Remarkable economic development over the past 20 years has taken a heavy toll on the environment and the availability of resources in Viet Nam. Demographic and economic trends will exacerbate these environmental issues. Moreover, electricity demand is spiking, exerting pressure on national power capacity and environmental sustainability. To improve environmental quality, Viet Nam needs to strengthen horizontal and vertical institutional co-ordination, reform regulations to ensure coherence, implementability and enforceability, and streamline the use of policy instruments. Compliance assurance strategies need revision, while access to environmental information could improve their effectiveness. To achieve energy security and independence, Viet Nam has to rebalance its energy portfolio by better planning and financing the low-carbon transition.

Multi-dimensional Review of Viet Nam

7. Ensuring sustainability through better environmental and energy management in Viet Nam

Abstract

Remarkable economic development over the past 20 years has taken a heavy toll on the environment and the availability of resources in Viet Nam. Environmental pollution is imposing severe costs on society as a whole and the exploitation of natural resources raise concerns about future energy security. A high population growth rate, rapid urbanisation and accelerating industrialisation will exacerbate these environmental issues, further affecting the quality of life and constraining sustainable growth.

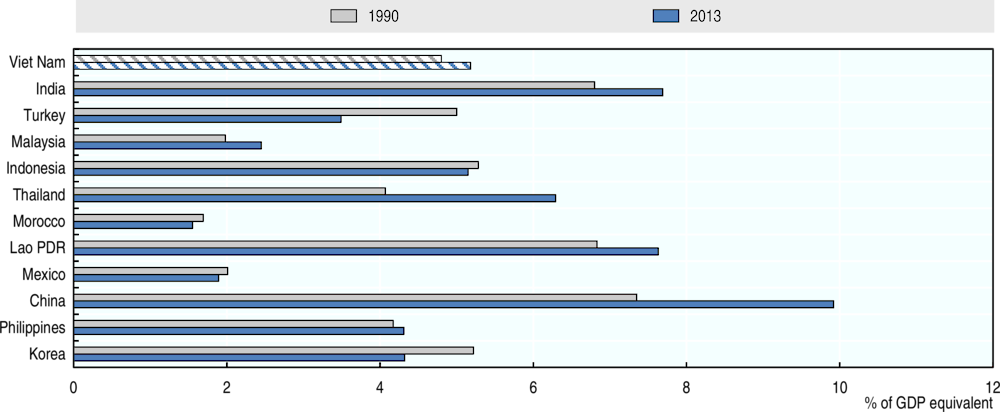

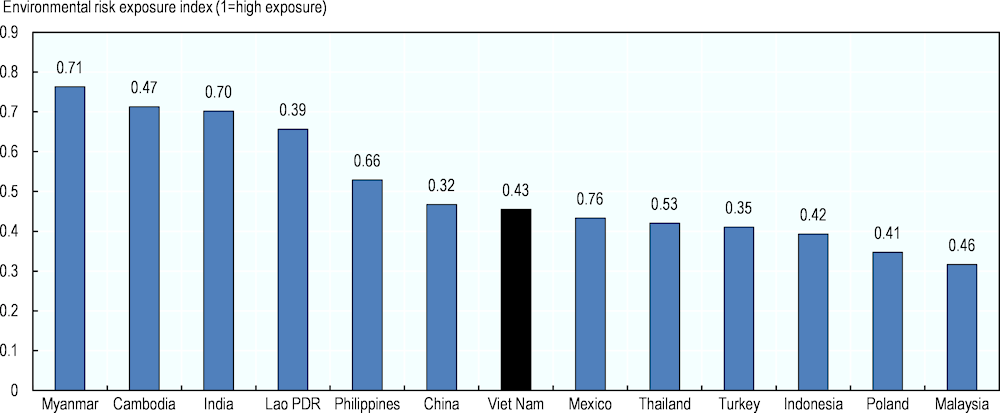

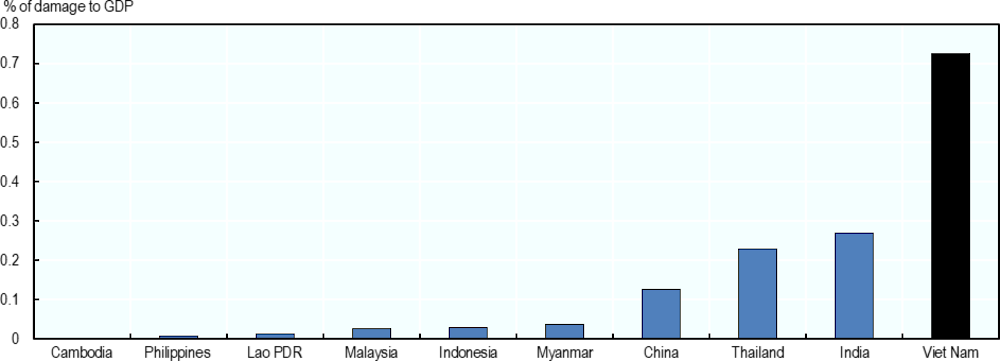

Several studies have estimated the impacts of poor environmental conditions on Viet Nam’s welfare. (Forouzanfar et al., 2015[1]) calculated that almost 50% of the annual burden of disease in Viet Nam can be attributed to exposure to environmental risk factors such as unsafe water and air pollution (Figure 7.1). The annual costs that these high environmental risk factors impose on the Vietnamese economy can reach up to more than 8% of GDP. According to estimates, the cost of air pollution has risen over the last two decades and represented more than 5% of GDP in 2013 (World Bank, 2016[2]) (Figure 7.2). Outdoor air pollution in Viet Nam today causes around 60 000 deaths per year (World Health Organization, 2018[3]). Meanwhile, estimates of the cost1 of water pollution from municipal sources are projected to amount to 3.5% of GDP by 2035 (World Bank, 2019[4]).

Figure 7.1. Environmental risk exposure in selected countries

Note: Environmental risk exposure is defined as the percentage of the total burden of disease observed in a given year that can be attributed to past exposure to environmental risk factors, including unsafe water (unsafe sanitation) and air pollution (ambient particulate matter pollution, household air pollution and ozone pollution).

Source: (Forouzanfar et al., 2015[1]).

Figure 7.2. Total welfare losses due to air pollution (% GDP)

Major reforms and planning efforts over recent years have raised expectations that have not as yet been met. The Government of Viet Nam has integrated environmental management into the main country development planning and strategy frameworks. The Five-Year Viet Nam Socio-Economic Development Plan for 2016-2020 incorporates measures to strengthen the management of natural resources and environmental protection, with ten primary objectives and solutions (Box 7.1). Prior to this, in 2012 Viet Nam approved the National Green Growth Strategy (VNGGS) for the period 2011-20. The focus of the VNGGS was to increase sustainable growth through the promotion of environmental goals and actions across different sectors of the economy and society. However, improvement in environmental outcomes is falling short of planned objectives (OECD, 2015[5]).

Box 7.1. The environment in national development strategies

In September 2012, Viet Nam approved the National Green Growth Strategy for the period 2011-20. The main objectives were to: i) restructure the economy by greening existing sectors; ii) encourage the use of technologies to promote more efficient usage of natural resources and to reduce greenhouse gas emissions; and iii) create an environmentally friendly lifestyle by generating employment in the green industry. The main strategy indicators and targets for 2020 are as follows: i) an 8-10% reduction in the intensity of greenhouse gas emissions as compared to 2010 levels; ii) 80% of commercial manufacturing facilities meet environmental standards; iii) 3-4% of GDP is invested in supporting sectors that protect the environment and enrich natural capital; iv) 60% (grade III cities) and 40% (grade IV and V cities) of wastewater collection and treatment systems meet regulatory standards; v) 100% of waste collection and treatment plants meet regulatory standards; and vi) a 35-45% share of public transportation use in large and medium cities.

