This chapter covers ParkinsonNet in the Netherlands, a programme to deliver high-quality, specialist care for patients with Parkinson’s disease. The case study includes an assessment of ParkinsonNet against the five best practice criteria, policy options to enhance performance and an assessment of its transferability to other OECD and EU27 countries.

Integrating Care to Prevent and Manage Chronic Diseases

13. ParkinsonNet, the Netherlands

Abstract

ParkinsonNet, the Netherlands: Case study overview

Description: ParkinsonNet was developed in 2004 at Radboud University Medical Centre in the Netherlands to deliver high quality, specialist care for Parkinson’s disease. Through regional networks, allied health interventions are delivered by specifically trained therapists who work according to evidence‑based guidelines. These specialised therapists become highly experienced, as they manage a high caseload of patients with Parkinson’s disease. There are over 70 regional ParkinsonNet networks, covering the entire country, bringing together over 3 500 specialists healthcare professionals.

Best practice assessment:

OECD Best Practice assessment of ParkinsonNet, the Netherlands

|

Criteria |

Assessment |

|---|---|

|

Effectiveness |

|

|

Efficiency |

|

|

Equity |

|

|

Evidence‑base |

|

|

Extent of coverage |

|

Enhancement options: In places where low population density does not support a specialisation model, telehealth options can be explored. To ensure equity, data on uptake and outcomes across different population groups is needed – for example from a registry.

Transferability: ParkinsonNet has already been transferred to a number of other countries and regions highlighting its transferability potential. Countries with a lower population density and fewer physiotherapists should explore whether and how a specialisation model can be implemented. While a single‑payer health system makes it easier to capitalise on the cost-savings of the network, other systems could also work.

Conclusion: ParkinsonNet delivers high quality, specialist care for Parkinson’s disease, improving outcomes and reducing cost.

Intervention description

Parkinson’s disease is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder mostly affecting people in later years of life (Sveinbjornsdottir, 2016[1]). It is the second most common neurodegenerative disease worldwide and affects roughly 1% of people over 60. Parkinson’s disease has a complex presentation, which includes motor symptoms (e.g. slowness of movements, muscular rigidity, tremors, postural instability, speech disturbances) and non-motor symptoms (e.g. apathy, sleep problem, memory complaints, loss of smell and taste, mood disturbances, excessive sweating, fatigue and pain).

There is no available treatment that will halt or stop progression of the disease (Sveinbjornsdottir, 2016[1]). Treatment with dopaminergic drugs aims to correct the motor disturbances. Surgical therapy using deep brain electrical stimulation can sometimes be used when drug therapy fails to control the motor symptoms.

However, medical management is only partially effective in controlling the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. Allied health treatments, such as physiotherapy, occupational therapy and speech therapy, can help people with Parkinson’s disease in their daily activities and participation in society (Radder et al., 2017[2]). Nevertheless, among allied health professionals there often is a lack of expertise and experience in treating patients with Parkinson’s disease (Ypinga et al., 2018[3]).

ParkinsonNet was developed in 2004 at Radboud University Medical Centre in the Netherlands to deliver high quality, specialist care for Parkinson’s disease. Through regional networks, allied health interventions are delivered by specifically trained therapists who work according to evidence‑based guidelines. These specialised therapists become highly experienced as they manage a high caseload of patients with Parkinson’s disease (Ypinga et al., 2018[3]).

There are over 70 regional ParkinsonNet networks covering the whole of the Netherlands. They bring together over 3 500 specialists healthcare professionals, including neurologists, physical therapists, occupational therapists, speech-language therapists, Parkinson’s nurses, dietitians and social workers. A regional co‑ordination (generally a physiotherapist) manages each network, which comes together three times a year for continuing education. The regional co‑ordinators meet yearly at a national level, to exchange knowledge and experiences.

In addition to organising national meetings, a central ParkinsonNet team supports the regional networks by providing consultancy services on how to set up and maintain a disease‑specific care network, various forms of education on Parkinson’s disease and its treatment, and a one‑year “Train the Trainer” curriculum. These trainers also benefit from a yearly skills lab, bringing together experts from around the world to exchange ideas and knowledge on Parkinson’s disease.

The ParkinsonNet programme has also developed evidence‑based guidelines for Parkinson’s disease, including in the fields of nutrition, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, speech and language therapy, and for self-management of the disease.

OECD Best Practices Framework assessment

This section analyses ParkinsonNet against the five criteria within OECD’s Best Practice Identification Framework – Effectiveness, Efficiency, Equity, Evidence‑base and Extent of coverage (see Box 13.1 for a high-level assessment of ParkinsonNet). Further details on the OECD Framework can be found in Annex A.

Box 13.1. Assessment of ParkinsonNet, the Netherlands

Effectiveness

Various studies have looked at the effectiveness of ParkinsonNet, and have found that it lowers the rate of hip fractures by 50%, reduces the number of Parkinson’s disease‑related hospital admissions from 21% to 17%, and increases the continuity of care

The impacts outlined above were achieved with a lower number of treatment sessions per year – 33.7 compared to 48.0.

