Effective trade policy is vital for regional integration and alignment with the European Union. This chapter examines how the government of Serbia uses trade policy to ease market access and harness digitalisation for enhanced trade facilitation. The first sub-dimension, trade policy framework, assesses the government’s ability to formulate, implement and evaluate trade policy, examining the institutional formulation and co-ordination of trade policy, public-private consultations, and the network of free trade agreements. The second sub-dimension, digital trade, focuses on the legal framework for digital trade policy and digital trade facilitation and logistics. The third sub-dimension, export promotion, explores the effectiveness of export promotion agencies and programmes, especially in the context of deepening regional integration.

Western Balkans Competitiveness Outlook 2024: Serbia

3. Trade policy

Abstract

Key findings

Serbia’s score on trade policy remained the same as the 2021 assessment cycle (Table 3.1), mainly because of underperformance in digital trade facilitation, owing to deficiencies in domestic legislation. By contrast, some progress has been achieved, especially in the trade policy framework and public-private consultations.

Table 3.1. Serbia’s scores for trade policy

|

Dimension |

Sub-dimension |

2018 score |

2021 score |

2024 score |

2024 WB6 average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Trade |

2.1: Trade policy framework |

4.5 |

4.4 |

||

|

2.2: Digital trade |

3.3 |

3.8 |

|||

|

2.3: Export promotion |

3.8 |

3.6 |

|||

|

Serbia’s overall score |

3.3 |

3.8 |

3.8 |

3.9 |

|

The key findings are:

Despite improved inclusivity and access to the public-private consultation process through the digital eConsultations portal, public-private consultations remain underused. In 2022, consultations occurred for only 29% of draft laws and 30% of draft regulations.

There have been advances in digitalising trade, with the eCustoms programme standing out as a noteworthy initiative expected to enhance the efficiency of customs procedures by digitalising the border processes. Nonetheless, monitoring and evaluation of digital measures are underdeveloped.

On the back of the strengthened legal and strategic framework for digital trade, e-commerce volumes have increased, with the e-commerce channel accounting for 28.9% of total business sales in 2023, marking the highest percentage in the region.

Serbia has strengthened its digital trade policy, having advanced in aligning its digital trade laws with best international practices.

Serbia is the only economy in the region to track carbon emissions from trade in line with OECD best practices, but the data are not yet available on line.

Limited export capacity remains challenging among companies, signalling a need for intensified capacity-building efforts.

State of play and key developments

Since 2015, Serbia has experienced consistent growth in its exports of goods and services. In 2023, the positive trend in exports persisted, registering a year-on-year increase of 3.7%. This growth was primarily fuelled by a boost in manufacturing exports. Additionally, services exports saw a substantial rise of 18.1% compared to the previous year, driven by the information and communication technology (ICT), transportation, and business services sectors (National Bank of Serbia, 2024[1]).

The EU remains Serbia’s biggest trade partner, accounting for 64.6% of total exports in 2023. Serbia mainly trades with certain EU Member Countries, with Germany being the top partner for both imports and exports. Other partners include Italy, Hungary, and Romania. In 2023, around 15.1% of Serbia’s exports went to Germany, 6.9% to Bosnia and Herzegovina and an additional 6.2% to Italy. On the import side, 13.1% came from Germany, and 12.2% from China, overtaking Italy as the second-biggest import source in 2023 (National Bank of Serbia, 2024[1]).

Serbia has been in the process of a considerable structural transformation, which is reflected in the economy’s latest score on the economic complexity index.1 The heightened economic complexity can be attributed in part to a rise in the export of high-knowledge goods and services, particularly in the field of ICT. Partially supported by the influx of Russian citizens, in 2023, Serbia’s ICT service exports amounted to EUR 2.6 billion (USD 2.8 billion), which amounts to 24.4% of total service exports, exceeding the OECD average of 13.2% and the EU average of 16.8% (World Bank, 2023[2]).

Sub-dimension 2.1: Trade policy formulation

Serbia has a well-established legal framework for trade policy formulation, further improved by its strong inter-institutional co-ordination. Collaboration among expert groups, co-ordination bodies, and civil society engagement is led by the Ministry of Trade, Tourism, and Telecommunications, which has been restructured into the Ministry of Domestic and Foreign Trade in 2022. The primary objective behind this restructuring was to pivot towards a strategic emphasis on trade, making it the central focus of the ministry's mission and activities. The ministry is supported by the National Coordination Body for Trade Facilitation (NCBTF), which meets at least twice a year.2 It plays a crucial role in co-ordinating initiatives across diverse stakeholders, including government agencies, organisations, the business community, and other foreign trade stakeholders. Four expert working groups have been established and are in charge of approving the action plans.

The NCBTF implemented the 2022-23 Action Plan, which included further harmonisation of technical regulations with European Union legislation, streamlining of mandatory documents and shipment procedures, mutual recognition of certificates, increased connectivity between different customs authorities, and establishment of a National Single Window. Despite the established results indicators for each of the activities, their quantifiability varies in scope.3 Similarly, the evaluation of the trade policy formulation mechanism follows a systematic approach, with strategies and programmes undergoing assessment no later than 120 days after their expiration. The final report must be submitted within six months of its validity expiration. Adjustments to the trade policy formulation mechanism are then made based on the results of these evaluations, and often include the revision of quota reductions and extension or elimination of a particular trade measure.

