Viet Nam aspires to develop a generation of tertiary educated graduates with outstanding technical knowledge and generic skills that permit continuous adaption to new technologies and business conditions. So far, it has aimed to achieve this skill profile in graduates through policies that encourage the importation of a new educational model, and through targeted support for individual tertiary education institutions. With more than two million students in tertiary education, an approach that will reach only thousands of learners is not sufficient. Instead, Viet Nam needs to reflect on how innovative, high quality and relevant provision can be broadly dispersed across its tertiary education system, at scale. The chapter reviews important accomplishment, discusses emerging challenges that have not yet been effectively addressed, and outline a rethinking – and practical steps – that public authorities can take to strengthen skills development and innovation.

Multi-dimensional Review of Viet Nam

6. Skills and innovation: Strengthening Viet Nam’s tertiary education

Abstract

Viet Nam has one of the most open economies in the world, and has experienced robust growth, a remarkable reduction in poverty and a reasonably equitable increase in living standards. The country also has a young and dynamic population 45% of which are under 30 years of age. Over recent decades, three major developments have reshaped the structure of employment: a rapid growth in manufacturing, a declining but still important agricultural sector and growth in services.

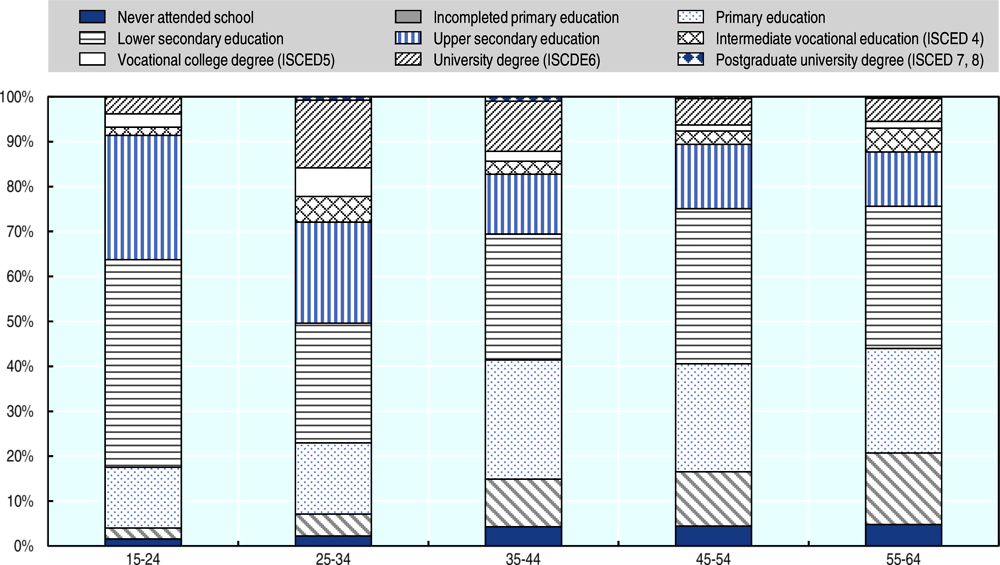

The historically high demand for low-skilled labour has resulted in a gap between employment in high-skilled occupations and jobs requiring low to medium skills (Figure 6.1, Panel A). This gap is closing, and according International Labour Organization estimates, employment in highly skilled occupations is increasing at a faster rate than in other occupations. The highest increase is expected for professionals, crafts and related trades, and plant and machine operators (Figure 6.1, Panel B). By 2023, employment in occupations requiring medium skills will surpass employment in low-skill occupations (ILOSTAT, 2018[1]).

Viet Nam’s economic growth presents both risks and challenges. Occupation-based estimates (Frey and Osborne, 2017[2]) suggest that 70% of jobs in Viet Nam are at a high risk of automation – a share that is higher than Malaysia (53%), Japan (49%) and Thailand (43%). Workers who have completed only primary school are 3.1 times more likely to be in a high-risk occupation than those with tertiary education attainment (Chang and Huynh, 2016[3]). New technologies and globalisation have resulted in new tasks and existing tasks are changing. Future jobs will require not only job-specific skills but also generic skills that are transferable to a wide range of occupations. Tertiary education in Viet Nam will have to respond to these developments.

Viet Nam’s government has addressed the country’s economic transformation by widening the scope of autonomy for tertiary education institutions, and expanding opportunities for study at the tertiary level in vocational colleges and universities. Pathways were created among vocational education institutions, and between vocational college and universities. The Government of Viet Nam has also engaged with the global higher education system by creating opportunities for foreign tertiary institutions to offer study programmes in Viet Nam, and by investing in efforts on the part of its universities to offer high-quality study programmes that can retain talented Vietnamese youth who might otherwise study abroad.

Notwithstanding these accomplishments, the analysis undertaken in this chapter suggests that tertiary education is not fully responsive to the emerging needs of Viet Nam’s society and economy. The following sections briefly review important accomplishments, discuss emerging challenges that have not yet been effectively addressed, and outline practical steps that public authorities can take to strengthen skills development and innovation.

Figure 6.1. Estimated trends in employment by occupation in Viet Nam (2018-23)

Note: ISCO-08 classification, detailed occupations. High-skilled occupations are defined as ISCO groups 1 (managers), 2 (professionals) and 3 (technicians and associate professionals); medium-skilled occupations include ISCO groups 4 (clerks), 5 (service and sales workers), 6 (skilled agricultural and fishery workers), 7 (craft and related trade workers) and 8 (plant and machine operators and assemblers); and low-skilled occupations consist of ISCO group 9 (elementary occupations). The employed comprise all persons of working age who, during a specified brief period, were in the following categories: a) paid employment (whether at work or with a job but not at work); or b) self-employment (whether at work or with an enterprise but not at work).

Source: ILOSTAT (2018), Employment by sex and occupation; ILO modelled estimates.

Key accomplishments and developments

Rising educational attainment within a comprehensive and co-ordinated education system

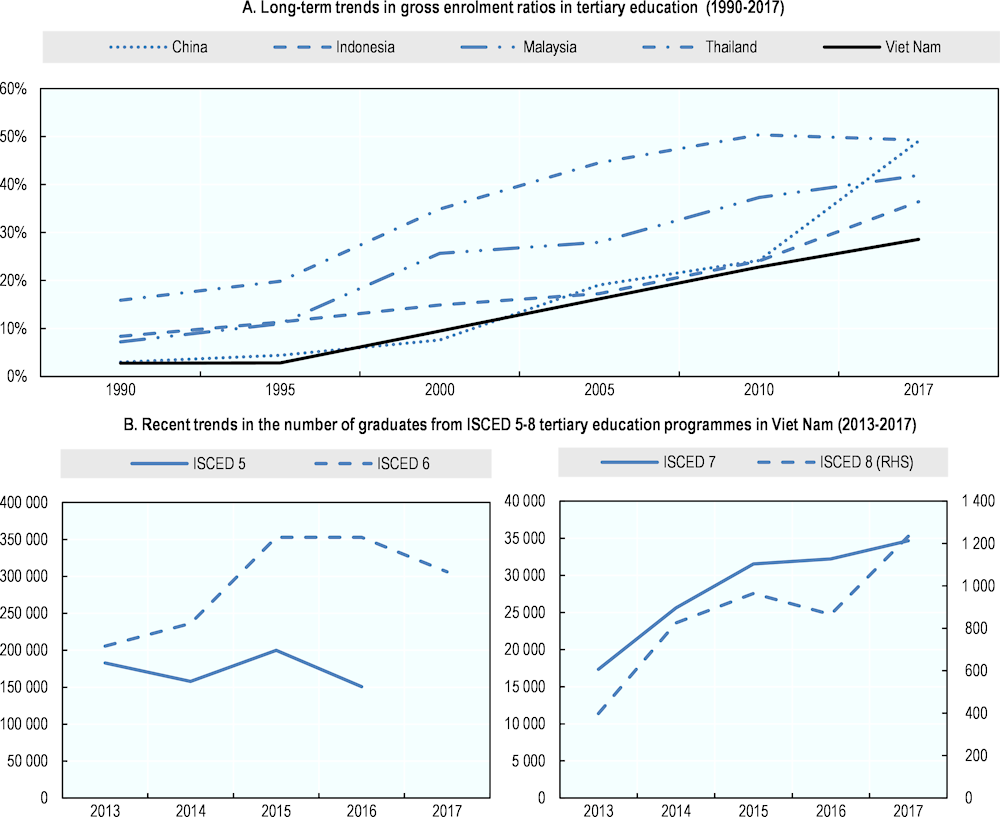

Younger cohorts in Viet Nam’s workforce have, on average, higher levels of educational attainment than older age cohorts (Figure 6.2). In 2018, the proportion of workers with primary education was almost two times higher among 35-44 year-olds (26.5%) than 15-24 year-olds (13.5%) and 25-34 year-olds (15.8%) (GSO, 2018[4]).

The most critical education choice in Viet Nam is whether to pursue additional education after completion of secondary education. The returns on upper secondary degree are modest, both in terms of the probability of finding waged employment and earnings (Demombynes and Testaverde, 2018[5]).

Figure 6.2. Highest educational attainment levels by age group in Viet Nam’s labour force (2018)

Box 6.1. Overview of Viet Nam’s education system from primary to tertiary education

Primary education (Tiểu học) from the age of 6 to 11 years is currently the only level of compulsory education in Viet Nam. The government also plans to make lower secondary education (Trung học cơ sở) compulsory by 2020. Access to upper secondary education (Trung học phổ thông) is regulated through an admission exam in which students have to choose between natural sciences and social sciences for the focus of their upper secondary education.

