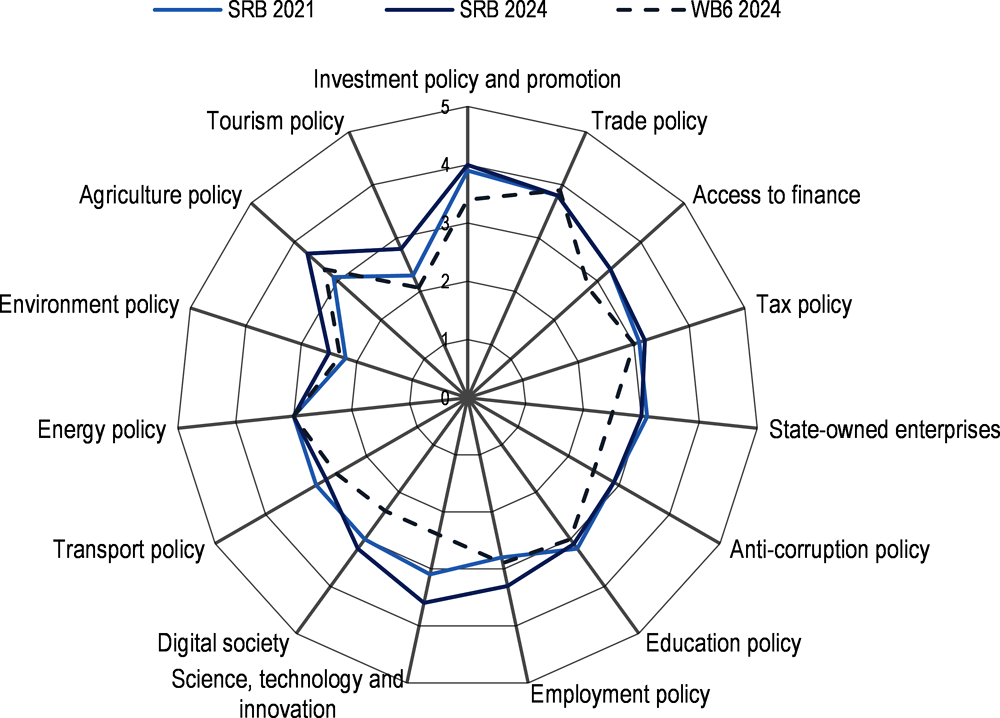

Serbia has made notable progress across 8 of the 15 policy dimensions since the 2021 Competitiveness in South East Europe: A Policy Outlook (Competitiveness Outlook), with the strongest score increases in the areas of agriculture; science, technology and innovation (STI); and employment policies illustrates that Serbia is outperforming the average of the six Western Balkan (WB6) economies across 13 policy dimensions, with only trade and energy policy lagging behind. Serbia positions itself as a regional leader, with the highest score in five areas: 1) investment policy and promotion; 2) STI; 3) digital society; 4) agriculture; and 5) access to finance policies. By contrast, it scores below at least two of its Western Balkan neighbours in the areas of trade, energy and tax policies, highlighting the areas requiring improvement for achieving convergence with the European Union (EU). For additional insights into Serbia’s performance across various dimensions, trends over time or comparisons with other economies, please refer to the Western Balkans Competitiveness Data Hub at: https://westernbalkans-competitiveness.oecd.org.

Western Balkans Competitiveness Outlook 2024: Serbia

Executive summary

Performance overview

Figure 1. Scores for Serbia across Competitiveness Outlook policy dimensions (2021 and 2024)

Note: Dimensions are scored on a scale of 0 to 5. See the Reader’s guide and the Data Hub at: https://westernbalkans.competitiveness.oecd.org for information on the assessment methodology and the individual score assigned to indicators.

Source:

Main progress areas

The main achievements that have led to increased performance for Serbia since the last assessment are as follows:

Efforts towards building a digital society have gained momentum. Significant progress has been made in expanding broadband infrastructure, with fibre network access extended to rural areas, increasing from 74% in 2021 to nearly 80% by 2023. The implementation of the e‑government programme has boosted the digitalisation of the public administration and the delivery of e-services. Among Western Balkan economies, Serbia has the highest percentage of individuals who use the Internet to interact with public authorities (51.1%), surpassing the EU average (50.7%). With a dedicated policy framework, Serbia is pioneering the use of emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), highlighted by establishing the Research and Development Institute for AI in 2021.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows have surged due to an open investment regime coupled with non-distorting incentives. Over the past decade, Serbia has successfully attracted a growing amount of FDI, with net inflows rising from USD 2.3 billion in 2015 to USD 4.5 billion in 2023. With more than one-quarter of this FDI directed into manufacturing, Serbia’s productive capacity and competitiveness have been significantly bolstered. The adoption of a mix of policy measures, including cost-based incentives in line with OECD good practices, to attract investment in high-value and export-oriented sectors has been instrumental in this success.

