This chapter covers Technology Enabled Care (TEC) programme in Scotland, which aims to mainstream digital health and care initiatives. The case study includes an assessment of TEC against the five best practice criteria, policy options to enhance performance and an assessment of its transferability to other OECD and EU27 countries.

Integrating Care to Prevent and Manage Chronic Diseases

11. Technology Enabled Care, Scotland

Abstract

Technology-Enabled Care (TEC), Scotland: Case study overview

Description: the objective of the Technology Enabled Care (TEC) programme in Scotland is to ensure that successful digital health and care initiatives are mainstreamed. To reach this goal, the TEC programme works at two levels. At the national level it provides leadership, evidence and guidance on mainstreaming TEC to the government, healthcare providers and other stakeholders. It also invests in national infrastructure, such as national licenses for digital care tools. At a local level, it helps to grow TEC initiatives by providing dedicated funding, as well as change management support and knowledge exchange, to organisations implementing or trialling such initiatives. If initiatives are successful and fit with health and social care priorities, there is an opportunity for the TEC programme to support the national scale up.

Best practice assessment:

OECD Best Practice assessment of TEC, Scotland

|

Criteria |

Assessment |

|---|---|

|

Effectiveness |

|

|

Efficiency |

|

|

Equity |

|

|

Evidence‑base |

|

|

Extent of coverage |

|

Enhancement options: A programme‑wide evaluation study would make the case for continued investment in the programme, allow comparative analysis between the different work streams and inform the selection of new activities or interventions, to ensure they align with the programme and reflect the best use of resources. Any countries implementing a TEC programme need to ensure that it increases rather than reduces digital inclusion.

Transferability: Many countries are well-placed to implement a TEC programme, as they have a national eHealth policy or strategy, and rely mostly on public funding for eHealth. Importantly, each country should shape their TEC programme to respond to local needs, priorities and barriers around technology-enabled care.

Conclusion: The TEC programme in Scotland is a multifaceted, national programme to support the development, implementation, scale‑up and evaluation of technology-enabled care. It does this by supporting and funding the design, implementation and scale‑up of specific technology-enabled care interventions, but also by addressing factors that affect uptake, such as digital inclusion, training, infrastructure and developing an evidence‑base.

Intervention description

Launched in late 2014, the objective of the Technology Enabled Care (TEC) programme in Scotland is to ensure that successful digital health and care initiatives are mainstreamed. Rather than developing or implementing initiatives itself, the TEC programme aims to create the right conditions for digitally enabled service transformation to take place across health and care services.

To reach this goal, the TEC programme works at two levels. At the national level it provides leadership, evidence and guidance on mainstreaming digital health and care to the government, healthcare providers, NHS boards1 and other stakeholders. It also invests in national infrastructure, such as national licenses for digital care tools. At a local level, it helps to grow technology-enabled care activities and initiatives by providing dedicated funding, as well as change management support and knowledge exchange, to organisations implementing or trialling such initiatives. If initiatives are successful and fit with health and social care priorities, there is an opportunity for the TEC programme to support the national scale up.

The TEC programme works in partnership with other organisations, including the NHS Boards, national care agencies, national Third Sector organisations (such as voluntary and community organisations), national and local care and housing providers, innovation centres, academia and industry.

The programme has four strategic priorities (TEC, 2021[]):

Addressing inequalities and promoting inclusion: the TEC programme works to increase the access to and uptake of digital in key populations, such as

Care home residents

Social care users

People who use drugs with multiple and complex needs

Innovating for transformation

Redesigning Services: the TEC programme works to scale up digital care technologies and roll them out across all of Scotland as sustainable Business As Usual (BAU) models of service delivery, including:

Video consultations (Attend Anywhere/Near Me)

Remote health pathways

Telecare

Digital mental healthcare

Engaging with citizens and staff/services through co-design and participation: the TEC programme supports workforce development by providing content, including the evidence base, around technology-enabled care, and engages with partners at international, national and local level and across health, social care, housing, public, independent and third sectors. It also works to increase citizen engagement in the development and implementation of technology-enabled care.

OECD Best Practices Framework assessment

This section analyses TEC against the five criteria within OECD’s Best Practice Identification Framework – Effectiveness, Efficiency, Equity, Evidence‑base and Extent of coverage (see Box 11.1 for a high-level assessment of TEC). Further details on the OECD Framework can be found in Annex A.

Box 11.1. Assessment of TEC, Scotland

Effectiveness

The TEC programme has been effective in scaling-up a number of initiatives across Scotland.

Evaluation studies of TEC-funded and supported interventions provide evidence of various positive outcomes, including enhanced dignity, independence and quality of life for clients, increased health and well-being of carers, and a reduction in unplanned hospital admissions.

Efficiency

In general, technology-enabled interventions were found to have a positive return on investment.

At the current level of provision for people aged 75 and over (20% of them receiving telecare), telecare has a return-on-investment of 153%: telecare costs GBP 39 million (EUR 46 million) per year but yields GBP 99 million (EUR 116 million) in economic benefits, primarily cost-savings due to prevention and delay of care home or hospital admissions.

