This chapter covers Telemonitoring for advanced heart failure in the Czech Republic’s University Hospital of Olomouc. The case study includes an assessment of the Telemonitoring programme against the five best practice criteria, policy options to enhance performance and an assessment of its transferability to other OECD and EU27 countries.

Integrating Care to Prevent and Manage Chronic Diseases

12. Telemonitoring for patients with advanced heart failure, Czech Republic

Abstract

Telemonitoring for patients with advanced heart failure case study overview

Description: in 2013, the University Hospital Olomouc in the Czech Republic implemented a telemonitoring intervention for patients with advanced heart failure (HF). As part of the intervention, a patient’s vital signs are automatically shared daily with health professionals at the hospital including blood pressure, blood saturation, and results from electrocardiograms. Patient data is collected automatically through an implanted defibrillator or pacemaker. In addition, patients manually upload information such as their fluid intake for the day.

Best practice assessment:

OECD best practice assessment of telemonitoring for patients with advanced heart failure

|

Criteria |

Assessment |

|---|---|

|

Effectiveness |

An evaluation of telemonitoring for HF patients in Olomouc is not available. However, findings from the literature show telemonitoring for HF patients reduces all-cause and HF-related mortality. |

|

Efficiency |

Telemonitoring for HF patients has the potential to improve efficiency within the healthcare system. However, the evidence to date is limited and shows mixed results. |

|

Equity |

Based on the broader literature, there is evidence to suggest telemonitoring can both increase as well as decrease existing health inequalities (e.g. digital exclusion while on the other hand increasing access to difficult-to-reach patients). |

|

Evidence‑base |

Evidence supporting the impact of telemonitoring for HF on health outcomes is of high quality as it relies on systematic reviews and meta‑analyses largely covering RCTs studies. The evidence supporting its efficiency however is less developed and very much lacking in regard to equity. |

|

Extent of coverage |

The current pilot operating in the city of Olomouc only reaches a small proportion of patients with HF in the Czech Republic. Therefore, there is significant scope to extend the coverage of this intervention. |

Enhancement options: policy makers should prioritise undertaking a robust evaluation of the pilot intervention in Olomouc to better understand what is working and what requires improvement. Following an evaluation, and if results prove positive, this intervention can be extended to cover a larger number of people thereby decreasing per participant costs. Finally, when scaling-up the intervention, attention should be paid to ensuring eligible patients from disadvantaged populations are prioritised (e.g. those at risk of digital exclusion, such as people living in regional/rural areas).

Transferability: telemonitoring programs for HF patients exist across many OECD and EU countries highlighting its transferability. Administrators of this intervention in Olomouc are supportive of scaling-up the intervention across the Czech Republic and do not foresee any major implementation barriers.

Conclusion: telemonitoring for HF patients in Olomouc, Czech Republic, is a well-designed intervention with the potential to improve patient outcomes and experiences while simultaneously reducing costs. A future evaluation is necessary to determine the true impact of this intervention and is necessary for scaling-up the intervention across the country.

Intervention description

Heart failure (HF), also known as congestive heart failure, is when the heart muscle stops pumping blood the way they should. Consequently, fluid can build up in the lungs leading to shortness of breath. There are several common causes of HF including coronary artery disease (caused by a build-up fatty material in the arteries, also known as plaque), high blood pressure and diabetes. For these reasons, HF is more common among people living with overweight and those aged 65 years and over. It is also more common among men than women (Mayo Clinic, 2022[]).

An ageing population combined with rising rates of overweight (including obesity) have led to an increase in the number of people experiencing HF in OECD and EU countries. For example, between 2000 and 2019, the rate of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) among OECD countries increased by 18%. However, mortality from major types of HF such as cardiac arrests has been falling over the past two decades (e.g. across the OECD, mortality from cardiac arrests and other ischemic heart diseases fell by 46% between 2000 and 2019) (OECD, 2021[]). Trends in HF specific to the Czech Republic are in Box 12.1.

Box 12.1. Heart failure trends in the Czech Republic

A recent analysis of data from the Czech National Registry of Reimbursed Health Services provide insight into HF trends. Key findings from the paper are summarised below (Táborský et al., 2021[]):

The prevalence of HF increased by 61% – i.e. from 1 679 to 2 689 per 100 000 people between 2012 and 2018 (p < 0.001). Better recognition of and treatment for HF over this period likely explains, at least in part, the rise in prevalence.

The prevalence of HF is greater among men than women: 2 778 and 2 602 per 100 000 for men and women, respectively (as of 2018).

The annual mortality rate from HF decreased by around 5 percentage points between 2012 and 2018 – i.e. from 20.55% to 15.89%.

Increased rates of people with HF is not only a health problem, but also an economic one given it is associated with a high number of hospital visits, premature mortality and productivity losses. For example, approximately 2% of a country’s healthcare budget is spent on HF in European and North American countries (Soundarraj et al., 2017[]). In the Czech Republic, this equates to approximately EUR 21.2 million per year (OECD, 2021[]).

In an effort to improve care for patients with HF while simultaneously reducing costs, countries across the OECD are increasingly looking to digital solutions, including telemonitoring. Telemonitoring refers to the use of “mobile devices and platforms to conduct routine medical tests, communicate the results to healthcare workers in real-time, and potentially launch pre‑programmed automated responses” (Oliveira Hashiguchi, 2020[]).

In the Czech Republic, in 2013, the University Hospital Olomouc introduced telemonitoring for patients with advanced HF – specifically, congestive heart failure, structural damage of the myocardium or left chamber dysfunction.1 As part of this intervention, a patient’s vital signs are shared daily with health professionals, using both automatic and manual means (see Box 12.2 for a list of vital signs). Patient information is primarily collected using invasive means – i.e. an implanted defibrillator or pacemaker.

Box 12.2. Types of patient vital signs

This box outlines the types of vital signs collected from patients on a daily basis as of part telemonitoring for HF patients in the Czech Republic:

Blood pressure

Heart rate

Weight

Body fat

Percentage water in body

Blood saturation

Electrocardiogram (EKG)

Medication adherence

Step count

In addition to the data outlined above, patients can manually enter information on their fluid intake, leg swelling as well answer questionnaires (e.g. about quality of life and depression).

Each patient receives the necessary equipment and devices to transmit data, which are property of the hospital to ensure they meet regulatory standards. To participate, patients must also have access to a smart phone or tablet with Android iOS in order to upload the application necessary for transferring data (a smart phone or tablet can be supplied by the patient or provided by the University Hospital Olomouc).

The objectives of this intervention are three‑fold, namely:

Treatment quality: deliver patients high-quality, standardised care in line with national and European medical society standards

Patient outcomes: improve morbidity, mortality and patient quality of life by detecting signs of deterioration at an early stage, thereby allowing patients to receive treatment promptly

Cost savings: reduce hospitalisations, emergency admissions and other healthcare services thereby cutting expenses.