Viet Nam’s Five-Year Socio-Economic Development Plan for 2016-2020, approved in 2016, acknowledges the importance of the environment for the country’s development. The Plan proposes to “effectively manage natural resources and environmental protection” as part of the country’s overall development objective. The following proposed actions are included: i) “inspect and handle environmental pollution, especially in countryside areas, traditional crafting villages and industrial clusters”, ii) “formulate and implement of natural hazards prevention”; iii) “protect the water sources, constructing infrastructure to ensure enough water is supplied for the production and consumption of enterprises and people”. Finally, the indicators and targets for 2020 related to environmental objectives are: i) 95% and 90% of the population has access to clean water in urban and rural areas, respectively; ii) 85% of hazardous waste is treated; iii) 95-100% of health care waste is treated; and iv) 42% forest coverage.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on SEDP 2016-20 and Prime Minister’s Decision No. 1393/QD-TTg dated 25 September 2012.

In addition to depleting environmental resources, electricity demand is spiking and exerting pressure on national power capacity. Between 2001 and 2015 electricity demand in Viet Nam grew at an annual average rate of 11% (World Bank, 2019[6]), and is projected to grow at around 8% per annum through 2035 (Danish Energy Agency, 2019[7]) . By then, Viet Nam’s total final energy demand is expected to be 2.5 times that of 2015 (Danish Energy Agency, 2019[7]), much higher than peers at a comparable level of development. Supplying electricity to meet this surging demand will require continuous expansion of Viet Nam’s installed capacity, which today stands at 53.3 GW. The Power Development Plan (PDP) VII, adopted in 2016, envisages that total installed capacity will rise to 60 GW in 2020 and 129.5 GW by 2030.

Energy security is at risk. The PDP VII plans to upgrade power capacity by expanding the country’s coal-fired plants. However, this represents a significant challenge for Viet Nam. New coal-fired plants will impose further costs in terms of environmental pollution, and the country will find it difficult to attract financing. For instance, of the 26 GW new coal capacity planned for installation between 2018 and 2022, only 7.9 GW was operational or under construction in 2017 (Direction Générale du Trésor, 2017[8]). Failure to install the required capacity in time risks power outages by the beginning of 2021. This has direct implications for economic growth (Vietnam Investment Review, 2018[9]) and forces the government to import expensive coal and electricity (Asia-Pacific Energy Research Centre (APERC), 2019[10]).

Rebalancing its energy portfolio to accommodate a greater share of renewables and other alternatives would help Viet Nam strengthen energy security, achieve greater energy independence and promote sustainable socio-economic development. With domestic fossil fuel resources falling short beyond 2021, exploiting domestically available renewable potential will be crucial to Viet Nam’s energy security and sustained economic growth. Thailand offers a good example in this regard (Box 7.2).

Box 7.2. The Thailand Integrated Energy Blueprint

In 2015, Thailand developed the Integrated Energy Blueprint (TIEB) to align its major energy sector plans covering 2015-36. The TIEB is a good example of integrated and holistic planning to achieve long-term energy security, sustainability and economic goals. The blueprint comprises five long-term plans that mutually reinforce each other.

The Energy Efficiency Development Plan focuses on improving efficiency through a variety of compulsory measures. The Power Development Plan aims to diversify the energy mix and achieve energy security including by reducing dependence on imported gas. The Alternate Energy Development Plan (AEDP) seeks to exploit domestic renewable energy potential and enhance its share in final energy demand. The AEDP further forms the basis of a strategic roadmap that aims to operationalise the objectives of the AEDP. The Natural Gas Supply Plan, among other things, targets improved security by reducing dependence on imported gas. Finally, the Oil Supply Management Plan seeks to create a transparent liquid fuels market with a policy framework based on fuel type, price and infrastructure investment.

The TIEB is supplemented by Energy 4.0, which focuses on the development and deployment of electric vehicles, energy storage technology, the bio-economy and smart cities in Thailand. Energy 4.0 complements Thailand 4.0 – Thailand’s economic model to enhance economic, environmental and social prosperity by 2032.

The rising levels of environmental pollution, natural resource degradation and energy insecurity will be an impediment to sustain future economic growth and the quality of life. The following sections attempt to diagnose the principal roadblocks undermining the effectiveness of Viet Nam’s environmental regulatory framework and slowing the clean energy transition in the country.

This report proposes five priority areas for public policy action:

Strengthening the institutional and regulatory framework for effective implementation

Managing water pollution

Managing air pollution

Managing natural hazards

Planning and financing the low carbon transition.

A workshop held in Hanoi in October 2019 gathered together national experts on environmental issues to discuss key obstacles to policy implementation with representatives of public agencies from the Government of Viet Nam. The discussions mostly concerned the country’s lack of a reliable environmental database, the lack of co-ordinated implementation and monitoring, the overlapping mandates between institutions, and scarce capacity to implement the environmental regulatory framework at the local level (Box 7.3).

Table 7.5 summarises the high-level and more detailed recommendations to pursue action in these five policy areas. It also includes a set of indicators to track the implementation of most of these recommendations.

Box 7.3. Results from the workshop “Tackling air and water pollution: What are the obstacles to effective legislation?”

Group 1: Strengthening environmental data, monitoring and information

The first group discussed the incompleteness and unreliability of existing environmental data. Coverage of the monitoring network is indeed limited, making measurement imprecise. Information is rarely disclosed to the public and sometimes does not flow between levels of government.

Participants suggested that information could become more reliable if the environmental database were to combine data collected by traditional and automatic stations, with satellite data and remote sensing data. In particular, ad hoc public-private partnerships could be created to install modern automatic monitoring stations. The Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment (MONRE) and provincial governments, as well as polluters, could establish mechanisms and protocols for information sharing – but incentives to encourage commitment are equally important. Moreover, authorities need to elaborate strategies for processing and disseminating environmental information, and making it understandable and accessible to the public.

Group 2: Improving institutional co-ordination

The second group discussed weak monitoring, co-ordination and accountability mechanisms among government institutions. Across government agencies and subnational governments, processes and procedures to implement environmental impact assessments (EIAs) and release environmental permits remain unclear.

Participants suggest that the mandates for tackling specific environmental issues (e.g. air and water quality) could be distributed more clearly and transparently among departments of MONRE. To account for the cross-cutting nature of some of the issues, there could be mechanisms to share information and co-ordinate implementation across national and subnational agencies. E-government platforms could help enhance co-ordination, transparency and efficiency in the implementation of environmental regulations. The clear distribution of assignments needs to be accompanied by an adequate distribution of resources and the establishment of specific accountability mechanisms. In particular, there could be frequent and independent evaluations of the performance of environmental administrators and agencies. Better co-ordination and transparency could then improve the way in which EIAs are implemented and environmental permits distributed.

Group 3: Fostering implementation

The third group concluded that implementation is slow because responsibilities and institutional roles overlap across numerous environmental agencies. Inspection and enforcement is often ineffective, the sanctioning system is not credible and investments in environmental protection are limited. Moreover, polluters seem to have only minimal information about environmental law and compliance requirements.

Regulatory impact assessments (RIAs) could help to streamline existing environmental regulations and fragmented institutional frameworks. To improve the effectiveness of inspections, inspectors would need specific training and a code of conduct, accompanied by standardised interpretation of regulations and an ability to impose sanctions. There should also be mechanisms in place to “inspect the inspectors” through the use of new technologies. Finally, specific campaigns targeting industry associations could help raise awareness about environmental regulations and compliance requirements among polluters.

