This chapter covers Personalised Action Plans (PAPs) in Andalusia, Spain. The case study includes an assessment of PAPs against the five best practice criteria, policy options to enhance performance and an assessment of its transferability to other OECD and EU27 countries.

Integrating Care to Prevent and Manage Chronic Diseases

14. Personalised Action Plans, Andalusia, Spain

Abstract

Personalised Action Plans (PAP): Case study overview

Description: In 2016, Andalusia, Spain, introduced Personalised Action Plans (PAPs) for people living with one or more chronic diseases. The PAP programme outlines a formal process whereby practitioners and patients collaborate to create a longitudinal treatment plan. It has many objectives such as improving patient experience as well as reducing unnecessary use of healthcare services.

Best practice assessment:

OECD best practice assessment of the PAP programme

|

Criteria |

Assessment |

|---|---|

|

Effectiveness |

Patient experiences have improved since the introduction of the PAP programme. Research from the wider literature on personalised care plans show they lead to small improvements in objective health outcomes. |

|

Efficiency |

There is an association between the PAP programme and a reduction in healthcare utilisation – i.e. by 23.5%. |

|

Equity |

The design of the PAP programme takes into account the needs of individual patients, including those from disadvantaged groups, and standardises care across the region. PAP has the potential to disproportionately benefit lower socio-economic groups as they experience higher morbidity rates. |

|

Evidence‑base |

A cohort pre/post study design was used to measure the impact of the PAP programme in terms of patient experiences and healthcare utilisation. Although there are many strengths to this study design, the validity of results are weakened by the lack of a control group. |

|

Extent of coverage |

At present, 200 700 people are eligible for the PAP programme in Andalusia, Spain |

Enhancement options: The PAP programme is well designed, however, to enhance effectiveness and efficiency, policies to improve health professional satisfaction may be necessary. To enhance equity, the first step is to understand whether inequalities in terms of access, outcomes or experiences exist. To enhance the evidence‑base, existing data on patient and professional experiences should be complemented by the impact of the PAP programme on objective health outcomes. And finally, to enhance the extent of coverage, policy makers could consider widening eligibility to other chronic conditions such as diabetes and asthma.

Transferability: Personalised care plans similar to the PAP programme exist across many OECD countries and have so for several years. Despite their popularity, data continues to show patients do not feel adequately supported by their healthcare team. This finding indicates that in theory, personalised care plans are transferable to different regions, yet in practice are poorly implemented. A transferability assessment using quantitative indicators found health systems that promote multidisciplinary care and are digitally advanced are better equipped to implement the PAP programme.

Conclusion: The PAP programme has shown it can improve patient experiences and reduce utilisation, however, its impact on health outcomes and inequalities is not yet clear. To enhance the overall impact of PAP, policy makers should consider policy options outlined in this case study.

Intervention description

This section briefly summarises the epidemiological changes among OECD/EU27 countries, which has seen the rise of complex healthcare needs. This is followed by a description of Andalusia’s, Spain, Personalised Action Plan intervention to address this growing health issue.

The rise of complex chronic health needs

A person living with complex chronic health needs includes those who have one or multiple chronic health conditions such as asthma, diabetes and hypertension. Those with complex chronic health needs often require care from multiple health professionals and are therefore heavy users of healthcare services. For example, in the United States, 71% of healthcare spending comes from patients with at least two chronic conditions, with this figure increasing to 86% among those with at least one chronic condition (Chapel et al., 2017[1]).

The number of people living with complex chronic health needs has been increasing due to ageing populations and changes in lifestyle behaviours, which encourage unhealthy eating and low levels of physical activity. As of 2020, over a third (35.1%) of all adults in EU27 countries reported having a long-standing illness, which represents an increase from 31% in 2011. Over this period (2011‑20), Spain recorded the largest proportional increase at 77% (i.e. from 21.1% to 37.3%), which was markedly higher than the EU27 average of +10% (Eurostat, 2022[2]).

Personalised Action Plans in Andalusia, Spain

In response to rising rates of people with complex chronic health needs, in 2012 the Spanish region of Andalusia introduced the “Comprehensive Healthcare Plan for Patients with Chronic Diseases” (Cosano et al., 2019[3]). A key development that stemmed from this Plan was the introduction of Personalised Action Plans (PAPs) in 2016. PAPs, often referred to as personalised care plans in the literature, are “a formal process whereby practitioners and patients collaborate to create a longitudinal treatment plan” (OECD, 2020[4]).

Details on those eligible for a PAP are summarised in Box 14.1.

Box 14.1. Identifying patients eligible for a PAP

PAPs were originally available to people of any age living in Andalusia, Spain, with one or more chronic diseases. However, since January 2021, the programme has focused on patients living with heart failure or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Together these two diseases account for 200 700 people in the region. Patients with either of these diseases were identified as a priority given they heavy users of the healthcare system.

The region’s Population Health Data Base identifies eligible patients. The data base includes unique individual level data outlining the patient’s disease history and healthcare system use and is updated every three months. A GP-nurse or case management nurse within the patient’s reference team at the hospital are responsible for contacting eligible patients.

Source: Information provided by administrators of the PAP programme.

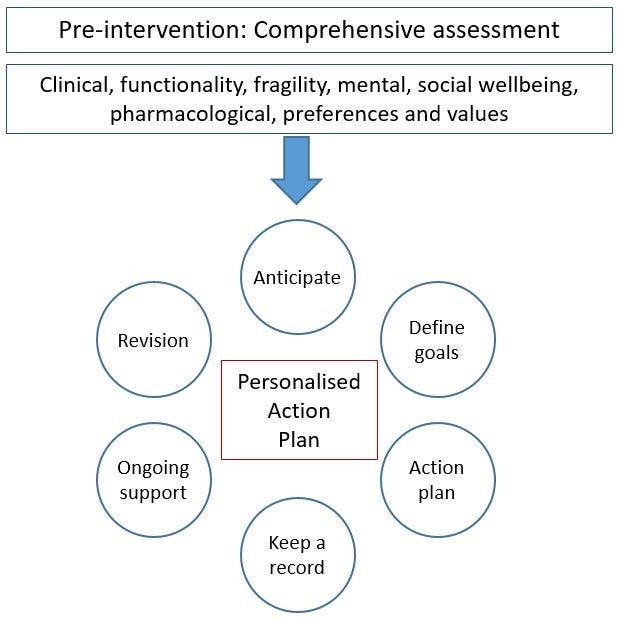

Patients eligible for a PAP, or their caregiver, receive a pre‑intervention comprehensive assessment with a multidisciplinary care team to ensure all perspectives are taken into account. The assessment covers the patient’s clinical, functional (frailty), social and mental ability, as well as their ability to self-manage their condition. It also includes a discussion of the patient’s preferences and values. Following the pre‑intervention assessment, patients receive a PAP, which is developed using the following six steps (see Figure 14.1) (Servicio Andaluz de Salud, 2016[5]):

Anticipate and outline patient health problems: this requires the patient’s multidisciplinary care team to discuss their clinical judgement of the patient and develop a streamlined care plan.

