The multi-dimensional analysis identifies constraints to Viet Nam’s development along the Sustainable Development Goals. To improve people’s quality of life and opportunities, access to upper-secondary education and more sophisticated skills has to improve, together with coverage of social protection and health system. Boosting productivity requires enhancing the macroeconomic policy framework, tackling inefficiencies in the state sector, handling large pockets of low-productivity firms, and promoting integration between domestic and foreign firms. Global and domestic challenges call for fiscal policies and financial reforms to mobilise private resources. Building capacity of the public administration and building predictability around the legislative process should create a more conducive business environment, ensure effective implementation and re-establish trust in institutions. Finally, a more efficient use of natural resources and horizontal management of impact from natural hazards are required to bring Viet Nam back on a sustainable growth path.

Multi-dimensional Review of Viet Nam

2. Multi-dimensional constraints analysis in Viet Nam

Abstract

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

People – towards better lives for all

The People pillar of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development focuses on quality of life in all its dimensions, and emphasises the international community’s commitment to ensuring all human beings can fulfil their potential in dignity, equality and good health.

Viet Nam has raised living standards and reduced poverty without escalating inequalities. However, this is no longer a given: differences in access are increasing in the face of pressures stemming from a rapidly ageing and modernising society. To ensure that future growth is both sustainable and inclusive the government needs to: i) improve the outcomes of vulnerable groups including ethnic minorities, people with disabilities and urban migrant workers; ii) increase enrolment in upper-secondary education ensuring that students leave with job-relevant skills; iii) adopt a systemic approach to social protection and continue to increase adequate coverage, particularly for informal workers; and iv) provide high-quality and affordable primary healthcare services and develop solutions for long-term old age care (Table 2.1). Gaps also remain in terms of the appointment of women to leadership positions and negative perceptions of the value of daughters leading discriminatory practices that favour the birth of sons.

Table 2.1. People – three major constraints

|

1. Access to upper-secondary education is restricted and students are not equipped with job-relevant skills. |

|

2. The social protection system is characterised by low coverage and high fragmentation. |

|

3. Current pension and health care arrangements, including primary and old-age care, are not financially sustainable and do not guarantee adequate and equal benefits for all population groups. |

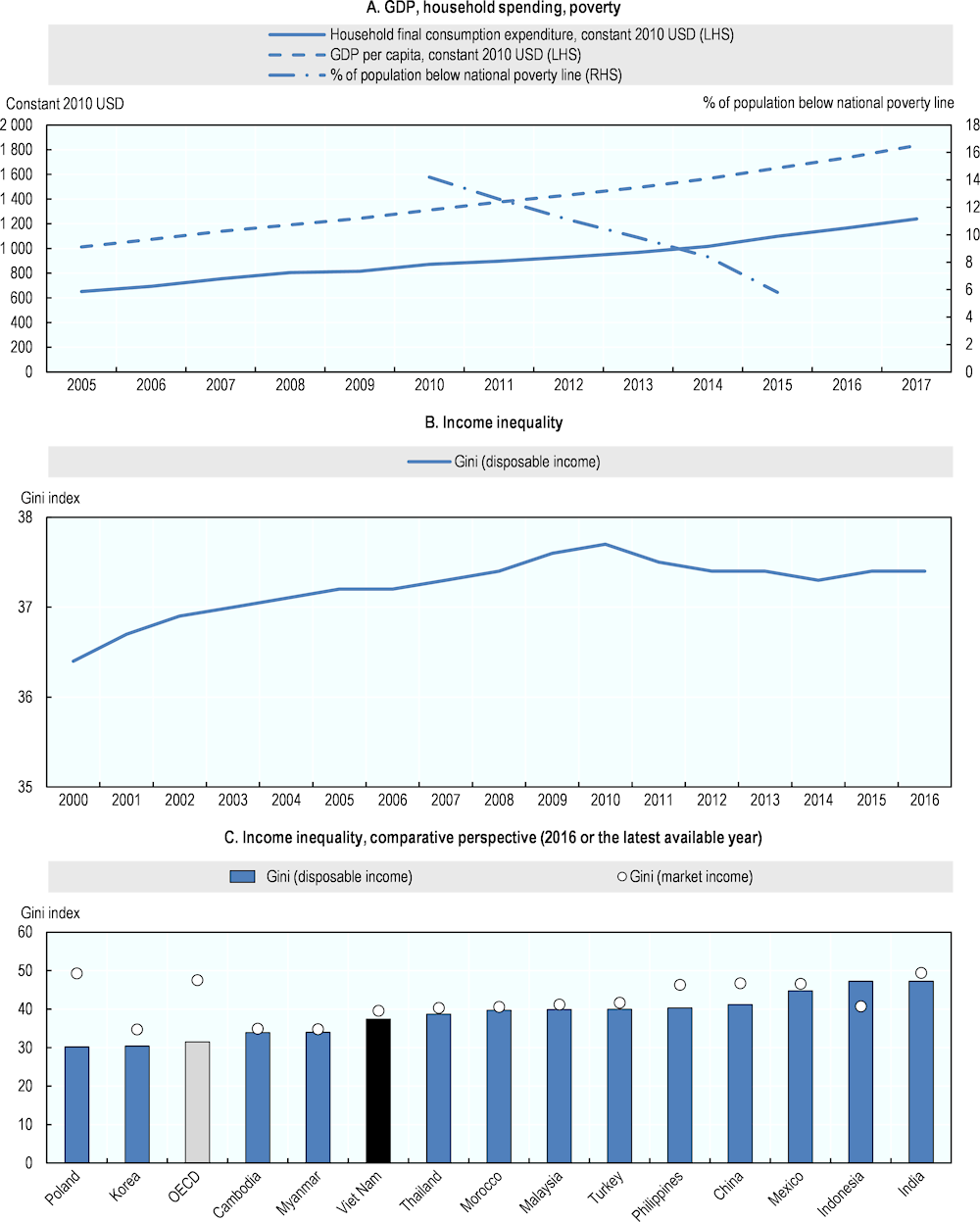

To date, Viet Nam has combined growth and poverty reduction without losing equity

Viet Nam has made tremendous achievements in human development and social inclusion since the launch of the Ðổi Mới reforms. Over the last decade, household spending has risen in line with GDP per capita and nearly doubled. Over 2010-15, the share of the population living below the national poverty line has halved to 5.8% (Figure 2.1, Panel A). Multidimensional poverty (which has been officially adopted by the government and takes into account deprivations in health care, education, water and sanitation, housing and access to information) also halved to 7.9% over 2012-17 (Ministry of Planning and Investment of Vietnam, 2019[1]). Unlike other countries, this has been accomplished without extreme increases in income inequality (Figure 2.1, Panel B and C).

Figure 2.1. Household spending and living standards have risen, and inequality is lower than that of regional peers

Note: Panel C: Years refer to 2012 for India, 2014 for Morocco, and 2015 for China, the Philippines and Myanmar.

Source: Panel A: World Bank (2019[2]), World Development Indicators, https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/dataset/world-development-indicators; Viet Nam Ministry of Planning and Investment. Panel B and Panel C: The Standardized World Income Inequality Database, https://fsolt.org/swiid/swiid_downloads/; OECD Income Distribution Database.

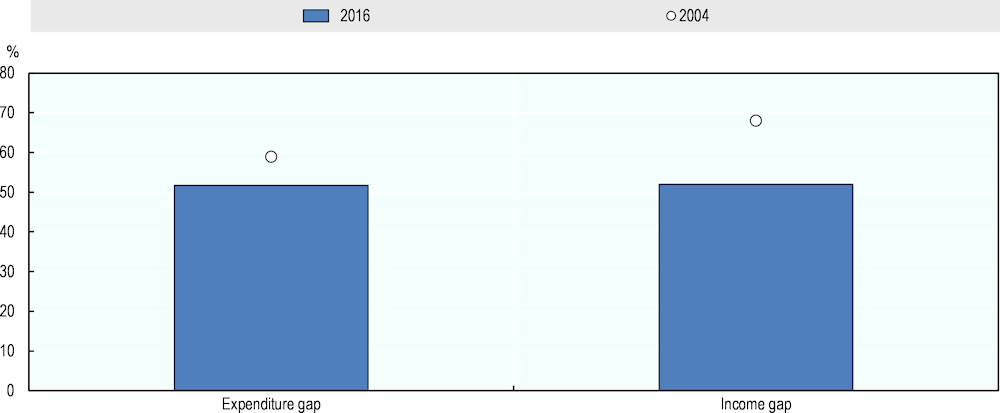

However, some inequalities show signs of widening, and vulnerable groups are at risk of being left behind in the country’s remarkable development story. These include women and the elderly (see below) and, notably, ethnic minorities, who constitute 15% of the country’s 54 ethnic groups and continue to display worse outcomes than the majority Kinh population and the relatively rich Hoa (Figure 2.2). Despite relative gains in welfare, ethnic minorities account for 70% of the extreme poor (using a national extreme poverty line), and account for twice the proportion of people without any qualifications, at 43.8% (Ministry of Labour, Invalids and Social Affairs and UNDP, 2018[3]). While 8.1% of adolescent boys and girls aged 11-14 were out of school, in 2016, this rate was much higher for ethnic minority adolescents (24.5% for Khmer children and 28.6% for H’Mong children of the same age group) (Viet Nam Ministry of Education and Training, 2016[4]).

The widening disparities among ethnic groups have multiple drivers. They include geographical isolation (there are visible spatial differences in poverty incidence with the Northern areas performing worse), limited access to public services and quality land, social exclusion due to discrimination, lack of Vietnamese language skills and low rates of out-migration (Mekong Development Research Institute, 2018[5]). Ethnicity – as well as gender – is also strongly negatively correlated with progression on the career ladder and social mobility (OECD, 2014[6]).

Figure 2.2. Gaps in living standards between the Kinh and ethnic minority groups are increasing

Note: Expenditure/income gaps express the expenditure/income of ethnic minorities as a percentage of that of the Kinh and Hoa groups. For example, in 2016 the expenditure of ethnic minorities was 52% of that of the Kinh and Hoa.

Source: Ministry of Labour, Invalids and Social Affairs and UNDP, 2018.

People with disabilities also have worse well-being outcomes. The poverty rate of households with a disabled member is 20% higher than households without one, and 52% of children with disabilities are unable to access education (UNDP, 2016[7]). Disability represents a significant challenge in Viet Nam, with 15.3% of the overall population and 55% of those aged 70 and over having a disability in 2010 (ILO, 2013[8]). Children with disabilities tend to be stigmatised: 50% of respondents in Viet Nam’s “National Survey on People with Disabilities” believed that children with disabilities should not attend mainstream schools with other children (Viet Nam General Statistics Office, 2018[9]).

Urban migrants are a third group lacking full equality of opportunity, due to the hộ khẩu system, which links household registration to public service access. At least 5 million Vietnamese without permanent registration in their place of residence have only limited access to education, health care and administrative services (World Bank, 2016[10]).

At the same time, at the top of the income distribution, the number of millionaires (USD) has tripled over the last decade and is projected to double again by 2025 (Oxfam, 2017[11]; Credit Suisse, 2018[12]). In Viet Nam, (disposable) income inequality, despite being lower than regional peers, is currently above the OECD average, and growth, rather than redistribution, is responsible for the recent decline in poverty. A majority of the population are worried about disparities in living standards, with the greatest discontent found in urban areas, where 76% of residents perceive inequality as a challenge (World Bank, 2014[13]).