Students who complete upper secondary education (Trung học phổ thông) can choose to apply for a tertiary education programme or vocational education in the form of a one to two-year programme (Trung cấp chuyên nghiệp) at post-secondary non-tertiary level (ISCED 4) or at tertiary level. Students who want to enrol for university programmes (ISCED 5 or 6) need to pass a national admission exam, which covers six subjects. Mathematics, literature and a foreign language are compulsory; the three remaining subjects can be chosen from the natural sciences (physics, chemistry and biology) and the social sciences (history, geography and citizenship education). The completion of a professional technical programme also provides access to tertiary education.

Vocational education and training in Viet Nam is organised into three levels with several pathways into tertiary education. The existence of these pathways is commendable. With a lower secondary education completion certificate, students can enter vocational education and training at the elementary level (Sơ cấp nghề). After one year of training, students can continue enter three years of intermediate vocational education (Trung cấp nghề) and earn an intermediate vocational training completion diploma (ISCED 4), which gives them access to tertiary education.

Tertiary education programmes include the following:

General college programmes (Trình độ cao đẳng) have a theoretical duration of three years leading to a short-cycle tertiary education degree (ISCED 5). Entrance requirements are either an upper secondary education graduation diploma or a professional secondary education diploma and a successfully passed entrance exam.

Vocational college programmes (Cao đẳng nghề) have a theoretical duration of two to three years leading to a short-cycle tertiary education degree (ISCED 5). Entrance requirements are an upper secondary education graduation diploma or an intermediate vocational training completion diploma.

Bachelor’s degree programmes (Trình độ đại học) (ISCED 6) have a theoretical duration of either four or five years. Entrance requirements are either an upper secondary education graduation diploma or a professional secondary education diploma and a successfully passed entrance exam.

Master’s degree programmes (Trình độ thạc sĩ) (ISCED 7) have a theoretical duration of two years. Entrance requirements are a completed bachelor’s degree and a successfully passed entrance exam.

Doctorate degree programmes (Trình độ tiến sĩ) (ISCED 8) have a theoretical duration of three to four years and a completed Master’s degree as an entrance requirement.

Source: Based on (UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS), 2018[6]).

The Higher Education Reform Agenda, a long-term government programme to increase the autonomy and responsibility of tertiary education institutions, was approved by government in 2005, and is expected to lead to comprehensive reforms of the tertiary education system by 2020 (Harman, Hayden and Nghi, 2010[7]). As part of this reform, line-ministry control over public tertiary education institutions is being replaced by a governance system in which institutions will have legal autonomy and greater responsibility for their training programmes, research agendas, human resource management practices and budget plans. The reforms also include efforts, introduced in 2016, towards the creation of a tertiary national education system and quality framework.

Student demand for university degree programmes at higher levels and abroad is increasing strongly

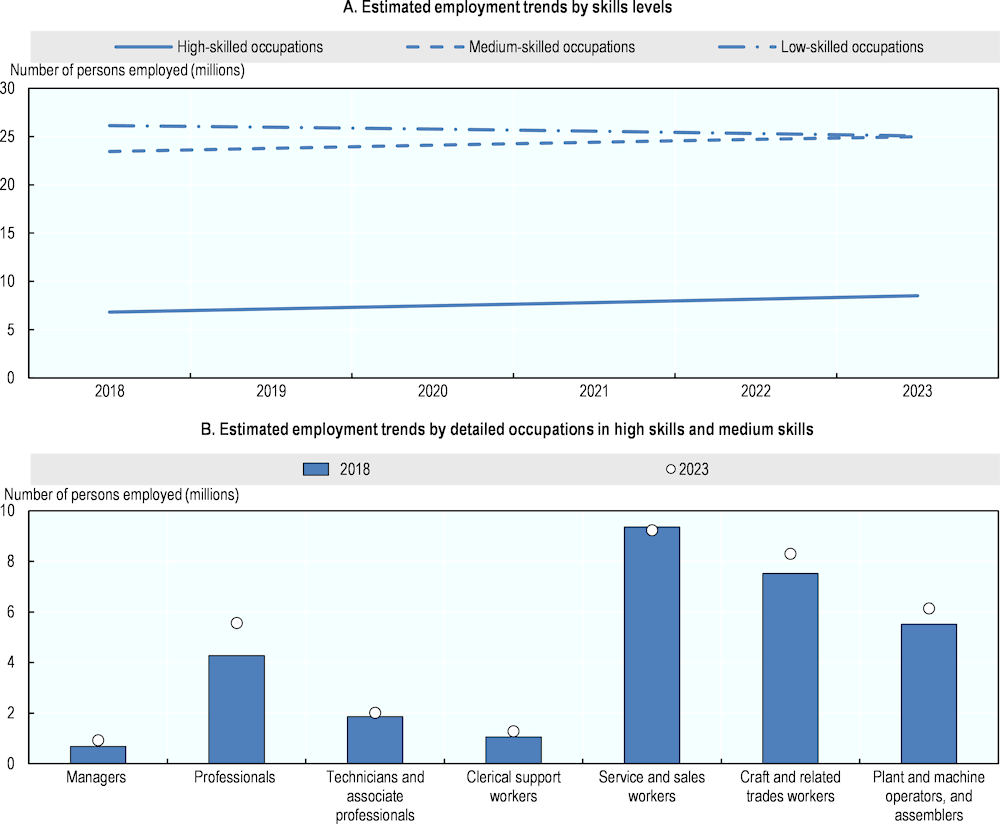

From 1990 to 2016, Viet Nam’s gross enrolment ratio in tertiary education grew tenfold from 2.7% to 28.3%. However, the ratio remains below that of other countries in the region, notably Thailand (49.3%), China (49.1%), Malaysia (41.9%) and Indonesia (36.3%) (Figure 6.3, Panel A).

Student demand for university degree programmes at ISCED levels 6 to 8 is increasing strongly (Figure 6.3, Panel B). From 2013 to 2017, the number of graduates from Bachelor’s programmes (ISCED 6) rose by almost 50% from 205 572 to 306 179. For Master’s degrees or equivalent programmes (ISCED 7) the increase was almost two-fold from 17 361 to 34 684 graduates, and more than three-fold for Doctoral degree programmes (ISCED 8), from 398 to 1 234 graduates.

Figure 6.3. Long-term trends in gross tertiary level enrolment and recent trends in the number of graduates from ISCED 5-8 programmes in Viet Nam

Note: Panel A: The latest data available for Thailand and Viet Nam are from 2016. The gross enrolment rate in tertiary education is defined as the total number of students enrolled, regardless of their age, as a percentage of the population in the age group associated with tertiary education. Panel B: Data for 2017 are missing for ISCED 5 graduates. ISCED 5 refers to short-cycle tertiary degree programmes, ISCED 6 to Bachelor’s degree programmes, ISCED 7 to Master’s degree or equivalent programmes and ISCED 8 to Doctoral degree or equivalent programmes.

Source: Panel A: UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) database, Indicator: Gross enrolment ratio, tertiary, both sexes (%), http://data.uis.unesco.org, accessed 16 September 2019. Panel B: UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) database, Indicator: Graduates from ISCED 5, 6, 7 and 8 programmes in tertiary education, both sexes (number), http://data.uis.unesco.org, accessed 16 September 2019.

In contrast, the number of graduates from short-cycle tertiary education programmes (ISCED 5) decreased by 17% from 182 737 in 2013 to 150 851 in 2017, accounting for 19% of enrolled students. ISCED 5 programmes were popular until 2011, when the share of students enrolled in ISCED 5 programmes was 38.5%. Since then, enrolment has experienced a steep decline. In the wider region, Thailand and Indonesia also have low shares of enrolment in ISCED 5 programmes, at 14.3% and 13.5%, respectively, in 2016, compared to higher shares in China (42.5%), Malaysia (35%) and Korea (22.5%) (UNESCO UIS, 2017[8]).

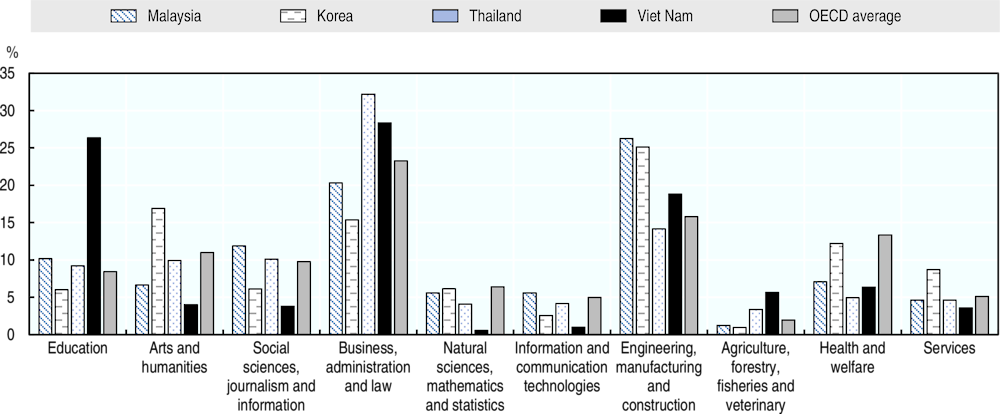

In Viet Nam some tertiary fields of study at ISCED 5 to ISCED 8 have enrolment rates above the OECD average and higher than in other countries in the region, while other fields of study are less popular (Figure 6.4). In 2016, business administration and law was the field with the highest share of enrolment at 28.4%, close to the OECD average of 23.3%, while the country with the highest share of enrolment in this field of study in the region was Malaysia (32.2%). Enrolment in tertiary education programmes stood at 26.4% in Viet Nam, three times above the OECD average and substantively higher than in other countries in the region. Enrolment in engineering, manufacturing and construction stood at 18.8%, slightly above the OECD average (15.8%), and above Thailand (14.2%), but well below Malaysia (26.3%) and Korea (25.1%). Student enrolment in tertiary programmes in the natural sciences, mathematics and statistics, and information and communication technologies, is very low in Viet Nam, at 0.6% and 1.0%, respectively, and between five to ten times lower than the OECD average and enrolment in the region.

