This chapter covers the Finnish City of Oulu’s Self Care Service (SCS), a patient-provider portal. The case study includes an assessment of SCS against the five best practice criteria, policy options to enhance performance and an assessment of its transferability to other OECD and EU27 countries.

Integrating Care to Prevent and Manage Chronic Diseases

5. Oulu’s Self Care Service, Finland

Abstract

Oulu’s Self Care Service: Case study overview

Description: In 2011, the City of Oulu, Finland, scaled-up its digital patient-provider portal – the Self Care Service (SCS) – to all residents. SCS offers patients a range of online primary care services such as online appointment booking, messaging with professionals and ePrescriptions. SCS is tethered to each individual’s electronic health record (EHR) to ensure health professionals have ready access to patient data. For health professionals, SCS provider guidelines and care pathways based on individual patient data. SCS is voluntary and free‑of-charge.

Best practice assessment:

OECD best practice assessment of Oulu’s Self Care Service

|

Criteria |

Assessment |

|---|---|

|

Effectiveness |

SCS has improved access to healthcare services with number of users increasing by 235% between 2012‑20. Evidence from the broader literature on patient portals revealed they improve medication adherence, and patient safety and empowerment, however, their impact on clinical outcomes is less clear. |

|

Efficiency |

SCS is estimated to have led to cost savings of EUR 5.12 million between years 2012 and 2016. Evidence supporting the hypothesis that patient portals reduce healthcare utilisation are currently limited. |

|

Equity |

SCS is designed to boost uptake among disadvantaged population groups – e.g. it is free of charge and has features that improve usability by people with a disability. Unless this aspect is specifically considered, digital health interventions can widen existing inequalities given the most in need groups are less likely to access such interventions. |

|

Evidence‑base |

The impact of patient portals is supported by findings from systematic and umbrella reviews, however, individual studies are often of low- to moderate‑quality. |

|

Extent of coverage |

Over one‑third (34%) of Oulu’s population actively use SCS, which is higher than the adoption rate of 23% estimated in a recent systematic review and meta‑analysis. |

Enhancement options: to enhance effectiveness, policy makers should continue efforts to boost population health literacy to ensure patients understand the information they receive and therefore appreciate the usefulness of SCS. To enhance equity, plans to expand the number of languages available on SCS should be prioritised given languages such as Dari and Somali are spoken by refuges who typically have worse health outcomes. To enhance the evidence‑base, researchers should capitalise on the high-quality data stored within Finland’s national EHR system by evaluating the impact of SCS on outcomes and healthcare utilisation. Several options to enhance the extent of coverage are available such as encouraging health professionals to promote SCS to patients.

Transferability: SCS has been transferred from Oulu to other Finnish municipalities. It has not been transferred to other countries, however, many OECD and EU countries allow patients to access their EHR via a patient portal (or have plans to). Results from the transferability assessment using publicly available data revealed SCS is most suited to other Nordic countries, which have digitally advanced healthcare systems.

Conclusion: SCS is a patient-provider portal offering residents of Oulu access to a wide‑range of primary care services online. SCS is a global leader in this area, however, further enhancements are possible, as outlined in this case study. A high-level transferability assessment revealed Nordic countries are most suited to SCS, nevertheless, there is political interest among a number of countries to improve patient access to their data.

Intervention description

In 2011, the City of Oulu, Finland, scaled-up its digital patient-provider portal – the Self Care Service (SCS) – to all residents. This section details SCS’s objectives, services, access and partnering organisation.

Objectives

SCS’s objectives are four‑fold and in general aim to address the challenges caused by an ageing population and rising rates of multimorbidity:

Improve access to healthcare services through digital means

Improve patient outcomes and safety by encouraging people to take care of their health, enhancing patient safety, and enabling the City of Oulu’s chronic care model

Empower people to take care of their own health thereby improving disease prevention and chronic disease management

Reduce pressure on healthcare services by a) allowing patients to handle tasks independently thereby freeing up primary care professional resources and b) improving access to primary care thereby reducing demand on secondary/tertiary services.

Services

SCS is a voluntary digital patient-provider portal focused on primary care and to a lesser extent social care. SCS has three interfaces: 1) a citizen interface; 2) a primary care professional interface (for general practitioners (GPs) and nurses); and 3) maintenance interface (Lupiañez-Villanueva, Sachinopoulou and Thebe, 2015[1]). SCS services offered as part of the citizen interface are detailed in Box 5.1.

With the patient’s consent, data collected through the citizen interface is linked to information within national EHRs, which are widely used across Finland. This ensures primary care professionals have ready access to all patient data. Patients can separately access their EHR via a national website (omakanta.fi).

Box 5.1. Oulu’s Self Care Service – citizen interface services

The citizen interface includes a general knowledge and personal health directory. SCS services broken down by Ammenwerth et al.’s (2019[2]) patient-provider portal taxonomy are summarised below:

Access

Access to primary care services

View personal health records such as laboratory and x-ray results, vaccinations, medications and diagnoses

In 2020, SCS expanded its services to allow users to book and receive results from a COVID‑19 test

Request

Book primary care appointments (e.g. for check-ups and laboratory and dental appointments)

ePrescriptions (renewals)

Communicate

Make contact with primary care and social service professionals for non-urgent queries given primary care professionals are available during office hours only

Share

Home monitoring, for example, blood pressure, blood glucose, asthma, weight, sleep and alcohol consumption (several measurement devices can be linked to SCS or manually uploaded)

Manage

Information on prevention such as well-being and treatment of illnesses (provided by Duodecim Medical Publications Ltd, a large medical publisher)

Education

Risk measurement and weight control support, for example, through nutrition diaries

Access to information on social claims and benefits (e.g. the types of benefits a person is eligible for)

The primary care professional interface connects professionals with patients. It provides professionals with tailored guidelines and care pathways based on individual patient information such as laboratory results. Further, primary care professionals can use the interface to contact social care when a patient has need of their services (Lupiañez-Villanueva, Sachinopoulou and Thebe, 2015[1]).

Partnering organisation

SCS is a public private partnership between the City of Oulu and CSAM, an eHealth company targeting Nordic countries. Specifically, SCS utilises CSAM S7 technology (for further details, see the following link: https://www.csamhealth.com/solutions/connected-healthcare/csam-s7/).

OECD Best Practice Framework assessment

This section analyses Oulu’s SCS against the five criteria within OECD’s Best Practice Identification Framework – Effectiveness, Efficiency, Equity, Evidence‑base and Extent of coverage (see Box 5.2 for a high-level assessment of SCS). Further details on the OECD Framework can be found in Annex A.

