This chapter offers an overview of Serbia’s economic developments since the Competitiveness Outlook 2021, with a special focus on the economic impact of recent external shocks and economic convergence. The chapter also examines the progress made and challenges encountered in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. It also recaps the progress made towards EU accession, including the financial and development support provided by the EU for Serbia's accession efforts. Altogether, this sets the stage for in-depth examination across 15 policy dimensions in the subsequent chapters, all necessary for sustaining economic competitiveness.

Western Balkans Competitiveness Outlook 2024: Serbia

1. Context

Abstract

Economic context

Key economic developments

Serbia is the largest economy of the Western Balkans, with a total gross domestic product (GDP) of EUR 68 billion as of 2023 (IMF, 2024[1]). It is predominantly services-based: services account for 52% of its GDP. Industry and agriculture respectively contribute 25.6% and 6.5% to GDP World Bank (World Bank, 2021[2]). Meanwhile, 57% of employment is concentrated in services, while industry and agriculture comprise 29% and 14% of employment, respectively (ILO, 2024[3]). The informal sector is estimated to account for 18.7% of employment as of 2019 (ILO, 2023[4]) (Table 1.1).

Over the assessment period, Serbia’s economy remained largely resilient, though growth has been slower than that in other economies in the Western Balkans. Serbia’s economic downturn in 2020 from the COVID-19 pandemic was shallow, with a decline in GDP of -0.9%. GDP growth rebounded to 7.7% in 2021 and decelerated rapidly to 2.5% in 2022 and approximately 2% in 2023 (European Commission, 2024[5]; IMF, 2024[6]). On the supply side, construction, agriculture, and information and communications proved to be the main growth drivers by sector towards the end of 2023, while industry and mining also posted positive growth (European Commission, 2024[5]). On the expenditure side, Serbia’s growth performance was largely supported by private consumption and investment supported by FDI inflows (European Commission, 2024[5]). Private investment, on the other hand, remains low, presenting a barrier to growth (World Bank, 2020[7]). Serbia’s private sector annually invested 2.7% of GDP less than its Western Balkan neighbours and nearly 6% less than those in Central and Eastern Europe1 (World Bank, 2020[7]), underscoring Serbia’s comparatively slow growth and highlighting areas requiring further development.

Inflation has been moderately high compared to other economies in the region over the observed period. Consumer price inflation peaked at 16.2% in 2023 due to rising international food and energy prices (IMF, 2024[8]). Inflation slowed to 8% by November 2023, but still remained well above its upper target rate of 3% (European Commission, 2024[5]). Annual inflation was primarily fuelled by food prices, but they slowed down towards the end of 2023 as global food prices began to ease. Moreover, increases in electricity and gas tariffs (24% and 33%, respectively), as stipulated in the standby-arrangement (SBA) with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), also contributed to rising inflation in 2023.

Despite the significant challenges, Serbia’s labour market has remained resilient, with unemployment reaching a record low of 8.7% by 2022 (ILO, 2024[3]). Labour force participation rates among adults between the ages of 15 and 64 have improved, increasing from 68% in 2020 to 73.2% in 2022 (ILO, 2024[3]). Youth unemployment declined from 27.7% in 2020 to 24.4% in 2022, while labour force participation among young people increased over the same time. Average salaries and wages have continued to rise, increasing by 14.8% in nominal terms and 2.4% in real terms over 2020 to 2023 (Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia, 2024[9]). (See the employment policy chapter for more details on labour market developments.)

Serbia’s external sector expanded considerably from 2019 to 2022 but contracted in 2023. Exports decreased by 1.5% from 2022 to 2023 (dampened by low external demand), while imports contracted by 1.2% in the same year. The negative net export growth impact in 2023 is largely attributable to the inventory buildup of gas and oil. In 2022, net FDI inflows reached 7.1%. Over the first 10 months of 2023, net FDI inflows increased by about 8% relative to 2022, being close to record levels as a share of GDP and covering multiple (3.4) times the current account deficit. Amid high international energy prices ensuing from the Russian Federation’s war of aggression against Ukraine and unforeseen domestic supply disruptions, Serbia’s energy imports contributed to the reduction of the current account deficit due to lower-than-expected energy prices and reduced demand resulting from mild winter conditions (IMF, 2023[10]). Serbia’s exchange rate has largely held stable, as the National Bank of Serbia has continued to intervene in the foreign exchange market to relieve appreciation pressures on the dinar.