Efficiency

The start-up cost of the network are estimated at EUR 3 million over five years, with ongoing cost of roughly EUR 25 per patient, per year.

This compares favourably to the cost-savings resulting from the programme, which are estimated at EUR 500 to EUR 1 400 per patient per year.

These savings are the result of fewer treatment session needed, lower overall Parkinson’s disease‑related healthcare cost, lower informal care cost and less cost for day-hospital rehabilitation.

Equity

Claims data analysis suggests that the demographic differences between people receiving specialised therapy through ParkinsonNet and those receiving usual care are small.

However, this analysis is based on relatively old data, and the programme has significantly expanded since.

Evidence‑base

Throughout its existence, ParkinsonNet has been evaluated in a number of studies.

A retrospective study based on claims data was judged as providing “strong” evidence of its effectiveness.

Extent of coverage

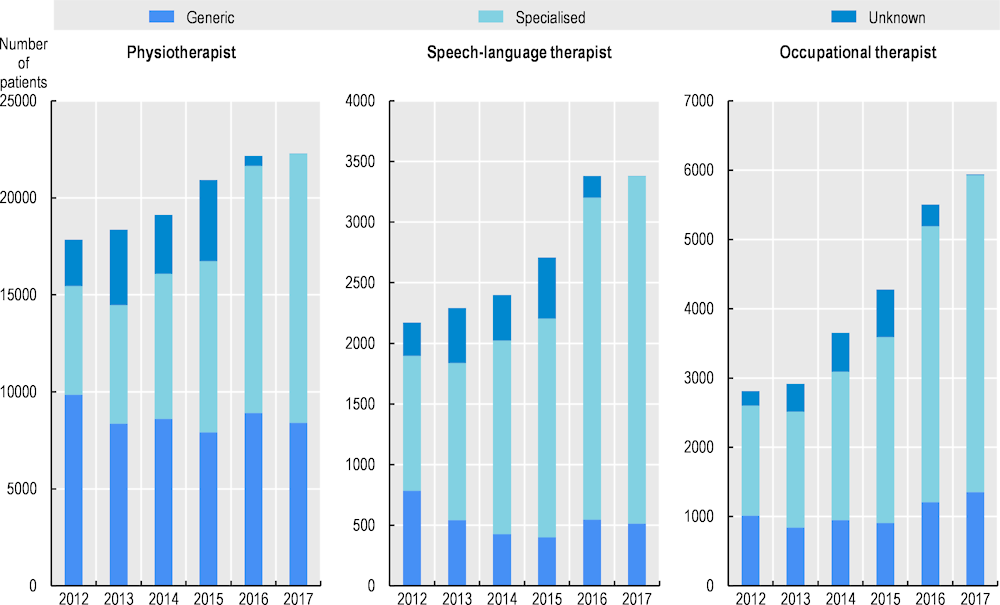

The proportion of people with Parkinson’s receiving specialised physiotherapy, speech therapy and occupational therapy increased by 147%, 157% and 187% between 2012 and 2017.

In 2017, most regions in the Netherlands saw more than 60% of people with Parkinson’s disease receiving specialised speech-language and occupational therapy.

Effectiveness

There are a number of studies evaluating the effectiveness of ParkinsonNet, which look at health outcomes, continuity of care, and daily functioning. Results from prominent studies are summarised below.

One analysis of claims data showed a 50% reduction in the rate of hip fractures as a result of ParkinsonNet treatment (Bloem et al., 2017[4]). Another retrospective analysis of claims data found that people who were treated by a specialised physiotherapist had significantly fewer Parkinson’s disease‑related hospital admissions than those who received care from a general physiotherapist: 17% of people versus 21%. This was despite receiving fewer treatment sessions – 33.7 compared to 48.0 per year (Ypinga et al., 2018[3]).

This same study also showed how ParkinsonNet improved the continuity of care: people who received specialised care saw the same therapist for 93% of visits, compared to 81% for people receiving usual care (Ypinga et al., 2018[3]).

A randomised controlled trial (RCT) compared people receiving ParkinsonNet’s specialised occupational therapy to people receiving no occupational therapy, and found that it led to an improvement in self-perceived performance in daily activities in patients with Parkinson’s disease, as measured using the evidence‑based Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (Sturkenboom et al., 2014[5]).

Efficiency

The start-up cost of building ParkinsonNet nationwide are estimated at nearly EUR 3 million over five years (see Table 13.1) (Bloem et al., 2017[4]). After this initial start-up period, the annual cost are estimated at around EUR 1 million per year. For the Netherlands, where around 3 000 trained professionals collectively serve a total potential volume of 40 000 Parkinson patients, these ongoing annual cost equate to roughly EUR 25 per patient per year.