Box 5.2. Assessment of the City of Oulu’s Self Care Service

Effectiveness

Between 2012 and 2020, the number of SCS users increased by 235%. On average, each user logs into the service between 5 to 10 times

SCS has been a useful resource during the COVID‑19 pandemic, with over 60 000 test results uploaded to the platform

Systematic reviews on the impact of patient-provider portals show they positively affect behavioural outcomes (e.g. medication adherence) and empower patients. However, their impact on clinical outcomes is mixed.

Efficiency

SCS is estimated to have saved over EUR 5 million between 2012 and 2016.

In the broader literature, there is limited evidence to suggest patient portals reduce utilisation of healthcare services (e.g. hospitalisations).

Equity

SCS was designed to maximise coverage including among disadvantaged populations such as those with a low socio‑economic status – e.g. the service is free‑of-charge and has features making it easy to use for those with a disability

SCS is currently available in Finnish but there are plans to expand to other languages include Arabic, Dari and Somali, which are commonly spoken among refugees

Despite processes to ensure disadvantaged population groups have access to SCS, there is a risk that groups with the greatest need for the service have the lowest level of access

Evidence‑base

Utilisation of SCS services was measured using routine data collected from patients. The data is accurate and reliable given it is stored in a sophisticated electronic health information system.

The impact of patient portals on clinical outcomes, safety, empowerment and healthcare utilisation were drawn from several systematic and umbrella reviews including low, moderate and high quality studies.

Extent of coverage

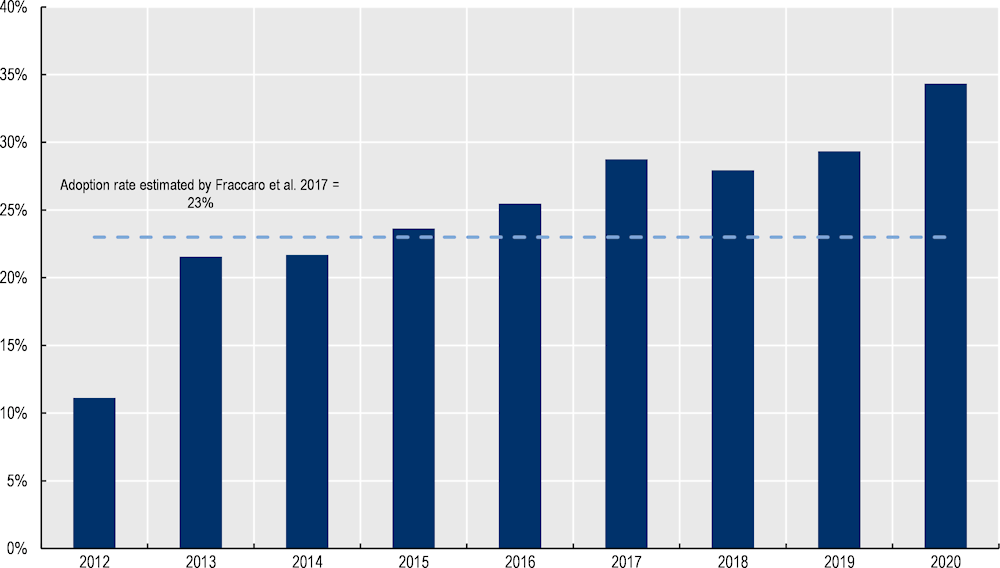

The proportion of Oulu citizens who logged into SCS grew from 11% to 34% between 2012 and 2020, which is higher than the mean patient portal adoption rate – 23% – estimated within a recent systematic review and meta‑analysis

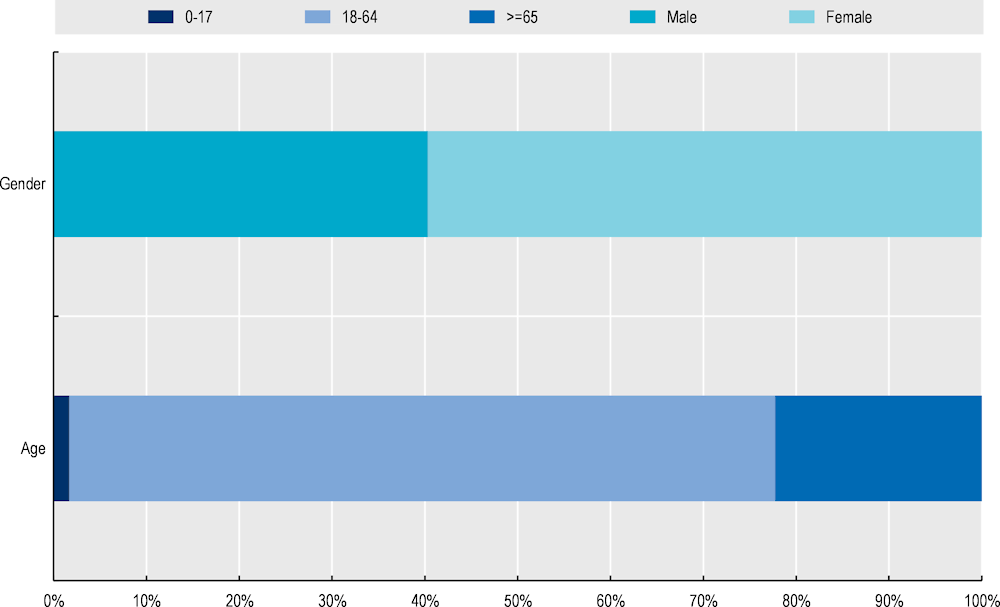

The majority of users are women (60%) and a significant proportion (22%) are aged 65+

The use of SCS amongst primary care professionals is also high given the country’s focus on building a digitally literate health workforce

Effectiveness

The objectives of Oulu’s SCS are to 1) improve access to healthcare, 2) improve patient outcomes and safety, 3) empower people and 4) reduce pressure on healthcare services. The remainder of this section explores SCS’s performance against the first three objectives, while objective 4 is explored under “Efficiency”.

