This chapter covers Poland’s Medical Diagnostic Centre (MDC), a primary care model for patients with chronic conditions. The case study includes an assessment of MDC against the five best practice criteria, policy options to enhance performance and an assessment of its transferability to other OECD and EU27 countries.

Integrating Care to Prevent and Manage Chronic Diseases

8. Medical Diagnostic Centres, Poland

Abstract

Medical and Diagnostic Centre (MDC): Case study overview

Description: MDC is a primary care model for patients with chronic conditions. Patients who access MDC obtain an Individual Medical Care Plan based on a comprehensive assessment by a GP. Results from the comprehensive assessment are used to stratify patients into risk groups, which helps health professionals proactively manage patient needs. Following the comprehensive assessment, patients receive care by a multidisciplinary care team, which is co‑ordinated through a case manager. MDC resembles a new model of primary care growing increasingly popular amongst OECD countries.

Best practice assessment:

OECD Best Practice assessment of MDC

|

Criteria |

Assessment |

|---|---|

|

Effectiveness |

The average number of GP and specialist visits did not grow despite an increase in the average age of an MDC patient. Given older patients require more care, these results indicate, but do not confirm, MDC reduces demand for care. An evaluation of similar pilot studies in Poland found patients who access this type of care report better experiences and outcomes. This did not translate into a reduction in secondary care utilisation. |

|

Efficiency |

There is no data on the efficiency of MDC. Evidence from the broader literature indicate primary care models such as MDC reduce unnecessary treatment and thereby costs |

|

Equity |

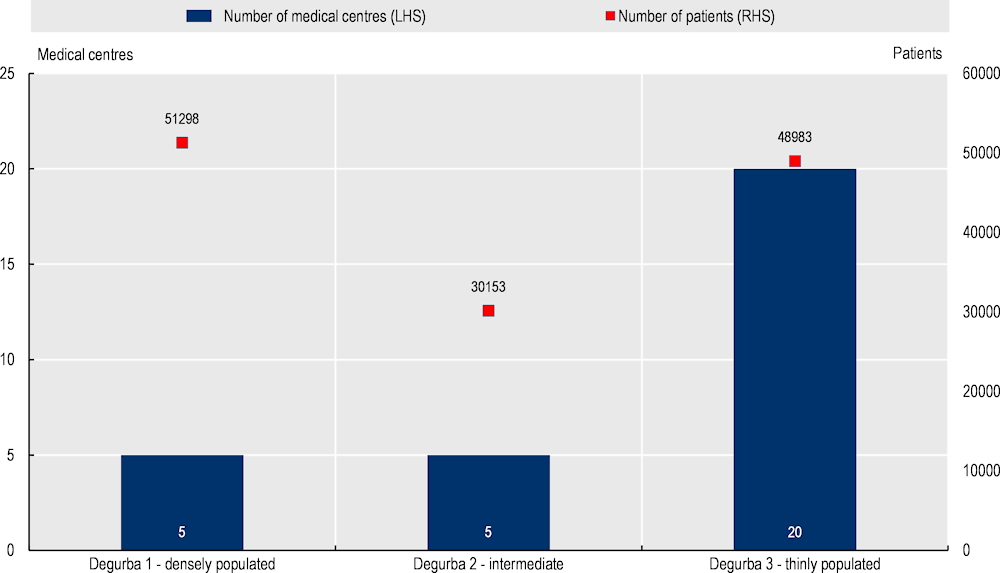

More than half (61%) of all MDC patients are located outside urban areas, including a large proportion of people in thinly populated areas. MDC therefore plays a key role in reducing access inequalities. |

|

Evidence‑base |

Changes in healthcare utilisation of MDC patients was measured using repeated cross-sectional data for MDC patients only. Given there was no control group nor a process to control for confounding factors, the change in utilisation cannot be directly attributed to MDC. |

|

Extent of coverage |

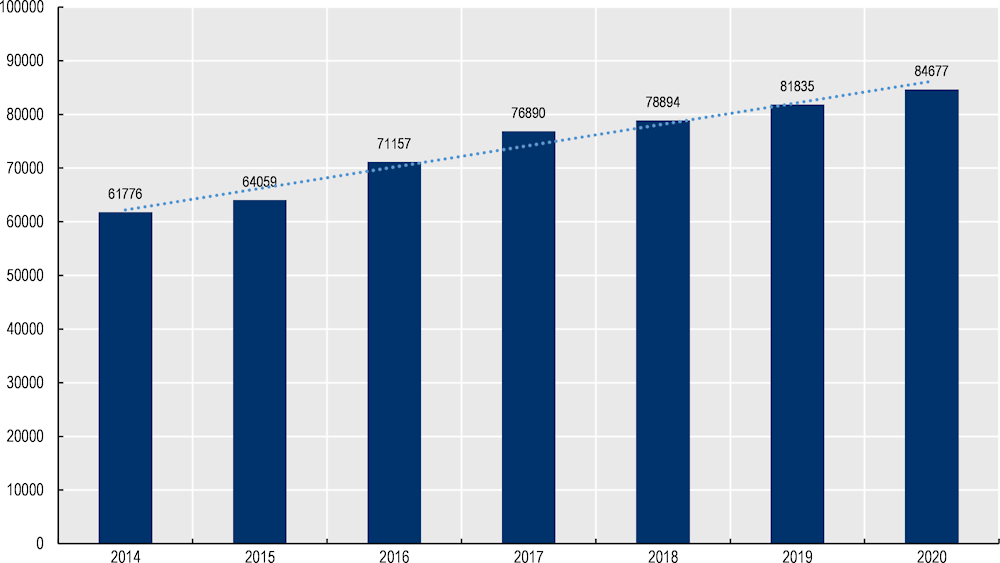

Between 2014 and 2020, the number of MDC patients grew by 37% (61 776 to 84 677) |

Enhancement options: to enhance the effectiveness of MDC, policy makers should continue efforts to promote the use of digital tools across the healthcare sector, including primary care. Digital tools such as electronic health records (EHRs) play an important role in providing co‑ordinated care, which is one of MDC’s key objectives. Sophisticated digital methods to collect patient data can subsequently be used to stratify patients into risk groups, as seen in countries such as Canada and Spain. To enhance the evidence‑base, more robust evaluation methods are necessary, for example, by including data for a control group as well as controlling for confounding factors.

Transferability: new models of primary care, such as MDC, operate in 17 OECD countries, including EU Member States such as Austria, Greece, Ireland, Italy, the Slovak Republic and Slovenia. This indicates MDC, and the type of care it provides, is highly transferable.

Conclusion: MDC provides patients with patient-centred care delivered by a multidisciplinary care team. This model of care is considered “best practice” and is therefore increasingly popular amongst OECD countries. At present, the real impact of MDC on patient health outcomes and utilisation is unknown given data availability constraints. However, a study looking at similar primary care models in Poland concluded patients reported better experiences and outcomes. To enhance the impact of MDC, policy makers should continue policy options outlined in this case study.

Intervention description

The number of people living with one or multiple chronic conditions has been rising. Primary care, as the first point of contact with the healthcare system, plays an important role in preventing, managing and controlling the progression of chronic diseases. Despite widespread acceptance that a high functioning primary care system is essential for improving health outcomes and containing costs, international research shows people with chronic diseases frequently do not receive necessary preventative care, further, the care they do receive is not co‑ordinated (OECD, 2020[]).

