A robust education policy framework is essential for developing human capital and meeting the labour market’s need for a skilled and productive labour force. This chapter, composed of four sub-dimensions, assesses the presence and efficacy of education strategies, legislation, programmes and institutions. The first sub-dimension, equitable education for an inclusive society, examines system governance and the quality of pre-university education starting from preschool. The second, teachers, looks at the selection, initial training and ongoing professional development and management of the teaching workforce. The third sub-dimension, school-to-work transition, focuses on VET governance and the labour market relevance and outcomes of higher education. The fourth sub-dimension, skills for green-digital transition, explores the frameworks and initiatives for fostering green and digital skills in education curricula.

Western Balkans Competitiveness Outlook 2024: Serbia

8. Education policy

Abstract

Key findings

Serbia’s overall score for education policy is slightly higher than the WB6 average (Table 8.1). While there was a small decline in the education policy score since 2021, this is primarily attributed to low performance in the developing area of skills for the green-digital transition, which was evaluated for the first time in this assessment cycle. In other areas, Serbia has witnessed some progress in strengthening system governance, supporting teachers, and improving the labour market relevance and outcomes of education.

Table 8.1. Serbia’s scores for education policy

|

Dimension |

Sub-dimension |

2018 score |

2021 score |

2024 score |

2024 WB6 average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Education |

7.1: Equitable education for an inclusive society |

3.7 |

3.3 |

||

|

7.2: Teachers |

3.5 |

3.1 |

|||

|

7.3: School-to-work transition |

3.3 |

3.4 |

|||

|

7.4: Skills for the green-digital transition |

1.8 |

2.0 |

|||

|

Serbia’s overall score |

2.5 |

3.2 |

3.1 |

3.0 |

|

The key findings are:

Serbia’s performance in Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) 2022 was the highest in the region, and it was the only economy in the WB6 to experience an increase in performance.

The economy has made significant strides in developing a comprehensive education strategy, aligning with international standards and fostering public participation. Moreover, in the past year, statistical and analytical reports have improved the monitoring of the teaching process and the adoption of education policies. However, challenges persist in strengthening the Education Management Information System (EMIS) and implementing a national assessment framework to monitor student learning outcomes effectively.

Serbia has taken positive steps in standardising competency standards and professional development programmes for teachers. However, challenges remain in formalising accreditation systems and implementing comprehensive evaluation mechanisms.

School-to-work transition in Serbia has improved. Employment rates of recent graduates have increased to 72.2% in 2022, one of the highest in the region. In addition, Serbia’s NEET rate (not in education, employment or training, age 15-24 years) is the lowest in the region (13% in 2022).

Strong legislative and strategic frameworks have been established to improve vocational education and align with labour market needs. However, efforts are needed to streamline accreditation procedures and enhance data collection mechanisms.

Digital skills development in Serbia benefits from robust monitoring (through domestic research studies and through participation in the International Computer and Information Literacy Study) and extensive efforts to improve digital infrastructure, such as through the “Connected Schools” initiative. However, while the policy framework guiding digital skills has advanced, the integration of skills for the green transition into education policies requires further attention to adequately prepare for this twin transition.

State of play and key developments

Serbia’s net enrolment rates across all levels of education have been experiencing a downward trend over the past few years. For instance, in primary education, the net enrolment rate has dramatically fallen, from 98.2% in 2019 to 88.6% in 2022 – with the biggest year-to-year change observed between 2021 and 2022 (a 7.7 percentage point decrease). The decline in net enrolment rates in both lower and upper secondary education has been less significant. Lower secondary education enrolment rates fell by 3.3 percentage points (from 98.7% to 95.4%), while upper secondary education enrolment rates decreased by 3.4 percentage points (from 87.2% to 83.8%) between 2019 and 2022. With respect to the latter, this is much lower than the EU and OECD averages, both of which were 93% (UIS, 2023[1]).

