Agricultural development remains a priority for all economies, not only in response to the essential resource needs of a growing population but also due to its substantial contributions to total employment and GDP. The chapter analyses the performance and trends of agriculture policies across three sub-dimensions. The first sub-dimension, rural development and infrastructure, assesses strategies and programs related to rural infrastructure, livelihood support, and irrigation systems. The second sub-dimension, agricultural support systems, covers the policy, governance and instruments in the agricultural sector. The third sub-dimension, food safety and quality, focuses on the policy framework regulating food safety and on the food quality legislation and agencies, which are key tools in an economy’s path towards productive and sustainable agriculture.

Western Balkans Competitiveness Outlook 2024: Serbia

15. Agriculture policy

Abstract

Key findings

Serbia has increased its overall agriculture policy score since the previous Competitiveness Outlook, positioning itself as the regional leader in this dimension (Table 15.1). The economy’s most notable area of progress was in strengthening its rural development and infrastructure due to ongoing efforts to enhance the rural and irrigation infrastructure systems. Serbia has also made strong advances in enhancing its research, innovation, technology transfer, and digitalisation (RITTD) framework.

Table 15.1. Serbia’s scores for agriculture policy

|

Dimension |

Sub-dimension |

2018 score |

2021 score |

2024 score |

2024 WB6 average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Agriculture |

14.1: Rural development and infrastructure |

3.8 |

3.2 |

||

|

14.2: Agriculture support system |

3.7 |

3.3 |

|||

|

14.3: Food safety and quality |

3.5 |

3.4 |

|||

|

Serbia’s overall score |

3.3 |

3.1 |

3.7 |

3.3 |

|

The key findings are:

Despite recent government initiatives to enhance harmonisation between national agricultural policies and the EU acquis, including formulating a new action plan, Serbia’s current policy framework still exhibits significant misalignment, covering only half of the EU Common Agricultural Policy’s (CAP) objectives.

Progress has been achieved in expanding the economy’s irrigation and drainage infrastructure, but it remains inconsistent. However, the Serbian Government’s ongoing efforts – such as developing a new irrigation strategy – along with donor projects aimed at constructing new systems and rehabilitating existing ones underscore the priority allocated to improving this infrastructure.

The introduction of the new platform e-Agrar in 2023 marked a significant step forward in Serbia’s efforts to establish an integrated administrative and control system, although this progress was offset by the lack of headway in procuring the software for a Land Parcel Identification System. Consequently, there is a sustained need for the economy to continue developing its data management platforms.

Although Serbia is set to receive substantial EU funding through the IPARD III programme, totalling an estimated EUR 288 million from 2021 to 2027, delays in payments have hindered the efficient use of these funds. This challenge highlights the importance of strengthening government capacities, particularly those of the national IPARD (Instrument for Pre-Accession Assistance for Rural Development) Agency.

Continuous efforts to strengthen the research, innovation, technology transfer, and digitisation (RITTD) framework, namely through the Competitive Agriculture Project 2021-24 and ongoing co-operation between the BioSense Institute and the EU, have positioned Serbia as the regional leader in this domain.

Although Serbia made some recent improvements to its food quality policy framework, such as a new draft law aligning its policy on genetically modified organisms (GMOs) with EU regulations, the economy’s standards are still only partially aligned with the relevant EU legal bases.

State of play and key developments

Given that Serbia is the largest agricultural market in the Western Balkans, agriculture serves as an important sector of the economy, benefiting from favourable climatic conditions, fertile soil, and a relative abundance of arable land (FAO, 2023[1]). Over the past several years, the contribution of the agricultural sector to national GDP has been steadily rising, reaching EUR 3.80 billion in 2022 in nominal value,1 while agriculture’s share of national GDP has remained constant, hovering around 6.5% (World Bank, 2024[2]). However, there are strong differences from year to year. After experiencing significant growth in 2018 and 2020, there was a notable downturn in the subsequent two years. This decline, ‑5.5% in 2021 and ‑8.3% in 2022, was primarily due to the cumulative impact of external shocks, including the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russian war of aggression against Ukraine, along with adverse weather conditions, namely the recent drought.

Notably, the long-term growth trends of the agricultural sector mirror that of the broader economy, signalling a robust strengthening of the sector. Enhanced efficiency, attributed to increased investments (including foreign direct investment), has been a significant driver of the sector’s positive performance in Serbia (Vojteški and Lukić, 2022[3]) (Vukmirović et al., 2021[4]).

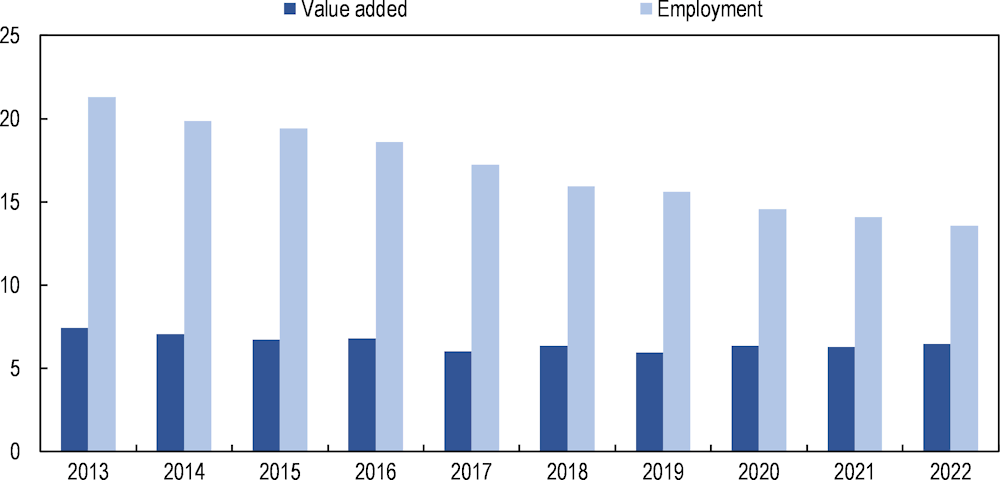

However, while the agricultural sector’s value added to GDP has remained steady, the proportion of total employment within the sector has seen a decline over the past decade, falling from 21.2% in 2011 to 13.9% in 2021. As evidenced in Figure 15.1, the noticeable gap between agriculture’s contributions to GDP and employment indicates that a relatively large portion of the workforce is producing a relatively minor share of overall economic output, signalling lower levels of labour productivity. However, this gap has been narrowing, likely attributed to the sector’s ongoing modernisation, which is supported by Serbia's strategic investments. Additionally, this decrease in the proportion of employment is partially due to demographic shifts, such as the growing trend of migration from rural areas and the ageing workforce (with more than 20% of those engaged in agriculture being 65 years of age or older) (Ćirić et al., 2021[5]).

