This chapter covers the OptiMedis integrated care model operating in certain regions in Germany (and is a “good practice” within the EU Joint Action on implementation of digitally enabled integrated person-centred care). The case study includes an assessment of the OptiMedis model of care against the five best practice criteria, policy options to enhance performance and an assessment of its transferability to other OECD and EU27 countries.

Integrating Care to Prevent and Manage Chronic Diseases

3. OptiMedis, regionally based integrated care model

Abstract

OptiMedis regionally based integrated care model: Case study overview

Description: The OptiMedis integrated care model emerged in 2005 following reforms in Germany to promote care co‑ordination. The model of care, which operates in the west (state of Hesse) and south-west region (state of Baden-Württemberg) of Germany, aims to improve patient experiences and population health, while reducing per capita costs. A key feature of the care model is its “shared savings contract”, which incentivises the delivery of high-quality, preventative care. As part of this contract, positive differences between the money sickness funds receive from the country’s central payment authority and the mean costs of all insurees is shared between the sickness funds and OptiMedis (a healthcare management company).

Best practice assessment:

OECD best practice assessment of the OptiMedis integrated care model

|

Criteria |

Assessment |

|---|---|

|

Effectiveness |

Implementing the OptiMedis integrated care model across Germany is estimated to lead to an increase of 146 441 life years (LYs) and 97 558 disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) by 2050 Transferring OptiMedis to the eligible population across EU27 countries is estimated to result in 9.7 LYs and 6.5 DALYs gained per 100 000 people on average per year between 2022 and 2050 |

|

Efficiency |

Over the modelled period, 2022‑50, the OECD-SPHeP NCD model estimates that OptiMedis would lead to cumulative health expenditure savings of EUR 3 470 per person Average annual health expenditure (HE) savings as a proportion of total HE is estimated at 4%, on average, across EU‑27 countries |

|

Equity |

The OptiMedis model of care offers outreach services to patients through access to health coaches, healthcare navigators or access to a Health Kiosk. This Kiosk provides tailored health and social advice in multiple languages (currently only available in the City of Hamburg). Core features of the integrated care model aim to reduce inequalities, for example, by standardising care pathways. Given complex health needs are more prominent among disadvantaged groups, the integrated care model has the potential to disproportionately benefit such groups, given such patients voluntarily enrol. |

|

Evidence‑base |

Studies evaluating the effectiveness and efficiency of OptiMedis used strong methods for data collection and analysis. |

|

Extent of coverage |

Approximately one‑third of eligible residents are enrolled in the OptiMedis integrated care model (data for health professionals is not available) |

Enhancement options: to enhance the performance of the OptiMedis model and other population-based integrated care models, policy makers could consider ways to better target patients at high-risk of complex health needs. This will allow patients to access preventative programs sooner leading to better health outcomes while lowering costs. Other policies include, but are not limited to, expanding programs targeting disadvantaged groups and applying more rigorous methodologies to future evaluation studies.

Transferability: The OptiMedis model exists in the west (state of Hesse) and south-west (state of Baden-Württemberg) of Germany, and there are discussions to expand it to other regions in the country. Any future implementations should incorporate the core features of the model, such as obtaining long-term contracts. Although not yet transferred to regions outside Germany, underlying features that support the model exist in most OECD countries – e.g. preventative care, case management, and electronic patient data sharing. Further, there are active discussions to transfer this model of care to Belgium and France.

Conclusion: OptiMedis is a population-based integrated care model operating in parts of Germany. The model has the potential to increase life years and disability-adjusted life years gained, while simultaneously reducing healthcare costs. Feedback from OptiMedis administrators indicate the model can be successfully transferred in other regions with different populations and health service arrangements.

Intervention description

This section outlines Germany’s healthcare system, at a high level, followed by a description of the OptiMedis model.

Germany’s healthcare system

Germany operates a compulsory social health insurance. In the late 19th century, Germany introduced the world’s first social health insurance (SHI) system, built on the foundation of solidarity. Today, the majority of residents within the country are required to obtain SHI from one of the 103 sickness funds. However, those who earn over a certain income (i.e. EUR 62 550) and certain professionals (e.g. self-employed and civil servants) can opt out and purchase health insurance instead. As of 2020, 87% of residents are covered by SHI with the remaining 11% opting for private insurance (the remaining 2% are covered by special programs) (Blümel et al., 2020[1]).

Germany has a world-class healthcare system, but it is expensive. Residents living in Germany have access to universal health insurance, which covers a comprehensive set of benefits with minimal cost-sharing. For this reason, the healthcare system is highly regarded. Nevertheless, it is relatively expensive with health expenditure comprising 11.7%1 of gross domestic product (GDP). Among OECD countries, this figure is only surpassed by the United States (16.8%) (OECD, 2020[2]).

Relatively high healthcare expenditure has not translated into better health outcomes. For example, as of 2019,2 life expectancy in Germany reached 81.4 years, which ranks it 24th among 38 OECD countries. Further, around two‑thirds (66%) of the population report being in good health, which is lower than the EU average of 69% (OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2021[3]).

A lack of co‑ordination is considered one of the key reasons Germany’s healthcare system has not performed as well as expected. Germany’s healthcare system is complex with the separation of legislative, planning and regulatory power across different sectors – i.e. ambulatory, inpatient, long-term care, and public health (for full details see (Blümel et al., 2020[1])). For this reason, the healthcare system lacks co‑ordination, which negatively affects service delivery and therefore health outcomes. Another factor contributing to Germany’s overall performance is its reliance on secondary care. As an example, hospital admissions for asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are above the EU average in Germany, indicating lack of effective primary care treatment and self-management support, as well as a focus on secondary treatment (OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2021[3]). Consequently, the estimated cost of avoidable hospital admissions is over eight times higher than the OECD30 average (USD 7.2 million versus USD 0.84 million per year) (OECD, 2020[4]).

Germany introduced various policies to improve care co‑ordination in recent years. Given the difficulty in implementing large scale, structural changes to the German healthcare system, policy makers have instead opted to implement a series of reforms that encourage care co‑ordination. This includes the 2004 Social Health Insurance Modernisation Act, which “introduced a legal framework for integrated care provision and strengthened primary care” (Amelung et al., 2017[5]). Following this Act, a number of voluntary integrated care contracts emerged, which patients had the option of joining. One of the integrated care models to emerge was the OptiMedis regionally based integrated care model (hereafter, the OptiMedis model), which is the focus of this case study.

The OptiMedis model

The regionally based integrated care model by OptiMedis emerged in 2005. The model is driven by regional networks involving physicians and other stakeholders and aims to bring together healthcare providers at all levels of a determined region into one integrated network, while assuming accountability for the health and healthcare of the region’s population. People can voluntarily enrol with the model who then have access to a wide range of healthcare interventions, ranging from disease management programs to discounts for exercise facilities.

Further information on the model’s objectives, target population, governance and payment system, and interventions provided are summarised below.

Objectives

The OptiMedis model promotes care co‑ordination across all sectors with a focus on prevention and introduces evidence‑based interventions to address identified healthcare needs. Through doing so, it aims to achieve the following four objectives (also referred to as the “Quadruple aim approach”):

Improve patient experiences of care (quality and satisfaction)

Improve the health of the population

Reduce the per capita cost of healthcare

Improve work/life balance for healthcare providers.

Target population

People of all ages, regardless of their disease history, can enrol in the OptiMedis model where it is offered. Given the model’s focus on co‑ordination, it is particularly beneficial to individuals living with one or multiple chronic conditions who require care from several health professionals.

Governance and payment model

The OptiMedis model involves the creation of a regional integrator, an institution in charge of managing the network integration with a physical presence in the region and legally constituted as an enterprise. Healthcare providers in partnership with the network participate in the regional integrator in the capacity of partners, owners or associates (depending on the particular context) together with OptiMedis AG, a German healthcare management company with an expertise in management support, business intelligence and health data analytics.

A key feature of the OptiMedis model is the payment system, which is based on a “shared savings contract”. The contract is drawn between the integrated network on one side and sickness funds on the other. As part of this contract, positive differences between expected costs3 and the real healthcare costs of the population the network is accountable for are considered “savings” and are shared between the integrated network and sickness funds.

