Philip Haywood

Frederico Guanais

William Hynes

Francesca Colombo

Philip Haywood

Frederico Guanais

William Hynes

Francesca Colombo

Not being sufficiently prepared for a shock like the COVID-19 pandemic results in major loss of life and well-being, and requires costly interventions that have repercussions for years to come. Health systems must also be resilient to shocks beyond pandemics. This report uses the lens of the COVID-19 pandemic and the latest evidence to analyse how ready health systems were to prepare for, absorb and recover from a crisis, and how they can be adapted to be more resilient to future challenges. This report offers recommendations in six policy areas to improve health system resilience. These policy areas relate to the health system and to its interactions with broader society. Implementing these recommendations will produce health systems that deliver high-quality care before, during and after crises.

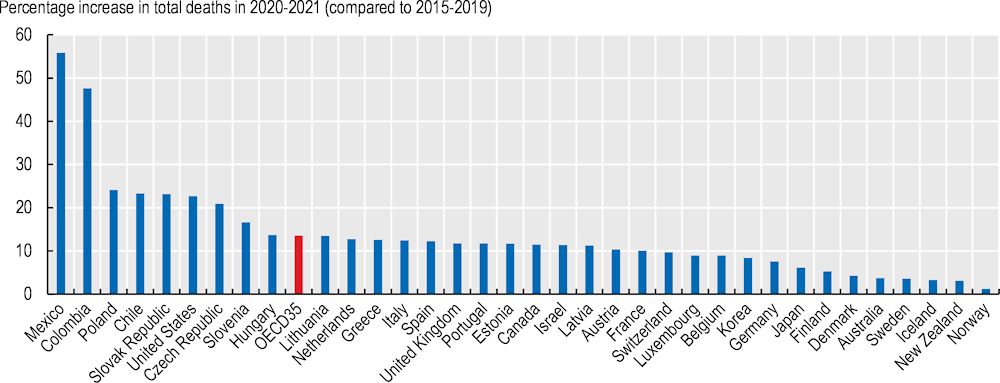

Globally, millions of people have died, and hundreds of millions have been infected with COVID-19. Over 6.8 million deaths due to COVID-19 were reported worldwide in January 2023 (WHO, 2023[1]). Analysis of excess mortality suggests that as many as 18 million people may have died worldwide because of the pandemic by the end of 2021 (Wang et al., 2022[2]). Overall, OECD countries have reported over 3.1 million COVID-19 deaths. There is a large degree of disparity between OECD countries - by the end of 2021, the percentage of excess deaths was 20 times higher in Mexico than in Norway (Figure 1.1). The COVID-19 pandemic led to a 0.8-year reduction in life expectancy across 28 OECD countries, comparing 2019 to 2021 (OECD, 2022[3]).

Note: Excess mortality is calculated by comparing the average annual deaths in 2020-21 with the annual average for 2015-19. Data for Colombia until week 35 in 2021 are included. No mortality data are available for Costa Rica, Ireland and Türkiye for 2020-21. OECD average is unweighted. Comparator years to calculate the percentage increase in total deaths are 2015-19.

Source: OECD (2022[3]), OECD Health Statistics, https://doi.org/10.1787/health-data-en, based on Eurostat data and national data.

Health systems were not resilient enough. Resilience is understood as the ability of systems to prepare for, absorb, recover from and adapt to major shocks (OECD, 2020[4]). It is not simply about minimising risk and avoiding shocks: resilience is also about recognising that shocks will happen. Such shocks are defined as high-consequence events that have a major disruptive effect on society.

The pandemic revealed weaknesses in health systems and in how they respond to shocks, highlighting the need to improve their resilience. Health systems need to prepare better for shocks – not only pandemics but also antimicrobial resistance; armed conflict; climate change; biological, chemical, cyber, financial and nuclear threats; environmental disasters; and social unrest. Health systems also need to be able to absorb such disruptions, to recover as quickly as possible and with minimal cost, and to adapt by learning lessons to improve performance and manage future risks.

While the COVID-19 pandemic has been called a “once-in-a-century” health crisis (WHO, 2020[5]), there is no reason to believe that health systems worldwide are safe from further shocks. Structural factors such as increasing global mobility, interconnectedness and digitalisation create new opportunities to deliver and improve health care. These factors, however, also create new risks or exacerbate existing threats, as exemplified by the threats of energy insecurity and the cost-of-living crisis in 2022-23. Other infectious diseases such as influenza, monkeypox and respiratory syncytial virus have also complicated provision of health care in OECD countries since the pandemic began (Fairbank, 2022[6]).

Health care in OECD countries is characterised by interdependencies at every level of the health system and beyond. As the health system becomes stressed and some functions cannot be undertaken, the burden and disruption flow through the system, further worsening outcomes. The way the health system is organised may propagate these shocks.

As the COVID-19 pandemic began, a sequence of demand and supply shocks compounded the overall effect on the system. For example, a sharp rise in infections increased demand for acute care, leading to stress in the healthcare workforce, reduced stocks of essential supplies, less space in critical care facilities such as hospitals and intensive care units, and large adverse impacts on long-term care facilities. This resulted in further infections among the general population and health workforce. In turn, this put additional pressure on the workforce and essential supplies. A resilient health system interrupts and limits these vicious cycles.

These interdependencies occur at a larger scale: health systems are dependent on larger societal systems to keep functioning. For example, infectious diseases may disrupt the functioning of essential services such as schools, public utilities and transportation, which in turn affect the functioning of health care. Public information may affect health-seeking behaviours. Health systems in individual OECD countries are also linked by vulnerabilities that go beyond health care. For example, supply chains and the logistics of health systems depend on international trade, and the workforce depends on the mobility of professionals.

The interdependencies also occur over time. Disrupted education and the loss of other investments could lower the productive capacity of OECD economies in the future, making it more difficult to sustain health systems. Early analysis based on data from OECD countries estimated that educational disruption following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic would produce an average reduction in GDP of 1.5% for the remainder of this century (Hanushek and Woessmann, 2020[7]).

Rather than relying solely on planning for, avoiding and absorbing shocks, a resilience approach acknowledges that some shocks will be of a size and scale that will disrupt an entire health system. In this scenario, it is important that the health system is capable of recovering and adapting for the future.

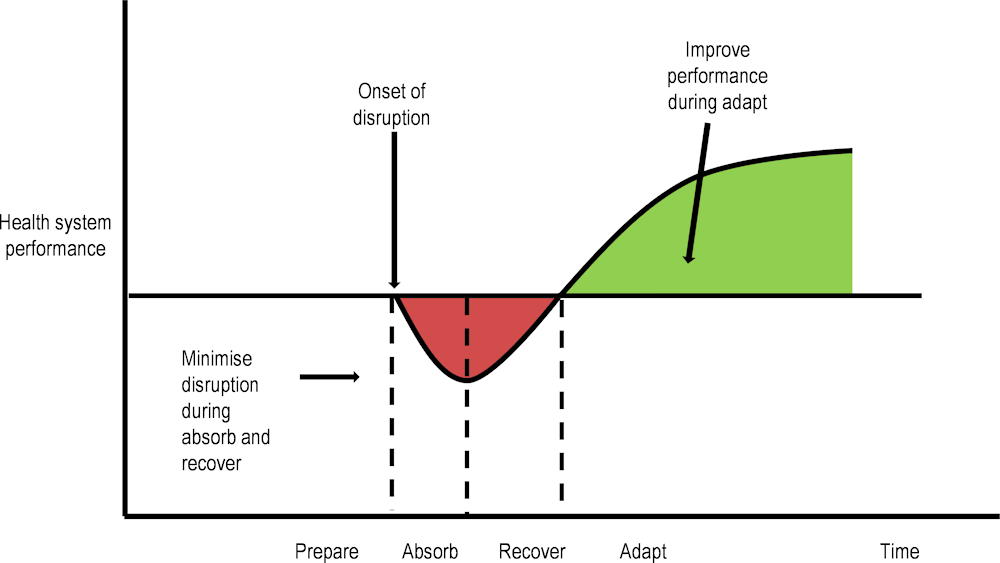

The disruption cycle comprises four stages (Figure 1.2):

Prepare includes the steps taken by the health system and related institutions to plan and prepare critical functions and features to avoid and mitigate a universe of potential shocks. It occurs prior to the disruption.

Absorb comprises the capability of the health system to maintain core functions and absorb the consequences of an acute shock or extended stress without collapse. It involves limiting the extent of the disruption and minimising the morbidity and mortality impact.

Recover involves the health system attempting to regain lost functions as quickly and efficiently as possible. It also refers to the time and resources needed for the system to recover its functionality after the shock.

Adapt relates to the capacity of the health system to “learn” and improve its capacity to absorb and recover from shocks based on past experience, reducing the impact of similar threats in the future. It informs planning and preparation for the next cycle.

Sources: Adapted from OECD (2019[8]), “Resilience-based Strategies and Policies to Address Systemic Risks”, https://www.oecd.org/naec/averting-systemic-collapse/SG-NAEC(2019)5_Resilience_strategies.pdf, and National Research Council (2012[9]), Disaster resilience: A national imperative, https://doi.org/10.17226/13457.

These stages are presented in sequence but are dynamic and integrated in practice. This is illustrated by the COVID-19 context. For example, a new variant of SARS-CoV-2 that escapes immune protection from vaccination could result in a shift backwards from the recover to the absorb stage. Furthermore, decisions made in one stage of the disruption cycle may have an impact on the subsequent stages – for example, stopping elective surgery during the absorb stage of the pandemic may affect the recover stage.

Resilience involves ensuring that health system performance continues under extreme stresses (Linkov et al., 2013[10]), and across the domains that determine its performance. This relates to factors within health systems (including capacity, physical resources, workforce and information systems) and beyond them (including a view of the socio-economic determinants of health). Experiences in the health sector, including outbreaks of the Ebola virus, also demonstrate the importance of considering resilience at different levels: the individual; the local community; institutions; and the whole system (see the chapter on resilience in other sectors, including for a case study on the Ebola virus).

Analysis of approaches to resilience in other sectors can be enlightening (Box 1.1). This analysis highlights there is no single way to quantify and improve resilience, with many methods and tools the subject of sector-specific practice and academic investigation.