Figure 15.1. Agriculture’s contribution to gross domestic product and total employment in Serbia (2013-22)

Agriculture’s share in value added and employment are denoted in percentages

Serbia’s agricultural sector is characterised by a high level of farm fragmentation, which can limit productivity gains. According to the 2023 Agriculture Census, 99.6% of registered farms were family farms, and the average agricultural holding was only 6.4 hectares (ha) (Government of the Republic of Serbia, 2024[6]). In comparison, the average mean size of farms in the EU is 17.4 ha, nearly three times that of Serbia (Eurostat, 2023[7]). Yet despite this prevalence of small family farms, there has been a concurrent rise in the establishment of large, modern farms characterised by fewer employees, higher productivity, and strong market orientation – leading to the economy’s current dual farm structure.

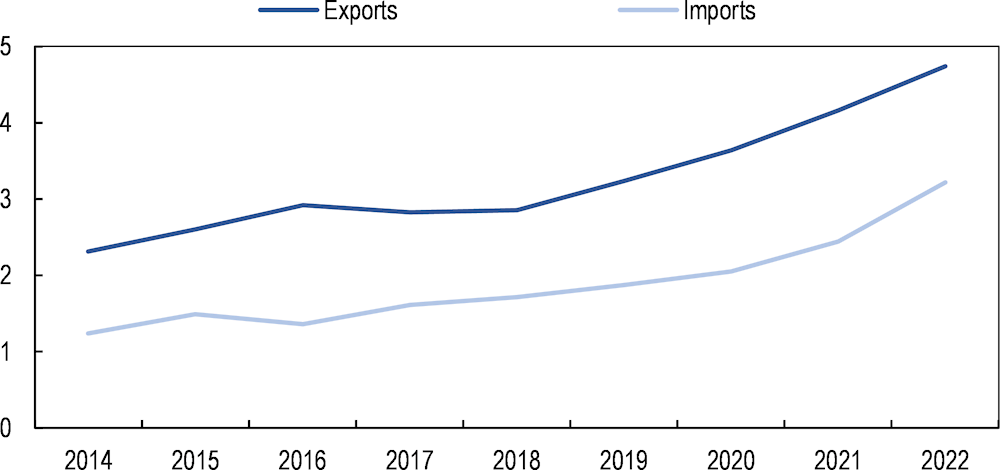

International trade data indicate a strengthening of the Serbian agrifood sector, with exports surpassing EUR 4.7 billion and constituting nearly one-fifth of total exports in 2022 (Figure 15.2). This reflects a notable increase of more than 21% compared to the yearly averages in 2020 and 2021. However, this rise in value is partially attributable to inflation, as the quantity of certain exports actually fell during this period due to the aforementioned drought. Imports grew faster than exports during this period, leading to a modest reduction in the trade balance of agrifood products in 2022. Despite this decline, Serbia maintains a significant trade surplus, distinguishing it from other Western Balkan economies that are characterised by trade deficits in agrifood products. Indeed, the economy remains the largest (and only net) exporter of food products among the Central European Free Trade Agreement (CEFTA) parties (Development Agency of Serbia, 2023[8]).

Figure 15.2. Serbia’s international trade of agrifood products (2014-22)

Billions of EUR

Sub-dimension 14.1: Rural development and infrastructure

Serbia has continued to bolster its rural infrastructure policy framework since the last assessment cycle, primarily through the passage of several new policy measures. In July 2021, the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Water Management (MAFWM) adopted the Regulation on Investment Incentives for the Improvement and Development of Rural Public Infrastructure,2 outlining the various incentives to enhance and develop rural public infrastructure. These incentives target a wide variety of infrastructure, ranging from roads to water supply channels to the processing of agricultural products. Moreover, at the start of 2022, the MAFWM launched public consultations for the draft National Rural Development Programme (2022-24), which defines measures for improving and developing this rural infrastructure. However, the draft national programme remains outstanding, and its complementarity with the EU’s Instrument for Pre-Accession Assistance for Rural Development (IPARD) III programme has yet to be formalised.

The IPARD programme plays a notable role in supporting Serbia’s ongoing efforts to enhance its rural infrastructure. Under IPARD III, there is a specific measure focused on investments in rural public infrastructure to support economic, social and territorial development that will promote sustainable and inclusive growth. Between 2021 and 2027, Serbia is set to receive EUR 288 million in EU funds, of which approximately EUR 51.8 million will be used to finance rural infrastructure projects (European Commission, 2022[10]). Of note, under the IPARD programme, “rural areas” encompass all territory in Serbia with a population density below 150 inhabitants per km2. An estimated 40% of the Serbian population lives in rural areas (Parausic, Kostic and Subic, 2023[11]).

