Reforming the governance of SOEs would contribute significantly to productivity gains. It would moreover help level the playing field and generate equal opportunity for all market actors – private, public and foreign. Viet Nam has made concrete steps forward by creating the Commission for the Management of State Capital (CMSC). Looking ahead, a crucial next milestone is the definition of a transparent state ownership policy, and financial and non-financial performance objectives for all SOEs. The CMSC should moreover be given the power and resources to ensure compliance. Additional important steps include the professionalisation of the management boards of SOEs, increasing transparency of operations and results, and protection of the rights of minority shareholders.

Multi-dimensional Review of Viet Nam

5. Enhancing SOE efficiency in Viet Nam

Abstract

Size and sectoral distribution of state-owned enterprises

State-owned enterprises according to the OECD’s definition include any corporate entity recognised by national law as an enterprise and in which the state exercises ownership – including indirectly as an ultimate beneficiary owner of a majority of the voting share. This definition is somewhat broader those that used in Vietnamese legal traditions which categorise a company as an SOE only if it has the form of a one-member limited liability company with the state as the sole owner.1 The remainder of this report applies the OECD definition, where appropriate subdividing SOEs into wholly state-owned companies and majority-owned companies.

Table 5.1 provides an overview of SOEs owned by the central government, broken down by main sectors of economic activity.2 There are currently close to 2 200 central SOEs (with an additional 1 100 at the subnational level), providing nearly 1 million jobs, and accounting for close to 7% of Viet Nam’s urban employment.3 This is one of the highest – if not the highest – shares of SOEs in total employment among economies surveyed regularly by the OECD (OECD, 2017[1]). Moreover, according to official estimates, SOEs (at all levels of government) contributed close to 30% of total GDP in 2015.

Table 5.1. Sectoral distribution of SOEs by employment and value

|

|

No. of enterprises |

No. of employees |

Value of SOEs as % of GDP (current USD) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Primary sector |

452 |

274 395 |

7.2 |

|

Finance |

36 |

25 336 |

6.8 |

|

Manufacturing |

499 |

224 186 |

2.5 |

|

Wholesale and retail |

349 |

99 754 |

2.5 |

|

Real estate and construction |

333 |

74 854 |

1.7 |

|

Other services |

238 |

39 356 |

1.5 |

|

Transportation and storage |

214 |

97 749 |

1.4 |

|

Utilities |

190 |

67 008 |

1.0 |

|

ICT |

66 |

17 280 |

0.8 |

|

Tourism |

102 |

11 855 |

0.2 |

|

Total |

2 479 |

931 773 |

25.5 |

Note: The value of SOEs is given by the equity value at 31 December 2015. Only enterprises with a non-zero number of workers and classified by a VSIC code are considered. The category “Primary sector” includes agriculture and mining. “Utilities” includes water supply and waste management, as well as electricity and gas provision. “Other services” includes education, entertainment, health, public administration and professional services. ITC stands for Information and Communication Technology. The table include values for both national and subnational SOEs.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on the Viet Nam Enterprise Survey 2016.

An international comparison of the sectoral distribution of SOEs in Viet Nam displays both similarities and discrepancies. As in almost all other countries, there are a large number of economically important SOEs in the public utilities and network industries (e.g. telecommunication, energy, water and transportation). Similarly, the state is also present in the manufacturing industries – although it is worth mentioning that governments that engage in this sector usually justify state ownership on the basis of a need to protect certain “strategic” activities. Widespread Vietnamese ownership (of 446 companies) would seem to go well beyond this.

Viet Nam stands out in international comparisons in terms of strong state ownership in sectors such as agriculture (the “primary sector” in Table 5.1), real estate and construction, and wholesale and retail trade. To a large extent this reflects continued reliance on a Marxist-Leninist economic model, with state ownership of land and overall state responsibility for socially important services such as distribution of goods and provision of residential housing.4 This has implications for the analysis in the remainder of this chapter, as SOEs in Viet Nam are widely perceived as executive agents of the government’s developmental strategies and economic policy plans, rather than individual economic agents whose main objective is the maximisation of long-term earnings. Consequently, the analytical framework usually applied to OECD economies does not necessarily apply. It is commonly assumed that the state should disinvest from activity areas where state ownership is not a prerequisite for efficient resource allocation. However, if as in the case of Viet Nam certain functions are naturally vested in the public sector, the choice may in practice be between allocating them to SOEs and other forms of public sector institutions.

Based on the Viet Nam Enterprise Survey 2016, estimates can be provided of the relative share of SOEs in various sectors of the corporate sector. First and foremost, SOEs are on average much larger than private companies, most of which are small and medium enterprises (SMEs) often with just one owner-employee. Out of Viet Nam’s 422 431 registered companies only 2 479 are owned by central and local governments. However, these publicly owned companies account for 10% of total employment and 16% of the corporate sector’s equity capital.5

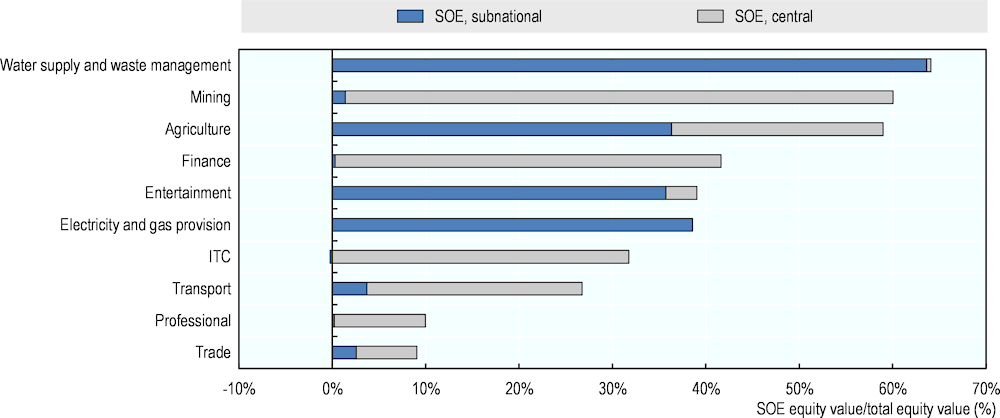

Table 5.1 provides an overview of the percentage of selected economic sectors that consist of state-owned enterprises, broken down by nature of state ownership. In three corporate sectors, the state (central or subnational) accounts for over half of the equity capital, namely water utilities, mining and agriculture. In the financial sector, entertainment industry, as well as in electricity and gas utilities the shares are around 40%. Subnational authorities exercise a large part of the ownership in agriculture, the entertainment industry and, especially, in water and electricity utilities. The national government may or may not hold a share in this subnational SOEs.

Such strong state involvement in the corporate sector creates scope for “crowding out” competing private sector activities, unless the state’s intervention is carefully designed to maintain a level playing field. Many of the sectors appearing in Figure 5.1 include a strong public utility element in the form of the provision of essential services, but these are unlikely to be the only areas of activity of the respective SOEs. Care must be taken to ensure, where possible, a functional separation of public interest services and other activity areas, or at least to maintain separate financial accounting for different activities.

Figure 5.1. Top 10 sectors with state ownership

Note: Only enterprises with a non-zero number of workers and classified by a VSIC code are considered. The figure consider both national and subnational SOEs.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on the Viet Nam Enterprise Survey 2016.

