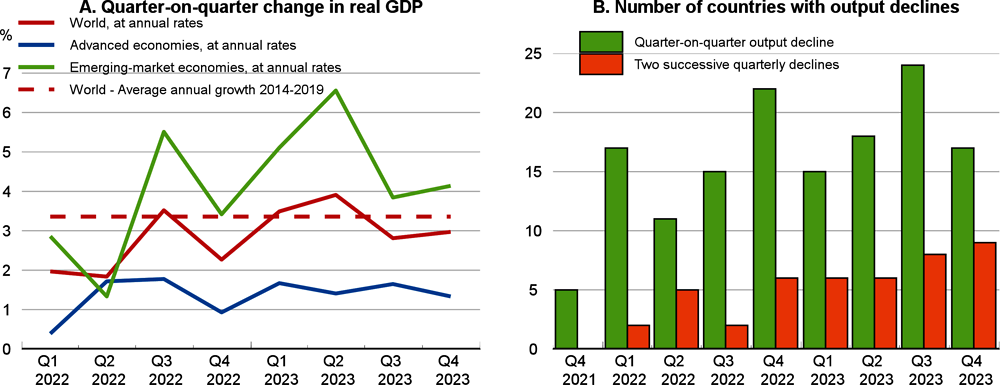

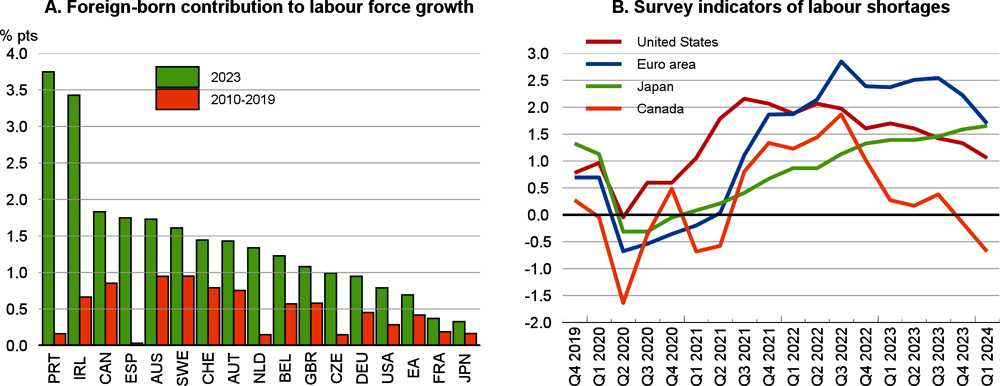

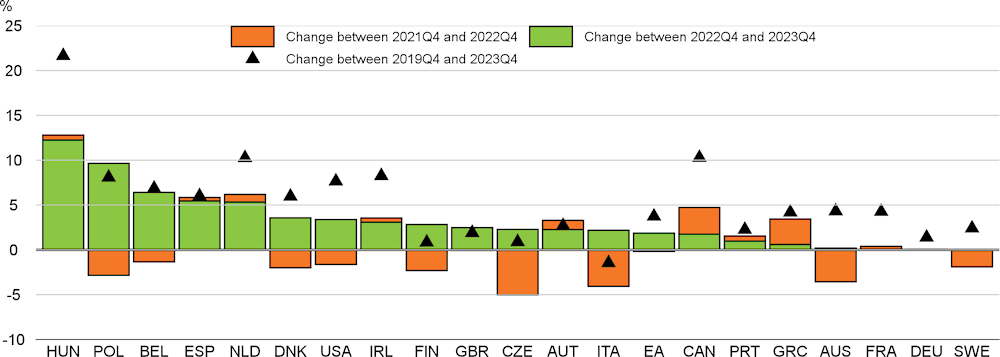

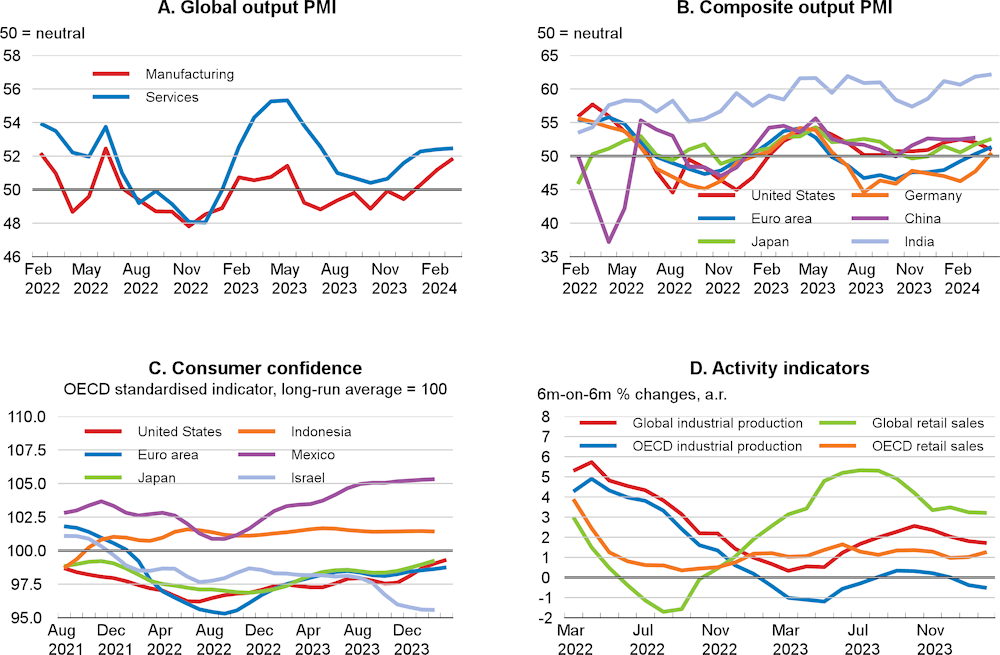

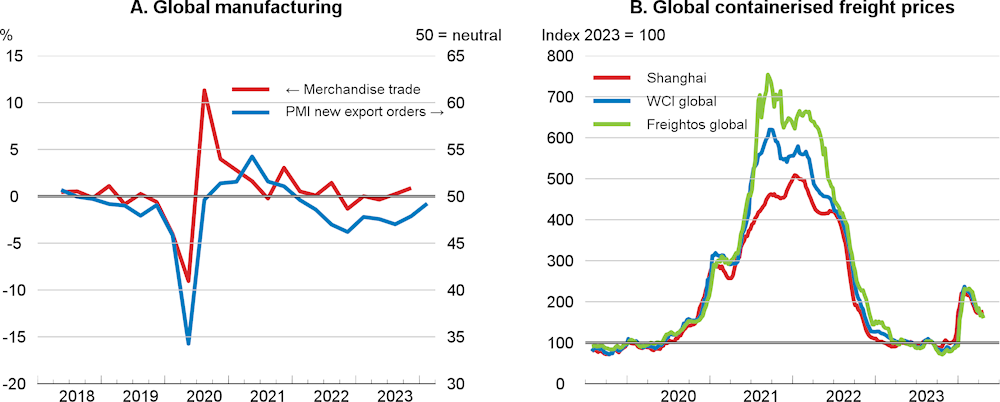

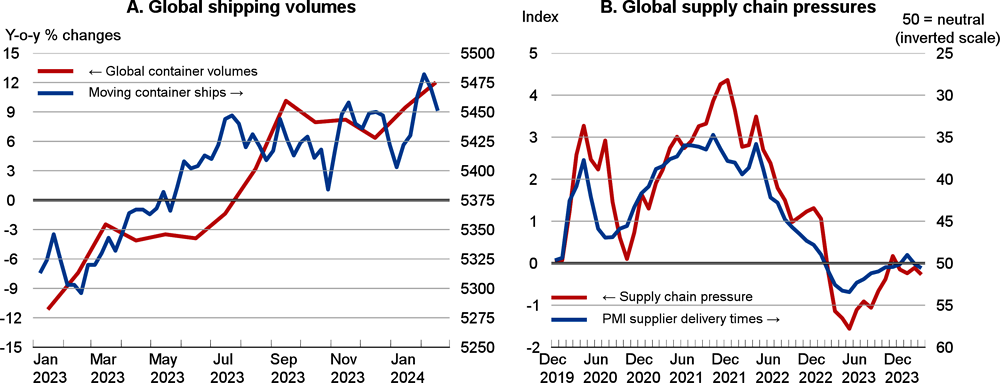

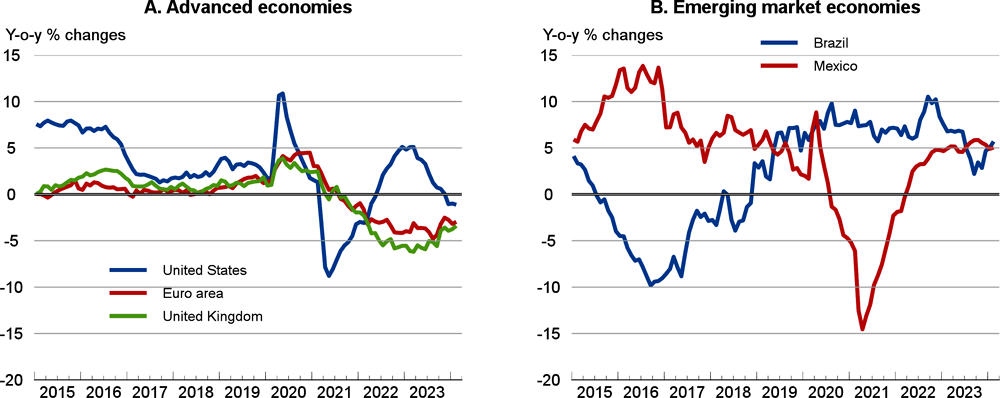

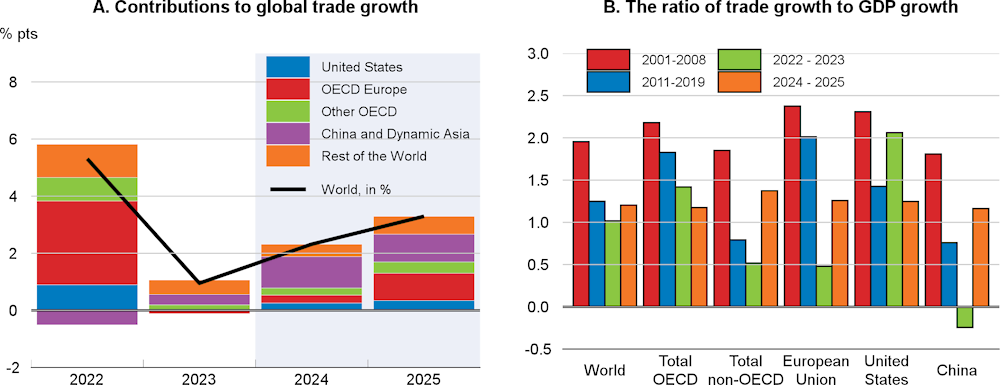

There are some signs that the global outlook has started to brighten, even though growth remains modest. The impact of tighter monetary conditions continues, especially in housing and credit markets, but global activity is proving relatively resilient, inflation is falling faster than initially projected and private sector confidence is now improving. Supply and demand imbalances in labour markets are easing, with unemployment remaining at or close to record lows, real incomes have begun to turn up as inflation moderates, and trade growth has turned positive. However, developments continue to diverge across countries, with softer outcomes in Europe and most low-income countries, offset by strong growth in the United States and many large emerging‑market economies.