The intervention currently operates out of one hospital in the Czech Republic – the University Hospital of Olomouc – and therefore only covers patients living within this city.

OECD Best Practices Framework assessment

This section analyses telemonitoring for advanced HF patients in the Czech city of Olomouc against five criteria within OECD’s Best Practice Identification Framework – Effectiveness, Efficiency, Equity, Evidence‑base and Extent of coverage (see Box 12.3 for a high-level assessment). Further details on the OECD Framework can be found in Annex A.

Box 12.3. Assessment of telemonitoring for advanced HF patients, city of Olomouc, Czech Republic

Effectiveness

A robust evaluation of telemonitoring for HF patients in the Czech Republic is not available, therefore its effectiveness cannot be verified. However, initial reports indicate the intervention successfully reduced hospitalisations by 40%.

Evidence from similar interventions in other countries indicate that telemonitoring for HF patients is highly effective at reducing all-cause and HF related mortality.

Efficiency

Telemonitoring has the potential to reduce costs by performing routine checks remotely as well as detecting patient deterioration at an early stage, which limits the potential for health problems to escalate.

Economic evaluations are not available for this specific intervention in the Czech Republic. Further, findings from the broader literature on the efficiency of telemonitoring are limited (e.g. due to a small number of studies and poor study designs).

Equity

At this stage, there is no data to assess whether telemonitoring for HF patients in the Czech Republic widens or narrows existing health inequalities.

Based on the broader literature, there is evidence to suggest telemonitoring can both increase as well as decrease existing health inequalities (e.g. digital exclusion while on the other hand increasing access to difficult-to-reach patients).

Evidence‑base

The evidence supporting the impact of telemonitoring of HF on health outcomes (i.e. effectiveness) is of high quality as it relies on systematic reviews and meta‑analyses largely covering randomised controlled trials. The evidence supporting its efficiency however is less developed and is very much lacking in regard to equity.

Extent of coverage

Telemonitoring for HF patients in the Czech Republic only covers one city and a handful of eligible patients. Given nearly 300 000 people suffer from HF in the country, there is scope to greatly increase the intervention’s coverage.

Effectiveness

Evidence to assess whether telemonitoring for patients with advanced HF in the Czech city of Olomouc is meeting its three objectives2 is limited. According to a 2017 European Commission report, the intervention was found to improve medication adherence and access to healthcare professionals (specific indicators for the latter two measures were not provided) (Gutter, 2017[]). Details on the methodological study design associated with these results are not available meaning the effectiveness of this specific intervention cannot be verified.

Evidence of similar interventions operating in other countries, however, is well established (see Table 12.1). Specifically, recent systematic reviews and meta‑analyses reveal this type of intervention is effective at reducing all-cause and HF mortality.

Table 12.1. Evidence summarising the effectiveness of telemonitoring for HF patients

|

Outcome |

Evidence |

Source |

|---|---|---|

|

All-cause mortality |

40% decrease in the odds of all-cause mortality at 180 days (odds ratio (OR) = 0.6) (no statistical significant change at 365 days) |

Systematic review by (Pekmezaris et al., 2018[]) |

|

OR = 0.53 in favour of the treatment group |

Systematic review and network meta‑analysis by (Kotb et al., 2015[])* |

|

|

OR = 0.81 in favour of treatment group |

Systematic review and meta‑analysis by (Yun et al., 2018[]) |

|

|

Risk ratio (RR) = 0.66 meaning the treatment group have 0.66 times the risk of dying compared to the control group |

Overview of systematic reviews by (Bashi et al., 2017[]) |

|

|

HF mortality |

OR = 0.39 in favour of treatment group |

Systematic review by (Pekmezaris et al., 2018[]) |

|

OR = 0.68 in favour of treatment group |

Systematic review and meta‑analysis by (Yun et al., 2018[]) |

Note: *The review by (Kotb et al., 2015[]) included “telephone support, telemonitoring, telephone support and telemonitoring together, video monitoring or monitoring by ECG”, whereas the other reviews relied on studies measuring the impact of telemonitoring using transmission of biological information.

Efficiency

Reports from a previous European Commission report noted that telemonitoring for HF patients in Olomouc resulted in a 40% reduction in hospitalisations (Gutter, 2017[]). However, similar to the findings reported under “Effectiveness”, these results cannot be verified. No further studies evaluating the economic impact of the intervention are available, for this reason, the remainder of this section focuses on investment costs for telemonitoring facilities in the Czech Republic as well as summarising economic studies from similar interventions operating in other countries.

The Czech national health service does not reimburse telemonitoring services for advanced HF patients. For this reason, the intervention is reliant on funds from projects undertaken by the Czech National eHealth Centre, operated by the Ministry of Health, as well as funds from project partners. It is estimated that an investment between EUR 1 000 – 5 000 per eligible patient is needed to operate the intervention (however, information on the timeline for investment was not provided) (Gutter, 2017[]). Given the average hospitalisation cost for chronic HF patients in the Czech Republic is approximately EUR 3 500 (or CZK 84 900), such an intervention has the potential to be not only cost-effective, but even cost-saving (Pavlušová et al., 2018[]).

Telemonitoring can reduce costs by performing routine status checks remotely, detecting patient deterioration at an early stage thereby limiting the potential for health problems to escalate as well as reducing patient travel time. Several studies from the academic literature support this argument while others report opposing results. For example, regarding telemonitoring’s impact on utilisation, some studies show a decrease in hospitalisations but an increase in emergency department visits, while the most recent systematic review found most studies recorded no change in utilisation (see Table 12.2). The impact of telemonitoring on total costs was also assessed, which reported mixed, inconclusive results (see Table 12.3).

