Viet Nam must achieve more efficient allocation of resources and reinvigorate productivity growth across all sectors in order to obtain its objective of attaining high-income status. Better integration of smallholders into agricultural supply chains may help Viet Nam gain competitiveness on global markets, while improving incomes in rural areas. The integration of services with manufacturing holds significant potential for Viet Nam’s economy. Achieving this requires a four-pillar framework. First, a more transparent and conducive market environment would provide equal opportunity to all firms (private, public and foreign). Second, partnerships between universities and entrepreneurs would create and accelerate innovation, thus bringing competitive gains. Third, policies to stimulate the business services sector would create the conditions for strong domestic private companies to emerge. Fourth, public support would help to attract the types of FDI that facilitate the creation of new capabilities and help Vietnamese firms prepare for linkage opportunities.

Multi-dimensional Review of Viet Nam

4. New opportunities in agriculture, manufacturing and services in Viet Nam

Abstract

The strategic recommendations in this second part of the Multi-dimensional Review of Viet Nam build on the Initial Assessment and intend to support the drafting of Viet Nam’s Socio-economic Development Strategy 2021-2030 (SEDS).

The analysis and recommendations focus on the first of the challenges identified in Part I: Creating an integrated, transparent and sustainable economy. Integration is here understood as a broad concept, covering integration with the global economy as well as within the domestic market. The alternative to this strategic objective would be an economy caught in a low-productivity trap caused by inefficient allocation of resources and a lack of absorptive capacity for the opportunities provided by international integration.

Viet Nam now has a unique window of opportunity to engage in the necessary reforms (Chapter 1). It should use this window to undertake strategic changes to strengthen the domestic economy while capitalising on its participation in global value chains to upgrade productive capabilities.

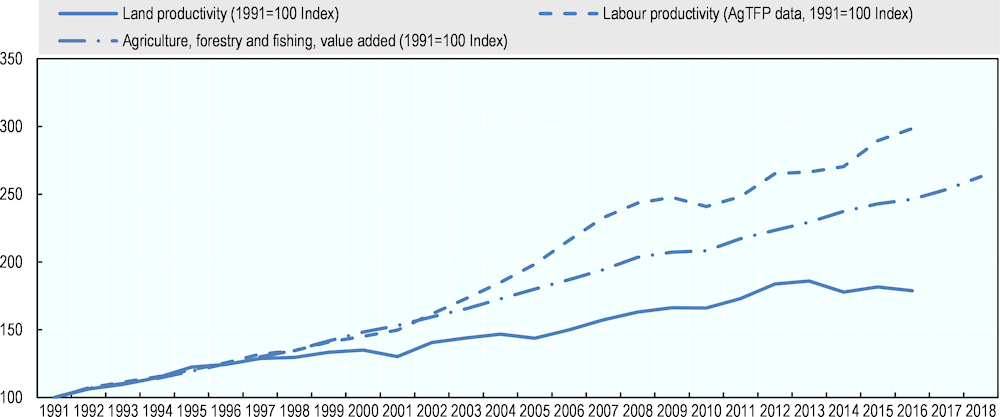

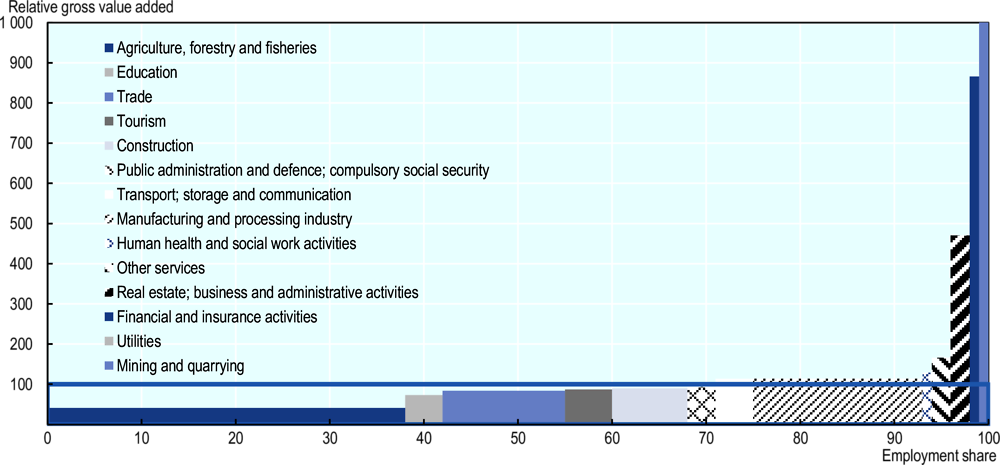

Viet Nam must achieve more efficient allocation of resources and reinvigorate productivity growth across all sectors in order to obtain its objective of attaining high-income status. Total factor productivity growth has fallen behind that of its regional peers (see Chapter 1, Figure 1.14), with the economy locked into a tripartite structure consisting of export-oriented foreign direct investment (FDI), state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and the domestic private sector. The shares of these individual segments in the economy and their significant productivity differentials have not changed notably over the last decade. Similarly, from the perspective of productive sectors, about 95% of the workforce are active in sectors with relatively low labour productivity, including agriculture (40%), retail (13%), construction (8%) and even manufacturing (18%) (Figure 4.1). In order to ensure deep productivity gains and inclusive growth that reaches all citizens, the role of the three main actors of the economy has to evolve.

Figure 4.1. Productivity and the distribution of labour in Viet Nam

Note: Labour productivity is measured as the annual value added (the value of output less the value of intermediate consumption) per employee. Weighted average productivity (on the y-axis) is normalised to 100; a sector with a relative gross value added larger than 100, is more productive than the average. Share of total employment is represented on the x-axis. “Utilities” include water supply; waste management and treatment activities, as well as production and distribution of electricity, gas, hot water, steam and air conditioning. It is not visible in the graph because of the relatively low share of employment (less than 1% of total employment).

Source: OECD calculations based on data provided by MPI, as well as on 2018 data by the United Nations “National aggregates database” and the ILO.

The domestic private sector – which includes here both formal enterprises and small informal firms – could become an important agent of change if operating under the right conditions. In spite of the significant efforts and great achievements of the past 30 years, common challenges to business development persist in different economic sectors. The playing field is often not competitive and the market does not provide opportunities for all, with SOEs and foreign investors often competing at an advantage. Corruption, although declining, remains a source of inefficiencies. Furthermore, lack of necessary skills at the worker and the management level inhibit growth of innovation and productivity. In a more conducive business environment, the private sector could become a third engine of growth, innovation and job creation, alongside quality foreign investors and productive SOEs. However, change requires sector-based strategies, public policies and the involvement of both the state and private companies in policy making.

The next sections detail some strengths and constraints of three key sectors that define Viet Nam competitiveness. It also discusses selected policy recommendations to improve productivity in the agricultural sector by tackling land fragmentation and tools to effectively enhance the business environment (after decades of attempted reforms). In particular, the chapter suggests furthering leverage services and quality foreign investments to achieve industrial upgrading.

Building a strong network of domestic private firms requires competition and equal opportunities for all market participants. Chapter 5 presents a series of reforms for SOE governance that may help achieve fair competition between public and private companies. Skills are equally important and Chapter 6 explores the tertiary sector in Viet Nam and lays out a series of recommendations to build linkages between universities and the private sector that could create innovation. Chapter 7 focuses on sustainability and ensuring environmental outcomes.

Remove restrictions to let the agricultural sector transform itself

The role of the agriculture sector and private farmers in the Vietnamese economy has evolved significantly since 1975. In the 1970s, co-operatives and state farms controlled production and distribution in accordance with centrally determined targets, providing goods at a low price – set by the state – and aiming at food self-sufficiency. At the beginning of the 1980s, the system proved itself inefficient: production levels were well below targets and households were selling hoarded surpluses on the remunerative informal private market. Private farming, originally forbidden, was gradually permitted; smallholders were allowed to farm land formally owned by the co-operative in exchange for delivering an annual production quota. Any surplus was sold to the state (at higher prices than before) or on the private market (OECD, 2015[1]).

The Ðổi Mới reforms (1986) shifted the focus of agriculture and rural development from co-operatives to farm households. Co-operatives had to rent out 95% of their land to households through an egalitarian distribution of land use rights. Farmers could now sell their products at market prices and engage in foreign trade. Monetary policy and the devaluation of the currency further buoyed agricultural production, which soon became a key driver of overall economic growth. Expanding food production for export became a priority throughout the 1990s. The government promulgated a range of decrees aimed at strengthening farmers’ rights over their land, building their capacity to absorb innovation and relaxing some market restrictions (notably on rice exports) (OECD, 2015[1]). Since the 2000s, Viet Nam has invested resources in modernising the agricultural sector to produce higher quality outputs, create better jobs and raise incomes for people in rural areas.

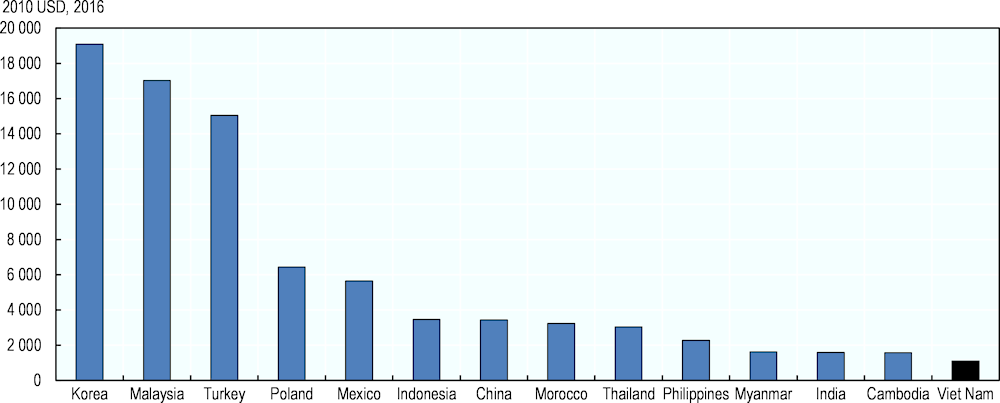

The continuous reform process has had significant benefits for the agricultural sector. Today, Viet Nam outperforms many of its major Asian competitors in terms of agricultural production growth. Between 1991 and 2016, the total value of crop and animal production increased by more than 200% – the third highest increase in Southeast Asia after Cambodia and Myanmar – land productivity increased by 79% and labour productivity growth was even more rapid (Figure 4.2). Total factor productivity (TFP) growth, which captures unobservable conditions for an efficient combination of production factors, has been strong over the last 20 years.