The productivity of the agriculture sector has shown signs of improvement. Despite the steady decline in total employment within the agriculture sector over the past decade, from 21.2% in 2011 to 13.9% in 2021, the sector's share of national gross domestic product (GDP) has remained constant, hovering around 6%. The improvements in irrigation and drainage infrastructure, the wide availability of producer support instruments, well-developed information systems, and growing efforts in advisory services have boosted the productivity of Serbia’s agriculture sector. Notably, Serbia is the only economy in the Western Balkans with a trade surplus in its agrifood sector.

Employment policies addressing skills gaps and mismatches, particularly among young people, have been strengthened. Serbia's level of young people not in education, employment or training (NEET) is 12.9%, which exceeds the EU average of 9.6%; however, it has significantly fallen from 17% in 2018 and is currently the lowest in the Western Balkans. Enhanced policy focus and measures have contributed to this achievement. In 2022, Serbia established the Office for Dual Education and implemented the National Qualifications Framework. Through engagement with employers, this institution has worked to better align curricula and educational/training opportunities with the demands of the labour market. Additionally, the adoption of the Youth Guarantee Implementation Plan has intensified policy attention on youth.

Governance and funding for STI policies have further improved. The institutional setup for STI policy was streamlined in 2022 with the creation of the new Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation, consolidating responsibilities and reducing the risk of overlapping mandates and conflicting priorities. Despite room for improvement, gross domestic expenditure on research and development is increasing, accounting for around 1% of GDP. Serbia has further committed itself to increasing public investments in research and development (R&D) by 50% between 2013 and 2018, and public sector spending has already begun to increase, primarily through the Science Fund. Serbia has also secured large-scale investments to further expand its network of science and technology parks (STP) and construct a state-of-the-art biotechnology park.

Policy insights

To further improve its competitiveness and boost its economic convergence with the EU and OECD, Serbia is encouraged to:

Foster competition and deregulation in the energy sector. Backed by an advanced legal framework, Serbia became the first economy in the Western Balkans to establish an intraday electricity market in 2023. Nevertheless, deregulation remains limited, primarily due to the dominant position of established suppliers hindering the emergence of truly competitive power markets. To encourage competition, alternative suppliers must be incentivised. A more extensive opening of the energy market would not only enhance efficiency and reduce prices, but also foster a resilient and diversified energy landscape in Serbia. This would decrease reliance on single sources and strengthen the overall energy infrastructure.

Enhance trade facilitation to make it easier and more efficient for businesses to import and export goods. Serbia stands to benefit from further digitalisation and simplification of administrative procedures, given the potential for increased trade flow and reduced costs. Currently, full-time automated processing for customs is not available, and electronic documentation has not been extended to all trade documents, necessitating notarised hard copies for various products and services. Moreover, there is a need to improve the inclusiveness of consultations with the private sector by providing adequate and timely information on regulatory changes and enhancing opportunities for the private sector to comment on trade-related regulations.

Explore tax policies to address informality. High social security contributions (SSCs) and the limited progressivity of personal income tax (PIT) place a heavy tax burden on labour, particularly for lower-income workers. Reduced SSC rates and lower bottom-tier PIT rates can reduce barriers to formal employment. The design and operation of the value added tax (VAT) system also require improvements. Lowering the very high VAT threshold (EUR 68 000) and enhancing the implementation of electronic invoicing would enhance the neutrality of the tax, reduce distortions and potentially increase revenues by promoting greater formality.

Continue strengthening the governance of state-owned enterprises (SOEs). Many SOEs in Serbia either do not achieve significant rates of return or operate at a loss, pointing to structural issues that hamper efficient resource allocation. To address this, it is crucial to bolster the monitoring of SOE performance. This entails a thorough analysis of the root causes of SOEs’ underperformance and quantification of the impact of any public policy objectives on SOEs’ finances. Good practices indicate that the costs associated with SOEs’ public service obligations should be transparently identified, with only those costs being compensated from the state budget.

Strengthen and incentivise public bodies to step up anti-corruption efforts. Serbia boasts robust legal frameworks and measures to combat corruption. However, effectively suppressing corruption demands more than the mere functioning of laws and institutions but necessitates comprehensive efforts across the entire public sector. Introducing a legal guarantee that ensures all planned anti-corruption actions are backed by adequate state funding would enhance the capacity of anti-corruption bodies and strengthen their activities. Furthermore, providing additional incentives for public bodies, such as integrating the progress of anti-corruption actions into key performance indicators and regularly publishing data on their implementation progress, would contribute towards a comprehensive approach.