The government’s fiscal position is still in recovery following the COVID-19 pandemic, with fiscal consolidation resuming in 2021 and a steadily improving though still negative gross government balance of -3.0% in 2022 (European Commission, 2024[5]; IMF, 2023[10]). Serbia’s fiscal revenues increased by 11.8% over January to November 2023, propped up by social contributions, corporate income tax, personal income tax, excise duties and grants, while value added tax (VAT) also increased moderately. Government expenditures expanded in line with the increase in revenue. Public debt shot up from 52% to 57% in 2020 but declined to 52.7% by 2023, having yet to reach pre-pandemic level. In 2022, Serbia’s sovereign ratings were upgraded and now stand only one notch below investment grade (IMF, 2023[10]). Serbia issued its debut green Eurobond of EUR 1 billion in September 2021, becoming one of the few European countries and the only non-EU European economy to issue the green Eurobond (National Bank of Serbia, 2024[11]). Investor demand for the bond exceeded EUR 3 billion (Scope Ratings, 2022[12]).

Table 1.1. Serbia: Main macroeconomic indicators (2019-23)

|

Indicator |

Unit of measurement |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023e |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

GDP growth |

% year-on-year |

4.3 |

-0.9 |

7.7 |

2.5 |

.. |

|

National GDP |

USD billion |

51.5 |

53.4 |

63.1 |

63.6 |

.. |

|

Inflation |

% average |

1.8 |

1.6 |

4.1 |

12.0 |

.. |

|

Current account balance |

% of GDP |

-6.9 |

-4.1 |

-4.2 |

-6.8 |

.. |

|

Exports of goods and services |

% of GDP |

51.0 |

48.2 |

54.9 |

63.8 |

.. |

|

Imports of goods and services |

% of GDP |

60.9 |

56.5 |

62.9 |

74.8 |

.. |

|

Net FDI |

% of GDP |

7.7 |

6.3 |

6.9 |

7.1 |

.. |

|

Public and publicly guaranteed debt |

% of GDP |

52.7 |

57.8 |

57.1 |

55.6 |

55.4 |

|

External debt |

% of GDP |

61.4 |

65.8 |

68.4 |

69.3 |

.. |

|

Unemployment |

% of total active population |

11.2 |

9.7 |

11 |

9.4 |

.. |

|

Youth unemployment |

% of total |

27.5 |

26.6 |

25.5 |

24.3 |

.. |

|

International reserves |

In months of imports of G&S |

5.7 |

6.1 |

5.9 |

5.2 |

.. |

|

Exchange rate (if applicable local currency/euro) |

Value |

117.86 |

117.58 |

117.57 |

117.46 |

117.25 |

|

Remittance inflows |

% of GDP |

… |

4.5 |

4.7 |

7.1 |

6.1 |

|

Lending interest rate |

% annual average |

2.52 |

1.19 |

0.89 |

2.47 |

.. |

|

Stock markets (if applicable) |

Average index |

1 584 |

1 544 |

1 639 |

1 720 |

.. |

Note: G&S = goods and services. “…” indicates data are collected but not available.

Sources: European Commission (2024[5]); World Bank (2021[2]).; EBRD (2023[13]); IMF (2024[14]); UNCTAD (2024[15]).

Serbia’s financial sector has remained steady, while tighter financing conditions led to decreased demand for private credit. Lending growth turned negative in 2023, at -0.4% (European Commission, 2024[5]). Nonperforming loans have continued their declining trend and reached 3.0% in 2023 as a percentage of total loans (see Chapter 4 for more details on the financial sector).

Box 1.1. Economic impacts of Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine on Serbia’s economy

Russia’s ongoing invasion of Ukraine had muted negative economic implications for Serbia, mostly as a result of increased commodity prices. As Serbia has not aligned itself with the EU’s sanctions on Russia, its trade and investment links with Russia remained less affected compared with other economies of the Western Balkans. Moreover, there is evidence that the inflow of Russian citizens contributed to the robust growth of the information and communication technology (ICT) sector, whose exports reached EUR 1.3 billion in mid-2023, 41% more than a year earlier.

Trade volumes between Serbia and Russia have steadily increased, rising nearly threefold over 2012-22. From 2021 to 2022 alone, exports from Russia to Serbia increased from EUR 1.5 billion to EUR 2.6 billion (United Nations, 2024[16]). In 2023, Russia accounted for around 4% of Serbia’s total exports and 5.3% of its imports (United Nations, 2024[16]). The main products exported from Russia to Serbia were crude petroleum, petroleum gas, and nitrogenous fertilisers. Serbia’s exports to Russia likewise increased, from EUR 842 million in 2021 to EUR 1 billion in 2023 (United Nations, 2024[16]).