Serbia is one of the only Western Balkan economies that has made strides in estimating the environmental impact of trade. Due to its size and the industrial nature of its trade flows, Serbia is expected to have higher total carbon emissions related to trade compared to smaller economies with less industrial trade compositions (WTO, 2021[3]). In line with OECD best practice,4 Serbia collects data on trade-related carbon emissions; however, they are not available on line at the time of writing, highlighting an area for potential improvement in transparency and accessibility.

Serbia has a well-developed framework for public-private consultations, which has further improved thanks to leveraging digitalisation. The adoption of the Law on the Planning System 2018 and subsequent amendments to the Law on State Administration in 2018 have mandated public-private consultation processes at all stages of developing public policy legislation; the emphasis is on early public participation in the preparation of laws, regulations, and acts, including those related to trade. When a new or changing regulation is adopted, the proponent of the regulation is obliged to conduct consultations with interested parties as well as conduct a public debate. Notably, every year, each ministry is involved in policy formulation, including trade, plans for organising public-private consultations, and a budget for these purposes according to the yearly allotments. There was an almost fourfold decrease of the budget allocated to public-private consultations,5 due to digitalisation (Box 3.1).

In June 2021, the government approved the establishment of the “eConsultations” portal, which serves as a platform for electronic consultations and public discussions of legal documents and strategies, including for trade policies. While the implementation of the eConsultations portal has improved the consultation process for each regulation and public policy document, its use remains limited at the local level among public institutions, and no oversight body has been established to determine the effectiveness of public-private consultations. Moreover, while public consultations were carried out for every draft policy planning document in 2022, such consultations occurred for only 29% of draft laws and 30% of draft regulations (European Commission, 2023[4]). The limited use of public-private consultations in the digitalised format can be partially attributed to the local governments’ limited capacity, including staffing, technical resources, and equipment. Effectively implementing new digital solutions can then pose a challenge without additional support in the form of funding, personnel, and training.

Box 3.1. eConsultations in Serbia

The “eConsultations” portal was formally launched in December 2021 and led to enhanced efficiency, transparency, and inclusivity in the trade policy-making process.

The process of public discussion commences with a public announcement posted on the proponent’s website and the eConsultations portal. There is a 15-day window for individuals to submit their initiatives, proposals, suggestions, and comments in writing or electronically from the start of the public announcement. The public discussion period must be extended for a minimum of 20 days. The proponent is required to provide a report on the outcomes of the public discussion on both its website and the eConsultations portal, and this report should be made available no later than 15 days after closure. The introduction of eConsultations streamlined the submission of trade-related documents for public comments.

The improved and digitalised public-private consultation process facilitates efficient two-way communication between government entities and private stakeholders. This improved communication helps clarify policy objectives and address concerns from groups potentially affected by the proposed measure.

Source: Government of Serbia (2024[5]).

In the second quarter of 2024, the eConsultations platform is set to undergo an update that will introduce a new functionality, allowing the evaluation of consultations in alignment with predefined indicators. This enhancement is poised to further refine and streamline the evaluation process, enhancing the effectiveness and responsiveness of public engagement in the policy-making arena. Additional explanations on the trade measures are currently missing on the platform; publishing them alongside information about the implications of planned trade measures would benefit potential exporters (UNECE, 2021[6]).

Despite improvements in the digitalisation of the public-private consultation process, some temporary trade restrictions were introduced unilaterally and without consultation with the trade community. This contributed to the lack of predictability for the business environment and the reduced reliability of supply chains (European Commission, 2023[4]). Following the start of the Russian war of aggression against Ukraine, Serbia intermittently imposed temporary trade restrictions in 2022, including export bans or quotas on various products. These measures, encompassing agricultural goods, milk and butter products, certain raw wood items, raw wood quotas, wood pellets, diesel fuel and natural gas, were all rescinded during the course of 2023, although new restrictions were introduced in March 2024.

Since the last assessment cycle, Serbia has expanded its network of free trade agreements (FTAs), with two entering into force in 2021, such as the one with the Eurasian Economic Union.6 The recent FTA that came into force is the United Kingdom-Serbia Partnership, Trade and Cooperation Agreement in May 2021. The agreement covers a wide range of topics: trade in goods, including provisions on preferential tariffs, tariff rate quotas, rules of origin, trade in services, and intellectual property, covering geographical indications, and government procurement. In October 2023, Serbia signed an FTA with China, which will most likely enter into force in June 2024. The Serbia-China free trade agreement covers over 10 000 tariff lines for each economy. Initially, 66% of traded goods will be tariff-free, with phased liberalisation for the rest: some after five years, others after ten or fifteen years, and the 10.1% remaining excluded. The agreement particularly benefits agricultural producers, especially fruit exporters who will be able to export to China without tariffs, and will have a positive impact on the metal, machinery and pharmaceutical sectors. Given that bilateral trade volume between Serbia and China amounted to almost EUR 6 billion in 2022 (Serbian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2022[7]), the FTA can further boost bilateral trade by reducing additional trade barriers and costs. In September 2023, Serbia started negotiations on a bilateral FTA with the United Arab Emirates, while negotiations with South Korea are due to start at the end of 2024. In 2022, Serbia also announced plans for an FTA with Egypt. The negotiations have been formally launched; however, no official negotiation rounds have taken place at the time of writing. Despite the expansion in its network of multilateral and bilateral FTAs, progress on finalising WTO accession has been limited.