Despite Serbia’s well-developed policy framework, the economy’s rural infrastructure still does not fully address the needs of rural populations. Many rural areas have limited road infrastructure and are frequently far from the main roads and highways (Veličković and Jovanović, 2021[12]). With respect to ICT infrastructure, a significant disparity exists between urban and rural areas: while 85% of households in urban areas are connected to fixed broadband, only 69% of those in rural areas share the same access (EBRD, 2021[13]). However, several new projects aim to address this gap between infrastructure and needs. For example, in the spring of 2022, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) launched the second phase of the Rural Broadband Rollout project, which aims to connect an additional 305 schools and 128 000 households in rural areas to a broadband network.3

There are several online platforms available to farmers that provide regular, up-to-date information on prices and weather conditions. One example is AGROPONUDA,4 a free online service provided by the MAFWM where agricultural producers (who constitute the “register of bidders”) connect with buyers through the “register of offers”. This service is widely used: an average of 25 offers are placed daily, and over the past decade around 14 200 producers have entered offers. Another platform is STIPS or the Serbian Agriculture Marketing Information System Network. This online database provides data on the prices of agricultural and food products and inputs on both a weekly and monthly basis.5 Using price data, reports are generated and included in the weekly newsletter. These reports depict the status of supply and demand, quality assessments, and price trends over the preceding seven days.

Serbia’s approach to rural livelihoods is characterised by a strong policy focus but lacks comprehensive programming. The National Strategy of Agricultural and Rural Development defines the economy’s long-term rural development goals, while the Law on Incentives in Agriculture and Rural Development regulates the policy instruments used to support rural communities. Some of these instruments aim to improve rural livelihoods and developments through measures to strengthen economic development, rural diversification, and agritourism. However, no programmes explicitly target other key components of rural livelihoods, such as education, health or social security protections.

Apart from households and farms, Local Action Groups (LAGs) are key in empowering rural populations and fostering community development. Since 2007, the Serbian Government has been implementing the LEADER approach, although these efforts have primarily been supported through funding from external donors. Moreover, in 2019, the national LEADER measure was adopted; since then, 21 partnerships have received LAG status. Representing a relatively new approach to rural development in Serbia, the ongoing LEADER process involves the capacity building, learning, animation, education, and networking of stakeholders. Existing partnerships (potential LAGs) with approved Local Development Strategies (LDS) established through the implementation of the national "LEADER-like" measure will be acknowledged as LAGs under the IPARD III programme. These LAGs must prepare and adopt the LDS for the IPARD III programming period.

Despite a relatively robust irrigation policy framework, Serbia’s observed progress in expanding its irrigation systems has fluctuated recently. Between 2021 and 2022, the economy increased its total volume of water extracted for irrigation by 7.3% and the area of agricultural land irrigated by 4.6% (Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia, 2023[14]). However, from 2022 to 2023, the amount of irrigated agriculture land dropped by 12.9%, falling from 54 639 ha to 47 579 ha and accounting for less than 2% of total arable land largely attributed to underdeveloped irrigation infrastructure (Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia, 2024[15]). However, efforts are under way with numerous projects aimed at addressing and improving this issue. The irrigation policy framework is formed by several key programmes and strategies. In April 2023, the River Basin Management Plan (RBMP) by 2027 was adopted. RBMP was prepared in accordance with the principles of the EU water-related directives. The RBMP establishes guidelines and measures to achieve good hydrological, chemical, and ecological status for all water resources. Its focus is on sustainable water use to safeguard the environment while ensuring an adequate supply of high-quality water for all essential users, without necessarily restoring water to its original natural state. Other key policies include the longstanding Law on Water and the national irrigation strategy (still being drafted with the support of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). These strategies delineate plans for modernising and expanding the irrigation system, encompassing measures for open canal and gravity irrigation systems, pipeline distribution networks, pressurised systems, and surface irrigation. The two primary actors in charge of irrigation in Serbia are the MAFWM’s Water Directorate and the public water management companies, Srbijavode and Vode Vojvodine.

External donors have played a large role in the ongoing efforts to expand Serbia’s national irrigation system. In December 2021, the EBRD granted the Serbian Government a EUR 15 million loan to build a new irrigation system in the northern region of Vojvodina. Another project commenced in June 2022, when Agence Française de Développement gave the public water management company Srbijavode EUR 250 000 to work with the company Suez Consulting and conduct a feasibility study on how to approach best rehabilitating and extending the current irrigation network.

Sub-dimension 14.2: Agriculture support system

Serbia’s agricultural policy framework is largely guided by the Strategy of Agriculture and Rural Development (SARD) 2014-24, which defines the economy’s strategic long-term goals of agriculture and rural development.6 However, this policy’s ten-year period introduces several challenges. Firstly, the absence of an annual updated action plan accompanying this strategy restricts the adaptability of priorities to evolving or unforeseen developments. Secondly, this timeframe means the strategy does not comply with the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) strategic programme period. However, despite this misalignment, the SARD is aligned with five of the ten EU CAP objectives.7 Achieving a higher degree of alignment is the focus of the national action plan centred on the transposition, implementation and enforcement of the EU acquis in agriculture and rural development. This action plan is currently being revised by the government.

As mentioned previously, Serbia benefits from funding through the IPARD programme. This initiative supports agricultural producers, processors, and rural communities in enhancing their capacities to meet the EU standards in agriculture, the agrifood industry and environmental protection. After successfully executing four measures in the previous IPARD cycle, the relevant government institutions obtained entrustment for implementing the IPARD III programme. However, payment delays in 2022 led to a loss of EUR 12.8 million in IPARD funds. The risk of additional losses persists unless Serbia addresses the staffing shortages in its IPARD Agency and fully implements its EU acquis alignment action plan to absorb these funds better (European Commission, 2023[16]).

Effective agricultural policies are often accompanied by well-developed information platforms, allowing the government (namely the Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia) to track and analyse agricultural data. Serbia has established both a farm register and a Farm Accountancy Data Network (FADN).8 This FADN uses EU FADN methodology to collect data on a sample of agricultural holdings; the sample size has grown from 1 420 farms in 2017 to 1 729 farms in 2022. However, there is still room to further improve the FADN’s sample size and quality of data collected (European Commission, 2023[16]). One recent development was the introduction of the software platform e‑Agrar, which allows farmers to submit subsidy applications and process them online electronically. By March 2023, approximately 187 000 farmers had registered on the platform. However, Serbia has not established a Land Parcel Identification System (LPIS) due to delays in procuring the appropriate software. Until the LPIS is created and made functional, Serbia cannot launch the IPA project to establish an integrated administration and control system (IACS), which would help to facilitate the accuracy, transparency and compliance of subsidy payments.

