Implementation is everything. Viet Nam’s governance has been an effective driver of development so far. However, in all areas of this report, government management, co-ordination and regulation have surfaced as constraints in all areas of the assessment. The overarching challenge is to achieve sufficient alignment of incentives for all public and private actors towards development and national welfare. Transparent and objective scorecards used as the basis for promotions and territorial reforms could create the conditions for this alignment. Streamlining the legislative process and making the judiciary truly independent are priority policy areas to strengthen implementation. Finally, a reform of the public administration and of the incentives faced by civil servants could further enhance Viet Nam’s capacity to deliver.

Multi-dimensional Review of Viet Nam

8. Strengthening Viet Nam’s capabilities for implementation

Abstract

Implementation is everything. Without it any policy, law or regulation remains just a piece of paper and proof of intentions. Implementation is also the most challenging part of any strategy. Viet Nam has a unique combination of strengths and shortcomings with regard to implementation that this report has brought to the fore.

Since the onset of the Ðổi Mới reforms, Viet Nam has undertaken an impressive number of reforms. It has established the free market as a key principle for running of the economy and has reformed legislation and regulation at a rapid pace in virtually every area of policy. Market reforms and international trade and investment have brought remarkable success and attest to the effectiveness and capability of Viet Nam’s government.

The strategic recommendations of this report relating to future GVC and FDI policies, SOE reform and skills enhancement aim to support Viet Nam’s efforts to maintain this successful trend and make it to the next level of development. However, they also pose challenges for Viet Nam’s current implementation capabilities.

The state controlled by the Communist Party of Viet Nam is at the core of the country’s ability to implement change, both in terms of its regulatory powers and its control of state functions and large parts of the economy through ownership of firms and resources. As the economy becomes increasingly complex and a multi-dimensional perspective of development becomes more important, the state needs to develop in sync, and strengthen its own capabilities for effective implementation and for delegation to and co-operation with other actors.

The overarching challenge is to achieve sufficient alignment of incentives for all public and private actors towards development and national welfare. This applies to both formal and informal rules. Implementation will be pursued effectively if all those responsible perceive implementation to be in their personal and professional interest. Where such alignment is absent, contrary behaviours occur. Corruption is a typical example – it occurs when personal incentives are significantly misaligned with national welfare. However, formal systems can also lead to adverse incentives and ineffectiveness.

Viet Nam faces two sets of challenges to effective policy implementation: informal rules and behaviours and the formal organisation of the state and government functions. Informal behaviours here include corruption and gift-giving for favours, particularly within the public sector. These practices undermine meritocracy on the one hand and effective implementation of policy on the other, as well as trust in institutions. The organisation of the executive, legislative and judiciary at the macro level, and the relationship between the various levels of government at the meso and micro level, may hinder policy implementation and sometimes create scope for capture.

This chapter offers suggestions relating to a number of cross-cutting challenges that affect implementation across all areas of policy. It provides high-level recommendations to increase alignment with performance through transparent performance indicators and the creation of larger subnational units through mergers, enhance judiciary independence, develop legislative capabilities, strengthen Viet Nam’s public administration and intensify the combat against corruption.

Options for increasing alignment with performance in Viet Nam’s governance system

Under Viet Nam’s form of government, the Communist Party of Viet Nam is the supreme institution and controls all three branches of government – executive, legislative and judiciary. The Party’s Central Committee with the Politburo at the centre is at the top of the Party. Membership of the Party’s Central Committee and the Politburo is controlled by these bodies themselves, as are all positions in government. Promotion from lower to higher positions is the main mode of advancement and the core incentive mechanism of both the Party and the government across all levels (Chapter 2, Box 2.2).

The system performs effectively with regard to the implementation of top priorities and allows for experimentation. It has served Viet Nam’s past performance well. Candidates (i.e. cadres in cascading leadership positions at central and provincial level) compete for promotion on the basis of priorities accorded by the top leadership. Decisions over key promotions are made by the leadership and the Politburo, based on available information. In its ideal form this system provides space for and rewards entrepreneurialism in policy reform, as a successful experiment would reward a candidate in terms of positive visibility and promotion (Xu, 2011[1]).

Despite the system’s effectiveness, however, the reliance on top priorities and upward accountability comes with in-built weaknesses that become more pronounced as the complexity of the development challenge increases. Three such effects must be addressed to enable effective implementation of the recommendations made in this report. First, as with any public governance system, the principal-agent problem based on information asymmetry is significant and in its current form creates adverse incentives. Second, the ability to process multiple performance indicators is limited and needs upgrading. Third, the current number and size of subnational government structures is not well adapted to the upward accountability system.

Viet Nam could make transparent and objective scorecards the basis for promotions, in order to address the information asymmetry problem between agents and principals

The first concerns information asymmetry and the principal-agent problem. For many indicators, candidates (i.e. provincial leaders) have significant leeway in shaping the information that filters up to the top leadership. Experience from China, which has a similar governance system, shows that competition works well for indicators that are difficult to manipulate and independently verifiable by the centre, like GDP. However, attempts at quota-based regulation for indicators that are more difficult to observe independently, such as land regulation, were not successful, as the centre did not receive correct information from the provinces and had no means of verification (Xu, 2011[1]).

International comparison shows that the principal-agent challenge also drives the overuse of incentives to attract FDI in upward accountability systems. The amount of FDI received by subnational entities – provinces in the case of Viet Nam – is an important performance indicator evaluated by top leadership for promotion. Incentives such as tax holidays, cheaper land or relaxed environmental requirements can drive up FDI, but have potentially negative fiscal, social or environmental consequences for the province. Such incentives should thus be used sparingly and be well monitored (see Chapter 4). However, they are much easier to implement than incentives that aim to attract investments into underlying drivers of growth, such as skills and infrastructure. Most importantly, it is difficult for the top leadership to fully take into account local conditions and the impact of incentives when they have to compare the performance of various candidates (i.e. various provinces with different conditions). As a result, one-party systems have been shown to provide subnational incentives to foreign investors at a higher rate than countries with other types of governance systems, despite the fact that such incentives are often not necessary to attract investment (Jensen and Malesky, 2018[2]).