Evidence‑base

There is no single study to evaluate TEC as a whole – instead, programmes are evaluated at the individual level.

Home and mobile health monitoring and telecare have the strongest evidence base.

Equity

Addressing inequalities and digital exclusion is one of the key objectives of the TEC programme.

There are programmes that focus on increasing digital inclusion among residents in care homes, people at risk of drug-related harm, and other vulnerable people who were not already online during the COVID‑19 pandemic.

Extent of coverage

It is difficult to determine the coverage of the programme as it entails many different interventions.

At a high-level, it is estimated that between TEC’s inception in 2014 and 2019, approximately 100 000 citizens have benefited from TEC.

Effectiveness

The primary objective of the TEC programme is to identify new approaches in technology-enabled care and support them in becoming “business as usual” and being adopted at scale. Example initiatives where this has been achieved include (TEC, 2019[]):

Computerised cognitive behavioural therapy (cCBT): the TEC programme supported and funded the scale up of cCBT across Scotland. This is now a business-as-usual service within local mental health services in all NHS Boards.

Workforce development: TEC funded a resource to develop and implement online learning tools for the workforce, including “Introduction to TEC” and “TEC in practice”, which is now being transitioned to NHS Education for Scotland.

CARED: The CARED service provides parents and carers of young people with eating disorders with information and support. It was funded by TEC and is now being adopted as a mainstream service within NHS Lothian and available as a resource across Scotland through the Mental Health Strategy.

Attend Anywhere / Near Me: The web-based video consultations platform is now in place in all NHS Boards for patient/service user consultations (see Box 11.2).

Box 11.2. The effectiveness of the TEC programme in scaling up the Attend Anywhere platform for video consultations

Attend Anywhere, branded as Near Me by many organisations in Scotland, is a web-based platform providing video call access to healthcare services. Patients can use the service through a computer or mobile device with internet, camera and microphone. An internet link takes patients to a “virtual” online waiting area, where service providers meet them and provide a consultation over video. It can be used by both health and social care organisations, and by both primary care and secondary care. Currently, most activity (>90%) is hospital-based.

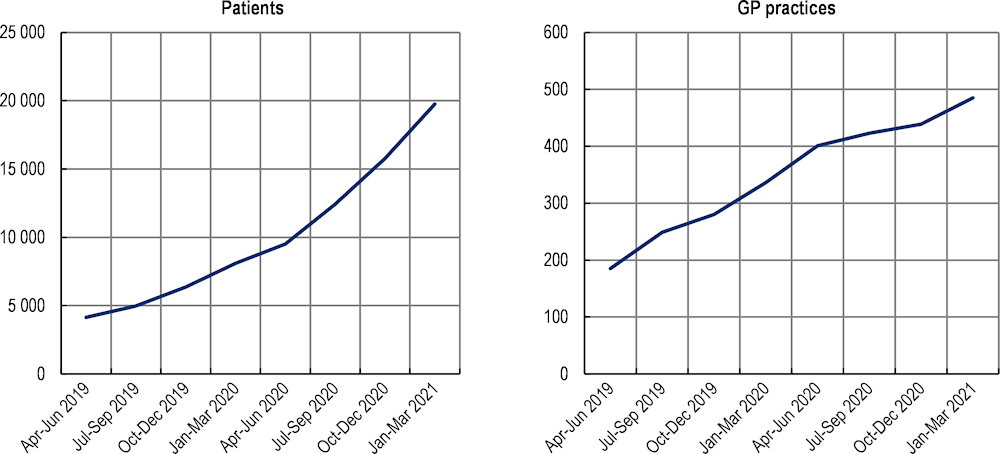

Attend Anywhere was developed by Health Direct Australia, a government funded organisation system, and it was procured for Scotland in 2016. Attend Anywhere clinics have now been established in all NHS Board as well as a range of Health and Social Care Partnerships and third sector organisations. To date, the platform is being used by nearly 500 GP practices for more than 20 000 appointments per week across 50 specialities in Scotland (TEC, 2021[]) (see Figure 11.1).

Figure 11.1. Uptake of the Attend Anywhere platform in Scotland

Source: TEC, 2021

Evaluation studies of TEC-funded and supported technology-enabled care interventions provide evidence of a range of different outcomes. Studies looking at telecare interventions reported enhanced dignity, independence and quality of life for clients, increased confidence of vulnerable clients to be more active, increased health and well-being of carers, a reduction in unplanned hospital admissions, and prevention or delay of admission to care homes. Evaluation studies of video conferencing programmes found better pharmaceutical management, improved access to specialist services, reduced hospital admissions and length of stay, cost and time savings for staff and clients, and a greater confidence in care for patients, their family and staff (Scottish Government, 2018[]).

Efficiency

Funding for technology-enabled care solutions makes up the bulk of the cost of the TEC programme: in 2020/21, GBP 11.0 million (EUR 12.86 million) was invested (TEC, 2021[]). The benefits that are returned depend on the intervention that was funded. In a progress report on the Attend Anywhere platform, NHS Boards reported savings on both staff and patient travel due to the use of video consultations of GBP 25 000 to GBP 130 000 per year across Scotland (EUR 29 200 – 152 000) (TEC, 2019[]). However, there is no one review comparing the investments of the TEC programme to the benefits of the various technology-enabled care interventions.