Relative to other OECD and EU Member States, Poland has a weak primary care system. A strong primary care system can reduce or eliminate hospitalisations for diseases such as diabetes and congestive heart failure (CHF). Therefore, hospitalisations for these diseases measure the strength of a country’s primary care system. Poland, in 2016, recorded 511 discharges for CHF per 100 000 people, which was the second highest of any EU Member State (OECD, 2019[]).

In response to these challenges, Poland implemented a Primary Healthcare (PHC) Plus programme covering over 40 primary care facilities, each of which offers integrated, patient-centred care. One of these primary care facilities is the Medical and Diagnostic Centre (MDC), established in 2015 in the region of Siedlce. An overview of the MDC model of care is outlined below:

Preliminary visit and diagnostic tests: the patient has an initial visit to the doctor who prescribes a list of tests relevant for the patient. The patient has these tests performed outside the preliminary test.

Main complex visit: once the tests results are available, the patient attends a follow-up appointment with the same doctor and receives a comprehensive assessment. The assessment includes a physical examination by a nurse (e.g. measurement of BMI and blood pressure) followed by a discussion with the doctor who goes over results from the diagnostic tests. Based on test results, the physical examination, medical history, and patient needs, the doctor classifies the patient into one of five risk groups (see Box 8.1) and develops an “Individual Medical Care Plan” (IMCP). The IMCP outlines treatment plans and recommended follow-up appointments. The IMCP is available to the patient’s therapeutic team, which includes a GP, psychiatrist, psychologist, dietitian, occupational therapist and physical therapist. The therapeutic team also have access to patient data via the integrated electronic health record (EHR).

Box 8.1. Patient stratification groups

During the main complex visit, patients are allocated into one of five risk groups:

Group 1: no chronic disease diagnosis

Group 2: patient with a chronic disease who is stable

Group 3: patient with a chronic disease who is stable but requires periodical check-ups

Group 4: patient with a chronic disease who is unstable and requires increased care and frequent follow-up visits

Group 5: patient with a chronic disease who is cared for at home or in a long-term or nursing care facility.

Before taking the main complex visit, all patients are allocated into Group 0 (i.e. the patient has not been allocated to a risk group).

Risk stratification is important for understanding the health and risk profiles of patients, thus allowing health professionals to proactively manage patient needs.

Meeting with the care co‑ordinator: immediately following the main complex visit, the patient visits their care co‑ordinator who is responsible for co‑ordinating treatment and, in agreement with the patient, sets up the necessary appointments, including an educational session. The main complex visit and the meeting with the care co‑ordinator takes approximately 90 minutes.

Education sessions: MDC developed disease‑specific education programs to help patients self-manage, which are run by nurses, nutritionists and dieticians.

Follow-up visits: the IMCP indicates the number of follow-up visits the patient requires, which is based on their risk group. For example, a patient in risk Group 3 (stable but requires periodic check-ups) is assigned two follow-up visits a year compared to Group 4 (unstable patient) who requires 3‑4 follow-up visits (see Box 8.1).

OECD Best Practices Framework assessment

This section analyses MDC against the five criteria within OECD’s Best Practice Identification Framework – Effectiveness, Efficiency, Equity, Evidence‑base and Extent of coverage (see Box 8.2 for a high-level assessment of MDC). Further details on the OECD Framework are Annex A.

Box 8.2. Assessment of MDC

The best practice assessment includes results for MDC as well as the Primary Healthcare (PHC Plus) pilot, which included 41 primary care facilities (including MDC). Findings from the evaluation are included given all pilot sites are based off a similar model of care.

Effectiveness

The number of GP and specialist appointments has remained largely stable (or decreased) despite an increase in the average age of MDC patients. Given, older patients require greater levels of care, these initial results indicate, but do not confirm, MDC has reduced demand for healthcare

An evaluation of PHC Plus found patients had a better care experience and reported lower disease severity. PHC Plus did not reduce utilisation of healthcare services.

Efficiency

Studies evaluating the efficiency of MDC are not available. Evidence from the literature show strong primary care systems reduce unnecessary procedures and utilisation of costly hospital and specialist services

Equity

Over half of all MDC patients are located outside densely populated areas, of which 62% are located in thinly populated areas. These results indicate MDC successfully reaches geographically excluded groups

MDC improves access to care for all population groups by actively reaching out to patients in rural areas as well as participating in local activities that improve preventative care

Evidence‑base

Utilisation of MDC services was collected from patients over a six‑year period (2014‑20). Each year the analysis covered between 60‑85 000 patients. Given the analysis did not include a control group nor control for confounding factors, the change in utilisation cannot be directly attributed to MDC.

Extent of coverage

Between 2014 and 2020, the number of MDC patients grew by 37% (61 776 to 84 677)

Effectiveness

Results for effectiveness are provided for MDC and the PHC Plus pilot. The latter includes findings from an evaluation of 41 pilot sites, which includes MDC. The results are considered relevant for this cases study given all pilot sites are based on the same model of care.1

MDC

The objective of MDC is to improve patient experiences, health outcomes, and reduce utilisation of secondary care services and costs. This section presents data measuring the impact of MDC on healthcare utilisation using data over the period 1 April 2014 to 31 December 2020. Results from the analysis provide an indication, but do not confirm, MDC’s impact on utilisation given limitations in the study design (explored further under the “Evidence‑base” criterion).