Given the agriculture sector’s vulnerability to the future adverse impacts of climate change, the economy has already developed specific policies related to climate change mitigation and adaptation in the sector. Serbia committed to an unconditional emissions reduction target of 13.2% compared to 2010 levels, or 33.3% compared to 1990 levels, by 2030 (UNDP, 2022[17]). The government recently completed the drafting of the Low Carbon Development Strategy of the Republic of Serbia and is now in the process of adopting it. Moreover, under the IPARD III programme, one measure (“agri-environment-climate and organic farming”) encourages farmers to protect and enhance the environment of the land that they manage. The four chief priorities are improving cultivation methods, boosting biodiversity and ecosystem services, improving water conservation and quality, and encouraging sustainable input use and optimised soil management. Additionally, the government has carried out an assessment of climate change’s impact on the agriculture sector under the project, “Advancing medium and long-term adaptation planning in the Republic of Serbia”. Yet despite these efforts, there are still no mitigation targets related to agriculture in any major policy documents or strategies.

The Serbian Government offers a wide array of generous producer support instruments, including subsidies, credit support, and funding through the IPARD programme. Subsidies are by far the most common tool used to support farmers and other agricultural producers. Indeed, the 2024 budget included approximately RSD 100 billion (EUR 853 million) in total agricultural subsidies (Reuters, 2023[18]). Annual subsidies for agriculture and rural development follow the Law on Subsidies in Agriculture and Rural Development guidelines. The financial allocation of budgetary funds is governed by the annual Regulation on Subsidy Allocation in Agriculture and Rural Development for a given calendar year. This regulation is subject to adjustments throughout the year, incorporating new measures, replacing existing ones, altering the support level per unit, and reallocating funds among subsidies.

Direct payment to support livestock and plant production is one of the most utilised subsidies. These payments are usually linked to farm size, measured by the number of livestock heads or cultivated land area (in hectares). However, conditioning this support on farm size can have a detrimental impact on sector productivity and efficiency, as it encourages farmers to continue their existing production patterns (World Bank, 2019[19]). Since 2021, there have been several notable changes to direct payments available to farmers. Firstly, the minimum number of heads required for eligibility to receive support was eliminated or reduced for certain kinds of livestock (although a maximum number was also inaugurated). Additionally, in 2023, the level of direct payments per hectare was doubled. Other new subsidies include subsidising fuel in response to rising prices in 2022 and subsidising insurance and support in the aftermath of any catastrophic events affecting rural areas or the agriculture sector.

Serbia’s wide availability of producer support instruments reflects the government’s commitment to supporting the agricultural sector. Many of the changes were in response to external shocks, such as market disruptions stemming from the Russian war of aggression against Ukraine or the occurrence of natural disasters. Considering the significant price fluctuations that impeded the implementation of the IPARD programme, the IPARD Managing Authority introduced tools to enhance project support. Specifically, it developed a price index for specific and justified cost categories to amend the regulations for the IPARD II programme (under which calls for proposals were extended until 2022).

Table 15.2 shows how the yearly support has continued to grow over the past few years. Moreover, this upward trend is also evident when the data are expressed relative to the population and agriculture area. Support reached EUR 100/ha in 2020-21 and has since increased to EUR 107/ha in 2022. However, this figure remains below the regional average (EUR 113/ha) and is only half of the equivalent values in the EU (at least EUR 200/ha in 2023) (European Commission, 2023[20]).

Many of the aforementioned changes were in response to external shocks, such as market disruptions stemming from the Russian war of aggression against Ukraine or the occurrence of natural disasters. In light of the significant price fluctuations that impeded the implementation of the IPARD programme, the IPARD Managing Authority introduced tools to enhance project support. Specifically, it developed a price index for specific and justified cost categories to amend the regulations for the IPARD II programme (under which calls for proposals were extended until 2022).

Table 15.2. Serbia’s budgetary support for the agricultural sector (2019-22)

Millions of EUR

Of note, eligibility for all these producer support instruments is not conditional on compliance with other standards, such as environmental, food safety, or animal and plant health regulations. Thus, while the Serbian Government has adjusted its instruments in recent years to improve harmonisation with the EU CAP, the implementation of conditionality is a prerequisite for fully aligning with EU standards on agriculture and rural development.

Serbia maintains a relatively open trade policy, although this classification is contingent on the removal of tariffs and barriers. Import tariffs apply to all agricultural products, including inputs and agricultural machinery. Sensitive agricultural products incur both ad valorem and specific customs duties; moreover, certain categories of products, such as flowers and fresh fruits and vegetables, are subject to any additional seasonal customs duty (expressed as a percentage rather than as a function of weight). Customs duties vary for imports from third countries and those covered by existing free trade agreements.

Serbia’s trade with the EU, its largest trading partner, is regulated by a Stabilisation and Association Agreement (SAA). Under this agreement, tariff quotas are defined. The model used for these quotas is “first come, first served”, meaning that import opportunities are allocated based on the order of application submissions, with earlier applicants receiving the benefits until the quota is fully utilised. The administration of tariff quotas is carried out by the Customs Administration of the Ministry of Finance, which updates its website with the availability of quotas according to individual agreements and products every morning. Moreover, under the SAA, Serbia implements export quotas exclusively for sugar exports destined for the EU market. The economy has abolished all other export quotas, duties, and subsidies.

However, the Russian war of aggression against Ukraine catalysed the Serbian Government to make several changes to its trade policy. Specifically, it enacted a five-month export ban in 2022 on certain agricultural products, including cereals, wheat, sunflower oil and milk, as a response to market disruptions and increased domestic and international demand. Additionally, in early 2022, the government decided to include certain ammonia-based mineral fertilisers in the Decision on the Exemption of Certain Agricultural Products from Import Customs, to ensure that farmers could procure adequate quantities for their crops.