Resilience has decades of application in other disciplines, beyond health. All resilience analysis requires stakeholders to adopt a perspective that recognises the connections between systems - interdependency - and the need to go beyond risk, to absorb, recover from and adapt to disruption.

Resilience is a rapidly developing field of endeavour. Many different approaches are used to analyse and improve resilience of systems, from scorecards and tabletop exercises to simulations using artificial intelligence. More advanced approaches require greater data and more sophisticated approaches to modelling the systems of interest.

Multiple sub-systems must work together for any system to be resilient. A generic conceptualisation of the sub-systems includes, but is not necessarily limited to, the following domains:

1. physical – equipment and facilities

2. information – data

3. cognitive – understanding and decision making

4. social – interactions between actors.

Resilience is a function of system performance and cannot be engineered in silos. Improving one domain without the others may not improve resilience. For example, over-relying on physical infrastructure (e.g. intensive care unit beds) and not considering social behaviour (e.g. adherence to containment and mitigation) will not produce a resilient system in response to a pandemic.

In the infrastructure sector, disruptions that place transportation networks or energy facilities offline cannot be effectively engineered against. A focus on maximum efficiency can leave systems vulnerable to disruption. This has meant that resilience efforts focus not only on mitigating risk and preparing for shocks, but on recovering and adapting to learn from them.

In the finance sector, the global financial crisis (2007-08) was the impetus for resilience thinking and implementation. Financial systems have operationalised resilience by trying to prepare for and absorb shocks through stress testing. The purpose of these tests is to identify areas of financial systems which should be bolstered. The results of these tests are published and can be brought into the public domain.

In the environmental sector, systems still require resilience, although they are formed not designed. For example, the Environmental Protection Agency of the United States has explored qualitative approaches to evaluating resilience. Resilience to the impacts of climate change is also a growing field.

Further, experiences in cybersecurity and digital systems show the potential for feedback loops and interdependencies between systems. For example, cyber attacks that disrupt the provision of essential goods and services, such as fuel, can result in hoarding behaviour, further exacerbating shortages.

The remainder of this chapter presents the key findings and recommendations of the report in parallel with the disruption cycle:

Section 1.3 summarises some of the pre-existing major vulnerabilities that showed that health systems were not ready for a crisis, as demonstrated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Section 1.4 analyses the strengths and weaknesses from a resilience perspective of OECD health systems, primarily through the lens of how well these systems absorbed the impacts of the pandemic, while appreciating the array of other future threats.

Section 1.5 recognises that a crisis often creates a legacy of policy choices, inadvertent consequences and lingering impacts, even as new crises unfold. It outlines contemporary efforts by OECD health systems to recover from the pandemic. The recover stage of the pandemic began when normal health system functions resumed – namely, when vaccination coverage became widespread, containment and mitigation measures were reduced, and efforts began to address deferred and delayed care.

Section 1.6 recommends policy actions, based on this report’s key findings, in support of OECD countries investing in health system resilience to be ready for the next crisis. The recommendations relate not only to being ready for future pandemics but also to improving readiness to prepare for, absorb, recover from and adapt to a broader range of future challenges.

Finally, the benefits of investing in resilience are highlighted in Section 1.7.

As well as the available literature this report draws upon multiple OECD data collections and surveys (Box 1.2), as well as case studies.

This report draws on the regular data collections of the OECD and supplementary information. A questionnaire on resilience was used to inform both responses to the pandemic and future intentions to improve health system resilience. The questionnaire focused on several important areas including workforce, care continuity, mental health, pandemic planning and investments. It was sent to OECD countries on 3 December 2021, and responses were accepted until April 2022. The details of the questionnaire and additional material are in Annex A. A total of 26 countries participated in the OECD Resilience of Health Systems Questionnaire 2022.

Additional questionnaires and surveys that this report draws on include: the OECD Survey on Telemedicine and COVID-19 answered by 31 countries (OECD, 2023[11]); the OECD Health Data and Governance Changes during the COVID-19 Pandemic Questionnaire 2021 answered by 24 countries (de Bienassis et al., 2022[12]); the 2021 OECD Survey on Electronic Health Record System Development Use and Governance answered by 26 countries; and the 2021 OECD Questionnaire on COVID-19 in Long-Term Care answered by 26 countries.

The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated uneven efforts across OECD countries to prepare fully for health system disruption, underscoring the need for a resilience approach. It is now appreciated that national pandemic preparedness was underfunded prior to the pandemic (The Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness, 2021[13]). Furthermore, the pandemic revealed underlying structural weaknesses in health systems and societies: underdeveloped plans around issues such as civil engagement and procurement of supplies; social and economic inequities; vulnerabilities in population health and long-term care systems; fragmented digital infrastructure resulting in fragmented data; and some OECD countries with limited spare capacity in their workforce and a lack of other critical resources. While these weaknesses were exposed in the context of the pandemic, they reveal that more investment is needed for health systems to be ready for a broader range of future shocks.

Health systems need to implement policies to respond to all four stages of a disruption: prepare, absorb, recover and adapt. Preparation is necessary but not sufficient for resilience (The Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness, 2021[13]).

Required resources and capabilities should be anticipated during the prepare stage and made available for best use during the absorb and recover stages. For example, enhancing the capacity for surveillance, tracing/tracking and case management has been emphasised as key to effective pandemic planning and response. After the COVID-19 pandemic began, however, the available health workforce, critical care resources for COVID-19 patients and personal protective equipment (PPE) were highlighted as insufficient.

Further, fewer than one-third of countries responding to the OECD Resilience of Health Systems Questionnaire 2022, had delineated capacities/strategies in their national pandemic preparedness plans to promote societal co-operation, such as social and financial support for those affected, civil society engagement, and management of privacy or ethical issues.

Governance impacts on the trajectory of a crisis but it can be neglected in preparedness (World Bank, 2022[14]). Countries can strengthen health system resilience by improving decision making processes, creating strong health institutions, and leveraging whole-of-government and whole-of-society approaches (EU Expert Group on Health Systems Performance Assessment (HSPA), 2020[15]). Health systems require frameworks for decision making and co-ordination to be introduced prior to a shock occurring, so that these can be activated at the appropriate time during the disruption cycle. Mechanisms for facilitating multisectoral co-operation, ensuring civil engagement and sustaining public trust also cannot be created at short notice when a shock occurs. Their absence may have profound effects during the absorb and recover stages of a crisis (see the chapter on containment and mitigation).

Conversely, putting in place mechanisms for multisectoral co-operation may improve the speed of response to a shock. For example, prior to the pandemic, Korea had built an epidemiological investigation support system that integrated information from a wide range of sectors to identify cases and trace contacts quickly. Several elements of this system built on Korea’s review of experience with the Middle East respiratory syndrome outbreak of 2015 (OECD, 2022[16]).

Misinformation and disinformation have the potential to undermine co-operation (Box 1.3). Before the COVID-19 pandemic, very few OECD countries (2 of 18 responding countries) reported that they had developed government strategies, plans or other guiding documents to inform health ministries about how to respond to disinformation (OECD, 2021[17]). Despite the potential for civil society to act as an important partner in countering misinformation and disinformation narratives, the majority of responding countries reported that their health ministries did not consult civil society groups on countering disinformation, and only one (Türkiye) reported that consultation happened on more than an ad hoc basis.

Disinformation about COVID-19 is quickly and widely disseminated across the Internet, reaching and potentially influencing many people. Data from Argentina, Germany, Korea, Spain, the United Kingdom and the United States show that about one in three people said they saw false or misleading COVID-19 information on social media. Research has also shown that COVID-19 disinformation is disseminated more widely than information about the virus from authoritative sources like the World Health Organization (WHO).

The OECD has identified four key actions to counter COVID-19 disinformation on online platforms: supporting a multiplicity of independent fact-checking organisations; ensuring that human moderators are in place to complement technological solutions; voluntarily issuing transparency reports about COVID-19 disinformation; and improving users’ media, digital and health literacy skills (OECD, 2020[18]).

Governments would benefit from exploring a more holistic approach to the challenge of disinformation, combining initiatives to ensure that truthful and reliable information is accessible, and that the spread of dangerous content is reduced. These initiatives should rest on the open government principles of transparency, integrity, accountability and stakeholder participation. The OECD could play a role in building a global evidence base on this evolving challenge and the relative efficacy of the responses, including potential regulatory responses. Addressing disinformation with concerted action, alongside effective and authoritative public communication, is crucial to fostering public trust (Matasick, Alfonsi and Bellantoni, 2020[19]).

Improving the health of populations, strengthening primary care and its linkage with long-term care, and empowering patients improves the resilience of health systems. It does this by reducing the strain on the health system during disruptions and decreasing the probability that it will be overburdened. Recent spending on disease prevention is low, at only 2.7% of total health expenditure across OECD countries in 2019 (OECD, 2021[20]), and has been consistently low over time (OECD, 2005[21]).

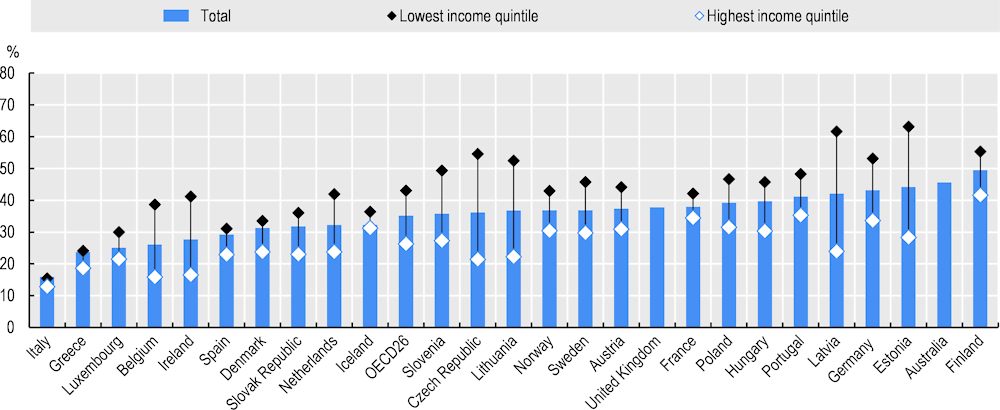

Multimorbid patients are vulnerable to disruptions in care, which can lead to severe consequences and long-term complications. This group of patients has high utilisation rates of health care – often seeing multiple providers – and high rates of emergency department visits and hospital admissions. Data from just before the pandemic showed that, on average, 35% of the population across OECD countries had a longstanding illness or health problem. Prevalence was even higher for the population in the lowest income quintile, reaching 43% (Figure 1.3).