The share of savings received by the integrated network is used to finance integration efforts, including performance bonuses and operations of the regional integrator. Remaining profits are re‑invested in the regional healthcare system.

To avoid an under provision of services as a way to generate savings, there are minimum quality standards that need to be complied with. The payment system, therefore, is designed so that there is a financial incentive to invest in delivering high-quality, efficient, preventative care.

Interventions provided

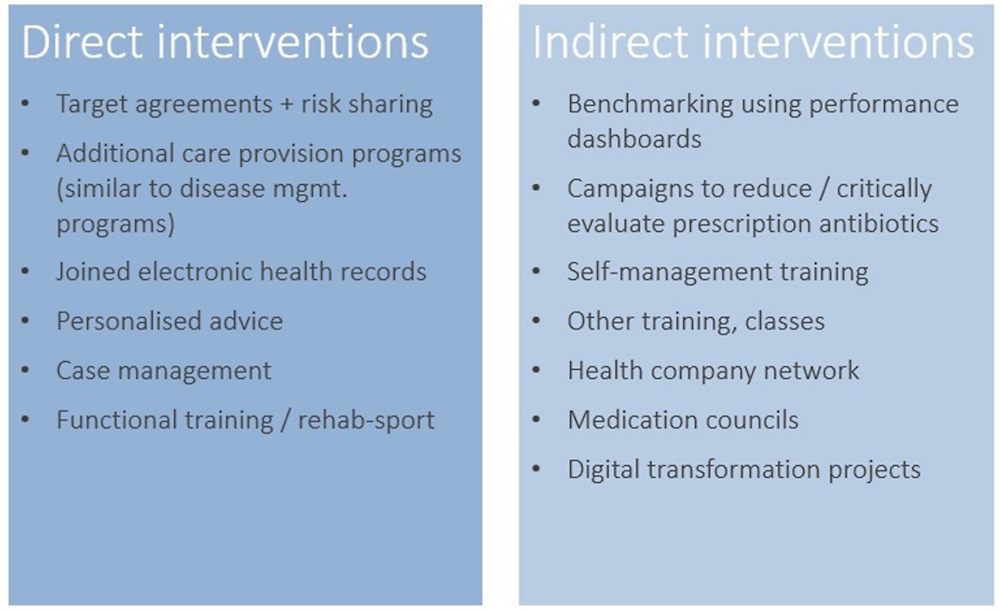

There are two types of value‑creating interventions within the OptiMedis model: direct interventions for people that are enrolled within the model, and indirect interventions, directed at improving system efficiency through providers at all levels of care (i.e. primary, secondary, tertiary, and long-term care) that are part of the network and public health campaigns Figure 3.1). The latter are available for the entire population accounted for the by the integrated network.

Figure 3.1. Interventions provided by the OptiMedis model of care

Each of the interventions listed are underlined by a common set of features, namely (The King’s Fund, 2022[6]):

Individual treatment plans and goal setting agreements between doctors and patients

Enhancing patient self-management and shared decision-making

Care planning based on the chronic care model, patient coaching and follow up care

Providing the right care at the right time

Overarching support through purposely designed system-wide electronic patient records and digital patient empowerment platforms. This is of particular interest given in Germany electronic sharing of patient data is relatively low (see Box 3.1).4

Box 3.1. Commonwealth Fund International Health Policy Survey of Primary Care Physicians

In 2019, the Commonwealth Fund surveyed 11 countries, including Germany, regarding the experience of physicians working in primary care. The questionnaire included several questions related to use of electronic patient data – results for Germany are summarised below:

12% of primary care physicians noted they are able to electronically exchange patient clinical summaries with doctors outside their practice

14% noted they are able to exchange lists of medications taken by a patient with doctors outside their practice

32% noted they are able to exchange laboratory and diagnostic test results with doctors outside their practice

For all three indicators, figures in Germany were the lowest among all surveyed countries.

Source: The Commonwealth Fund (2019[7]), “2 019 Commonwealth Fund International Health Policy Survey of Primary Care Physicians”, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/2019-12/PDF_2019_intl_hlt_policy_survey_primary_care_phys_CHARTPACK_12-10-2019.pdf,

OECD Best Practices Framework assessment

This section analyses the OptiMedis model against the five criteria within OECD’s Best Practice Identification Framework – Effectiveness, Efficiency, Equity, Evidence‑base and Extent of coverage (see Box 3.1 for a high-level assessment).

Box 3.2. Assessment of the OptiMedis model

Effectiveness

Implementing the OptiMedis integrated care model across Germany is estimated to lead to an additional 146 441 life years (LYs) and 97 558 disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) by 2050

Transferring OptiMedis to the eligible population across EU27 countries is estimated to result in 9.7 LYs and 6.5 DALYs gained per 100 000 people on average per year between 2022 and 2050

Efficiency

Implementing the OptiMedis integrated care model across Germany is estimated to lead to cumulative health expenditure savings of EUR 3 470 per person by 2050

Average annual health expenditure (HE) savings as a proportion of total HE is estimated at 4%, on average, across EU‑27 countries

Equity

The Health Kiosk offers tailored health and social support, for example on healthy living and employment services, and is offered in multiple languages (e.g. Arabic). In rural areas the Health Kiosk provides low-threshold health information and navigation.

Core features of the OptiMedis model help reduce existing health inequalities, such as standardising care pathways across the whole population

The OptiMedis model may disproportionally benefit patients with a lower socio-economic status given rates of morbidity are higher in this group

Evidence‑base

A study by Schubert et al. (2016[8]) measuring the impact of the OptiMedis model of care on mortality was used to estimate gains in effectiveness when scaling-up OptiMedis across Germany. This study used strong data collection methods and controlled for confounding factors, however, the control group was not randomised.

Extent of coverage

According to data from the OptiMedis model operating in the region of Kinzigtal, approximately one‑third of eligible residents voluntarily enrol with this model of care.

Effectiveness

This section on effectiveness presents the long-term health impact of the OptiMedis model in Germany as well as countries that are members of the OECD and EU27. The analysis relied on neural networks and microsimulation modelling by the OECD. Details on the methodology, including modelling assumptions, are in Annex 3.A.

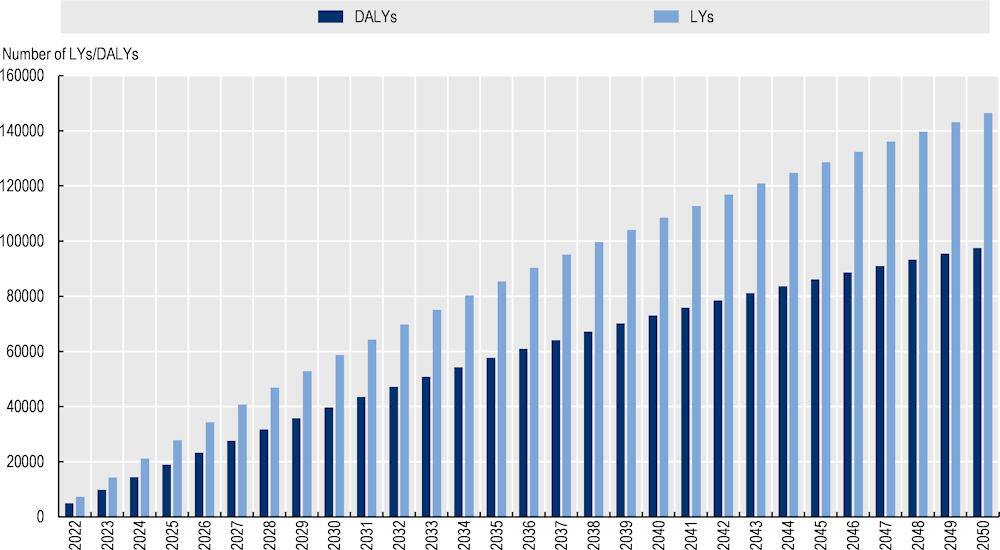

Germany

Implementing the OptiMedis integrated care model across Germany is estimated to lead to an additional 146 441 life years (LYs) and 97 558 disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) by 2050.

