Digital transformation, driving efficiency and productivity through the adoption of digital technologies and data utilisation, holds promise for fostering economic activity and competitiveness. This chapter assesses the scope and quality of the policy framework and strategies, as well as the implementation and adoption by Serbia. The first sub‑dimension, access, explores government policies and initiatives to enable network infrastructure investment and broadband services take-up and to increase data accessibility. The second sub-dimension, use, review the government’s plan to implement programmes to develop a user-centric digital government and help businesses achieve a digital transformation. The third sub-dimension, society, assesses whether governments have planned and implemented programmes to reduce the digital divide and create an inclusive society through green digital technologies. The fourth sub-dimension, trust, examines the economies’ frameworks and how they are being implemented to protect data and privacy, build trust in e‑commerce, and ensure cybersecurity through effective digital risk management systems.

Western Balkans Competitiveness Outlook 2024: Serbia

11. Digital society

Abstract

Key findings

Serbia has slightly improved its performance in the digital society policy dimension since the last assessment (OECD, 2021[1]).1 The country has made strides in data accessibility, digital government, privacy and data protection, and cybersecurity. Its performance particularly stands out in the newly assessed field of emerging digital technologies. However, there has been a decline in its performance in digital inclusion. Serbia’s overall performance indicates that the economy is a Western Balkans regional leader in the digital society policy dimension (Table 11.1).

Table 11.1. Serbia’s scores for digital society

|

Dimension |

Sub-dimension |

2018 score |

2021 score |

2024 score |

2024 WB6 average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Digital society |

10.1: Access |

3.5 |

2.9 |

||

|

10.2: Use |

3.5 |

2.3 |

|||

|

10.3: Society |

1.8 |

1.7 |

|||

|

10.4: Trust |

3.5 |

2.7 |

|||

|

Serbia’s overall score |

2.4 |

3.0 |

3.2 |

2.5 |

|

The key findings are:

The enactment of the new Electronic Communications Law in 2023 is a major milestone toward establishing a gigabit society in Serbia. While the law aligns with the European Electronic Communications Code, essential reforms are still pending to foster an investment-friendly environment, minimise risk, and reduce the regulatory and administrative burden of deploying high-capacity networks.

The successful implementation of the e-government programme has boosted the digitalisation of public administration and the delivery of e-services. Data openness is reinforced, and opportunities for the public and private sectors to share and reuse a wide range of datasets are readily available. An eager ecosystem of stakeholders strongly supports data-driven innovation.

Serbia stands out as a regional leader in establishing a policy framework to ensure reliable and responsible use of emerging digital technologies, such as artificial intelligence (AI), harnessing their potential benefits for the greater good. Effective policy implementation has led to the establishment of the Research and Development Institute for Artificial Intelligence in 2021, which serves as an incubator for start-up companies specialising in AI and promotes cooperation between the public and private sectors in this field.

The new Law on Consumer Protection enacted in late 2021, along with subsequent regulations for distance contracts, enhances the protection of online consumers in Serbia and provides opportunities for them to exercise their rights, including out-of-court resolution of disputes. However, awareness-raising initiatives for online consumer protection and the capacity building of employees in both the public and private sectors remain insufficient.

The new cybersecurity strategy aims to foster legal alignment with the EU acquis, increase protective measures for critical information infrastructure, strengthen capacity-building initiatives in the public and private sectors, and promote public-private partnerships. Nevertheless, further reforms are still pending to complete the legal and regulatory alignment with the EU framework.

1. Decreased scores in the Use and Society sub-dimensions in the current assessment (CO 2024), compared with scores in the CO 2021 assessment, are mainly attributed to the incorporation of two new, forward-looking qualitative indicators in the current digital society assessment framework. Scores for these new indicators, namely emerging digital technologies and green digital technologies, are relatively low since they are still in the early stages of development in the Western Balkan region. Furthermore, the scores from the CO 2018 assessment are not directly comparable with current scores due to a significant restructuring of the digital society assessment framework.

State of play and key developments

Serbia leads the way in digital society policies within the Western Balkan region, with its information and communication technology (ICT) sector accounting for a robust 5.1% of the national GDP in 2021 (Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia, 2024[2]). As the largest net exporter industry in the economy, the ICT sector employed over 95 000 individuals and witnessed a remarkable 45% year-on-year increase, exporting nearly EUR 2.7 billion in ICT services in 2022 (European Commission, 2023[3]) .The sector’s growth trajectory persisted in 2023, with projected ICT exports exceeding EUR 3.6 billion (RS, 2023[4]). In fact, the ICT sector has outpaced agriculture in its contribution to the nation's GDP for the first time. By the end of 2023, Russian nationals registered some 9 000 new businesses, operating mostly in the IT sector, which contributed to the ICT’s sector and exports’ growth. However, this remarkable growth can also be partially attributed to Serbia's performance in the artificial intelligence (AI) and biotechnology domains.

The economy has invested in expanding its high-speed optical backhaul network, bringing fibre broadband to 26.44% of all broadband connections in 2022. The government remains committed to digitalising public administration to drive innovation, competitiveness and growth.

However, despite efforts to increase the share of individuals with basic or above-basic digital skills in Serbia, there has been a concerning decline, from 41.3% in 2021 to 33.76% in 2023. This contrasts with the EU average, which increased from 53.92% in 2021 to 55.35% in 2023 (Eurostat, 2024[5]). These statistics highlight a notable disparity in digital skills development and emphasise the pressing need to reassess current policies and implement robust initiatives to enhance digital literacy.

Sub-dimension 10.1: Access

Serbia has made substantial progress in enhancing its broadband infrastructure since 2021, notably extending fibre network access to rural and remote areas. According to Serbia’s telecoms regulator, more than 70% of fixed broadband Internet subscribers use connections faster than 30 Mbps (megabits per second), with over 50% exceeding 100 Mbps (RATEL, 2023[6]). The Statistical Office reports an increase in broadband connections for households in rural settlements, rising from 74.5% in 2021 to 79.8% in 2023. The government remains committed to the vision outlined in the Next Generation Networks Strategy, concluded in 2023, while currently preparing the new broadband policy framework towards a Gigabit Society by 2030. The Ministry of Information and Telecommunications (MIT) launched the EU and EBRD co-funded the Rural Broadband Rollout (RBB) project in December 2022.1 The project aims to construct fibre networks to provide high-speed broadband access to 706 rural settlements by the end of 2025. This infrastructure will connect 728 schools and public buildings with ultra-fast broadband speeds above 1 Gbps (gigabit per second), while over 118 000 households will gain access to 50 Mps connectivity that will gradually upgrade to at least 100 Mps by 2025. The project draws from private sector investments alongside mid-mile investments made by the government for the development of last-mile network connectivity. In early 2024, 161 rural settlements are already connected with high-speed Internet, reaching around 25 000 households, and nearly 70 000 inhabitants (RS, 2024[7]). Legislation on state aid rules for developing broadband infrastructure is not yet aligned with the revised EC Guidelines enforced in 2023,2 meaning that the project is currently developed on the pre-existing EC Guidelines from 2013.3 The revised guidelines adjust the threshold for public support to fixed networks according to the latest technological and market developments, introduce a new assessment framework for deploying 5G mobile networks, and simplify rules to incentivise the adoption of broadband services.