Figure 6.4. Distribution of enrolment in tertiary education programmes (ISCED 5-8) by field of study (2016, or latest data)

Note: The OECD average was calculated with 2017 data, and excludes Australia and the United States for which no data were available. ISCED 5 refers to short-cycle tertiary degree programmes, ISCED 6 to Bachelor’s degree programmes, ISCED 7 to Master’s degree or equivalent programmes and ISCED 8 to Doctoral degree or equivalent programmes.

Source: UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) database, Indicator: Percentage of students in tertiary education enrolled by field of study, both sexes (%), http://data.uis.unesco.org, accessed 16 September 2019. OECD Stat, Indicator: Enrolment by field in 2017.

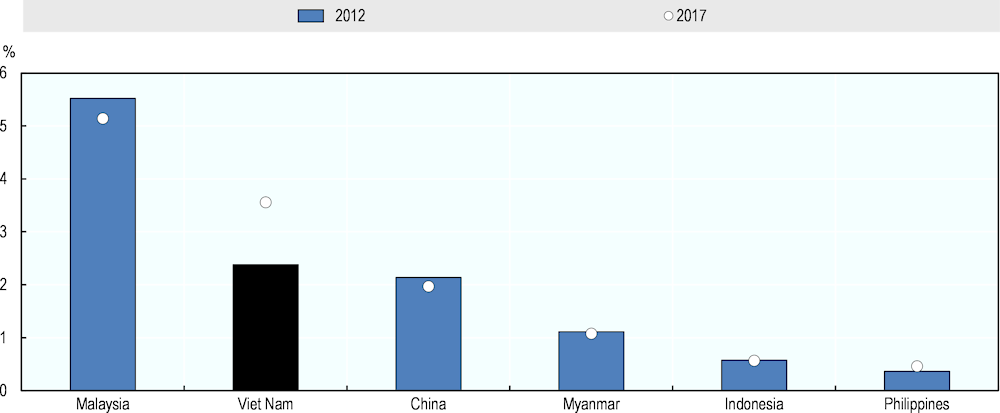

Part of rising aspirations for a university degree is met by increasing outward migration. Viet Nam has the second highest outbound mobility rate in the region, after Malaysia, and the largest increase over time. In 2017, 3.6% of total tertiary education enrolment in Viet Nam took place abroad, 1.5 times higher than in 2012 (Figure 6.5). The United States, China and Australia are preferred destinations (Hoang, Tran and Pham, 2018[9]). Japan also attracts a high number of students from Viet Nam (Ota, 2019[10]). In 2018, 20% of the international students enrolled in higher education institutions in Japan were from Viet Nam.

Figure 6.5. Outbound mobility ratio for Viet Nam and other countries (2012 and 2017)

Note: The outbound mobility ratio is the number of students from a given country studying abroad, expressed as a percentage of total tertiary enrolment in that country.

Source: UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) database, Indicator: Outbound mobility ratio, all regions, both sexes (%), http://data.uis.unesco.org, accessed 16 September 2019.

The tertiary education system is growing with pathways across vocational and into university degrees

Increasing demand for university degrees has also been met by a greater number of university establishments. Between 2010 and 2017, 47 new higher education establishments opened of which 15 were non-public. The non-public university sector accounted for 65 out of 235 of the nation’s universities in 2017 (28%) (GSO, 2017[11]). Several large industry conglomerates have also opened universities and vocational colleges.

Part of this expanded provision is being made possible by the entry of off-shore providers from various countries. By 2015, a total of 282 joint and twinning programmes were being offered in 82 universities in Viet Nam. The majority of these programmes were offered at ISCED 6 level (122 programmes) or ISCED 7-8 levels (115 programmes), with 45 programmes offered as either associate degree or certificate programmes. Partner institutions came from Europe (47%), Asia (26%), North America (15%) and Australia and New Zealand (12%) (Hoang, Tran and Pham, 2018[9]).

Mergers and the integration of institutions across the three levels of vocational education have provided a stronger basis for students to progress across study levels. Students are able increasingly to progress from ISCED 4 programmes to higher education, complete a short-cycle tertiary programme, or continue onwards to a Bachelor’s university degree programme, including in well-designed higher education systems in Europe.

This trend has the potential to improve the low standing of vocational education and training, and raise its attractiveness for prospective students and their parents by ensuring that professional college degrees can be an intermediate rather than final qualification. Public authorities are aware of the weak standing of vocationally oriented higher education, and have undertaken action aimed at raising its attractiveness. Efforts include public information initiatives, such as regularly organised media campaigns, Open Days, Girls Days, participation in global competitions, and initiatives to engage parents and build the reputation of vocational and professional education.

Participation in lifelong learning has expanded

The growth of tertiary education has been accompanied by expanded participation in lifelong learning, with a rise in the percentage of the active workforce enrolled in programmes. Upskilling programmes have reduced the share of workers below basic education levels from 85.2% in 2009 to an estimated 78.6% in 2017 (GSO, 2018[12]). Skills levels grew mainly at the higher end: the share of university degree holders increased almost by twofold from 5.5% to 9.3% and the share of professional college graduates from 1.5% to 2.7%. A common phenomenon is that workers with an ISCED 5 degree continue studying while working to obtain a high-level degree. This phenomenon is fuelled, in part, by employees seeking management positions, for whom degrees from ISCED 6 or 7-level programmes, even if awarded through irregular means, provide opportunities for advancement.

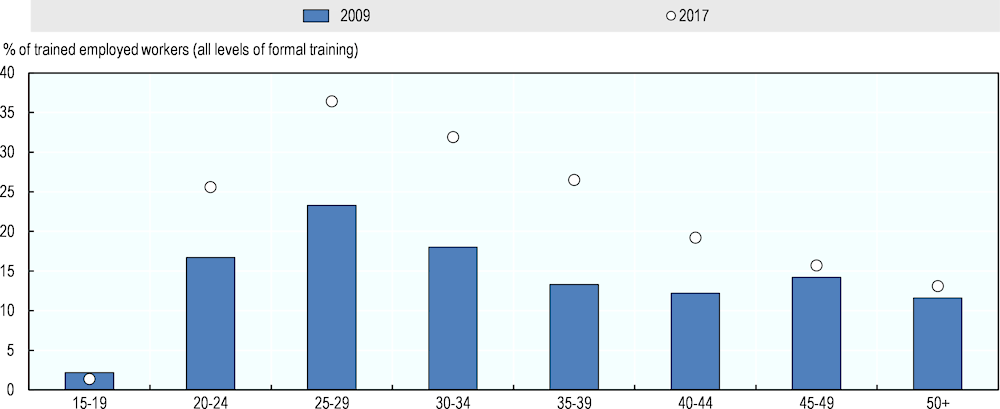

Government efforts to enhance continuous education and lifelong learning have resulted in increased educational attainment levels among workers, particularly in the 25-29, 30-34 and 35-39 age groups (Figure 6.6).

Figure 6.6. Change of educational attainment of workers in Viet Nam by age group (2009 and 2017)

Note: Data for 2017 are reported as preliminary data.

Source: General Statistics Office of Viet Nam, Indicator: Percentage of trained employed workers at 15 years of age and above by age group and year, internal reference code: E02.43, accessed 21 June 2019.

Enrolment in short-term vocational education and training is likely to have contributed to this development. From 2012 to 2016, approximately 8.2 million people enrolled in elementary training in programmes lasting under three months. This figure was 12 times higher than for enrolment in intermediate-level programmes (ISCED 4), while in 2016, college degrees accounted for only 4% of total enrolment (ISCED 5) (NIVET, 2017[13]).

The geographical proximity of educational options appears to increase the take-up of lifelong learning. Enrolment in college-level vocational education and training in the Red River Delta, with its larger density of institutions offering ISCED 5 programmes, was more than twice as high as other regions, reaching 10% (NIVET, 2017[13]). Several universities also offer college vocational degrees as well as shorter general and specific industry-tailored training courses. These have provided an additional source of institutional financing and kept faculty fully employed. The government also counts on distance education to upskill workers. Demand for distance education is increasing: 19 universities and two open universities offer distance learning programmes and certificates, and efforts are underway to ensure quality education.

Examples exist of innovative teaching methods in tertiary education

Education planners have made use of relationships with donor organisations and universities abroad to introduce innovative teaching methods and to strengthen the involvement of employers in the design and delivery of courses and programmes.

A commendable initiative in the field of vocational education and training is the development of cross-occupational green skills in vocational colleges – an important domain of transferable skills and grounding in occupational-specific technical skills. Green skills are important for the future development of Viet Nam’s economy (see Chapter 5). Several colleges offer green skills modules, with support from the German Corporation for International Cooperation (GIZ) and other donors, and in partnership with employers. These modules also provide a good basis for promoting the use of project and problem-based learning.

In the university sector, the Advanced Programmes initiative was introduced in 2006 with the aim of boosting the quality of education by partnering with the top-200 universities from around the world. The initiative follows the curriculum structure and pedagogical practices of the international partner universities, as well as national guidance on content, learning outcomes and compulsory subjects for domestic students (Nghia, Giang and Quyen, 2019[14]). In 2016, the Ministry of Education and Training (MOET) reported the existence of 37 Advanced Programmes of which 30 partnered with tertiary institutions in the United States, one with a partner institution in Belgium, two with partners in the United Kingdom, and two each with partner institutions in Australia and the Russian Federation. Approximately 13 000 students were enrolled in these programmes offered at 22 universities in Viet Nam (Nghia, Giang and Quyen, 2019[14]). Achievements included staff training, the use of innovative pedagogies, and the upgrading of facilities and infrastructure in participating universities.