Define goals and objectives with the patient or caregiver: goals and objectives should take into account patient preferences as well as clinical guidelines, while being aware that guidelines may not be appropriate for multimorbid patients (as they are often developed for singular diseases).

Agree on an action plan with the patient: the plan must meet patient preferences but also be clinically feasible, maximise benefits while minimising harm, and ensure, to the extent possible, the patient can self-manage their condition.

Keep a record: a printed or electronic record of the agreed action plan is necessary. The PAP must be accessible to the patient, or caregiver, as well as the multidisciplinary care team.

Provide ongoing support for the patients: the patient, or caregiver, and the care team schedule follow-up meetings either face‑to-face, by phone or online. The purpose of these follow-up meetings is to ensure that what was agreed in the PAP is being followed.

Revise the PAP: during the follow-up meetings, the patient, or caregiver, and care team jointly review progress and plan next steps.

Figure 14.1. PAP overview

Source: Adapted from Servicio Andaluz de Salud (2016[5]), “Plan de acción personalizado en pacientes pluripatológicos o con necesidades complejas de salud: recomendaciones para su elaboración”, https://www.opimec.org/media/files/Plan_Accion_Personalizado_Edicion_2016.pdf.

The PAP programme has multiple objectives aimed at improving either processes or health outcomes:

Process objectives:

Adapt the use of health resources and services, including the optimisation of pharmaceutical spending and health products

Involve patients/families in decision-making and guide self-care.

Health outcome objectives:

Reduce adverse events such as falls, pressure ulcers, drug-related problems

Reduce preventable admissions, readmissions, hospitalisations and inappropriate use of emergency services

Prevent malnutrition, wounds, incontinence, infection control, and control chronic pathologies, delay dependence, and monitor cognitive deterioration

Improve quality of life and self-perception of health.

OECD Best Practices Framework assessment

This section analyses the PAP programme against the five criteria within OECD’s Best Practice Identification Framework – Effectiveness, Efficiency, Equity, Evidence‑base and Extent of coverage (see Box 14.2 below for a high-level assessment). Further details on the OECD Framework can be found in Annex A.

Box 14.2. Assessment of Personalised Action Plans in Andalusia, Spain

Effectiveness

Since the introduction of the PAP programme, there has been a statistically significant improvement in patient experiences

Findings from the wider literature show personalised care plans improve objective health outcomes such as levels of depression and blood pressure

Efficiency

There is an association between the PAP programme and a reduction in the rate at which healthcare utilisation increases

By reducing healthcare utilisation, the PAP programme is estimated to reduce costs by 23.5%

Equity

The design of the PAP programme takes into account the needs of individual patients, including those from disadvantaged groups, and standardises care across the population

The impact of the programme on health inequalities is not available. However, it has the potential to reduce inequalities given the probability of living with one or more chronic conditions is higher among lower socio-economic groups.

Evidence‑base

A cohort pre/post study design using data collected from a treatment group only was used to evaluate the effectiveness and efficiency of the PAP programme. This study design is strong in some areas, however, the overall study validity is weakened by the lack of a control group.

Extent of coverage

At present, 200 700 people are eligible for the PAP programme in Andalusia, Spain. The proportion of those who “sign up” to the programme is unclear.

Effectiveness

A 2020 evaluation estimated the impact of the PAP programme from both a patient and health system perspective (Rodriguez-Blazquez et al., 2020[6]). The former relied on changes in the PACIC (Patient Assessment of Care for Chronic Conditions) survey scores measured both pre‑ and post-implementation, while the latter, using the same methodology, relied on the ACIC (Assessment of Chronic Illness Care) survey. See Box 14.3 for further details on each of these surveys.

Box 14.3. PACIC and ACIC surveys

A description of measures used to evaluate the impact of the PAP programme are summarised below:

PACIC survey aims to measure the change in the quality of care provided to chronic care patients. The PACIC survey used to measure the PAP programme involved a 26‑item questionnaire covering five dimensions – the 5As model: assess, advise, agree, assist, and arrange. For each dimension, patients rate their experience from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). In addition to each dimension, an overall summary was calculated.

ACIC survey assesses the strengths and weaknesses of the care delivered to patients with chronic diseases from the perspective of the health system. The ACIC survey used to evaluate the PAP programme covered seven areas: delivery system organisation, community linkages, self-management support, decision support, delivery system design, clinical information systems, and integration of model components

Source: Rodriguez-Blazquez et al. (2020[6]), “Assessing the Pilot Implementation of the Integrated Multimorbidity Care Model in Five European Settings: Results from the Joint Action CHRODIS-PLUS”, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17155268.

The evaluation found that between 2017 and 2019 there was a statistically significant (p < 0.001) improvement in patient experiences measured using the overall PACIC survey score – i.e. from 2.91 to 3.46. Patient experiences improved in each dimension, in particular for the “Arrange” dimension (+33% increase in dimension score) (Rodriguez-Blazquez et al., 2020[6]). Caution should be taken when interpreting results given the study involved just 42 patients (for further details of the study design, see the “Evidence‑based” criterion).

The above results were strengthened by a follow-up PACIC survey undertaken during the post-implementation phase (i.e. patient experiences improved). Results from this survey included additional questions for patients.

Conversely, the overall ACIC score fell from 7.90 to 6.77; however, this fall was not statistically significant. A possible explanation for this unexpected result is that there may have been “uncertainty” among healthcare managers due to political changes occurring during the time of the intervention (Rodriguez-Blazquez et al., 2020[6]).

The impact of the PAP programme on objective health outcomes is not available. Therefore, findings from the wider literature regarding personalised care plans are summarised to highlight PAP’s potential. A Cochrane Review covering 19 studies and over 10 000 patients found personalised care plans have a positive, albeit small, impact on both physical and psychological health (Coulter et al., 2015[7]):

HbA1c was 0.24% lower for those who received personalised care plans

Systolic blood pressure was 2.64mm/Hg lower for those who received personalised care plans

No impact on cholesterol or body mass index (BMI)

Levels of depression were lower among who received personalised care plans (standardised mean difference of ‑0.36).

It is important to note that the findings above largely relate to personalised care plans targeting patients with asthma, diabetes or depression, which is not the current focus of the PAP programme.

Efficiency

The impact of the PAP programme on healthcare utilisation was measured using a pre/post study design in years 2017, 2018 and 2019. Results from the analysis covered a range of utilisation measures covering primary, outpatient, inpatient and emergency care. A full overview of results are in Table 14.1, which show that the rate of increase in healthcare utilisation slowed and in some cases declined between years 2017‑18 and 2018‑19.