Despite positive developments in broadband access, challenges persist. Issues that slow down or even discourage further broadband network investments include restricted access for users and operators to infrastructure like optical fibres, ducts, public operators’ infrastructure, and dark fibres, alongside lingering constraints imposed by environmental and municipal planning legislation. Although a working group has identified and recommended measures to remove these obstacles, joint decisions among relevant institutions for their implementation are still pending. Furthermore, the draft Law on Broadband Development and subsequent regulations are not anticipated for adoption before the second quarter of 2024. These aim to align with the EU Broadband Cost Reduction Directive,4 effectively reducing costs and regulatory and administrative burdens for network infrastructure investors.

Serbia continues on the path of aligning its electronic communications regulatory framework with the EU acquis, and the recent enactment of the new Law on Electronic Communications in May 2023 marks a positive step toward compliance with the European Electronic Communications Code (European Commission, 2023[3]). The new Law encourages broader Internet connectivity and incentivises private sector investments, outlining mandatory obligations for broadband network operators and refining the approach to radio frequency spectrum and numbering for developing new services, fostering competitiveness. However, the regulatory reform remains incomplete without adopting the necessary accompanying regulations. The Regulatory Authority for Electronic Communications and Postal Services (RATEL) has yet to align voice termination rates across fixed/wireless networks with the EU’s Delegated Regulation5 and to update the analysis of product and service markets within the electronic communications sector in line with the updated EC Recommendation6 on relevant markets. The Law also reinforces the role of RATEL and aims to ensure its financial and operational independence, an aspect that remains subject to recurring scrutiny (European Commission, 2023[3]). RATEL is well staffed with 150 employees at the end of 2023, but staff retention faces challenges due to the imposed salary cap for RATEL personnel.

Despite adopting the new Law on Electronic Communications, the development of 5G has suffered significant delays. Regulations for simplifying and accelerating 5G network installations, including specifications for small-area wireless access points (small antennas), are yet to be prepared. The Ministry is drafting the rulebook on minimal conditions for issuing individual permits for spectrum use, thereby holding back the public bidding procedure for the 5G radio frequency spectrum for 2024.

Serbia has made notable advancements in developing data accessibility in the past three years, primarily driven by data openness objectives in the e-Government Development Programme 2021-25 and supported by measures outlined in the Strategy for Public Administration Reform 2030 and the Artificial Intelligence Strategy 2020-25. While the existing legal framework enables data sharing and reuse through legislation on e-Government and e-Documents, and secondary regulations that delineate the format of published datasets, data governance, and the operation of the national open data portal, it is not fully aligned with the EU Open Data Directive7 or the EU Data Governance Act.8 This alignment will introduce rules for government-held data marketplaces, delineate the reuse of high-value datasets, boost the development of trustworthy data-sharing systems and facilitate the use of public sector data that cannot be made available as open data, such as health data. Efforts are under way to analyse and amend the Law on e-Government in line with EU legislation, encompassing the definition of high-value datasets, governance and accessibility. Serbia is the first Western Balkan (WB) economy to establish a geospatial data-space, GeoSrbija,9 curated by the Republic Geodetic Authority of Serbia, promoting the sharing and reuse of relevant data.

Serbia has developed its national open data portal10 into the most advanced platform of its kind in the WB region. As of early 2024, it offers more than 2 400 open datasets across various thematic topics, a significant increase from the 1 643 datasets available in 2021. The portal presents 42 use-case examples, demonstrating the practical application of open data reuse and stimulating interest in data innovation. Developers can access open datasets published in machine-readable formats through an application programming interface (API) that facilitates the development of innovative services. The Office for IT and e-Government (ITE) operates the portal and offers direct support to data publishers, including an API Guide to support holders of real-time or dynamic data. It further supports data‑ecosystem participants from the public and private sectors through the Open Data Hub11 (ODH). The ODH is a platform offering training on the open data portal, educational activities on data reuse, and various events and meet-ups (hackathons, datathons, Open Data Week) organised in the past three years. Serbia’s progress in developing data openness and accessibility is evident in the 2023 Open Data maturity report (Page et al., 2023[8]), where Serbia ranks 25th among 35 countries with a 75% overall score across the four dimensions of open data maturity assessed.12 Although slightly below the EU average score of 79%, Serbia has significantly improved its score since 2022. This improvement primarily refers to the portal and quality dimensions and stems directly from the creation of guidelines, active assistance to data providers in publishing high-quality metadata, a higher number of automatically sourced datasets, and the availability of more datasets with open licences in a structured format.

Sub-dimension 10.2: Use

Serbia stands at the forefront of digital government development in the WB region, maintaining a strong performance in digitalising public administration and services over the past three years. The European Commission’s 2023 eGovernment benchmark report, monitoring Europe’s progress in digitalising public services (Capgemini, Sogeti, IDC and Politecnico di Milano, 2023[9]) reveals that Serbia made significant progress in digitalising public services compared to 2022. Serbia is approaching the EU average in user centricity, transparency and key enablers such as eID, e-Documents, pre-filled forms and digital post, although it still lags behind in developing cross-border services. Additionally, Serbia reported the highest percentage of individuals that used the Internet to interact with public authorities (51.1%), compared to WB economies and the EU average (50.65%) in 2022 (Eurostat, 2024[10]). These positive results in digital government development were underpinned by the Strategy for Public Administration Reform (PAR) 2021-30 and the Programme for Simplifying Administrative Procedures and Regulations "e-PAPER". Moreover, they are currently boosted by the e-Government Development Programme with its 2023-25 action plan. Implementing these policies, driven by the pandemic, the ITE Office was mandated to prioritise and accelerate the introduction of citizen-centric digital services. Those services are well grounded on a legal framework that aligns with the EU acquis, comprising the Law on e‑Government and complementary regulations. The national eID scheme aligns with the eIDAS13 regulation, and the eID system, complete with mobile eID, is seamlessly integrated into the e‑government portal and the population register. Currently, many databases are connected to the government information system, and approximately 340 services are available on the national e‑government portal. 80% of these enable submission of forms and e-payment, although in some cases, a visit to the counter might still be required to complete the service (MPALSG, 2023[11]). The uptake of the eID system is rapidly increasing, with over 830 000 eIDs activated so far.