A characteristic of the Vietnamese SOE sector (which is to a large extent shared with China) is the fact that most economically significant SOEs are located within business groups. In the earlier phases of the reform process a number of individual SOEs were merged into larger and financially stronger state general corporations (SGCs). Around the time of Viet Nam’s accession to the WTO many SGS were clustered into giant and highly diversified state economic groups (SEGs). The SEGs were at the time of formation considered as representatives of the “commanding heights” in the economy. They have been likened by researchers to the Korean Chaebols and Japanese Keiretsu, and it has been speculated that they were in fact an expression of a political desire to emulate these countries’ past development paths (Thành, 2014[2]). However, a perhaps unintended consequence of their creation has been their contribution to stifling competition and the prevalence of directed lending within the large state-controlled groups, as discussed further below. There are currently seven SEGs entirely in state ownership and the government is reportedly considering reducing the number to three (Hanoi Times, 2018[3]).

Stock market-listed SOEs

As with a number of other countries, Viet Nam has listed a number of state-owned enterprises on the national stock markets. In the Vietnamese case, the act of undertaking an initial public offering of shares in an SOE can be seen as a logical extension of the process of “equitisation” (described below), at least where large companies are concerned. But as is the case in other jurisdictions, motivations also include hoped-for improvements in the operating conditions of these enterprises. According to an OECD study, most countries engaged in listing SOEs expect the companies to enjoy better access to financing going forward and to maintain higher standards of transparency and disclosure as a consequence of the stock market listing and maintenance rules (Hanoi Times, 2018[3]). In a smaller subset of countries, the process of listing SOEs went hand-in-hand with an objective to enhance their commercial orientation or remove them further from state influence.

Among the listed companies in Viet Nam are 29 large SOEs with majority state ownership. An additional 20 companies have the state as a significant minority shareholder (with a stake exceeding 10% of voting shares). In combination, this accounts for 40% of the total market capitalisation. As shown in Table 5.2, the largest SOEs include Hanoi Beer, those belonging to the financial sector and the PetroVietnam hydrocarbons group. The largest listed company with a minority state shareholding is the highly regarded Viet Nam Dairy Products (with a market capitalisation of USD 9.0 billion) in which the state retains 37.9% of the shares.

Table 5.2. Ten largest listed companies with majority state ownership

|

Companies |

State ownership share in % |

Market capitalisation (USD million) |

|---|---|---|

|

Bao Viet Securities JSC |

59.9 |

2 685 |

|

Hanoi Beer Alcohol And Beverage JSC |

81.8 |

808 |

|

Joint Stock Commercial Bank for Foreign Trade of Viet Nam |

77.3 |

8 300 |

|

Joint Stock Commercial Bank for Investment and Development of Vietnam |

95.5 |

5 071 |

|

PetroVietnam Fertilizer and Chemicals Corp |

59.6 |

376 |

|

PetroVietnam Gas Joint Stock Corp |

96.0 |

7 147 |

|

PetroVietnam Power Nhon Trach 2 JSC |

59.4 |

305 |

|

PetroVietnam Technical Services Corp |

53.3 |

363 |

|

Vietnam Joint Stock Commercial Bank for Industry and Trade |

69.9 |

3 093 |

|

Viglacera Corp JSC |

55.8 |

352 |

Note: Based on a sample of 278 listed companies for which ownership data are available. They represent 97% of the total market capitalisation in Vietnamese stock markets.

Source: Thomson Factsheet.

Occasional controversy has arisen over the treatment of minority investors in listed SOEs (Olberg, 2014[4]). According to the World Bank’s ease-of-doing-business index, in 2018 Viet Nam scored lower than Malaysia, Indonesia and OECD high-income countries in terms of protecting minority investors. The issue of protecting shareholders from abusive related party transactions applies to all listed companies in Viet Nam regardless of ownership (Robinett, Benedetta and Nguyet Anh, 2013[5]). In particular, the state’s continued holding of a relatively large share of stocks of listed companies even after the equitisation process makes it difficult to delineate ownership from management of firms. Management decisions of many equitised firms are still influenced by the state, marginalising interests of minority investors and shareholders. In addition, complaints from non-state shareholders have been voiced over the continued use by the state of listed SOEs in pursuit of public policy objectives and other non-commercial purposes. Internationally agreed good practices imply that this should only be done when the minority shareholders have been fully informed of the SOEs’ non-commercial objectives at the time of their investment (OECD, 2015[6]).

Ownership arrangements

The state ownership function in Viet Nam is traditionally, and at the time of preparing this report, largely decentralised, with a number of government agencies exercising rights on behalf of the state. These include the Ministry of Industry and Trade, the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of National Defence, the Ministry of Transport, and the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development. At the subnational level ownership is typically exercised by the various regional People’s Committees.

The government established the Commission for Management of State Capital in Enterprises (CMSC) in February 2018. The Commission, which became operational in September 2018 under Decree No. 131/2018/ND-CP dated 29 September 2018, is an autonomous body under the government. It exercises full ownership rights in a number of enterprises in which the state owns 100% of the charter capital, and acts as the representative of state capital in joint stock and limited liability companies with more than one shareholder. The CMSC is currently charged with exercising the state’s ownership role in 19 of the country’s state-owned entities – many of which are in reality Corporate Groups or the even larger State Enterprise Groups (Box 5.1). By one estimate from the Ministry of Finance of Viet Nam, its portfolio amounts to around 200 individual companies and the total value of state equity in these companies is over VSN 1 000 trillion (USD 43 million).

Box 5.1. List of 19 state economic groups and corporations under the management of the Commission for Management of State Capital (CMSC)

State Capital Investment Corporation (SCIC)

Viet Nam Oil and Gas Group (PVN)

Viet Nam Electricity (EVN)

Viet Nam National Petroleum Group (Petrolimex)

Viet Nam National Chemical Group (VINACHEM)

Viet Nam Rubber Group (VRG)

Viet Nam National Coal-Mineral Industries Holding Corporation Limited (VINACOMIN)

Viet Nam Post and Telecommunications Group (VNPT)

Viet Nam Mobile Telecom Services One Member Limited Liability (MobiFone)

Viet Nam National Tobacco Corporation (VINATAB)

Vietnam Airlines

Viet Nam National Shipping Lines (VINALINES)

Viet Nam Railways (VNR)

Viet Nam Expressway Corporation (VEC)

Airports Corporation of Viet Nam (ACV)

Viet Nam National Coffee Corporation (VINACAFE)

Viet Nam Southern Food Corporation (VINAFOOD 2)

Viet Nam Northern Food Corporation (VINAFOOD 1)

Viet Nam Forest Corporation (VINAFOR)

Note: Other enterprises could be added, if decided by the Prime Minister.

Source: Questionnaire responses from the Ministry of Finance of Viet Nam.

The CMSC has officially existed since February 2018, but is still being built up to full operational capacity. It plans to operate with a staff of 150 employees, of which 70 are already employed. As of now there are nine assisting agencies, including the Ministry of Industry and Trade, the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, the Ministry of Energy, and the Ministry of Technology and Infrastructure, among others. The line ministries’ role in overseeing CMSC’s companies is limited to sectoral regulation and policy making. However, taking into consideration the Vietnamese economic model, according to which SOEs are important vehicles for policy implementation, these powers continue to confer a considerable degree of operational control over many of the SOEs. It still remains to be seen whether or not the CMSC will directly interfere with the managerial and business operations of those corporations.

The State Capital Investment Corporation (SCIC) was established in 2005 under Decision No. 151/2005/QD-TTg of the Prime Minister to enhance efficiency in the use of state capital, with a view to separating the functions of management from state ownership of SOEs by line ministries and provincial-level People’s Committees. Its primary objectives were to represent the interest of state capital in enterprises and invest in key sectors and essential industries with a view to strengthening the role of the state sector, while respecting market rules (OECD, 2019[7]). As such, SCIC has been mostly active as a shareholder in equitised and partly privatised SOEs, and as of December 2018, it managed a large portfolio of 142 enterprises that are operating in various sectors, including finance, energy, manufacturing, telecommunications, transportation, consumer products, health care and information technology. However, due to the unwillingness of line ministries to transfer state-owned capital in the SOEs to the SCIC, the SCIC-centred state ownership model has turned out to be inefficient, and the SCIC is now one of 19 state economic groups and corporations overseen by the newly established CMSC.

