Flexible working arrangements are not new, but public administrations have scaled up their use over the last few years. This happened particularly since the COVID-19 pandemic, when the associated quarantine periods meant they were used much more frequently. Most public servants experienced flexibility in two ways: adapting their working hours, and/or adapting their work location, usually by working from home. Outside of emergency situations, public administrations are consolidating the use of these arrangements as tools to improve productivity, enhance employee engagement and attract and retain an increasingly diverse public sector workforce.

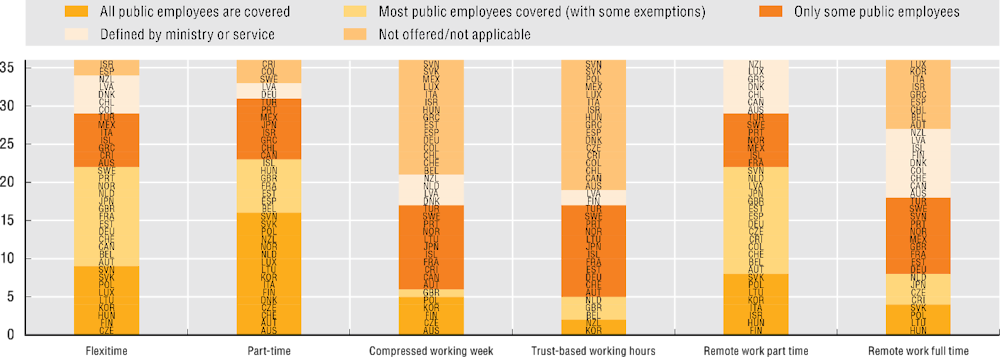

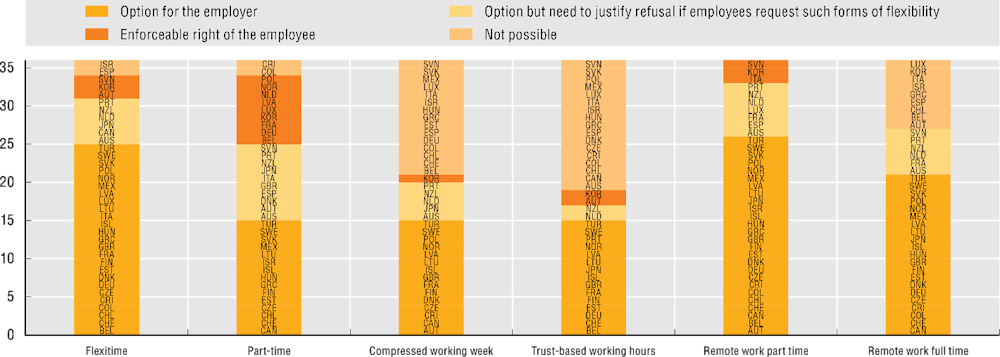

In most OECD countries, flexible working arrangements are available to most or all public servants (Figure 13.5). This is the case for part-time work and flexitime (both available in 23 out of 36 countries, 64%), and remote work part-time (22 out of 36 countries, 61%). In Poland, five of the six possible forms of flexible working are available to all public employees. However, the actual use of such arrangements depends on several factors, such as the type of job and agreements between managers and employees. Most flexible arrangements are only an enforceable right for employees in a small fraction of OECD countries – for instance compressed working weeks are only a right in Korea; remote work part-time in Italy, Korea and Slovenia; and trust-based working hours in Austria and Korea (Figure 13.6). The picture is different for part-time work, a flexible working arrangement that has been in place for decades and plays an important social role in enabling employees to balance personal commitments with working hours. The use of part-time work arrangements is an enforceable employee right in one in four countries (9 out of 36 OECD countries, 25%). The statutory existence of flexible working arrangements does not mean that employees can spontaneously use them. In this context, high levels of autonomy play a key role as facilitators of a flexible work culture that also requires clear communication channels with managers and regular social dialogue in the public service.

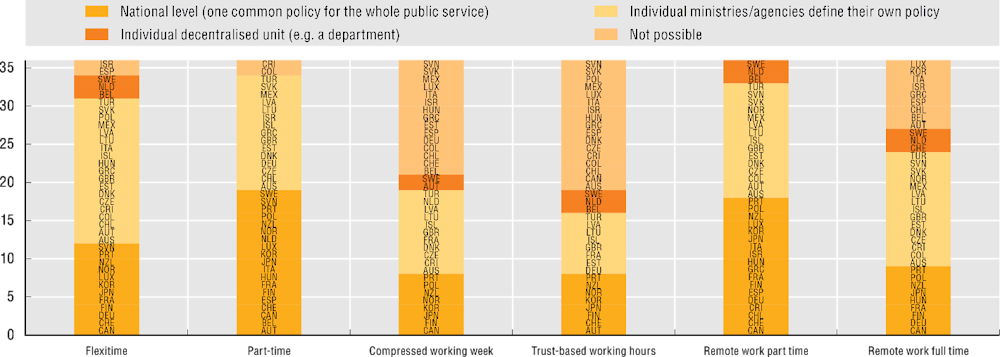

Flexible working arrangements are not always defined at the same level; some countries set regulations and policies at the national level, while others set them at ministerial or departmental level. Overall, OECD countries are fairly evenly balanced between regulating flexible working arrangements centrally and taking a more decentralised approach (Figure 13.7). In Finland, Japan, New Zealand and Portugal, all six forms of flexible working arrangements are defined at the national level, i.e. one common policy for the whole public service. This type of policy typically allows for a level of flexibility in its application at the unit level, but provides the whole public service with a common overarching policy. In countries with a high degree of decentralised working arrangements, like Sweden and the Netherlands, most forms of flexible working arrangements are directly determined at the unit level. Embedding flexible working arrangements can have many positive aspects, but also limitations. As such, there is a need for continued in-depth and longer-term analysis of the implications for productivity, well-being, and workplaces for employees, managers, and organisations.