Based on estimates from the Andalusian Health Service, by slowing the increase in healthcare utilisation, the PAP programme reduced costs by 23.5%.

Table 14.1. Change in healthcare utilisation between years 2017‑18 and 2018‑19

|

Indicator |

% change between 2017 and 2018 |

% change between 2018 and 2019 |

Did the rate of growth increase at a faster rate, a slower rate, or even decline? |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Unplanned, potentially avoidable inpatient episodes |

+37.1% |

+16.1% |

Slower increase |

|

Family physician visits at PHC* |

+11.7% |

‑9.0% |

Negative growth |

|

Family nurse visits at PHC* |

+25.3% |

‑3.4 |

Negative growth |

|

Family physician home visits |

+66.3% |

+66% |

Slower increase |

|

Family nurse home visits |

+44.4% |

+12.9% |

Slower increase |

|

Emergency episodes at PHC |

+12.7% |

‑3.3% |

Negative growth |

|

Emergency episodes at hospital |

+14.5% |

+2.3% |

Slower increase |

|

Outpatient visits |

+9.7% |

‑3.9% |

Negative growth |

|

Inpatient episodes |

+23.3% |

+1.4% |

Slower increase |

Note: *Primary healthcare.

Source: Information provided by administrators of the PAP programme.

The economic impact of personalised care plans is limited in the wider literature. Further, the most extensive systematic review to date on the subject noted that the “evidence on the relative cost effectiveness of [personalised care plans] is limited and uncertain” (Coulter et al., 2015[7]).

Equity

The design of the PAP programme takes into account the needs of each individual patient, including those from disadvantaged backgrounds. The programme does this by:

Developing care plans designed to accommodate to specific patient needs

Standardising care for all individuals in the region

Including a social worker within the patient’s multidisciplinary care team, who are there to ensure the patient’s wider needs are met.

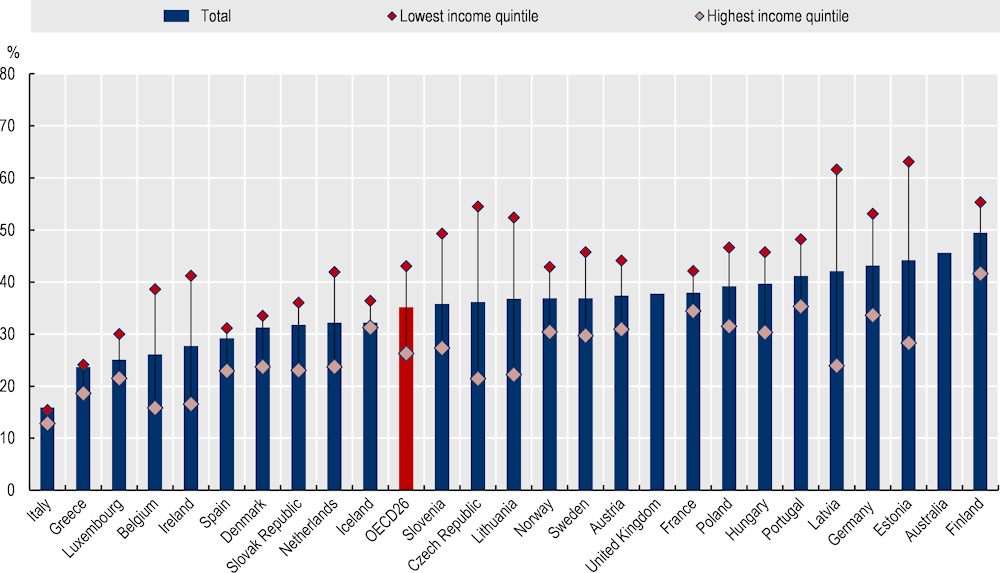

There is no evidence measuring the impact of the PAP programme on equity. Nevertheless, the programme has the potential to reduce health inequalities by targeting patients with one or more chronic diseases, given rates of morbidity are higher among lower socio-economic groups. This disparity is largely due to lifestyle behaviours, with rates of smoking and obesity, for example, higher among these groups. Further, those who are economically disadvantaged are also more vulnerable to the adverse effects of unhealthy lifestyles. For example, a recent study by Mair and Jani (2020[8]) found that, after adjusting for lifestyle factors, those with a low socio-economic status are at an increased risk of developing 18 of the 56 major diseases and health conditions compared to advantaged groups. This finding is supporting by data from OECD countries, which show lower income groups are more likely to report living with a long-standing illness or health problem (see Figure 14.2).

Although the PAP programme promotes health equity, policy makers should be aware of its potential to widen inequalities. For example:

By using digital means to recruit patients, there is a risk of overlooking population groups who are less likely to access healthcare and who are therefore not identified within the region’s Health Data Base.

People with lower levels of healthy literacy or communication difficulties may be less likely to engage in the programme (Coulter et al., 2015[7]).

Figure 14.2. People reporting a long-standing illness or health problem, by income quintile, 2019 (or nearest year)

Note: Data are self-reported.

Source: EU-SILC 2021 and national health surveys.

Evidence‑based

The evidence‑based criterion assesses the quality of evidence used to measure the impact of the PAP programme and therefore the validity of the results. This section focuses only on the study design used to assess the effectiveness and efficiency of PAP, given no studies to date have assessed its impact on health inequalities.

Effectiveness evidence base

Rodriguez-Blazquez et al. (2020[6]) evaluated the impact of the PAP programme from both a patient and health system perspective. The quality of the study design is summarised in Table 14.2 using the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies from the Effective Public Health Practice Project (Effective Public Health Pratice Project, 1998[9]).

In short, the study involved a pre‑post study design with a treatment group only, with outcomes measured using reliable and valid tools. The study design is rated as “strong” or “moderate” in many areas, however, the study’s internal validity is downgraded given participants were not randomly selected and that there was no control group.

Table 14.2. Evidence‑based assessment – Personalised Actions Plans

|

Assessment category |

Question |

Score using Rodriguez-Blazquez et al. (2020[6]) |

|---|---|---|

|

Selection bias |

Are the individuals selected to participate in the study likely to be representative of the target population? |

Somewhat likely |

|

What percentage of selected individuals agreed to participate? |

Unknown |

|

|

Selection bias score: Moderate |

||

|

Study design |

Indicate the study design |

Cohort (one group pre + post) |

|

Was the study described as randomised? |

N/A |

|

|

Was the method of randomisation described? |

N/A |

|

|

Was the method of randomisation appropriate? |

N/A |

|

|

Study design score: Moderate |

||

|

Confounders |

Were there important differences between groups prior to the intervention? |

N/A (treatment group only) |

|

What percentage of potential confounders were controlled for? |

80‑100% |

|

|

Confounders score: Strong |

||

|

Blinding |

Was the outcome assessor aware of the intervention or exposure status of participants? |

Yes |

|

Were the study participants aware of the research question? |

Unknown |

|

|

Blinding score: Weak |

||

|

Data collection methods |

Were data collection tools shown to be valid? |

Yes |

|

Were data collection tools shown to be reliable? |

Yes |

|

|

Data collection methods score: Strong |

||

|

Withdrawals and dropouts |

Were withdrawals and dropouts reported in terms of numbers and/or reasons per group? |

N/A (no dropouts) |

|

Indicate the percentage of participants who completed the study? |

N/A |

|

|

Withdrawals and dropouts score: N/A |

||

Note: N/A = not applicable.