The agricultural and industrial sector are also well integrated, with numerous enterprises processing agricultural input or transforming them in manufactures (such as food products, wearing apparel, and wood products). According to the 2016 enterprise survey, 61% of manufacturing enterprises are active in the agro-industry. Most of them produce natural fibre clothing, products made of wood or cork, furniture, paper products and beverages (mostly bottled waters). Moreover, 20% of firms in the agro-industry are operating directly in the primary sector, mostly supporting agricultural activities – especially crop production (Table 4.1).

Table 4.1. Agriculture and industry are well integrated

Distribution of enterprises in the agro-industry sector

|

Sectors |

Enterprises in the agro-industry sector |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Number of enterprises |

Share of enterprises in the agro-industry (%) |

Share of enterprises in manufacturing (%) |

|

|

Agriculture and related service activities |

8 362 |

20.06 |

|

|

Manufacture of food products |

6 727 |

16.13 |

9.9 |

|

Manufacture of wearing apparel |

6 002 |

14.39 |

8.8 |

|

Manufacture of wood and of products of wood and cork, except furniture; manufacture of products of straw and plaiting materials; |

4 558 |

10.93 |

6.7 |

|

Manufacture of furniture |

3 324 |

7.97 |

4.9 |

|

Manufacture of textiles |

2 843 |

6.82 |

4.2 |

|

Manufacture of paper and paper products |

2 276 |

5.45 |

3.3 |

|

Manufacture of beverages |

2 226 |

5.34 |

3.3 |

|

Fishing and aquaculture |

1 704 |

4.08 |

2.5 |

|

Other manufacture |

3 697 |

8.86 |

5.4 |

|

Total enterprises in the agro-industry sector |

41 719 |

100 |

61.1 |

Note: Enterprises have been classified as part of the agro-industry sector by mapping self-declared Vietnamese Standard Industrial Classification (VSIC) code to ISIC codes, and according to guidelines discussed by “FAO-UNIDO Expert Group Meeting on Agro-Industry Measurement”. The categories, defined at the VSIC 2-digit level, encompass only those activities (defined at the 5-digit level) in the agro-industry.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on GSO Enterprise Survey 2016.

Figure 4.2. Evolution of land productivity, labour productivity and TFP

Viet Nam is seeking a new model of agricultural development that allows for significant competitive gains on global markets while respecting environmental constraints. After an initial surge, growth in land productivity, labour productivity and TFP has progressively lost momentum, significantly affecting overall agricultural output. Quality of products has not improved either, and agricultural value added per worker remains the lowest among regional peers and comparator countries (Figure 4.3). The rapid expansion of the 1990s saw the excessive use of chemical inputs. Since 2011, ten-year Socio-Economic Development Strategies (SEDs), five-year Socio-Economic Development Plans (SEDP), the master plan for agricultural production development through 2020 (2012), and the plan for restructuring the agricultural sector (adopted in 2013) have all called for a change of pace. In November 2017, the Prime Minister and the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (MARD) adopted a new plan aiming to achieve 3% growth of the agricultural sector by 2020. The plan would: (i) expand access to basic services in the most remote rural areas of the country; (ii) train farmers and agricultural workers; and (iii) reorganise farmers and enterprises to improve the quality of output and compete on global markets.

Figure 4.3. Comparison of agricultural value added per worker (2010 USD), 2016

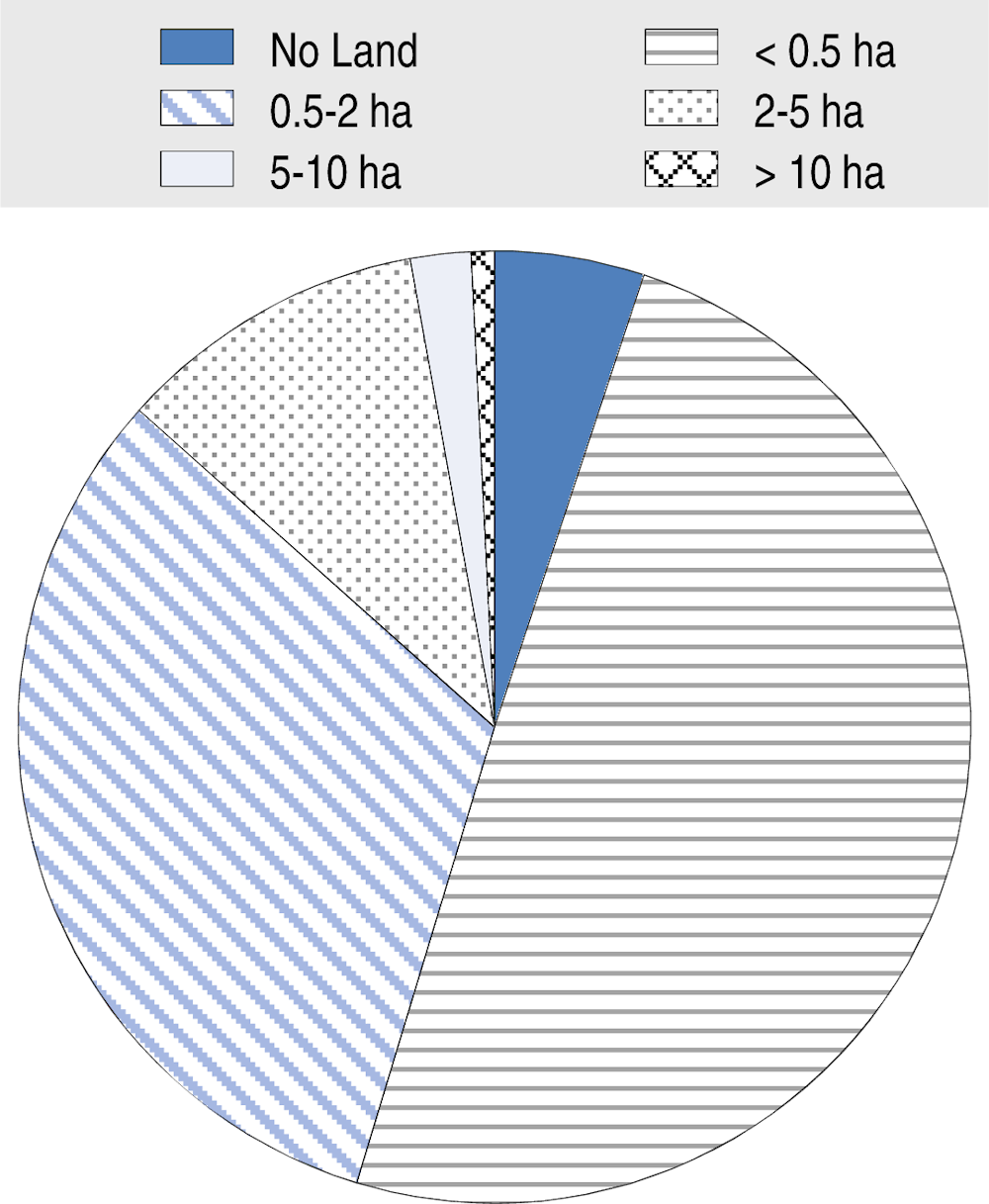

Land fragmentation is one of the main constraints on land productivity growth. Between the 1980s and the beginning of the 1990s, the state redistributed agricultural land plots to household farms, which then became autonomous economic units. Redistribution was based on several factors, including the number of individuals in households, land quality, distance among plots, and access to water resources or other infrastructures. The result was a remarkably equitable distribution of plots that outlived numerous land reforms; however, these plots remain very small. Today, there are 9 million farms in Viet Nam, half of which are subsistence farms occupying less than 0.5 hectares (Figure 4.4).1 Such land fragmentation imposes severe private costs (e.g. land loss due to boundaries, cumbersome management of infrastructures, increased disputes among neighbours) and public costs (e.g. increasing difficulties in crop and land use planning) that eventually affect the profitability and productivity of labour and land (Table 4.2).

Table 4.2. Land fragmentation entails significant private and public costs

|

Private costs |

Public costs |

|---|---|

|

Increases in costs |

Less labour released |

|

More labour used |

Higher transaction costs |

|

Land loss due to boundaries |

Delay of mechanisation and technological application |

|

Disputes among neighbours |

Difficulties in crop planning and land use planning |

|

Cumbersome water management |

|

|

Difficulties in technological application and mechanisation |

Source: Results of literature review in (Nguyen, 2014[3]).

The government has adopted numerous policies to encourage land consolidation, but markets remain small. Resolution No. 19-NQ/TW adopted by the Party’s Central Committee on 31 October 2012 has relaxed quotas for the acquisition of agricultural land use rights. The 2013 Land Law further relaxed some constraints on the exchange, transfer, lease, sub-lease and donation as well as the use purpose of land. It also extended the terms of allocation of the average agricultural land plot. The continuous process of reforms was successful. In 2016, landowners from 25% communes exchanged or merged farming plots and the average area of an agricultural production land plot in Viet Nam increased from 1 619.7 m2 in 2011 to 1 843.1 m2. However, the market for land use rights remain small. The Institute of Policy and Strategy for Agriculture and Rural Development estimates that in 2016 only 12% of agricultural land transactions occurred through purchase or auction. Instead, 40% were acquired through allocation by the state and 34% were obtained through inheritance.

Figure 4.4. Viet Nam agriculture consists predominantly of small farms

A variety of conventional and less conventional strategies may help complement Viet Nam’s recent policy efforts. On the one hand, strengthening land-use certificates may help deepen a currently small market for land. On the other hand, Viet Nam could experiment with alternative organisational structures as second-best policy options.

Going beyond land use certificates to establish an effective market for land

Enhancing land-use right certificates (LURCs) is crucial in order to facilitate the emergence of a land market that will consolidate plots and catalyse investments. Standard certificates proving ownership are the basic condition for materialising transactions. They can also be used as a mortgage-related security in loan-based operations with both formal and informal institutions of agricultural credit. Loans, in turn, are fundamental to triggering long-term investments, which then enhance the performance of agricultural production. Land tenure, however, is not sufficient to deepen the market for land if both implementation and rights remain limited.

Many households still prefer informal agreements for land use rather than requesting LURCs. In some cases, households seem to have difficulty understanding and complying with regulations and administrative procedures. In others, local administrations have not able to provide a certificate. There are even cases where certificates are available but have not been collected, as plot owners fear that authorities might use the opportunity to enforce payment of debts or fees, or to elicit bribes (Cantu and Morando, 2018[5]).

