This chapter covers the case study of the Danish Whole Grain Partnership, a public-private partnership that aims to increase average daily intake of whole grains in the population. The case study includes an assessment of the Danish Whole Grain Partnership against the five best practice criteria, policy options to enhance performance and an assessment of its transferability to other OECD and EU27 countries.

Healthy Eating and Active Lifestyles

9. The Danish Whole Grain Partnership

Abstract

The Danish Whole Grain Partnership: Case study overview

Description: the Danish Whole Grain Partnership (DWGP) is a public-private partnership (PPP) between the Danish Veterinary and Food Administration (government), the Danish Cancer Society, the Danish Heart Foundation and the Danish Diabetes Association as well as a number of food companies. The overall objective of DWGP is to increase average daily intake of whole grain in the population. A key element of DWGP is the logo its member use on high whole grain products and is the focus of this case study.

Best practice assessment:

Table 9.1. OECD best practice assessment of the Danish Whole Grain Partnership

|

Criteria |

Assessment |

|---|---|

|

Effectiveness |

DWGP is associated with an increase in whole grain consumption across sex and age groups. |

|

Efficiency |

Studies measuring efficiency of DWGP are not available, however, meeting the whole grain consumption threshold, which DWGP aims to do, is associated with significant health care cost and labour productivity savings. |

|

Equity |

The design of the DWGP logo makes it accessible to different population groups, however, it is unclear whether these products are more expensive. |

|

Evidence‑base |

Changes in whole grain consumption were measured using cohort studies, which aren’t necessarily generalisable. The evidence‑base supporting the association between whole grain consumption and certain diseases, risk factors and mortality is well-established. |

|

Extent of coverage |

Extent of coverage has grown significantly since DWGP’s inception – between 2011 and 2019, the proportion of people buying products with the logo increased from 40% to 80%. |

Enhancement options: to enhance effectiveness and equity, policy makers could consider options such as partnering with retail outlets to offer discounts/promotions on products carrying the DWGP logo. To enhance the evidence‑base, analysing the impact of DWGP beyond sex and age group (e.g. by socio‑economic group) will provide a better understanding its impact on different populations. To enhance the extent of coverage, policy makers may want to consider offering small producers incentives to become a DWGP member.

Transferability: in 2019 the “European Action on Whole Grain Partnerships” was created, which involves transferring DWGP Denmark to three new countries. Materials to assist countries implement the Partnership were created as part of the Action. Publically available data to measure the transferability potential of DWGP is limited, given indicators on the food retail market and consumer behaviour are collected by private research companies and thus not available for public use. Data that was available indicate DWGP would receive significant political support in other OECD and non-OECD European countries.

Conclusion: DWGP uses a multi-pronged strategy to boost whole grain consumption, including an easy-to‑understand logo. Since DWGP’s inception, whole grain consumption in Denmark has increased markedly. To enhance the performance of DWGP, policy makers could consider options outlined in this case study such as offering discounts/promotions on DWGP products.

Intervention description

A Global Burden of Disease Study released in 2018 estimated that between 2007 and 2017 the number of deaths attributed to insufficient whole grain consumption increased by about 17%, from 2.63 million to 3.07 million deaths (Stanaway et al., 2018[1]). Consequently, insufficient whole grain consumption became the second leading dietary risk factor for population health behind high sodium consumption (Stanaway et al., 2018[1]).

Persistently low rates of whole grain consumption have prompted policy makers across the world to act, including Denmark (Lourenço et al., 2019[2]). In Denmark, findings showing increased levels of fat in the population’s diet and a decline in bread consumption (caused by growing popularity in a diet promoting low levels of carbohydrates) led to discussions between the Danish Veterinary and Food Administration, the food industry and non-governmental health organisations (NGOs) on how to boost whole grain consumption (Fuldkorn, 2020[3]). Following these discussion, in 2008, the National Food Institute within the Technical University of Denmark released a report defining what is considered a whole grain product1 and a scientifically based whole grain consumption recommendation of 75g / 10 megajoules (mJ) per day (DTU Fødevareinstituttet, 2008[4]).

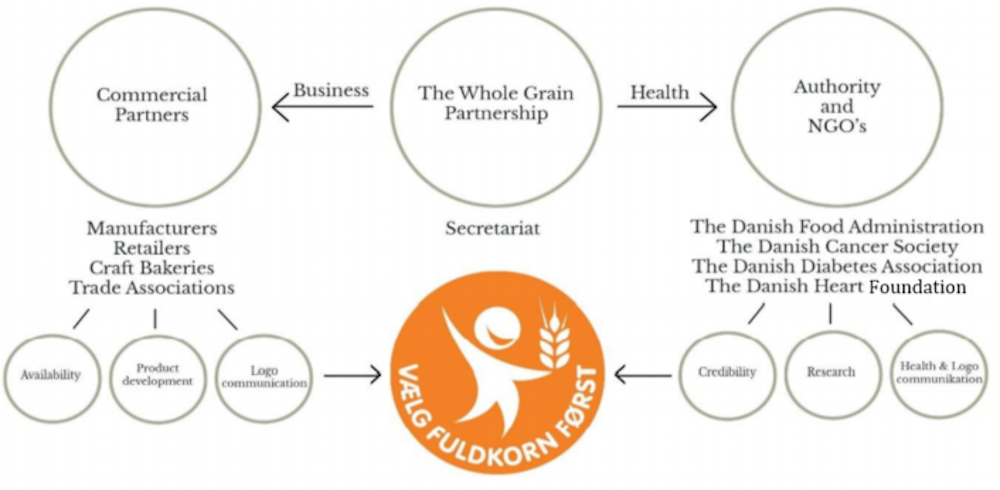

The adoption of the recommended consumption of whole grains into national dietary guidelines led to the establishment of the Danish Whole Grain Partnership (DWGP) in 2008. DWGP is a public-private partnership (PPP) between the Danish Veterinary and Food Administration (government), the Danish Cancers, the Danish Heart Foundation and the Danish Diabetes Association as well as a number of commercial partners such as food manufacturers and retailers (Figure 9.1).

Figure 9.1. Structural overview of the Danish Whole Grain Partnership

Note: The wording in the orange logo translates to “Choose whole grains first”.

Source: WholEUGrain (2021[5]), “Toolbox: A guide to implement a successful national whole grain partnership”, https://www.gzs.si/Portals/288/Toolbox_opdateret%2009082021.pdf.

The main objective DWGP is to increase the average daily intake of whole grain in the population. The Partnership achieves this by employing a multi-pronged strategy (Lourenço et al., 2019[2]):

Increasing the availability of “tasty” whole grain products, for example by adding small amounts (5‑20%) of whole grain to relevant products.

Promoting the development of whole grain products and incorporating whole grains in all cereal-based products

Promoting the whole grain logo (see below for further details), informing people about the health benefits of whole grains as well as dispelling myths regarding whole grains

Helping shape new norms for whole grains via campaigns, events and structural changes.

The whole grain logo – pictured in Figure 9.1 – (“choose whole grains first”) – represents a key pillar of the Partnership. The logo is printed on products developed by DWGP members given they meet minimum whole grain requirements (Table 9.2) as well as wider dietary requirements outlined within the Nordic Keyhole labelling scheme. That products must meet both the DWGP and Keyhole requirements is a key strength of the intervention as it limits unintended consequences arising from the “halo effect” (see Box 9.1).