The TEC programme has commissioned several evaluation and economic analyses to understand the potential long-term health and economic benefits of different technology-enabled care interventions. Reviewing ten studies that provided economic data, all were found to have a positive return on investment (Scottish Government, 2018[]). One specific study looked at the economic benefits of universal telecare services in Scotland (Deloitte, 2017[]). It is estimated that at the current level of provision for people aged 75 and over (20% of them receiving telecare), telecare has a return-on-investment of 153% – i.e. telecare costs GBP 39 million (EUR 46 million) per year but yields GBP 99 million (EUR 116 million) in economic benefits, primarily cost-savings due to prevention and delay of care home or hospital admissions.

Equity

Technology-enabled care, such as video consultation or remote monitoring, can help address inequalities by reducing barriers to access, including time, distance and limited availability of services. However, there is a risk of digital exclusion. Given that those who experience health inequalities are also more likely to be digitally excluded (e.g. older people, disabled people, people in remote locations and on low incomes), there is a risk that technology-enabled care will exacerbate inequalities (Scottish Government, 2018[]).

In its 2021/22 strategic plan, the TEC programme pinpointed addressing inequalities and digital exclusion as one of its key objectives (TEC, 2021[]). In particular, the programme will focus on increasing digital inclusion among residents in care homes and people at risk of drug-related harm.

To bring technology-enabled care to care home residents, TEC will offer support and funding to ensure care homes have reliable internet connections, devices and other infrastructure needed for digital care. It will also support the development and adoption of a suite of tools that can be used in care homes, such as telecare, video-consultations, messaging and assessments tools. Finally, there will be initiatives to increase the digital skills of both staff and residents. This includes the testing, development and roll out of information and education for residents, based on the Connecting Scotland programme. To educate staff, TEC will work with the Scottish Social Services Council (SSSC) to adapt and apply digital learning tools (TEC, 2020[]).

Two interconnected programmes will be run to prevent drug deaths and addresses digital exclusion among people who use drugs with multiple and complex needs. Overdose detection and responder alert technologies (ODART) will be used to transform preventative care. A package of devices, connectivity and training support will be provided to organisations to build digital inclusion for people who use drugs with multiple and complex needs, as well as and those who support them (TEC, 2021[]).

To support other vulnerable people who were not already online during the COVID‑19 pandemic, the Connecting Scotland programme was created. This GBP 5 million (EUR 5.85 million) programme provided internet connection, training and support, and a laptop or tablet to 9 000 people who were considered at clinically high risk themselves. This allowed them to access services and support, as well as connect with friends during the pandemic.

Evidence‑base

There is no single study to evaluate TEC as a whole – instead, programmes are evaluated at the individual level. For this reason, evaluating the quality of evidence used to assess TEC using the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies from the Effective Public Health Practice Project is not appropriate. Instead, this section summarises the process TEC has in place to evaluate individual interventions funded through the programme.

As already shown in the effectiveness and efficiency sections, a key component of the TEC programme is measurement and evaluation to demonstrate the effectiveness of technologies that sit within individual work streams. This includes one‑off evaluations, improvement reports, ongoing monitoring, and forecast reports to assess the impact of scaling up, particularly on cost-effectiveness.

The individual evaluation studies were summarised in a report called “Technology Enabled Care: Data Review and Evaluation Options Study”, published by the Scottish Government (Scottish Government, 2018[]), which synthesised the evidence and identified gaps in the evidence, to inform future evaluations. This report looked at the evidence for different digital solutions, and found that:

For telecare, the evidence supporting short-term outcomes (e.g. increased confidence staying at home, fewer falls, increased independence and choice) was of high-to-medium quality, as was the evidence supporting medium-term outcomes (e.g. remaining at home longer, fewer admissions), and long-term outcomes (e.g. improved quality of life and well-being, for both service users and carers).

For home and mobile health monitoring (HMHM), the evidence of the short-term impacts (e.g. improved adherence to treatment, improved self-management) was judged to be of medium quality, while that of the medium-term (e.g. improved condition control, more timely appointments) and long-term impacts (e.g. improved viability of remote and rural communities, improved person-centred effective healthcare) was medium-to-low quality.

For video conferencing, the evidence of the short-term impacts (e.g. improved access to specialist services, reduced travel for staff) and the medium-term impact (e.g. shorted waiting times for appointments, improved efficiency) was judged to be of high-to-medium quality, while the evidence of long-term impacts (e.g. improved viability of remote and rural communities, improved person-centred effective healthcare) was of medium quality.

As discussed in the section on efficiency, some studies also looked at the economic benefits of technology-enabled care. The areas of the TEC programme which have seen the greatest levels of funding and are furthest along with implementation – HMHM and telecare – have the strongest evidence base around economic return. For interventions based on video conferencing and digital platforms the focus has been on developing, testing and deploying technology and infrastructure, and the evaluation studies are smaller in scale (Scottish Government, 2018[]).