With respect to the agricultural tax regime, Serbia currently lacks a fiscal policy dedicated to agricultural and rural development. Agricultural holdings are treated the same as other legal entities and subsequently fall under the CIT (corporate income tax) system. Meanwhile individual farmers, who are classified as natural persons, are subject to personal income tax. According to the Decision of the Ministry of Finance of the Republic of Serbia, a natural person earning income from agriculture and holding the status of an entrepreneur is required to maintain financial records. Generally, farmers in Serbia are not obligated to pay value added tax (VAT), even if their total turnover exceeds RSD 8 million (or around EUR 68 270) which is the national taxation threshold for VAT registration in Serbia. Instead, entrance into the VAT system is voluntary, as farmers can opt to pay this tax by submitting a registration application and assuming the two-year minimum payment obligation. However, specific tax provisions for farms or co-operatives, such as tax rebates on land transfers or income smoothing measures, are notably absent. Additionally, despite the existence of a definition for “small farms”, there are no corresponding provisions that would confer special benefits to these small-scale agricultural operations.

Serbia’s robust policies and instruments guiding research, innovation, technology transfer and digitalisation (RITTD) in its agriculture sector have positioned the economy as the regional leader in this domain. The national policy framework guiding RITTD is part of the National Rural Development Programme 2022-24, which has a pillar on the creation and transfer of knowledge and innovation. Moreover, the Law on Incentives in Agriculture and Rural Development defines support for programmes related to the improvement of the system of creation and transfer of knowledge. In addition to these frameworks, there are several government RITTD programmes that are regularly updated and promoted through the Annual Programme for the Development of Advisory Services in Agriculture.

Apart from these broader RITTD programmes, Serbia has established several programmes specifically aiming to promote the adoption of innovations and knowledge transfer by farms and agrifood firms. One such initiative is the Competitive Agriculture Project 2021-24, a collaborative effort between the MAFWM and the World Bank. It seeks to enhance the capacities and entrepreneurial knowledge of small and medium-sized agricultural producers and enterprises. The programme utilises a distinctive financing model known as 50:40:10. Beneficiaries can receive a grant covering 50% of a project’s total investment value and an additional 40% from commercial bank loans, meaning they only must contribute 10% of the funding by themselves. No specific programmes targeting the adoption of innovations related to climate change adaptation exist, although there are various activities – namely undertaken under IPARD III’s Measure 4 (“Agri-environment-climate and organic farming”) – that bolster the agricultural sector’s resilience to changing climatic conditions.

One of the primary actors in the agricultural research and innovation space in Serbia is the Institute for Research and Development of Information Technology in Biosystems, or the BioSense Institute. This public laboratory serves as a leading Digital Innovation Hub (DIH) in the economy and aims to introduce digital solutions across the entire farm-to-fork value chain.9 Since its establishment in 2015, the BioSense Institute has contributed to the digital transformation of the agriculture sector in Serbia through its research and collaboration (Box 15.1).

Another central component of RITTD is the use of extension and advisory services to facilitate the transfer and adoption of innovation in the agriculture sector. In Serbia, extension services and experts are widely available and accessible to farmers. As of January 2024, the Serbian Agriculture Advisory Service (AAS) was composed of 34 agricultural advisory centres, with more than 250 advisors. The AAS collaborates with the Institute for Science Application in Agriculture to develop annual plans for the training of advisors. These services are provided for free by the public sector, as they are funded from the state agricultural budget as well as from the budget of the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina. Moreover, there are three private extension services that receive full funding from the MAFWM for advisory work, as stipulated by the Annual Programme for the Development of Advisory Services in Agriculture. This constellation of public and private services necessitates institutional co-ordination: indeed, while the MAFWM directly handles the provision of public services, the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology oversees the programming of activities and the work done by the MAFWM advisors.

Box 15.1. Serbia’s BioSense Institute’s agricultural innovations

The BioSense Institute is a public research institute in Serbia that both executes and co-ordinates research in several sectors, ranging from environmental health and protection to agriculture and water management. In 2017, the EU-funded ANTARES project was launched to support the Institute’s transition into a European Centre of Excellence for advanced technologies in sustainable agriculture (European Commission, 2023[21]). With a substantial investment of EUR 14 million from the European Commission, complemented by an additional EUR 20 million from the European Investment Bank, ANTARES represents the largest research initiative ever funded by the EU in Serbia.

The project’s overarching objective is to revolutionise Serbia’s agricultural sector through digital innovation, positioning the economy as a leader in shaping the future of sustainable farming practices while also ensuring safe, ample food for future generations. In pursuit of this goal, the BioSense Institute has already developed several innovations that have empowered local farmers with data-driven insights. Examples of these tools include:

Agrosense: a digital platform that gives farmers access to data on weather, satellite imagery of crops, and the availability of water and nutrients.

Plant-O-Meter: a device that uses artificial intelligence algorithms to assess the physiological condition of plants, such as their capacity for photosynthesis or the need for fertiliser. The assessment generated by the device is shared via Bluetooth with the farmer’s smartphone along with the GPS location of the sample.

Lala: a robot that samples and analyses soil to help improve farmers’ decision making regarding sowing, water, or applying fertilisers and pesticides to their crops.

As the ANTARES project approaches its conclusion in 2025, it stands as a strong example of successful EU collaboration, driving transformative change in Serbia’s agricultural sector and setting an important precedent for agricultural research and innovation partnerships.

Sources: European Commission (2023[21]); Kovacevic (2023[22]).

Sub-dimension 14.3: Food safety and quality

Although Serbia’s national policy framework covers all main areas of food safety, animal health, and plant health, it is still not entirely aligned with the EU acquis. This legal base is partially harmonised with the EU food safety legal base. In 2023, Serbia presented a draft strategy and action plan to further align its national legislation on food safety with the EU acquis, although they have not yet been adopted. Regulations related to animal health and welfare are almost fully aligned with those of the EU, although measures on several animal diseases must be harmonised in the future to comply with the most recent EU acquis. In the phytosanitary field, policies are generally compliant with World Trade Organisation (WTO) legislation, although the economy still lacks a legal framework guiding the sustainable use of pesticides.