Despite these developments, several challenges persist. While progress has been made in establishing a robust technical framework and ICT infrastructure – ensuring interoperability and further integration of electronic registers – maximising the utilisation of digital government infrastructure and raising awareness of the benefits of digitalisation require further attention. The ex post assessment of the e‑Government Programme for 2020-22, conducted in March 2022, identified inadequate co-ordination among public authorities due to a lack of well-developed strategic management of e-Government reforms (Mysun En Natour, 2022[12]). Moreover, the mid-term implementation report of the PAR strategy up to June 2023, although positive in terms of implementation progress, highlighted the need to strengthen monitoring of service provision quality and user satisfaction, and to adopt a centralised approach with clear co-ordination mechanisms for service provision (MPALSG, 2023[11]). Furthermore, the same report unveiled persisting impediments to digitalisation, including a lack of pro-digitalisation culture among public sector officials, a shortage of digital skills among civil servants, and challenges in recruiting and retaining professional IT staff. In response, an electronic platform14 for constant visibility and monitoring of planned activities in public administration reform and public finance was established, to support informed decision making and improved results.

Serbia has made progress in supporting digital business development in the current assessment period. However, the impact of implemented activities remains limited due to the insufficient allocation of financial resources. Various policy documents come together to form a framework supporting enterprises, with a particular emphasis on small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), in digitalising their business operations and engaging in technological innovation. The Industrial Policy Strategy 2021‑30 and the Strategy for the Development of Information Society and Information Security 2021-26 delineate measures aimed at micro-SMEs digitalisation, e-business development, and enhancing digital skills for citizens and employees. Despite establishing the Council for Development of Digital Economy in 2021 to strengthen horizontal co-ordination, inadequate monitoring of the implementation of policy initiatives and programmes and the complete absence of impact assessments in this field necessitate immediate action.

The Centre for Digital Transformation (CDT) of the Chamber of Commerce and Industry successfully implemented the SME Digital Transformation Support Program in 2023, building on the accomplishments of the preceding SPEED 1.0 and SPEED 2.0 programmes in 2021 and 2022. These initiatives have provided valuable support to SMEs across sectors, facilitating equipment and software purchases and offering consulting services for digitalisation and engagement in digital innovation. Over the six years of its operation, more than 4 500 companies have applied for CDT programmes (Serbia Monthly, 2023[13]), indicating significant demand in similar initiatives. However, the allocation of financial resources falls short of meeting the industry’s demand. The Ministry of Information and Telecommunications (MIT), overseeing Information Society policy implementation, reported that 447 businesses applied for consulting services in the framework of the micro-SME Digital Transformation programme in 2022, and 272 projects received funding (MIT, 2022[14]). Additionally, the Digital Academy of the CDT, through its Fundamentals of Digital Transformation programme, offers free-of-charge digital skills training to managers and SME owners, contributing to a more digitally adept business landscape. Serbian businesses are also at the forefront of e-commerce engagement compared to the Western Balkan region, with 28.9% of enterprises with more than ten employees selling on line. This figure surpasses the EU average of 22.9% in 2023 (Eurostat, 2024[15]).

Serbia boasts a strong ICT industry with a dynamic IT ecosystem. The landscape includes 4 Science Technology Parks, 23 start-up centres, 5 IT clusters and more than 20 co-working hubs. The policy framework nurtures ICT industry growth, emphasising innovation, internationalisation, and Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) management. In 2022, 24 events were organised by competent authorities abroad to support businesses’ internationalisation, while 17 domestic events were organised to promote participation in business delegations abroad (MIT, 2022[14]). The Innovation Fund stands out as a pivotal instrument, notably supporting start-ups and SMEs, with ICT SMEs constituting most of its beneficiaries (51% of the total in 2022). The government has adopted the Strategy for the Development of Information Society and Information Security 2021-26 to support digital transformation of SMEs and electronic business development. Nevertheless, the challenges facing the ICT sector remain. The predominant constraint for ICT companies lies in the scarcity of IT professionals and the misalignment of ICT graduates' skills with labour market needs (Matijević and Šolaja, 2022[16]). Addressing this gap, the government is implementing key initiatives aimed at increasing the capacities of technical faculties in universities, enhancing programming in high schools, and implementing IT Retraining15 for the employed and unemployed according to surveyed industry needs, which has already trained 2 200 participants in two successful rounds completed so far.

Serbia has positioned itself as a pioneer in supporting emerging digital technologies in the Western Balkans, not only adopting a comprehensive policy framework for artificial intelligence (AI) development but also advocating ethical guidelines to ensure the responsible and reliable use of this transformative technology. Serbia ranks 57th out of 172 countries on the Government AI Readiness Index 2023, which is the best ranking in the Western Balkans (Oxford Insights, 2023[17]). The government adopted the Strategy for the Development of Artificial Intelligence 2020-25 to harness the potential benefits of AI for the economy’s advancement. The strategy encompasses over 30 projects, investing EUR 5 million in grants and equity for AI start-ups in Serbia. It also promotes the introduction of AI masters and Ph.D. programmes and boosts AI talent by retraining workers in AI skills. In 2021, the government took a significant step forward in establishing Serbia's Research and Development Institute for Artificial Intelligence. This institute serves as a catalyst for collaboration between public and private sector organisations, functioning as an incubator for AI start-ups. Actively engaging with international AI development events, the AI Institute plays a crucial role in raising awareness about diverse AI applications and building further on the skills of the existing IT talent pool in Serbia. Simultaneously, the Innovation Fund is pivotal in advancing the AI landscape by financing the GovTech programme, among other initiatives. This initiative is geared towards applying disruptive technologies to tackle public sector challenges, fostering collaboration between public and private entities, and ultimately fostering increased digitalisation. Through these efforts, Serbia is shaping a cohesive and forward-looking narrative for AI development and deployment. In December 2020, Serbia adopted the Law on Digital Assets to empower its innovative ecosystem and foster a welcoming business environment. This law recognises virtual currency and digital tokens as legal digital assets, paving the way for emerging opportunities in blockchain technology and creating new financing options for Serbian start-ups.