Group 4: Promoting environmental management at the local level

A major obstacle to implementation is the limited technical capacity of districts and communes to enforce regulations. The necessary human resources are often unavailable and the understanding of laws is limited. Co-ordination mechanisms between local and other government levels is weak, with local administrators often failing to report upwards. Communication is moreover insufficient between local government, communities and enterprises, exacerbating the lack of awareness of regulations among polluters.

The group participants proposed to establish minimum technical qualification criteria for local environmental managers and to organise periodical training courses. The establishment of official channels and communication platforms at the local level could facilitate the flow of information and increase awareness among citizens and entrepreneurs in communities.

Strengthening the institutional and regulatory framework for effective implementation

Improve horizontal and vertical institutional co-ordination

Strengthen MONRE’s leadership in environmental management and establish information-sharing and accountability mechanisms with national and subnational level agencies for implementation

The institutional framework for managing the environment has evolved over the years. While MONRE2 has played a leading role in policy development, enforcement and implementation responsibilities have been gradually transferred to provincial and local governments. Joint responsibilities for policy implementation still exist between MONRE and subnational governments, creating overlaps and co-ordination problems (Table 7.1). For example, MONRE, provincial and local-level governments can all review and issue environmental permits. Similarly, inspection and administrative sanctioning of polluting facilities can be performed at both central and local level.

At the central level there are also gaps and inconsistencies in the definition of roles and responsibilities relating to environmental management between MONRE and other sector ministries.3 An example of this occurs in air quality management (Table 7.1). Over the years, the Ministry of Transport (MOT) has been assigned responsibility for steering activities to control urban air pollution, including air pollution from vehicle traffic; the Ministry of Industry and Trade (MOIT) has been assigned responsibility for controlling pollution in industrial parks (IPs) and industrial clusters (ICs); and MONRE has been given responsibility for managing the quality of ambient air and greenhouse gases. Such fragmentation means that no single authority has sole responsibility for consolidating and supervising efforts, which results in difficulties in co-ordinating air quality management (JICA, 2015[11]). Similar issues occur with respect to water quality and the roles played by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (MARD) and MOIT with respect to managing water pollution sources.

MONRE’s leadership role must be strengthened to enable it to supervise and consolidate efforts across sectoral ministries and subnational governments, particularly with regard to air and water pollution management. Information-sharing mechanisms and co-ordination protocols among different government levels should also be strengthened to ensure consistent implementation and monitoring of policies.

Table 7.1. Main agencies involved in air quality management in Viet Nam

|

Government body |

Main functions related to air quality management |

|---|---|

|

Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment (MONRE) |

Co-ordinates with other ministries and government bodies on overall environmental protection, including air quality. Vietnam Environment Administration (VEA), an agency under MONRE, performs the following functions: i) develops regulations and standards; ii) manages the EIA system; iii) monitors air quality; iv) controls and enforces policy implementation in co-ordination with provinces (inspects and sanctions); and v) mitigates air pollution caused by natural hazards and other incidents. |

|

Ministry of Transport (MOT) |

Develops regulations on environmental standards (emissions) for vehicles. Supervises vehicle inspection establishments, including emissions testing. Manages and monitors the implementation of EIAs for transport infrastructure in co-ordination with MONRE. Plans and develops the national investment plan for transport and regional traffic systems. |

|

Ministry of Industry and Trade (MOIT) |

Develops energy efficiency standards for industrial activities. Supervises and controls the air pollution from industries. |

|

Ministry of Construction (MOC) |

Manages and monitors the approval of licences and implementation of EIAs for projects under the Ministry, in co-ordination with MONRE and MOIT. Supervises and controls the air pollution from construction activities. |

|

Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) |

Issues national technical standards (TCVN), and national technical regulations (QCVN) for air pollution control. |

|

Ministry of Health (MOH) |

Issues regulations and standards for environmental protection in health activities (e.g. emissions from health care solid waste incinerators) Monitors the environmental impacts and pollution control of the health sector. Promotes the implementation of measures to protect human health from the impacts of air pollution. |

|

Ministry of Planning and Investment (MPI) |

Develops national development strategy documents. Monitors expenditures on environmental protection activities, including air quality management. |

|

Departments of Natural Resources and the Environment (DONREs) |

Assist with the implementation of state management tasks in air pollution control. Conduct inspections to ensure compliance with regulations and sanctions non-compliance. Develop air quality monitoring networks and disseminate information. Evaluate EIAs and monitor the implementation of environmental protection measures. Receive funding from state-level budgets and provide financial assistance and loans for projects and activities to reduce air pollution. |

Source: OECD research.

Another important issue raised by the decentralisation of policy implementation is conflicts of interest. While decentralisation has brought responsibilities to agencies that are closer to local environmental issues, this has resulted in potential conflicts of interests between local development and environmental protection. This is particularly apparent in cases where permit issuing and enforcement functions are conducted by the same subnational government institution. The political emphasis of local authorities on economic growth increases the risk of interference in favour of local development at the expense of the environment. Local development planning focuses more on meeting targets related to economic growth, employment generation and the reduction of poverty. As a consequence, environmental quality targets that could increase accountability in environmental management are often absent at the subnational level and should be given more attention. However, proper incentives and accountability mechanisms could be established using environmental targets to assess the performance of subnational governments with respect to environmental management. In this regard, the lessons learned in countries such as China provide a relevant example for Viet Nam (Box 7.4).

Box 7.4. China’s paradigm shift towards environmental performance accountability at the subnational level

In recent years, China has undergone a paradigm shift in terms of strengthening top-down incentives for environmental management. The 11th Five-Year Plan (2006-10) established environmental targets as part of performance evaluations for subnational governments. High-priority quantitative pollution reduction and energy efficiency performance targets were assigned by the central authorities to governors, mayors and SOEs leaders through the cadre evaluation system. This top-down bureaucratic personnel evaluation system was used by the central government to harness the decentralised governance system by establishing stronger incentives for local leaders. It was expected that this approach would overcome an extensive environmental regulatory framework that had achieved few results. The resulting implementation process provided lessons and key information about remaining challenges.

Initially, the new environmental targets triggered major investments in pollution control infrastructure as well as other actions such as the closure of thousands of outdated industrial production facilities. However, some of these measures produced counter-productive outcomes due to the shutdown of pollution control equipment, the falsification of environmental information by local agents and the reopening of some of the closed factories.

Reforms had to be undertaken to strengthen supervision at the local level. The central authorities invested significantly in top-down environmental monitoring, both in terms of infrastructure and capacity building of staff. New technologies were introduced to allow independent assessments of pollution reduction, circumventing local data manipulation in official local government’s reports. Public participation in supervision was also enhanced, providing an independent third-party check of local governments and enterprises. NGOs were allowed by law to sue polluters in the public interest and 24-hour hotlines were established for citizens to make environmental complaints.

Overall, the paradigm shift resulted in the empowerment of environmental authorities, promoting greater co-operation among agencies and fostering public participation in supervision. The effects of the initial paradigm shift have produced results over time, although challenges remain. Political incentives have contributed to more effective pollution reduction (He, Wang and Zhang, 2019) and the country’s expenditure on environmental protection has increased reaching 1.2% of GDP. Approximately USD 130 million was spent in 2015, mostly on industrial pollution reduction. The 13th Five-Year Plan for 2016-20 continues to include binding targets for key environmental parameters such as pollutant discharges and air quality.