Table 12.2. Evidence summarising the impact of telemonitoring for HF on utilisation

|

Outcome |

Evidence |

Source |

|---|---|---|

|

Hospitalisations |

No statistically significant change in all-cause hospitalisation |

Systematic review by (Pekmezaris et al., 2018[]) |

|

The number of hospitalisations was significantly reduced in 38% (9/24) of studies |

Systematic review by (Auener et al., 2021[]) |

|

|

OR = 0.64 in favour of the treatment group |

Systematic review and network meta‑analysis by (Kotb et al., 2015[]) |

|

|

Emergency department visits |

Emergency department visits were reduced in 13% (1/8) of studies. |

Systematic review by (Auener et al., 2021[]) |

|

OR = 1.51 in favour of the control group (i.e. telemonitoring patients more likely to access emergency care) |

Systematic review by (Pekmezaris et al., 2018[]) |

|

|

RR = 1.37 in favour of the control group |

Meta‑analysis of randomised controlled trials by Klersy et al. (2016[]) |

|

|

Total healthcare utilisation |

Most studies showed no effect of telemonitoring on healthcare utilisation |

Systematic review by (Auener et al., 2021[]) |

|

RR ranging from 0.72 to 0.93 in favour of the treatment group |

Overview of systematic reviews by (Bashi et al., 2017[]) |

|

|

RR = 0.56 in favour of the treatment group |

Meta‑analysis of randomised controlled trials by Klersy et al. (2016[]) |

Table 12.3. Evidence summarising the impact of telemonitoring for HF on costs

|

Source |

Economic benefit (Yes/No) |

Details |

|---|---|---|

|

Systematic review by (Auener et al., 2021[]) |

Unclear |

Mixed results – 3 studies found an increase in healthcare costs, 3 reported a reduction and 4 found no significant differences |

|

Systematic review by (Jiang, Ming and You, 2019[]) |

Yes – but the number of studies is limited |

An included study from the United Kingdom recorded an ICER (incremental cost-effectiveness ratio) of GBP 11 873 per QALY (quality-adjusted life year), which is well below the willingness-to-pay threshold* Findings from an economic evaluation of a wireless pulmonary artery pressure sensor was also found to be cost-effective in the United Kingdom and the United States |

|

Literature review by (Grustam et al., 2014[]) |

Yes – but the quality of evidence is low |

The few studies that included an economic evaluation found telemonitoring was cost saving and led to marginal improvements in effectiveness. Overall, however, the quality of studies was low making findings unreliable. |

Note: *The cost threshold for funding healthcare services in England (as set out by NICE (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence)) is between GBP 20 000 and GBP 30 000.

Equity

Given there are no studies evaluating the impact this intervention, it is not possible to assess its impact on equity. Drawing upon the broader literature regarding digital health technologies and equity, there is evidence to suggest telemonitoring can both widen as well as narrow existing health inequalities (e.g. between socio-economic groups) (Table 12.4).

Table 12.4. The impact of telemonitoring and equity

|

Narrow existing health inequalities |

Widen existing health inequalities |

|---|---|

|

Telemonitoring has the potential to improve access to healthcare in particular patients who live in difficult-to-reach areas as well as patients with mobility issues |

Telemonitoring risks digitally excluding vulnerable populations such as older people, disabled people, people in remote locations as well as those on low incomes. Examples of digital exclusion are listed below: ‒ Those in regional/rural areas have lower levels of access to the internet ‒ Older people are less likely to own a smartphone or have access to the internet in their home* ‒ Those with a lower socio-economic status are less likely to be able to afford digital devices |

|

Overweight and diabetes are two key risk factors for developing heart failure. Given these risk factors are more prominent among disadvantaged groups (e.g. those with a lower level of education), telemonitoring for HF patients has the potential to narrow existing inequalities. |

Note: * As part of the trial, patients have the option to use devices provided by the hospital. This option however may not be economic feasible when scaled-up across the country.

Source: Oliveria Hashiguguchi (2020[]) =, “Bringing healthcare to the patient: An overview of the use of telemedicine in OECD countries”, https://doi.org/10.1787/8e56ede7-en; OECD (2019[]), The Heavy Burden of Obesity: The Economics of Prevention, https://doi.org/10.1787/67450d67-en.

Evidence‑based

Evidence supporting the impact of the Czech Republic’s telemonitoring for advanced HF patients is limited. Further, findings that are available do not detail the design of the study’s methodology. For this reason, an evaluation of the quality of evidence supporting this specific intervention is not possible. Instead, this section (i.e. Box 12.4) details the quality of studies used in systematic reviews and meta‑analyses that support the effectiveness and efficiency of telemonitoring for HF patients.

Overall, the evidence supporting the effectiveness of telemonitoring for HF patients is strong given there are a large number of systematic reviews and meta‑analysis based on randomised controlled trials (RCTs), which are considered high quality evidence. The evidence supporting efficiency is less developed.

Box 12.4. Quality of evidence supporting telemonitoring for HF patients

This box summarises the methodological quality of studies outlined under the sections “Effectiveness” and “Efficiency”. The purpose of this exercise is to verify the validity of findings regarding the impact of telemonitoring for HF patients.

Effectiveness

Pekmezaris et al. (2018[]) performed a systematic review and meta‑analysis of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) published between 2001 and 2016. RCTs are considered the “gold-standard” in establishing causality and therefore strengthen the validity of findings (i.e. that telemonitoring for patients with HF reduces mortality).

Yun et al. (2018[]) also performed a systematic review and meta‑analysis to assess the impact of telemonitoring for HF patients on all-cause mortality. Thirty-seven studies met the inclusion criteria covering nearly 10 000 patients. The authors used Cochrane RoB (risk of bias) tool to assess the quality of studies, which found the overall risk of detection bias was “low”.

Bashi et al. (2017[]) performed an overview of 19 systematic reviews. The authors assessed the quality of each systematic review using AMSTAR (Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews) tool. Of the 19 systematic review, 5% were rated as high quality, 68% as moderate quality and 26% as low quality.

Klersy et al. (2016[]) performed a systematic review and meta‑analysis of 11 RCTs. The quality of studies was assessed as GRADE guidelines with thresholds for inclusion set.

Kotb et al. (2015[]) performed a systematic review and network meta‑analysis covering RCTs (n = 30 studies). Similar to (Bashi et al., 2017[]), the authors used the AMSTAR tool to assist the quality of included RCTs. Of the 30 included studies, 17 were assessed as high quality, 10 as moderate and three as low quality.

Efficiency

It is important to note that results for efficiency were inconclusive with reviews findings both increases and decreases in costs – see “Efficiency” for further details.

Auner et al. (2021[]) undertook a systematic review of 29 studies which included RTCs, non-randomised trials as well as observational studies. Each study was assessed against the Cochrane RoB tool, which found the following results: 75% of RCT studies showed some risk of bias while 75% of non-randomised trials shows serious or critical risk of bias.

Jian et al. (2019[]) performed a systematic review of 14 economic studies, which were quality-checked against the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS). Fourteen of the studies were rated as good quality, four as moderate and one as low.

Grustam et al. (2014[]) performed a literature review of 32 articles related to telehealth interventions for chronic HF patients, including telemonitoring. The majority of studies analysed reported findings from RCTs.

Extent of coverage

At present, telemonitoring for advanced HF patients is only available to eligible patients living within the city of Olomouc. This equates to between 100 and 249 people. However, there is only enough equipment for 40 patients. Since 285 745 people in the Czech Republic live with HF (as of 20183), it is clear there is significant potential to extend the coverage of this intervention (Táborský et al., 2021[]).