Performance of SOEs relative to private firms: Is there a problem?

Inefficiencies arising from the predominance of SOEs

The evidence of corporate inefficiency in Viet Nam is not limited to the state-owned sector. According to comparative studies, Viet Nam’s corporate sector has less innovation capacity and is less technologically advanced than comparable Asian economies, particularly in the case of manufacturing. (Conversely, banks effectively seem to have established themselves as “technology leaders” in the economy.) SOEs actually have advantages in this respect, mostly due to economies of scale reflecting their dominant position in a number of market segments.

An apparent paradox arises from published data about the performance of Vietnamese SOEs and the predominant public and academic discourse. The consensus view is that SOEs are generally inefficient; however, macroeconomic data from the Viet Nam Enterprise Survey 2016 has consistently shown higher rates of return in state-owned enterprises than in the domestic private corporate sector.6 According to information gathered from Vietnamese institutions in preparation for this report, there could be different reasons for this. First, even relatively inefficient SOEs may be profitable if they benefit from subsidies and favoured treatment (see the following section for more detail). Second, the published financial accounts of SOEs are considered unreliable since the political context incentivises management to inflate performance data. Third, the financial earnings of SOEs appear to be highly concentrated. In some years, just three SOEs (in the public utilities and hydrocarbons sectors) accounted for half of the net earnings of Viet Nam’s state-owned sector. Moreover, inefficiency varies across types of SOEs. SOEs controlled by the central government have higher return on equity than local SOEs, most of which are not profitable.

A more relevant measure than profitability per se is the total factor productivity of different categories of enterprises. Two recent studies of the performance of SOEs and private firms in the manufacturing sector found significantly higher productivity among private firms, as well as increasing productivity among SOEs post-privatisation (Thanh Hong, 2016[8]) and (Baccini, Impullitti and Malesky, 2019[9]). The latter further explored the link between profitability and productivity and found that “SOEs, despite being corporatised and drastically reformed, [are] more profitable and less productive than private firms”. Moreover, the study found evidence that, probably in consequence of their profitability, less SOEs were less likely to exit the market than their more productive private competitor – an example of crowding out directly relevant to the discussion of competitive neutrality in the following section.

This situation leads to the misallocation of resources, including finance. Whether or not (small) private firms are unfairly discriminated against in their access to capital, the overall outcome of the Vietnamese ownership structure is one where state-owned firms appropriate the lion’s share of credits in the economy. According to the Viet Nam Enterprise Survey 2016, the average leverage (total liabilities divided by equity) among enterprises majority owned by the state currently stands at 2.4, whereas among private firms the level is substantially smaller at 1.5. A “quick fix” toward redressing this imbalance (in addition to a longer term review of the state’s role in the commercial economy) would involve hardening the budget constraints facing SOEs as well-tightened controls to ensure that large state-controlled groups do not diversify into rent-seeking business opportunities outside their sectoral scope.

Concerns about a level playing field

A recurrent concern arises when SOEs co-exist with private companies in competitive markets – or where SOEs have a predominant position in markets that could, given existing rules and regulations, be contested by private sector competitors. The situation where no market participant is advantaged (or disadvantaged) due to its ownership is called “competitive neutrality” and is commonly referred to as maintaining a level playing field between SOEs and private firms. A 2012 report by the OECD (OECD, 2012[10]) established the main elements in maintaining competitive neutrality. These are summarised in Box 5.2.

Box 5.2. Main elements of competitive neutrality

Streamlining the organisational form of government businesses

In regulated sectors, particularly public utilities and network industries and banking, there should be a separation of regulatory functions into entities distinct from those engaged in commercial operations.

Identifying the direct costs of any given function

Cost identification is essential to identifying where the public sector bears additional costs or where the SOE benefits from its ownership. In the absence of this, implicit subsidisation is a very likely prospect.

Achieving commercial rates of return

SOEs should be operated on the basis that they should earn a profit and pay a commercial level of return (e.g. in the form of a divided) to the government on the equity capital allocated to the commercial operations.

Tax neutrality

SOEs should ideally be subject to the same tax obligations as any other corporate entity or, where this is not feasible, should be required to make other compensatory payments in order to maintain a level playing field.

Regulatory neutrality

SOEs should be required to meet the same regulatory requirements as private sector entities and should not enjoy any immunities or exceptions from laws.

Debt neutrality and outright subsidies

SOEs should not receive concessionary financing from state-owned financial entities or through trade credits from other SOEs. Nor should they be allowed to benefit from lower market interest rates arising from a perceived government guarantee for their debts.

Public procurement

SOEs should not be required to provide goods and services to the government below market prices. Conversely, the government should exhibit no preference to buy from its own SOEs. Public procurement should be the same regardless of ownership.

Source: (OECD, 2012[10]).

Evidence of an uneven playing field, in the form of departures from the good practices outlined in Box 5.2, abound. For instance, (OECD, 2018[11]) observed that SOEs are prominent in many markets that exhibit oligopolistic characteristics. The SOEs that operate in these markets are often effectively controlled by line ministries responsible for policy and regulation in the same markets. For example, the telecommunications sector has three big players, all of which are SOEs. Two are owned by the Ministry of Communications and one is owned by the Ministry for Defence. Similarly, the country’s largest banks are also state-owned and in terms of corporate governance are almost treated as affiliates of the central bank. At the same time, the sprawling portfolio of SOEs in Viet Nam means that state-owned firms are also active in sectors (e.g. hotels, breweries, construction) where there is vigorous competition with private providers.

Where line ministries are both responsible for regulating a market and owning shares in significant operators it often leads to actual or perceived favouritism. Favouritism can arise where an SOE explicitly requests favourable treatment or where the shareholding ministry – deliberately or implicitly – behaves in the SOE’s interest. For example, allegations that the state-owned Vietnam Airlines benefits from unfair advantages granted by its owner-regulators are widespread. The World Bank notes that “at airports the slot allocation policy is not competitive. State-owned Vietnam Airlines has grandfathered rights on international routes, while charter flight rights on domestic routes are granted case by case” (World Bank, 2016[12]). Members of the travelling public also reportedly perceive the airline has having advantages due to its ownership which results in more convenient scheduling and better timeliness for travellers than its direct competitors.

Frequently cited examples of favourable treatment of SOEs relate to preferential access to finance, land usage rights and direct subsidies7 from state budgets (Van Thang and Freeman, 2009[13]). Vietnamese SOEs are apparently able to borrow from commercial banks on easy terms, either because the lenders are themselves state-owned or because a state guarantee for the debtor is perceived. Some caution is called for, however. Private companies, as mentioned, are significantly smaller on average than SOEs and face a higher default risk, so one would expect SOEs to be able to borrow on easier terms. Nevertheless, the issue seems to run deeper than this. Credits from state-owned financial institutions to SOEs require little or no disclosure by the borrower and are largely unsupervised by the relevant financial supervisory agencies. In consequence, the share of loans to SOEs that are non-performing is not known (OECD, 2016[14]).

On the issue of land use, all land in Viet Nam is state owned, but land rights can be granted to firms and individuals. An SOE wishing to expand will generally be provided with land free of charge. Foreign-invested companies in prioritised sectors may enjoy similar privileges. Conversely, according to discussions with private sector representatives during the preparation of this report, domestic private enterprises have no access to such favourable treatment. Key to this is the reassignment of zoning from agricultural land to industrial use, a regulatory function mostly exercised by subnational authorities. In consequence, this issue tends to come to the forefront where subnational SOEs, or other SOEs that are seen as important providers of jobs and/or patronage in defined geographic areas, are concerned. If a level playing field is to be obtained, the public sector needs to discontinue the practice of providing free land to SOEs, and private firms should have recourse to zoning reassignment when they identify willing sellers of land.