Note: Data refers to 2019 or nearest year. Data for Australia refer to people aged 18 and over living with at least one chronic condition, and refer to 2017-2018.

Source: European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions instrument (EU-SILC) 2021 and national health surveys, presented in OECD (2021[20]), Health at a Glance 2021: OECD Indicators, https://doi.org/10.1787/ae3016b9-en.

The high prevalence of chronic disease in OECD countries was a contributing factor to mortality rates during the pandemic. Obesity and chronic diseases such as diabetes were risk factors for serious health impacts and death from COVID-19 (Barron et al., 2020[22]). OECD countries where pre-pandemic treatable mortality was low experienced better health outcomes (see the chapter on COVID-19 outcomes).

Considering mental health needs and the sufficiency of mental health services before a widespread and severe shock reduces the size of the population that is vulnerable after a shock, thereby helping to mitigate its impact. Population mental health services and their provision outside the health system (for example, in schools and workplaces) are important to a multi-faceted response.

Poor co-ordination between primary care and long-term care has been a longstanding issue. In 2019, between 36% and 88% of the primary care providers in 11 OECD countries reported not co‑ordinating care frequently with social care or other community care services (Doty et al., 2020[23]). Only ten OECD countries reported having guidelines or legislation on the integration of long-term care and primary care before the pandemic.

Universal health coverage, improving population health and reducing disparities in risk factors diminishes both inequities in outcomes and demand for acute services during a crisis. Undertaking these prior to a crisis occurring reduces the vulnerabilities of the population and improves the performance of health systems during the absorb stage of a shock.

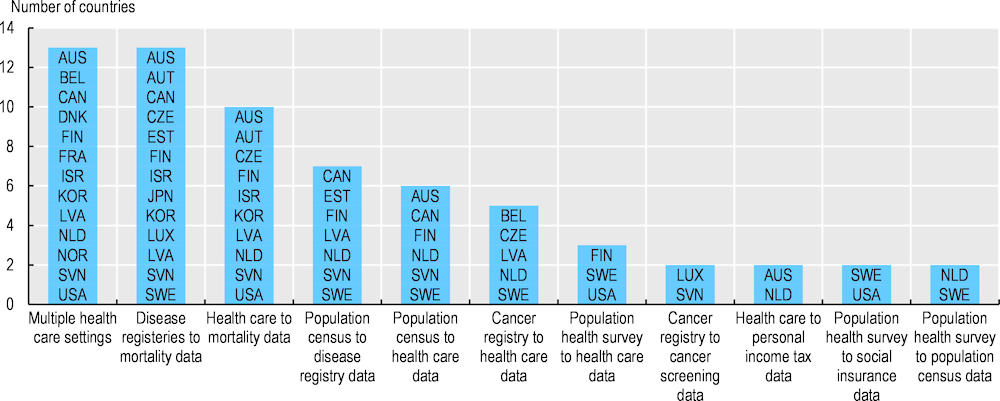

Decision makers are flying blind unless they have access to timely data, and the tools to convert it into actionable information. Without data, threats cannot be identified; the effectiveness and unanticipated consequences of policies cannot be monitored and evaluated; and the implications of not introducing policies cannot be fully appreciated. Information is needed for all stages of the disruption cycle.

Prior to the pandemic, data infrastructure within the health system was fragmented. Only 14 OECD countries were able to link data across multiple settings within the health system (Figure 1.4). A smaller number had real-time data available for some data collections (Oderkirk, 2021[24]).

Source: Adapted from Oderkirk (2021[24]), “Survey results: National health data infrastructure and governance”, https://doi.org/10.1787/55d24b5d-en.

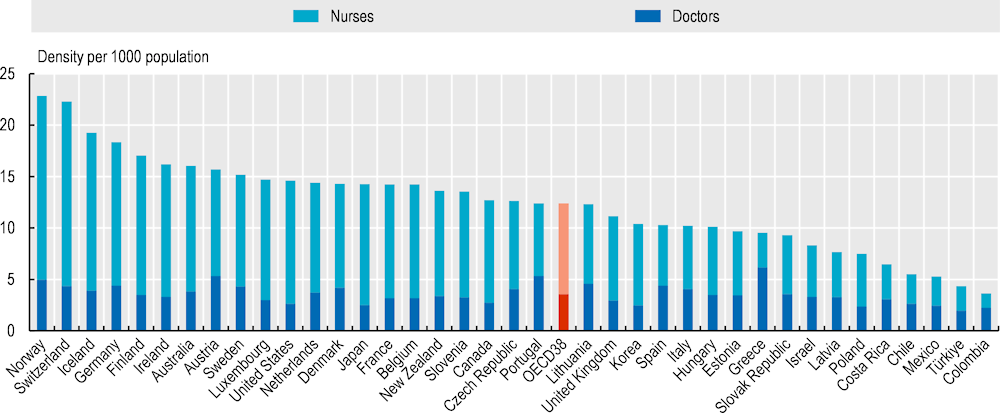

Both the capacity and the spare capacity of health systems in key areas such as workforce and the availability of critical care resources varied greatly across OECD countries prior to the pandemic. Variation was six-fold in the number of doctors and nurses per capita across OECD countries prior to the pandemic (Figure 1.5).

Note: In Portugal and Greece, the number of doctors refers to all doctors licensed to practice, resulting in a large overestimation of the number of practising doctors (e.g. of around 30% in Portugal). In Greece, the number of nurses is underestimated, as it includes only those working in hospitals. The data from Finland date back to 2014.

Source: OECD (2022[3]), OECD Health Statistics, https://doi.org/10.1787/health-data-en.

Prior to the pandemic, there were also indications in some OECD countries of insufficient physical infrastructure and a lack of spare capacity. For example, four countries reported an occupancy rate of around or over 90% for acute care beds in 2019, while eight countries had less than half the mean number of adult intensive care beds across OECD countries (OECD, 2021[20]).

These limitations flowed into the absorb stage of the COVID-19 pandemic, hampering some responses and making the consequences of the pandemic more significant than they might otherwise have been. Investments in population health, data and key aspects of health system capacity would help to address these challenges, bolstering health system resilience (see chapters on digital foundations and COVID-19 outcomes).

The response of countries to absorb the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic was rapid and, in many cases, exceptional. During the absorb stage, countries implemented whole-of-society containment and mitigation measures, increased resources for the health system, moved resources to critical care, transitioned to different models of care such as telehealth, and changed health workforce roles and responsibilities (see chapters on containment and mitigation, critical care surge, care continuity, and the health workforce). Importantly, the stresses on populations were also partially mitigated by means other than health care – for example, by financial, employment and community support.

Additional health system resources (including to support the healthcare workforce), better information and modelling, a whole-of-society approach and flexibility in healthcare provision all played a role in mitigating the severity of the disruption in some OECD countries. They also led, however, to a reduction in regular health care and widespread cancellation of procedures (see the chapter on waiting times).

Weaknesses in the prepare stage also made it more difficult to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic during the absorb stage. Some health systems were running at capacity prior to the pandemic. Timely information was lacking, and the numbers of supplies, staff and treatment facilities relative to demand were inadequate. Supply chains of many essential goods were disrupted. Fragmentation of responses, lack of co-operation and, at times, even competition for scarce resources also hampered responses during the absorb stage (see the chapter on securing supply chains). COVID-19 magnified the impact of poor care integration in many OECD countries, and demonstrated the impact of limited co-ordination at the international level.

The COVID-19 pandemic revealed and highlighted major vulnerabilities in health systems that call for greater investment. Increased vulnerabilities meant that both the direct consequences of COVID-19 and its indirect impacts were larger than they might otherwise have been. If a health system does not have the critical resources it needs at crucial times, its functioning is inefficient and costly; further, their absence can have disastrous impacts. When resources, such as PPE, were insufficient, the COVID-19 mortality rate increased and the health workforce was infected (Verbeek et al., 2020[25]).

Improving the resilience of society depends on the health system, and strengthening the resilience of the health system depends on society. Communicating risk and uncertainty requires trust in and transparency from institutions, including the media. Communication can be undermined when there is a lack of trust (Edelman, 2022[26]). Trust in institutions is especially important in absorbing shocks of a scale and severity that they affect everyone.

During 2020 – the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic – public understanding and co-operation were essential to containment and mitigation. In Ireland, for example, Amárach public opinion surveys were conducted regularly to inform communications and decisions made by the Department of Health. The results of the surveys were made publicly available and shared across government departments.

Community involvement in decision making also engendered buy-in to critical measures. In Lithuania, representatives from community organisations were included in a working group to help co-ordinate and assist in minimising the harms caused by the pandemic. In Costa Rica, a shared management model – “Costa Rica works and takes care of itself” – encouraged ownership of containment measures from the community level up and facilitated a sense of responsibility to follow public health requirements.

Nonetheless, many countries struggled to implement containment strategies in a timely manner, even though they had been evaluated as prepared by assessments such as the Global Health Security Index (Haider et al., 2020[27]). This demonstrates that while “planning well” is necessary, it is not sufficient for an effective societal response. A failure to implement containment strategies proactively led to use of more stringent containment and mitigation strategies – such as lockdowns – during the early stages of the pandemic, with negative socio-economic impacts (see the chapter on containment and mitigation).

To implement timely and effective interventions to a disruption of significant scale and severity, many parts of government need to be marshalled – budgets allocated; the co-operation of local administrations secured; essential equipment procured and delivered; and strategic communications conveyed – all in a way that complements and facilitates the health response.