Sub-dimension 10.3: Society

Serbia has yet to yield significant tangible outcomes in its efforts toward digital inclusion, despite embedding measures to mitigate digital exclusion risks in various strategic documents. While the policy framework generally addresses digital inclusion challenges through activities implemented by different institutions, horizontal co-ordination and monitoring mechanisms for these activities are absent. Although social inclusion policies and action plans are monitored by the Public Policy Secretariat (RSJP), neither this body nor any other public institution is tasked with monitoring digital inclusion and performing relevant impact assessments. It is positive that the government has acknowledged the importance of enhancing digital literacy for vulnerable groups; it has outlined digital skills development initiatives in digital society policies, such as the Strategy for the Development of the Information Society and Information Security 2021-26 and the Strategy on the Development of Digital Skills for 2020-24. Additionally, measures contributing to digital inclusiveness are integrated into other strategic documents fostering equitable access for persons with disabilities, universal access to high-speed communications, child safety online, and access to e-government services for all citizens. Tangible results of policy implementation include the Ministry of Information and Telecommunications (MIT) allocating RSD 14 million (around EUR 120 000) to associations for the implementation of programmes aimed at raising the level of digital literacy and digital competencies of women in rural areas, training 1 530 women in the period 2021-22 (MIT, 2022[14]). However, no other vulnerable groups have had access to similar widespread training initiatives. Measures are planned but to be implemented to support groups at risk of digital exclusion, with financial subsidies for acquiring digital technologies; digital coupons for purchasing PCs, laptops or tablets; and free-of-charge digital skills training programmes.

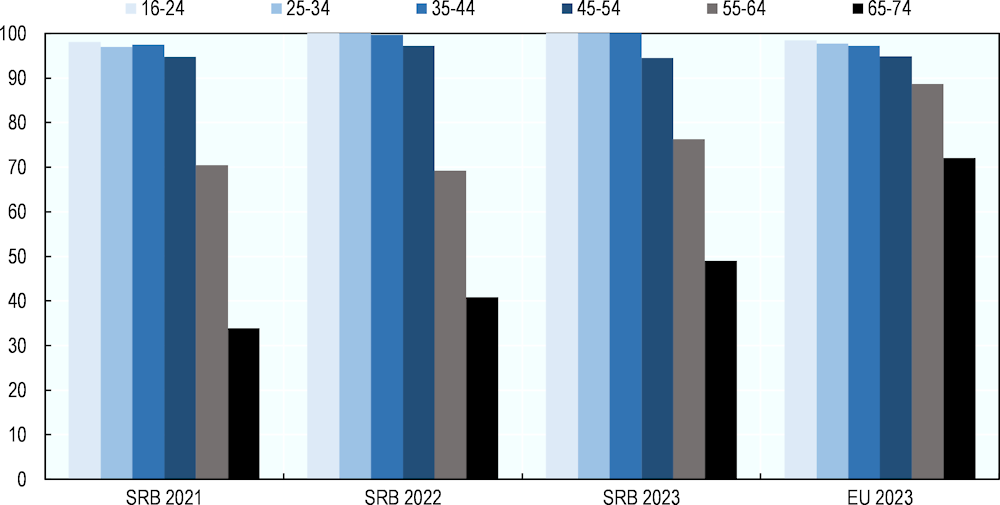

Moreover, while Serbia has adopted EU guidelines16 on e-accessibility since 2018, implementation is still lagging. Although some e-accessibility elements are embedded in the national e-government portal, the website of the Serbian Government17 and the Office for IT and e-Government (ITE), full compliance with international standards such as the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.0 is yet to be achieved in all public sector websites and applications. Furthermore, the legal framework lacks certification schemes for accessibility of ICT products and services, and public procurements have yet to embed such accessibility requirements. Notably, Internet usage has been increasing across age groups in the period 2021-23, according to the Statistical Office of Serbia. In 2023, 85.4% of individuals in Serbia used the Internet in the last three months, compared to the EU average of 91.41% (Figure 11.1). Additionally, while Internet users in the 65-74 age group marked the most significant increase, from 33.9% in 2021 to 49% in 2023, they are still behind the EU average in 2023 (72.07%).

Figure 11.1. Internet users (in the last three months) in Serbia according to age group, 2023

Share of age group expressed in percentage

Serbia currently lacks policies to ensure the integration of green digital technologies and environmentally sustainable practices into the digitalisation process. Programmes and policy initiatives designed to foster a green digital sector and harness its benefits for the green transition have yet to be developed. Existing digital society policies overlook the environmental impact of the ICT sector and the effect of the growing use of digital technologies on climate change. The current perspective on digitalisation primarily positions it to achieve eco-friendly outcomes. The government’s Green.gov.rs concept illustrates this approach, featuring an online platform for measuring the environmental benefits derived from the digitalisation of public administration and the adoption of e-government services. Policies and programmes, such as the Circular Economy Programme 2022-24 and Innovation Fund initiatives, are promoting the use of technological innovations, including ICTs, to improve the environmental footprint of existing public administration and industrial processes. On a different note, Serbia has adopted a Waste Management Programme for the period 2022-31 aimed at gradually establishing a waste management system in alignment with the EU acquis, including waste electrical and electronic equipment (e-waste). According to the Environmental Protection Agency, municipal e-waste accounted for 5.7% of the total waste streams in Serbia in 2020. Moreover, e-waste management infrastructure has yet to be fully developed or, in rural areas, is entirely absent (Marinković T., 2022[20]). The Programme acknowledges that household e-waste collection remains insufficient, and the government has initiated establishing a relevant system. Currently, waste electrical and electronic equipment management is addressed in the Law on Waste Management, which was last amended in April 2023 and reflects the two main principles of Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) for managing special waste streams. However, these principles have yet to be fully implemented in e-waste streams.

Sub-dimension 10.4: Trust

Serbia has significantly enhanced privacy and data protection since 2021, improving alignment with the EU acquis, enhancing implementation of the framework, and investing in civil servant training and awareness-raising campaigns. Nevertheless, while the situation regarding the protection of individuals’ rights has improved compared to previous years, it is not yet entirely satisfactory. The new Personal Data Protection (PDP) law, adopted in August 2023, is aligned with the EU GDPR,18 and accompanying regulations complete the alignment. While the Law is in the initial phase of implementation across the public and the private sectors, harmonisation of legacy legislation with the new law is pending. Additionally, challenges regarding law enforcement in personal data protection include the small size of imposed fines, unlike the GDPR, and the significant number of exceptions to the application of the Law, discouraging data practitioners’ compliance efforts. The Commissioner for Information of Public Importance and Protection of Personal Data has prepared a strategy for personal data protection until 2030, adopted in August 2023. This strategy emphasises the need for legal harmonisation, identifies the shortcomings of the current law, and outlines priority areas requiring attention due to rapid digitalisation, such as video and audio surveillance, biometrics, genetic personal data and artificial intelligence. The Commissioner’s Office employs 115 individuals for both fields of competence, empowering the authority to exercise its investigative and corrective powers within the Law. In 2022, the Commissioner reported a significant increase in PDP cases, attributed to heightened online activity and digitalisation, as well as increased awareness of personal data protection issues (Poverenik, 2022[21]). The Commissioner’s office actively provides training for diverse groups, supports personal data handlers in implementing the Law, and assists citizens in exercising their rights. In 2023 alone, the Commissioner’s office organised 38 PDP training sessions across Serbia, with over 1 450 participants from public authorities, civil society organisations, business associations, private sector actors, and university students and school pupils.