Source: Effective Public Health Practice Project (1998[9]), “Quality assessment tool for quantitative studies”, https://www.nccmt.ca/knowledge-repositories/search/14.

Efficiency evidence base

As outlined under “Efficiency”, the PAP programme is associated with a decline in the rate at which healthcare service utilisation grows. Limited information is available regarding the study design that found these results, therefore, this section provides a qualitative assessment of the study’s overall design, as opposed to using the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies.

The Andalusian Local Implementation Working Group as part of the JA CHRODIS+ used a pre/post study design to evaluate any changes in healthcare utilisation. The study covered 2 788 patients with data recorded in year 2017, 2018 and 2019. Changes in healthcare utilisation among a similar group of patients over the same period were not explored, further it is unclear if selected patients represent the target population. For this reason, results from the study imply an association between PAP and reduced healthcare demand as opposed to the programme being the cause of the fall.

Extent of coverage

Data from the Andalusian Health Service show that 200 700 people in the region are currently eligible for the PAP programme. Andalusia’s sophisticated health data system means most eligible patients are identified. It is unclear what proportion of those who are eligible “sign up” to receive a PAP, however, feedback from health professionals indicate there is a high level of interest and enthusiasm among patients.

Policy options to enhance performance

This section outlines policies to enhance the overall performance of Andalusia’s PAP programme. Policies are broken down by the five best practice criteria.

Enhancing effectiveness

Maintain the PAP programme design as it includes all the key features of a well-designed personalised care plan. A 2015 systematic review outlined the necessary components within a personalised care programme – preparation, goal setting, action planning, documenting, co‑ordinating, supporting, and reviewing (Coulter et al., 2015[7]). Each of these steps are available within the PAP programme (see “Intervention description”). The same systematic review also identified additional features associated with greater benefits, which also align with the PAP programme, namely: integrated into routine care, comprehensive and intensive. For this reason, changes to the design of the PAP programme are not recommended, rather, policy makers should focus on policy enhancements listed below.

Restart activities to align with pre‑pandemic levels. The COVID‑19 pandemic halted most PAP related activities given the pressure placed on the healthcare system. For this reason, as highlighted by PAP administrators, the first step in enhancing the effectiveness of the programme is to increase activities back to pre‑pandemic levels.

Introduce new PAP training for health professionals to streamline patient records. At present, health professionals vary in how they draft PAPs for their patients. Therefore, additional training has been recommended by PAP administrators in order to ensure all patient information is recorded within the region’s electronic health record system (Diraya), and that reporting of patient information is streamlined.

Further support to healthcare professionals may be necessary. As outlined under “Effectiveness”, the impact of the PAP programme from a health system perspective declined over the evaluation period. Although these results were not statistically significant, it is important to understand why health professionals didn’t express an improvement. The report by Rodriguez-Blazquez et al. (2020[6]) provides a possible explanation for this result (i.e. political uncertainty1), but this was not confirmed. Based on reviews of other integrated care models in OECD countries, including Spain, the following strategies may improve health professional experiences:

Ensure sufficient resources to avoid burnout. Health professionals’ workload may increase as a result of the PAP programme, therefore, it is important to ensure they receive necessary support, and have the time and resources to take on new activities. This has been recognised by policy makers in Andalusia who are revising the health professional to patient ratio as part of the Regional Ministry of Health’s next action plan.2 Working conditions are also being reviewed as part of Spain’s upcoming national plan for primary care.

Ensure health professionals have the appropriate skills to develop a PAP (i.e. know how to work as a team and use necessary digital tools) so that they feel confident delivering this type of care.

Ensure health professionals are involved in the design of the programme, or in this case, any amendments to the PAP programme in order to secure “buy in”.

Enhancing efficiency

Efficiency is a measure of effectiveness in relation to inputs used. Therefore, interventions that increase effectiveness without significant increases in costs, or reduce costs while keeping effectiveness at least constant, have a positive effect on efficiency.

Enhancing equity

Collect data to first understand the impact of the PAP programme across different population groups. As outlined under “Equity”, the PAP programme is designed to cater to the needs of each individual, including those from disadvantaged groups. However, the impact of the programme across population groups is unknown. A first step to enhancing equity is to first understand whether any inequalities exist in terms of access, health outcomes and patient experiences. Such information is vital for implementing policies that address any known inequities. For further information, see “Enhancing the evidence‑base” (Table 14.3).

Enhancing the evidence‑base

Enhance the range of indicators used to evaluate the PAP programme. Previous evaluations of the PAP programme have focused on measuring the change in patient and health professional experiences. It is important to complement subjective information with data on changes in objective health outcomes. A list of potential indicators to include in future evaluations are available in Table 14.3. These indicators reflect three of the best practice criteria – effectiveness, efficiency and equity.

Evaluate the PAP programme using a robust study design. To ensure the validity of results, it is important to collect indicators within a well-designed evaluation study. Information on how to undertake a well-designed evaluation are available in OECD’s Guidebook on Best Practices in Public Health (OECD, 2022[10]). The best study design for the PAP programme will depend on several factors such as available resources and patient data. However, in general, study designs which randomly allocate patients into treatment and control groups and where data is collected over several periods are generally considered the strongest.