The number of people accessing care through SCS has grown markedly, and has been a key resource during the COVID‑19 pandemic

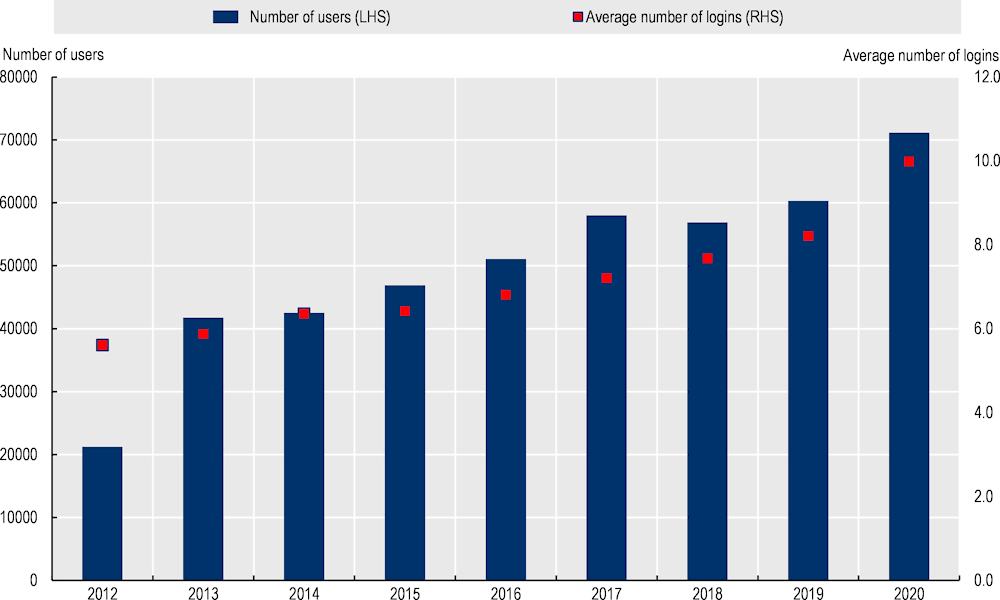

Between 2012 and 2020, the number of SCS users increased from 21 252 to 71 157 (a 235% increase) (Figure 5.1). (Details on the breakdown of SCS users – e.g. by gender and age – are explored under the criterion “Extent of Coverage”). The average number of logins per user also increased from 5.6 logins per year to 10 over the same period.

Figure 5.1. Number of SCS users and average number of logins, 2012‑20

Note: LHS = left hand side axis. RHS = right hand side axis.

Source: Data provided by Oulu Self Care Service administrators.

Other findings related to healthcare access from SCS patients are summarised below:

COVID‑19 tests: between August 2020 and March 2021, 61 843 COVID‑19 test results were uploaded onto SCS

Messages to health professionals: since 2012, health professionals have received over 400 000 messages through the portal. Patients who use the messaging feature, on average, send between 1‑3 messages per year.

ePrescriptions: over 18 000 prescriptions were renewed online between 2012 and 2016. In 2017, Kanta, the national digital service for health and social care, overtook responsibility for this service.

Patient-provider portals improve medication adherence and patient safety, however, their impact on health outcomes is less clear

Data from SCS and national EHRs can be linked, therefore, it is possible for future studies to assess what impact SCS has on health outcomes and health expenditure. Given this information is not readily available, the following paragraph summarises the literature on the impact patient-provider portals have on psychological, behavioural and clinical outcomes.

In 2019, Han et al. (2019[3]) published results from a systematic review on the impact of patient portals on psychological, behavioural and clinical outcomes. Findings from the review concluded patient portals have a significant, positive impact on medication adherence and access to preventative services (e.g. papsmear tests and cervical cancer screening). On patient safety, there is moderate quality evidence indicating portals improve safety by allowing patients to request correction of errors, in particular, medication errors (Antonio, Petrovskaya and Lau, 2020[4]). Conversely, the impact of patient portals on psychological outcomes (e.g. healthy eating) and clinical outcomes (e.g. blood pressure, glycemic, cholesterol and weight control) is mixed. Regarding clinical outcomes, findings from Han et al. (2019[3]) align with recent systematic and umbrella reviews which conclude there is insufficient or low-strength evidence to support the positive impact of patient portals on clinical outcomes (Ammenwerth et al., 2019[2]; Antonio, Petrovskaya and Lau, 2020[4]).

Patient portals empower patients to take control of their health

Patient portals play a key role in delivering patient-centred care as they allow users to engage in shared decision-making and encourage patient self-management. Information on patient empowerment and Oulu’s SCS is not available. In the broader literature, there is evidence supporting the hypothesis that patient portals “empower patients in shared decision making” and “encourage engagement in self-care and self-management” (Antonio, Petrovskaya and Lau, 2020[4]).

Efficiency

SCS led to an estimated savings of EUR 5 million between 2012‑16, yet evidence in the broader literature is scarce

An analysis undertaken by SCS administrators estimated that between 2012 and 2016, the service led to cost savings of EUR 5.12 million. The calculation is based on the assumption that SCS reduces the time taken to deliver services and that each minute saved reduces costs by EUR 0.5.

Evidence on patient portal efficiency gains within the broader literature are summarised in Box 5.3.

Box 5.3. The efficiency of patient-provider portals: Findings from the literature

Patient-provider portals are associated with several efficiency gains. Patient portals can reduce inpatient and emergency care visits due to an improvement in preventative care, chronic disease management and medication adherence. They are also associated with short-term efficiency gains resulting from saved time (e.g. reduction in travel time for patients, reduced burden on caregivers) (Kruse et al., 2015[5]).

Despite potential savings, the literature on the efficiency of patient-provider portals is scarce, further, information that is available shows mixed results (Goldzweig et al., 2013[6]). A systematic review on the impact of patient-provider portals on efficiency/utilisation found that of the studies analysed:

Three recorded no change in utilisation of healthcare services between portal users and nonusers

One recorded a decrease in primary care visits and an increase in telephone visits for users

One recorded an increase in utilisation of healthcare services after the introduction of a portal system (Goldzweig et al., 2013[6]).

Findings from Goldzweig et al. (2013[6]) are supported by a recent umbrella review of patient-provider portals, which concluded that the evidence supporting a link between portal use and hospitalisations emergency department visits, as well as office, primary, specialists or after-hours visits was low quality (Antonio, Petrovskaya and Lau, 2020[4]). Similarly, the review concluded there was only low quality evidence to support a reduction in provider workload and moderate strength evidence that portals had no impact on workload (Antonio, Petrovskaya and Lau, 2020[4]).

1. Of the remaining two studies, one examined medical adherence only while the other examined differences between two types of portals.

Equity

The SCS is free‑of-charge and easy to use, but may be less accessible by disadvantaged population groups

Oulu is available free of charge to all citizens of Oulu who have access to the internet and a bank account or mobile phone. By not charging a fee, individuals from lower socio‑economic status backgrounds are more likely to access the service. SCS also takes into account the needs of certain disadvantaged groups by providing services in a format that enhances usability for those with a disability. For example, the video platform has an easy to use function for people with chronic illnesses or a disability.

SCS is currently available in Finnish, the official language of the country, however, there are plans to expand to other languages, namely English, Arabic, Dari and Somali.

Despite processes to ensure disadvantaged population groups have access to SCS, like any digital health intervention, there is a risk that groups with the greatest need for the service have the lowest level of access. An umbrella review of patient portals in 2020 found patient portal users were more likely to have a higher income and education level, similarly those with lower health literacy and numeracy skills were less likely to be portal users (Antonio, Petrovskaya and Lau, 2020[4]). These findings align with OECD data for Finland which showed that 86% of people in the highest income quartile had used the internet to search for health related information in the past three months compared to 65% in the lowest income quartile (nevertheless, both of these figures are markedly higher than the EU average of 63% and 45%, respectively).