Source: Adapted from (World Bank, 2019[6]; Wang, 2013[12])

Increase the local presence of MONRE and the VEA through local office delegations in order to improve co-ordination with subnational governments on environmental permits and enforcement functions

In addition to information sharing and co-ordination mechanisms, the increased local presence of central government agencies such as MONRE and the VEA can contribute to more effective implementation. Local delegations can contribute to improving the following aspects: i) dialogue with local governments in terms of regulation design and application in local areas; ii) capacity building of local officials for regulation implementation; iii) co-ordination of monitoring and enforcement activities between central and local agencies to avoid duplication of inspections; and iv) monitoring of policy implementation, with local officials better trained in reporting mechanisms. Recent approaches to increase the local presence of national environmental enforcement agencies in Mexico and Peru can be adopted in Viet Nam (OECD, 2013[13]; OECD, 2016[14]).

Formulate national environmental programmes for co-ordination by MONRE and implementation by subnational governments

The transfer of environmental responsibilities to subnational governments over recent decades has not always been accompanied by adequate allocation of financial resources, hampering the implementation capacity of provincial and municipal governments. Furthermore, consultation on environmental policy design and guidance regarding implementation at the local government level has been limited. As a result, uneven local capacity has resulted in regionally differentiated implementation outcomes. This situation is especially visible in terms of air, water and waste management, three environmental policy areas where subnational governments need to engage in significant public investment and require the technical capacity to undertake implementation. The formulation of national programmes, with earmarked funds co-ordinated by the central environmental authority and implemented by subnational governments, can be an effective means to build local capacity. National, specialised environmental programmes have the advantage of providing consistent technical capacity building across regions, while providing funds to implement best practice measures to reduce pollution. International experience provides examples of how countries have improved local capacity for environmental policy implementation through national programmes (Box 7.5).

Box 7.5. Experiences in building vertical and horizontal co-ordination mechanisms in Mexico and Peru

In Mexico, the Ministry of Environment (SEMARNAT) and the Environmental Enforcement Agency (PROFEPA) have delegations at the state level as well as a presence at the subnational level. This has resulted in the following achievements: i) the creation of dialogue with local governments in terms of regulation design and applicability in local areas; ii) capacity building of local officials for the implementation of regulation; iii) improved co-ordination of monitoring and enforcement activities between federal and local agencies, avoiding duplication of inspections; and iv) improved monitoring of the implementation of policies, with local officials better trained in reporting mechanisms.

Mexico has also addressed the local implementation capacity gap (due to the lack of funding and technical capacity) by creating national programmes for the environmental management responsibilities transferred to subnational governments. The National Programme for Air Quality (ProAire) and the National Waste Management Programme are good examples in this regard. Joint action between federal and state authorities proved effective in implementing ProAire, a programme created to improve air quality in more than 15 metropolitan areas. Similarly, the National Waste Management Programme operated more than 30 state and 84 municipal programmes for integrated waste management and prevention. Such programmes can be an effective mechanism for implementation provided that: i) the central government transfers funds to subnational governments in cases where the local government has a limited budget for environmental management; ii) the use of funds is linked to standardised best-practice measures (including investment in waste management or air emissions reductions), thereby reducing the arbitrary use of funds; iii) technical assistance is provided to local governments as part of the programme; and iv) monitoring and reporting is standardised, facilitating co-ordination and supervision.

Finally, in Peru, results-based budget programmes were created at the national level with specific sectoral goals and targets such as environmental protection or disaster risk management. National-level agencies and subnational governments can access these funds, which are earmarked for sector-level interventions. These programmes ensure that the use of funds is aligned to efforts to obtain specific results and outcomes for the environment.

Source: (OECD, 2013[13]; OECD, 2016[14]).

Reform regulations to ensure coherence, implementability and enforceability

Environmental regulation has been developed through a process of continuous updating and improvement over recent decades. The first Law on Environmental Protection (LEP) was approved in 1993; this was replaced by a new law in 2005 and ultimately superseded by the LEP of 2014. Numerous decrees, circulars and decisions have been introduced to amend various parts of the regulation and also provide specific guidance on how to implement different regulatory aspects.4 However, weaknesses remain in terms of applicability and enforceability. A lack of adequate environmental information and regulatory analysis has hampered the regulation’s design and effectiveness, while other approved laws covering aspects related to the environment overlap with the LEP or create inconsistencies.5

Strengthen the environmental information base for adequate regulation and enforcement

The existing system for monitoring environmental quality and pollution sources is inadequate and unable to generate reliable information for effective regulation design and enforcement. Coverage of the environmental monitoring network is limited and quality assurance is hampered by a lack of technical and financial resources. Additionally, fragmentation of the monitoring system has contributed to a reduction in the reliability of information available at the local and central level. Current mechanisms and protocols for exchanging information between provincial governments and the main environmental agency have not been effective. Ultimately, monitoring coverage has concentrated on selected pollutants, with inventories of polluters developed for particular hotspots such as Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City.

The first step in re-designing the system would be an evaluation of the existing environmental quality monitoring programme with respect to its purpose and objectives. A balance will need to be struck between the financial and human resources available to operate and sustain the monitoring network, taking into account its size, sophistication and coverage (Box 7.15). The main objectives to be considered for the re-design of the system relate to the need for timely public reporting (e.g. pollution levels and environmental quality) and compliance (e.g. exceedance of permitted levels with respect to standards, pollution trends, causes of elevated concentrations, and formulation and evaluation of pollution control strategies). Finally, quality assurance and control protocols and procedures must be established to verify and maintain the precision, accuracy and validity of measurements (Clean Air Asia, 2016[15]).

In addition to environmental quality data, polluter inventories are critical pillars for effective environmental management (UNECE, 2012[16]). According to the (EEA, 2019[17]), inventories are suitable for: i) defining environmental priorities and identifying the activities responsible for the problems; ii) assessing the potential environmental impacts and implications of different pollution strategies and plans; iii) evaluating the environmental costs and benefits of different policies; and iv) monitoring the state of the environment, checking that targets are being achieved and helping to ensure that those responsible for implementing policies comply with their obligations.

As the quality of environmental information improves, it can be integrated with economic information to provide valuable inputs for policy assessment at a macroeconomic level. This new information can be instrumental in mainstreaming environmental sustainability into the design of country development strategies and sector policies. Many countries have in fact expanded their Systems of National Accounts to include environmental components, resulting in a System of Integrated Environmental and Economic Accounting (SEEA), based on a methodology developed by the United Nations Statistics Division. A SEEA can bring coherence and consistency across different sets of environment statistics and provide a more complete picture of the economy, taking into consideration resource flows and stocks and the corresponding monetary transactions. Several countries have used SEEAs as a key measurement framework for environmental and economic trade-offs, enabling them to standardise the reporting of relevant data. Additionally, SEEAs have been used as inputs for policy analysis in emerging countries (Banerjee et al., 2019[18]). For countries where there is as yet little active environmental protection, such as Viet Nam, the measurement of flows of residuals (e.g. emissions and solid waste) can be used to determine the urgency of environmental protection regulation (UN, 2014[19]). Box 7.6 provides a brief description of the recommended approach to implement a SEEA at country level.