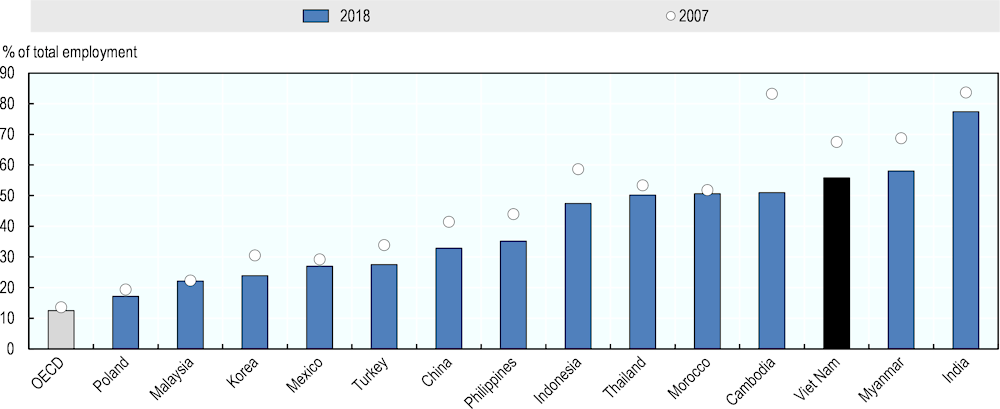

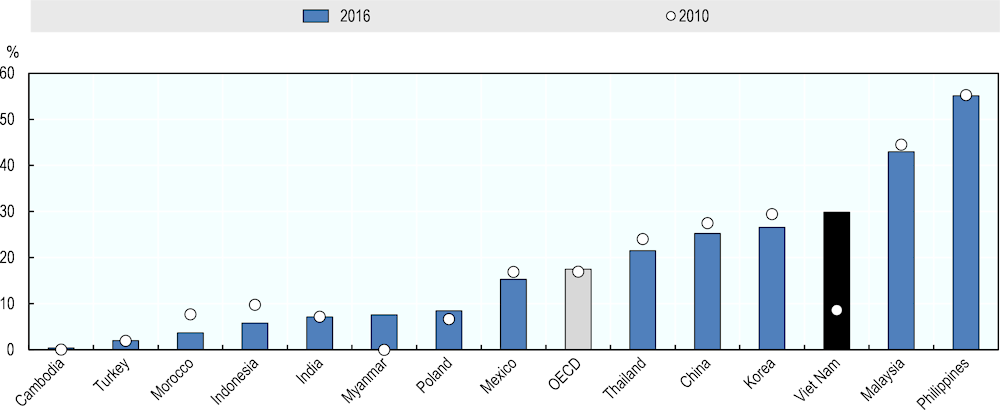

Informal employment is likely to remain widespread

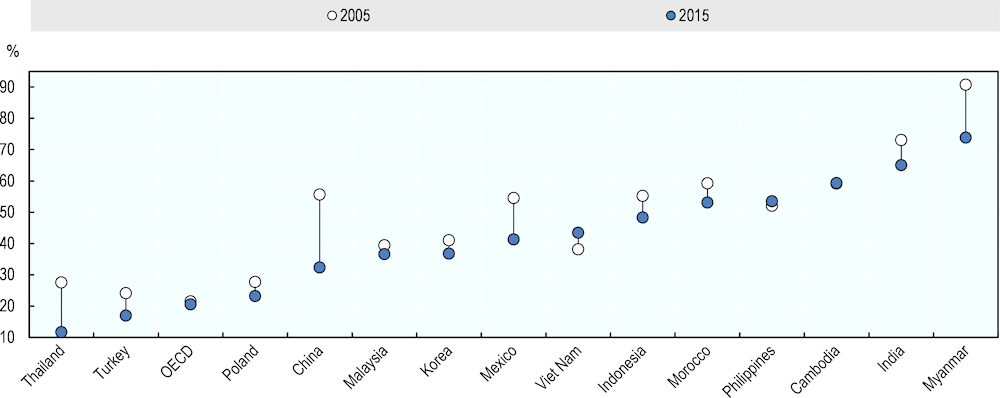

A large share of Viet Nam’s employed population earn their livelihood in the informal economy. In 2016, informal economy workers accounted for 57.2% of non-agricultural employment, a share that rises to 78.6% if agricultural, forestry and fisheries workers are included (ILO, 2018[14]). The prevalence of precarious employment – which overlaps significantly with informal employment – is also high compared to international standards (Figure 2.3). There are also marked gender and ethnic minority differences (see below). Nevertheless, the informal sector has grown less than the formal sector in recent years (3.4% vs 6.9% of annual growth in 2014-16). In contrast, the number of workers engaged in agricultural households has declined significantly (5% annually) (ILO, 2018[14]).

Figure 2.3. Informality as a total share of employment has fallen, but remains high by international standards

Note: Contributing family workers and own-account workers are classified as engaging in precarious employment.

Source: International Labour Organization, ILOSTAT database.

The extent to which informal workers will be able to contribute to and participate in social protection programmes will define Viet Nam’s path towards inclusive growth. Unlike other contexts where informality might be the only way for workers to survive, more than 50% of household business owners prefer it over any other occupation and professed satisfaction with their job (Pasquier-Doumer, Oudin and Nguyen, 2017[15]). However, almost half of informal business owners make a profit below the minimum wage, and those in the middle of the income distribution spectrum are under-represented in the social security system.

Basic education is excellent but restrictive access to post-compulsory education reinforces inequalities, and students graduate without job-relevant skills

Viet Nam has made huge strides in expanding access to primary and lower-secondary education, while simultaneously improving learning outcomes. Net primary and lower secondary enrolment rates are now close to universal and increased from 86% and 72%, respectively, in 1992-93 to 98% and 95% in 2014 (Dang and Glewwe, 2018[16]). Similarly, Viet Nam has made excellent progress in expanding pre-school education, with enrolment rates for 5 year-olds also nearly universal (World Bank, 2019[2]). Several assessments have confirmed exceptionally high academic results during early education, with Viet Nam outperforming many richer countries in Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) tests, although the results should be interpreted with a measure of caution (Box 2.1) (McAleavy, Thai Ha and Fitzpatrick, 2018[17]).

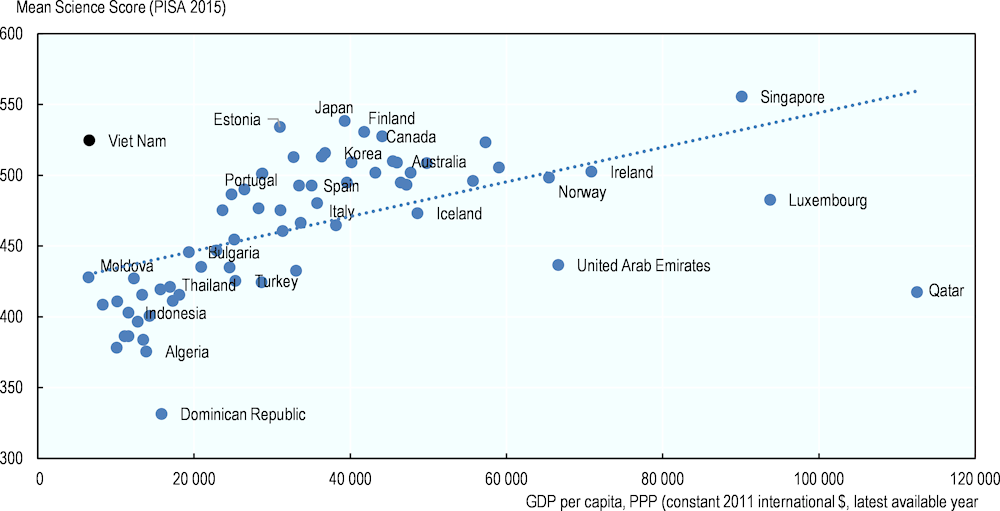

Box 2.1. What explains Viet Nam’s strong PISA performance?

Viet Nam’s exceptional performance in PISA tests has received international attention. The country ranked 17th in maths in 2012 and 8th in science in 2015, outperforming many richer economies (Figure 2.4). A number of reasons have been cited for this success, including the communication of clear student learning goals to all schools and school subsystems, and frequent monitoring of teacher and school performance (McAleavy, Thai Ha and Fitzpatrick, 2018[17]).

However, Viet Nam’s PISA sample is not representative of all 15 year-olds and, as a consequence, the results may be overstated in comparison with other participating countries, pointing towards unequal access to upper-secondary education. Indeed, only 49% of the 15-year-old population is covered by the 2015 PISA sample – the lowest proportion among the 69 participating countries with comparable data (OECD, 2015[18]). Compared to 15-year-old students in national household surveys, students in Viet Nam’s PISA sample also have a higher socio-economic status. Various post-test adjustments result in somewhat lower test scores, although Viet Nam nevertheless remains a positive outlier given its GDP per capita. Moreover, disadvantaged students in the Vietnamese PISA sample outperform most advantaged students in other PISA participating countries (Glewwe et al., 2017[19]); (OECD, 2015[18]).

Figure 2.4. Viet Nam outperforms many richer countries in PISA science test scores

Source: OECD (2016), PISA: Programme for International Student Assessment; OECD Education Statistics (database).

Upper secondary school attendance has also increased in past decades, with enrolment rates reaching 73.4% in 2014, although access is restricted to the highest-performing and most advantaged students. In Viet Nam, compulsory education ends on completion of lower-secondary education, and further progression is subject to competitive entry exams. In addition to being more likely to afford the cost of education, students from more advantaged backgrounds often receive additional support to pass entry tests. Vietnamese households in the top wealth quintile spend 15 times more on private tutoring than households in the poorest wealth quintile (Dang and Rogers, 2016[20]). Other forms of family advantage, such as having a highly educated parent, are also correlated with access to upper-secondary education (Rolleston and Iyer, 2019[21]). Conversely, socially disadvantaged students face substantial barriers: only 50% of ethnic minority children progressed to the first year of upper secondary in 2014, compared to 79% of Kinh/Hoa. This gap has widened since 2004, a trend that is almost completely due to decreasing upper enrolment rates among ethnic minorities rather than higher enrolment of Kinh/Hoa students (Dang and Glewwe, 2018[16]).

Education reform should aim to narrow disparities in access to secondary education. The government should consider moving towards universal upper-secondary school attendance, and either replacing exam-based allocation of places completely, or providing spots for all students even if exams serve to select which specific schools can be attended. Adoption of this model would require additional investment in terms of physical infrastructure and teachers. In addition, authorities need to strengthen the existing vocational training systems and better communicate the potential return from high school education to students who decide not to enrol in upper-secondary (see below).

Additionally, strong academic performance in PISA does not necessarily translate into the creative capacities and interpersonal skills required for a competitive labour market, in which solving non-routine problems is increasingly important. Indeed, an employer survey suggests that between 70% and 80% of Vietnamese graduates do not have the required skillsets for professional or technical high-paying jobs (World Bank, 2014[22]). Relevant transferable digital and interpersonal skills should be integrated into the curriculum as well as into pedagogical approaches, which currently emphasise a rather passive role in learning for students. The currently ongoing textbook and curriculum reform of the Vietnamese Government represents a promising first step in this direction. Chapter 6 addresses challenges in the education system beyond secondary school, focusing on skills mismatch in the vocational sector.

The health system needs to ensure affordable access to good quality services

Viet Nam has generally good health outcomes given its level of development, such as a relatively high life expectancy of 76 years. However, changing disease patterns imply pressure on health care costs. As in other fast-evolving countries, non-communicable diseases pose an emerging problem and currently account for 77% of total deaths, up from 56% in 1990 (WHO, 2016[23]); (Ministry of Health Viet Nam, 2016[24]). This share, and the implied burden on health system delivery and financing, will continue to rise with an ageing and modernising society. Health expenditure is still well below the OECD average (5.7% vs. 12.4% of GDP in 2015) and Viet Nam’s own targets (10% in 2020); however, the government already spends a larger share of its income on health than almost any other country in developing Asia (OECD, 2019[25]).

In addition to direct spending on health care, further efforts are necessary to create basic health-related infrastructure, such as sanitation, and overcome poor hygiene practices. Access to sanitation and improved drinking water increased from 70% to 83%, and 72% to 78%, respectively, between 2010 and 2016. Further investments are needed to maintain progress in this important area. Beyond infrastructure, poor hygiene practices, especially the practice of open defecation (OD) remain a concern. The national OD rate was 12.8% in 2016, with rates of 38.7% and 2.2% for the poorest and richest quintile of the population, respectively. OD rates are of particular concern in the Mekong River Delta, Central Highlands and Northern Mountains, at 30.9%, 26.4% and 23.9%, respectively (GSO and UNICEF, 2015[26]; GSO, 2018[27]).

Health insurance coverage has expanded significantly in recent years, although national distribution can be further improved. A series of incremental reforms have resulted in population coverage of 87% by 2019 (compared to 68% in 2013) (Viet Nam Social Security, 2019[28]; UNDP, 2016[7]). This exceeds by far the 80% target for 2020 of the Ministry of Health’s Universal Coverage Master Plan. The reforms include compulsory social health insurance (SHI) for formal workers as of 2015, and full premium subsidisation for the poor under the Social Security Agency (although, as in other low and middle-income countries, targeting has an exclusion error rate of close to 50%). However, enrolment rates are much lower among “missing middle” informal workers (classified under the SHI voluntary contributory category), the near-poor and older persons, who are not entitled to social assistance or social insurance pensions (Somanathan et al., 2014[29]). Pilots projects to improve coverage for informal workers, with the support of donor agencies (e.g. the Asian Development Bank), are currently ongoing.

Increased insurance coverage rates have failed to achieve lower costs and access to quality care for patients. Viet Nam is one of the few countries where out-of-pocket health expenditure (OOP) has risen in the last decade (Figure 2.5). While public health spending has increased, about 50% of total health expenditures are paid OOP (Ministry of Finance; World Bank, 2017[30]). About 25% of OOP health spending comes from the top economic decile; however, high OOP can be catastrophic, especially for poor households, and lead to inequalities in service utilisation and outcomes (Somanathan et al., 2014[29]).

Figure 2.5. Patients spend more on health care despite health insurance expansion

Source: World Bank (2019), World Development Indicators, https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/dataset/world-development-indicators.

Factors driving high OOP expenditure include the reimbursement rules of the insurance regime and an incentive system for providers that rewards the oversupply of expensive treatments. For example, while the scope of the SHI benefits package is expansive, very few services are fully reimbursed (e.g. drugs are excluded), and there is no cap on co-payment expenditures. Current provider payment mechanisms incentivise hospitals to charge patients for higher-end technical services and supplies that are not part of the official price list and package, and rising pharmaceutical prices are passed on to customers and contribute further to cost escalation (Somanathan et al., 2014[29]). Notably, rising chronic conditions, such as those related to age (e.g. dementia), are not yet covered by the health insurance regime.