Figure 3.2. Cumulative number of LYs and DALYs gained, 2022‑50 – OptMedis, Germany

Source: OECD analysis based on neural networks and OECD’s SPHeP-NCD microsimulation model.

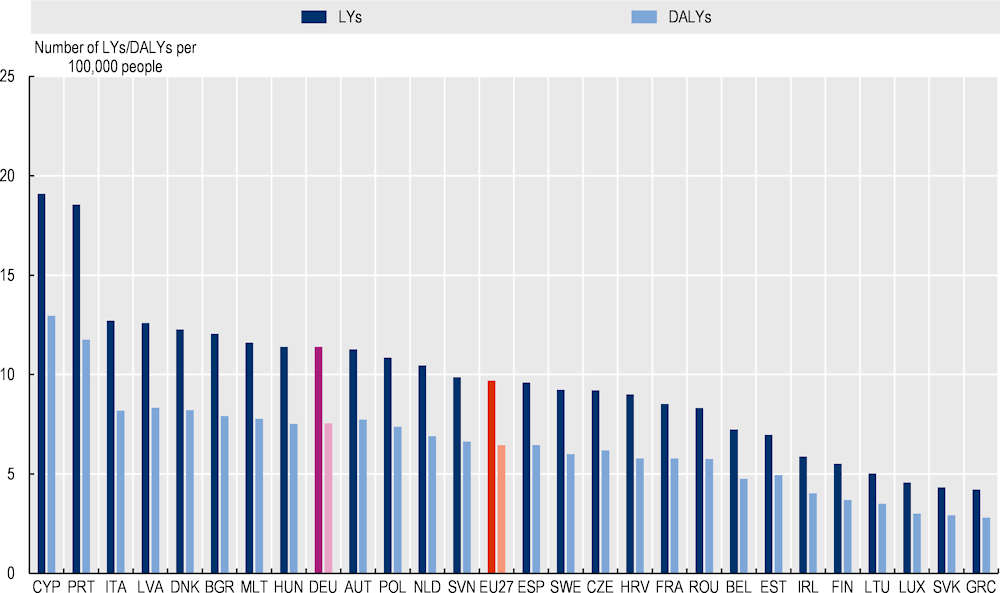

EU‑27 countries

Transferring OptiMedis to the eligible population across EU27 countries is estimated to result in 9.7 LYs and 6.5 DALYs gained per 100 000 people on average per year between 2022 and 2050 (Figure 3.3). OECD countries such as Portugal and Italy would experience the largest gain, while the effect is estimated to be lowest in Greece and the Slovak Republic.

Figure 3.3. LYs and DALYs gained per 100 000 people, 2022‑50 – OptiMedis, EU27 countries

Source: OECD analysis based on neural networks and OECD’s SPHeP-NCD microsimulation model.

Efficiency

Like “Effectiveness”, this section presents results for Germany followed by OECD and EU‑27 countries.

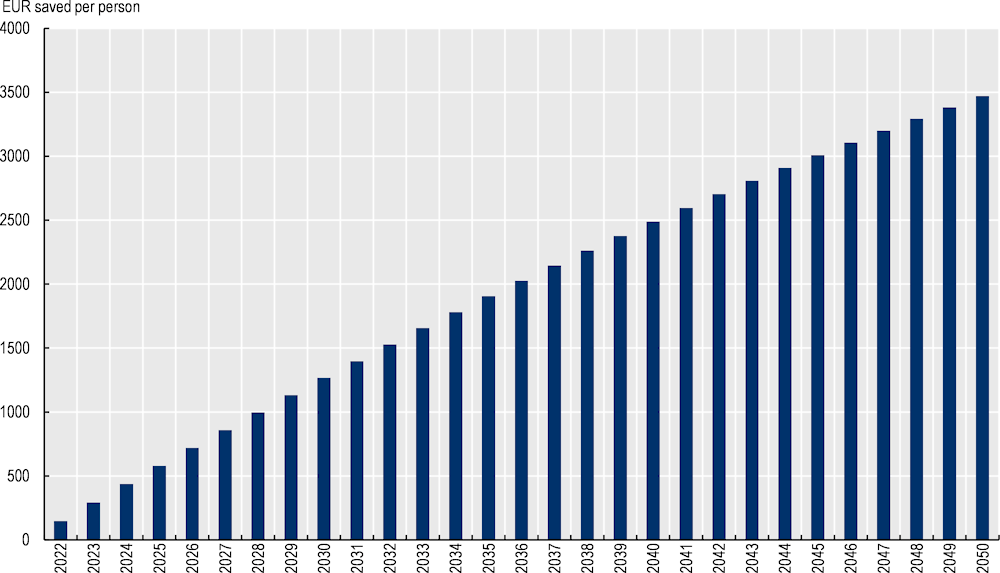

Germany

Over the modelled period, 2022‑50, the OECD-SPHeP NCD model estimates that OptiMedis would lead to cumulative health expenditure savings of EUR 3 470 per person (Figure 3.4).

Figure 3.4. Cumulative health expenditure savings per person, EUR, 2022‑50 – OptiMedis, Germany

Source: OECD analysis based on neural networks and OECD’s SPHeP-NCD microsimulation model.

EU‑27 countries

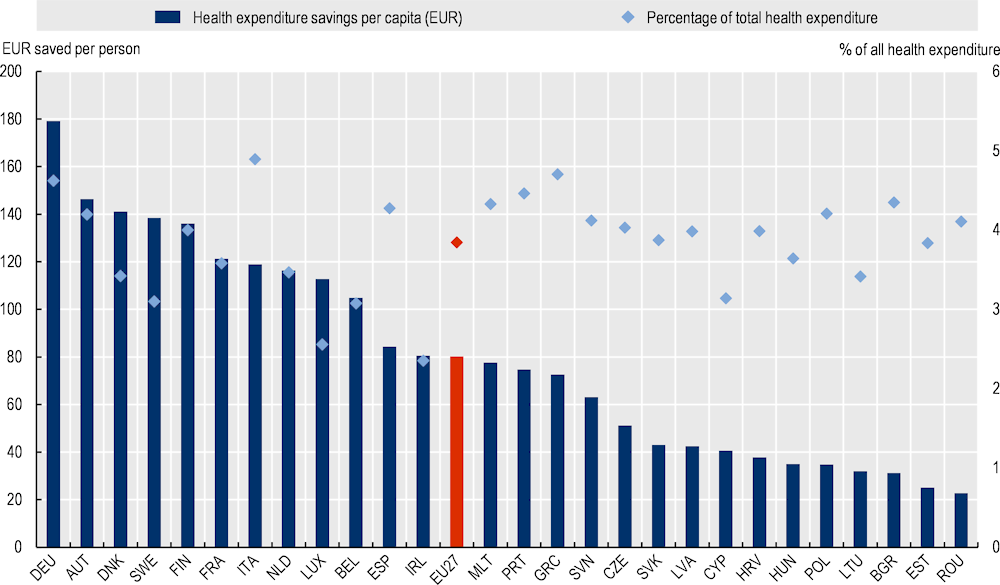

Average annual health expenditure (HE) savings as a proportion of total HE is estimated at 4%, on average, across EU‑27 countries. This translates into annual savings of EUR 80.14 for every person aged 20 years and over between 2022 and 2050, with figures ranging from EUR 23 in Romania to EUR 179 in Germany (Figure 3.5).

Figure 3.5. Health expenditure (HE) savings as a percentage of total HE and per capita (EUR), average 2022‑50 – OptiMedis, EU27 countries

Note: Per capita costs reflect the population aged 20 years and over.

Source: OECD analysis based on neural networks and OECD’s SPHeP-NCD microsimulation model.

Equity

Health Coaches, Healthcare Navigators, and the Health Kiosk are key interventions within the OptiMedis model, which aim to reduce health inequalities. The Health Kiosk was first introduced in the city of Hamburg, specifically in two boroughs where 70% of the population is comprised of migrants (compared to 13% across the whole country). The Health Kiosk caters to disadvantaged groups, such as migrants, by offering counselling services in a range of languages including Arabic, Farsi, Russian and Polish. At present, seven counsellors work within the Health Kiosk providing healthcare navigation and holistic counselling sessions related to health and social issues (e.g. nutrition, alcohol, smoking, employment and cultural integration). At present, the Health Kiosk only exists within Hamburg, however, a recent initiative aims to establish Health Kiosks in other cities, as well as in rural areas (where health topics are different, but low-threshold health information and navigation is equally important).