Public authorities have demonstrated improved compliance with the obligation to consult the Commissioner on relevant issues, submit draft legislation for review, and implement the Commissioner’s decisions. However, the Commissioner flags public authorities’ careless or untimely response and submission of evidence in relevant procedures (Poverenik, 2022[21]). A public opinion survey conducted in May 2023 for the Commissioner’s Office revealed that the majority of respondents are not familiar with their rights to personal data protection, and 80% consider the risk of personal data abuse to be high. Citizens are increasingly cautious toward private companies, but there is also a noticeable decline in trust in many public institutions regarding the lawful use of personal data. Almost half of the respondents (47.6%) are familiar with the work of the Commissioner, and 78.4% of those express confidence in the level of protection provided by the Commissioner’s Office (KANTAR, 2023[22]).

Serbia has made significant strides in consumer protection in e-commerce in the current assessment period, focusing on modernising its consumer protection framework, improving access to alternative dispute resolution (ADR) systems, and enhancing consumer education. Recognising the growing challenges in consumer protection and the increasing trend of e-commerce, Serbia’s Strategy for Consumer Protection 2019-24 outlined a comprehensive initiative to update consumer protection rules and enhance education for both consumers and traders regarding their rights and obligations in online transactions. As of early 2024, the legal framework on consumer protection, effective since March 2022, aligns significantly with the EU acquis, incorporating provisions from 14 key EU Directives in this area. The Consumer Protection Law has improved the ADR mechanism, imposed restrictions on direct advertising, enhanced the involvement of consumer protection associations in awareness campaigns and emphasised public sector capacity building to implement EU standards, including in e-commerce. To encourage consumers to seek redress through the courts if their issues are not resolved otherwise, the government waved court fees for filing a claim and rendered judgements. Additionally, the establishment of the National Consumer Protection Portal19 aims to provide educational resources for consumers and traders and facilitate the submission of complaints and requests for ADR. However, despite these reforms improving consumers’ ability to exercise their rights including in e-commerce transactions, further actions are needed to complete the alignment with consumer protection practices in EU Member States. Challenges include the non-binding character of recommendations issued by impartial ADR bodies, weakening the effectiveness of ADR mechanisms, and the absence of mechanisms for class action lawsuits, which proved particularly effective in EU Member States and internationally. The Strategy’s Action Plan for 2023-24 includes activities to draft amendments to the consumer protection law by the end of 2024, anticipated to address some of the existing shortcomings.

The Ministry of Internal and Foreign Trade, Department of Consumer Protection, has engaged in efforts to strengthen collaboration with consumer associations and local self-government and increase consumer awareness about the challenges posed by expanding e-commerce. In 2023, the ministry received nine competitive applications to finance consumer protection association programmes. In the first quarter of 2022, consumers in Serbia conducted 9.6 million e-commerce transactions with payment cards, a 31.2% increase year-over-year (RS, 2022[23]). According to the National Register of Consumer Complaints, despite the positive e-commerce trend, consumer complaints about online shopping decreased from 1 877 in 2020 to 1 673 in 2021, with only 7% of total consumer complaints in 2021 related to online shopping. This decline suggests that trust in e-commerce and online consumer protection in Serbia is gradually increasing.

Serbia has gradually advanced its cybersecurity capacity, albeit gradually, with a primary focus on strengthening the policy and legal framework and expanding capacity-building initiatives. Despite these efforts, challenges persist, particularly due to inadequate resources allocated to cybersecurity. The government is currently implementing two key strategies: the Strategy for the Development of Information Society and Information Security 2021-26 and the Strategy for the Fight Against Cybercrime for the period 2019-23, with an emphasis on aligning the framework with EU legislation. The government has improved inspection and incident reporting, leading to increased transparency in the cybersecurity domain. However, there is a need to enhance systematic approaches and transparency in monitoring policy implementation, particularly in conducting thorough analyses and impact assessments. The existing information security law defines critical information infrastructure, mandating operators of ICT systems of special importance to implement protective measures and strengthen systems’ resilience. While the law aligns with the EU Networks and Information Security (NIS) Directive,20 Serbia’s cybersecurity preparedness is not at the level commonly adopted by EU Member States. In response, an amendment is under way to facilitate alignment with the updated EU NIS legislation (the NIS2 Directive21) and the EU Cybersecurity Act.22 Establishing the Agency for Security of Networks and Information Systems and Digital Transformation, anticipated in 2025, is crucial for strengthening collaboration and information exchange with NIS authorities in EU Member States. Additionally, cybersecurity certification for ICT products, services and processes has yet to be adopted, and reforms consistent with the EU Toolbox for 5G Cybersecurity23 are pending to ensure secure development of forthcoming 5G implementations.

Despite policy commitments and legislative reforms, Serbia’s cybersecurity system is hampered by insufficient human and financial resources. However, the country's potential to nurture cybersecurity expertise is significant, supported by a growing ICT industry and academic discussions on expanding graduate and undergraduate cybersecurity programmes. Retaining cybersecurity professionals poses a challenge for the government due to the high demand in the industry. The Sector for Information Society and Information Security, within the Ministry of Information and Telecommunications, operates with ten staff members and the national CERT operates with seven employees as a unit of RATEL, the electronic communications regulator. Nonetheless, collaborative efforts are evident, with regular meetings and data exchange occurring between the national CERT and computer emergency response teams from the public and private sectors, including the Governmental CERT operating as a unit of the Office for IT and e-Government (ITE). Notably, the government exceeded the original targets outlined in the Information Security strategy regarding cybersecurity training volume. The National Academy for Public Administration (NAPA) conducted 134 training sessions under the General Civil Servant Training Programme for 2022, training 6 338 public administration and local self-government employees on cybersecurity and digital skills (MIT, 2022[14]). Moreover, the Ministry of Public Administration, RATEL and NAPA trained 340 individuals in ICT systems of special importance, in addition to 44 individuals from public and private CERTs. The government also developed a guide for SMEs, offering practical instructions on implementing simple and affordable cybersecurity measures based on proved good practice examples.

Overview of implementation of Competitiveness Outlook 2021 recommendations

Serbia’s progress in implementing Competitiveness Outlook 2021 Recommendations has been varied. The economy has made strong advances in promoting open data innovation and personal data protection. However, it has only moderately addressed recommendations regarding the electronic communications sector and the systematisation of digital government monitoring. On the contrary, there has been stagnation regarding digital inclusion initiatives. Table 11.2 shows the economy’s progress in implementing past recommendations for developing a digital society.

