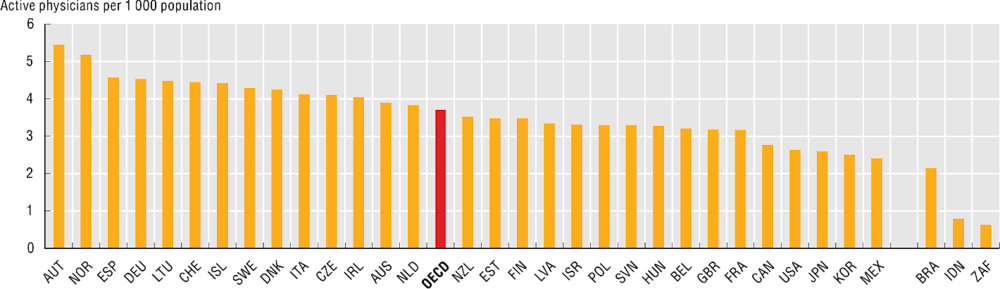

Although most OECD countries have achieved universal (or near universal) coverage for a core set of health services, including consultations with doctors and hospital care, issues of affordability and accessibility still hinder the use of health services. Access to medical care requires enough doctors, equitably distributed across the country. An under-supply of doctors can lead to longer waiting times or patients having to travel far to access services (OECD, 2021). The number of doctors per person varies substantially across OECD countries. On average, in 2021, there were almost 4 active physicians per 1 000 people across 30 OECD countries with comparable data. This ranged from just over 2.5 per 1 000 in Mexico, Korea, Japan and the United States to over 5 per 1 000 in Austria and Norway (Figure 3.10).

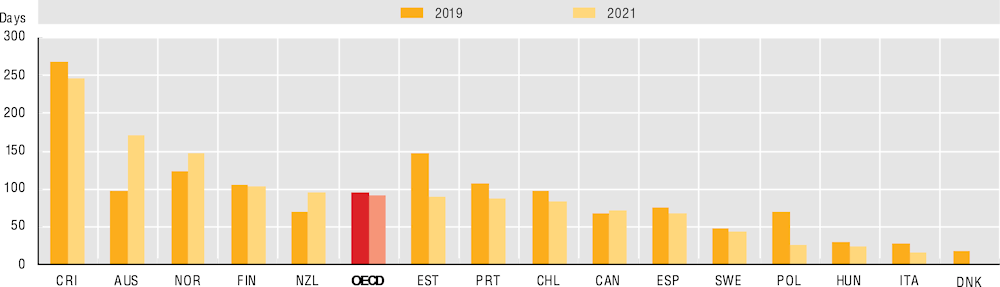

Waiting time is one measure of the timeliness of service delivery. Excessive waiting times can affect both perceptions of quality and the effectiveness of healthcare services. In 2021, the median waiting time for cataract surgery (one of the most frequent surgical interventions in OECD countries) was nearly three months (86 days). Waits were shortest in Italy (16 days), Hungary (25 days) and Poland (36 days), and longest in Costa Rica (247 days) and Australia (172 days) (Figure 3.11). Across OECD countries, waiting times had decreased by an average of 4 days in 2021 compared to before the pandemic, reflecting concerted policy efforts to address backlogs caused by the disruption of services. Nevertheless, four countries saw an increase in waits for cataract surgery: Australia (+74 days), New Zealand (+25 days), Norway (+23 days) and Canada (+5 days).

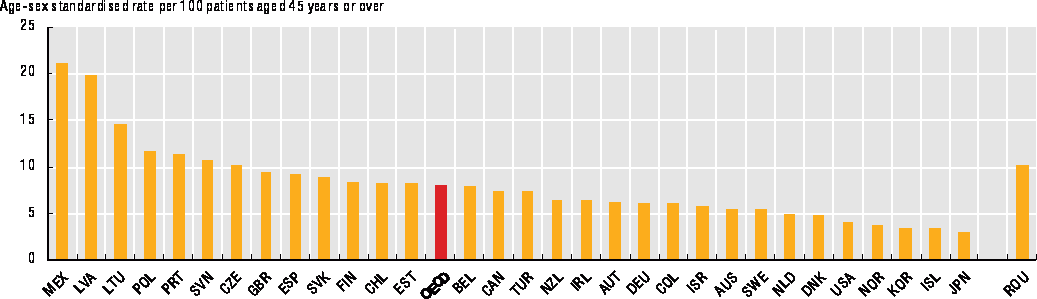

Healthcare providers must deal with various health problems daily, including infectious, chronic and life-threatening diseases and injuries. Some of the most frequent and severe health problems in OECD countries are cardiovascular diseases (including heart attacks and strokes) and various types of cancer. These are, by far, the two main causes of death in OECD countries, with cardiovascular diseases accounting for about one-third of all deaths and cancers for about one-quarter. While cardiovascular disease and cancer can be reduced through greater prevention efforts (e.g. reductions in tobacco and alcohol use and better eating habits), early detection is also critical, as is providing effective and timely treatments when they are diagnosed. A good indicator of the quality of acute care is the 30-day case-fatality rate after someone is admitted to hospital for an ischaemic stroke. This measure reflects the care processes, such as timely transport to hospital and effective medical interventions (OECD, 2015). Indeed, countries with lower 30-day mortality rates for ischaemic stroke also had lower 30-day mortality rates for acute myocardial infarction, suggesting some characteristics of acute care delivery are relevant across a range of acute illnesses (OECD/European Union, 2022). On average across the OECD, in 2020, the age-standardised mortality rate after hospital admission for ischaemic stroke was 8.1 per 100 admissions in people aged 45 and over. The lowest rates were in Japan (3.0) and Iceland (3.4) among OECD countries, whereas Mexico (21.1) had the highest (Figure 3.12).