Core features of the OptiMedis model help reduce health inequalities. The primary objectives of the OptiMedis model are to improve patient experiences and population health, as well as reduce per capita costs. Features of the model designed to achieve these objectives also play a key role in reducing health inequalities, namely by:

Offering care tailored to individual patient needs, including those from disadvantaged backgrounds

Standardising care pathways across all patients thereby ensuring everyone receives the same service quality. Although standardised, the pathways can also be personalised to align with the patient’s need (e.g. depending on osteoporosis risk, different physiotherapy sessions or supplements might be recommended).

Offering all residents in the region access to the model, including all the interventions within it.

The OptiMedis model may disproportionally benefit patients with a lower socio-economic status given rates of morbidity are higher in this group. Socio-economic status is a key predictor of health status, including in Germany. Drawing upon OECD analyses, in Germany, those in the lowest income quintile are 1.3 times more likely to have multiple chronic conditions compared to those in the highest income quintile (OECD, 2019[9]). These results are supported by patient feedback, which found self-reported health was markedly lower for poorer populations (OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2021[3]). Integrated care models that take into account individual patient needs and promote care co‑ordination may therefore be particularly beneficial to multimorbid patients who are typically poorer. However, to benefit from OptiMedis services, vulnerable populations may be less likely to voluntarily enrol in this model of care due to, for example, lower levels of health literacy making it difficult to access and navigate the healthcare system. For example, in Germany, differences in screening rates between the highest and lowest income quintile for cervical, breast and colorectal cancer are 13, 2 and 6 percentage points, respectively (with rates higher for those in the top income quintile) (OECD, 2019[9]). Therefore, outreach models, such as Health Coaches, Healthcare Navigators or the Health Kiosk are of importance.

Evidence‑based

Estimates regarding the effectiveness and efficiency of OptiMedis were calculated using neural networks and OECD’s SPHeP-NCD microsimulation model. In-depth details of the microsimulation model are explained elsewhere: http://oecdpublichealthexplorer.org/ncd-doc/.

To estimate the health and economic gains from OptiMedis, OECD models relied on inputs from (Schubert et al., 2016[8]), which estimated the impact of OptiMedis on the mortality rate. This section assesses the quality of this study using the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies developed by the Effective Public Health Practice Project (Effective Public Health Practice Project, 1998[10]) (Table 3.1). The assessment shows that the study by (Schubert et al., 2016[8]) used strong data collection methods and adequately controlled for confounding factors.

Table 3.1. Evidence‑based assessment of OptiMedis

|

Assessment category |

Question |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Selection bias |

Are the individuals selected to participate in the study likely to be representative of the target population? |

Very likely |

|

What percentage of selected individuals agreed to participate? |

Not applicable (data collected from health insurance data) |

|

|

Selection bias score: |

Moderate |

|

|

Study design |

Indicate the study design |

Longitudinal study with non-randomised control group |

|

Was the study described as randomised? |

No |

|

|

Was the method of randomisation described? |

Not applicable |

|

|

Was the method of randomisation appropriate? |

Not applicable |

|

|

Study design score: |

Moderate |

|

|

Confounders |

Were there important differences between groups prior to the intervention? |

Unclear |

|

What percentage of potential confounders were controlled for? |

80‑100% (controlled for age, gender, Charlson Index and multimorbidity |

|

|

Confounders score: |

Strong |

|

|

Blinding |

Was the outcome assessor aware of the intervention or exposure status of participants? |

Yes |

|

Were the study participants aware of the research question? |

No |

|

|

Blinding score: |

Moderate |

|

|

Data collection methods |

Were data collection tools shown to be valid? |

Yes |

|

Were data collection tools shown to be reliable? |

Yes |

|

|

Data collection methods score: |

Strong |

|

|

Withdrawals and dropouts |

Were withdrawals and dropouts reported in terms of numbers and/or reasons per group? |

Not applicable |

|

Indicate the percentage of participants who completed the study? |

Not applicable |

|

|

Withdrawals and dropouts score: |

Not applicable |

Source: Effective Public Health Practice Project (1998[11]), “Quality assessment tool for quantitative studies”, https://www.nccmt.ca/knowledge-repositories/search/14.

Extent of coverage

According to data form the region of Kinzigtal, approximately one‑third of eligible residents are enrolled in the OptiMedis model. As outlined under the “Intervention description”, around 50% of all residents living with the region of Kinzigtal receive health insurance through one of the two sickness funds that have contracts with GK Limited (i.e. approx. 35 000 people). Of these eligible residents, around one‑third (i.e. 10 500) voluntarily enrolled in the OptiMedis integrated care model.

Data is not available to assess what proportion of eligible health professionals and providers enrol in the OptiMedis integrated care model. However, the gross number of professionals enrolled in the programme as of 2022 in the region of Kinzigtal are as follows:5

52 physicians and psychotherapists

20 clinics and nursing care centres

30 providers of nursing care and physiotherapy

50 associations

20 pharmacies

23 businesses participating in workplace health promotion programs.

Policy options to enhance performance

This section outlines policy options to enhance the performance of the OptiMedis model against each of the five best practice criteria. Policies target either OptiMedis administrators or higher level policy makers within the German healthcare system.

Enhancing effectiveness

Proactively identify high-risk patients who stand to benefit most from integrated care. Patients who are at high risk of developing complex health needs stand to benefit most from accessing preventative care offered as part of OptiMedis. Policy makers should therefore consider ways to proactively identify at-risk patients and direct them to OptiMedis prevention services. This will not only improve population health outcomes, but also economic outcomes by reducing demand for healthcare services and increasing productivity.

Enhancing efficiency

The shared savings contract is a key feature of the OptiMedis model (see “Intervention description”). For this reason, no recommendations on how to enhance efficiency are included in this report. However, it is acknowledged that any future expansion of the model may lead to efficiency savings, particularly in regard to “back of office” activities, such as data management, data analytics, development of care programmes, dashboard development, digital transformation projects, IT support and general administrative support (controlling). Further, as outlined under “Enhancing effectiveness”, proactively identifying patients who would benefit from OptiMedis prevention programs will reduce costs and boost productivity.

Enhancing equity

Expand the Health Kiosk to other eligible regions. As outlined under “Equity”, one of the key interventions to promote health equity under the OptiMedis integrated care model is the Health Kiosk. At present, the Health Kiosk only exists within the city of Hamburg, however, there are plans to expand it to other regions in the country. This proposal is highly recommended given disadvantaged groups, such as those with a migrant background, are at greater risk of developing complex health needs. Any transfers of the Health Kiosk, however, should be adapted to the needs of the local population. This requires a contextual analysis of the region covering factors such as population health needs, race/ethnicity structure, health literacy levels, utilisation patterns, structure and coverage of health services, and workforce skills. For further details on the types of contextual factors to consider before transferring an intervention, see OECD’s Guidebook on Best Practices in Public Health (OECD, 2022[12]).

Improve access to healthcare services for disadvantaged groups by promoting health literacy. Disadvantaged groups, such as those with a lower socio-economic status, are less likely to access necessary healthcare services (OECD, 2019[9]). For example, across the OECD, 74% of people in the highest income quintile have been screened for breast cancer compared to 63% among those in the lowest income quintile (OECD, 2019[9]). Although disadvantaged groups stand to benefit most the OptiMedis model, which incentivises high-quality, preventative care, they may be less likely to voluntarily enrol (however, it is noted that many people enrolled in the model of care after having visited a Health Kiosk). Programs that promote health literacy among disadvantaged groups may increase voluntarily enrolment rates (see Box 3.3 for further details).

Box 3.3. Building population health literacy

Recent analysis estimated that more than half of OECD countries with available data had low levels of HL. To address low rates of adult health literacy, OECD have outlined a four‑pronged policy approach, which align:

Strengthen the health system role: establish national strategies and framework designed to address HL

Acknowledge the importance of HL through research: measure and monitor the progress of HL interventions to better understand what policies work

Improve data infrastructure: improve international comparisons of HL as well as monitoring HL levels over time

Strengthen international collaboration: share best practice interventions to boost HL across countries.