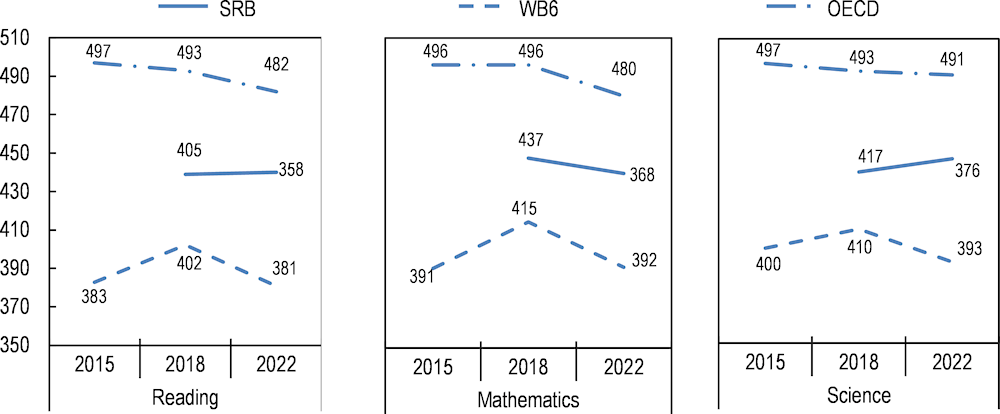

In the 2022 PISA, Serbia scored the highest of all the WB6 economies, although its average scores remain slightly behind the EU and OECD averages (Figure 8.1). Compared to 2018, its performance improved in reading and science by one and seven points, respectively. As such, Serbia stands out as the only economy in the Western Balkans to experience an increase in performance, an accomplishment that is also contrary to the general trend of decline among most OECD countries. However, the average math score dropped by eight points, leading the average PISA score to be about the same as the 2018 assessment results. Moreover, the percentage of low performers (for all three subjects) was 43%, which was the lowest in the region – but notably higher than the OECD average of 25% (Schleicher, 2023[2]). However, 60% of low performers are part of the bottom quarter of ESCS (PISA index of economic, social and cultural status), highlighting the challenges that socio-economically disadvantaged students continue to face in Serbia.

Figure 8.1. Trends in PISA performance in reading, mathematics and science in Serbia (2015-22)

Scores are expressed in points

Note: WB6 average excludes Bosnia and Herzegovina for PISA 2015 and PISA 2022 and excludes Serbia for PISA 2015.

Source:

Source: OECD (2023[3]).

Sub-dimension 7.1: Equitable education for an inclusive society

Serbia has improved its system governance, whose features partially align with EU and OECD education systems. The National Qualifications Frameworks of Serbia (NQFS) – which outlines learning outcomes achieved through formal education programmes as well as non-formal and informal learning – has been referenced to the European Qualifications Framework (EQF) since early 2020.1 In 2021, Serbia adopted a new long-term strategy, the Strategy for Education Development 2030 (SED 2030). The strategy has a clear vision, budget (mostly government funded) and timeline, and was developed in public consultations with a range of stakeholders. SED 2030 is supported by clear Action Plans, the most recent covering the 2023-26 period. Following the national indicator framework, Serbia produces annual progress reports on the Action Plan. By the end of the previous education strategy, Serbia also conducted an ex post evaluation.

While there is an Education Management Information System (EMIS), which gathers in one open data portal all information on institutions, school staff and students within Serbia’s education system, its functionality is limited. The system is not yet interoperable with other national databases to allow monitoring of different aspects of the student population, including underprivileged students (ETF, 2022[4]).2 However, there are ongoing efforts to integrate the EMIS with other systems, such as e-Vrtić or the Fund for Young Talents. The latest Action Plan has laid out measures to improve the EMIS. The scope of data that are systematised and publicly available is constantly increasing on the open data portal. Serbia monitors a range of indicators defined in the education strategy, including information on student learning outcomes available from international assessments and national exams. However, there is no national assessment to help monitor student learning outcomes in line with national curriculum goals, and no comprehensive report on the education system.