Table 11.2. Serbia’s progress on past recommendations for digital society policy

|

Competitiveness Outlook 2021 recommendations |

Progress status |

Level of progress |

|---|---|---|

|

Accelerate the adoption of new laws and regulations to ensure an enabling ICT investment framework, including the new Law on Electronic Communications and the Law on Broadband Development |

The new Law on Electronic Communications was enacted in May 2023. It improves alignment with the European Electronic Communications Code. Complementary regulations are pending. The draft Law on Broadband Development and subsequent regulations completing alignment with the Broadband Cost Reduction Directive have not yet been adopted. |

Moderate |

|

Strengthen the demand for open data innovation through inclusive co-creation processes to enable reuse of public sector data by the private sector to deliver e-services and applications to citizens |

The Open Data portal is a one-stop-shop for the entire open data ecosystem in Serbia, which is comprised of individuals, start-ups, companies, experts, institutions, media, and the civil sector. The portal fosters 2 399 datasets as of January 2024 and highlights 42 examples of data use-cases in various thematic domains, promoting data innovation and the creation of data services. The portal includes an area for developers, comprising API interface documentation, examples and instructions on how to use datasets. The Open Data Hub (https://hub.data.gov.rs) provides a lively space for meetups, workshops, and open data education that has been available to the entire open data ecosystem since 2021. |

Strong |

|

Systematise the monitoring of digital government indicators to support informed policy making |

Ex post impact assessment of the e-Government Development Programme 2020-22 was performed and published online in 2022. An interim report on the implementation of the PARS strategy is also publicly available. However, there is a lack of a digital government indicators database and a systematic approach for regular policy implementation monitoring. Such a database and/or reports could be published regularly on the Office of IT and e-Government website. |

Moderate |

|

Empower citizens to reap the benefits of digitalisation and monitor progress in digital inclusion |

The government has not assigned co-ordination and policy implementation monitoring regarding digital inclusion initiatives to any state institution. There is no single database or online repository where digital inclusion indicators are accessible. Data are arbitrarily published by diverse government bodies monitoring indicators that directly or indirectly impact digital inclusion (e.g. RATEL, the Statistical Office, etc.). Digital skills training for vulnerable groups have not been implemented, except for around 1 500 women in rural areas under the Strategy for the Development of the Information Society and Information Security. |

Limited |

|

Complete the alignment of the framework for personal data protection with the EU and ensure its stronger enforcement |

The Law on Personal Data Protection, along with supplementary regulations enacted in 2019 and 2020, exhibits substantial alignment with the EU GDPR. Some further harmonisation with existing legislation is still required. The Personal Data Protection Strategy 2030 outlines specific legislative reforms. There is overall improvement in the state of personal data protection enforcement and respect for the Commissioners’ decisions. |

Strong |

The way forward for digital society

Considering the level of the previous recommendations’ implementation, there are still areas in which Serbia could enhance the digital society policy framework and further improve aspects of access to electronic communications and public data, digitalisation of government and businesses, inclusiveness of the digital society, and trust in digital technologies. As such, policy makers may wish to:

Undertake comprehensive legal and regulatory reforms to foster private sector investments in high-speed communications networks. Necessary reforms include the long-delayed adoption of the Law on Broadband Infrastructure to align with the EU Broadband Cost Reduction Directive and consideration of the 2023 revised EC Guidelines on state aid rules for developing broadband infrastructure. The electronic communications regulator should accelerate the adoption of regulations accompanying the new law on electronic communications in line with the EU Delegated Act to eliminate roaming charges with EU Member States, and the updated EC Recommendation on relevant markets. Serbia should actively consider and integrate the EU Connectivity Toolbox and expedite 5G spectrum auctions, eagerly anticipated by market investors, to facilitate the rollout of commercial 5G services.

Prioritise adopting updated legislation on reusing public sector information and take measures to enhance the development of trustworthy data-sharing systems. Ensure complete alignment with the EU Open Data Directive and amend existing legislation following the EU Data Governance Act to introduce rules for trustworthy data intermediary services. These reforms will facilitate data sharing across sectors and borders and ensure the reuse of public sector data, including those that cannot be made available as open data, such as health data. The government should specifically focus on establishing real-time, linked, interoperable Data Spaces that function as data marketplaces. This initiative aligns with the Common European Data Spaces concept, boosting the data economy and capitalising on the momentum building up in the domestic open data ecosystem.

Increase cross-border interoperability in the government's digitalisation and introduce cross-border e-services. As Serbia progresses towards EU Accession, the government could consider streamlining its national eID scheme to ensure interoperability with EU Member States by applying common standards and requirements for electronic identification and trust services. Serbia is well positioned to follow developments regarding the forthcoming European Digital Identity Wallet introduction. These reforms will foster collaborations with EU Member States and facilitate the effective deployment of cross-border services (Box 11.1).

Strengthen horizontal co-ordination and oversight of digital inclusion initiatives and introduce accessibility criteria for ICT products and services in public procurement. Despite ongoing efforts to cultivate an inclusive information society through various policies and programmes addressing digital skills, e-government services and broadband infrastructure, there is a need for more effective collaboration among state bodies implementing measures that impact digital inclusion development. The government should assign a dedicated body to coordinate relevant activities with implementing institutions horizontally, ensuring cohesive data collection to facilitate impact assessments and evaluation of measures’ efficacy. This entity could also spearhead the development of future digital inclusion policies or initiatives and ensure the application of accessibility requirements for ICT products and services in public procurement processes based on established accessibility standards.

Box 11.1. Access Luxembourg’s online public services from another European country

Interoperability between the various means of electronic identification used in the 27 EU Member States and Iceland, Norway and Liechtenstein (European Economic Area) is progressing rapidly. The eIDAS-compliant ecosystem aims to enable citizens and businesses to carry out administrative procedures online in any other European country using the authentication system recognised in their own country. The eIDAS Regulation establishes the cross-border recognition of national electronic identification schemes, in cases where Member States have notified these schemes.

Since the end of 2022, identification systems used in 14 Member States (Belgium, the Czech Republic, Germany, Denmark, Estonia, Spain, Croatia, Italy, Latvia, Malta, the Netherlands, Portugal, Sweden and Slovakia) can be used to connect to the following Luxembourg online public services:

Luxembourg Business Registers (lbr.lu): Trade and Companies Register (RCS), Register of Beneficial Owners (RBE), etc.

eCDF.lu, the platform for the electronic gathering of financial data

Public Procurement Portal.