Source: OECD (2018[13]), “Health literacy for people‑centred care: Where do OECD countries stand?”, https://doi.org/10.1787/d8494d3a-en.

Enhancing the evidence‑base

Listed below are recommendations to enhance the data collected as part of the OptiMedis programme. These suggestions are based on a review of current data collection protocols.

Collect data from two identical treatment groups, i.e. control and experimental groups, up to a small statistical error (e.g. data on health status and utilisation). Ideally this would be achieved through a randomised control trial (RCT) given such studies are considered the “gold standard” for assessing the impact of an intervention. However, RCTs are not always plausible, for example due to high costs or difficulty achieving randomised participation. In that regard, OptiMedis has co-published a qualitative comparison of several economic evaluation methods for integrated care systems, which aims to find a balance between statistical power and practical feasibility (Pimperl et al., 2014[14]);

Collect data simultaneously in several regions in order to improve data representativeness;

Collect information about how the intervention is implemented (for example, what are the inclusion criteria; action plan for each health profile) to improve modelling capabilities;

Elicit the theory of change underlying the interventions, ideally at the start of the initiative.

Enhancing extent of coverage

Consider setting targets on the proportion of patients who have enrolled in an integrated care programme. Providing integrated care centred on patient needs is widely recognised as best practice for treating patients with complex health needs. Despite this, population based integrated care models are not common across OECD countries, including Germany. To boost uptake in voluntary integrated care models, such as the OptiMedis model, policy makers could consider setting a target – i.e. the proportion of the population enrolled in an integrated care model.

Develop a multi-pronged recruitment strategy covering a range of different places, such as those outlined in Box 3.4.

Box 3.4. Policies to increase patient uptake in integrated care models

The following strategies have the potential to increase uptake in integrated care models:

Collaborate with community-based organisations who work closely with eligible patients, in particular patients who stand to benefit most (e.g. patients with complex needs)

Develop promotion material using plain, easy-to‑understand languages

Develop promotion material in a range of languages

Develop an online resource hub where patients can obtain easy-to‑understand information, such as how to enrol

Collect data on the reason why individuals choose to enrol or why individuals un-enrol, and using this information, adapt the model accordingly

Host outreach programs to providers in order to boost recruitment (a higher number of providers, will ultimately increase the number of patients enrolled)

Source: Center for Consumer Engagement in Health Innovation (2021[15]), “Person-Centered Enrollment Strategies for Integrated Care Toolkit”, https://www.healthinnovation.org/resources/toolkits/person-centered-enrollment-strategies-for-integrated-care-toolkit.

Transferability

This section explores the transferability of the OptiMedis model and is broken into three components: 1) an examination of previous transfers; 2) a transferability assessment using publicly available data; and 3) additional considerations for policy makers interested in transferring this intervention.

Previous transfers

At present, the OptiMedis model has been implemented in three different regions, however, long-term experience and evaluations only exist for the Kinzigtal region of south-west Germany. There are active discussions to expand the model of care to other regions in the country.

In an integrated care handbook outlining the OptiMedis model, it was noted “that the results from the [model] can be successfully transferred and achieved elsewhere, including in regions that are different in population structure and health service organisation” (Amelung et al., 2021[16]). The report also outlined several core features of the OptiMedis model that should be replicated in future implementations, as well as implementation facilitators – see Box 3.5.

Box 3.5. The OptiMedis model: Core features and implementation facilitators

This box outlines core features of the OptiMedis model as well as implementation facilitators.

Core features

The following features are considered to be at the core of the OptiMedis model and should therefore be replicated when transferred to another region/country:

Consider which body would take on the role of the “integrator” – i.e. the role of GK Limited, an integrated care management company. The integrator should be regionally based, owned partly by local providers, familiar with local services and plans.

The integrator needs to be supported by an organisation who can invest in the model of care, engage in high-level negotiations, provide advanced health data analytics and whose goal is to pursue long-term goals (i.e. the role of OptiMedis).

Considerable investment at the beginning to set up organisational structures, integrated stakeholders and design interventions. Funding is needed for at least three years given the delay in realising health benefits.

Ensure there is motivation to implement interventions that aim to improve population health.

The population size covered by the model of care should be no larger than 100 000 per integrator unit to ensure networking among providers, local solutions, and the exchange of ideas among stakeholders.

A comprehensive information-technology package and competencies regarding advanced health data analytics.

A culture of both co‑operation and competition through transparency and benchmarking.

A balanced payment system that supports the triple aim approach and that is incorporated into the shared savings contract.

An innovative and friendly culture to maximise relationships with stakeholders.

Long-term contracts (around 10 years) with purchasers to ensure stability in regards to planning healthcare services and to incentivise long-term health promotion strategies.

Implementation facilitators

In addition to the model’s core features, there are a few factors that will facilitate the implementation of this intervention, namely:

A stable physician network

Purchasers willing to share long-term savings

A robust method to monitor costs and quality over time.

Source: Amelung et al. (2017[5]), “Handbook Integrated Care” and Amelung et al. (2021[16]), “Handbook Integrated Care”, https://www.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-69262-9.

Finally, although regions outside Germany have not implemented the OptiMedis model, it should be noted that the underlying features that support the model exist across most OECD countries (e.g. the chronic care model, preventative care, case management, multidisciplinary care teams, electronic patient data sharing, and personalised care plans). Further, there are active discussions in regions of France (Strasbourg) and Belgium (Germany speaking community) to transfer this model of care as part of the EU Joint Action on implementation of digitally enabled person-centred care (JADECARE).

Transferability assessment

The following section outlines the methodological framework to assess transferability and results from the assessment.

Methodological framework

A few indicators to assess the transferability of the OptiMedis model were identified (see Table 14.4). Indicators were drawn from international databases and surveys to maximise coverage across OECD and non-OECD European countries. Please note, the assessment is intentionally high level given the availability of public data covering OECD and non-OECD European countries.

Table 3.2. Indicators to assess transferability – OptiMedis model

|

Indicator |

Reasoning |

Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

|

Sector context (healthcare system – all levels) |

||

|

Proportion of GPs who work in single‑handed practices |

The intervention is more transferable in countries where GPs feel comfortable working with other health professionals. This indicator is a proxy to measure the willingness of GPs to work in co‑ordinated teams. |

Low = more transferable High = less transferable |

|

Proportion of physicians in primary care facilities using electronic health records |

EHRs improve the ability of health professionals to provide integrated patient-centred care. Therefore, the intervention is more transferable in countries that utilise EHRs in primary care facilities. |

🡹 = more transferable |

|

Proportion of hospitals using electronic patient records for inpatients |

As above |

🡹 = more transferable |

|

The extent of task shifting between physicians and nurses in primary care |

This intervention promotes integrated care provided by multidisciplinary teams. Therefore, the intervention is more transferable in countries where physicians feel comfortable shifting tasks to nurses. |

The more “extensive” the more transferable |

|

The use of financial incentives to promote co‑ordination in primary care |

The intervention is more transferable to countries with financial incentives that promote co‑ordination of care across health professionals. |

Bundled payments or co‑ordinated payment = more transferable |

|

Economic context |

||

|

Primary healthcare expenditure as a percentage of current health expenditure |

The intervention places a stronger emphasis on primary care, therefore, it is likely to be more successful in countries that allocate a higher proportion of health spending to primary care |

🡹 = more transferable |

|

Prevention expenditure as a percentage of current health expenditure |

The intervention places a stronger emphasis on prevention, therefore, it is likely to be more successful in countries that allocate a higher proportion of health spending on prevention |

🡹 = more transferable |

Source: WHO (2018[17]), “Primary Healthcare (PHC) Expenditure as percentage of Current Health Expenditure (CHE)”, https://apps.who.int/nha/database; Oderkirk (2017[18]), “Readiness of electronic health record systems to contribute to national health information and research”, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9e296bf3-en; Schäfer et al. (2019[19]), “Are people’s health care needs better met when primary care is strong? A synthesis of the results of the QUALICOPC study in 34 countries”, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1463423619000434; Maier and Aiken (2016[20]), “Task shifting from physicians to nurses in primary care in 39 countries: a cross-country comparative study”, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckw098; OECD (2020[4]), Realising the Potential of Primary Health Care, https://doi.org/10.1787/a92adee4-en; OECD (2016[21]), “Health Systems Characteristics Survey”, https://qdd.oecd.org/subject.aspx?Subject=hsc; European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (2021[22]), “The Health Systems and Policy Monitor”, https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int/countries/overview.