Educational attainment is rewarded, and university graduates do not crowd out vocational college graduates in the labour market

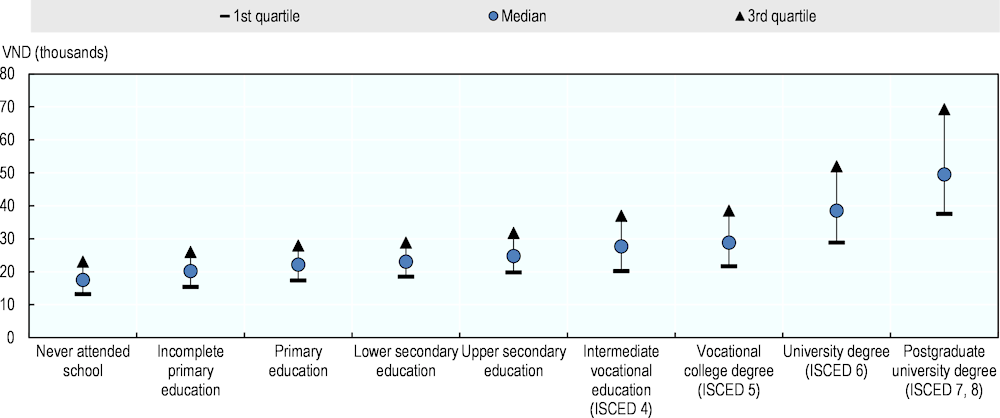

Earnings increase with educational attainment, especially for university graduates (Figure 6.7). Median earnings in Viet Nam rise as educational attainment increases, following an exponential form. Gains in monthly median earnings rise modestly among those who have completed primary and secondary schooling, and rise most rapidly at relatively high levels of attainment. Completion of studies at a professional college is associated with a 16% increase in median earnings (VND 29 000) compared with upper secondary education (VND 25 000), with workers who complete university earning 31% more (VND 38 000) than those who completed professional college, and more than twice (111%) that of workers who never attended school (VND 18 000).

Figure 6.7. Median hourly earnings of wage workers (15-64 year-olds) by educational attainment (2017)

Note: Median hourly earnings of wage workers in Vietnamese Dong (VND) are displayed in thousands, and include overtime remuneration, bonuses, occupational allowances and other welfare payments.

Source: OECD analysis of the Viet Nam Labour Force Survey 2018.

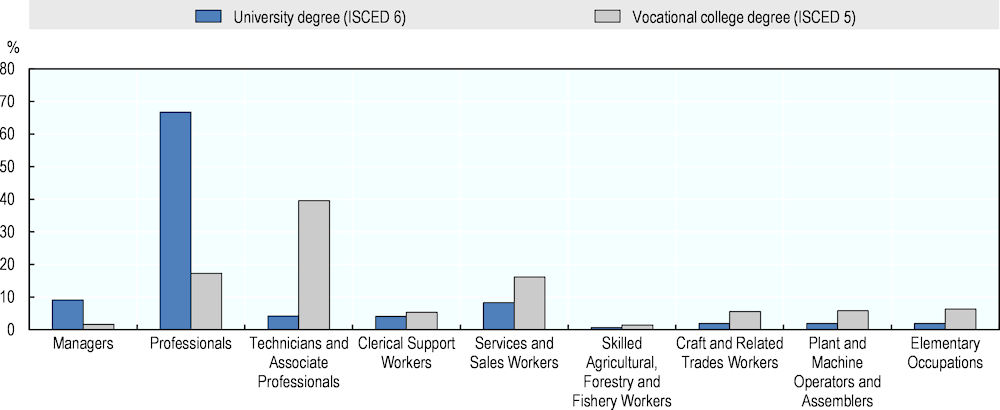

Employment rates for vocational college graduates and university graduates are similar (88.4% vs. 89.4%) (GSO, 2018[4]). The distribution of employed tertiary education graduates by occupation shows few signs of a crowding or substitution effect, whereby university graduates take jobs which require only short-cycle (or lower) qualifications (Figure 6.8). The majority of university graduates were employed as professionals (66.8%), while the plurality of vocational college graduates work as technicians and associate professionals (39.6%). University graduates very rarely work in low-skilled occupations (1.9%), while 6.3% of vocational college graduates work in these jobs (GSO, 2018[4]).

Figure 6.8. Distribution of employed tertiary graduates (15-64 year-olds) by occupation (2017)

Note: ISCO-08 classification, detailed occupations. High-skilled occupations include Managers, Professionals and Technicians and Associate Professionals. Medium-skilled occupations include Clerks, Service and Sales Workers, Skilled Agricultural and Fishery Workers, Craft and Related Trade Workers, and Plant and Machine Operators and Assemblers.

Source: OECD analysis of the Viet Nam Labour Force Survey 2018.

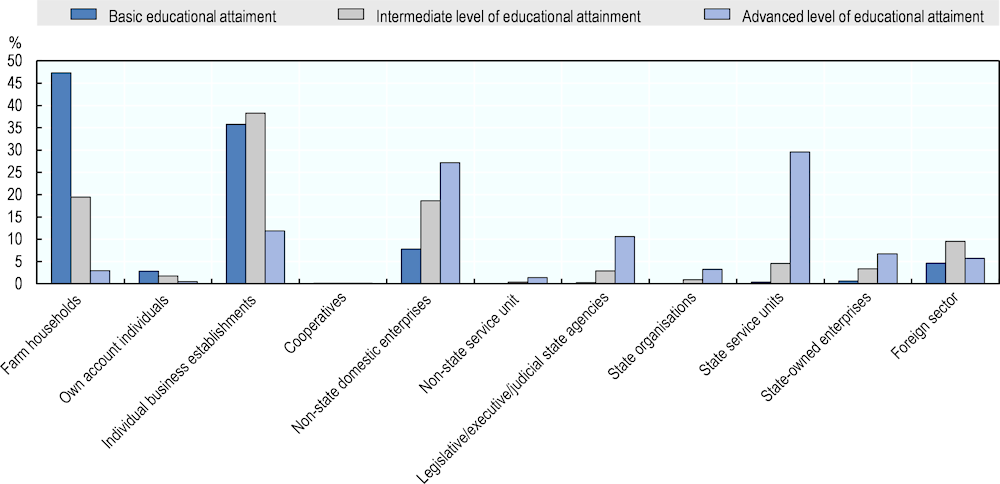

The state sector is the largest employer of tertiary educated workers

For tertiary education graduates the state sector is the largest employer (Figure 6.9). In 2018, more than half of tertiary degree holders worked for the state (50.1%), with the greatest share working in state service units (29.6%). Only 5.7% worked in foreign companies, reflecting the prevalence of low-skilled and low complexity jobs in this sector. Other main employers of tertiary educated workers are non-state domestic enterprises (27.9%) and household businesses (11.9%) (GSO, 2018[4]).

Figure 6.9. Distribution of employment by type of employer and educational attainment, 15-64 year‑olds (2018)

Note: Basic educational attainment includes primary education and lower secondary education. Intermediate level of educational attainment includes upper secondary education and post-secondary non-tertiary education. Advanced level of educational attainment includes tertiary education ISCED 5-8 levels.

Source: OECD analysis of the Viet Nam Labour Force Survey 2018.

In comparison, key employers of the adult workforce in Viet Nam are farm households (35.8%) and individual business establishments (33.2%), also referred to as household businesses (Thai et al., 2017[15]). Non-state domestic enterprises employ 12.6% of the adult workforce, the state sector employs 9.9% – of which 5.1% work in service units, 2.2% work in legislative, executive or judicial agencies, 2% in state-owned enterprises and 0.7% in state organisations. Foreign companies employ only 5.8% of the adult workforce – a tiny fraction of total employment that has barely increased since 2007. Formal self-employment is low: 2.3% of the employer work force are own account workers, and the remaining 0.5% of the adult workforce is employed in co-operatives and other organisations (GSO, 2018[4]).

Start-ups are quickly gaining ground in Viet Nam. Companies such as Edu2Review.com, a platform connecting learners with language schools and training providers across the country, and Robot3T, which provides industrial robot system solutions for small and medium-sized enterprises, are examples of knowledge and skill-intensive start-ups that have emerged in the proximity of tertiary education. A recent survey by Navigos reported that 64% of surveyed 31-35 year-olds were considering starting a business (Navigos Search, 2017[16]).

Key challenges

Although Viet Nam has a co-ordinated tertiary education system with formal pathways and an extended offer, a number of challenges remain. Addressing these is going to require rethinking and redesigning tertiary education rather than incremental expansion of the current arrangements.

Institutional collaboration among tertiary institutions is weakly developed

The dominant policy approach has been to strengthen single institutions and achieve excellence by channelling resources to the best-performing institutions. This has created gaps in coverage in some parts of the country, some duplication in the offer of programmes, and overall a deficit of effective collaboration between tertiary education institutions. Examples of this deficit can be found in the organisation of cross-binary collaboration in education, in the Advanced Programmes initiatives and in the internationalisation efforts of universities.

Several universities offer college vocational degrees as well as shorter general and specific industry-tailored training courses. These have provided an additional source of institutional financing and kept faculty fully employed. However, discussions are underway to limit this practice due to criticism that they withdraw resources from research, as academic staff teach more, and undermine the reputation and capacity of vocational colleges.

Expert commentators agree that the impact of the Advanced Programmes initiative on curriculum reform has been fragmented and narrow, involving only a few major universities and selected disciplines. Furthermore, the initiative has not adopted a co-ordinated institution-wide approach and has thus had only limited institution-wide effects (Tran, Phan and Marginson, 2018[17]).

Relations with the global higher education market place have not produced positive system-level spillover effects. Public officials have required international higher education providers to establish a long-term presence and to invest in facilities, with the hope that market decisions by learners and their families will lead to good outcomes. However, the outcomes of international collaborations appear to work differently in some study areas, with interviewed stakeholders pointing out examples of success in particular in fields related to science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM).