Most OECD countries responding to the OECD Resilience of Health Systems 2022 (20 of 23) implemented a whole-of-government approach as part of their pandemic response. For example, Luxembourg’s agility in its COVID-19 response was evaluated as partly attributable to its inter-ministerial management, aided by fiscal and social support of households and businesses (OECD, 2022[28]). Such an approach was important to the effectiveness of a range of measures, including containment and mitigation.

Collaboration and co-ordination within health systems foster resilience by reducing vulnerabilities and increasing the effectiveness of resource use. There were several positive examples of how different levels of collaboration helped OECD countries absorb the shock of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Load-balancing – using networks of intensive care units (ICUs) and sharing the burden by transferring patients to ensure that no individual ICU is overwhelmed – for critical care requires national and sub-national authorities to co-ordinate and inject resources. All OECD countries used real-time data to improve co-ordination during the critical care surge, accompanied by changes in institutional arrangements. Most OECD countries responding to the OECD Resilience of Health Systems Questionnaire 2022 (15 of 18) integrated public and private facilities into the same network, and over two-thirds (13 of 19) increased the effective size of their hospital networks. Crisis care protocols were widely used. Almost all reporting countries (20 of 21) used modelling to predict the critical care capacity required to respond to the pandemic and found modelling useful to plan resources (see the chapter on critical care surge).

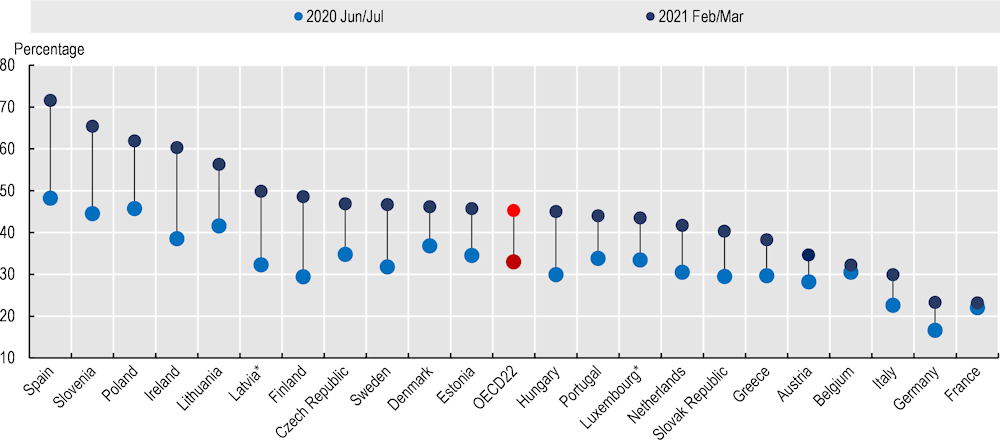

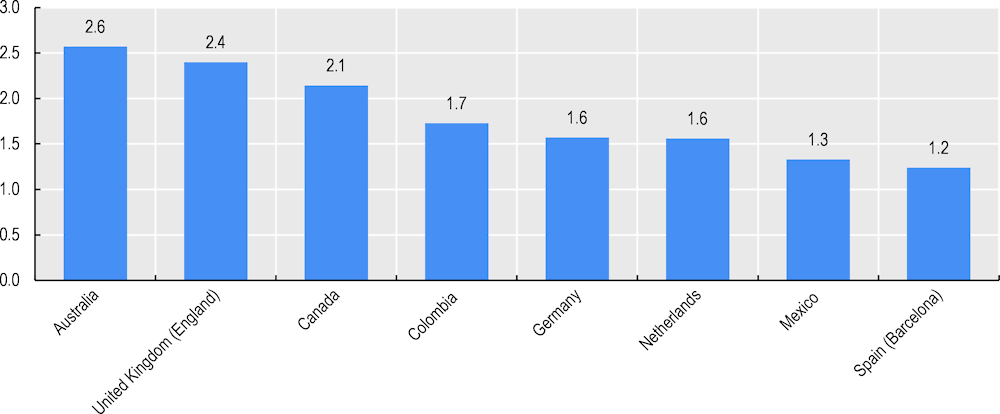

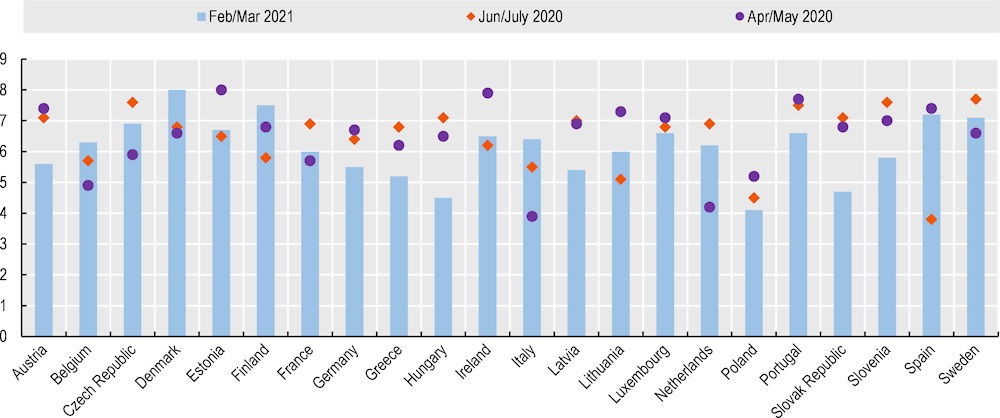

Welcome transformations occurred in healthcare delivery. The need for physical distancing saw OECD countries move usual health system functions to different locations or different providers (OECD, 2021[20]). Nearly half of adults in 22 OECD European countries reported receiving medical consultations online or via telephone (Figure 1.6).

Note: The data show numbers of OECD country respondents in the EU27 answering “Yes” when asked “Since the pandemic began, have you received any of the following services from a doctor? Online health care: medical consultation online or by telephone”. The survey was carried out in June/July 2020 and February/March 2021. * Data for Latvia and Luxembourg are of low reliability.

Source: Eurofound Living, Working and COVID-19 Survey dataset.

OECD countries also adopted strategies to maintain continuity for ongoing care needs by delegating new roles and responsibilities to health workers. These strategies ranged from increasing the role of nurses and community health workers to provide home-based care (Slovenia, the United Kingdom and the United States) to allowing community pharmacists to prescribe or extend prescriptions for chronic conditions (Austria, France and Portugal).

Changes to service provision in response to the pandemic relied on the local-level adoption of new models of care – telemedicine was an example of this flexibility. OECD countries used multidisciplinary teams with public health and community services to proactively contact patients with underlying health needs. For example, in Australia, general medical practices – which comprise general practitioners, primary care nurses, allied health and other healthcare professionals – provided essential primary care services to their patients for chronic conditions, preventive care and mental health concerns (Desboraugh et al., 2020[29]). In Lithuania, mobile teams of primary care professionals were introduced to visit patients in their homes to provide primary care services.

The effectiveness of testing and containment was also influenced by the extent of healthcare coverage. For example, Korea’s rapid scaling up and implementation of testing, tracing and tracking was facilitated by their health coverage eliminating out-of-pocket charges for COVID-19 related diagnosis and treatment (Dongarwar and Salihu, 2021[30]). OECD countries where the entire population had health coverage for a key set of health services experienced better health outcomes (see the chapter on COVID-19 outcomes).

Flexibility in health financing supported innovation in service provision and models of care. It ensured that providers continued services (for example, by funding telehealth), delivered new services (for example, by funding vaccinations), aided containment and mitigation (for example, by ensuring coverage and low out-of-pocket charges) or avoided inappropriate incentives (for example, by moving to block funding and global budgets) (Thomas et al., 2020[31]).

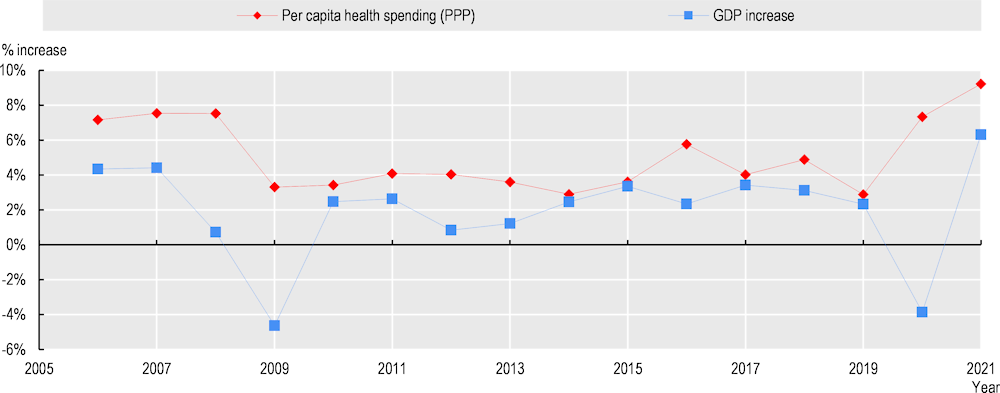

The need to increase critical care surge capacity to address COVID-19 saw governments intervene to increase resources for the health system. There was a per capita increase in health spending of over 6% across OECD countries at the same time as GDP contracted in 2020 (Figure 1.7). The share of GDP allocated to health expenditure increased by approximately 1% in 2020.

Note: Only OECD countries (20) with data for the complete series are included in the analysis. An unweighted average of the annual percentage increase for OECD countries was calculated. 2021 figures are provisional. Current purchasing power parity (PPP) was used for health spending increase calculations.

Source: OECD (2022[3]), OECD Health Statistics, https://doi.org/10.1787/health-data-en.

This increase in resources was accompanied by widespread cancellations of elective procedures and reprioritisation of resources – both physical and workforce – to critical care surge capacity. An 8% increase in critical care beds was reported (see the chapter on critical care surge). Without increasing the critical care surge capacity many health systems would have been even more overwhelmed, as the number of ICU patients with COVID-19 exceeded the previous capacity. Despite this, over three-quarters of countries (16 of 21) that responded to the OECD Resilience of Health Systems Questionnaire 2022 used crisis standards of care, which meant a move from supplying everyone with appropriate care to ensuring that the most lives were saved.