Box 7.6. Approach for the implementation of a SEEA at country level

Implementation of a SEEA as part of a country’s national statistical system is a valuable and significant investment. The main phases and steps that should be considered are as follows:

Phase 1: Strategic planning

This phase involves establishing a core group on environmental-economic accounting consisting of participants familiar with national sustainability, economic and environmental policies, national accounts and environment statistics. The group should include a senior representative from the government agency considered to be the “sponsor” of environmental-economic accounting in the country, such as a planning agency. In addition, it should feature a senior representative from the government agency that will take the lead role in compiling the SEEA accounts, typically the central statistical agency. The core group should complete an initial national assessment report which will provide complete coverage of the institutional and data environment where implementation of the SEEA will take place. This report should cover the following aspects: stakeholders and institutional arrangements; policy priorities, targets and indicators; data sources; existing accounts; challenges and opportunities; recommendations for priority accounts and next steps.

Phase 2: Building mechanisms for implementation

The first part of this phase builds on the initial core group established in Phase 1 to create an authorised senior board or group capable of overseeing and facilitating implementation of the work programme. A strategy statement can be prepared for implementation of the SEEA and the operation of the senior group, including a mission statement, values, high-level goals, specific objectives and required activities.

The second part of the phase involves the formation of relevant implementation teams. These should be technically focused on the issues involved in compiling specific sets of accounts, and draw on the national assessment report for direction. They will be responsible for developing a more detailed assessment of specific information needs and requirements for policy purposes and a more detailed assessment of data availability. The teams will involve all relevant stakeholders, working across agencies and building support for ongoing collaboration, in particular by establishing data-sharing agreements based on the requirements for environmental accounting.

Phase 3: Compiling and disseminating accounts

This phase is the most resource demanding, and thus it is important that adequate funding is available to finance upfront costs for training and systems development.

Initially the compilation of environmental-economic accounts should focus on developing experimental or preliminary accounts at a summary level. Available data should be used to start the process, demonstrating the potential of the approach to users and building an understanding of compilation using an accounting approach. This learning-by-doing method is an essential aspect of implementation and should include the release of preliminary data to encourage feedback from as broad a constituency as possible. Based on feedback and increasing confidence in compilation it should be possible to progressively develop any set of accounts to improve data quality, the degree of detail in response to user demands and ultimately the range of different accounts.

Phase 4: Strengthening national statistical systems

This phase focuses on ensuring that the selected accounts are produced regularly, and will require not only a commitment in terms of long-term funding, but also a training and knowledge transfer programme to ensure succession after staff turnover. At the same time, outreach programmes should be designed to promote usage of the accounts.

Source: Adapted from (UN, 2014[19]).

Introduce ex-ante regulatory impact analysis as well as consultations with the public and the agencies responsible for enforcement and implementation

The process leading to the drafting of laws and regulations suffers as a result of being top-down and having limited ex-ante analysis of regulatory impacts and implementation requirements. As a result, regulations are difficult to comply with and enforce. For example, although several national technical regulations (QCVNs) for emissions standards on air pollutants have been approved, enforcement is difficult to implement at the central and local level due to lack of technical and administrative capability (JICA, 2015[11]). In some cases, technical regulations contain hundreds of substances listed as targets and enforcing them all is not practical. In other cases, the measurement methodologies and onsite calibrations are not clearly specified. Regulations also tend to introduce new actions without clearly specifying the means nor a target for completion. For example, the proposal to build an industrial emission database from Decree No. 40/2019/ND-CP of 2019 dated 13 May 2019 on “Amending and Supplementing a Number of Articles of Decrees Detailing and Guiding the Implementation of Environmental Protection Law” has no target date.6 In other cases, targets are unrealistic and difficult to meet.

International experience in the assessment of environmental regulations can be useful in the re-design of existing regulations for increased effectiveness (Box 7.7). Regulatory impact analysis can be used to better inform regulations for increased compliance, and assessment of policy implementation needs can be used to set more realistic goals for the enforcement and implementation of environmental policies.

Box 7.7. Experiences of improving environmental regulations in Europe

In the policy debate on better legislation at the European and national level, there is growing consensus on the need to address the implementation deficit. EU legislation, including environmental legislation, is too often not properly or fully implemented across Europe. There is real evidence of practicability and enforceability problems caused by the way in which legislation is designed and written, and by poor implementation conditions. In this context, the Better Regulation Initiative promulgated the following criteria for effective regulations:

Regulations should be well-founded, based on facts and with knowledge of their expected impacts.

Regulations should be prepared in a transparent way, involving all parties concerned.

Regulations should be effective, efficient, proportional and not lead to undesirable economic, social or environmental consequences or to unnecessary administrative burdens for businesses, citizens or authorities.

Regulations should not lead to unwanted discrimination, frustrate a level playing field or hinder innovation.

Regulations should be clear, consistent, understandable and as simple as possible. They should not contradict other regulations.

Regulations should be compliable, practicable and enforceable.

The “Better Regulation” initiative was applied to environmental regulation on air quality in the European Union. The European Commission adopted an air quality thematic strategy in 2005 together with focus on ambient air quality and cleaner air for legislation in 2008 and 2013, respectively. This air quality package merged five separate legal instruments to control air pollution into a single directive, taking into account the difficulties encountered by EU countries in complying with existing regulations. The main objective was to simplify regulations and introduce flexibility in meeting deadlines. Work with Member States on improving monitoring tools and simplifying reporting was also undertaken. The quality of the preparations of the air quality package, including the modelling and cost-benefit analysis, assisted policy makers in deciding on targets for air pollution reduction efforts. Furthermore, impact assessments were useful in measuring progress and taking costs and benefits of regulation more clearly into account throughout implementation. As progress was monitored and new data were available, the regulation focused more on the challenges of implementing existing legislation rather than introducing more stringent standards. In fact, regulation allowed Member States to set less stringent emission limit values if the application of best available techniques would lead to “disproportionately higher costs” compared to the environmental benefit.

The European Union Network for the Implementation and Enforcement of Environmental Law (IMPEL) assessed the practicability and enforceability of existing and new environmental regulation, and provided several recommendations on how to improve the efficiency of environmental inspection authorities:

Promote greater use of alternatives to bespoke permits (e.g. general binding conditions).

Sector-based approaches can be effective (i.e. seeking to agree performance objectives beyond minimum regulatory standards).

Streamline or integrate approaches for companies which are carrying out similar activities across multiple sites.

Bring different types of inspection activity together in a single or harmonised process in order to increase coherence and reduces cost to business and authorities.

Identify opportunities for other inspectorates, or even commercial organisations, to undertake areas of inspection activity where it is more effective to do so.

Relatively few initiatives include an assessment of the intended benefits regarding environmental outcomes, or cost savings to business and regulatory bodies.

Source: adapted from (OECD, 2019[20]; Golberg, 2018[21]; IMPEL, 2013[22]; IMPEL, 2009[23]; IMPEL, 2006[24]).

Assess ambient quality standards and emission limits based on technical and economic feasibility

An important instrument contemplated by the Environmental Protection Law is the system of environmental ambient quality standards (EQS).7 EQS stipulates maximum allowable concentrations of pollutants by environmental media (air, water or land) with the objective of protecting human health and the environment. Emission limits values have also been developed for different air and water pollution sources.8 However, enforcement of and compliance with existing emission limits has been difficult for several reasons. As a result, environmental quality standards have not been met in several parts of the country.