Evidence‑base

The impact of patient-provider portals is supported by findings from systematic and umbrella reviews

As outlined under the “Intervention description”, SCS has four key objectives. Evidence from SCS is available for two of these objectives – “improve access” and “reduce pressure on healthcare services”. For the remaining two objectives – “improve patient outcomes and safety” and “empower people” – evidence was drawn from the broader literature on patient-provider portals.

The evidence‑based criterion explores the quality of evidence used for each of these objectives, which includes systematic and umbrella reviews (see Box 5.4). For this reason, the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies from the Effective Public Health Practice Project was not used as it is more suitable when assessing singular studies.

Box 5.4. Quality of evidence supporting patient-provider portals

Summarised below is the quality of evidence used to assess SCS’s against its four key objectives.

Improve access

Data on the number of users, logins, message and services received via SCS were measured using routine electronic data. The data is accurate and reliable given it is stored in a sophisticated electronic health information system.

Improve patient outcomes and safety

The impact of patient-provider portals on outcomes and safety was assessed using information from three recent systematic or umbrella reviews:

Han et al. (2019[3]) undertook a systematic review to assess the impact of patient portals on patient outcomes. In total, 24 studies met the inclusion criteria, of which: 10 were RCTs (9 high quality and 1 medium quality); 7 were quasi‑experimental (6 high quality and 1 low quality); 6 were cohort studies (4 high quality and 2 moderate quality); and 1 mixed-method study (high quality).

Atonio et al. (2020[4]) used an umbrella review to synthesis the “state of evidence” on patient-provider portals. Their study included 14 reviews, whose quality was assessed using GRADE and (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations) and CERQual (Confidence in the Evidence from Review of Qualitative Research). The quality of evidence to assess behavioural outcomes (medication adherence and use of preventative services) was of moderate quality, while evidence on clinical outcomes was low-to-moderate quality.

Ammenwerth et al. (2019[2]) identified 10 RCTs from a systematic review of the literature on the impact of patient portals on empowerment and health outcomes. RCTs are considered the “gold standard” for evaluating the effectiveness of interventions.

Empower people

Atonio et al.’s (2020[4]) umbrella review rated evidence supporting the impact of patient portals on patient empowerment as moderate‑quality.

Reduce pressure on healthcare services

A predictive study based on routine patient data was used to estimate savings generated from SCS. Several assumptions were used to perform the analysis, which is common when necessary information to calculate a precise figure is not available. Nevertheless, results should be interpreted cautiously.

Goldzweig (2013[6]) used a systemic review to assess the impact of patient portals on health outcomes, satisfaction, efficiency and attitudes.

Atonio et al. (2020[4]) rated evidence on the link between portal use and healthcare utilisation as low quality.

Extent of coverage

The mean adoption rate of SCS is higher than the average calculated in a recent systematic review and meta‑analysis

The proportion of eligible Oulu citizens who logged into SCS has grown markedly since 2012 – from 11% to 34% (Figure 5.2). This is higher than the mean adoption rate of 23% estimated within a 2017 systematic review and meta‑analysis of patient portals (Fraccaro et al., 2017[7]).

Figure 5.2. Adoption rate, 2012‑20

Source: Data provided by Oulu Self Care Service administrators; Statistics Finland (2020[8]), “Key figures on population by Area, Information and Year, 1999‑2020”, https://www.stat.fi/index_en.html; Fraccaro et al. (2017[7]), “Patient portal adoption rates: A systematic literature review and meta‑analysis”, https://doi.org/10.3233/978-1-61499-830-3-79.

The majority of SCS users are women (60%), further a significant proportion are aged 65 years and over (22%) (Figure 5.3). Given people aged 65 years and over in Oulu comprise 16% of the population, these results indicate the older population are comfortable using digital technology to access healthcare (Statistics Finland, 2020[9]).

Figure 5.3. Breakdown of SCS users by age and gender – 2020

Source: Data provided by Oulu Self Care Service administrators.

Healthcare professionals in Finland are digitally literate resulting in high uptake of digital tools, including patient-provider portals

Finland has prioritised building a digitally literate health workforce. Digital health literacy is a core competency for health professionals working in Finland. For example, every university in Finland plans to provide nurses and medical students with streamlined digital health education – MEDigi. The aim of MEDigi is to harmonise and digitise national teaching to ensure medical graduates have the appropriate digital skills. Results from a recent eHealth survey in Europe reflect this commitment with Finland recording the third highest eHealth adoption rate amongst GPs (European Commission, 2018[10]).1

A digitally literate health workforce has led to a high uptake of SCS amongst professionals. As of 2020, over 600 primary care professionals use SCS,2 most of which are either doctors or nurses. Between 2012 and 2020, the number doctors and nurses registered with SCS increased by 173% and 62%, respectively.

Policy options to enhance performance

Successful patient-provider portals are integrated with patient data (e.g. EHRs), provide clinical decision support tools, and offer secure messaging and ePrescriptions, all of which are features of Oulu’s SCS (Shaw, Hines and Kielly-Carroll, 2018[11]). Nevertheless, policy options to enhance the performance of Oulu’s SCS are available to SCS administrators and policy makers.

Enhancing effectiveness

Higher levels of population health and digital health literacy (HL) will help SCS achieve its objectives. HL refers to an “individual’s knowledge, motivation and skills to access, understand, evaluate and apply health information” (OECD, 2018[12]). When people are health literate they are more likely to act on health information they receive, take greater responsibility for their own health, as well as engage in shared decision-making. Several interventions to boost HL levels exist in Finland including health education courses taught in schools, as well courses that teach participants basic skills on how to manage challenges associated with poor health (Evivo international programme) (OECD, 2018[12]). Relevant policy makers should continue efforts to boost HL drawing upon OECD’s four‑pronged policy approach (see Box 5.5).

Box 5.5. Building population health literacy

Recent analysis estimated that more than half of OECD countries with available data had low levels of HL. To address low rates of adult health literacy, OECD have outlined a four‑pronged policy approach, which align:

Strengthen the health system role: establish national strategies and framework designed to address HL

Acknowledge the importance of HL through research: measure and monitor the progress of HL interventions to better understand what policies work

Improve data infrastructure: improve international comparisons of HL as well as monitoring HL levels over time

Strengthen international collaboration: share best practice interventions to boost HL across countries.

Source: OECD (2018[12]), “Health literacy for people‑centred care: where do OECD countries stand?”, https://www.doi.org/10.1787/d8494d3a-en.

