed in Brazil, Bulgaria, Costa Rica, Malaysia, Peru, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (Figure IV.2.1).

Proficiency at Level 3

Tasks at proficiency Level 3 require students to apply their knowledge of commonly used financial concepts, terms and products to situations that are relevant to them. Students at this level begin to consider the consequences of financial decisions, and they make simple financial plans in common contexts, such as comparing the financial benefits of borrowing money with different interest rates and repayment schedules, or planning a budget based on the amount of use and the costs incurred (see released item COSTS OF RUNNING A CAR for example). They can make straightforward interpretations of a range of financial documents, such as invoices and pay slips, and can apply a range of basic numerical operations, such as those involved in making budget calculations. Students at Level 3 can also choose the numerical operations needed to solve routine problems in relatively common financial literacy contexts. Therefore, they show not only a capacity to use mathematical tools but also to choose the tools that are most applicable to the financial tasks at hand.

On average across OECD countries and economies, 60% of students attained at least Level 3 in the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment; on average across all participating countries and economies, 50%, or just over half, of the student population attained at least this level. Over 70% of students were able to perform at this level or above in the Flemish community of Belgium, as were over 50% of students in a further 12 countries. However, only around one in five students in Saudi Arabia (22%) and Malaysia (23%) displayed at least Level 3 proficiency, as did less than 30% of students in Brazil, Costa Rica and Peru (Figure IV.2.1).

Some 28% of students were proficient at Level 3, on average across OECD countries and economies. Level 3 was the most commonly observed proficiency level in more than half of the countries and economies that participated in the financial literacy assessment, namely Austria, the Canadian provinces*, Czechia, Denmark*, Hungary, Italy, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Spain and the United States*. Indeed, the performance of over 30% of 15-year-old students in Italy, Portugal and Spain fell into Level 3 (Figure IV.2.1).

Proficiency at Level 4

Students who perform at proficiency Level 4 apply their knowledge of less common financial concepts and terms to contexts that will be relevant to them as they move into adulthood. Students at this level can interpret and evaluate a range of detailed financial documents and explain the functions of less commonly used financial products. They can also make financial decisions while considering their longer-term consequences, and can solve routine problems in perhaps unfamiliar financial contexts.

Tasks at Level 4 require an understanding of financial concepts and terms that are likely to be less commonly known amongst students, such as bank account management and compound interest (i.e. the process of earning or paying interest on interest). Students need to show that they understand that the simple interest rate should be applied to both the original amount saved or borrowed and the interest that has been added to an account. Tasks at this level also involve contexts that are not necessarily familiar to 15-year-old students but that will become relevant to them in their near future, such as understanding pay slips. These tasks also require an ability to identify the possible consequences of financial decisions (see released item RINGTONES for example), and to choose financial products based on those consequences, such as deciding between two loan offers with different terms and conditions (see released item MUSIC SYSTEM for example).

Almost one-third (32%) of all students performed at Level 4 or above, on average across OECD countries and economies, while about one-quarter (25%) of all students performed at Level 4 or above, on average across all participating countries and economies. This proportion reached over 40% in both the Flemish community of Belgium and the Netherlands*, and over 30% in Austria, the Canadian provinces*, Czechia, Denmark*, Poland and the United States*. By contrast, in Costa Rica, Malaysia, Peru and Saudi Arabia, fewer than one in ten students performed at Level 4 or above (Figure IV.2.1).

Some 21% of students performed at Level 4 (as opposed to Level 4 or above), on average across OECD countries and economies. In the Flemish community of Belgium, 27% of students performed at Level 4, making this proficiency level the most attained in this economy; Level 4 was also the most attained level in Netherlands*. Over 20% of students in 10 countries and economies (in addition to the Flemish community of Belgium and the Netherlands*, Austria, the Canadian provinces*, Czechia, Denmark*, Hungary, Poland, Portugal and the United States*,) displayed Level 4 proficiency in financial literacy (Figure IV.2.1).