Sub-dimension 2.2: Digital trade

Since the last assessment cycle, Serbia has boasted a robust e-commerce policy framework and has undergone significant revisions in response to the evolving digital trade sector. Digital trade policy is within the competency of multiple entities, including the Ministry of Internal and Foreign Trade, the Ministry of Information and Telecommunications, the National Bank of Serbia, the Customs Administration, the Ministry of Finance and the Statistical Office of Serbia. Serbia's institutional framework facilitates efficient co-ordination among these ministries and agencies concerning digital trade policy formulation.

In December 2021, the enactment of the new Consumer Protection Law laid the foundation for enhancing the performance of online businesses in Serbia. Additionally, the 2021 amendment to the Law on Electronic Document, Electronic Identification, and Trust Services in Electronic Business introduced standardised regulations concerning electronic documents, electronic contracts, electronic identification systems, and qualified trust services (Ministry of Trade, Tourism, and Telecommunications, 2021[8]). The Law stipulates that public authorities communicate through electronic means, following the legal framework established for general administrative procedures and electronic administration. The provision also includes mention of a "qualified electronic delivery service", which suggests that a recognised and authorised electronic service is used to facilitate these communications. This service likely ensures the security, authenticity, and reliability of electronic transmissions between the public authorities and the involved parties (Ministry of Trade, Tourism, and Telecommunications, 2021[8]). While not directly trade-related, this regulation has implications for digital trade as the streamlined and legally compliant electronic communication and delivery processes between public authorities and parties create a more conducive environment for efficient and secure digital transactions.

These laws are part of a larger framework encompassing national digitalisation strategies, specifically the Information Society and Information Security Development Strategy 2021-26, and the Strategy of Digital Skills Development 2020-24. Both of these strategies are geared toward promoting digital transformation in both public and private sectors, fostering economic growth that aligns with EU objectives. This enhanced policy framework for digital trade is likely to have played a role in boosting e-commerce activity. Notably, the share of e-commerce sales for enterprises witnessed a rise, increasing from 27% in 2021 to 28.9% in 2023, marking the highest percentage among the Western Balkan economies (Eurostat, 2023[9]).

Serbia is proactively aligning its digital trade legislation with the pertinent EU acquis. A significant portion of Serbia's digital trade regulations has already undergone harmonisation, signifying substantial progress in this endeavour. Currently, there are ongoing efforts to bring remaining regulations that impact digital trade into conformity with EU norms. Notably, the Law on Postal Services is scheduled to be harmonised by the end of 2024, indicating a dedicated approach to ensuring that all aspects of digital trade are consistent with European standards.

However, despite the developed policy landscape governing e-commerce, further enhancing compliance with the EU Digital Services Act and Digital Markets Act is crucial in the e-commerce sector to ensure predictability for the business community (European Commission, 2023[4]). With that goal in mind, Serbia also improved in solving commercial disputes on line, with the information system for alternative dispute resolutions launched in July 2022 by the Ministry of Domestic and Foreign Trade. The online platform for alternative dispute resolution is in the process of implementation with feasibility studies and a training needs assessment launched in late 2023. A shortcoming previously addressed in Competitiveness Outlook 2021, the lack of an online dispute resolution (ODR) mechanism in Serbian legislation, contributed to the lack of consumer confidence in the digital economy and further restricted trade in services (OECD, 2021[10]). ODR can enhance the accessibility of legal proceedings by expediting and reducing the cost of court access, ultimately enhancing the effectiveness and efficiency of dispute resolution, including in disputes arising from digital trade (Council of Europe, 2021[11]).

The Statistical Office of Serbia issues annual e-commerce performance indicators. These reports encompass data on enterprises that employ computers or the Internet for business activities. Additionally, the National Bank of Serbia releases information pertaining to e-commerce, including details on payment transactions for online purchases of goods and services. However, the official register of legal business entities in Serbia does not provide information regarding whether a specific legal entity engages in online sales. Additionally, the absence of an official database for e-commerce businesses further complicates the availability of such information.

While Serbia made progress in reinforcing its digital trade policy framework, its regulation on facilitating cross-border data flows leaves room for further development. Considering the progressing digital transformation, global trade and related production rely significantly on the seamless flow, storage, and use of data, both locally and internationally. Similarly, integration into global value chains heavily relies on a cross-border flow of data. In the context of international trade, regulations impacting the ability to exchange and transfer data across borders are of special significance. These regulations may appear as prerequisites for cross-border data transfers or stipulations regarding local storage (Casalini and López González, 2019[12]). Since 2020, Serbia has been a signatory to the Council of Europe’s Convention 108+, which ensures the protection of individuals regarding the processing of personal data.