Lack of accurate environmental quality information, inventories of emitters and available technologies have resulted in the setting of unrealistic standards at the outset. Standards were initially transposed from other countries’ regulatory frameworks and resulted in very strict emission limits that required high levels of investment to ensure compliance. They were revised afterwards. However, the technical complexity of the subject matter and the lack of qualified experts to assess alternative standards have also limited efforts to set more realistic, achievable targets. International best practices suggest that local industries need adequate support and guidance – as well as sufficient time – to comply with the standards. For each equipment and process, information on best available technologies, guidelines on design operation and maintenance for emission reduction should be developed in close co-ordination with the industry (Box 7.8). In several cases, the standards do not prescribe specific abatement methods, but their values are set based on reference end-of-pipe pollution control technologies instead of integrated process solutions (i.e. cleaner production technologies).9

There is now widespread recognition of the need to reform several of the emission limits and ambient quality standards. However, the limited information and analysis of air and water pollution sources, and their impact on ambient quality, precludes meaningful re-design of the environmental standard system. It is therefore critical to focus resources on monitoring and analysis of pollution sources as a first step towards reforming the system. Building on improved environmental information, the revision of standards should strike a balance between what is feasible from a technical and economic standpoint from the perspective of both the polluter and the enforcement agency (Box 7.8). Efforts should be concentrated on polluting substances that pose the greatest risk to human health and the environment.

Box 7.8. The EU Industrial Emissions Directive: An example of best -practice in regulation design for environmental standards

The Industrial Emissions Directive (IED) is the main EU instrument regulating pollutant emissions from industrial installations. Approved in 2010, the IED recasts seven existing Directives into a single clear and coherent legislative instrument. The directives in question were the Integrated Pollution Prevention and Control (IPPC) directive, the Large Combustion Plants Directive, the Waste Incineration Directive, the Solvents Emissions Directive and three Directives on Titanium Dioxide. The IED aims to achieve a reduction in industrial emissions harmful to human health and the environment. Installations undertaking industrial activities with specific characteristics need to operate in accordance with a permit that sets their emission limits. The following best practice aspects of the regulation are worth emphasising:

The integrated approach of the IED takes into account the overall environmental performance of the plant, covering air, water and land emissions, the generation of waste, etc.

The IED is based on a practical approach to emissions reductions. The permit conditions include emission limits based on the best available techniques (BATs). BATs are defined based on an assessment and discussion among technical experts, industry and environmental organisations. They provide information to decision makers about relevant techniques that are economically viable and technically available to industry in order to improve their environmental performance.

Flexibility is allowed in setting emission limit values if the application of BATs would lead to “disproportionately higher costs” compared to the environmental benefits. In other cases, provisions such as transitional plans allow additional time for installations to comply with limits.

The public has the right to participate in the decision-making process and has access to permit applications and the results of pollutant monitoring. A European pollutant registry was created and made publicly available.

Existing analysis of the results of IED implementation suggests that trends in air emissions have been negative for the installations under regulation. EU industry emissions of sulfur dioxide (SO2) and dust particles have halved since 2007. The leather industry reduced emissions of harmful water pollutants, such as heavy metals, by over 90%.

Streamline the use of policy instruments such as SEAs, EIAs and environmental permits

The strategic environmental assessment (SEA) and environmental impact assessment (EIA) are among the main environmental policy instruments proposed by the Environmental Protection Law. The SEA was envisioned to identify and mitigate possible environmental impacts of plans, policies and programmes. However, limited progress has been made in terms of implementation and further technical guidance and capacity needs to be developed.

The EIA was originally envisioned as an instrument to aid the public administration in identifying the potential impacts of an operation of activity on the environment. EIAs are also used to develop environmental protection plans to reduce impacts to an acceptable level based on existing environmental standards and pollutant limits. Depending on the type of environmental impact, an EIA is approved by a national or subnational environmental authority and an environmental permit or license is issued. The competent authority is then responsible for monitoring implementation of the environmental protection plan approved in the EIA.

The EIA process and permit system have undergone several revisions since its original adoption.10 While progress has been made in conducting EIAs, their effectiveness has been limited by regulatory design and institutional weaknesses. Currently, they are required for a large list of activities;11 however, agencies have a limited capacity to supervise and monitor both EIAs and environmental permits. The existing process can be simplified for activities with a low impact on the environment, with prioritisation focused on efforts to screen and monitor the environmental protection plans of activities with a high impact on the environment. Integrated pollution permits12 can also be introduced for large stationary sources to reduce administrative burdens.

The EIA appraisal and monitoring process could benefit from standardisation. Specialised technical guidelines for different sectors can be developed and EIA reporting requirements standardised, thereby streamlining the process and making it more objective. Cumulative impacts to the environment should also be appropriately assessed as part of the EIA process13 and public consultation further developed.14 Finally, the introduction of online management systems for EIAs and licensing has the potential to: i) expedite processes; ii) improve co-ordination and information sharing across government levels; and iii) compile relevant information of polluters and environmental quality. International experience in the use of new technologies and the redesign of environmental permitting systems is presented in Box 7.9.

Box 7.9. Using new technologies to streamline the environmental permit system and consolidate strategic environmental monitoring

The European Union Network for the Implementation and Enforcement of Environmental Law (IMPEL) has documented good practice cases related to the Integrated Regulation Programme established in England and Wales. This programme was established to streamline regulatory activities such as permitting, reporting and inspections. A national managed ICT framework was created to integrate all data and ensure that activities were not duplicated, and data were used to improve results. The countries then introduced integrated environmental permitting. The new system incorporated all licensing requirements into a single system, without changes to any environment or health protection standards. The system also enabled the planning of combined environmental inspections, thereby decreasing workloads per inspection while increasing coverage.

Another example of good practice is the EU centralised online database created for the Industrial Emissions Directive. This database provides citizens with information on environmental permits for installations and fosters their participation in the process. Implementation of the database has created incentives and opportunities for EU countries to: i) ensure transparency when applying environmental rules, and facilitate public participation and objections; ii) improve communication among regional governments, permit applicants, communities and the public; and iii) streamline permitting procedures for companies.

El Salvador provides a best practice example from a developing country of an effective reform to streamline and increase the transparency and accountability of an EIA and permit system. The strategic approach taken for the reform involved different phases and produced several results: i) stakeholders were engaged to develop new categorisations and clear rules; ii) administrative requirements were simplified from 14 to only 1; iii) the new categorisations for activities were approved based on the scope and sensitivity of the environment (for each project); iv) standard terms of reference were developed (one general TOR and technical guidelines for sectors); and v) application forms were reduced from 27 to only 1, which could be submitted via an online platform.

Additionally, an online platform was created containing the following features: i) online permit applications with built-in categorisation and streamlined requirements; ii) automated draft permits generated for low-impact project proposals, including municipal permit issuance; iii) tailored standard self-reporting forms for monitoring; and iv) a web-based system to enable public access to permits, monitoring, complaints and enforcement. Finally, plans were made to link the online system to a GIS-driven analytical tool in order to provide instantaneous access to distributed environmental, social and economic data via web services for reviewers and preparers of EIA documents.

The case of El Salvador illustrates how the introduction and use of new technologies has the potential to strengthen the EIA and permit process through greater access, transparency, accountability, and ultimately improved environmental results and environmental management efficiency.

Source: Adapted from (Castaneda, 2018[28]; European Commission, 2018[29]; Wasserman and Nieto, 2015[30]; IMPEL, 2009[23]).

Revisit compliance assurance strategies for increased effectiveness

Viet Nam has made some progress with respect to compliance assurance. The Vietnam Environment Administration (VEA), the central government’s enforcement agency, has been operating for almost a decade and has received international technical support. While their technical capacity has been strengthened, existing regulatory weaknesses combined with limited co-ordination mechanisms with local governments have limited the VEA’s effectiveness.