Tertiary education providers are being asked to take increasing responsibility for their educational mission and their “business” mission, but lack the necessary top-down and peer-to-peer support

Although no standardised assessment of learning outcomes exists among tertiary graduates in Viet Nam, common criticisms are that the rapid increase in student numbers, lowered enrolment standards and decreasing resources for the provision of teaching have undermined quality and relevance (Pham, 2012[18]).

As part of the autonomy initiative, universities and vocational colleges have been given the task of gathering and analysing data and information about the existing and emerging needs of their surrounding economy. While this could be a way to strengthen relevance and quality, efforts are currently hindered by institutional capacity gaps, lack of co-ordination of the initiatives of individual education providers and the absence of a common methodology. Expert commenters pointed out that government and tertiary institutions have neither experience with institutional autonomy nor an understanding of the prerequisites and implications (Harman, Hayden and Nghi, 2010[7]).

Designing and delivering educational programmes that are relevant to current and future labour market needs requires organisational capacity to reach out to and involve employers, and to manage and allocate resources efficiently, as well as experience in curriculum design. Increasing autonomy and measures to ensure greater accountability have stretched the management capacity of these institutions and made evident the need for capacity building and greater inter-ministerial collaboration (UNESCO-UNEVOC, 2018[19]).

A key barrier to effective top-down support is the limited availability of up-to-date, representative and system-wide data and information on tertiary education and the labour market outcomes of graduates. Several ministries and agencies collect this information, but there is no co-ordination between organisations, which reduces greatly the comparability, effectiveness and accessibility of the data for tertiary educational institutions and others tasked with the planning of tertiary education.

Vocational education suffers from a low profile as well as issues of quality and relevance

In Viet Nam, parents play a fundamental role in the educational choices of their children. As in many other countries, vocational education and training is less highly regarded among parents than general education and university study (OECD, 2017[20]). While university numbers rose between 2013 and 2017, the number of graduates from short-cycle tertiary education programmes offered by vocational colleges (ISCED 5) decreased, reflecting continued difficulties with creating an attractive offer. At present, usable and trusted information about pathways and outcomes is lacking. Providing timely, accurate and easily accessible information to students and their families about existing modular educational pathways, and the employment and earning outcomes associated with the different exit and re-entry points, will be crucial.

Quality assurance policies, if not properly designed, can risk creating rigid and out-of-date study programmes (ADB, 2014[21]). The vocational college sector is diverse: approximately one-third of vocational colleges are private, some of which are owned by enterprises. Programmes in private vocational colleges must follow the same curriculum as in public vocational colleges. Provisions for follow-up quality control after initial control through the development of a common curriculum is a common approach to ensure quality in higher education systems where there is limited confidence in the capacity of educational institutions, but this can come at high cost (e.g. limiting diversification, and updating and adaptation of the curriculum in response to changing technologies).

Some vocational education pathways are over-long relative to the needs of working life. A recent assessment of vocational education and training in Viet Nam argued that training for some occupations is too long and that vertical progression could lead to up to six years of vocational training prior to employment. Instead, a modular competency-based approach with clear exit and entrance points would make the current vocational education and training system more effective and efficient (ADB, 2014[21]). Professional certificates are not part of the National Qualifications Framework.

The National Council for Education and Resource Development in Viet Nam is chaired by the Prime Minister and includes high-level representatives of several ministries. However, industry participation in this body is limited and does not properly reflect the need for collaboration and exchange with industry on questions of quality and relevance of education and skills development.

Organising work-based learning is difficult

Recent graduates in Viet Nam face challenges in the transition from tertiary education to work. Although employment rates increase with higher levels of educational attainment, tertiary education graduates experience a somewhat higher unemployment rate (3.2% for vocational college graduates and 2.7% for university graduates) than less educated parts of the workforce (2% for upper secondary graduates and 0.9% for workers who attended primary school). However, this lasts for a relatively brief duration. As a comparison of age cohorts shows, in 2017, 16% of 19-22 year-olds were unemployed, a rate that dropped to 5.3% among 23-26 year-olds and 1.4% among 27-30 year-olds.

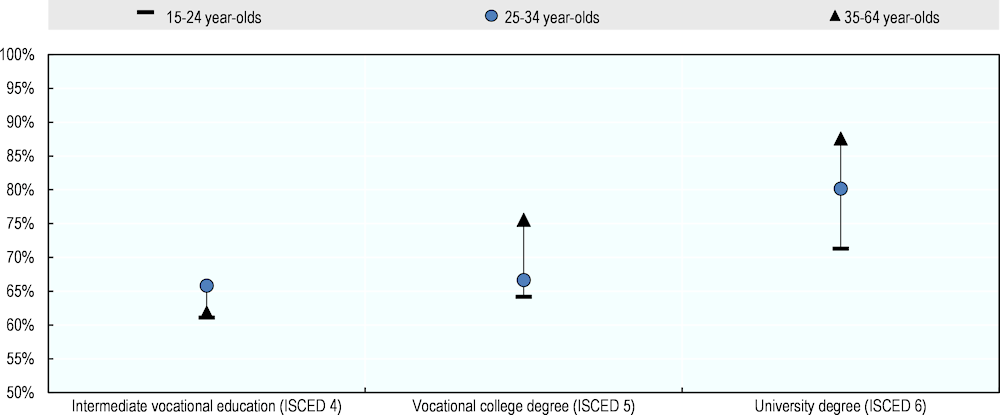

Underlying this phenomenon is the broader issue of relevance of tertiary education. Substantial numbers of people report that the training they have acquired is not relevant to the work they perform (Figure 6.10). Postsecondary non-tertiary training was rated as the least relevant for work with little variation between the different age groups. Short-cycle tertiary degree programmes were viewed as equally matched to job demands by younger age cohorts, while university degrees (ISCED 6) were viewed as providing the highest level of preparedness.

Figure 6.10. Perception of mismatch between training and work in Viet Nam (2018)

Note: Respondents who stated “No training/Không được đào tạo” were excluded from the analysis.

Source: OECD analysis of the Viet Nam Labour Force Survey 2018.

There are no recent, large-scale surveys in Viet Nam to assess the match between demand and supply of skills. The most comprehensive analysis was undertaken by the World Bank in 2011 and 2012. The Skills Measurement Project (STEP) surveyed employers in the urban labour markets of Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, including surrounding provinces, and found that employers rated technical and generic skills such as problem solving, communication, the ability to work independently as well as in teams, and time management, as highly important. At the same time, 80% of surveyed employers who hired professionals and technicians in high-skilled occupations, reported that applicants lacked both technical and generic skills (Bodewig et al., 2014[22]).

There is insufficient high-quality work-based training in Viet Nam’s tertiary education sector. Although internships are mandatory in vocational college programmes, weak links between companies and colleges often limit the quality and quantity of internships (OECD, 2017[20]). In university programmes, work-based learning is rare. Stakeholders interviewed by the OECD Review Team reported that organising work-based learning on a large scale is difficult given the structure of Viet Nam’s economy, due to the predominance of micro and small enterprises in the household firm sector and informal employment. However, almost one-third of tertiary education graduates work in domestic firms, and another one-third in state enterprises. Both sectors should offer more capacity and touchpoints for collaboration with tertiary education institutions than household businesses, which employ 11.9% of graduates.

Teaching staff are expected to change their approach to teaching and learning, but are not provided with appropriate support. Education planners expect teaching staff in tertiary education to help students develop the technical and generic knowledge and skills that they will need to succeed in their future jobs. There is a general expectation from government, students and employers that the current approaches to teaching and learning need to change in order for students to develop critical thinking, communication skills, and problem solving and decision-making skills, as well as range of social and emotional skills. In light of this, MOET has recently introduced test questions into national examinations that require students to demonstrate proficiency in critical and creative thinking (Tran and Marginson, 2018[23]).

While expectations have been established, teaching staff are not supported in the adoption and practice of more active learning methods that emphasise the teacher’s position as a facilitator whose role it is to guide students in taking ownership of the learning process. With some exceptions, teaching staff generally have very little involvement in the design of the courses they teach. As a recent commenter pointed out, “It is a big ask of academics, who themselves are products of this approach, to design a curriculum and include activities that provide opportunities for young learners to work in teams to provide creative solutions to real-world problems” (Temmerman, 2019[24]).

There are no large-scale government programmes to support training of academic staff in the use of innovative teaching methods. While there are single initiatives in universities and vocational colleges, often established in collaboration with international donor organisations or enterprises, the lack of inter-institutional networks precludes exchange of information and peer learning at system level. Pilot initiatives therefore remain isolated and unevaluated. There are no teacher awards, although, according to stakeholders interviewed by the review team, private companies might be willing to sponsor such schemes.

Students lack information about education options and labour market outcomes

Parents in Viet Nam play a fundamental role in directing their children’s choice of field of study. In 2016, the four fields of university study with the largest number of graduates were business administration and law (29.2%), education (25.7%), science, technology, engineering and mathematics (22.7%), and engineering, manufacturing and construction (19.9%) (Figure 6.11, Panel A.). The following fields of study saw an increase between 2012 and 2016: education (from 22.6% to 25.7%), health and welfare (from 3.9% to 6%), social sciences, journalism and information (from 2.6% to 3.8%), and information and communication technologies (from 1.3% to 2.1%). The largest decrease, by 4.1 percentage points, occurred for programmes in the engineering, manufacturing and construction category.

