Preventing and managing conflicts of interest in the public sector is crucial to help governments strengthen and enhance public integrity. Left undetected or inappropriately managed, they can undermine the integrity of public officials, decisions, agencies and governments. If they are left unresolved, they can lead to corruption, as the private interests of public officials may improperly influence the decision-making process, and ultimately allow to be captured by private interests.

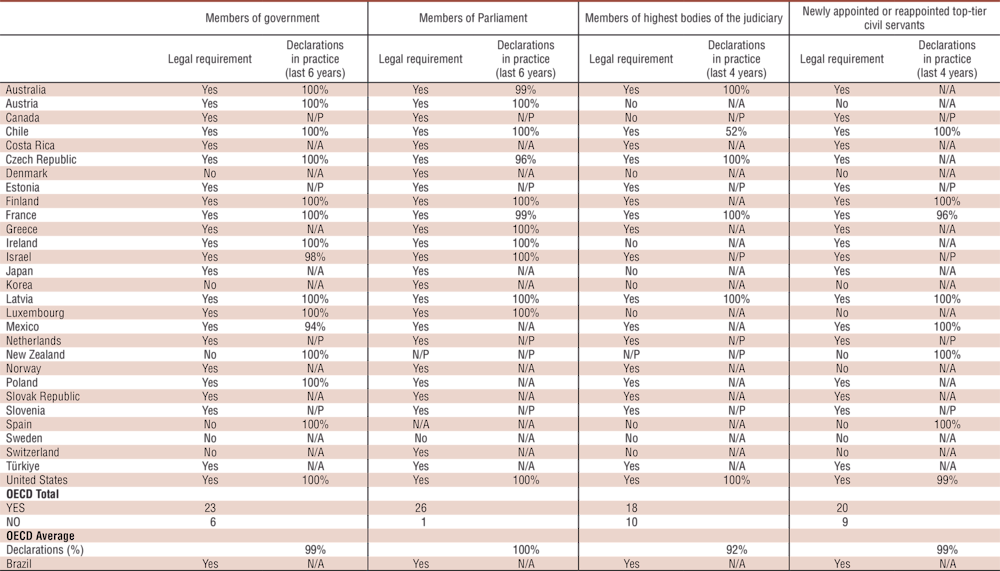

Transparency, openness and oversight of revolving door practices are key instruments for reducing conflicts of interest. OECD countries also adopt more targeted measures to manage conflict of interest, such as requiring public officials to disclose their private financial interests and assets, ensuring that these are verified and applying sanctions in the case of non-compliance. Ministers are legally required to disclose their private interests upon entry and any change or renewal in public office in 23 out of 26 surveyed OECD countries (88%), and members of parliament in 26 countries. Top-tier senior civil servants of the executive (first level below the minister) are required to disclose their interests in 20 out of 29 countries (69%), and members of the highest bodies of the judiciary in 18 out of 29 countries (62%). Disclosure of private interests is required across all three branches of government in 17 OECD countries (Table 4.4).

At the same time, many OECD countries lack statistics on the actual implementation of the legal requirements. In practice, the countries with a system in place to oversee compliance with regulatory requirements, and which provided the data, generally perform well. All ministers and MPs submitted their interest declarations during the past six years in Austria, Chile, Finland, Ireland, Latvia, Luxembourg and the United States, and over 95% did so in Australia, the Czech Republic France and Israel. All senior members of the judiciary disclosed their interests in Australia, the Czech Republic, France, Latvia and the United States. Over 95% of top-tier senior civil servants of the executive branch (first level below the minister) provided interest declarations in Chile, Finland, France, Latvia, Mexico, New Zealand, Spain and the United States (Table 4.4).