Table 9.2. Whole Grain Partnership logo requirements (examples)

|

Breakfast cereals and muesli |

Rice |

Pasta and noodles |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Whole grain (calculated as product dry matter) |

At least 65% whole grain |

100% whole grain |

At least 60% whole grain |

|

Fat |

Max 8g/100g |

- |

- |

|

Sugars |

Max 13g/100g |

- |

- |

|

Added sugars |

Max 9g/100g |

- |

- |

|

Dietary fibre |

At least 6g/100g |

At least 3g/100g |

At least 6g/100g |

|

Salt |

Max 1.0g/100g |

- |

Max 0.1g/100g |

Source: Fuldkorn (2020[6]), “The Whole Grain Logo Manual: Guidelines for use of the Danish Whole Grain Logo””, https://fuldkorn.dk/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Fuldkornslogomanualen_revideret-udgave_gældende-fra-5.-maj-2020-31.-december-2022_English.pdf.

Box 9.1. Food labelling and the “halo effect”

The halo effect refers to the tendency for people to overestimate the “healthfulness” of a product based on a single labelling claim (Cecchini and Warin, 2015[7]). For example, research has shown that consumers often confuse “low fat” products with “low calorie” products (Brownell and Koplan, 2011[8]), which may result in an increase in overall calorie consumption. The requirement that products with the Whole Grain logo also meet nutrition guidelines outlined by the Nordic Keyhole labelling scheme prevents “unhealthy” high whole grain products using the logo (Health Norway, 2019[9]).

In order to become a partner, organisations pay a fee, which is dependent on their size.2 At present, DWGP includes 30 partners ranging from manufacturers in the food industry, retailers, Danish Veterinary and Food Administration, craft bakers, millers, associations and non-government health organisations (health NGOs) (Fuldkorn, 2020[6]).

OECD Best Practices Framework assessment

This section analyses DWGP against the five criteria within OECD’s Best Practice Identification Framework – Effectiveness, Efficiency, Equity, Evidence‑base and Extent of coverage (see Box 9.2 for a high-level assessment). Further details on the OECD Framework can be found in Annex A.

Box 9.2. Assessment of the Danish Whole Grain Partnership

Effectiveness

Whole grain consumption has increased in Denmark since the inception of DWGP – for example between 2000‑04 and 2011‑12, consumption of whole grains in grammes per day increased by 64% and 71% for men and women, respectively.

Using latest available estimates, the median intake of whole grain is above the recommended threshold (75g/10 mega joule), with 50% of the population meeting this threshold

Efficiency

Studies measuring efficiency of DWGP are not available. A study by the University of Copenhagen found that increasing whole grain consumption to the recommended level would lead to significant health care cost savings and improvements in labour force productivity.

Equity

There is some evidence to suggest that pre‑packaged food products with a healthy label (or, in general, foods perceived as healthy) are more expensive. For example, in Romania (a country that will adopt DWGP) products high in whole grain are more expensive than refined grain products. However, this is not the case in Denmark.

Evidence‑base

In 2000‑04 and 2011‑12, whole grain consumption was measured using data from the Danish diet and physical activity survey, while data for 2015‑19 was obtained from the Diet, Cancer and Health (DCH) – Next Generation (NG) cohort study

It is likely that people with a high socio‑economic status are over-represented in DCH-NG limiting the generalisability of results. Further, the data is cross-sectional meaning there is no data on whole grain consumption for the same participants before DWGP was established

The evidence‑base supporting the association between whole grain consumption and certain diseases, risk factors and overall mortality is well-established

Extent of coverage

Extent of coverage has grown significantly since DWGP’s inception – for example, the number of products with the logo increased from 157 to 987 (2009‑20), which may in part explain a rise in the number of consumers who are aware of the logo (from 20% to 64% over a similar period)

Effectiveness

DWGP is considered one of the most successful interventions for boosting whole grain consumption, which can be classified in one of two ways (see Box 9.3).

Box 9.3. Defining whole grain consumption

Whole grains can be quantified as either grammes per day or grammes of product per day. The generally accepted portion size is 16 g/day or 30g product/day. For example, if a person consumes one slice of whole grain bread (50g) containing 50% whole grains, then the intake will be 25g whole grains or 50g whole grain product.

Energy intake differs across age groups and genders. For this reason, comparing whole grain consumption across population groups in grammes per day is not appropriate. Instead, whole grain consumption is translated into grammes per 10 megajoules (MJ) to reflect similar energy intakes. It is recommended people consume at least 75g/10 MJ of whole grains per day.

Source: Kryø and Tjønneland (2016[10]), “Whole grains and public health”, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i3046; Ross et al. (2015[11]), “Recommendations for reporting whole‑grain intake in observational and intervention studies”, https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.114.098046.

Since the introduction of DWGP, consumption of whole grain has increased for children and adults. The evolution of whole grain consumption has been studied using data from a nationally representative survey on diet and physical activity in Denmark and a cohort study.

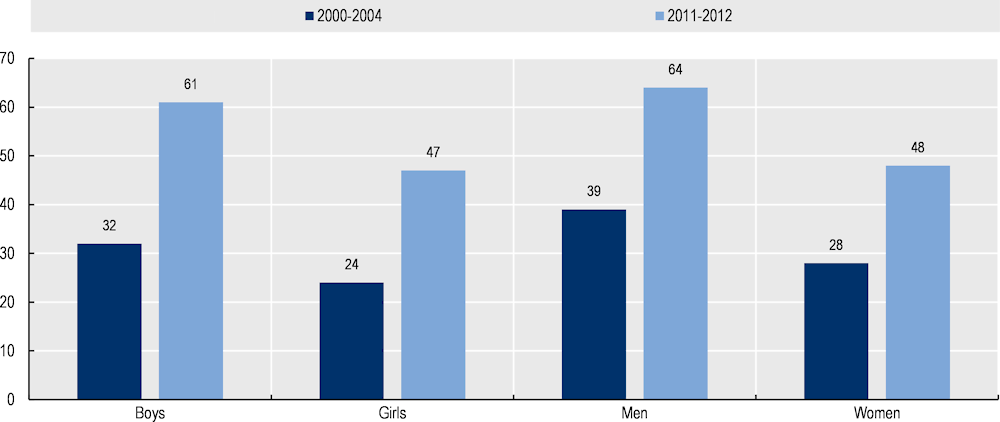

Results from the data show consumption of whole grain increased between the period 2000‑04 and 2011‑12 for both men and women – specifically, from 39 to 64 grammes/day for men and from 28 to 48 grammes/day for women (Figure 9.2) (Mejborn et al., 2013[12]).

Mejborn et al. (2013[12]), using 2011‑12 data, also measured whole grain consumption in grammes per 10 MJ. The study found that the total population on average consumed 60g/10 MJ of whole grains per day and that 27% of the population met the recommended 75g threshold. Since then, whole grain consumption has increased markedly with 54% of the population now meeting the recommended whole grain consumption threshold (Andersen et al., 2020[13]).

Figure 9.2. Change in whole grain consumption (g/day) – 2000‑04 and 2011‑12

Note: Figures for boys and girls in 2011‑12 may be overestimated as it excludes younger children which were included in 2000‑04 (as younger children consume less whole grains in total).