Strong legislative and strategic frameworks are in place to help improve the early childhood education and care (ECEC) sector. Namely, it is addressed in the SED 2030, the Law on Pre-School Upbringing and Education and Law on the Foundations of Education System. However, Serbia’s education strategy does not always explicitly address equity or the quality of ECEC, but rather pre-university education more generally. Serbia’s Pre-school Curriculum Framework promotes continuity in education and developing key competencies for lifelong learning. There are clear minimum education requirements for ECEC staff set out in the Law on Pre-School Upbringing and Education and rulebooks that set out professional competencies for staff and professional development. There is an obligation to regularly attend trainings (at least one seminar per year), monitored by the Institute for Education Improvement and the Ministry of Education (MoE). A comprehensive project financed by the World Bank intends to support improvement of quality, equity and access in ECEC in Serbia until March 2024. One of the priorities of the project is to enhance the quality of the preschool system through a holistic approach in supporting the learning, development and well-being of children. While these types of projects are beneficial, they highlight the issue that funding for the ECEC sector remains largely project-based and donor-funded.

The quality evaluation framework and assessment procedures of the work of preschool institutions define 4 areas in which the quality of work is assessed, in 15 standards and 64 indicators. The MoE prepares regular annual reports on monitoring and evaluation of activities in the Action Plan for the Implementation of the SED 2030, and information about the sector is collected through external evaluators of the ministry (pedagogical advisors) and ad hoc ECEC projects. However, there is a lack of data on staff qualification levels and child-staff ratios, which makes it difficult to inform ECEC staff policies.

In its education strategy, Serbia outlines ambitious objectives to enhance the quality of instruction for all while reinforcing the institutional capacities of schools and universities. Serbia has a competence-based curriculum and grade-specific learning standards in place, further aligning education with international best practices. These standards not only facilitate teacher understanding of student learning levels but also inform assessment and lesson-planning processes. The Institute for Education Quality and Evaluation (IEQE), serving as Serbia's Exam Centre, administers central examinations at the culmination of lower secondary education (Grade 8); these national examinations, contingent on satisfactory performance, grant entrance to upper secondary school. In addition, Serbia plans to replace the graduation exam – which is currently taken by all students at the end of upper secondary education (both general and vocational) – with a State Matura. However, the introduction has been postponed for the 2025/26 school year (European Commission, 2023[5]). Serbia's active participation in international assessments such as PISA, TIMSS (Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study), PIRLS (Progress in International Reading Literacy Study), and ICILS (International Computer and Information Literacy Study) generates invaluable insights into student learning outcomes and informs policy decisions. Meanwhile, Serbia’s progress in improving education quality is reflected in its comprehensive school quality framework, robust school evaluation systems and ongoing support provided by the IEQE.

Serbia has strong systems and targeted policies in place to help reduce early school leaving and has among the lowest rates of early school leaving in the region (5.0% versus 9.6% among the EU-27 in 2022) (Eurostat, 2023[6]). Prevention of dropping out of education is recognised as one of the priority areas of the education system of Serbia. Schools apply an early identification and response system to prevent dropout. This system is defined by a protocol designed at the local level that connects the school with the Centre for Social Work, interdepartmental commissions, health centres, misdemeanour judges, local governments and other relevant mechanisms and partners at the local level (Roma co-ordinators, pedagogical assistants, health mediators). However, challenges remain in terms of local self-government resources, especially in rural areas where there is insufficient capacity to answer to different needs of children and parents.

Sub-dimension 7.2: Teachers

Serbia has some elements of an effective system for initial teacher education (ITE), but implementing changes to programme-specific accreditation criteria and ITE entry requirements are areas for further improvement. ITE programmes undergo an accreditation process every seven years, like other tertiary programmes. Hence, there are no specific quality standards for ITE. The National Entity for Accreditation and Quality Assurance in Higher Education (NEAQA) evaluates accreditation applications based on self-evaluation and external quality reports. Nevertheless, these ITE programmes lack comprehensive evaluation, and data to monitor ITE and evaluate the quality of programmes are insufficient.

The SED 2030 includes key objectives and targets for improving teacher selection and ITE. As part of the Action Plan 2023-26, the MoE has introduced a scholarship scheme aiming to attract students to teaching, particularly in fields facing shortages such as mathematics and physics. There are no uniform minimum requirements for entering ITE; it is up to the institutions to specify them. Most commonly, students are ranked following an obligatory and exclusive entrance exam, and their school grade point average (GPA) is considered. Prospective teachers must obtain a master’s degree and pass a certification exam after a one-year probation period. Mentorship is mandatory, and professional development programmes are available.