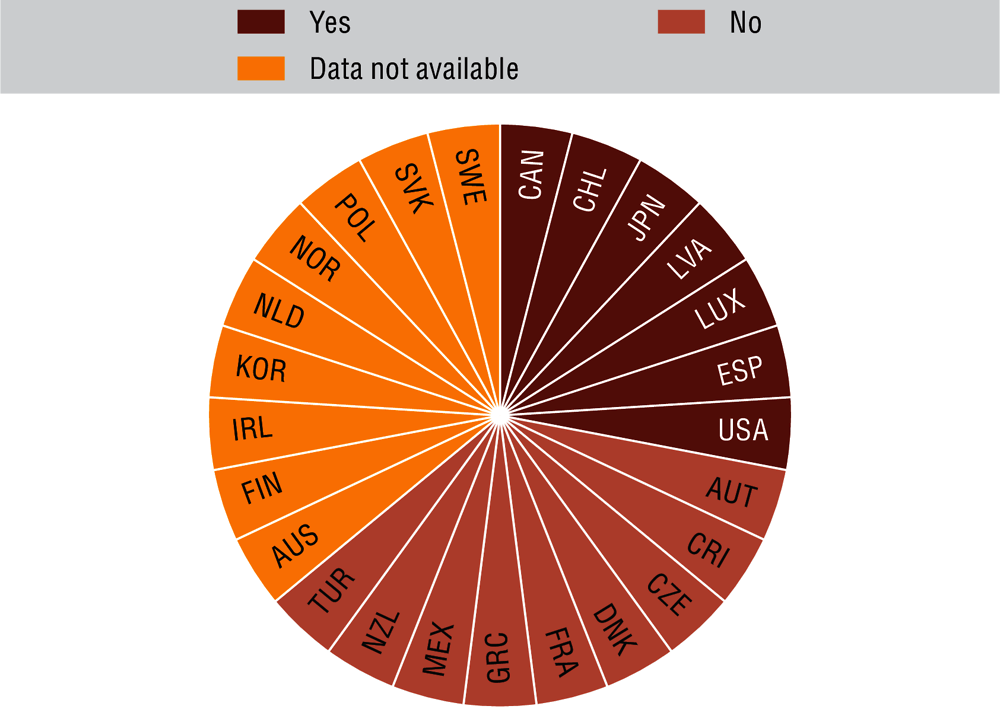

Verifying the content of private interest declarations can strengthen compliance. Of the 27 OECD countries surveyed, only in Canada, Chile, Japan, Luxembourg, Spain and the United States has the responsible authority verified over 60% of declarations filed over the last two years. In eight countries, the rate is below 60%, and in the remaining nine the data are not available (Figure 4.5).

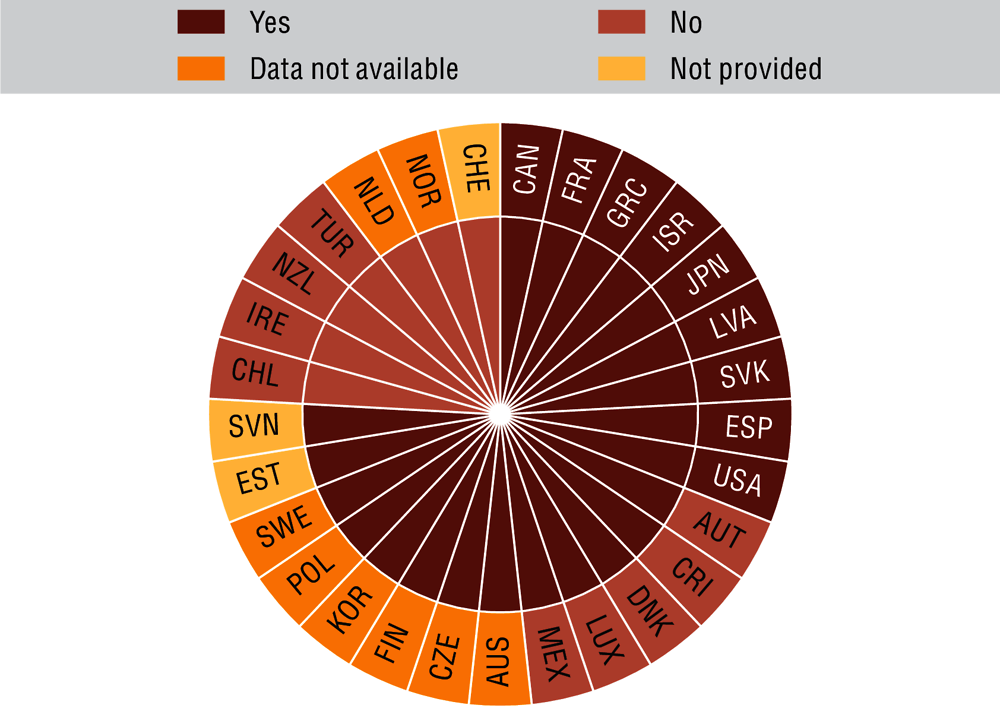

Enforcing conflict-of-interest requirements is vitally important to deterring non-compliance and ensuring the legitimacy of and trust in integrity systems. Out of 29 OECD countries surveyed, 22 (76%) have defined sanctions in the regulatory framework for breaching conflict-of-interest provisions. In practice, nine of these have issued sanctions in the past three years for non-compliance with disclosure obligations, non-management or non-resolution of a conflict-of-interest situation (Figure 4.6).