According to the same principle, Luxembourg citizens can access the online public services of 22 other Member States, the European Commission, and Liechtenstein with an electronic identity card (eID).

Source: Government of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg (2024[24]).

Increase human and financial resources for cybersecurity and introduce cybersecurity certification requirements for ICT products and services. While alignment of the information security law with the EU Directive on measures for a high common level of cybersecurity across the Union (NIS2) is under way, current staff and financial resources earmarked for cybersecurity are insufficient to combat cybercrime effectively. The government should prioritise the substantial enhancement of operational capacities for both the national CERT and the forthcoming Cybersecurity Agency, empowering them to elevate Serbia’s cyber-resilience and foster increased collaboration and information sharing with competent authorities abroad (see Box 11.2). Additionally, a key focus should be the timely introduction of cybersecurity certification for ICT products, services, and systems, which should align with the EU Cybersecurity Certification Framework and the EU Cybersecurity Act. In preparation for the 5G spectrum auctions in 2024, the government is advised to implement the EC Recommendations on Cybersecurity of 5G Networks.

Box 11.2. Increasing the United Kingdom’s cyber security capability

The United Kingdom initially established a National Cyber Security Strategy to ensure that “the UK has a sustainable supply of home-grown cyber skilled professionals to meet the growing demands of an increasingly digital economy, in both the public and private sectors, and defence”. However, due to the increasing demand for digital security skills, it now seeks to go much further.

The government’s ambition is to address the broader cyber security capability gap: ensuring the right skilled professionals are in the workforce now and in the future; that organisations and their staff are equipped to manage their cyber risks effectively, and that individuals have an understanding of the value of their personal data and are able to adopt basic cyber hygiene to keep themselves and the organisations they work for protected.

Its mission is, therefore, to increase cyber security capacity across all sectors to ensure that the United Kingdom has the right level and blend of skills required to maintain resilience to cyber threats and be the world’s leading digital economy.

It will pursue its mission by working toward the following objectives:

to ensure the United Kingdom has a well-structured and easy to navigate profession which represents, supports and drives excellence in the different cyber security specialisms, and is sustainable and responsive to change

to ensure the United Kingdom has education and training systems that provide the right building blocks to help identify, train, and place new and untapped cyber security talent

to ensure the United Kingdom’s general workforce has the right blend and level of skills needed for a truly secure digital economy, with UK-based organisations across all sectors equipped to make informed decisions about their cyber security risk management

to ensure the United Kingdom remains a global leader in cyber security with access to the best talent, with a public sector that leads by example in developing cyber security capability.

Source: Initial National Cyber Security Skills Strategy: Increasing the UK’s Cyber Security Capability - A Call for Views, Executive Summary, Government of the United Kingdom (2019[25]).

References

[9] Capgemini, Sogeti, IDC and Politecnico di Milano (2023), The eGovernment Benchmark 2023, European Commission, Directorate-General for Communications Networks, Content and Technology, https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/egovernment-benchmark-2023.

[3] European Commission (2023), Serbia 2023 Report, Directorate-General for Neighbourhood and Enlargement Negotiations, Brussels, https://neighbourhood-enlargement.ec.europa.eu/document/download/9198cd1a-c8c9-4973-90ac-b6ba6bd72b53_en?filename=SWD_2023_695_Ser.

[15] Eurostat (2024), “E-commerce sales of enterprises by size class of enterprise”, Enterprises with E-Commerce Sales, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/isoc_ec_esels/default/table?lang=en&category=isoc.isoc_e.isoc_ec. (accessed on 15 May 2024).

[10] Eurostat (2024), “E-government activities of individuals via websites”, Internet Use Obtaining Information from Public Authorities Web Sites (last 12 months), https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/isoc_ciegi_ac/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 15 May 2024).

[18] Eurostat (2024), “Individuals- internet use”, Last Internet Use in the Last 3 Months, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/isoc_ci_ifp_iu/default/table (accessed on 15 May 2024).

[5] Eurostat (2024), Individuals’ Level of Digital Skills (from 2021 onwards), https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/isoc_sk_dskl_i21__custom_9882830/bookmark/table?lang=en&bookmarkId=ca727989-dcca-4872-9a11-051d8950f01e (accessed on 15 May 2024).

[24] Government of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg (2024), Guichet.lu, https://guichet.public.lu/en/citoyens/actualites/2022/decembre/05-services-publics-depuis-autre-pays-europeen.html (accessed on 15 May 2024).

[25] Government of the United Kingdom (2019), Gov.UK, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/cyber-security-skills-strategy/initial-national-cyber-security-skills-strategy-increasing-the-uks-cyber-security-capability-a-call-for-views-executive-summary (accessed on April 2024).

[22] KANTAR (2023), Citizens’ Perception of Personal - Public Opiniion Research, Kantar Serbia, TMG Insights, https://www.poverenik.rs/images/stories/dokumentacija-nova/Publikacije/Prezentacija_rezultati_istra%C5%BEivanja_OEBS-Poverenik-Kantar/041223_Report_Citizens_Perception_of_Personal_Data_Protection_050723.pdf.

[20] Marinković T., B. (2022), Challenges in Applying Extended Producer Responsibility Policies in Developing Countries: A Case Study in e-Waste Management in Serbia, Conference: 9th International ConferenceonSustainable Solid WasteManagementAt: Corfu, Greece, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/369377340_Challenges_in_applying_extended_producer_responsibility_policies_in_developing_countries_A_case_study_in_e-waste_management_in_Serbia.

[16] Matijević, M. and M. Šolaja (2022), ICT in Serbia - At a Glance, Vojvodina ICT Cluster, https://vojvodinaictcluster.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/ICT-in-Serbia-At-a-Glance-2022.pdf.

[14] MIT (2022), 2022 Annual Report of the Action Plan for the Implementation of the Strategy for Information Society Development and Information Security for the Period from 2021-2023, https://www.mit.gov.rs/tekst/702/sektor-za-informaciono-drustvo-i-informacionu-bezbednost.php.

[11] MPALSG (2023), Mid-Term Review and Evaluation of the Impact of the Action Plan (2021-2025) for the Implementation of the Public Administration Reform Strategy in the Republic of Serbia (2021-2030) - Evaluation Period: January 2021 - June 2023, http://mduls.gov.rs/wp-content/uploads/Mid-Term-evaluation-AP-PARS-Final-Report_ENG-FINAL.docx.

[12] Mysun En Natour, A. (2022), Ex-post Analysis of the Electronic Government Development Programme in the Republic of Serbia for the Period 2020-2022, project: EuropeAid/137928/DH/SER/RS, http://mduls.gov.rs/wp-content/uploads/External-ex-post-analysis-E_Gov-Program-2020_2022_ENG.docx.