The government agencies responsible for these policy areas include the MAFWM’s Veterinary Directorate, Plant Protection Directorate and Sector for Agriculture Inspection as well as the Ministry of Health’s Sector for Sanitary Inspection. The competencies and responsibilities of these several institutions are clearly delineated and defined in Article 12 of the Law on Food Safety. Moreover, institutional coordination in relation to policy design and implementation is achieved through ad hoc working groups and interministerial committees. However, human resource limitations – particularly regarding the longstanding vacancies in the Veterinary Directorate – stemming from slow hiring processes and non‑competitive salaries complicate these agencies’ ability to properly implement their mandates.

Risk assessment and risk management frameworks are in line with SPS (sanitary and phytosanitary) rules and use internationally established methodologies (such as OIE, IPPC, Codex and EFSA10). For risk analysis related to food safety, inspection is based on several factors, including the type of food, its production criteria, previous reports on safety, and the reliability of the food business operator. This risk‑based assessment might also look at the concentration of pesticides or other contaminants in the food. Maximum residue levels (MRLs) are defined within national bylaws (such as ministerial orders) in line with the EU acquis.11

Laboratories specialising in food safety, veterinary services, and phytosanitary measures are pivotal in safeguarding the well-being and safety of agricultural and animal products. In Serbia, there is an established and accredited reference laboratory. The results of these laboratories are partially recognised among CEFTA parties in the area of food safety and phytosanitary health, although most of the laboratory tests conducted for official controls are limited to the latter. However, challenges persist in milk testing quality, as Serbia has yet to adopt a strategy aligning with EU acquis standards. Due to insufficient funding and resources, including specialist staff and analytical scope in its laboratories, the Directorate for National Reference Laboratories (DNRL) has yet to perform the required milk testing analysis (European Commission, 2023[16]).

As for food quality, while Serbia’s national policies are relatively comprehensive, they still are only partially aligned with the relevant EU legal bases. Since the last assessment cycle, the economy has made some progress in further harmonising legislation on food marketing standards. For instance, in June 2021, the Law on Organisation of Agricultural Products Market (Official Gazette of RS, No. 67/21) was adopted. This law achieved partial harmonisation with the EU regulation on establishing a common market organisation (CMO) for agricultural products, with full harmonisation to be achieved by the date of Serbia’s accession to the EU. While most marketing standards, aligned with EU regulations, are already integrated into quality regulations for products such as milk, meat, eggs, and fish, the pending enactment of the CMO legislation would primarily serve as a stamp of approval, marking a transition with a certain dynamism into regulations on market standards.

Moreover, Serbia’s legislation on geographical indications (GIs), the Law on Geographical Indications, is only partially harmonised with EU standards due to gaps in terms of necessary procedures and controls. One notable difference is that in Serbia, any domestic individual or legal entity producing a product in a specific geographical area can apply to establish a GI; in the EU, that ability is limited to associations of producers and processors of agricultural or food products. Despite this, the economy encounters ongoing delays in amending its legislation on quality schemes for agricultural products, which could address and resolve inconsistencies with European legislation, including issues related to the eligibility of applicants.

The Intellectual Property Office (IPO) and the MAFWM are jointly responsible for the implementation of the Law on Geographical Indications. The IPO initiates the registration process for GIs of agricultural products and foodstuffs and maintains the National Register of Protected Designations of Origin (PDO) and Protected Geographical Indication (PGI); the MAFWM primarily oversees implementation. There are special procedures in place for the protection of GIs for wine and soft drinks.

With respect to organic food, limited progress was achieved, as Serbia has yet to harmonise its legislation concerning organic production with the EU acquis. Given the significant recent increase in both the production and export of organic products, aligning with EU regulations stands as a pressing need, making the adoption of a new law fully compliant with EU standards a top priority. Meanwhile, the MAFWM is tasked with authorising organic certification bodies; in 2023, it granted this authorisation to six bodies. Among these, three are local certification bodies, and two are included on the list of recognised control bodies and control authorities for equivalence purposes, meaning they have met the standards outlined by the regulation SRPS EN ISO/IEC 17065.12 It is important to note that despite Serbia’s minimal participation in global organic production and trade – with only 1% of its farms growing organic products – the economy is positioned to become one of the regional leaders in this area based on the growth rate. The sustained expansion of organic production in Serbia could confer numerous advantages, including generating employment in rural regions, safeguarding public health, reducing rural-to-urban migration, and bolstering the agricultural sector’s competitiveness (Radović and Jeločnik, 2021[23]).

Similarly, Serbia still has not aligned its legislation on genetically modified organisms (GMOs) with the EU acquis or WTO standards (European Commission, 2023[16]). However, there is a newly drafted law aiming to bring Serbia’s national policy on GMOs in line with EU regulations, although its adoption is pending.

Overview of implementation of Competitiveness Outlook 2021 recommendations

Serbia’s efforts to implement Competitiveness Outlook 2021 Recommendations have been steady, as it has made moderate progress in most of the priority areas, including investments in irrigation infrastructure and improving food safety policies. Less progress was achieved in the area of enhancing its agriculture land management policy. Table 15.3 shows the economy’s progress in implementing past recommendations for agriculture policy.

Table 15.3. Serbia’s progress on past recommendations on agriculture policy

|

Competitiveness Outlook 2021 recommendations |

Progress status |

Level of progress |

|---|---|---|

|

Continue investment in irrigation infrastructure |

There has been improvement in irrigation and drainage, but there is still significant scope to further advance this area. In 2021, Serbia adopted an action plan for implementing its water management strategy, with annual implementation reports publicly released. |

Moderate |

|

Enhance the agriculture land management policy |

Serbia has made progress toward the establishment of the integrated administration and control system (IACS), but there should be a shift from manual to electronic processing of subsidy applications. The delays with the procurement of software for the land parcel identification system (LPIS) have been a problem that should be addressed. |

Limited |

|

Adopt a law on the common market organisation through secondary legislation in areas including marketing standards, public and private storage, and producer organisations |

There has been progress related to CMOs. The implementation of legislation in the areas of marketing standards, public and private storage, and producer organisations is still pending. Moreover, there are regulations on producer organisations and the food in schools. More specifically, recent legislation now regulates marketing standards for fresh fruits and vegetables. A new law on wine has been prepared and should be adopted. |