Proficiency at Level 5

Students at Level 5 on the PISA financial literacy scale can successfully complete the most difficult items in this domain. Tasks at this level require students to apply their understanding of a wide range of financial terms and concepts to contexts that may only become relevant to their lives later on, such as borrowing money from loan providers. Students at this level can analyse complex financial products and take into account features of financial documents that are significant but unstated or not immediately evident, such as transaction costs. They can work with a high level of accuracy and solve non-routine financial problems, such as calculating the bank balance in a given bank statement considering multiple factors, such as transfer fees (see released item BANK STATEMENT – Question 2 for example).

The tasks at this level are related to students’ ability to look ahead and plan for the future, so as to solve financial problems or make the kinds of financial decisions that will be relevant to many of them in the future, regardless of the country or the context in which they live. Students who perform at Level 5 can describe the potential outcomes of financial decisions, showing an understanding of the wider financial landscape, such as income tax. These tasks relate to higher-order uses of knowledge and skills and can thus reinforce and are reinforced by other competencies, such as the use of a variety of mathematical operations and the ability to look ahead and plan for the future.

On average across OECD countries and economies, 11% of students were proficient at Level 5 in financial literacy; these students are referred to as top performers in financial literacy. On average across all countries and economies that participated in the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment, 8% of students were top performers (Figure IV.2.1). This proportion was higher than 15% in the Netherlands* (19%) and the Flemish community of Belgium (16%), and 15% of students in the Canadian provinces* were also top performers. However, less than 1% of students, or fewer than 1 in 100 students, in Malaysia and Saudi Arabia were top performers; less than 3% of students in another four countries and economies were top performers.

Trends in student performance in financial literacy

Financial literacy has now been assessed in PISA 2012, 2015, 2018 and 2022. Among countries and economies that participated in 2022, four countries and economies participated in all four assessments (Italy, Poland, Spain and the United States); another three participated in three assessments (the Flemish community of Belgium, Brazil and Peru); four countries and economies participated in two assessments (Bulgaria, Czechia, the Netherlands* and Portugal), and eight participated in 2022 for the first time (Austria, Costa Rica, Denmark*, Hungary, Malaysia, Norway, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates). Seven Canadian provinces* participated in 2015 and 2018, and an additional province (Alberta) also participated in 2022. Comparisons in this section are made between pairs of years using 2022 as a reference: either between 2012 and 2022, 2015 and 2022 or between 2018 and 2022.2 As not all countries and economies participated in all of the assessments, only those countries and economies with valid data in both years of a comparison are included when calculating trends in OECD average performance (for more information, see Box IV.2.3 and Annex A5).

Box IV.2.3. Comparing PISA results in financial literacy over time

To ensure the comparability of PISA results over time, successive assessments must include a sufficient number of common items so that results can be reported on a common scale. Some 24 of the 46 financial literacy items used in PISA 2022 were also used in the PISA 2012 assessment, while 27 of the 46 financial literacy items used in PISA 2022 were also used in PISA 2015 and 41 of the 46 items used in PISA 2022 were also used in PISA 2018. Moreover, the financial literacy assessment framework remained largely unchanged across the four assessments, and the common items adequately cover the different aspects of the framework.

With each cycle, PISA aims to measure the knowledge and skills that are required to participate fully in society and the economy. This includes making sure that the assessment instruments are aligned with new developments in assessment techniques and with the latest understanding of the cognitive processes underlying proficiency in each domain (see Annex A5 for full details on the changes implemented between successive PISA financial literacy assessments).

Changes between 2022 and previous cycles were limited, as illustrated by the link error, which quantifies the uncertainty around equating scales in different years. In other words, the link error measures the extent to which a score of 500 points in the PISA 2012, 2015 or 2018 financial literacy assessment is the same as a score of 500 points in the PISA 2022 assessment. (Scales are not automatically equivalent across years because different items, calibration samples, and sometimes even statistical models are used in different assessments.) The link error between the PISA 2012 and 2022 financial literacy assessments was 4.05 score points, while that between the PISA 2015 and 2022 financial literacy assessments was 3.47 score points and that between PISA 2018 and 2022 financial literacy assessments was 2.20 score points.

