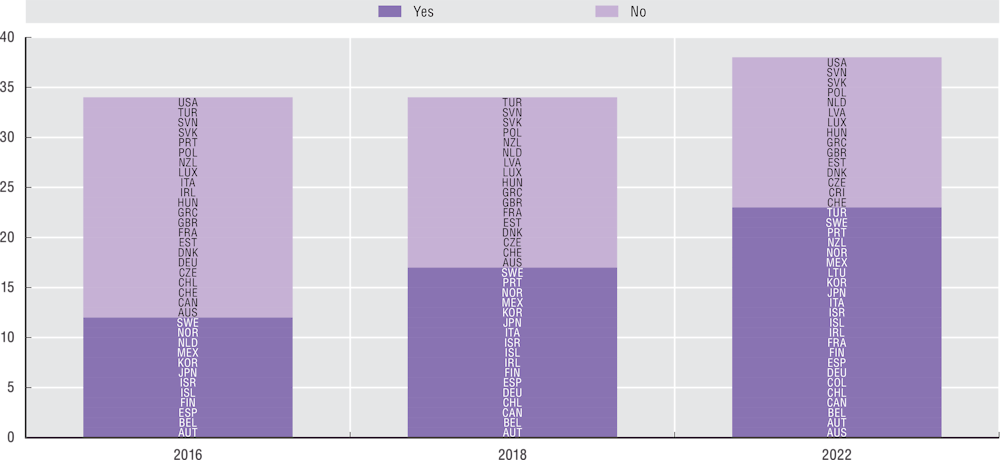

Overcoming gender inequalities offers significant benefits for society and the economy. Closing gender employment gaps can strengthen economic growth and recovery. Effective implementation of gender budgeting can ensure budget policy advances gender equality objectives, such as increased workforce participation, GDP gains and improvements to fiscal sustainability (Nicol, 2022). Results from the 2022 OECD Survey on Gender Budgeting show a steady increase in the practice of gender budgeting, with 23 OECD countries having introduced measures (61%), compared to 17 in 2018 (50%) and 12 in 2016 (35%) (Figure 6.4).

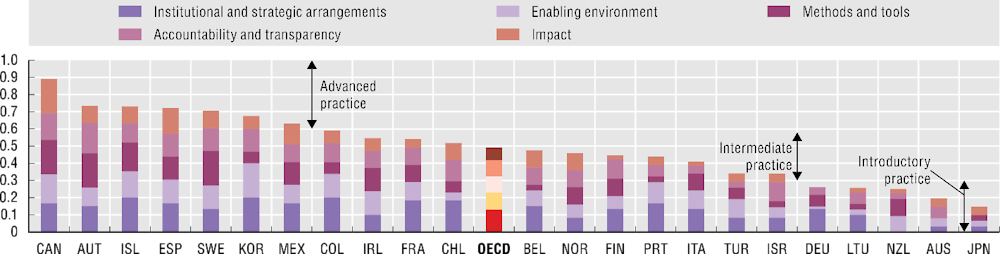

The OECD’s Gender Budgeting Index assesses the implementation of gender budgeting across member countries. In 2022 the Index was designed around the five building blocks of the 2023 OECD Framework for Gender Budgeting: (1) institutional and strategic arrangements; (2) enabling environment; (3) methods and tools; (4) accountability and transparency; and (5) impact (Gatt Rapa and Nicol, 2023b and 2023c forthcoming).

Figure 6.5 presents the 2022 OECD Gender Budgeting Index. Seven countries achieved an advanced score (0.6 or above). Canada, which has legislated for gender and diversity in budgeting since 2018, obtained the highest score overall. Austria, Iceland, Korea, Mexico, Spain and Sweden also achieved advanced scores. Although approaches to gender budgeting in each of these countries vary, each country receiving an advanced score has a comprehensive approach that displays a range of measures across the building blocks.

The institutional and strategic arrangements building block achieved the highest score amounting to 0.13 on average. Countries achieving the highest score (0.20) in this component of the index are those that have a well-defined legal basis (law or constitution), set clear gender equality goals in their policies, and where the central budget authority is leading gender budget implementation, for example in Colombia, Iceland and Korea (see Online Figure G.3.4).

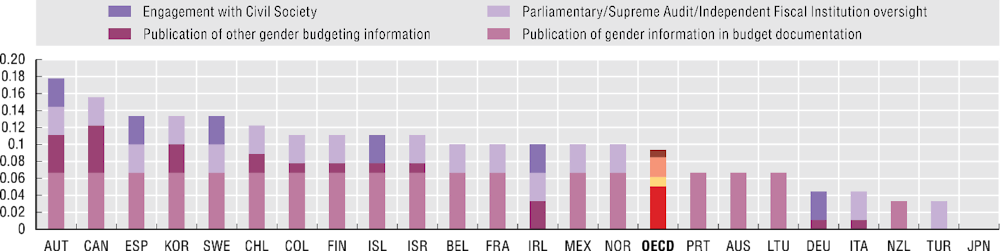

The two newly added building blocks, accountability and transparency, and impact, achieved the lowest comparative index scores reflecting room for further advancements in scrutiny mechanisms and the effective use of evidence gathered through gender budgeting. With an average score of 0.09 for the accountability and transparency building block, countries faring better in this component are those that include gender information in budget documentation, and that have oversight processes including regular reporting to parliament and parliamentary committee hearings on gender budgeting. This is for example the case in Austria, resulting in the highest score of 0.18 (Figure 6.6). The score of the building block on impact is also comparatively low amounting to 0.07 on average. Elements tilting towards a higher score were the consistent use of gender budgeting insights in budget decisions as well as achieving a gender perspective in policy development and resource allocation, such as in Canada with the highest score of 0.2 (see Online Figure G.3.5).