Moreover, many patients bypass primary health care facilities due to their low quality. While many hospitals exist at the district level, trust in the primary care system and its often understaffed facilities is very low. Patients prefer to travel to larger cities where they incur higher co-payment rates, or seek care at private health centres, which are not covered by SHI (Takashima et al., 2017[31]). This leads to overcrowded facilities at the central and provincial levels, and much higher inpatient than outpatient spending (World Bank, 2016[10]).

Going forward, it will be essential to improve skills and resources at the primary care level, within an integrated and more efficient overall health system that rewards quality performance and accounts for the health needs of an ageing population and the growing demands of the rising middle class. This will have to involve greater co-ordination and the development of uniform oversight approaches between the agencies involved in the different aspects of health insurance and delivery (Viet Nam Social Security, the Ministry of Health, provincial level Departments of Health).

The pension system does not provide adequate benefits or coverage, and there are concerns about its financial sustainability

While the social protection system covers social assistance in a broader sense and should be viewed as integrated system, adequate pension provision will become especially important given the challenge of rapid demographic change. Viet Nam has made remarkable progress in expanding social insurance coverage beyond public-sector workers in recent years, although overall coverage remains below the 2020 target of 50% and the newly adopted goal of universal coverage by 2035. Vietnamese Social Insurance (VSI) covers about 58% of salaried workers, but total labour force coverage remained at 23% in 2015, due mainly to low voluntary contributions by informal workers (Castel and Pick, 2018[32]).

Only a small proportion of the currently retired population receives a pension or other form of income support. As of the end of 2015, the VSI paid monthly pensions to only 2.5 million individuals, representing the small proportion of the retired private sector workers able to contribute for the minimum 20-year vesting period. Despite arrangements for the payment of social pensions for the poor and merit payments for those involved in Viet Nam’s revolution, only about 20% of the population aged 65 and over received public old-age income support of some sort in 2012 (Castel and Pick, 2018[32]).

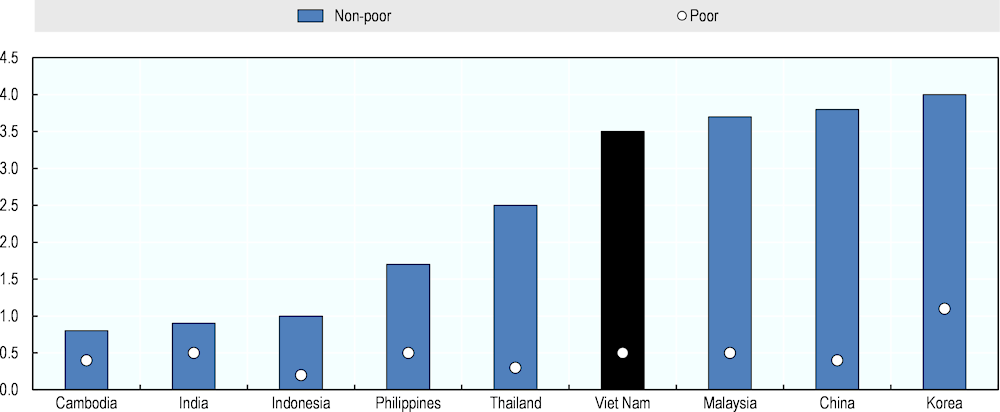

Pension transfers are disproportionately captured by those already relatively well-off. More than half the elderly in the bottom two income quintiles receive no public income support in old age (2015), and men are currently more likely than women to receive a contributory pension (12% vs 8% in 2012) (Castel, La and Tran, 2015[33]; ILO/UNFPA, 2014[34]; Evans and Harkness, 2008[35]). In Viet Nam, as in other countries in the region, social security systems that are tied to formal employment disproportionally benefit the non-poor (Figure 2.6). As a result, the redistribution effect of social protection programmes is weak compared to the OECD average (Figure 2.3, Panel C).

Figure 2.6. Social protection schemes disproportionately benefit the non-poor

Note: The Social Protection Index (SPI) equals total expenditures on social protection divided by the total number of intended beneficiaries of all social protection programmes, normalised by poverty-line expenditures (which for cross-country comparability purposes are set uniformly at 25% of GDP per capita). An SPI of 0.10 would thus be equivalent to 2.5% of GDP per capita. A higher SPI denotes better social protection. No data are available for Myanmar.

Source: Asian Development Bank, The Social Protection Index Assessing Results for Asia, Mandaluyong.

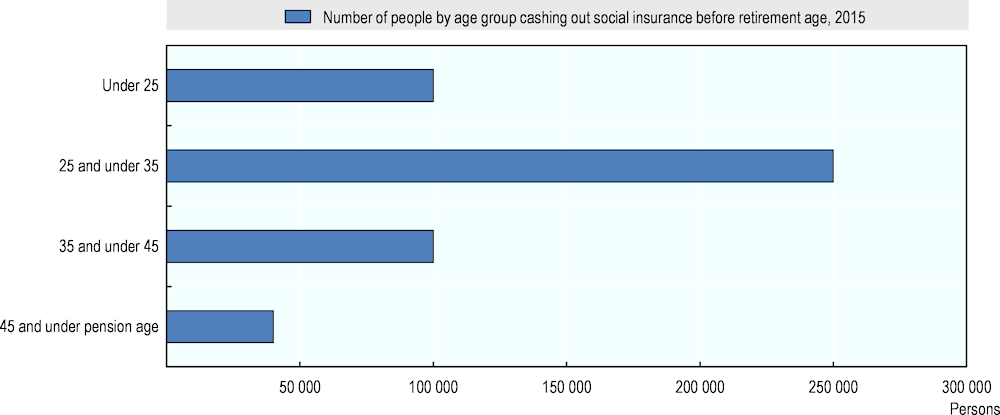

Young workers tend to cash out their savings early when switching jobs, motivated largely by lack of trust in the sustainability of the system (Figure 2.9). This behaviour could be partly mitigated by ongoing efforts to expand coverage of unemployment insurance, including benefits beyond income support. This underlines the importance of viewing social insurance as part of a broader social protection system. Similarly, efforts to ensure that social assistance arrangements provide adequate benefits will be important to offset delays in narrowing coverage gaps in contributory arrangements (Castel and Pick, 2018[32]). Viewing social insurance and assistance as part of a single policy framework would enhance the currently fragmented system, which consists at present of numerous small regulations across agencies and government tiers, which in effect exclude many population groups, such as young children, from benefit eligibility (Figure 2.7) (UNDP, 2016[7]). Furthermore, an integrated payment platform and a corresponding unique national identification system (the most recent ID card did not include biometric data) would accelerate efficiency and accountability.

Figure 2.7. Younger workers prefer to cash out their social insurances

There are concerns around the long-term financial sustainability of the Social Insurance Fund. Increase in the fund’s expenditure exceeds growth in revenues, while the present value of projected expenditure is higher than projected revenues (World Bank, 2012[36]). This trend is driven by a rapidly increasing dependency ratio, low retirement ages (which remain lower for women under current reform efforts), generous benefit calculations in the face of lower than expected investment returns and indexing of payments to the minimum wage (Castel and Pick, 2018[32]). In addition, pension contributions from employers are not enforced for all enterprises.

The government has already increased contribution rates in recent years, and now needs to focus on expanding the contribution base by enrolling a higher proportion of the workforce, while improving the fund’s financial outlook. Coverage among the large household enterprise sector can be increased by lowering the cost of contributions, easing registration for employers and avoiding punitive measures for belatedly registering employees (Castel and Pick, 2018[32]). Management of the Social Insurance Fund will need to focus on higher returns, potentially expanding investment options beyond government bonds. A 2018 resolution for a Master Plan on Social Insurance Reform included several bold and sensible proposals, such as approximation of replacement rates to international general levels, and a potential target to lower the vesting period to 10 years (ILO, 2018[37]).

Maintaining the long-term solvency of the Social Insurance Fund requires the introduction of automatic balancing mechanisms reflecting demographic or labour market outcomes, at least in the short term. Benefit levels, indexation formulas, retirement age and other parameters determining the accrual rates of the pension system would adjust automatically without the intervention of policy makers or discussions among social partners. This approach could help put Viet Nam’s pension systems on a financially sustainable path. However, the sustainability and adequacy of pension benefits over the long term will ultimately depend on the authorities’ capacity to agree on reform through social dialogue and well-informed policy making.

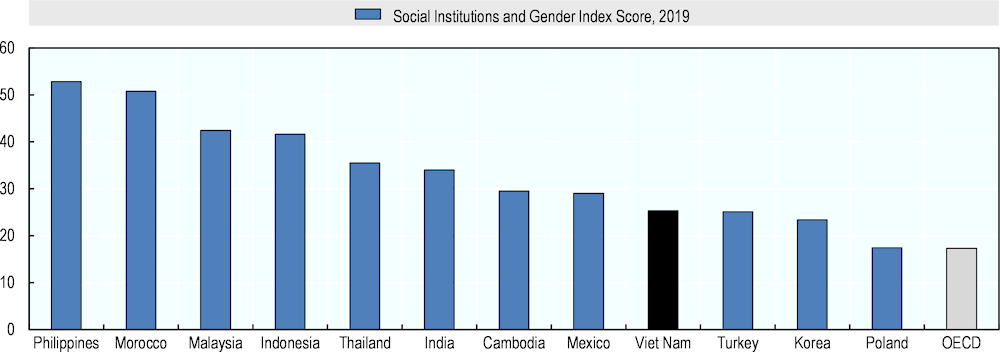

Viet Nam performs well on many measures of gender equity, but women face worse employment conditions, and some harmful gender biases persist

The level of discrimination against women in laws and social norms is relatively low (Figure 2.8). For instance, Viet Nam’s female labour force participation (71%) is by far the highest among the comparison group for which data are available, and significantly above the OECD average (64% in 2017) (OECD, 2019[38]; World Bank, 2019[2]). A gender wage gap persists, but has fallen from 15.4% in 2011 to 12.6% in 2014 (Demombynes and Testaverde, 2018[39]). Women have disproportionally benefitted from contracted wage-paying work in the textiles and apparel export sector, and accounted for 68% of workers in foreign-owned companies operating in Viet Nam in 2015 (although these jobs might be at risk of automation in the future) (Cunningham, Alidadi and Helle, 2018[40]).

Figure 2.8. Discrimination against women in social institutions is comparatively low

Note: The OECD Social Institutions and Gender Index is the unweighted average of a quadratic function of four sub-indices: discrimination in the family, restricted physical integrity, restricted resources and assets, and restricted civil liberties. Both the overall index and the sub-indices range from 0 indicating no discrimination to 100% for absolute discrimination against women. The scores consider qualitative and quantitative information about legislative frameworks, de facto situations and practices through prevalence and attitudinal data. The overall Social Institutions and Gender Index score is not available for China.

Source: OECD (2019), “Social Institutions and Gender Index” (database).

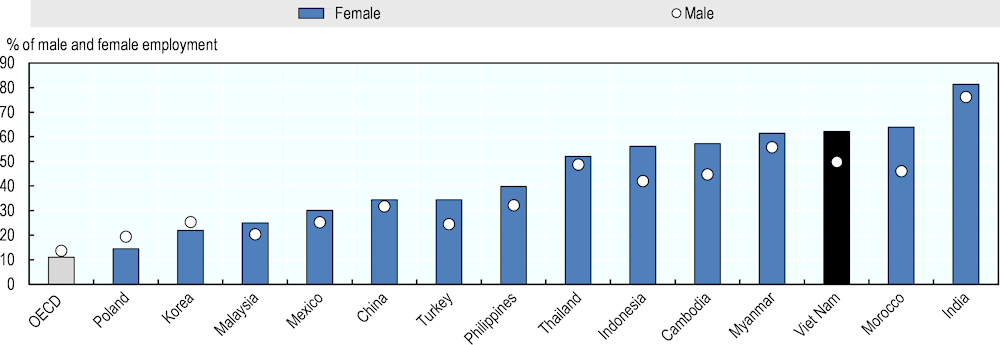

However, indicators of work quality and representation in leadership positions present a different picture. Leadership in the business, government and political spheres is overwhelmingly male. Only 22.4% of top private sector managers are women, and female-led enterprises tend to be smaller than male-led ones (Cunningham, Alidadi and Helle, 2018[40]). National and local quotas for female representation in electoral lists (35%) were introduced in 2015, but in reality this target has not been met, with female members accounting for only 27% of the National Assembly (2016-21 term), and few women serving as committee chairs (World Bank, 2016[10]). Women are also more likely to work in vulnerable employment and have less access to employment security and benefits (Figure 2.9). In addition, well-intended labour laws often lead to de-facto discrimination. For example, Article 160 of the Labour Code excludes women from 70 occupations that policy makers deem as harmful to childbearing and parenting functions (Cunningham, Alidadi and Helle, 2018[40]). Similarly, the pension age for women remains lower than for men (60 vs 62 years) even under current reforms.