Increase inspection and enforcement capacity at the local level and strengthen supervision mechanisms

Overall, the capacity to detect non-compliance has been limited. Scarce human resources and unclear enforcement procedures have hampered the effectiveness of inspections, particularly at the local level. Indeed, public complaints about pollution incidents have proven more effective in detecting non-compliance. While the new requirements for continuous environmental monitoring set forth by Decree No. 40/2019/ND-CP may help strengthen the capacity to detect non-compliance, additional resources and capacity are needed for effective implementation.

The capacity to enforce environmental regulations such as emission limits will benefit from an improved environmental information monitoring system for polluters and pollution substances. In some cases, the number of pollutants to be monitored will have to be adjusted based on existing capacity. For example, over 100 parameters pertaining to surface water quality standards are regulated, yet the number of parameters that can be monitored in practical terms is smaller. Enforcement procedures must also be clarified to allow for effective implementation. Additional inspectors need to be hired and existing ones must be trained to adequately perform their tasks at the local level. Laboratories also need to be equipped to analyse samples with the required level of specificity for pollution issues (World Bank, 2019[4]). Finally, supervision mechanisms between the VEA and local environmental enforcement authorities should be strengthened.

Revise the administrative penalty system

Administrative penalties for violation do not seem to effectively deter behaviour for several of the polluters. This raises the question of whether penalties are not sufficiently high or are not really collected,15 with only limited information publicly available on fines both imposed and collected. Environmental liability must be aligned to the polluter-pays principle since payments are not entirely based on actual harm to the environment and the cost to remediate it. In fact, additional assessments need to be conducted to evaluate the extent of environmental damage, available remediation measures, their costs and the criteria for selection. International best practice suggests that the rates applicable and fines should be realistic, transparent and aligned with environmental policy objectives (OECD, 2009[31]).

Use information and market-based instruments to promote compliance

Opportunities exist to expand the use of information and market-based instruments to complement existing compliance assurance strategies. The existing experience of the Vietnam Environment Protection Fund (VEPF), which provides access to financing and technical assistance for pollution control technologies, can be scaled up. The use of information-based instruments such as public disclosure schemes and education and awareness raising campaigns (school curriculum, use of role models, advocacy by leaders, advertising, etc.) can also contribute to galvanising support towards further compliance (Box 7.10).

Box 7.10. The Viet Nam Environmental Protection Fund (VEPF)

The Vietnam Environmental Protection Fund (VEPF) is a state-owned financial institution under MONRE that was created in 2002. The VEPF provides concessional loans (under better conditions than the market) and other financial services (grants, post-investment interest rate subsidies, subsidies) for environmental management activities. At the end of 2018, concessional loans represented 84% of capital allocation, grants accounted for 7%, interest rate incentives represented 4.8% and wind-power subsidies amounted to 3.7%. The main sources of capital for the VEPF have been state budget, fees from selling certified emissions reduction, and domestic and international organizations. The priority sectors of intervention of the Fund are: i) industrial wastewater treatment (in industrial zones); ii) domestic wastewater treatment; iii) wastewater and emissions treatments (factories and craft villages); iv) domestic waste treatment; v) energy-efficient production and renewable energy.

Up until the end of 2017, the VEPF has allocated USD 106 million in credits distributed in 293 projects, in 56 provinces of the country (Table 7.2). Industrial and domestic wastewater treatment have represented more than 35% of fund allocations, followed by energy-efficient production and renewable energy with a 19% allocation.

Table 7.2. VEPF allocations

|

Rank |

Sector |

Financing (% total) |

|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Industrial wastewater treatment (industrial zones), domestic wastewater treatment |

36 % |

|

2 |

Environmentally friendly technology, energy-efficient production and renewable energy |

19% |

|

3 |

Environmental and recycled products |

16% |

|

4 |

Hazardous, industrial waste treatment |

10% |

|

5 |

Domestic waste treatment |

9% |

|

6 |

Waste water and emissions treatments (factories, craft villages) |

6% |

Source: Adapted from www.vepf.vn.

Other market-based mechanisms such as charges, taxes, subsidies, fees or tradable permits may contribute to promoting pollution reduction. Experience in implementing these types of instruments in non-OECD countries has achieved positive results. For example, in China, pollution discharge levies were imposed on a number of pollutants that were discharged into the air, water or land (Box 7.11). Observations indicate that firms reduced their pollution intensity due to the discharge levies (He, Wang and Zhang, 2019[32]; Blackman, Li and Liu, 2018[33]).

Box 7.11. Public disclosure schemes on polluter performance

The Green Watch programme was a public disclosure programme for industrial polluters in China. Local government agencies were required to publish lists of polluters exceeding discharge limits. Information on the regulated community was compiled by local environmental agencies and used to evaluate firms’ environmental performance. The programme used a colour code to indicate compliance with the colours green, blue, yellow, red and black indicating performance (from best to worst). The colour rating results were published in local newspapers and broadcast on local TV and radio (and in some provinces on the Internet). Local agencies used this information to better target their inspections, thereby ensuring that limited resources were used more efficiently.

Other instruments were also used to exert public pressure on polluters in China. Databases of environmental offenders were created and shared with banks and other regulatory bodies. Poor environmental compliers would have to pay higher interest rates when applying for a loan, and in some cases, would be denied credit.

Source: Adapted from (OECD, 2009[31]; OECD, 2006[34]).

The use of economic instruments needs to be aligned to contribute to the achievement of key environmental policy objectives. The system of pollution charges is used only for water emissions, although there are discussions underway to introduce it for air emissions.16 Additional information on actual emissions must be collected to assess the right price level to encourage behaviour change and achieve better environmental outcomes. Effective collection mechanisms must then be established accordingly. The experience with water pollution fees17 suggests that fees are not always charged, and their collection is not always used towards environmental protection activities (World Bank, 2019[4]). This reinforces the idea that a reliable system for monitoring and enforcement of emission levels will also be critical for the effectiveness of market-based instruments.

As significant additional private and public investments will be required to improve environmental outcomes, adequate incentives need to be provided to ensure that outcomes are achieved in the most efficient and effective manner. Information and market-based instruments can play a significant role in providing adequate incentives.

Public participation and access to environmental information need to be strengthened

Although the regulatory framework contains provisions for public participation and access to environmental information, in practice the system for public participation and access to information on environmental matters is fairly restricted. International best practice is available on how to improve these aspects related to environmental democracy (UNEP, 2010[35]).

While NGOs are involved in strategic policy discussions, public participation in law making remains limited. Public participation in the EIA and SEA is restricted to residents of the area affected by the proposed project or plan and does not include the wider public. EIAs are not normally announced in the mainstream media, and public hearings serve mostly to inform rather than seek comments. Moreover, the authorities are not obliged to accept citizen’s proposals. Developing an effective conflict resolution mechanism to ensure that the government works in partnership with civil society and NGOs could help to alleviate future tensions due to environmental incidents.

MONRE provides a range of environmental information to the public, including an annual state of the environment report and an annual environment statistics yearbook. Records on permit applications and inspection reports are not readily available to the public. Despite growing disclosure of environmental information, the existing system for monitoring environmental quality and polluters has limited coverage and the quality of the data is questionable. Further protocols should be developed to ensure that information such as records on regulated entities, polluter registries and other relevant information produced or managed by the government is available to the public (Box 7.12). Finally, regulations do not attribute any obligation to government agencies in terms of disseminating relevant environmental information when environmental emergencies arise.18

Box 7.12. The Bali Guidelines on public participation and access to information

In February 2010, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) adopted the “Guidelines for the Development of National Legislation on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-making and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters” (The “Bali Guidelines”). The Guidelines seek to assist countries in filling possible gaps in their respective relevant national legislation, and where relevant and appropriate in subnational legal norms and regulations at the state or district levels, ensuring consistency at all levels to facilitate broad access to information, public participation and access to justice in environmental matters.