Regulating cross-border data flows is becoming increasingly prevalent in designing trade policy; trade agreements progressively contain binding provisions on cross-border data flows, consumer protection and protection of personal data. In fact, when used as a proxy for cross-border data flows, digital connectivity has shown complementarity with trade agreements, which results in up to a 1.5% increase in international trade for each 1% increase in bilateral digital connectivity (López González, Sorescu and Kaynak, 2023[13]). While four of the free trade agreements7 in force for Serbia contain provisions involving digital trade and e-commerce, only two8 contain provisions on data protection. A positive signal is that one of these agreements, the Partnership, Trade and Cooperation Agreement with the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, is recent, having been signed in 2021, reflecting the growing importance of the digital economy and technology in international trade and the recognition that traditional trade rules need to be updated to address the unique challenges and opportunities presented by the digital age. However, there is room for improvement in including provisions on the free movement of data, establishing a mechanism to address barriers in data flows, and banning or limiting data localisation. Currently, none is included in Serbia’s free trade agreements currently in force (Burri, Vasquez Callo-Müller and Kugler, 2022[14]).

Serbia focuses on drawing from digital technologies to streamline cross-border transactions, reduce trade barriers, and enhance the efficiency of customs and regulatory processes. As such, it has readily progressed on the implementation of digital trade facilitation measures, which has partially contributed to improvements under the OECD Trade Facilitation Indicators (Box 3.2).

Box 3.2. Serbia’s performance under the OECD Trade Facilitation Indicators

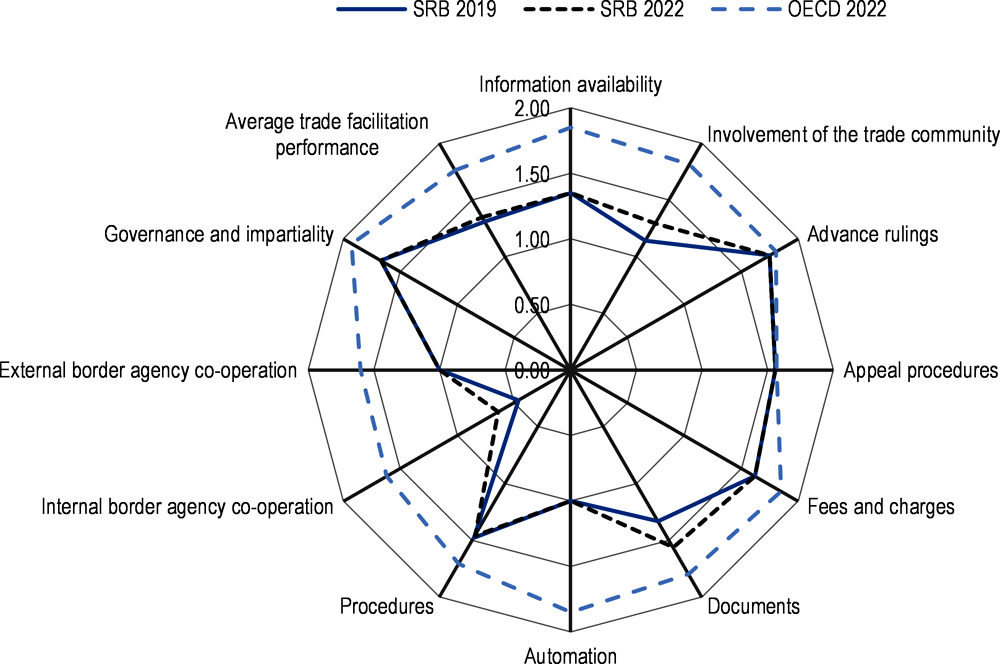

To support governments in streamlining their border procedures, cutting trade costs, boosting trade volume, and maximising benefits from international trade, the OECD has developed a series of Trade Facilitation Indicators (TFIs) as indicated in Figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1. Trade Facilitation Indicators for Serbia and the OECD, 2019 and 2022

Note: These indicators pinpoint areas for improvement and enable impact assessment of potential reforms. Covering a comprehensive range of border procedures, the OECD indicators apply to over 160 countries, spanning various income levels, geographical regions, and developmental stages. Utilising estimates derived from these indicators allows governments to prioritise trade facilitation initiatives and strategically channel technical assistance and capacity-building efforts for developing nations. Moreover, the TFIs serve as a tool for economies to visualise the status of policy implementation across different areas and measures outlined in the WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement. The assessment is conducted every three years.

Source: OECD (2022[15]).

Since 2019, Serbia improved in only three of the eleven indicators: involvement of the trade community, documents, and internal border agency co-operation. Despite improvements in some of the TFIs, Serbia’s scores remained stagnant in seven of the indicators and deteriorated in one, which covers procedures, such as the streamlining of border control (inspections, clearance), implementation of trade single windows, or certified trader programmes. Serbia outperformed the Western Balkan region in terms of information availability, advance rulings, appeal procedures, documents, procedures, external border co‑operation, governance, and impartiality. The economy’s average trade facilitation performance is on par with the Western Balkan average. Despite positioning itself as one of the leaders in the region, Serbia still lags behind the OECD average under all of the assessed indicators.