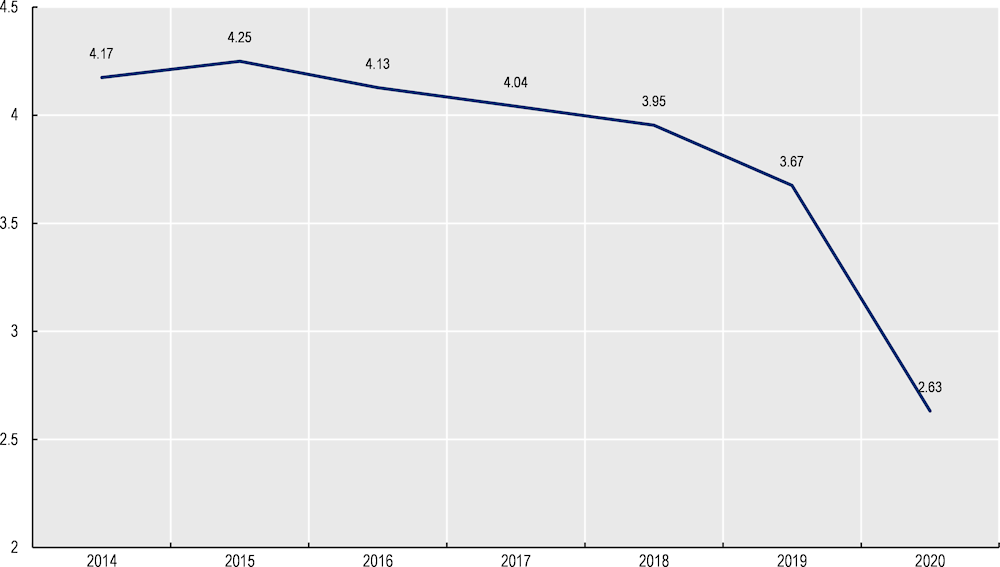

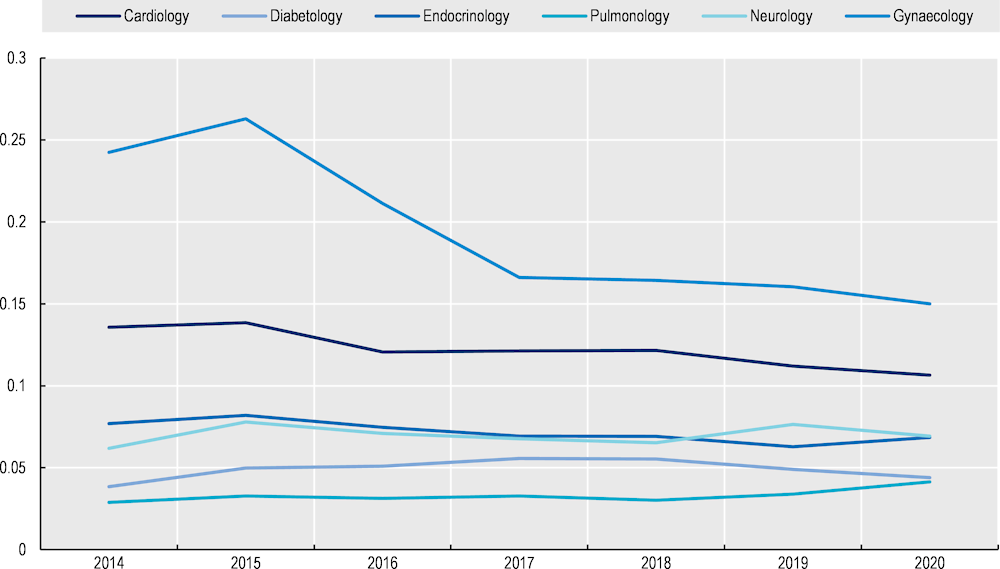

The average number of patient visits did not change markedly despite an increase in the average patient age. Between 2014‑20, the average age of patients enrolled in MDC increased from 48.25 to 51.97. Over the same period, the average number of GP (Figure 8.1) and specialists visits fell, in particular for gynaecological appointments2 (Figure 8.2). Given morbidity and thus healthcare utilisation increase with age, the results indicate, but do not conclude, MDC improved patient outcomes.

Figure 8.1. Change in the average number of GP visits, 2014‑20

Note: The marked downward trend in 2020 likely reflects the impact of the COVID‑19 pandemic.

Source: Data provided by MDC administrators.

Figure 8.2. Change in the average number of specialist visit, 2014‑19

Source: Data provided by MDC administrators.

Primary Healthcare PLUS

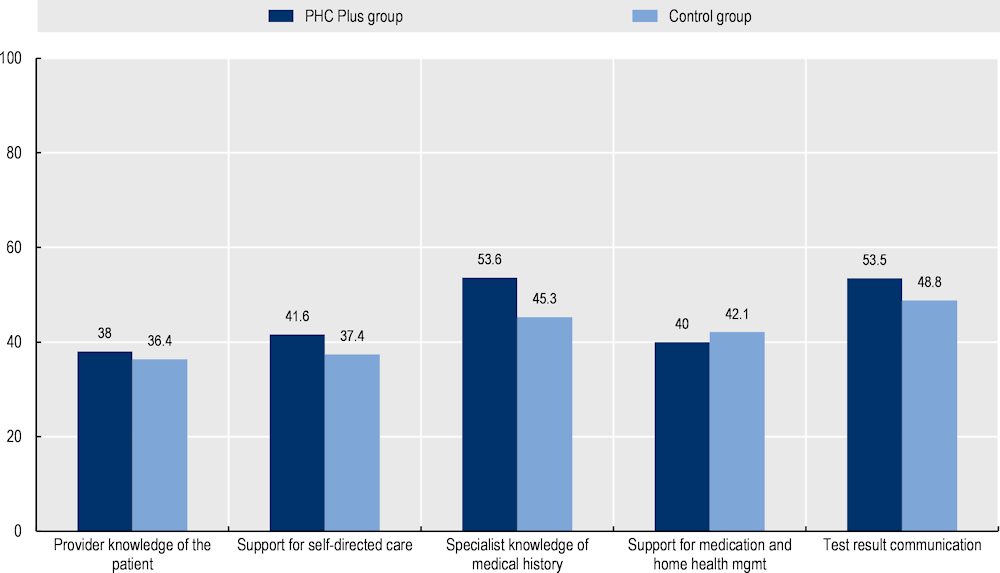

In 2020, the World Bank released findings from its evaluation of PHC Plus two years after the implementation of the pilot programme. The evaluation found an improvement in patient reported experiences and outcomes, and health literacy, but no decrease in the utilisation of hospital services.

Patients recorded a better care experience. Patients enrolled in PHC Plus recorded higher levels of patient reported experience measures (PREMs) compared to patients who receive care in a GP single practice (control group). For example, the PREM score reflecting whether the patient felt the specialist had knowledge of their medical history is over eight points higher for those enrolled in PHC Plus (53.6 versus 45.3 out of a possible 100 points) (Figure 8.3). Patients enrolled in PHC Plus also reported better integration of healthcare, albeit marginally (World Bank, 2020[]).

Figure 8.3. Impact of PHC Plus on selected PREM indicators

Note: Differences between the PHC Plus group and the control group are statistically significant. A higher score indicates a better experience.

Source: World Bank (2020[]), “POZ Plus po 2 latach wdrożenia- wstępne wnioski”.

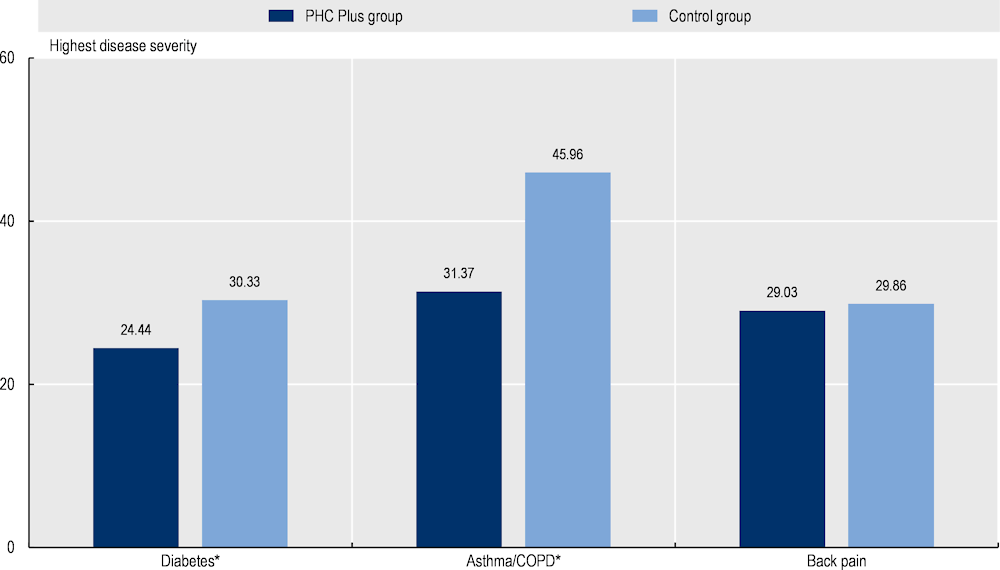

Patients reported better outcome measures. PHC Plus patients with diabetes and asthma/COPD reported lower disease severity. Conversely, disease severity for patients with back pain was similar between the two groups (Figure 8.4).