Since 2021, Serbia has made several advances to bolster the continuous professional development of teachers. These recent changes include the creation and publication of competency standards for the professional (expert) associates in preschool institutions and their professional development; the publication of the new Catalogue of Programmes of Continuous Professional Development of Teachers, Preschool Teachers and Professional Associates; and the creation of competency standards for the secretaries in schools and preschool institutions.

Serbia has a clear career structure for teachers. There are four titles of teachers and professional associates: pedagogical advisor, independent pedagogical advisor, senior pedagogical advisor, and higher pedagogical advisor. Professional teacher standards are used to guide professional development, self-evaluations and design of ITE programmes, and for promotion requests. Despite longstanding plans to develop a new pay grade system to align financial incentives with career advancement, it has not been implemented yet. Salary increases are based only on years of experience. Funding for professional development is decentralised, with municipalities distributing resources based on school plans. Serbia does not mandate recertification for teachers. While there is no formal accreditation system for professional development, the Institute for the Improvement of Education evaluates programmes. Donors support large national training activities, although the government has available resources for the provision of professional development. A range of data is collected to monitor the effectiveness of professional development programmes.

Sub-dimension 7.3: School-to-work transition

Serbia is doing better than most WB6 economies regarding school-to-work transition. Employment rates of recent graduates have increased by almost 8 percentage points in the past five years to 72.2% in 2022, one of the highest in the region. In addition, Serbia’s NEET rate (age 15-24 years) is the lowest in the region (13% in 2022), showing a decrease of 3.5 percentage points from 2018 (Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies, 2023[7]). While the gap with the EU averages has been narrowing, the rates continue to remain slightly behind the 82.4% employment rate of recent graduates, and 9.6% NEET rate (Eurostat, 2023[8]).

VET (vocational education and training) governance has shown significant improvements, but there is still room for further progress in reducing disparities in learning outcomes between VET and general education students. The participation rate in technical and vocational programmes in Serbia has remained relatively stable at 24% of 15–24-year-olds from 2018 to 2022 (UIS, 2023[1]). However, data from PISA 2022 find that students enrolled in VET programmes in Serbia have lower mean performance in mathematics than those in general programmes by 75 points. This difference is the highest of the WB6 economies, and higher than the OECD average score difference of 59 (OECD, 2023[9]).

The MoE plays a pivotal role in ensuring policy coherence across the education system, collaborating closely with the Office for Dual Education and the National Qualifications Framework (ODENQF), established in November 2022. The ODENQF deals with dual education, the National Qualifications Framework and career guidance and counselling at all levels of education. Serbia maintains clear quality standards and regulations for VET programmes, with the new Action Plan 2023-26 emphasising improvements in dual education. Stakeholder engagement through Sector Councils facilitates dialogue and co-operation between the labour and education sectors, informing qualification demand. There are some semi-regular surveys by statistical and employment agencies which provide data on education and skills, although issues such as problematic question formulations and unweighted results have limited their efficacy. The Law on Dual Education outlines the work-based learning (WBL) framework, with all dual VET programmes incorporating WBL components. In 2023, amendments to the law were adopted, streamlining employer accreditation procedures, and strengthening support for apprenticeships and other WBL opportunities.

While the new education strategy aims to comprehensively address quality assurance in higher education (HE), challenges remain in aligning accreditation standards with the National Qualifications Framework (NQF). There are growing efforts to engage social partners, promote internationalisation, and co-ordinate government actions to enhance the relevance and quality of Serbia’s higher education sector. The new education strategy places greater emphasis on quality assurance in HE, targeting improved supply, human resources, outcomes, enhanced relevance at the national and international levels, and increased coverage and equity. As a full member of the EU Erasmus+ programme, Serbia actively promotes internationalisation in its higher education sector. Quality assurance and accreditation processes, aligned with the NQF, are overseen by the National Entity for Accreditation and Quality Assurance in Higher Education (NEAQA). While efforts are under way to align accreditation standards with NQFS descriptors and include National Qualifications Framework of Serbia (NQFS) and European Qualifications Framework (EQF) levels in diplomas, these initiatives are in the planning stage. Co-ordinating across government bodies and stakeholders, including the MoE, the National Council for Higher Education and NEAQA, ensures comprehensive oversight of the HE sector. Amendments to the Serbian Law on Higher Education in 2021 have incorporated labour market representatives into NEAQA's organs, fostering alignment with employment needs.