In June 2023, the Customs Administration began implementation of the e-Customs initiative, which entails AIS (Automated Import System), AES (Automated Export System), and CDMS (Customs Decisions Management System). These three systems are progressing as scheduled and are expected to go live in December 2025 and become fully operational in 2026. The primary goal of this project is to achieve compatibility of customs procedures with the European Union. This alignment will not only optimise the efficiency and effectiveness of customs operations but also mark a noteworthy advancement in the continuous drive to digitalise and modernise all aspects of customs procedures. Moreover, Serbia partially implemented the electronic exchange of sanitary and phytosanitary certificates, including SMEs in the Authorized Economic Operators’ programme, and partially implemented trade facilitation measures for digital trade, such as provisions in new free trade agreements. Serbia is also actively developing an Electronic Single Window, with the initial target completion date set for the end of 2025. The Electronic Single Window will enable the electronic exchange of customs declarations, and other relevant trade documents; currently the Customs Administration of Serbia does not have electronic systems in place for the exchange of Certificates of Origin.

Despite progress, there is no monitoring and evaluation mechanism in place for digital trade facilitation measures, which implies a lack of assessment of the effectiveness, impact, and progress of initiatives related to facilitating digital trade. Without such mechanisms, it becomes hard to gather insights into the success or shortcomings of digital trade facilitation efforts, hindering the ability to optimise policies.

In the area of adhering to international instruments governing digital trade, Serbia has yet to ratify key instruments, including the UN Electronic Communications Convention and the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) Model Law on Electronic Commerce, which advocate for standardising national laws governing e-commerce transactions. These instruments play a crucial role in establishing regulatory standards for e-transaction frameworks, e-authentication, e‑signatures, and electronic contracts (OECD, 2021[16]). Additionally, Serbia has not aligned with the OECD Recommendation on Consumer Protection in e-commerce, which outlines general principles for customer protection and encourages collaboration among consumer protection authorities. While Serbia's legal framework supports electronic transactions, aligning domestic legislation with international standards is essential for credibility in the global digital economy. This alignment not only opens doors to broader markets and increased international trade but also promotes interoperability, allowing Serbian businesses to engage seamlessly in cross-border transactions and collaborate with global partners.

Table 3.2. OECD Digital Trade Inventory

|

Instrument |

Description |

Serbia’s adherence |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

E-transaction frameworks |

JSI Participant |

World Trade Organization (WTO) Joint Statement Initiative comprises a discussion on trade-related aspects of e-commerce, including cybersecurity, privacy, business trust, transparency, and consumer protection. |

|

|

UN Electronic Communication Convention |

Convention encourages the standardisation of national laws and regulations governing e-commerce transactions. |

|

|

|

Consumer protection |

OECD Recommendation of the Council on Consumer Protection in e-commerce |

The OECD Recommendation on Consumer Protection in e-commerce provides guidelines and recommendations for member countries to enhance consumer protection in this area. The recommendations typically cover various aspects of online transactions to ensure that consumers can engage in e-commerce with confidence and trust. |

|

|

Paperless trading |

WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement |

The Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA) includes clauses aimed at accelerating the transit, release, and clearance processes for goods, encompassing those in transit, and outlines measures for fostering efficient collaboration between customs and relevant authorities concerning trade facilitation and customs compliance matters. |

|

|

Cross-border data transfer/Privacy |

Convention 108 |

Convention for the Protection of Individuals with regard to Automatic Processing of Personal Data is the first legally binding international treaty dealing with privacy and data protection. |

|

|

2001 Additional Protocol to the Convention |

The Additional Protocol reinforces the protection of individuals’ rights in the context of automated processing of personal data and encourages international co-operation on privacy and data protection matters. |

|

|

|

Convention 108+ |

2018 Amending Protocol to Convention 108 updates the provisions on the flow of personal data between signatories. |

|

|

|

Cybersecurity |

Convention on Cybercrime of the Council of Europe (Budapest Convention) |

An international treaty aimed at addressing crimes committed via the Internet and other computer networks. It serves as a framework for international co‑operation in combating cyber threats and promoting a harmonised approach to cybercrime legislation. |

|

|

Goods market access |

Information Technology Agreement |

The Information Technology Agreement, on a most-favoured-nation basis, removes tariffs for a broad range of IT products, including computers and telecommunications equipment. |

|

|

Updated ITA concluded in 2015 |

Covers the expansion of products covered by the Information Technology Agreement by eliminating tariffs on an additional list of 201 products. |

|

Note: Regarding the WTO Trade Facilitation instrument, Serbia cannot adhere to it until it becomes a WTO member.

Source: OECD (2021[16]).

Sub-dimension 2.3: Export promotion

Serbia further scaled up its efforts to promote exports, solidifying its position as a frontrunner in this domain. The Development Agency of Serbia (RAS) serves as the economy’s export promotion agency and offers a range of business support services. RAS’s activities are complemented by the Serbian Export Credit and Insurance Agency (AOFI), which is responsible for the insurance and financing of exports for Serbian export-oriented companies, and the Chamber of Commerce and Industry, assisting in the broader internationalisation of Serbian companies.