Table 13.1. Cost of ParkinsonNet

Start-up costs for the first 5 years of building ParkinsonNet nationwide in the Netherlands; and maintenance costs per year for maintaining ParkinsonNet

|

Start-up cost (first 5 years) |

Maintenance cost (per year) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Category |

Explanation |

USD |

EUR |

Explanation |

USD |

EUR |

|

Personnel |

The ParkinsonNet start up team for building a sustainable network should consist of at least: Project lead, ParkinsonNet ambassador, IT lead, expert speech therapist, expert physical therapist, expect occupational therapist, care co‑ordinator, support. Total: 2.2 FTE (full-time equivalent) annually, at USD 75 000 per year over 5 years |

950 000 |

807 500 |

The ParkinsonNet co‑ordination centre consists of at least the following personnel: Project lead (1 800 hours/year), ParkinsonNet ambassador (350 hr/y), IT lead (350 hr/y), expert speech therapist (700 hr/y), expert physical therapist (700 hr/y), expect occupational therapist (700 hr/y), care co‑ordinator (700 hr/y), support (200 hr/y). |

265 000 |

225 250 |

|

Building evidence‑based practice guidelines |

(External) expert personnel, consensus meetings, literature review, writing process (USD 75k per guideline) |

777 000 |

660 450 |

(External) expert personnel, consensus meetings, literature review, writing process (USD 75k per guideline, two guidelines per year) |

173 000 |

147 050 |

|

Training and education |

Cost for venues and other expenses involved in training and education of providers who join the ParkinsonNet network |

576 000 |

489 600 |

Cost for venues and other expenses involved in training and education of providers who join the ParkinsonNet network, plus continuing education of trained providers |

273 000 |

232 050 |

|

Promotion |

Patient and provider education and promotion activities, approximately USD 30 000 in the start-up phase |

173 000 |

147 050 |

Patient and provider education and promotion activities |

52 000 |

44 200 |

|

Regional support |

Active guidance and delivery of tools to facilitate collaboration and communication |

58 000 |

49 300 |

Active guidance and delivery of tools to facilitate collaboration and communication |

86 000 |

73 100 |

|

Selection and qualification (quality control) |

Audit cost and cost to study the quality of care provided. During start up, there are cost to set quality standards |

115 000 |

97 750 |

Audit cost and cost to study the quality of care provided |

58 000 |

49 300 |

|

IT cost |

ParkinsonNet uses various IT systems. A basic network uses at least the following IT platforms: Member management system, healthcare finder, online community platform, content management platform, patient registry/measurement of quality of care |

346 000 |

294 100 |

ParkinsonNet uses various IT systems. A basic network uses at least the following IT platforms: Member management system, healthcare finder, online community platform, content management platform, patient registry. There cost are higher after the start-up phase as all systems are in place and being used |

173 000 |

147 050 |

|

Office cost |

Costs for housing and hosting the co‑ordination team (inc. computers and other overhead) |

461 000 |

391 850 |

Costs for housing and hosting the co‑ordination team (inc. computers and other overhead) |

115 000 |

97 750 |

|

Total |

|

3 456 000 |

2 937 600 |

|

1 195 000 |

1 015 750 |

Note: Exchange rate used : 1 USD = 0.85 EUR.

Source: Bloem et al. (2017[4]), “ParkinsonNet: A Low-Cost Health Care Innovation With A Systems Approach From The Netherlands”, https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0832.

ParkinsonNet has been associated with cost savings, as it results in (Bloem et al., 2017[4]):1

Greater efficiency of care, as ParkinsonNet patients require fewer treatment sessions;

Reductions in disease complications (specifically, fewer inpatient admissions); and

Improved patient self-management, reducing dependence on medical services.

The retrospective analysis of claims data found that people who were treated by a specialised physiotherapist had significantly fewer Parkinson’s disease‑related complications than those who received care from a general physiotherapist, despite receiving fewer treatment sessions (33.7 compared to 48.0 per year) (Ypinga et al., 2018[3]). As a result, people receiving physiotherapy from specialised therapists had lower direct cost related to physiotherapy (EUR 933 per year versus EUR 1 329), as well as lower overall Parkinson’s related healthcare cost (EUR 2056 versus EUR 2 586).

An earlier cluster randomised trial found that total costs over 24 weeks were EUR 727 lower in ParkinsonNet clusters compared with usual-care clusters (roughly EUR 1 400 per year) (Munneke et al., 2010[6]). This was driven mostly by lower informal care cost (EUR 313) and day-hospital rehabilitation (EUR 123).

Comparing these savings of between EUR 500 and EUR 1 400 per patient per year to ParkinsonNet’s ongoing running cost of EUR 25 per patient per year suggests that this is a cost-saving, efficient intervention.

Equity

An analysis of claims data from a large Dutch health insurer (CZ Groep, which has a market share of 21%) selected all patients with a diagnosis for Parkinson’s disease, and who had received treatment by any physiotherapist (specialised or usual care) for Parkinson’s disease during at least one of the three observation years (2013‑15) (Ypinga et al., 2018[3]). This sample could be representative of the wider population, as around 23% of the overall Dutch population with Parkinson’s disease was covered by CZ Groep (similar to their market share), and neither CZ Groep nor any other Dutch health insurer applied selective contracting during the study period.

Analysis of this sample shows some demographic differences in patients receiving specialised physiotherapy versus usual care physiotherapy (Table 13.2). Patients receiving specialised physiotherapy were slightly younger, more likely to be male, of a lower socio‑economic status, less likely to be depressed and on fewer drugs for Parkinson’s disease. However, differences were small and likely not clinically meaningful.