Source: Mejborn et al. (2013[12]), “Wholegrain intake of Danes 2011‑12”.

Results from these studies have led external researchers to conclude that DWGP is one of the “most successful intervention[s] to increase WG [whole grain] consumption” (Suthers, Broom and Beck, 2018[14]). Further, whole grain consumption in Denmark is now one of the highest in the OECD (Table 9.3).

Table 9.3. Mean whole grain intake in g/day for adults in selected OECD countries

|

Country |

Mean whole grain intake (g/day) |

Year |

Population |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Denmark |

58 |

2011‑12 |

Men and women, 15‑75 years |

|

Sweden |

58 |

1992‑96 |

Men, 30‑60 years |

|

Norway |

51 |

1998 |

Women, 40‑55 |

|

Sweden |

41 |

1992‑96 |

Women, 30‑60 years |

|

Ireland |

29.4 |

2008‑10 |

Men and women, 18+ |

|

United Kingdom |

26.2 |

2008‑11 |

Men and women, 18+ |

|

United States |

15.5 |

2011‑12 |

Men and women, 19+ |

|

France |

4.7 |

2009‑10 |

Men and women, 18+ |

|

Italy |

3.8 |

2005‑06 |

Men and women, 18‑64 |

Source: Landberg and Scheers (2021[15]), “Whole Grains and Health”.

Efficiency

Meeting recommended levels of whole grain consumption leads to health care savings and improves labour force productivity

The efficiency of DWGP has not been estimated, however, studies indicate there are high costs associated with insufficient whole grain consumption. A study by the University of Copenhagen (2020[16]) estimated the annual economic impact if Danes met the recommended 75g/10 MJ per day of whole grains. The results found meeting this threshold would lead to:

129 million Danish Krone (DKK) (EUR 17.35 million) saved in health care costs

DKK 1 239 million (EUR 167 million) reduction in lost labour productivity

DKK 1 185 million (EUR 159 million) reduction in the loss of life quality.

Studies on the cost of failing to meet whole grain consumption are also available, however, they are not specific to Denmark. For example, Lieffers et al. (2018[17]) estimated the cost of failing to meet recommended whole grain consumption in Canada at CAD 3.27 billion (EUR 2.21 billion) per year, which covers both direct and indirect costs of associated chronic conditions such as ischemic heart disease, stroke and diabetes (Lieffers et al., 2018[17]).

Equity

Whole grain intake is lower amongst disadvantaged groups, which may reflect lower levels of access to nutritious products

Whole grain intake is lower among people with lower education levels and worse risk factors. In 2020, Andersen et al. (2020[13]) compared whole grain intake among different population groups in a Danish cohort. Results from the analysis indicate less advantaged groups in society consume lower levels of whole grain, specifically:

Those with a “long education” (e.g. MSc or higher university degree) were 20% more likely to meet recommended whole grain intake levels compared to those with a “short education” (e.g. primary school, high school or a short course)

Those who are obese are 39% less likely to meet recommended whole grain intake levels compared to those with a normal weight.

Findings from the literature indicate less advantaged groups have lower levels of access to nutritious foods. The DWGP logo is displayed on products that meet pre‑defined dietary requirements. The logo has a simple design and message (“Choose whole grains first”) (Figure 9.1) and is therefore easily interpretable by the wider population. The costs of applying the logo to products high in whole grain are not explicitly passed onto consumers. Nevertheless, international studies into the difference in price between products with and without health logos indicate the former can be more expensive, which exacerbates existing health inequities. For example:

Research undertaken in Canada found bread products with a front-of-package whole grain label were 74% less likely to be found in the lower price range (i.e. bread below CAD 3.00 per loaf) (Sumanac, Mendelson and Tarasuk, 2013[18]).

In Romania, a country in the process of adopting the Whole Grain Partnership, research has shown that whole grain products are more expensive the refined grain products. It is important to note that in Denmark, there is no evidence to suggest that products with the whole grain logo are systematically more expensive than substitute products without the logo.

Higher prices of foods with health labels may reflect a higher willingness-to-pay amongst consumers for “healthier” products and/or greater production costs (e.g. breads high in whole grain take longer to bake and have a shorter shelf life) (Sumanac, Mendelson and Tarasuk, 2013[18]; Van Loo et al., 2011[19]). Access to high whole grain products by lower income groups may be further curtailed if food stores sell a lower number of high whole grain products. For example, research has found lower-income neighbourhoods have less access to nutritious foods (Larson, Story and Nelson, 2009[20]). A report analysing availability of products with the Whole Grain logo is not available in Denmark, however, feedback from DWGP indicate such products are sold in a variety of stores across the country, including discount stores and retail chains.

It is important to note that DWGP also aims to increase whole grain content in foods that do not have the logo. Therefore, all groups in society, regardless of their attitude towards healthy eating, stand to benefit from DWGP.

Evidence‑base

Whole grain consumption at the population level relied on data from cohort studies, which have their limitations. The evidence supporting the health impact of whole grain consumption is well established

Two different surveys were used to collect data on whole grain consumption. Data to measure the level of whole grain intake within the Danish population has been measured for periods 2000‑04, 2011‑12 and 2015‑19 (see “Effectiveness”). Data for the first two observations (i.e. period 2000‑04 and 2011‑12) were based on data from the nationally representative Danish diet and physical activity survey. Conversely, measures of whole grain intake in the period 2015‑19 were measured by the Danish Cancer Society using data from the Diet, Cancer and Health – Next Generation (DCH-NG) cohort study (Andersen et al., 2020[13]). The focus of the evidence‑based assessment is on the latest study from the Danish Cancer Society.

The DCH-NG cohort study includes data from men and women above the age of 18 who are descendants of participants of the preceding DCH cohort. In total 183 764 people were eligible for the study and 38 553 agreed to participate.

Consumption of whole grain was measured using the food-frequency questionnaire. To measure whole grain intake, survey participants completed a 376‑item food-frequency questionnaire (FFQ), which is considered a reliable and valid measurement tool. The questionnaire asked participants to state average daily intake of each food and beverage item over the past year ranging from never to eight or more times per day. The intake of whole grain was estimated by multiplying consumption frequency of whole grain foods by a standardised portion size, which has a pre‑defined whole grain intake (obtained from the Danish National Food Institute, Technical University of Denmark).

Limitations associated with DCH-NG data to measure whole grain consumption are summarised below:

Cohort studies, such as DCH, are overrepresented by individuals with a high socio‑economic status (SES). Therefore, it is possible that high DCH-NG cohort also includes a disproportionate number of people with a high SES, who have the knowledge and resources to lead healthy lifestyles (Andersen et al., 2020[13]).

DCH data is cross-sectional therefore there is no information on whole grain consumption for the same population group prior to the establishment of the Partnership.

The evidence‑base supporting the relationship between whole grain intake cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), cancer, type 2 diabetes, overweight and overall mortality is well established and summarised in a document developed as part of the WholEUGrain project (see Box 9.4 for further details) (WholEUGrain, 2021[21]).