Table 14.3. Evaluation indicators

This table outlines effectiveness, efficiency and equity indicators to measure when evaluating the PAP programme

|

Best practice criteria |

Indicators |

|---|---|

|

Effectiveness Effectiveness indicators will ultimately depend on targeted chronic health conditions. This list below covers several conditions and covers objectives health outcomes (final and intermediate) and subjective health outcomes. |

Final objective health outcomes (reflect the ultimate objective of the programme): Blood pressure BMI Cholesterol levels HbA1c levels (diabetic patients only) Asthma Therapy Assessment Questionnaire (ATAQ) Number of falls, pressure ulcers and drug-related problems (these align with stated PAP objectives) Disease‑related deaths All-cause deaths |

|

Intermediate objective health outcomes (directly related to final health outcomes) Diet (e.g. consumption of fruit and vegetables per day) Level of exercise (e.g. minutes per week engaged in moderate to intense physical exercise) Cigarettes smoked per day Medication adherence |

|

|

Subjective health outcomes Subjective heath status such as the SF‑36 or SF‑12 For depression and anxiety: Patient health questionnaire (PhQ‑9) for depression and anxiety; Hopkins Symptom Checklist 20; Beck Depression Inventory; Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale For self-efficacy: Strategies Used by People to Promote Health (SUPHH); and six‑item Self-efficacy for Managing Chronic Disease Scale or the 4‑utm Spanish-language version (SEMCD-S) |

|

|

Efficiency |

Disease‑related hospital admissions All-cause hospital admissions Disease‑related emergency admissions All-cause emergency admissions Use of other healthcare services such as home visits, outpatient visits, and specialist visits |

|

Equity |

To the extent possible, stratify effectiveness and efficiency indicators to assess PAP’s impact on health inequalities. Example ways stratify data are outlined below: Age and gender Income Education level Ethnicity Location (e.g. rural, regional or urban). |

For greater insight, outcome evaluations can be paired with a process evaluation which assesses whether the PAP programme was implemented as planned. For example, if an outcome evaluation reveals no major change in key outcome indicators, a process evaluation will inform researchers whether this is due to poor implementation or not.

Enhancing extent of coverage

The proportion of eligible patients who receive a PAP is unknown, as is the level of take up across population groups (e.g. by gender, ethnicity, income status). Therefore, it is unclear whether recommendations on how to extend coverage to eligible patients are necessary or not.

To expand the programme’s reach in Andalusia, eligibility criteria could be extended beyond patients with heart failure or COPD (i.e. prioritised complex chronic patients). Based on a high-level review of the literature, PAPs would be particularly beneficial to patients with:3

Asthma: a systematic review and meta‑analysis found asthma patients who receive self-management interventions reported statistically lower use of healthcare services and a better quality of life (Hodkinson et al., 2020[11]).

Diabetes: a 2015 systematic review found personalised care plans for diabetes patients leads to improvements, albeit small, in objective health outcomes (e.g. HbA1c and systolic blood pressure) (Coulter et al., 2015[7]).

Multiple chronic conditions: personalised care plans are useful for those with multiple conditions as interdependencies between conditions and their collective impact are taken into account when treating the patient (NHS England, 2015[12]).

Transferability

This section explores the transferability of the PAP programme and is broken into three components: 1) an examination of previous transfers; 2) a transferability assessment using publicly available data; and 3) additional considerations for policy makers interested in transferring this programme.

Previous transfers

As outlined by a recent OECD report, personalised care plans have been widely used across developed countries for many years (OECD, 2020[4]). For example, in Australia, England (the United Kingdom) and even different regions of Spain (see Box 14.4). Despite “widespread support” for personalised care planning, data reveals that patients continue to feel inadequately supported by health professionals to self-manage their own health conditions (Coulter et al., 2015[7]). This finding indicates that in theory, personalised care plans are transferable to different regions, yet in practice are often poorly implemented.

“Even an appropriate and well-designed intervention can fail if it is poorly implemented.” (OECD, 2022[10])

A systematic review of personalised are plans by Coulter et al. (2015[7]) provides insight into why personalised care plans may fail in practice. Specifically, the authors highlight a potential reluctance among health professionals to embark on such a “significant and cultural change” to the way they practice healthcare. Further, healthcare professionals may feel care plans are too cumbersome for either the patient or themselves. This finding highlights the importance of securing stakeholder “buy in” before transferring an intervention to a new region.

Box 14.4. Personalised care plans examples among selected OECD countries

This box describes, at a high level, personalised care plan programs implemented in a selection of OECD countries, including the Basque country in Spain.

Australia

In 1999, Australia introduced the Enhanced Primary Care (EPC) package, which outlined a shift towards care planning and therefore a different approach to chronic disease management. Under EPC, the national health insurance scheme reimburses healthcare professionals for the time spent developing multidisciplinary care plans to patients with chronic and complex needs. In 2005, EPC was renamed Chronic Disease Management, however, the policy remained the same.

There is no list of eligible conditions; rather, suitability for the programme is based on a GP’s clinical judgement.

Basque country, Spain

In 2010, the Basque Country’s Department of Health launched the “Strategy to tackle the challenges of chronicity”. In line with the strategy, the Basque Health Service developed an integrated care model for multimorbid patients. The model consists of several characteristics including the development of individualised therapeutic plans between patients and a multidisciplinary care team. Similar to the PAP programme in Andalusia, Spain, the integrated care model in the Basque country identifies eligible patients using electronic patient data.

England, the United Kingdom

Since 2010, in England, patients living with a long-term condition are involved in a care planning process. Eligible patients receive a personalised care and support plan, which must meet the following criteria:

People are central to developing and finalised the plan

People proactively verbalise what matters to them to ensure their needs are met

People agree to the health and well-being outcomes they want to achieve in partnership with health professionals

The plan is recorded and sharable, and outlines what matters to people and how their outcomes will be achieved

People have the option to review their plan.

Source: Australian Government Department of Health (2022[13]), “Chronic Disease Management (formerly Enhanced Primary Care or EPC) – GP services”, https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/mbsprimarycare-chronicdiseasemanagement; NHS England (2022[14]), “Personalised care and support planning”. https://www.england.nhs.uk/ourwork/patient-participation/patient-centred/planning/; WP5 Jadecare (2020[15]), “Presentation of the original good practice – Basque health strategy in ageing and chronicity: integrated care”.

To limit the possibility of implementation failure, administrators from the PAP programme have outlined key factors to consider before transfer and implementation takes place (see Box 14.5).

Box 14.5. Key factors to consider before transferring the PAP programme

The following factors of the PAP programme are considered essential and should therefore be considered by countries interested in transferring this intervention:

Have a team of experts develop training materials on how to treat patients with complex health needs as well as how to use PAPs

Ensure there is sufficient training for health professionals and patients in regards to how to use a PAP

Ensure co‑ordination between health professionals working in primary and secondary care

Systematise PAP processes to avoid variability

Enable PAPs to be registered within a patient electronic health record that is stored within a strong IT system

Ensure healthcare professionals have the time and resources to develop PAPs.

Source: Information provided by administrators of the PAP programme.

Transferability assessment

The following section outlines the methodological framework to assess transferability and results from the assessment.

Methodological framework

A few indicators to assess the transferability of the PAP programme were identified (see Table 14.4). Indicators were drawn from international databases and surveys to maximise coverage across OECD and non-OECD European countries. Please note, the assessment is intentionally high level given the availability of public data covering OECD and non-OECD European countries.