Figure 8.4. Impact of PHC Plus on selected PROMs (patient-reported outcome measures)

Note: *Indicates differences between the two groups are statistically significant. A high score indicates higher disease severity.

Source: World Bank (2020[]), “POZ Plus po 2 latach wdrożenia- wstępne wnioski”.

The number of hospitalisations increased despite faster access to care. The average monthly number of one‑day hospital stays increased by 8.86 days while longer hospital stays (i.e. +1 day) increased by 12.59 days after the introduction of PHC Plus. These results may reflect an ongoing disconnect between primary and secondary care in Poland. The same study showed initial results indicating “potentially faster” access to tests and healthcare. For example, on average, a patient with diabetes who is enrolled in PHC Plus receives a comprehensive assessment within 68.52 days, which is markedly lower than the 78 days the same patient would wait to see an outpatient centre specialising in diabetology (World Bank, 2020[]).

Patients report being more health literate and less reliant on others for assistance. PHC Plus patients recorded a health literacy score of 79.19 points (out of 100) compared to 76.35 for the control group. Fourteen percent of PHC Plus patients reported involving their family compared to 28% in the control group (World Bank, 2020[]).

Efficiency

Efficiency data from MDC or the PHC Plus intervention are not available. Instead, this section summarises findings from key sources of literature, which conclude that high performing primary healthcare systems help contain spending – see Box 8.3 (OECD, 2020[]).

Box 8.3. The role of primary care systems in containing health spending

As outlined in OECD’s 2020 primary care report, there is sufficient evidence supporting the role of primary care in reducing unnecessary procedures and utilisation of costly hospital and specialist services (WHO, 2018[]). Given the unit cost of treating the same condition in primary care is markedly lower than in hospitals, primary care plays a key role in containing health spending.

Studies from the literature highlighting the impact of primary care on utilisation of secondary services are summarised below:

A systematic review by Wolters et al. (2017[]) concluded that diabetic patients with regular access to primary were less likely to be hospitalised

An international survey of 34 countries (including EU27, except France) by Van den Berg et al. (2015[]) found a significant, negative relationship between better access to primary care and emergency department visits

A systematic review covering studies in the United States found better access to primary was associated with a reduction in unscheduled secondary visits (Huntley et al., 2014[]).

Note: This box highlights only a small number of studies supporting the role of primary care in containing costs. For further examples, see OECD (2020[]).

Equity

More than half of all MDC patients are located outside urban areas. Equity of access has been analysed, at a high-level, using patient data across Degurba (degree of urbanisation) classifications (1 = densely population, 2 = intermediate levels of population, and 3 = thinly populated). Results from the data show more than half of all MDC patients are located outside densely populated areas (61% of all patients or 79 136 patients in total) (see Figure 8.5). These results indicate MDC successfully reaches geographically disadvantaged patients.

Figure 8.5. Number of medical centres and patients by location (total between 2008‑20)

Note: Degurba = degree of urbanisation. LHS = left hand side axis and RHS = right hand side axis.

Source: Data provided by MDC administrators.

MDC actively reaches out to patients living in rural areas. People living outside major urban areas have lower access to healthcare services. As part of the MDC intervention, specialist physicians must travel to small health centres located in rural areas on specific days, as a way to address geographic inequalities.

MDC participates in complementary activities designed to reduce social health disparities. In addition to its core services (see “Intervention description”), MDC supports programs that actively reach out to the community, including disadvantaged groups. For example:

“Healthy Community” contest: the Polish Union of Oncology runs a campaign promoting screening tests, which are performed by the MDC. The contest contributed to an increase in the number of people screened, however, due to data constraints, it is unclear if these people are from priority population groups who would otherwise not have been screened.

Patient transport services: in addition to its core services, MDC runs a preventative care campaign, which offers patients screening and diagnostic tests at their local MDC (usually every Saturday). Free transportation is available for people who may have difficulty accessing their local MDC.

Evidence‑base

This section analyses the quality of evidence to evaluate the effectiveness of MDC and PHC Plus (Table 8.1). In summary:

The impact of MDC on healthcare utilisation was evaluated using data from all patients (n = 61 776 to 84 677 depending on the year) over a period of six years (2014‑20). Data from patients showed that despite an increase in the average patient age, utilisation of GP and specialists services per person stayed the same or declined (see “Effectiveness”). These results only provide an indication that MDC reduces healthcare utilisation given the study design. For example, the results do not include data for a control group, which is necessary to ascertain if trends in utilisation are a result of MDC, further, the analysis does not control for potential confounders (e.g. socio-economic status). Nevertheless, data from MDC patients was collected using routine utilisation data, which is both valid and reliable.

The World Bank evaluated PHC Plus using cross-sectional survey data (2019‑20) from an intervention and control group. In total, patients from 38 PHC Plus sites were included in the intervention group and 63 primary care facilities in the control group. Differences between the intervention and control group prior to the analyses were not reported, however, the methodology controlled for key confounders including age, gender, facility size, education and self-perceived financial status. Data to measures patient reported experiences and outcomes were collected using valid and reliable tools.

Table 8.1. Evidence‑based assessment – MDC

|

Assessment category |

Question |

Score – MDC |

Score – PHC Plus |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Selection bias |

Are the individuals selected to participate in the study likely to be representative of the target population? |

Very likely |

Can’t tell |

|

What percentage of selected individuals agreed to participate? |

100% |

Can’t tell |

|

|

Selection bias score: |

Strong |

Weak |

|

|

Study design |

Indicate the study design |

Cohort (one group pre + post) |

Other – cross sectional study with control and intervention group |

|

Was the study described as randomised? |

No |

Can’t tell |

|

|

Was the method of randomisation described? |

N/A |

N/A |

|

|

Was the method of randomisation appropriate? |

N/A |

N/A |

|

|

Study design bias score: |

Moderate |

Weak |

|

|

Confounders |

Were there important differences between groups prior to the intervention? |

Can’t tell |

Can’t tell |

|

What percentage of potential confounders were controlled for? |

N/A |

80‑100% |

|

|

Confounders score: |

Weak |

Unknown* |

|

|

Blinding |

Was the outcome assessor aware of the intervention or exposure status of participants? |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Were the study participants aware of the research question? |

Yes |

Yes |

|

|

Blinding score: |

Weak |

Weak |

|

|

Data collection methods |

Were data collection tools shown to be valid? |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Were data collection tools shown to be reliable? |

Yes |

Yes |

|

|

Data collection methods score: |

Strong |

Strong |

|

|

Withdrawals and dropouts |

Were withdrawals and dropouts reported in terms of numbers and/or reasons per group? |

Can’t tell |

Can’t tell |

|

Indicate the percentage of participants who completed the study? |

Can’t tell |

Can’t tell |

|

|

Withdrawals and dropouts score: |

Weak |

Weak |

Note: *The quality of evidence score is not available when data between differences in the control and intervention group are not provided, yet it is evident that the analysis controlled for confounders. Hence, the “confounders score” has been marked as “unknown”.

Source: Effective Public Health Practice Project (1998[]), “Quality assessment tool for quantitative studies”, https://www.nccmt.ca/knowledge-repositories/search/14.