University students appear to be weakly influenced by prospective employment outcomes when choosing their field of study. For example, information and communication technologies, which ranks last in the number of programme graduates, is first in graduate employment (92.9%), and second in earnings (VND 40 400 hourly wage). According to estimates by the Navigos Group, a large recruitment company in Viet Nam, positions in mid-management level and above increased by 14% in the ICT industry in 2017 compared to the previous year (Search, 2018[25]). The field of study with the largest number of graduates is business administration and law. It ranked 8th in employment rate (89.9%), and 5th in earnings (VND 37 500).

Figure 6.11. Distribution of university graduates in Viet Nam by fields of study (2012 and 2016) and employment outcomes of tertiary educated workers (15-64 year-olds) (2017)

Note: Panel A: Data for Information and Communication Technologies, and Natural Sciences, Mathematics and Statistics is reported for 2013. The sum of listed fields of studies exceeds 100%. Panel C: Median hourly earnings include overtime remuneration, bonuses, occupational allowances and other welfare payments, in Vietnamese Dong (VND, in thousands). Panel B and Panel C: A manual categorisation of field of study was conducted.

Source: Panel A: UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) database, Indicator: Percentage of graduates from tertiary education graduating by field of study, both sexes (%), http://data.uis.unesco.org, accessed 16 September 2019. Panels B and C: OECD analysis of the Viet Nam Labour Force Survey 2018.

Viet Nam’s tertiary education planners assume that learners will make informed choices, ultimately selecting the most beneficial study options when asked to make a decision about continuing into tertiary education, including the type of degree programme and field of study. According to the interviewed MOET representatives, students and their parents can consult the socio-economic strategy to inform themselves about sectors of the economy predicted to develop and current government priorities. They can also consult the website of the government statistical office for key socio-economic indicators, which are updated on a monthly/bi-monthly and annual basis. However, international experience indicates that students and parents often do not search for this information or fully understand how to use it.

Representatives of universities also visit secondary schools in provincial capitals to provide information about their educational offer to students. However, their reach is limited to a small percentage of students and parents, and the information is likely to be biased in favour of the institution and programmes presented. Career guidance is limited and not offered to all students when they first need it – at the end of primary education.

As a result, many learners and their parents lack information about the labour market relevance of tertiary programmes and the employment outcomes they can expect upon graduation. As the default option for many parents is a university degree in law or business administration, many prospective students will follow this guidance even if a vocational college degree or a technical programme might be a better match for their interests and aptitudes.

Low concentration of researchers in the private sector and the absence of a strategic vision for research are key barriers to research and innovation

In the past, scientific research in Viet Nam was performed largely outside of universities in an academy of sciences, as in many systems influenced by the Soviet model. In the mid-1990s, research was added to the core functions of universities, but attention to research remained low until the research support framework and research performance were incorporated into institutional accreditation standards (Pham, 2012[18]).

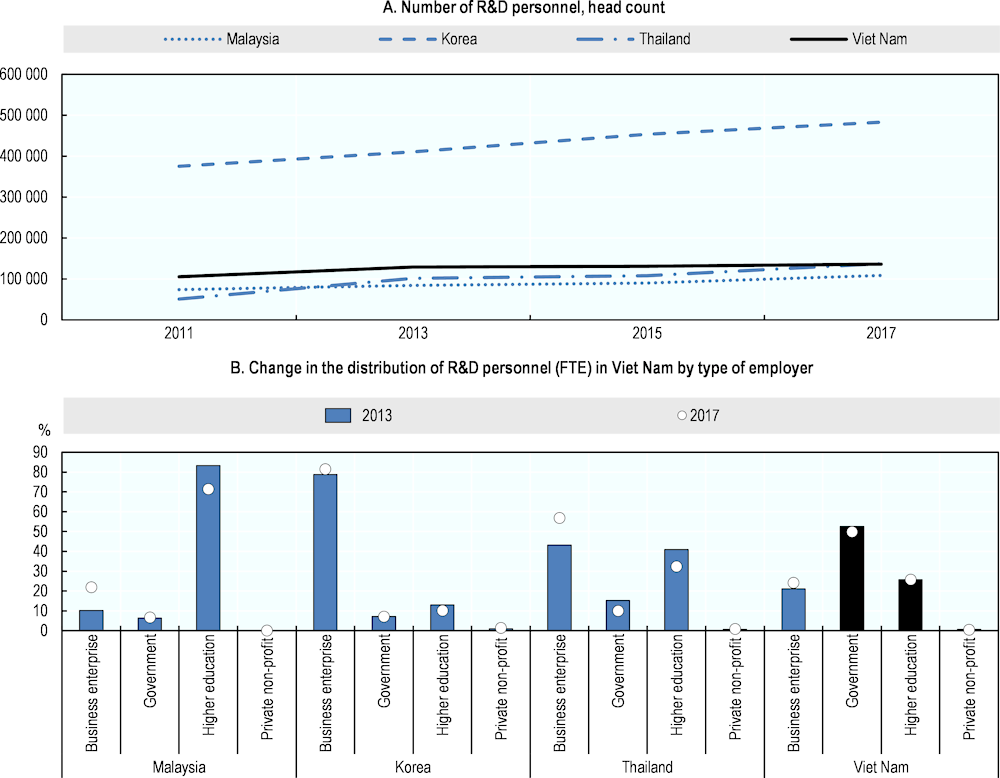

Between 2011 and 2017, the number of workers contributing to intramural research and development (R&D) activities in Viet Nam slowing increased (Figure 6.12, Panel A). The state is a major employer of researchers in Viet Nam – in 2017, it employed every second researcher (52.5%), a share up to five times higher than other countries in the region (Figure 6.12, Panel B). Most are employed in public research organisations. In 2006, more than 500 public research organisations existed in ministries, academies and other public bodies and organisations. MOET hosted the highest number of research organisations (155), followed by the Viet Nam Academy of Science and Technology (44) (OECD/The World Bank, 2014[26]).

In 2017, 25.8% of researchers worked in higher education institutions, a share that has remained stable in recent years. However, universities in Viet Nam have experienced great difficulties in selecting, retaining and developing researchers, due to the low remuneration, heavy teaching load and migration of talent (Nguyen, 2013[27]). Business enterprises in Viet Nam slightly increased the number of researchers they employ, but the overall share of 24.1% (2017) is much lower than in the other countries.

Figure 6.12. Recent trends and employment of researchers by sector in Viet Nam and selected countries (2011-17)

Note: Panel A: Headcount (HC) of R&D personnel: the HC of R&D personnel is defined as the total number of individuals contributing to intramural R&D, at the level of a statistical unit or at an aggregate level, during a specific reference period (usually a calendar year). For Malaysia and Thailand, the data points reported for 2013 are 2014 data, and the 2017 data points are 2016 data. Panel B: For Malaysia and Thailand, the data points reported for 2013 are 2014 data, and the 2017 data points are 2016 data.

Source: UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) database, Indicator: Employment of researchers, full-time equivalent, by sector, both sexes (%), http://data.uis.unesco.org, accessed 16 September 2019.

Viet Nam does not have a broadly shared and understood strategic vision for university research. This is reflected in ignorance among stakeholders about the research priorities of the system, the lack of support for domestic PhD students, and the very low degree of collaboration between public research organisations and research groups in universities. The government supports doctoral training abroad with a fund that awards 10 000 scholarships (Hoang, Tran and Pham, 2018[9]). This constitutes a very large investment in a currently small group of doctoral degree students (1 234 in 2017). According to the government stakeholders interviewed by the review team, approximately one-half of doctoral degree holders trained abroad will return to Viet Nam after their studies. Some will find it difficult to integrate into the Vietnamese research environment after their experiences abroad, particularly if there are no doctoral and post-doctoral students to build up research teams.

More than a decade ago, the Minister of Education and Training (currently the Party Secretary for Ho Chi Minh City) pushed for the idea to introduce funding in the amount of VNM 100 million (about USD 5 000) for each domestic doctoral student. This idea was not implemented. For many years, the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) has had unallocated research funding at the end of the fiscal year, reportedly amounting to a few million USD. However, due to the lack of a mechanism for horizontal co-ordination and collaboration, an allocation to support domestic doctoral students was not possible.

As interviews with stakeholders confirmed, a persistent challenge for the past six years has been the development of effective relationships between university research and public research organisations, which traditionally have received most of the research funding (Nguyen, 2013[27]). Researchers count on research funding to supplement their low salaries. Principal investigators at public research organisations can face pressure from their colleagues to give opportunities to these colleagues to participate in research projects and earn extra income. This creates a barrier to extra-mural research collaboration. Faculty members at universities solve the problem of low salaries and insufficient research funding by taking on more teaching.

The way forward

Viet Nam aspires to develop a generation of tertiary educated graduates with outstanding technical knowledge and generic skills that permit continuous adaption to new technologies and business conditions. To date, it has aimed to achieve this skill profile in graduates through policies that encourage the importation of a new educational model, and through targeted support for individual tertiary education institutions.

With more than 2 million students in tertiary education, an approach that will reach only thousands of learners is not sufficient. Instead, Viet Nam needs to reflect on how innovative, high-quality and relevant provision can be broadly dispersed across its tertiary education system, at scale. The MDR Viet Nam proposes four priority areas for public policy action:

Enhancing collaboration in tertiary education to strengthen skills development and innovation

Supporting teachers in tertiary education to adopt effective pedagogies to develop the knowledge and skills that student need to succeed in the labour market

Building a strong information system to support evidence-based policy making and guide student choice

Strengthening innovation through knowledge exchange activities between universities and firms with innovation ambitions.

A policy dialogue gathering national and international experts in education contributed to the identification of some obstacles to policy implementation. The dialogue was held in Hanoi in October 2019 and included the participation of representatives of public agencies from the Government of Viet Nam as well as one expert from the Higher Education Authority of Ireland. Key bottlenecks that Viet Nam needs to overcome are the lack of linkages between educational institutions and the private sector, limited innovation created by research centres to the benefit of local businesses, mismatch between the skills offered by Vietnamese workers and the demand of the labour market, and the scarcity of career opportunities and orientation (Box 6.2).