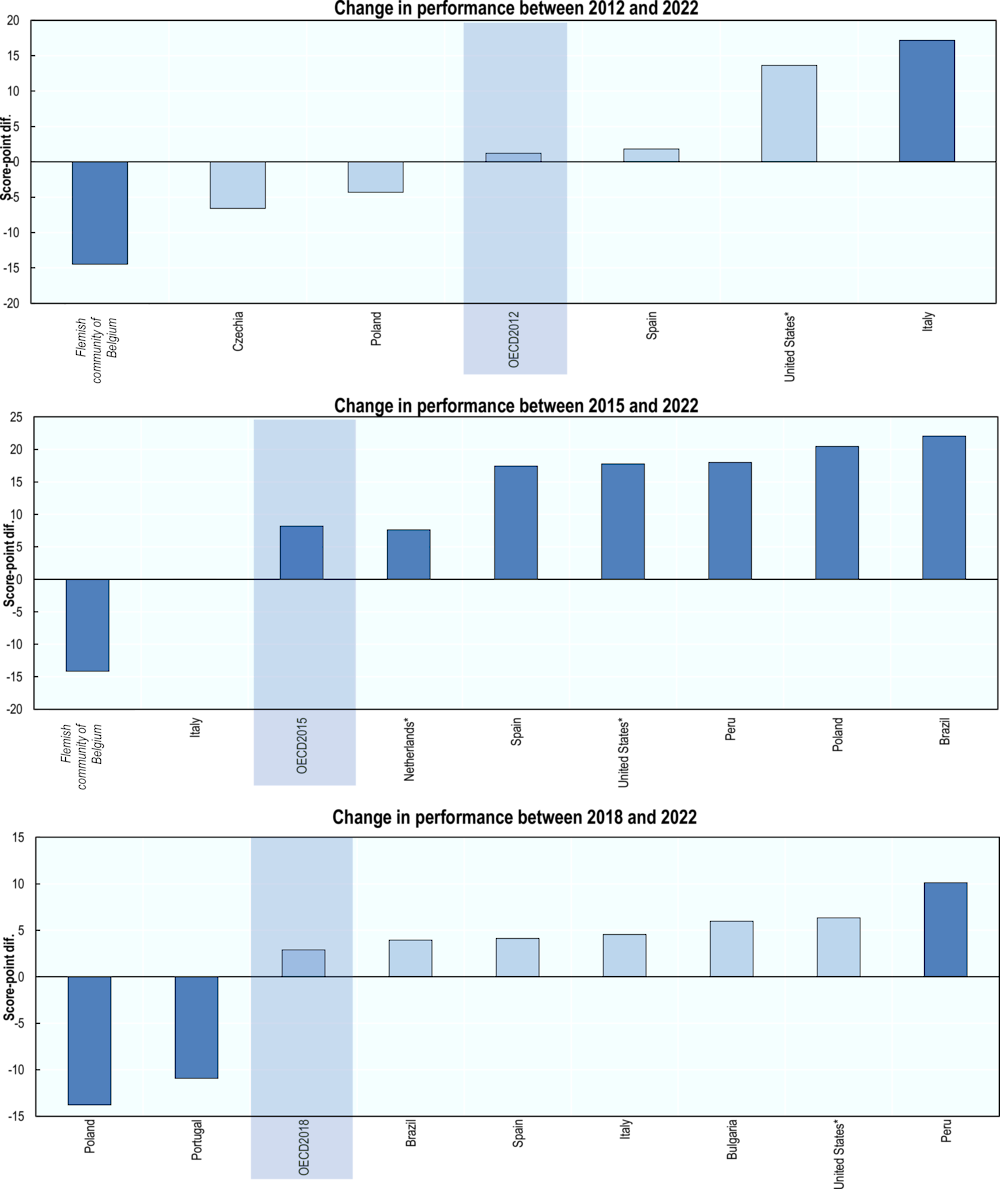

Trends in mean performance

On average across OECD countries with comparable data for 2012 and 2022, the average performance in financial literacy remained stable between the two assessments (Table IV.B1.2.1, Figure IV.2.3 and Figure IV.2.4). The average financial literacy performance increased by 8 score points (from 496 to 504) between 2015 and 2022 for OECD countries and economies with comparable data. On average across OECD countries and economies with comparable data for 2018 and 2022, mean performance did not change significantly between the two assessments.

