Learning and development are essential components of a modern public service that is prepared for the future. Emergent policy challenges, unpredictable crises, and evolving technology combine to create a constant demand for new skills and competencies among public servants. To keep up, governments must find ways to source the capabilities they need, and this often means by developing existing staff. Well-designed and wide-reaching learning systems are therefore vital for governments, to continually develop staff throughout their careers and identify and address the need for skills over time.

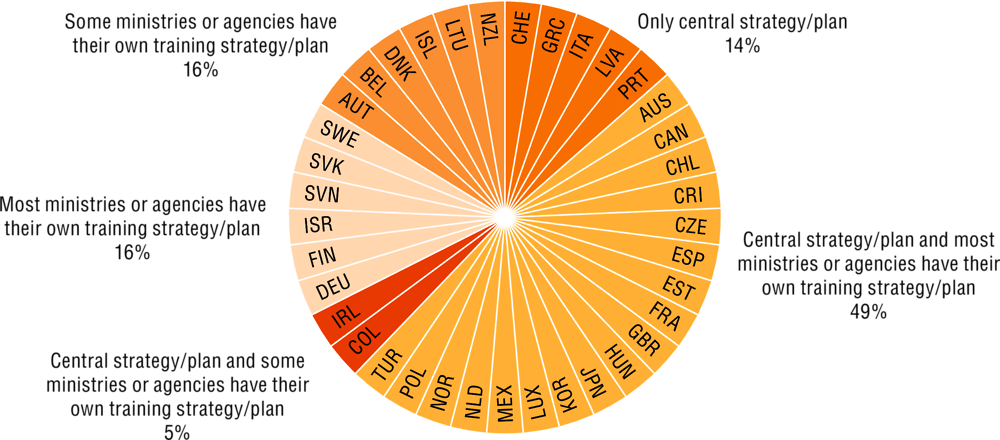

A learning strategy is an administration's overarching plan for the continuing development of skills and competencies within its workforce. OECD countries with learning and development strategies organise and implement them in a variety of ways. These strategies can be implemented through different institutional arrangements: they can be centrally organised, distributed throughout ministries, left up to individual managers, outsourced, run through schools of government or other means, or through a combination of options. The majority of OECD countries, 25 out of 37 (68%), have a learning and development strategy or plan at the central level (Figure 13.3). Many of these also report having additional strategies within ministries or agencies; 24 out of 37 countries (65%) have ministry-level plans, whether or not there is also one at the central level.

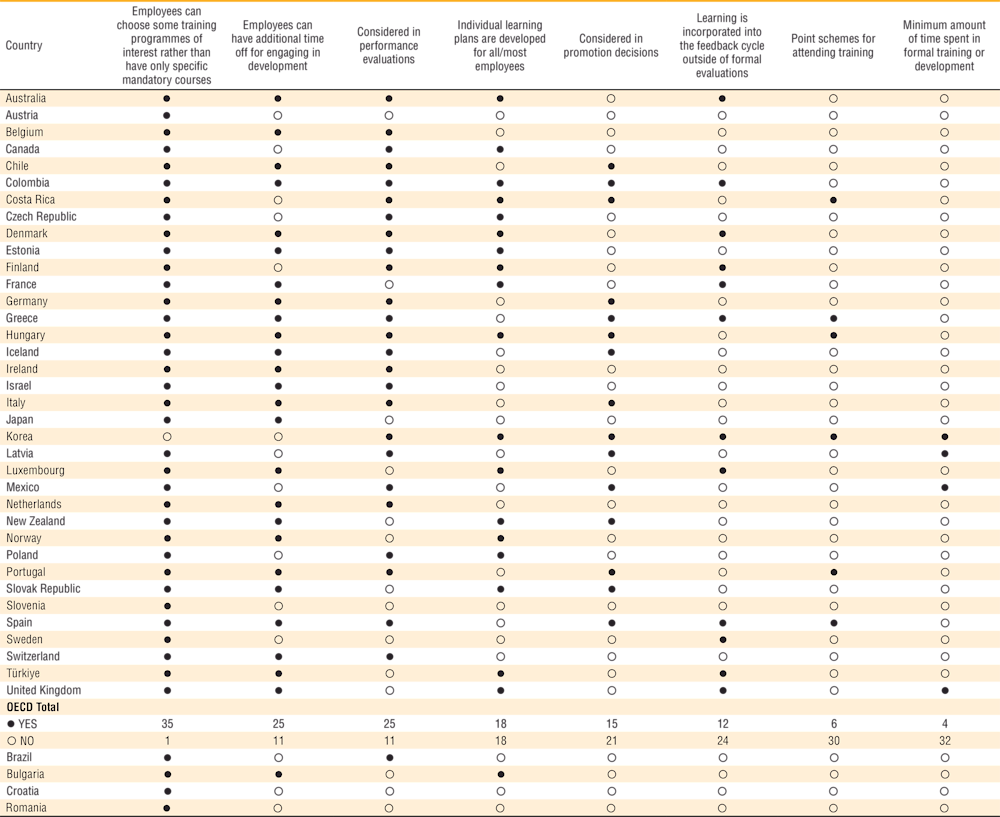

Well-designed incentive structures are important. They give employees reasons to take up learning opportunities and make use of the learning and development systems. These incentives are not necessarily financial; the use of performance evaluation, career progression and feedback cycles can be more effective and contribute more to an overall culture of learning. The most common practices to encourage learning are giving employees choices in the content of their learning (35 out of 36 OECD countries, 97%) and giving employees time to purposefully engage in learning opportunities (25 out of 36, 69%) (Figure 13.4). But more and more, OECD countries are encouraging learning by building it into other human resources processes in the career path: 15 of 36 countries (42%) consider learning in promotion decisions and 25 of 36 (69%) in performance evaluations, while 12 out of 36 (33%) incorporate it into feedback outside of formal evaluations. Only 4 of 36 countries (11%) mandate minimum amounts of training.

As governments continue to face unprecedented global and societal problems, having a depth and breadth of skills to call upon in the public service becomes more pressing. Learning and development is taking a leading role in modern governance. Korea, for instance, created a modern e-learning platform that allows employees to become micro-content creators and encourages greater learning through interaction. In the United Kingdom, the administration is working to bring the training offered across ministries under one umbrella to make it more widely available to its workforce of nearly half a million. Leadership development is a specific emerging focus. For example, Israel is developing a “simulator” to train its top managers to manage crises and change, while Canada has developed a leadership development programme and an in-depth competency framework across top levels.