Moderate |

|

Improve the performance of the Directorate for Agrarian Payments |

There has been limited progress in the upgrading of IPARD-related agencies’ capacities in terms of recruitment to the IPARD structures and the efficiency of processing IPARD applications and payment requests. Serbia was entrusted with budget implementation tasks for four measures under IPARD II. However, delays in payments in 2022 resulted in a loss of EUR 12.8 million of IPARD funds, and the risk of further losses is imminent. |

Moderate |

|

Improve food safety policies |

Regarding food safety, a strategy and an action plan for alignment with the EU acquis have been drafted and should shortly be adopted. On the other hand, several policy frameworks have yet to be aligned with the EU acquis, particularly in the areas of animal health and welfare. Additionally, the Veterinary Directorate continues to struggle with a staff shortage of official veterinarians in both its inspection and policy departments, impeding the Directorate’s efficacy. |

Moderate |

The way forward for agriculture policy

Considering the level of the previous recommendations’ implementation, there are still areas in which Serbia could strengthen its rural development and infrastructure or its agriculture support system, or further enhance its food safety and quality policies. As such, policy makers may wish to:

Strengthen the institutional capacity to ensure the efficient use of IPARD III funds. Given the significant loss of IPARD funds due to delays in payment, it is imperative for the Serbian Government to ensure that similar issues do not arise in the disbursement of IPARD III funds. One key step is to address longstanding recruitment challenges by filling vacant positions within the national IPARD Agency, enhancing the organisation’s ability to absorb funds more effectively.

Continue to allocate national funding to support the expansion and modernisation of irrigation and drainage systems. While Serbia receives significant funding from donors such as the EBRD and FAO, there is a persistent need to improve this infrastructure further. As such, boosting public investment to strengthen these systems would likely enhance agricultural productivity and promote the sustainable, effective management of water resources.

Sustain efforts to harmonise national legislation with EU standards. Policy makers in Serbia should prioritise increasing alignment between the national agricultural policy and the EU CAP, specifically by incorporating the five excluded EU CAP objectives13 into the existing framework. Moreover, in the fields of food safety and food quality, the Serbian Government should continue adopting measures that will further harmonise regulations with the EU acquis.

Incorporate conditionality into the provision of producer support instruments. Linking eligibility for support to compliance with environmental or food safety standards could enhance agricultural outcomes and align with the new EU CAP 2023-27 (Box 15.2). To achieve this, Serbia could establish explicit guidelines defining the standards for farmers to qualify for financial support, accompanied by training and support services to facilitate understanding and ensure proper implementation.

Box 15.2. Enhanced conditionality under the EU Common Agricultural Policy 2023-27

The EU’s Common Agricultural Policy for 2023-27 introduces substantial reforms to foster sustainability and equality within the agriculture sector. A noteworthy aspect of these reforms is enhanced conditionality, which refers to linking payments through the IPARD III programme to more stringent requirements of beneficiaries to promote environment- and climate-friendly farming practices. Examples of such conditionality measures include requiring farmers to devote at least 3% of their arable land to biodiversity or non-productive elements, or encouraging farms to protect wetlands and peatlands. Support is further increased when directed toward vulnerable sectors, disadvantaged areas, or specific demographics (such as young farmers).

Furthermore, this is the first CAP programming period to include social conditionality, meaning that payments are linked to demonstrated adherence to specific EU labour standards. This innovative approach aims to incentivise farms to enhance working conditions, necessitating compliance with minimum standards to qualify for full CAP subsidies. Failure to do so can, in fact, result in reduced (or even withdrawn) support.

Under the new programme, an estimated 90% of EU farmland is anticipated to be subject to conditionality. Moreover, approximately 50% of income support provided through CAP 2023-27 will be contingent on conditionality of environmental or climate considerations, underscoring the EU’s commitment to advancing sustainable agricultural practices.

Sources: European Commission (2022[24]); EU Monitor (2023[25]).

Continue developing agriculture information systems. Well-developed agricultural information systems are essential for evidence-based policy making and impact monitoring, aligning with EU best practices. As such, the Serbian government should prioritise acquiring the required software to establish an LPIS. A fully operational LPIS would complement existing platforms, namely the farm register and FADN, facilitating comprehensive data collection and analysis.

References

[5] Ćirić, M. et al. (2021), “Analyses of the attitudes of agricultural holdings on the development of agritourism and the impacts on the economy, society and environment of Serbia”, Sustainability, Vol. 13/24, https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/13/24/13729.

[8] Development Agency of Serbia (2023), Invest in Serbia Agri-Food, https://ras.gov.rs/uploads/2023/12/agrifood-2023-small.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2024).

[13] EBRD (2021), EBRD and WBIF Support Serbia to Expand Broadband to Rural Areas, https://www.ebrd.com/news/2021/ebrd-and-wbif-support-serbia-to-expand-broadband-to-rural-areas-.html (accessed on 23 January 2024).

[25] EU Monitor (2023), Explanatory Memorandum to COM(2023)707 - Summary of CAP Strategic Plans for 2023-2027: Joint effort and collective ambition, https://www.eumonitor.eu/9353000/1/j4nvhdfdk3hydzq_j9vvik7m1c3gyxp/vm8fi1trmdtx (accessed on 13 February 2024).

[21] European Commission (2023), Centre of Excellence for Advanced Technologies in Sustainable Agriculture and Food Security, https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/739570 (accessed on 14 February 2024).

[20] European Commission (2023), Income Support Explained, https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu/common-agricultural-policy/income-support/income-support-explained_en#:~:text=Payments%20are%20at%20least%20EUR,EUR%20215%2Fha%20in%202027 (accessed on 24 January 2024).

[16] European Commission (2023), Serbia Report 2023, https://neighbourhood-enlargement.ec.europa.eu/serbia-report-2023_en (accessed on 23 January 2024).