The implementation of a strategic approach to FDI attraction, as recommended in this report, would require a change in the evaluation of performance by the top leadership (see Chapter 4 and recommendation 1.4). Performance should no longer be considered simply in relation to increasing FDI, but also in terms of attracting quality FDI, restraint in the use of incentives and the creation of linkages, while respecting environmental restrictions.

However, adding such indicators would increase the information asymmetry problem, as they are more difficult to independently observe than the amount of FDI. It would be difficult for the top leadership to obtain an objective assessment that is sufficiently good to compare provincial performance across a multidimensional FDI attraction framework, as every added dimension would give the local official an asymmetric information advantage over central officials.

The second challenge is closely related and concerns the limited ability of the upward accountability system to credibly process multiple indicators. For the performance evaluation and promotion system to work, that is, to actually induce the desired efforts towards development, candidates must possess a thorough understanding of what does and does not constitute performance. Where this is clear and credible, candidates will invest efforts towards achieving the desired performance. However, as more indicators are considered relevant, the less clear the importance of each single indicator becomes, especially where indicators are in potential conflict with each other.

For example, if economic growth and environment preservation are communicated as targets, each provincial leader will make a judgment as to the relative importance of these two performance objectives, based on what he or she believes to be the preferences of the central top leadership. As environmental protection can present a cost factor or a burden on growth, the environmental protection target will only be considered credible if the top leadership has made a clear commitment signalling that this target is more important than growth. Additionally, the information asymmetry problem applies here, as the central top leadership would need objective information on environmental outcomes for this performance indicator to work. The credible commitment and information asymmetry challenges increase with every additional indicator.

Transparency and public participation in data generation could help address both the information asymmetry and the multiple indicator challenge. A fully transparent set of performance indicators for provinces and ministries, including the weights of each indicator for performance evaluation combined with objective and independent data on them, would allow for a credible commitment by the top leadership. In addition, a public scorecard would enable everyone to compare the performance of provinces and other sub-units and create a fully aligned incentive system for the desired performance if used as the sole basis for promotions. The indicators on such a scorecard would have to be easily and independently verifiable, both by the central leadership and by citizens.

Viet Nam has transparent and objective scorecard systems in place and international examples can provide further guidance. The Provincial Competitiveness Index of the Viet Nam Chamber of Commerce (Malesky, Ngoc and Thach, 2017[3]) and the Provincial Governance and Public Administration Performance Index (UNDP, 2017[4]) can provide the first building blocks. Korea’s ALIO disclosure system (Box 5.7) provides another example of such a transparent scorecard system for the performance management of SOEs, and China’s Green Watch programme (Box 7.9) presents an example for environmental outcomes. As Viet Nam moves ahead, development challenges and obstacles to productivity growth will become more demanding. Effective implementation of the recommendations set out in Part II of this report will need credible commitment on the part of the top leadership to a set of performance indicators for integrated, transparent and sustainable development as the basis for promotions.

Optimising the number of substructures for Viet Nam’s governance system

Upward accountability works best with an optimal number and size of subnational government structures. Two factors need be considered here. First, subnational structures must be of the optimal number and size to balance the positive performance effects of competition with the needs for co-ordination across government units (nationally, the whole should be greater than the sum of its parts). Second, subnational units should be large enough to fully benefit from the potential for learning from experimentation that the upward accountability system offers (Xu, 2011[1]).

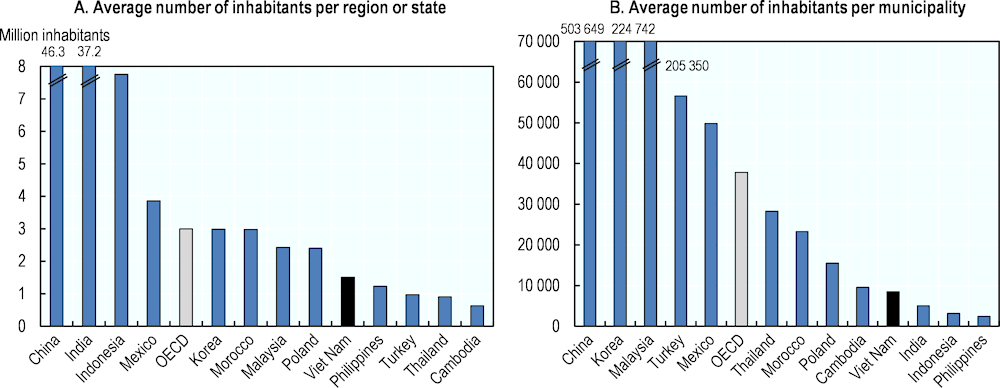

Viet Nam’s current configuration is not optimal on both accounts. Compared to many other countries Viet Nam has a large number of provinces and municipalities each with relatively small populations.1 There are on average 1.5 million inhabitants for each province and 8 500 inhabitants per municipality. These ratios are much smaller than in the average OECD country (3 million inhabitants per region and 37 800 inhabitants per municipality) and in other more populous countries, such as China and India (Figure 8.1), as well as Malaysia and Mexico.

Figure 8.1. Viet Nam has a large number of small provinces and municipalities

The large number of relatively small provinces competing for central visibility on the basis of growth and FDI generates significant inefficiencies in expenditure and inhibits necessary co-ordination. For example, Viet Nam boasts more than 50 major seaports, while 97% of cargo goes through Hai Phong and Ho Chi Minh City (Anh, 2016[6]). Such competition is clearly unhealthy. At the same time, a highway network linking the whole country from North to South would be an important priority for economic development, but has proven very slow to materialise as each province pursues its own objective of maximising growth and investment numbers. These discrepancies are driven by the pressure to signal on key performance indicators to the top leadership.