At the same time, according to members of the Vietnamese business community interviewed for this report, there have been some recent improvements in the Vietnamese business environment, mostly driven by better and clearer laws and regulations implemented by government. In theory, authorities should no longer discriminate between companies based on ownership. However, this principle is apparently not implemented consistently. In addition to the issues with finance and land usage, a more general concern widely voiced by business representatives relates to the fact that legal texts, government strategies and policy guidelines, as mentioned earlier, are often developed with a view to implementing development strategy goals. In practice, this means that they are to a large extent directed at the incumbent SOEs. The private sector is thus recognised as an important – but not essential – element in driving economic growth.

Finally, the unequal treatment of SOEs also risks aggravating regional disparities in Viet Nam. According to the Provincial Competitiveness Index, 41% of entrepreneurs believe that provinces privilege SOEs, creating difficulties for private firms. Provinces with a high density of SOEs provide less credit to private firms and require more time to issue land use rights certificates than other provinces (Nguyen, Le and Freeman, 2006[15]; Malesky, Phan Tuan and Pham Ngoc, 2017[16]) Easier access by SOEs to credit, land and export quotas in the garment and textile sector reduces the profitability and viability of private firms (Nguyen, Le and Bryant, 2013[17]).

Experience gathered from recent and ongoing reform

The future role of SOEs in the Vietnamese economy is increasingly seen by policy makers in terms of their linkages with the emerging private enterprise sector. In practice, such linkages often remain somewhat limited – or, where they exist, somewhat lopsided – due to the dominance of SOEs in a number of sectors, including, as mentioned earlier, the extractive industries, electricity, telecommunications and finance. Further reform is foreseen mostly through equitisation of more companies. According to this thinking, in the longer term SOEs will retain their dominant position only in sectors related directly to defence or otherwise deemed “strategic”. All others should in principle be opened up to foreign participation and/or competition.

Is divestment the solution – or part of the solution?

Opponents of privatisation frequently invoke the example of other South and East Asian economies such as Singapore, Korea and Chinese Taipei, where the state has played a leading role in evolving market economies, and remained in the driving seat well beyond mid-income levels.8 However, such “statism” is at risk of capture by incumbent elites and has therefore worked best in countries under such external pressures that the elites chose to accept a strong state. In the case of Viet Nam the situation is further complicated by the fact that individuals with economic clout are mostly associated with the existent state power structures, leading to the development of multiple centres of power through what some observers have termed “commercialisation of the state” (Pincus, 2015[18]).

Consistent with the OECD Guidelines (Box 5.3), the obvious solution is for the state to divest from economic activities where there is no clear rationale for public sector involvement. Indeed, since the Ðổi Mới reforms, Viet Nam has embarked on an ambitious equitisation process, which has however slowed down in the past two years. Based on Official Letter No. 991/TTg-DMDN (dated July 2017), Decision No. 26/2019/QD-TTg of the Prime Minister (dated August 2019) and Decision No. 1232/2017/QDTTg (dated August 2017), the government aims to equitise 127 SOEs and divest 406 SOEs between 2017 and 2020. According to this plan there would remain only 103 wholly state-owned enterprises in Viet Nam by the end of 2020.

However, by end of 2019, only 36 (out of 127) SOEs were equitised and only 100 (out of 406) divested. According to the Ministry of Finance, the government will continue to divest 41 SOEs from the 2018 list and 18 new ones in 2019. However, by the end of March 2019, no SOE equitisation or divestment plans had been approved. In response, the Vietnamese public and press has in recent years repeatedly criticised the equitisation process, which is perceived as too slow and constantly behind schedule.

The Ministry of Planning and Investment has confirmed that currently only around 30% of planned equitisations proceed as scheduled. According to the Ministry, this reflects a number of factors. First, many of the initial deadlines for equitisation may, for political or other reasons, have been unrealistically tight. Second, uncertainties over land ownership rights, the correct book value of SOEs and procedural issues have been a source of delays. Third, the reluctance of would-be strategic investors has been greater than expected, reflecting the combination of continued public policy objectives in the equitised SOEs and the fact that the state generally insisted on retaining a stake exceeding 50%. Fourth, administrative processes in the state agencies overseeing SOEs have been plagued by inertia and slow decision making.

According to outside observers, the equitisation process also may face further challenges. For example, investors can rarely access information about companies that are about to begin equitisation. This is because SOEs can be equitised without listing on a stock exchange, which would otherwise impose significant disclosure requirements (OECD, 2018[19]). According to the State Auditor General, it is indeed difficult to obtain an independent evaluation of the assets of certain SOEs, namely of land and brand.9

This lends itself to the tentative conclusion that, on the one hand, there is a need to rethink the rationale for state ownership of enterprises and retain (majority) ownership only where a rationale is clearly present. On the other hand, timing and sequencing is an issue. Rushed privatisation can provide negative outcomes in terms of fiscal proceeds to the state and subsequent market efficiency. For example, OECD area experiences include a number of examples of SOEs being privatised while still holding significant monopoly powers – in some cases apparently in a deliberate attempt to boost privatisation revenues. This is not advisable. SOEs should generally not be privatised until competition has been introduced in their sectors of operation or, where this is not feasible, adequate regulatory systems have been put in place.

Institutional changes in the public administration and the SOE operating environment

As mentioned above, in late 2018, the government partially centralised the state ownership function, through the creation of a ministerial agency with responsibility for SOE board nomination as well as a number of oversight powers. In accordance with the Law on Investment and Business for State Capital, the government created a special agency named the Committee for Management of State Capital (CMSC) responsible for managing state capital and assets. As of now, the CMSC manages the 19 biggest state-owned economic groups and corporations operating in sectors such as oil, gas, coal and minerals, with a total state capital of nearly USD 45 million. However, a considerable degree of state ownership and operational control is still exercised by line ministries and provincial committees, who are simultaneously responsible for sectoral policy and regulation in the relevant markets.

Although the government has made some significant progress in terms of improving the legal regulatory framework on SOE governance, ensuring full compliance by individual firms remains the most significant challenge. Reform of the corporate governance framework is ongoing and revision of both the Enterprises Law and Securities Law is planned, according to the Vietnamese authorities, to ensure closer alignment with the OECD’s SOE Guidelines. As of now, SOEs are subject to a number of laws, decrees, decisions and circulars that contribute to the SOE reform agenda. The major relevant legal documents are summarised in Table 5.3.