Figure 2.9. Women in Viet Nam are more likely to engage in vulnerable employment

Note: The vulnerably employed are defined as own-account workers and contributing family workers.

Source: World Bank (2019[2]), World Development Indicators, https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/dataset/world-development-indicators.

Traditional gender roles tend to be upheld in Viet Nam with women having greater responsibility for housework and child and elderly care, all of which can be a barrier to labour market entry. Vietnamese women spend on average 5.5 hours per day on unpaid care and domestic activities compared to 3 hours for men (General Statistics Office of Viet Nam, 2014-15[41]). The number of hours is higher for women without an education, who undertake on average more than 9 hours of unpaid care work daily (ActionAid Viet Nam, 2016[42]). Among women who are not in the labour force, 40% say that their time is dedicated to home care, compared with 2% of men (Cunningham, Alidadi and Helle, 2018[40]). Overall, the gender difference relating to unpaid care work is below the East Asian and Pacific regional average, which is close to 4 hours of unpaid care work per day for women and 1.5 hours per men (Ferrant and Thim, 2019[43]). However, constraints on improving female labour outcomes may become more intense as Viet Nam’s ageing population increasingly makes greater demands on women for care.

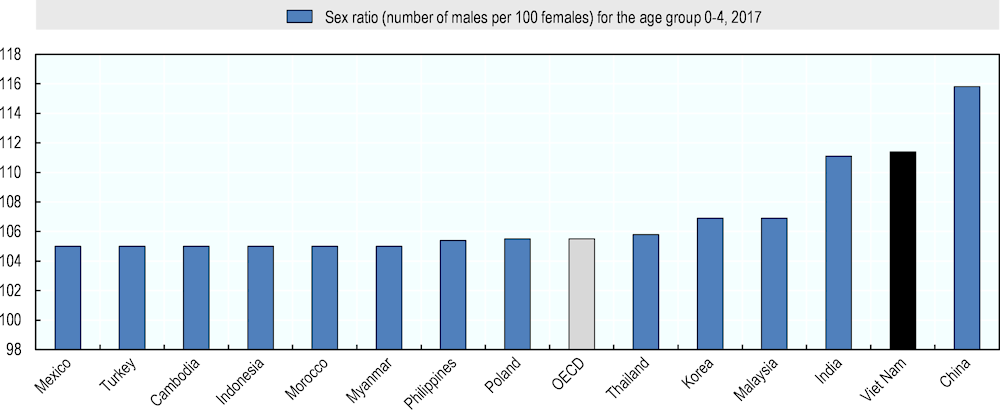

Viet Nam also has one of the most imbalanced sex ratios for children aged 0-4 in the world, pointing to discriminatory practices favouring the birth of sons (Figure 2.10). The sex birth ratio has actually increased in Viet Nam over the last decade, with the spread of ultrasound technology that allows prospective parents to easily identify the sex of the unborn child (UNFPA, 2016[44]). Vietnamese families traditionally place a higher value on sons, partly because they are expected to take on the financial responsibility for caring for parents in old age. Improving social protection for the elderly and the development of a comprehensive long-term care system would contribute to reversing this serious imbalance. In other countries, targeted campaigns to communicate the value of daughters’ labour force participation to parents, and class-room discussions about gender equality among adolescents, have shown promising results in changing societal norms about gender roles (Dhar, Jain and Jayachandran, 2018[45]; Innovations for Poverty Action, 2013[46]).

Figure 2.10. Viet Nam has one of the most imbalanced sex birth rations

Note: The “natural” sex ratio at birth is often considered to be around 105. This means that at birth on average, there would be 105 males for every 100 females.

Source: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2017). World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision, DVD Edition.

Prosperity – boosting productivity

The Prosperity pillar of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development calls for policies that combine structural transformation with a fair distribution of the growth dividend. Over the long term, growth and transformation depend on continuous gains in productivity (i.e. the ratio of outputs to inputs). If productivity gains and labour participation can be ensured, Viet Nam’s future outlook is decidedly positive. To guarantee productivity gains, Viet Nam needs to ensure future fiscal capacity and a stronger banking sector. A more flexible exchange rate regime would provide resilience against shocks, and most importantly, efforts must be made to overcome inefficiencies in investment and large productivity differences between sectors. Greater integration between domestic firms and foreign ones, for example through participation in supply chains, can help in this regard. Finally, human capital needs a boost to enable Viet Nam transform itself into a hub for high value-added activities (Table 2.2).

Table 2.2. Prosperity – major constraints

|

1. The macroeconomic policy framework needs to be improved to address vulnerabilities (fiscal consolidation, banking sector, exchange rate management). |

|

2. Investment in the state sector is characterised by low efficiency. |

|

3. Large pockets of low-productivity firms persist. |

|

4. There is a lack of integration between domestic and foreign firms. |

|

5. Human capital is insufficient to cope with future challenges. |

Robust growth has been supported by a pragmatic and flexible reform process

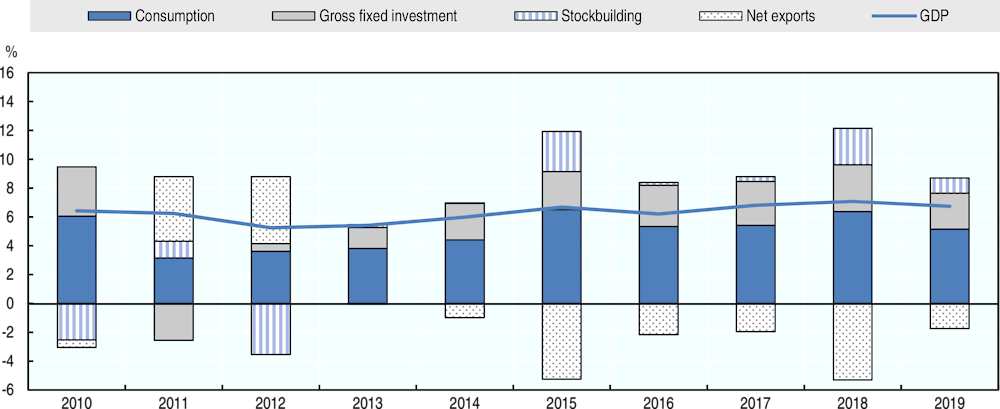

The economy performs relatively well among its regional peers, and is advancing quickly. The average real GDP growth rate over 2014-18 was 6.6% – one of the strongest among Southeast Asian countries. Growth has been driven increasingly by domestic demand, reflecting the rising income of consumers. Exports have also contributed to resilient economic growth, creating a virtuous cycle where increasing exports bring about increasing imports of intermediate and capital goods. Strong business and construction investment have contributed to rapid import growth, especially intermediate and capital goods (Figure 2.11).

Figure 2.11. Viet Nam’s economic growth is robust

Viet Nam’s structural reform efforts have focused on lowering trade barriers and integrating into global value chains, notably through accession to ASEAN, APEC and the WTO. Large-scale inflows of FDI have created a globally competitive manufacturing base, notably in the semiconductor sector. In fact, the share of high-technology products in manufacturing exports increased remarkably during the 2010s (Figure 2.12). Viet Nam is scheduled to implement a comprehensive set of additional structural reforms in line with the commitment of the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) agreement and the upcoming European Vietnam Free Trade Agreement expected to be ratified in 2020.

Figure 2.12. In the past decade, Viet Nam has upgraded its industrial structure significantly and swiftly

Note: High-technology products are those associated with high R&D intensity, and are typically found in the aerospace, computers, pharmaceuticals, scientific instruments and electrical machinery sectors.

Source: World Bank (2019[2]), World Development Indicators, https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/dataset/world-development-indicators.

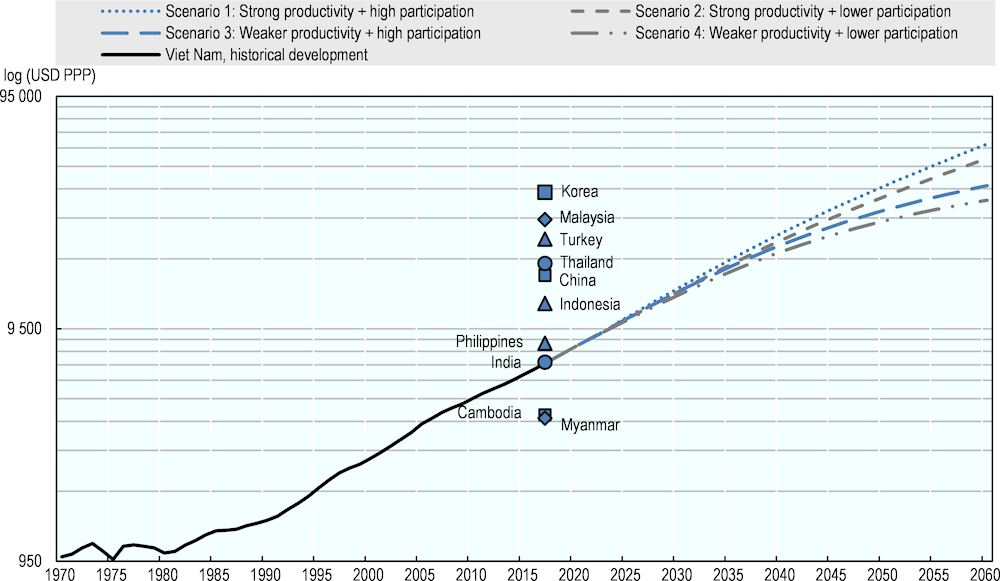

Going forward, Viet Nam will need to focus on productivity growth supported by continuous reform and good macroeconomic management

Simulations of various scenarios (Figure 2.13) highlight the importance of sustaining productivity growth. In addition, Viet Nam will need to address population ageing through the introduction of measures to increase statutory retirement ages. If productivity growth and labour participation are maintained at present levels, per capita GDP (currently similar to that of India) would reach the current level of Malaysia in 2043 and Korea by 2049. In contrast, allowing these growth drivers to decline would postpone attainment of Malaysia’s per capita by eight years, and prevent Viet Nam from achieving Korea’s level of development during the projection period. The rest of this report identifies constraints and opportunities for generating further productivity growth.

Macroeconomic stability is an important enabling condition for further growth and reform. Viet Nam needs to ensure fiscal stability, continue efforts to improve the monetary policy framework and develop the financial sector.

Progress in fiscal consolidation since 2017 has proven very successful, and has significantly improved Viet Nam’s fiscal position. In addition, the new public debt management law has improved debt management and hence helped reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio. In the longer term, a major impediment to the challenge of fiscal consolidation is the limited ability to raise tax revenue. Viet Nam’s tax system has undergone structural changes in recent years, which have created a more growth-friendly tax environment and stimulated investment, growth and job creation, but have had a negative impact on revenues. Ensuring the quality of public expenditure is also necessary to ensure fiscal consolidation.

Figure 2.13. Structural reforms would boost Viet Nam’s long-term growth

Note: GDP at constant prices in local currency were converted into USD PPP using 2017 PPP. The per capita GDP of Myanmar and Cambodia were almost at the same level in 2017. The long-term scenarios (2018-60) for Viet Nam are based on total and working-age population data from the United Nations Division Population (UNDP) medium variant estimates combined with the various scenarios below.

Scenario 1 assumes a gradual decrease in labour productivity growth from 6% to 4%, while the employment-to-population ratio remains constant at 75%.

Scenario 2 assumes a gradual decrease in labour productivity growth from 6% to 4% associated with a progressive fall in the employment-to-population ratio from 75% to 65%.

Scenario 3 assumes a gradual decrease in labour productivity growth from 6% to 2%, while the employment-to-population ratio remains constant at 75%.

Scenario 4 assumes a gradual decrease of labour productivity growth from 6% to 2% associated with a progressive fall in the employment-to-population ratio from 75% to 65%.

Source: Asian Productivity Organisation, APO Productivity database; World Bank (2019[2]), World Development Indicators, https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/dataset/world-development-indicators; United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2017), World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision, DVD Edition; International Labour Organisation, Labour Force Participation, ILO modelled estimates.

Development of the financial sector will be key to allocating resources to productive activities. This must include improving the credit standards of a banking sector dominated by state-owned banks in tandem with reform of SOE governance. The government has set a target to align the capital adequacy of commercial banks with Basel II standards by January 2020. The authorities are also seeking to develop the domestic bond market.