The lack of timely information was a key limitation when countries sought to absorb the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. Countries found that they lacked basic timely data – on hospitalisations, healthcare workforce, resources and mortality (de Bienassis et al., 2022[12]). Not having sufficient information on populations living in vulnerable and marginalised conditions was a weakness. For example, poor data measurement and evaluation of long-term care facilities hampered the response to COVID-19 during the absorb stage (Rocard, Sillitti and Llena-Nozal, 2021[32]).

As the pandemic continued, countries took steps to collect important data, either via surveys or by repurposing existing data collections. Data were collected on COVID-19 cases and mortality, population mental health symptoms, critical care resources and their use, and the well-being of the health workforce.

COVID-19 also served as a catalyst for mobilising resources to improve the use of data. All countries that responded to the 2021 OECD Survey on Health Data and Governance Changes improved mechanisms for data reporting: almost all improved the timeliness of health data; and 63% implemented regulatory changes or policy reforms to improve data availability (de Bienassis et al., 2022[12]).

Information technology improvements and adaptations accelerated (see the chapter on digital foundations). Many OECD countries (18 of 24) introduced new technologies to improve health data availability, accessibility, sharing or data privacy and security protection. Some introduced legislative reforms to facilitate data sharing to monitor COVID-19. Financial incentives were introduced in a quarter of responding OECD countries (6 of 24) (de Bienassis et al., 2022[12]).

The response to the pandemic was also facilitated by new data linkages, and by moving information to where it was needed most. This information was used by decision makers at different levels to balance the many competing resource needs. The value of information to multiple actors should be fully appreciated. It is crucial to making decisions with greater confidence, and to effective and efficient use of resources.

Nonetheless, data limitations persist. The ability to monitor unintended consequences of policies and to anticipate key failures is important for resilience. Without information about the distribution of benefits and harms across the population, pre-existing inequities can be worsened. Assessing harms and benefits across a population requires information not only about age and sex but also comorbidities, socio-economic status and other markers of vulnerability, such as homelessness and long-term care facility residency, to make fully informed decisions. Such depth of data collection is not present in most OECD countries – this may undermine an effective response to future crises.

The pandemic introduced additional pressures on medical and medical device supply chains (see the chapter on securing supply chains). It led to unprecedented spikes in demand for those medicines and medical devices needed to treat COVID-19 patients and to protect the health and long-term care workforce and the population from infection risk. This included PPE, ventilators, vaccines and critical care medicines.

Other factors also contributed to extraordinary tension in procurement of essential medicines and medical devices at a time when supply chains were already vulnerable. Lockdown policies and other containment measures created disruptions in production and international transport networks. Further, some governments introduced export restrictions that exacerbated existing shortages and worsened the situation by triggering similar actions in other countries.

Significant shortages were observed globally for PPE (Gereffi, 2020[33]). Almost all countries (23 of 25) responding to the OECD Resilience of Health Systems Questionnaire 2022 had a problem with securing PPE. Most responding countries reported a problem with testing materials (19 of 23), ventilators (17 of 25), vaccines (15 of 25) and sanitiser (14 of 24). While supply chains for medicines showed relatively greater resilience, demand increased significantly for medicines used in intensive care – such as anaesthetics – creating disruptions in supply and local shortages. While two-thirds (16 of 24) of OECD countries reported supply chain difficulties during the early response to the pandemic, most also reported that the situation resolved over time.

Domestic production, supply chain diversification, regulatory changes and central co-ordination mitigated supply chain disruptions. While diversification and the requirement to increase supplies quickly raised the risk of product quality, countries invested in increased product testing and offered support to new suppliers and manufacturers to guarantee quality. Open international trade was also important. Trade of essential medical products increased in response to the shortages – for example, imports of facemasks into the United States increased by 1 000% (Andrenelli, Lopez-Gonzalez and Sorescu, 2022[34]).

Nonetheless, the months between the increase in demand for essential medicines and medical goods and the rise in supply to match it had a devastating toll. A resilient health system must be able to reduce this delay and mitigate its effect.

The pandemic demonstrated that efforts to increase the size and skills of the health workforce are essential to improving health system resilience. Workforce limitations proved to be a more binding constraint for healthcare provision than hospital beds or equipment in absorbing the pandemic (OECD, 2021[20]).

An adequate and well-trained workforce saves lives. Public health workers were also a key part of the pandemic response (see the chapter on containment and mitigation), as they carried the burden of contact tracing, case and contact investigation, testing and eventually vaccination.

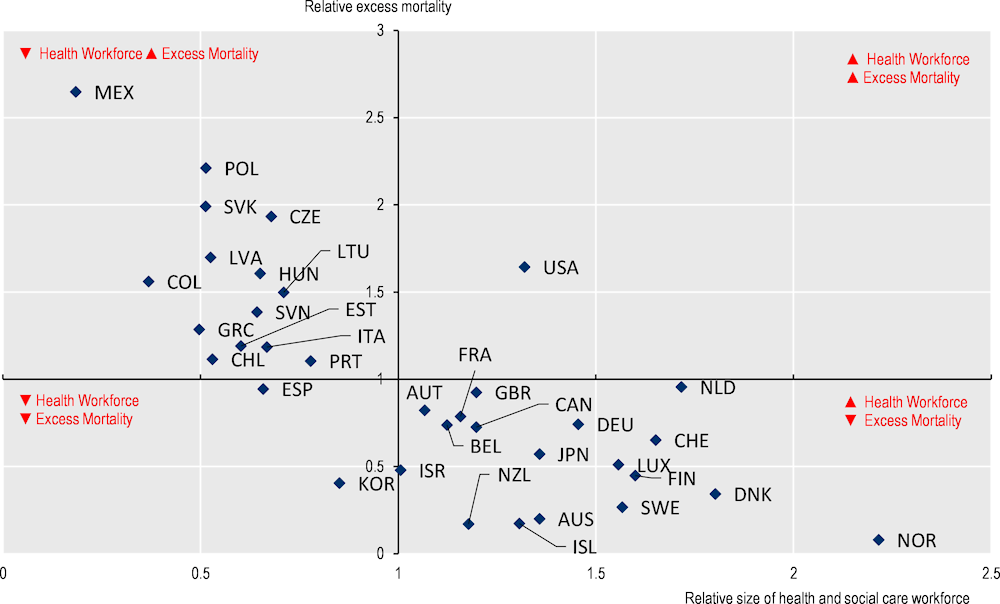

Although rapid and strong public health interventions to contain the spread of SARS-CoV-2 were important, higher numbers of health and social care providers were associated with better outcomes, such as lower mortality (Figure 1.8; and see chapters on COVID-19 outcomes and workforce). A higher staffing rate was associated with lower death rates in long-term care facilities (see the chapter on long-term care).

Note: The quadrant chart shows the association between the health and social care workforce and excess mortality. The x-axis shows how much a country is above or below the OECD average for total health and social employment in 2019 (per 1 000 population); the y-axis shows a country’s distance from the OECD average excess mortality rate for 2020-21. Note that this analysis does not adjust for other factors; nor does it necessarily infer causality.

Source: OECD (2022[3]), OECD Health Statistics, https://doi.org/10.1787/health-data-en.

No country that responded to the OECD Resilience of Health Systems Questionnaire 2022 reported that workforce shortages had a low impact on their capacity to respond to the pandemic (see the chapter on workforce). There was, however, heterogeneity in responses. Nearly half of responding countries (9 of 22) reported that health workforce shortages had a high or medium-high impact on their response capacity. Canada, Japan, Latvia, the United Kingdom and the United States were among this group. Conversely, Finland, Greece, Luxembourg and Switzerland considered that health workforce shortages had a low-to-medium impact on their capacity to respond.

The lack of an appropriately skilled workforce was a key hindrance when it came to increasing critical care capacity (see the chapter on critical care surge). Most countries (17 of 22) reported that the number of nurses working in hospitals was an issue, and specifically almost all (19 of 22) reported that nurses working in ICUs were in short supply. Beyond critical care, two-thirds of countries (14 of 22) reported that a lack of healthcare assistants in nursing homes was an issue.

Another key priority in the absorb stage was to protect health (including long-term care) workers. Many health workers became infected during the first few months of the pandemic, when the shortage of PPE was a major issue (as noted above). The mental health of health workers also suffered (Aymerich et al., 2022[35]). Several OECD countries are continuing to take steps to protect the well-being of the healthcare workforce, and an increasing number are assessing healthcare worker well-being.

Many OECD countries sought to expand their workforce capacity in response to the pandemic, using a similar set of policies. These policies included increasing the efforts of the current workforce, bolstering it with clinical staff, increasing it with non-clinical staff, redeploying staff and changing worker roles and responsibilities.

All countries that responded to the OECD Resilience of Health Systems Questionnaire 2022 mobilised additional staff in response to the pandemic. Nearly all mobilised students nearing the end of their studies in medicine, nursing and public health to staff population hotlines, support testing and contact tracing, and provide care in hospitals. Most countries also called in and reregistered retired or inactive doctors and nurses. Some countries accelerated the recognition of qualifications and registration of foreign-trained doctors and nurses (including Canada, France, Spain, the United Kingdom and the United States).

Only a few countries had put in place a reserve of health workers before the pandemic. This was the case in France where a health reserve was established in 2007 following the avian influenza pandemic. At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, France introduced new mechanisms to match the urgent demands from hospitals and long-term care facilities with volunteers in different regions of the country. Soon after the pandemic began, other countries set up national reserves to mobilise additional civilian or military staff (such as Belgium, Luxembourg and Norway).