The take up rate of LURCs, moreover, varies greatly across the country and affects the most remote areas. Coverage is highest in lowland provinces but decreases sharply in mountainous provinces. Part of the explanation is that topography in upland areas complicates the measuring, mapping and registration of land. The widespread and traditional use of communal land tenure in the highlands also makes assignment of property rights to households challenging (Cantu and Morando, 2018[5]).

The government may need to simplify procedures and build capabilities to encourage the diffusion of land certificates. Requesting LURCs must become easier for vulnerable farmers and those living in remote areas. Areas that do not manage to deliver certificates must receive adequate training to strengthen their capabilities. E-government mechanisms could help to facilitate farmers’ requests and relieve local administrators from lengthy paperwork, thereby freeing up human and financial resources.2

Certificates need to evolve and provide owners with more rights. At present, LURCs help to protect farmers from land seizures, but not from insufficient compensation levels. In 2017, only 21% of surveyed landowners thought that the compensation offered for expropriation represented a fair market value, down from 36% in 2014 (CECODES et al., 2018[6]). The problem here is twofold: on the one hand, compensation depends on a land price set by the state, which is usually as low as 30% of the market value; on the other, citizens have limited access to land information or land planning, which allows for assessment of the current and future potential of plots and their market value. Only 19% of surveyed citizens claim to be informed about local land planning and only 30% of those informed had the opportunity to comment on land plans (CECODES et al., 2018[6]).3

Cadastral maps could help to improve access to information, empower LURC owners and set up properly functioning land markets. Both cadastral maps and land registers would allow for correct evaluation of land plots, help address the asymmetry of information between parties involved in transactions, align prices to the market value of land and solve potential disputes. Having a complete map of the land structure has also the advantage of broadening the property tax base, thereby improving the fiscal revenues and conditions of local authorities. Several tools, especially those relying on spatial data, could be used to construct a modern and accessible cadastre and overcome limited local capacity to map borders and use existing land plots.

Actual implementation of cadastre reform may require the buy-in of local political leaders, for whom land remains the most valuable asset. Local governments often raise revenues and attract investors who seize land plots at the moderate price set by the state and resell them at a higher price to public or private companies. Cadastre reform would contribute to aligning the face value and market value of land, but would also deprive subnational governments of a valuable source of revenue. Modern cadastres could gain momentum if local leaders were reliant on their own fiscal capacity (e.g. property and corporate taxes and fees). Incentives – for example, local government can retain up to 30% of all shared revenue actually collected in excess of the estimated amount (Morgan and Trinh, 2016[7]) – and, to a limited extent, non-discretionary and transparent fiscal transfers from the central state could help build this capacity. Ultimately, implementation will require a major revision of multi-level governance in Viet Nam.

To ensure complete and transparent information, price regulations need to be relaxed, and land prices need to be commensurate with the actual value of land. This is an essential element to accelerating land consolidation and achieving a complete and effective land market.

Relaxing land restrictions for more efficient and sustainable use of land plots

Land use restrictions further limit the scope of LURCs. In particular, state restrictions force Vietnamese farmers in some areas of the country to grow rice, as the crop is considered strategic for Viet Nam’s future subsistence and trade. Decree No. 69/2009/ND-CP (dated 13 August 2009), which accompanies Land Law 2003, establishes that any conversion of paddy land for other uses must first be approved by the Prime Minister. The Rice Land Designation Policy, for example, requires landowners to dedicate 39% of the country’s agricultural cropland (or 38 000 km2) to rice production by 2020, in order to meet export targets and ensure food security (Resolution No. 17/2011/QH13).The requirement varies across provinces and, while official figures are not clear, past estimates suggest that it affected 75% of cropland in the Mekong River Delta region and 68% in the Red River Delta in 2006 (OECD, 2015[1]).

Restrictions on rice production have made Viet Nam a major rice exporter, but have also seriously endangered the environment. Intensive rice-farming practices in the Mekong River Delta have spread, with tripled-cropped rice fields nearly doubling between 2000 and 2010 (Kontgis, Schneider and Ozdogan, 2015[8]). The region now produces half of Viet Nam’s yearly rice crop. Such intensive rice farming has pushed local communities to pump groundwater for irrigation, thus accelerating salinisation and depleting underground water supply.4 Inundation and salinity intrusion then affect rice yields, which are expected to decline by about 12% (World Bank, 2013[9]), eroding farmers’ income in the region.

Relaxing crop restrictions would benefit overall productivity and farmers’ income. For instance, eliminating all restrictions on rice production would lead to a 11% increase in the agricultural TFP, significant gains in agricultural labour productivity, a reduction in agricultural employment and an increase in average farm size (Le, 2019[10]). The farmers’ income would, moreover, be 123% higher, driving real private household consumption and poverty reduction. Food would become more secure and household diets nutritionally more balanced (Giesecke et al., 2013[11]). Without restrictions, landowners could also diversify their production towards other crops (or fisheries) that could be grown more profitably on the same land. Alternatively, formal and informal farmer organisations (see next section), as well as state-owned and private agro-food companies, could help farmers to adopt new rice varieties or improve their farming practices – for example, by providing saltwater monitoring systems or by encouraging rainwater collection as a supply of freshwater in place of groundwater (OECD, 2017[12]).

Market-based and collective solutions to land fragmentation

The creation of a complete land market is a gradual process that in certain cases requires the pursuit of alternative solutions to land fragmentation. When land consolidation is not viable, other ways may be found to enhance co-ordination among farmers, re-organise production structures, and give impetus to land productivity and modernisation.

As one example, the state could create incentives for farmers in a given area to organise in supply chains clusters. Clusters, especially in agriculture, may improve the competitiveness of firms and farms due to the synergies they create. Because of their physical proximity within a cluster, firms and farms at different stages of the value chain can initiate forms of dialogue and collaboration to resolve common problems that affect the entire chain, such as the implementation of standards or improvement of market information and access (Gálvez-Nogales, 2010[13]). Repeated interaction could, moreover, enhance mutual trust and better align the incentives of participants in the cluster. The support of local government institutions and professional associations is fundamental for clusters to succeed: they can provide technical assistance to meet local objectives, design development strategies and training programmes, and undertake market research (OECD, 2015[1]).

Domestic experience suggests that clusters may promote the farming of labour-intensive products (e.g. fruits and vegetables) that usually generate higher revenues per unit of land (OECD, 2015[14]). The Duong Lieu root crop-processing cluster, for example, engages 1 500 households, 30 km away from Hanoi, in some part of the cassava and canna processing value chain. Since the introduction of the cluster 20 years ago, average production per household has increased significantly (from 0.05 tonnes/household/year in 1978 to 9 tonnes/household/year at the beginning of the 2000s). This increase has contributed to the emergence of Viet Nam as the second largest exporter of cassava in the world. Existing domestic and international experience could help Viet Nam further identify the right conditions to scale up these alternative forms of production (Box 4.1).

Box 4.1. Agro-based clusters may contribute to the production of fruits and vegetables and the diffusion of innovation

The Duong Lieu root crop processing cluster and cassava production in Viet Nam

Households within the Duong Lieu cluster play several roles. Some extract the wet starch from fresh cassava and canna roots through grating, filtering and sedimentation. Others purchase the wet starch to produce refined dry starch of greater value. Some agents export their products in other provinces or across national borders, while other households use rice seedlings produced within the cluster to manufacture maltose from the wet cassava which is then sold to local candy producers or on global markets. Other side activities include the production of noodles and the collection of residue from the starch-processing process for pig and fish raising.

The linkages formed within the cluster have facilitated the diffusion of new technology throughout the cluster’s households. For example, local engineers and manufacturers managed to design and provide mechanical filtration equipment, root washers and water filters adapted to local needs. In addition, peer-to-peer discussion among cluster members enabled a constant flow of information across community members.

The Maharashtra grape cluster, India

Grape production in India has lately acquired a global dimension. Exports have grown rapidly from 0.1% of global grape exports in 1971 to 1.5% in 2005. Within the Indian grape sector, Maharashtra State has played a key and increasingly central role, organising the supply chain of grapes into clusters. The key actors of these clusters are as follows:

Grape producers and their associations. The local public-private partnership “Mahagrapes” gathers together local co-operatives and state authorities in support of local producers. “Mahagrapes” (i) targets possible lucrative foreign markets; (ii) develops the technology needed to pre-cool and store products before shipping; (iii) follows the procedures and meets the requirements to export (e.g. concerning pesticides and fertilisers banned by European authorities); and (iv) updates farmers and grape handlers/sorters with the latest methods.

Research institutions. Collaboration between research institutions and other cluster members has been crucial in helping producers meet the quality standards required by global markets. The Maharashtra State Grape Growers’ Association has been pivotal in establishing linkages between cluster members, agricultural universities and other Indian Council of Agricultural Research centres. Through these linkages, tertiary institutions have introduced significant innovations to grapes producers in Maharashtra, disseminating new techniques and improving the quality of the product. For example, the Indian Institute of Horticulture Research has used field trials to adapt knowledge about the production of export-quality grapes to local conditions.

Government and other institutions. The state has supported the formation of clusters by providing loans and expertise. It has also established various institutions, such as the National Horticulture Board and the Agricultural and Processed Food Products Export Development Authority, to support the export of grapes from Maharashtra. The state has also been involved in the establishment of Agri-Export Zones in grape-growing areas of Maharashtra State. In addition, the state marketing board collects technical and market information for producers. The presence of a good credit system was, moreover, crucial for cluster development, since grape-related activities are capital intensive.

Source: (Gálvez-Nogales, 2010[13]).

Where the definition of property rights and, hence, land consolidation is challenging, heterodox forms of collective property could be explored. In the highlands, for example, communal land ownership is widespread, complicating the definition of property rights over land and exacerbating the fragmentation issue. In this context, Viet Nam could experiment with “collectively owned enterprises” at the communal level. All citizens of the ward/commune/township that set up such a firm would be owners of the enterprise, while the community government would represent their interest (similar to a CEO). Collectively owned firms led industrial growth in China for most of the 1980s and 1990s. Their principal advantage over rural private enterprises was ease of access to formal credit markets. However, unlike state-owned enterprises, they were subject to more budget constraints in the form of greater market discipline and scrutiny by citizens – the actual owners of the companies. If Viet Nam were to consider adopting this model, over the long term collectively owned enterprises might need to evolve gradually into shareholding companies that maximise shareholder value and contribute to the public good by paying taxes (Box 4.2). Unclear ownership could in fact create ambiguities and conflicts of interest. For example, since the profits from these enterprises could end up providing a large share of local government budgets, a trade-off between reinvestment in the individual enterprise and public finance objectives could arise.