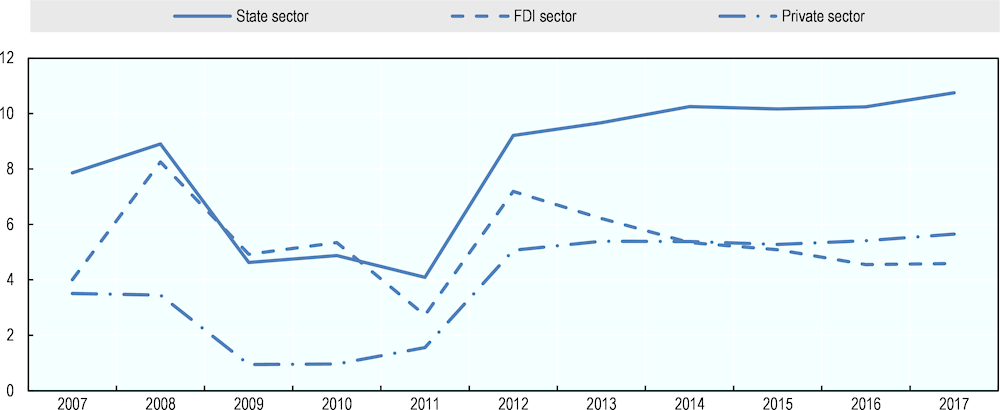

Labour productivity growth needs reinvigoration

The misaligned allocation of resources between the state and the private sector needs to be rectified. Aside from a few highly productive sectors, notably FDI-related sectors such as semiconductor manufacturing, there remain large pockets of low-productivity activities (Chapter 1, Figure 1.2). State-owned enterprises still account for one-third of GDP and receive preferential treatment, including favourable access to credit, land and licences. Despite this government support, the investment efficiency of SOEs has declined in recent years and the gap vis-à-vis the FDI sector has widened (Figure 2.14).

Figure 2.14. The efficiency of state sector has declined

Note: Investment efficiency is measured by the incremental capital-output ratio (ICOR) (i.e. the amount of additional capital needed per extra unit of output, expressed as a ratio). A higher ICOR represents less efficient investment.

Source: OECD calculations based on data from the VN General Statistics Office.

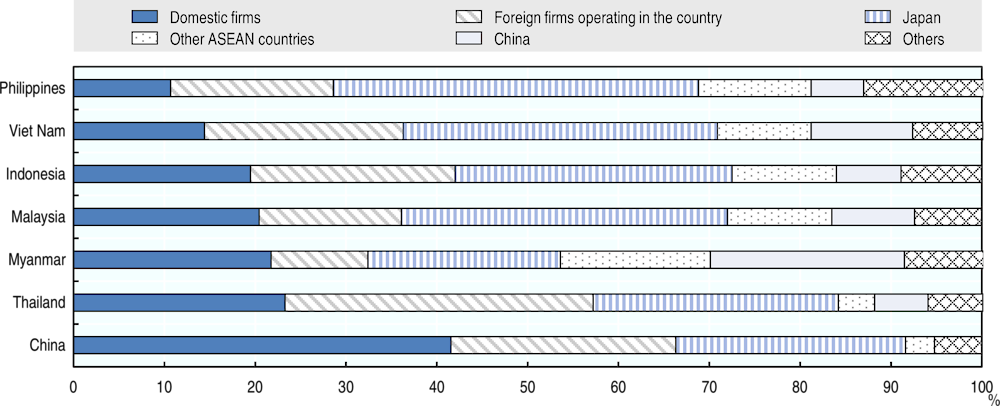

The low level of domestic firm input to foreign manufacturing firms operating in Viet Nam implies that the country is likely to provide low value-added assembly work (Figure 2.15). Local supplier firms are generally unable to meet the quality, cost and delivery (QCD) requirements of customer firms, as is also the case in some peer countries (APEC Policy Support Unit, 2017[47]). Enhancing linkages between FDI firms and domestic firms would result in beneficial spillovers of knowledge and technology. Continuing efforts are also required to boost productivity enhancement, skills improvements and technology adoption.

Figure 2.15. Linkages with FDI firms need to be strengthened

Source: Japan External Trade Organisation, Survey on Business Operations of Japanese firms in Asia and Oceania 2018.

The government promotes SMEs in the private sector by providing targeted support measures and easing the regulatory environment. The government has also stepped up efforts to streamline business regulation with the promulgation of a resolution supporting and developing enterprises by 2020 (OECD/ERIA, 2018[48]). A particular focus is the streamlining of licensing and permit procedures. However, the SME landscape in Viet Nam is still dominated by family-owned and operated businesses with limited access to finance and improvement of technology and managerial skills.

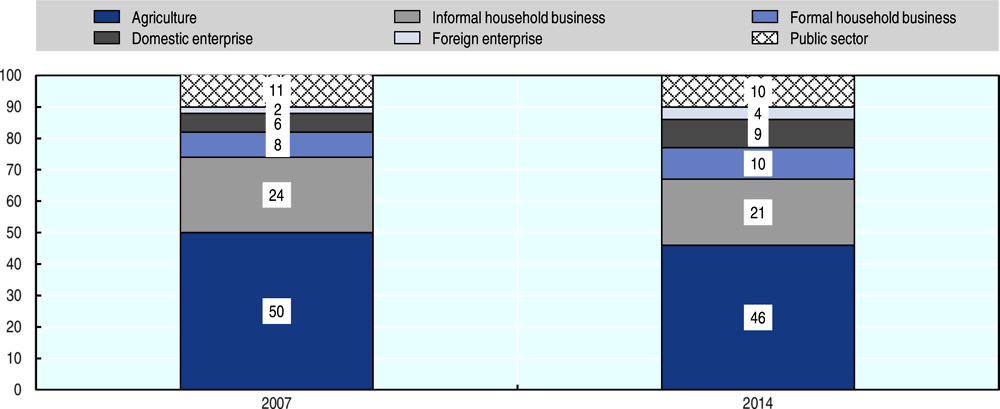

Household enterprises play an important role in the Vietnamese economy, but this contribution needs to be enhanced significantly, given the need to sustain national productivity growth. Household enterprises are the main employer after agriculture, have provided more new jobs than all other sectors combined over the past two decades and accounted for 23% of Viet Nam’s GDP in 2014 (Pasquier-Doumer, Oudin and Nguyen, 2017[15]) (Figure 2.16). However, even though the number of formally registered household enterprises is rising, more than two-thirds are still not registered and thus fall into the informal sector. Household enterprises are characterised by the very small scale of their operations, with average firm sizes amounting to 1.8 and 2.3 workers for informal and formal household businesses, respectively. They also typically have very few linkages and subcontracting arrangements with the formal sector. Labour productivity in the household business sector, especially in the informal part, is low and the contribution of household businesses to gross fixed capital formation is well below their share of GDP (9.4 % in 2014).

Figure 2.16. Household enterprises play an important role in the Vietnamese economy

Human capital development is key to promoting better quality growth

Viet Nam’s labour participation rate is relatively high. However, labour input is projected to decline due to rapid ageing. Gradual raising of the retirement age to align with longer life expectancy, beyond current reform proposals, could mitigate the negative impact of the shrinking labour force.

Skills development will also boost productivity gains. The demand for skills is changing as a result of trends such as technological progress, digitalisation, globalisation and demographic shifts. Debate about the impact of technology on jobs in the future is ongoing. It is likely that cutting-edge technology will result in the automation of more and more complex tasks at accelerating speed, fundamentally changing the skills required for many jobs. Some jobs may even become entirely redundant. Estimates suggest that Viet Nam’s workers are exposed to a relatively high risk of automation (Chapter 1, Figure 1.6).

OECD experience suggests that low managerial quality, lack of ICT skills and poor matching of workers to jobs curb the adoption of digital technology across firms. Similarly, evidence suggests that policies affecting market incentives play an important role in technology adoption, especially those relevant for market access, competition and efficient reallocation of labour and capital. The provision of ICT training to low-skilled workers also accelerates the penetration of digital technology. Among OECD countries, 80% provide support for vocational training and higher education in ICTs. At later ages, broader digital strategies also involve lifelong learning, which empirical results suggest may facilitate adoption, hinging inter alia on continuous vocational training, adult learning and on-the-job training. Several countries have taken explicit measures to remedy the gap between the training participation rates of low and high-skilled workers, for instance, by granting priority access to publicly funded education and training leave for low-qualified workers (Denmark, Spain), or by funding employers to contribute to the cost of training in various ways (Estonia, France, the Netherlands). Additionally, the provision of e-government services can encourage ICT use by individuals by helping to foster an affinity with digital technologies (Andrews, Nicoletti and Timiliotis, 2018[49]).

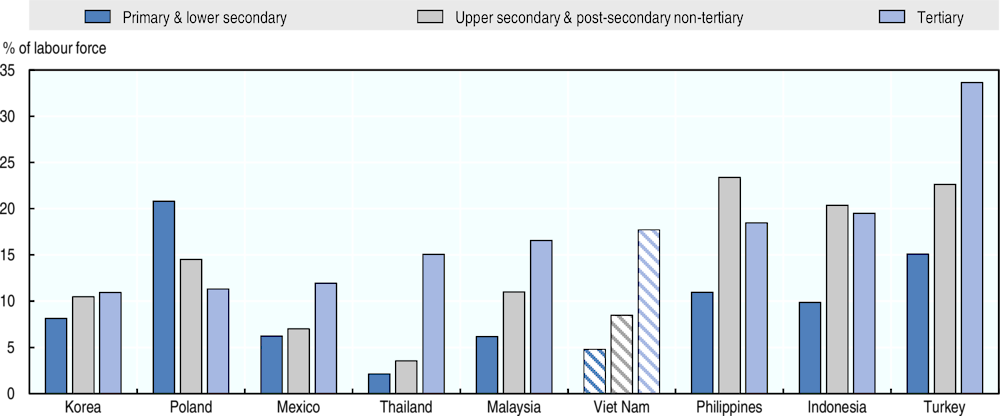

Despite the outstanding performance of basic education in Viet Nam, as measured by OECD PISA scores, there has been little impact in terms of skills development and employability. Employers, particularly those in the most productive industries, often complain of skills shortages, and there is a need for greater investment in vocational training and technical skills (OECD/ERIA, 2018[48]). This is partly reflected in the relatively higher unemployment rate for youth with tertiary education attainment (Figure 2.17). A recent OECD study on the gap between youth aspirations and the reality of the labour market shows that, in Viet Nam, 92% of tertiary educated young people aspire to high-skilled jobs, but only 70% actually obtain them; meanwhile, 7.6% of young people aspire to medium-skilled jobs, but in reality 30% end up in this job category. In order to address this misalignment, national policy makers must focus on a two-pronged strategy to: i) help young people shape career aspirations based on relevant labour market information, so that they do not build unrealistic expectations; and ii) improve the quality of jobs with due regard to the conditions that matter for young people (OECD, 2017[50]).

Figure 2.17. Graduates from tertiary education have relatively poor labour market outcomes

In Viet Nam, 25% of the population fall into the 15-29 age group, and among those aged 25-29 (out of school) only 31% have an upper secondary education or above. In 2014, approximately 56.5% of employed youth had qualifications matching their occupations. The share of over-educated employees was 12.4%, while undereducated workers accounted for 31% of total employed youth. Although the share of well-matched, young employees remained relatively stable between 2010 and 2014, the share of under-qualified employed youth declined by almost 5 percentage points, while the share of over-qualified employed youth increased by nearly 5 percentage points. Over-qualification was found primarily in low-skilled occupations – a consequence of a degree holder being unable to find a job that matches his or her qualifications. Under-qualification was mostly concentrated in jobs requiring higher skills levels. Being under-qualified for a job can have an impact on the self-confidence of the young worker, as well as on labour productivity, stalling economic growth (OECD Development Centre, 2017[51]).

Strengthening the skills of the young population will provide a unique socio-economic development opportunity, especially if the focus is placed on growing economic sectors (OECD Development Centre, 2017[51]). In addition to improving productivity gains, access to skills development for all will ensure that growth is inclusive and that all members of society have the opportunity to succeed.

The informal sector and agricultural activities are also mired in low productivity. Reallocation of workers from the agricultural sector to other sectors, following the modernisation of farming, will boost productivity. Rural development will therefore be important for inclusiveness and social cohesion. Urban policy will also remain a key challenge, in particular ensuring that public services, notably education and social protection, as well as housing, are available to migrant labour.

Partnerships – financing sustainable development

The Partnerships pillar of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development focuses on the mobilisation of resources needed to implement the Agenda, and thus cuts across all the SDGs. It is underpinned by the Addis Ababa Action Agenda, which provides a global framework to align all financing flows and policies with economic, social and environmental priorities (Table 2.3).

Table 2.3. Partnerships – major constraints

|

1. Domestic Revenue Mobilisation: tax revenue is insufficient and the tax structure and administration are in need of simplification and upgrading. |

|

2. The environment is not conducive for private sector investment. |

|

3. The financial sector suffers from a lack of diversification. |

Viet Nam needs to diversify the mix of domestic resources in line with its transition from a centrally planned to a market-oriented economy, and from a low-income to lower middle-income country. The government has anticipated a move away from official development assistance (ODA) and is tapping into alternative sources, notably domestic debt. Increasing tax revenues and broadening the tax base are also important in this regard.

On the expenditure side, Viet Nam’s prudent approach to fiscal management has helped to significantly improve its fiscal position, creating a window of opportunity to engage in the key reforms presented in this report.