Meanwhile, Serbia’s trade relations with Ukraine, which represent less than 0.1% of its total trade value, have declined even further since the start of the conflict. In 2022, Serbia’s exports to Ukraine totalled EUR 126 million, down from EUR 152 million in 2021 (United Nations, 2024[16]). Serbia’s exports to Ukraine remained constant into 2023, at EUR 150 million. Likewise, Ukraine’s exports to Serbia, which totalled EUR 165 million during 2021, dropped to EUR 114 million in 2022 and remained steady into 2023 at EUR 110 million (United Nations, 2024[16]).

Serbia’s energy sector has also been affected, and the economy has taken steps to balance its energy needs. Prior to the conflict, Serbia had been almost entirely dependent on Russian imports of natural gas and the Russia’s Gazprom had a sizable control over the economy’s energy assets (Stojanovic, 2022[17]; EWB, 2023[18]). In 2023, it signed a deal to purchase 400 million cubic metres of natural gas from Azerbaijan from 2024, representing approximately 13% of its natural gas needs. The Serbia‑Bulgaria gas interconnector, a flagship project of the EU’s Economic and Investment Plan for the Western Balkans, was completed in December 2023. The pipeline has a transmission capacity of 1.8 billion cubic metres per year (European Commission, 2023[19]). At the same time, Serbia renewed its energy deal with Russia for another three years as of May 2022, and established a joint company with Hungary in June 2022 to route Russian gas to the EU Member State. In response to the social and economic impact of the current energy crisis generated by Russian war of aggression against Ukraine, the EU allocated EUR 165 million to Serbia under the 2023 Energy Support Package immediate measures, 90% of which has been disbursed to assist vulnerable families and SMEs in dealing with rising energy prices. The actions are also aimed at supporting policy measures to accelerate the energy transition (European Commission, 2023[20]).

In terms of agricultural products, the government introduced in March 2022 a five-month ban on the export of some agricultural products with the objective to offset rising food prices and address shortages from Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine. However, the European Commission states that this measure is incompatible with the EU‑Serbia Stabilisation and Association Agreement. The measure included a ban of wheat, maise, wheat flour, groats and sunflower oil. Serbia’s grain exports, 80% of which are routed through Black Sea ports, have lowered significantly due to rising domestic prices, government limitations in exports and lower domestic production (US Department of Agriculture, 2023[21]). The value of Serbia’s global cereal exports plunged from USD 908 million in 2021 to USD 474 million in 2023 (United Nations, 2024[16]).

The spillovers from the war also triggered a temporary shock to financial stability, with temporary cash withdrawals from the banking system that peaked in the first two weeks of March 2022 (IMF, 2022[22]). Serbian authorities took quick action to mitigate the shocks, emphasising that the exchange rate would be kept stable through the crisis, and that any withdrawal requests would be honoured.

Source: United Nations (2024[16]).

Sustainable development

Serbia shows a moderate level of success in progressing towards the targets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (Sachs et al., 2023[23]). As of 2023, Serbia had achieved or is on track to achieve 53.6% of its target indicators. The economy has made limited progress in 24.6% of indicators, while performance is worsening across 21.7% of trend indicators. Integration of the SDG Agenda into Serbia’s national policy practices has further room to improve. The SDGs have been officially endorsed and mainstreamed into Serbia’s national and sectoral plans. However, there is no designated lead unit responsible for the co-ordination and implementation of the SDGs across ministries; the Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia assumes the responsibility of monitoring them (Sachs et al., 2023[23]). The Statistical Office makes available indicators and pertinent data on SDG progress on a quarterly basis via a dedicated website for SDG monitoring and an open data platform (UN-Habitat, 2023[24]). The first and only Voluntary National Review providing a comprehensive overview of the economy’s progress toward achieving the SDGs took place in 2019 (UN-Habitat, 2023[24]).

Serbia has achieved or has maintained the achievement of SDGs in only one area – poverty reduction (SDG 1). Serbia nears achievement in the areas of quality education (SDG 4) and partnerships for the goals (SDG 17) but it has fallen behind since 2021 on its SDG attainment for education (SDG 4). Performance likewise decreased in the areas of affordable and clean energy (SDG 7) and climate action (SDG 13). The declining performance in these areas is mostly attributable to the increase in carbon intensity (CO2 emissions) of energy production and exports, respectively.

Serbia is progressing in the areas of clean water and sanitation (SDG 6) and reduced inequalities (SDG 10), with further room to improve. While access to basic sanitation services has increased across the population, wastewater treatment rates remain low. Meanwhile, the Gini coefficient for inequality remains relatively high but has been on a declining trend since 2015, reaching 34.5% in 2020 and nearing the target value of 27.5% (Sachs et al., 2023[23]).