The relatively limited differences in financial literacy performance between 2022 and previous cycles on average across OECD countries hide changes in opposite directions across different countries and economies. There was a significant change between 2012 and 2022 in mean financial literacy performance in only two of the six countries with data in both years: Italy, where mean performance improved by 17 score points, and the Flemish community of Belgium, where it declined by 14 score points. Between 2015 and 2022, performance in 5 of the 8 countries and economies with comparable data improved by over 17 score points (in Brazil, Poland, Peru, Spain and the United States*), while it decreased by 14 score points in the Flemish community of Belgium (Table IV.B1.2.1 and Figure IV.2.3). Between 2018 and 2022, there was a significant improvement in mean financial literacy performance in Peru (by 10 score points), whereas there was a significant decline in performance in Poland and Portugal, by between 11 and 14 score points.

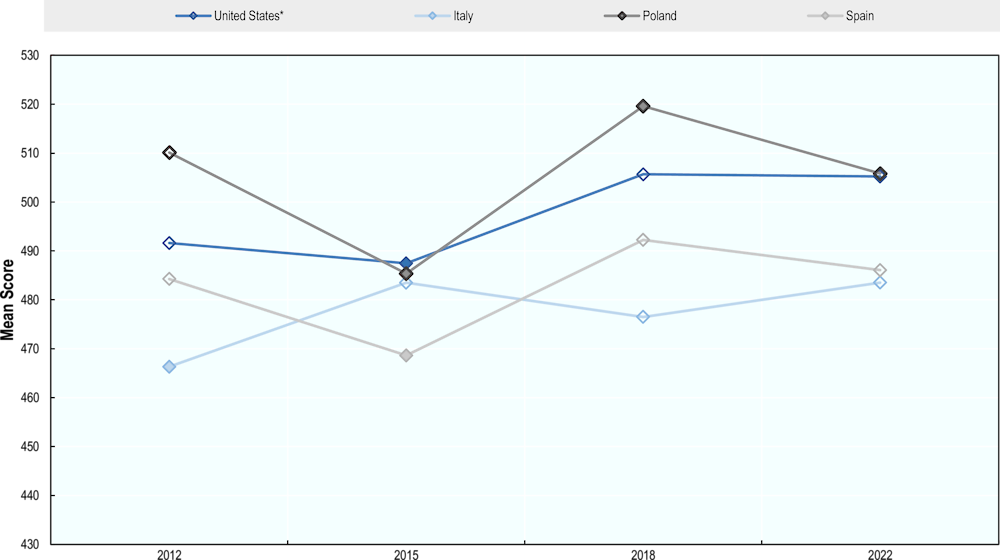

Figure IV.2.4 shows financial literacy mean scores across the four countries that have participated in all PISA financial literacy assessments. In 2022, Italy improved its performance compared to 2012 (by 17 points). Spain and the United States* improved their performance compared to 2015 (by 17 and 18 points respectively). Poland improved its performance in 2022 compared to 2015 (by 20 points) but performed worse in 2022 than in 2018 (by 14 points).

Figure IV.2.3. Changes across time in mean financial literacy performance

Notes: Statistically significant differences between PISA 2012/2015/2018 and PISA 2022 are shown in a darker tone (see Annex A3).

For Canadian provinces*, values for previous assessments are not reported in the trend tables due the different number of provinces participating in the 2022 financial literacy assessment compared to previous ones.

Countries and economies are ranked in descending order of the change in financial literacy performance between PISA 2012/2015/2018 and 2022.

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 Database, Table IV.B1.2.1.

Figure IV.2.4. Changes across time in mean financial literacy performance among countries that participated in all PISA financial literacy assessments

Notes: Only countries with available data since PISA 2012 are shown.

White dots indicate mean-performance estimates that are not statistically significantly different from PISA 2022 estimates (see Annex A3).

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 Database, Table IV.B1.2.1.

Trends in performance amongst low- and high-performing students

Changes in a country’s or economy’s average performance can result from changes at different levels in the performance distribution. For example, in some countries, the average score might have improved because the share of students scoring at the lowest levels on the financial literacy scale shrank (i.e. there was an improvement in performance amongst these students). In other countries, improvements in mean scores might have been the result of improvements in performance amongst the highest-achieving students and/or an increase in the share of students who scored at the highest levels.