The evidence base also evaluates the implementation of new programmes. One such study was conducted by Oxford University to evaluate the implementation and scale‑up of the Attend Anywhere platform (Scottish Government, 2020[]). It follows the NASSS theoretical model, looking at Non-adoption, Abandonment and challenges to spread, Scale‑up and Sustainability. In addition to identifying organisational and wider contextual factors that have aided the scale‑up of the programme, the report provides ten recommendations to support continued scale‑up, spread and sustainability of the Attend Anywhere platform.

Extent of coverage

As the TEC programme consists of a wide range of different interventions, it is difficult to determine the coverage. Nevertheless, at a high-level, it is estimated that between TEC’s inception in 2014 and 2019, approximately 100 000 citizens have benefited from TEC (TEC, 2019[]), which equates to around 2% of the Scottish population.

During the COVID‑19 pandemic, the TEC programme rapidly scaled up and expanded some of its existing programmes (TEC, 2021[]). For example, the Attend Anywhere teleconsultation platform saw its uptake increase from 300 appointments a week in March 2020 to over 22 000 a week in early 2021. Digital mental health services were also scaled up, including the rapid expansion of computerised cognitive behaviour therapy (cCBT) and deployment of Internet Enabled CBT services across all territorial Health Boards. Now, one in four referrals for psychological services are for digital consultations (TEC, 2021[]).

In addition to digital care platforms, TEC also invests in the underlying infrastructure needed for people to make use of digital care solutions. The Digital Approaches for Care Homes programme, run by TEC, helps care homes become “digitally enabled”, by providing devices, internet connections, and training for staff and residents. So far, a total of 1 857 iPads have been provided to 996 care homes, reaching about 10% of the resident population.

Policy options to enhance performance

The TEC programme is not a technology-enabled care intervention in and off itself, but rather a national, multifaceted programme to support the development, implementation, scale‑up and evaluation of such interventions. In this section, recommendations are given for TEC administrators as well as policy makers in countries who are considering implementing a similar programme, rather than recommendations for individual technology-enabled care interventions.

Enhancing effectiveness, efficiency and evidence base

To ensure the programme has the desired impact and delivers value for money, evidence is needed on the (cost-) effectiveness of the different elements of the programme combined. While evaluation studies of the individual interventions are crucial to support their development and implementation, it is also necessary to look at the national programme as a whole.

A programme‑wide evaluation study would have a number of benefits:

It would help with funding and political support for the programme, and make the case for continued investment in the programme.

It would allow comparative analysis between the different work streams. Currently, the TEC programme encompasses a wide variety of activities and interventions, and it is unclear whether resources could be reallocated to increase their impact. Especially when it comes to making decisions on scaling-up pilots, comparative analysis is needed.

A programme‑wide evaluation with a gap analysis could inform the selection of new activities or interventions, to ensure they align with the programme and reflect the best use of resources.

Enhancing equity

To ensure technology-enabled care solutions reach as many people as possible, TEC programmes need to invest in the underlying infrastructure and skills that enable people to make use of digital care interventions. Particular attention needs to be paid to population groups who are less experienced with technology or might not have access to it. For example, older adults are less likely to use the internet for health information, as are people with lower education (OECD, 2019[]), while economically disadvantaged groups may not have regular access to internet (Sieck et al., 2021[]). This digital divide risks exacerbating instead of reducing inequalities.

For this reason, TEC programmes need to ensure digital inclusion. The US-based National Digital Inclusion Alliance defines digital inclusion as “the activities necessary to ensure that all individuals and communities, including the most disadvantaged, have access to and use of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs)” (NDIA, n.d.[]). This includes:

Affordable and reliable broadband internet service;

Internet-enabled devices that meet the needs of the user;

Access to digital literacy training;

Quality technical support;

Applications and online content designed to enable and encourage self-sufficiency, participation and collaboration.

The Scottish TEC programme addresses points 1 and 2 by providing devices and investing in internet connections for vulnerable or digitally-disadvantaged groups. It also provides training for health and social care staff and for patients, to address point 3. Points 4 and 5 are specific to the various digital health intervention, and need to be considered during their development and implementation. As the TEC programme supports this process through funding, research and evaluation, it has the ability to also address these elements of digital inclusion. While these initiatives are an important first step, research is needed to confirm that they are having the desired effect.

Enhancing coverage

Increasing the coverage of technology-enabled care is one of the cornerstones of the TEC programme. The various activities under the TEC programme cover a wide range of healthcare services, sectors and users. They aim to scale up effective approaches and increase the uptake of existing solutions by the healthcare workforce and health service users. The number of users or providers reached is a key performance indicator used across various work streams.

However, it is important to keep in mind that high population coverage is not the ultimate aim. Regardless of training and educational efforts, there will always be people who prefer, or who will have better outcomes under, traditional care models (Lam et al., 2020[]). To safeguard equal and universal healthcare, TEC-like programmes should actively work to ensure that technology-enabled care always complements, rather than replace, face‑to-face delivery of health services (WHO, 2019[]).