Table 1.2. Serbia’s progress towards achieving the Sustainable Development Goals

|

SDG |

Current assessment |

Trends |

|---|---|---|

|

1 – No poverty |

SDG achieved |

Stagnating |

|

2 – Zero hunger |

Significant challenges |

Moderately improving |

|

3 – Good health and well-being |

Significant challenges |

Moderately improving |

|

4 – Quality education |

Challenges remain |

Stagnating |

|

5 – Gender equality |

Significant challenges |

Moderately improving |

|

6 – Clean water and sanitation |

Significant challenges |

On track or maintaining SDG achievement |

|

7 – Affordable and clean energy |

Significant challenges |

Moderately improving |

|

8 – Decent work and economic growth |

Significant challenges |

Moderately improving |

|

9 – Industry, innovation and infrastructure |

Significant challenges |

Moderately improving |

|

10 – Reduced inequalities |

Significant challenges |

On track or maintaining SDG achievement |

|

11 – Sustainable cities and communities |

Significant challenges |

Moderately improving |

|

12 – Responsible consumption and production |

Significant challenges |

Moderately improving |

|

13 – Climate action |

Significant challenges |

Stagnating |

|

14 – Life below water |

Information unavailable |

Trend information unavailable |

|

15 – Life on land |

Major challenges |

Moderately improving |

|

16 – Peace, justice and strong institutions |

Major challenges |

Stagnating |

|

17 – Partnerships for the goals |

Challenges remain |

Moderately improving |

Note: The order of progress (from greatest to least) is as follows: SDG achieved; challenges remain; significant challenges; major challenges.

Source: Sachs et al. (2023[23]).

Moderate progress has also been made in the areas of health and well-being (SDG 3); economic growth (SDG 8); industry, innovation and infrastructure (SDG 9); sustainable urban development (SDG 11); and responsible production and consumption (SDG 12). The most significant gaps remain in the areas of protection of terrestrial ecosystems (SDG 15) and institutional integrity (SDG 16). Protection of terrestrial ecosystems remains hindered due to low rates of protected terrestrial and freshwater sites important to biodiversity. Impediments to progress in SDG 16 lie in persistent corruption, continuance of unlawful expropriation practices, poor timeliness of administrative proceedings, and declining performance in press freedom. Being a landlocked economy, no data are available for the area of marine life (SDG 14) (Sachs et al., 2023[23]).

EU accession developments

Serbia’s EU integration process began in 2008 when it signed its Stabilisation and Association Agreement (SAA) with the EU. It then formally submitted its application for EU membership in December 2009. In March 2012, Serbia was granted official candidate status for EU membership, and accession negotiations formally began in January 2014, when the negotiating framework with Serbia was presented at the first Intergovernmental Conference. At the time of writing, Serbia had opened 22 out of 35 negotiating chapters and provisionally closed two. These are Chapter 25 on Science and Research and Chapter 26 on Education and Culture.

In February 2020, the Commission presented an enhanced enlargement methodology to the accession negotiations, which Serbia officially accepted at the Intergovernmental Conference held in June 2021. The revised methodology emphasises credible fundamental reforms, stronger political direction, and increased dynamism and predictability of the process (European Commission, 2021[25]). The negotiating framework includes the new approach to negotiations concerning judiciary and fundamental rights, as well as justice, freedom, and security, along with the normalisation of relations between Serbia and Kosovo (European Commission, 2021[25]).

According to the EU’s 2023 enlargement report, Serbia shows some level of preparation in relation to the political criteria for accession (European Commission, 2023[26]). Serbia shows a moderate level of preparation around public administration reform and has made limited progress in this area – particularly by strengthening e-governance services and capabilities – though it still lacks key mechanisms in policy co-ordination and public financial management. Regarding its judicial system, Serbia has a modest level of preparation and has made important progress towards strengthening the independence and accountability of the judiciary. Further efforts are needed in the electoral framework, co‑operation between the government and civil society, corruption, organised crime, and freedom of expression. In the area of foreign, security and defence policy, no progress has been made over the period; alignment patterns remained unchanged and some of Serbia’s actions and statements went against EU positions on foreign policy (European Commission, 2023[20]). Regarding the normalisation of relations with Kosovo, in February 2023 under the auspices of EU facilitation, both Serbia and Kosovo expressed readiness to proceed with the implementation of the EU Proposal “Agreement on the Path to Normalisation between Kosovo and Serbia” (EEAS, 2023[27]). However, neither Serbia nor Kosovo has started the implementation of their respective obligations and negative developments have hampered the progress (European Commission, 2023[28]).