Policy options to enhance performance

This section outlines policies to enhance the performance of Olomouc’s telemonitoring programme for HF patients against each of the five best practice criteria.

Enhancing effectiveness

Table 12.5 compares best practices related to telemonitoring for HF patients from the literature with characteristics of the model in the Czech Republic. The analysis reveals the current model in the Czech Republic aligns with international recommendations; therefore, no specific policies to enhance effectiveness are included in this section. This does not mean, however, there is not room for improvement; instead, it highlights the importance of undertaking a rigorous evaluation to identify policy enhancement options (see “Enhancing the evidence base”).

Table 12.5. Best practice for telemonitoring for HF patients

|

Intervention characteristic |

Details |

Included in the Czech Republic model? |

|---|---|---|

|

Frequent data transmission |

Frequent transmission of data between patients and healthcare professionals is associated with a decreased risk of all-cause mortality (relative risk (RR) = 0.81) (Yun et al., 2018[]) |

✓ |

|

Monitoring medication adherence |

Interventions that actively monitor a patients adherence to prescribed medication is linked to lower rates of all-cause mortality (RR = 0.73) (Yun et al., 2018[]) |

✓ |

|

Collecting biological parameters |

Telemonitoring interventions that collect at least three biological parameters (e.g. weight and blood pressure) from a patient or electrocardiograph data are linked to reduced rates of all-cause mortality and hospitalisations (Auener et al., 2021[]). |

✓ |

Enhancing efficiency

As outlined under “Efficiency”, telemonitoring for HF patients has the potential to improve efficiency within the healthcare system. However, at present it is unlikely to be cost-effective in the Czech Republic given the small number of participating patients. For this reason, once an evaluation of the pilot in Olomouc is complete (see “Enhancing the evidence‑base”), and assuming positive results, policy makers should prioritise expanding the intervention’s reach across the country. By doing so, the average cost per patient will markedly fall (Auener et al., 2021[]).

Enhancing equity

There is paucity of studies of telemonitoring studies that stratify data by different patient characteristics. Such information is necessary for evaluating the impact of an intervention on existing health inequalities. Policies to ensure telemonitoring for HF patients in the Czech Republic lessens existing inequalities should be derived from future programme evaluations (as discussed under “Enhancing the evidence‑base”). Nevertheless, given it is known that vulnerable populations such as the elderly and those with a low socio-economic status (SES) are at greater risk of being digitally excluded, it is important that specific efforts are made to ensure participation by these population groups. For example, including representatives of disadvantaged groups in the design of the intervention, and providing targeted training and support.

Enhancing the evidence‑base

There has not been a robust outcome or economic evaluation of telemonitoring for HF patients in Olomouc. An evaluation should therefore be of top priority to policy makers. Tips on how to undertake a thorough evaluation are summarised in this section with a focus on what indicators to collect (see Box 12.5).

The indicators listed are useful for undertaking an outcome evaluation (i.e. whether the intervention achieved its desired objectives). For greater insight, outcomes evaluations can be paired with a process evaluation which assesses whether the intervention was implemented as planned. For example, if an outcome evaluation reveals no major change in key outcome indicators, a process evaluation will inform researchers whether this is due to poor implementation or not. For further details on undertaking an evaluation, see OECD’s Guidebook on Best Practices in Public Health (OECD, 2022[]).

Box 12.5. Indicators for an evaluation of telemonitoring programs for HF patients

This box outlines the types of indicators important when undertaking an evaluation of the telemonitoring programme for HF patients in Olomouc, Czech Republic. Italicised indicators are those considered essential.

Effectiveness

All-cause mortality (e.g. at 180 and 365 days)

HF-related mortality

Patient feedback: quality of life*, perceived health status, activities of daily living etc.

Efficiency

All-cause hospital admissions (e.g. at 180 days)

All-cause emergency department admissions

HF-related hospital admissions

HF-related emergency department admissions

Length of stay in hospital (all-cause and HF-related)

Use of other healthcare services such as home visits, outpatient visits, and specialist visits)

Equity

To the extent possible, stratify effectiveness and efficiency indicators to assess the intervention’s impact on health inequalities. Example ways stratify data are outlined below:

Age and gender

Income

Education level

Ethnicity

Location (e.g. rural, regional or urban).

Economic evaluation

Economic evaluations assess costs in relation to benefits. Results from these evaluations help policy makers maximise outcomes with a limited set of resources. There are several cost items to collect for this evaluation including labour, capital, consumables, administrative and overhead costs.

Note: *There are a range of available questionnaires such as HeartQoL (by the European Association of Preventative Cardiology), EQ‑5D‑5L, the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire and the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire.

Source: OECD (2022[]), “Guidebook on Best Practices in Public Health”, https://doi.org/10.1787/4f4913dd-en; Pekmezaris et al. (2018[]), “Home Telemonitoring In Heart Failure: A Systematic Review And Meta-Analysis”, https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05087; Yun et al. (2018[]), “Comparative Effectiveness of Telemonitoring Versus Usual Care for Heart Failure: A Systematic Review and Meta‑analysis”, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cardfail.2017.09.006; Auener et al. (2021[]), “The Effect of Noninvasive Telemonitoring for Chronic Heart Failure on Healthcare Utilisation: Systematic Review”, https://doi.org/10.2196/26744.

Enhancing extent of coverage

As outlined under “Extent of coverage”, to date, very few patients with advanced heart failure have access to this intervention in the Czech Republic. Following an evaluation of the pilot in Olomouc, assuming positive results and no major negative side effects, this intervention should be expanded to reach the thousands of people in the country experiencing HF.

Based on feedback from intervention administrators in Olomouc, there are no major barriers to scaling-up this intervention in the region (Gutter, 2017[]). However, as discussed under the section on “Transferability”, it is important to take into the local context of where an intervention is being transferred and to adapt the intervention accordingly.

“This good practice can be replicated in other hospitals providing medical services for patients with heart failure.” (Gutter, 2017[])

Transferability

This section explores the transferability of telemonitoring for HF patients and is broken into three components: 1) an examination of previous transfers; 2) a transferability assessment using publicly available data; and 3) additional considerations for policy makers interested in transferring this intervention.

Previous transfers

Telemonitoring for patients with HF in the city of Olomouc has neither been transferred to another country nor scaled-up across the Czech Republic. However, several countries across the OECD have already implemented similar if not near identical interventions indicating telemonitoring for HF patients is highly transferable (see Box 12.6).

Box 12.6. International telemonitoring for HF patients: Country examples

Telemonitoring is growing increasingly popular among OECD countries, but as stated by a recent OECD report, few of these interventions operate at the national level. Rather the majority of telemonitoring interventions are small-scale pilots involving just a few thousand patients. Example countries are listed below:

Countries with national level interventions: Sweden, Spain and Japan

Example countries with pilot interventions: Austria, Denmark, Portugal, the United Kingdom.