Table 14.4. Indicators to assess transferability – Personalised Actions Plans

|

Indicator |

Reasoning |

Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

|

Sector context (primary and secondary care) |

||

|

Proportion of GPs who work in single‑handed practices |

The intervention is more transferable in countries where GPs feel comfortable working with other health professionals. This indicator is a proxy to measure the willingness of GPs to work in co‑ordinated teams. |

Low = more transferable High = less transferable |

|

Proportion of physicians in primary care facilities using electronic health records (EHRs) |

EHRs improve the ability of health professionals to provide integrated patient-centred care. Therefore, the intervention is more transferable in countries that utilise EHRs in primary care facilities. |

🡹 value = more transferable |

|

Proportion of hospitals using EHRs |

As above |

🡹 value = more transferable |

|

The extent of task shifting between physicians and nurses in primary care |

This intervention promotes integrated care provided by multidisciplinary teams. Therefore, the intervention is more transferable in countries where physicians feel comfortable shifting tasks to nurses. |

The more “extensive” the more transferable |

|

The use of financial incentives to promote co‑ordination in primary care |

The intervention is more transferable to countries with financial incentives that promote co‑ordination of care across health professionals. |

Bundled payments or co‑ordinated payment = more transferable |

|

Economic context |

||

|

Primary healthcare expenditure as a percentage of current health expenditure |

The intervention places a stronger emphasis on primary care, therefore, it is likely to be more successful in countries that allocate a higher proportion of health spending to primary care |

🡹 value = more transferable |

Source: WHO (2018[16]), “Primary Healthcare (PHC) Expenditure as percentage Current Health Expenditure (CHE)”, https://apps.who.int/nha/database; Oderkirk (2017[17]), “Readiness of electronic health record systems to contribute to national health information and research”, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9e296bf3-en; Schäfer et al. (2019[18]), “Are people’s health care needs better met when primary care is strong? A synthesis of the results of the QUALICOPC study in 34 countries”, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1463423619000434; Maier and Aiken (2016[19]), “Task shifting from physicians to nurses in primary care in 39 countries: a cross-country comparative study”, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckw098; OECD (2020[4]), Realising the Potential of Primary Health Care, https://doi.org/10.1787/a92adee4-en; OECD (2016[20]), “Health Systems Characteristics Survey”, https://qdd.oecd.org/subject.aspx?Subject=hsc; European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (2021[21]), “The Health Systems and Policy Monitor”, https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int/countries/overview.

Results

Results from the transferability assessment are summarised below, with country-level details available in Table 14.5. Due to data constraints, the “owner” setting is Spain, as opposed to the region of Andalusia, which is limitation of the analysis.

The proportion of GPs who work in single practices is mixed among potential transfer countries. These results indicate GPs in some countries would more readily accept working in a multidisciplinary team and others not. Similarly, task shifting in primary care is either “limited” or non-existent in most OECD countries (72%), which also inhibits multidisciplinary care work.

Use of EHRs are relatively high in Spain, including the region of Andalusia, compared to the average of all countries. EHRs are an important element of the PAP programme as they help identify all eligible patients and allow health professionals to easily share patient data.

Most countries do not employ financing methods that incentivise integrated care, including Spain: among examined countries, 19% employ have bundled payments while a further 16% use financial incentives for co‑ordinated care.

Over 40% of all healthcare expenditure is spent on primary care among analysed countries, which is higher than in Spain (39%). Therefore, long-term affordability issues may not be of significant concern to countries interested in transferring this intervention.

Table 14.5. Transferability assessment by country (OECD and non-OECD European countries) – Personalised Actions Plans

A darker shade indicates the PAP programme is more suitable for transferral in that particular country

|

Country |

% GPs in single practices |

% PC* using EHRs |

% hospitals using EHRs |

Task shifting in PC* |

Financial incentives |

Primary expenditure percentage CHE** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Spain |

Low |

99 |

80 |

Limited |

No incentive |

39 |

|

Australia |

Low |

96 |

20 |

Extensive |

Bundled |

37 |

|

Austria |

High |

80 |

99 |

None |

Co‑ordinated payment |

37 |

|

Belgium |

High |

n/a |

n/a |

Limited |

Bundled |

40 |

|

Bulgaria |

High |

n/a |

n/a |

None |

Bundled |

47 |

|

Canada |

Low |

77 |

69 |

Extensive |

Bundled |

48 |

|

Chile |

n/a |

65 |

69 |

n/a |

No incentive |

n/a |

|

Colombia |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

No incentive |

n/a |

|

Costa Rica |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

No incentive |

33 |

|

Croatia |

n/a |

3 |

n/a |

Limited |

No incentive |

38 |

|

Cyprus |

Low |

n/a |

n/a |

Limited |

No incentive |

41 |

|

Czech Republic |

High |

n/a |

100 |

None |

No incentive |

33 |

|

Denmark |

Medium |

100 |

100 |

Limited |

Co‑ordinated payment |

38 |

|

Estonia |

High |

99 |

100 |

Limited |

No incentive |

44 |

|

Finland |

Medium |

100 |

100 |

Extensive |

No incentive |

46 |

|

France |

n/a |

80 |

60 |

None |

Bundled |

43 |

|

Germany |

High |

n/a |

n/a |

None |

Co‑ordinated payment |

48 |

|

Greece |

High |

100 |

50 |

None |

No incentive |

45 |

|

Hungary |

High |

n/a |

n/a |

Limited |

No incentive |

40 |

|

Iceland |

Low |

100 |

100 |

Limited |

Co‑ordinated payment |

35 |

|

Ireland |

Low |

95 |

35 |

Extensive |

No incentive |

47 |

|

Israel |

n/a |

100 |

100 |

n/a |

Co‑ordinated payment |

n/a |

|

Italy |

Medium |

n/a |

n/a |

Limited |

Bundled |

n/a |

|

Japan |

n/a |

36 |

34 |

n/a |

No incentive |

52 |

|

Korea |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

No incentive |

57 |

|

Latvia |

High |

70 |

90 |

Limited |

Bundled |

39 |

|

Lithuania |

Medium |

n/a |

n/a |

Limited |

No incentive |

48 |

|

Luxembourg |

Medium |

n/a |

n/a |

None |

No incentive |

38 |

|

Malta |

Medium |

n/a |

n/a |

Limited |

No incentive |

62 |

|

Mexico |

n/a |

30 |

49 |

n/a |

Co‑ordinated payment |

44 |

|

Netherlands |

Medium |

n/a |

n/a |

Extensive |

Bundled |

32 |

|

New Zealand |

Low |

95 |

100 |

Extensive |

No incentive |

n/a |

|

Norway |

Low |

100 |

100 |

None |

No incentive |

39 |

|

Poland |

Medium |

30 |

10 |

None |

No incentive |

47 |

|

Portugal |

Low |

n/a |

n/a |

Limited |

No incentive |

58 |

|

Romania |

Medium |

n/a |

n/a |

None |

No incentive |

35 |

|

Slovak Republic |

High |

89 |

100 |

None |

No incentive |

n/a |

|

Slovenia |

High |

n/a |

n/a |

Limited |

No incentive |

43 |

|

Sweden |

Low |

100 |

100 |

Limited |

Co‑ordinated payment |

n/a |

|

Switzerland |

Medium |

40 |

100 |

None |

No incentive |

40 |

|

Türkiye |

Low |

n/a |

n/a |

None |

No incentive |

n/a |

|

United Kingdom |

Low |

99 |

100 |

Extensive |

No incentive |

53 |

|

United States |

n/a |

83 |

76 |

Extensive |

No incentive |

n/a |

Note: *PC = primary care. **CHE = current health expenditure. n/a = no data available.