Between 2012 and 2022, the increase in the mean financial literacy score of students in Italy (by 17 score points) is due to a higher proportion of students scoring at Level 5 (by 3 percentage points), whereas the 14-score point decrease in mean financial literacy score in the Flemish community of Belgium over the period comes from a 3-percentage point increase in the proportion of students scoring below Level 2. The increased proportion of students scoring at Level 5 in financial literacy in the United States* (by 4 percentage points), or in those scoring below Level 2 in Czechia and Poland does not translate into a significant change in mean financial literacy levels in these countries and economies (Table IV.B1.2.1 and Table IV.B1.2.5).

Between 2015 and 2022, improvements on both ends of the distribution in the United States* contributed to the 18-score point increase in the mean financial literacy score: 5 percentage points fewer students scored below Level 2, and 3 percentage points more students scored at Level 5. In Brazil, Peru, Poland and Spain, improvements in the mean performance over the period are due mostly to fewer students scoring below Level 2. By contrast, the 14 score-point decrease in mean financial literacy levels in the Flemish community of Belgium between 2015 and 2022 is explained by fewer students (8 percentage points) scoring at Level 5 (Table IV.B1.2.1 and Table IV.B1.2.5).

Between 2018 and 2022, the proportion of students scoring below Level 2 increased in Poland (5 percentage points), contributing to the 14-score point decrease in mean performance, while it decreased in Peru (5 percentage points), contributing to the 10-score point increase in mean performance (Table IV.B1.2.1 and Table IV.B1.2.5).

Student performance in financial literacy compared to performance in the core PISA subjects

Financial literacy is closely related to a variety of other subjects and domains of knowledge. The PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment allows users to explore the relationship between financial literacy performance and performance in mathematics and reading, as a certain level of numeracy and reading proficiency can be considered as pre-requisites for financial literacy (OECD, 2023[3]). Indeed, being proficient in financial literacy, or being able to manage one’s financial affairs, requires being able to understand a variety of generally written materials related to transactions and contracts. On a more practical level, the PISA assessment is conducted in a text-based format and students who struggle with reading are likely to struggle with understanding the material in the financial literacy assessment. Likewise, many financial decisions involve the manipulation of quantities of money or to perform basic numerical calculations, which necessarily requires a degree of mathematical literacy.

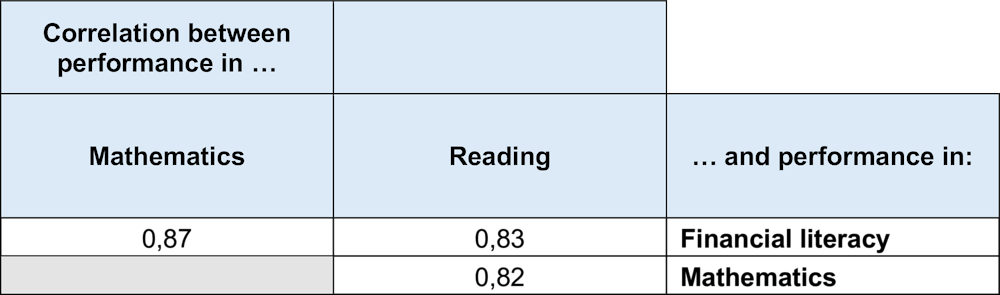

As shown in Figure IV.2.5, performance in the financial literacy, mathematics and reading assessments was highly correlated in PISA 2022. On average across OECD countries and economies, the correlation between financial literacy and mathematics performance was 0.87 and that between financial literacy and reading performance was 0.83. By comparison, the correlation between mathematics and reading performance was 0.82. These strong correlations were observed in every participating country and economy; indeed, the correlation between financial literacy and mathematics or reading performance was around 0.80 or higher in every participating country and economy (Table IV.B1.2.6).3

Figure IV.2.5. Correlation between performance in financial literacy, mathematics and reading

OECD average correlation, where 0.00 signifies no relationship and 1.00 signifies the strongest positive relationship

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 Database, Table IV.B1.2.6.

This correlation can also be observed in the patterns in which students were either top performers (having attained at least proficiency Level 5) or low achievers (not having attained at least proficiency Level 2) in financial literacy, mathematics and reading.4 Only 3% of all students were top performers in financial literacy but not in one of the other two domains, on average across OECD countries and economies and across all participating countries and economies (Table IV.B1.2.3).