Extent of coverage

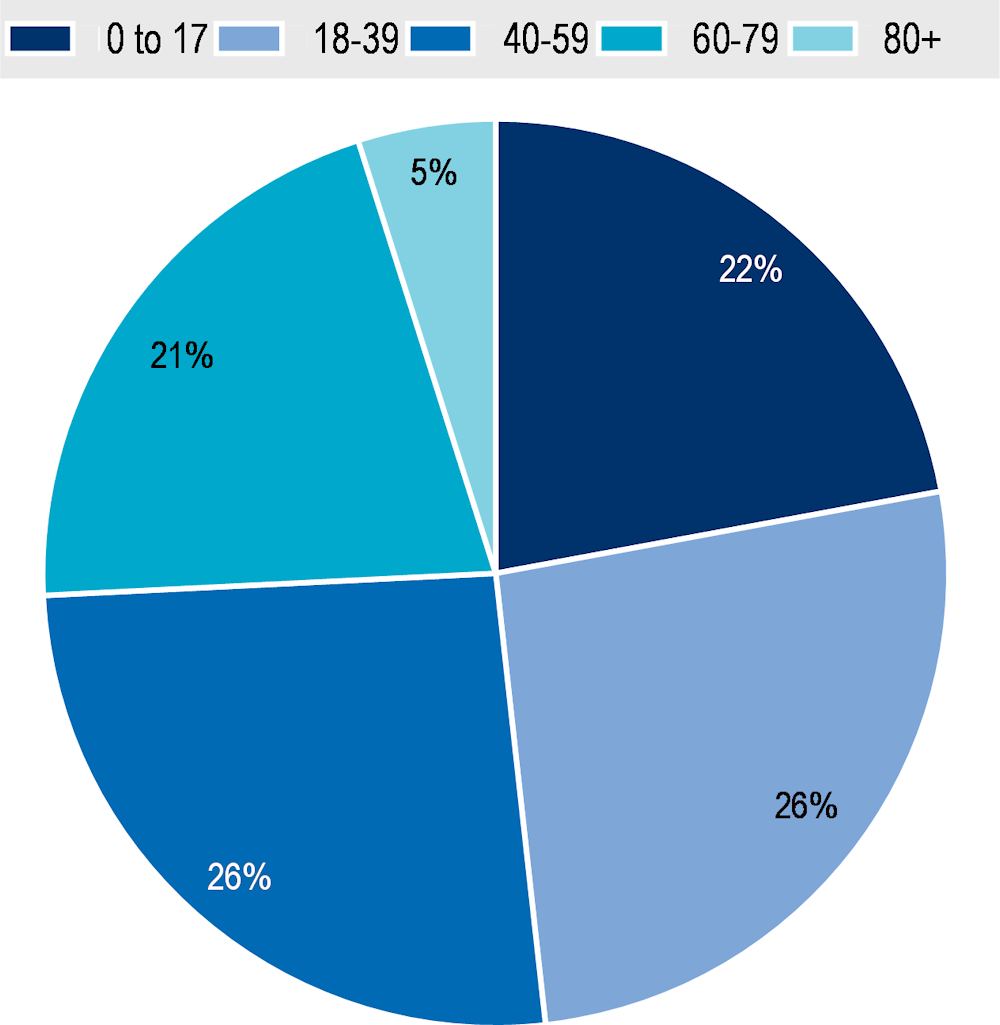

Between 2014 and 2020 the number of MDC patients grew by 37% – i.e. from 61 776 to 84 677 (Figure 8.6). As of 2020, 22% of patients were aged 0‑17, 52% between ages 18 to 59 while the remaining 26% are at least 60 years of age (Figure 8.7).

Figure 8.6. Number of MDC patients, 2014‑20

Source: Data provided by MDC administrators.

Figure 8.7. Breakdown of MDC patients by age group

Source: Data provided by MDC administrators.

Policy options to enhance performance

Policy options to enhance the overall performance of MDC are summarised below. Many of the options target higher-level policy makers (e.g. at the national level as opposed to MDC administrators), given they involve significant structural change.

Enhancing effectiveness

Continue effort to promote the use of electronic health records (EHRs) in primary care. In 2011, Poland introduced the Act on Information System in Healthcare requiring all patient information to be uploaded electronically by 2014, which was subsequently delayed to 2017 (Czerw et al., 2016[]). As of July 2021, it is compulsory to record medical events using EHRs (specifically to the P1 Platform). Given the importance of EHRs in supporting integrated, patient-centred care, policy makers should continue to promote efforts to safely and securely share patient information electronically.

Improve communication between primary care professionals and patients by continuing to improve Poland’s health portal. High-quality primary care models encourage patients to play an active role in improving their health (e.g. shared-decision making, support for self-management). Digital tools, such as health portals (often referred to as patient-provider portals), play a key role in this context. In 2018, Poland introduced the Patient’s Internet Account (IKP). Through the IKP patients can obtain information on their e‑prescriptions, e‑referrals, as well as for their children, sick leave, and a history of visits and medication together with dosage amounts. Patients can also schedule a COVID‑19 vaccination appointment as well as download an electronic Digital COVID‑19 Certificate (EU DCC) confirming that the vaccination has been administered. Policy makers should continue efforts to expand the services and capabilities of the IKP.

Build towards using data-driven means to stratify patients into risk groups. As part of the MDC intervention, doctors allocate patients into risk groups (see Box 8.1) based on information collected during the main complex visit (e.g. a physical examination, diagnostic tests). Risk stratification is commonly employed amongst OECD countries, however, increasingly countries rely on big data to stratify patients. For example, the Catalan Open Innovation Healthcare Hub have developed an adjusted morbidity grouper (GMA) algorithm, which uses data from EHRs3 to stratify patients into risk groups. Sophisticated digital methods improve the accuracy and efficiency of population risk stratification.

Enhancing efficiency

No specific policy options to enhance the efficiency of MDC are proposed. Rather, it is recognised that the government has signalled its intention to offer GPs financial incentives for providing co‑ordinated care, a move that aims to enhance the efficiency of primary care models such as MDC (Sowada, Sagan and Kowalska-Bobko, 2019[]).

Enhancing equity

MDC performs well against the equity best practice criterion given its ability to reach patients living outside urban areas. In order to improve equity, information on access to and impact of MDC on different priority population groups is needed (as explored under “Enhancing the evidence base”).

Enhancing the evidence‑base

More robust evaluations are necessary to understand the real impact of MDC. Data to evaluate the impact of MDC relied on cross-sectional utilisation data for MDC patients only. Therefore, results from the analysis only provide an indication of MDC’s impact (see “Effectiveness”). Future evaluation study designs should consider:

Collecting data for a control group, for example using patient data from another region in Poland

Controlling for potential confounding variables, that is, variables that impact the outcome of interest (e.g. patients with a lower socio-economic status typically experience worse health outcomes)

Assessing the impact using data on avoidable hospital admissions – e.g. for diabetes, congestive heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease – given it is common indicator for assessing primary care quality.

Stratify patient data to measure the impact of MDC on priority population groups. When studying the impact of healthcare interventions, it is important to look at their effect on inequalities. As a first step, it is necessary to identify potential inequalities, which can be captured during the data collection process (e.g. collect patient data on race, socio-economic groups if allowed and feasible). This information allows researchers to analyse whether the intervention increases or decreases inequalities. If the latter, follow-up research, for example, through patient interviews, will help MDC administrators adapt and improve the intervention to suit the needs of priority populations.