Note: The list of countries listed is not exhaustive.

Source: Oliveria Hashiguguchi (2020[]), “Bringing healthcare to the patient: An overview of the use of telemedicine in OECD countries”, https://doi.org/10.1787/8e56ede7-en.

The transferability potential of this intervention is supported by administrators from the University Hospital Olomouc, which operate this intervention. Specifically, intervention administrators state that the target population in Olomouc reflects the “standard [EU] population” as it has a medium developed economy and a population with average rates of chronic disease. For this reason, it is suitable for transferral across the EU.

“The good practice is, thanks to use EBM [evidence‑based medicine] methods, highly transferable to other hospitals in the region, the whole country and, with possible adjustments to other medical systems, also to further EU countries.” (Gutter, 2017[])

In order to be prepared to implement telemedicine interventions (such as telemonitoring) successfully, policy makers can draw upon the validated Telemedicine Community Readiness Model (TCRM) tool. The tool is free and available online, http://care4saxony.de/?page_id=3837.

Transferability assessment

The following section outlines the methodological framework to assess transferability and results from the assessment.

Methodological framework

A few indicators to assess the transferability of telemonitoring for HF were identified (see Table 12.6). Indicators were drawn from international databases and surveys to maximise coverage across OECD and non-OECD European countries. Please note, the assessment is intentionally high level given the availability of public data covering OECD and non-OECD European countries.

Table 12.6. Indicators to assess transferability – Telemonitoring for HF patients

|

Indicator |

Reasoning |

Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

|

Population context |

||

|

ICT Development Index* |

Telemonitoring is more transferable to digitally advanced countries |

🡹 value = more transferable |

|

Individuals using the Internet for seeking health information – last 3 m (%) |

Telemonitoring is more transferable to a population where people are more comfortable accessing digital health services |

🡹 value = more transferable |

|

Self-reported use of home care services |

Telemonitoring is more transferrable to a population that already uses home care services |

🡹 value = more transferable |

|

Sector context (digital health sector) |

||

|

Remote patient monitoring programmes |

Telemonitoring for HF patients is more transferable to countries which already have telemonitoring programs in place (e.g. for diabetes) |

‘Yes’ = more transferable |

|

Legislation exists to protect the privacy of personally identifiable data of individuals, irrespective of whether it is in paper or digital format |

Telemonitoring requires to transfer patient data. Therefore, TeleHomeCare is more likely to be successful in countries with legislation to protect patient data. |

‘Yes’ = more transferable |

|

% of tertiary institutions (public and private) that offer ICT for health (eHealth) courses |

Telemonitoring is more transferable if health professional students receive eHealth training |

🡹 value = more transferable |

|

% of institutions or associations offering in-service training in the use of ICT for health as part of the continuing education of health professionals |

Telemonitoring is more transferable if health professionals have appropriate eHealth training |

🡹 value = more transferable |

|

Political context |

||

|

A national eHealth policy or strategy exists |

Telemonitoring is more likely to be successful if national policies support eHealth |

‘Yes’ = more transferable |

|

A dedicated national telehealth policy or strategy exists |

Telemonitoring is more likely to be successful if the government is supportive of telehealth |

‘Yes’ = more transferable |

|

Economic context |

||

|

% of funding contribution for eHealth programmes provided by public funding sources over the previous two years |

Telemonitoring is more likely to be successful in a country whose government spends more on eHealth |

🡹 value = more transferable |

|

Special funding is allocated for the implementation of the national eHealth policy or strategy |

Telemonitoring is more likely to be successful if there already is allocated funding for eHealth |

‘Yes’ = more transferable |

Note: *The ICT development index represents a country’s information and communication technology capability. It is a composite indicator reflecting ICT readiness, intensity and impact (ITU, 2020[]).

Source: WHO (2019[]), “Existence of operational policy/strategy/action plan to reduce unhealthy diet related to NCDs (Noncommunicable diseases)”, https://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.imr.NCD_CCS_DietPlan?lang=en; ITU (2020[]), “The ICT Development Index (IDI): conceptual framework and methodology”, https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Pages/publications/mis/methodology.aspx; OECD (2019[]), “Individuals using the Internet for seeking health information – last 3 m (%) (all individuals aged 16‑74)”; European Commission (2018[]), “Benchmarking Deployment of eHealth among General Practitioners (2018)”, https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/d1286ce7-5c05-11e9-9c52-01aa75ed71a1; World Bank (2017[]), “GNI per capita, PPP (constant 2017 international $)”, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GNP.PCAP.PP.KD; Maier and Aiken (2016[]), “Task shifting from physicians to nurses in primary care in 39 countries: a cross-country comparative study”, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckw098; WHO (2015[]), “Atlas of eHealth country profiles: The use of eHealth in support of universal health coverage”, https://www.afro.who.int/publications/atlas-ehealth-country-profiles-use-ehealth-support-universal-health-coverage.

Results

Table 12.7 provides a summary of transferability indicator values among OECD and EU countries compared to the Czech Republic. Key findings from the analysis according to each transferability context is below:

Population context: relative to the Czech Republic, populations in OECD and EU countries have a higher ICT index indicating greater confidence using digital tools (7.20 versus 7.34 average). Further, the use of home healthcare services is markedly higher on average across the OECD/EU when compared to the Czech Republic (23% versus 29%).

Digital health sector context: based on available indicators, the digital health sector among OECD/EU countries is just as advanced or more advanced than the Czech Republic. For example, all countries with available data have some form of telemonitoring programme in place and have legislation in place to protect patient data collected digitally (therefore patients are more likely to feel comfortable sharing information on their vital signs remotely).

Political context: unlike Czech Republic, 74% of OECD/EU countries with available data have a national eHealth policy or strategy in place to support telemonitoring programs. Conversely, a large proportion of countries (44%) do not have a plan or strategy specific to telehealth interventions, which may hinder implementation efforts.

Economic context: compared to the Czech Republic most OECD/EU governments contribute a large amount to eHealth programs thereby supporting the financial sustainability of telemonitoring programs. Further, unlike the Czech Republic, the majority of OECD/EU governments (86% with available data) provide additional “special funding” for their eHealth strategy, which again contributes to financial sustainability.