The system of upward accountability combined with decentralisation of decisions is well placed to optimise the use of policy experiments to create a system for fast learning and continuous improvement (Xu, 2011[1]). However, the small size of Viet Nam’s provinces makes this difficult. The law of large numbers implies that the larger provinces are in terms of population, geographical zones and economic activities, the more comparable they are in terms of the effects of policy reforms. A policy experiment that delivers broad welfare gains in a province home to many different economic activities, will likely do so also in other provinces with many activities. However, a policy that is beneficial in a small province dependent on a few big factories, is not necessarily useful for a province that is largely agricultural. China has greatly benefitted from its ability to incentivise and learn from policy experiments in sizeable sub-units (Xu, 2011[1]). However, Viet Nam’s provinces and municipalities are too small to allow for comparability (Figure 8.1).

Combining provinces into larger regions and merging municipalities would be very challenging, but could significantly boost Viet Nam’s capabilities for effective implementation and learning. Larger regions would be more comparable than small provinces and would facilitate comparison the performance of regional leaders. This would enable a reduction in information asymmetries and work in the favour of the top leadership, which would have better performance information at its disposal as the challenges for candidates would be more comparable. Increasing comparability of performance would also incentivise policy experiments, as the experimenting regional leaders could trust that performance gains from successful experiments would be noticed by the top leadership and be counted towards promotion decisions.

Finally, creating fewer and larger units would significantly reduce expenditure on government structures and free up resources for investment in key strategic priorities. It would also allow for economies of scale and significantly reduce the co-ordination challenge for trans-provincial infrastructure priorities and environmental issues.

International experience shows that the central state needs to take the lead in the consolidation process. Merger reforms may involve significant political bargaining that could in turn inflate the costs of the reform and jeopardise its implementation. Effective implementation of consolidation reforms therefore needs a centrally designed plan for the optimal local administration structure (e.g. detailing the minimum number of subnational units and their average size). Planning should be based on the best available data on fiscal capacities and factors that affect costs, and could be inspired by best practices from around the world.

Consolidation of regions and municipalities is common among OECD and other non-OECD countries. At the regional level, mergers require exceptional political will and buy-in from citizens. France has successfully reformed its territorial organisation and set in place a framework to streamline policy making at the subnational level (Box 8.1). At the municipal level, several waves of forced and voluntarily mergers in Japan (the Great Shōwa from 1953 to 1999 and the Great Heisi consolidation since 2006) drastically reduced the number of municipalities from 9 868 in 1953 to 1 741.

Box 8.1. France experience with territorial reorganisation could help Viet Nam consolidate its provinces

Like Viet Nam, France is a unitary country with three tiers of local government: regions, which are comparable to “provinces” (tỉnh) in the Vietnamese system; “departments” (départements); and municipalities (communes). Until 1 January 2016, there were 27 regions (22 in mainland France), 101 departments and 36 681 municipalities. Local governments were responsible for important functions such as education, social protection, infrastructure, economic development, spatial planning and environment.

In 2013, the French government announced a territorial and decentralisation reform process with three main objectives: the creation of “metropolitan areas” (entities unifying contiguous and highly dense neighbourhoods, irrespective of existing administrative boundaries), redefinition of subnational responsibilities and the fostering of inter-municipal co-operation. The new wave of reforms, moreover, envisaged the forced consolidation of regions. Today, France comprises 13 mainland regions (Law No. 2015-29).

Two of the main objectives of the regional consolidation process are of particular interest for Viet Nam, should the country decide to embark on a similar policy effort. First, the creation of larger and stronger regions was supposed to generate savings and achieve gains in efficiency. Second, larger regions would have sufficient weight to engage in international and inter-regional European co-operation. An ad-hoc law accompanied the reform to clarify and strengthen regional responsibilities (Law No. 2015-991, or the Loi NOTRe – Nouvelle Organisation Territoriale de la République).

Today, French regions have significant power to steer economic development. For example, they are the only body able to define aid schemes for small and medium enterprises at the regional level. Moreover, they are in charge of territorial and environment protection planning, and have regulatory power to adapt national legislation to the local context.

However, greater power comes with tighter requirements. Regions are obliged to draft a regional plan for economic development, innovation and internationalisation (Schéma regional de développement économique, d’innovation et d’internationalisation, or SRDEII), and to set strategic objectives for five-year intervals. They also have to publish regional plans for sustainable territorial development (Schéma régional d’aménagement, de développement durable et d’égalité du territoire, or SRADDET) covering subjects such as territorial planning, transport, air pollution, energy, housing and waste management. These plans are mandatory and prescriptive. Other subnational authorities draft their own plans of development taking into account the SRDEII and SRADDET.

Source: (OECD, 2017[7]).

Strengthening implementation through better rule making and an independent judiciary

For the market economy to fully play to its strengths, it needs strong institutions that allow for transparent rules and rights and credible commitment to their application. To calculate the return to and viability of an investment, investors will want to know with certainty what rules apply to them and to all potential competitors, including public ones and those with connections to the powerful. Two capabilities are vital in this regard.

The first is an efficient legislative and regulatory process that creates transparent and well-designed laws and regulations. Incomplete laws and overlapping regulations create a burden of uncertainty and effort to further investigate, as well as opportunities for exploitation by those in the know. During the preparation of the legislation, evidence-based social dialogues that engage independent think tanks and research institutes could improve the quality of the legislation by highlighting inconsistencies and gaps, testing feasibility, and assessing impact. To enhance the transparency and the quality of the legislation, legal drafts, white papers and related documents should be made publicly available for consultation. The Government E-Portal (http://vanban.chinhphu.vn/), which today gathers all adopted legal text, could expand its scope and serve this purpose.