Despite RAS’s broad scope of activities, the agency’s budget for export promotion remained limited. However, there has been an over twofold increase in the staff since 2020 when just five employees were working on the Export Promotion Programme, to twelve in 2022, the highest number in the Western Balkan economies. The government is responsible for approving RAS's budget and the programme framework, but the organisation has autonomy in how it carries out the implementation of its programmes and projects. The additional expansion would fulfil the new goals set in the Export Promotion Programme. These include indicators on the quantity of public calls issued; the proportion of programme beneficiaries achieving their first export within a year of programme implementation; the percentage of beneficiaries experiencing export growth of at least 20% compared to the year before programme implementation; and improvements in productivity. RAS’s target achievement is monitored through evaluation conducted by RAS’s planning and analysis division, which is separate from the support for SMEs division, responsible for export promotion. Nevertheless, the reports on the agency’s export promotion programmes are not published, hindering further monitoring and evaluation.

RAS supports companies through two main export promotion programmes. The Export Promotion Programme was launched in 2020, and since its inception, four public calls for participation in the programme have been issued, the latest one having been published in December 2023. This programme is funded exclusively from the national budget.9 As part of the programme, skilled RAS personnel carry out diagnostics of export capabilities for the programme’s beneficiaries and assist companies in increasing their export volumes through international trade fair participation and trade missions. Between 2020 and 2022, there were 25 beneficiaries. Potential beneficiaries seeking grants can benefit from RAS, which offers reimbursement of up to 60% of their total submitted project cost. The type of support encompasses consulting for developing target market strategies, facilitating export marketing initiatives, entering and positioning in target markets, improving export capabilities, participating in international fairs and B2B events, and acquiring equipment to bolster production capacities. Potential beneficiaries stay informed about the Export Promotion programme through its website, social media channels, and various relevant export promotion events.

Although direct assistance for environmental initiatives may not be directly provided, applicants are eligible for support in adhering to environmental standards, attestations, or certifications crucial for entering new markets or strengthening positions in existing ones. Notably, potential beneficiaries are not obliged to meet specific environmental criteria to qualify for support under the export promotion programme. The SME Internationalisation Programme encourages individual engagement in international fairs and offers institutional assistance to export-oriented SMEs with the goal of expanding their foreign trade activities. The budget dedicated to the SME Internationalisation Programme remained unchanged at 0.004% of the value of exports since 2019 until 2022, with a brief spike to 0.008% in 2020. The staff allocated to the programme has remained unchanged since 2019, amounting to four employees. Financial support granted through the export promotion programme is monitored with annual reports, audits and impact assessment reports. The two programmes often overlap in terms of the scope of activities and there is no co‑ordination mechanism to ensure the lack of duplication of efforts.

RAS has a strong implementation capacity when it comes to regional development, with 16 accredited regional development agencies10 spread across the economy to ensure equal opportunities for SMEs situated outside the capital. RAS has reinforced its position as the main authority governing export promotion, which has been reflected in its perception among Serbian businesses. In 2022, 6% of surveyed businesses quoted the lack of a competent authority that could provide information on export procedures as one of the export deterrents, the highest percentage in the Western Balkan region. That percentage decreased to 3% in 2023, signalling RAS’s increasing competence in supporting companies in their export endeavours (Balkan Barometer, 2023[17]).

Despite RAS being the best-staffed export promotion agency in the Western Balkans, intensified capacity building and advisory support would be particularly beneficial for Serbia to improve its integration into global value chains (OECD, 2022[18]). 23% of surveyed companies quote lack of export capacity as the main reason for not exporting in 2023, up from 22% in 2022 (Balkan Barometer, 2023[17]). Therefore, allocating additional staff to improve the provision of training and capacity building – particularly focusing on foreign expansion, market access, certification and standardisation – would have more tangible benefits for companies than participation in trade fairs.

Overview of implementation of the Competitiveness Outlook 2021 recommendations

Serbia made considerable progress in implementing Competitiveness Outlook 2021 Recommendations, with the strongest progress observed in expanding the bilateral and multilateral free trade agreements network and strengthening the legal framework for e-commerce. The latter was achieved by implementing an online dispute resolution mechanism for cross-border e-commerce disputes. There has been some progress in improving the quality of public consultation processes; however, the processes are underutilised as many trade-related decisions are still adopted without prior consultations with the public or with little notice.

Table 3.3. Serbia’s progress on past recommendations for trade policy

|

Competitiveness Outlook 2021 recommendations |

Progress status |

Level of progress |

|---|---|---|

|

Enhance the quality of the public consultation process |

The process of public-private consultations has been digitalised by introducing the eConsultations platform. However, little progress has been made in adopting trade rules or restrictions through exceptional and shortened procedures without prior notice. Despite advancements in the digitalisation of public-private consultations, the sudden introduction of certain temporary trade restrictions with minimal notice has disrupted the predictability of the business environment. |

Moderate |

|

Expand the network of bilateral and multilateral FTAs |

Serbia has broadened its scope of free trade agreements (FTAs), witnessing the implementation of numerous agreements in 2021, including one with the Eurasian Economic Union. Notably, the most recent addition to this growing network is the UK-Serbia Partnership, Trade, and Cooperation Agreement, which has been in effect since May 2021. No progress was made in Serbia’s WTO accession. |

Strong |

|

Strengthen the regulatory framework for e-commerce and digitally enabled services |

The implementation of the new Consumer Protection Law established the groundwork for improving the operations of online businesses in Serbia. Furthermore, the 2021 revision to the Law on Electronic Document, Electronic Identification, and Trust Services in Electronic Business introduced standardised provisions related to electronic documents, electronic contracts, electronic identification systems, and qualified trust services. |

Strong |

The way forward for trade policy

While the government has made notable strides in enhancing its trade policy framework, particularly in trade policy formulation and digital trade, there remains room for further improvement in the following policy-making areas:

Prioritise the transition to paperless trade. Serbia’s progress in digitalising procedures and simplifying administrative processes has not yet extended to trade documents. Traders still need to submit notarised copies for various product and service categories. Electronic documentation would improve efficiency, minimise errors, and reduce processing times. Additionally, paperless trade fosters a transparent and traceable supply chain, building trust among partners. Ultimately, this shift positions Serbia for cost savings, increased trade competitiveness, and a more resilient trade environment.