[1] OECD (2021), Competitiveness in South East Europe 2021: A Policy Outlook, Competitiveness and Private Sector Development, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/dcbc2ea9-en.

[17] Oxford Insights (2023), Government AI Readiness Index, https://oxfordinsights.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/2023-Government-AI-Readiness-Index-2.pdf.

[8] Page, M. et al. (2023), 2023 Open Data Maturity Report, Publications Office of the European Union, https://doi.org/10.2830/384422.

[21] Poverenik (2022), Annual Report, Commissioner for information of public importance and protection of personal data, https://www.poverenik.rs/images/stories/dokumentacija-nova/izvestajiPoverenika/2022/Godi%C5%A1nji_izve%C5%A1taj_2022_-_16_03_2023.pdf.

[6] RATEL (2023), Overview of the Electronic Communications Market in the Republic of Serbia - Third Quarter of 2023, Regulatory Body for Electronic Communications and Postal Services (RATEL), https://ratel.rs/cyr/page/cyr-kvartalni-podaci-elektronske-komunikacije.

[7] RS (2024), By the End of 2025, Every Place in Serbia will Have High-Speed Internet, https://www.srbija.gov.rs/vest/en/219369/by-the-end-of-2025-every-place-in-serbia-will-have-high-speed-internet.php.

[4] RS (2023), Serbia One of Leaders in Development of Artificial Intelligence, https://www.srbija.gov.rs/vest/en/217170/serbia-one-of-leaders-in-development-of-artificial-intelligence.php.

[23] RS (2022), Economic Reform Programme 2022-2024, Government of the Republic of Serbia, https://rsjp.gov.rs/wp-content/uploads/Economic-Reform-Programme-2022-2024.pdf.

[13] Serbia Monthly (2023), New The Innovation Hub of the Center for Digital Transformation (CDT) Opened in December, https://serbiamonthly.com/new-the-innovation-hub-of-the-center-for-digital-transformation-cdt-opened-in-december/ (accessed on 10 July 2024).

[2] Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia (2024), Gross Value Added by Activities, NACE Rev. 2 (% of GDP), https://data.stat.gov.rs/?caller=SDDB&languageCode=en-US (accessed on 15 May 2024).

[19] Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia (2024), STAT Database, https://data.stat.gov.rs/?languageCode=en-US (accessed on 15 May 2024).

Notes

← 1. Project of joint construction of broadband communication infrastructure in rural areas of the Republic of Serbia, https://www.mit.gov.rs/tekst/194/projekat-zajednicke-izgradnje-sirokopojasne-komunikacione-infrastrukture-u-ruralnim-predelima-republike-srbije.php.

← 2. Communication from the Commission Guidelines on State aid for broadband networks 2023/C 36/01, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A52023XC0131%2801%29.

← 3. Communication from the Commission — EU Guidelines for the application of State aid rules in relation to the rapid deployment of broadband networks 2013/C 25/01, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52013XC0126(01).

← 4. Directive 2014/61/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 May 2014 on measures to reduce the cost of deploying high-speed electronic communications networks (Text with EEA relevance), https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2014/61.

← 5. Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2021/654 of 18 December 2020 supplementing Directive (EU) 2018/1972 of the European Parliament and of the Council by setting a single maximum Union-wide mobile voice termination rate and a single maximum Union-wide fixed voice termination rate (Text with EEA relevance), http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg_del/2021/654/oj.

← 6. Commission Recommendation (EU) 2020/2245 of 18 December 2020 on relevant product and service markets within the electronic communications sector susceptible to ex ante regulation in accordance with Directive (EU) 2018/1972 of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing the European Electronic Communications Code (notified under document C[2020] 8750) (Text with EEA relevance), http://data.europa.eu/eli/reco/2020/2245/oj.

← 7. Directive (EU) 2019/1024 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 June 2019 on open data and the reuse of public sector information (recast), http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2019/1024/oj.

← 8. Regulation (EU) 2022/868 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2022 on European data governance and amending Regulation (EU) 2018/1724 (Data Governance Act) (Text with EEA relevance), http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2022/868/oj.

← 9. GeoSrbija (https://geosrbija.rs/) is a national digital platform that provides insight into the National Infrastructure of Geospatial Data, a database of all geospatial data of the Republic of Serbia that can be used by citizens, state authorities, businesses and the public sector. GeoSrbija offers more than 335 datasets from various institutions and 44 geospatial data services, processing around 10 million requests per year.

← 10. National open data portal: https://data.gov.rs/sr/.

← 11. Open Data Hub: https://hub.data.gov.rs/. The ODH is a one-stop-shop for all the participants in the open-data ecosystem in Serbia (individuals, start-ups, companies, experts, institutions, media, civil sector), offering support in tapping into and using open data and ancillary processes. It came into existence as part of the Open Data Initiative, which was launched in Serbia in 2015.

← 12. The open data maturity (ODM) assessment is part of the European Commission’s data portal (data.europa.eu) aiming to evaluate countries' maturity in the open data field. In particular, the assessment measures the progress of European countries in making public sector information available and stimulating its reuse, in line with the open data directive (Directive [EU] 2019/1024).

← 13. Regulation (EU) No. 910/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 July 2014 on electronic identification and trust services for electronic transactions in the internal market and repealing Directive 1999/93/EC, http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2014/910/oj.

← 15. The IT Retraining programme, https://itobuke.rs.

← 16. Directive (EU) 2016/2102 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 October 2016 on the accessibility of the websites and mobile applications of public sector bodies (Text with EEA relevance), http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2016/2102/oj.

← 17. Website of the Government of the Republic of Serbia, https://www.srbija.gov.rs.

← 18. Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation), http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/679/oj.

← 19. National Consumer Protection Portal: https://zastitapotrosaca.gov.rs.

← 20. Directive (EU) 2016/1148 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 6 July 2016 concerning measures for a high common level of security of network and information systems across the Union, http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2016/1148/oj.

← 21. Directive (EU) 2022/2555 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 December 2022 on measures for a high common level of cybersecurity across the Union, amending Regulation (EU) No. 910/2014 and Directive (EU) 2018/1972, and repealing Directive (EU) 2016/1148 (NIS 2 Directive) (Text with EEA relevance), http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2022/2555/oj.

← 22. Regulation (EU) 2019/881 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 April 2019 on ENISA (the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity) and on information and communications technology cybersecurity certification and repealing Regulation (EU) No. 526/2013 (Cybersecurity Act) (Text with EEA relevance), http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2019/881/oj.

← 23. Cybersecurity of 5G networks - EU Toolbox of risk mitigating measures, https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/cybersecurity-5g-networks-eu-toolbox-risk-mitigating-measures.