The second is a qualified and independent judiciary to ensure the equal application of rights and rules. Those with political and regulatory power are the most powerful actors in an economy. It is only by subjecting themselves to the common framework of rules, rights and dispute resolution that they can make their own commitment fully credible. Moreover, an independent judiciary can play an important role in helping to clarify cases of overlapping or contradicting laws and regulations.

Streamlining laws and regulations

Overlapping and unclear laws and regulations have emerged as obstacles to effective implementation across all the strategic themes in this report. Laws adopted by the National Assembly are often incomplete, resulting in the need for multiple partial laws and regulations and decrees that do fully not serve the original intention of the law. For example, Viet Nam tops the number of hours necessary to pay taxes (Chapter 2) due to overlapping tax rules. The same holds true for employment regulation and many other issues relevant to running a business. Lack of coherence among regulations and the need to streamline accordingly is one of the key recommendations of this report to ensure more effective protection of the environment (Chapter 7).

Making the judiciary more independent to ensure the full potential of the market economy

In an independent judiciary, judges and the other members of the court rule on disputes based solely on the evidence presented and the applicable jurisprudence, free from any political interference. In such an impartial setting, no party has an unfair initial advantages or is in a position to shape law enforcement to its own advantage. Citizens, enterprises and government can thus resolve their disputes fairly. Through its impartiality, an independent judiciary generates trust in the rules and regulations upon which it adjudicates.

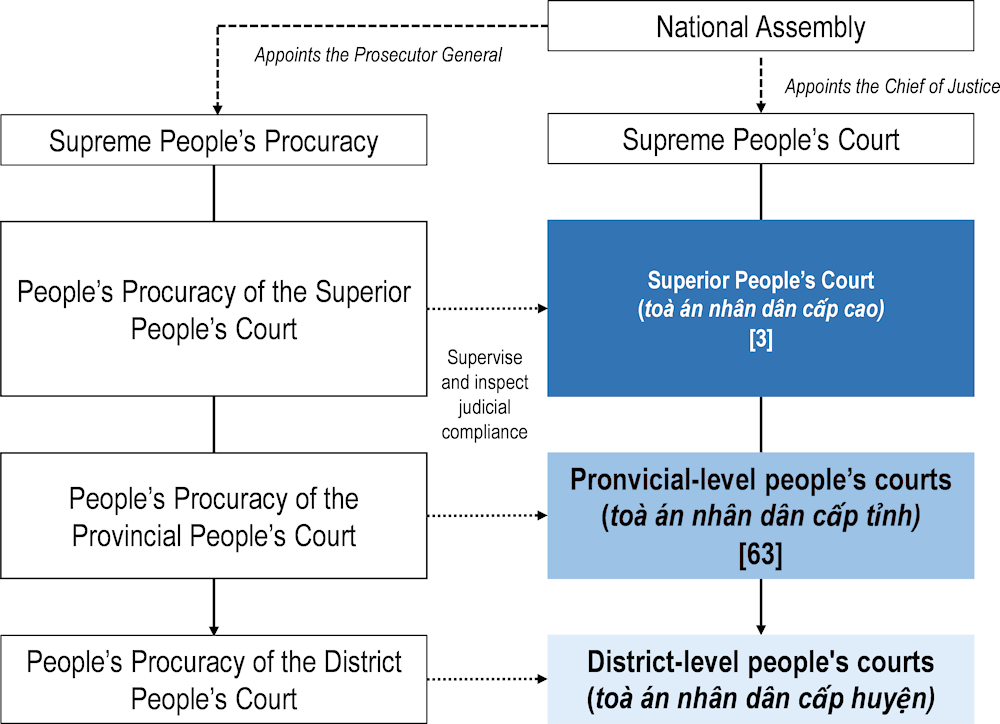

Viet Nam has been strengthening judicial independence since the beginning of the 1990s. The 1992 Constitution and the 2002 Law on the Organisation of People’s Courts, in particular, established the independence of courts from government influence and personal interests. The 2014 Law on the Organisation of Courts simplified the previously dispersed judiciary system and centralised the “cassational power” (giám đốc thẩm) into a single Supreme Court, whose role now is to guide lower courts and the development of jurisprudence. To this end, it introduced three Superior (or High-level) People’s Courts, responsible for the North, Centre and South regions, which review appeal decisions of trials originating in provincial courts. Provincial courts, in turn, can also review cases sentenced by judges at the district level (Figure 8.2).

Figure 8.2. The Vietnamese judiciary has four layers with power centralised in the Supreme People’s Court

Note: The Superior People’s Courts is an appellate court; the district-level people’s courts are trial courts; the provincial-level people’s courts are both appellate and trial courts.

Source: Author’s elaboration based on the Law on the Organisation of People Courts, 2014, Article 3.

Since the beginning of the 2000s, Viet Nam has significantly strengthened local dispute resolution mechanisms in order to enhance judiciary independence and thus attract investments. The credibility of these mechanisms is indeed essential to enhance trust between potential business partners and facilitate contracts with foreign business actors. Beginning in 2003, Viet Nam created local arbitration forums for dispute resolution; the 2010 Law on Commercial Arbitration (LCA) then opened the door for contract dispute resolution outside of the courts. Today, there are 25 operating arbitration centres, and the share of firms interested in using them has risen from close to 0% in 2012 to 35% among domestic firms and 18% among foreign firms in 2018 (Malesky, Ngoc and Thach, 2017[3]). The largest arbitration centre, the Vietnamese International Arbitration Centre (VIAC), handled 180 cases in 2018, half of which involved foreign parties, together totalling USD 63 million, with the largest dispute worth approximately USD 24 million (Malesky and Milner, 2019[8]).