Advance the compliance with WTO rules to finalise the accession process. Serbia should place a high priority on completing its accession to the WTO. Making the necessary internal regulatory alignment and completing the remaining bilateral market access negotiations would allow Serbia to expedite its accession process to strengthen its position in the global trading system.

Incorporate provisions on digital trade in free trade agreements. Including such provisions facilitates the flow of information and digital services and encourages innovation, efficiency, and competitiveness. The prevalent digital trade provisions in RTAs typically cover aspects such as privacy and data protection, consumer protection, unsolicited commercial electronic messages, electronic authentication, paperless trading, cross-border data flow (Box 3.3), and cybersecurity. Moreover, there is an emerging trend of digital economy agreements, which mirror free trade agreements, but they go beyond the usual scope of FTAs to include co-operation on open government, artificial intelligence and other digital economy aspects (IMF et al., 2023[19]).

Box 3.3. Cross-border data flows in trade agreements in OECD countries

Across OECD economies and beyond, provisions on cross-border data flows are increasingly common in free trade agreements. Since 2008, 29 trade agreements involving 72 economies have included clauses related to data flows. However, the comprehensiveness of these provisions varies. Roughly 45% of the agreements have enforceable commitments covering all types of data flows. Additionally, all agreements with data flow provisions include clauses on privacy or consumer protection frameworks, often referring to plurilateral arrangements.

Countries both within the OECD area and beyond employ a range of instruments to facilitate cross‑border data transfers, including unilateral mechanisms, standards, technology-driven mechanisms, plurilateral arrangements, and trade agreements and partnerships.

Examples of such agreements include the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans‑Pacific Partnership and the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement, which feature binding data flow provisions, and free trade agreements between South Korea and Peru, and Central American countries and Mexico, which have non-binding provisions. Moreover, agreements like the EU-Japan and EU-Mexico free trade agreements anticipate the potential re-evaluation of cross-border data flow provisions in the future.

While the number of agreements with binding data flow regulations equals those with non-binding rules, it is worth noting that most recent trade agreements (for example the Japan-United Kingdom Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership) predominantly incorporate binding provisions.

Significant levels of regulatory convergence have been achieved concerning certain objectives and principles, such as promoting e-commerce, minimising barriers, and addressing the requirements of SMEs. Additionally, convergence and commonalities exist on specific topics like transparency, paperless trading, and electronic authentication. However, notable disparities persist, especially concerning handling cross-border data flows, data localisation, and personal data protection.

Sources: Casalini, López González and Nemoto (2021[20]), Burri, Vasquez Callo-Müller and Kugler (2022[14]).

Improve monitoring and evaluation of implemented trade policies and digital trade facilitation measures. By implementing robust monitoring systems, Serbia can closely track the effectiveness and impact of digital trade facilitation initiatives. This involves assessing how well these measures streamline processes, reduce bureaucratic hurdles, and enhance overall trade efficiency. Regular evaluations, supported by quantifiable indicators in action plans, can also help adapt policies to evolving technological landscapes and address challenges promptly, ensuring that digital trade facilitation measures continue to meet the evolving needs of businesses.

Improve training and capacity-building initiatives in export promotion to better position Serbian companies in global value chains. Dedicating more personnel resources to RAS to enhance the delivery of training and capacity-building initiatives – with a specific emphasis on foreign expansion, market access, certification, and standardisation – would likely yield more substantial advantages for companies. By investing in the skill development and knowledge base of the workforce, businesses can gain a competitive edge, navigate regulatory complexities more effectively, and foster sustained growth in international markets.

References

[17] Balkan Barometer (2023), Business Opinion 2023, https://www.rcc.int/balkanbarometer/results/1/business.

[14] Burri, M., M. Vasquez Callo-Müller and K. Kugler (2022), TAPED: Trade Agreement Provisions on Electronic Commerce and Data, https://unilu.ch/taped.

[12] Casalini, F. and J. López González (2019), Trade and Cross-Border Data Flows, https://doi.org/10.1787/b2023a47-en.

[20] Casalini, F., J. López González and T. Nemoto (2021), “Mapping commonalities in regulatory approaches to cross-border data transfers”, OECD Trade Policy Papers, No. 248, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/ca9f974e-en.

[11] Council of Europe (2021), Guidelines of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe on Online Dispute Resolution Mechanisms in Civil and Administrative Court Proceedings, https://search.coe.int/cm/Pages/result_details.aspx?ObjectId=0900001680a2cf97.