Table 12.7. Transferability assessment by country (OECD and non-OECD European countries) – Telemonitoring for HF patients

A darker shade indicates telemonitoring for HF patients is more suitable for transferral in that particular country

|

ICT Development Index |

% using the Internet for seeking health information – last 3 m |

Self-reported use of home care services by sex, age and level of activity limitation |

Remote patient monitoring programmes |

Legislation exists to protect the privacy of personally identifiable data of individuals |

% tertiary institutions (public and private) that offer ICT for health (eHealth) courses |

% institutions or associations offering in-service training in the use of ICT for health as part of the continuing education of health professionals |

A national eHealth policy or strategy exists |

A dedicated national telehealth policy or strategy exists |

% funding contribution for eHealth programmes provided by public funding sources over the previous two years |

Special funding is allocated for the implementation of the national eHealth policy or strategy |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Czech Republic |

7.20 |

0.56 |

23.00 |

Yes |

Yes |

Medium |

No response |

No |

Combined |

Low |

No |

|

Australia |

8.20 |

0.42 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

Medium |

High |

Yes |

No |

Very high |

n/a |

|

Austria |

7.50 |

0.53 |

18.00 |

Yes |

Yes |

Low |

Low |

No |

No |

Very high |

Yes |

|

Belgium |

7.70 |

0.49 |

45.10 |

Yes |

Yes |

Low |

Low |

Yes |

Combined |

Very high |

Yes |

|

Bulgaria |

6.40 |

0.34 |

22.30 |

Yes |

Yes |

Medium |

Medium |

Yes |

Combined |

Low |

Yes |

|

Canada |

7.60 |

0.59 |

n/a |

n/a |

Yes |

High |

Low |

Yes |

No |

Very high |

n/a |

|

Chile |

6.10 |

0.27 |

n/a |

n/a |

Yes |

Low |

Low |

Yes |

No |

Very high |

n/a |

|

Colombia |

5.00 |

0.41 |

n/a |

n/a |

Yes |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

Yes |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Costa Rica |

6.00 |

0.44 |

n/a |

n/a |

Yes |

Medium |

Medium |

Yes |

Yes |

Very high |

n/a |

|

Croatia |

6.80 |

0.53 |

16.40 |

Yes |

Yes |

Low |

Medium |

Yes |

Yes |

Very high |

Yes |

|

Cyprus |

6.30 |

0.58 |

23.50 |

Yes |

Medium |

Low |

Yes |

Combined |

Very high |

No |

|

|

Denmark |

8.80 |

0.67 |

51.40 |

Yes |

Yes |

Medium |

Very high |

Yes |

Yes |

Very high |

Yes |

|

Estonia |

8.00 |

0.60 |

12.70 |

Yes |

Yes |

Medium |

Low |

Yes |

No |

Very high |

Yes |

|

Finland |

8.10 |

0.76 |

43.60 |

Yes |

Yes |

Medium |

Medium |

Yes |

Combined |

Very high |

Yes |

|

France |

8.00 |

0.50 |

56.50 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Germany |

8.10 |

0.66 |

27.60 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Greece |

6.90 |

0.50 |

20.60 |

Yes |

Yes |

Medium |

Medium |

Yes |

Combined |

Very high |

Yes |

|

Hungary |

6.60 |

0.60 |

24.80 |

Yes |

Yes |

Low |

n/a |

No |

No |

Very high |

No |

|

Iceland |

8.70 |

0.65 |

34.20 |

n/a |

Yes |

Very high |

Very high |

Yes |

No |

Very high |

Yes |

|

Ireland |

7.70 |

0.57 |

51.90 |

n/a |

Yes |

n/a |

Low |

Yes |

No |

Low |

Yes |

|

Israel |

7.30 |

0.50 |

n/a |

Yes |

Yes |

High |

Low |

No |

Yes |

Very high |

Yes |

|

Italy |

6.90 |

0.35 |

35.40 |

Yes |

Yes |

Low |

High |

Yes |

Yes |

Very high |

Yes |

|

Japan |

8.30 |

n/a |

n/a |

Yes |

Yes |

n/a |

n/a |

Yes |

No |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Korea |

8.80 |

0.50 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Latvia |

6.90 |

0.48 |

15.70 |

Yes |

Low |

Low |

Yes |

Combined |

Low |

Yes |

|

|

Lithuania |

7.00 |

0.61 |

18.30 |

Yes |

Yes |

Medium |

Low |

Yes |

Yes |

High |

No |

|

Luxembourg |

8.30 |

0.58 |

24.40 |

Yes |

Yes |

Low |

Low |

Yes |

Combined |

Very high |

Yes |

|

Malta |

7.50 |

0.59 |

42.50 |

Yes |

Yes |

Very high |

Very high |

No |

No |

Very high |

n/a |

|

Mexico |

4.50 |

0.50 |

n/a |

Yes |

Yes |

Medium |

Low |

No |

No |

High |

n/a |

|

Netherlands |

8.40 |

0.74 |

59.20 |

Yes |

Yes |

High |

High |

Yes |

Combined |

Very high |

Yes |

|

New Zealand |

8.10 |

n/a |

n/a |

Yes |

Yes |

Medium |

Very high |

Yes |

No |

Low |

n/a |

|

Norway |

8.40 |

0.69 |

27.20 |

Yes |

Yes |

Low |

Medium |

Yes |

Yes |

Very high |

Yes |

|

Poland |

6.60 |

0.47 |

20.80 |

Yes |

Yes |

High |

Medium |

Yes |

Combined |

Very high |

Yes |

|

Portugal |

6.60 |

0.49 |

17.40 |

Yes |

Yes |

Low |

Low |

No |

Yes |

High |

Yes |

|

Romania |

5.90 |

0.33 |

16.90 |

n/a |

Yes |

n/a |

n/a |

Yes |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Slovak Republic |

6.70 |

0.53 |

18.30 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Slovenia |

7.10 |

0.48 |

24.70 |

Yes |

Yes |

High |

High |

No |

No |

Very high |

Yes |

|

Spain |

7.50 |

0.60 |

39.80 |

Yes |

Yes |

Low |

Medium |

No |

No |

Very high |

Yes |

|

Sweden |

8.50 |

0.62 |

22.30 |

Yes |

Yes |

Very high |

Very high |

Yes |

No |

Very high |

Yes |

|

Switzerland |

8.50 |

0.67 |

n/a |

Yes |

Yes |

Low |

Very high |

Yes |

No |

Low |

Yes |

|

Türkiye |

5.50 |

0.51 |

2.90 |

Yes |

Yes |

n/a |

n/a |

No |

Combined |

Low |

Yes |

|

United Kingdom |

8.50 |

0.67 |

27.50 |

Yes |

Yes |

Medium |

High |

Yes |

Yes |

Very high |

Yes |

|

United States |

8.10 |

0.38 |

n/a |

Yes |

Yes |

Low |

Low |

Yes |

No |

n/a |

n/a |

Note: *Combined with eHealth policy or strategy. n/a indicates data is missing.