Box 9.4. Evidence supporting the association between whole grains and diseases, risk factors and mortality

The evidence base associating whole grains with CVDs (coronary heart diseases, stroke, heart failure and overall CVD risk), type 2 diabetes, cancer (e.g. breast and gastrointestinal cancers), mortality and overweight was summarised in a report developed as part of the WholEUGrain project. A selection of findings are outlined below:

The relative risk of developing coronary heart disease is 21% lower for those who consume high levels of whole grain

Those who consume a diet high in whole grain have a 21‑33% lower risk of developing type 2 diabetes

To date, the evidence supporting a protective role of whole grains in regard to weight gain, overweight and obesity is limited, but in general, there is a small inverse relationship.

As part of the report, the authors undertook an umbrella review based on systematic reviews and meta‑analyses from prospective cohort studies as well as randomised controlled trials.

Source: Chapter 3 of WholEUGrain (2021[21]), “WholEUGrain project: a European Action on Whole Grain Partnerships – Deliverable number 4.1 (evidence base for the health benefits of whole grains including sustainability aspects)”, https://www.gzs.si/Portals/288/210427_WholEUGrain_Deliverable%204.1_FINAL%20report.pdf.

Extent of coverage

DWGP’s extent of coverage has grown significantly since its inception

Key indicators reflecting the reach of DWGP are summarised below:3

The number of products with the whole grain logo increased from 150 to 987 between 2009‑20

Consumer awareness of the logo increased from around 20% to 64% between 2009 and 2019

The proportion of people who buy products with the logo increased from 40% to 80% between 2011 and 2019

The number of DWGP members increased from 18 to 30 between 2009 and 2020.

Policy options to enhance performance

DWGP is a world-renowned intervention for boosting whole grain consumption. A 2018 systematic review into public health interventions aimed at increasing whole grain intake concluded DWGP was the “most successful” (Suthers, Broom and Beck, 2018[14]). Further, Curtain et al. in (2020[22]) noted Denmark was one of few nations to markedly increase whole grain consumption as a result of DWGP.

The success of DWGP is not attributable to a single characteristic, rather a suite of characteristics considered essential for boosting whole grain consumption. For example, there are a range of activities involved in the Partnership including marketing campaigns; there are a comprehensive group of stakeholders involved, which increases the availability of whole grain products; the logo is placed on the front of the package and is colourful and easy to interpret; in addition, DWGP also aims to increase whole grain content in foods without the logo.

To further enhance DWGP’s performance, several policy options have been listed. Policy options may target DWGP administrators or other policy makers (e.g. at the national level) where proposed changes fall outside the scope of day-to-day administrators.

Each of the policy options align with high-level recommendations outlined by the European Commission (Box 9.5).

Box 9.5. European Commission policy recommendations to address whole grain intake

To boost whole grain consumption, the European Commission have outlined three high-level policy recommendations:

Increase the awareness of consumers regarding the benefits of whole grain and also provide information on how to recognise the appropriate products

Make the healthy option available by improving the food environment (e.g. increasing availability)

Implement financial incentives to promote the purchase of healthful foodstuffs by consumers.

Note: The first two recommendations are currently in place as part of DWGP.

Source: European Commission (2020[23]), “Whole grain”, https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/en/health-knowledge-gateway/promotion-prevention/nutrition/whole-grain#.

Enhancing effectiveness

Improve health literacy levels. Research has shown that low rates of health literacy reduce understanding of nutrition-related information (Campos, Doxey and Hammond, 2011[24]). A nation-wide study of health literacy in Denmark revealed approximately 40% of the population have either inadequate or problematic health literacy. When adjusting for confounders, those in the following groups have higher odds of inadequate health literacy: men, young people, immigrants, and individuals with a basic education and below average income (Svendsen et al., 2020[25]). To enhance the effectiveness of the DWGP logo, efforts to enhance health literacy (with a focus on nutritional knowledge), particularly among vulnerable groups, are encouraged (OECD, 2019[26]). Example policies to boost health literacy are outlined in Box 9.6.

Box 9.6. Boosting rates of health literacy

In 2018, OECD released the Health Working Paper “Health literacy for people‑centred care”. The paper outlined high-level policy options to boost population health literacy such as:

Counselling and training interventions in community settings and elsewhere (e.g. workplaces);

Encouraging health literacy in schools, for example by incorporating health literacy into the education curricula;

Media campaigns and website that promote health literacy that are easy to access and navigate.

Source: Moreira (2018[27]), “Health literacy for people‑centred care: Where do OECD countries stand?”, https://doi.org/10.1787/d8494d3a-en.

Increasing the number of producers signed up to DWGP will also enhance the intervention’s effectiveness, as explored under “Enhancing extent of coverage”.

Enhancing efficiency

Efficiency is calculated by obtaining information on effectiveness and expressing it in relation to inputs used. Therefore policies to boost effectiveness without significant increases in costs will have a positive impact on efficiency.

Enhancing equity

Implement strategies to increase affordability. The rise of cheap foods low in nutritional value has contributed to higher rates of overweight and obesity in poorer populations (e.g. in Denmark, 14.3% of the population are obese in the lowest income quintile compared to 11.4% in the highest income quintile) (Eurostat, 2014[28]). To improve access to high whole grain foods, policies that reduce the price of products with the whole grain logo could be considered, as has been done in other countries. For example:

Singapore: In Singapore, the Health Promotion Board (a government organisation promoting healthy living) partnered with supermarkets to provide discounts on brown rice and to encourage price competition. Over a period of three years, brown rice sales increased by 15% (Toups, 2020[29]).

South Africa: In 2009, the private health insurance company, Discovery, implemented the Healthy Food Program, which provides members with a 10‑25% discount on “healthy food purchases” at supermarkets. An evaluation in 2013 revealed that those enrolled in the Program were between 2‑3 times more likely to consume at least three servings of whole grain foods per day compared to those not enrolled (An et al., 2013[30]). By offering this discount to holders of private health insurance only, this policy risks increasing inequalities. It is nonetheless used here as an example to demonstrate the positive impact of making healthy foods more affordable.

It is important to note, however, that the market economy, not policy instruments, are the main driver of prices.

Review how access to high whole grain products differs across population groups. A review into the price difference between products with and without the Whole Grain Partnership logo would provide important information on whether lower socio‑economic groups face barriers to purchasing high whole grain foods. Similarly, a review into where Whole Grain Partnership products are sold is important for understanding if certain geographical regions have limited access to these products (e.g. by urban/regional/remote areas and by type of store such as a supermarkets and health food stores). Findings from the study will guide follow-up action to improve equal access to high whole grain products.

Enhancing the evidence‑base

Explore the possibility of natural experiments and/or experimental studies. The increase in whole grain intake cannot be directly attributed to the Whole Grain Partnership as studies do not control for whether a person was exposed to the logo or not. To address this limitation, researchers could explore the possibility of undertaking natural experiments – i.e. an empirical study where participants are “naturally” exposed to the logo or not. This may not be possible in Denmark given the Whole Grain Partnership logo is widely known, however, it may be possible in countries transferring the intervention as part of WholEUGrain initiative (described further under “Transferability assessment”) – namely Romania, Slovenia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina. Alternatively, or in addition, researchers could run experimental studies in a controlled environment, as has been done to evaluate the impact of the food labelling scheme, Nutri-Score (see Box 9.7 for an example study). However, caution must be taken when interpreting results from these studies given they can markedly overestimate the impact of food labelling schemes (Dubois et al., 2020[31]).