Box 4.2. Collectively owned enterprises and their evolution in China’s economy

Township and village enterprises (TVEs) were a form of collectively owned enterprise and the main driver of economic growth in China between 1979 and 1993. In 1993, there were 1.5 million TVEs in rural areas, employing 52 million workers (around 58% of the rural labour force) and accounting for 42% of China’s national industrial output – 72% in rural areas.

TVEs were a hybrid between private firms and SOEs: all households that were part of the same supply chain within the same village were shareholders in the company. The local government co-ordinated TVE activities and played the role of CEO. In spite of loosely defined property rights, TVEs managed to lift local productive capabilities. The collectivisation of assets indeed strengthened the monitoring mechanisms exerted by villagers and tightened internal constraints on the managerial embezzlement of firm property or rent extraction. At the same time, the incentives to perform were high: TVE profits accounted for a large share of government budgets, which were then willingly invested in public goods and services to enhance TVE productivity.

TVE outperformance also had spillover effects on the rest of the economy, contributing to the creation of local fiscal capacity. In addition, taxing TVEs (with books kept by local governments) proved easier than taxing privately owned enterprises. TVEs, moreover, provided incentives for investing in rural areas, thereby preventing villages from falling behind fast-developing urban areas.

Collectively owned enterprises, however, remain a form of leverage, not a solution. During the 1990s, TVEs suffered from agency problems: TVE managers were political appointees and sometimes prioritised their political career over the profit maximisation of collectively owned enterprises. Information asymmetries and imperfect monitoring further exacerbated the issue. Moreover, the lack of clearly defined property rights undermined long-term growth and investments. While TVEs remained a powerful tool to boost growth in areas that would have otherwise lagged behind, in 1995 the Chinese government began privatising them.

Finally, it is important to notice that township and village enterprises (TVEs) are different from cooperatives in Viet Nam. They are managed as companies, with a CEO and board (the community government) and shareholders (the villagers). In that, they go beyond the provision of services to farmers, but they collectively administer inputs as enterprises to sell output on the market, maximise profits and redistribute dividends.

Source: (Qian, 2002[15]; Xia, Li and Long, 2009[16]).

Finally, the government may facilitate the emergence of spontaneous, informal and collaborative groups to enhance co-ordination among smallholdings. Farmers tend to avoid formal types of horizontal collaboration. Co-operatives, for example, remain unpopular because, in spite of reforms that have changed their mandate, they are still associated with centrally steered delivery units that set production quotas, imposing restrictions and limiting production autonomy (OECD, 2015[1]). Other mechanisms that are supposed to mobilise farmers, such as the Viet Nam Farmers Union, remain weak at the grassroots level and only operate in an administrative manner at the central level (OECD, 2015[1]). Instead, spontaneous and flexible groups of neighbouring farmers often emerge to co-ordinate the use of natural resources, and manage soil preparation and irrigation, even if they have no power to conduct business activities on their own (Wolz and Duong, 2010[17]).

Upgrading to Industry 4.0: The future of manufacturing and the role of services

Viet Nam needs more sophisticated and dynamic manufacturing firms to further integrate into the global value chain

The manufacturing sector of Viet Nam has become more strategically important as the country pursued further integration into global value chains. From 1975 through to the end of the 1980s, Viet Nam was a commodity-based economy with highly regulated agricultural production. With the Ðổi Mới reforms and the normalisation of relationships with China and the United States at the beginning of the 1990s, the textile and electronic sectors – along with the types of services required for commercialisation – gradually emerged. Today, electronics, textiles and machinery account for almost 70% of all export flows. Several trade agreements and accession to the WTO have driven electrical machinery and equipment exports, which increased from 10% in 2010 to around 40% in 2017.

New trade linkages with the United States could help improve Viet Nam’s industrial sophistication. The supply chain connecting Viet Nam and the United States is traditionally “short”, requiring few intermediaries. Apparel, footwear and furniture, for example, still account for 40% of total exports from Viet Nam to the United States. However, the trade relationship is becoming more sophisticated and exports of electrical machinery and equipment are on the rise, accounting for 24% of total exports, while flows tripled between 2010 and 2015.

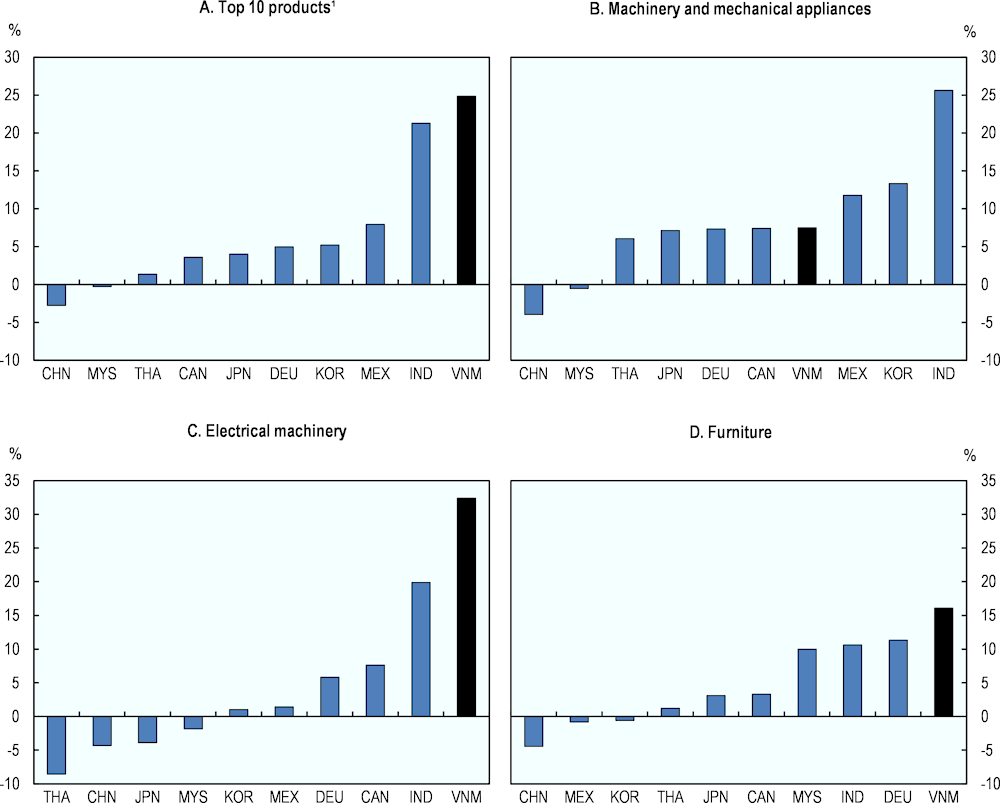

Contentious future relations between the United States and China will likely strengthen this relationship. Between 2017 and 2019, US imports of electrical machinery and furniture from Viet Nam increased by 30% and 15%, respectively, while flows from China shrank significantly (Figure 4.5). At the same time, businesses in China – including US PC giants HP and Dell, as well as software and service-based Amazon, Google and Microsoft – will gradually pull out of China and shift assembly lines towards Viet Nam (Nikkei Asian Review, 2019[18]).

Figure 4.5. US imports of electronics and furniture from Viet Nam have intensified amid rising trade tensions

Note: Based on the HTS2 classification. The top 10 products accounted for 68.6% of total US imports in 2019H1. These products include machinery and mechanical appliances, electrical machinery, vehicles, mineral fuels, pharmaceutical products, textiles, plastics and organic chemicals.

Source: United States International Trade Commission.

To benefit fully from these trends, Viet Nam will need to build a strong fabric of productive firms that can insert themselves into global value chains. China and Thailand provide examples of successful integration into GVCs by local firms. Thailand has been able to deepen its integration in the automotive global value chain and produces increasingly sophisticated car parts domestically. In China, local firms have swiftly taken the lead in many domestic and global value chains (e.g. exports of mobile phones produced by Chinese brands increased from 1% in 2007 to 21% in 2015). A key factor of success in both countries was the decision of domestic firms to source services from local suppliers, which helped to co-ordinate the value chains in which both countries participated (UNIDO, 2018[19]).