Regarding economic criteria, Serbia has shown solid progress towards developing a functioning market economy and has made some progress towards coping with competitive pressure within the EU (European Commission, 2023[20]). Serbia’s Economic Reform Programme has propelled progress in competitiveness and inclusive growth by facilitating further alignment of legislation with the EU acquis (European Commission, 2023[26]). Serbia has successfully attracted significant FDI in recent years, securing more than half of the investments allocated to its Western Balkan neighbours -its strong performance is directly linked to its progress towards integrating into the EU market, and further progress on the EU accession path is poised to further boost FDI levels. While economic integration with the EU remains high, progress has been limited in most areas regarding preparation for the requirements of the EU internal market particularly those for resources, agriculture, and cohesion, and no progress was registered in the area of free movement of capital (European Commission, 2023[20]). Further efforts are also needed towards reducing the state's role in the economy and improving the governance of state-owned administrations, as well as to ensure proper implementation of public investment management, public procurement and state-aid procedures to increase transparency, cost effectiveness and fair competition.

On 8 November 2023, the European Commission adopted a new Growth Plan for the Western Balkans to improve the level and speed of convergence between the Western Balkans and the EU (European Commission, 2023[29]). Backed by EUR 6 billion in non-repayable support and loan support, the Growth Plan has the potential to boost socio-economic convergence and bring WB6 closer to the EU single market (Gomez Ortiz, Zarate Vasquez and Taglioni, 2023[30]; European Commission, 2023[29]). The new Growth Plan is based on four pillars, aimed at:

1. “Enhancing economic integration with the European Union’s single market, subject to the Western Balkans aligning with single market rules and opening the relevant sectors and areas to all their neighbours at the same time, in line with the Common Regional Market.

2. Boosting economic integration within the Western Balkans through the Common Regional Market.

3. Accelerating fundamental reforms, including on the fundamentals cluster2, supporting the Western Balkans' path towards EU membership, improving sustainable economic growth including through attracting foreign investments and strengthening regional stability.

4. Increasing financial assistance to support the reforms through a Reform and Growth Facility for the Western Balkans” (European Commission, 2023[29]).

The new Growth Plan builds on the existing enlargement methodology and creates a package of mutually reinforcing measures. The aim is to speed up accession negotiations by providing incentives to economies to accelerate the adoption and implementation of the EU acquis, while narrowing the gap between the Western Balkans and EU Member States. In that context, the OECD has recently released the Economic Convergence Scoreboard for the Western Balkans 2023 to track the region’s performance in achieving economic convergence towards the EU and the OECD area, and to highlight policy bottlenecks that hinder faster economic growth in a sustainable and inclusive way (OECD, 2023[31]) (Box 1.2).

As part of the new Growth Plan, the Western Balkans have been asked to submit to the European Commission economy-specific Reform Agendas listing several structural reforms that would need to be implemented in order to access part of the Plan’s funding. All Reform Agendas are structured along the same four policy areas: 1) business environment and private sector development, 2) green and digital transformation, 3) human capital development and 4) fundamentals (of the EU accession process). They replace Economic Reform Programmes’ chapter IV on structural challenges, as, going forward, the Economic Reform Programmes will only cover macrofiscal aspects.

Box 1.2. Economic Convergence Scoreboard for the Western Balkans 2023: Spotlight on Serbia