Source: See Table 14.4.

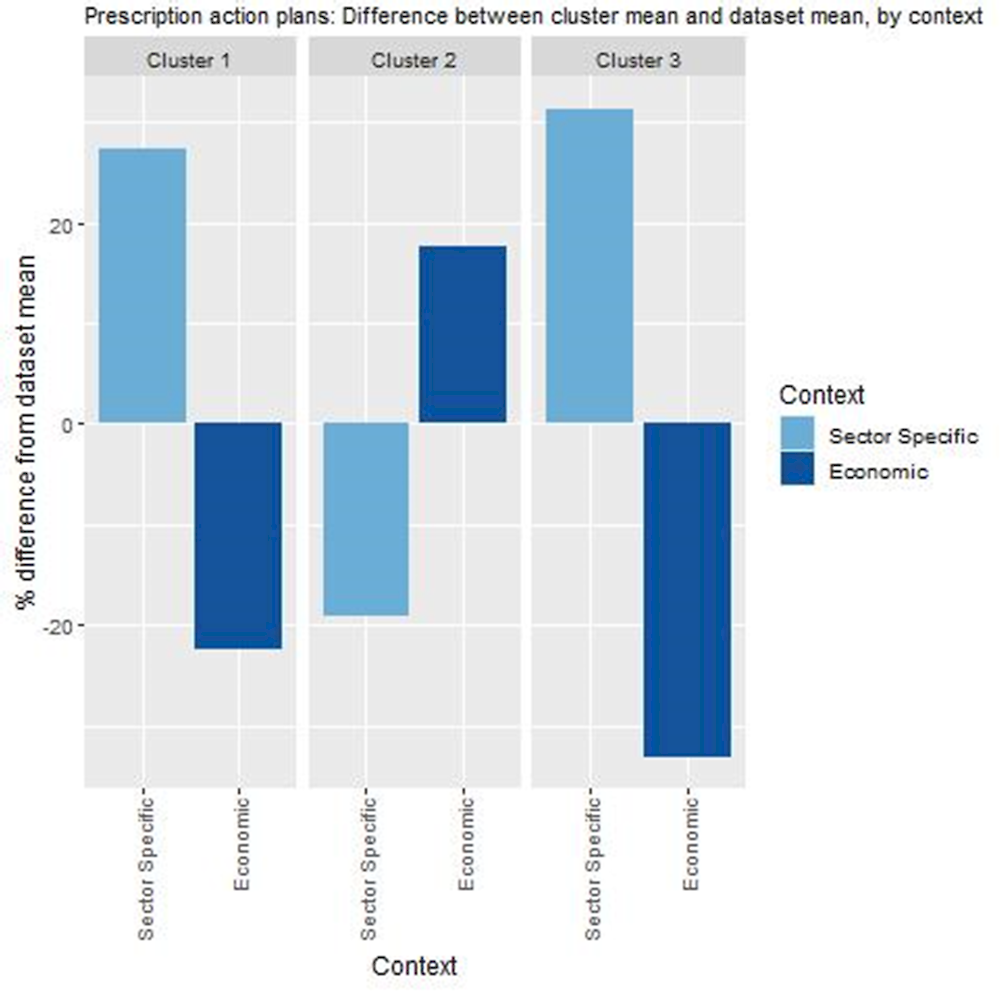

To help consolidate findings from the transferability assessment above, countries have been clustered into one of three groups, based on indicators reported in Table 14.4. Countries in clusters with more positive values have the greatest transfer potential. For further details on the methodological approach used, please refer to Annex A.

Key findings from each of the clusters are below with further details in Figure 14.3 and Table 14.6:

Countries in cluster one typically have primary and secondary care sectors with the capability to implement the PAP programme (e.g. high use of EHRs at both care levels, and greater levels of task shifting). However, these countries also spend relatively less on primary care, which is where the PAP programme is primarily focused.

Conversely, countries in cluster two spend relatively more on primary care indicating long-term financial sustainability for a PAP programme. However, certain countries in this cluster would benefit from assessing whether their primary and secondary care sectors are ready to implement the PAP programme. It is important to note that Spain falls under cluster two indicating that although it is ideal for different levels of the healthcare system to be integrated, it is not a pre‑requisite for a successful transfer.

Similar to cluster one, countries in cluster three typically have a healthcare system prepared to implement the PAP programme. However, more so than cluster one, countries in this cluster may suffer from long-term affordability issues if spending on primary care remains low.

Figure 14.3. Transferability assessment using clustering – Personalised Actions Plans

Note: Bar charts show percentage difference between cluster mean and dataset mean, for each indicator.

Source: See Table 14.4.

Table 14.6. Countries by cluster – Personalised Actions Plans

|

Cluster 1 |

Cluster 2 |

Cluster 3 |

|---|---|---|

|

Australia Belgium Bulgaria Croatia Estonia France Italy Latvia Mexico Netherlands |

Canada Chile Cyprus Czech Republic Finland Greece Hungary Ireland Japan Lithuania Luxembourg Malta New Zealand Norway Poland Portugal Romania Slovak Republic Slovenia Spain Switzerland Türkiye United Kingdom United States |

Austria Denmark Germany Iceland Israel Sweden |

Note: The following countries were omitted due to high levels of missing data: Costa Rica, Colombia and Korea.

New indicators to assess transferability

Data from publicly available datasets alone is not ideal to assess the transferability of public health interventions. Box 14.6 outlines several new indicators policy makers could consider before transferring the PAP programme.

Box 14.6. New indicators, or factors, to consider when assessing transferability – Personalised Actions Plans

In addition to the indicators within the transferability assessment, policy makers are encouraged to collect information for the following indicators:

Population context

What is the level of health literacy among patients and caregivers? (i.e. are patients/caregivers likely to engage in shared decision-making?)

What is the population’s attitude towards receiving care from health professionals who are not doctors?

Sector specific context (primary and secondary care)

What is the level of trust among health professionals to work together as a co‑ordinated team?

What is the level of support among health professionals to introduce personalised care plans?

Does the clinical information system support: a) sharing of patient data across health professionals? b) Sharing of patient data across healthcare facilities?