Enhancing efficiency

Efficiency is calculated by obtaining information on effectiveness and expressing it in relation to inputs used. Therefore, policies to boost effectiveness without significant increases in costs will have a positive impact on efficiency.

Enhancing equity

Execute plans to increase the number of languages available on SCS. In the City of Oulu, the proportion of people speaking a foreign language grew by 3.2 percentage points between 2000 and 2019 (1.2% to 4.4%) (Statistics Finland, 2019[13]). To ensure SCS is accessible by all residents, plans to expand the number of languages available on the service are encouraged – i.e. Arabic, Dari and Somali. These languages are frequently spoken by refugees (e.g. from Afghanistan and Somalia) who typically experience worse health outcomes and therefore have the most to gain from better access to care.

Support adoption of SCS among disadvantaged population groups. Certain disadvantaged population groups are less likely to access and therefore benefit from digital health interventions, such as patient-provider portals. Therefore, uptake of SCS among disadvantaged population groups should be a key priority. In Estonia, for example, patients with lower levels of digital literacy can receive training on how to use digital tools. Further, as part of its eHealth strategy, Estonia prioritises interventions that improve the skills needed to self-manage and self-educate using online solutions (OECD, 2019[14]).

Enhancing the evidence‑base

Undertake an in-depth study into the impact of SCS on patient outcomes, and healthcare utilisation and costs. SCS is tethered to Finland’s national EHR, which is one of the most advanced among OECD and EU countries (Oderkirk, 2017[15]). Administrators of Oulu’s SCS are encouraged to capitalise on this advantage by evaluating the impact of SCS on healthcare outcomes and utilisation, and thus costs. Indicators of interest are summarised in Box 5.6, which could be compared between SCS users and non-users, for example, using propensity score matching (an econometric technique that creates an artificial control group by matching each SCS user with a non-user based on available characteristics).

Box 5.6. Indicators measuring the impact of patient-provider portals

This box lists example indicators to evaluate the impact of patient-provider portals, such as SCS. For example, this data would allow researchers to examine whether SCS increased use of primary services and the flow-on affect this has on secondary care use.

Outcomes

Blood pressure control

Cholesterol control

Glycaemic control

Weight (BMI)

Utilisation

Use of preventative services (e.g. cancer screening, papsmear tests, blood pressure checks and vaccinations)

Primary care visits

Specialist visits

Hospitalisations and average length of stay

Emergency department visits

Enhancing extent of coverage

Encourage health professionals to promote SCS to patients. There are high levels of public trust in the health workforce; therefore, health professionals can play an important role in boosting uptake of SCS amongst patients. A way of encouraging adoption of digital tools is to make them available in provider settings and have “professionals demonstrate and support their use” (OECD, 2019[14]).

Promote SCS using a targeted approach. The more useful an intervention is perceived to be, the higher the uptake. The usefulness of SCS will differ across population groups: for example, being able to upload medical information from home is of high use to multimorbid patients, but of less concern to younger populations who may perceive online appointment bookings as SCS’s key feature. For this reason, promotional activities should target different population groups.

Ensure SCS remains a trusted and non-burdensome tool for health professionals. Uptake of SCS among health professionals in Oulu is high. To maintain high levels of engagement, it is important that update and amendments to SCS (OECD, 2019[14]):

Are evidence‑based in order to maintain trust among health professionals and patients

Include input and feedback from health professionals and patients, who are the end-users

Do not negatively affect usability and continue to be integrated into current practice (i.e. the portal does not increase the workload of health professionals).

Improve access to children and teenagers. As specified by Oulu SCS administrators, better access for children and teenagers is needed – i.e. either with direct access or via their parents. This requires an update to current legislation and technical solutions to ensure privacy and safe access.

Boost population HL so that patients understand information presented and thus the usefulness of the service. Policy options to enhance HL are explored under “Enhancing effectiveness”.

Transferability assessment

This section explores the transferability of SCS and is broken into three components: 1) an examination of previous transfers; 2) a transferability assessment using publicly available data; and 3) additional considerations for policy makers interested in transferring SCS.

Previous transfers

Oulu’s SCS originally started as a pilot programme at one of Oulu’s technology health centre in 2008. Following the success of the pilot, the programme was scaled-up across the whole of Oulu in 2011 and later transferred to the municipalities of Oulunkaari and Raahe (with some necessary adaptions).

SCS has not been transferred to another country, however, patient portals are common in OECD and EU countries – for example, based on a 2016 EHR survey, 12 (out of 15) OECD countries reported they have or are in the process of implementing an ICT system that gives people access to their own health data (OECD, 2019[14]).

Transferability assessment

The following section outlines the methodological framework to assess transferability and results from the assessment.

Methodological framework

Details on the methodological framework to assess transferability can be found in Annex A.

Several indicators to assess the transferability of SCS were identified (see Table 5.1). Indicators were drawn from international databases and surveys to maximise coverage across OECD and non-OECD European countries. Please note, the assessment is intentionally high level given the availability of public data.

Table 5.1. Indicators to assess transferability – Oulu’s Self Care Service

|

Indicator |

Reasoning |

Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

|

Population context |

||

|

% of individuals using the Internet for seeking health information in the last 3 months |

SCS is more transferable to a country with a population comfortable seeking health information online |

🡹 value = more transferable |

|

ICT Development Index* |

SCS is more transferable to a country with a population living in a more digitally advanced country |

🡹 value = more transferable |

|

Sector context (primary care / digital care) |

||

|

% of tertiary institutions (public and private) that offer ICT for health (eHealth) courses |

SCS is more transferable if health professional students receive eHealth training |

🡹 value = more transferable |

|

% of institutions or associations offering in-service training in the use of ICT for health as part of the continuing education of health professionals |

SCS is more transferable if health professionals have appropriate eHealth training |

🡹 value = more transferable |

|

Legislation exists to protect the privacy of personally identifiable data of individuals, irrespective of whether it is in paper or digital format |

SCS is more transferable to countries with legislation to protect patient data (i.e. patients are confident their data is secure) |

‘Yes’ = more transferable |

|

eHealth composite index of adoption amongst GPs** |

SCS is more transferable to countries where GPs frequently use eHealth technologies |

🡹 value = more transferable |

|

Proportion of physicians in primary care facilities using electronic health records (EHRs) |

Patient portals are linked to information from EHRs, therefore, SCS is more transferable to countries where EHRs are used in primary care |

🡹 value = more transferable |

|

Political context |

||

|

A national eHealth policy or strategy exists |

SCS is more transferable if the government is supportive of eHealth |

‘Yes’ = more transferable |

|

A national health information system (HIS) policy or strategy exists |

SCS is more likely to be successful if the government is supportive of improving health information systems |

‘Yes’ = more transferable |

|

Economic context |

||

|

% of funding contribution for eHealth programmes provided by public funding sources over the previous two years |

SCS is more likely to be successful in a country whose government spends more on eHealth |

🡹 value = more transferable |

Note: *The ICT development index represents a country’s information and communication technology capability. It is a composite indicator reflecting ICT readiness, intensity and impact (ITU, 2020[16]). **The eHealth composite index of adoption amongst GPs is made up of adoption in regards to electronic health records, telehealth, personal health records and health information exchange (European Commission, 2018[10]).