Enhancing extent of coverage

Given limited information on the extent of coverage for MDC, specific polices to boost uptake have not been included. However, in general, efforts to boost health literacy (HL) likely increase patient motivation to take control of their health and thus participate in programs such as MDC (see Box 8.4 for example policies to boost HL).

Box 8.4. Policies to boost health literacy

To address low rates of adult health literacy, OECD have outlined a four‑pronged policy approach (OECD, 2018[]):

Strengthen the health system role: establish national strategies and framework designed to address HL

Acknowledge the importance of HL through research: measure and monitor the progress of HL interventions to better understand what policies work

Improve data infrastructure: improve international comparisons of HL as well as monitoring HL levels over time

Strengthen international collaboration: share best practice interventions to boost HL across countries.

Transferability

This section explores the transferability of MDC and is broken into three components: 1) an examination of previous transfers; 2) a transferability assessment using publicly available data; and 3) additional considerations for policy makers interested in transferring MDC.

Previous transfers

New models of primary care have been transferred across many OECD countries and EU Member States. The MDC model reflects best practice principles in the area of primary care, specifically by delivering patient centred care through a co‑ordinated team of health professionals. These “new models of [primary] care” exist in several OECD/EU countries with Australia (Primary Health Networks), Canada (My Health Team) and the United States (Comprehensive Primary Care Plus) leading the way (OECD, 2020[]).

Transferability assessment

The following section outlines the methodological framework to assess transferability and results from the assessment.

Methodological framework

Details on the methodological framework to assess transferability can be found in Annex A.

Several indicators to assess the transferability of MDC were identified (Table 8.2). Indicators were drawn from international databases and surveys to maximise coverage across OECD and non-OECD European countries. Please note, the assessment is intentionally high level given the availability of public data covering OECD and non-OECD European countries.

Table 8.2. Indicators to assess transferability – MDC

|

Indicator |

Reasoning |

Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

|

Population context |

||

|

% of people who visited a GP in the last 12 months at least once |

MDC will have a greater extent of coverage in countries where more people access their GP frequently |

🡹 = more transferable |

|

Sector context (primary care) |

||

|

Proportion of GPs who work in single‑handed practices |

MDC is more transferable in countries where GPs feel comfortable working with other health professionals. This indicator is a proxy to measure the willingness of GPs to work in co‑ordinated teams. |

Low = more transferable High = less transferable |

|

Proportion of physicians in primary care facilities using electronic health records |

EHRs improve the ability of health professionals to provide integrated patient-centred care. Therefore, MDC is more transferable in countries that utilise EHRs in primary care facilities. |

🡹 = more transferable |

|

The extent of task shifting between physicians and nurses in primary care |

MDC promotes integrated care provided by multidisciplinary teams. Therefore, MDC is more transferable in countries where physicians feel comfortable shifting tasks to nurses. |

The more “extensive” the more transferable |

|

The use of financial incentives to promote co‑ordination in primary care |

MDC is more transferable to countries with financial incentives that promote co‑ordination of care across health professionals. |

Bundled payments or co‑ordinated payment = more transferable |

|

Economic context |

||

|

Primary healthcare expenditure as a percentage of current health expenditure |

MDC is a primary care intervention, therefore, it is likely to be more successful in countries that allocate a higher proportion of health spending to primary care |

🡹 = “more transferable” |

Source: WHO (2018[]), “Primary Health Care (PHC) Expenditure as percentage Current Health Expenditure (CHE)”, https://apps.who.int/nha/database; Oderkirk (2017[]), “Readiness of electronic health record systems to contribute to national health information and research”, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9e296bf3-en; Schäfer et al. (2019[]), “Are people’s healthcare needs better met when primary care is strong? A synthesis of the results of the QUALICOPC study in 34 countries”, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1463423619000434; Maier and Aiken (2016[]), “Task shifting from physicians to nurses in primary care in 39 countries: a cross-country comparative study”, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckw098; OECD (2020[]), Realising the Potential of Primary Health Care, https://doi.org/10.1787/a92adee4-en; OECD (2016[]), “Health Systems Characteristics Survey”, https://qdd.oecd.org/subject.aspx?Subject=hsc; European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (2021[]), “The Health Systems and Policy Monitor”, https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int/countries/overview.

Results

The transferability of MDC was assessed using six indicators covering three contextual factors – the population context, the sector context (primary care) and the economic context (Table 8.3). Results from the assessment indicate primary care systems in target countries would be supportive of MDC – for example, in countries with available data, 79% of primary care physicians utilise EHRs, a key tool to support co‑ordinated care, compared to just 30% in Poland. Further, most countries have the same or a lower proportion of GPs working in single practices, which is a proxy measure of GP willingness to work in a team. MDC’s extent of coverage is expected to be high given people living in other OECD/non-OECD European countries are more likely to access primary care (i.e. GP) (79% of people of in OECD/non-OECD European countries visited a GP in the last year compared to 64% in Poland). Nevertheless, results from the assessment indicate many countries may face barriers to implement co‑ordinated care given only 22% report extensive task shifting between primary care physicians and nurses. An indicator to measure political support is not included in the assessment. However, the recent (2018) agreement on the Declaration of Astana clearly shows countries support efforts to improve primary care.

It is important to note that 17 OECD countries have implemented new models of primary care similar to MDC (OECD, 2020[]). For these countries, results from the transferability assessment can instead be used to identify areas to enhance the impact of the new care model. For example, despite establishing Primary Care Units, a high proportion of GPs in Austria continue to work in single practices.

Table 8.3. Transferability assessment by country (OECD and non-OECD European countries) – MDC

A darker shade indicates MDC is more suitable for transferral in that particular country

|

Country |

% visited GP in last 12 months |

% GPs in single practices |

% PC* using EHRs |

Task shifting in PC |

Financial incentives |

Primary expenditure percentage CHE** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Poland |