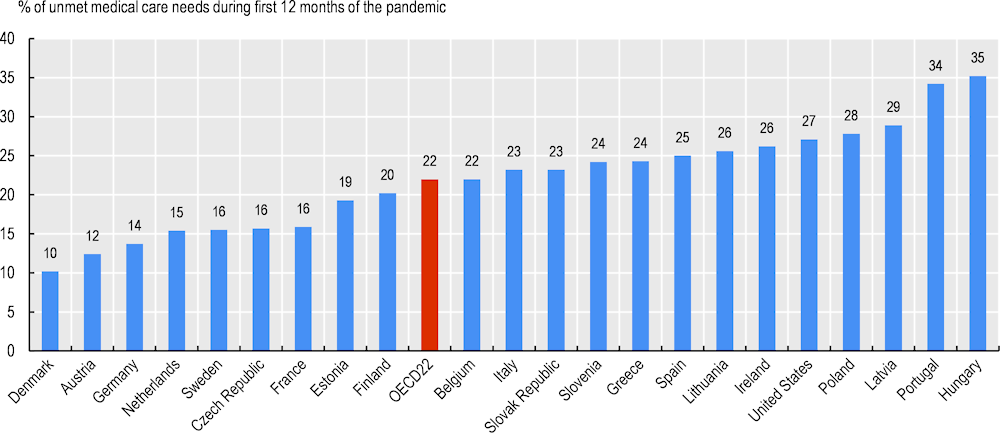

Reductions in healthcare utilisation were experienced from the patient perspective. Many essential services were postponed or forgone (see section 1.5.3). On average across 22 OECD countries with comparable data, more than one in five people reported having forgone a needed medical examination or treatment during the first 12 months of the pandemic (Figure 1.9; see chapters on waiting times and care continuity).

Note: Data for Luxembourg are excluded due to low reliability.

Sources: Eurofound Living, Working and COVID-19 Survey carried out in February/March 2021, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Household Pulse Survey carried out between April 2020 and April 2021.

Delays in access to diagnostic services were also observed in many countries, with an average decline of over 5 percentage points in the proportion of women screened for breast cancer across 23 OECD countries. Further, an estimated 100 million cancer screening tests were not performed in Europe as a result of the pandemic, and 1 million patients living with cancer remained undiagnosed due to a backlog of screening tests. Such care disruption has come at a high cost for people and health systems.

Those living with chronic health conditions were particularly affected. Among people aged 50 years and over, those with a chronic condition were, on average, over 40% more likely to report either forgoing or postponing medical care from the start of the pandemic.

Mortality data from several OECD countries confirm that vulnerable populations have borne a disproportionate burden from the COVID-19 pandemic. In some countries, the rate of relative mortality doubled for those living in the most deprived areas compared to those in the least deprived (Figure 1.10). Similar relative mortality increases were found for ethnic minority populations (Office for National Statistics, 2022[36]).

Note: Data are not directly comparable across OECD countries and regions – while the rate ratio is age-adjusted or multivariate methodology used in all countries, the timeframe of observation differs. For example, in Australia the data cover the first year of the pandemic to May 2021, while in Canada data cover the period January-August 2020.

Source: Berchet (forthcoming[37]), “Socio-economic and ethnic health inequalities in COVID-19 outcomes across OECD countries”.

There are multiple reasons why vulnerable populations have suffered disproportionately. These include: increased exposure to SARS-CoV-2 through working and living conditions; a higher prevalence of health conditions and risk factors, such as diabetes, obesity and smoking; and barriers to access and use of health care. For example, a study from the United States assessing older patients with chronic health conditions found that one-quarter of Medicare patients were at high risk for delayed and missed care, which was associated with higher rates of non-COVID-19 mortality in the context of the pandemic (Smith et al., 2022[38]).

The prevalence of mental health symptoms, including anxiety and depression, during 2020 to 2022 remained heterogeneous, varying over time and between countries. Such symptoms were associated with the stringency of containment measures and the severity of the pandemic (Aknin et al., 2022[39]). The burden fell more heavily on young people and those with pre-existing vulnerabilities (see the chapter on mental health).

Three-quarters of OECD countries (20 of 26) responding to the OECD Resilience of Health Systems Questionnaire 2022 undertook mental health prevalence surveys during 2020-21. These included nationally representative surveys at several time points to collect up-to-date data on mental health issues, including anxiety and depression symptoms and psychological distress. Many of these surveys also included information about age, occupation, sex and gender, among other demographic variables relevant to understanding mental health impacts. Additionally, 19 of 26 reporting countries tracked the impact of COVID-19 on mental health service use and delivery.

All respondents (26 OECD countries) reported introducing emergency mental health support measures for the public during the pandemic. Furthermore, 25 of 26 OECD countries reported permanently increased mental health support or capacity since the pandemic began. Nonetheless, mental health in 2022 has not returned to pre-pandemic levels (see the chapter on mental health). This suggests that mental health services could not be scaled to the level required.

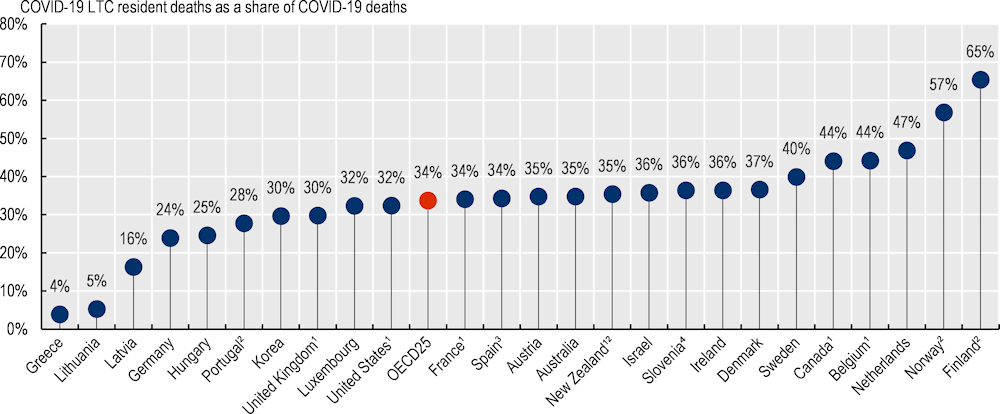

The long-term care (LTC) sector was hit hard by the pandemic, in terms of both the death toll and the number of people infected (workers and care recipients). The health and social costs were also substantial because of delayed or cancelled care, and because restrictions on visitation and movement generated negative mental and physical impacts for older people. Residents of LTC facilities were particularly affected in 2020 – the first year of the pandemic. Across 25 OECD countries, 34% of total COVID-19 deaths between 2020 and 2022 were among LTC residents (Figure 1.11).

Note: Data on cumulative deaths cover different periods: data cover up to May 2022 for eight countries and up to 2021 for the remaining countries, except for Israel (2020). 1. Includes confirmed and suspected COVID-19 deaths. 2. Only includes deaths occurring within LTC facilities, not those occurring after transfer to hospitals. 3. Data come from regional governments using different methodologies, some including suspected deaths. 4. Slovenia includes deaths in nursing homes and social LTC facilities.

Source: LTC COVID website, complemented with European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control data and data from the 2021 OECD Questionnaire on COVID-19 in LTC.

Just over 50% of OECD countries had guidelines on infection control in LTC facilities. This prevented early intervention, which would have been crucial to reducing mortality. Moreover, testing and access to PPE in the initial phases of the pandemic were not sufficiently prioritised for the LTC sector. On a scale of 1 (not an issue) to 5 (extremely challenging), OECD countries defined access to PPE as 3 and access to testing as 4 for the LTC sector.

Countries have sought to remedy these deficiencies. Maintaining high vaccination rates for this priority population is very important. In this respect, 60% of the 25 OECD countries that responded to the OECD Resilience of Health Systems Questionnaire 2022 introduced mandatory vaccination for LTC workers. Most reporting countries (19 of 23) also had testing policies for LTC workers. As a result of these policies, 86% of countries reported that low vaccination rates among LTC workers were not an important concern.

Efforts have also been made to improve care co-ordination. Since the pandemic began, eight OECD countries have introduced new measures to integrate more primary care into LTC facilities. In France, a new financial scheme has been set up to incentivise primary care doctors to visit LTC residents. Italy and Luxembourg now require nursing homes to have a 24/7 medical presence to ensure follow-up care of ill LTC residents (European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2020[40]).

A key lesson from the pandemic is that the recover stage is less arduous when the absorb stage is less severe. Furthermore, improved resilience and performance by health systems in the absorb stage reduces the length of the recover stage.

In 2023, OECD health systems were still recovering from the legacy of the pandemic. So far, this stage has been characterised by widespread vaccination, reduced containment and mitigation measures, and a return of resources to the usual functions of the health system. Delayed and deferred care is being addressed. However, the healthcare workforce is still under pressure. The impact of post-COVID-19 syndrome or "long COVID" remains a large and uncertain burden for health systems and society.

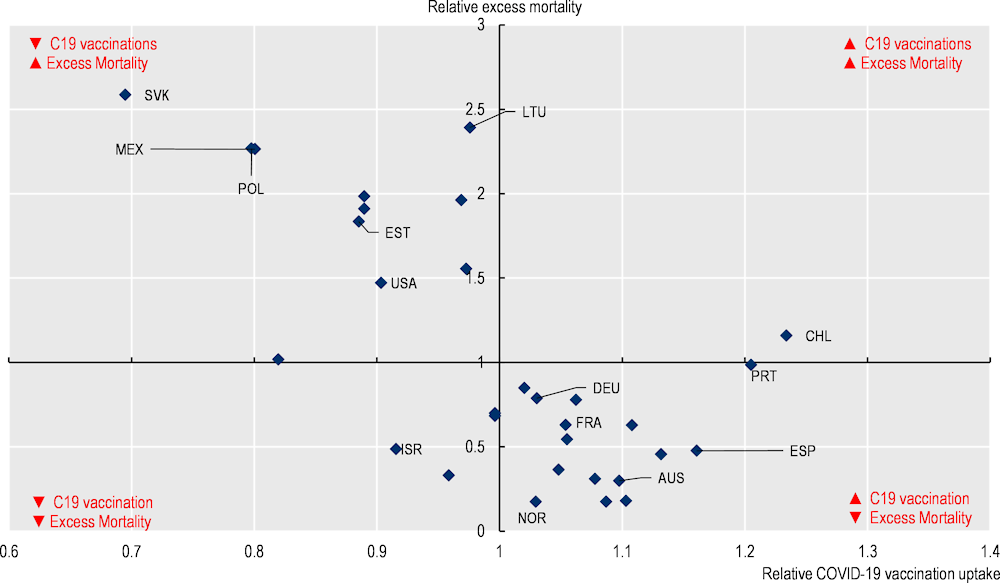

The rapid development, testing and rollout of COVID-19 vaccines was a success in transitioning to recovery for some countries. This was a game changer: increased vaccination rates were associated with decreased excess mortality through 2021 (Figure 1.12).