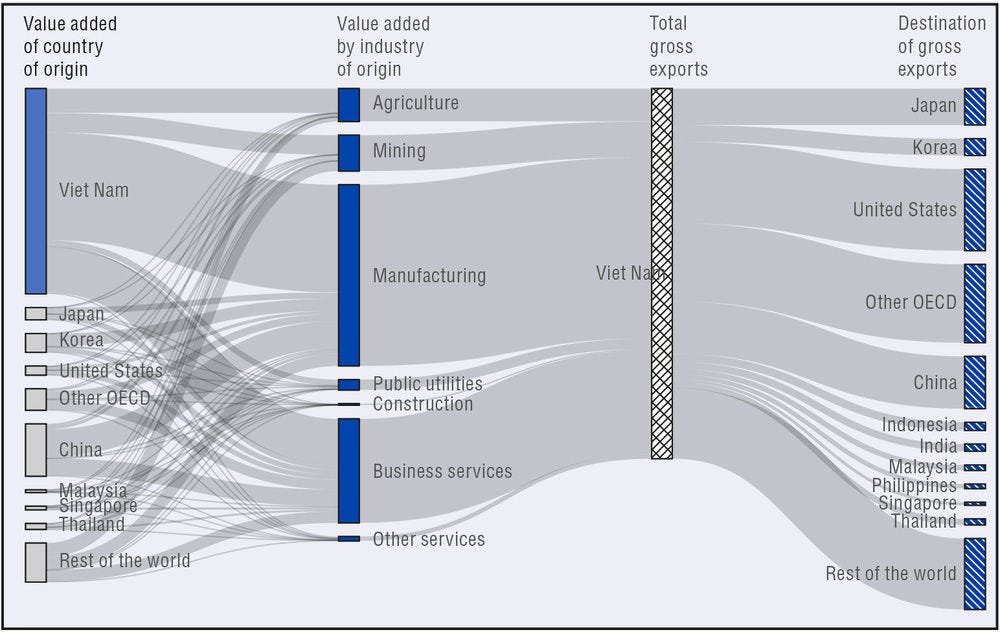

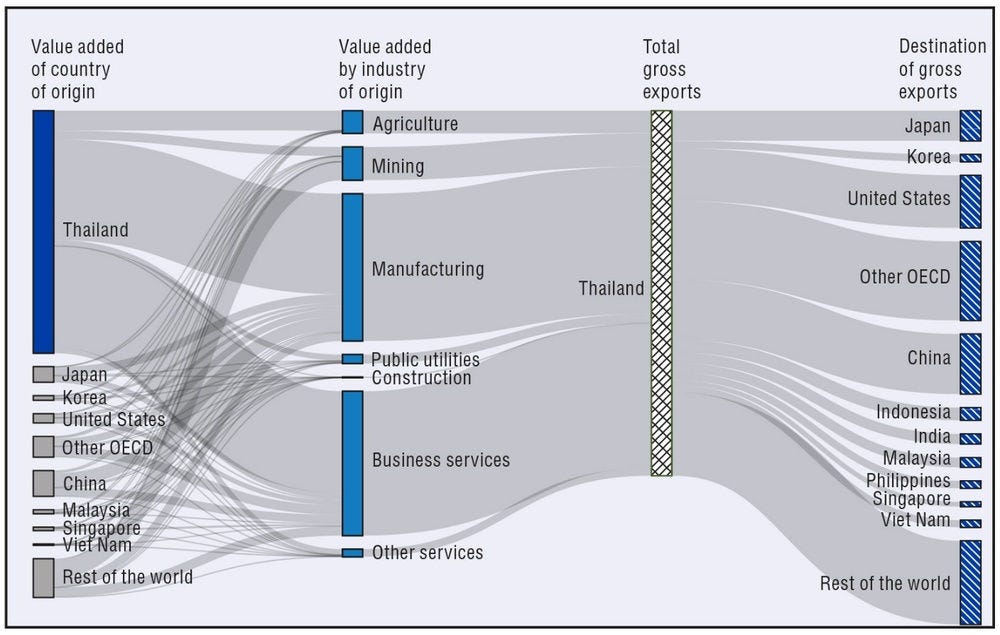

To date, the contribution of Viet Nam’s domestic companies to exports is low, especially compared to neighbouring countries. The decomposition of Viet Nam’s gross exports allows for a detailed analysis of the source of inputs in terms of sectors and countries of origin. The value added created by Vietnamese companies and embedded in foreign exports decreased from 64% of total exports in 2005 to 55% in 2015 (Figure 4.6), significantly lower than in Thailand (66%, Figure 4.7). At the same time, the share of exported value added generated in China increased from 5% to 14% over the same period. In 2015, Vietnamese companies also sourced inputs in Korea (5% of total gross exports) and the United States (3%).

Figure 4.6. Decomposition of Viet Nam’s gross exports by origin and destination, 2015

Source: OECD (2018), TiVA Database.

Figure 4.7. Decomposition of Thailand’s gross exports by origin and destination, 2015

Source: OECD (2018), TiVA Database.

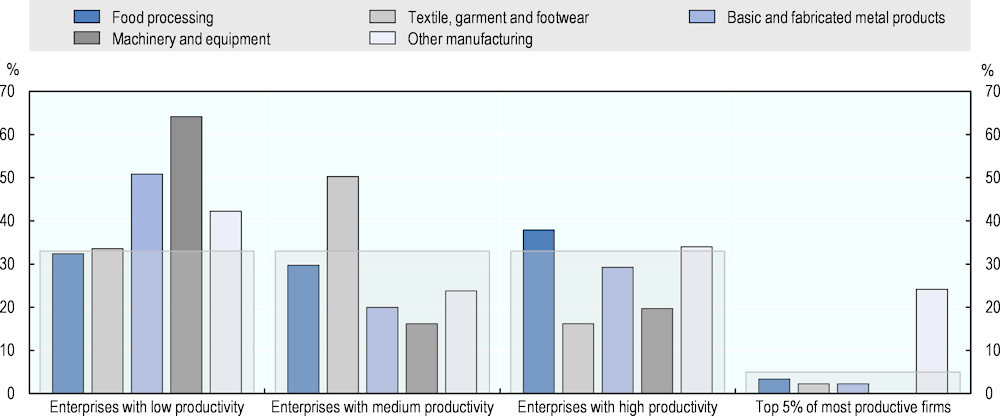

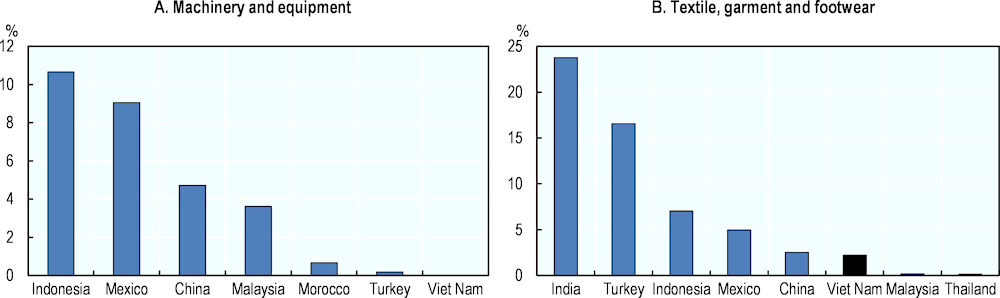

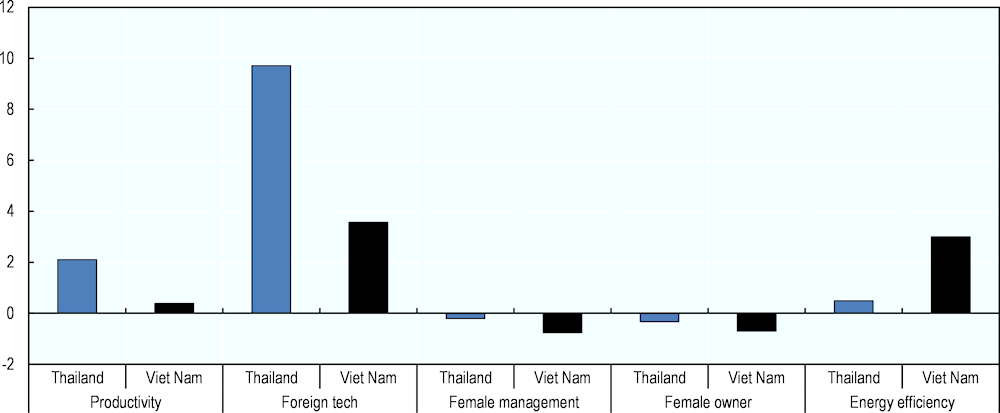

At the firm level, Viet Nam’s performance matches global rates in only a few sectors. Estimations suggest that just a small number of companies operate near the global productivity frontier, with most private manufacturing firms displaying low or medium productivity. Enterprises engaging in food processing or the manufacturing of chemical, rubber and plastic products perform particularly well and are among the most productive among global peers. In fact, manufacturers of chemical, rubber and plastic components are more productive than 95% of their global peers, placing them on the global productivity frontier (Figure 4.8). However, more than 60% of the suppliers of machinery and equipment exhibit very low productivity when compared to other countries, while half of textile, garment and footwear producers display only medium productivity. In fact, there are no or very few Vietnamese manufacturers in these two sectors, which are instead populated by enterprises from Indonesia and Mexico, and India and Turkey, respectively (Figure 4.9, Panel A and Panel B, respectively).

Figure 4.8. Vietnamese private companies are close to the global productivity frontier in few activities, but productivity remains low across sectors

Note: The global distribution of enterprises is divided into four groups, represented by the shaded areas: 33% of firms with low productivity, 33% with medium productivity, 33% with high productivity, and finally the 5% most productive firms – that is, the productivity frontier. If the distribution of Vietnamese firms followed the global distribution, 33% of the firms would fall into each of the tiers, and 5% would be at the global productivity frontier. The closer the distribution of Vietnamese firms to the frontier, the more productive the country. The entire methodology is described in (OECD, 2018[20]).

Source: Authors’ calculations based on World Bank (2017), Enterprise Survey (database), www.enterprisesurveys.org/data.

Relying on firms with low productivity is a sensible model for initial development, but will jeopardise industrial upgrading over the long term. Firms with low productivity usually specialise in labour intensive activities or products that are abundant and uniform. Their comparative advantage in the market is not the quality of the product but rather stems from the cheap labour force employed during the production phase. Encouraging this type of manufacturing has played an important role in initiating structural transformation in Viet Nam and other emerging countries. It gives domestic firms an opportunity to catch up swiftly and, if linkages with multinationals exist, to learn from production systems in other more advanced economies. However, over the long term, the lack of a dynamic fabric of private firms, a highly qualified labour force or investments to reinvigorate the productivity of the supply chain may jeopardise industrial upgrading. Other countries in the world with a cheaper labour force could divert foreign investors away from Viet Nam, excluding it from the market of labour intensive goods and activities, and with few opportunities to build linkages. Strategies to stimulate a domestic service sector, and to attract and retain FDI, are key to avoiding this scenario.

Large private corporations can play an important role in catalysing productivity gains and technological catch-up, but also make a strong regulatory and governance framework necessary. A few large private conglomerates have emerged in Viet Nam and play an increasingly important role in the economy. Each one spans several sectors, mostly targeting the domestic market in real estate, medical care, education and hospitality, but increasingly also manufacturing activities in sectors characterised by global competition and value chains. The Vin Group, for example, has recently begun expanding into the production of cars and smartphones and aims at the electric mobility market (Financial Times, 2019[21]). The emergence of such groups attests to the capacity of Viet Nam to generate sizeable private corporations that have the potential to accumulate capital and capabilities and generate the economies of scale that can drive productivity gains and global competitiveness. These groups can thus become an important cornerstone of Viet Nam’s economy and technological development. Making the most of their potential for Viet Nam’s development will require a strong regulatory function that is capable to assert equal treatment for all firms to ensure that markets remain contestable and open to innovation and competition. Without such regulatory strength, a few large groups pose the risk of capture and dominance.

Figure 4.9. The number of firms at the productivity frontier remains low in certain strategic sectors when compared to other countries

Note: The entire methodology used to identify firms at the productivity frontier is described in (OECD, 2018[20]).

Source: Authors’ calculations based on World Bank (2017), Enterprise Survey (database), www.enterprisesurveys.org/data.

Services and foreign investors can be leveraged for industrial upgrading

Good services, especially business process outsourcing (BPO), help firms to optimise their production systems, enhance their performance and improve the quality of their products (OECD, 2014[22]). BPO providers allow firms to outsource non-core tasks and to focus on core competencies. This is especially relevant for SMEs, which normally face the most severe constraints in terms of access and management of input, resources and information. BPO services such as software research and development (R&D), call centres, payroll, order classification and processing have grown by 20-35% annually over the past decade. The sector is also attracting more and more international players. For example, Viet Nam became the second largest offshore software (R&D) partner for Japan in 2016, surpassing China. Increases in skilled labour force may fuel the development of other services such as accounting, payroll management and customer services (PWC; VCCI, 2017[23]).