Data collected from various sources, including the Ministry of Labour, Employment, Veteran and Social Affairs (MoLEVSA), the Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Serbia, and the Statistical Office, informs employer surveys and labour market outcomes. However, data on skills mismatches are not reliable and irregular. While publicly available data on employment trends are accessible, detailed labour market outcome data for HE institutions and programmes are pending release on the open data portal.

Sub-dimension 7.4: Skills for the green-digital transition

There is a policy framework in place for the development of basic digital skills in the primary and secondary education system and legislation has been adopted and aligned to international standards. The education strategy aims to establish the foundations for the development of digital education at the pre-university level (Box 8.1). The implementation of this framework is guided by the Action Plan 2023-26 for the Strategy for Education Development until 2030, with progress measured through monitoring outputs and assessing them against target benchmarks and indicators.

Box 8.1. Digital skills development in Serbia

Digital World

Digital World has been a mandatory school subject in Grades 1 to 3 since the 2021/21 school year, targeting pupils aged 7-10. As stated in the curriculum, the overall goal of this subject is to develop students’ digital competencies that enable them to use digital devices safely and correctly for learning, communication, co-operation, and the development of algorithmic thinking. The subject has 36 school hours per year and is structured around three teaching areas: digital society, safe use of digital devices, and computational thinking. Digital World curricula for Grade 4 are being developed. A working group consisting of various experts in computer science, education psychology, curricula development and pedagogy has been established to discuss, design, and propose the new curricula.

Computer science

Computer Science has been a mandatory school subject, with 1 teaching hour per week, from Grades 5 to 8 since the 2017/18 school year. As stated in the curriculum, the overall aim of the subject is to enable students to manage information, safely communicate in the digital environment, and be able to create digital content and effectively use computer programmes.

In all four grades, the subject is structured around three teaching areas: (basic) information, communication and technology (ICT) skills, information literacy, and computational thinking. Within the field of computer science, an important innovation is the development of programming skills. In Grade 5 students learn visual programming languages, while from Grade 6 students learn textual programming languages (e.g., Python).

Serbia developed its educational standards fifteen years ago for 10 subjects in compulsory education,1 and digital literacy was not among them. Hence, work is currently under way to adopt and promote recently defined digital literacy general subject competence and quality standards for the end of compulsory education.

Computer Science is also a mandatory subject in secondary education for students aged 15-19, to continue deepening the knowledge developed in previous years. The number of years (1-4) and teaching hours per week (1-3) vary based on whether it is taught in general or vocational secondary education.

1. It is important to note that Serbian compulsory education has a single structure that includes both primary and lower secondary education levels, which corresponds to levels 1 and 2 of the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED).

Source: Information provided by the MoE as part of the Competitiveness Outlook 2024 assessment framework.

Several initiatives aiming to improve schools’ connectivity have been implemented in the past few years. One example was the “Bridging the Digital Divide in Serbia for the Most Vulnerable Children” project, which was jointly implemented by the MoE and UNICEF from November 2020 to September 2023. By the conclusion of this programme, 30 primary schools benefited from the provision of new tablets and laptops, while more than 900 teachers received training to strengthen their digital and pedagogical competencies (UNICEF, 2023[10]). Another prominent programme has been the European Investment Bank’s “Connected Schools” project, which aimed to provide equal opportunities and empower young people with digital skills through installing high-speed Internet connections at 3 800 schools, providing modern computer equipment, and training both students and teachers on digital skills (Kovacevic, 2024[11]). Yet, most of these programmes have not been matched with any regular or consistent monitoring of key indicators related to digital skills.

