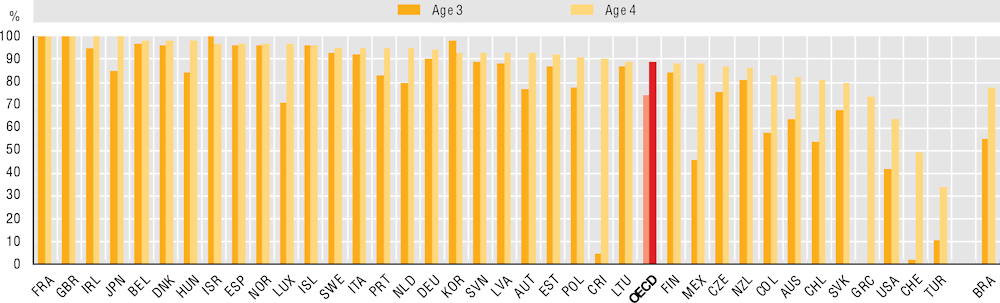

Early childhood education is critical for children’s cognitive and emotional development, learning and well-being (OECD, 2022). Children who participate in high-quality organised learning at a young age are more likely to have better education outcomes (OECD, 2022). Early enrolment is thus increasingly considered a core measure of access to education. On average across the OECD in 2020, 88.7% of 4-year-olds and 74.3% of 3-year-olds were enrolled in education. France (where it has been compulsory from 3 years since 2019), Ireland, Israel (compulsory from 3 years since 1949), Japan and the United Kingdom have reached 100% enrolment for 3-4 year-olds. The lowest enrolment rates for 4-year-olds are in Türkiye (34%), Switzerland (49%) and the United States (64%) (Figure 3.13). Besides these, all other OECD countries are within 10 percentage points (p.p.) of the average.

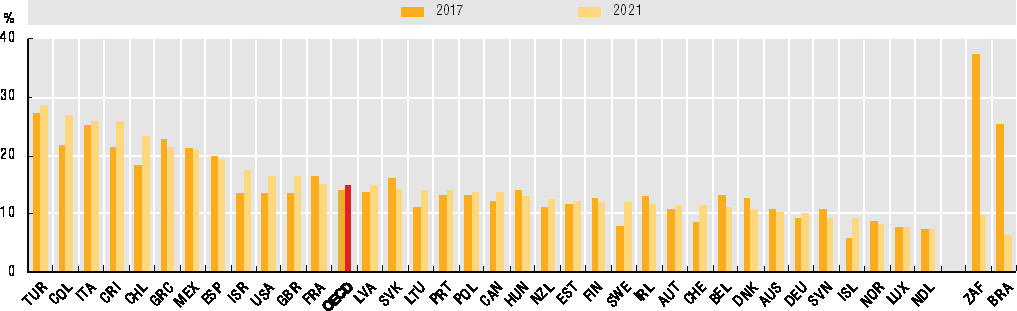

The share of 15-29 year-olds who are not in education, employment, or training (NEET) is a measure of the responsiveness of the education system. High NEET rates represent a failure to deliver the same opportunities to every citizen, regardless of socio-economic context. Reducing them is an important challenge for OECD countries, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2021, on average, 15.0% of 15-19 year-olds across the OECD were NEET, a 1 p.p. increase since 2017 (14.1%). The Netherlands (7.4%), Luxembourg (7.8%) and Norway (8.4%) had the lowest NEET rates in 2021, while Türkiye (28.7%), Colombia (27.1%), Italy (26.0%) and Costa Rica (26%) had the highest. The most significant reductions across the OECD were in Belgium, Denmark and the Slovak Republic (-2 p.p. each since 2017) (Figure 3.14).

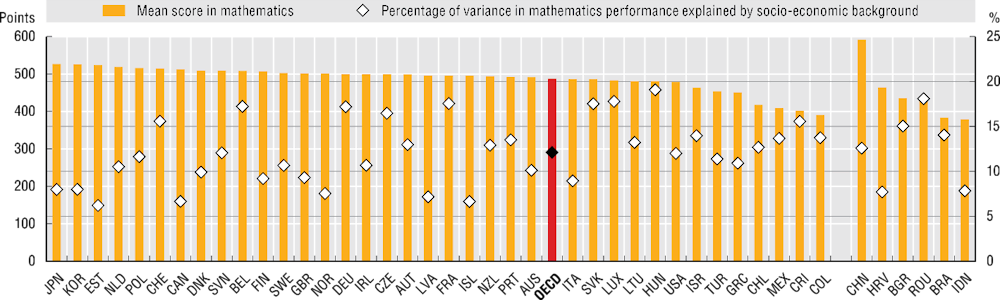

Quality of education can be assessed by how effectively students acquire the skills they need to thrive in society. Equity is an important aspect of quality: personal circumstances should not be an obstacle to achieving educational potential and all individuals should reach at least a minimum level (OECD, 2012). In 2018, students across the OECD scored an average of 487 points in mathematics in the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), The highest average scores were in Japan (527 points), Korea (526 points) and Estonia (523 points). Students in Colombia (391 points), Costa Rica (402 points) and Mexico (409 points) had the lowest average scores (Figure 3.15).

However, these averages hide inequalities. On average across the OECD, 12.1% of the variance in mathematics performance can be attributed to students’ socio-economic status. The influence of background on performance is most significant in Hungary (19.1%) followed by Luxembourg (17.8%), and France and the Slovak Republic (17.5% each). In contrast, in Estonia (6%), Canada (6.7%) and Iceland (6.6%), socio-economic background plays a much smaller role (Figure 3.15).