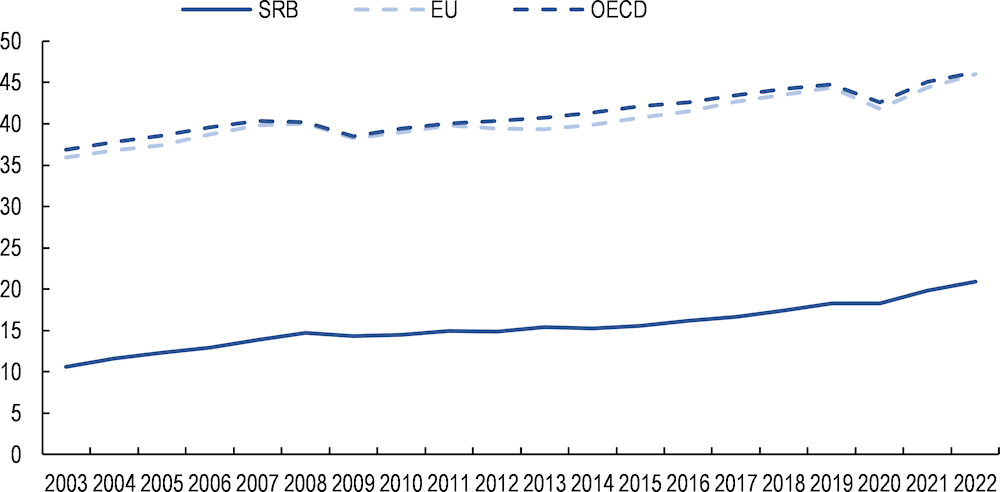

Serbia’s GDP per capita doubled from 2003 to 2022, contrasting with the EU and the OECD area’s increases of 27% and 25%, respectively. This growth has helped narrow the economic gap, halving the percentage difference in GDP per capita between Serbia and the EU-OECD averages. However, with Serbia's 2022 GDP per capita at USD (PPP international $) 20 885 (EUR 19 8401) – less than half of the EU's USD 45 978 (EUR 43 679) and the OECD area’s USD 46 208 (EUR 43 897) – the economy faces continued challenges in achieving economic convergence. These trends highlight the complexities of convergence and the need for comprehensive policy development to foster a productive and competitive workforce.

Figure 1.1. Serbia’s GDP per capita convergence with the OECD area and the European Union (2003-2022)

In Purchasing Power Parity 2017 USD (thousands)

In this context, the OECD developed the Economic Convergence Scoreboard for the first time in 2023, marking the establishment of a recurring assessment mechanism and dedicated tool designed to evaluate the extent of economic convergence of the Western Balkans with the European Union and the OECD area. Prepared to inform discussions at the Berlin Process Western Balkans Leaders’ Summit 2023 and grounded in a decade-long series of policy assessments, the Scoreboard offers a thorough analysis of the region's progress across five key policy areas, or clusters, crucial for attaining sustainable and inclusive economic growth. These clusters are business environment, skills, infrastructure and connectivity, greening, and digital transformation.

Since 2008, Serbia achieved noteworthy advances across the five policy clusters, underscoring not only the adoption of policies in alignment with EU acquis and OECD standards but also the effective implementation of these policies. In the business environment cluster, Serbia made notable progress, particularly in attracting foreign direct investment (FDI). Between 2018 and 2022, Serbia's net inflows of FDI as a percentage of its GDP consistently outperformed fourfold those of the EU. Additionally, Serbia has made positive strides in digitalisation. For instance, the adoption of digital payment methods among the population has seen a significant increase, moving from 77% of the EU's level of performance in the period from 2013 to 2017 to nearly achieving parity with the EU by 2022.

By contrast, the skills and greening clusters necessitate further attention. Foremost, Serbia’s output per hour worked hovers around one-third of the EU performance and has consistently regressed – this partially points to a relatively unproductive labour force, lacking the skills needed for a competitive economy. As for greening, renewable energy consumption and waste generation – areas where Serbia had previously excelled compared to the EU – have seen substantial declines vis-à-vis the EU performance over the observed periods (2008-2012; 2013-2017; and 2018-2022), decreasing by 22% and 79%, respectively. Moreover, CO2 emissions are greater than those of the EU but are slowly declining. These trends underscore a need for prioritising and reinforcing green policies, as Serbia’s broader convergence efforts are not fully integrated with sustainable practices.

In the context of aligning with OECD good practices and standards, Serbia has demonstrated overall progress, albeit with setbacks in the areas OECD Services Trade Restrictiveness Index and Digital Services Trade Restrictiveness Index, and Competitiveness Outlook (CO) anti-corruption and agriculture policies. Notably, advances have been made in CO access to finance, transport and science, technology and innovation policies, with Serbia nearing convergence with the OECD area relating to these policies.

1. The 2022 market exchange rate has been used to convert PPP constant 2017 international dollars into EUR.

Source: OECD (2023[31]).

EU financial and development support

Since embarking upon its EU accession journey, Serbia has received significant financial assistance from the EU for socio-economic development and fundamental reforms, through both temporary support packages and long-term investment programmes. Funding to Serbia has been facilitated mainly through the Instrument for Pre-accession Assistance (IPA), European Investment Bank loans, and Western Balkans Investment Framework grants.

Over 2007-13, the EU’s financial support to Serbia through the Instrument for Pre-accession Assistance (IPA I) has amounted to approximately EUR 170 million per year (European Court of Auditors, 2014[34]). The total allocation under IPA II (2014-20) amounted to EUR 1.54 billion for Serbia and introduced priority sectors for assistance (European Commission, 2024[35]). Priority sectors covered under the period included democracy and governance, rule of law and fundamental rights, environment and climate action, transport, energy, competitiveness and innovation, education, employment and social policies, and agriculture and rural development.