Transferability

This section explores the transferability of the TEC programme from Scotland to other OECD and non-OECD EU countries and is broken into three components: 1) an examination of previous transfers; 2) a transferability assessment using publicly available data; and 3) additional considerations for policy makers interested in transferring TEC.

Previous transfers

International engagement is a core part of the TEC programme, to exchange good practices, and identify opportunities for research, innovation and new funding. For example, as part of a Digital Health Europe (DHE) funded Twinning project, the TEC programme shared good practices from Scotland with the University of Agder (Norway), Grimstad Kommune (Norway) and the Agency for Social Services and Dependency of Andalusia (Spain), and vice versa. Scotland also participates in the SCIROCCO Exchange project, which aims to support health and social care authorities in the adoption and scaling-up of integrated care.

Transferability assessment

The following section outlines the methodological framework to assess transferability and results from the assessment.

Methodological framework

Details on the methodological framework to assess transferability can be found in Annex A.

Indicators from publicly available datasets to assess the transferability of the TEC programme are listed in Table 11.1. Please note, the assessment is intentionally high level given the availability of public data covering OECD and non-OECD European countries.

Table 11.1. Indicators to assess transferability – TEC programme

|

Indicator |

Reasoning |

Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

|

Population context |

||

|

ICT Development Index* |

TEC is more transferable to countries with wide access to the internet |

🡹 value = more transferable |

|

Individuals using the Internet for seeking health information – last 3 m (%) (OECD data – 2019 or latest year) + Eurostat data (2017) |

TEC is more transferable to a population comfortable seeking health information online |

🡹 value = more transferable |

|

Sector context (digital health sector) |

||

|

eHealth composite index of adoption score amongst GPs in Europe** |

TEC is more transferable to countries where GPs are comfortable using eHealth technologies |

🡹 value = more transferable |

|

Proportion of tertiary institutions (public and private) that offer ICT for health (eHealth) courses |

TEC is more transferable if health professional students receive eHealth training |

🡹 value = more transferable |

|

Proportion of institutions or associations offering in-service training in the use of ICT for health as part of the continuing education of health professionals |

TEC is more transferable if health professionals have appropriate eHealth training |

🡹 value = more transferable |

|

Political context |

||

|

The national universal health coverage policy or strategy clearly refers to the use of ICT or eHealth to support universal health coverage |

TEC is more likely to be successful if the government sees ICT and eHealth as an integral part of healthcare delivery |

‘Yes’ = more transferable |

|

A national eHealth policy or strategy exists |

TEC is more likely to be successful if the government is supportive of eHealth |

‘Yes’ = more transferable |

|

A dedicated national telehealth policy or strategy exists |

TEC is more likely to be successful if the government is supportive of telehealth |

‘Yes’ = more transferable |

|

Economic context |

||

|

Special funding is allocated for the implementation of the national eHealth policy or strategy |

TEC is more likely to be successful if there already is allocated funding for eHealth |

‘Yes’ = more transferable |

|

Proportion of funding contribution for eHealth programmes provided by public funding sources over the previous two years |

A government-led TEC programme is more likely to be successful if eHealth programme funding mostly comes from public sources |

High proportion = more transferable |

Note: *The ICT development index represents a country’s information and communication technology capability. It is a composite indicator reflecting ICT readiness, intensity and impact (ITU, 2020[]). **The eHealth composite index of adoption amongst GPs is made up of adoption in regards to electronic health records, telehealth, personal health records and health information exchange (European Commission, 2018[]).

Source: ITU (2020[]), “The ICT Development Index (IDI): conceptual framework and methodology”, https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Pages/publications/mis/methodology.aspx; OECD (2019[]), “Individuals using the Internet for seeking health information – last 3 m (%) (all individuals aged 16‑74)”; WHO (2015[]), “Atlas of eHealth country profiles: The use of eHealth in support of universal health coverage”, https://www.afro.who.int/publications/atlas-ehealth-country-profiles-use-ehealth-support-universal-health-coverage; European Commission (2018[]), “Benchmarking Deployment of eHealth among General Practitioners (2018)”, https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/d1286ce7-5c05-11e9-9c52-01aa75ed71a1.

Results

The transfer analysis shows how the United Kingdom is well placed for a programme like the Scottish TEC programme: there is political drive to deliver eHealth, the population has a high level of digital inclusion, and there is public funding for eHealth (Table 11.2). Nevertheless, many other countries also have a national eHealth policy or strategy, and rely mostly on public funding for eHealth.

It is important to note though that data from publicly available datasets is not sufficient to assess the transferability of a multifaceted programme like the Scottish TEC programme. Countries interested in setting up a similar programme should do an analysis to identify what the needs and issues are around technology-enabled care, and how a national programme can address these. Each country will likely shape their TEC programme differently to respond to local needs, priorities and barriers.