[4] European Commission (2023), Serbia 2023 Report, https://neighbourhood-enlargement.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2023-11/SWD_2023_695_Serbia.pdf.

[9] Eurostat (2023), E-commerce Sales of Enterprises by Size Class of Enterprise, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/bookmark/a1b904cc-ae55-4980-bd56-f717cb144507?lang=en (accessed on 12 January 2024).

[5] Government of Serbia (2024), eKonsultacije, https://ekonsultacije.gov.rs/ (accessed on 14 May 2024).

[19] IMF et al. (2023), Digital Trade for Development, https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/booksp_e/dtd2023_e.pdf.

[13] López González, J., S. Sorescu and P. Kaynak (2023), “Of bytes and trade: Quantifying the impact of digitalisation on trade”, OECD Trade Policy Papers, No. 273, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/11889f2a-en.

[8] Ministry of Trade, Tourism, and Telecommunications (2021), The Law on Electronic Document, Electronic Identification and Trusted Services in Electronic Business, https://www.pravno-informacioni-sistem.rs/SlGlasnikPortal/eli/rep/sgrs/skupstina/zakon/2017/94/4/reg.

[1] National Bank of Serbia (2024), Macroeconomic Developments in Serbia, https://www.nbs.rs/export/sites/NBS_site/documents-eng/finansijska-stabilnost/presentation_invest.pdf.

[21] Observatory of Economic Complexity (2021), Economic Complexity Index, https://oec.world/en/rankings/eci/hs6/hs96?tab=ranking.

[15] OECD (2022), OECD Trade Facilitation Indicators, https://www.oecd.org/trade/topics/trade-facilitation/ (accessed on 4 March 2024).

[18] OECD (2022), SME Policy Index: Western Balkans and Turkey, https://doi.org/10.1787/b47d15f0-en.

[10] OECD (2021), Competitiveness in South East Europe 2021: A Policy Outlook, Competitiveness and Private Sector Development, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/dcbc2ea9-en.

[16] OECD (2021), Digital Trade Inventory, https://doi.org/10.1787/9a9821e0-en.

[7] Serbian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2022), Bilateral Cooperation with China, https://www.mfa.gov.rs/en/foreign-policy/bilateral-cooperation/china.

[6] UNECE (2021), Regulatory and Procedural Barriers to Trade in Serbia, https://unece.org/trade/publications/regulatory-and-procedural-barriers-trade-serbia-needs-assessment-ecetrade460.

[2] World Bank (2023), ICT Service Exports (% of Service Exports, BoP) - Serbia, OECD Members, European Union, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.GSR.CCIS.ZS?locations=RS-OE-EU (accessed on 4 March 2024).

[3] WTO (2021), Trade and Climate Change, https://www.wto.org/english/news_e/news21_e/clim_03nov21-4_e.pdf.

Notes

← 1. The Economic Complexity Index is based on trade data and aims to measure the relative knowledge intensity of an economy. A higher score indicates higher economic complexity. Serbia scored 0.74 in 2021, up from 0.65 in 2018, positioning itself in 36th place out of 129 economies assessed and the highest of the Western Balkan economies (Observatory of Economic Complexity, 2021[21]).

← 2. In April 2023, the government made amendments to the Decision on the establishment of the National Coordination Body for Trade Facilitation. The Minister of Foreign and Domestic Trade will now serve as the president, with the Assistant Minister of Finance as the deputy president.

← 3. The result indicator for the harmonisation and mutual recognition of documents on top of other initiatives to facilitate trade, especially in the context of CEFTA's Additional Protocol 5 and the Open Balkan Initiative, is “trade growth in the region”. As such, regional trade growth be attributed to many factors, so explicit causality cannot be proved, making the result indicator vague and hindering further evaluation. Other indicators, while clearly defined, are not quantified, which can impede effective monitoring of target achievement.

← 4. The OECD has developed indicators with the aim of transforming the relationship between trade and the environment into a foundation for practical evaluation. These indicators primarily serve to help policy makers track progress in harmonising trade and environmental policies, as well as to pinpoint potential conflicts of interest. The OECD database on carbon emissions in trade includes data on the amount of carbon emissions from fossil fuel combustion embodied in imports and exports in megatonnes of CO2.

← 5. From RSD 876 188.40 in 2021 to RSD 248 664.86 in 2022.

← 6. The Eurasian Economic Union consists of Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Armenia. It is a project aiming to deepen regional economic integration, with a formal goal to create an EU-like common market.

← 7. Central European Free Trade Agreement, Stabilisation and Association Agreement between European Communities and their Member States and the Republic of Serbia, Free Trade Agreement Between Eurasian Economic Union and its Member States and the Republic of Serbia and the Partnership, Trade and Cooperation Agreement between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the Government of the Republic of Serbia.

← 8. Stabilisation and Association Agreement between European Communities and their Member States and the Republic of Serbia and the Partnership, Trade and Cooperation Agreement between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the Government of the Republic of Serbia.

← 9. The maximum allocated per beneficiary is EUR 85 000.

← 10. Belgrade, Novi Sad, Subotica, Zrenjanin, Pančevo, Ruma, Požarevac, Loznica, Kragujevac, Zaječar, Užice, Kraljevo, Kruševac, Niš, Novi Pazar, Leskovac.