Table 5.3. Main laws and regulations with a bearing on SOEs

|

Law |

Goal |

|---|---|

|

Law on Enterprises, amended in 2014 |

The law defines the requirements for being designated an SOEs (Article 4), outlines the types of SOEs, and provides information related to the management body, the appointment and composition of boards of directors and disclosure requirements (Chapter IV). This new regulation is considered a key element in the country’s SOE corporate governance framework. |

|

Law on the Management and Use of State Capital Invested in Production and Business 2014 |

The law specifies the powers and responsibilities of state representatives in enterprises with state ownership below 100% and regulates the management and investment of state capital. |

|

Decree No. 97/2015/ND-CP dated 19 October 2015 and the Decree No. 106/2015/ND-CP dated 23 October 2015 |

These decrees specify the objectives and mandate of SOE boards of directors. |

|

Prime Minister’s Decision No. 929/QD-TTg dated 17 July 2012 |

The decision approves the Scheme for Restructuring of SOEs, focusing on state-owned economic groups and corporations in the period 2011-2015. |

|

Decree No. 99/2012/ND-CP dated 15 November 2012 on assignment, decentralisation of the implementation of the rights, responsibilities and obligations of state owner for the SOEs and State Capital Invested in the Enterprises |

This decree clarifies the intended rights and responsibilities of managers of state capital in different forms of enterprises and accelerates the move towards more autonomy in the management of SOEs. |

|

Government Resolution No. 01/NQ-CP dated 7 January 2013 |

This resolution details major solutions guiding and directing the realisation of the socio-economic development plan and state budget estimate in 2013 refers to PM Decision No. 929/QD-TTg and Decree No. 99/2012/ND-CP. |

|

Socioeconomic Development Strategy (SEDS), 2011-2020 |

This government strategy recognises the importance of SOE reform, prioritising faster rates of equitisation and privatisation. |

Recent and ongoing reform in Viet Nam has been discussed in the context of the OECD Asia Network on Corporate Governance of State-Owned Enterprises. The remainder of this section provides some highlights of these reforms, based on information submitted to the network by the Vietnamese authorities.

Disclosure requirements and practices

At the enterprise level. The disclosure requirements placed on SOEs in Viet Nam are outlined in Decree No. 81/2015/ND-CP (dated 18 September 2015), according to which SOEs are required to present the following information on their website and at shareholder meetings: (i) objectives and their fulfilment; (ii) financial and operating results; (iii) governance, ownership and voting structure of the enterprise; (iv) five-year strategy for business activity; annual plans for business and investment activities; (v) report on restructuring processes, annual management reports; financial guarantees; (vi) material transactions with related entities; (vii) and annual salary reports and annual income reports including the remuneration of board members and key executives. SOEs are also required to complete and publish six-month and annual audited financial statements on their websites, prior to sending them to the CMSC. The deadline for the six-month report is the end of every third quarter and the deadline for the annual report is the second quarter of the following year. According to the Vietnamese government, at the end of 2018, only 70% of SOEs had fully disclosed these items in accordance with the regulation.

At the level of the state. Decree No. 81/2015/ND-CP states clearly that SOEs should submit periodic aggregate reports every 6 and 12 months. The Ministry of Planning and Investment produces an annual aggregate report on SOEs under instruction from the Prime Minister. The report is not disclosed publicly but is submitted by the Ministry of Planning and Investment to the Prime Minister and the Cabinet, following which the Prime Minister presents the report to Parliament during the mid-year sessions. The contents of the aggregate report include a general overview of business operations and performance, but contain no detailed assessments of individual SOEs or the portfolio of each SOE. The report also includes information on SOEs’ contributions to the economy (e.g. contribution to the national budget and export-import turnover), the overall value and financial performance of SOEs, SOE business scale, total employment in SOEs and information on board member remuneration. The report is not translated into other languages and has not yet been made available online. The state also has not put in place a dedicated website to publish information on individual SOEs.

It appears that, in practice, SOEs do not consistently comply with the state’s disclosure requirements. There are currently no penalties in cases of non-compliance and the reports are not published in a timely manner.

Performance evaluation and reporting

Evaluation. By law, the Ministry of Finance is in charge of monitoring and supervising the performance evaluation of SOEs, while its Agency for Corporate Finance manages the performance evaluation system. Performance evaluations are administered on an annual basis, following a three-step-procedure: (i) a self-evaluation by the SOE; (ii) an evaluation by a line ministry or provincial government, the SCIC or the SEG, which is in charge of state ownership in the SOE; and (iii) an evaluation by the Agency for Corporate Finance. Evaluation reports developed by the concerned ministries and provincial governments, as well as the appraisal report prepared by the Ministry of Finance, rely heavily on self-evaluation by SOEs. No independent evaluation team is involved in the assessments.

The performance evaluation system includes two components: (i) an evaluation of SOE performance and (ii) an evaluation of CEO performance. The evaluation of SOE performance uses several indicators to measure primarily financial efficiency, but also two indicators that seek to measure the contribution of SOEs to society.

Reporting. In Viet Nam, evaluations relate to the previous year’s performance. The evaluation of CEOs emphasises their management efficiency using the following criteria: (i) accomplishment of the return-on-equity target assigned by the state; (ii) result of the evaluation of the SOE; and (iii) other indicators to evaluate the performance of civil servants guided by the Ministry of Interior.

Line ministries and provincial governments as well as SEGs and the SCIC produce semi-annual reports and an annual report entitled the “Financial Supervision Report” for every SOE. Viet Nam does have guidelines with mandatory performance information for the annual report - which provides details on the return on equity and the return on assets, for example. However, the semi-annual and annual reports are generally not publicly disclosed.

Measures related to boards of directors of SOEs

Ownership entities play a more direct role in strategic management, as well as in the appointment of the CEO, succession planning, executive remuneration and incentive schemes. According to internationally accepted good practices, most of these responsibilities should be exercised by the board.

The government has established several notable policies to enhance the role of board of directors of SOEs, including Decree No. 97/2015/ND-CP dated 19 October 2015 and Decree No. 106/2015/ND-CP dated 23 October 2015. According to these Decrees, the objectives of SOE boards of directors are defined in charters of economic groups issued by the Prime Minister as well as charters of corporations and enterprises issued by line ministers or the chair of provincial committees. All charters state that SOE boards of directors or supervisory boards should be granted full responsibility for company’s performance and the autonomy to define strategies for the company in accordance with the objectives defined by the government. The Decrees also state that if a board member is found to have been unduly influenced by outside person(s) or institution(s), the public authorities may implement and apply adequate disciplinary measurement. Up to 80% of the SOE board can be made up of independent or non-executive directors. In addition, the CEO of an SOE cannot at the same time serve as chair of the board.

The Decrees further provide guidelines and regulations on board nomination criteria and an official nomination and appointment procedure. Specialty and management skills are a prerequisite for board member nomination and the board is responsible for identifying its skills needs and communicating them to the relevant decision makers. The Prime Minister decides and promulgates general qualification criteria and the line ministries and provincial committees issue detailed instructions regarding SOE business characteristics.

In practice, nomination processes depend on the size and significance of the SOEs. In the largest seven SOE groups, the president is appointed directly by the Prime Minister, while the CMSC is charged with appointing the executive management. In other non-financial SOEs, the board/management is appointed by the CMSC or the ownership ministries. All potential applicants should be suggested by the SOE boards and nominated by state authorities. In shareholder meetings, applicants who are nominated by ministers should be voted to SOE board. However, when undertaking restructuring processes or in the absence of applicants, the Prime Minister, other ministers or relevant authorities are authorised to undertake a direct appointment to the board. When state authorities nominate a public official to the SOE board, he or she may no longer act as an official. SOE board vacancies are not widely advertised and, as far as has been established by the studies conducted for this report, not particularly contested.

Viet Nam formally requests SOE boards to carry out annual evaluations of their performance. However, audit bodies have no role in board evaluations. Viet Nam has established a process whereby the results of the evaluation process can actually influence the nomination process by identifying necessary competencies and board member profiles, according to the questionnaire responses. Board members are required to send their self-evaluation to the line ministers who are charged with nomination and appointment. The evaluation results play an important role in re-nomination or discipline measurement.

The road ahead: Reforms consistent with internationally agreed good practices

According to a recent World Bank report, “The state-owned enterprises and commercial banks continue to inhale too much oxygen out of the business environment, undermining economy-wide efficiency and crowding out the productive parts of the private sector” (World Bank, 2016[12]). The state also arguably wields exceeding influence in allocating land and capital, giving rise not only to opportunities for corruption by handing over arbitrary power to officials, but also to economy-wide inefficiencies. In the lead-up to the Socio-Economic Development Strategy for 2021-2030, adjusting the role of the state to support a competitive private sector-led market economy remains a major challenge and opportunity. And while global integration has advanced well, with Viet Nam embedding itself in GVCs, the benefits are constrained by the absence of links with domestic firms.