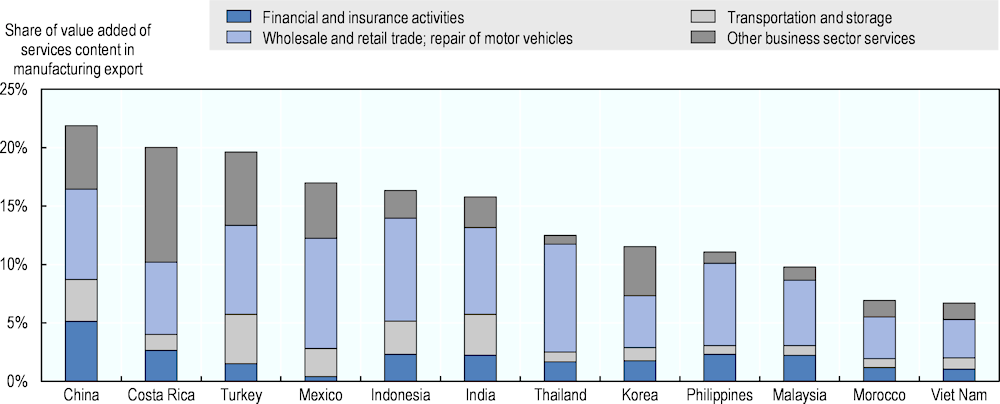

In spite of its strategic importance, the services sector in Viet Nam does not yet play a pivotal role in domestic development. It accounts for around 44% of GDP, which is low compared to countries at the same level of development, and employs some 19 million workers (more than 30% of the labour force). One-third of services activities relate to wholesale and retail trade, followed by financial, banking and insurance activities (13% of services contribution to GDP), real estate business (11%), education and training services, and accommodation and catering services (7% each). These activities supported Viet Nam’s emergence as an assembly platform and its integration into the global economy, but their value added remains low. Revenues from BPO services in 2015 were approximately USD 2 million, one-eleventh that of the Philippines (USD 22 million), the biggest BPO player in Southeast Asia, and the third globally after India and China. The weakness of the domestic service sector partly explains the lower position of Viet Nam in manufacturing global value chains. Only 6% of the value added created by the service sector and embedded in manufacturing export is created in Viet Nam, compared to 22% in China and 20% in Costa Rica (Figure 4.10). In these countries, the contribution of the service sector to manufacturing sector increased by more than 10 percentage points between 2006 and 2015. Domestic services are particularly weak in sub-sectors that support Viet Nam’s integration with global markets – such as logistics, transport, insurance and finance – and represent a major obstacle to the country’s upgrading in GVCs (Jaax et al., 2020[24]).

Figure 4.10. The value added of the domestic services sector embodied in manufacturing export remains low in Viet Nam

Note: The category “Other business sector services” include real estate activities; publishing, audiovisual and broadcasting activities; information and communication technology; accommodation and food services; other unspecified business sector activities.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on the TiVA database.

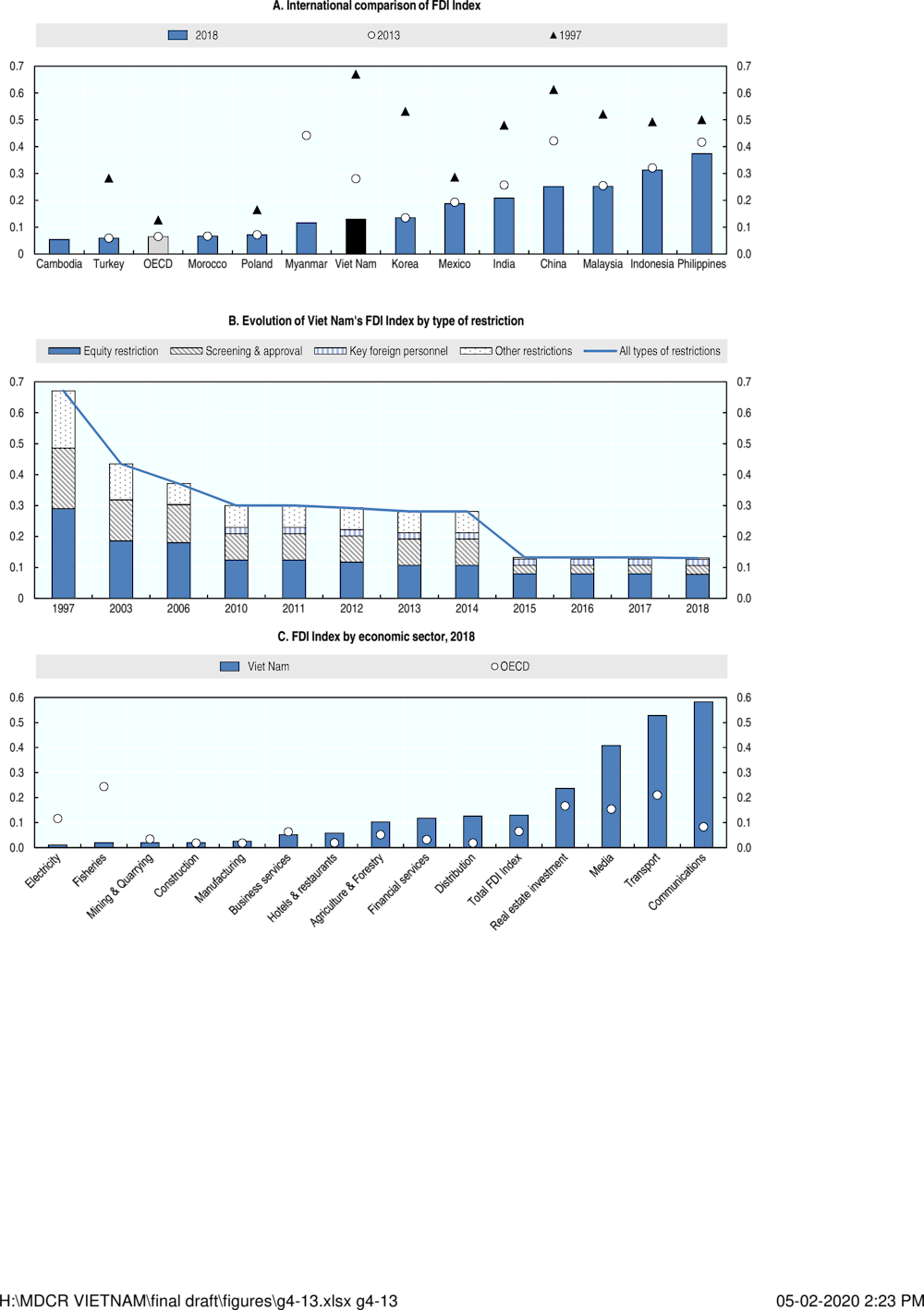

Foreign investment could contribute significantly to upgrading the productive capabilities of the manufacturing and services sector. In 2017, the net investment inflow accounted for 6% of GDP, the fourth highest value in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), after Singapore, Cambodia and Lao PDR, and the 33rd highest in the world. In 2017, foreign investments targeted mostly the manufacturing sector and real estate activities (47% and 23% of the total registered capital, respectively). Tourism has also played an important role: between 1995 and 2017 it accounted for 6% of the total registered capital on average, but the ratio peaked in 2009 (40%) during the financial crisis. Some multinational enterprises have also opened international markets and global value chains (GVCs) to domestic firms through the creation of linkages. Intel, for example, has directly created thousands of high-skilled jobs and generated significant export revenues. It has, moreover, laid the foundations of a high-tech cluster that could help Viet Nam climb the technology and value added ladders (Fulbright University Vietnam, 2018[25]).

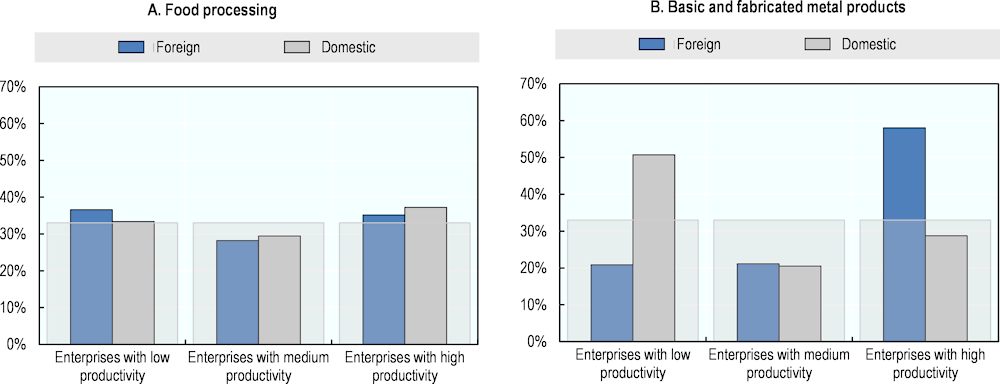

Some FDI still targets low-tech activities that do not require investment in R&D or workers with particularly high skills. As a result, the advantage in terms of FDI productivity with respect to domestic companies in some manufacturing sectors – such as food processing – is not as stark as in others – like basic and fabricated metal products (Figure 4.11). Moreover, FDI could have a broader social and environmental impact that goes beyond the incentives of profit-seeking investors. Since 2003, more than 90% of all energy FDI targeting Viet Nam went into fossil fuels, and the energy sector is still a significant polluter in terms of CO2 emissions. A strategy that takes into account the environmental footprint of FDI could facilitate the transition to a low-carbon energy infrastructure by envisaging different fossil fuel support measures or correcting regulations that weaken the case for investment and innovation in low-carbon infrastructure.

Figure 4.11. Foreign companies perform much better than their domestic private counterparts, at least in some sectors

Note: A company is classified as foreign if foreign investors retain more than 10% of the firm’s capital. The global distribution of enterprises is divided into three groups, represented by the shaded areas: 33% of firms with low productivity, 33% with medium productivity and 33% with high productivity. If the distribution of Vietnamese firms followed the global distribution, 33% of the firms would fall into each of the tiers. The closer the distribution of Vietnamese firms to the frontier, the more productive the country. The entire methodology is described in (OECD, 2018[20]).

Source: Authors’ calculations based on World Bank (2017), Enterprise Survey (database), www.enterprisesurveys.org/data.