Stakeholders from the private sector and academia regularly contribute to curricula development. The ICT sector industry is represented in meetings for digital skills development. The development of digital skills among teachers in Serbia is addressed as a transversal key competence. Empowering teachers to become confident and skilled in using digital technology to support learning in an online environment is supported through an official Digital Competence Framework for Teachers – Teacher in Digital Age (revised in 2023), an Instrument for Self-Reflection (available on line), various in-service teacher training programmes, and open educational resources.

There is no separate framework within the MoE for the agenda of the development of skills for the green transition, yet a number of initiatives aim to increase students’ awareness of preparing for the green transition. The Law on Foundations of the Education System generally formulates the formal expectations regarding the promotion of knowledge, skills and attitudes needed for a greener and more sustainable economy. One of the defined educational outcomes is to “effectively and critically use scientific and technological knowledge, while showing responsibility towards one's life, the life of others and the environment”. Cross-curriculum competences include a responsible attitude towards the environment. There are elective programmes related to this theme that are part of the teaching and learning plan, such as Life skills, My environment, Let’s save our planet, Nature keepers in primary school, and Education for sustainable development in high school. While the existing framework serves as a basis for integrating skills for the green transition into education, further efforts will be needed to adequately prepare for the challenges associated with the green transition.

Overview of implementation of Competitiveness Outlook 2021 recommendations

Serbia’s progress on Competitiveness Outlook 2021 Recommendations for education policy is generally moderate (Table 8.2). Despite the adoption of a long-term education strategy and the development of action plans, Serbia has yet to strengthen its monitoring framework as recommended. Additionally, progress in providing teachers with stronger incentives for professional development and in implementing plans to enhance data collection and management is still lacking.

Table 8.2. Serbia’s progress on past recommendations for education policy

|

Competitiveness Outlook 2021 recommendations |

Progress status |

Level of progress |

|---|---|---|

|

Ensure the new education strategy has a clear set of priorities and a strong monitoring framework |

Serbia has adopted a long-term strategy for the education system: the Strategy for Education Development has a clear set of priorities. As part of the strategy, three-year action plans are developed. The content of the action plans will be entered into the Unified Information System, to improve monitoring. |

Moderate |

|

Provide teachers with stronger incentives to develop their practice |

There is no evidence of progress. |

None |

|

Implement plans to strengthen the collection and management of data |

One of the objectives of the new Strategy for Education Development is to improve the EMIS. The process of data entry by institutions of all levels of education is already under way. The following were completed: register of institutions, employees, children, pupils, adults and students; register of curricula, register of study programmes and register of NQF; functional operations and creation of statistical, analytical and summary reports within the system. The data will be published on the open data portal on a monthly basis. |

Moderate |

The way forward for education policy

Given the mixed level of progress in implementing previous recommendations, there are still areas in which Serbia could enhance its education policy framework and programmatic support. As such, policy makers may wish to:

Implement plans to continue enhancing the functionality of the Education Management Information System (EMIS) and establish a robust national assessment framework aligned with curriculum goals. While most ongoing efforts to integrate the EMIS with other information systems have concluded, there is still scope to further draw from the platform to improve education policies and outcomes. Namely, additional reforms could ensure comprehensive data collection and effective monitoring of educational progress, promoting equity and inclusivity in the education system as well as enhanced capacities for evidence-based policy making. This data could then be used to provide feedback on student performance and progress as well as allow for comparisons at the individual, class or school level.

Encourage teachers to progress professionally through stronger incentives. As reward mechanisms for teachers are lacking, the link between teachers’ performance and both monetary and non-monetary rewards should be established to provide teachers with additional incentives to update their skills, knowledge, and practice. Regarding monetary incentives, Serbia should prioritise the swift implementation of the planned pay grade system. Conversely, the establishment of a formal accreditation system for teacher professional development programmes can serve as a non-monetary reward that encourages continuous improvement in teacher quality and supports ongoing professional growth.