Table 11.2. Transferability assessment by country (OECD and non-OECD European countries) – TEC programme

A darker shade indicates TEC may be more suitable for transferral in that particular country

|

|

The Inclusive Internet Index |

Individuals using the Internet for seeking health information – last 3 m (%) |

eHealth composite index of adoption score amongst GPs in Europe |

% tertiary institutions offering ICT for health courses |

% tertiary institutions offering in-service training for ICT for health professionals |

National universal health coverage policy refers to use of ICT or eHealth to support universal health coverage |

A national eHealth policy or strategy exists |

A dedicated national telehealth policy of strategy exists |

Special funding for implementation of national eHealth policy or strategy |

% funding contribution for eHealth provided by public sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

United Kingdom |

850.0 |

66.9 |

2.5 |

Medium |

High |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Very high |

|

Australia |

820 |

42.5 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

Yes |

n/a |

n/a |

Very high |

|

Austria |

750 |

53.2 |

2.1 |

Low |

Low |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

Very high |

|

Belgium |

770 |

48.7 |

2.1 |

Low |

Low |

No |

Yes |

Combined* |

Yes |

Very high |

|

Bulgaria |

640 |

34.0 |

1.8 |

Medium |

Medium |

Yes |

Yes |

Combined |

Yes |

Low |

|

Canada |

760 |

58.7 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

Yes |

n/a |

n/a |

Very high |

|

Chile |

610 |

27.5 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

Yes |

n/a |

n/a |

Very high |

|

Colombia |

500 |

41.5 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Costa Rica |

600 |

44.0 |

n/a |

Medium |

Medium |

n/a |

Yes |

Yes |

n/a |

Very high |

|

Croatia |

680 |

53.0 |

2.2 |

Low |

Medium |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Very high |

|

Cyprus |

630 |

58.0 |

1.9 |

Medium |

Low |

n/a |

Yes |

Combined |

No |

Very high |

|

Czech Republic |

720 |

56.5 |

2.1 |

Medium |

n/a |

Yes |

No |

Combined |

No |

Low |

|

Denmark |

880 |

67.4 |

2.7 |

Medium |

Very high |

n/a |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Very high |

|

Estonia |

800 |

59.5 |

2.4 |

Medium |

Low |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Very high |

|

Finland |

810 |

76.3 |

2.6 |

Medium |

Medium |

No |

Yes |

Combined |

Yes |

Very high |

|

France |

800 |

49.6 |

2.1 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Germany |

810 |

66.5 |

1.9 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Greece |

690 |

49.9 |

1.8 |

Medium |

Medium |

n/a |

Yes |

Combined |

Yes |

Very high |

|

Hungary |

660 |

60.5 |

2.0 |

Low |

n/a |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

Very high |

|

Iceland |

870 |

64.7 |

n/a |

Very high |

Very high |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Very high |

|

Ireland |

770 |

56.9 |

2.1 |

n/a |

Low |

n/a |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Low |

|

Israel |

730 |

50.0 |

n/a |

High |

Low |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Very high |

|

Italy |

690 |

35.0 |

2.2 |

Low |

High |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Very high |

|

Japan |

830 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

Yes |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Korea |

880 |

50.4 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Latvia |

690 |

47.9 |

1.8 |

Low |

Low |

Yes |

Yes |

Combined |

Yes |

Low |

|

Lithuania |

700 |

60.6 |

1.6 |

Medium |

Low |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

High |

|

Luxembourg |

830 |

58.2 |

1.8 |

Low |

Low |

n/a |

Yes |

Combined |

Yes |

Very high |

|

Malta |

750 |

59.0 |

n/a |

Very high |

Very high |

Yes |

No |

No |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Mexico |

450 |

49.8 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

No |

n/a |

High |

|

|

Netherlands |

840 |

74.0 |

n/a |

High |

High |

Yes |

Yes |

Combined |

Yes |

Very high |

|

New Zealand |

810 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

Yes |

n/a |

n/a |

Low |

|

Norway |

840 |

69.0 |

n/a |

Low |

Medium |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Very high |

|

Poland |

660 |

47.4 |

1.8 |

High |

Medium |

Yes |

Yes |

Combined |

Yes |

Very high |

|

Portugal |

660 |

49.4 |

2.1 |

Low |

Low |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

High |

|

Romania |

590 |

33.0 |

1.8 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

Yes |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Slovak Republic |

670 |

52.6 |

1.8 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Slovenia |

710 |

48.1 |

2.0 |

High |

High |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

Very high |

|

Spain |

750 |

60.1 |

2.4 |

Low |

Medium |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

Very high |

|

Sweden |

850 |

62.2 |

2.5 |

Very high |

Very high |

n/a |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Very high |

|

Switzerland |

850 |

66.9 |

n/a |

Low |

Very high |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Low |

|

Türkiye |

550 |

51.3 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

Yes |

No |

Combined |

Yes |

Low |

|

United States |

810 |

38.3 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

Yes |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

Note: Blank cells indicate data is missing. *Combined with eHealth strategy of policy.

Source: See Table 11.1.