Results

Results from the analysis are outlined in Table 3.3 with a summary provided below:

The proportion of countries whose GPs work in single‑handed practices is lower among OECD and EU27 countries when compared to Germany – i.e. the proportion in Germany is “high” (>50%) compared to two‑thirds of remaining countries with available data where the proportion is either “low” (<27%) or “medium” (28‑50%). Similarly, levels of task-shifting between doctors and nurses is non-existent in Germany. Both results indicate relative to Germany, GPs in remaining OECD and EU27 countries are more likely to undertaken their work as part of a multidisciplinary team.

Rates of electronic healthcare record (EHR) use, both in primary and secondary care, is similar in Germany when compared to the OECD and EU27 average. This result masks differences at the individual country level, for example, in Nordic countries such as Denmark, Iceland and Finland, EHR use is at 100% across the healthcare system compared to around a third or less in countries such as Japan and Poland. Countries where EHR use is relatively low may experience barriers to providing integrated care across given difficulties in sharing patient data.

Financially, as a proportion of total health expenditure, Germany spends more on primary care and prevention than the average OECD/EU27 country. Germany also has financial incentives for delivering co‑ordinated care, while many OECD/EUR27 countries do not.

Table 3.3. Transferability assessment by country (OECD and non-OECD European countries) – OptiMedis model

A darker shade indicates that the OptiMedis integrated care model is more suitable for transferral in that particular country

|

Country |

% of single‑handed GP practices |

% of primary care physician offices using EHRs* |

% hospitals using EHRs for inpatients |

Extent of task shifting |

Mechanism to pay primary care professionals |

Primary Healthcare expenditure as % CHE |

% CHE** on prevention (2018 or latest year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Germany |

High |

80 |

77 |

None |

Co‑ordinated payment |

48 |

3.20 |

|

Australia |

Low |

96 |

20 |

Extensive |

Bundled |

37 |

1.93 |

|

Austria |

High |

80 |

99 |

None |

Co‑ordinated payment |

37 |

2.11 |

|

Belgium |

High |

n/a |

n/a |

Limited |

Bundled |

40 |

1.65 |

|

Bulgaria |

High |

n/a |

n/a |

None |

Bundled |

47 |

2.83 |

|

Canada |

Low |

77 |

69 |

Extensive |

Bundled |

48 |

5.96 |

|

Chile |

n/a |

65 |

69 |

n/a |

No incentive |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Colombia |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

No incentive |

n/a |

2.05 |

|

Costa Rica |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

No incentive |

33 |

0.60 |

|

Croatia |

n/a |

03 |

n/a |

Limited |

No incentive |

38 |

3.16 |

|

Cyprus |

Low |

n/a |

n/a |

Limited |

No incentive |

41 |

1.26 |

|

Czech Republic |

High |

n/a |

100 |

None |

No incentive |

33 |

2.65 |

|

Denmark |

Medium |

100 |

100 |

Limited |

Co‑ordinated payment |

38 |

2.44 |

|

Estonia |

High |

99 |

100 |

Limited |

No incentive |

44 |

3.30 |

|

Finland |

Medium |

100 |

100 |

Extensive |

No incentive |

46 |

3.98 |

|

France |

n/a |

80 |

60 |

None |

Bundled |

43 |

1.80 |

|

Greece |

High |

100 |

50 |

None |

No incentive |

45 |

1.27 |

|

Hungary |

High |

n/a |

n/a |

Limited |

No incentive |

40 |

3.04 |

|

Iceland |

Low |

100 |

100 |

Limited |

Co‑ordinated payment |

35 |

2.68 |

|

Ireland |

Low |

95 |

35 |

Extensive |

No incentive |

47 |

2.60 |

|

Israel |

n/a |

100 |

100 |

n/a |

Co‑ordinated payment |

n/a |

0.37 |

|

Italy |

Medium |

n/a |

n/a |

Limited |

Bundled |

n/a |

4.41 |

|

Japan |

n/a |

36 |

34 |

n/a |

No incentive |

52 |

2.86 |

|

Korea |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

No incentive |

57 |

3.48 |

|

Latvia |

High |

70 |

90 |

Limited |

Bundled |

39 |

2.58 |

|

Lithuania |

Medium |

n/a |

n/a |

Limited |

No incentive |

48 |

2.17 |

|

Luxembourg |

Medium |

n/a |

n/a |

None |

No incentive |

38 |

2.18 |

|

Malta |

Medium |

n/a |

n/a |

Limited |

No incentive |

62 |

1.30 |

|

Mexico |

n/a |

30 |

49 |

n/a |

Co‑ordinated payment |

44 |

2.92 |

|

Netherlands |

Medium |

n/a |

n/a |

Extensive |

Bundled |

32 |

3.26 |

|

New Zealand |

Low |

95 |

100 |

Extensive |

No incentive |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Norway |

Low |

100 |

100 |

None |

No incentive |

39 |

2.45 |

|

Poland |

Medium |

30 |

10 |

None |

No incentive |

47 |

2.28 |

|

Portugal |

Low |

n/a |

n/a |

Limited |

No incentive |

58 |

1.68 |

|

Romania |

Medium |

n/a |

n/a |

None |

No incentive |

35 |

1.42 |

|

Slovak Republic |

High |

89 |

100 |

None |

No incentive |

n/a |

0.77 |

|

Slovenia |

High |

n/a |

n/a |

Limited |

No incentive |

43 |

3.13 |

|

Spain |

Low |

99 |

80 |

Limited |

No incentive |

39 |

2.13 |

|

Sweden |

Low |

100 |

100 |

Limited |

Co‑ordinated payment |

n/a |

3.27 |

|

Switzerland |

Medium |

40 |

100 |

None |

No incentive |

40 |

2.63 |

|

Türkiye |

Low |

n/a |

n/a |

None |

No incentive |

n/a |

n/a |

|

United Kingdom |

Low |

99 |

100 |

Extensive |

No incentive |

53 |

5.08 |

|

United States |

n/a |

83 |

76 |

Extensive |

No incentive |

n/a |

2.91 |

Note: n/a = not data available; *EHR = electronic health record; **CHE = current health expenditure.

Source: See Table 3.2.