64 |

Medium |

30 |

None |

None |

47 |

|

Australia † |

n/a |

Low |

96 |

Extensive |

Bundled |

37 |

|

Austria † |

84 |

High |

80 |

None |

Co‑ordinated payment |

37 |

|

Belgium |

87 |

High |

n/a |

Limited |

Bundled |

40 |

|

Bulgaria |

48 |

High |

n/a |

None |

Bundled |

47 |

|

Canada † |

n/a |

Low |

77 |

Extensive |

Bundled |

48 |

|

Chile |

n/a |

n/a |

65 |

n/a |

None |

n/a |

|

Colombia |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

None |

n/a |

|

Costa Rica |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

None |

33 |

|

Croatia |

68 |

n/a |

3 |

Limited |

None |

38 |

|

Cyprus |

68 |

Low |

n/a |

Limited |

None |

41 |

|

Czech Republic |

86 |

High |

n/a |

None |

None |

33 |

|

Denmark |

86 |

Medium |

100 |

Limited |

Co‑ordinated payment |

38 |

|

Estonia † |

73 |

High |

99 |

Limited |

None |

44 |

|

Finland |

68 |

Medium |

100 |

Extensive |

None |

46 |

|

France † |

85 |

n/a |

80 |

None |

Bundled |

43 |

|

Germany |

89 |

High |

n/a |

None |

Co‑ordinated payment |

48 |

|

Greece † |

40 |

High |

100 |

None |

None |

45 |

|

Hungary |

71 |

High |

n/a |

Limited |

None |

40 |

|

Iceland |

n/a |

Low |

100 |

Limited |

Co‑ordinated payment |

35 |

|

Ireland † |

76 |

Low |

95 |

Extensive |

None |

47 |

|

Israel |

n/a |

n/a |

100 |

n/a |

Co‑ordinated payment |

n/a |

|

Italy † |

71 |

Medium |

n/a |

Limited |

Bundled |

n/a |

|

Japan |

n/a |

n/a |

36 |

n/a |

None |

52 |

|

Korea |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

None |

57 |

|

Latvia |

80 |

High |

70 |

Limited |

Bundled |

39 |

|

Lithuania |

76 |

Medium |

n/a |

Limited |

None |

48 |

|

Luxembourg |

89 |

Medium |

n/a |

None |

None |

38 |

|

Malta |

83 |

Medium |

n/a |

Limited |

None |

62 |

|

Mexico † |

n/a |

n/a |

30 |

n/a |

Co‑ordinated payment |

44 |

|

Netherlands |

71 |

Medium |

n/a |

Extensive |

Bundled |

32 |

|

New Zealand |

n/a |

Low |

95 |

Extensive |

None |

n/a |

|

Norway † |

79 |

Low |

100 |

None |

None |

39 |

|

Portugal |

81 |

Low |

n/a |

Limited |

None |

58 |

|

Romania |

57 |

Medium |

n/a |

None |

None |

35 |

|

Slovak Republic † |

82 |

High |

89 |

None |

None |

n/a |

|

Slovenia † |

76 |

High |

n/a |

Limited |

None |

43 |

|

Spain |

80 |

Low |

99 |

Limited |

None |

39 |

|

Sweden † |

62 |

Low |

100 |

Limited |

Co‑ordinated payment |

n/a |

|

Switzerland |

n/a |

Medium |

40 |

None |

None |

40 |

|

Türkiye † |

n/a |

Low |

n/a |

None |

None |

n/a |

|

United Kingdom |

74 |

Low |

99 |

Extensive |

None |

53 |

|

United States † |

n/a |

n/a |

83 |

Extensive |

None |

n/a |

Note: † = implemented new models of primary care. *PC = primary care. **CHE = current health expenditure. n/a = no data available.

Source: See Table 8.2.

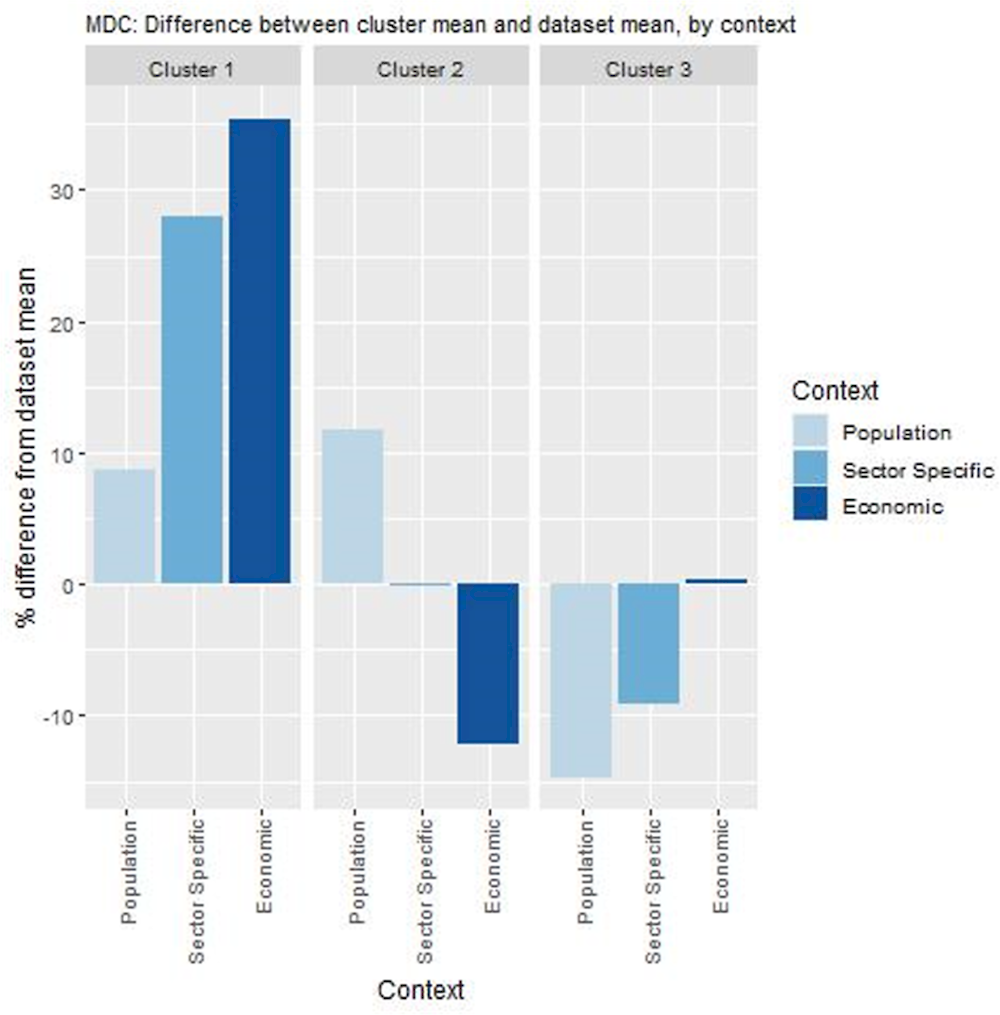

To help consolidate findings from the transferability assessment above, countries have been clustered into one of three groups, based on indicators reported in Table 8.2. Countries in clusters with more positive values have the greatest transfer potential. For further details on the methodological approach used, please refer to Annex A.

Key findings from each of the clusters are below with further details in Figure 8.8 and Table 8.4:

Countries in cluster one have populations who frequently see their GP and a primary care system equipped to implement this model of care. Further, they spend relatively more on primary care. For these reasons, these countries are les likely to experience any implementation barriers should this intervention be transferred.

Countries in cluster two also have populations who frequently attend their GP, however, they spend relatively less on primary care indicating potential long-term affordability issues.

Countries in cluster three have populations who are less likely visit their GP and operate primary care systems that may not encourage integration among different care sectors. It is important to note that Poland falls under this cluster, meaning conditions in which these clusters could improve on, although ideal, are not pre‑requisites. For example, Poland introduced this model of care as it recognised its primary care sector was weak.

Figure 8.8. Transferability assessment using clustering – MDC

Note: Bar charts show percentage difference between cluster mean and dataset mean, for each indicator.

Source: See Table 8.2.

Table 8.4. Countries by cluster – MDC

|

Cluster 1 |

Cluster 2 |

Cluster 3 |

|---|---|---|

|

Australia Canada Ireland New Zealand United Kingdom |

Belgium Croatia Czech Republic Denmark France Iceland Italy Latvia Malta Netherlands Norway Portugal Slovak Republic Spain Sweden |

Austria Bulgaria Cyprus Estonia Finland Germany Greece Hungary Lithuania Luxembourg Mexico Poland Romania Slovenia Switzerland |

Note: Due to high levels of missing data the following countries were omitted from the analysis Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Israel, Japan, Korea, Türkiye, and the United States.