Source: ITU (2020[16]), “The ICT Development Index (IDI): conceptual framework and methodology”, https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Pages/publications/mis/methodology.aspx; OECD (2019[17]), “Individuals using the Internet for seeking health information – last 3 m (%) (all individuals aged 16‑74)”; European Commission (2018[10]), “Benchmarking Deployment of eHealth among General Practitioners (2018)”, https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/d1286ce7-5c05-11e9-9c52-01aa75ed71a1; WHO (2015[18]), “Atlas of eHealth country profiles: The use of eHealth in support of universal health coverage”, https://www.afro.who.int/publications/atlas-ehealth-country-profiles-use-ehealth-support-universal-health-coverage; Odenkirk (2017[15]), “Readiness of electronic health record systems to contribute to national health information and research”, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9e296bf3-en.

Results

The majority of countries with available data have developed a national eHealth policy and/or a national health information system policy indicating there is political support for digital health interventions, such as patient-provider portals (see Table 5.2). These policies are supported by government funding with 26 out of 35 countries (with available data) stating a “very high” (>75%) proportion of funding for eHealth comes from public sources.

Implementing a patient-provider portal, however, may require additional resources (time, financial, expertise) when compared to Finland, given the country is a digital health leader. For example:

Finland recorded the highest proportion of people seeking healthcare online (76% versus the OECD/EU average of 54%) and the second highest eHealth adoption rate amongst GPs (2.64 composite score compared to the 2.1 average amongst European countries with available data)

Between 25‑50% of tertiary institutions and associations offer health professionals ICT training, both during training and as part of continuing education (i.e. a “Medium” proportion of institutions)

100% of primary care physician offices use electronic healthcare records compared to an average of 79% among countries with available data

Finland has an ICT development index value of 8.1, which was one of the highest amongst examined countries.

Results from the transferability assessment indicate Nordic countries such as Denmark, Iceland and Sweden are suitable candidates for this intervention. This finding aligns with feedback from Oulu SCS administrators who stated that “Nordic Countries, most of which follow similar social and health strategies and have similar infrastructure and population characteristics (web use, technologically-experienced users even in older age groups) would be good candidates for adopting such a service” (Lupiañez-Villanueva, Sachinopoulou and Thebe, 2015[1]).

Table 5.2. Transferability assessment by country (OECD and non-OECD European countries) – Oulu’s Self Care Service

A darker shade indicates SCS is more transferable for that particular country

|

Country |

% individuals seeking health information online |

ICT index value |

% tertiary institutions offering eHealth training |

% institutions offering in-service training in eHealth |

Legislation to protect digital patient data |

eHealth adoption amongst GPs (composite score) |

% EHR use in primary care |

National eHealth policy |

National HIS* policy |

% public funding for eHealth programs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Finland |