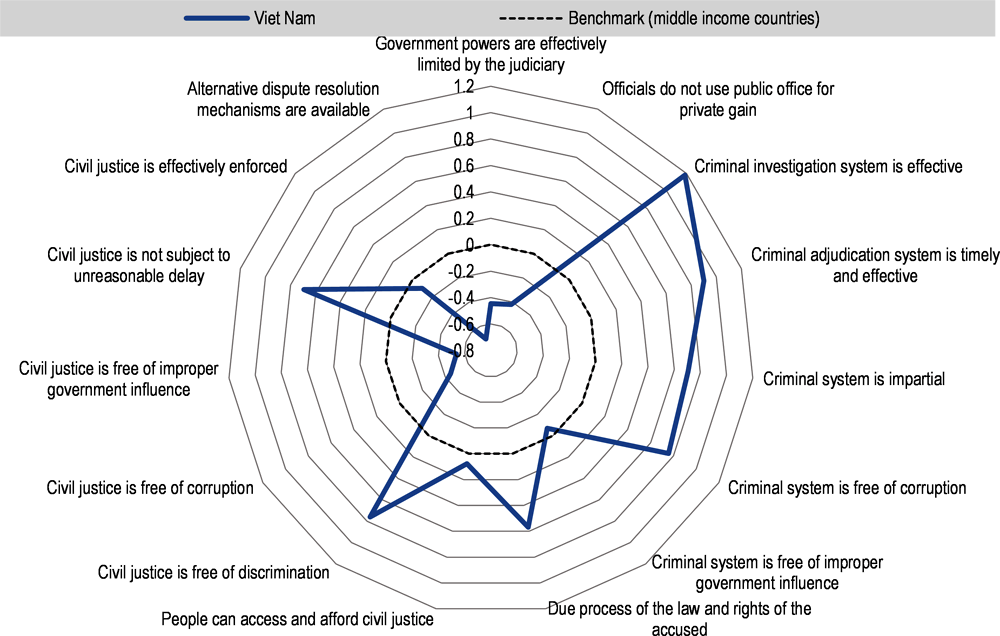

However, beyond these dispute resolution mechanisms, judicial power still lacks independence. Analysis of several dimensions of judiciary independence indicates that courts in Viet Nam seem to underperform with respect to other middle-income countries. The enforcement of civil law remains biased and is subject to significant interference from the executive power and other groups of interest (Figure 8.3). This undermines the commitment framework necessary for the market economy and reduces incentives for investment.

Figure 8.3. In spite of numerous reforms, the judicial power of Viet Nam lacks independence

Note: The observed values falling inside the black dotted circle indicate areas where Viet Nam performs poorly in terms of what might be expected from a country with a similar level of GDP per capita. Expected well-being values are calculated using bivariate regressions of various well-being outcomes on GDP, using a dataset of middle-income countries. Indicators are then normalised in terms of standard deviations across the panel.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on the World Justice Project Database (accessed in December 2019).

The following two reforms are priorities to achieve complete judicial independence and enhance the efficiency of the judiciary.

First, judges need to become accountable purely to the law and their appointment needs to be based on competence alone. At present, judges, as part of the system of jurisprudence, must follow the guidelines and policies of the Party (Resolution No. 08-NQ/TW dated 2 January 2002 of the Politburo “On Forthcoming Principal Judiciary Tasks”). Political training plays an important role in application dossiers, with aspiring judges needing to demonstrate “strong political spirit” (bản lĩnh chính trị). Appointments should instead be conditional on passing a standardised national examination, organised by the Ministry of Justice and open to all. The exam should test candidates’ technical knowledge of the law and their competency to apply it. The results of the examination should be public and accessible.

Second, reforming the tenure of judges is crucial. Currently, the tenure is limited to five years and re-appointment cannot be obtained without a new application, thus impeding career-concerned judges from operating freely. The appointment of the judiciary should in principle have no term limit. Probation periods could be introduced for young candidates, but final appointment should be dependent solely on the skills and capacity of each judge rather than their allegiances. The power of dismissal should be strictly regulated and given to a dedicated commission composed of experts from the central and local level.

Beyond judicial independence, Viet Nam could consider setting up a judicial process to resolve contradictions between laws, resolutions and decrees. One law spawns on average 17 circulars (Thanh and Nguyen, 2016[9]) creating ample space for overlap and inconsistencies with the original intention of the law. A constitutional court could serve as an instance of appeal in such situations and help clarify Viet Nam’s body of legislation. The Supreme Court could be tasked to play this role. During a transition phase, selected areas of legislation could be opened to review by the Supreme Court, if called on to do so by a party.

Strengthening Viet Nam’s public administration for effective implementation

Effective implementation of policy depends on capable politicians and public officials working towards the common good and national development. This requires intrinsic motivation on the part of officials, but also a meritocracy that rewards capacity and skill. Where the system is undermined through favouritism and corruption, the quality of the public service suffers and the motivation for excellence and the common good will be replaced by selfishness, mediocrity and the favouring of special interests. This weakens the state’s ability to implement policy and reform, undermines trust in institutions and ultimately derails development.

Viet Nam struggles with corruption, relationship-based favouritism and gift-giving for favours inside state institutions, and needs to find solutions to these challenges (see Chapter 2). Interviews with officials conducted for this report suggest that appointment or promotions may be contingent on bribery. This could create incentives for further corruption (Malesky and Phan, 2019[10]).