New indicators to assess transferability

Data from publicly available datasets is not ideal to assess the transferability of MDC. For example, there is no international comparable data measuring the level of trust between primary care professionals. Therefore, Box 8.5 outlines several new indicators policy makers could consider before transferring MDC.

Box 8.5. New indicators, or factors, to consider when assessing transferability – MDC

In addition to the indicators within the transferability assessment, policy makers are encouraged to collect information for the following indicators:

Population context

What is the population’s attitude towards receiving care from health professionals who are not doctors?

What is the level of health literacy amongst patients? (i.e. are patients likely to engage in shared decision-making?)

Sector specific context (primary care)

To what extent do health professionals already work as a co‑ordinated team?*

What is the level of acceptability (trust) amongst health professionals to work together as a co‑ordinated team?

Does the clinical information system support: a) sharing of patient data across health professionals? b) Sharing of patient data across healthcare facilities?

Do health provider reimbursement schemes support co‑ordinated care? (e.g. bundled payments, add-on payments that incentivise co‑ordinated care)

Political context

Has the intervention received political support from key decision-makers?

Has the intervention received commitment from key decision-makers?

Economic context

What is the cost of implementing and operating the intervention in the target setting and to whom?

*17 OECD countries have implemented new models of primary care (see Table 3.2 in OECD (2020[])).

Conclusion and next steps

MDC offers patient-centred, co‑ordinated care. MDC stratifies patients into risk groups based on information collected from their main complex visit. Data from the main complex visit is subsequently uploaded into an Individual Medical Care Plan, which is available to the patient’s therapeutic care team. In addition, each patient is assigned a care co‑ordinator who sets up necessary appointments and educational sessions to enhance self-management. According to the definition in OECD’s recent primary care report, MDC is a “new model of care”” as it delivers care through a multidisciplinary team and promotes shared-decision making (OECD, 2020[]).

New models of primary care, such as MDC, reduce healthcare use and improve patient reported experience and outcomes. Healthcare utilisation data over the period 2014‑20 show that despite an increase in the average age of MDC patients, the number of GP and specialists visits per person did not change markedly (and in some cases declined). Given the data do not control for confounding factors nor include a control group, results from this analysis only provide an indication of MDC’s impact on utilisation. An evaluation of the PHC Plus pilot (which covered 41 primary care facilities, including MDC) found patients enrolled in the programme reported better experience and outcome measures. Results regarding utilisation did not see a reduction in hospital utilisation.

MDC successfully reaches patients living outside urban areas who typically have lower levels of access to care. More than half (61%) of all MDC patients are located outside densely populated areas, most of whom live in thinly populated areas. Further, MDC requires specialist physicians to visit small rural health centres as a way to address geographic health inequalities. For these reasons, MDC performs particularly well against the equity best practice criterion.

Better use of digital tools such as EHRs and health portals will enhance the performance of MDC. MDC aims to provide patients with co‑ordinated patient-centred care. Digital tools such as EHRs and health portals play a key role in this context, and as such have been continually promoted in Poland in recent years. Policy makers should therefore continue their efforts to build the country’s digital health system.

Primary care models similar to MDC exist in many OECD countries, with this number likely to grow. MDC represents a new model of primary care that promotes patient-centred, co‑ordinated, multidisciplinary care. OECD’s recent primary care report found 17 OECD countries employ this type of model indicating it is highly transferable.

Next steps for policy makers and funding agencies regarding the MDC model are in Box 8.6.

Box 8.6. Next steps for policy makers and funding agencies – MDC

Next steps for policy makers and funding agencies to enhance MDC are listed below:

Continue efforts to enhance the use of digital tools, such as EHRs, in a primary care setting

Support robust evaluations of MDC to better understand the intervention’s impact on patient experiences, outcomes and utilisation of healthcare services

Support policy efforts to boost population health literacy as a way to encourage people to take a more active role in their care

Promote findings from the MDC case study to better understand what countries/regions are interested in transferring the intervention.

References

[9] Czerw, A. et al. (2016), “Implementation of electronic health records in Polish outpatient health care clinics – starting point, progress, problems, and forecasts”, Annals of Agricultural and Environmental Medicine, Vol. 23/2, pp. 329-334, https://doi.org/10.5604/12321966.1203900.

[8] Effective Public Health Pratice Project (1998), Quality assessment tool for quantitative studies, https://www.nccmt.ca/knowledge-repositories/search/14.

[18] European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (2021), The Health Systems and Policy Monitor, https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int/countries/overview (accessed on 9 June 2021).

[7] Huntley, A. et al. (2014), “Which features of primary care affect unscheduled secondary care use? A systematic review”, BMJ Open, Vol. 4/5, p. e004746, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004746.

[15] Maier, C. and L. Aiken (2016), “Task shifting from physicians to nurses in primary care in 39 countries: a cross-country comparative study”, The European Journal of Public Health, Vol. 26/6, pp. 927-934, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckw098.

[13] Oderkirk, J. (2017), “Readiness of electronic health record systems to contribute to national health information and research”, OECD Health Working Papers, No. 99, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9e296bf3-en.

[16] OECD (2020), Realising the Potential of Primary Health Care, OECD Health Policy Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/a92adee4-en.

[1] OECD (2020), Realising the Potential of Primary Health Care, OECD Health Policy Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris,, https://doi.org/10.1787/a92adee4-en.

[2] OECD (2019), Hospital discharges by diagnosis, in-patients, per 100 000 inhabitants - Avoidable hospital admission, Congestive Heart Failure.

[11] OECD (2018), “Health literacy for people-centred care: Where do OECD countries stand?”, OECD Health Working Papers, No. 107, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/d8494d3a-en.

[17] OECD (2016), Health Systems Characteristics Survey 2016, https://qdd.oecd.org/subject.aspx?Subject=hsc.

[14] Schäfer, W. et al. (2019), “Are people’s health care needs better met when primary care is strong? A synthesis of the results of the QUALICOPC study in 34 countries”, Primary Health Care Research & Development, Vol. 20, https://doi.org/10.1017/s1463423619000434.

[10] Sowada, C., A. Sagan and I. Kowalska-Bobko (2019), Poland: Health system review, ublications, WHO Regional Office for Europe.

[6] van den Berg, M., T. van Loenen and G. Westert (2015), “Accessible and continuous primary care may help reduce rates of emergency department use. An international survey in 34 countries”, Family Practice, Vol. 33/1, pp. 42-50, https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmv082.

[4] WHO (2018), Building the economic case for primary health care: a scoping review, WHO, Geneva.

[12] WHO (2018), Primary Health Care (PHC) Expenditure as % Current Health Expenditure (CHE).

[5] Wolters, R., J. Braspenning and M. Wensing (2017), “Impact of primary care on hospital admission rates for diabetes patients: A systematic review”, Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, Vol. 129, pp. 182-196, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2017.05.001.

[3] World Bank (2020), POZ Plus po 2 latach wdrożenia- wstępne wnioski.

Notes

← 1. MDC differs from other pilot sites in two key aspects: MDC offers care for all patients where as PHC Plus pilots cover patients with one of 11 selected diseases, further, MDC incorporated an oncology prevention element.

← 2. The relatively sharp decline in gynaecological appointments reflects three factors: 1) an increase in prevention activities between years 2011‑15; 2) better co‑ordination and management of gynaecological appointments; and 3) since 2017, midwives in Poland have the right to provide care for pregnant women independently.

← 3. The algorithm uses information such as diagnostic classification, date of diagnosis, age and gender.