Box 9.7. Assessing the impact of Nutri-Score

Nutri-Score is a “traffic light” food labelling scheme available on food products across numerous European countries, such as France. To evaluate the impact of Nutri-Score on nutrient intake, Egnell et al. (2019[32]) undertook a 3‑armed control trial involving nearly 3 000 participants who were randomly exposed to one of the following food labelling schemes: 1) Nutri-Score, 2) reference intakes (% of recommended intake by each nutrient category) or 3) no label.

The researchers created a web-based supermarket that included 750 food items representative of products commonly sold in France (each item included a name, price and picture). Participants in each group were then asked to “purchase” items as if they were in their local supermarket (Egnell et al., 2019[32]).

To evaluate the impact of Nutri-Score, researchers compared the overall nutritional quality within virtual shopping carts across the different groups. Results from the analysis found the nutritional quality of food purchased was higher for those in the Nutri-Score group compared to the reference intake and no labels group (Egnell et al., 2019[32]).

The impact of Nutri-Score has also been evaluating using a real-life grocery shopping setting (Allais et al., 2017[33]), which, similar to Egnell et al. (2019[32]), found Nutri-Score improved the nutritional quality of food purchased and reduced calories.

Collect food consumption data using population surveys. Food purchases from retail stores are a reliable data source however they are not directly linked to consumption. Further, this type of data cannot be used to analyse the impact of nutrition labelling schemes across population groups (for instance, by age, gender and education), except for data linked to loyalty card registration. Future studies using survey-based data on consumption would enhance the evidence‑base supporting DWGP.

Enhancing extent of coverage

Increase access to small producers. Small producers of whole grain products may face barriers to becoming a Whole Grain member given the cost of reformulating products to meet specific guidelines as well as annual membership costs (see Box 9.8). To increase the number of members and therefore products with the whole grain logo, policy makers could offer membership subsidies and/or tax benefits that incentivise manufactures to reformulate their products.

Box 9.8. Costs to manufacturers

Access to the Whole Grain Partnership may be limited for small producers given the costs of reformulating products as well as annual membership costs, as described below.

Reformulation costs

Health food labelling initiatives encourage manufacturers to reformulate products to meet nutritional guidelines (i.e. by gaining a competitive advantage in the market). Manufacturers incur a cost to reformulate products, for example to: invest in research and development, develop new production process as well as market the new product to consumers. A study by the UK Foods Standard Agency estimated the cost of reformulation between GBP 5 000 (EUR 5 928) to GBP 45 000 (EUR 53 357) per product (depending on factors such as availability of replacement ingredients and whether production processes need to change) (Food Standards Agency, 2010[34]). Further details on product reformulation and its impact on the food industry can be found in OECD’s The Heavy Burden of Obesity report (2019) (OECD, 2019[35]).

Membership costs

To become a Whole Grain Partnership member manufacturers pay a membership fee, which is dependent on their annual turnover. The lowest fee level is DKK 10 000/year (approximately EUR 1 345) for producers with a turnover of less than DKK 5 million (EUR 670 000). Founding members pay a higher fee while large retailers pay a fee of 155 000 DKK/year (EUR 20 843). Further, there is a graduation of fees among retail partners while there are different arrangements in place for bakers and schools. The annual membership fee may act as a barrier for certain producers, in particular for small businesses.

Policy makers can also enhance the extent of coverage through non-financial incentives. For example, in Chile, the Ministry of Agriculture has put in place a platform that brings together public institutions and private industry, working together to promote reformulation toward healthier products (OECD, 2019[36]). In addition, policy makers can put in place actions to encourage consumption of products with the DWGP logo for example by promoting such foods in workplaces, schools and hospitals.

Transferability

This section explores the transferability of DWGP and is broken into three components: 1) an examination of previous transfers; 2) a transferability assessment using publically available data; and 3) additional considerations for policy makers interested in transferring DWGP.

Previous transfers

The success of DWGP led to the European project – “A European Action on Whole Grain Partnerships” (WholEUGrain). The project, which will run from 2019‑22, is designed to assist countries transfer and adapt the Whole Grain Partnership to their local setting. Four countries, including Denmark, are involved in WholEUGrain – Romania, Slovenia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina (European Commission, 2019[37]).

As part of WholEUGrain, a “Toolbox” to guide countries through the implementation process was developed (see Box 9.9 for further details). In addition, there is a three‑day summer or spring school, which will be hosted every year of the project (typically in person, however, due to COVID‑19 pandemic, in 2021 and partly in 2022, were run virtually). The summer and spring schools consists of several webinars providing answers to questions such as “what are the pre‑requisites for a well-functioning Partnership”?

Box 9.9. Toolbox guide for implementing the Whole Grain Partnership

To assist countries transfer the Whole Grain Partnership to their local setting, WholEUGrain developed a Toolbox guide with help from the Danish Whole Grain Partnership. The Toolbox outlines a multi-step process for running a public private partnership to boost whole grain intake. The Toolbox is available on the WholEUGrain website: https://www.gzs.si/wholeugrain/vsebina/Publications/Reports/Toolbox.

Map potential partners in the Whole Grain Partnership and perform a stakeholder analysis

Set up a taskforce to drive the formal creation of the Whole Grain Partnership

Develop a financing model

Define and describe the different roles of each partner

Describe the code of conduct

Outline a partnership agreement that partners must sign

Describe a model for organising work and rules of procedures for different stakeholders

Establish a secretariat to co‑ordinate activities, execution of decisions and managerial support

Develop a long-term strategy and yearly action plan

Map external stakeholders that can assist in achieving stated objectives.

Transferability assessment

The following section outlines the methodological framework to assess transferability and results from the assessment.

Methodological framework

A few indicators to assess the transferability of the Whole Grain Partnership were identified (see Table 9.4). Indicators were drawn from international databases and surveys to maximise coverage across OECD and non-OECD European countries. Please note, the assessment is intentionally high level given the availability of public data covering OECD and non-OECD European countries.

The transferability assessment of DWGP is in particular limited given indicators related to the food retail market and consumer behaviour are collected by private research companies and therefore not available for public use.

Table 9.4. Indicators to assess the transferability of the Danish Whole Grain Partnership

|

Indicator |

Reasoning |

Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

|

Sector specific context (retail food, food service sectors) |

||

|

Current nutrition labelling policies for pre‑packaged foods |

WG Partnership is more transferable to countries that have with existing structure in place to support front-of-pack (FOP) nutrition labels (e.g. regulatory frameworks) |

FOP scheme in place = more transferable |

|

Political context |

||

|

Operational strategy/action plan/policy to reduce unhealthy eating |

The WG Partnership will be more successful in countries which prioritise healthy eating |

“Yes” = more transferable |

|

Economic context |

||

|

Prevention expenditure as a percentage of current health expenditure (CHE) |

The WG Partnership is a prevention intervention, therefore, it will be more successful in countries that allocate a higher proportion of health spending to prevention |

🡹 value = more transferable |

Source: OECD (2018[38]), “Preventative care spending as a proportion of current health expenditure”, https://data.oecd.org/healthres/health-spending.htm; WHO (2019[39]), “Existence of operational policy/strategy/action plan to reduce unhealthy diet related to NCDs (Noncommunicable diseases)”, https://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.imr.NCD_CCS_DietPlan?lang=en; OECD (2019[35]), The Heavy Burden of Obesity: The Economics of Prevention, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/67450d67-en.