[24] European Commission (2022), Common Agricultural Policy for 2023-2027: 28 CAP Strategic Plans at a Glance, https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu/document/download/a435881e-d02b-4b98-b718-104b5a30d1cf_en?filename=csp-at-a-glance-eu-countries_en.pdf (accessed on 13 February 2024).

[10] European Commission (2022), IPARD III Programme 2021-2027 of Republic of Serbia, https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2023-03/ipard-III-programme-serbia-2021-27_en_0.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2024).

[7] Eurostat (2023), Farms and Farmland in the European Union - Statistics, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/SEPDF/cache/73319.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2024).

[1] FAO (2023), “FAO and Serbia commit to building sustainable agrifood systems”, https://www.fao.org/europe/news/detail/fao-and-serbia-commit-to-build-sustainable-agrifood-systems/en#:~:text=In%20Serbia%2C%20the%20agriculture%2C%20forestry,suitable%20conditions%20for%20agricultural%20production. (accessed on 15 February 2024).

[6] Government of the Republic of Serbia (2024), Agriculture: Get to Know Serbia, https://www.srbija.gov.rs/tekst/en/130157/agriculture.php#:~:text=The%20first%20results%20of%20the,farms%20engaged%20in%20agricultural%20production.&text=The%20total%20used%20land%20area%20is%203%2C257%2C100%20hectares. (accessed on 15 February 2024).

[22] Kovacevic, G. (2023), Digital food security from Serbia, European Investment Bank, https://www.eib.org/en/stories/biosense-novi-sad-innovation-agriculture-food-security (accessed on 14 February 2024).

[11] Parausic, V., Z. Kostic and J. Subic (2023), “Local development initiatives in Serbia’s rural communities as prerequisite for the LEADER implementation: agricultural advisors’ perceptions”, Economics of Agriculture, Vol. 70/1, pp. 117-130, https://doi.org/10.59267/ekoPolj2301117P.

[23] Radović, G. and M. Jeločnik (2021), “Improving Food Security Through Organic Agriculture: Evidence from Serbia”, Shifting Patterns of Agricultural Trade: The Protectionism Outbreak and Food Security, pp. 335-371, https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-16-3260-0_14.

[18] Reuters (2023), “Serbia’s farmers block roads to demand higher subsidies, cheaper fuel”, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/serbias-farmers-block-roads-demand-higher-subsidies-cheaper-fuel-2023-11-20/ (accessed on 24 January 2024).

[15] Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia (2024), Irrigation, 2023, https://www.stat.gov.rs/en-us/vesti/20240110-navodnjavanje-2023/ (accessed on 24 January 2024).

[14] Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia (2023), Irrigation, 2022, https://www.stat.gov.rs/en-US/vesti/20230111-navodnjavanje-2022/?s=2501 (accessed on 24 January 2024).

[9] SWG (2023), Draft technical report on agriculture and rural development polices in Western Balkans.

[17] UNDP (2022), Revised Nationally determined Contribution (NDC) of the Republic of Serbia for the 2021-2030 period, https://climatepromise.undp.org/what-we-do/where-we-work/serbia.

[12] Veličković, J. and S. Jovanović (2021), “Problems and possible directions of the sustainable rural development of Republic of Serbia”, Economics of Sustainable Development, Vol. 5/1, pp. 33-46, https://scindeks-clanci.ceon.rs/data/pdf/2560-421X/2021/2560-421X2101033V.pdf (accessed on 23 January 2024).

[3] Vojteški, K. and R. Lukić (2022), “Efficiency analysis of agriculture in Serbia based on the CODAS method”, International Review 1-2, pp. 32-41, https://doi.org/10.5937/intrev2202039V.

[4] Vukmirović, V. et al. (2021), “Foreign direct investments’ impact on economic growth in Serbia”, Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies, Vol. 23/1, pp. 122-143, https://doi.org/10.1080/19448953.2020.1818028.

[2] World Bank (2024), World Development Indicators, DataBank, https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed on 6 February 2023).

[19] World Bank (2019), Serbia: Competitive Agriculture Project (SCAP), https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/961711573843471628/pdf/Serbia-Competitive-Agriculture-Project.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2024).

Notes

← 1. While the text refers to GDP in euros, it is important to note that the data used to calculate these figures were denominated in USD. The original data indicated a rise from USD 3.07 billion in 2019 to USD 4.11 billion in 2022. See World Bank (2024[2]).

← 3. For more on the “Serbia, Rural Broadband Rollout Phase 2” project, see: https://wbif.eu/investmentgrants//WB-IG06E-SRB-DII-01.

← 4. To access the AGROPONUDA platform, see: www.agroponuda.com/ponuda.

← 5. To access the STIPS platform, see: www.stips.minpolj.gov.rs.

← 6. The Strategy of Agriculture and Rural Development (SARD) had five main objectives: the growth and stability of producers’ incomes; increasing competitiveness while adapting to the demands of domestic and foreign markets and the technical and technological progress of the agricultural sector; sustainable resource management and environmental protection; the improvement of the quality of life in rural areas and poverty reduction; and the effective management of public policies and improvement of the institutional framework for the development of agriculture and rural areas.

← 7. These five objectives are as follows: ensuring a fair income for farmers; increasing competitiveness; environmental care; vibrant rural areas; and fostering knowledge and innovation.

← 8. The Farm Accountancy Data Network (FADN) monitors farms' income and business activities (including production costs, yields, etc.) based on farm surveys. In the EU, it serves as an important source for understanding the impact of the measures taken under the EU CAP.

← 9. The BioSense Institute’s website can be accessed here: https://biosens.rs/en.

← 10. The OIE methodology is from the World Organisation for Animal Health. The IPPC methodology comes from the International Plant Protection Convention. The Codex Alimentarius Commission methodology was jointly developed by FAO and the World Health Organization. Finally, the EFSA methodology was created by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), which provides independent scientific advice on food-related risks.

← 11. Regulation No. 396/2005.

← 12. To access this regulation, see: https://iss.rs/en/project/show/iss:proj:53254.

← 13. These five objectives are: improving the position of farmers in the food chain, climate change action, preserving landscapes and biodiversity, supporting generational renewal, and protecting food and health quality.