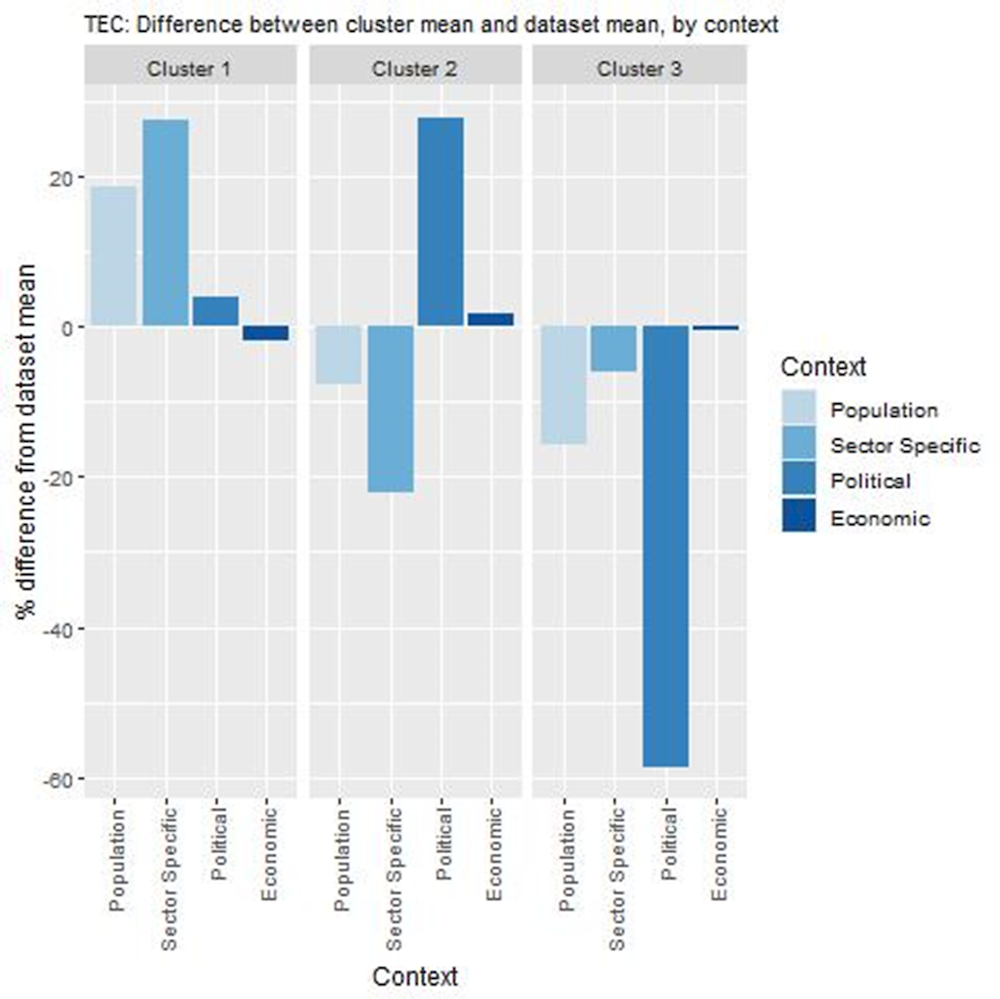

To help consolidate findings from the transferability assessment above, countries have been clustered into one of three groups, based on indicators reported in Table 11.1. Countries in clusters with more positive values have the greatest transfer potential. For further details on the methodological approach used, please refer to Annex A.

Key findings from each of the clusters are below with further details in Figure 11.2 and Table 11.3:

Countries in cluster one have population, sector specific and political arrangements in place to transfer TEC, and are therefore good transfer candidates. Scotland, which is within the United Kingdom and also the owner of this intervention, falls under this cluster.

Countries in cluster two have political priorities that align with TEC interventions, for example, the existence of a national eHealth strategy. Nevertheless, before transferring this interventions, countries in this cluster should undertake further analysis to determine whether the population and digital health sector are ready. For example, determining whether the health workforce have the appropriate skills to deliver widespread digital care.

Countries in cluster three should undertake further analysis to ensure TEC aligns with political priorities, and similar to countries in cluster two, ensure the population and a digital health sector are ready.

Figure 11.2. Transferability assessment using clustering – TEC programme

Note: Bar charts show percentage difference between cluster mean and dataset mean, for each indicator.

Source: See Table 11.1.

Table 11.3. Countries by cluster – TEC programme

|

Cluster 1 |

Cluster 2 |

Cluster 3 |

|---|---|---|

|

Australia Canada Chile Denmark Estonia Iceland Ireland Lithuania New Zealand Sweden Switzerland United Kingdom United States |

Belgium Bulgaria Costa Rica Croatia Cyprus Czech Republic Finland Greece Italy Latvia Luxembourg Netherlands Norway Poland Türkiye |

Austria Hungary Israel Malta Mexico Portugal Slovenia Spain |

Note: Due to high levels of missing data, the following countries were omitted from the analysis: Colombia, France, Germany, Japan, Korea, Romania, and the Slovak Republic.

New indicators to assess transferability

Data from publicly available datasets is not sufficient to assess the transferability of TEC. For example, there is no easily comparable information available on the current TEC landscape in different countries. Box 11.3 outlines information policy makers should consider before transferring TEC.

Box 11.3. New indicators, or factors, to consider when assessing transferability – TEC programme

In addition to the indicators within the transferability assessment, policy makers are encouraged to collect the following information:

Population context

How acceptable are mHealth interventions amongst the public?