For 2021-23, IPA III funding for Serbia’s national programmes amounted to EUR 571 million. This includes the dedicated EUR 165 million from the 2023 Energy Support Package immediate measures, which have been almost entirely disbursed toward assistance to vulnerable families and SMEs in dealing with rising energy prices (European Commission, 2023[20]). The actions are also aimed at supporting policy measures to accelerate the energy transition. Additionally, the Economic and Investment Plan for the Western Balkans 2021-27, which has already mobilised EUR 5.7 billion in investments for Serbia (of which EUR 1.1 billion is in the form of grants), has set out flagship investments for the economy in the areas of sustainable transport, clean energy, environment and climate, digital infrastructure and human capital.

References

[13] EBRD (2023), Transition Report 2023-24, https://www.ebrd.com/news/publications/transition-report/transition-report-202324.html (accessed on 12 April 2024).

[27] EEAS (2023), Belgrade-Pristina Dialogue: Agreement on the path to normalisation between Kosovo and Serbia, Brussels, https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/belgrade-pristina-dialogue-agreement-path-normalisation-between-kosovo-and-serbia_en (accessed on 15 March 2024).

[5] European Commission (2024), EU Candidate Countries’ & Potential Candidates’ Economic Quarterly, https://economy-finance.ec.europa.eu/document/download/00bb7307-1694-4c7e-99de-5c3e662b2172_en?filename=tp070_en.pdf.

[35] European Commission (2024), Serbia - Financial Assistance under IPA, Brussels: Directorate-General for Neighbourhood and Enlargement Negotiations, https://neighbourhood-enlargement.ec.europa.eu/enlargement-policy/overview-instrument-pre-accession-assistance/serbia-financial-assistance-under-ipa_en (accessed on 23 April 2024).

[29] European Commission (2023), Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, The Council, The European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: New growth plan for the Western Balkan, https://neighbourhood-enlargement.ec.europa.eu/document/download/8f5dbe63-e951-4180-9c32-298cae022d03_en?filename=COM_2023_691_New%20Growth%20Plan%20Western%20Balkans.pdf.

[19] European Commission (2023), Gas Interconnection Bulgaria-Serbia (IBS) - Construction Works, https://ec.europa.eu/assets/cinea/project_fiches/cef/cef_energy/6.8.3-0013-BG-W-M-20.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2024).

[20] European Commission (2023), Serbia 2023 Enlargement Package Factsheet, Directorate-General for Neighbourhood and Enlargement Negotiations, Brussels, https://neighbourhood-enlargement.ec.europa.eu/serbia-2023-enlargement-package-factsheet_en (accessed on 18 March 2024).

[26] European Commission (2023), Serbia 2023 Report, Directorate-General for Neighbourhood and Enlargement Negotiations, Brussels, https://neighbourhood-enlargement.ec.europa.eu/document/download/9198cd1a-c8c9-4973-90ac-b6ba6bd72b53_en?filename=SWD_2023_695_Ser.

[28] European Commission (2023), Serbia 2023 Report Accompanying the document Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions 2023 Communication on EU Enlargement, https://neighbourhood-enlargement.ec.europa.eu/document/download/9198cd1a-c8c9-4973-90ac-b6ba6bd72b53_en?filename=SWD_2023_695_Serbia.pdf (accessed on 28 May 2024).

[25] European Commission (2021), “Application of the revised enlargement methodology to the accession negotiations with Montenegro and Serbia, 06/05/2021”, https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-8536-2021-INIT/en/pdf (accessed on 18 March 2024).

[34] European Court of Auditors (2014), Special Report No. 19: EU Pre accession Assistance to Serbia, https://www.eca.europa.eu/lists/ecadocuments/sr14_19/qjab14019enn.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2024).

[18] EWB (2023), “Serbia’s Energy Dilemma: Between Russian ownership and the path to renewable transition”, https://europeanwesternbalkans.com/2023/11/10/serbias-energy-dilemma-between-russian-ownership-and-the-path-to-renewable-transition/ (accessed on 14 May 2024).

[30] Gomez Ortiz, M., R. Zarate Vasquez and D. Taglioni (2023), “The economic effects of market integration in the Western Balkans”, Policy Research Working Paper Series, No. 10491, World Bank, Washington, DC, https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-10491 (accessed on 8 April 2024).

[3] ILO (2024), ILO Modelled Estimates Database, https://ilostat.ilo.org/ (accessed on 5 March 2024).

[4] ILO (2023), Overview of the Informal Economy of Serbia, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---europe/---ro-geneva/---sro-budapest/documents/genericdocument/wcms_751317.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2024).