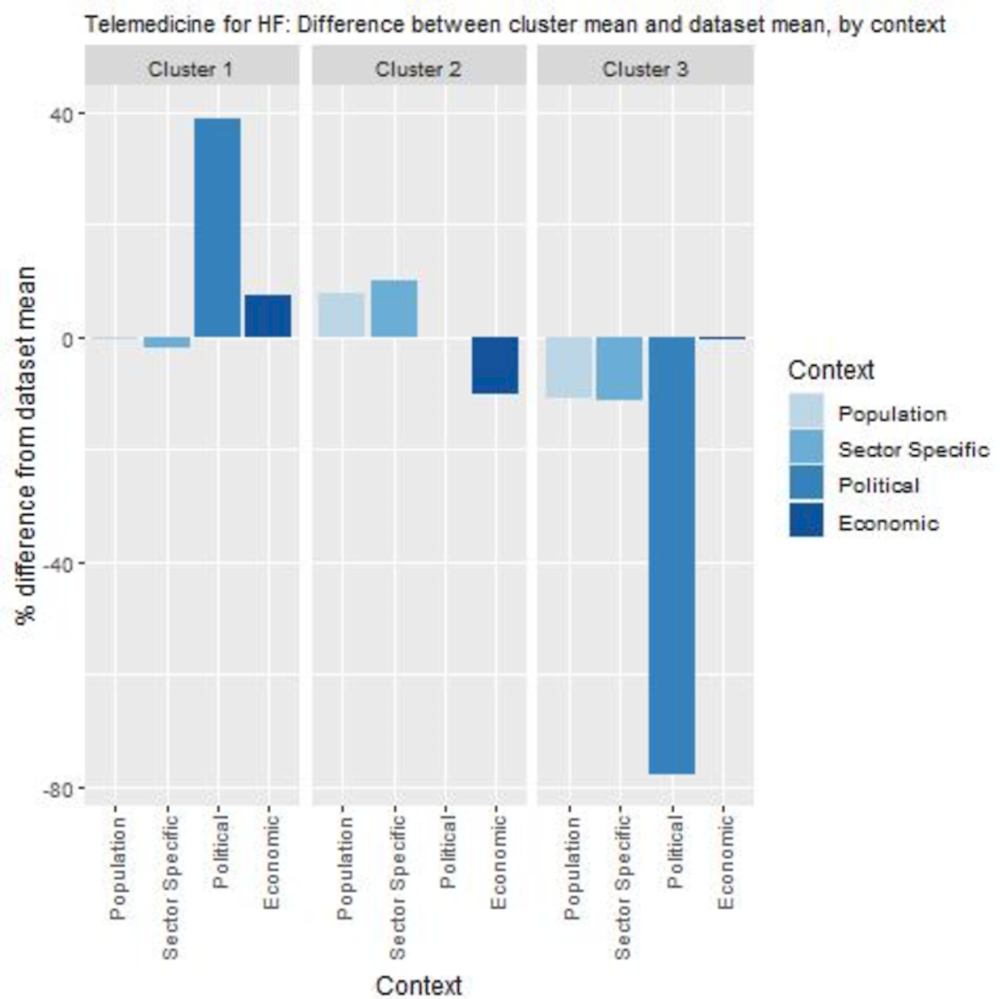

To help consolidate findings from the transferability assessment above, countries have been clustered into one of three groups, based on indicators reported in Table 12.6. Countries in clusters with more positive values have the greatest transfer potential. For further details on the methodological approach used, please refer to Annex A.

Key findings from each of the clusters are below with further details in Figure 12.1 and Table 12.8:

Based on chosen indicators, countries in cluster one will likely receive political and economic support for telemonitoring interventions. However, prior to implementation the digital sector’s readiness to implement such an intervention should be assessed (e.g. using the TCRM tool). Czech Republic, which is the owner of this intervention, falls under this cluster.

Countries in cluster two have a population and digital health sector ready to implement telemonitoring interventions. Nevertheless, the financial sustainability of telemonitoring interventions should be confirmed given governments in these countries typically contribute less to eHealth programs (as a proportion of total spending on eHealth).

Although most countries in cluster three have telemonitoring interventions in place already, policy makers are encouraged to thoroughly assess the potential to transfer this intervention – e.g. to assess workforce readiness and ensure telemonitoring aligns with overall political objectives.

Figure 12.1. Transferability assessment using clustering – Telemonitoring for HF patients

Note: Bar charts show percentage difference between cluster mean and dataset mean, for each indicator.

Table 12.8. Countries by cluster – Telemonitoring for HF patients

|

Cluster 1 |

Cluster 2 |

Cluster 3 |

|---|---|---|

|

Belgium Bulgaria Costa Rica Croatia Cyprus Czech Republic Denmark Finland Greece Italy Luxembourg Netherlands Norway Poland Türkiye United Kingdom |

Australia Canada Chile Estonia Iceland Ireland Latvia Lithuania New Zealand Sweden Switzerland United States |

Austria Hungary Israel Malta Mexico Portugal Slovenia Spain |

Note: The following countries were omitted due to high levels of missing data: Colombia, France, Germany, Japan, Korea, Romania and the Slovak Republic.

New indicators to assess transferability

Data from publicly available datasets alone is not sufficient to assess the transferability of public health interventions. Box 12.7 outlines several new indicators policy makers could consider before transferring telemonitoring for HF patients.

In addition to the indicators below, policy makers can refer to the TCRM (Telemedicine Community Readiness Model) tool as previously detailed.

Box 12.7. New indicators, or factors, to consider when assessing transferability – Telemonitoring for HF patients

In addition to the indicators within the transferability assessment, policy makers are encouraged to collect information for the following indicators:

Population context

Is there a desire among patients to replace traditional healthcare processes with telemonitoring?

Do patients use existing telemonitoring interventions? (e.g. for other diseases such as diabetes)

Sector specific context (digital health sector)

Is there a desire among health professionals to replace traditional healthcare processes with telemonitoring?

What, if any, compatible or competing interventions exist?

Is the essential infrastructure available to implement telemonitoring for HF patients?

Does telemonitoring for HF patients comply with regulatory requirements?

Political context

Has the intervention received political support from key decision-makers?

Has the intervention received commitment from key decision-makers?

Economic context

What is the cost of implementing and operating the intervention in the target setting and to whom?

Conclusion and next steps

In 2013, the University Hospital Olomouc in the Czech Republic introduced a telemonitoring intervention for HF patients. The intervention shares patient vital signs with health professionals on a daily basis including blood pressure, medication adherence and weight. The majority of indicators shared with health professionals is collected automatically through either an implanted defibrillator or pacemaker.

No evaluation of this pilot intervention is currently available therefore it is not possible to determine its impact on patient outcomes, experiences as well as costs. A review of similar interventions in the literature indicate telemonitoring for HF patients is effective at reducing all-cause and HF-related mortality, however, its impact on costs is less clear.