Do patients have the skills to access healthcare online? What are the gaps in skills that the programme should address?

Does the population trust their personal health information will be used, stored and managed appropriately?

Sector-specific context (digital health)

What is the TEC landscape currently?

What are the gaps in TEC that the programme should address?

Are healthcare providers supportive of using digital products?

What regulations are in place and how do they affect TEC interventions?

Political context

Has TEC received political support from key decision-makers?

Has TEC received commitment from key decision-makers?

Economic context

Where should funding for the TEC programme come from?

Conclusion and next steps

The TEC programme in Scotland is a multifaceted, national programme to support the development, implementation, scale‑up and evaluation of technology-enabled care. It does this by supporting and funding the design, implementation and scale‑up of specific technology-enabled care interventions, but also by addressing factors that affect uptake, such as digital inclusion, training, infrastructure and developing an evidence‑base.

To ensure the effectiveness and efficiency of TEC-like programmes, a programme‑wide evaluation following a logic model could be useful. This would help make the case for continued investment in the programme and help prioritise investments between the different work streams. It is also strongly recommended that any TEC programmes consider and address digital inclusion, to prevent creating a digital divide that worsens health inequalities.

The United Kingdom is well placed for a programme like the Scottish TEC programme, as there is political drive to deliver eHealth and a high level of digital inclusion. However, countries should design their TEC programme to fit with their needs. It is therefore important for transfer countries to conduct a local analysis of needs, priorities and barriers around technology-enabled care to inform the design of their TEC programme.

Box 11.4 outlines next steps for policy makers and funding agencies in relation to TEC.

Box 11.4. Next steps for policy makers and funding agencies – TEC programme

Next steps for policy makers and funding agencies are listed below:

Ensure that TEC programmes address digital inclusion, to reduce rather than exacerbate health inequalities

Evaluate the TEC programme as a whole, to make the case for investment in the programme and help prioritise investments between the different work streams

Design TEC programmes to address the local needs, priorities and barriers to technology-enabled care

References

[6] Deloitte (2017), Telecare Feasibility Study.

[16] European Commission (2018), Benchmarking Deployment of eHealth among General Practitioners (2018), https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/d1286ce7-5c05-11e9-9c52-01aa75ed71a1.

[15] ITU (2020), The ICT Development Index (IDI): conceptual framework and methodology, https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Pages/publications/mis/methodology.aspx (accessed on 26 February 2021).

[13] Lam, K. et al. (2020), “Assessing Telemedicine Unreadiness Among Older Adults in the United States During the COVID-19 Pandemic”, JAMA Internal Medicine, Vol. 180/10, p. 1389, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.2671.

[12] NDIA (n.d.), Definitions, https://www.digitalinclusion.org/definitions/# (accessed on 20 July 2021).

[10] OECD (2019), Health in the 21st Century: Putting Data to Work for Stronger Health Systems, OECD Health Policy Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/e3b23f8e-en.

[17] OECD (2019), Individuals using the Internet for seeking health information - last 3 m (%) (all individuals aged 16-74), Dataset: ICT Access and Usage by Households and Individuals.

[8] Scottish Government (2020), Attend Anywhere / Near Me video consulting service evaluation 2019-2020: report, https://www.gov.scot/publications/evaluation-attend-anywhere-near-video-consulting-service-scotland-2019-20-main-report/ (accessed on 27 May 2021).

[4] Scottish Government (2018), Technology Enabled Care: data review and evaluation options study, Scottish Government, Edinburgh, https://www.gov.scot/publications/technology-enabled-care-programme-data-review-evaluation-options-study/ (accessed on 18 May 2021).

[11] Sieck, C. et al. (2021), “Digital inclusion as a social determinant of health”, npj Digital Medicine 2021 4:1, Vol. 4/1, pp. 1-3, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-021-00413-8.

[1] TEC (2021), Digital Citizen Delivery Plan 2021/2022, https://tec.scot/downloadable-resources/2/ (accessed on 20 May 2021).

[3] TEC (2021), TEC at a glance 2020/21.

[7] TEC (2020), Connecting People Connecting Services: Digital Approaches in Care Homes Action Plan, https://tec.scot/sites/default/files/2021-06/Digital-Approches-in-Care-Homes-Action-Plan-Final.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2021).

[5] TEC (2019), Attend Anywhere Progress Report.

[2] TEC (2019), Supporting Service Transformation - Delivery Plan 2019/20, https://tec.scot/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/TEC-Delivery-plan-2019.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2021).

[9] TEC (2019), TEC at a glance 2019, https://tec.scot/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/TEC-At-a-Glance-2019.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2021).

[14] WHO (2019), Recommendations on digital interventions for health system strengthening.

[18] WHO (2015), Atlas of eHealth country profiles: The use of eHealth in support of universal health coverage, Global Observatory for eHealth, https://www.afro.who.int/publications/atlas-ehealth-country-profiles-use-ehealth-support-universal-health-coverage.

Note

← 1. NHS Scotland consists of 14 regional NHS Boards, who are responsible for the protection and the improvement of their population’s health and for the delivery of frontline healthcare service.