76 |

8.1 |

Medium |

Medium |

Yes |

2.644 |

100 |

Yes |

Yes |

Very High |

|

Australia |

42 |

8.2 |

Medium |

High |

n/a |

n/a |

96 |

Yes |

No |

Very High |

|

Austria |

53 |

7.5 |

Low |

Low |

Yes |

1.914 |

80 |

No |

Yes |

Very High |

|

Belgium |

49 |

7.7 |

Low |

Low |

Yes |

2.067 |

n/a |

Yes |

Yes |

Very High |

|

Bulgaria |

34 |

6.4 |

Medium |

Medium |

Yes |

1.809 |

n/a |

Yes |

Included in eHealth policy |

Low |

|

Canada |

59 |

7.6 |

High |

Low |

Yes |

n/a |

77 |

Yes |

No |

Very High |

|

Chile |

27 |

6.1 |

Low |

Low |

Yes |

n/a |

65 |

Yes |

Yes |

Very High |

|

Colombia |

41 |

5.0 |

n/a |

n/a |

Yes |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

Very High |

|

Costa Rica |

44 |

6.0 |

Medium |

Medium |

Yes |

n/a |

n/a |

Yes |

Yes |

Very High |

|

Croatia |

53 |

6.8 |

Low |

Medium |

Yes |

2.18 |

3 |

Yes |

Yes |

Very High |

|

Cyprus |

58 |

6.3 |

Medium |

Low |

n/a |

1.934 |

n/a |

Yes |

Included in eHealth policy |

Very High |

|

Czech Republic |

56 |

7.2 |

Medium |

n/a |

Yes |

2.063 |

n/a |

No |

Yes |

Low |

|

Denmark |

67 |

8.8 |

Medium |

Very high |

Yes |

2.862 |

100 |

Yes |

Included in eHealth policy |

Very High |

|

Estonia |

60 |

8.0 |

Medium |

Low |

Yes |

2.785 |

99 |

Yes |

Yes |

Very High |

|

France |

50 |

8.0 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

2.054 |

80 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Germany |

66 |

8.1 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

1.941 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Greece |

50 |

6.9 |

Medium |

Medium |

Yes |

1.785 |

100 |

Yes |

Yes |

Very High |

|

Hungary |

60 |

6.6 |

Low |

n/a |

Yes |

2.028 |

n/a |

No |

No |

Very High |

|

Iceland |

65 |

8.7 |

Very High |

Very high |

Yes |

n/a |

100 |

Yes |

Yes |

Very High |

|

Ireland |

57 |

7.7 |

n/a |

Low |

Yes |

2.103 |

95 |

Yes |

Yes |

Low |

|

Israel |

50 |

7.3 |

High |

Low |

Yes |

n/a |

100 |

No |

No |

Very High |

|

Italy |

35 |

6.9 |

Low |

High |

Yes |

2.185 |

n/a |

Yes |

Yes |

Very High |

|

Japan |

n/a |

8.3 |

n/a |

n/a |

Yes |

n/a |

36 |

Yes |

Yes |

n/a |

|

Korea |

50 |

8.8 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Latvia |

48 |

6.9 |

Low |

Low |

Yes |

1.826 |

70 |

Yes |

Included in eHealth policy |

Low |

|

Lithuania |

61 |

7.0 |

Medium |

Low |

Yes |

1.647 |

n/a |

Yes |

Included in eHealth policy |

High |

|

Luxembourg |

58 |

8.3 |

Low |

Low |

Yes |

1.776 |

n/a |

Yes |

Yes |

Very High |

|

Malta |

59 |

7.5 |

Very High |

Very high |

Yes |

n/a |

n/a |

No |

No |

Very High |

|

Mexico |

50 |

4.5 |

Medium |

Low |

Yes |

n/a |

30 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Netherlands |

74 |

8.4 |

High |

High |

Yes |

n/a |

n/a |

Yes |

Included in eHealth policy |

Very High |

|

New Zealand |

n/a |

8.1 |

Medium |

Very high |

Yes |

n/a |

95 |

Yes |

No |

Low |

|

Norway |

69 |

8.4 |

Low |

Medium |

Yes |

n/a |

100 |

Yes |

Yes |

Very High |

|

Poland |

47 |

6.6 |

High |

Medium |

Yes |

1.837 |

30 |

Yes |

Yes |

Very High |

|

Portugal |

49 |

6.6 |

Low |

Low |

Yes |

2.118 |

n/a |

No |

Yes |

High |

|

Romania |

33 |

5.9 |

n/a |

n/a |

Yes |

1.788 |

n/a |

Yes |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Slovak Republic |

53 |

6.7 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

1.756 |

89 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Slovenia |

48 |

7.1 |

High |

High |

Yes |

1.998 |

n/a |

No |

No |

Very High |

|

Spain |

60 |

7.5 |

Low |

Medium |

Yes |

2.365 |

99 |

No |

Yes |

Very High |

|

Sweden |

62 |

8.5 |

Very High |

Very high |

Yes |

2.522 |

100 |

Yes |

No |

Very High |

|

Switzerland |

67 |

8.5 |

Low |

Very high |

Yes |

n/a |

40 |

Yes |

Included in eHealth policy |

Low |

|

Türkiye |

51 |

5.5 |

n/a |

n/a |

Yes |

n/a |

n/a |

No |

No |

Low |

|

United Kingdom |

67 |

8.5 |

Medium |

High |

Yes |

2.517 |

99 |

Yes |

Yes |

Very High |

|

United States |

38 |

8.1 |

Low |

Low |

Yes |

n/a |

83 |

Yes |

Yes |

n/a |

Note: *HIS = health information system. n/a = data is missing.

Source: See Table 5.1.

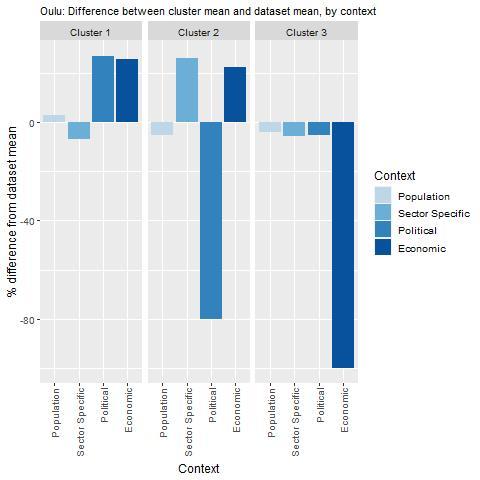

To help consolidate findings from the transferability assessment above, countries have been clustered into one of three groups, based on indicators reported in Table 5.1. Countries in clusters with more positive values have the greatest transfer potential. For further details on the methodological approach used, please refer to Annex A.

Key findings from each of the clusters are below with further details in Figure 5.4 and Table 5.3:

Countries in cluster one have population, political, and economic arrangements in place to transfer Oulu’s SCS, and are therefore good transfer candidates. Finland, which operates SCS, falls into this cluster.

A high proportion of funding for eHealth programs comes from the government for countries in cluster two, indicating SCS is likely to be affordable in the long-run. Further, these countries have sector specific arrangements in place that support SCS such as a digitally health literate workforce. However, prior to transferring SCS, these countries should undertake further analysis to ensure SCS aligns with overarching political priorities, which is necessary for long-term sustainability.

Countries in cluster are encouraged to undertake further analysis to ensure the right conditions are in place to support the transfer of SCS, in particular, to ensure the intervention is affordable in the long term.

Figure 5.4. Transferability assessment using clustering – Oulu’s Self Care Service

Note: Bar charts show percentage difference between cluster mean and dataset mean, for each indicator.

Source: See Table 5.1.

Table 5.3. Countries by cluster – Oulu’s Self Care Service

|

Cluster 1 |

Cluster 2 |

Cluster 3 |

|---|---|---|

|

Australia Austria Belgium Canada Chile Costa Rica Croatia Cyprus Denmark Estonia Finland Greece Iceland Italy Lithuania Luxembourg Netherlands Norway Poland Portugal United Kingdom United States |

Hungary Israel Malta Mexico Slovenia Spain Sweden |

Bulgaria Czech Republic Ireland Latvia New Zealand Switzerland Türkiye |

Note: Due to high levels of missing data, the following countries were omitted from the analysis: Colombia, France, Germany, Japan, Korea, Romania and the Slovak Republic.

New indicators to assess transferability

Data from publicly available dataset is not sufficient to assess the transferability of Oulu’s SCS. Therefore, Box 5.7 outlines several new indicators policy makers should consider before transferring SCS (or a similar patient-provider portal).

Box 5.7. New indicators, or factors, to consider when assessing transferability – Oulu’s Self Care Service

In addition to the indicators within the transferability assessment, policy makers are encouraged to collect data for the following indicators:

Population context

Do patients feel comfortable accessing healthcare online?

Do patients have the skills to access healthcare online?

What is the level of health literacy amongst patients?

Does the population trust their personal health information will be used, stored and managed appropriately?

Sector specific context (primary care / digital care)

Is patient data interoperable and integrated across different levels of care (including social care)?

Is patient data co‑ordinated across all levels of care? (i.e. there is a unique patient identifier)

Are healthcare providers supportive of patient-provider portals?

Do privacy laws support the integration of patient health data?

Does the legal framework support public-private partnerships for eHealth?*

Political context

Has the intervention received political support from key decision-makers?

Has the intervention received commitment from key decision-makers?

Economic context

What is the cost to national and local governments, various types of healthcare providers, patients, and other entities of implementing the intervention in the target setting?

Note: *This was a barrier for the City of Oulu where the legal framework forbid public funding for projects where public service providers worked with private companies.

Access

SCS services are available 24/7 and3 free‑of-charge to the residents of Oulu. To access SCS via a computer or mobile, users can login with their bank account details or a mobile code. Primary care professionals can access the SCS system by signing in using their organisation’s patient record system or via their ID card. Similar to citizens, primary care professionals are not obliged to use SCS as part of their service.

Conclusion and next steps

SCS is a patient-provider portal designed to improve primary care. In 2011, the City of Oulu, Finland, expanded its patient-provider portal, SCS, to all residents. SCS is a tool used in primary care, which offers patients a range of online services such as online appointments, ePrescriptions, and messaging with health professionals. SCS provides primary care professionals with tailored guidelines and care pathways based on patient data obtained from their EHR, which is tethered to the portal. The objectives of SCS are to improve access to care; improve patient outcomes, safety and empowerment; and reduce pressure on the health system.