The design of Olomouc’s telemonitoring intervention aligns with international best practice given it involves frequent transmission of biological parameters including medication adherence, weight and blood pressure. However, prior to scaling-up this intervention across the Czech Republic, a robust outcome and process evaluation is recommended. The types of indicators to measure the intervention’s impact are outlined in this case study and include data routinely collected by hospitals.

Several OECD and EU countries have telemonitoring programs for patients with HF including Sweden and Japan highlighting the intervention’s transferability potential. In the Czech Republic, administrators in Olomouc believe the intervention is “highly transferable to other hospitals in the region”.

Box 12.8 outlines next steps for policy makers and funding agencies in regards to telemonitoring for advanced HF patients.

Box 12.8. Next steps for policy makers and funding agencies – Telemonitoring for HF patients

Next steps for policy makers and funding agencies to enhance telemonitoring for HF patients are listed below:

Prioritise undertaking an outcome and process of evaluation of this pilot intervention

Undertaking preliminary analysis to determine which hospitals in the Czech Republic are interested in this intervention and their readiness for telemonitoring

Identify patients in the Czech Republic who are at risk of being excluded from this intervention and develop strategies to ensure their participation

Share findings from this case study with policy makers interested in expanding digital health opportunities.

References

[13] Auener, S. et al. (2021), “The Effect of Noninvasive Telemonitoring for Chronic Heart Failure on Health Care Utilization: Systematic Review”, Journal of Medical Internet Research, Vol. 23/9, p. e26744, https://doi.org/10.2196/26744.

[11] Bashi, N. et al. (2017), “Remote Monitoring of Patients With Heart Failure: An Overview of Systematic Reviews”, Journal of Medical Internet Research, Vol. 19/1, p. e18, https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.6571.

[22] European Commission (2018), Benchmarking Deployment of eHealth among General Practitioners (2018), https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/d1286ce7-5c05-11e9-9c52-01aa75ed71a1.

[14] for the Health Economics Committee of the European Heart Rhythm Association (2016), “Effect of telemonitoring of cardiac implantable electronic devices on healthcare utilization: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials in patients with heart failure”, European Journal of Heart Failure, Vol. 18/2, pp. 195-204, https://doi.org/10.1002/ejhf.470.

[16] Grustam, A. et al. (2014), “Cost-effectiveness of telehealth interventions for chronic heart failure patients: A literature review”, International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care, Vol. 30/1, pp. 59-68, https://doi.org/10.1017/s0266462313000779.

[7] Gutter, Z. (2017), Olomouc region, Czech republic: Telehealth service for patients with advanced heart failure, https://www.scirocco-project.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/SciroccoGP-Olumouc-3-Telehealth-for-CHF-Patients.pdf.

[19] ITU (2020), The ICT Development Index (IDI): conceptual framework and methodology, https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Pages/publications/mis/methodology.aspx (accessed on 26 February 2021).

[15] Jiang, X., W. Ming and J. You (2019), “The Cost-Effectiveness of Digital Health Interventions on the Management of Cardiovascular Diseases: Systematic Review”, Journal of Medical Internet Research, Vol. 21/6, p. e13166, https://doi.org/10.2196/13166.

[24] Maier, C. and L. Aiken (2016), “Task shifting from physicians to nurses in primary care in 39 countries: a cross-country comparative study”, The European Journal of Public Health, Vol. 26/6, pp. 927-934, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckw098.

[1] Mayo Clinic (2022), Heart failure, https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/heart-failure/symptoms-causes/syc-20373142 (accessed on 3 February 2022).

[18] OECD (2022), Guidebook on Best Practices in Public Health, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/4f4913dd-en.

[2] OECD (2021), Health at a Glance, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/19991312.

[5] OECD (2021), OECD Health Statistics: health expenditure and financing.

[21] OECD (2019), Individuals using the Internet for seeking health information - last 3 m (%) (all individuals aged 16-74), Dataset: ICT Access and Usage by Households and Individuals.

[17] OECD (2019), The Heavy Burden of Obesity: The Economics of Prevention, OECD Health Policy Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/67450d67-en.

[6] Oliveira Hashiguchi, T. (2020), “Bringing health care to the patient: An overview of the use of telemedicine in OECD countries”, OECD Health Working Papers, No. 116, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/8e56ede7-en.

[12] Pavlušová, M. et al. (2018), “Chronic heart failure - Impact of the condition on patients and the healthcare system in the Czech Republic: A retrospective cost-of-illness analysis”, Cor et Vasa, Vol. 60/3, pp. e224-e233, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crvasa.2018.03.002.

[8] Pekmezaris, R. et al. (2018), “Home Telemonitoring In Heart Failure: A Systematic Review And Meta-Analysis”, Health Affairs, Vol. 37/12, pp. 1983-1989, https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05087.

[4] Soundarraj, D. et al. (2017), “Containing the Cost of Heart Failure Management”, Heart Failure Clinics, Vol. 13/1, pp. 21-28, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hfc.2016.07.002.

[3] Táborský, M. et al. (2021), “Trends in the treatment and survival of heart failure patients: a nationwide population‐based study in the Czech Republic”, ESC Heart Failure, Vol. 8/5, pp. 3800-3808, https://doi.org/10.1002/ehf2.13559.

[20] WHO (2019), Existence of operational policy/strategy/action plan to reduce unhealthy diet related to NCDs (Noncommunicable diseases), https://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.imr.NCD_CCS_DietPlan?lang=en.

[25] WHO (2015), Atlas of eHealth country profiles: The use of eHealth in support of universal health coverage, Global Observatory for eHealth, https://www.afro.who.int/publications/atlas-ehealth-country-profiles-use-ehealth-support-universal-health-coverage.

[23] World Bank (2017), GNI per capita, PPP (constant 2017 international $).

[9] Wu, W. (ed.) (2015), “Comparative Effectiveness of Different Forms of Telemedicine for Individuals with Heart Failure (HF): A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis”, PLOS ONE, Vol. 10/2, p. e0118681, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0118681.

[10] Yun, J. et al. (2018), “Comparative Effectiveness of Telemonitoring Versus Usual Care for Heart Failure: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis”, Journal of Cardiac Failure, Vol. 24/1, pp. 19-28, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cardfail.2017.09.006.

Notes

← 1. New York Heart Association classification III (marked limitation in activity due to symptoms, even during less-than-ordinary activity such as walking short distances) or IV (severe heart limitations – experience symptoms even when resting).

← 2. Improve treatment quality, improve patient outcomes and reduce costs (see “Intervention description”).

← 3. The proportion of these patients who have advanced HF is not known.