Table 13.2. Comparison of people receiving specialised vs usual care physiotherapy

|

Specialised physiotherapy (n=2129) |

Usual care physiotherapy (n=2252) |

Difference (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Age |

72.76 |

73.61 |

0.58 (0.30 to 1.39) |

|

Women |

41% |

44% |

3.63% (0.67 to 6.53) |

|

Socio‑economic status (scale ‑5.5 (low SES) to 3 (high SES)) |

0.14 |

0.22 |

0.08 (0.01 to 0.14) |

|

Depression |

18% |

21% |

3.2% (0.84 to 5.50) |

|

Number of different Parkinson’s disease drugs |

1.67 |

1.80 |

0.13 (0.08 to 0.19) |

Note: Based on data on 4 381 patients insured by CZ Group, who had been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease and who received physiotherapy between 2013 and 2015.

Source: Ypinga et al. (2018[3]), “Effectiveness and costs of specialised physiotherapy given via ParkinsonNet: a retrospective analysis of medical claims data”, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30406-4.

Evidence‑base

Several studies evaluating ParksinonNet are available. For the purpose of this case study, the study undertaken by Ypinga et al. (2018[3]) has been used to assess the quality of the evidence‑base. This study was chosen because it is recent, it recorded statistically significant results; and it looks at both effectiveness and efficiency. While there is also an RCT looking at ParkinsonNet – generally considered the gold standard in study design – this study compared people receiving ParkinsonNet’s specialised occupational therapy to people receiving no occupational therapy at all (Sturkenboom et al., 2014[5]). Therefore, the effect it measures will be partially due to having any occupational therapy, rather than specialised occupational therapy.

The Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies rates this study as “strong” in many areas (see Table 13.3) (Effective Public Health Pratice Project, 1998[7]). While it was not a blinded RCT, the researchers adjusted for all confounders and used a large, representative real-life population.

Table 13.3. Evidence‑based assessment

|

Assessment category |

Question |

Rating |

|---|---|---|

|

Selection bias |

Are the individuals selected to participate in the study likely to be representative of the target population? |

Very likely |

|

What percentage of selected individuals agreed to participate? |

80%‑100% agreement |

|

|

Selection bias score: Strong |

||

|

Study design |

Indicate the study design |

Cohort analytic |

|

Was the study described as randomised? |

No |

|

|

Study design score: Fair |

||

|

Confounders |

Were there important differences between groups prior to the intervention? |

No |

|

If yes, indicate the percentage of relevant confounders that were controlled (either in the design (e.g. stratification, matching) or analysis)? |

80 – 100% (most) |

|

|

Confounders score: Strong |

||

|

Blinding |

Was the outcome assessor aware of the intervention or exposure status of participants? |

Not applicable |

|

Were the study participants aware of the research question? |

Not applicable |

|

|

Blinding score: Not applicable |

||

|

Data collection methods |

Were data collection tools shown to be valid? |

Yes |

|

Were data collection tools shown to be reliable? |

Yes |

|

|

Data collection methods score: Strong |

||

|

Withdrawals and dropouts |

Were withdrawals and dropouts reported in terms of numbers and/or reasons per group? |

Yes |

|

Indicate the percentage of participants who completed the study? |

80 ‑100% |

|

|

Withdrawals and dropouts score: Strong |

||

Source: Effective Public Health Practice Project (1998[7]), “Quality assessment tool for quantitative studies”, https://www.nccmt.ca/knowledge-repositories/search/14.

Extent of coverage

Analysis of claims data shows that between 2012 and 2017, the percentage of people with Parkinson’s disease who receive specialists physiotherapy, occupational therapy or speech therapy, defined as therapy delivered by therapists participating in ParkinsonNet, has increased considerably (see Figure 13.1) (Bloem et al., 2021[8]). For both physiotherapy and speech-language therapy, the overall increase in patients receiving therapy was driven solely by an increase in specialised therapy. For occupational therapy, there was a small increase in the number of people receiving generic therapy, but the increase in specialised occupational therapy far outweighed this. The number of people with Parkinson’s receiving specialised physiotherapy, speech therapy and occupational therapy increased by 147%, 157% and 187%, respectively, over the five years studied.

Figure 13.1. Trend in specialised allied health therapy for people with Parkinson’s disease

Number of patients with a therapist

Source: Bloem et al. (2021[8]), “From trials to clinical practice: Temporal trends in the coverage of specialized allied health services for Parkinson’s disease”, https://doi.org/10.1111/ENE.14627.

Across the country, the proportion of people receiving specialised therapy has increased (Bloem et al., 2021[8]). In 2017, most regions saw more than 60% of people receiving specialised speech-language and occupational therapy. The coverage of physiotherapy is lower, but relatively uniformly distributed over the country.

Policy options to enhance performance

In this section, recommendations are given for ParkinsonNet administrators, as well as policy makers in other countries who are considering implementing a similar programme, as to how the performance of the programme could be further enhanced.