Similarly, around four in five low performers in financial literacy were also low performers in mathematics (89%) and reading (82%), on average across OECD countries and economies. Only 1% of students were low performers in financial literacy but not low performers in mathematics nor reading (Table IV.B1.2.4).

While performance in financial literacy is highly correlated with performance in mathematics and reading, the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment also highlighted the specificities of financial literacy. For instance, 47% of all top performers in financial literacy were not top performers in mathematics, and 59% of top performers in financial literacy were not top performers in reading, on average across OECD countries and economies (Table IV.B1.2.3).

Moreover, on average across OECD countries and economies, 20% of the differences across students in how they performed in financial literacy was independent of their performance in mathematics and reading.5 In Italy, Norway and Saudi Arabia, more than 25% of the of the financial literacy score reflected factors that were not captured by the mathematics and reading assessments. Conversely, 80% of the variation in student performance in financial literacy could be explained by performance in mathematics and reading, on average across OECD countries and economies. High degrees of explained variation (at least 73%) were observed in every participating country and economy. Most of this explained variation (65% of the total variation) was jointly associated with mathematics and reading performance, again indicating the tendency for students to be strong (or weak) in all three subjects simultaneously, and the potential for general interventions to improve skills in all three subjects simultaneously (Table IV.B1.2.7).

Variation not explained by mathematics or reading performance implies that there is a wide dispersion of student performance in financial literacy amongst students who scored at the same level in the mathematics and reading assessments. It also suggests that it is possible to develop financial literacy skills amongst low performers in mathematics and reading. This unexplained variation in financial literacy performance might be related, among other factors, also to the aspects of financial literacy that are unique to the domain, such as the relationship between risk and reward, the short- and long-term dimensions of financial decisions, the ability to identify financial frauds and scams, or the ability to keep personal financial information safe.6 It is possible to estimate the extent to which students’ performance exceeded (or fell short of) his or her expected performance, based on his or her performance in the mathematics and reading assessments.7 This is known as the relative performance.

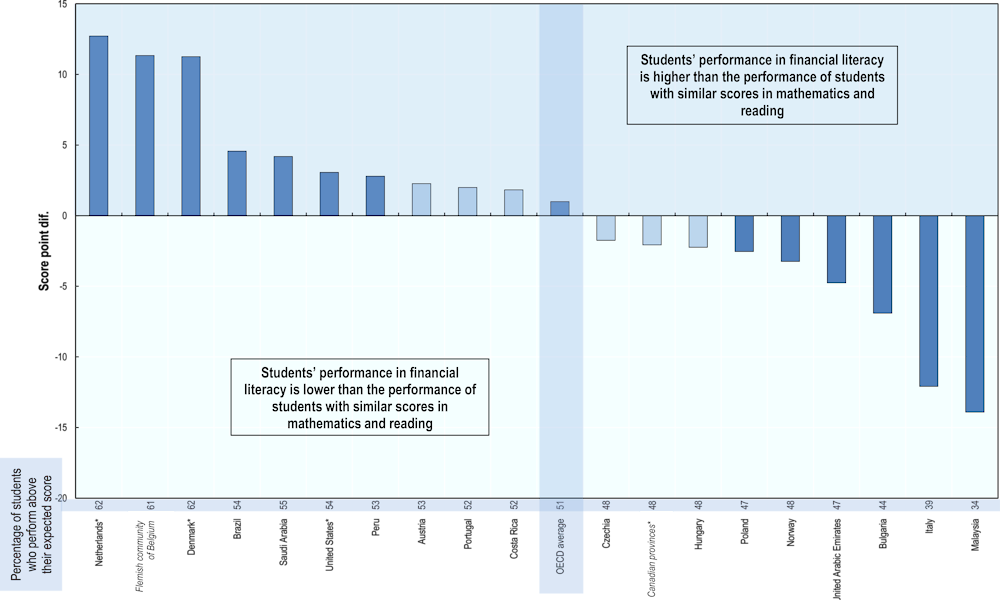

Figure IV.2.6 shows the average relative performance across students in each country and economy. Average relative performance was over 10 score points in the Flemish community of Belgium, Denmark* and the Netherlands*. Relative performance was also significantly positive in a further four countries and economies (Brazil, Peru, Saudi Arabia and the United States*). In these countries and economies, students performed better in financial literacy than their counterparts in other countries who had similar scores in mathematics and reading. This may suggest that these students were relatively stronger in competencies that are not associated with mathematics and reading, and that may include competences uniquely related to financial literacy.