On the investment side, Viet Nam could increase the contribution of private sector resources to sustainable development. This would include addressing imbalances between a burgeoning FDI sector and a relatively weak private domestic investment by promoting financial sector development and strengthening the business environment.

Viet Nam has taken a prudent approach to debt management and recently managed to significantly reduce fiscal pressure

Viet Nam has taken a prudent approach to debt management by imposing a statutory debt ceiling of 65% of GDP. The government initiated an ambitious fiscal consolidation programme in 2017 to rein in public spending, and created a new legal framework to tighten oversight of debt management. This has proven very successful with public borrowing slowing between 2016 and 2018. The public debt-to-GDP ratio fell to 61.4% by end-2017 and to 55.5% by the end of 2018 (IMF, 2019[52]).

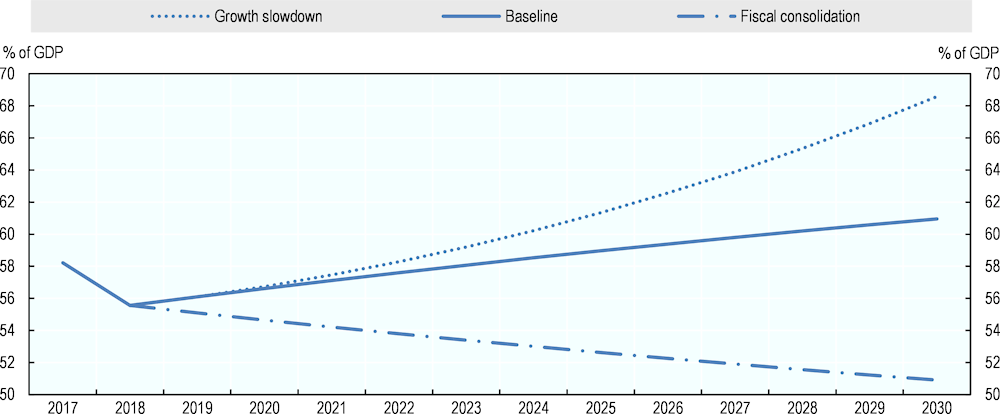

This success in fiscal consolidation places Viet Nam on a more sustainable footing, creating a window of opportunity for reform. Debt sustainability analysis suggests that at the current pace, the debt-to-GDP ratio will remain below the 65% ceiling until 2030 (Figure 2.18); however, a slowdown in growth to the average growth rate of middle-income countries would imply more serious fiscal pressure. Broadening the tax base and strengthening tax collection could help halve the primary deficit from about 2.3% to 1.5% of GDP and, thereby, stabilise the public debt-to-GDP ratio. Revising and improving the quality of public expenditure is also pivotal to fiscal sustainability.

Figure 2.18. Recent fiscal consolidation efforts have significantly strengthened Viet Nam’s position

Note: The nominal growth rate for the baseline and fiscal consolidation scenarios corresponds to the average growth rate over 2014-18, at 9.1%. The interest rate is 5.5% or the average five-year government bond rate for the same period. The growth slowdown scenario assumes that the real growth rate slows to 4.1% (the average real growth rate of upper middle-income countries over 2014-18, and 6.6% for nominal growth rate) towards 2030. Baseline and growth slowdown scenarios assume that the primary deficit is 2.4% and 1.4% in the fiscal consolidation scenario (fiscal effort of 1% of GDP).

Source: OECD calculations based on data from VN General Statistics Office and Refinitiv. Estimates for 2018-19 and projections for 2020-30.

As part of efforts to better control the level of public debt, a new legal framework was created to tighten oversight of debt management. The 2017 Public Debt Management Law has improved governance of debt management by integrating debt management responsibilities into the Public Debt Management Office in the Ministry of Finance, although fragmentation still exists. Moreover, the Law tightens the conditions for government guarantees to public entities by imposing annual limits on government guaranteed loans, and limiting the list of entities that are eligible. Finally, the 2015 State Budget Law imposes debt ceilings for local provinces.

New sources of revenue and new strategies for working with development partners are needed, as Viet Nam’s eligibility for and use of ODA change

Following reforms in the 1980s and 1990s, Viet Nam enjoyed access to official development assistance. In 2016/17, Viet Nam was the 6th largest recipient of ODA with commitments amounting to USD 4.3 billion. However, with the country’s graduation from the International Development Association in 2017 and the Asian Development Bank’s concessional lending window in January 2019, volumes of ODA have started to decrease, while loan terms are expected to become less concessional.

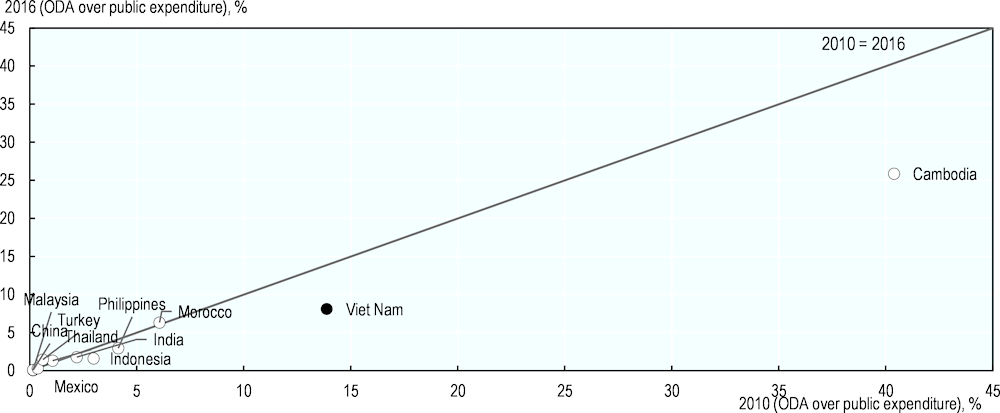

Viet Nam’s reliance on ODA to finance its development has decreased, accordingly: ODA amounted to 9.8% of public expenditure in 2016, down from 12% in 2010. During the same period, only four comparator countries showed a similar decline (Figure 2.19).

Figure 2.19. Reliance on ODA as a way of financing public expenditures has declined compared to other countries

Source: ODA (2019[53]), Credit reporting system; IMF (2019[54]), Government Finance Statistics for Public Expenditure.

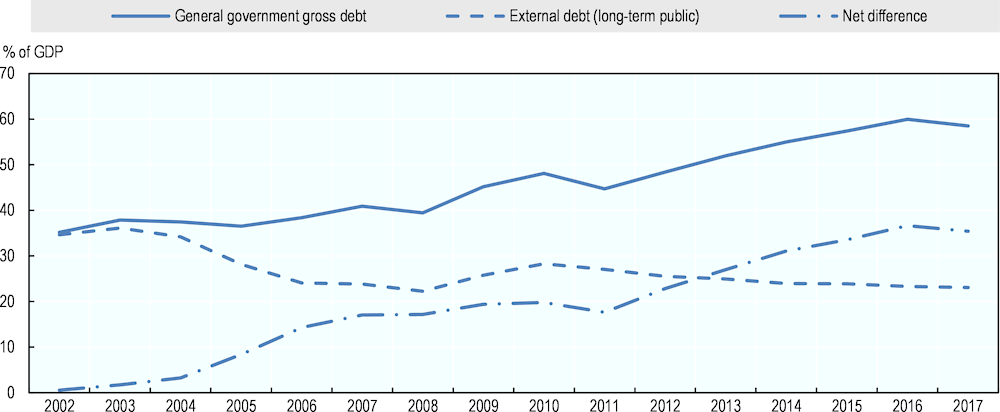

At the same time, demand for official development finance has decreased as Viet Nam increasingly taps into alternative sources. Notably, Viet Nam has developed a domestic bond market, which has grown from around 4% of GDP in 2005, to 13% in 2010, and to 21% in 2018 (see below). As a result, the domestic share of public sector debt has increased significantly (Figure 2.20). The ratio of domestic to external borrowing has thus reversed from 40:60 in 2011 to 60:40 in 2018.

Figure 2.20. The government increasingly raises debt domestically

Note: The net difference in general government gross debt and long-term public external debt functions as a proxy for the domestic component of general government debt.

Source: IMF (2018), World Economic Outlook, www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2018/02/weodata/index.aspx for government gross debt; World Bank (2019), International Debt Statistics, https://data.worldbank.org/products/ids for external debt (long-term public).

However, financing from development partners is still available. While multilateral lenders such as the World Bank and ADB have phased out their ODA assistance, they increasingly provide loans at less concessional terms. Japan and a number of bilateral partners still provide ODA to Viet Nam, albeit at higher terms than in the past, and new players such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) have entered the market. While the diversification of borrowing sources is desirable in itself, it is important that effective and strategic use is made of the resources provided by development partners, which often include embedded technical assistance and transfer of know-how.

Public revenues should be diversified to build up resilience against socioeconomic vulnerabilities

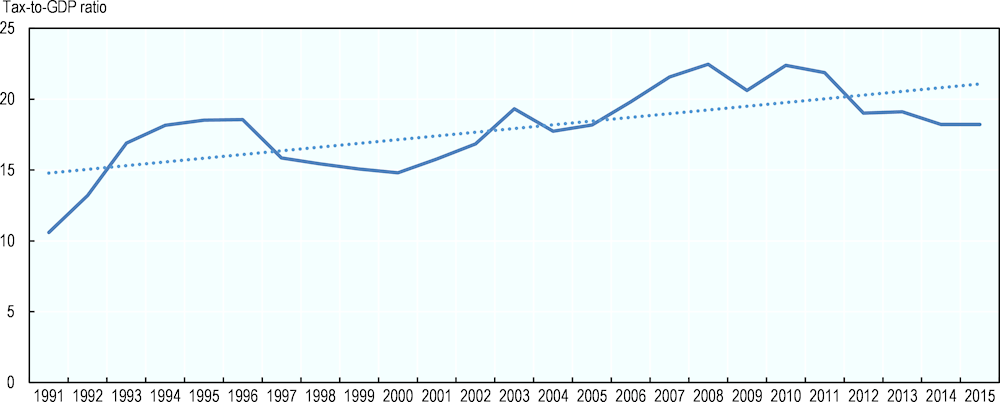

In the 1990s, Viet Nam introduced a comprehensive legal framework to modernise the tax system. Taxes, which previously had been applied differently to the public and private sector, were unified into one integrated system, and standard tax instruments such as value-added tax, and corporate and personal income tax were introduced to systematically mobilise domestic resources. As a result, tax revenue became the main revenue source of the national budget. Tax revenue as percentage of GDP rose from 10.5% in 1991 to 14.8% in 2000 and peaked at over 20% in 2012 (Figure 2.21).

Figure 2.21. Tax revenue as a share of GDP has increased overall due to reforms, but has declined recently

Note: The tax-to-GDP ratio includes (minor) social security contributions.

Source: UNU-WIDER/ICDT (2019[55]), Government Revenue Dataset.

However, in recent years, tax revenue has decreased as a share of GDP, falling to 18.6% in 2018. Several factors have driven this trend. The large size of the informal economy constrains the ability of the government to capture revenues, and a steady reduction in corporate tax rates from 28% in 2008 to 20% in 2017, and a generous system of tax incentives, have further slowed growth in tax revenues.

The downward trend in the tax-to-GDP ratio is of concern, especially considering the demographic pressures that constrain the financial sustainability of the social protection system, explored earlier in the People section. Public expenditures on social services such as education and health, which are crucial to ensure inclusive growth and social cohesion, could be affected by lagging tax performance.

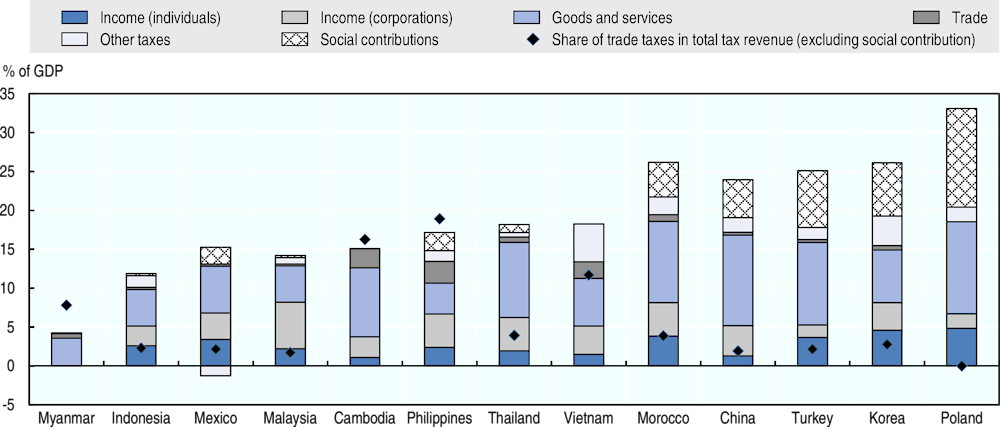

A breakdown of Viet Nam’s tax revenues points to a number of potential paths to improve the tax structure and prepare it for future changes. Personal income tax and indirect taxes on goods and services (VAT or sales tax) generate relatively little revenue (around 43% of revenue between 2015 and 2017, 10 percentage points lower than in China and the average OECD country). Trade taxes accounted for around 12% of revenue between 2015 and 2017 (Figure 2.22). However, Viet Nam’s participation in a range of trade agreements that come with an increasing number of tariff eliminations implies that revenues from trade taxes will decline rapidly. A broader tax base and updated tax structure will thus be essential to finance Viet Nam’s future development needs.