Box 6.2. Results from the workshop “Creating a network of institutions to build up skills and innovation”

Group 1: Establishing linkages between educational institutions and the private sector

Group 1 discussed three main obstacles to implementation. The first is the lack of data on demand for labour and skills. The participants proposed the following solutions to tackle this issue: i) periodic surveys on skills and labour needs, ii) engagement of firms in the design of National Skills Standards and the evaluation of training outcomes, iii) establishment of an e-portal to report on labour demand and skills demand, thereby suggesting how the education system could fill the gap. The incurred cost of education engagement is actually tax-deductible for firms already, but the Ministry of Finance has not provided guidance on implementation.

The second bottleneck is the lack of co-ordination among ministries responsible for human resources and between different levels of governance – national and subnational. Legislation on collaboration and cross-monitoring should, therefore, be introduced.

The third issue is the weak interlinkages between vocational institutions and universities. Those in the TVET system often find it hard to transition to university. Furthermore, moving across institutions is difficult and credits cannot be transferred, creating a high opportunity cost for learners if they desire to switch educational institutions.

Group 2: Creating innovation for the private sector

According to Group 2, the main obstacles to policy implementation are the lack of innovation among firms, and the weak linkages between the domestic and FDI sector and among firms and institutions. The group concluded that facilitating innovation, improving the absorption capacity of firms, supporting technology brokers and developing technology markets need to be the priorities to create innovation in the private sector.

Key performance indicators to track implementation could include the percentage of firms with innovation activities, the value of innovative products, the existence of linkages, the mechanisation and automation rate, and the number of firms participating in GVCs.

Group 3: Curricula and skills for all needs

Group 3 discussed two issues relating to the need to tailor curricula and skills for all needs. The first issue is that schools are putting too much emphasis on teaching content, ideology and politics, instead of essential soft skills for job-oriented needs such as communication skills. Students, therefore, often lack the requisite practical skills and professionalism to thrive in the labour market. The following actions could be taken to remedy this situation: enhance the autonomy of education providers (from basic education to colleges and universities), improve teacher capacity and better monitor education reform programmes.

The second issue concerns the lack of involvement of all stakeholders in shaping educational programmes. The priority is to increase the participation of enterprises and society in designing the curricula of institutions and enhance job orientation. Key performance indictors to track implementation could include the percentage of qualified workers in the private sector, the percentage of graduates with jobs in the field in which they were trained and the percentage of workers retrained. Group 3 also mentioned the need for linkages with other levels of education.

Group 4: Career opportunities and orientation

Group 4 considered the lack of career orientation and information about job opportunities as two priority issues. Going forward, MOET should co-ordinate with education providers and firms to develop job-experimental programmes for students of all levels (i.e. secondary and high-school students). Key performance indictors to track implementation could include the number of programmes being launched, the number of students and enterprises participating in the programmes, measurement of the satisfaction of citizens regarding education providers and the rate of growth of participants in the programmes.

A dedicated body also should be established to develop and operate a central platform providing information on education and job opportunities for students. This body should be responsible for co-ordinating MOLISA, chambers of commerce, MOET and other stakeholders. Key performance indictors could include whether the website system is working, questionnaires to classify different audiences and long-term measurements of the impact of the platform in helping students find jobs. Above all, an effective policy framework is required to implement all these reforms.

Table 6.3 summarises high-level and more detailed recommendations to pursue reforms in these priority areas. It also includes a set of indicators to track the implementation of most of these recommendations.

Enhance collaboration in tertiary education to strengthen skills development and innovation

Enhancing quality in tertiary education has been a longstanding policy priority in Viet Nam (World Bank, 2016[28]). However, policies have not aimed to achieve this through greater institutional collaboration, but rather by strengthening single institutions. This approach might be highly counterproductive: if mechanisms to organise peer learning and to upscale best practices are lacking, successful initiatives risk to remain isolated and education policies would not have wider system-level impacts.

The recent autonomy initiative and common internationalisation practices of institutions illustrate this limitation. Tertiary education institutions have been given greater responsibility with regard to their educational offer and research activities (for universities), and their revenue generation and resource allocation. Some tertiary education institutions have been more successful in mastering these new tasks, while others have been more innovative and resourceful. In the same vein, the outcomes of institutional relations with the global higher education market place vary substantively. In both cases, a lack of mechanisms to share information is preventing replication of good practices and the avoidance of mistakes. Approaches that proved to be successful remain isolated and do not produce positive spillover effects for the tertiary education sector.

Promoting excellence has been the primary aim of tertiary education policy in Viet Nam. Viet Nam universities are now present in international rankings (Vietnam National University Hanoi and Hanoi University of Science and Technology were placed in the 800-1000 group in the Times Higher Education World University Ranking 2020, and Vietnam National University Ho Chi Minh City was placed in the group 1000+). However, these efforts have not resulted in a broad basis of system-wide quality. In some fields, a concentration of resources would, however, be needed to develop higher quality in education and research, and in many fields good teaching is enhanced by sharing information about effective teaching practices. In future, greater emphasis is needed on building capacity across tertiary education through inter-institutional co-operation. This will require structural reform measures, examples of which are described below.

Increased collaboration among tertiary education institutions is an approach commonly practised by public authorities to achieve higher levels of quality in education, research and institutional management (Williams, 2017[29]). Different forms of inter-institutional co-operation exist, and vary in terms of the formality of collaboration modalities and the sharing of resources (Table 6.1). Recent studies have reviewed the different forms of inter-institutional co-operation and various policy approaches implemented in OECD countries (Williams, 2017[29]).

Table 6.1. Different forms of inter-institutional co-operation in tertiary education

|

|

Networks |

Collaborations |

Alliances |

Mergers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Relationship between partners |

Connections between individuals within institutions, or between institutions |

Arrangements between institutions (rather than individuals), embedded in formal agreements or partnerships |

More extensive forms of collaboration that cover a wider range of operations |

At least one institution ceases to exist as a legal entity through incorporation within an existing or new institution |

|

Implications |

Little or no leadership involvement, generally informal communication, and no change to organisational autonomy |

May involve sharing of legal rights and privileges, human resources, physical space, equipment and technology, or information |

Partners share a wide scope of capacities, but retain separate identities and legal statuses, and agreements are revocable |

The original components of the merged entity may retain distinct names, brands, governance and operations to varying degrees |

Source: Adapted from (Williams, 2017[29]).

Efforts to develop collaborations or alliances between tertiary education institutions in Viet Nam should have as their focus strengthening the quality and relevance of education, and raising the level of innovation connectivity in university-performed research, across all tertiary education institutions.

Governments typically stimulate structural reform in tertiary education through regulation, the use of information and communication, positive and negative financial incentives, and the use of organisational levers such as agencies and expert panels. This review proposes that Viet Nam consider a combination of these policy instruments to achieve the following four objectives.

Joint development and delivery of high-quality, widely used courses. Encourage collaboration and alliances within and across the university and vocational college sectors in the joint development and delivery of high-quality, widely used courses. A way to achieve this would be to set aside a share of institutional funding to pay up-front development costs of course consortia, and then reward institutions for enrolments in these courses after they are in place.

Collaboration in research in line with national research priorities. Stimulate inter-institutional collaboration in research in line with national research priorities. Careful consideration should be given to increasing financial support for domestic doctoral students, as this would help develop domestic research capacity. This could be accomplished, for example, by using competitive funding to co-finance joint research projects, organise doctoral degree programmes and to encourage the joint use of research facilities. Match funding could come from companies and/or provincial/city governments.

Peer learning to stimulate the exchange of experience and collaboration for universities and vocational colleges. Organise regular peer learning activities for universities and vocational colleges, both within and across the two sectors, to stimulate the exchange of experience and collaboration in internationalisation, and innovative practices in engagement with enterprises relating to curriculum design and work-based learning education, and strengthen the practice of collaborative research. This could be done, for example, by creating a programme that funds regular peer learning activities and the collection and provision of information about relevant practices. A public council consisting of higher education representatives and external stakeholders could be created to analyse the collected information for national strategy development, for example, to inform a national strategy for the internationalisation of Viet Nam’s tertiary education.

Strategically focused international exchange and learning activities for senior management, and administrative and academic staff. International learning and collaboration should draw upon the experiences of carefully selected high-performing systems that offer developmental models fitted to Viet Nam’s skills strategy – in place of a willingness to export educational services. These international partners should be asked to contribute to peer learning, for example as mentors to support the piloting and mainstreaming of more effective institutional management practices, curriculum development and research management practices.

Ireland offers valuable lessons for Viet Nam on how to build the collective capacity and capability of tertiary education by strengthening the regional dimension (Box 6.3).

Box 6.3. Regional collaborative initiatives in Ireland

Tertiary education in Ireland is offered by public and private tertiary education providers of three types: universities, institutes of technology and specialised colleges. In an attempt to overcome fragmentation, avoid duplication of programmes and provide a better response to skills and innovation needs, the collective capacity and capabilities of tertiary education were strengthened and given a strong regional dimension. The process was guided by the 2011 National Strategy for Higher Education to 2030 and the 2016 National Skills Strategy 2025. A key policy instrument was the development of regional collaborative initiatives in the form of Regional Clusters and Regional Skills Forums.

The six Regional Clusters built on prior collaboration initiatives between tertiary education institutions, with the aim of adequately reflecting the institutional context and the local economy. The Regional Clusters sit under the Regional Skills Forums, which bring together employers and the education and training system in each region to facilitate the planning and delivery of programmes, with a view to reducing duplication and informing national funding decisions.

An oft-cited example of the Regional Clusters initiative is the Shannon Consortium, initiated by the University of Limerick and the Limerick Institute of Technology. Since its inception in 2007, the collaboration has developed into a vibrant partnership, which also involves the local teacher training institution, further education providers, local businesses, city and county councils, and the wider public. The joint bid to the Strategic Innovation Fund, an Irish government initiative, was an important milestone.

