In addition to supporting economic efficiency, public procurement can help achieve other strategic objectives such as the green transition. Governments across the OECD are increasingly focusing on sustainability and using their purchasing power to steer their economies towards greater consideration of environmental choices and outcomes. By taking a whole life cycle approach to the purchase of goods, services and works, governments can make an important contribution to protecting the environment and tackling climate change.

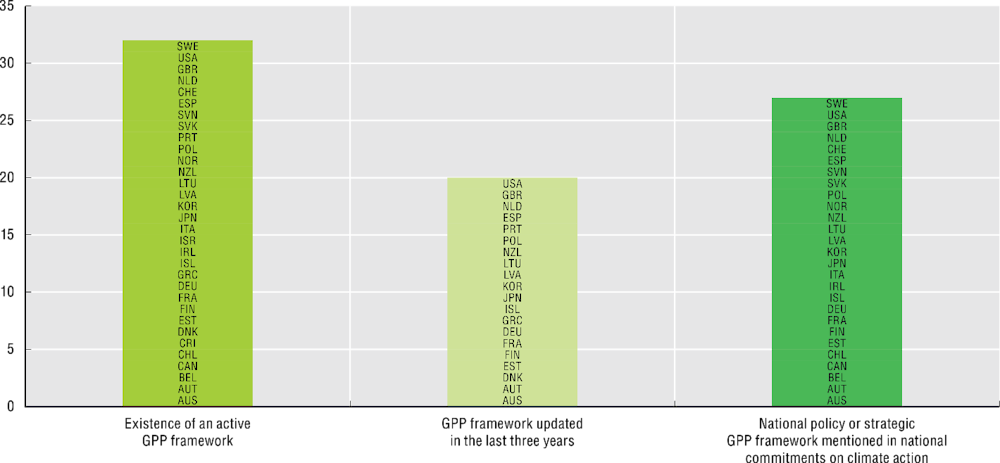

Countries have been developing green public procurement (GPP) strategies and policies for more than a decade, and their adoption has substantially increased since the definition of Agenda 2030 and the Sustainable Development Goals. In 32 out of 34 OECD countries surveyed (94%) there is an active national GPP policy or framework, suggesting that GPP is widely recognised as a powerful tool to achieve the climate action goals countries have endorsed (Figure 7.3).

Indeed, 28 out of the 32 countries with a GPP policy or framework (88%) clearly refer to GPP or public procurement in national commitments on climate action and consider this government function as integral to achieving their environmental commitments. Japan mentions the national policy on GPP in its Plan for Global Warming Countermeasures and National Action Plan, and Canada cites GPP as a means to achieve net zero emissions by 2050.

To ensure alignment with global commitments on climate action, OECD countries regularly revise their GPP policies. In fact, almost two-thirds (20 out of 32, or 63%) of countries with a GPP framework have updated it in the past three years to target high-impact sectors and to move towards cleaner products more rapidly (Figure 7.3). For example, in 2021, the United Kingdom enacted a Procurement Policy Note that introduces a new selection criterion for major government contracts, excluding suppliers from the procurement process if they have failed to produce a carbon reduction plan and committed to net zero emissions by 2050.

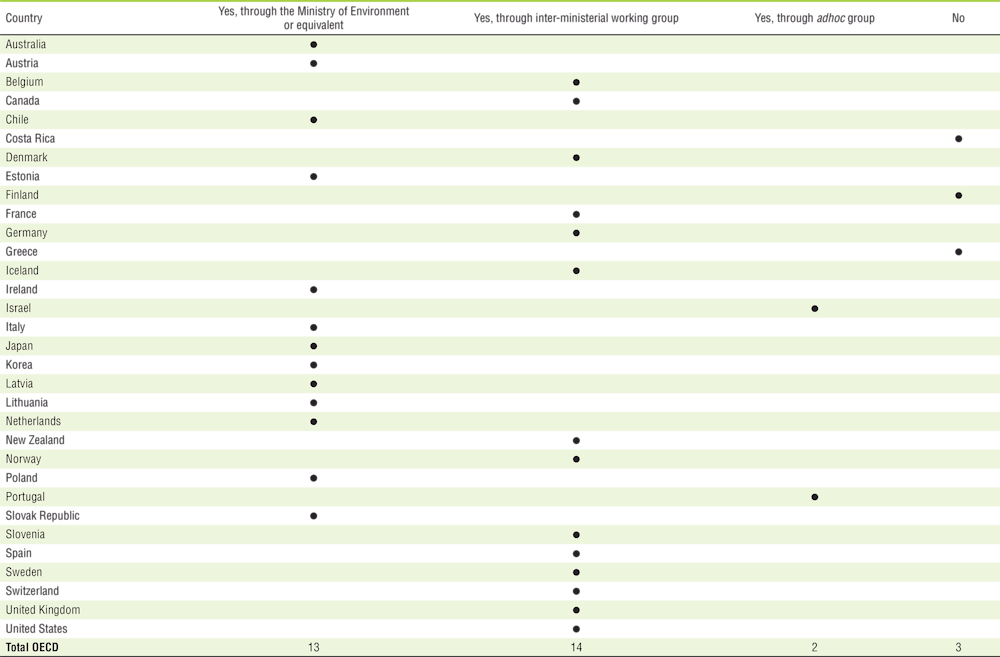

Considering the expertise needed to define ambitious and coherent objectives in GPP policies, public procurement authorities in all OECD countries rely on other government bodies. In 29 out of the 32 OECD countries with GPP strategies (90%), the national frameworks integrate a co-ordination mechanism to design, implement and revise GPP policies (Table 7.4). In 13 of these countries (45%), ministries of environment or similar agencies formally co-ordinate GPP and broader environmental policies, thereby reinforcing the role of GPP in implementing their environmental objectives. A further 16 countries (55%) rely instead on inter-ministerial or ad hoc working groups convening different stakeholders. In the United States, the alignment between GPP and environmental policies is assigned to one of the highest levels of government, the Executive Office of the President. In France, the General Commission for Sustainable Development, an inter-ministerial delegation for sustainable development, is responsible for steering the National Sustainable Procurement Plan (PNAD) 2022-2025.