Enhancing effectiveness and efficiency

In the Netherlands, which is relatively densely populated, it has generally been possible to increase the number of Parkinson’s patients one specialists sees while keeping the average travel time limited. However, this may not be possible in more sparsely populated areas. In this case, the possibilities for using telehealth could be explored to ensure patients still receive specialised care (Bloem et al., 2020[9]). Telehealth can also help increase efficiency by reducing travel time for staff or patients, for example. Previous studies support the use of telehealth to treat patients with Parkinson’s disease (e.g. (Chen et al., 2018[10])).

For some parts of the care team and process (e.g. neurologist consultations, personal care managers, peer-to-peer consultations between specialists), this may be more straightforward than for physiotherapy, which is generally more hands-on. To deliver physiotherapy using telehealth solutions, the following considerations should be taken into account (Cottrell and Russell, 2020[11]):

Triage: patient factors such as age, co-morbidities, mobility or balance deficits, language barriers and visual, hearing, or cognitive impairments may determine the eligible for telehealth. For complex patients, a hybrid approach where an in-person assessment is performed initially and subsequent management provided via telehealth may be more successful. Other factors such as the availability of a private space in the patient’s residence and internet connection also play an important part.

Platform selection: it is recommended to choose a single videoconferencing platform or software, to limit the amount of training needed for staff and patients. This platform needs to be carefully selected to meet the needs of the service. For example, for physiotherapy a platform offering a wide field of vision may be required. Moreover, some software solutions offer measurement tools (e.g. goniometry) that may be of use. It should also be easy to use for patients with Parkinson’s, who may exhibit symptoms such as tremors or speech disturbances, which can complicate the use of teleconferencing software.

Physical environment: the physical environment also needs to be considered to ensure the success of physiotherapy teleconsultations. This includes, for example, ensuring a large enough space free from clutter, where the required equipment is available (e.g. chair, bed, weights). To improve the video and audio quality, it may be necessary to use a headset, eliminate background noise, improve lighting and choose a neutral background.

Ethical and professional considerations: it is important to consider ethical and professional concerns around telehealth for physiotherapy, such as the scope of services that can be delivered remotely, and whether professional indemnity insurance policies explicitly cover the provision of healthcare via telehealth. Patients may need to provide specific consent, or require information on telehealth. As with in-person care, privacy and confidentiality need to assured.

Enhancing equity and evidence base

While the analysis of claims data from 2013‑15 did not show major differences in patients in and outside the programme, the programme has since expanded significantly, and the picture may be different now. Moreover, the regional approach of the programme means that there may be local differences in process and outcomes.

A register of participants could provide the data needed for an in-depth analysis of the differences in outcomes across population groups. Contrary to claims data, the register can be designed specifically for the research question, and provide better insights on severity of the disease, treatments received, and demographic factors, as well as collect medical, health, well-being and satisfaction outcomes (Box 13.2). Claims data could be used to create an artificial control group.

Box 13.2. Potential metrics to collect

Below is a list of suggested measures that could be included in the register of patients accessing ParkinsonNet. These are meant as a starting point for discussion, and are not exhaustive. Given the sensitivity of some of these data, any register must be adequately secure to ensure both patients and providers feel comfortable using the platform.

Demographics and personal characteristics: age, gender, income, educational level, location, living situation, age of diagnosis, severity of disease, symptoms

Process: number of visits, type of therapy, missed appointments, guideline compliance, knowledge of disease

Medical outcomes: admissions to hospital, number of Parkinson’s drugs and treatments, falls and other injuries, medication errors, mortality

Well-being: depression and mental health, life satisfaction, independent living, activities of daily living

Satisfaction: patient-reported outcomes, patient-reported experience with care, satisfaction with care providers.

Transferability

This section explores the transferability of the ParkinsonNet programme from the Netherlands to other OECD and non-OECD EU countries and is broken into three components: 1) an examination of previous transfers; 2) a transferability assessment using publicly available data; and 3) additional considerations for policy makers interested in transferring ParkinsonNet.

Previous transfers

ParkinsonNet has been transferred to a number of other countries and regions, including California, Luxembourg, the Czech Republic and Norway. A transfer to the Niederrhein region in Germany was less successful, but resulted in valuable lessons learned (see Box 13.3).

Box 13.3. Key elements of a successful transfer

ParkinsonNet was transferred to the Niederrhein region in Germany. The educational materials and software were translated into German, and a three‑day training was provided for physiotherapists. However, despite early enthusiasm, the intervention did not take off. Afterward, three key elements of success were identified that were missing in the German transfer.

A champion – generally someone renown in the field of Parkinson’s disease, who drives and promotes the programme

A super trouper – someone within the network who receives continued training and can educate the trainers

A business case – there needs to be some mechanism to capitalise on healthcare savings made by the programme to cover the ongoing cost of the network.

Relative to other integrated care models, in particular, macro-level models that change affect multiple levels of care, ParkinsonNet is transferable given it does not require major infrastructure changes or new technologies. However, to ensure ParkinsonNet achieves the same outcomes in a different setting, it must be adapted to suit the needs of the population, health professionals and other stakeholders affected. Further, it is necessary to keep the programme’s core features, in particular ensuring health professional are highly trained in delivering care to patients with Parkinson’s disease.