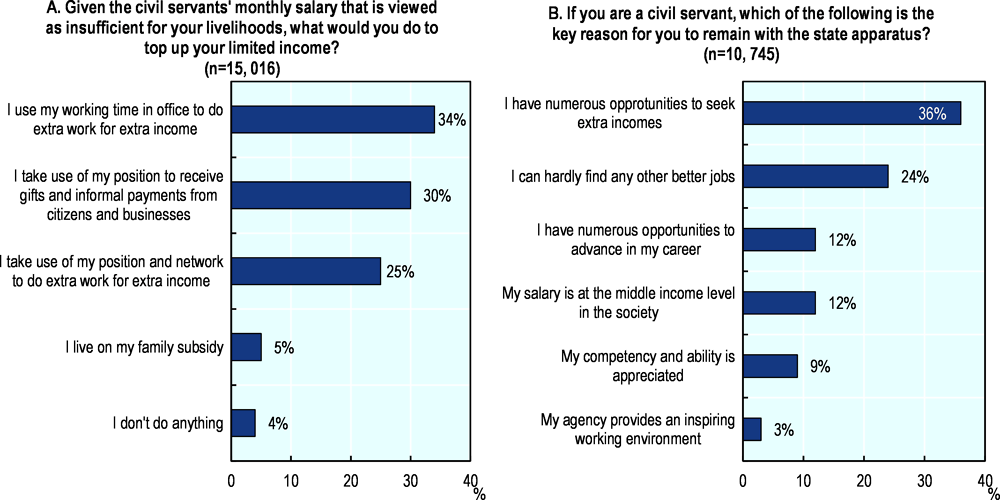

Both push and pull factors must be addressed and some suggestions are made here. First, the official pay for bureaucrats and politicians is very low relative to living costs in major cities, exerting pressure on them to increase the income from other sources. This can stem from corruption and bribery in some cases. This needs to be improved. Second, increased rotation of officials between provinces could help diminish the impact of local networks and favouritism. Third, a broader anti-corruption drive needs to be strengthened and applied more uniformly.

Improving remuneration to eliminate the need for officials to generate unofficial income

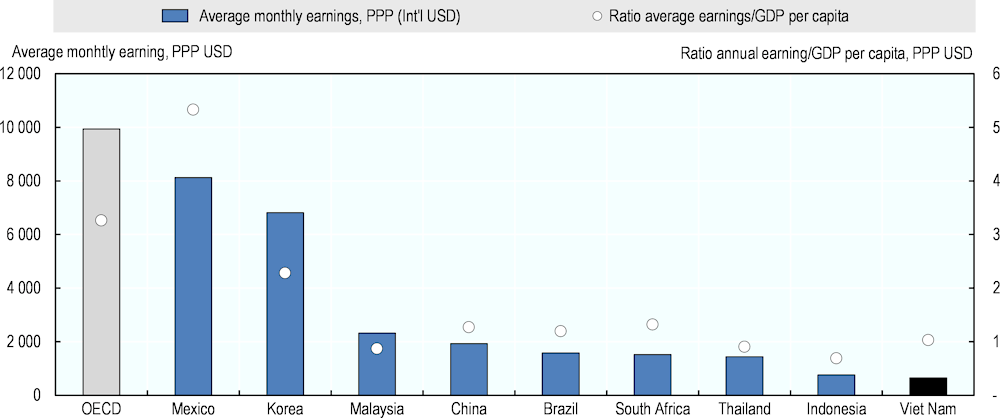

Current salaries for civil servants are low and their progression is not always meritocratic. The basic salary increased eightfold between 1999 and 2019, and currently amounts to VND 1 490 000, or USD 160 (in PPP).2 Numerous allowances are then added to the basic salary to compute the final monthly earnings, which on average amounted to USD 654 (in PPP) in 2018. This value is in line with the GDP per capita and the average monthly salary in the manufacturing and service sectors (USD 649, in PPP). However, it is much lower than in OECD countries and other non-OECD countries (two times lower than in Thailand and three times lower than in China) (Figure 8.4). The allowances, which account for a large part of the final earnings, are determined by decrees rather than performance. Based on interviews and anecdotal evidence, the resulting progression of salaries is not always meritocratic.

Figure 8.4. Public officials’ average monthly earnings are very low compared to OECD and other non-OECD countries

Note: Average monthly earnings include wages and salaries, and employers’ social contributions. For OECD countries, the value has been computed as the average earning of senior and middle managers, senior and junior professionals, and employees in service delivery occupations. For all other countries, salaries for employees in “Public administration and defence; compulsory social security” (ISIC version 3, section L) are considered. Values for China, Indonesia, South Africa, Thailand and Viet Nam are from 2018. Values for China refer to the average earning of employees in non-private sectors. Values for Brazil, Korea, Mexico and the OECD are from 2015.

Source: OECD Government at a Glance Database (2017 edition), ILOStat, CEIC Data, Labour Force Survey Viet Nam (2018).

Low earnings and an insufficiently meritocratic system of salaries hamper the quality of the public administration. Qualified civil servants are leaving government agencies for better-paid jobs in the private sector (Box 8.2). Some of those who remain choose to increase their income through other activities, both formal (e.g. other remunerated activities during working hours) and informal (e.g. eliciting bribes and gifts from citizens, businesses or other public officials) (Figure 8.5). Moreover, the lack of an official mechanism to attract mid-level and high-level talents - who can hence join the civil service only at the entry level - further hamper the quality of the public administration.

Box 8.2. Brain drain of civil servants to the private sector

During 2003-07, more than 16 000 civil servants voluntarily left government agencies. The total figure for Ho Chi Minh City is 6 400. The most competent state employees are leaving for private and foreign companies where they are much better paid. In the past, leavers were often job entrants or low-level staff. Today, managers and even senior managers comprise the majority of civil servants leaving state agencies. Government agencies such as the State Bank of Vietnam, the Ministry of Finance and the State Security Commission are the worst victims of the “brain drain”, as the demand for skilled labour in the finance and banking sector has risen recently. A study on “public service careers” conducted by the National Academy of Public Administration surveyed a sample of 500 civil servants working at the central and local levels. According to the survey, the main reasons for leaving government agencies included ineffective remuneration and lack of incentives and opportunity for development. The most popular reasons for working as a public servant are the job itself and job security.

Source: (Poon, Hùng and Trường, 2009[11]).