Concerning the future of the sector, the medium-term outlook is for fuller corporatisation of SOEs. The 2015 Law on Government Organisation foresees the conversion of all SOEs into joint stock companies with open shareholding by 2030. Government officials interviewed for this report predict that at the end of this period, 100% owned SOEs will remain only in the public utilities, national security and high-technology sectors.

Remaining challenges can be addressed mostly by reforming the Vietnamese state-owned sector according to internationally agreed good practices. According to the CMSC, the two key priorities for further reform at the enterprise level will be: (i) strengthening compliance with applicable laws and regulations, and raising standards of corporate transparency; and (ii) enhancing and professionalising SOE corporate governance – in line with the OECD Guidelines on Corporate Governance of State-Owned Enterprises (for an overview, see Box 5.3).

Box 5.3. OECD Guidelines on Corporate Governance of State-Owned Enterprises

I. Rationales for state ownership

The state exercises the ownership of SOEs in the interest of the general public. It should carefully evaluate and disclose the objectives that justify state ownership and subject these to a recurrent review.

II. The state’s role as an owner

The state should act as an informed and active owner, ensuring that the governance of SOEs is carried out in a transparent and accountable manner, with a high degree of professionalism and effectiveness.

III. State-owned enterprises in the marketplace

Consistent with the rationale for state ownership, the legal and regulatory framework for SOEs should ensure a level playing field and fair competition in the marketplace when SOEs undertake economic activities.

IV. Equitable treatment of shareholders and other investors

Where SOEs are listed or otherwise include non-state investors among their owners, the state and the enterprises should recognise the rights of all shareholders and ensure shareholders’ equitable treatment and access to corporate information.

V. Stakeholder relations and responsible business

The state ownership policy should fully recognise SOEs’ responsibilities towards stakeholders and request that SOEs report on their relations with stakeholders. It should make clear any expectations that the state has in respect of responsible business conduct by SOEs.

VI. Disclosure and transparency

SOEs should observe high standards of transparency and be subject to the same high-quality accounting, disclosure, compliance and auditing standards as listed companies.

VII. The responsibilities of the boards of directors of state-owned enterprises

The boards of SOEs should have the necessary authority, competencies and objectivity to carry out their functions of strategic guidance and monitoring of management. They should act with integrity and be held accountable for their actions.

Source: (OECD, 2015[6]).

A simple estimation based on experiences in China and European transition economies would suggest that Viet Nam could gain at least 2.5% of GDP per year from reform in accordance with best practices. The consensus in the academic literature based on various country experiences is that SOEs, on average, operate with 15% lower productivity than private companies in similar circumstances. This is probably an overestimate, reflecting both actual inefficiencies in SOEs and the fact that they tend to be burdened with undisclosed public policy objectives that private competitors do not have to contend with. Assuming that the two factors each contribute around half of the discrepancy, full implementation of best practices would raise the average SOE’s output and value-added by around 7.5%. In Viet Nam, SOEs account for about 33% of GDP. A full implementation of SOE reform in accordance with best practices would hence contribute an economic improvement of 33% x 7.5% = 2.5% of GDP. In other words, failing to implement the recommended reform implies that Viet Nam’s national GDP every year is 2.5% lower than it could be.

These are two key features of the OECD’s “SOE governance model”. The first is a separation of powers with appropriate – and clearly delineated – authority vested in the state as a whole, specialised state ownership unit(s), boards of directors and corporate managers. The source of many SOE-related corporate governance failures in the past has derived from decisions made at an inappropriate level of the “decision chain”. The second is the need to maintain high standards of transparency and disclosure, particularly when the rationale for continued state ownership is the pursuit of public policy priorities via these enterprises (OECD, 2010[20]). There is nothing necessarily odious about using SOEs for non-commercial purposes, but public, minority investors in the SOEs as well as commercial competitors, need to be continuously well informed of what is being done “in the public interest”.

The Vietnamese reality departs in some important respects from this ideal picture. For instance, the absence of a formal state ownership policy, the respective importance of SOEs’ commercial and non-commercial objectives, and the performance of SOEs cannot be effectively monitored and assessed. At the same time, while reporting standards of individual SOEs and some categories of SOEs have improved, the absence of publicly available aggregate public reporting on SOEs (beyond the publication of individual SOEs’ financial statements and annual reports) on a whole-of-government basis worsens existing gaps in the accountability landscape.

A decidedly weak point is the autonomy of corporate boards and executive managers. Boards of directors, when they are in place, are not sufficiently equipped – due to limitations in their size, independence and responsibilities – to accomplish their essential strategy-setting and corporate oversight roles. Top management is still often closely linked to ministries and other state bodies, or is frequently bypassed by the government, for instance in the case of direct appointment of CEOs by policy makers.

Finally, several elements distort the level playing field between SOEs and (actual or potential) private competitors, including inter alia: weak corporatisation of commercially oriented state enterprises and state-owned commercial banks; shortcomings in the applicability of public-procurement rules to SOEs as procurers; complicated and non-transparent processes for obtaining approval of land use plans/auditing of companies prior to equitisation; and difficulties of access for strategic investors to quality information and limited room for foreign holdings in the equitised SOEs. Based on the OECD consensus, the following eight areas of SOE reform (in addition to the continued equitisation and divestment of SOEs where state ownership is no longer warranted) need to be considered.

Empower the state co-ordination unit

Perhaps the biggest question mark over the future of Viet Nam’s ownership and governance of SOEs relates to the role of the CMSC. Will this newly created institution become (as in several other countries) just another state co-ordination agency with limited capacity to stand up to powerful line ministries, or will it be able and empowered to exercise fully the state’s ownership rights?

The CMSC should to the maximum extent possible ensure that businesses are structured and managed in a profit making, commercial manner. The CMSC should have sufficient resources – with finances, staff and institutional authority – to effectively carry out its functions in co-operation with other government agencies, and to monitor the compliance of SOEs with governance and disclosure standards including public reporting. It should also play a role in nominations to the boards of SOEs, either by recommending candidates to the ownership ministries or by checking their selections, thus contributing to the creation of professional councils/boards modelled on good practice. In this context, the government can benchmark good practices by other countries which have introduced state-ownership co-ordination functions (Box 5.4). Ultimately, direct ownership rights of the CMSC could be expanded to most or all of the national portfolio of SOEs.