Transferability assessment

The following section outlines the methodological framework to assess transferability and results from the assessment.

Methodological framework

Details on the methodological framework to assess transferability can be found in Annex A.

Indicators from publicly available datasets to assess the transferability of ParkinsonNet are listed in Table 13.4. Please note, the assessment is intentionally high level given the availability of public data covering OECD and non-OECD European countries.

Table 13.4. Indicators to assess transferability – ParkinsonNet

|

Indicator |

Reasoning |

Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

|

Population context |

||

|

Prevalence of Parkinson’s disease (%) |

ParkinsonNet is more transferable to countries with a high prevalence of Parkinson’s disease, allowing a higher case load |

🡹 value = more transferable |

|

Population density (people per sq. km of land area) |

ParkinsonNet is more transferable to countries with a high population density, allowing a higher case load while limiting travel time |

🡹 value = more transferable |

|

Sector context (Parkinson’s disease care) |

||

|

Number of physiotherapists per 1 000 population |

ParkinsonNet is more transferable to countries with a high number of allied health professionals, allowing specialisation |

🡹 value = more transferable |

|

Economic context |

||

|

Single‑payer health system |

ParkinsonNet is more transferable to countries with a single payer, to capitalise on healthcare savings generated by the network |

‘Yes’ = more transferable |

Source: OECD (2021[12]), “OECD Health Statistics 2021”, https://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/health-data.htm; World Bank (2020[13]), “Population density (people per sq. km of land area)”, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EN.POP.DNST; Dorsey et al. (2018[14]), “Global, regional, and national burden of Parkinson’s disease, 1990‑2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016”, https://doi.org/10.1016/s1474-4422(18)30295-3; OECD (2016[15]), “Health Systems Characteristics Survey”, https://qdd.oecd.org/subject.aspx?Subject=hsc.

Results

ParkinsonNet in the Netherlands benefits from a high number of physiotherapists and a high population density (Table 13.5). Moreover, there is a relatively high prevalence of Parkinson’s disease. All of these factors support the model of specialised care with a large Parkinson’s disease caseload for specialists. Many other countries have significantly lower population densities and fewer physiotherapists – which should be considered before implementing ParkinsonNet.

While a single‑payer health system allows the payer to capitalise on the savings generated by the network through greater efficiency of care and fewer disease complications, in some cases other financial models may work as well. In the Netherlands, ParkinsonNet managed to establish agreements with the major insurers in the country. In California, ParkinsonNet is part of Kaiser Permanente, an integrated managed care consortium.

Table 13.5. Transferability assessment by country (OECD and non-OECD European countries) – ParkinsonNet

|

Country |

Prevalence of Parkinson’s disease |

Population density (people per sq. km of land area) |

Physiotherapists per 1 000 |

Single‑payer system |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Netherlands |