Figure 2.22. Viet Nam’s tax structure relies too much on trade taxes and too little on personal income and indirect taxes

Note: The figure shows the average values by country over 2015-17. Countries are ranked based on their total tax revenues, including social contributions. “Total tax revenues” excludes social contributions.

Source: OECD Revenue statistics for Indonesia, Korea, Malaysia, Mexico, Morocco, OECD average, Philippines, Poland, Thailand and Turkey. UNU-WIDER/ICTD Government Revenue Dataset for the other countries.

The enabling environment can be improved to mobilise private capital and investments

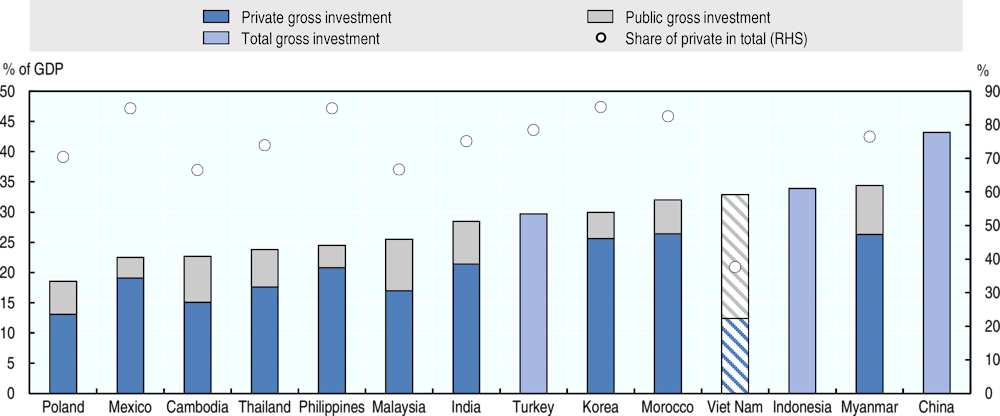

In addition to a re-orientation away from ODA towards domestic sources of finance, Viet Nam needs to transition from a reliance on public towards private resources. Due to constraints on public spending, the government is increasingly looking to the private sector to finance investments that are critical for continued inclusive growth. Private sector promotion was also announced as one of the government’s priorities at the 2018 Viet Nam Reform and Development Forum.

Currently, private investment amounts to 20% of GDP compared to 8% for public investments. The private share of investment is lower than for other comparator countries, with the exception of Cambodia and Malaysia. In light of the fact that Viet Nam has proven highly successful in attracting FDI over the years (averaging 6% of GDP), the relative weak performance of private investment is surprising (Figure 2.23). Removing the FDI component from the private gross capital formation would result in an even less favourable picture.

Figure 2.23. The private sector’s share of total investment is relatively low

Note: The percentages are averages for 2015-17, based on IMF 2019 Article IV and World Bank (2019[2]), World Development Indicators, https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/dataset/world-development-indicators. For Viet Nam, the percentages are averages are for 2015-16, since the 2017 values in IMF 2019 Article IV are only estimations.

Source: IMF Article IV consultations for Cambodia, Morocco, Thailand and Viet Nam. World Bank Gross Fixed Capital Formation for all other countries.

In spite of recent improvements, persistent flaws in the business environment may challenge the mobilisation of private finance. The IFC’s Ease of Doing Business Indicators show a jump in Viet Nam’s score for quality of the business environment (from 82nd in 2016 to 68th in 2017), an improvement linked to the simplification of tax payment and customs clearance procedures (e.g. through the introduction of online filing systems). However, despite improvements, the average time required to pay taxes (rank in ease of paying taxes: 131) and/or complete customs procedures (rank in trading across borders: 100) is still quite long in international terms. Dealing with insolvent businesses remains another challenging area (rank: 133).

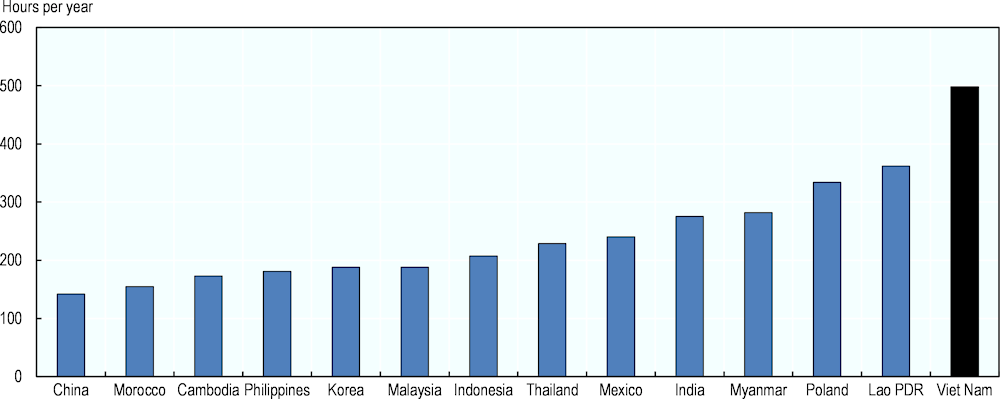

Simplification of tax collection could also boost revenues. Despite progress and the possibility to file taxes electronically, it still take almost 500 hours (equivalent to 12.5. weeks of full-time work) to pay taxes (Figure 2.24). This enormous administrative burden implies ample use of informal short cuts or full tax evasion, even among businesses and individuals that might be willing to pay taxes.

Figure 2.24. The average time required to pay taxes is still long

Source: World Bank (2019[2]), World Development Indicators, https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/dataset/world-development-indicators.

Moreover, overall regulatory quality is still perceived to be low. The Regulatory Quality Index ranks Viet Nam 121st out of 193 countries (World Bank, 2019[2]) (for a more detailed discussion, see Chapter 4). Observers note a general scepticism about the private sector in political and bureaucratic circles and an unwillingness to cater to investor needs and concerns (ADB, 2012[56]). There are also other shortcomings in areas not fully captured by the Ease of Doing Business Indicators. The Peace section and Chapter 4 explore the absence of clear guidance on land ownership rights and usage, as well as a lack of clarity on procedures for land transfers, which are identified as a key concern of investors.

The financial sector needs diversification

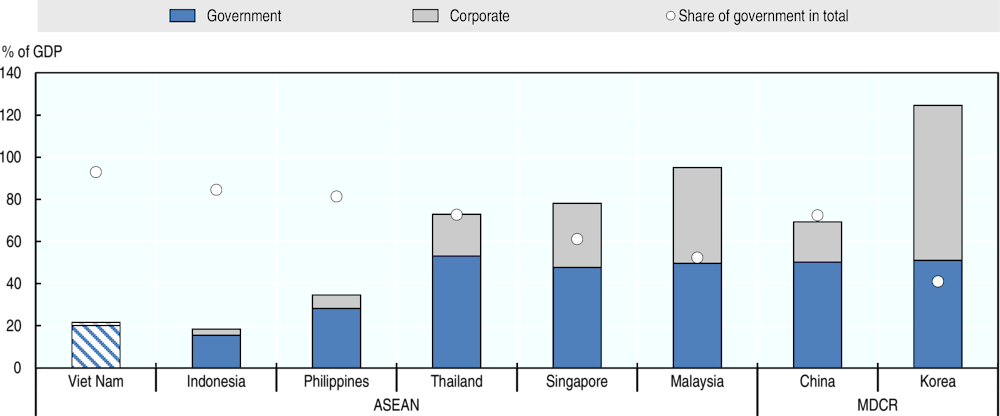

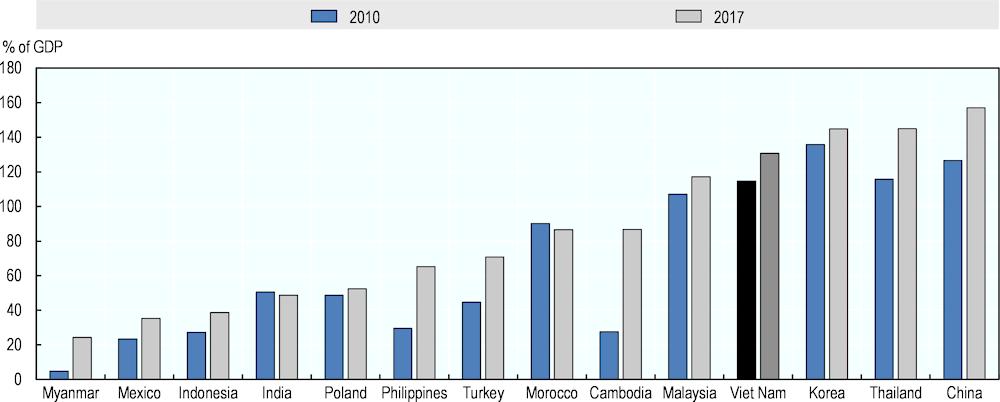

Viet Nam’s financial system is large for a middle-income country, as shown in the high levels of credit extended to the private sector (Figure 2.25). Nevertheless, the financial sector remains bank-centric and dominated mostly by state-owned banks, while non-bank financial institutions are relatively small.

Figure 2.25. Viet Nam is performing well in terms of domestic credit extensions

Source: World Bank (2019[2]), World Development Indicators, https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/dataset/world-development-indicators.

Lagging competition in the banking sector may jeopardise the efficient allocation of resources. The Ðổi Mới reforms have mildly liberalised the sector by limiting the functions of the State Bank of Viet Nam (SBV) – once a central and a commercial bank – to monetary policy and banking supervision, and creating several other state banks. As of 2018, 96 banks operated in Viet Nam, including 7 state-owned credit institutions, 35 joint stock commercial banks, 46 foreign bank subsidiaries, 4 joint-venture banks and 5 wholly foreign-owned banks. Yet, in spite of this increasing diversification, four major state-owned credit banks (SOCBs) account for 45% of banking sector assets and provide half of total credit (IMF, 2017[57]).

This monopoly may be a source of inefficiency. SOCBs tend to open preferential lines of credit for SOEs, conceding low interests and accepting government guarantees that companies without political connections could not afford. According to a survey of Vietnamese enterprises, financial access was the main business environment constraint for SMEs (World Bank Enterprise Survey Database, 2015). Only 29% of small enterprises have an active line of credit, compared to 57% of large firms. This implicitly crowds out potentially more promising private companies that are willing to expand. Without the support of SOCBs, these firms usually re-invest their earnings or rely on informal sources of capital (e.g. “back-alley banks”, trade credits, and money from family and friends) to upgrade (Malesky and Taussig, 2008[58]; Katagiri, 2019[59]). Recently, SMEs have been gaining access to banking services due to rapid innovation in financial technology (especially cashless payments and mobile banking services) (IMF, 2019[60]).

Efforts to strengthen asset quality and bank capital are underway, but vulnerabilities persist. The SBV initiated a series of reforms to mitigate the risk borne by the banking sector, including restructuring, mergers of banks and the enhancement of a legal framework for the management of non-performing loans (NPLs) (IMF, 2019[60]).1 As a result, the ratio of NPL to total gross loans decreased to a record low of 1.9% in the second quarter of 2019.2 Most large private banks are well capitalised to meet Basel II requirements, thanks to more profitable earnings and equity injections from foreign investors (IMF, 2019[60]). State-owned banks, however, have on average a capital adequacy ratio (9.8%) that is just above the minimum threshold set by Basel II and much lower than more solid joint ventures and 100% foreign-owned banks (24.84%). Systemic state-owned enterprises, moreover, face a capital shortfall of 2% of GDP (IMF, 2019[60]).

In addition to having a large banking sector, Viet Nam is also seeing the development of capital markets for corporate equity and other financing tools. Stock market capitalisation amounted to 39% of GDP in 2017, compared to the ASEAN average of 114%. For many companies, including SOEs, transparency and accounting requirements for listing on the stock market can be a burden. The bond market, though growing rapidly, is predominantly tilted towards public sector borrowing (Figure 2.26). Things are changing, however. The creation of credit rating agencies is improving transparency and opening up opportunities on the stock market for large credit-worthy companies; meanwhile, the issuance of corporate bonds is on the rise (IMF, 2019[60]). The swift emergence of Ho Chi Minh City as a sophisticated financial centre is facilitating the trading of corporate securities and venture capital, and could enhance the issue of innovative assets, such as green bonds, which are key to financing the low carbon transition (see Chapter 7).