Foreign services could help compensate for a relatively small and inexperienced domestic service sector. The government have put in place a variety of measures to attract foreign BPO operators. Resolution No. 41/NQ-CP dated 26 May 2016 guarantees a preferential 10% corporate income tax rate for 15 years for new projects entailing the provision of business services and the employment of 1 000 people. High-tech parks offering technology infrastructure (e.g. fibre optic internet), human resource training centres and special incentives have been inaugurated in Da Nang, Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City (PWC; VCCI, 2017[23]). As a result, Viet Nam has been sourcing foreign services such as transport (51% of service imports in 2015), travel services (21%), insurance and financial services (9%), other business services (5%), construction (4%) and telecommunications and information services (1%). The main trading partners are the United States, Japan (both 12%), the European Union (11%), Australia (7%), and China (2%) (Jaax et al., 2020[24]).5 In 2017, Specialist Computer Company – the largest privately owned ICT services and solutions provider in Europe – opened a new Global Delivery Centre (GDC) in Ho Chi Minh City to provide infrastructure technical support for customers and house a software development centre.

Moving forward: A four-pillar framework for upgrading productive capabilities

Create an environment of equal opportunity for everyone in the economy

Implementing the numerous laws and measures aimed at creating a conducive business environment

A poor business environment has long been the main determinant of disappointing productivity among manufacturing firms in Viet Nam. In particular, OECD estimations based on historical data from World Bank enterprise surveys and surveys conducted among small and medium enterprises between 2010 and 2015 suggest that low quality of the labour force, lagging accessibility to Internet, inefficient public administration, high corruption incidence and poor access to finance significantly impaired firms’ productivity (Giang et al., 2018[26]).

Distortions have discouraged private investments, industrial upgrading and the consolidation of a domestic industrial fabric. In particular, administrative burdens seem to affect mostly large firms and create incentives for existing enterprises to remain small (Ha, Kiyota and Yamanouchi, 2016[27]). Interviews conducted as part of this Multi-dimensional Review indicate that as a result of burdensome administrative procedures affecting mostly large firms, successful enterprise owners prefer to use profits to create new enterprise rather than reinvesting them to upscale existing firms. As a consequence, approximately 85% of Vietnamese companies have fewer than 50 employees and just under half (49%) have fewer than 10 employees. The average employment size is about 17 employees, and the overall trend is downward. Size is not all, but lack of scale undermines investments: eight out of ten private companies have less than VND 5 million invested (USD 222 000) and the median firm has VND 17.4 million (USD 75 600) (Malesky, Ngoc and Thach, 2017[28]).

Viet Nam has invested significant efforts in improving the business environment (Table 4.3). Since 2014, the government has set yearly targets with respect to governance quality, competitiveness, innovation and e-government. The ultimate goal is to match the quality standards of Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand and the Philippines (the so-called “ASEAN 4”), as measured by Doing Business Ranking (Resolution 19). At the same time, the state has laid down strategic steps for the consolidated implementation of various reforms in administrative processes, such as taxation, customs, social insurance, construction licenses, land registration, electrical access, corporate establishment and closure, and investment procedures. Instructions are provided for relevant ministries such as the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Transport and the Ministry of Public Security to implement a one-stop shop (OSS) mechanism and improve the use of online portals for administrative tasks. This approach represents a follow-up to Project 30 (2007-2010) on simplifying administrative procedures through the application of one-stop shops, e-OSSs, multi-level OSSs, multi-sector working groups and ISO 9001:2000.

Table 4.3. Viet Nam has undergone a comprehensive process of business environment enhancement

|

Year |

Actions |

|---|---|

|

2014 |

Resolution No. 19/2014/NQ-CP dated 18 March 2014 on major tasks and solutions to improve the business environment and national competitiveness. |

|

2015 |

Resolution No. 19/NQ-CP dated 12 March 2015 on key tasks and solutions to continuing to improve business environment and national competitiveness for two-year period of 2015 – 2016. |

|

2016 |

Resolution No. 19/2016/NQ-CP dated 28 April 2016 of the Government on the key tasks and measures to improve business environment and enhance national competitiveness in two years 2016 - 2017, with an orientation to 2020. Resolution No. 35/2016/NQ-CP dated 16 May 2016 on supporting and developing enterprises towards 2020. |

|

2017 |

Resolution No. 19/2017/NQ-CP dated 6 February 2017 on key tasks and measures to improve business environment and enhance national competitiveness in 2017, with an orientation to 2020. Directive No. 20/CT-TTg dated 17 May 2017 on rectifying inspection activities for enterprises was issued. Directive No. 26/CT-TTg dated 6 June 2017 on the continued implementation of Resolution No. 35/NQ-CP (2016) in the spirit that the Government accompanies enterprises. Viet Nam’s National Assembly passed Law No. 04/2017/QH14 on support for small and medium-sized enterprises. |

|

2018 |

Resolution No. 19-2018/NQ-CP dated 1 May 2018 on continued implementation of major tasks and solutions to improve the business environment and national competitiveness in 2018 and the following years. The SME law entered into force. The National Assembly adopted Viet Nam Competition Law No. 23/2018/QH14, replacing Viet Nam Competition Law No. 27/2004/QH11. |

|

2019 |

The amended Viet Nam Competition Law entered into force. Resolution No. 02/NQ-CP dated 1 January 2019 on “Continued implementation of major tasks and solutions to improve the business environment and national competitiveness in 2019 - vision 2021”, was issued. |

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

In 2016 and 2017, the government took further steps to support and develop enterprises. Following the 12th Party Committee, Viet Nam recognised the need to develop an economy based on knowledge, innovation, high technology and sciences in which enterprises, particularly private ones, are key to boosting national competitiveness and autonomy (Resolution No. 35/NQ-CP, Directive No. 26/CT-TTg and Directive No. 20/CT-TTg). A number of principles were devised to ensure the predictability of policies, stabilise the macroeconomic framework, and secure an overall safe, conducive and business-friendly environment. The Ministry of Planning and Investment, in co-ordination with the Steering Committee for Enterprise Innovation and Development of other ministries and relevant agencies, was appointed to evaluate, inspect and supervise the implementation of policy recommendations. In May 2017, the Prime Minister urged the revision of inspection activities to prevent redundant and overlapping inspections interfering with the operation of enterprises (Directive 20).

In 2017, the National Assembly passed the Law on Support for SMEs (SME Law), which is the first of its kind in Viet Nam and replaces all previous decrees on SMEs. The law provides several measures to support the development of SMEs, such as access to credit, credit guarantees, corporate income tax and land use for production. It also mentions technological support in the form of incubators and start-up hubs, market expansion, information and legal support, and human resource development. In accordance with the SME law, support has been prioritised for women-led, household and innovative SMEs.

Since 2018, an amended version of the 2004 Viet Nam Competition Law has addressed the new market situation. In comparison to the 2004 law, the revised version broadens the definition of anti-competitive behaviour, introduces new thresholds to define economic concentration, imposes new regulations on the time limit for dealing with breaches of competition law, and defines specific sanctions for violation of the Competition Law. The National Competition Commission was also designated the agency responsible for enforcing the Competition Law.

In early 2019, the government issued Resolution No. 02/NQ-CP to review the five-year implementation of Resolution No. 19. The resolution also sets out further solutions and tasks to improve the business environment and national competitiveness. The document mentions 71 concrete targets that central and local authorities need to achieve in order to improve the business environment. Moreover, the Viet Nam Association for SMEs and other enterprise associations have been tasked with regularly and independently monitoring and evaluating implementation of this resolution. The resolution further emphasises the goal of matching the quality of the business environment in the “ASEAN 4”.

Due to this major policy effort, the quality of the business environment in Viet Nam has improved rapidly. Over the past 10 years, the country has climbed 23 positions in the World Bank Ease of Doing Business indicator – from the 92nd to the 69th out of 190 countries. Viet Nam’s global ranking in terms of the burden of government regulation, as measured by the World Economic Forum, also rose climbing from 120th position in 2010-11 to 79th in 2018-19, out of nearly 140 countries. The 2018 Provincial Competitiveness Index (PCI) report shows that 76% of firms agreed with the statement “My provincial People’s Committee is very flexible, within the scope of laws, to create a favourable business environment”, the highest level in the last five years. In particular, both “petty corruption” and “grand corruption” abated in 2018. The environment is also more competitive, with less firms lamenting the favouritism of provincial authorities towards state corporations or foreign investors. Government efficiency in handling administrative procedures is also improving (Malesky, Ngoc and Thach, 2017[28]).

However, in spite of the impressive number of reforms produced, their implementation has been lagging. The country is currently ranked 28 places below its target for “ease of doing business” based on the performance of the “ASEAN 4” (Resolution No. 19). The 2019 Index of Economic Freedom produced by the Heritage Foundation also supports this point, ranking Viet Nam 128th out of 180 countries and categorising the economy as “mostly unfree” (Kane, Holmes R. and O’Grady, 2019[29]). The Office of the Government itself acknowledges limitations with regard to the implementation of Resolution No. 35/NQ-CP and Directive No. 26/CT-TTg. In particular, inconsistent pieces of legislation have yet to be fully resolved, with overlapping inspections and examinations, and limited access to resources including capital, land, natural resources and minerals still major concerns.

Effective implementation of pro-business laws and measures will require adjusting the incentives for provincial leaders and bureaucrats. Investment promotion in Viet Nam is mostly decentralised and provinces are left to compete for foreign investors by lowering standard requirements and tax rates. Provincial leaders, moreover, have stakes in local SOEs, which then enjoy more favourable conditions, for example, in terms of access to land and information. Special treatment for FDIs and local SOEs comes with tougher conditions for domestic private enterprises. Private companies are more likely than foreign companies or the state sector to pay bribes, for example, at registration (Gueorguiev and Malesky, 2012[30]; Nguyen, 2012[31]). Chapter 8 discusses how to realign the incentives of local provinces to attract quality foreign investments, enhance SOE performance and ultimately build a conducive business environment.

From the point of view of the private sector, the public administration remains cumbersome. While registering a firm is not a complex procedure, an alarming share of firms claim to experience difficulty with completing post-registration administrative procedures, or with obtaining qualification certificates or certificates proving technical-regulatory conformity (Malesky, Ngoc and Thach, 2017[28]). As a result, companies are often forced to rely on informal and costly short cuts (e.g. bribes, gifts or political connection) to circumnavigate burdensome and obscure administrative procedures. Political connections are, moreover, essential to secure bids for government contracts. Capture is more burdensome for large firms with sizeable profits, further discouraging investment and upgrading.

Digitalisation and e-governance could facilitate implementation

Digitalisation of administrative procedures and services could simplify interactions between companies and the public administration and hence cut red tape. Efforts to improve e-government through open information, better transparency and reduced face-to-face contact with government officials could help businesses obtain better services and minimise corruption. Such efforts are proliferating around the world, as in the case of many OECD countries such as Colombia, Korea and Mexico, among others, with the promise of reducing corruption (Klitgaard, 2015[32]).