By comparison, the average relative performance in Italy and Malaysia was less than -10 score points; the average relative performance was also significantly negative in a further five countries (Bulgaria, Norway, Poland, Spain and the United Arab Emirates). Students in countries and economies with a negative relative performance performed below their counterparts in other countries and economies who scored similarly in mathematics and reading. In other words, students in these countries were relatively weak in competencies that are not associated with mathematics and reading, and that may include competences that relate solely to financial literacy. The average relative performance of students in Austria, the Canadian provinces*, Costa Rica, Czechia, Hungary and Portugal was not significantly different from zero (Figure IV.2.6).

Figure IV.2.6. Relative performance in financial literacy

Difference between the actual financial literacy score and the score predicted by students' performance in mathematics and reading

Note: Statistically significant differences are shown in a darker tone (see Annex A3). Countries and economies are ranked in descending order of the score-point difference between actual and expected performance.

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 Database, Table IV.B1.2.8.

The national context of countries may help interpret 15-year-old students’ performance in financial literacy. Box IV.2.4 proposes contextual information to assist in comparing the performance in financial literacy across countries that participated in the PISA 2022 assessment.

Box IV.2.4. A context for comparing countries’ and economies’ performance in financial literacy

This section provides a brief overview of the context of the 18 countries that participated in the PISA 2022 assessment of financial literacy: Austria, Brazil, Bulgaria, Costa Rica, Czechia, Denmark*, Hungary, Italy, Malaysia, the Netherlands*, Norway, Peru, Poland, Portugal, Saudi Arabia, Spain, the United Arab Emirates and the United States*. These countries cover a relatively wide geographical area, including North and South America, Western, Central and Eastern Europe, Southeast Asia and the Middle East, representing about 45% of the world’s GDP.

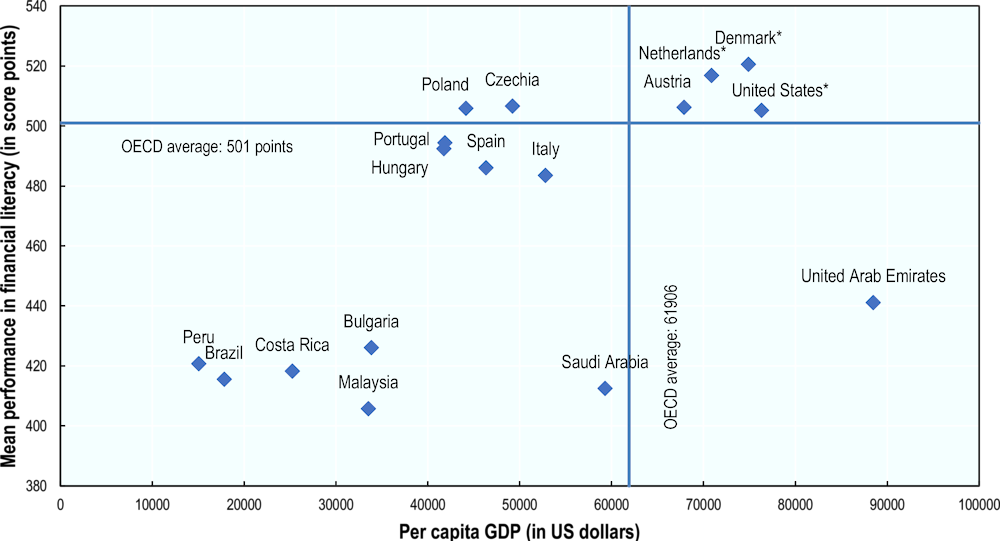

Figure IV.2.7. Mean performance in financial literacy and per capita GDP

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 Database, Table IV.B1.2.1 and Table IV.B1.2.9.

Two participating economies, the Flemish community of Belgium and the Canadian provinces*, are not covered in this section because they represent only certain subnational entities within Belgium and Canada. The Flemish community of Belgium covers 57% of the country’s total population of 15-year-olds, while the eight provinces of Canada that participated in the financial literacy assessment cover 75% of the country’s total population of 15‑year-olds.