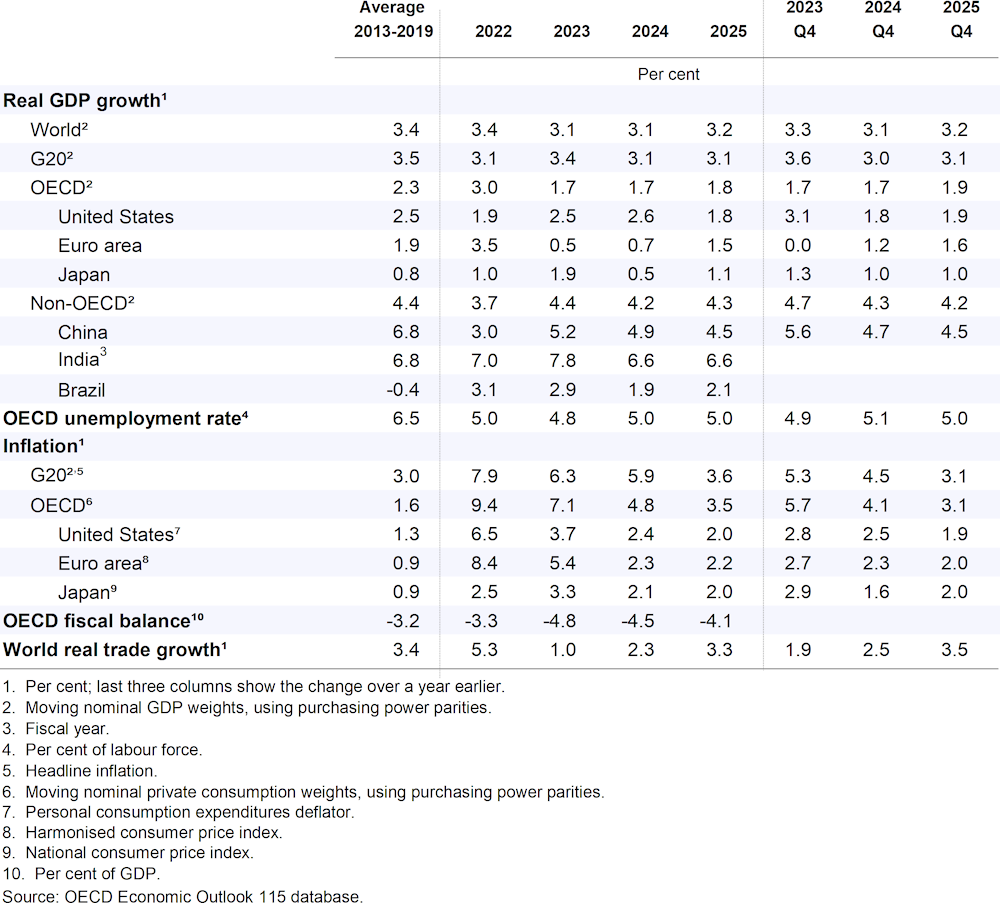

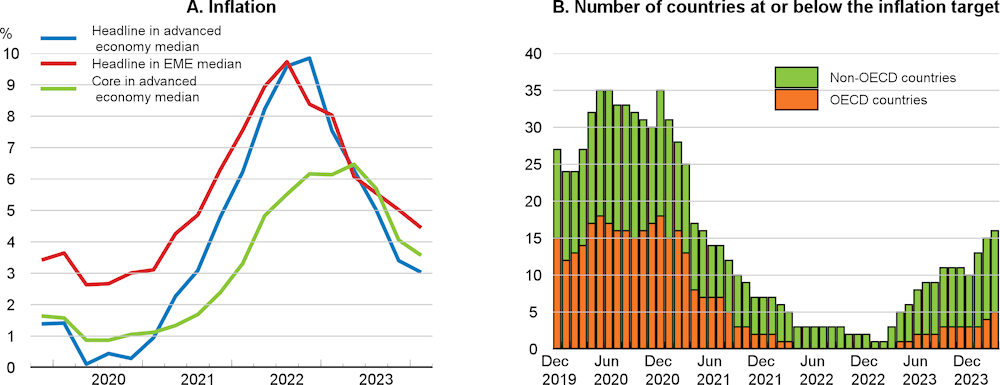

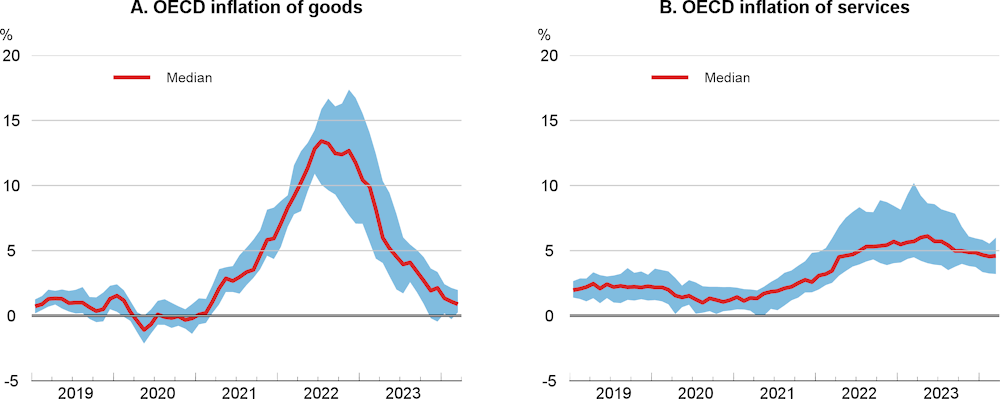

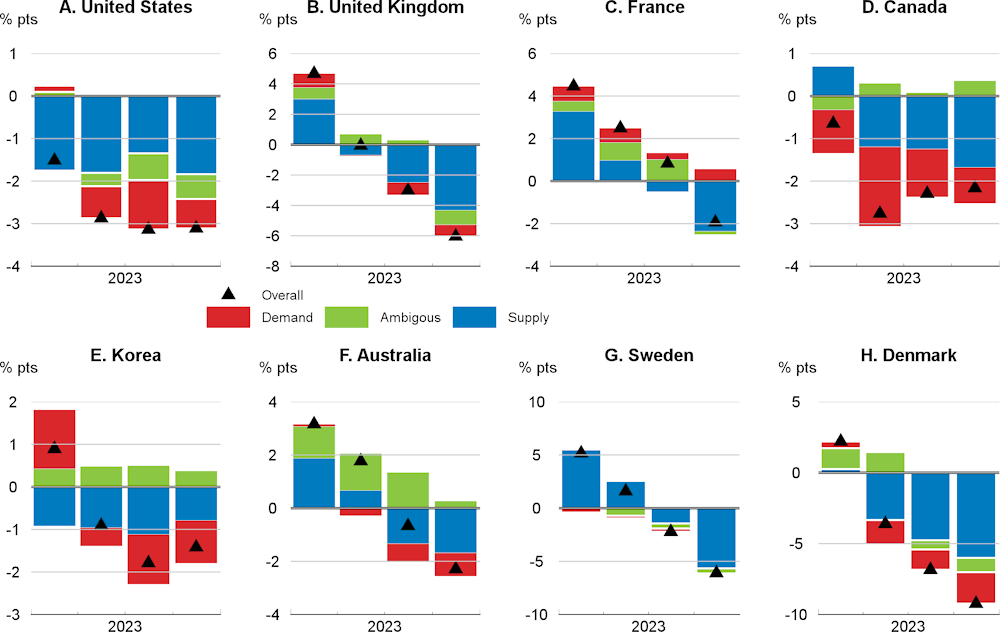

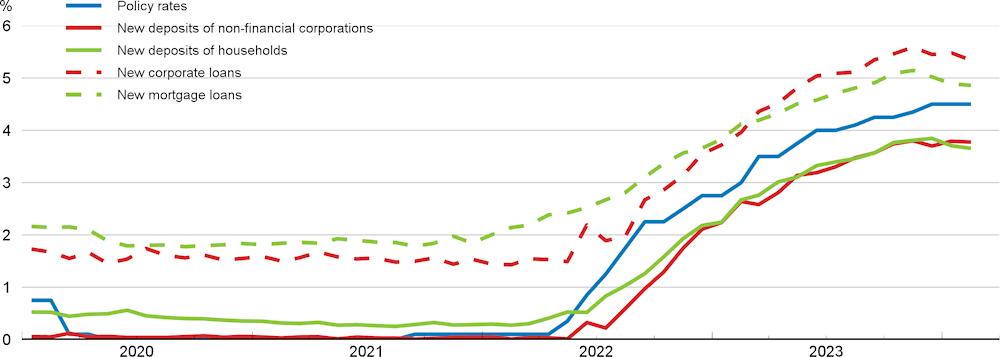

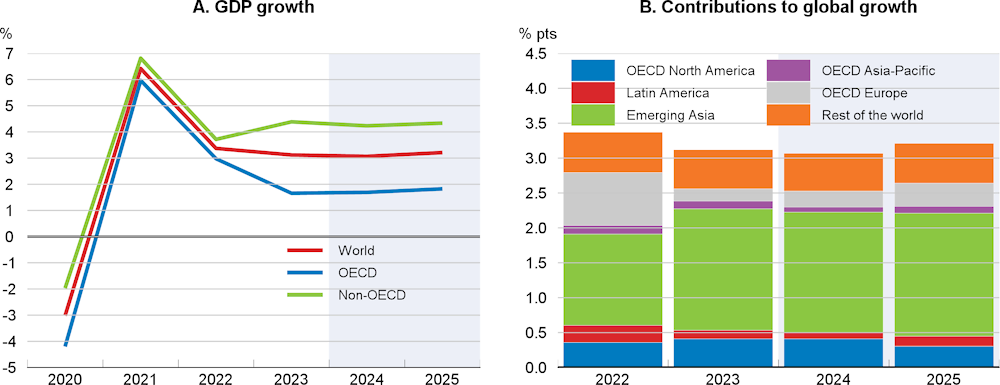

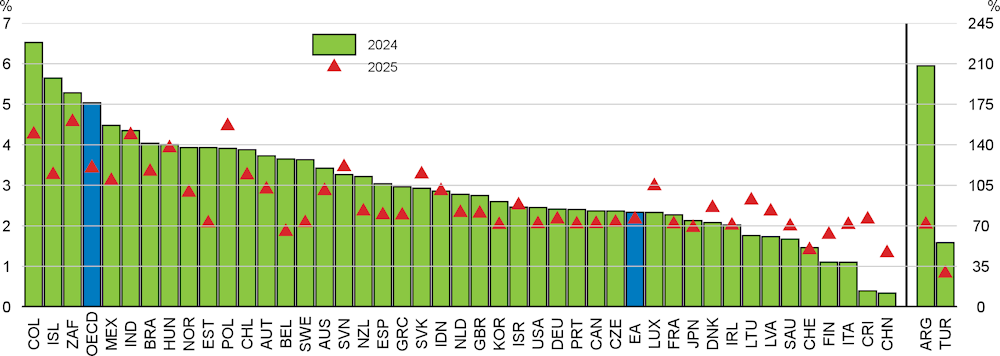

Global GDP growth is projected to be 3.1% in 2024, unchanged from 2023, before edging up to 3.2% in 2025 helped by stronger real income growth and lower policy interest rates (Table 1.1). The overall macroeconomic policy mix is nonetheless expected to remain restrictive in most economies, with real interest rates declining only gradually and mild fiscal consolidation in most countries over the next two years. China is an important exception, with low interest rates and significant additional fiscal support now appearing likely in 2024 and 2025. The divergence across economies is expected to persist in the near term but fade as the recovery in Europe becomes more firmly based, and growth moderates in the United States, India and several other emerging-market economies. Annual consumer price inflation in the G20 economies is projected to ease gradually, helped by fading cost pressures, declining to 3.6% in 2025 from 5.9% in 2024. By the end of 2025, inflation is projected to be back on target in most major economies.

