Increases in income inequality have been associated with worsening political polarisation and disenchantment with political systems (Winkler, 2019). The global economic situation following the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine has resulted in high inflation and sharp increases in energy and food prices, which disproportionately affect low-income and vulnerable households and could have long-lasting impacts on people’s wellbeing and living standards. OECD countries are implementing a range of policies to address rising prices and redistribute income between richer and poorer households, such as targeted and non-targeted cash transfers, vouchers and subsidies to households and firms, price control measures, and tax reductions (OECD, 2022). Monitoring changes in income inequality will be key to assessing the effectiveness of such measures.

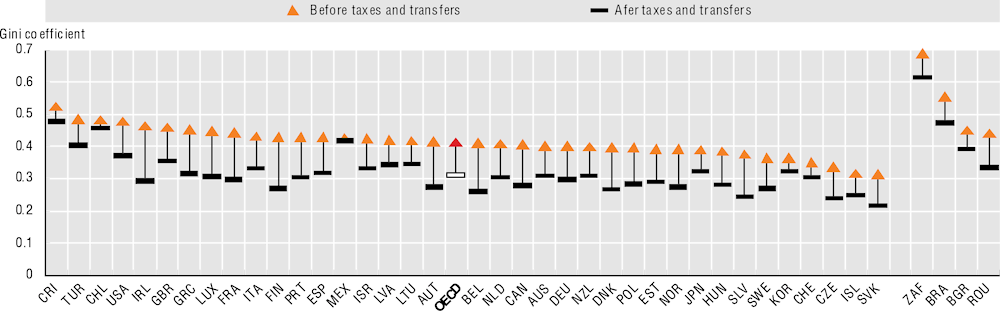

Even before the current crises, reducing income inequality has been a long-standing objective of OECD countries. The average Gini coefficient of income inequality in 2019 was 0.41 before taxes and transfers (market income) and 0.31 after taxes and transfers (disposable income), where 0 represents perfect equality and 1 perfect inequality. A large difference between market and disposable income inequality implies greater government redistribution. Countries with the largest differences include Finland (0.26 points), Ireland (0.17) and Belgium (0.15). Chile (0.025), Korea (0.04) and Switzerland (0.05) have among the smallest differences (Figure 11.23).

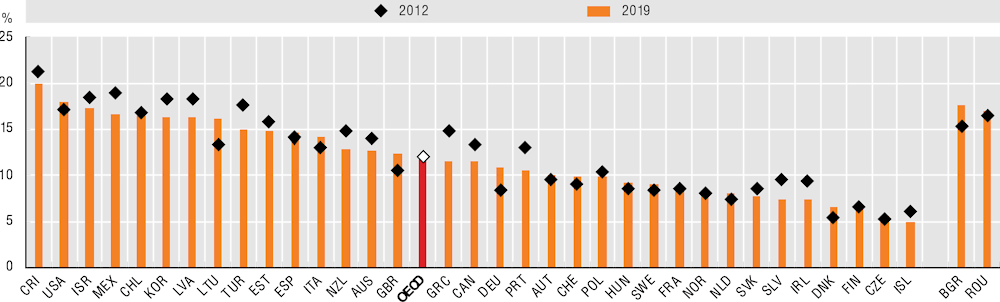

Societies with high levels of income inequality often also have high levels of relative poverty. Income redistribution and inequality reduction measures may also reduce poverty. In 2019, across OECD countries, the relative poverty rate after taxes and transfers was around 12% of the population, although with large variations among countries. In Costa Rica, 20% of the population were below the poverty line in 2019, compared to only 5% in Iceland. Between 2012 and 2019, the relative poverty rate after taxes and transfers remained stable or fell in 70% of OECD countries. Lithuania and Germany reported the largest increases of about 3 percentage points (Figure 11.24).

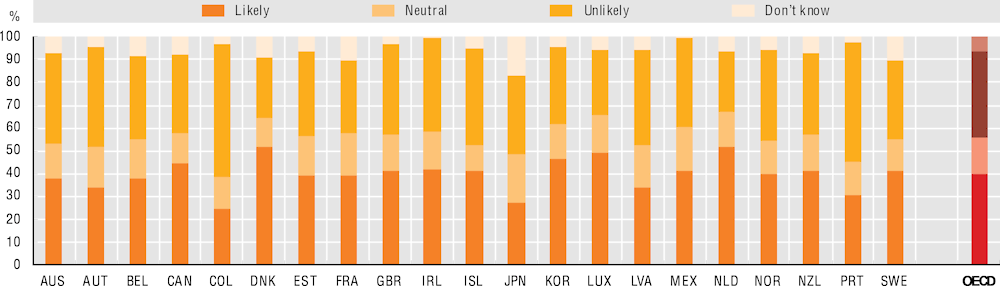

Perceptions of fair treatment may affect people’s demand for inequality reduction and could influence government action towards redistributive policies (Ciani, Fréget and Manfredi, 2021). On average, people in OECD countries are sceptical that public employees would treat the rich and poor equally, with only 40% believing this was likely. Denmark and the Netherlands do best on this measure, with 52% of respondents in both countries confident that this would happen (Figure 11.25).