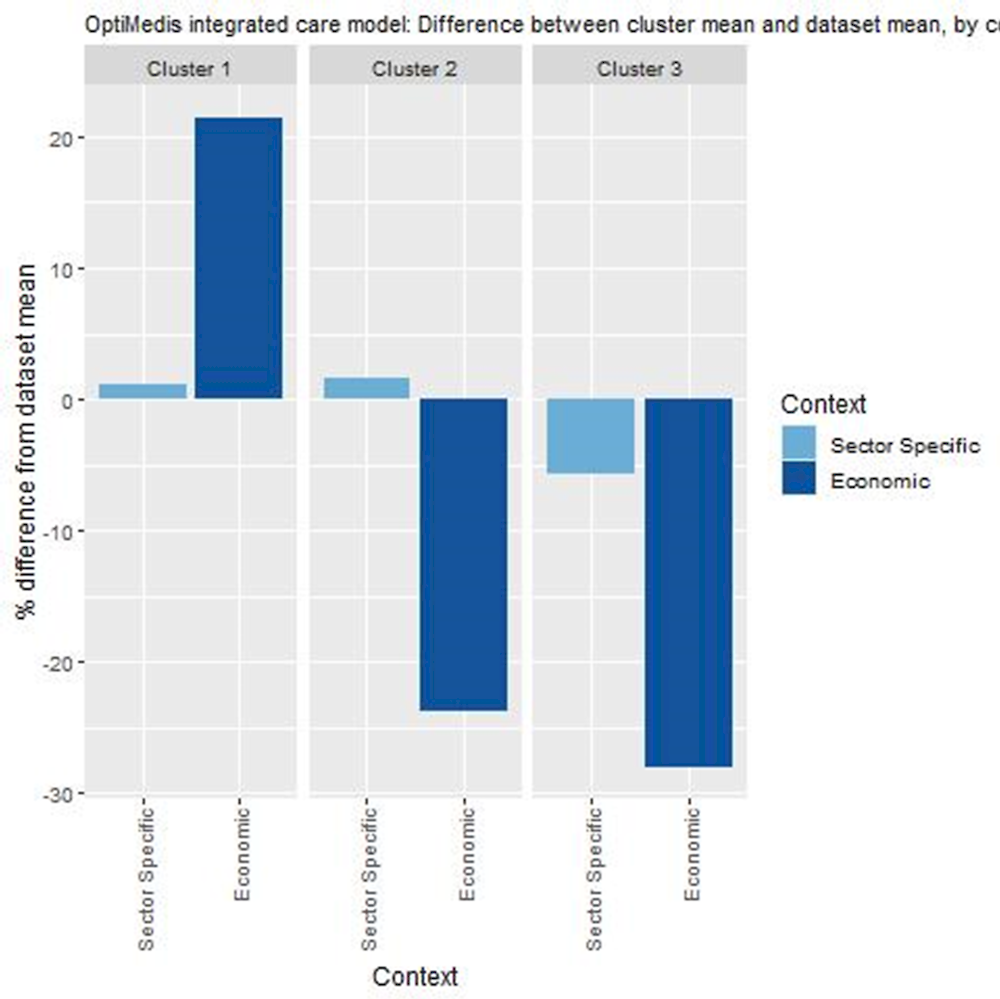

To help consolidate findings from the transferability assessment above, countries have been clustered into one of three groups, based on indicators reported in Table 14.4. Countries in clusters with more positive values have the greatest transfer potential. For further details on the methodological approach used, please refer to Annex A.

Key findings from each of the clusters are below with further details in Figure 3.6 and Table 3.4:

Countries in cluster one typically have healthcare systems that promote integrated care. Further, these countries spend relatively high amounts on primary care and prevention. This cluster includes Germany, where OptiMedis currently operates in certain regions.

Countries in cluster two also have healthcare systems that promote integrated care. However, they spend relatively less on primary care and prevention, which may hinder long-term sustainability of integrated care models focused on avoiding or delaying complex health needs.

Countries in cluster three should consider whether their healthcare systems are ready to implement population based integrated care models, and also whether such a model is affordable in the long-term.

Figure 3.6. Transferability assessment using clustering – OptiMedis model

Note: Bar charts show percentage difference between cluster mean and dataset mean, for each indicator.

Table 3.4. Countries by cluster – OptiMedis

|

Cluster 1 |

Cluster 2 |

Cluster 3 |

|---|---|---|

|

Bulgaria Canada Croatia Czech Republic Estonia Finland Germany Hungary Ireland Italy Japan Lithuania Luxembourg Mexico Netherlands Poland Slovenia Switzerland United Kingdom United States |

Australia Austria Belgium Cyprus Denmark France Iceland Latvia Norway Spain Sweden |

Greece Israel Malta New Zealand Portugal Romania Slovak Republic |

Note: The following countries are not in the table below due to high levels of missing data: Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Korea and Türkiye.

New indicators to assess transferability

Data from publicly available datasets alone is not ideal to assess the transferability of public health interventions. Box 3.6 outlines several new indicators, or factors, policy makers could consider before transferring the OptiMedis integrated care model.

Box 3.6. New indicators, or factors, to consider when assessing transferability – OptiMedis model

In addition to the indicators within the transferability assessment, policy makers are encouraged to collect information for the following information points:

Population context

What is the population’s attitude towards receiving care from health professionals who are not doctors?

What is the level of health literacy among patients? (i.e. are patients likely to engage in shared decision-making?)

Is there a demand among the population to alter the way care is delivered?

Sector context (healthcare system – all levels)

What integrated care models currently exist?

Does the clinical information system support: a) sharing of patient data across health professionals? b) Sharing of patient data across healthcare facilities?

What share of primary care physicians use electronic health records? (OECD, 2021[23])

What proportion of the population who access healthcare have experience good care co‑ordination? (OECD, 2021[23])

Do health provider reimbursement schemes support co‑ordinated care?

Is there a stable network of physicians operating in the region?

Are there purchasers operating in the region who are willing to share long-term savings?

Is there capacity as well as the capability to monitor healthcare costs and quality over time?

What is the level of patient data operability among healthcare providers?

Do the healthcare system governance structures support the delivery of integrated care?

Political context

Has the intervention received political support from key policy makers? (E.g. a national strategy to address rising rates of chronicity or policies that promote care co‑ordination)

Has the intervention received commitment from key decision-makers?

Economic context

What is the cost of implementing and operating the intervention in the target setting and to whom?

Conclusion and next steps

Policy changes in Germany to promote care co‑ordination led to the implementation of the OptiMedis model. Germany’s healthcare system is complex due to the separation of legislative, planning and regulatory power across different sectors. In an effort to improve care co‑ordination, the government implemented several policies including the 2004 Social Health Insurance Modernisation Act. Following on from this Act, OptiMedis implemented its regionally based population integrated care model in certain regions in Germany.

The OptiMedis model offers patients co‑ordinated care across all health sectors with a focus on prevention. Insurees of any sickness fund that has a contract with OptiMedis can voluntarily enrol in the integrated care model. Those who enrol have access to all healthcare services plus additional interventions that promote care co‑ordination and prevention. There is a shared savings contract exists between sickness funds and OptiMedis in order to incentivise high quality care. The difference is calculated by subtracting the money spent on patients from the amount sickness funds receive from the central payment authority.

OptiMedis leads to an improvement in health outcomes as well as cost savings based on modelling estimates. For example, OECD countries, on average, could expect to gain 9.7 LY and 6.5 DALYs per 100 000 people per year between years 2022 and 2050 by operating the OptiMedis model of care. From an efficiency point of view, OptiMedis has the potential to reduce health expenditure by an amount equivalent to 4% of their total spending on health.

To successfully transfer this model of care, OptiMedis administrators have outlined several core features and implementation facilitators. These include, but are not limited to, ensuring the population size is no longer than 100 000, fostering a culture of both co‑operation and competition, and developing a comprehensive information-technology package that has the capability of undertaking advanced data analytics.

Box 3.7 outlines next steps for policy makers and funding agencies in regard to the OptiMedis model.

Box 3.7. Next steps for policy makers and funding agencies – OptiMedis

Next steps for policy makers and funding agencies to enhance the OptiMedis model are listed below:

Consider policy options in this case study in order to enhance the overall performance of the OptiMedis model

Share key findings from the case study with stakeholders to promote population-based integrated care models

In particular, share tips on how to best transfer the intervention based on the model’s core feature and implementation facilitators, as outlined in this case study.

References

[5] Amelung, V. et al. (2017), Handbook Integrated Care, Springer International Publishing, Cham, Swizerland.

[16] Amelung, V. et al. (eds.) (2021), Handbook Integrated Care, Springer International Publishing, Cham, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-69262-9.

[1] Blümel, M. et al. (2020), Germany: Health system review, European Observatory of Health Systems and Polciies, https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int/publications/i/germany-health-system-review-2020.

[15] Center for Consumer Engagement in Health Innovation (2021), Person-Centered Enrollment Strategies for Integrated Care Toolkit, https://www.healthinnovation.org/resources/toolkits/person-centered-enrollment-strategies-for-integrated-care-toolkit.

[10] Effective Public Health Practice Project (1998), Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies, https://www.ephpp.ca/quality-assessment-tool-for-quantitative-studies/ (accessed on 28 July 2021).

[11] Effective Public Health Pratice Project (1998), Quality assessment tool for quantitative studies, https://www.nccmt.ca/knowledge-repositories/search/14.

[22] European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (2021), The Health Systems and Policy Monitor, https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int/countries/overview (accessed on 9 June 2021).

[20] Maier, C. and L. Aiken (2016), “Task shifting from physicians to nurses in primary care in 39 countries: a cross-country comparative study”, The European Journal of Public Health, Vol. 26/6, pp. 927-934, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckw098.