0.20% |

518.0 |

1.9 |

Multiple insurance funds or companies |

|

Australia |

0.17% |

3.3 |

1.07 |

A national health system covering the country as a whole |

|

Austria |

0.18% |

108.1 |

0.45 |

Multiple insurance funds or companies |

|

Belgium |

0.18% |

381.6 |

2.04 |

Multiple insurance funds or companies |

|

Bulgaria |

0.24% |

63.8 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Canada |

0.29% |

4.2 |

0.65 |

A national health system covering the country as a whole |

|

Chile |

0.14% |

25.7 |

1.73 |

Multiple insurance funds or companies |

|

Colombia |

0.05% |

45.9 |

0.67 |

Multiple insurance funds or companies |

|

Costa Rica |

0.07% |

99.8 |

n/a |

A single health insurance fund (single‑payer model) |

|

Croatia |

0.23% |

71.5 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Cyprus |

0.11% |

130.7 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Czech Republic |

0.21% |

138.6 |

0.87 |

Multiple insurance funds or companies |

|

Denmark |

0.16% |

145.8 |

1.72 |

A national health system covering the country as a whole |

|

Estonia |

0.23% |

30.6 |

0.41 |

A single health insurance fund (single‑payer model) |

|

Finland |

0.19% |

18.2 |

2.07 |

A national health system covering the country as a whole |

|

France |

0.18% |

123.1 |

1.3 |

A single health insurance fund (single‑payer model) |

|

Germany |

0.20% |

238.3 |

2.33 |

Multiple insurance funds or companies |

|

Greece |

0.21% |

83.1 |

0.83 |

A single health insurance fund (single‑payer model) |

|

Hungary |

0.21% |

106.8 |

0.57 |

n/a |

|

Iceland |

0.14% |

3.6 |

1.79 |

A national health system covering the country as a whole |

|

Ireland |

0.13% |

72.5 |

1.03 |

A national health system covering the country as a whole |

|

Israel |

0.11% |

425.9 |

0.77 |

Multiple insurance funds or companies |

|

Italy |

0.24% |

200.0 |

1.1 |

A national health system covering the country as a whole |

|

Japan |

0.20% |

345.2 |

n/a |

Multiple insurance funds or companies |

|

Korea |

0.11% |

531.0 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Latvia |

0.24% |

30.6 |

0.45 |

A national health system covering the country as a whole |

|

Lithuania |

0.24% |

44.6 |

1.34 |

A single health insurance fund (single‑payer model) |

|

Luxembourg |

0.15% |

260.2 |

2.01 |

A single health insurance fund (single‑payer model) |

|

Malta |

0.16% |

1641.5 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Mexico |

0.06% |

66.3 |

n/a |

Multiple insurance funds or companies |

|

New Zealand |

0.13% |

19.3 |

1.15 |

n/a |

|

Norway |

0.14% |

14.7 |

2.51 |

A national health system covering the country as a whole |

|

Poland |

0.20% |

124.0 |

0.7 |

A single health insurance fund (single‑payer model) |

|

Portugal |

0.18% |

112.5 |

0.14 |

A national health system covering the country as a whole |

|

Romania |

0.21% |

83.8 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Slovak Republic |

0.18% |

113.5 |

0.37 |

n/a |

|

Slovenia |

0.23% |

104.3 |

0.72 |

A single health insurance fund (single‑payer model) |

|

Spain |

0.20% |

94.8 |

1.21 |

A national health system covering the country as a whole |

|

Sweden |

0.20% |

25.4 |

1.35 |

Local health systems that serve distinct geographic regions |

|

Switzerland |

0.18% |

218.6 |

n/a |

Multiple insurance funds or companies |

|

Türkiye |

0.08% |

109.6 |

0.07 |

A single health insurance fund (single‑payer model) |

|

United Kingdom |

0.18% |

277.8 |

0.47 |

A national health system covering the country as a whole |

|

United States |

0.22% |

36.0 |

0.71 |

n/a |

Note: n/a indicates data is missing.

Source: See Table 13.4.

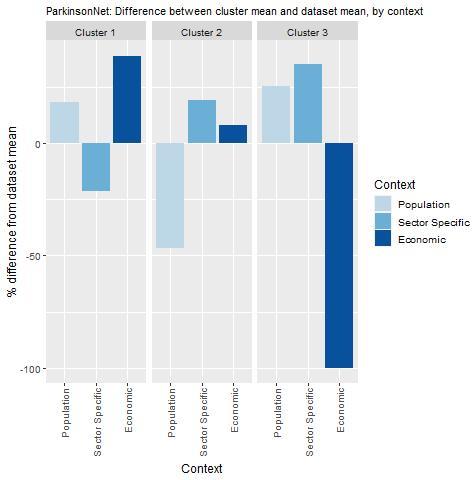

To help consolidate findings from the transferability assessment above, countries have been clustered into one of three groups, based on indicators reported in Table 13.4. Countries in clusters with more positive values have the greatest transfer potential. For further details on the methodological approach used, please refer to Annex A.

Key findings from each of the clusters are below with further details in Figure 13.2 and Table 13.6:

Countries in cluster one have population and economic factors that are beneficial for the transfer of ParkinsonsNet. On average, these countries have a high population density, a high prevalence of Parkinson’s disease, and a single‑payer health system. However, a relatively low density of physiotherapists may mean that it is not possible for them to specialise fully.

Countries in cluster two have a relatively high number of physiotherapists, as well as favourable payment systems. However, before transferring these countries should explore whether the population density and care demand allows for specialisation of care.

Countries in cluster three score high on both the population and sector factors, but generally do not have a single‑payer health system. This means that other ways of capitalising on the econonomic benefit of ParkinsonNet need to be found. The Netherlands, which is the owner of this intervention, falls under this cluster.

Figure 13.2. Transferability assessment using clustering – ParkinsonNet

Note: Bar charts show percentage difference between cluster mean and dataset mean, for each indicator.

Source: See Table 13.4.

Table 13.6. Countries by cluster – ParkinsonNet

|

Cluster 1 |

Cluster 2 |

Cluster 3 |

|---|---|---|

|

Australia Bulgaria Canada Croatia Czech Republic Estonia Finland France Greece Hungary Italy Latvia Lithuania Poland Portugal Romania Slovenia Spain Sweden United Kingdom United States |

Colombia Costa Rica Cyprus Denmark Iceland Ireland Israel Korea Luxembourg Mexico New Zealand Norway Türkiye |

Austria Belgium Chile Germany Japan Malta Netherlands Slovak Republic Switzerland |

New indicators to assess transferability

Data from publicly available datasets is not ideal to assess the transferability of ParkinsonNet. For example, no internationally comparable data is available on the use of allied health services in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease, nor on the political landscape around the condition. Box 13.4 outlines information policy makers should consider before transferring ParkinsonNet.

Box 13.4. New indicators, or factors, to consider when assessing transferability – ParkinsonNet

In addition to the indicators within the transferability assessment, policy makers are encouraged to collect the following information:

Population context

What is the profile of patients with Parkinson’s disease?

What are the care needs of patients with Parkinson’s disease?

Sector specific context (Parkinson’s disease care)

How many people with Parkinson’s disease receive care from allied health professionals?

What type/mix of care do they receive?

What is the knowledge of allied health professionals on Parkinson’s disease currently?

What is the expected caseload of specialised health professionals?