The section highlights national characteristics that might shed light on the analysis of students’ proficiency in financial literacy, such as national income, income distribution, GDP growth, poverty rates, the development of financial markets, financial inclusion, expenditure on education and financial knowledge amongst adults (Table IV.B1.2.9).

Overall, students’ average performance in financial literacy as measured by PISA 2022 tends to be positively associated with adults’ financial knowledge, financial inclusion and expenditure on education. Financial literacy performance amongst students also appears to be associated with income inequality, with higher income inequality being associated with lower average financial literacy scores. The association between financial literacy and stock market capitalisation or poverty is very low. Nevertheless, these correlations should be interpreted with caution due to the very small number of country points.

It is worth noting that students’ average performance in financial literacy is only moderately related to per capita GDP. Figure IV.2.7 gives an indication of the direction of the relationship between per capita GDP and students’ mean score in financial literacy but does not display statistics about the strength of this association because they are based on a small number of country points. The scatter plot shows that, overall, per capita national income is positively associated with average performance in financial literacy, but some countries with lower per capita GDP perform better in financial literacy than wealthier countries. For example, the mean performance in Hungary, Poland and Portugal was significantly above that of United Arab Emirates, although per capita GDP in Hungary, Poland and Portugal was significantly lower than that in United Arab Emirates.

Table IV.2.5. Students’ performance in financial literacy in PISA 2022 chapter figures and tables

|

Table IV.2.1 |

Comparing countries’ and economies' mean performance in financial literacy |

|

Table IV.2.2 |

Financial literacy performance at the national level |

|

Table IV.2.3 |

Summary description of the five levels of financial literacy proficiency in PISA 2022 |

|

Table IV.2.4 |

Map of selected financial literacy questions, illustrating the proficiency levels |

|

Figure IV.2.1 |

Percentage of students at each level of proficiency in financial literacy |

|

Figure IV.2.2 |

Students’ self-assessed financial knowledge |

|

Figure IV.2.3 |

Changes across time in mean financial literacy performance |

|

Figure IV.2.4 |

Changes across time in mean financial literacy performance among countries that participated in all PISA financial literacy assessments |

|

Figure IV.2.5 |

Correlation between performance in financial literacy, mathematics and reading |

|

Figure IV.2.6 |

Relative performance in financial literacy |

|

Figure IV.2.7 |

Mean performance in financial literacy and per capita GDP |

References

[3] OECD (2023), PISA 2022 Assessment and Analytical Framework, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/dfe0bf9c-en.

[1] OECD (2022), OECD/INFE Toolkit for Measuring Financial Literacy and Financial Inclusion 2022, http://www.oecd.org/financial/education/2022-INFE-Toolkit-Measuring-Finlit-Financial-Inclusion.pdf.

[2] OECD/INFE (2023), OECD/INFE 2023 International Survey of Adult Financial Literacy, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/56003a32-en.

Notes

← 1. In this report, the range of ranks is defined as the 95% confidence interval for the rank statistic. This means that there is at least a 95% probability that the interval defined by the upper and lower ranks, and computed based on PISA samples, contains the true rank of the country or economy (see Annex A3).

← 2. Eight Canadian provinces* participated in the PISA 2022 financial literacy assessment, compared to only seven in 2015 and 2018. Therefore, results for the Canadian provinces* are not comparable across assessments.

← 3. Students who sat the financial literacy assessment were also assessed in mathematics and reading but not in science; hence, no plausible values for their performance in science were calculated and no correlation with their (putative) science scores could be determined.

← 4. There are six proficiency levels in reading and mathematics; hence, top performers in these two domains have attained either proficiency Level 5 or 6, while top performers in financial literacy have attained proficiency Level 5.

← 5. This was measured through a linear regression of student performance in financial literacy over student performance in mathematics and reading.

← 6. Unexplained variation in financial literacy might be related to other factors not accounted for in the model, including students’ characteristics beyond their performance in mathematics and reading, and measurement error.

← 7. In technical terms, a regression of student financial literacy performance over student mathematics and reading performance was performed; the relative performance was the residual of the financial literacy performance. This regression included all participating countries and weighted all participating countries equally.