Do health provider reimbursement schemes support co‑ordinated care? (E.g. bundled payments, add-on payments that incentivise co‑ordinated care)

Do regulations support integrated care models (i.e. professional competencies and practice scope)?

Political context

Has the intervention received political support from key decision-makers (e.g. a national strategy to address ageing and chronicity)?

Has the intervention received commitment from key decision-makers?

Economic context

What is the cost of implementing and operating the intervention in the target setting and to whom?

Conclusion and next steps

In response to rising rates of people living with chronic conditions, Andalusia, Spain, introduced the PAP programme. The PAP programme was formally introduced in 2016, whereby eligible patients work with a multidisciplinary healthcare team to develop a long-term individual treatment/action plan. Since 2021, the PAP programme has focused on individuals living with heart failure or COPD, which equates to around 110 000-120 000 eligible patients.

An evaluation of the PAP in 2020 revealed an improvement in patient experiences, however the impact on health professionals is unclear. Using the validated PACIC survey, an evaluation by (Rodriguez-Blazquez et al., 2020[6]) revealed the PAP programme led to a statistically significant improvement in patient experiences. The same evaluation recorded a fall in the score used to measure the PAP programme from a health system perspective, however, this result was not statistically significant.

The design of the PAP programme promotes health equality, but this is not yet supported by data. The PAP programme develops care plans specific to individual needs, standardises care across the region and where necessary includes the expertise of a social worker. Further, the programme likely disproportionally benefits disadvantaged groups – e.g. low SES – given rates of morbidity are typically higher among such populations. Robust evidence supporting these claims, however, is not available.

Several options are available to policy makers to enhance the performance of the PAP programme. These include, but are not limited to, improving satisfaction among health professionals, collecting additional health outcome indicators and expanding eligibility to other chronic conditions.

Personalised care plans similar to the PAP programme exist across many OECD countries, but are generally more transferable to countries that promote integrated, digital care. Countries such as Australia, England and also other regions of Spain have been using personalised care programs for many years. For example, in Australia they were first introduced in 1999. Based on publicly available indicators, such programs are more easily transferred to countries that encourage health professionals to work as a team, and who have systems in place that support the use of digital means to share patient data (i.e. electronic health records).

Box 14.7 outlines next steps for policy makers and funding agencies regarding the PAP programme.

Box 14.7. Next steps for policy makers and funding agencies – Personalised Actions Plans

Next steps for policy makers and funding agencies to enhance the PAP programme are listed below:

Undertake research to understand why health professionals may be less satisfied with the PAP programme compared to usual care

Prioritise evaluations of the PAP programme that collect data on objective health outcomes as well as data across different population groups

Support efforts to expand the programme to chronic conditions beyond COPD and heart failure if feasible.

References

[13] Australian Government Department of Health (2022), Chronic Disease Management (formerly Enhanced Primary Care or EPC) — GP services, https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/mbsprimarycare-chronicdiseasemanagement.

[1] Chapel, J. et al. (2017), “Prevalence and Medical Costs of Chronic Diseases Among Adult Medicaid Beneficiaries”, American Journal of Preventive Medicine, Vol. 53/6, pp. S143-S154, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2017.07.019.

[3] Cosano, I. et al. (2019), “Personalized Action Plan in Andalusia: supporting the Chrodis-Plus integrated care model for multimorbidity”, International Journal of Integrated Care, Vol. 19/4, p. 474, https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.s3474.

[7] Coulter, A. et al. (2015), “Personalised care planning for adults with chronic or long-term health conditions”, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd010523.pub2.

[9] Effective Public Health Pratice Project (1998), Quality assessment tool for quantitative studies, https://www.nccmt.ca/knowledge-repositories/search/14.

[21] European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (2021), The Health Systems and Policy Monitor, https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int/countries/overview (accessed on 9 June 2021).

[2] Eurostat (2022), People having a long-standing illness or health problem, by sex, age and educational attainment level.

[11] Hodkinson, A. et al. (2020), “Self-management interventions to reduce healthcare use and improve quality of life among patients with asthma: systematic review and network meta-analysis”, BMJ, p. m2521, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m2521.

[19] Maier, C. and L. Aiken (2016), “Task shifting from physicians to nurses in primary care in 39 countries: a cross-country comparative study”, The European Journal of Public Health, Vol. 26/6, pp. 927-934, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckw098.

[8] Mair, F. and B. Jani (2020), “Emerging trends and future research on the role of socioeconomic status in chronic illness and multimorbidity”, The Lancet Public Health, Vol. 5/3, pp. e128-e129, https://doi.org/10.1016/s2468-2667(20)30001-3.

[14] NHS England (2022), Personalised care and support planning, https://www.england.nhs.uk/ourwork/patient-participation/patient-centred/planning/.

[12] NHS England (2015), Personalised care and support planning handbook: The hourney to person-centred care, https://www.nhs.uk/nhsengland/keogh-review/documents/pers-care-guid-core-guid.pdf.

[17] Oderkirk, J. (2017), “Readiness of electronic health record systems to contribute to national health information and research”, OECD Health Working Papers, No. 99, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9e296bf3-en.

[10] OECD (2022), Guidebook on Best Practices in Public Health, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/4f4913dd-en.

[4] OECD (2020), Realising the Potential of Primary Health Care, OECD Health Policy Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/a92adee4-en.

[20] OECD (2016), Health Systems Characteristics Survey 2016, https://qdd.oecd.org/subject.aspx?Subject=hsc.

[6] Rodriguez-Blazquez, C. et al. (2020), “Assessing the Pilot Implementation of the Integrated Multimorbidity Care Model in Five European Settings: Results from the Joint Action CHRODIS-PLUS”, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, Vol. 17/15, p. 5268, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17155268.

[18] Schäfer, W. et al. (2019), “Are people’s health care needs better met when primary care is strong? A synthesis of the results of the QUALICOPC study in 34 countries”, Primary Health Care Research & Development, Vol. 20, https://doi.org/10.1017/s1463423619000434.

[5] Servicio Andaluz de Salud (2016), Plan de acción personalizado en pacientes pluripatológicos o con necesidades complejas de salud: Recomendaciones para su elaboración, https://www.opimec.org/media/files/Plan_Accion_Personalizado_Edicion_2016.pdf.

[16] WHO (2018), Primary Health Care (PHC) Expenditure as % Current Health Expenditure (CHE).

[15] WP5 Jadecare (2020), Presentation of the original good practice - Basque health strategy in ageing and chronicity: integrated care.

Notes

← 1. The study by Rodriguez-Blazquez et al. (2020[6]) collected data before and after a change in the political team in charge of the Regional Government.

← 2. There is both a national plan for primary care (2022‑23), which is to be adapted by each regional health system, including Andalusia.

← 3. Eligible patients – i.e. those with heart failure or COPD – may also have other chronic conditions such as asthma or diabetes.