Are there “champions” who can drive the establishment and continuation of the network?

Political context

Is Parkinson’s disease a priority for policy makers and funders?

Is centralised, integrated care a priority for policy makers and funders?

Economic context

How can ParkinsonNet be funded?

What is the cost of implementing and operating the intervention in the target setting and to whom?

Conclusion and next steps

ParkinsonNet delivers high quality, specialist care for Parkinson’s disease. Through regional networks, allied health interventions, such as physiotherapy, occupational therapy and speech therapy, are delivered by specifically trained therapists who work according to evidence‑based guidelines. These specialised therapists manage a high caseload of patients with Parkinson’s disease and thus become highly experienced.

Evidence shows that specialised care offered through ParkinsonNet lowers complications such as falls, fractures and hospitalisations. This, combined with a fewer treatment sessions needed, results in considerable cost-savings. The network has expanded quickly to reach national coverage: between 2012 and 2017 the proportion of people with Parkinson’s disease receiving specialised physiotherapy, speech therapy and occupational therapy increased by 147%, 157% and 187%, respectively.

While the Netherlands benefits from a high population density, making it possible to increase the number of Parkinson’s patients one specialists sees while keeping the average travel time limited, this might not be the case in other countries. The possibilities for using telehealth could be explored to ensure patients still receive specialised care. A register of participants could help understand who is receiving care, and the outcomes for different population groups.

Box 13.5 outlines next steps for policy makers and funding agencies regarding ParkinsonNet.

Box 13.5. Next steps for policy makers and funding agencies – ParkinsonNet

Next steps for policy makers and funding agencies are listed below:

Explore the opportunities for the use of telehealth, for example through a pilot study under the current ParkinsonNet programme.

Consider collecting more data on equity, potentially using a register of ParkinsonNet participants.

When implementing ParkinsonNet, identify a champion, a super trouper and a business case.

References

[8] Bloem, B. et al. (2021), “From trials to clinical practice: Temporal trends in the coverage of specialized allied health services for Parkinson’s disease”, European Journal of Neurology, Vol. 28/3, p. 775, https://doi.org/10.1111/ENE.14627.

[9] Bloem, B. et al. (2020), “Integrated and patient-centred management of Parkinson’s disease: a network model for reshaping chronic neurological care”, The Lancet Neurology, Vol. 19/7, pp. 623-634, https://doi.org/10.1016/s1474-4422(20)30064-8.

[4] Bloem, B. et al. (2017), “ParkinsonNet: A Low-Cost Health Care Innovation With A Systems Approach From The Netherlands”, Health Affairs, Vol. 36/11, pp. 1987-1996, https://doi.org/10.1377/HLTHAFF.2017.0832.

[10] Chen, Y. et al. (2018), “Application of telehealth intervention in Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis”, Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, Vol. 26/1-2, pp. 3-13, https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633x18792805.

[11] Cottrell, M. and T. Russell (2020), “Telehealth for musculoskeletal physiotherapy”, Musculoskeletal Science and Practice, Vol. 48, p. 102193, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msksp.2020.102193.

[14] Dorsey, E. et al. (2018), “Global, regional, and national burden of Parkinson’s disease, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016”, The Lancet Neurology, Vol. 17/11, pp. 939-953, https://doi.org/10.1016/s1474-4422(18)30295-3.

[7] Effective Public Health Pratice Project (1998), Quality assessment tool for quantitative studies, https://www.nccmt.ca/knowledge-repositories/search/14.

[6] Munneke, M. et al. (2010), “Efficacy of community-based physiotherapy networks for patients with Parkinson’s disease: a cluster-randomised trial”, The Lancet Neurology, Vol. 9/1, pp. 46-54, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70327-8.

[12] OECD (2021), OECD Health Statistics 2021, https://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/health-data.htm.

[15] OECD (2016), Health Systems Characteristics Survey 2016, https://qdd.oecd.org/subject.aspx?Subject=hsc.

[2] Radder, D. et al. (2017), “Physical therapy and occupational therapy in Parkinson’s disease”, https://doi.org/10.1080/00207454.2016.1275617, Vol. 127/10, pp. 930-943, https://doi.org/10.1080/00207454.2016.1275617.

[5] Sturkenboom, I. et al. (2014), “Efficacy of occupational therapy for patients with Parkinson’s disease: a randomised controlled trial”, The Lancet. Neurology, Vol. 13/6, pp. 557-566, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70055-9.

[1] Sveinbjornsdottir, S. (2016), “The clinical symptoms of Parkinson’s disease”, Journal of Neurochemistry, Vol. 139/Suppl 1, pp. 318-324, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/jnc.13691 (accessed on 30 August 2021).

[13] World Bank (2020), Population density (people per sq. km of land area), https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EN.POP.DNST (accessed on 16 December 2021).

[3] Ypinga, J. et al. (2018), “Effectiveness and costs of specialised physiotherapy given via ParkinsonNet: a retrospective analysis of medical claims data”, The Lancet Neurology, Vol. 17/2, pp. 153-161, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30406-4.

Note

← 1. Of the 10 studies evaluating cost savings, only two showed no significant changes in cost saving.