Viet Nam has made a strong policy commitment to pushing forward e-government through the agenda of the fourth industrial revolution (Industry 4.0). The government has issued numerous policy documents (namely Resolution No. 36/2015/NQ-CP in 2015 and Resolution No. 17/2019/NQ-CP in 2019) to outline the targets, tasks and guidance necessary for the development of digital government. The Office of the Government has been assigned the leading position in monitoring implementation across government agencies, while the Ministry of Information and Communication is to set technical standards with several other ministries providing support in specific areas. In 2018, the National Committee on E-government, headed by the Prime Minister, was established, replacing the National Committee for Information Technology Application. The committee is composed of ministers and deputy ministries from relevant ministries, as well as the leaders of major ICT companies in Viet Nam. In the same year, the National Assembly approved the amendments to the Law on Cyber Security.

In spite of impressive progress, e-government remains in its infancy. Viet Nam climbed 11 ranks in the E‑gov Development Index between 2014 and 2018 according to UN E‑gov surveys. It has started to build and operate national databases to gather information about enterprise registration and access to online services – such as registration of enterprises, tax declarations and deposits, social insurance. In early 2019, the Prime Minister launched the national e-document exchange platform. However, take-up rates vary significantly across provinces with some enterprises using e‑gov platforms only infrequently.

To ensure e-government success, much more needs to be done to (i) improve the co-ordination framework by mainstreaming e-government into overall efforts; (ii) develop the technology infrastructure and related standards; (iii) enhance capacities within the public sector; and (iv) move towards a more citizen and business-centric approach.

Although Resolution No. 17/2019/NQ-CP maps out the responsibilities of different ministries in e-government development, greater efforts are needed to improve the co-ordination mechanism, which is essential for successful e-government implementation. A ““Chief Information Officers’ (CIO) council” of ICT directors exists at both national and local levels; however, there is no government-wide CIO, which might lead to ambiguity in communicating the scope of work between ICT directors and the top government leadership (World Bank, 2019[2]). In addition, the perception of e-government is positive but is present in only some agencies instead of consistently as part of an overall approach. The benefit of e-government is, therefore, only partially realised and not yet fully exploited. In OECD countries, governments have increasingly moved from considering e-government as a single function to recognising the need for mainstreaming e-government into overall efforts. Whole-of-government structures can play an important role in steering and co-ordinating e-government implementation across government, in providing a framework for collaboration across agencies, and in keeping e-government activity aligned with broader public administration agendas (OECD, 2003[33]).

In spite of technical improvements, the framework on technology infrastructure and related areas is still lacking. The Ministry of Information and Communication has issued e-government architecture standards and identified the need to develop six key national databases for future data-sharing as a foundation for digital government. Furthermore, a number of agencies have begun using emerging technologies such as big data and analytics and cloud computing. However, there are as yet no clear standards or policies in important related areas such as the government cloud, government data management, government ICT procurement or government information systems interoperability, all of which constitute the components of a government digital platform offering economies of scale (World Bank, 2019[2]).

The government should identify skills gaps and put forward policies to strengthen skills assessment and development across government agencies. To do so, it can build on some OECD best-practices (Box 4.3). E-government skills should not be considered as technical matters best left to specialists, but rather core capacities of every civil servant to support successful e-government implementation, full exploitation and leveraging of e-government projects, and advances in the modernisation agenda (OECD, 2003[33]). At present, top talent in the country gravitates primarily towards the private sector where salaries are higher, which makes it difficult for government agencies to attract and retain such individuals (World Bank, 2019[2]).

Box 4.3. United Kingdom: e-Envoy and information skills map

The Office of the e-Envoy in the United Kingdom has outlined a skills map as part of the United Kingdom Online Strategy to prepare the United Kingdom government agencies for e-government adoption. The e-Envoy has defined seven areas for skills development: leadership, project management, acquisition, information professionalism, ICT professionalism, ICT-based service design and end-user skills.

The e-Envoy has produced a skills assessment toolkit to determine the e-readiness of each agency. The toolkit has been used by departments for self-assessment to gain an understanding of the skills required for planning, implementing and delivering e-government services. The assessment identifies the skills available internally through in-house technology and information professionals, and identifies skill gaps that may need to be addressed by expanding staff or outsourcing.

Source: (OECD, 2003[33]).

OECD studies point to the fact that better government is simply more user-focused e-government where services and interests are aligned with citizen and business needs (OECD, 2009[34]). In general, the Vietnamese government has yet to maximise the use of available ICT platforms for service delivery to citizens. While the national e-procurement platform is in place, for example, many bidders tend to submit both paper and online documents, leading to even more burdensome procedures. Enabling societal-wide efficiency and effectiveness might strengthen the potential to better use public resources at large (e.g. to help improve public service delivery, enable citizens to better access services, reach out to vulnerable parts of the population and foster open government) without losing sight of the necessary focus on efficiency and effectiveness (OECD, 2009[34]).

Create partnerships for innovate

Domestic private firms in Viet Nam can evolve and further integrate into global markets depending on their dynamism and capacity to innovate. While the creation of a healthy business environment is important, enterprises must constantly update their product, brand and production processes to remain at the edge of the domestic and global productivity frontier. Universities and colleges can play a crucial role in this process. The research and innovation components of tertiary education are core elements of a country’s knowledge system, and collaboration between higher education and industry is essential to ensure that the research produced aligns with industry’s needs for innovation. Moreover, partnerships between firms and tertiary education could strengthen the role of institutions in local, national and global knowledge systems, and help them become more financially sustainable (OECD, 2019[35]).

Box 4.4. Wageningen University and StartLife in the Netherlands: Innovation in the agro-industry

The University of Wageningen in the Netherlands is a mid-size university with around 12 000 students and 6 500 employees from more than 100 countries. The university’s educational programmes and research cover three related areas, "food and food production", "living environment" and "health, lifestyle and livelihood", offered across several campuses in the Netherlands and abroad.

Since 1995, the University of Wageningen has supported start-ups. At present, around 20 start-ups collaborate with the institution. As of September 2016, all associated research centres were linked and rebranded as "Wageningen University & Research", providing them with a common interface for investors, companies, and students and researchers, who would like to start a business.

Wageningen University & Research partners with StartLife, an expert organisation that provides support for new firm creation in food and agrotech. The founding partners of StartLife are Wageningen University and the regional government. Key business partners include Unilever, Metro and Lidl.

Universities can accompany companies throughout their lifecycles. For example, university-firm partnerships allow tertiary institutions to incubate student start-ups (Box 4.4), helping new entrepreneurs to develop the skills they need to discover new market or product opportunities, consolidate and expand. In cases where lack of funding is a barrier to firm-level innovation, subsidies to firm-level innovation activities (e.g. innovation vouchers) can also be an effective mechanism to stimulate innovation in firms (Box 4.5).

Box 4.5. Innovation Voucher PLUS programme in Austria

Innovation Voucher PLUS is a funding instrument designed to help small and medium-sized enterprises in Austria engage in ongoing research and innovation activities. The programme enables enterprises to enlist the services of research institutions and to pay for these services up to a maximum value of EUR 10 000. The Innovation Voucher is designed to encourage SMEs to co-operate with research institutes, and should make it easier for them to overcome inhibition thresholds regarding co-operation with higher education institutions and other public and private research institutions.

Evaluations of Innovation Voucher have demonstrated success in several areas:

stimulating knowledge transfer between SMEs and the science sector

closing the knowledge gap between research organisations and SMEs

overcoming SMEs’ reluctance to contact and work with research organisations

building SMEs’ capacities to co-operate with research organisations.

The Innovation Voucher is a straightforward and easily accessible instrument, and proved particularly successful with small firms as well as those with no prior experience of funding or innovation agencies.

Source: OECD STIP, https://stip.oecd.org/stip/policy-initiatives/2017%2Fdata%2FpolicyInitiatives%2F3828; Technopolis, innovation voucher, small is beautiful www.researchgate.net/publication/303894044_Innovation_voucher_-_small_is_beautiful.

To effectively support the creation of new firms, tertiary education institutions must create an institutional culture and set of procedures that leverage existing education and research functions to enhance creativity and idea generation. They also need to build strategic partnerships with organisations that support the creation of new firms (OECD, 2019[35]). Establishing these procedures and developing an entrepreneurial culture takes time and requires continuous support from (OECD/European Union, 2019[36]) university leadership to assist those individuals actively engaged in the exercise (often in addition to their actual work). To facilitate this process, the European Commission and the OECD have developed the “HEInnovate Guiding Framework”, an instrument to support universities, and higher education institutions more generally, develop an institutional culture and procedures that support innovation.

Chapter 6 provides further details about recommendations to foster collaborations between universities, businesses and the public sector to enhance knowledge transfer and innovation.

Promote services to support firms become more productive

The market for services is not well developed. As already noted, the service sector is indeed at its infancy. The problem lies in both the demand for and the supply of services, in particular BPO. As in all markets, demand and supply emerge when the need for these types of products and activities arise. However, entrepreneurs might not actually be aware of their need for these types of services.

Demand for BPO rises when entrepreneurs endogenously acknowledge the limitations of their companies and the consequent need for these types of services. To nudge entrepreneurs into seeing what they need, countries such as Singapore have developed business diagnostic tools that aim to assess the level of productivity and competitiveness of a firm with respect to peers in a certain sector or location. These tools are based on key values which user companies have decided to introduce (e.g. profit and number of employees) (Box 4.6). Other tools may provide a diagnostic within a certain area of importance to companies, such as innovation and digitalisation.

Box 4.6. Business diagnostics tools in Singapore

Enterprise Singapore was established to develop and provide a set of online digital diagnostic tools for SMEs, supporting the growth of committed companies and developing partnerships with trade organisations.

The “Business Excellence” initiative is a concrete example that illustrates the activities carried out by Enterprise Singapore. The agency created a simple online digital tool to assess the organisational performance of SMEs, according to an internationally benchmarked framework covering the following seven areas: i) leadership; ii) customers; iii) strategy; iv) people; v) processes; vi) knowledge; and vii) results. By using this digital diagnostic tool, any SME can identify its own strengths and areas for improvement in order to increase its performance and competitiveness. The SMEs with good performance are awarded various degrees of recognition to demonstrate their achievements and commitment to sustainable performance improvement. A strategic development roadmap to further improve the performance of SMEs can also be generated by the digital tool.

Enterprise Singapore has also developed and provided a wide range of other online “Business Toolkits” that allow SMEs to assess themselves and make appropriate diagnostics that take into account how well they are positioned in the following areas:

SME Financial Modelling is a digital tool designed to assess an SME’s situation in terms of financial management. It uses a toolkit that analyses financial capabilities while also addressing major areas of improvement and identifying specific resources that can be used to improve financial resilience.