Results

Over half (64%) of OECD and non-OECD European countries have a FOB nutrition labelling scheme, however, they do not relate to whole grain consumption, rather they focus on the overall nutrition quality of a product based on salt, sugar and fat intake (see Table 9.5). These results indicate there is support for food labelling schemes to help people make better choices.

The majority of countries have in place a national action plan to reduce levels of unhealthy eating (91%) and spend proportionally more on preventative care than Denmark (2.4% versus 2.5% of current health expenditure) – similarly, these results reflect political support for interventions that encourage people to eat better.

Table 9.5. Transferability assessment by country, the Danish WholeGrain Partnership (OECD and non-OECD European countries)

A darker shade indicates the Danish Whole Grain Partnership is more suitable for transferral in that particular country

|

FOP* labelling |

Mandatory or voluntary FOP** |

Unhealthy eating action plan |

Prevention expenditure percentage CHE*** |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Denmark |

Yes |

V |

Yes |

2.44 |

|

Australia |

Yes |

V |

Yes |

1.93 |

|

Austria |

No |

None |

Yes |

2.11 |

|

Belgium |

Yes |

V |

Yes |

1.65 |

|

Bulgaria |

Yes |

V |

Yes |

2.83 |

|

Canada |

No |

None |

Yes |

5.96 |

|

Chile |

Yes |

M |

Yes |

n/a |

|

Colombia |

No |

None |

Yes |

2.05 |

|

Costa Rica |

No |

None |

Yes |

0.60 |

|

Croatia |

Yes |

V |

Yes |

3.16 |

|

Cyprus |

No |

None |

No |

1.26 |

|

Czech Republic |

Yes |

V |

Yes |

2.65 |

|

Estonia |

No |

None |

Yes |

3.30 |

|

Finland |

Yes |

M |

Yes |

3.98 |

|

France |

Yes |

V |

Yes |

1.80 |

|

Germany |

Yes |

V |

Yes |

3.20 |

|

Greece |

No |

None |

No |

1.27 |

|

Hungary |

No |

None |

Yes |

3.04 |

|

Iceland |

Yes |

V |

Yes |

2.68 |

|

Ireland |

Yes |

V |

Yes |

2.60 |

|

Israel |

Yes |

M |

Yes |

0.37 |

|

Italy |

No |

None |

Yes |

4.41 |

|

Japan |

No |

None |

Yes |

2.86 |

|

Latvia |

No |

None |

Yes |

2.58 |

|

Lithuania |

Yes |

V |

Yes |

2.17 |

|

Luxembourg |

Yes |

V |

Yes |

2.18 |

|

Malta |

No |

None |

Yes |

1.30 |

|

Mexico |

Yes |

M |

Yes |

2.92 |

|

Netherlands |

Yes |

V |

Yes |

3.26 |

|

New Zealand |

Yes |

V |

No |

n/a |

|

Norway |

Yes |

V |

Yes |

2.45 |

|

Poland |

Yes |

V |

Yes |

2.28 |

|

Portugal |

Yes |

V |

Yes |

1.68 |

|

Republic of Korea |

Yes |

V |

Yes |

3.48 |

|

Romania† |

No |

None |

Yes |

1.42 |

|

Slovak Republic |

No |

None |

Yes |

0.77 |

|

Slovenia† |

Yes |

V |

Yes |

3.13 |

|

Spain |

Yes |

V |

Yes |

2.13 |

|

Sweden |

Yes |

V |

No |

3.27 |

|

Switzerland |

Yes |

V |

Yes |

2.63 |

|

Turkey |

No |

None |

Yes |

n/a |

|

United Kingdom |

Yes |

V |

Yes |

5.08 |

|

United States |

No |

None |

Yes |

2.91 |

Note: The shades of blue represent the distance each country is from the country in which the intervention currently operates, with a darker shade indicating greater transfer potential based on that particular indicator (see Annex A for further methodological details). † = transferring the Whole Grain Partnership as part of WholEUGrain. *FOP = front-of-pack; M = mandatory; V = voluntary. ***CHE = current health expenditure. n/a = no available data.

Source: OECD (2018[38]), “Preventative care spending as a proportion of current health expenditure”, https://data.oecd.org/healthres/health-spending.htm; WHO (2019[39]), “Existence of operational policy/strategy/action plan to reduce unhealthy diet related to NCDs (Noncommunicable diseases)”, https://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.imr.NCD_CCS_DietPlan?lang=en; OECD (2019[35]), The Heavy Burden of Obesity: The Economics of Prevention, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/67450d67-en.

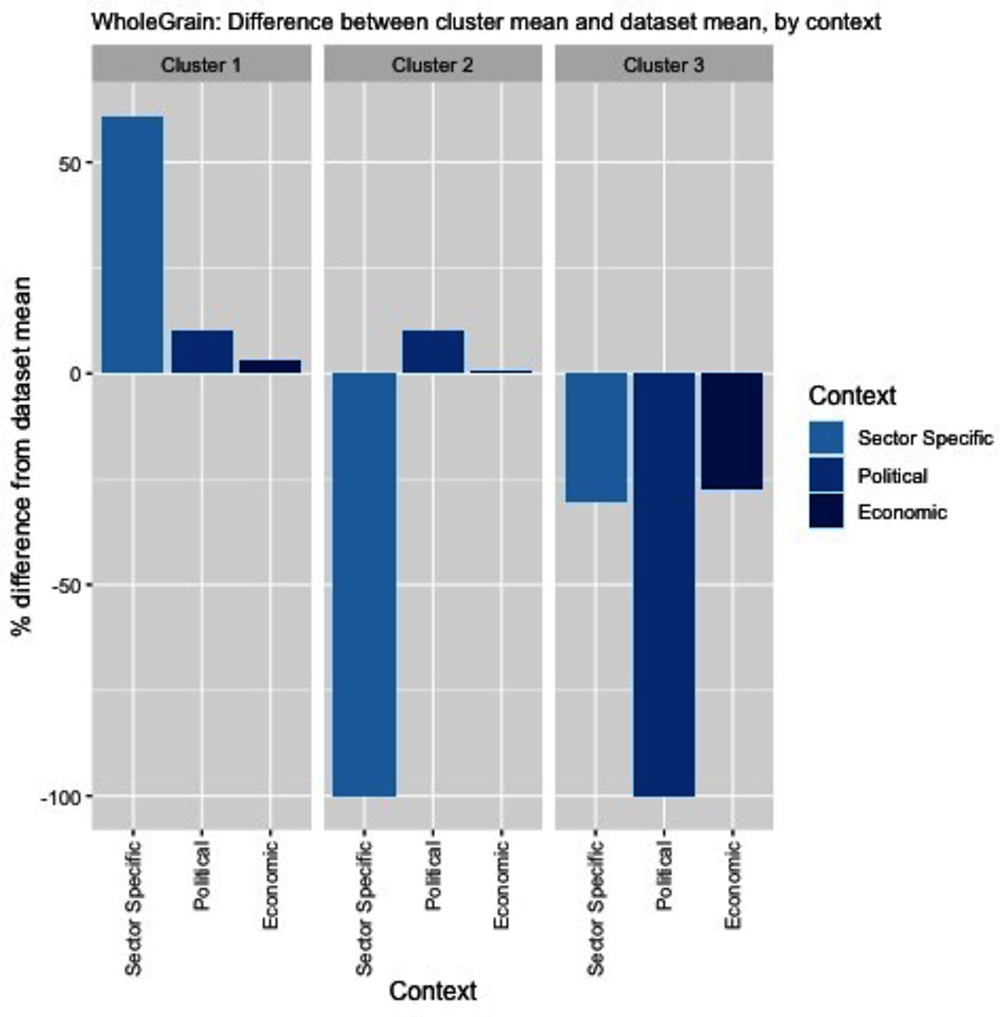

To help consolidate findings from the transferability assessment above, countries have been clustered into one of three groups, based on indicators reported in Table 9.4. Countries in clusters with more positive values have the greatest transfer potential. For further details on the methodological approach used, please refer to Annex A.