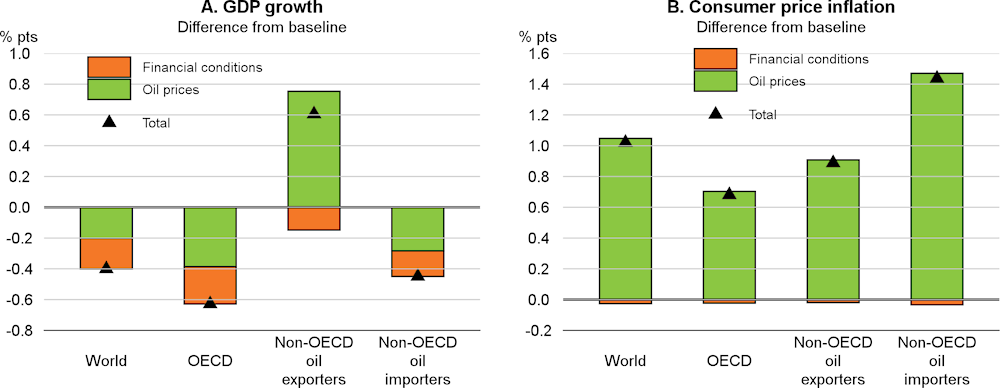

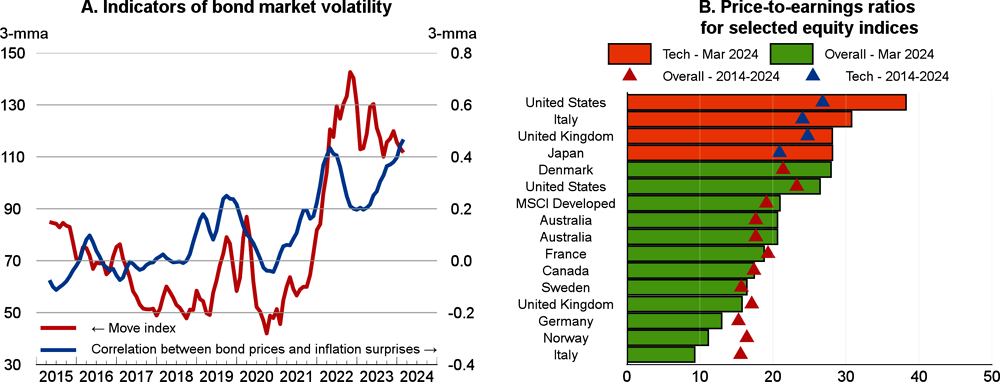

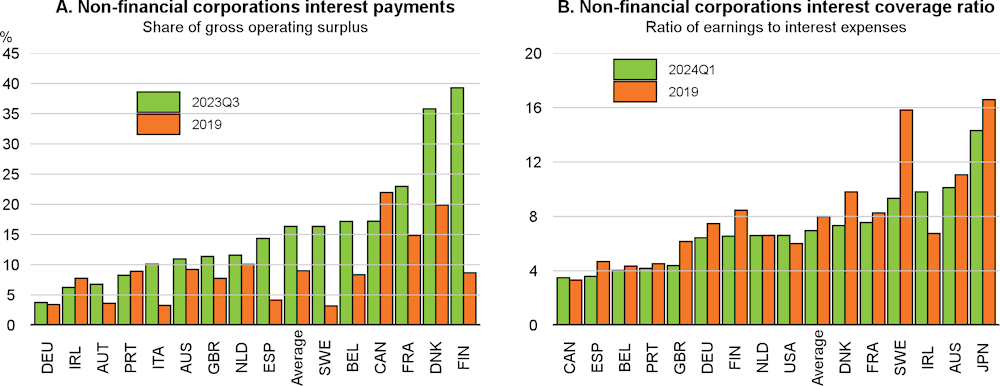

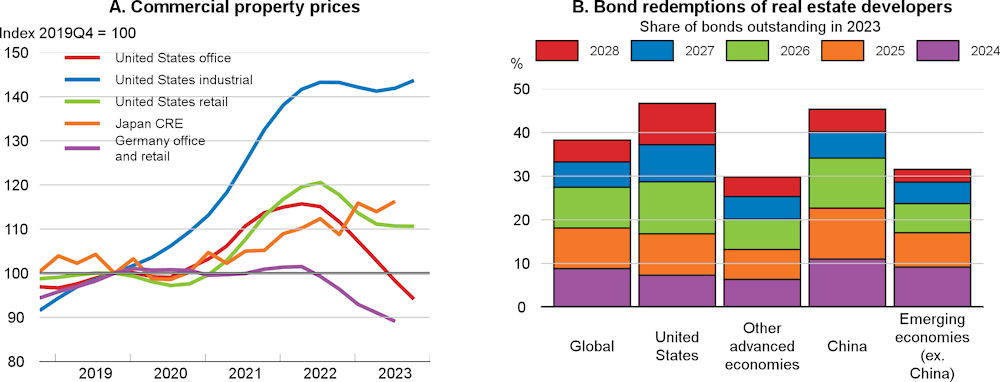

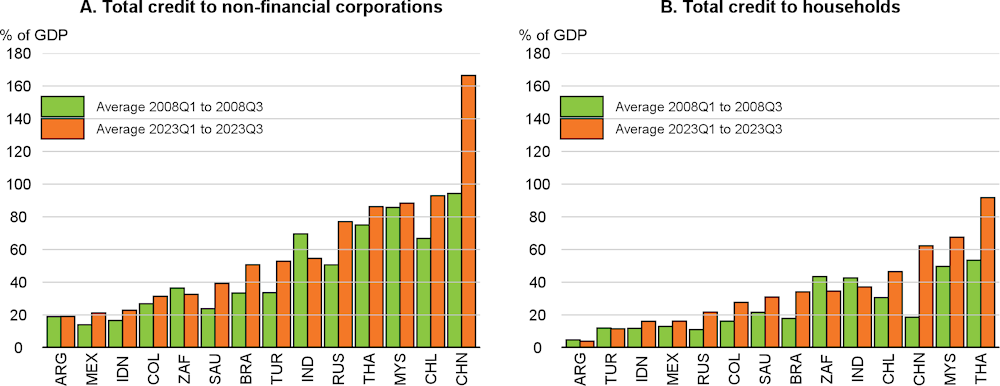

The overall risks around the outlook are becoming better balanced, but substantial uncertainty remains. High geopolitical tensions remain a significant near-term adverse risk, particularly if the evolving conflicts in the Middle East were to intensify and disrupt energy and financial markets, pushing up inflation and reducing growth. Further reductions in inflation may also be slower than expected if cost pressures and margins remain elevated, particularly in services. This could result in slower-than-expected reductions in policy interest rates, exposing financial vulnerabilities and potentially generating a sharper slowdown in labour markets. Another key downside risk is that the future impact of higher real interest rates proves stronger than anticipated. Debt-service burdens are already high and could rise further as low-yielding debt is rolled over, or as fixed-term borrowing rates are renegotiated. Some sectors, particularly commercial real estate, remain hard pressed, and corporate bankruptcies and defaults are now above pre-pandemic levels in several countries, posing risks to financial stability. Growth could also disappoint in China, either due to the persistent weakness in property markets or smaller‑than‑anticipated fiscal support over the next two years, although activity could be stronger than expected if fiscal support is extensive or well-targeted. On the upside, demand growth could prove stronger than expected, especially in advanced economies if households and corporates draw more fully on the savings accumulated during the pandemic. Continued strong labour force growth in many countries might also enable inflation to fall more quickly than anticipated.

Against this backdrop, the key policy priorities are to ensure a durable reduction in inflation, establish a fiscal path that will address rising pressures, and undertake reforms to raise sustainable and inclusive growth in the medium term.