In terms of access to environmental information, the following principles were developed:

1. Any natural or legal person should have affordable, effective and timely access to environmental information held by public authorities upon request (subject to guideline 3), without having to prove a legal or other interest.

2. Environmental information in the public domain should include, among other things, information about environmental quality, environmental impacts on health and factors that influence them, in addition to information about legislation and policy, and advice about how to obtain information.

3. States should clearly define in their law the specific grounds on which a request for environmental information can be refused. The grounds for refusal are to be interpreted narrowly, taking into account the public interest served by disclosure.

4. States should ensure that their competent public authorities regularly collect and update relevant environmental information, including information on environmental performance and compliance by operators of activities potentially affecting the environment. To that end, States should establish relevant systems to ensure an adequate flow of information about proposed and existing activities that may significantly affect the environment.

5. States should periodically prepare and disseminate at reasonable intervals up-to-date information on the state of the environment, including information on its quality and on pressures on the environment.

6. In the event of an imminent threat of harm to human health or the environment, States should ensure that all information that would enable the public to take measures to prevent such harm is disseminated immediately.

7. States should provide means for and encourage effective capacity-building, both among public authorities and the public, to facilitate effective access to environmental information.

In terms of public participation, the following principles were developed:

1. States should ensure opportunities for early and effective public participation in decision making related to the environment. To that end, members of the public concerned should be informed of their opportunities to participate at an early stage in the decision-making process.

2. States should, as far as possible, make efforts to seek proactively public participation in a transparent and consultative manner, including efforts to ensure that members of the public concerned are given an adequate opportunity to express their views.

3. States should ensure that all information relevant for decision making related to the environment is made available, in an objective, understandable, timely and effective manner, to the members of the public concerned.

4. States should ensure that due account is taken of the comments of the public in the decision-making process and that the decisions are made public.

5. States should ensure that when a review process is carried out where previously unconsidered environmentally significant issues or circumstances have arisen, the public should be able to participate in any such review process to the extent that circumstances permit.

6. States should consider appropriate ways of ensuring, at an appropriate stage, public input into the preparation of legally binding rules that might have a significant effect on the environment and into the preparation of policies, plans and programmes relating to the environment.

7. States should provide means for capacity-building, including environmental education and awareness-raising, to promote public participation in decision making related to the environment.

Source: Adapted from (UNEP, 2015[36]).

Managing water pollution

Water quality in Viet Nam is deteriorating, a trend that acts as a major constraint on economic growth. Water pollution has the potential to cause annual losses to the economy of up to 4% of GDP if no action is taken (World Bank, 2019[4]). There are five main sources of water pollution. Industrial wastewater is potentially the most highly polluting source due to the amount of chemicals that are difficult to treat (at present only 70% of discharges are treated). Domestic wastewater is the largest contributor in volume (only 12.5% of municipal wastewater is treated). The other three sources are solid waste reaching waterways, untreated wastewater from traditional craft villages, and agriculture and livestock pollution (Cassou et al., 2017[37]).

The existing regulatory framework in Viet Nam makes use of water environment and effluent standards, inspections and penalties as well as effluent charges. While the framework seems sound in principle, limitations have hampered its effectiveness. Limited monitoring capacity has hindered understanding of the full extent of water pollution (ambient quality and pollution sources) and has impeded efforts towards setting adequate standards and enforcement. Human resources for enforcement are inadequate, with on average only eight environmental inspectors per province (World Bank, 2019[4]). The penalty structure does not incentivise changes in behaviour, either because fines are too low or are not collected. Existing wastewater treatment tariffs are too low to achieve cost recovery, and hence do not provide financial incentives for industrial companies to invest in treatment. Finally, agricultural policies that promote cheap fertiliser and pesticides are harming the environment.

In addition to the existing regulatory framework, the government has made significant investments in domestic wastewater treatment plants in major cities; however, underinvestment19 in the sewerage network (particularly in connection to treatment plants) in urban areas has resulted in low domestic wastewater treatment. Programmes have been implemented to promote compliance and investments in water quality monitoring for firms located in industrial zones (Box 7.13).

Box 7.13. Lessons from the Vietnam Industrial Pollution Management Project

The World Bank-financed “Vietnam Industrial Pollution Management” project was created to help the country manage industrial pollution issues by improving compliance with industrial wastewater treatment regulations in four of the country’s most industrialised provinces.

The project helped to shift the culture away from an inspection-driven approach, where the Departments of Natural Resources and the Environment (DONRE) was tasked with detecting incompliance, towards a self-monitoring approach in which industrialised zones were tasked with proving compliance. The old inspection-driven approach was problematic since DONRE made regular announced visits to these zones. Inspectors had to manually collect wastewater samples which could be easily tampered with by managing wastewater discharge flows. The self-monitoring approach involved continuous 24-hour monitoring with online data transferred to provincial authorities. Independent analysis and verification of lab results were used to underpin this continuous monitoring approach. The arrangement provided the best conditions for improving compliance and protecting against wastewater contamination of the river basins.

The approach was piloted by the project in four provinces. Support for the regulatory framework was provided by strengthening monitoring and enforcement, with financing allocated for wastewater treatment investments. The project has the potential to be replicated in other non-project provinces. Even without World Bank-financed support for scale-up, the new regulations and availability of more affordable financing allow for improved compliance with wastewater effluent standards for industrial zones and separate industries. Project implementation also generated lessons in terms of the need to increase enforcement capacity at MONRE and DONRE as well as operational capacity at wastewater treatment plants.

Source: Adapted from (World Bank, 2019[38]).

Strengthen the regulatory and institutional framework for implementation

Viet Nam should consolidate leadership responsibilities for water quality under a single agency to ensure effective supervision. At the same time, the monitoring of water quality and water polluters together must be strengthened and ultimately used for the re-design of the existing regulatory system. Wastewater treatment standards and pollution fees must be reassessed based on the consideration of carrying capacity of receiving water bodies and cost-benefit analysis to avoid excessive capital and operational infrastructure costs. Other compliance assurance strategies should be introduced or scaled up. For example, the VEPF can be scaled up to provide access to finance to SMEs and municipal government agencies (Box 7.14) for technology adoption. Awareness raising, education programmes and public disclosure schemes can also be used to encourage behavioural change. Finally, pilot water quality plans should be prepared in critical river basins to identify the measures needed to improve the status of water quality.

Box 7.14. The Clean Water State Revolving Fund in the United States

The Clean Water State Revolving Fund (CWSRF) is a federal fund established in 1987 to provide financial assistance to a wide range of US water infrastructure projects. Loans were provided to eligible recipients to construct municipal wastewater facilities, control non-point sources of pollution, build decentralised wastewater treatment systems, create green infrastructure projects, protect estuaries and fund water quality projects. The Environmental Protection Agency provided grants to all 50 states to establish a state fund, with states contributing an additional 20% to match the federal grants.

The programme functioned like an infrastructure bank by providing low-interest loans. As money was paid back into the state’s revolving loan fund, the state made new loans to other recipients for high-priority water quality activities.

Since 1988, USD 126 million has been used cumulatively for more than 38 441 assistance agreements covering a wide range of water quality infrastructure projects. In 2017, the CWSRF provided over US$ 7.4 million in funding. The weighted average interest rate for CWSRF loans was below the market interest rate and dropped to 1.4% in that year – a historic low.

Source: Adapted from www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-06/documents/cwsrf_101-033115.pdf and (World Bank, 2019[38]).

Promote effective and sustainable wastewater treatment investments