SCS improves access to care and is estimated to have reduced costs by over EUR 5 million. Between 2012 and 2020, the number of SCS users increased by 235%, with the average person logging into the service 10 times per year. Over the same period, users have sent over 400 000 messages to health professionals and received over 18 000 online prescriptions. SCS proved to be a key resource during the COVID‑19 pandemic, with over 60 000 test results uploaded to the system (as of March 2021). Over years 2012‑16, SCS is estimated to have saved EUR 5.12 million based on the assumption that SCS reduces the time taken to deliver services.

The design of SCS considers the needs of disadvantaged population groups, yet access barriers remain. SCS is available free‑of-charge to residents of Oulu thereby improving access to individuals with a low SES. Further, SCS includes design features that improve usability for people with a disability. Nonetheless, like all digital health interventions, those most in need may experience access barriers, for example, due poor internet access.

Over one‑third of the Oulu’s population access SCS. Thirty-four percent of Oulu residents use SCS, which is above the mean patient portal adoption rate of 23% estimated in a recent systematic review and meta‑analysis. For this reason, SCS performs particularly well against the “Extent of coverage” best practice criterion. Adoption is also high amongst health professionals, which is attributable to the country’s focus on building a digitally literate health workforce.

SCS is a global leader in the area of patient portals, yet there are opportunities to enhance its performance. To enhance effectiveness, boosting levels of population HL and digital HL will help patients better understand the information uploaded to SCS, act on that information and take greater responsibility for their own health. To reduce health inequalities, SCS administrators should prioritise plans to expand the number of languages available, in particular those spoken by refugees in the country. To enhance the evidence base, researchers should take advantage of Finland’s rich data source and evaluate the impact of SCS on patient outcomes and utilisation of healthcare services. To enhance the extent of coverage, several options are available including efforts to encourage professionals to promote SCS to their patients.

Results from the transferability assessment indicate Nordic countries are suitable candidates for SCS. Based on publicly available indicators, countries most suited to transfer SCS (or a similar patient portal) are located in Europe’s Nordic region. Nonetheless, there is clear political will to implement patient portals as evidenced by a recent OECD survey showing 80% of countries have or have plans to make individual patient data available via a portal.

Next steps for policy makers and funding agencies interested in SCS are provided in Box 5.8.

Box 5.8. Next steps for policy makers and funding agencies – New indicators, or factors to consider, when assessing transferability

Next steps for policy makers and funding agencies to enhance SCS are listed below:

Support policy efforts to boost population health literacy and digital health literacy

Support future evaluations of SCS which draw upon patient data collected as part of Finland’s national EHR

Promote findings from the SCS case study to better understand what countries/regions are interested in transferring the intervention (or a similar patient portal).

References

[2] Ammenwerth, E. et al. (2019), Effects of adult patient portals on patient empowerment and health-related outcomes: A systematic review, IOS Press, https://doi.org/10.3233/SHTI190397.

[4] Antonio, M., O. Petrovskaya and F. Lau (2020), “The State of Evidence in Patient Portals: Umbrella Review”, Journal of Medical Internet Research, Vol. 22/11, p. e23851, https://doi.org/10.2196/23851.

[10] European Commission (2018), Benchmarking Deployment of eHealth among General Practitioners (2018), https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/d1286ce7-5c05-11e9-9c52-01aa75ed71a1.

[7] Fraccaro, P. et al. (2017), Patient portal adoption rates: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis, IOS Press, https://doi.org/10.3233/978-1-61499-830-3-79.

[6] Goldzweig, C. et al. (2013), “Electronic Patient Portals: Evidence on Health Outcomes, Satisfaction, Efficiency, and Attitudes”, Annals of Internal Medicine, Vol. 159/10, p. 677, https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-159-10-201311190-00006.

[3] Han, H. et al. (2019), “Using Patient Portals to Improve Patient Outcomes: Systematic Review”, JMIR Human Factors, Vol. 6/4, p. e15038, https://doi.org/10.2196/15038.

[16] ITU (2020), The ICT Development Index (IDI): conceptual framework and methodology, https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Pages/publications/mis/methodology.aspx (accessed on 26 February 2021).

[5] Kruse, C. et al. (2015), “Patient and Provider Attitudes Toward the Use of Patient Portals for the Management of Chronic Disease: A Systematic Review”, Journal of Medical Internet Research, Vol. 17/2, p. e40, https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3703.

[1] Lupiañez-Villanueva, F., A. Sachinopoulou and A. Thebe (2015), Strategic Intelligence Monitor on Personal Health Systems Phase 3 (SIMPHS3): Oulu Self-Care (Finland) Case Study Report, European Commission JRC Science and Policy Reports, https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/bitstream/JRC94492/jrc94492.pdf.

[15] Oderkirk, J. (2017), “Readiness of electronic health record systems to contribute to national health information and research”, OECD Health Working Papers, No. 99, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9e296bf3-en.

[14] OECD (2019), Health in the 21st Century: Putting Data to Work for Stronger Health Systems, OECD Health Policy Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/e3b23f8e-en.

[17] OECD (2019), Individuals using the Internet for seeking health information - last 3 m (%) (all individuals aged 16-74), Dataset: ICT Access and Usage by Households and Individuals.

[12] OECD (2018), “Health literacy for people-centred care: Where do OECD countries stand?”, OECD Health Working Papers, No. 107, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/d8494d3a-en.

[11] Shaw, T., M. Hines and C. Kielly-Carroll (2018), Impact of Digital Health on the Safety and Quality of Health Care, Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, Sydney, https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications-and-resources/resource-library/impact-digital-health-safety-and-quality-health-care.

[9] Statistics Finland (2020), Key figures on population by Area, Information and Year (share of persons aged 65 or over, %).

[8] Statistics Finland (2020), Key figures on population by Area, Information and Year, 1999-2020, https://www.stat.fi/index_en.html.

[13] Statistics Finland (2019), Population 31.12. by Area, Language, Sex, Year and Information.

[18] WHO (2015), Atlas of eHealth country profiles: The use of eHealth in support of universal health coverage, Global Observatory for eHealth, https://www.afro.who.int/publications/atlas-ehealth-country-profiles-use-ehealth-support-universal-health-coverage.

Notes

← 1. eHealth adoption was measured using a composite indicator reflecting use of electronic health records, telehealth, personal health records and health information exchange.

← 2. In addition to digital health literacy training provided to all health professionals in Finland, those working in the City of Oulu receive 1 to 2 hour training session on how to use SCS.

← 3. Online interaction with primary care professionals is only available during office hours.