Key findings from each of the clusters are below with further details in Figure 9.3 and Table 9.6:

Countries in cluster one, which includes Denmark, have sector specific, political and economic arrangements in place to transfer DWGP. Countries in this cluster are therefore less likely to experience issues in implementing and operating DWGP in their local context.

Countries in cluster two, prior to transferring DWGP, would benefit from assessing whether the sector is ready to implement such an intervention (e.g. determining whether front-of-pack labelling is allowed).

Countries in cluster three would similarly benefit from assessing the sector’s readiness to implement DWGP, as well as ensuring that the intervention aligns with overarching political priorities and is affordable in the longer term given relatively low levels of spending on prevention.

Figure 9.3. Transferability assessment using clustering, The Danish WholeGrain Partnership

Note: Bar charts show percentage difference between cluster mean and dataset mean, for each indicator.

Source: OECD (2018[38]), “Preventative care spending as a proportion of current health expenditure”, https://data.oecd.org/healthres/health-spending.htm; WHO (2019[39]), “Existence of operational policy/strategy/action plan to reduce unhealthy diet related to NCDs (Noncommunicable diseases)”, https://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.imr.NCD_CCS_DietPlan?lang=en; OECD (2019[35]), The Heavy Burden of Obesity: The Economics of Prevention, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/67450d67-en.

Table 9.6. Countries by cluster, the Danish WholeGrain Partnership

|

Cluster 1 |

Cluster 2 |

Cluster 3 |

|---|---|---|

|

Australia Belgium Bulgaria Chile Croatia Czech Republic Denmark Finland France Germany Iceland Ireland Israel Lithuania Luxembourg Mexico Netherlands Norway Poland Portugal Republic of Korea Slovenia Spain Switzerland United Kingdom |

Austria Canada Colombia Costa Rica Estonia Hungary Italy Japan Latvia Malta Romania Slovak Republic Turkey United States |

Cyprus Greece New Zealand Sweden |

New indicators to assess transferability

Data from publically available datasets is not ideal to assess the transferability of public health interventions, in particular for DWGP given indicators on the food retail market and consumer behaviour are collected by private research companies (e.g. Euromonitor International). Hence, Box 9.10 outlines several new indicators policy makers could consider before transferring DWGP.

Box 9.10. New indicators to assess transferability

In addition to the indicators within the transferability assessment, policy makers are encouraged to collect information for the following indicators:

Population context

Is there data to measure baseline consumption of whole grain in the country (e.g. national survey data)?

What are the current dietary habits of the population?

What factors are important to people when purchasing food?

What proportion of food consumed is pre‑packaged?

What is the attitude towards whole grains in society?

Where do people purchase their food (e.g. supermarkets (online vs in-person), locally in fresh-food markets)?

What proportion of people report using nutrition food labels to guide food-purchasing decisions?

Sector specific context (retail food, food service sectors)

What nutritional labels already exist on products?

Does the legal and regulatory framework support nutrition food labels?

How many local producers of high whole grain products are there in the country?*

Are there any legal impediments for establishing a formal public/private partnership between government, private entities, NGOs, research bodies and other potential partners?

Is there a legal definition of what constitutes a high whole grain product?

What, if any, food based dietary guidelines exist? How are whole grains represented?

Political context

Has the intervention received political support from key decision-makers?

Has the intervention received commitment from key decision-makers?

Are there existing structures or relationships in place that are conducive to establishing a public-private partnership among key stakeholders?

*DWGP noted that the small size of the country allowed members to meet frequently (Fuldkorn, 2020[3]). This may not be possible in a large country.

Conclusion and next steps

DWGP uses a multi-pronged strategy to boost whole grain consumption in Denmark. Activities to boost consumption include increasing the availability of whole grain products, promoting the development of whole grain products and the whole grain logo, delivering educational campaigns and events and promoted whole grain s as a climate‑positive food.

DWGP is associated with an increase in whole grain consumption. The introduction of DWGP is associated with an increase in whole grain consumption. Given there is strong evidence to support the link between high whole grain consumption and lower risk of developing certain cancers (e.g. colorectal cancer), type 2 diabetes and CVDs, DWGP plays an important role in improving population health (WholEUGrain, 2021[21]).

An assessment of DWGP’s performance against the best practice criteria highlighted potential areas for improvement. These include, but are not limited to, partnerships between policy makers and retail outlets offering discounts/promotions on DWGP products as well as making it easier for small producers to sign up to the Partnership.

There are a number of factors countries need to consider before transferring DWGP. Indicators measuring the transferability potential of DWGP to OECD and non-OECD European countries is limited given data on the food retail market and consumer behaviour are not for public use. Instead, this case study outlines a range of indicators policy makers should consider before transferring the Partnership such as existing dietary habits and attitudes towards whole grains in society.

Box 9.11 outlines next steps for policy makers and funding agencies regarding DWGP.

Box 9.11. Next steps for policy makers and funding agencies

Next steps for policy makers and funding agencies to enhance DWGP are listed below:

Support policy efforts to enhance population health literacy to encourage people to make healthy choices (such as purchasing products with a the Whole Grain logo)

Support and encourage food companies to adopt the Whole Grain logo and add whole grain to relevant products

Support efforts to increase the affordability of high whole grain products

Promote findings from the DWGP case study to understand what countries are interested in transferring the intervention.

References

[33] Allais, O. et al. (2017), Évaluation Expérimentation Logos Nutritionnels, Rapport pour le FFAS, https://solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/rapport_final_groupe_traitement_evaluation_logos.pdf.

[13] Andersen, J. et al. (2020), “Intake of whole grain and associations with lifestyle and demographics: a cross-sectional study based on the Danish Diet, Cancer and Health—Next Generations cohort”, European Journal of Nutrition, Vol. 60/2, pp. 883-895, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-020-02289-y.

[30] An, R. et al. (2013), “Eating Better for Less: A National Discount Program for Healthy Food Purchases in South Africa”, American Journal of Health Behavior, Vol. 37/1, pp. 56-61, https://doi.org/10.5993/ajhb.37.1.6.

[8] Brownell, K. and J. Koplan (2011), “Front-of-Package Nutrition Labeling — An Abuse of Trust by the Food Industry?”, New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 364/25, pp. 2373-2375, https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp1101033.

[24] Campos, S., J. Doxey and D. Hammond (2011), “Nutrition labels on pre-packaged foods: a systematic review”, Public Health Nutrition, Vol. 14/8, pp. 1496-1506, https://doi.org/10.1017/s1368980010003290.