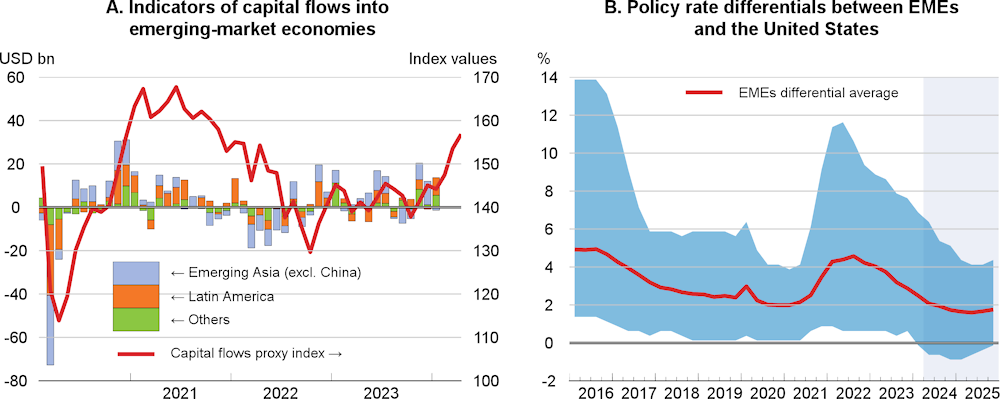

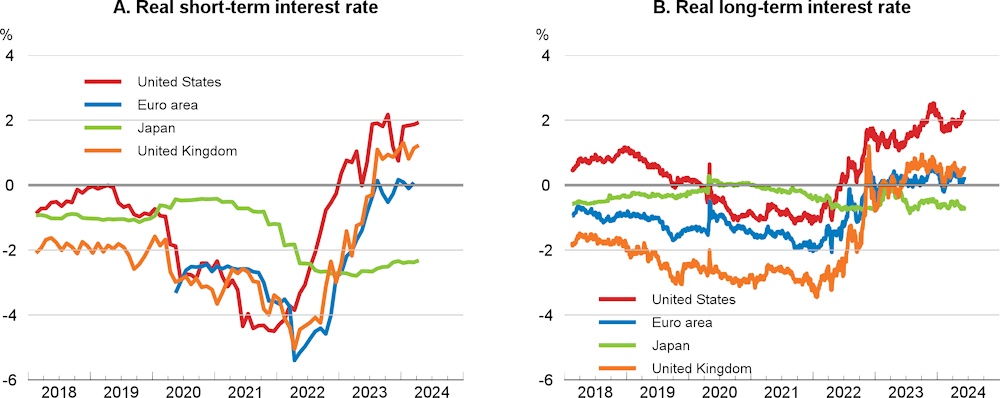

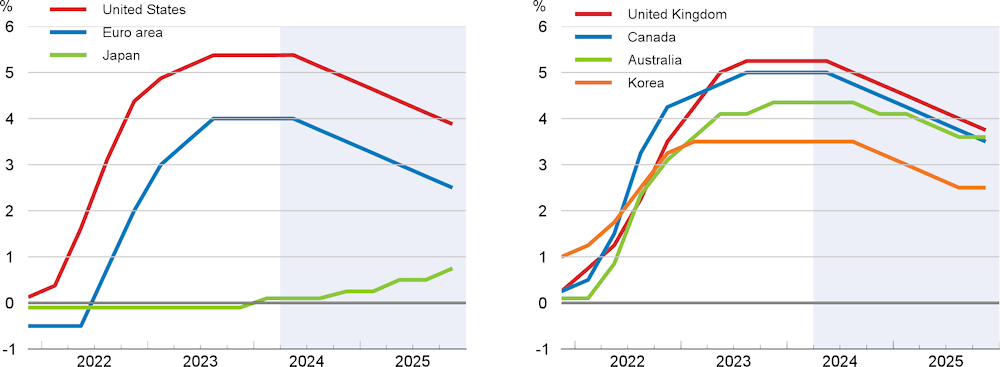

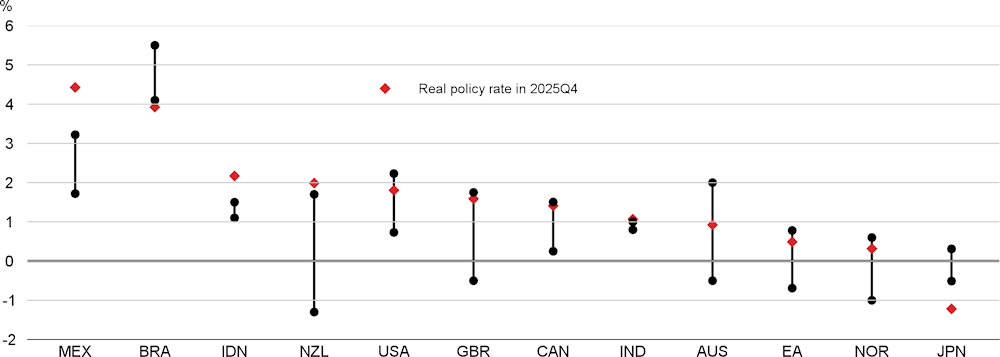

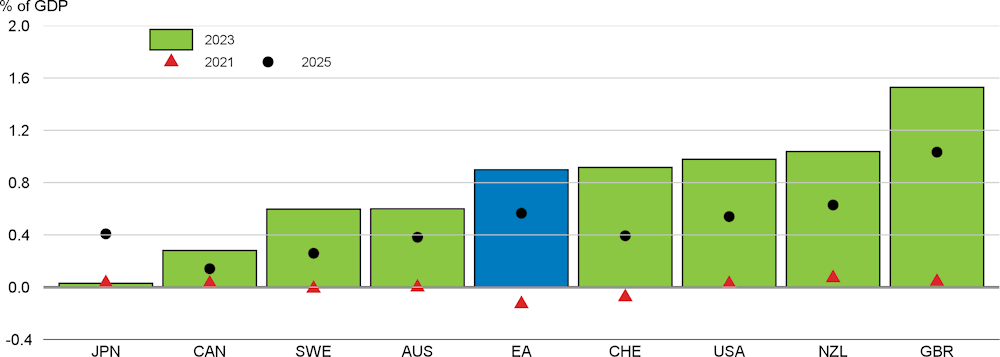

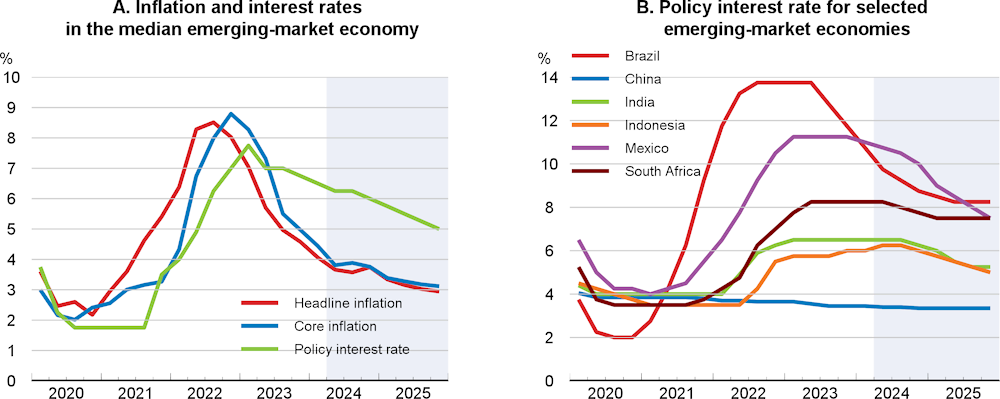

Monetary policy needs to remain prudent to ensure that underlying inflationary pressures are durably contained. Scope exists to lower nominal policy interest rates this year and next as inflation declines, but the policy stance should remain restrictive in most major economies for some time. With real interest rates currently high, policy interest rates will need to move towards neutral levels as inflation returns to target to ensure that growth does not weaken excessively and inflation does not undershoot. In Japan, a gradual increase in policy interest rates would be appropriate in 2024‑25 provided inflation settles at 2%, as projected. Easier global financial conditions enhance policy space in emerging-market economies, but the pace of rate reductions