The partnership has led to a growing number of innovative joint activities in education and research. Examples include a combined graduate school and PhD accreditation (which commenced in 2015), lifelong learning, applied research activities and new ways to enhance enterprise engagement.

The joint delivery of courses evenly and equitably in the two higher education institutions is regularly reviewed by faculty heads, in order to find solutions to overcome logistical challenges, including the movement of students across the city for courses at different campuses, and the establishment of new classroom technologies to enable distance and online education. This review is deliberately organised at departmental level and not at senior management level in order to reach out to as many staff as possible. Regular two-hour workshops are organised for staff to exchange experiences and to build awareness and skills around key issues, such as facilitating group work, assessment in experiential learning and others.

A commendable initiative bridging education and research is “Limerick for IT”, an ICT skills partnership which commenced in 2014 and brings in industry partners such as General Motors, Johnson & Johnson and the Kerry Group. Key government partners are Limerick City and County Council and IDA Ireland, the agency responsible for the attraction and retention of inward FDI. The initiative attracted FDI and led to new forms of collaboration between tertiary education and industry partners (e.g. the Johnson and Johnson Development Centre at the University of Limerick).

These examples show that the commitment of institutions to collaboration is crucial for success. On top of strategic decisions, which need to be appropriately informed, there is a need to set up teams to work on the development of possible ways of implementing decisions in a range of areas, including skills, research and local development. The organisational capacity of the institutions is crucial for achieving these common objectives, as is strengthening the communication of strategic objectives and decisions within the institutions and towards regional partners. Senior management in both institutions have initiated a large-scale communication process to create commitment for the reallocation of resources through a central office to strategic teams involved in the development of courses or research collaboration. This has successfully raised the level of interaction, introduced a more interdisciplinary framework, and supported the bottom-up emergence of innovative approaches and ideas.

The Irish government supports the regional collaborative initiatives in two ways. Funding helped to defray the costs of starting and organising collaboration and constituted a major incentive for institutions and partners that joined. Equally important was the provision of information. During the creation phase, the commissioning of thematic reviews informed different dimensions of collaboration. An expert advisory panel comprising public policy analysts, academics, relevant practitioners, and representatives of students and relevant employers prepared the thematic reviews. Continuous information support has been provided by the Expert Group on Future Skills Needs (EGFSN), created in 1997, with representatives from several government departments, industry, education and training organisations as well as social partners. The EGFSN provides advice and support on monitoring, planning and implementing a large range of skills-related policies. It also conducts foresight and benchmarking exercises to help public authorities estimate future skill requirements across sectors.

Recently, the information policy lever has been further developed by the Network of Regional Skills and SOLAS, the Further Education and Training Authority in the “Skills for Growth” initiative, which aims to make it easier for employers to identify their skills needs and receive guidance on which education and training providers are best suited to their requirements. The “Skills for Growth” initiative seeks to increase the quality and quantity of data available on skills needs in individual enterprises. The information provided will assist education and training providers to align course content with the needs of the labour market.

The commitment of higher education institutions and the support of the government, particularly the work of the EGFSN, have been crucial factors in mobilising and sustaining the involvement of industry partners.

Source: (OECD/European Union, 2017[30]); more information on www.dbei.gov.ie/en.

An example of international learning and collaboration that offers developmental models fitted to Viet Nam’s skills strategy is the current programme of the German Academic Exchange Service, DAAD, which collaborates with education ministries and higher education institutions in Africa to stimulate excellence in higher education management (Box 6.4).

Box 6.4. DAAD – Supporting excellence in higher education management in Africa

With funding from the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ), the DAAD supports efforts to make African universities more labour market-oriented through, among other measures, the “Entrepreneurial Universities in Africa (EpU)” programme, which was launched in 2018. According to the DAAD, the aim is for higher education institutions to more strongly interlink theory and practice to support their students, for example, through practical training and measures (e.g. career advisory centres) designed to assist them in transitioning to the labour market. In 2018, the DAAD issued calls for proposals for partnerships with Tunisia and Morocco, as part of this programme, and held conferences in both countries where representatives of higher education institutions from each country met with industrial partners from Germany, Morocco and Tunisia. Implementation started in 2019.

Source: (DAAD, 2018[31]).

Help teachers in tertiary education adopt effective pedagogies to develop the knowledge and skills that students need to succeed in the labour market

Concerns about the relevance of tertiary education in Viet Nam have been widely raised by employers, students and graduates, university leadership and academic staff (Manpower, 2011[32]; Bodewig et al., 2014[22]; Nghia, 2018[33]; Tran, 2018[34]). University informants overall agree that the predominance of a theory-based curriculum and the lack of opportunities to apply knowledge to practice through work-based learning and laboratory work are key challenges (Tran, 2018[34]).

In 2010, MOET included the development of generic skills in the educational standards of tertiary education (Ministry of Education and Training, 2010[35]). While this is a good starting point, effective implementation will depend upon the capacities of teaching staff and supportive learning resources for teachers, such as open educational sources and blended learning curricula. The size of classes is often identified as a problem, and leads to the use of lecture-based instruction rather than student-centred learning approaches (Nghia, 2018[33]).

Support measures are needed for teachers to act on top-down directives, as is clarity regarding the responsibilities and duties of teachers in relation to the development and assessment of generic skills. Teaching staff in universities, according to one exploratory study, report that they were largely unable to use innovative assessment methods, such as portfolios, teamwork log sheets or co-assessment with an industry-based mentor (in the case of work-based learning) (Nghia, 2018[33]).

Not all higher education students are aware of the increasing importance of generic skills. Recent research by LinkedIn in Brazil, India, Indonesia and South Africa points to a skills signalling gap. Young people lack information about the skills that employers require, particularly in terms of generic skills. While generic skills represent 25% of the top 20 skills in job postings in the four countries, they do not appear among any of the top 10 skills in the profiles of young LinkedIn users (LinkedIn and S4YE, 2019[36]).

Work-based learning can be a very effective approach to help students develop generic skills. A key barrier in Viet Nam is that most companies lack interest or the resources to collaborate with tertiary education institutions on work-based learning arrangements. High-quality, work-based learning requires that education institutions, including their teaching staff, develop a shared understanding of the purpose of training, and clearly define the complementary roles and responsibilities of students, employers and the education institution (Table 6.2). These developments will require funding that supports training for the academic and administrative staff involved, outreach to firms and training for firms to help them become effective education partners.

Table 6.2. Responsibilities in work-based learning

|

Tertiary education institution |

Student |

Employer |

|---|---|---|

|

• Plan and clearly define responsibilities for all • Standardise duration and structure • Enhance networking and engagement • Dedicate resources • Develop employer and student placement information packages • Design structured alternatives to placement • Organise preparatory and reflective learning activities |

• Participate in preparatory and reflective learning activities • Manage and clarify expectations before placement • Take responsibility for achieving learning outcomes • Engage in reflective learning activities |

• Assist higher education institutions in developing placement contracts/agreements • Enhance networking and collaboration with higher education institutions • Develop job specification • Support workplace learning |

Source: (OECD/European Union, 2017[30]).

One way to raise the interest of companies is to make students work (in teams and under the supervision of academic staff) on developing local case studies exploring different forms of innovation, in line with plans of the Ministry of Industry and Trade (MOIT) to stimulate innovation activity in firms.

Viet Nam’s education planners have recognised the importance of high-quality relevant teaching (World Bank, 2016[28]). This review proposes that Viet Nam consider the establishment of a national Centre for Excellence in Teaching and Learning to provide continuous professional development for academic staff and contribute to the strategic development of teaching and learning across the sector. This should be combined with policy levers that reward individual teachers for high performance and acting as role models for others.

Improve compensation and reward structures for teachers in tertiary education institutions to stimulate the adoption of innovative pedagogies. Salaries of academic staff in public universities are very low and require individuals to take on additional teaching assignments or work in the private sector, often in areas unrelated to their discipline. Adopting a different approach to teaching in the form of innovative pedagogies requires more time and often also substantive preparation, which teaching staff currently lack. Viet Nam could consider introducing a performance-based salary increase for teaching staff who have completed training in innovative pedagogies and/or act as trainers and role models for other teaching staff. A rise in the compensation of teaching staff should not be financed through increased tuition fees, as this would constitute a hardship for learners from low-income households, and deter their enrolment. A national fund for innovation in teaching and learning, collaboration in higher education and collaboration with employers to enhance the relevance of programmes could be established, similar to a national research fund administered by MOST. A national fund for innovation in teaching and learning would go hand-in-hand with a national Centre for Excellence in Teaching and Learning.

Create a national Centre for Excellence in Teaching and Learning to raise teaching quality across the tertiary education system. The programme of work of a national Centre for Excellence in Teaching and Learning should include the provision of continuous professional development, guidance and support for research on innovative pedagogies, the creation and implementation of a national teacher award programme, and the development of common indicators to assess quality of teaching and learning. The underlying goals should be to motivate academic staff towards high-quality teaching, encourage innovation in teaching and learning activities, and improve institutional recognition and awareness about teaching and learning enhancement, while taking into account the different types of teachers, including part-time and recent graduates, and the variety of teaching styles. Particular attention should be paid to the situations of female faculty members and researchers with small children, for whom spending considerable time away from home would present more of a challenge. To facilitate participation, sizeable regional offices and access to teleconferencing facilities for all universities and colleges will be needed. The overall approach should be informed by an understanding that “good teaching, unlike good research, does not lead to easily verifiable results but consists rather in a process”, as pointed out by the high-level Group on the Modernisation of Higher Education to the European Commission (High Level Group on the Modernisation of Higher Education, 2013[37]).