Note: The quadrant chart shows the association between vaccination rates and excess mortality. The x-axis shows how much a country is above or below the OECD average for completed initial vaccination schedules per 100 at the end of 2021; the y-axis shows a country’s distance from the OECD average excess mortality rate in 2021 (OECD average normalised to 1). Note that this analysis does not adjust for other factors; nor does it necessarily infer causality. Vaccination reported as of 31 December 2021 or nearest preceding date.

Source: OECD Health Statistics 2022 and OECD analysis of Our World in Data.

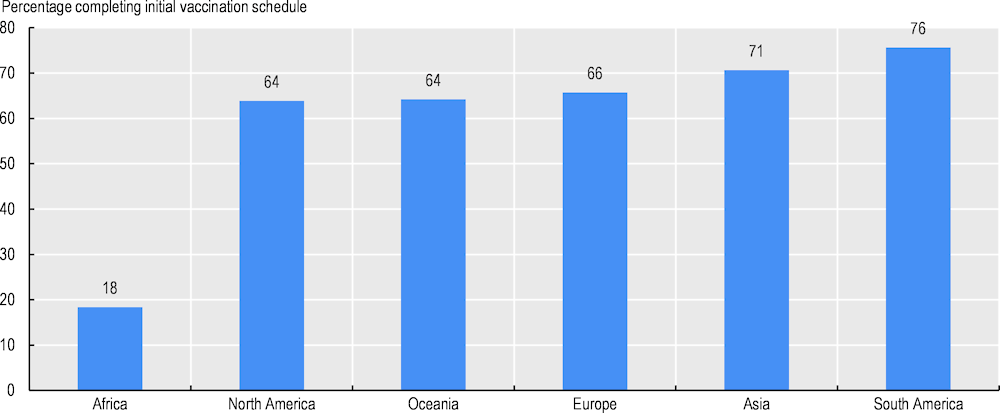

On an international level, however, trade restrictions and stockpiling have meant that available resources, such as vaccines, have not always been deployed to where they might have the most benefit. Production of vaccines is highly specialised and concentrated in a limited number of countries (OECD, 2021[41]).The global distribution of vaccines is inequitable (Figure 1.13), which increases the risk of new variants developing (OECD, 2021[42]).

Note: Number of completed initial vaccination schedules per hundred calculated on 25 June 2022 or the nearest preceding date.

Source: Mathieu et al. (2021[43]), “A global database of COVID-19 vaccinations”, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01122-8. Dataset available at Our World in Data.

Vaccine hesitancy and scepticism still have the potential to limit recovery from the pandemic, and to undermine the response to future outbreaks. Within OECD countries, those who have not been immunised have a more pronounced attitude against immunisation (Turner et al., 2022[44]). Enhancing public trust in COVID-19 vaccination remains important (Box 1.4).

COVID-19 vaccination was an example of a large-scale societal response. The effectiveness of that response relied on trust in vaccines – especially the ability of governments to communicate the benefits of COVID-19 vaccination and to deliver safe and efficacious vaccines (Allin et al., 2022[45]). Trust in vaccines also needed to be complemented by trust in the competence and reliability of those administering vaccinations and those deciding on vaccine procurement, distribution and prioritisation.

Vaccine hesitancy is not immutable. In the OECD Resilience of Health Systems Questionnaire 2022, 19 of 23 responding countries reported engaging with the media to combat misinformation and disinformation in the context of the pandemic. For example, the United Kingdom developed a suite of approaches to counter misinformation: a rapid respond unit to co-ordinate and support departments in tracking and devising responses; a counter-disinformation toolkit to assist public sector communication; and a training programme (OECD, 2021[17]).

Transparency and community engagement, especially with those segments of the population most hesitant to be vaccinated, also enhanced public trust in COVID-19 vaccination. The OECD has reported examples of good practices in public communications about the pandemic and responses to it (OECD, 2021[46]). These include leveraging the use of behavioural science to increase vaccine confidence in Canada, and partnering with social media influencers in Finland and Korea to share reliable information. In Portugal, patients were actively involved in decision making around COVID-19 vaccination campaigns through the inclusion of patient representative groups.

Communicating transparently both the risks and benefits of COVID-19 vaccination, and countering misinformation, will be important to a faster, sustained and equitable recovery from the pandemic’s unfinished legacy.

Promoting trust in actors in the health system is essential, especially when widespread health interventions may be needed for societies to absorb and recover from future challenges. Concerningly, trust in the healthcare system has fallen in some countries (Figure 1.14).

Source: Eurofound (2022) presented in de Bienassis (2023[47]), “Advancing patient safety governance in the COVID-19 response”, https://doi.org/10.1787/9b4a9484-en.

The absorb stage of the pandemic was characterised by a steep reduction in non-COVID-19 health system activity and then a rapid increase of this activity in some – but not all – countries. However, the follow-on effects from this initial reduction in non-COVID-19 activity persist. A loss of health may become permanent even with a return of healthcare activity if irreversible harm occurs or if the backlog of care is not eliminated (see chapters on waiting times and care continuity).

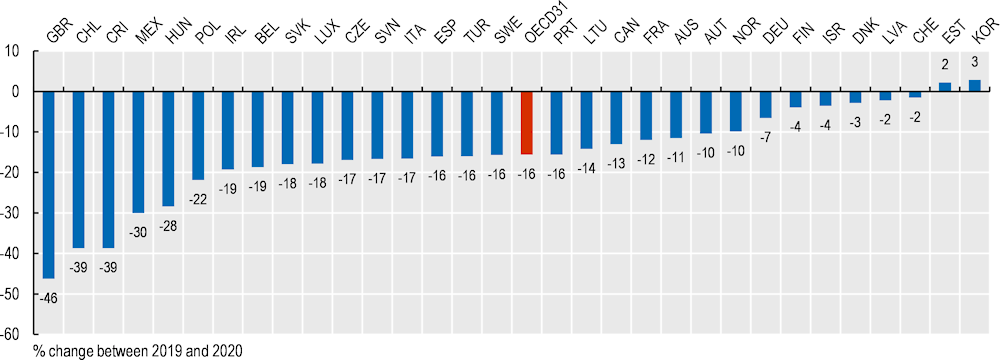

Across a selected set of diagnostic and surgical procedures in 31 OECD countries for which data are available there were:

four million fewer diagnostic (magnetic resonance imaging and computerised tomography scans) procedures performed in 2020 compared with 2019

seven million fewer elective surgical (cataract surgery, hip and knee replacement, and coronary angioplasty and bypass) procedures performed in 2020 compared with 2019.

The impact of the delayed and deferred care differed between countries, reflecting the duration and degree of disruption to health services and the speed of recovery. For example, some countries were able to maintain treatment activity for hip replacements in 2020, while others reduced activity by one-third (Figure 1.15).

Note: The OECD average is the total reduction across all OECD countries for which data are available.

Source: OECD (2022[3]), OECD Health Statistics, https://doi.org/10.1787/health-data-en.

Most countries (11 of 18) responding to the OECD Resilience of Health Systems Questionnaire 2022 reported that addressing waiting times for elective care was a high or medium-high priority. These include both countries that were hard hit by the pandemic and imposed strict confinement measures, and some other countries that were less hard hit (such as Australia and Finland). The Czech Republic, Luxembourg and the United States considered waiting times to be a low-to-medium priority issue.

A similar set of supply-side polices was introduced in most OECD countries to reduce backlogs in health care, involving additional funding, increased use of staff and resources, and the involvement of additional providers, such as private providers. Some approaches – for example, digital consultations – built on the experiences of telehealth during the absorb stage of the response to the pandemic.

Countries made efforts to improve the safety and well-being of health and long-term care workers after the pandemic began, as highlighted in section 1.4.6. The outcomes of these efforts should be reviewed, and consideration given to implementing effective programmes to promote sustained health and care worker well-being. The prevalence of mental health symptoms in the healthcare workforce is still high (Aymerich et al., 2022[35]). It represents a burden of recovery to be addressed.

Concerns remain that an exhausted health workforce could increase staff shortages. Existing shortages may result in higher numbers of resignations, exacerbating the situation. Responses to the United Kingdom’s National Health Service survey (one of the largest workforce surveys) show that motivation has declined, work pressure has increased, and more staff are thinking about leaving (NHS, 2022[48]). Interrupting the potential for a vicious cycle is crucial to resilient health systems (Abbasi, 2022[49]).

Data is vital to tackle the backlog in health treatment. Adequate disaggregated data on healthcare needs, prioritisation, waiting times and healthcare delivery are required for countries to move from the absorb to the recover stage. Without such data pre-existing inequities could worsen.

Some countries have implemented approaches to co-ordinate this information. For example, in England (United Kingdom), the Clinical Prioritisation Programme has published prioritisation frameworks for surgery, diagnostics and endoscopy to help manage waiting lists, promote their accuracy and ensure that priority is based on clinical need. These frameworks outline the steps for clinicians to check a patient’s condition, establish additional risk factors and understand treatment options (NHS, n.d.[50]).

New data and evidence-based insights will be needed to address the long-term implications of the pandemic, which are becoming increasingly evident. For example, information about the prevalence and consequences of long COVID is evolving. At the end of 2022, a lack of consistency in definitions of long COVID, limited national surveillance and different research approaches complicate international efforts (O’Mahoney et al., 2023[51]).The condition is defined by the WHO as a set of signs and symptoms that usually present within three months following SARS-CoV-2 infection and last for at least two months, in the absence of an alternative diagnosis (WHO, 2021[52]). Long COVID encompasses multiple adverse outcomes, with new-onset conditions including cardiovascular, thrombotic and cerebrovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, chronic fatigue syndrome, and dysautonomia. Estimates are that 10% or more of people infected with SARS-CoV-2 may have long COVID (Davis et al., 2023[53]); this would mean – on a conservative estimate – that at least 75 million individuals have long COVID based on total documented COVID-19 cases worldwide (WHO, 2023[1]). The number, however, is likely to be much higher owing to the significant number of undocumented cases.