[1] IMF (2024), Datamapper, GDP, Current Prices, https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/profile/SRB (accessed on 16 March 2024).

[8] IMF (2024), Datamapper: Inflation Rate, Average Consumer Prices, https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/PCPIPCH@WEO/SRB?zoom=SRB&highlight=SRB (accessed on 5 March 2024).

[14] IMF (2024), International Financial Statistics, https://data.imf.org/regular.aspx?key=61545855 (accessed on 8 April 2024).

[6] IMF (2024), Real GDP growth: Annual Percent Change, https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDP_RPCH@WEO/SRB?zoom=SRB&highlight=SRB (accessed on 1 March 2024).

[10] IMF (2023), Republic of Serbia: 2023 Article IV Consultation, First Review Under the Stand-By Arrangement, and Request for Modification of Performance Criteria-Press Release; Staff Report; and Statement by the Executive Director for Republic of Serbia, https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/journals/002/2023/243/article-A001-en.xml (accessed on 22 April 2024).

[22] IMF (2022), Second Review under the Policy Coordination Instrument and Request for Modification of Targets, press release, staff report and statement by the Executive Director for the Republic of Serbia, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2022/06/29/Republic-of-Serbia-Second-Review-Under-the-Policy-Coordination-Instrument-and-Request-for-520142.

[11] National Bank of Serbia (2024), The Issuance of the First Green Bond of the Republic of Serbia, https://www.ubs-asb.com/files/Green%20Bond.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2024).

[31] OECD (2023), Economic Convergence Scoreboard for the Western Balkans 2023, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/regions/grc/see/economic-convergence-scoreboard-for-the-western-balkans-2023.pdf/_jcr_content/renditions/original./economic-convergence-scoreboard-for-the-western-balkans-2023.pdf.

[33] OECD (2014), OECD Economic Outlook No. 95 (Edition 2014/1), https://doi.org/10.1787/data-00688-en (accessed on 14 May 2024).

[23] Sachs, J. et al. (2023), Implementing the SDG Stimulus. Sustainable Development Report 2023, Dublin University Press, Dublin, https://doi.org/10.25546/102924.

[12] Scope Ratings (2022), “Scope assigns Serbia first-time sovereign rating of BB+ with Stable Outlook”, https://www.scoperatings.com/ratings-and-research/rating/EN/171288 (accessed on 19 March 2024).

[9] Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia (2024), Earnings, https://www.stat.gov.rs/en-US/oblasti/trziste-rada/zarade (accessed on 5 March 2024).

[17] Stojanovic, M. (2022), “Serbia mulls ‘taking over’ mainly Russian-owned oil company”, Balkan Insight, https://balkaninsight.com/2022/07/14/serbia-mulls-taking-over-mainly-russian-owned-oil-company/ (accessed on 14 May 2024).

[15] UNCTAD (2024), Data Centre, https://unctadstat.unctad.org/datacentre/ (accessed on 8 April 2024).

[24] UN-Habitat (2023), Progress in Monitoring SDG Indicators in the Field of Sustainable Urban Development in the Republic of Serbia, https://serbia.un.org/en/259101-.

[16] United Nations (2024), UN Comtrade Database, (accessed on 16 March 2024)., https://comtradeplus.un.org/ (accessed on 16 March 2024).

[21] US Department of Agriculture (2023), Serbia: Grain and Feed Annual, Office of Agricultural Affairs, Belgrade, https://fas.usda.gov/data/serbia-grain-and-feed-annual-8.

[36] World Bank (2023), World Bank Western Balkans Regular Economic Report, World Bank, https://www.worldbank.org/en/region/eca/publication/western-balkans-regular-economic-report (accessed on 8 April 2024).

[32] World Bank (2022), GDP per Capita, PPP (Constant 2017 International $), https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.KD (accessed on 1 March 2024).

[2] World Bank (2021), World Development Indicators, https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed on 8 April 2024).

[7] World Bank (2020), Serbia’s New Growth Agenda, https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/782101580729358303-0080022020/original/SerbiaCEMSynthesisweb.pdf.

Notes

← 1. According to the World Bank’s report, Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) includes Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania and the Slovak Republic.

← 2. In line with Communication on “Enhancing the accession process – A credible EU perspective for the Western Balkans” COM(2020)57, the fundamentals cluster includes: chapter 23 – Judiciary and Fundamental Rights, chapter 24 – Justice, Freedom and Security, the economic criteria, the functioning of democratic institutions, public administration reform, chapter 5 – Public procurement, chapter 18 – Statistics and chapter 32 – Financial control (European Commission, 2023[29]).