will need to remain cautious to maintain anchored inflation expectations and avoid disruptive capital outflows as yield differentials narrow with the advanced economies.

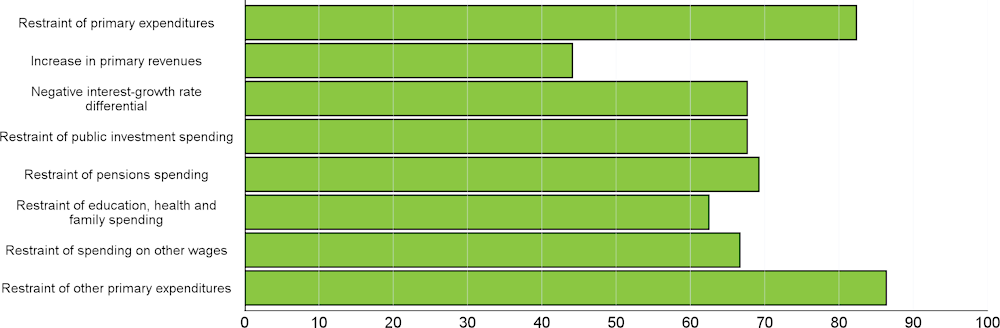

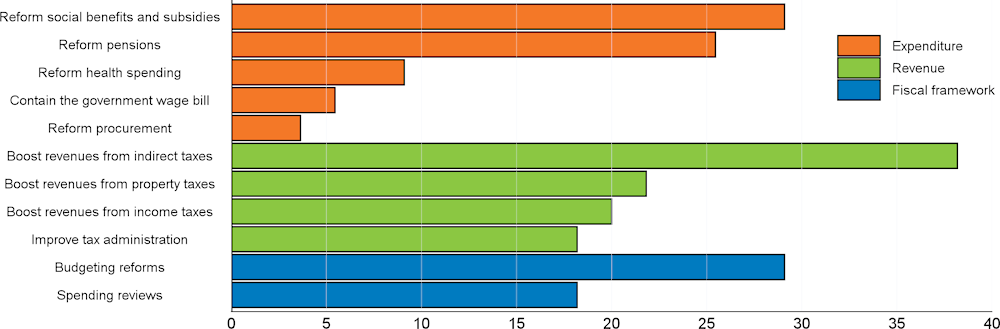

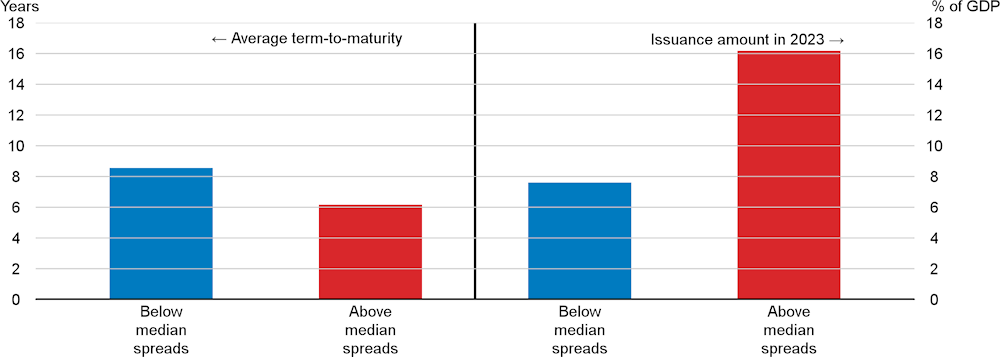

Governments face mounting fiscal challenges from rising debt and sizeable additional spending pressures from ageing populations, climate change mitigation and adaptation, defence and the need to finance new reforms. Debt-service costs are also increasing as low‑yielding debt matures and is replaced by new issuance. Without action, future debt burdens will rise significantly. Few countries appear likely to achieve a sustained primary budget surplus in the near term, making it challenging to stabilise debt. Stronger efforts to contain spending, enhance revenues, and increase growth would improve debt sustainability and resilience, and preserve the resources needed to support climate and distributional goals.