Much as the burden of SARS-CoV-2 has been borne inequitably across the population, the risk of developing long COVID and experiencing more severe symptoms may also be distributed inequitably. For example, in a meta-analysis conducted in the United Kingdom, the odds ratio of people developing long COVID living in the most deprived area with confirmed or self-reported COVID-19 was 1.4 times as likely relative to people living in the least deprived area (OpenSAFELY Collaborative, 2022[54]).

High-quality and timely data on health, well-being and employment are key to understanding and meeting this challenge in the coming years. Future shocks, which may not take the form of another pandemic, will bring new information and data challenges. It is essential that the digital foundations of the health system (and beyond) are adaptable to generate useful information for decision making.

Increasing stresses are buffeting health systems as 2023 begins. These stresses may reduce the performance of health systems. Backlogs, delayed and deferred care (including preventive care), and an exhausted workforce are complicated by the addition of over a million new reported cases of SARS-CoV-2 a week, as at the end of 2022 (WHO, 2023[1]). The implications of long COVID are still emerging. A cost-of-living crisis complicates these stresses (Goddard, 2022[55]).

The worst-case scenario of a more deadly SARS-CoV-2 variant may not occur. Nonetheless, additional critical care surge capacity for continuing SARS-CoV-2 infections is likely to be needed. This may be especially important during winter months, when reduced physical distancing and more frequent presence in enclosed spaces with poor ventilation increases the potential for large numbers of patients infected with either influenza or SARS-CoV-2, or both. Health systems unable to generate this capacity may be at risk of failure and worse outcomes.

The morbidity impacts of long COVID are concerning - and for some people may last for years (Davis et al., 2023[53]) - but they are not known with certainty. Increasing long-term morbidity from SARS-CoV-2 infections, alongside acute infections, will increase demand for health services, reducing spare capacity in health systems and making them vulnerable.

The disruption to health services, and especially hospital care, is still reverberating. Hospitals are seeing more high acuity, in patient cases than they were prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. A lack of preventive care and disrupted care may increase the severity and prevalence of chronic diseases in the population (see the chapter on care continuity). Sicker patients, combined with workforce shortages, are reported to have resulted in increases in the average length of stay in hospitals in the United States (Kaufman Hall, 2022[56]). This situation increases demand and reduces spare capacity in the health system. If appropriate preventive and primary care cannot be scaled up, this may result in a vicious cycle where the resources required for higher-acuity patients reduce the resources for preventive and primary care.

A safe clinical environment, given SARS-CoV-2 is still present, requires additional cleaning and additional space (for physical distancing). Hospitals face more costs than before the pandemic for PPE, and other medical and safety supplies need to care for higher acuity patients (Kaufman Hall, 2021[57]). The health system will need greater resources to undertake the same level of activity. Without such resources, performance will fall, albeit improved infection control may reduce other infectious complications associated with health care.

The long-term economic implications of long COVID are uncertain but some predications are alarming (Cutler, 2022[58]). Long COVID may reduce labour participation; some estimates are that substantial numbers of individuals with long COVID are unable to return to work or to undertake their prior workload. For example, it has been estimated that more than 1 million people may be out of the United States workforce at any given time because of long COVID (Bach, 2022[59]). People out of the workforce because of long COVID disproportionately worked in service jobs, including health care and social care (Cutler, 2022[58]). Long COVID in the health workforce may result in fewer staff and a need for higher staff numbers – absent this, health system performance and efficiency will fall.

A decline in real income associated with long COVID and the cost-of-living crisis could place more pressure on health systems funded by out-of-pocket costs. For publicly funded systems, decreased labour participation and increased costs would place pressure on financing attained through taxation. Funding pressures from decreased income and taxes will reduce the sustainability of health systems.

Health system resilience requires stakeholders to deal with a different set of challenges during the recover stage than during the absorb stage of a large-scale shock. However, there are some commonalities, including: understanding the interdependencies within and beyond the health system; adequate resourcing; quality and timely data on which to make well-informed decisions; and the agility to respond effectively and as quickly as possible.

Not being sufficiently prepared for a shock like the COVID-19 pandemic results in costly interventions when crises occur that have repercussions for years to come. With a large shock there may not be a return to normal. Shocks and the response to them leave a legacy of new challenges and impacts on resilience.

It is essential to include health system resilience as an explicit goal and to integrate the pursuit of resilience into planning. The tools to be resilient need to be given to health systems; these include not only investments but also the means to incentivise future development of key technologies, such as vaccinations and treatments (see the chapter on global public goods).

Planning health system resilience should be undertaken as a goal for societies and health systems. This needs to be operationalised within a framework, including the development of measurement tools and indicators of resilience, so that useful information can be generated to inform decision making.

The relationship between resilience and efficiency can be complicated. Some policies may improve both – for example, better use of data and elimination of low-value care improves efficiency and resilience. However, trade-offs can exist (Almeida, 2023[60]). Systems running close to capacity can improve short-term efficiency but at the expense of resilience (as with the high occupancy levels in hospitals, especially intensive care units, seen in some countries before the pandemic began). Incentives that prioritise low-cost provision of services may not make sufficient allowance for resilience (for example, supply chains incentivised by low costs and generic pharmaceuticals). The balance between resilience and efficiency should maximise societal benefit, and both should be included in health system performance frameworks and inform decision making.

While specific threats – such as pandemics – should be examined, the approach to health system resilience should be wider and cover all hazards. Multiple different shocks and threats should be considered and reviewed. For example, the OECD has issued guidance for support on climate resilience, including to encourage sector-level (such as health system-specific) approaches to identifying climate risks and ensuring that sector-specific policies and actions are climate resilient (OECD, 2021[61]). Regular review of the approaches undertaken, and testing of their effectiveness, would also be useful. Resilience testing of health systems should be considered.

Learning from the gaps and difficulties highlighted by the pandemic will be important - all countries should undertake such a process. The relationship between public health functions and the wider functions of the health system should be strengthened, based on reviews of pandemic experiences across countries.

Care should be taken to ensure that important non-health systems, such as social care and manufacturing, are regularly included in the analyses. Sufficiently large shocks necessitate a whole-of-society approach with national leadership. Reflecting the complex interdependencies and feedback loops beyond health will be required (Smaggus et al., 2021[62]). The results should be used to update governance, regulatory, investment, financing and funding decisions, including those suggested in this report.

This report recommends the promotion of six policy areas to improve health system resilience: the health of the population; workforce retention and recruitment; data collection and use; international co-operation; supply chain resilience; governance and trust. These recommendations will have the optimal impact if implemented together.

A healthier population improves health system resilience. An approach using multiple policies to increase health coverage, promote healthier lifestyles and reduce the potential for one policy failure to result in harm would be beneficial. Ensuring disease prevention through public health, reinforcing the centrality of primary care, and increasing mental health services would improve the health of the population prior to a crisis occurring. Achieving this will require additional investments in public health and primary care. Tackling the socio-economic determinants of health would improve resilience by lowering vulnerability to future shocks.

Populations with less multimorbidity may be less prone to permanent health loss associated with interrupted treatment. Increased prioritisation may be needed during times of crisis to ensure that services are allocated where they will be most effective. In this respect, better data would improve the evidence base for these allocations.

Many changes were made after the COVID-19 pandemic began to ensure continuity in services. The strengths and weaknesses of these changes need to be assessed for their contribution to efficiency, equity and resilience. Without assessment, weakness and adverse unintended consequences could be perpetuated.

At the local level, promoting the health of the population requires models of integrated care, focused on improving patient health. These models can be useful during times of crisis. Generating the flexibility to respond to evolving requirements at a local level would improve the resilience of health systems across all stages of the disruption cycle. Generating this flexibility requires many changes: physical infrastructure for different models of care (e.g. telehealth); data systems that deliver useful information and allow the data to “follow the patient”; an adaptable workforce; and incentives and governance to support co-ordination, sustainability and care integration.

Residents of LTC facilities were particularly vulnerable to the COVID-19 pandemic. This vulnerability will also be evident in response to other shocks, such as climate change. While many measures are being taken to improve the performance of the LTC sector, more needs to be done. Ensuring LTC preparedness for health emergencies requires regular, granular assessments of preparedness. Solutions need to be found for safe visits and to safeguard continuity of care. Transparent communication plans with families of LTC residents should be part of the solution. Co-ordination with primary and secondary care remain essential. Adequate staffing is important, and additional workers are required in the LTC sector.

Across the health system, resilience requires information and resources, accompanied by an appropriate governance, data and regulatory environment. Co-operation and co-ordination are required to ensure the most effective use of resources during the absorb and recover stages. The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated that a health system must be able to react dynamically to a multitude of different challenges. Adaptability of roles and movement of resources to where they could best be used were crucial in the pandemic response. The move to telehealth, alongside changes in regulations and funding, was one example. Increasing universal health coverage and ensuring low or no user charges was important in delivering care, and giving options for the model of care delivery, in response to the pandemic. Better-performing health systems were those in which a greater portion of the population was covered by health insurance (see the chapter on COVID-19 outcomes).

Investing in population health and prevention not only improves health system resilience but is also a cost-effective way of improving health (OECD, 2019[63]).

Staff, supplies and space were limited for the critical care surge response (see chapters on critical care, workforce and securing supply chains). Existing health workforce shortages in many countries suggest that increasing efforts from these workers is not a sustainable solution except in the very short-term. Greater investments in the number of healthcare workers and in workforce flexibility are required.

Many OECD countries have begun implementing measures to increase and sustain the supply of healthcare workers. These measures include increasing training and recruitment of new staff, improving retention and redesigning service delivery. Responses to the OECD Resilience of Health Systems Questionnaire 2022 demonstrated that most countries (16 of 20) increased student intake and increased incentives to encourage more doctors to choose general practice. Most countries (12 of 20) plan to expand roles to relieve pressure on medical practitioners, and some (8 of 20) plan to introduce financial incentives to improve the geographical distribution of doctors. One-quarter of respondents reported having targeted immigration policies to attract foreign health workers. These policy changes will be beneficial in the long-term, but health systems will remain vulnerable until trainees join the workforce.