Improve the relevance of higher education by analysing the skills mismatches and subsequently limiting publicly funded study places in lower-demand fields. While Serbia plans to conduct an analysis of the skills that are lacking in the labour market, it could also conduct analyses of the oversupply of skills, particularly in higher education. Adjusting the number of study places for students in publicly funded HEIs, particularly by reducing them in fields where the supply is too large, could help reduce the surplus of certain profiles (Box 8.2).

Continue to invest in enhancing digital skills among students and teachers. Although mechanisms such as the ICILS (which tracks digital skills levels of students) and monitoring by the MoE (for measuring digital skills among teachers) are in place, there is room to expand efforts to further strengthen these skillsets. Building these digital competencies will not only prepare students for the future job market but also equip Serbia with the skills needed to thrive.

Box 8.2. Limiting publicly funded study places in Scotland

In Scotland, the government has introduced several policies that aim to reduce the number of study places at universities that are supported by public funding. For students who are Scottish residents and are pursuing their first university degree, their tuition fees are entirely covered, although universities receive variable subsidies per student that depend on each student’s field of study. However, students who wish to receive another undergraduate degree must pay an annual rate of EUR 2 130 (GBP 1 820). The exception is for individuals seeking to receive this second degree in high-demand fields, such as healthcare (including paramedic, nursing, or midwifery studies) or teaching, as these are eligible for full funding.

Source: OECD (2023[12]).

References

[4] ETF (2022), Country Brief - Serbia, Integrated Monitoring Process of the EU Council Recommendation on VET and the Osnabrück Declaration, https://www.etf.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2022-06/Country%20Brief_Serbia_edited%20%281%29.pdf.

[5] European Commission (2023), Commission Staff Working Document, Serbia 2023 Report, https://neighbourhood-enlargement.ec.europa.eu/document/download/9198cd1a-c8c9-4973-90ac-b6ba6bd72b53_en?filename=SWD_2023_695_Serbia.pdf.

[6] Eurostat (2023), Early Leavers from Education and Training by Sex and Labour Status, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/edat_lfse_14/default/table?lang=en.

[8] Eurostat (2023), Young People Neither in Employment nor in Education and Training (15-24 Years), https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tipslm90/default/table?lang=en&category=t_educ.t_educ_outc (accessed on 1 March 2024).

[11] Kovacevic, G. (2024), Digital Education in Serbia, European Investment Bank, https://www.eib.org/en/stories/digital-education-serbia (accessed on 20 March 2024).

[3] OECD (2023), PISA 2022 Results (Volume I): The State of Learning and Equity in Education, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/53f23881-en.

[9] OECD (2023), PISA 2022 Results (Volume II): Learning During – and From – Disruption, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/a97db61c-en.

[12] OECD (2023), The Future of Finland’s Funding Model for Higher Education Institutions, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/3d256b59-en.

[2] Schleicher, A. (2023), PISA 2022: Insights and Interpretations, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/pisa/PISA%202022%20Insights%20and%20Interpretations.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2024).

[1] UIS (2023), UIS.Stat, http://data.uis.unesco.org/ (accessed on 1 March 2024).

[10] UNICEF (2023), New Equipment and Support for 30 Primary Schools - Students and Teachers a Step Closer to Digital Education, https://www.unicef.org/serbia/en/press-releases/bridging-the-digital-divide-project-wrap-up-conference (accessed on 20 March 2024).

[7] Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (2023), SEE Jobs Gateway, https://data.wiiw.ac.at/seejobsgateway-q.html (accessed on 1 March 2024).

Notes

← 1. Investments are being made in improving the information and communication technologies infrastructure and school connectivity, but the EMIS is still not fully operational. The EMIS should be designed to be interoperable with other national databases to maximise monitoring potentials and to enable the monitoring of different aspects of the student population, including underprivileged students. The EMIS is also expected to enable better co-ordination of stakeholders by new methodologies for data collection, as well as ensuring the validity and reliability of data and their regular updating (ETF, 2022[4]).

← 2. The open data portal (in Serbian) can be accessed at: https://opendata.mpn.gov.rs. The portal contains data for all levels of education, including dual and adult education, average job search duration for different educational profiles, and similar information.