Figure 8.5. Incentives to remain in the public sector might not necessarily include the official salary

The government is planning to reform the salary system and revise the number of civil servants to tackle these issues. The base salary will increase by 7% per year until 2020. Starting from 2021, the pay structure will become simpler: the salary will be a lump sum based on the employee’s grade (and not on the existing complicated system of coefficients) and allowances will be limited to about 30% of the total amount. The government aims at reducing the number of civil servants by at least 10% compared to 2015, and at making the salary in the public sector approach that of the business sector.

This is a first good step but the overall increase in remuneration would have to be significantly larger than that offered under the current reform. Only a level of pay that allows for a somewhat comfortable quality of life will be credible as a means to combat corruption.

To facilitate a more significant increase in pay than planned, the government first needs to create order in the pay system and gain control over the payroll. For example, a number of parastatal organisations represent a significant drain on public resources, but the central state has no precise figures about the size of this type of workforce. Only a significant reduction in the number of recipients on the public payroll would create the fiscal space necessary for the increase in remuneration.

Rotation mechanisms could help improve the efficiency of the public administration

Rotating provincial leaders and cadres could help better aligning incentives by cutting the link between local politicians, state-owned enterprises and businesses. In 2012, only 8 out of 63 provincial party secretaries and two chairpersons of the Provincial People’s Committees had no pre-existing ties to the province to which they were assigned, while around 70% of senior provincial officials served in their native province. This is in stark contrast to China, where only 18% of provincial leaders served in their native province in 2010 (Pincus, 2015[13]).

A rotation strategy for public employees, not least at the higher hierarchical levels, is essential to avoid collusion for group benefits. Assigning public employees to offices from their area of origin for a certain time might allow them to communicate more effectively, tap into local knowledge and give them greater intrinsic motivation to perform well. However, this same advantage might provide opportunities for private gain or putting local interests above the national interest, thereby increasing the chance of collusion among public employees (Box 8.3).

Box 8.3. The rotation mechanism for civil service selection in India has increased overall public administration performance

In India, the Indian Administrative Service (IAS) is an elite civil service recruiting those who occupy key positions critical for policy implementation. Entry into the IAS is highly competitive and takes place via the Civil Service Exam, which is organised annually by the Union Public Service Commission (UPSC). In 2015, for example, 465 882 UPSC entrants competed for just 120 IAS slots.

The allocation of officers follows a strict rules-based procedure consisting of the following three steps:

Step 1. Candidates apply to become IAS officers and declare their preference to remain in their home state (referred to as “insider candidates” as opposed to “outsider candidates”).

Step 2. The overall number of vacancies and the corresponding quotas for “insider candidates” are determined.

Step 3. Vacancies and officers are matched based on the score obtained at the UPSC entry exam and the number of available vacancies. At this stage, the preference for home assignment indicated in the first step is taken into account.

“Insider candidates” are distributed based on the preferences indicated in Step 1. If the number of insider candidates is higher than the number of vacancies available in a certain area, the higher-ranking “insider candidates” are given priority.

“Insider candidates” that have not been assigned to their unit of preference and “outsider candidates” are then allocated according to a rotating roster system.

Under this system, candidates from weak institutional environments are more likely to be assigned to other administrative units than their preferred ones (Xu, Bertrand and Burgess, 2018[14]), using data on performance indicators collected from 1989-2012). This system for the selection of public officials contributes to improving the overall efficiency of civil servants in India.

The government has issued Resolutions in 2002 and 2017 outlining the appointment of “non-locals” as provincial and municipal leaders. In 2012, it committed to appoint at least 25% “non-local” provincial leaders and 50% district leaders by 2015. However, over the period 2010-15, only 22% of provincial leaders and 38% of district leaders did not come from the administrative unit to which they were appointed. Targets alone are thus not enough. Viet Nam needs a comprehensive mobility system with a clear mechanism that weighs civil servants’ preferences for home-based assignments against the efficiency gains that mobility would yield.

Mobility programmes can also be temporary and offer civil servants opportunities to work outside of their home organisation, develop new insights and build new skills. Such programmes would give individuals a more horizontal understanding of policy issues and allow them to look at things from outside the perspective of their sector or administrative unit (OECD, 2017[15]).

Committing to fight corruption to combat the monetisation of authority

Viet Nam has so far invested significant effort and resources in combating corruption. Six waves of reforms have built the current National Anticorruption Strategy, which defines bribery, sets regulations and imposes sanctions. The strategy aims at increasing the transparency of officials’ and civil servants’ income and assets, curbing corruption incidence among businesses, increasing inspections, audits and subsequent punishments for corrupt individuals, and enhancing societal awareness to prevent and combat corruption (Malesky and Phan, 2019[10]).

Nevertheless, Viet Nam has not improved its position in international rankings. The country placed 109th out of 144 countries in the World Economic Forum’s Irregular Payments and Bribes 2017 Index (it placed 100th in 2010) and 117th out of 181 countries in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions 2018 Index (it placed 110th in 2011).

Unprecedented anti-corruption efforts need deeper institutional reforms to have durable consequences. Recent Decree No. 59/2019/ND-CP dated 1 July 2019 on “Detailed Regulations on Anti-corruption Law” provides details about the implementation of Viet Nam’s new anti-corruption law and marks the latest milestone in the country’s long fight against corruption. However, the government has only started to design institutions that emphasise prevention and address the conditions for corruption rather than simply reacting to it. Moving forward, an independent anticorruption board or measures to shield the Communist Party’s Anticorruption Commission from internal political dynamics could help. Moreover, reforms of the state governance and the public administration could help uproot the type of corruption that has increasingly affected citizens and businesses.

Recommendations to strengthen Viet Nam’s capabilities for implementation

The following table summarises the key recommendations to improve the capacity of Viet Nam to deliver reforms. The recommendations are the results of consultations and interviews carried out by the OECD team with public officials, scholars and academics.