Box 5.4. The mandate of the Governance Coordination Centre in Lithuania

The Governance Coordination Centre (GCC) of Lithuania was established as an authority designated to monitor and analyse implementation of the Ownership Guidelines by state ownership entities. Its mandate is as follows:

Receive, analyse and summarise the information disclosed by State-owned enterprises, including an enterprise’s set of financial statements, audit findings and audit reports, annual and interim reports of State-owned companies, annual and interim activity statements of State enterprises, as well as actions in submitting sets of financial statements, annual reports, activity statements and other information to the relevant authorities, and make a public statement on compliance with the provisions of the Guidelines for ensuring transparency of the activities of State-owned enterprises, approved by Resolution 1052 of the Government of the Republic of Lithuania of 14 July 2010 (Official Gazette, 2010, No. 88-4637) (hereinafter referred to as “the Transparency Guidelines”), and present its evaluations and summaries along with conclusions and proposals to the Government of the Republic of Lithuania (hereinafter referred to as “the Government”) and, where appropriate, to the Ministry of Economy and the authority representing the State;

Monitor and analyse the financial and non-financial performance indicators of State-owned enterprises and present the Government and the authority representing the State with proposals for the improvement of the performance efficiency of the State-owned enterprise;

Prepare proposals to the Government and the Ministry of Economy regarding the improvement of the governance policy for State-owned enterprises;

Summarise the governance practices of State-owned enterprises, develop methodological recommendations on the governance of State-owned enterprises and present them to the authorities representing the State;

Perform the monitoring and analysis of the application of the Procedure and submit related recommendations to the Government;

Provide technical service to the authority representing the State and the selection committee when they carry out their functions in relation to the selection and appointment of candidates for membership in the organs of State-owned enterprises;

At the request of the authority representing the State, present its opinion or recommendations on specific issues in the governance of State-owned enterprises;

At the request of the authority representing the State, advise it in the process of evaluating the performance of the members and leaders of the supervisory and management organs of State-owned enterprises;

At the request of the authority representing the State or an organ of a State-owned enterprise, advise it in the process of drafting the working procedure of the collegial organ, the job description of the organ’s leader, as well as other documentation relating to the management organisation of the State-owned enterprise;

Present its opinion on whether or not it would be reasonable to invest State assets;

Perform other functions assigned to it by the Procedure and other legal acts.

Source: (OECD, 2015[21]).

Develop a state ownership policy

The government should use its ownership policy to clarify and prioritise the reasons why the state should own any given enterprise. Ownership policy should also define the respective responsibilities of the state bodies involved in its implementation, including the current mandate of the newly established ownership co-ordination unit. The ownership policy should ideally take the form of a concise, high-level policy document that outlines the overall rationales for state enterprise ownership. The ownership co-ordination unit could lead the development of the ownership policy based on consultation with all relevant ministries to ensure sound implementation thereafter. The state ownership policy should clearly define all corporate governance and disclosure requirements specific to SOEs, taking into account differences in market orientation, size or legal form. Lastly, a good ownership policy should be relatively brief, comprehensible and ideally underpinned by overall principles for good exercise of ownership. (An example of the latter is found in Box 5.5).

Box 5.5. The Norwegian state’s Principles for Good Ownership

In Norway, ownership policy is developed and revised at regular intervals by the government. The policy is passed by Parliament and communicated to the public. Norwegian motivations for privatisation are derived from the state ownership policy according to which there are categories of SOEs with different objectives for ownership. SOEs where the government has only commercial interests (category 1) are normally considered to be candidates for privatisation.

1. Shareholders shall be treated equally.

2. There shall be transparency regarding the State’s ownership of the company.

3. Decisions regarding ownership and company statutes are made by a shareholder meeting.

4. The State will, if relevant jointly with other owners, define objectives for the company. The company’s Board of Directors are responsible for implementing the objectives.

5. The capital structure in the company shall be adapted to the purpose of State ownership as well as the company’s financial situation.

6. The composition of the Board shall reflect competence, capacity and diversity, based on the characteristics of the individual company.

7. Remuneration and incentives should be designed with a view to enhance value creation in the company and be perceived as reasonable.

8. The Board shall perform an independent oversight of the company’s management on behalf of the owners.

9. The Board should have a work schedule; it should actively work to develop its own competencies. The Board’s work must be evaluated.

10. The Company must be aware of its social responsibilities.

Source: (OECD, 2018[22]).

As mentioned above, it is considered good practice to review governments’ enterprise ownership rationales at regular intervals. This further links with the issue of divestment, because if such reviews lead to the conclusion that certain SOEs no longer need to be in state ownership, then the obvious next step will be to add them to the list for privatisation (Box 5.6).

Box 5.6. National examples of assessment of the rationale of SOEs that can guide any privatisation decision

In France, privatisation may be envisaged to generate additional public resources for reinvestment in the economy, in accordance with the State Shareholder Guidelines, and to improve the financial structure of an enterprise by providing private capital. In accordance with Article 22, I and VI of the Ordinance dated 20 August 2014, in certain cases transfers of the majority of a company’s capital to the private sector must be authorised by law. In the event of legislative authorisation, the explanatory memorandum of the authorisation law (ensuring parliamentary debate) may indicate the rationale and objectives pursued by the state at the time of privatisation. Capital transactions are conducted in accordance with the aforementioned State Shareholder Guidelines.

The German government has issued an official ownership policy which, among other things, establishes a purpose for state ownership. If the purpose is not, or no longer, applicable, an SOE will, in principle, be privatised. The Federal Budget Code establishes that there must be “an important interest” in ownership on the part of the state and this purpose “cannot be achieved better and more efficiently in any other way”. In addition, principles of good corporate governance in SOEs exist and the understanding is that if a company cannot, or will not, abide by these then it is a candidate for divestment.

In Kazakhstan, the government issued a Resolution in 2015 which, among other things, sets out a privatisation programme for 2016-20. It identifies the following main rationales for privatisation: (i) strengthening national entrepreneurship; (ii) lowering the state’s share of the economy; and (iii) further development of the business sector through the transfer of state assets to more effective owners. The Resolution is publicly disclosed, as is the list of state assets slated for privatisation which is published online. Direct bidding for state assets is possible through an Electronic Trading Place operated via the Internet.

In Latvia, the State Administration Structure Law, effective from 1 January 2016, states that, unless otherwise prescribed by law, the state may establish a company or acquire shares in an existing company only if: (i) this leads to the elimination of market imperfections; (ii) the goods and services provided by the company are deemed of strategic importance or pertain to national security; and (iii) corporate properties themselves are of strategic importance to national security. The Law further provides that state participation shall only be retained in companies which meet these provisions; all other participation shall cease. As criteria for privatisation are established by law, they are required to be transparent and communicated to the general public. Pursuant to the Governance Law, the state’s direct participation in a company shall be assessed no less than once in five years.

Source: (OECD, 2018[23]).

Clarify the financial and non-financial performance objectives of SOEs

Policy makers should ensure that SOEs receive adequate compensation for the public policy priorities they are asked to undertake. They should neither be put at a competitive disadvantage nor have their competitive activities effectively subsidised by the state. At the same time, any obligations and responsibilities that an SOE is required to undertake in terms of public services beyond the generally accepted norm should be clearly mandated by laws or regulations. Such obligations and responsibilities should also be disclosed to the general public and related costs should be covered in a transparent manner. Along with the ownership policy, the government should set clear financial and non-financial performance targets for all state-owned enterprises. The definition of objectives could usefully start with a classification of SOEs according to whether they fulfil (i) a mainly public policy function; (ii) a primarily commercial function; or (iii) a mixture of both. The business operations of SOEs should be subject to rate of return expectations compatible with private sector returns, except where precluded by significant public policy obligations (this point is related to the level playing field considerations developed below). A structured mechanism should be put in place to define and monitor these company-specific performance objectives. The development of such objectives could be undertaken by the state ownership co-ordination unit in consultation with the line ministries.

Aggregate reporting by the state

Government could further improve the current public reporting system by publishing its end-of-year aggregate report within a reasonable period of time, developing a dedicated publicly available website which publishes information on individual SOEs (Box 5.7), and adopting international auditing and accounting standards. The Vietnamese authorities could also consider developing and implementing the relevant provisions of the national corporate governance code applicable to SOEs on a “comply or explain” basis.

Box 5.7. National examples of aggregate reporting and disclosure

Aggregate reporting on the SOE portfolio in Ukraine

The OECD Guidelines on Corporate Governance of SOEs place emphasis on aggregate reporting that synthesises information on the performance of state-owned enterprises which contribute to a culture of greater accountability in the public administration. Good practice calls for the use of Web-based communications to facilitate access by the general public.