[18] Oderkirk, J. (2017), “Readiness of electronic health record systems to contribute to national health information and research”, OECD Health Working Papers, No. 99, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9e296bf3-en.

[12] OECD (2022), Guidebook on Best Practices in Public Health, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/4f4913dd-en.

[23] OECD (2021), Health for the People, by the People: Building People-centred Health Systems, OECD Health Policy Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/c259e79a-en.

[2] OECD (2020), Current expenditure on health (all functions and providers) as a % of GDP.

[4] OECD (2020), Realising the Potential of Primary Health Care, OECD Health Policy Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/a92adee4-en.

[9] OECD (2019), Health for Everyone?: Social Inequalities in Health and Health Systems, OECD Health Policy Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/3c8385d0-en.

[13] OECD (2018), “Health literacy for people-centred care: Where do OECD countries stand?”, OECD Health Working Papers, No. 107, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/d8494d3a-en.

[21] OECD (2016), Health Systems Characteristics Survey 2016, https://qdd.oecd.org/subject.aspx?Subject=hsc.

[3] OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (2021), Germany: Country Health Profile 2021, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/e4c56532-en.

[14] Pimperl, A. et al. (2014), “Ökonomische Erfolgsmessung von integrierten Versorgungsnetzen – Gütekriterien, Herausforderungen, Best-Practice-Modell”, Das Gesundheitswesen, Vol. 77/12, pp. e184-e193, https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0034-1381988.

[19] Schäfer, W. et al. (2019), “Are people’s health care needs better met when primary care is strong? A synthesis of the results of the QUALICOPC study in 34 countries”, Primary Health Care Research & Development, Vol. 20, https://doi.org/10.1017/s1463423619000434.

[8] Schubert, I. et al. (2016), “Evaluation der populationsbezogenen ‚Integrierten Versorgung Gesundes Kinzigtal‘ (IVGK). Ergebnisse zur Versorgungsqualität auf der Basis von Routinedaten”, Zeitschrift für Evidenz, Fortbildung und Qualität im Gesundheitswesen, Vol. 117, pp. 27-37, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.zefq.2016.06.003.

[7] The Commonwealth Fund (2019), 2019 Commonwealth Fund International Health Policy Survey of Primary Care Physicians, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/2019-12/PDF_2019_intl_hlt_policy_survey_primary_care_phys_CHARTPACK_12-10-2019.pdf.

[6] The King’s Fund (2022), Gesundes Kinzigtal, Germany, https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/population-health-systems/gesundes-kinzigtal-germany.

[17] WHO (2018), Primary Health Care (PHC) Expenditure as % Current Health Expenditure (CHE).

Annex 3.A. OptiMedis: Modelling assumptions and methodology

The table below outlines the assumptions and methodology used to model the effectiveness and efficiency of the OptiMedis integrated care model. The assumptions are broken down as follows: target group, exposure among the target group, effectiveness, timeframe, and costs.

Annex Table 3.A.1. Modelling assumptions

|

Model parameters |

OptiMedis model inputs |

|---|---|

|

Target group |

Everyone aged 20 years and over with a non-communicable disease and/or injury (Schubert et al., 2016[8]) |

|

Exposure |

The model assumes the whole target group are exposed to OptiMedis. It should be noted, however, that in the German region of Kinzigtal, only a third of those with access to OptiMedis voluntary enrolled. |

|

Effectiveness |

The model applied a hazard ratio of 0.946 (Schubert et al., 2016[8]). |

|

Timeframe |

Years 2022‑50 |

|

Costs |

No additional costs. |

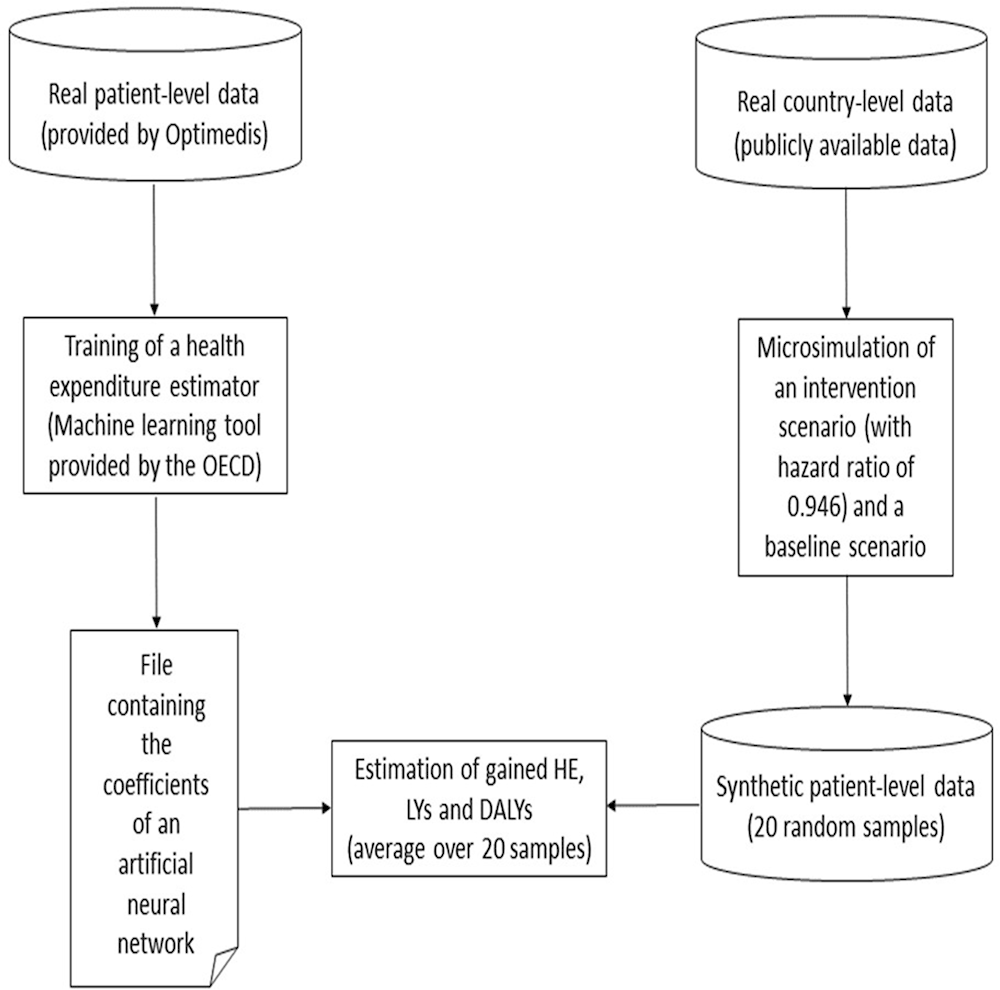

The methodology can be split into two logical and chronological parts. First, by means of a machine learning tool provided by the OECD Secretariat, OptiMedis has trained a neural network from its own real patient-level data and sent back the output file to the OECD Secretariat. This neural network has been designed to estimate the health expenditure from patients’ characteristics (age, sex, diagnoses). Then, for each target country, the OECD Secretariat has simulated a set of 20 random synthetic patient-level data and computed the related health expenditure (HE), LYs and DALYs by means of the neural network and its own microsimulation model. The resulting HE, LYs and DALYs have been averaged over the 20 samples in order to get an accurate an estimate of these quantities.

Annex Figure 3.A.1. Modelling methodology

Notes

← 1. Figures are from 2019 to avoid increases in spending due to COVID‑19.

← 2. As above.

← 3. Expected costs are calculated according to the risk-adjusted funds received by the sickness funds to care for their contracted insurees from the central authority (Gesundheitsfonds).

← 4. In the German region of Kinzigtal, Gesundes Kinzigtal (of which OptiMedis is a 33% shareholder) invested EUR 1 million to design an e‑patient record. The record is compatible with IT systems in each practice, further patient data can be shared across practices. In GWMK, OptiMedis are in the process of implementing a large digital toolbox capable of sharing data between providers, patients and caregivers (i.e. ADLIFE Project).

← 5. Note, figures frequently change.