Table 8.1. Recommendations to strengthen Viet Nam’s capabilities for implementation

|

High-level recommendations |

Detailed recommendations |

Key performance indicators |

|---|---|---|

|

5.1. Increase the alignment of Viet Nam’s governance system with performance |

5.1.1. Address the information asymmetry problem between levels of government: Introduce transparent and objective scorecards as the basis for promotions. |

• Number of Provincial Committees adopting scorecards to evaluate overall provincial performance. |

|

5.1.2. Optimise the number of substructures in Viet Nam’s governance system, for example, by consolidating and amalgamating provinces and municipalities. |

• Number of regions/provinces. • Average population by province. • Average population by municipality. |

|

|

5.2. Strengthen implementation through better rule making and an independent judiciary |

5.2.1. Streamline laws and regulations by: • supporting evidence-based social dialogues between the state and independent think tanks and research institutes; • better communicating policy intention by making legislative texts publicly available. |

• Ratio Resolution (Nghị quyết)/Law (Luât). • Ratio Decrees (Nghị định)/Law (Luật). • Ratio Decisions (QD.TTg)/Law. • Ratio Circulars (Thông tư)/Law. • Ratio Executive decisions (Vb điều hành)/Law. • Number of draft laws, white papers and related documents updated on the Government E-portal. |

|

5.2.2. Make the judiciary more independent to achieve the full potential of the market economy by: • introducing a standard national test for the selection of judges; • extending the duration of judicial appointments. |

• Number of judges selected through national tests. • Duration of judicial appointments. • Share of respondents finding civil justice free from improper government influence, based on the World Justice Project. |

|

|

5.3. Strengthen Viet Nam’s public administration for effective implementation. |

5.3.1. Improve salaries by simplifying the current structure and tightening progression to experience and performance, rather than seniority and age. |

• Ratio average salary/basic salary • Salary midpoint and variation by career step. • Salary differential between salary midpoints of adjacent career steps. |

|

5.3.2. Downsize public sector employees, including those employed by parastatal non-governmental organisations on the state’s payroll. |

• Number of employees in national and subnational government agencies. • Number of employees in national and subnational parastatal institutions. |

|

|

5.3.3. Introduce a mechanism of rotation of civil servants between provinces. |

• Share of civil servants who come from the province where they serve, by province (average value). |

|

|

5.3.4. Establish an independent anticorruption board or enhance the independence of the Communist Party’s Anticorruption Commission from external influences. |

• Corruption perception index. • Share of respondents finding that officials do not use public office to extract private rents, based on the World Justice Project. • Share of respondents finding criminal justice free from improper government influence, based on the World Justice Project. |

References

[12] Acuña-Alfaro, J. (2012), Incentives and Salaries in Vietnam’s Public Sector, UNDP.

[6] Anh, V. (2016), “Vietnam: Decentralization amidst fragmentation”, Journal of Southeast Asian Economies, Vol. 33/2, pp. 188-208.

[10] Chen, C. and M. Weiss (eds.) (2019), Rust Removal: Why Vietnam’s Historical Anticorruption Efforts Failed to Deliver Results, and What that Implies for the Current Campaign, State University of New York Press, Albany.

[9] Gill, D. and P. Intal (eds.) (2016), Regulatory Coherence: The Case of Viet Nam, ERIA Research Project Report 2015-4.

[2] Jensen, N. and E. Malesky (2018), Incentives to Pander: How Politicians Use Corporate Welfare for Political Gain, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/9781108292337.

[8] Malesky, E. and H. Milner (2019), Credible commitments for investors: International agreements and domestic law in Vietnam, Princeton, NJ.

[3] Malesky, E., P. Ngoc and P. Thach (2017), The Vietnam Provincial Competitiveness Index: Measuring Economic Governance for Private Sector Development, Final Report, Vietnam Chamber of Commerce and Industry and United States Agency for International Development: Ha Noi, Vietnam.

[5] OECD (2020), “Subnational government structure and finance”, OECD Regional Statistics (database), https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/05fb4b56-en (accessed on 28 January 2020).

[7] OECD (2017), Multi-level Governance Reforms: Overview of OECD Country Experiences, OECD Multi-level Governance Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264272866-en.

[15] OECD (2017), Skills for a High Performing Civil Service, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264280724-en.

[13] Pincus, J. (2015), “Why Doesn’t Vietnam Grow Faster? State Fragmentation and the Limits of Vent for Surplus Growth”, Southeast Asian Economies, Vol. 32/1, p. 26, http://dx.doi.org/10.1355/ae32-1c.

[11] Poon, Y., N. Hùng and D. Trường (2009), The Reform of the Civil Service System as Viet Nam moves into the Middle -Income Country Category, https://www.undp.org/content/dam/vietnam/docs/Publications/25525_3_CivilServiceReform.pdf.

[4] UNDP (2017), The Viet Nam Provincial Governance and Public Administration Performance Index 2017 - Measuring Citizens’ Experiences, United Nations Development Programme, Hanoi.

[1] Xu, C. (2011), “The Fundamental Institutions of China’s Reforms and Development”, Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. 49/4, pp. 1076-151.

[14] Xu, G., M. Bertrand and R. Burgess (2018), Social Proximity and Bureaucrat Performance: Evidence from India, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, http://dx.doi.org/10.3386/w25389.

Notes

← 1. Because of their role in Viet Nam’s territorial governance, provinces and municipalities are classified as Territorial level 2 (TL2) and Territorial level 4 (TL4), respectively, according to OECD classification.

← 2. The current system is the outcome of four waves of reforms (in 1960, 1985, 1993 and 2003), and a fifth one is underway. Since 2013, the National Wage Council has advised the government about the minimum wage to be set for public and private workers. This council has 15 members: five representatives from the Ministry of Labour Invalids and Social Affairs, five from the Viet Nam General Confederation of Labour, and five others representing employees at the central level.