[7] Cecchini, M. and L. Warin (2015), “Impact of food labelling systems on food choices and eating behaviours: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized studies”, Obesity Reviews, Vol. 17/3, pp. 201-210, https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12364.

[22] Curtain, F., A. Locke and S. Grafenauer (2020), “Growing the Business of Whole Grain in the Australian Market: A 6-Year Impact Assessment”, Nutrients, Vol. 12/2, p. 313, https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12020313.

[4] DTU Fødevareinstituttet (2008), Wholegrain: definition and scientific background for recommendations of wholegrain intake in Denmark.

[31] Dubois, P. et al. (2020), “Effects of front-of-pack labels on the nutritional quality of supermarket food purchases: evidence from a large-scale randomized controlled trial”, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 49/1, pp. 119-138, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-020-00723-5.

[32] Egnell, M. et al. (2019), “Front-of-Pack Labeling and the Nutritional Quality of Students’ Food Purchases: A 3-Arm Randomized Controlled Trial”, American Journal of Public Health, Vol. 109/8, pp. 1122-1129, https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2019.305115.

[23] European Commission (2020), Whole Grain, https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/en/health-knowledge-gateway/promotion-prevention/nutrition/whole-grain# (accessed on 14 December 2020).

[37] European Commission (2019), WholEUGrain – A European action on Whole Grain partnerships [WholEUGrain] [874482] - project, https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/chafea_pdb/health/projects/874482/summary (accessed on 14 December 2020).

[28] Eurostat (2014), Body mass index (BMI) by sex, age and income quintile.

[34] Food Standards Agency (2010), Impact assessment of recommendations on saturated fat and added sugar reductions, and portion size availability, for biscuits, cakes, buns, chocolate confectionery and soft drinks, https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130106062613/http://www.food.gov.uk/multimedia/pdfs/satfatimpactassessment.pdf.

[3] Fuldkorn (2020), The story of the partnership and whole grains, https://fuldkorn.dk/om-partnerskabet/historien-om-partnerskabet-og-fuldkorn/ (accessed on 8 October 2020).

[6] Fuldkorn (2020), The Whole Grain Logo Manual: Guidelines for Use of the Danish Whole Grain Logo, https://fuldkorn.dk/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Fuldkornslogomanualen_revideret-udgave_gældende-fra-5.-maj-2020-31.-december-2022_English.pdf.

[9] Health Norway (2019), The Keyhole – for healthier food, https://www.helsenorge.no/en/kosthold-og-ernaring/keyhole-healthy-food/.

[16] Jensen, J. (2020), Vurdering af sundhedsøkonomiske gevinster ved øget overholdelse af kostrådene, University of Copenhagen, https://static-curis.ku.dk/portal/files/240258550/IFRO_Udredning_2020_07.pdf.

[10] Kyrø, C. and A. Tjønneland (2016), “Whole grains and public health”, BMJ, p. i3046, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i3046.

[20] Larson, N., M. Story and M. Nelson (2009), “Neighborhood Environments”, American Journal of Preventive Medicine, Vol. 36/1, pp. 74-81.e10, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.025.

[2] Lourenço, S. et al. (2019), “The Whole Grain Partnership—How a Public–Private Partnership Helped Increase Whole Grain Intake in Denmark”, Cereal Foods World, https://doi.org/10.1094/cfw-64-3-0027.

[12] Mejborn, H. et al. (2013), Wholegrain intake of Danes 2011-12, Division of Nutrition, National Food Institute, Technical University of Denmark.

[17] Meyre, D. (ed.) (2018), “The economic burden of not meeting food recommendations in Canada: The cost of doing nothing”, PLOS ONE, Vol. 13/4, p. e0196333, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0196333.

[27] Moreira, L. (2018), “Health literacy for people-centred care: Where do OECD countries stand?”, OECD Health Working Papers, No. 107, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/d8494d3a-en.

[26] OECD (2019), Health for Everyone?: Social Inequalities in Health and Health Systems, OECD Health Policy Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/3c8385d0-en.

[36] OECD (2019), OECD Reviews of Public Health: Chile: A Healthier Tomorrow, OECD Reviews of Public Health, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264309593-en.

[35] OECD (2019), The Heavy Burden of Obesity: The Economics of Prevention, OECD Health Policy Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/67450d67-en.

[38] OECD (2018), Preventative care spending as a proportion of current health expenditure, OECD, Paris.

[15] Rikard Landberg and N. Scheers (2021), Whole Grains and Health, Wiley-Blackwell.

[11] Ross, A. et al. (2015), “Recommendations for reporting whole-grain intake in observational and intervention studies”, The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Vol. 101/5, pp. 903-907, https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.114.098046.

[1] Stanaway, J. et al. (2018), “Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017”, The Lancet, Vol. 392/10159, pp. 1923-1994, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(18)32225-6.

[18] Sumanac, D., R. Mendelson and V. Tarasuk (2013), “Marketing whole grain breads in Canada via food labels”, Appetite, Vol. 62, pp. 1-6, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2012.11.010.

[14] Suthers, R., M. Broom and E. Beck (2018), “Key Characteristics of Public Health Interventions Aimed at Increasing Whole Grain Intake: A Systematic Review”, Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, Vol. 50/8, pp. 813-823, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2018.05.013.

[25] Svendsen, M. et al. (2020), “Associations of health literacy with socioeconomic position, health risk behavior, and health status: a large national population-based survey among Danish adults”, BMC Public Health, Vol. 20/1, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08498-8.

[29] Toups, K. (2020), “Global approaches to promoting whole grain consumption”, Nutrition Reviews, Vol. 78/Supplement_1, pp. 54-60, https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuz067.

[19] Van Loo, E. et al. (2011), “Consumers’ willingness to pay for organic chicken breast: Evidence from choice experiment”, Food Quality and Preference, Vol. 22/7, pp. 603-613, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2011.02.003.

[39] WHO (2019), Existence of operational policy/strategy/action plan to reduce unhealthy diet related to NCDs (Noncommunicable diseases), https://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.imr.NCD_CCS_DietPlan?lang=en.

[5] WholEUGrain (2021), Toolbox: A guide to implement a successful national whole grain partnership, https://www.gzs.si/Portals/288/Toolbox_opdateret%2009082021.pdf.

[21] WholEUGrain (2021), WholEUGrain project: a European Action on Whole Grain Partnerships - Deliverable number 4.1 (evidence base for the health benefits of whole grains including sustainability aspects), https://www.gzs.si/Portals/288/210427_WholEUGrain_Deliverable%204.1_FINAL%20report.pdf.

Notes

← 1. The Danish Food Institute define a whole grain as “the intact and processed (dehulled, ground, cracked, flaked or the like) grain, where the fractions endosperm, bran, and germ are present in the same proportions as in the intact grain” (DTU Fødevareinstituttet, 2008[4]).

← 2. Annual turnover < DKK 5 million (EUR 0.67 million) = fee is DKK 10 000 (EUR 1 344) per year; annual turnover < DKK 15 million (EUR 2 million) = fee is DKK 25 000 (EUR 3 361) per year; and if annual turnover is > DKK 15 million (EUR 2 million) = annual fee is DKK 50 000 (EUR 6 721) per year.

← 3. Data provided by the Whole Grain Partnership, Denmark.