Over the last five years, the Government of Ukraine has worked towards improving transparency and disclosure in its large state-owned sector, which is fully decentralised with over 85 different state actors, ranging from the Cabinet of Ministers and State Property Fund, to line ministries and state agencies exercising ownership rights.

Since 2014, the Ministry of Economic Development and Trade of Ukraine (MEDT) has published an aggregate report on state ownership of the top-100 economically important SOEs. The report is published periodically issued annually and is published on the website of the Ministry. Previous iterations of the report have been available in both English and Ukrainian. The report provides financial and operational results of the largest SOE, and highlights key financial data on the performance of individual SOEs and key sectors of the economy where the state is present.

Recently, additional improvements have been made to enhance the availability of information. In July 2019, an e-reporting system, Prozvit, was launched by the MEDT with the support of Transparency International Ukraine and the German Society for International Cooperation (GIZ). The portal, which is also available in English, contains financial indicators of more than 3 500 state-owned enterprises under the control of central executive authorities, on the basis of their financial statements. The transition to an e-platform represents a significant improvement in transparency and disclosure practices by the state towards the general public.

Korea’s online disclosure system

While the Ministry of Economy and Finance (MEF), the ministry responsible for SOEs, does not produce an annual aggregate report per se on the entire SOE sector or the sizeable portfolio of SOEs, the ALIO disclosure system – a consolidated online information system – can be considered as functionally equivalent. The ALIO system, which was set up in 2005, forms part of Korea’s comprehensive SOE reform efforts and facilitates public access to overall SOE performance (see www.alio.go.kr). The system serves as an online repository of both financial and non-financial information for all public institutions in Korea, including SOEs. SOEs (and other public institutions) are mandated to disclose operational data in accordance with 42 standardised categories of financial and non-financial information (initially only 20 items had to be disclosed). Such aggregate disclosure is supported by Official Information Disclosure Act, which became effective in January 1998, and required that information on the operation of the government agencies, SOEs and public institutions be disclosed.

The MEF provides a set of guidelines regarding the kind of information that should be disclosed and instructions on how to implement the disclosure system. Each SOE uploads the data online with guidance from the Ministry, while the Ministry itself is in charge of reviewing the data sets. The ALIO system basically includes all information on individual SOEs. It presents major statistics by type such as financial information, the number of employees, recruitment, average remuneration level of executives (CEOs included) and employees, benefits, liabilities and so on. The online information published on ALIO is available for consultation by the public. Anyone who wants the data is able to download them. In addition, information on job vacancies in SOEs, bid notices and the website link for reporting corruption are also available on the ALIO website.

The MEF monitors all information registered in the ALIO system and can impose penalties on SOEs in cases of negligent or imprecise information disclosure. The scale of penalty ranges from 0.1 to 5 and the penalty points feed into annual performance evaluations for SOEs undertaken by the MEF. If the number of penalty points exceeds 20 in a given fiscal year, the MEF can require SOEs to produce a plan on how to prevent recurrence and provide them with a training programme. If penalty points exceed 40 in a given fiscal year, they are listed as “negligent SOEs” on the ALIO system for a period of three months. The MEF also can order them to post such information on their company website for the same period of time. Companies that are listed as “excellent SOEs” with no penalty points for three consecutive years can be exempted once from disclosure duty, if they so choose.

Integrated reporting system in the Philippines

The Governance Commission of Philippines has initiated the development of the Integrated Reporting System (ICRS) through a single online web portal. Its main objectives are to: i) assist the state in the exercise of its ownership rights in the government-owned and controlled corporation (GOCC) sector through the provision of up-to-date, complete and relevant information; ii) streamline the various reportorial requirements for SOEs; and iii) promote greater transparency and timely access to relevant information on the SOE sector. The ICRS has two main components. The first is the SOE Monitoring System, which pertains to financial information about SOEs, such as, but not limited to, financial statements and corporate operating budgets. The second is the GOCC Leadership Management System (GLMS), which pertains to non-financial information regarding SOE profiles, such as, but not limited to, the latest version of the charter, performance scorecards and organisational structures. It also includes information on incumbent Appointive Directors.

Since implementation of the ICRS is relatively new, the majority of SOEs experienced delays in submitting the information required by the ICRS. Instead of uploading quarterly financial reports, most SOEs are submitting annually on a per request basis. Thus, in order to address these delays, the GCG Memorandum Circular 2014-02, included a deadline for compliance with the ICRS as an additional Good Governance Condition for the release of their Performance Based Bonus (PBB).

Source: (OECD, 2019[7]) and submissions to various meetings of the OECD Asia Network on Governance of SOEs.

Ensure a level playing field

It is recommended to fully implement the legal provisions which specify that SOEs do not (as compared to private entities) have preferential rights such as access to land or other resources made available to the state, do not pay below commercial rates for access to capital, and are not exempt from taxes and charges. The principles of competitive neutrality should be applied to all levels of government including central, provincial and municipal governments (national approaches are highlighted in Box 5.8). Under the Competition Act, central and local governments should be banned from acting in ways that discriminate between market participants or hamper competition, and the competition authority should be able to take action against public entities at central and local levels that engage in such behaviour. When the government makes a decision to sell assets in industries where SOEs dominate or are oligopolistic operators, special challenges may arise. The competition authority or another independent body specialised in competition law must be consulted with a view to ensuring that the relevant markets are competitive after the sale. The competition authority should be adequately resourced to enable it to give thorough and considered advice on these issues.

When SOEs act as procurers of goods and services, in particular when they operate a state monopoly and/or undertake public service obligations, the related procedures should be subject to the same public procurement requirements applicable to the general government sector.

Box 5.8. National approaches to competitive neutrality

An increasing number of countries have come to share a commitment to the principle of competitive neutrality. Mostly, they have been motivated by domestic reform agendas aimed at reducing inefficiencies in the SOE sector and securing a healthy domestic competitive environment. However, with the inclusion of SOE disciplines in recent multilateral trade and investment agreements (e.g. the Trans Pacific Partnership), many jurisdictions have addressed these commitments by incorporating explicit competitive neutrality commitments into their ownership, competition, public procurement, tax and regulatory policies. Examples include the following:

Australia. The Competition Principles Agreement (1995), agreed among the Commonwealth and all the States and Territories, established the overarching competitive neutrality principle that government businesses should not enjoy any net competitive advantages simply as a result of their ownership. The Australian Competitive Neutrality Policy Statement (2004) details the application of competitive neutrality principles in the Commonwealth, and similar statements are available in all States and Territories. Implementation guidelines exist at the national and subnational level to assist managers in enforcing the financial and governance framework of competitive neutrality. The Australian Government Competitive Neutrality Complaints Office administers a complaints mechanism intended to receive complaints, undertake complaints investigations and advise the Treasurer and responsible Minister(s) on the application of competitive neutrality to government businesses.

Finland. Competitive neutrality is high on the agenda of government authorities to ensure, by means of competition policy, equal preconditions for private and public service production as applicable in the Finnish Competition Act. In addition, the State Enterprises Act and the Local Government Act apply as respective “companies’ acts” stipulating the legal personality, organisation and basic functions of government enterprises. The former was recently amended (January 2011) to incorporate (to the extent possible) companies operating under this act. An amendment to the latter is currently being considered with a view to introducing a corporatisation obligation for municipally owned economic operators engaged in competition with private operators within a market.

Sweden. Since January 2010, the Swedish Competition Act has included a new rule that aims to overcome difficulties faced by anti-trust regulators where previous antitrust rules fell outside the scope of Competition Act and the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU. The rule encompasses all types of government commercial activities and prohibits public undertakings from operating (national and subnational level) if they distort or impede competition. The aim is to avoid market distortions where government-owned businesses are present.