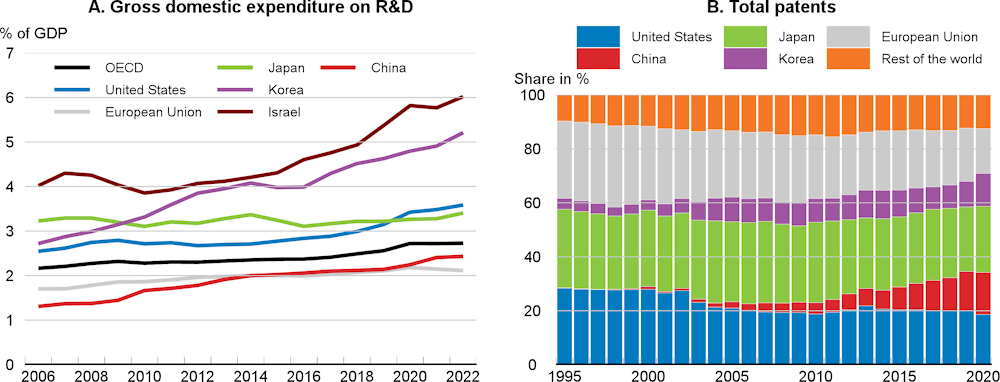

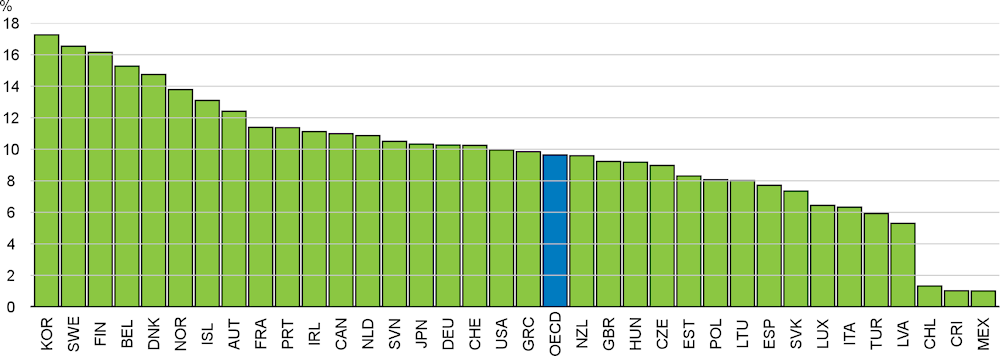

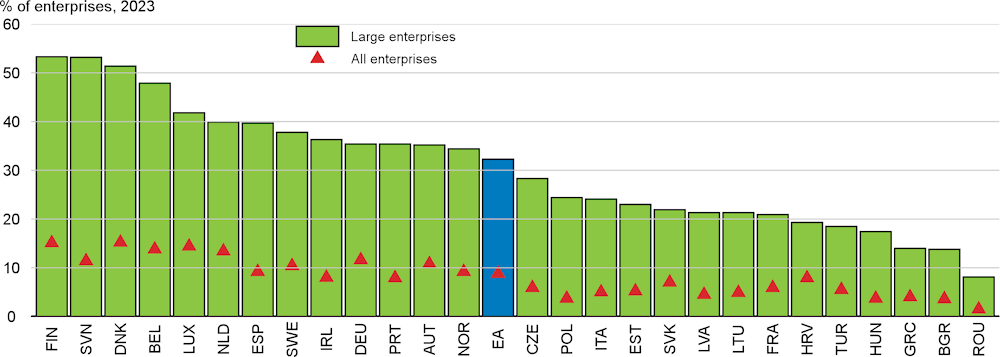

The foundations for future output and productivity growth need to be strengthened. Ambitious structural policy reforms are required to improve educational outcomes, enhance skills development and innovation, and reduce the constraints in labour and product markets that impede investment and labour force participation. Strengthening skills, removing obstacles to the entry and expansion of new firms, and well-designed science and technology policies are all essential to help countries strengthen their innovative capacity and to maximise the benefits gained from adopting technologies and ideas developed elsewhere. New general-purpose technologies, such as artificial intelligence, can enhance the productivity of capital.

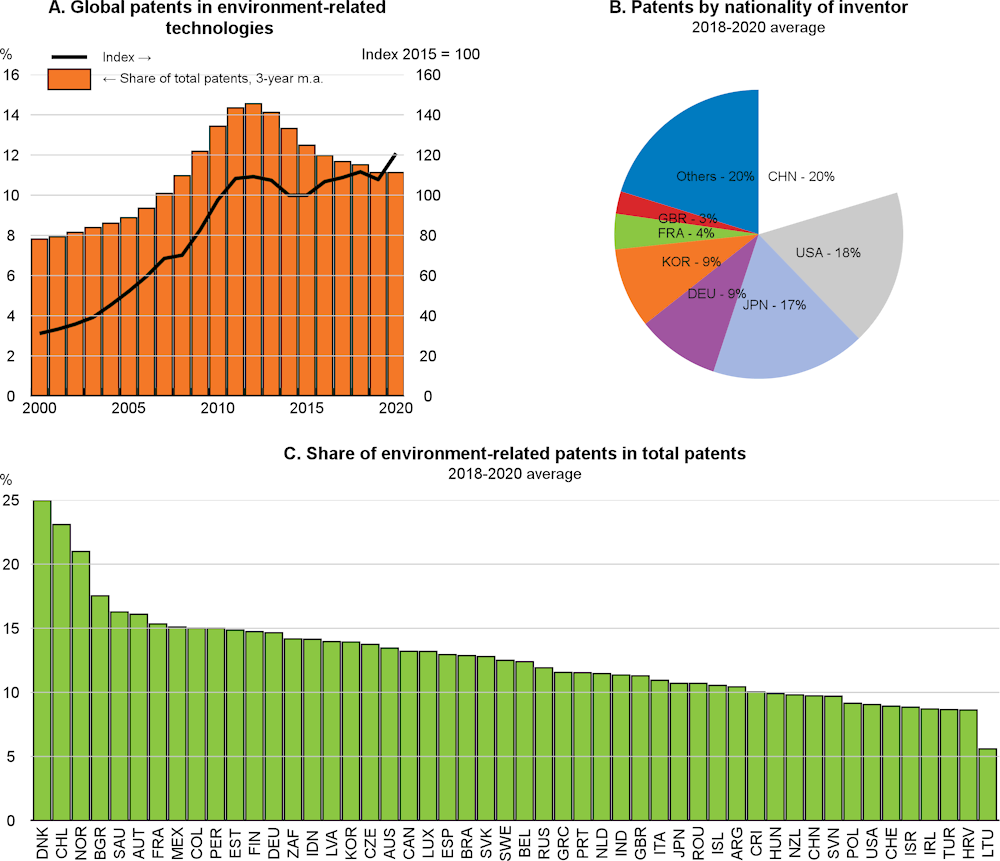

In an interconnected world, enhanced multilateral co-operation is needed to help knowledge and innovation spread, strengthen global trade, ensure faster and better co‑ordinated progress towards decarbonisation, and help reduce debt burdens in lower-income countries. Trade and industrial policy choices should strive for more resilient global value chains without eroding the potential benefits for efficiency and innovation, or overlooking the income gains from lowering other trade barriers, especially in services and digital sectors. Faster progress towards decarbonisation is also essential. Innovation is one essential pillar of policy efforts, helping to lower the cost of new technologies. Increasing green and digital infrastructure investment, strengthening standards to enable a reduction in emissions, and raising the scope and level of carbon pricing are other key areas for policy action.