Figure 2.26. The bond market is predominantly used to raise government debt

Institutional investors could play a pivotal role in building the capacity of a domestic capital market. In developing countries, public and private pension funds, life insurers and sovereign wealth funds usually channel savings into physical and intangible investment needs across all sectors, and could help fill Viet Nam’s infrastructure gap (Della Croce, 2014[61]). At the same time, institutional investors could contribute to stabilising stock return volatility in Viet Nam through the promotion of corporate management expertise and active monitoring of firms in which they invest (Vo, 2016[62]). Currently, around 1% of Viet Nam’s securities markets is made up of institutional investors. Financial and non-financial policies that increase the stability and transparency of the regulatory environment and encourage institutional investment in infrastructure and low-carbon projects are required to attract more institutional investors.

Peace and institutions – strengthening governance

The Peace and Institutions pillar of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development encompasses peace, stability and trust, as well as effective governance and the performance of the public sector more broadly.

Over the last 30 years, Viet Nam has significantly reformed its institutions and legislative framework in order to establish an effective and accountable law-ruled state. However, four main challenges remain: (i) the efficiency and capacity of the public administration; (ii) the unpredictable regulatory framework; (iii) governance of SOEs; and (iv) persistent gift-giving for favours (Table 2.4).

Table 2.4. Peace – major constraints

|

1. The public administration lacks capacity. |

|

2. There is a lack of transparency and predictability surrounding implementation. |

|

3. SOE governance needs reform to improve efficiency. |

|

4. Gift-giving for favours and corruption persist. |

Viet Nam has been modernising its laws and administrations, but informal behaviours continue to be a challenge

The process of economic renovation (Ðổi Mới) initiated in 1986 was accompanied by profound changes to the country’s institutions. Administrative reforms in 1994 represented the first attempt to reduce burdens for businesses and citizens, and were followed in 2001 by the first of several masterplans enacted by the government to improve state efficiency. Then, in 2013, the new Constitution opened up legislative drafting to consultative and participatory policy-making processes (World Bank, 2016[10]).

The simplification of administrative procedures combined with a legislative framework that promoted competition and secured property rights has led to improvement in the business environment. For example, a new law, in effect from July 2019, imposes strong measures against forms of anti-competitive behaviour such as market dominance and economic concentration. Since 1993, the state has also successfully allocated land-use certificates (LUCs), guaranteeing their owners limited rights over their land. In 2005, the government strengthened the protection of intellectual property rights – thus aligning the country with WTO commitments – and raised awareness of the legal and institutional IP protection framework among the business community (OECD, 2018[63]). A 2018 law simplified administrative procedures and introduced other fiscal measures to encourage the development of SMEs (OECD, 2015[64]).

Lack of participation and increasing constraints on liberties raise concerns about the future. A large share of people claim to lack the power or capacity to participate in politics and influence the government, yet consider political freedom to be at least as important as tackling economic inequality. Future trust in institutions may depend on how the state enforces recent controversial laws. For example, the cyber security law that came into effect in January 2019 compels Internet providers to monitor, verify and remove content that could harm public security. There is a risk, however, that the law could be used to limit freedom of speech and punish undesirable public expressions (London, 2019[65]).

Bribery and gift-giving in exchange for favours and advantages continues, in spite of efforts to combat corruption. Since the 1990s, the National Anticorruption Strategy has worked to increase transparency around the income and assets of officials and civil servants, decrease the incidence of corruption among businesses, enhance societal awareness about preventing and combatting corruption, and increase inspections, audits and subsequent punishments for corrupt individuals (Malesky and Phan, 2019[66]). However, the legislative framework remains fragmented and no single independent agency is responsible for pursuing corruption cases. As a consequence, in 2017 Viet Nam placed 109th out of 144 countries in the World Economic Forum’s Irregular Payments and Bribes Index – the same position held in 2010. The World Bank Enterprises survey indicates that in 2015 91% of responding firms assumed that others offered gifts to public officials to ease administrative procedures – by far the highest value among all comparator countries; and 57% admit to giving bribes to receive government contracts (Table 2.5). The “2017 Provincial Competitiveness Index” report by the Vietnam Chamber of Commerce and Industry states that informal payments have become “so ingrained in daily behaviour that it has virtually become a social norm” (Malesky, Phan Tuan and Pham Ngoc, 2017[67]).

Table 2.5. Gift-giving and bribery are more common in Viet Nam compared to a number of other countries

Percentage of firms expected to give gifts to…

|

|

Viet Nam |

China |

India |

Indonesia |

Malaysia |

Mexico |

Morocco |

Myanmar |

Philippines |

Poland |

Thailand |

Turkey |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

2015 |

2012 |

2014 |

2015 |

2015 |

2010 |

2013 |

2016 |

2015 |

2013 |

2016 |

2013 |

|

Public officials “to get things done” |

91% |

11% |

17% |

21% |

38% |

12% |

16% |

16% |

59% |

14% |

18% |

6% |

|

Secure government contract |

57% |

42% |

40% |

33% |

51% |

35% |

58% |

10% |

20% |

19% |

41% |

19% |

|

Get a construction permit |

25% |

19% |

39% |

45% |

47% |

25% |

20% |

48% |

40% |

1% |

33% |

2% |

|

Tax officials |

25% |

11% |

15% |

22% |

24% |

10% |

29% |

20% |

14% |

2% |

9% |

1% |

|

Get an operating licence |

15% |

8% |

26% |

19% |

29% |

18% |

17% |

37% |

10% |

0% |

6% |

10% |

|

Get an import licence |

12% |

19% |

43% |

46% |

41% |

1% |

46% |

26% |

23% |

0% |

0% |

1% |

|

Get an electricity connection |

11% |

3% |

51% |

4% |

1% |

5% |

13% |

36% |

20% |

0% |

15% |

17% |

|

Get a water connection |

5% |

6% |

52% |

1% |

9% |

37% |

7% |

29% |

11% |

0% |

3% |

4% |

Source: World Bank Enterprise Survey 2010-16, a firm-level survey of a representative sample of an economy’s private sector, covering manufacturing firms only.

Bribery aside, in some cases, public officials have other ways to abuse their entrusted authority and realise illicit gains. Powerful groups with narrow self-interests can adopt governance practices that may not be considered illicit or corrupt, but that can still undermine the transparent allocation of resources and equality of opportunities (OECD, 2012[68]). For example, patronage in Viet Nam is a widespread phenomenon. Other examples include the transfer of resources to local governments from the central state according to political allegiances, rather than objective social and economic needs; and easier access to credit and preferential administrative treatment for firms with political connections (Malesky and Taussig, 2008[58]). The state can also extract rents on land transactions without breaking any law.

This section points to three major institutional weaknesses that, if addressed, could enhance the integrity of the public sector: (i) the capacity of the government and public administration; (ii) the predictability of the legislative framework; and (iii) the management of SOEs. Building adequate statistical capacity underlies all these issues, since high-quality and open data are essential to ensuring efficient, predictable and transparent institutions.

Multi-level governance and public administration capacity need improvement

The gap analysis identified three major obstacles to government performance: (i) horizontal fragmentation; (ii) partial decentralisation; and (iii) non-competitive recruitment and remuneration of talent in the Civil Service.

Fragmentation and inefficient public spending

Recent reforms have improved public spending accountability and capacity in Viet Nam. Selected ministries and provinces have harmonised the planning and budgeting process, enhancing the management of information and strengthening the public finance management. For instance, budget execution, accounting and fiscal reporting have become more accurate and transparent thanks to the Treasury and Budget Management Information System. The government has, moreover, restructured budget allocation between central and provincial government, recurrent and capital investment, and within sectors (World Bank; Government of Vietnam, 2017[69]).

Insufficient co-ordination between government agencies continues to hamper effectiveness. For example, fragmented governance affects the effectiveness of the social protection system (as discussed earlier in the People section), environmental regulation (discussed later in the Planet section), and the design and implementation of urban policies. Barriers to co-operation and collaboration include: i) restrictions on sharing information across ministries; ii) different organisational cultures; iii) the division of whole-of-government budget into separate ministerial allocations; iv) public managers who only have experience within a single ministry; and v) accountability structures that focus mainly on ministry-specific issues (OECD, 2018[70]).

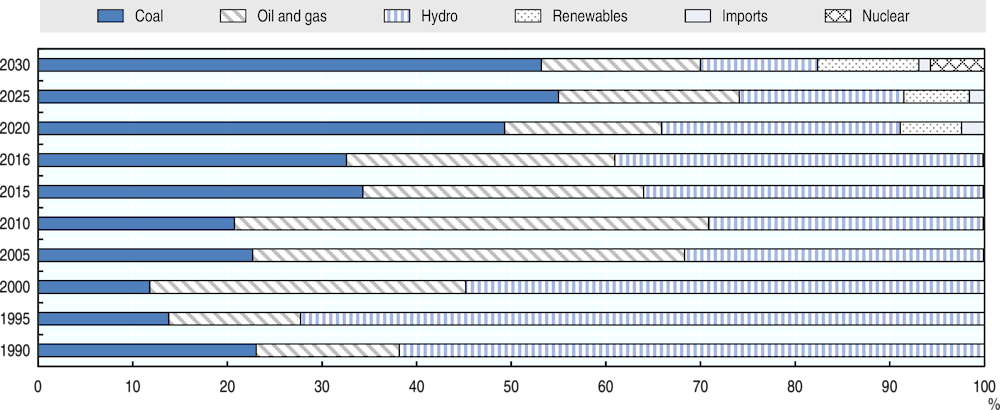

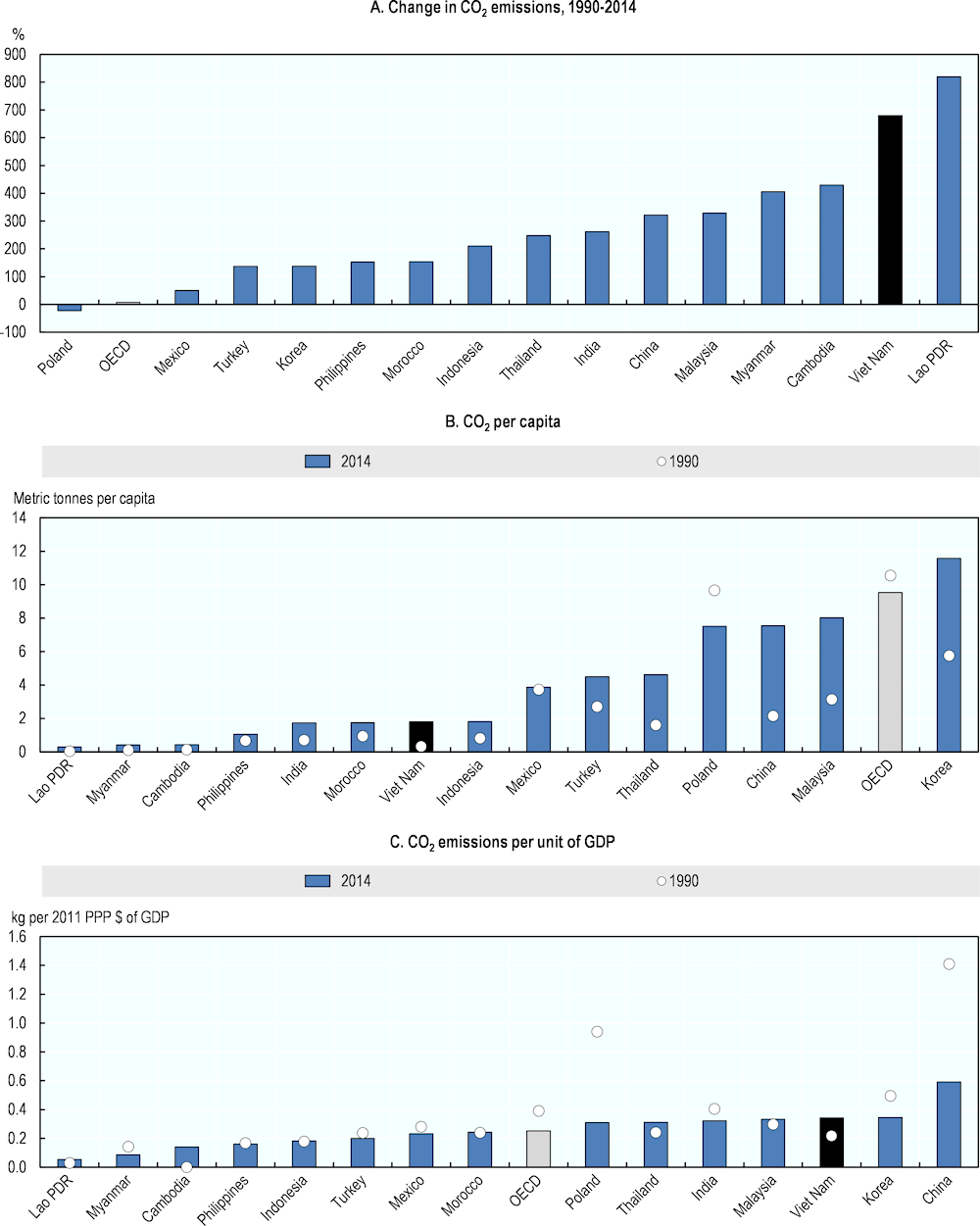

Box 2.2. The organisation of the Vietnamese state